Abstract

Sirolimus (SIR)/tacrolimus (TAC) is an alternative to methotrexate (MTX)/TAC. However, rational selection among these GvHD prophylaxis approaches to optimize survival of individual patients is not possible based on current evidence. We compared SIR/TAC (n = 293) to MTX/TAC (n = 414). The primary objective was to identify unique predictors of overall survival (OS). Secondary objective was to compare acute and chronic GvHD, relapse, non-relapse mortality, thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), hepatic veno-occlusive disease (VOD/SOS), and acute kidney injury. Day 100 grades II–IV acute GvHD was significantly reduced in SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC group (63 vs 73%, P = 0.02). An interaction between GvHD prophylaxis groups and comorbidity index (hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-CI) significantly impacted OS. Patients with HCT-CI ⩾ 4 had significantly worse OS with MTX/TAC (HR 1.86, 95% CI 1.14–3.04, P = 0.01) while no such effect was seen for SIR/TAC (HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.48–1.26, P = 0.31). Other end points did not significantly differ between groups except TMA and VOD/SOS were increased in the SIR/TAC group, but excess death from these complications was not observed. We conclude, GvHD prophylaxis approach of SIR/TAC is associated with reduced grades II–IV acute GvHD, comparable toxicity profile to MTX/TAC, and improved OS among patients with HCT-CI ⩾ 4.

INTRODUCTION

Acute GvHD is an important cause of mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). Thus, effective primary prevention of the syndrome is of critical importance.1,2 On the basis of phase III randomized trial evidence in the sibling and unrelated donor HCT setting, the standard pharmacological GvHD prevention approach includes tacrolimus (TAC) and methotrexate (MTX).3,4 Shortcomings have been described, including incomplete efficacy, failure to reduce chronic GvHD, and early toxicity associated with MTX.5

Other approaches have been tested, including TAC with either mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), or sirolimus (SIR). Evidence to date suggests no major advantage or deleterious effect on outcome when MMF/TAC is used for GvHD prevention.6,7 Single-center trials reached variable conclusions regarding the advantages of substituting SIR for MTX.8–11 The Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network conducted a multicenter, randomized phase III trial comparing SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC after HLA-matched, related peripheral blood HCT.12 No significant difference was seen in 114-day grades II–IV acute GvHD-free survival but showed more rapid engraftment and less oropharyngeal mucositis compared to MTX/TAC. These results suggested SIR/TAC was an acceptable alternative to MTX/TAC in the setting of matched related HCT.

On the basis of available evidence, several questions remain: importantly, insight into unique predictors of overall survival (OS) among patients treated with SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC is lacking. Thus, selection of a GvHD prophylaxis approach to optimize survival for individual patients is not possible. Second, comparative evidence for these approaches in the setting of unrelated donor transplants is limited. Similarly, only certain disease conditions, and myeloablative total-body irradiation-based regimens were examined in the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network trial, limiting generalizability. Therefore, we compared the outcomes of patients who underwent allogeneic HCT either with SIR/TAC or MTX/TAC GvHD prophylaxis at our institution. The primary goal of the current analysis was to identify unique predictors of OS among patients treated with SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC. A secondary goal was to characterize HCT outcomes following each approach to address current knowledge gaps.

METHODS

Data source and study design

We examined the consecutive series of HCT recipients (January 2008 to December 2013) at H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center. All consecutive transplant recipients consented to an institutional long-term follow-up data collection protocol. These observational data and additional targeted data abstraction were analyzed in this current retrospective analysis which was approved by institutional IRB (University of South Florida IRB).

Patients

We excluded umbilical cord blood transplants, as representation was limited, different GvHD prophylaxis was used (predominantly MMF/cyclosporine), and disproportionately higher mortality was observed (data not shown). Patients who received MMF/cyclosporine (n = 58), MMF/TAC (n = 88) or SIR/post-transplant cyclophosphamide (n = 3) were excluded from all analyses. Dose/schedule and therapeutic monitoring of immune suppressive agents (SIR, TAC, MTX) followed institutional standard practices.

The primary analysis compared SIR/TAC (n = 293) vs MTX/TAC (n = 414) by the principle of intention to treat. Patients treated on phase 2 trial (n = 74) comparing SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC were included in this analysis.11 Patients with matched sibling or matched unrelated donors (n = 15) who received SIR/TAC with either ustekinumab or placebo in a randomized blinded clinical trial (NCT NCT01713400), and those mismatched unrelated donors (n = 7) treated with MTX/TAC with visilizumab (NCT NCT00720629), or MTX/TAC with bortezomib (n = 1) were excluded. Patients who had MTX dose reduction or elimination were analyzed by intention to treat in the MTX/TAC group.

Pre-transplant variables

Comprehensive patient, disease, and HCT characteristics were collected. HCT donor and recipient variables included age, gender (female donor/male recipient vs others), cytomegalovirus and ABO matching, Karnofsky performance status (KPS), hematopoietic cell transplantation-comorbidity index (HCT-CI),13 pre-HCT liver function tests (aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, total bilirubin) and creatinine, body mass index in kg/m2 (underweighto18.5, normal 18.5–24.9, overweight 25–29.9, obese 30 or greater), cardiac ejection fraction, pulmonary function values (% predicted values for forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity, adjusted diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCOadj)), and ferritin. Variables included within the HCT-CI (creatinine, ejection fraction, FEV1, aspartate aminotransferase, ALT and bilirubin) were not considered separately as prognostic variables in the analysis. Disease variables included diagnosis and remission status at time of HCT. Disease diagnoses were collapsed into summary categories of acute leukemias (acute myelogenous, lymphoblastic and biphenotypic leukemias), lymphoproliferative disorders (non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma and CLL), plasma cell dyscrasias (multiple myeloma and other plasma cell disorders), myelodysplastic syndrome, chronic myeloproliferative diseases (myeloproliferative neoplasm and chronic myelogenous leukemia) and bone marrow failure syndromes (severe aplastic anemia and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria). Pre-HCT remission status was grouped as CR, partial- or very good partial response, stable (SD) or refractory disease and others. The disease risk index was not used for classification, given diagnoses in our series (aplastic anemia, bone marrow failure syndromes) not included in the disease risk index, and incomplete cytogenetic information in our series. Additional transplantation variables included donor type (matched sibling (MRD), ⩾ 8/8 unrelated donor (MUD), mismatched unrelated donor (MMUD)), graft source (bone marrow, peripheral blood mobilized stem cells), use of anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG), and HCT conditioning regimen. Conditioning regimens were grouped based on intensity: (1) The standard myeloablative regimen consists of IV fludarabine at 40 mg/m2 and IV busulfan (starting dose 130–145 mg/m2) each daily × 4 total days. Busulfan pharmacokinetic samples are obtained, and the final two doses are adjusted to target an average daily busulfan area under the curve of 5300 μm/L*min per day. (2) Escalated dose busulfan was examined in a prospective trial (NCT 00361140) with targeted average daily area under the curve values of 6000, 7500 and 9000 μm/L*min per day, respectively.14 (3) Reduced toxicity regimens included IV busulfan/fludarabine with targeted average daily area under the curve of 3500 μm/L*min per day, fludarabine (40 mg/m2/day × 4 days)/(IV busulfan 3.2 mg/kg × 2 days) and fludarabine (30 mg/m2/day × 4 days)/melphalan (140 mg/m2 single dose). (4) Non-myeloablative regimens included fludarabine (25 mg/m2/day × 5 doses)/cyclophosphamide (50 mg/kg/day × 2 doses), fludarabine (30 mg/m2/day × 3 days)/2 Gy TBI, and cyclophosphamide 50 mg/kg/day × 4 days/equine ATG (30 mg/kg × 3 doses). ATG use was greatest in MMUD (71% of cases) followed by MUD (3%) and MRD (2%). No significant interaction was detected between GvHD prophylaxis group and either donor type (MMUD, MUD or MRD) or ATG use (yes/no) for any of the examined outcomes.

Study end points

The primary end point was OS, calculated from HCT until death from any cause. Surviving patients were censored at last follow-up. Causes of death were summarized as follows: Relapse (standard relapse/progression definitions for each condition); GvHD (acute or chronic GvHD as primary contributor to death); infection (bacterial, fungal, or viral systemic infection); hepatic veno-occlusive disease (VOD) and liver complications (VOD/SOS or liver failure from other sources); thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) (TMA as primary contributor to death); pulmonary (respiratory failure inclusive of infectious etiology, acute respiratory distress syndrome, alveolar hemorrhage, or other); other organ failure (single- or multi-organ failure including cardiac, central nervous system, gastrointestinal or renal etiology); and others (malignancy other than primary indication for HCT, suicide, accidental death).

Secondary end points included non-relapse mortality (NRM), relapse, grades II–IV and grades III–IV acute GvHD, chronic GvHD, TMA, VOD/SOS and acute kidney injury (AKI). NRM was defined as death in the absence of relapse. Acute GvHD and chronic GvHD scoring was performed using consensus criteria.15,16 VOD/SOS was characterized using modified Seattle Criteria with presence of at least two of the following: hyperbilirubinemia ⩾ 2 mg/dL, hepatomegaly or right upper quadrant pain, and weight gain/ascites of >2% of baseline body weight.17 VOD/SOS that met these criteria but occurred >20 days post HCT was included. TMA definition and grading was based on Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network toxicity committee consensus Criteria.18 For the study of AKI, all serial creatinine values from time of HCT until death or last follow-up were studied with reference to the immediate pre-HCT creatinine. AKI was defined as increase in creatinine (Cr) ⩾ 1.5 × pre-HCT value. The severity of kidney injury was categorized as stage 1 if increase in Cr of 1.5–1.9 × baseline, stage 2 if increase in Cr of 2.0 to 2.9 × baseline and stage 3 if increase Cr of ⩾ 3 × baseline.19

Statistical analysis

Patient- and donor-, disease- and transplantation-related variables were summarized by descriptive statistics. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for continuous variables while χ2-test was used for categorical. Survival data were studied using the Kaplan-Meier method, and compared across groups using the log-rank test. For analysis of GvHD-free/relapse-free survival (GRFS),20 this composite end point was estimated as time from HCT to first event of the following: grade III/IV acute GvHD, chronic GvHD requiring immune suppressive therapy, relapse, or death. The cumulative incidence of NRM, relapse, grades II–IV and grades III–IV acute GvHD, chronic GvHD, AKI, VOD/SOS and TMA were estimated. Relapse was a competing risk event for NRM, and death was the competing risk event for relapse. For other studied outcomes, relapse and death were competing risk events. Cumulative incidence of outcomes was compared by Gray’s test.21 Given median follow up for surviving patients (SIR/TAC 23.7 months, range 11.1–73.1 months vs MTX/TAC 46.7 months, range 11.6–87.1 months), outcome plots present data through 24 months.

Multivariable analysis procedures examined all pre-HCT patient and donor, disease, and transplantation variables using the Cox proportional hazards regression model for OS, and the Fine-Gray regression model22 for NRM. None of the tested variables violated the proportional hazards assumption. All variables were tested for association with outcome, and those with P<0.05 were entered into the model. Interactions between the GvHD prophylaxis group and all other predictor variables were tested to discern unique predictors of OS and NRM among the SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC groups. Backward elimination was used to select variables for the final multivariable model. Variables with P-value>0.05 were excluded, except that GvHD prophylaxis group was retained in all models regardless of P-value.

The following secondary analyses were conducted: (1) predictive models were developed from the multivariable analysis results from the primary analyses for OS and NRM. Log-hazard ratio-based risk scores were developed for those final variables with P-value<0.05, and scores assigned to individual subjects. Total scores were computed, and the study population divided into low, intermediate, and high-risk groups based on the distribution of scores (by 33rd and 67th percentile cut points). (2) Separate models examined post-HCT variables (time to neutrophil and platelet engraftment, respectively, maximum acute GvHD, and maximal chronic GvHD) as predictors of OS and NRM. (3) OS and NRM were examined from time of chronic GvHD diagnosis among the sub-group affected by chronic GvHD. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 and R (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Patient- and donor-, disease- and transplant-related variables by GvHD prophylaxis group are summarized in Table 1. The SIR/TAC and MTX/TAC groups were largely well matched for all considered variables, except for differences in recipient age, conditioning regimen, ATG use and recipient/donor gender matching.

Table 1.

Demographics by GvHD prophylaxis group

| Variable | MTX/TAC (n = 414) | SIR/TAC (n = 293) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient age (years) | 52 [19, 74] | 56 [19, 76] | < 0.001 |

| Donor age (years) | 38 [17, 76] | 32 [17, 73] | 0.052 |

| Creatinine pre-HCT (mg/dL) | 0.8 [0.4, 2.3] | 0.8 [0.4, 1.9] | 0.65 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 60.8 [35, 74.2] | 60.5 [35, 79] | 0.98 |

| FEV1 (%) | 94 [50, 136] | 95.5 [48, 144] | 0.89 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 1160 [5.5, 19200] | 1080 [15.7, 11600] | 0.16 |

| AST (U/L) | 30 [6, 217] | 28 [8, 229] | 0.39 |

| ALT (U/L) | 29 [11, 219] | 32 [6, 177] | 0.08 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.5 [0.2, 1.9] | 0.5 [0.2, 2.8] | 0.15 |

| HCT-CI | 0.22 | ||

| 0 | 102 (27%) | 63 (23%) | |

| 1 | 68 (18%) | 48 (17%) | |

| 2 | 73 (19%) | 47 (17%) | |

| 3 | 67 (18%) | 50 (18%) | |

| ⩾ 4 | 69 (18%) | 71 (25%) | |

| KPS | 0.25 | ||

| 100 | 66 (16%) | 60 (21%) | |

| 90 | 239 (58%) | 164 (57%) | |

| ⩽ 80 | 106 (26%) | 66 (23%) | |

| Conditioning regimen | < 0.001 | ||

| Standard myeloablative | 221 (53%) | 155 (53%) | |

| Escalated dose busulfan | 32 (8%) | 4 (1%) | |

| Non-myeloablative | 24 (6%) | 11 (4%) | |

| Reduced toxicity | 137 (33%) | 123 (42%) | |

| Diagnosis | 0.06 | ||

| Acute leukemias | 186 (45%) | 136 (46%) | |

| Bone marrow failure syndromes | 15 (4%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Lymphoproliferative | 82 (20%) | 63 (22%) | |

| Chronic myeloproliferative | 27 (7%) | 23 (8%) | |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 69 (17%) | 55 (19%) | |

| Plasma cell dyscrasias | 35 (8%) | 14 (5%) | |

| Donor source | 0.05 | ||

| Matched sibling | 110 (27%) | 89 (30%) | |

| Matched unrelated | 210 (51%) | 159 (54%) | |

| Mismatched unrelated | 92 (22%) | 44 (15%) | |

| ATG use | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 329 (79%) | 264 (90%) | |

| Yes | 85 (21%) | 29 (10%) | |

| Gender (donor/recipient) | 0.006 | ||

| Female/male | 97 (24%) | 96 (33%) | |

| Others | 315 (76%) | 196 (67%) | |

| Graft source | 0.54 | ||

| PBMC | 408 (99%) | 287 (98%) | |

| BM | 6 (1%) | 6 (2%) | |

| CMV serostatus (donor/recipient) | 0.78 | ||

| − / − | 97 (27%) | 73 (28%) | |

| − /+ | 107 (30%) | 83 (32%) | |

| +/ − | 41 (12%) | 34 (13%) | |

| +/+ | 108 (31%) | 70 (27%) | |

| Remission status | 0.06 | ||

| CR | 221 (55%) | 164 (56%) | |

| VGPR or PR | 59 (15%) | 24 (8%) | |

| SD or refractory | 102 (25%) | 84 (29%) | |

| Others | 22 (5%) | 21 (7%) |

Abbreviations: ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; ATG = anti-thymocyte globulin; BM = bone marrow; CI = comorbidity index; CMV = cytomegalovirus; HCT = hematopoietic cell transplantation; MTX = methotrexate; PBMC = peripheral blood mononuc-lear cells; PR = partial response; SD = stable disease; SIR = sirolimus; TAC = tacrolimus; VGPR = very good partial response; VOD = veno-occlusive disease.

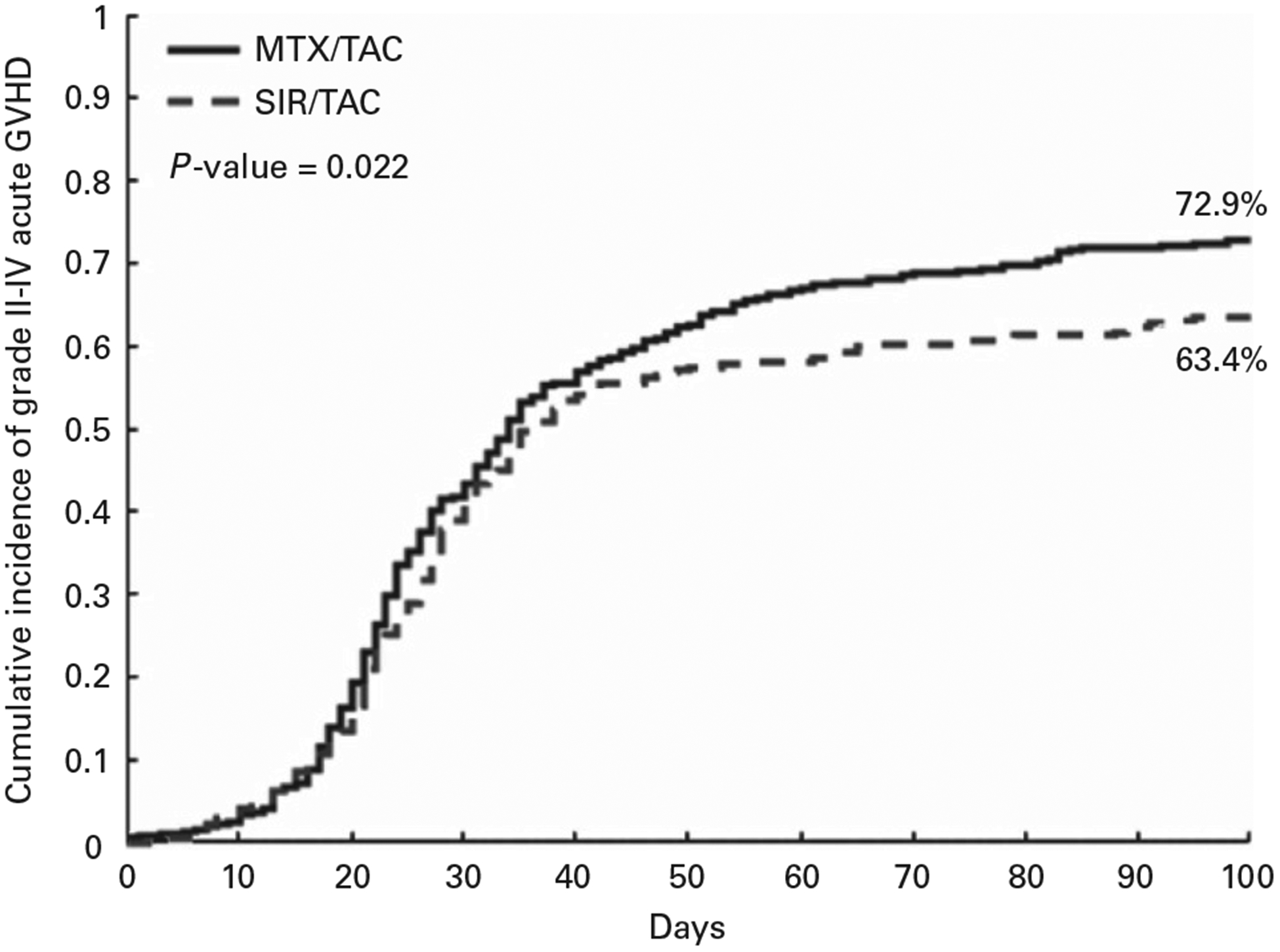

GvHD outcomes

The day 100 cumulative incidence of grades II–IV acute GvHD was significantly reduced in the SIR/TAC group vs the MTX/TAC group (63.4 vs 72.9%) (Figure 1). An ~ 10% reduction in grades II–IV acute GvHD was seen in both matched sibling and unrelated donors (Supplementary Figures S1a–b). A smaller difference was seen in mismatched unrelated HCT (Supplementary Figure S1c). Cumulative incidence of day 100 grades II–IV acute GvHD was 63.4 vs 73.1% for SIR/TAC and MTX/TAC, respectively. No significant differences were seen in grades III–IV acute GvHD (at 100 days SIR/TAC 12.8% vs MTX/TAC 13.8%, P = 0.68). Maximal acute GvHD organ staging according to GvHD prophylaxis group is presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of grades II–IV acute GvHD. A full colour version of this figure is available at the Bone Marrow Transplantation journal online.

The cumulative incidence of any grade chronic GvHD and NIH moderate-severe chronic GvHD did not significantly differ between SIR/TAC and MTX/TAC (Supplementary Figure S2). Moderate-severe chronic GvHD at 2-year was 41.9% vs 40.8% for SIR/TAC and MTX/TAC respectively. In addition, a sub-group analysis of those with chronic GvHD did not demonstrate different OS or NRM after chronic GvHD diagnosis (Supplementary Table S2). Maximal chronic GvHD organ scores did not significantly differ between groups (Supplementary Table S3).

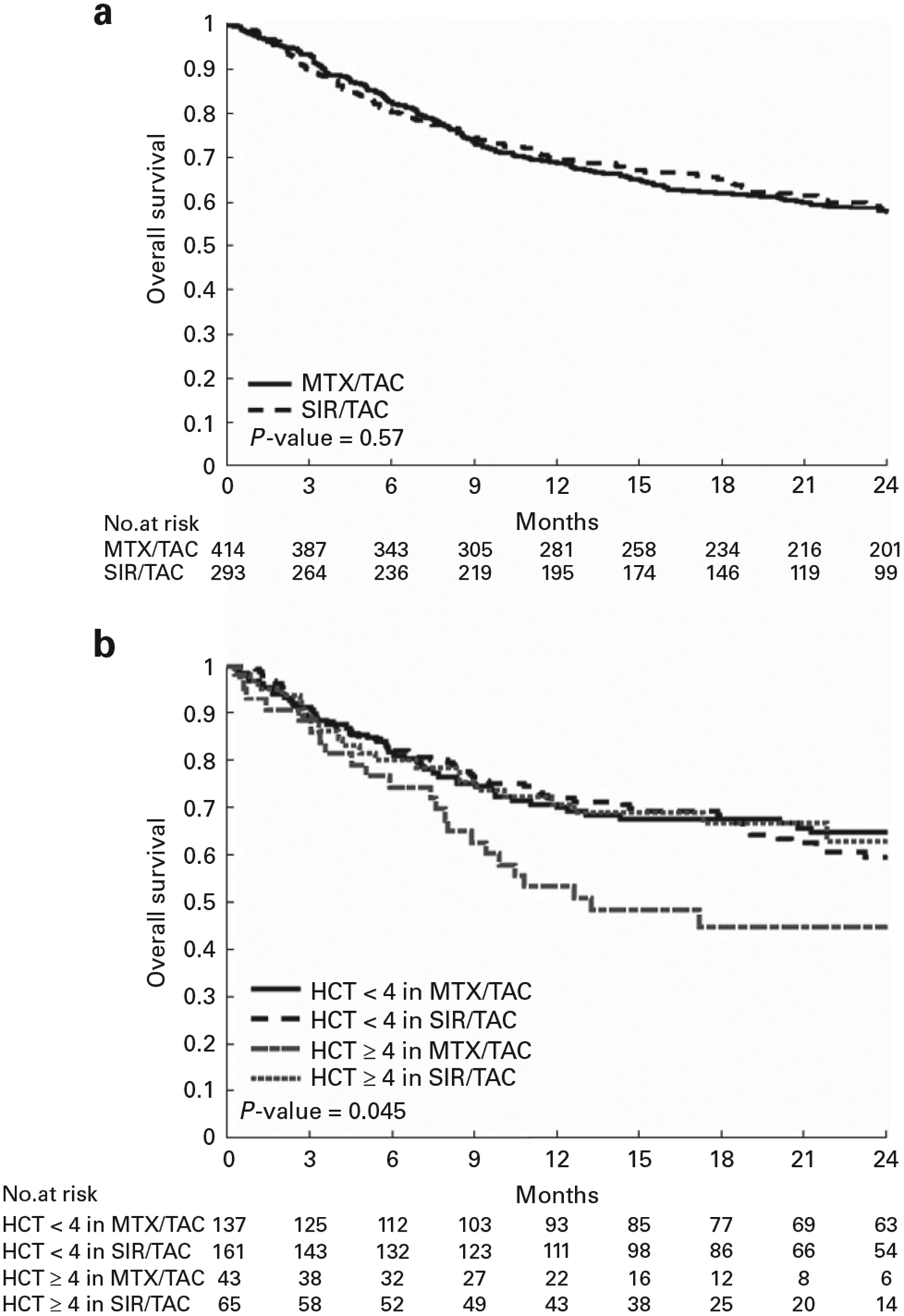

Overall survival

No difference was seen in OS comparing the SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC groups overall (Figure 2a). Causes of death, however, differed (Table 2). A significant interaction was detected between GvHD prophylaxis group and HCT-CI score for OS. Further analyses demonstrated significantly improved OS for SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC among those with HCT-CI ⩾ 4 (Table 3 and Figure 2b). Comparing patients with HCT-CI ⩾ 4 across GvHD prophylaxis groups, there were no significant differences in other patient, disease, or transplantation variables, except for aspartate aminotransferase and total bilirubin (Supplementary Table S4). The proportions of individual comorbidities that resulted in an overall HCT-CI score of ⩾ 4 did not differ (Supplementary Table S5). Causes of death among the HCT-CI ⩾ 4 group recapitulated differences seen in the overall study population (Supplementary Table S6). GRFS was calculated but did not show significant differences between the groups (Supplementary Figures S4a–c).

Figure 2.

(a) Overall survival SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC. (b) Overall survival SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC in HCT-CI<4 and ⩾ 4.

Table 2.

Causes of death by GvHD prophylaxis group

| Cause of death | MTX/TAC (n = 194) | SIR/TAC (n = 129) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse | 105 (54%) | 56 (43%) | 0.045 |

| GvHD | 19 (10%) | 12 (9%) | |

| Infections | 22 (11%) | 13 (10%) | |

| Pulmonary complications | 9 (5%) | 17 (13%) | |

| Other organ failure | 13 (7%) | 16 (12%) | |

| VOD and liver complications | 7 (4%) | 2 (2%) | |

| Thrombotic microangiopathy | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Others | 17 (9%) | 13 (10%) |

Abbreviations: MTX = methotrexate; SIR = sirolimus; TAC = tacrolimus; VOD = veno-occlusive disease.

Table 3.

OS and NRM univariable and multivariable analyses according to GvHD prophylaxis group

| Variable | Level | OS univariable | OS multivariable | NRM univariable | NRM multivariable | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | ||

| Conditioning regimen | Escalated dose busulfan vs standard myeloablative | 1.16 | 0.72–1.86 | 0.55 | 1.28 | 0.63–2.58 | 0.50 | ||||||

| Non-myeloablative vs standard myeloablative | 0.16 | 0.05–0.51 | 0.002 | 0.43 | 0.14–1.36 | 0.15 | |||||||

| Reduced toxicity vs standard myeloablative | 1.23 | 0.98–1.54 | 0.08 | 1.62 | 1.17–2.23 | 0.004 | |||||||

| Diagnosis | Bone marrow failure syndromes, etc vs acute leukemias | 0.31 | 0.10–0.97 | 0.044 | 0.88 | 0.26–2.98 | 0.84 | ||||||

| Lymphoproliferative vs acute leukemias | 0.77 | 0.57–1.04 | 0.09 | 1.01 | 0.65–1.55 | 0.98 | |||||||

| Chronic myeloproliferative vs acute leukemias | 0.70 | 0.43–1.13 | 0.14 | 1.20 | 0.65–2.21 | 0.56 | |||||||

| Myelodysplastic syndrome vs acute leukemias | 1.02 | 0.76–1.38 | 0.88 | 1.35 | 0.90–2.02 | 0.14 | |||||||

| Plasma cell dyscrasias vs acute leukemias | 1.33 | 0.90–1.97 | 0.15 | 1.76 | 1.01–3.08 | 0.046 | |||||||

| Donor source | Matched unrelated vs matched sibling | 0.92 | 0.72–1.19 | 0.52 | 1.48 | 1.00–2.19 | 0.051 | 1.41 | 0.95–2.10 | 0.090 | |||

| Mismatched unrelated vs matched sibling | 0.97 | 0.71–1.34 | 0.87 | 1.72 | 1.08–2.73 | 0.023 | 1.81 | 1.14–2.89 | 0.013 | ||||

| GvHD group | SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC | 1.07 | 0.85–1.34 | 0.56 | See details below | 0.074 | 1.32 | 0.96–1.80 | 0.09 | 1.35 | 0.98–1.86 | 0.063 | |

| HCT-CI | ⩾ 4 vs < 4 | 1.44 | 1.10–1.88 | 0.009 | See details below | 0.014 | 1.62 | 1.14–2.31 | 0.007 | ||||

| Karnofsky performance | 90 vs 100 | 1.30 | 0.94–1.80 | 0.12 | 1.30 | 0.84–2.00 | 0.24 | 1.80 | 1.06–3.04 | 0.029 | 1.86 | 1.11–3.12 | 0.019 |

| Status | ⩽ 80 vs 100 | 1.91 | 1.34–2.73 | < 0.001 | 2.05 | 1.28–3.29 | 0.003 | 2.71 | 1.55–4.73 | 0.001 | 2.81 | 1.61–4.90 | 0.0003 |

| Recipient age | Per 10 years old increase | 1.11 | 1.02–1.21 | 0.019 | 1.24 | 1.09–1.41 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Donor age | Per 10 years old increase | 1.09 | 1.00–1.18 | 0.055 | 1.09 | 0.97–1.23 | 0.14 | ||||||

| Ferritin | Per 500 (ng/mL) increase | 1.06 | 1.03–1.09 | < 0.0001 | 1.06 | 1.03–1.09 | 0.0001 | 1.04 | 1.00–1.08 | 0.043 | |||

| Remission status | VGPR or PR vs CR | 0.93 | 0.65–1.32 | 0.67 | 1.12 | 0.68–1.84 | 0.65 | ||||||

| SD or refractory vs CR | 1.00 | 0.62–1.60 | 0.99 | 1.43 | 0.79–2.61 | 0.24 | |||||||

| Others vs CR | 1.07 | 0.83–1.38 | 0.61 | 1.29 | 0.91–1.85 | 0.16 | |||||||

| GvHD group*HCT-CI | 0.013 | ||||||||||||

| Effects of HCT-CI | HCT-CI ⩾ 4 vs < 4 at MTX/TAC | 1.86 | 1.14–3.04 | 0.014 | |||||||||

| HCT-CI ⩽ 4 vs < 4 at SIR/TAC | 0.78 | 0.48–1.26 | 0.31 | ||||||||||

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; HCT-CI = hematopoietic cell transplant-comorbidity index; HR = hazards ratio; MTX = methotrexate; NRM = non-relapse mortality; OS = overall survival; SIR = sirolimus; TAC = tacrolimus; VGPR = very good partial response.

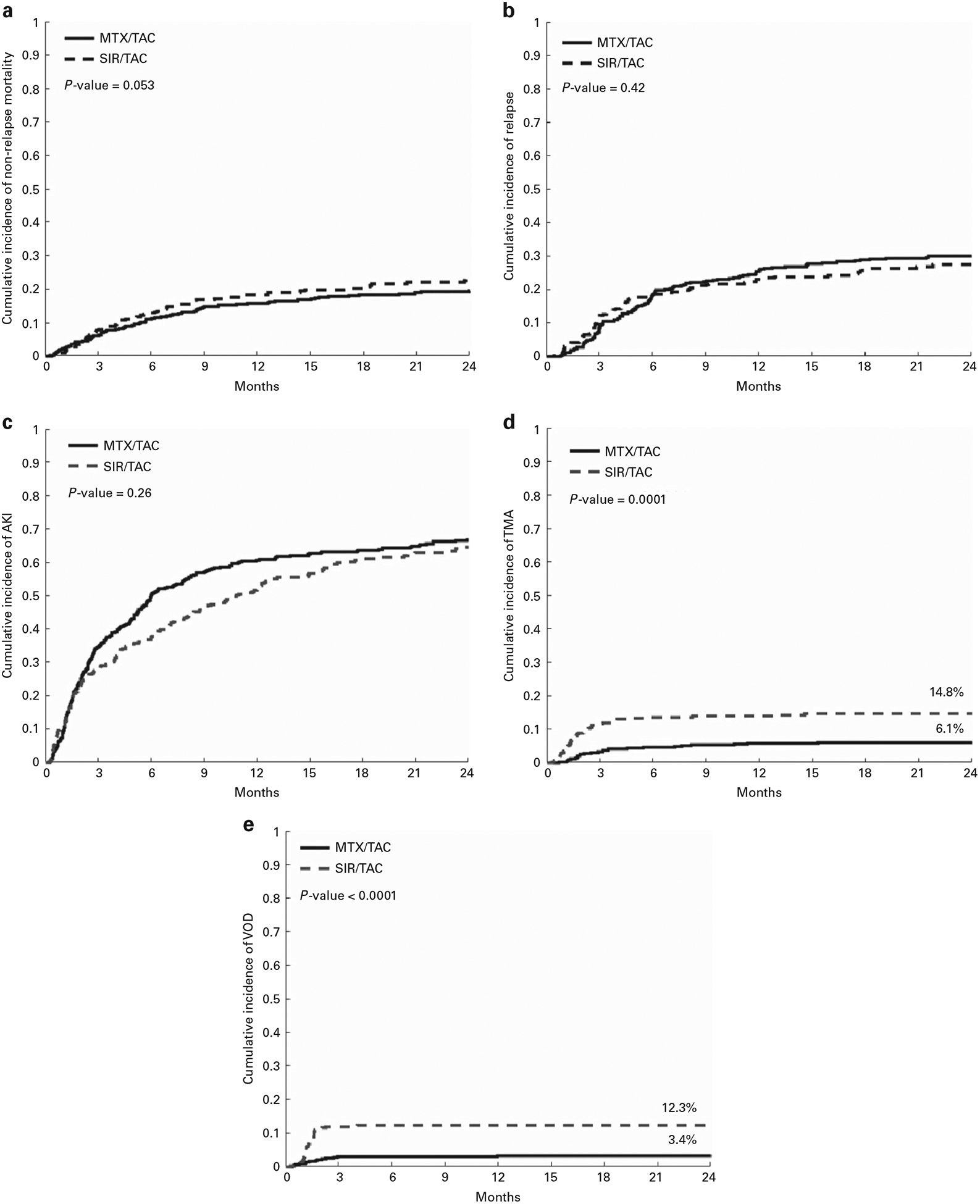

Non-relapse mortality and toxicity outcomes

NRM did not differ between SIR/TAC and MTX/TAC (Figure 3a and Table 3), and no significant interactions were detected. Significant predictors of NRM (reduced KPS, and mismatched unrelated transplants) were common between the groups. No difference in malignancy relapse was observed (Figure 3b). No difference in any AKI (Figure 3c) or stages 2–3 AKI (not shown) was detected. In keeping with prior evidence, TMA and VOD/SOS were increased in the SIR/TAC group (Figures 3d and e), yet were infrequent causes of death (Table 2).

Figure 3.

(a) Cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC. (b) Cumulative incidence of relapse SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC. (c) Cumulative incidence of acute kidney injury SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC. (d) Cumulative incidence of thrombotic microangiopathy SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC. (e) Cumulative incidence of VOD/SOS SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC. A full colour version of this figure is available at the Bone Marrow Transplantation journal online.

Secondary analyses

Hazard ratio weighted risk scores segregated distinct risk sub-groups for OS and NRM (Supplementary Figures S3a and b). Low- vs high-risk patients had ~ 20% absolute improvement in OS at 2 years, and similar magnitude of difference in NRM.

Maximum acute GvHD and chronic GvHD were both significantly associated with OS and NRM (not shown).

DISCUSSION

The primary objective of the analysis was to discern unique predictors of OS among patients treated with SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC to guide rational selection of primary immune suppression prophylaxis for individual patients. OS was chosen based on its uncontested importance as a primary end point. Although OS was similar across groups in total, we identified a significant interaction with HCT-CI, and demonstrated that OS was significantly better among those with HCT-CI ⩾ 4 treated with SIR/TAC vs MTX/TAC. The excess mortality events in the MTX/TAC group were observed in the range of 6–12 months after HCT and beyond, and worsened mortality from relapse post HCT and infection were more apparent in the HCT-CI ⩾ 4 group treated with MTX/TAC (Supplementary Table S6). Our analyses suggest that this effect is not driven by important differences in other patient-, disease- or HCT variables across the SIR/TAC and MTX/TAC patients with HCT-CI ⩾ 4, or the distribution of individual comorbidities that resulted in this overall high-risk status. While these findings bear further validation, they support a benefit of SIR/TAC among patients with HCT-CI ⩾ 4.

No other unique predictors of OS according to GvHD prophylaxis regimen delivered were identified. Thus, our data do not support preferential selection of SIR/TAC or MTX/TAC according to numerous other routinely assessed patient and donor, disease, and HCT variables to optimize survival. Common variables that adversely affected outcomes included increased ferritin and poor KPS (OS outcome), as well as poor KPS, and mismatched unrelated donor HCT (NRM outcome). The use of either considered GvHD prophylaxis approach failed to mitigate the risks associated with these largely non-modifiable factors. However, these factors can be used for risk stratification and counseling of HCT patients on anticipated prognosis.

As a secondary objective, we have assessed benefits and adverse consequences of each approach. These data support a significant reduction in 100 day grades II–IV acute GvHD. The magnitude of this effect was similar in matched sibling and matched unrelated donor HCT. Similar findings were recently reported showing that addition of SIR to GvHD prophylaxis in reduced intensity allogeneic HCT for lymphomas is associated with a significantly lower risk of acute GvHD.23 Another trial comparing MTX/cyclosporine to SIR/TAC did not show a reduction in acute GvHD but their study mandated use of ATG for all matched unrelated donor HCT.24 The incidence of acute GvHD reported in our study is in keeping with our institutional benchmarks, and is likely influenced by the rate of GI involvement.25 Conversely, there were no significant differences in grades III–IV acute GvHD, acute GvHD in mismatched unrelated donor HCT (although grades III–IV acute GvHD was low and influenced by ATG), or moderate-severe chronic GvHD. In contrast to a prior randomized trial,26 duration of SIR therapy was not controlled in this observational study. This may explain the lack of difference between SIR/TAC and MTX/TAC in chronic GvHD incidence and organ severity in this series.

We found no differences in non-relapse mortality or relapse after HCT. Excess TMA and VOD/SOS observed in the SIR/TAC group recapitulates prior evidence.27 However, these were infrequent, and death due to these complications was not increased. In addition, VOD/SOS in the SIR/TAC group had altered phenotype, with prolonged time to onset and decreased severity (data not shown). Finally, comprehensive analysis of AKI demonstrated that, while this complication is common (overall, approximately two-third of patients by 24 months post HCT), there was no significant difference between groups. These data overall support the safety profile of SIR/TAC.

We note the following limitations: The impact of selection bias cannot be completely addressed in this observational study. Despite the scope of this large consecutive series, generalizability is poor for groups not represented in this analysis (for example, pediatric patients, certain diagnosis categories, umbilical cord blood HCT and TBI-based myeloablative regimens). The absolute magnitude of benefit in acute GvHD reduction is limited, and we acknowledge other investigational approaches may lead to additional benefit beyond these commonly used approaches.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Bone Marrow Transplantation website (http://www.nature.com/bmt)

REFERENCES

- 1.Levine JE, Logan B, Wu J, Alousi AM, Ho V, Bolaños-Meade J et al. Graft-versus-host disease treatment: predictors of survival. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2010; 16: 1693–1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pidala J, Anasetti C. Glucocorticoid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2010; 16: 1504–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nash RA, Antin JH, Karanes C, Fay JW, Avalos BR, Yeager AM et al. Phase 3 study comparing methotrexate and tacrolimus with methotrexate and cyclosporine for prophylaxis of acute graft-versus-host disease after marrow transplantation from unrelated donors. Blood 2000; 96: 2062–2068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ratanatharathorn V, Nash RA, Przepiorka D, Devine SM, Klein JL, Weisdorf D et al. Phase III study comparing methotrexate and tacrolimus (prograf, FK506) with methotrexate and cyclosporine for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplantation. Blood 1998; 92: 2303–2314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cutler C, Li S, Kim HT, Laglenne P, Szeto KC, Hoffmeister L et al. Mucositis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a cohort study of methotrexate- and non-methotrexate-containing graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis regimens. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005; 11: 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kharfan-Dabaja M, Mhaskar R, Reljic T, Pidala J, Perkins JB, Djulbegovic B et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus methotrexate for prevention of graft-versus-host disease in people receiving allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; (7): CD010280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eapen M, Logan BR, Horowitz MM, Zhong X, Perales M-A, Lee SJ et al. Bone marrow or peripheral blood for reduced-intensity conditioning unrelated donor transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 364–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cutler C, Li S, Ho VT, Koreth J, Alyea E, Soiffer RJ et al. Extended follow-up of methotrexate-free immunosuppression using sirolimus and tacrolimus in related and unrelated donor peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Blood 2007; 109: 3108–3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furlong T, Kiem H-P, Appelbaum FR, Carpenter PA, Deeg HJ, Doney K et al. Sirolimus in combination with cyclosporine or tacrolimus plus methotrexate for prevention of graft-versus-host disease following hematopoietic cell transplantation from unrelated donors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2008; 14: 531–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez R, Nakamura R, Palmer JM, Parker P, Shayani S, Nademanee A et al. A phase II pilot study of tacrolimus/sirolimus GVHD prophylaxis for sibling donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation using 3 conditioning regimens. Blood 2010; 115: 1098–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pidala J, Kim J, Jim H, Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Nishihori T, Fernandez HF et al. A randomized phase II study to evaluate tacrolimus in combination with sirolimus or methotrexate after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Haematologica 2012; 97: 1882–1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cutler C, Logan B, Nakamura R, Johnston L, Choi S, Porter D et al. Tacrolimus/sirolimus vs tacrolimus/methotrexate as GVHD prophylaxis after matched, related donor allogeneic HCT. Blood 2014; 124: 1372–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, Baron F, Sandmaier BM, Maloney DG et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood 2005; 106: 2912–2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perkins JB, Kim J, Anasetti C, Fernandez HF, Perez LE, Ayala E et al. Maximally tolerated busulfan systemic exposure in combination with fludarabine as conditioning before allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2012; 18: 1099–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, Socie G, Wingard JR, Lee SJ et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005; 11: 945–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann HG, Beatty P, Hows J et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant 1995; 15: 825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald GB, Sharma P, Matthews DE, Shulman HM, Thomas ED. Venocclusive disease of the liver after bone marrow transplantation: diagnosis, incidence, and predisposing factors. Hepatology 1984; 4: 116–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho VT, Cutler C, Carter S, Martin P, Adams R, Horowitz M et al. Blood and marrow transplant clinical trials network toxicity committee consensus summary: thrombotic microangiopathy after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005; 11: 571–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kellum JA, Lameire NKDIGO AKI Guideline Work Group. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (Part 1). Crit Care 2013; 17: 204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holtan SG, DeFor TE, Lazaryan A, Bejanyan N, Arora M, Brunstein CG et al. Composite end point of graft-versus-host disease-free, relapse-free survival after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 2015; 125: 1333–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray R A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of competing risk. Ann Stat 1988; 16: 1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fine J, Gray R. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999; 94: 496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armand P, Kim HT, Sainvil M-M, Lange PB, Giardino AA, Bachanova V et al. The addition of sirolimus to the graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis regimen in reduced intensity allogeneic stem cell transplantation for lymphoma: a multi-centre randomized trial. Br J Haematol 2016; 173: 96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Törlén J, Ringdén O, Garming-Legert K, Ljungman P, Winiarski J, Remes K et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing cyclosporine/methotrexate and tacrolimus/sirolimus as graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica 2016; 101: 1417–1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin PJ, McDonald GB, Sanders JE, Anasetti C, Appelbaum FR, Deeg HJ et al. Increasingly frequent diagnosis of acute gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2004; 10: 320–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pidala J, Kim J, Alsina M, Ayala E, Betts BC, Fernandez HF et al. Prolonged sirolimus administration after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation is associated with decreased risk for moderate-severe chronic graft-versus-host disease. Haematologica 2015; 100: 970–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cutler C, Stevenson K, Kim HT, Richardson P, Ho VT, Linden E et al. Sirolimus is associated with veno-occlusive disease of the liver after myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2008; 112: 4425–4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.