Abstract

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends that men who have sex with men (MSM) 26 years of age or younger be routinely vaccinated against HPV. For men outside of this risk-based population, the recommendation is routine vaccination until age 21. Thus, in order for this risk-based recommendation for MSM to be implemented, two distinct actions need to be completed during the clinical visit: (1) discuss recommendations for HPV vaccination with men and (2) assess sexual orientation to determine if a risk-based recommendation should be made. We assessed the degree to which physicians routinely discussed issues of sexual orientation and HPV vaccination with male patients 22–26 years old. We used data from a statewide representative sample of 770 primary care physicians practicing in Florida who were randomly selected from the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile. The analytic sample consisted of physicians who provided care to men 22–26 years old (N = 220). Response rate was 51%. Data collection took place in 2014 and analyses in 2016. Only 13.6% of physicians were routinely discussing both sexual orientation and HPV vaccination with male patients 22–26 years old, and approximately a quarter (24.5%) were not discussing either. Differences in these behaviors were found based on gender, Hispanic ethnicity, availability of HPV vaccine in clinic, HPV-related knowledge, and specialty. A minority of physicians in this sample reported engaging with these patients in ways that are mostly likely to result in recommendations consistent with current Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices guidelines.

Keywords: HPV vaccine policy, Men who have sex with men, Physician, Healthcare provider, Implementation science

Background

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends routine HPV vaccination for males and females 11–12 years of age [1]. The ACIP also calls for routine vaccination of females up through age 26 and 21 for males. From ages 22–26, the recommendation for males is permissive rather than routine; however, there are two risk-based recommendations for routine vaccination. It is recommended that (1) men who have sex with men (MSM) (inclusive of men who identify as gay or bisexual or who intend to have sex with men) and (2) immunocompromised men through age 26 (primarily men infected with HIV) be routinely vaccinated for HPV [1]. This policy creates a 5-year period for males between 22 and 26 years old for whom there is either a weak permissive recommendation or a strong routine recommendation depending on their sexual behavior or immunodeficiency.

These risk-based recommendations are needed to decrease HPV-related disease in MSM (e.g., anal cancer) [2]. Rates of anal cancer have increased in the USA [3] where approximately 90% of all anal cancers are caused by HPV infection [4] and MSM suffer substantial disparities in anal cancer rates [5]. The prevalence of high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia—the precursors to anal carcinoma—ranges from 13.7 to 35.4% in MSM, with higher prevalence in HIV-infected men [6]. The quadrivalent and nonavalent HPV vaccines are safe and effective methods of preventing these diseases [1, 7].

In general, MSM appear to be receptive to HPV vaccination [8, 9], particularly toward messages that emphasize the vaccine’s efficacy in preventing anal cancer [10]. Yet, despite the acceptability of this vaccine among MSM and the affirmative recommendation prioritizing routine vaccination of adult MSM up through age 26, vaccine uptake remains low. In a 2013 survey of a national sample of self-identified gay and bisexual men between the ages of 18 and 26, just 13% had initiated HPV vaccination [11]. This is a population of men that regularly utilize healthcare services [12], and at least among gay-identified men, may be more likely to have a medical home than their heterosexual peers [13]. Therefore, low uptake among this population is mostly likely a result of a failure of healthcare providers to educate patients about this vaccine. In the same national survey of gay and bisexual men previously described, 43% of the sample reported having had a routine medical checkup in the previous year, but only 11% had received a healthcare provider recommendation to get the HPV vaccine [11]. The extant behavioral literature strongly suggests that, if HPV vaccination is recommended to adult MSM by their healthcare provider, the majority will comply with that recommendation [8, 9, 11].

However, there are many unanswered questions regarding the implementation of these risk-based recommendations in clinical practice including the need for provider education. To implement these recommendations, two distinct actions need to be completed during the clinical visit: (1) discuss the recommendations for HPV vaccination with men ages 22–26 and (2) assess sexual orientation to determine if a risk-based recommendation should be made. It is unknown how likely physicians are to discuss both issues during preventive health visits.

As part of a larger study to identify physician recommendation of HPV vaccination for males in Florida [14], this substudy examined clinical practices that may act as barriers to the routine vaccination of MSM. Specifically, we assessed the degree to which physicians routinely discussed issues of sexual orientation and HPV vaccination with male patients 22–26 years old.

Methods

This study was a secondary analysis of data from a statewide representative sample of 770 primary care physicians practicing in family medicine or pediatrics who were randomly selected from the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile. The study was cross-sectional mailed questionnaire with a 51% response rate. Data collection took place in the summer of 2014. Participants provided written informed consent and all procedures were approved by the corresponding author’s institutional review board. The detailed methods are reported elsewhere [14].

The 38-item survey included sections on HPV-related knowledge, clinical practices, and physician demographics. The primary variables for the current analysis were two items indicating if a physician (1) usually presents HPV vaccine to male patients (does not discuss vs. presents as optional or routine) and (2) routinely discusses issues of sexual orientation (yes or no). We did not examine communication regarding HIV infection. The patient population was specified as males between the ages of 22 and 26 years for each item. Physician communication practices were grouped into four categories: Physicians who do not routinely discuss sexual orientation or HPV vaccination were labeled as low potential. An indeterminate label was applied to physicians who discuss either sexual orientation or HPV vaccination. Physicians who do routinely discuss sexual orientation and HPV vaccination were labeled as high potential.

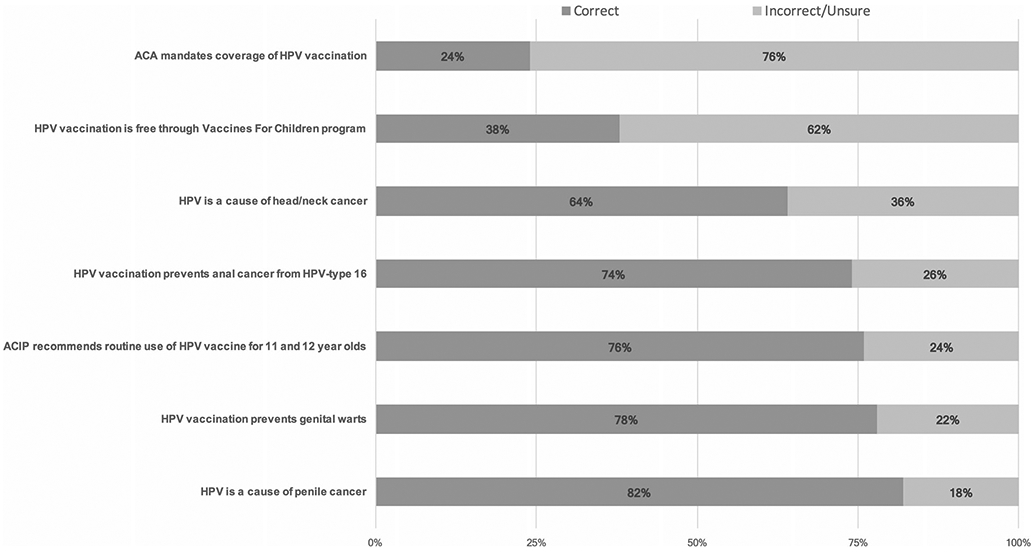

HPV knowledge was assessed by seven items regarding basic epidemiology of HPV and HPV vaccination, as well as ACIP recommendations (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Knowledge of HPV epidemiology, vaccine indications, and recommendations: data collected from physicians practicing in the state of Florida in 2014

Statistical Analysis

An exploratory analysis was conducted from an analytic sample consisting of physicians who provided care to men between the ages of 22 and 26 (N = 220). Listwise deletion was used to account for missing data that ranged from 0 to 6% for any given variable. Descriptive and bivariate analyses were used to characterize the study sample in terms of physician communication and associated characteristics. Crude odds ratios were calculated to contrast significant difference found across the categories of physician communication. SAS 9.3 was used for all analysis in 2016.

Results

Participants were mostly non-Hispanic (78.7%), white (71.6%), males (59.9%), and 50 years of age or older (50.2%). Most were in family medicine (80.6%) and worked in a private practice (61.4%) with a single specialty (62.5%). Their practices were in suburban (56%), urban (34%), or rural (10%) locations. About half of the practices administered HPV vaccine in office (51.8%).

Overall, physicians knew about HPV-related diseases in men but were less knowledgeable about vaccine mandates and programs. A majority were aware of the routine HPV vaccine recommendation for MSM (70.5%) (Fig. 1).

Only 13.6% of physicians routinely discussed both sexual orientation and HPV vaccination with male patients 22–26 years old (i.e., the “high potential” group), and approximately a quarter (24.5%) did not discuss either (Table 1). The majority (60.5%) routinely discussed either sexual orientation or HPV vaccination. Differences in these behaviors were found based on gender, Hispanic ethnicity, availability of HPV vaccine in clinic, HPV-related knowledge, and specialty.

Table 1.

Potential to provide appropriate HPV vaccine recommendations to males 22–26 years old by physician and practice characteristics, data collected from physicians practicing in the state of Florida in 2014

| Low potential | Indeterminate |

High potential | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No routine discussion of sexual orientationa and does not discuss HPV vaccineb N (%) |

No routine discussion of sexual orientationa but discusses HPV vaccinec N (%) |

Routine discussion of sexual orientationd but does not discuss HPV vaccineb N (%) |

Routine discussion of sexual orientationd and HPV vaccinationc N (%) |

p for χ2 test |

|

| Totals | 56 (24.5) | 39 (17.3) | 95 (43.2) | 30 (13.6) | |

| Gender | 0.02 | ||||

| Male | 34 (26.2) | 29 (22.3) | 47 (36.2) | 20 (15.4) | |

| Female | 20 (23.0) | 9 (10.3) | 48 (55.2) | 10 (11.5) | |

| Age | 0.45 | ||||

| 30–39 | 8 (25.0) | 5 (15.6) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (15.6) | |

| 40–49 | 12 (16.2) | 16 (21.6) | 36 (48.7) | 10 (13.5) | |

| 50+ | 33 (30.8) | 16 (15.0) | 43 (40.2) | 15 (14.0) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.05 | ||||

| Yes | 12 (26.1) | 7 (15.2) | 26 (56.5) | 1 (2.2) | |

| No | 43 (25.3) | 30 (17.7) | 69 (40.6) | 28 (16.5) | |

| Race | 0.31 | ||||

| White | 43 (28.5) | 26 (17.2) | 63 (41.7) | 19 (12.6) | |

| Non-white | 10 (16.7) | 10 (16.7) | 30 (50.0) | 10 (16.7) | |

| Specialty | 0.09e | ||||

| Pediatrics | 9 (37.5) | 5 (20.8) | 9 (37.5) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Family medicine | 43 (24.7) | 27 (15.5) | 81 (46.6) | 23 (13.2) | |

| Otherf | 4 (22.2) | 4 (22.2) | 4 (22.2) | 6 (33.3) | |

| Years in practice | 0.15 | ||||

| ≤10 | 12 (20.3) | 10 (17.0) | 30 (50.9) | 7 (11.9) | |

| 11–15 | 7 (19.4) | 12 (33.3) | 13 (36.1) | 4 (11.1) | |

| 16+ | 32 (29.1) | 15 (13.6) | 46 (41.8) | 17 (15.5) | |

| Location of practice | 0.14 | ||||

| Urban | 17 (25.0) | 7 (10.3) | 37 (54.4) | 7 (10.3) | |

| Suburban | 31 (26.5) | 26 (22.2) | 41 (35.0) | 19 (16.2) | |

| Rural | 5 (22.7) | 3 (13.6) | 12 (54.6) | 2 (9.1) | |

| Clinic administers vaccine to males | <0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 17 (16.2) | 33 (31.4) | 32 (30.5) | 23 (21.9) | |

| No | 39 (34.5) | 6 (5.3) | 61 (54.0) | 7 (6.2) | |

| Practice situation | 0.55 | ||||

| Single specialty | 33 (24.4) | 21 (15.6) | 63 (46.7) | 18 (13.3) | |

| Multispecialty | 16 (25.8) | 10 (16.1) | 26 (41.9) | 10 (16.1) | |

| Other | 6 (31.6) | 6 (31.6) | 5 (26.3) | 2 (10.5) | |

| Private practice | 0.85 | ||||

| Yes | 22 (27.5) | 14 (17.5) | 34 (42.5) | 10 (12.5) | |

| No | 33 (26.0) | 18 (14.2) | 56 (44.1) | 20 (15.8) | |

| Patients per day | 0.35 | ||||

| <15 | 8 (26.7) | 6 (20.0) | 14 (46.7) | 2 (6.7) | |

| 15–19 | 14 (20.0) | 11 (15.7) | 34 (48.6) | 11 (15.7) | |

| 20–29 | 25 (27.5) | 14 (15.4) | 42 (46.2) | 10 (11.0) | |

| 30+ | 9 (36.0) | 5 (20.0) | 5 (20.0) | 6 (24.0) | |

| HPV knowledgeg | 0.03 | ||||

| 0–3 | 21 (22.1) | 22 (23.2) | 34 (35.8) | 18 (19.0) | |

| 4–7 | 35 (28.0) | 17 (13.6) | 61 (48.8) | 12 (9.6) | |

| Aware of risk-based recommendation for MSM | <0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 36 (23.5) | 21 (13.7) | 79 (51.6) | 17 (11.1) | |

| No | 20 (31.3) | 16 (25.0) | 15 (23.4) | 13 (20.3) | |

Italic p values indicate statistically significant differences in chi-square analyses, p ≤ 0.05.

Provider indicated that he/she does not routinely discuss issues related to sexual orientation with male patients 22–26 years old

Provider indicated that he/she does not discuss HPV vaccine with this [ages 22–26] age group

Provider indicated that he/she presents the HPV vaccine as “optional” or “routine” for men ages 22–26

Provider indicated that he/she does routinely discuss issues related to sexual orientation with male patients 22–26 years old

Fisher’s exact test

Written-in specialties included primary care, internal medicine, urgent care, flight surgery, emergency, hospice, and primary care

Sum of seven HPV knowledge items categorized at the median number of correct items

Most of the variation in proportions occurred within the “indeterminate” groups. For example, the majority of male physicians reported discussing HPV vaccine, but not sexual orientation. The opposite was the case for female physicians. Similarly, a larger proportion of Hispanic physicians routinely discussed sexual orientation, but not HPV vaccination.

Physicians who were aware of the recommendation for MSM were more likely to discuss sexual orientation but not HPV vaccination with male patients (OR = 3.49; 95%CI 1.80–6.74). Physicians practicing in clinics that administer vaccines to males were more likely to be in the “low potential” group compared to physicians practicing in clinics that did not administer vaccines to males (OR = 2.73; 95%CI 1.43–5.22, p <0.01). Physicians with low vs. high HPV knowledge were more likely to be in the “high potential” group (OR = 2.20; 95%CI 1.00–4.83, p <0.05).

Discussion

To promote HPV vaccine recommendations for MSM, healthcare providers should assess sexual orientation and discuss the current permissive or routine recommendations for men 22–26 years old. Only a minority of physicians reported engaging with patients in ways that are likely to result in recommendations consistent with current ACIP guidelines. Asking about sexual orientation in clinical practice is recommended by the Institute of Medicine and is a goal in Healthy People 2020 [15]. Sexual orientation involves both sexual behaviors and identities (e.g., gay, bisexual, or heterosexual/straight), which are not always concordant. A healthcare provider needs this information in order to promote patient-centered care and decrease health disparities. Furthermore, discussing HPV vaccination with male patients provides an opportunity to educate them about HPV-related cancers and anogenital warts.

Interestingly, we found that physicians who had higher knowledge about HPV vaccination and awareness of risk-based recommendation for MSM were not routinely discussing both issues with their male patients. As this was a secondary analysis, we were not able to directly assess how physicians used information about sexual orientation when making recommendations about HPV vaccination. One possible explanation is that physicians asked about sexual orientation and gave information about HPV vaccination, as needed, based on that information. Or, they may have failed to clinically connect and/or act on HPV vaccine recommendations based on their assessment data. Future research is needed to understand how providers make recommendations for HPV vaccination among men between 22 and 26 years of age.

Cancer prevention among sexual minorities is best provided as part of a patient-centered approach that considers multiple facets of an individual’s behavior, preferences, needs, and values. Accredited medical education programs for primary care providers have an important role to play in decreeing health disparities among sexual and gender minorities through education of primary care providers on health issues specific to these populations—in this case anal cancer prevention. However, the quality of this instruction appears to be highly varied across institutions [16]. A parallel approach to improving risk-based HPV vaccine coverage is by using electronic medical systems to prompt providers regarding specific recommendations. Prompts regarding HPV vaccination have been effective in changing provider behaviors with regard to adolescent vaccination [17]. These types of prompts, combined with sexual orientation and gender identity data stored in the electronic health record (EHR), have the potential to facilitate risk-based HPV vaccination in adult MSM and to eliminate other health disparities experienced by this population [18]. There is a strong consensus among patients toward the collection of sexual and gender identity [19], and currently, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has included sexual orientation and gender identity data collection to its requirements for EHRs under the Meaningful Use program. Implementation science frameworks may be particularly useful in determining how best to leverage these advances to reduce health disparities in sexual and gender minority populations [20].

This study is limited by non-probability-based sampling and the 51% response rate. We were also unable to examine physician communication regarding HIV infection to fully characterize risk-based recommendations.

Conclusions

This study provides useful insights about physician HPV communication practices in a state with a high proportion of MSM [21]. Three observations relevant to future research can be made from this study: (1) medical education on HPV vaccination should emphasize information on the risk-based recommendations that pertain to routine vaccination of adult males; (2) skills-based interventions are needed to develop patient-provider communication strategies aimed at increasing communication about sexual orientation and HPV vaccination among MSM; and (3) the role of the EHR in facilitating patient-provider communication regarding HPV vaccination among MSM should be explored.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards Participants provided written informed consent and all procedures were approved by the corresponding author’s institutional review board.

Conflict of Interest The parent study from which this secondary analysis was derived was supported by funding from the Bankhead-Coley Cancer Research Program (4BB10).

C.W. has no financial disclosures. S.K. Sutton has no financial disclosures. H.B. Fontenot has no financial disclosures. G. P. Quinn has no financial disclosures. A.R. Giuliano reports receiving a commercial research grant from and is a consultant/advisory board member for Merck & Co. S. T. Vadaparampil has no financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Petrosky E, Bocchini JA, Hariri S et al. (2015) Use of 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 64:300–304 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palefsky JM (2010) Can HPV vaccination help to prevent anal cancer? Lancet Infect Dis 10:815–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson RA, Levine AM, Bernstein L et al. (2013) Changing patterns of anal canal carcinoma in the United States. J Clin Oncol 31:1569–1575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Lowy DR (2008) HPV prophylactic vaccines and the potential prevention of noncervical cancers in both men and women. Cancer 113:3036–3046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grulich AE, Poynten IM, MacHalek DA et al. (2012) The epidemiology of anal cancer. Sex Health 9:504–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Machalek DA, Poynten M, Jin F et al. (2012) Anal human papillomavirus infection and associated neoplastic lesions in men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 13:487–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palefsky JM, Giuliano AR, Goldstone S et al. (2011) HPV vaccine against anal HPV infection and anal intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med 365:1576–1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nadarzynski T, Smith H, Richardson D et al. (2014) Human papillomavirus and vaccine-related perceptions among men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Sex Transm Infect 90:515–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newman PA, Logie CH, Doukas N, Asakura K (2013) HPV vaccine acceptability among men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect 89:568–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McRee A, Reiter PL, Chantala K, Brewer NT (2010) Does framing human papillomavirus vaccine as preventing cancer in men increase vaccine acceptability? Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 19:1937–1944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reiter PL, McRee A, Katz ML, Paskett ED (2015) Human papillomavirus vaccination among young adult gay and bisexual men in the United States. Am J Public Health 105:96–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meites E, Krishna NK, Markowitz LE, Oster AM (2013) Health care use and opportunities for human papillomavirus vaccination among young men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 40:154–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wheldon CW, Kirby RS (2013) Are there differing patterns of health care access and utilization among male sexual minorities in the United States? J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv 25:24–36 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vadaparampil ST, Malo TL, Sutton S et al. (2016) Missing the target for routine human papillomavirus vaccination: consistent and strong physician recommendations are lacking for 11- to 12-year-old males. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 25:1435–1446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institute of Medicine (2013) Collecting sexual orientation and gender identity data in electronic health records: workshop summary. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L et al. (2011) Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-related content in undergraduate medical education. J Am Med Assoc 306:971–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruffin MT, Plegue MA, Rockwell PG et al. (2015) Impact of an electronic health record (EHR) reminder on human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine initiation and timely completion. J Am Board Fam Med 28:324–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callahan EJ, Hazarian S, Yarborough M, Sánchez JP (2014) Eliminating LGBTIQQ health disparities: the associated roles of electronic health records and institutional culture. Hast Cent Rep 44:S48–S52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cahill S, Singal R, Grasso C et al. (2014) Do ask, do tell: high levels of acceptability by patients of routine collection of sexual orientation and gender identity data in four diverse American community health centers. PLoS One 9:e107104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nemeth LS, Feifer C, Stuart GW, Ornstein SM (2008) Implementing change in primary care practices using electronic medical records: a conceptual framework. Implement Sci 3:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lieb S, Thompson DR, Misra S et al. (2009) Estimating populations of men who have sex with men in the southern United States. J Urban Health 86:887–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]