Abstract

Background:

Accumulating evidence suggests that alternative RNA splicing has an important role in cancer development and progression by driving the expression of a diverse array of RNA and protein isoforms from a handful of genes. However, our understanding of the clinical significance of cancer-specific RNA splicing in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is limited.

Objective:

To characterize and validate a novel oncogene RNA splicing event discovered in patients with RCC and to correlate expression with clinical outcomes.

Design, setting, and participants:

Using DNA and RNA sequencing, we identified a novel epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) splicing alteration (EGFR_pr20CTF) in RCC tumor tissue.

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis:

We confirmed the frequency and specificity of the EGFR_pr20CTF variant by analyzing cohorts of patients from our institution (n = 699) and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; n = 832). Furthermore, we analyzed its expression in tumor tissue and a human kidney cancer cell line using reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. Variant expression was also correlated with survival and response to systemic therapy.

Results and limitations:

EGFR_pr20CTF expression was identified in 71.7% (n = 71/99) of patients with RCC in our institutional cohort and in 56.7% (n = 279/492) of patients in the TCGA cohort. EGFR_pr20CTF was found to be specific to clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), occurring in <0.2% of non-RCC tumors (n = 2/1091). High levels of EGFR_pr20CTF correlated with lower survival at 48 mo following immunotherapy (p = 0.036). The average survival in patients with high EGFR_pr20CTF expression was <16 mo.

Conclusions:

The EGFR_pr20CTF RNA splice variant occurs frequently, is specific to patients with advanced ccRCC, and is associated with a poor response to immunotherapy.

Patient summary:

Cancer-specific RNA alternative splicing may portend a poor prognosis in patients with advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Further investigation will help clarify whether EGFR_pr20CTF can be used as a biomarker for this patient population.

Keywords: Epidermal growth factor, receptor, Renal cell carcinoma, RNA splice variants, RNA sequencing

1. Introduction

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is one of the most widely activated oncogenes associated with the development and progression of several epithelial malignancies. EGFR activation is disease dependent and can occur via amplification, activating mutations and deletions of the kinase domain, or inactivating deletions of the extracellular domain [1–3]. Studies of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) have demonstrated that DNA-level EGFR alterations are rare, occurring in approximately 1–2% of cases; however, EGFR messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein expression can still be elevated and are correlated with unfavorable clinical outcomes [4,5].

Given the role of EGFR in cancer progression, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), which target the receptor, have been explored in several malignancies [6]. Unfortunately, in patients with RCC, clinical trials have shown no clear benefits in single-agent EGFR-specific TKI therapy [7,8]. However, multikinase inhibitors, such as sunitinib and pazopanib, have been shown to be effective and have become standard of care for the treatment of metastatic RCC (mRCC). In the first-line setting, the reported objective response rates for mRCC patients on multitargeted TKIs range from 25% to 31% [9]. Additionally, recent trials have demonstrated a benefit of newer targeted agents, such as lenvatinib and cabozantinib, which have expanded and differential receptor activity [9]. Although a few mRCC patients have exceptional responses to these drugs, most will progress; median overall survival (OS) ranges from 10.9 to 26.4 mo [9]. Currently, it is not possible to identify which patients will be refractory to certain systemic agents or to predict which patients will develop resistance after initially responding to therapy, as there are no known common mutations within receptor tyrosine kinases in RCC.

Apart from the von Hippel-Lindau mutation in clear cell RCC (ccRCC), most of the somatic mutations seen in ccRCC occur in a small handful of genes and at relatively low frequencies. Currently, none of these genomic alterations have been proved to be clinically actionable, although several have been associated with poor clinical outcomes [10]. In contrast, mRNA splicing alterations in RCC are not as well characterized as DNA alterations. Recently, there have been attempts to characterize novel splicing variants in different biological systems through RNA sequencing (RNAseq)-based approaches [11]. Chen et al [12] recently reported that EZH2 pre-mRNA splice variants are increased in RCC tissues and associated with increased proliferation, migration, and tumorigenicity in RCC cell lines. In this study, we aimed to characterize and validate the presence of a novel EGFR splicing variant, which we have called EGFR_pr20CTF, in RCC through an RNAseq-based approach.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Clinical samples and bioinformatics

Following institutional review board approval, we retrospectively obtained clinicopathological patient data from 2004 to 2018 from electronic medical records at a high-volume cancer center. All patients provided written consent to allow molecular characterization of their tissues as per our institutional Total Cancer Care (TCC) Protocol (MCC#14690; Advarra IRB Pro00014441). First, we used our institutional targeted sequencing assay, which includes DNA and RNA sequencing to identify gene fusions and splicing alterations, to study the tumors of a small cohort of seven patients with RCC. We identified a novel RNA splicing event at the C-terminus fragment exon 20 (EGFR_pr20CTF) in four of the seven patients.

To further investigate the frequency of this alternative splicing event, we identified 699 patients whose tumors had undergone whole-exome sequencing (WES), RNAseq of tumor, and germline DNA sequencing at our institution [13]. Of these, 99 specimens were collected from RCC tumors (89 primary and 10 metastatic tumors). Using RNAseq techniques, we aligned our institutional high-risk cohort with a human reference genome to detect the frequency of EGFR_pr20CTF alternate splicing events.

2.2. The Cancer Genome Atlas analyses

To assess the frequency and specificity of EGFR_pr20CTF in a larger cohort of patients, we analyzed the RNAseq from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). We identified 492 patients with kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), 190 with papillary RCC, and 50 with chromophobe RCC. We also evaluated adjacent normal tissue samples and a subset of non-RCC tumors from TCGA.

2.3. Gene expression (reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction) in tumor tissues and cell lines

To validate the presence of EGFR_pr20CTF in RCC, we performed reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using primers amplifying the novel EGFR_pr20CTF splice isoform junction in tumor tissues and a representative human RCC cell line. RNA was isolated and purified from tumor tissue and A-498 (HTB-44;ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) cells as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Next, RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA, which was then used to perform PCR using primers designed to target intron 20 and exon 21 of EGFR. The PCR products were visualized on agarose gel using gel electrophoresis. Normalization was performed relative to beta-actin.

2.4. Statistical analysis

To evaluate the potent prognostic power of EGFR_pr20CTF variant, we defined lower and higher groups of proportions of the variant and compared survival outcomes. AS the selection of an arbitrary cutpoint in a quantitative predictor leads to a multiple testing problem, we used the maximally selected rank statistics “maxstat” method that has been proved to provide not only an association test based on the exact distribution of maxstat, but also an estimate of a cutpoint as a simple classification rule regarding the survival outcome [14]. The associations between EGFR_pr20CTF expression and continuous variables were analyzed using the t test, and categorical variables were analyzed using the Fisher exact test. Survival outcome and other time-to-event outcome variables were compared using log-rank test or trend test. OS was calculated as the time from the date of pathological diagnosis to either the date of death or the date of last follow-up. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of radiological recurrence. Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves were created for OS and RFS endpoints. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 and R studio software.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and characterization of EGFR_pr20CTF in renal cell cancer tumors

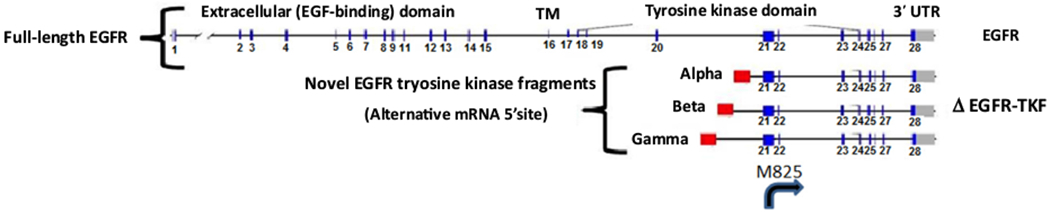

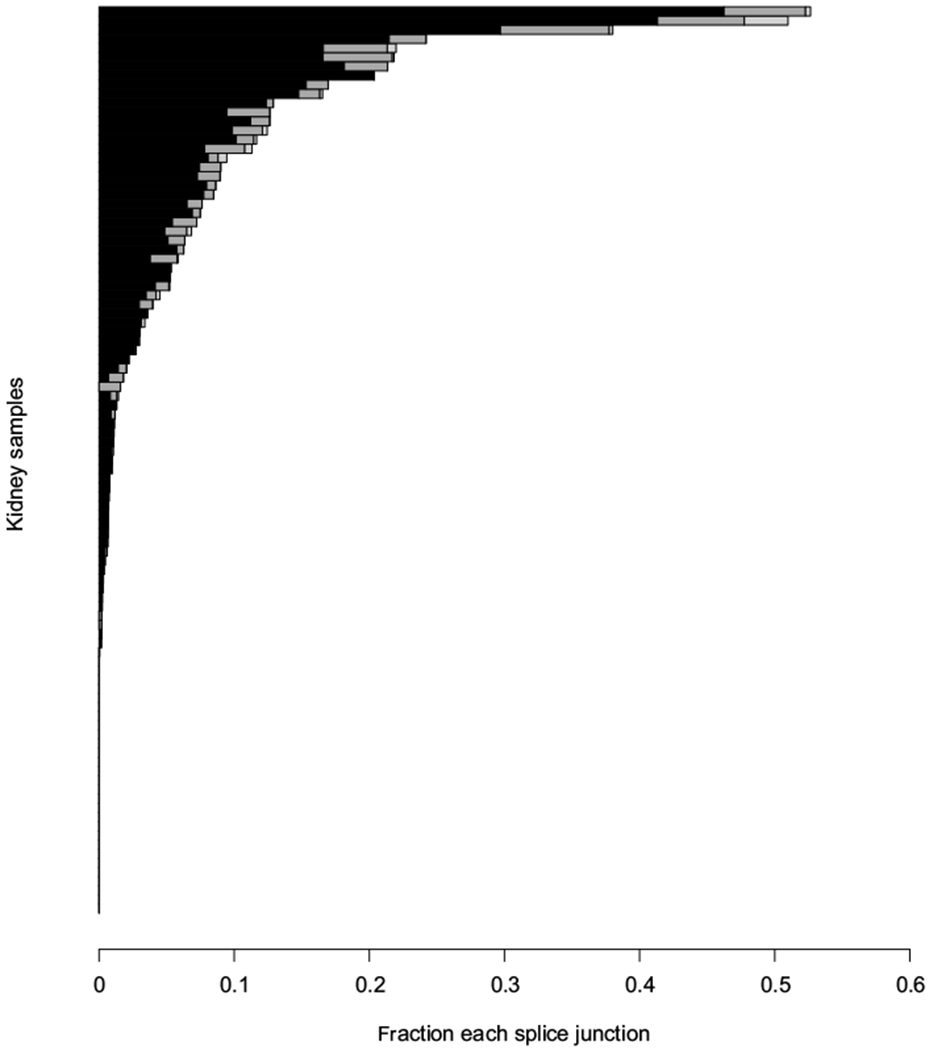

Tumors with EGFR_pr20CTF expression were identified in 71.7% (n = 71/99) of patients with RCC in our institutional cohort. The frequency of EGFR_pr20CTF was highest in patients with clear cell histology (76.1%, n = 67/88). We found that 90% (9/10) of metastatic specimens (all of which were ccRCC) had EGFR_pr20CTF. The clinical and pathological variables from this cohort can be found in Table 1. Three different splice forms were observed, which were labeled as alpha, beta, and gamma (Supplementary Table 1) on the basis of their increasing distances upstream from the exon 21 5′ binding site. The alpha isoform was the most common variant (Fig. 1). The distribution of the EGFR_pr20CTF isoforms across is detailed in Fig. 2. An oncoprint that shows mutational frequency across these frequently mutated genes and co-occurrence of EGFR_pr20CTF ccRCC patients is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Table 1 –

Demographics and baseline clinical characteristics of TCC RCC patients.

| Variables | TCC RCC patients, no. (%) (n = 99) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 30 (30.3) |

| Male | 69 (69.7) |

| Race | |

| Asian Indian or Pakistani | 2 (2.0) |

| Black | 2 (2.0) |

| Other | 5 (5.1) |

| White | 90 (90.9) |

| Tumor laterality | |

| Left | 59 (59.6) |

| Right | 40 (40.4) |

| Surgery type | |

| Partial nephrectomy | 10 (10.1) |

| Radical nephrectomy | 89 (89.9) |

| Specimen type for sequencing | |

| Metastatic | 10 (10.1) |

| Primary | 89 (89.9) |

| Fuhrman nuclear grade | |

| 2 | 21 (23.9) |

| 3 | 53 (60.2) |

| 4 | 14 (15.9) |

| NAa | 11 (−) |

| pT | |

| T1 | 24 (24.2) |

| T2 | 4 (4.0) |

| T3-T4 | 71 (71.7) |

| pN | |

| N0 | 27 (27.3) |

| N1 | 7 (7.1) |

| Nx | 65 (65.6) |

| Cytoreductive surgery | |

| No | 72 (72.7) |

| Yes | 27 (27.3) |

| Vitality | |

| Alive | 84 (84.8) |

| Dead | 15 (15.2) |

| Age at surgery (yr) | |

| Median (range) | 64 (39–89) |

| Pathological tumor size (cm) | |

| Median (range) | 7 (1.7–17.5) |

NA = not available; RCC = renal cell carcinoma; TCC = Total Cancer Care Protocol.

Eleven patients had renal cell carcinoma with either chromophobe or papillary histology, and were therefore not assigned a Fuhrman nuclear grade as this grading system has been validated only for clear cell histology.

Fig. 1 –

Exon map for EGFR splice variant C-terminus fragment isoforms. No 5′ splicing events are observed in these alternate forms, suggesting that they may be the beginning of a novel transcript. The second codon in exon 21, codon 825, is a start codon that encodes the amino acid methionine (g.7:55259415ߝ55259417), indicating that a protein product could arise from these novel splice forms, starting with M825 (EGFR NM_005228/NP_005219 1210 amino acids). This protein product would include the 386 C-terminal amino acids, including part of the kinase domain (region PTKc_EGFR, CDD:270683, 704–1016, M825 is at codon position 122 of 313 codons in this domain). EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor; mRNA = messenger RNA; TKF = tyrosine kinase fragment.

Fig. 2 –

Distribution of the EGFR splice variant C-terminus fragment isoforms across Moffitt Total Cancer Care cohort renal cell carcinoma samples. A fraction of each EGFR 5′ exon 21 splice junction that is represented by the EGFR splice variant C-terminus fragment isoforms, alpha (black), beta (dark gray), and gamma (light gray), is plotted for each patient in the Moffitt Total Cancer Care cohort (n = 99). EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor.

TCGA findings were consistent with our institutional RCC cohort results. We observed EGFR_pr20CTF in 56.7% (n = 279/ 492) of KIRC samples (Fig. 3). We compared the frequency of EGFR_pr20CTF with other commonly mutated genes in ccRCC by evaluating KIRC samples with available matching WES (n = 420/492; Supplementary Table 2). In this subcohort of 420 tumors, the frequency of EGFR_pr20CTF was 58.1% (n = 244), which makes it a more common alteration than many well-defined somatic ccRCC mutations.

Fig. 3 –

Distribution of the EGFR splice variant C-terminus fragment isoforms across The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) kidney samples. A fraction of each EGFR 5′ Exon 21 splice junction that is represented by the EGFR splice variant C-terminus fragment isoforms, alpha (black), beta (dark gray), and gamma (light gray), are plotted for each patient in the TCGA cohort: (A) TCGA kidney renal clear cell carcinoma tumor samples (n = 492), (B) TCGA kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma tumor samples (n = 190), (C) TCGA KICH tumor samples (n = 50), (D) TCGA kidney renal clear cell carcinoma adjacent normal samples (n = 69), (E) TCGA kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma adjacent normal samples (n = 28), and (F) TCGA KICH adjacent normal samples (n = 25). EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor; KICH = chromophobe kidney cancer; KIRC = kidney renal clear cell carcinoma; KIRP = kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma.

3.2. Specificity of EGFR_pr20CTF

We examined a cohort of 606 non-RCC tumors from our institutional TCC cohort and up to 100 samples from each tumor type from the TCGA cohort for a total of 1091 samples. Only samples with >10 total reads crossing the EGFR junctions of interest were included in the analyses. The EGFR_pr20CTF event was found only in a single sarcoma tumor and a single lung adenocarcinoma tumor sample, which represented <0.2% of non-RCC tumor samples and normal tissues (n = 2/1091).

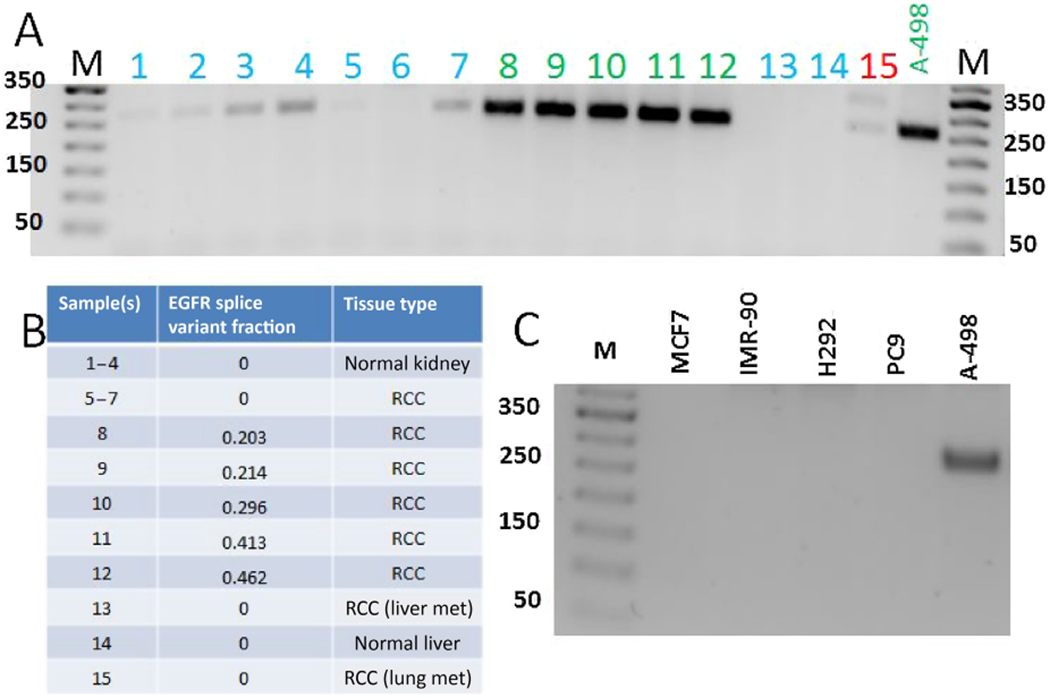

3.3. Validation of EGFR_pr20CTF

The presence of EGFR_pr20CTF in RCC was validated using primers to amplify the novel EGFR_pr20CTF splice isoform in tumor tissue and an A-498 human kidney cancer cell line using RT-PCR (Fig. 4). The variant was found to be absent in a panel of non-RCC cancer cell lines, which included human lung and breast cancer cell lines (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 –

Validation of EGFR_pr20CTF expression. Gene expression results of cDNA isolated from patient tissue samples and cell lines using primers amplifying the novel EGFR-20-CTFα splice isoform junction: (A) RT-PCR results from patient samples; (B) samples used, fraction EGFR_pr20CTFα splice isoform junction as determined by RNAseq, and tissue types represented in Fig. 4A; and (C) RT-PCR results from indicated cell lines. EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor; EGFR_pr20CTF = EGFR splice variant C-terminus fragment starting from novel exon 20; RCC = renal cell carcinoma; RT-PCR = reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction.

3.4. Clinical associations

We analyzed our institutional ccRCC cohort to identify associations between the presence of EGFR_pr20CTF and relevant clinical outcomes. The maxstat test was used to calculate cutoff values of 1.18% and 1.04% for OS and RFS, respectively, for total RNA reads demonstrating EGFR_pr20CTF. Associations with relevant clinical variables using these cutoff values are summarized in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4. KM curves for OS using this cutoff did not demonstrate a statistical difference (log-rank p = 0.247; Supplementary Fig. 4). KM curves for RFS using this value did not demonstrate a statistical difference, although there was a trend toward worse RFS for patients with high EGFR_pr20CTF variants (log-rank p = 0.053; Supplementary Fig. 4).

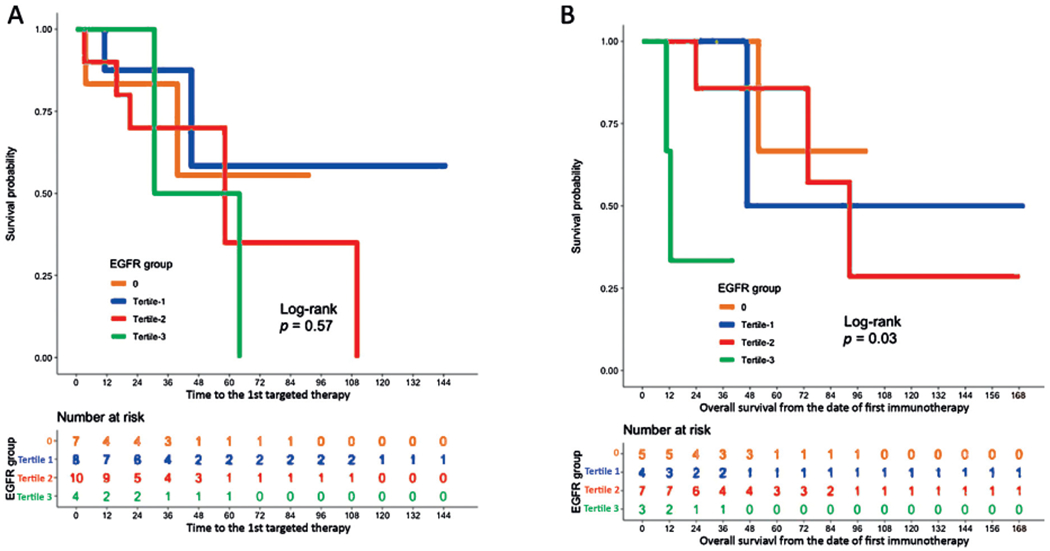

We then divided our cohort of patients with ccRCC into three tertiles based on the levels of EGFR_pr20CTF expression (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). We measured time to death (months) following first systemic therapy treatment, which included interleukin-2, atezolizumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, ipilimumab, cabozantinib, axitinib, pazopanib, sorafenib, sunitinib, levatinib, or everolimus. Patients with the highest expression of the EGFR_pr20CTFsplice variant had significantly lower survival at 48 mo following immunotherapy regimens compared with patients with the lowest expression of EGFR_pr20CTF (p = 0.036; Fig. 5). The average survival in patients with high EGFR_pr20CTF expression was <16 mo.

Fig. 5 –

Response to immunotherapy and targeted therapy stratified by EGFR level. KM curves of treatment response by tertiles of EGFR_pr20CTF expression. (A) Patients who received targeted therapy (n = 29) did not demonstrate a statistical difference in the TCC ccRCC cohort. (B) Patients who received immunotherapy (n = 19) demonstrated a statistical difference in overall survival from time on first immunotherapy (p = 0.03). ccRCC = clear cell renal cell carcinoma; EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor; TCC = Total Cancer Care Protocol.

4. Discussion

In our study, we identified and characterized the previously unrecognized alternative 5′ start site within intron 20 of EGFR, which gives rise to aberrant splice variants in RCC. These variants were found to be among the most frequent molecular alterations in ccRCC. At least one read demonstrating EGFR_pr20CTF was identified in 76.1% (n = 67/88) and 56.7% (n = 279/492) of tumors in our institutional RCC and the TCGA KIRC cohorts, respectively. EGFR_pr20CTF alterations in our ccRCC and KIRC cohorts were more common than many of the well-described somatic alterations seen in ccRCC, including PBRM1, SETD2, KDM5C, and even VHL [10,15].

These splice variants were highly specific to RCC. Although traces of EGFR_pr20CTF were found in non-ccRCC tumors, levels were much lower than what were seen in ccRCC and relatively infrequent. The presence of EGFR_pr20CTF was seen in a few normal adjacent tissues in the TCGA cohort analysis and in our RT-PCR studies. This is an interesting finding and should be further evaluated, but it could be explained by tumor contamination. These infrequent examples occurred at much lower levels and were primarily among the ccRCC samples. Finding of EGFR_pr20CTF in other solid tumors was extremely rare.

We observed that EGFR_pr20CTF splice forms do not include 5′ splicing events, which suggests a novel transcription initiation site within intron 20. In addition, a methionine in exon 21 indicates that this EGFR_pr20CTF is the beginning of a novel transcript from which a protein product could arise. This isoform would contain the 386 C-terminal amino acids, including some from the kinase domain. Knowledge of novel isoforms could allow for the development of screening tests (blood and urine) to yield biomarkers of disease or the development of targeted agents specific to this product (small molecule inhibitors, CAR T, and antibodies). Previous studies have also proposed the actions of EGFR and its downstream effects as a possible mechanism of TKI resistance [16], and the role these variants may play is an intriguing research question.

Several prior studies have demonstrated an upregulation of EGFR expression in RCC [5] and have linked it with poor clinical outcomes [4]. In our study, we saw a higher frequency of EGFR_pr20CTF in the ccRCC TCC tumors than in the KIRC dataset. This could be due to the differences in the patient population, as evidenced by the percentage of patients with stage pT3/T4 tumors in each cohort (TCC ccRCC = 72.7% [n = 64/88]; KIRC = 35.8% [n = 193/420]). Furthermore, we included specimens from metastatic tumors in our cohort, which could explain the enrichment of EGFR_pr20CTF that was seen in our population; 90% (9/10) of metastatic tissue samples demonstrated EGFR_pr20CTF. The differences would also seem to suggest that the development of these EGFR variants is a subclonal event in the evolution of the tumors to a more aggressive clinical phenotype.

Several prior clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate EGFR-targeted agents in the treatment of mRCC [17,18]. The premise for these trials was that EGFR overexpression was likely due to kinase-dependent EGFR activation. Other studies have looked at the possible role of kinase-independent EGFR activities in the tumorigenesis of RCC and other cancers. Increased cell death was reported in a study by Katreddy et al [19], which examined the use of EGFR antibodies (not kinase dependent) and EGFR-targeted agents (kinase dependent) in prostate cancer. Similar reports propose a possible therapeutic targeting of EGFR and associated proteins as a therapeutic strategy. To the best of our knowledge, this strategy has yet to be explored in relation to RCC [20].

Notably, many studies involving EGFR in RCC were not conducted in the age of immunotherapy. Our study is the first to demonstrate an association between EGFR and patient response to immunotherapy in RCC. Currently, first-line options for RCC include nivolumab plus ipilimumab, pembrolizumab plus axitinib, or avelumab plus axitinib, each of which has demonstrated improved outcomes versus sunitinib [21–23]. As such, whether these variants can serve as a biomarker for response to immunotherapy is yet to be determined.

Additionally, we have yet to determine whether a protein product that retains wild-type EGFR functionality is expressed. Similarly, it remains unknown whether these EGFR variants are functional and drive the tumor phenotype through downstream EGFR signaling, or whether they are a marker for additional splicing dysregulation within the tumor. Initial definitive information on the role of these variants in immune modulation remains to be determined. We hypothesize that cancers with increased transcriptional plasticity (including splicing and alternative transcription start sites) may be more readily able to shed epitopes and avoid immune recognition without having to sacrifice gene function. Specific examples of this have been seen as a mechanism for CAR T resistance [24].

Our study includes several limitations including its retrospective nature. Other limitations include those inherent to studies that use single-tumor sites, given intra- and intertumor heterogeneity at the molecular level in RCC. Second, there is currently no objective threshold at which to gauge the impact of splice variants in regard to their possible functional or clinical impact. Unfortunately, given our small cohort size and the heterogeneity of treatments, we were unable to look for treatment-specific associations with tumors expressing these variants. Finally, the clinical or biological impacts at specific cutoff values have not been elucidated thus far and may be different from those used in our analyses.

5. Conclusions

We identified and validated the presence of a novel aberrant RNA splice product (EGFR_pr20CTF) as a relatively frequent and specific molecular alteration in ccRCC. In an institutional cohort, this variant appeared to be enriched in patients with more advanced or metastatic disease, and in those who experienced a poor response to immunotherapy. These findings may have implications in the development of advances in screening and therapeutic exploitation strategies for this patient population. Moreover, our results warrant further investigation into whether this variant may be a biomarker for response to immunotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank Paul Fletcher (Moffitt Cancer Center) for his editorial assistance. He was not compensated beyond his regular salary. We thank the many patients who so graciously provided data and tissue to TCC for this study. The whole-exome and RNA-sequencing data included in this work was obtained through the Oncology Research Information Exchange Network (ORIEN) Avatar Project initiated under the Total Cancer Care (TCC) protocol at the Moffitt Cancer Center. Our study also received valuable assistance from the Tissue, Collaborative Data Services and Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Core Facilities at H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, an NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center, supported under NIH grantP30-CA76292.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: This work was supported in part by the Urology Care Foundation Research Scholar Award Program and Society for Urologic Oncology (Brandon J. Manley). Additionally, this work was supported in part by an Alpha Omega Alpha Carolyn L. Kuckein Student Research Fellowship (Saif Zaman). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the American Urological Association (AUA) or the Urology Care Foundation. This study leveraged the Total Cancer Care (TCC) Protocol at Moffitt Cancer Center, which was enabled, in part, by the generous support of the DeBartolo Family.

Financial disclosures: Ali Hajiran certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2019.12.001.

References

- [1].Furgason JM, Li W, Milholland B, et al. Whole genome sequencing of glioblastoma multiforme identifies multiple structural variations involved in EGFR activation. Mutagenesis 2014;29:341–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Guo P, Pu T, Chen S, et al. Breast cancers with EGFR and HER2 co-amplification favor distant metastasis and poor clinical outcome. Oncol Lett 2017;14:6562–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wu YL, Cheng Y, Zhou X, et al. Dacomitinib versus gefitinib as first-line treatment for patients with EGFR-mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (ARCHER 1050): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1454–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dordevic G, Matusan Ilijas K, Hadzisejdic I, Maricic A, Grahovac B, Jonjic N. EGFR protein overexpression correlates with chromosome 7 polysomy and poor prognostic parameters in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Biomed Sci 2012;19:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sakaeda T, Okamura N, Gotoh A, et al. EGFR mRNA is upregulated, but somatic mutations of the gene are hardly found in renal cell carcinoma in Japanese patients. Pharm Res 2005;22:1757–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science 2004;304:1497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hainsworth JD, Sosman JA, Spigel DR, Edwards DL,Baughman C, Greco A. Treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma with a combination of bevacizumab and erlotinib. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:7889–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gordon MS, Hussey M, Nagle RB, et al. Phase II study of erlotinib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic papillary histology renal cell cancer: SWOG S0317. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5788–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Choueiri TK, Motzer RJ. Systemic therapy for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2017;376:354–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Manley BJ, Zabor EC, Casuscelli J, et al. Integration of recurrent somatic mutations with clinical outcomes: a pooled analysis of 1049 patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol Focus 2017;3:421–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Davy G, Rousselin A, Goardon N, et al. Detecting splicing patterns in genes involved in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Eur J Hum Genet 2017;25:1147–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chen K, Xiao H, Zeng J, et al. Alternative splicing of EZH2 pre-mRNA by SF3B3 contributes to the tumorigenic potential of renal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:3428–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Fenstermacher DA, Wenham RM, Rollison DE, Dalton WS. Implementing personalized medicine in a cancer center. Cancer J 2011;17:528–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hothorn T, Lausen B. On the exact distribution of maximally selected rank statistics. Comput Stat Data Anal 2003;43:121–37. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hakimi AA, Pham CG, Hsieh JJ. A clear picture of renal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet 2013;45:849–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mizumoto A, Yamamoto K, Nakayama Y, et al. Induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition via activation of epidermal growth factor receptor contributes to sunitinib resistance in human renal cell carcinoma cell lines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2015;355:152–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dawson NA, Guo C, Zak R, et al. A phase II trial of gefitinib (Iressa, ZD1839) in stage IV and recurrent renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:7812–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ravaud A, Hawkins R, Gardner JP, et al. Lapatinib versus hormone therapy in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: a random-ized phase III clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2285–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Katreddy RR, Bollu LR, Su F, et al. Targeted reduction of the EGFR protein, but not inhibition of its kinase activity, induces mitophagy and death of cancer cells through activation of mTORC2 and Akt. Oncogenesis 2018;7:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ren J, Bollu LR, Su F, et al. EGFR-SGLT1 interaction does not respond to EGFR modulators, but inhibition of SGLT1 sensitizes prostate cancer cells to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Prostate 2013;73:1453–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov 2012;2:401–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rini BI, Plimack ER, Stus V, et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Motzer RJ, Penkov K, Haanen J, et al. Avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sotillo E, Barrett DM, Black KL, et al. Convergence of acquired mutations and alternative splicing of CD19 enables resistance to CART-19 immunotherapy. Cancer Discov 2015;5:1282–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.