Abstract

Purpose:

Few studies have examined the role of radiation therapy in advanced penile squamous cell carcinoma. We sought to evaluate the association of adjuvant pelvic radiation with survival and recurrence for patients with penile cancer and positive pelvic lymph nodes (PLNs) after lymph node dissection.

Materials and methods:

Data were collected retrospectively across 4 international centers of patients with penile squamous cell carcinoma undergoing lymph node dissections from 1980 to 2013. Further, 92 patients with available adjuvant pelvic radiation status and positive PLNs were analyzed. Disease-specific survival (DSS) and recurrence were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and multivariable Cox proportional hazards model.

Results:

43% (n = 40) of patients received adjuvant pelvic radiation after a positive PLN dissection. Median follow-up was 9.3 months (interquartile range: 5.2–19.8). Patients receiving adjuvant pelvic radiation had a median DSS of 14.4 months vs. 8 months in the nonradiation group, respectively (p = 0.023). Patients without adjuvant pelvic radiation were associated with worse overall survival (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.7; 95% CI: 1.01–2.92; P = 0.04) and DSS (HR = 1.9; 95% CI: 1.09–3.36; P = 0.02) on multivariable analysis. Median time to recurrence was 7.7 months vs. 5.3 months in the radiation and nonradiation arm, respectively (p = 0.042). Patients without adjuvant pelvic radiation was also independently associated with higher overall recurrence on multivariable analysis (HR = 1.8; 95% CI: 1.06–3.12; p = 0.03).

Conclusions:

Adjuvant pelvic radiation is associated with improved survival and decreased recurrence in this population of patients with penile cancer with positive PLNs.

Keywords: Adjuvant radiation, Lymph node dissection, Penile cancer, Recurrence, Survival

1. Introduction

Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis is a rare urologic malignancy that represents only 0.4% to 0.6% of all malignant neoplasms in the United States and Europe [1]. Prognosis is largely stage dependent with pelvic lymph node (PLN) involvement and extranodal extension (ENE) associated with poor overall survival (OS) [2,3]. Various factors have been shown to predict PLN metastasis including inguinal ENE, extent of inguinal lymph node metastasis, and inguinal lymph node diameter [4].

Advanced stages have posed many challenges in penile cancer management owing to a paucity of literature secondary to its rarity. As a result, treatment recommendations have not been uniform in nodal disease. Management options available include a multimodal approach with surgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiation. In high-risk patients, such as the presence of PLN metastasis and ENE, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends considering adjuvant external beam radiation therapy or chemoradiotherapy [5]. The European Association of Urology (EAU), on the contrary, recommends adjuvant chemotherapy for pN2 and pN3 disease.

The role of radiation therapy in penile cancer has also not been well defined owing to sparse published data and mixed results [6–9]. Most of these studies report outcomes related to radiation of inguinal regions in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings. Although some reports present a subgroup analysis of pelvic radiation showing no benefit, the cohorts are underpowered with conclusions that are strongly suggestive but not definitive [6,7]. Despite the lack of positive evidence supporting pelvic radiation in penile cancer, it remains a reasonable option to consider owing to the extrapolated efficacy of radiation in other locally advanced or node-positive squamous cell carcinomas such as vulvar and head-and-neck malignancies [10,11]. Therefore, we investigated the treatment results of adjuvant pelvic radiation in patients with known positive PLN. Using a large, multi-institutional, and international cohort, we sought to evaluate the association of adjuvant pelvic radiation with OS, disease-specific survival (DSS), and recurrence.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients and demographics

We performed a retrospective review of 92 patients who underwent inguinal and PLN dissection for locally advanced penile cancer. All patients had adjuvant pelvic radiation status recorded. This cohort was obtained across 4 international tertiary referral centers from 1980 to 2013 following institutional review board approval at all participating institutions. All patients were found to have positive nodes after PLN dissection (pN3) and were not known to be metastatic at the time of dissection. Disease characteristics recorded included primary penile tumor stage (pT), presence of inguinal and pelvic ENE, and number of positive PLNs. Recurrence was defined as clinical evidence of disease on physical examination or imaging after PLN dissection. The location for disease recurrence were recorded as local (penile resection bed), regional (inguinal or pelvic), or distant (lungs, bones, peritoneum, or liver). If disease recurrence occurred in multiple locations, the worse site was recorded. Postoperative chemotherapy was defined as chemotherapy given in the adjuvant setting. Preoperative chemotherapy was defined as chemotherapy given in the neoadjuvant setting. Chemotherapy regimens were either platinum based (cisplatin and 5-FU ± docetaxel; cisplatin, bleomycin, and methotrexate; cisplatin, paclitaxel, and ifosfamide) or with vincristine, bleomycin, and methotrexate. Follow-up for overall and DSS was defined as time of PLN dissection to the date of last contact or date of death. Follow-up for recurrence was defined as time of PLN dissection to date of last contact or date of recurrence. Complete follow-up data for survival was available for all patients. Complete follow-up data for recurrence was available for 91 (99%) patients in the cohort.

2.2. Description of PLN dissection

Before 2008, indications for undergoing PLN dissection were not uniform across centers owing to the lack of available standardized guidelines. However, during the past 5 years of the study, the decision to perform a unilateral or bilateral PLN dissection was based on NCCN and EAU guidelines, which recommend proceeding with a PLN dissection for inguinal ENE or 2 or more positive inguinal lymph nodes [5,12]. Surgical technique was similar across the 4 centers, which included dissection of obturator, internal iliac, and external iliac lymph nodes.

2.3. Histopathological examination

Pathological examination of all PLN was performed at each respective center and classified according to the TNM system of the American Joint Committee on Cancer [13]. Cases before 2010 were reclassified according to the 2010 TNM system. ENE was defined as the extension of tumor through the lymph node capsule into the perinodal fibrousadipose tissue.

2.4. Indications for adjuvant radiation therapy

Radiation was provided at the discretion of the radiation oncologist at each respective center. All pelvic radiation was given in the adjuvant setting without evidence of recurrence at the time of treatment. In most instances, adjuvant pelvic radiation therapy was offered by the treating physician based on the presence of high-risk features for locoregional recurrence such as positive surgical margins or pelvic ENE. The pelvic radiation field included bilateral iliac, presacral, and obturator regions. However, indications for adjuvant pelvic radiation were not standardized given the absence of evidence-based guidelines and were based largely on the respective institutional policies. Adjuvant therapy was given within 1 to 4 months after PLN dissection in 38 patients. Two patients received adjuvant therapy over 4 months after PLN dissection, but he did not recur. Delivered dose was 50 Gy in 25 daily fractions in 27 (68%) patients. Four (10%) patients received a delivered dose of less than 40 Gy in unknown daily fractions whereas 5 (13%) received a delivered dose of more than 50 Gy in unknown daily fractions. Four (10%) patients had unrecorded radiation doses.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were described with median and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Categorical variables were reported as relative frequencies and percentages. Associations among categorical variables were determined using the chi-square test. Associations between adjuvant pelvic radiation and quantitative variables were determined using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Kaplan-Meier curves are provided for all 3 outcomes of interest and compared with the log-rank test. Multivariable analyses were conducted using Cox proportional hazards regression on each outcome. Variables in the multivariable model included pelvic ENE, receipt of chemotherapy, grade of differentiation, and year of PLN dissection. Institution and number of positive pelvic nodes were included in earlier adjusted models and did not show any significance. These variables were removed in the final analyses and are not shown. Similar to univariable analyses, hazard ratios (HRs) and P-values were produced, indicating the effect of radiation treatment in the individual models. In all cases, P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 9.4.

3. Results

A total of 92 patients had positive PLN after PLN dissection. The median follow-up time was 9.3 months (IQR: 5.2–19.8). The median age of our cohort was 65.3 years (IQR: 53–70) (Table 1). Most patients presented with pT2 disease or greater (77.2%) and grade 2 or higher (72.8%). The median number of positive PLN was 2 (IQR: 1–3), and the median PLN removed was 10 (IQR: 7–15). Furthermore, 39 (42.4%) patients had pelvic ENE. Prior inguinal lymph node positivity was present in 83 (90%) patients whereas 10 (11%) patients had unknown inguinal lymph node status. Adjuvant pelvic radiation was performed in 40 patients (43.5%). There were no differences between the radiation and nonradiation group with respect to age, stage, grade, median positive PLN, median PLN removed, ENE, or use of chemotherapy (P > 0.05 for all values). Recurrence was found in 69 (75%) patients: at regional sites in 33.7% (31 patients), and at distant sites in 27.2% (25 patients); 6 patients (6.5%) recurred locally. There were 63 (89%) deaths from disease and 8 (11%) deaths from other causes.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Entire population | No XRT | XRT | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 92 | 52 (56.5) | 40 (43.5) | 0.37 |

| Age | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 65.3 (53.6–70.6) | 64.2 (51.6–70.5) | 65.4 (55.7–70.9) | 0.83 |

| Stagea | ||||

| pT1 | 13 (14.1) | 6 (11.5) | 7 (17.5) | 0.17 |

| pT2 | 57 (62) | 29 (55.8) | 28 (70) | |

| pT3 | 13 (14.1) | 9 (17.3) | 4 (10) | |

| pT4 | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | |

| pTx | 8 (8.7) | 7 (13.5) | 1 (2.5) | |

| Gradea | ||||

| 1 | 19 (20.7) | 12 (23.1) | 7 (17.5) | 0.87 |

| 2 | 36 (39.1) | 20 (38.5) | 16 (40) | |

| 3/4 | 31 (33.7) | 16 (30.8) | 15 (37.5) | |

| Unknown | 3 (3.3) | 2 (3.8) | 1 (2.5) | |

| Pelvic LN removed | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 10 (7-15) | 10 (5-13.2) | 11 (7-17) | 0.16 |

| Positive pelvic LN | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.61 |

| Extranodal extension | ||||

| No | 42 (45.7) | 20 (38.5) | 22 (55) | 0.17 |

| Yes | 39 (42.4) | 25 (48.1) | 14 (35) | |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| None | 65 (71) | 35 (67) | 30 (75) | 0.59 |

| Pre-op | 14 (15) | 8 (15) | 6 (15) | |

| Post-op | 13 (14) | 9 (17) | 4 (10) | |

| Recurrence | ||||

| No | 22 (23.9) | 10 (19.2) | 12 (30) | 0.32 |

| Yes | 69 (75) | 41 (78.8) | 28 (70) | |

| Recurrence site | ||||

| Local | 6 (6.5) | 4 (7.7) | 2 (5) | 0.81 |

| Regional | 31 (33.7) | 18 (34.6) | 13 (32.5) | |

| Distant | 25 (27.2) | 13 (25) | 12 (30) | |

| Survival | ||||

| Died of disease | 63 (89) | 39 (95) | 24 (80) | 0.14 |

| Other causes | 8 (11) | 2(5) | 6 (20) |

LN = lymph nodes; XRT = adjuvant pelvic radiation.

Fisher’s exact test.

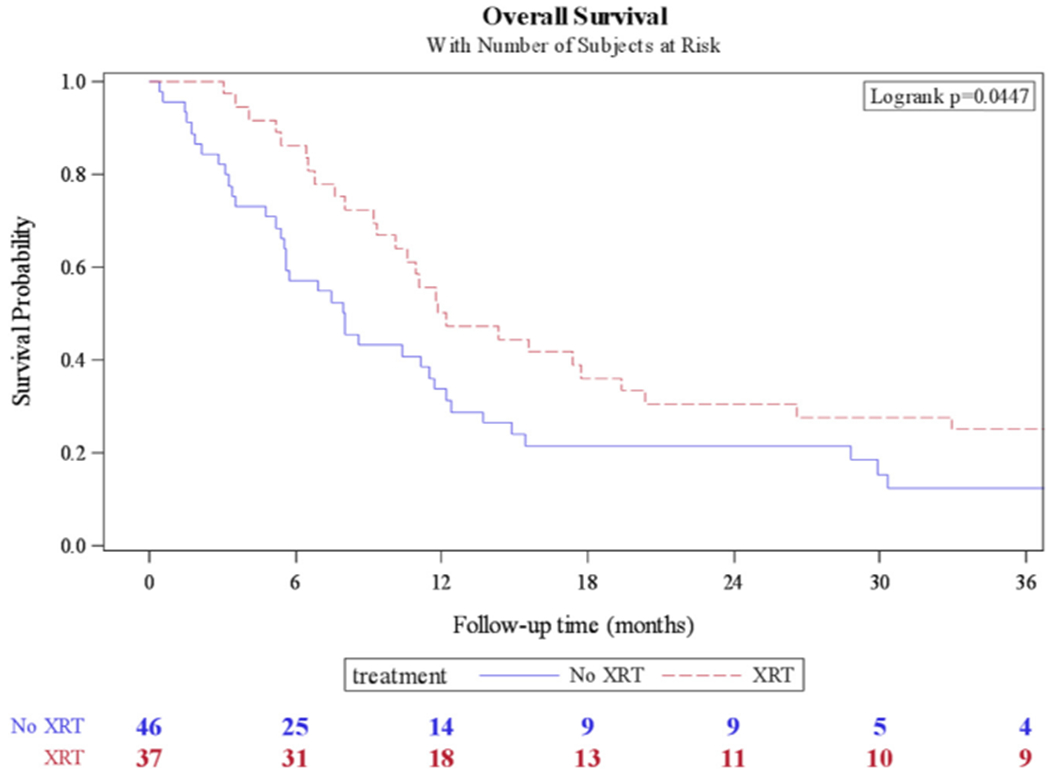

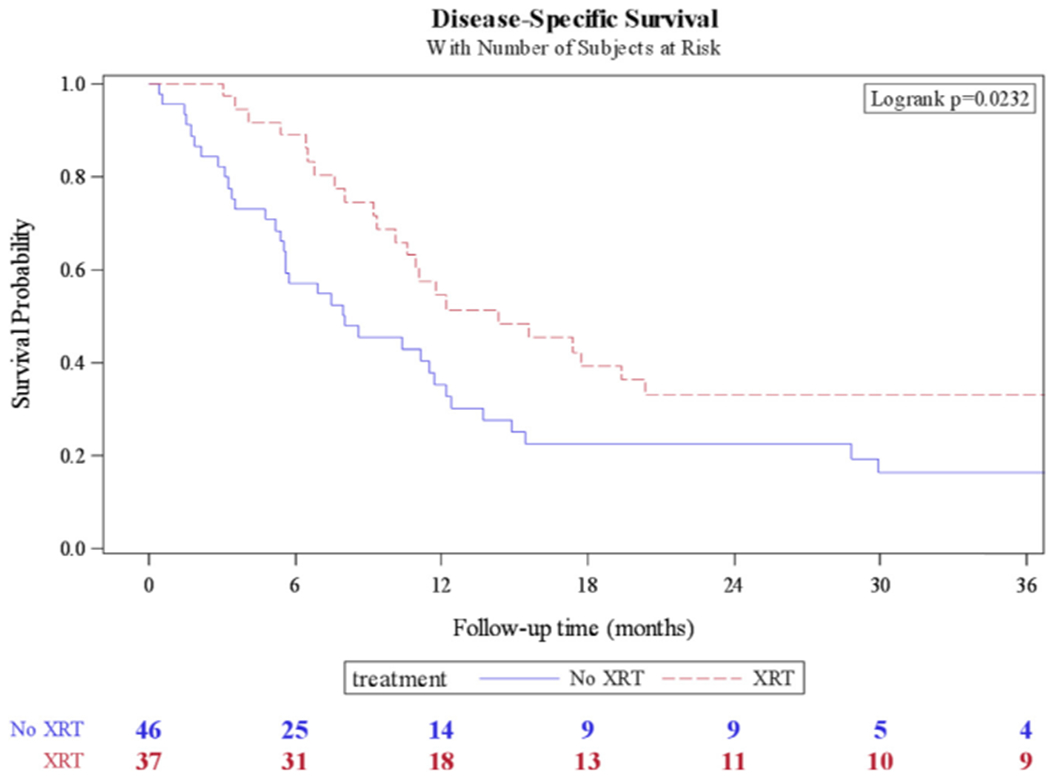

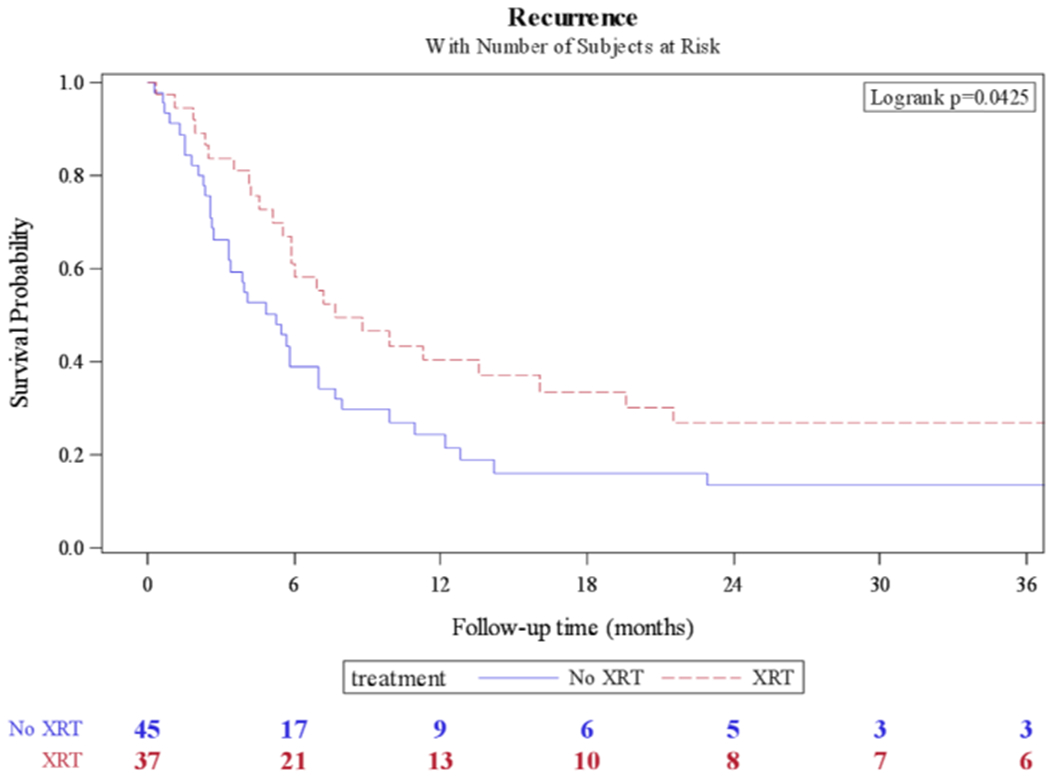

The median OS for adjuvant pelvic radiation was 12.2 months compared to 8 months for nonradiated patients (P = 0.044) (Fig. 1). The median DSS for adjuvant pelvic radiation was 14.4 months compared to 8 months for nonradiated patients (P = 0.023) (Fig. 2); 71 deaths (79.8%) occurred during available follow-up. The median time to recurrence was 5.9 months (IQR: 2.7–16). The median time to recurrence for adjuvant radiation was 7.7 months compared to 5.3 months for nonradiated patients (P = 0.042) (Fig. 3); 69 patients (75%) had a recurrence during available follow-up.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve for overall survival in patients who received adjuvant pelvic radiation (XRT) vs. no radiation.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve for disease-specific survival in patients who received adjuvant pelvic radiation (XRT) vs. no radiation.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve for recurrence-free survival in patients who received adjuvant pelvic radiation (XRT) vs. no radiation.

On multivariable analysis, patients who did not undergo adjuvant radiation were independently associated with poor OS (HR = 1.7; 95% CI: 1.01–2.92; P = 0.04) (Table 2) and poor DSS (HR = 1.9; 95% CI: 1.09–3.36; P = 0.02) (Table 2). Patients with pelvic ENE were also associated with poor OS (HR = 2.3; 95% CI: 1.37–3.99; P ≤ 0.01) and DSS (HR = 2.0; 95% CI: 1.16–3.58) P = 0.01) on multivariable analysis (Table 2). Inclusion of institution as a variable in the multivariable model was not significant and did not result in any change in outcome (results not shown). Those without adjuvant radiation were also independently associated with an increased risk of recurrence (HR = 1.8; 95% CI: 1.06–3.12; P = 0.03), whereas patients with pelvic ENE were associated with an increased risk of recurrence rate (HR = 1.9; 95% CI: 1.12–3.24; P = 0.02) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Multivariable analysis for disease-specific and overall survival

| Variable | Disease-specific survival |

Overall survival |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| A-XRT | ||||||

| Yes | Referent | Referent | ||||

| No | 1.9 | 1.09–3.36 | 0.02 | 1.7 | 1.01–2.92 | 0.04 |

| Pelvic ENE | ||||||

| No | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Yes | 2.0 | 1.16–3.58 | 0.01 | 2.3 | 1.37–3.99 | <0.01 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| None | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Pre-op | 1.0 | 0.49–2.06 | 0.99 | 1.1 | 0.53–2.13 | 0.85 |

| post-op | 1.0 | 0.39–2.72 | 0.94 | 1.0 | 0.38–2.62 | 0.99 |

| Grade | ||||||

| 1/2 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| 3/4 | 1.2 | 0.69–2.17 | 0.49 | 1.0 | 0.59–1.79 | 0.92 |

| Treatment year | 1.0 | 0.99–1.07 | 0.13 | 1.0 | 0.99–1.06 | 0.14 |

Bold indicates significance at P < 0.05. A-XRT = adjuvant pelvic radiation therapy; HR = hazard ratio; LN = lymph nodes.

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis for recurrence

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| A-XRT | |||

| Yes | Referent | ||

| No | 1.8 | 1.06–3.12 | 0.03 |

| Pelvic ENE | |||

| No | Referent | ||

| Yes | 1.9 | 1.12–3.24 | 0.02 |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| None | Referent | ||

| Pre-op | 0.8 | 0.45–1.74 | 0.72 |

| Post-op | 0.8 | 0.29–2.35 | 0.73 |

| Grade | |||

| 1/2 | Referent | ||

| 3/4 | 1.4 | 0.78–2.42 | 0.27 |

| Treatment year | 1.0 | 0.98–1.06 | 0.19 |

Bold indicates significance at P < 0.05. A-XRT = adjuvant pelvic radiation therapy; LN = lymph nodes.

4. Discussion

In our study, adjuvant pelvic radiation was associated with a 4-month improvement in median OS and a 6-month improvement in median DSS in patients with positive PLN after inguinal and PLN dissection. A 2.4-month improvement in median recurrence was also associated with adjuvant pelvic radiation. These associations remain consistent after controlling for potential confounders in a multivariable model. As expected, pelvic ENE was also independently associated with poor prognosis in OS and recurrence in our adjusted models. To our knowledge, this is the largest clinical outcome study investigating the association of adjuvant pelvic radiation in the setting of positive PLN in penile carcinoma.

Evidence driving management of nodal metastasis in penile cancer has not been robust given lack of randomized trials. Chemotherapy has been a recommended treatment of nodal involvement per EAU guidelines [12]. This is based on studies of combination drug therapies containing cisplatin or taxane [14,15]. For patients with positive pelvic node disease, neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been advocated based on positive studies extrapolated from patients with fixed, unresectable, and bulking inguinal lymph nodes [16,17]. In addition, a recent report investigated a multicenter cohort of 84 patients in pelvic node-positive disease and found adjuvant chemotherapy to be associated with improved OS after adjusting for confounders (HR = 0.4; 95% CI: 0.19–0.87; P = 0.021) [18]. This study was based on a cohort of chemotherapy-naïve patients.

There are few studies reporting the role of inguinal and pelvic radiation therapy for advanced penile carcinoma. An early prospective nonrandomized study showed superior results for surgery when comparing bilateral inguinal node dissection and prophylactic radiation to the groin in a cohort of 64 patients with clinically negative nodes [19]. A larger series of 156 patients showed that radiation benefit may be in the preoperative and palliative setting [6]. This study reported only 3% of patients developing recurrence and 8% of patients with ENE. It is noted that these results were compared to a separate contemporaneous cohort of patients only undergoing surgery. Palliation of symptoms was noted in 56% of patients in this study. Pelvic or para-aortic radiation or both was found to be ineffective in this cohort for metastatic PLNs. However, this subgroup is underpowered with only 22 patients.

Few attempts have been made to investigate adjuvant radiation in node-positive patients. Graafland et al. [7] reviewed recurrences in a cohort of 161 patients with positive lymph nodes. In this study, 11/26 recurrences received adjuvant radiation, and 11 other patients received radiation after developing recurrence [7]. However, oncologic outcomes were not stratified by radiation status. Franks et al. investigated outcomes of a cohort of 23 patients who received radiation therapy to inguinal/PLNs either as adjuvant treatment, high grade palliation for inoperable fixed nodes, or extensive local tumor involvement [9]. As expected, adjuvant radiation therapy was found to have better OS compared to palliative radiation therapy given dramatic differences in disease staging (P < 0.001). Finally, a Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results analysis was performed on 2,458 patients with penile carcinoma [8], and 7% of this cohort received adjuvant radiation therapy and was found with no benefit in cancer-specific survival in a multivariable analysis (HR = 1.09; 95% CI: 0.74–1.61; P = 0.65). However, they were unable to control for other confounders such as ENE, location of radiation treatment, and chemotherapy use due to limitations of the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database.

Although there are limited data regarding radiation therapy for nodal disease in penile cancer, consideration for adjuvant treatment remain reasonable given its efficacy in other squamous cell carcinomas. After radical vulvectomy and positive inguinal lymph node dissection, adjuvant radiation was reported to reduce disease-specific deaths in a randomized controlled trial of 114 patients compared to pelvic node dissection (HR = 0.49; 95% CI: 0.28–0.87; P = 0.015) [10]. In addition, adjuvant chemoradiation may also be of benefit extrapolating results of advanced disease from other squamous cell carcinomas. A multicenter randomized trial reported chemoradiation therapy in the adjuvant setting for advanced head-and-neck cancer to be more efficacious in progression-free survival compared to radiation alone (HR = 0.75; 95% CI: 0.56–0.99; P = 0.04) [11].

As a retrospective study, this study has limitations inherent to its nature including lack of controls for variables, small sample size, and short follow-up. No treatment protocol was established beforehand for this cohort as patients were managed across 4 centers spanning 30 years. Therefore, we included treatment year in the multivariable analysis for survival and recurrence to control for variability in treatment within the timeframe. Furthermore, patient characteristics such as performance status and comorbidities were unavailable for the analysis. Although these may be confounders, the majority of deaths was due to disease and may not have changed the outcome. Data regarding associated infections such as human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus, and human papillomavirus were also unavailable for analysis. In addition, the delivered radiation dose was not consistently recorded across all centers. However, most (68%) patients received radiation dose of 50 Gy in 25 daily fractions. Given the multi-institutional collaboration, there was also a lack of central pathologic review for all specimens. The decision to proceed with adjuvant pelvic radiation was taken on a case-by-case basis per clinician discretion and per respective institutional policies. However, this resulted in comparable characteristics between the radiation and nonradiation group. In addition, 46 (50%) of these patients also received some form of chemotherapy in the preoperative and postoperative setting. This was controlled for in a multivariable analysis for OS, DSS, and recurrence.

Although a previous study of a similar cohort found adjuvant chemotherapy to be associated with improved survival, our study was unable to demonstrate this benefit [18]. This is likely due to an underpowered postoperative chemotherapy group after implementing our inclusion criteria. It is also noted that we were unable to evaluate inguinal radiation as data were only collected for pN3 patients. This may be significant as it is unknown whether our findings apply to inguinal lymph node positivity (pN1–2). Furthermore, toxicities and complications due to radiation therapy were unavailable for the analysis and could not be reported. Lastly, our results can only be applied to patients who are acceptable surgical candidates, as the entire cohort underwent an inguinal and PLN dissection for curative intent. Further study with a prospective design and longer follow-up is needed to validate these findings.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that pelvic adjuvant radiation for pN3 disease is associated with improved survival and decreased recurrence in penile carcinoma. This is the first study to show this relationship in this select, high-risk group. Although pelvic radiation may continue to be considered in the adjuvant setting, it will require further evaluation in clinical trials.

References

- [1].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Liu JY, Li YH, Zhang ZL, et al. The risk factors for the presence of pelvic lymph node metastasis in penile squamous cell carcinoma patients with inguinal lymph node dissection. World J Urol 2013; 31:1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Graafland NM, van Boven HH, van Werkhoven E, et al. Prognostic significance of extranodal extension in patients with pathological node positive penile carcinoma. J Urol 2010;184:1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lughezzani G, Catanzaro M, Torelli T, et al. The relationship between characteristics of inguinal lymph nodes and pelvic lymph node involvement in penile squamous cell carcinoma: a single institution experience. J Urol 2014;191:977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Clark PE, Spiess PE, Agarwal N, et al. Penile cancer: clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2013;11:594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ravi R, Chaturvedi HK, Sastry DV. Role of radiation therapy in the treatment of carcinoma of the penis. Br J Urol 1994;74:646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Graafland NM, Moonen LM, van Boven HH, et al. Inguinal recurrence following therapeutic lymphadenectomy for node positive penile carcinoma: outcome and implications for management. J Urol 2011;185:888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Burt LM, Shrieve DC, Tward JD. Stage presentation, care patterns, and treatment outcomes for squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014;88:94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Franks KN, Kancherla K, Sethugavalar B, et al. Radiotherapy for node positive penile cancer: experience of the Leeds teaching hospitals. J Urol 2011;186:524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kunos C, Simpkins F, Gibbons H, et al. Radiation therapy compared with pelvic node resection for node-positive vulvar cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bernier J, Domenge C, Ozsahin M, et al. Postoperative irradiation with or without concomitant chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hakenberg OW, Comperat EM, Minhas S, et al. EAU guidelines on penile cancer: 2014 update. Eur Urol 2015;67:142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pizzocaro G, Piva L. Adjuvant and neoadjuvant vincristine, bleomycin, and methotrexate for inguinal metastases from squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. Acta Oncol 1988;27:823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Noronha V, Patil V, Ostwal V, et al. Role of paclitaxel and platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy in high-risk penile cancer. Urol Ann 2012;4:150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bermejo C, Busby JE, Spiess PE, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by aggressive surgical consolidation for metastatic penile squamous cell carcinoma. J Urol 2007;177:1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Leijte JA, Kerst JM, Bais E, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in advanced penile carcinoma. Eur Urol 2007;52:488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sharma P, Djajadiningrat R, Zargar-Shoshtari K, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy is associated with improved overall survival in pelvic node-positive penile cancer after lymph node dissection: a multi-institutional study. Urol Oncol 2015;33:496–e17.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kulkarni JN, Kamat MR. Prophylactic bilateral groin node dissection versus prophylactic radiotherapy and surveillance in patients with N0 and N1–2A carcinoma of the penis. Eur Urol 1994; 26:123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]