Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) of cefiderocol poses challenges because of its unique mechanism of action (i.e., requiring an iron-depleted state) and due to differences in interpretative criteria established by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Our objective was to compare cefiderocol disk diffusion methods (DD) to broth microdilution (BMD) for AST of Gram-negative bacilli (GNB).

KEYWORDS: cefiderocol, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, broth microdilution, disk diffusion

ABSTRACT

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) of cefiderocol poses challenges because of its unique mechanism of action (i.e., requiring an iron-depleted state) and due to differences in interpretative criteria established by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Our objective was to compare cefiderocol disk diffusion methods (DD) to broth microdilution (BMD) for AST of Gram-negative bacilli (GNB). Cefiderocol AST was performed on consecutive carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE; 58 isolates) and non-glucose-fermenting GNB (50 isolates) by BMD (lyophilized panels; Sensititre; Thermo Fisher) and DD (30 μg; research-use-only [RUO] MASTDISCS and FDA-cleared HardyDisks). Results were interpreted using FDA (prior to 28 September 2020 update), EUCAST, and investigational CLSI breakpoints (BPs). Categorical agreement (CA), minor errors (mE), major errors (ME), and very major errors (VME) were calculated for DD methods. The susceptibilities of all isolates by BMD were 72% (FDA), 75% (EUCAST) and 90% (CLSI). For DD methods, EUCAST BPs demonstrated lower susceptibility at 65% and 66%, compared to 74% and 72% (FDA) and 87% and 89% (CLSI) by HardyDisks and MASTDISCS, respectively. CA ranged from 75% to 90%, with 8 to 25% mE, 0 to 19% ME, and 0 to 20% VME and varied based on disk, GNB, and BPs evaluated. Both DD methods performed poorly for Acinetobacter baumannii complex. There is considerable variability when cefiderocol ASTs are interpreted using CLSI, FDA, and EUCAST breakpoints. DD offers a convenient alternative approach to BMD methods for cefiderocol AST, with the exception of A. baumannii complex isolates.

INTRODUCTION

Antimicrobial resistance is a pressing concern in the United States and globally, with an estimated 157,000 deaths from multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli (MDR GNB) in the United States annually (1). Arguably, the greatest antimicrobial resistance threat is that of carbapenem-resistant organisms (2). Carbapenem resistance among Gram-negative bacilli can be mediated by non-carbapenemase-mediated mechanisms (e.g., cell wall permeability defects combined with extended-spectrum β-lactamase or AmpC β-lactamase production) or carbapenemase mediated. Carbapenemases are enzymes that can hydrolyze all or most β-lactam agents, including carbapenems, the broadest class of antimicrobials currently available. Commonly encountered carbapenemases in the United States include Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPCs), New Delhi metallo-β-lactamases (NDMs), and OXA-48-like enzymes. Although commonly found in Enterobacterales, these carbapenemases are occasionally identified in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii (3). For P. aeruginosa, most carbapenem resistance is non-carbapenemase mediated (OprD porin mutations combined with hyperexpression of AmpC or upregulation of efflux pumps), and for the small proportion of isolates that are carbapenemase producers (∼2% of carbapenem-resistant isolates), Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamases (VIM) are the most common in the United States (4, 5). On the other hand, carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter spp. is mediated mostly via acquisition of Ambler class D enzymes, in particular, OXA-23 and OXA-24 enzymes (6). Novel β-lactam–β-lactamase inhibitor combinations (e.g., ceftazidime-avibactam, imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam, and meropenem-vaborbactam) may provide protection against non-carbapenemase-mediated carbapenem resistance mechanisms, KPCs, and OXA-48-like carbapenemases but not against NDM and other metallo-β-lactamases (MBL) (7).

Cefiderocol, a novel siderophore-conjugated cephalosporin, has activity against a broad array of MDR GNB, including both carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales and non-glucose-fermenting organisms. The cephalosporin portion of cefiderocol is structurally similar to ceftazidime and cefepime. The novelty lies in the presence of a catechol moiety on the C-3 side chain, which mimics naturally occurring siderophores (8). Cefiderocol is able to chelate ferric iron and thus can be actively transported into the periplasmic space via bacterial iron transport systems (9). Within the periplasmic space, the cephalosporin component binds to penicillin-binding protein 3 (PBP3), prevents side chain cross-linking in peptidoglycan synthesis, and ultimately leads to bacterial demise.

As cefiderocol utilizes active iron transport for bacterial entry and iron transporters are upregulated under iron-depleted conditions, as occurs in vivo, special consideration for iron concentrations of media is required when cefiderocol antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) is performed (10). Accurate cefiderocol MICs determined through broth microdilution (BMD) require the use of iron-depleted cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (ID-CAMHB), as standard CAMHB does not provide reproducible MICs that accurately reflect expected in vivo activity (10). This can pose challenges for microbiology laboratories, because both preparation of ID-CAMHB and performance of BMD are cumbersome. Alternatively, AST approaches have been developed that improve the ease of obtaining cefiderocol results, including the Sensititre lyophilized BMD panel (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and disk diffusion (DD) methods. The Sensititre BMD panel includes cefiderocol with an iron chelator embedded in wells, allowing reconstitution of the entire panel, including cefiderocol wells, with standard CAMHB. Similarly, in vitro testing by DD on Mueller-Hinton agar does not require iron depletion, as the iron is sufficiently bound within the agar (11).

Cefiderocol AST interpretation also presents challenges. Three different sets of AST interpretive criteria currently exist, from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (12), U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA; https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-resources/cefiderocol-injection), and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) (13), each with different nuances regarding specific organisms to which breakpoints can be applied. Our objective was to compare cefiderocol DD to Sensititre BMD lyophilized panels for AST of clinically relevant MDR GNB and to investigate differences in their performance characteristics by applying CLSI, FDA (prior to 28 September 2020 update), and EUCAST interpretive criteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolate selection.

One hundred eight consecutive carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE; 58 isolates), carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (14 isolates), carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii complex (14 isolates), Achromobacter xylosoxidans (8 isolates), Burkholderia cepacia complex (3 isolates), and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (11 isolates) clinical isolates from unique patients in 2017 were included. Carbapenem resistance was defined as testing resistant to ertapenem for CRE and meropenem for P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii complex. Specific CRE included Citrobacter freundii complex (2 isolates), Enterobacter cloacae complex (15 isolates), Escherichia coli (15 isolates), Klebsiella aerogenes (2 isolates), Klebsiella oxytoca (6 isolates), K. pneumoniae (15 isolates), and Serratia marcescens (3 isolates). Of the 58 CRE, 26 (44%) were carbapenemase-producing CRE (CP-CRE), including those producing KPC (21 isolates), NDM and OXA-181 (3 isolates), OXA-181 (1 isolate), and Serratia marcescens enzymes (SME) (1 isolate).

Laboratory methods.

Isolates were identified using matrix-assisted laser-desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (Bruker Daltonics Inc., Billerica, MA). AST results were determined using the BD Phoenix automated system (BD Diagnostics, Sparks, MD) or DD for mucoid isolates following CLSI guidelines (12), all per routine Johns Hopkins Hospital Medical Microbiology Laboratory protocol. Isolates were stored at −80°C in glycerol until further testing was performed.

Frozen isolates were subcultured twice to tryptic soy agar with 5% sheep blood. Cefiderocol AST was carried out using DD with research-use-only 30-μg cefiderocol MASTDISCS (Mast Group Ltd., Bootle, United Kingdom) and custom, lyophilized Sensititre BMD panels (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), using the same standardized inoculum. The BMD panel contained cefiderocol concentrations ranging from 0.03 to 64 μg/ml and a proprietary chelator in the wells, removing the requirement for ID-CAMHB. The cefiderocol lyophilized panel has been shown to be substantially equivalent to reference BMD and has received FDA clearance (14) (https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K193538). A 30-μl aliquot of the standardized inoculum was added to 11 ml Sensititre CAMHB with TES [N-tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid] buffer for a final concentration of 1 × 105 CFU/ml. The panels were inoculated with 50 μl in each well and incubated for 18 to 24 h (varying by organism as appropriate) at 35 ± 2°C in an aerobic non-CO2 incubator. As FDA-cleared, 30-μg cefiderocol HardyDisks (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, CA) became available at a later date, the HardyDisk results were obtained and interpreted separately. The DD methods were carried out on standard Mueller-Hinton agar incubated for 18 to 24 h at 35 ± 2°C following CLSI guidelines (12). If a difference of ≥5 mm was observed between the HardyDisk result and the previous MASTDISC result, both procedures were repeated from the same inoculum, and the repeat result was used for the analysis. Quality control organisms were prepared each day of testing, including E. coli ATCC 25922 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853.

MIC interpretation.

The cefiderocol MIC was interpreted as the first well where visible bacterial growth was inhibited. When trailing endpoints occurred, the MIC was read at 80% inhibition. Trailing was defined as multiple wells of tiny or faint growth relative to the growth control. Disk zone diameters were read using the innermost colony-free zone when pinpoint colonies were observed within the zone (see reference 15 for examples of trailing endpoints and pinpoint colonies). Results were interpreted by applying three sets of breakpoints, i.e., (i) investigational CLSI (12), (ii) FDA prior to the 28 September 2020 update (https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-resources/cefiderocol-injection), and (iii) EUCAST (13) breakpoints, as appropriate (Table 1). The MIC50 and MIC90 were determined for each species by identifying the MIC that would inhibit growth of at least 50% and 90% of the isolates, respectively. DD zone diameter results were compared to BMD results for each of the three sets of breakpoint interpretations. Zone diameters were graphed using GraphPad Prism 8.1.2. Results were compared using linear regression.

TABLE 1.

Breakpoint interpretations applied to categorize cefiderocol antimicrobial susceptibility testing resultsa

| Organism | Investigational CLSI breakpoints |

FDA breakpointse

|

EUCAST breakpoints |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (μg/ml) |

Disk zone diam (mm) |

MIC (μg/ml) |

Disk zone diam (mm) |

MIC (μg/ml) |

Disk zone diam (mm) |

|||||||||||

| S | I | R | S | I | R | S | I | R | S | I | R | S | R | S | R | |

| Enterobacteralesb | ≤4 | 8 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 12–15 | ≤11 | ≤2 | 4 | ≥8 | ≥18 | 14–17 | ≤13 | ≤2 | >2 | ≥22 | <22 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ≤4 | 8 | ≥16 | ≥18 | 13–17 | ≤12 | ≤1 | 2 | ≥4 | ≥25 | 19–24 | ≤18 | ≤2 | >2 | ≥22 | <22 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | ≤4 | 8 | ≥16 | ≥15 | 11–14 | ≤10 | ≤2c | >2c | ≥17d | |||||||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | ≤4 | 8 | ≥16 | ≥17 | 13–16 | ≤12 | ≤2c | >2c | ≥20d | |||||||

| Achromobacter xylosoxidans | ≤2c | >2c | ||||||||||||||

| Burkholderia cepacia complex | ≤2c | >2c | ||||||||||||||

CLSI, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; EUCAST, European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

FDA breakpoints for the Enterobacterales (listed as Enterobacteriaceae on the FDA website) are specific for E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. mirabilis, and E. cloacae complex. These breakpoints were used to interpret results for all Enterobacterales in this study.

Non-species-specific pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) breakpoint.

EUCAST provided disk correlates associated with the susceptible PK-PD breakpoint for A. baumannii and S. maltophilia. Although the PK-PD breakpoint for S is set at ≤2 μg/ml, there were no S. maltophilia isolates with MICs of >0.5 μg/ml. Thus, the disk correlate for S. maltophilia is for isolates with MICs of ≤0.5 μg/ml.

The FDA breakpoints applied in this study were the published breakpoints prior to the 28 September 2020 update.

Agreement analysis.

Using BMD as the reference method, categorical agreement (CA), minor errors (mE), major errors (ME), and very major errors (VME) were assessed according to standard definitions. Acceptance criteria included ≥90% CA, ≤10% mE, and ≤3% ME and VME, based on CLSI guidelines (16).

RESULTS

Cefiderocol broth microdilution.

The cefiderocol MIC range was highly variable depending on the species of bacteria, with an overall MIC range of ≤0.03 to 64 μg/ml. The MIC range, MIC50, MIC90, and percent susceptible, intermediate, and resistant isolates are summarized in Table 2, with various breakpoint interpretations applied. E. coli, K. aerogenes, K. oxytoca, and S. marcescens uniformly displayed 100% susceptibility to cefiderocol regardless of the breakpoint criteria applied (Table 2). In contrast, both E. cloacae and K. pneumoniae had much more variable results, with susceptibility ranging from 60% to 90% and 53% to 80%, respectively, depending on the breakpoint criteria used. Similarly, both P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii had wide ranges in their susceptibility, 57% to 93% and 36% to 86%, respectively. When the EUCAST non-species-specific pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) breakpoints were applied, all A. xylosoxidans and B. cepacia complex isolates tested susceptible. Similarly, S. maltophilia displayed 100% susceptibility to cefiderocol, regardless of the breakpoint criteria applied.

TABLE 2.

Summary of cefiderocol broth microdilution resultsa

| Organism(s) | No. of isolates | MIC (μg/ml) |

% (no.) with breakpoint interpretation |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLSI (investigational) |

FDAb

|

EUCAST |

||||||||||

| Range | 50% | 90% | S | I | R | S | I | R | S | R | ||

| Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales | 58 | ≤0.03–64 | 0.5 | 8 | 88 (51) | 3 (2) | 9 (5) | 76 (44) | 12 (7) | 12 (7) | 76 (44) | 24 (14) |

| Carbapenemase-producing CRE | 26 | ≤0.03–32 | 0.25 | 4 | 92 (24) | 0 | 8 (2) | 77 (20) | 15 (4) | 8 (2) | 77 (20) | 23 (6) |

| Non-carbapenemase-producing CRE | 32 | 0.06–64 | 0.5 | 16 | 85 (27) | 6 (2) | 9 (3) | 75 (24) | 9 (3) | 16 (5) | 75 (24) | 25 (8) |

| Citrobacter freundii complex | 2 | 0.06–8 | 0.06 | 8 | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 0 | 50 (1) | 0 | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 1 (50) |

| Enterobacter cloacae complex | 15 | 0.06–64 | 0.5 | 16 | 90 (12) | 7 (1) | 13 (2) | 60 (9) | 20 (3) | 20 (3) | 60 (9) | 40 (6) |

| Escherichia coli | 15 | 0.06–2 | 0.25 | 1 | 100 (15) | 0 | 0 | 100 (15) | 0 | 0 | 100 (15) | 0 |

| Klebsiella aerogenes | 2 | 0.5–1 | 0.5 | 1 | 100 (2) | 0 | 0 | 100 (2) | 0 | 0 | 100 (2) | 0 |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 6 | ≤0.03–1 | 0.06 | 1 | 100 (6) | 0 | 0 | 100 (6) | 0 | 0 | 100 (6) | 0 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 15 | 0.06–32 | 2 | 32 | 80 (12) | 0 | 20 (3) | 53 (8) | 27 (4) | 20 (3) | 53 (8) | 47 (7) |

| Serratia marcescens | 3 | ≤0.03–2 | ≤0.03 | 2 | 100 (3) | 0 | 0 | 100 (3) | 0 | 0 | 100 (3) | 0 |

| Non-glucose-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli | 50 | ≤0.03–8 | 0.5 | 4 | 92 (36) | 5 (2) | 3 (1) | 57 (8) | 14 (2) | 29 (4) | 74 (37) | 26 (13) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 14 | 0.5–8 | 1 | 8 | 93 (13) | 7 (1) | 0 | 57 (8) | 14 (2) | 29 (4) | 71 (10) | 29 (4) |

| Acinetobacter baumannii complex | 14 | 0.06 | 4 | 8 | 86 (12) | 7 (1) | 7 (1) | 36 (5)c | 64 (9)c | |||

| Achromobacter xylosoxidans | 8 | 0.06–1 | 0.25 | 1 | 100 (8)c | 0 | ||||||

| Burkholderia cepacia complex | 3 | 0.12–0.25 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 100 (3)c | 0 | ||||||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 11 | ≤0.03–0.5 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 100 (11) | 0 | 0 | 100 (11)c | 0 | |||

| All isolates | 108 | ≤0.03–64 | 0.5 | 4 | 90 (87) | 4 (4) | 6 (6) | 72 (52) | 13 (9) | 15 (11) | 75 (81) | 25 (27) |

CLSI, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; EUCAST, European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

Breakpoints used for this analysis were prior to the 28 September 2020 update. FDA breakpoints for the Enterobacterales (listed as Enterobacteriaceae on the FDA website) are specific for E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. mirabilis, and E. cloacae complex. These breakpoints were used to interpret results for all Enterobacterales in this study.

Non-species-specific pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) breakpoints.

Overall, Enterobacterales susceptibilities were 88% when CLSI breakpoints were applied, which was higher than those obtained with either FDA or EUCAST breakpoints, at 76% each. MICs of ≥4 μg/ml were observed in 15 isolates, including 9 non-CP-CRE isolates (7 E. cloacae isolates, 1 C. freundii complex isolate, and 1 K. pneumoniae isolate) and 6 CP-CRE isolates, which were all K. pneumoniae (3 KPC-producing and 3 NDM- and OXA-181-producing isolates). Trailing endpoints were observed for 3 CRE, including 1 S. marcescens isolate (MIC, 2 μg/ml), 1 E. coli isolate (MIC, 0.12 μg/ml), and 1 K. oxytoca isolate (MIC, 1 μg/ml).

Similar to the CRE, P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii complex had higher susceptibilities when CLSI breakpoints were applied than with other available breakpoints. A. baumannii complex had the most striking difference in susceptibility, driven by 6 isolates with MICs of 4 μg/ml, which were susceptible by CLSI but resistant by EUCAST criteria. Three (21%) A. baumannii complex isolates were the only nonfermenters that demonstrated trailing endpoints, with MICs of 0.5, 2, and 4 μg/ml.

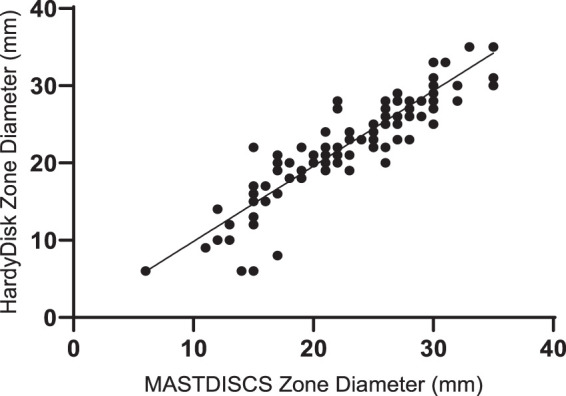

Cefiderocol disk diffusion.

Cefiderocol disk diffusion susceptibility results are summarized in Table 3. Correlation between the zone diameter results of the two disks is shown in Fig. 1. A strong correlation was noted between the HardyDisks and MASTDISCS (R2 = 0.84). Testing of three isolates (1 E. cloacae complex, 1 K. oxytoca, and 1 P. aeruginosa isolate) was repeated due to ≥5-mm differences between the disk results, which resolved on repeat testing. Pinpoint colonies were observed for 7 organisms and occurred with the same frequency with both disks: 5 A. baumannii complex isolates, 1 K. oxytoca isolate, and 1 C. freundii complex isolate.

TABLE 3.

Summary of cefiderocol disk diffusion results for HardyDisks and MASTDISCSa

| Organism(s) | No. of isolates | % (no.) with breakpoint interpretation |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-μg HardyDisks (FDA cleared) |

30-μg MASTDISCS (RUO) |

||||||||||||||||

| CLSI (investigational) |

FDAb

|

EUCAST |

CLSI (investigational) |

FDAb

|

EUCAST |

||||||||||||

| S | I | R | S | I | R | S | R | S | I | R | S | I | R | S | R | ||

| Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales | 58 | 88 (51) | 9 (5) | 3 (2) | 84 (49) | 7 (4) | 9 (5) | 64 (37) | 36 (21) | 90 (52) | 9 (5) | 2 (1) | 79 (46) | 16 (9) | 5 (3) | 66 (38) | 34 (20) |

| Carbapenemase-producing CRE | 26 | 88 (23) | 12 (3) | 0 | 88 (23) | 4 (1) | 8 (2) | 65 (17) | 35 (9) | 88 (23) | 12 (3) | 0 | 81 (21) | 19 (5) | 0 | 69 (18) | 31 (8) |

| Non-carbapenemase-producing CRE | 32 | 88 (28) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 81 (26) | 9 (3) | 9 (3) | 63 (20) | 37 (12) | 91 (29) | 6 (2) | 3 (1) | 78 (25) | 13 (4) | 9 (3) | 63 (20) | 37 (12) |

| Citrobacter freundii complex | 2 | 100 (2) | 0 | 0 | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 0 | 0 | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 0 | 0 | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 0 | 0 | 100 (2) |

| Enterobacter cloacae complex | 15 | 80 (12) | 13 (2) | 7 (1) | 73 (11) | 13 (2) | 13 (2) | 47 (7) | 53 (8) | 86 (13) | 7 (1) | 7 (1) | 67 (10) | 20 (3) | 13 (2) | 53 (8) | 47 (7) |

| Escherichia coli | 15 | 100 (15) | 0 | 0 | 100 (15) | 0 | 0 | 80 (12) | 20 (3) | 100 (15) | 0 | 0 | 100 (15) | 0 | 0 | 87 (13) | 13 (2) |

| Klebsiella aerogenes | 2 | 100 (2) | 0 | 0 | 100 (2) | 0 | 0 | 100 (2) | 0 | 100 (2) | 0 | 0 | 100 (2) | 0 | 0 | 100 (2) | 0 |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 6 | 83 (5) | 17 (1) | 0 | 83 (5) | 17 (1) | 0 | 83 (5) | 17 (1) | 100 (6) | 0 | 0 | 83 (5) | 17 (1) | 0 | 83 (5) | 17 (1) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 15 | 80 (12) | 13 (2) | 7 (1) | 80 (12) | 0 | 20 (3) | 53 (8) | 47 (7) | 73 (11) | 27 (4) | 0 | 67 (10) | 27 (4) | 7 (1) | 47 (7) | 53 (8) |

| Serratia marcescens | 3 | 100 (3) | 0 | 0 | 100 (3) | 0 | 0 | 100 (3) | 0 | 100 (3) | 0 | 0 | 100 (3) | 0 | 0 | 100 (3) | 0 |

| Non-glucose-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli | 39 | 85 (33) | 3 (1) | 13 (5) | 29 (4) | 64 (9) | 7 (1) | 67 (26) | 33 (13) | 87 (34) | 10 (4) | 3 (1) | 43 (6) | 43 (6) | 14 (2) | 67 (26) | 33 (13) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 14 | 100 (14) | 0 | 0 | 29 (4) | 64 (9) | 7 (1) | 64 (9) | 36 (5) | 93 (13) | 7 (1) | 0 | 43 (6) | 43 (6) | 14 (2) | 71 (10) | 29 (4) |

| Acinetobacter baumannii complex | 14 | 57 (8) | 7 (1) | 36 (5) | 43c (6) | 57c (8) | 71 (10) | 21 (3) | 7 (1) | 36 (5)c | 64 (9)c | ||||||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 11 | 100 (11) | 0 | 0 | 100c (11) | 0c | 100 (11) | 0 | 0 | 100 (11)c | 0 | ||||||

| All isolates | 97 | 87 (84) | 6 (6) | 7 (7) | 74 (53) | 18 (13) | 8 (6) | 65 (63) | 35 (34) | 89 (86) | 9 (9) | 2 (2) | 72 (52) | 21 (15) | 7 (5) | 66 (64) | 34 (33) |

CLSI, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; EUCAST, European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; MIC, MIC; S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant; RUO, research use only.

Breakpoints used for this analysis were prior to the 28 September 2020 update. FDA breakpoints for the Enterobacterales (listed as Enterobacteriaceae on the FDA website) are specific for E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. mirabilis, and E. cloacae complex. These breakpoints were used to interpret results for all Enterobacterales in this study.

EUCAST provided disk correlates associated with the susceptible PK-PD breakpoint for A. baumannii and S. maltophilia. Although the PK-PD breakpoint for S is set at ≤2 μg/ml, there were no S. maltophilia isolates with MICs of >0.5 μg/ml. Thus, the disk correlate for S. maltophilia is for isolates with MICs of ≤0.5 μg/ml.

FIG 1.

Zone diameter comparison between HardyDisks and MASTDISCS (cefiderocol, 30 μg). R2 = 0.84; slope = 0.97; y intercept = 0.09.

EUCAST breakpoints demonstrated lower overall susceptibility at 65% and 66%, compared to 74% and 72% for FDA and 87% and 89% for CLSI breakpoints, by HardyDisks and MASTDISCS, respectively. Similar to BMD, the species with the consistently lowest percent susceptibility to cefiderocol by both disk brands was A. baumannii complex. Most species had similar or identical results between BMD and DD. However, there were some notable differences observed between E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and E. cloacae complex between BMD and DD methods.

Correlation of HardyDisks with BMD.

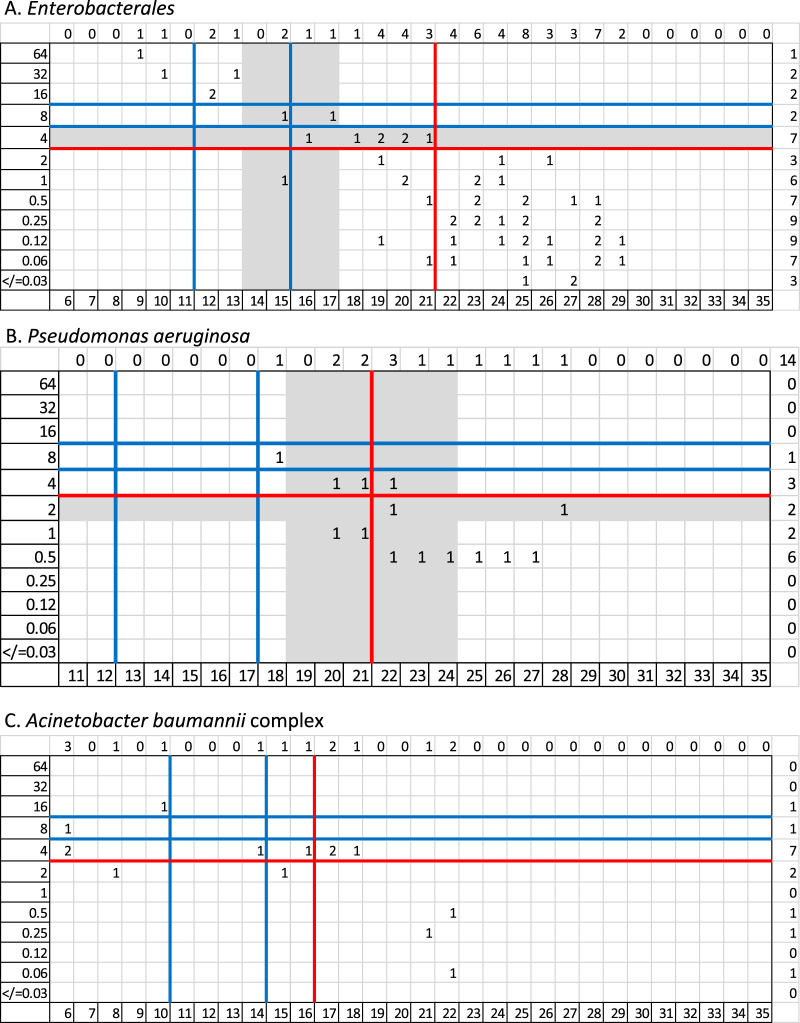

The distribution of BMD cefiderocol MICs to HardyDisk zone diameters is shown in Fig. 2. Collectively, CA ranged from 75% to 89%, 8 to 25% mE, 0 to 17% ME, and 0 to 12% VME, with variations by species and breakpoint criteria applied (Table 4). CLSI interpretations provided the highest correlation, with 89% CA, 8% mE, and 3% ME. However, neither the CLSI, FDA, nor EUCAST susceptibility categorization met all acceptance criteria when all isolates were evaluated. When A. baumannii complex isolates were excluded from the CLSI results, acceptable results were obtained, with 93% CA, 8% mE, and no ME or VME. Using EUCAST guidance, CA was achieved for 85% of isolates and reached 88% when A. baumannii complex was excluded. However, as there is no EUCAST intermediate category, ME were observed for 17% of isolates and VME for 12% of isolates. VME were observed with 3 A. baumannii complex isolates and 1 P. aeruginosa isolate. FDA disk correlates had the lowest performance, with 75% CA and 25% mE. There were 18 mE, including mE in 9 Enterobacterales and 9 P. aeruginosa isolates. The majority of Enterobacterales tested more susceptible by DD, while P. aeruginosa was variable (4/9 isolates tested more susceptible and 5/9 tested more resistant). No ME or VME were observed. When the Enterobacterales were limited to the specific species with FDA breakpoints compared to all Enterobacterales, similar results were obtained, i.e., CA of 84% and 15% mE.

FIG 2.

Distribution of cefiderocol MICs to zone diameters for HardyDisks. Broth microdilution MICs (micrograms per milliliter) are on the x axis, and zone diameters (millimeters) are on the y axis. The blue lines denote the investigational CLSI breakpoints, the red lines denote EUCAST breakpoints, and the gray highlighted areas denote the intermediate category determined by FDA breakpoints (applying the breakpoints prior to the 28 September 2020 update).

TABLE 4.

Disk diffusion performance characteristics compared to broth microdilutiona

| Organism(s) | No. of isolates | % (no.) with agreement or error |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-μg HardyDisks (FDA cleared) |

30-μg MASTDISCS (RUO) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| CLSI |

FDAb

(n = 73) |

EUCAST |

CLSI |

FDAb

|

EUCAST |

||||||||||||||||||

| CA | mE | ME | VME | CA | mE | ME | VME | CA | ME | VME | CA | mE | ME | VME | CA | mE | ME | VME | CA | ME | VME | ||

| Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales | 58 | 91 (53) | 9 (5) | 0 | 0 | 84 (49) | 16 (9) | 0 | 0 | 88 (51) | 17 (7) | 0 | 88 (51) | 12 (7) | 0 | 86 (50) | 14 (8) | 0 | 0 | 90 (52) | 14 (6) | 0 | |

| Carbapenemase-producing CRE | 26 | 88 (23) | 12 (3) | 0 | 0 | 81 (21) | 19 (5) | 0 | 0 | 88 (23) | 12 (3) | 0 | 88 (23) | 12 (3) | 0 | 0 | 81 (21) | 19 (5) | 0 | 0 | 92 (24) | 8 (2) | 0 |

| Non-carbapenemase-producing CRE | 32 | 94 (30) | 6 (2) | 0 | 0 | 88 (28) | 12 (4) | 0 | 0 | 88 (28) | 12 (4) | 0 | 88 (28) | 12 (4) | 0 | 0 | 91 (29) | 9 (3) | 0 | 0 | 88 (28) | 12 (4) | 0 |

| Citrobacter freundii complex | 2 | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 0 | 0 | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 0 | 0 | 50 (1) | 100 (1) | 0 | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 0 | 0 | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 0 | 0 | 50 (1) | 100 (1) | 0 |

| Enterobacter cloacae complex | 15 | 93 (14) | 7 (1) | 0 | 0 | 80 (12) | 20 (3) | 0 | 0 | 87 (13) | 25 (2) | 0 | 87 (12) | 13 (2) | 0 | 0 | 87 (13) | 13 (2) | 0 | 93 (14) | 7 (1) | 0 | |

| Escherichia coli | 15 | 100 (15) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 (15) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 (12) | 20 (3) | 0 | 100 (15) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 (15) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 87 (13) | 13 (2) | 0 |

| Klebsiella aerogenes | 2 | 100 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 (2) | 0 | 0 | 100 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 6 | 83 (5) | 17 (1) | 0 | 0 | 83 (5) | 17 (1) | 0 | 0 | 83 (5) | 17 (1) | 0 | 100 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 83 (5) | 17 (1) | 0 | 0 | 83 (5) | 17 (1) | 0 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 15 | 87 (13) | 13 (2) | 0 | 0 | 73 (11) | 27 (4) | 0 | 0 | 100 (15) | 0 | 0 | 73 (11) | 27 (4) | 0 | 0 | 73 (11) | 27 (4) | 0 | 0 | 83 (14) | 7 (1) | 0 |

| Serratia marcescens | 3 | 100 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 (3) | 0 | 0 | 100 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Non-glucose-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli | 39 | 85 (33) | 8 (3) | 12 (3) | 0 | 36 (5) | 64 (9) | 0 | 0 | 79 (31) | 15 (4) | 31 (4) | 85 (33) | 15 (6) | 0 | 0 | 50 (7) | 43 (6) | 0 | 25 (1) | 90 (35) | 8 (2) | 15 (2) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 14 | 93 (13) | 7 (1) | 0 | 0 | 36 (5) | 64 (9) | 0 | 0 | 79 (11) | 14 (2) | 25 (1) | 86 (12) | 14 (2) | 0 | 0 | 50 (7) | 43 (6) | 0 | 25 (1) | 86 (12) | 10 (1) | 25 (1) |

| Acinetobacter baumannii complex | 14 | 64 (9) | 14 (2) | 25 (3) | 0 | 64 (9) | 20 (2) | 33 (3) | 71 (10) | 29 (4) | 0 | 0 | 86 (12)c | 20 (1)c | 11 (1)c | ||||||||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 11 | 100 (11) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 (11) | 0 | 0 | 100 (11) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 (11)c | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| All isolates | 97 | 89 (86) | 8 (8) | 3 (3) | 0 | 75 (54) | 25 (18) | 0 | 85 (82) | 17 (11) | 12 (4) | 87 (84) | 13 (13) | 0 | 0 | 79 (57) | 19 (14) | 0 | 20 (1) | 90 (87) | 13 (8) | 12 (4) | |

CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; CLSI, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; EUCAST, European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant; RUO, research use only.

Breakpoints used for this analysis were prior to the 28 September 2020 update. The FDA breakpoints for the Enterobacterales (listed as Enterobacteriaceae on the FDA website) are specific for E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. mirabilis, and E. cloacae complex. However, we used the breakpoints to interpret all Enterobacterales results in this study.

EUCAST provided disk correlates associated with the susceptible PK-PD breakpoint for A. baumannii and S. maltophilia. Although the PK-PD breakpoint for S is set at ≤2 μg/ml, there were no S. maltophilia isolates tested by EUCAST with MICs of >0.5 μg/ml. Thus, the disk correlate for S. maltophilia is for isolates with MICs of ≤0.5 μg/ml.

Correlation of MASTDISCS and BMD.

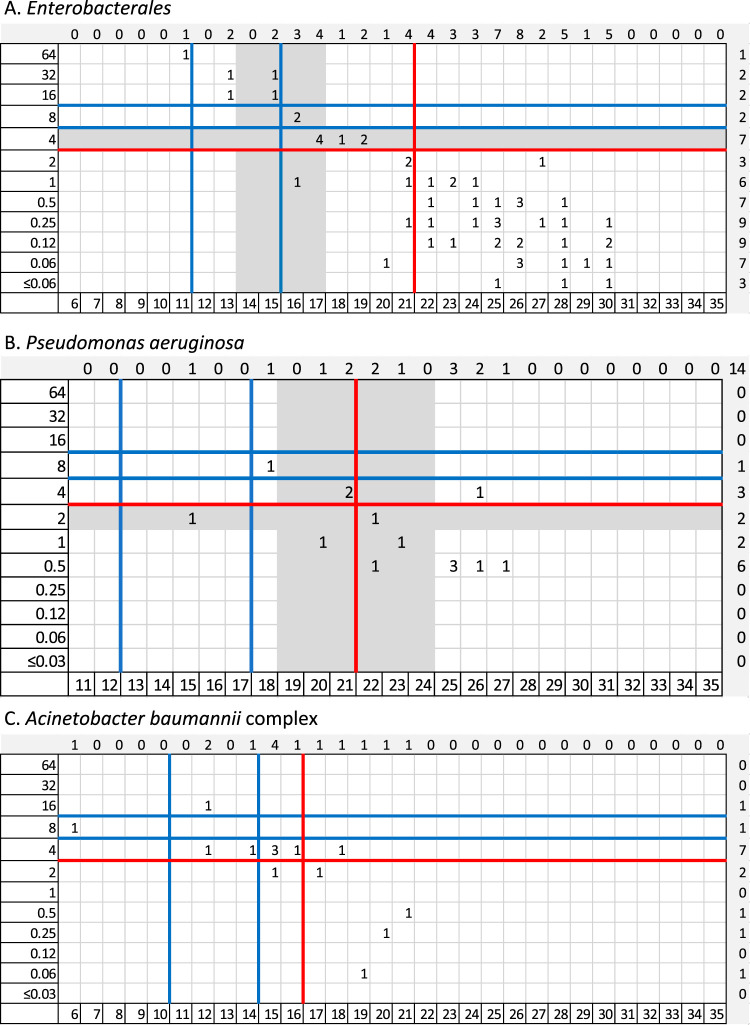

The distribution of cefiderocol MICs to MASTDISCS zone diameters is displayed in Fig. 3. When all isolates were evaluated, CA ranged from 79% to 90%, with 13 to 19% mE, 0 to 13% ME, and 0 to 12% VME, with variations based on species and breakpoint criteria applied (Table 4). CA was slightly higher with the MASTDISCS than the HardyDisks with FDA and EUCAST breakpoints. Similar to the HardyDisk results, neither the CLSI, FDA, nor EUCAST results met all acceptance criteria when all isolates were analyzed. EUCAST interpretations provided the highest CA at 90%, with 13% ME and 12% VME. VME were limited to non-glucose-fermenting organisms. Regarding the Enterobacterales only, the CA was 88% with 12% mE when all isolates were evaluated by CLSI breakpoints. The CA was 90% for the Enterobacterales, with 14% ME and no VME, when EUCAST breakpoints were applied. MASTDISCS and BMD results were similar with the Enterobacterales and the non-glucose fermenters. FDA breakpoints resulted in a categorical agreement of only 79%, with 19% mE and 20% VME (1 P. aeruginosa isolate).

FIG 3.

Distribution of cefiderocol MICs to zone diameters for MASTDISCS. Broth microdilution MICs (micrograms per milliliter) are on the x axis, and zone diameters (millimeters) are on the y axis. The blue lines denote the investigational CLSI breakpoints, the red lines denote EUCAST breakpoints, and the gray highlighted areas denote the intermediate category determined by FDA breakpoints (applying the breakpoints prior to the 28 September 2020 update).

DISCUSSION

Cefiderocol is a welcome addition to the existing antimicrobial armamentarium. For several pathogens and resistance mechanisms, cefiderocol functions as the last active agent before pan-resistance ensues, owing to its broad activity against Gram-negative organisms, which underscores the importance of accurate cefiderocol AST methods. Cefiderocol AST poses challenges both because of its unique mechanism of action (i.e., requiring an iron-depleted state to replicate in vivo efficacy) and because of differences in established susceptibility interpretative criteria established by the CLSI, FDA, and EUCAST (15). We evaluated baseline susceptibility of cefiderocol against 108 MDR GNB clinical isolates and the accuracy of two different cefiderocol disks (i.e., HardyDisks and MASTDISCS) compared to BMD.

Overall, the MICs ranged from ≤0.03 to 64 μg/ml, with a MIC50 of 0.5 μg/ml for all GNB and MIC90s of 4 μg/ml for non-glucose fermenters and 8 μg/ml for CRE. These results are similar to those of other studies that limited testing to GNB found to be not carbapenem susceptible (17, 18). Interestingly, the MIC90 was 4-fold higher among non-carbapenemase-producing CRE (16 μg/ml) than CP-CRE (4 μg/ml) in our cohort. Cefiderocol susceptibility of CRE determined by BMD varied from 76% (FDA and EUCAST) to 88% (CLSI). Although susceptibility was lower by all breakpoints for non-CP-CRE than CP-CRE, there were no significant differences. Susceptibility of the non-glucose-fermenting organisms determined by BMD varied from 57% (FDA) to 74% (EUCAST) to 92% (CLSI). As the FDA and EUCAST cefiderocol breakpoints are more stringent than the CLSI investigational breakpoints, it is not surprising that susceptibility to cefiderocol across organisms is higher when CLSI interpretive criteria are applied. The lack of FDA breakpoints for several non-glucose fermenters with a low MIC90 of cefiderocol (e.g., A. xylosoxidans, B. cepacia complex, and S. maltophilia) further contributes to the particularly low overall percentages of susceptible isolates when FDA cefiderocol breakpoints are applied, compared to CLSI or EUCAST breakpoints.

Both DD approaches had variable CA for CRE, ranging from 84% to 91%, across the three sets of interpretative criterion recommendations. Categorical agreement was more limited for the non-glucose-fermenting organisms, ranging from 36% to 90%, across the three sets of criteria, with reduced agreement being largely attributable to A. baumannii complex isolates. Results of both DD methods had a high degree of correlation with each other; however, variability with A. baumannii was observed.

For MASTDISCS, EUCAST breakpoints resulted in the highest CA. However, due to the lack of an intermediate category (or “area of technical uncertainty” category, as defined by EUCAST), higher rates of ME and VME were observed. On the other hand, HardyDisks performed best and met the acceptance criteria when results for the Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa were interpreted with the investigational CLSI breakpoints. FDA breakpoints resulted in the lowest CA, which was driven by a high number of minor errors. Although it is recommended that laboratories apply FDA breakpoints to the FDA-cleared HardyDisks, they should proceed with caution, especially when testing MDR GNB. For the Enterobacterales, HardyDisks yielded more susceptible results than BMD, and zone diameter results within 19 to 22 mm would benefit from confirmation by BMD. For P. aeruginosa, the FDA disk correlates were more variable and did not consistently test one way or another (i.e., more susceptible or resistant) but resulted in a low CA of 36% with 64% mE. These errors occurred with zone diameters between 20 and 24 mm, which would also benefit from confirmation of results by BMD.

CLSI set investigational breakpoints (i.e., research use only) prior to the availability of clinical trial outcome data, whereas data from the complicated urinary tract infection trial (NCT02321800) were available when the FDA breakpoints were set, and this accounts for the difference in breakpoints (15). Both the FDA and CLSI plan to revisit or have revisited the cefiderocol breakpoints as they analyze results from two recent cefiderocol clinical trials (NCT02714595 and NCT03032380). Laboratories should be aware of potential challenges when verifying cefiderocol HardyDisks with FDA breakpoints using the breakpoints published prior to 28 September 2020 (outlined in Table 1). The FDA updated the cefiderocol breakpoints on 28 September 2020; laboratories should be aware of this update as revalidation of AST devices may be required prior to applying the updated breakpoints for patient care.

A consistent finding across both BMD and DD methods is the limited reliability of cefiderocol AST results for A. baumannii. Accurate cefiderocol MICs are confounded by the observation of trailing endpoints with BMD. Trailing endpoints are the phenomenon of observing multiple wells with faint growth relative to the growth control. We identified trailing endpoints with 21% of A. baumannii isolates. Indeed, multiple assays have demonstrated issues with reliable phenotypic testing for A. baumannii, such as the colistin broth disk elution method and the modified carbapenem inactivation method (19–22). DD also posed issues with providing reliable A. baumannii complex results. A. baumannii isolates frequently had pinpoint colonies within inner zones, making zone diameter measurements difficult. Although, admittedly, both methods have their limitations for A. baumannii, as BMD remains the reference standard for MIC testing, we recommend that cefiderocol AST against A. baumannii complex be done by using BMD rather than DD methods.

This study included a relatively small number of isolates, particularly for any individual species. Further, isolates were derived from a single region, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other regions with differences in the composition of common Gram-negative resistance mechanisms. Our results need to be verified in a larger study that includes geographically diverse isolates. Last, lyophilized BMD panels that have demonstrated equivalency to reference BMD were used as the comparator. These limitations notwithstanding, as cefiderocol is not currently included in any commercial automated AST panel and gradient diffusion methods are also not available, our results indicate that DD offers a convenient, alternative approach to BMD methods for cefiderocol AST. However, caution must be used when results based on the bacterial species and the BP applied are interpreted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

BMD panels were provided as part of a larger Shionogi-sponsored study. IHMA provided the MASTDISCS for this study.

Patricia J. Simner served as an advisory board member as part of a microbiology panel for Shionogi, Inc. Patricia J. Simner reports grants and personal fees from Accelerate Diagnostics, OpGen, Inc., and BD Diagnostics; grants from bioMérieux, Inc., Affinity Biosensors, and Hardy Diagnostics; and personal fees from Roche Diagnostics, outside the submitted work. Patricia J. Simner receives travel reimbursement from ASM, CAP, and CLSI.

Footnotes

For companion articles on this topic, see https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00966-20 and https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00951-20.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burnham JP, Olsen MA, Kollef MH. 2019. Re-estimating annual deaths due to multidrug-resistant organism infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 40:112–113. doi: 10.1017/ice.2018.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitout JD, Nordmann P, Poirel L. 2015. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, a key pathogen set for global nosocomial dominance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:5873–5884. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01019-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tamma PD, Simner PJ. 2018. Phenotypic detection of carbapenemase-producing organisms from clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol 56:e01140-18. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01140-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clegg WJ, Pacilli M, Kemble SK, Kerins JL, Hassaballa A, Kallen AJ, Walters MS, Halpin AL, Stanton RA, Boyd S, Gable P, Daniels J, Lin MY, Hayden MK, Lolans K, Burdsall DP, Lavin MA, Black SR. 2018. Notes from the field: Large cluster of Verona integron-encoded metallo-beta-lactamase-producing carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates colonizing residents at a skilled nursing facility—Chicago, Illinois, November 2016–March 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67:1130–1131. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6740a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walters MS, Grass JE, Bulens SN, Hancock EB, Phipps EC, Muleta D, Mounsey J, Kainer MA, Concannon C, Dumyati G, Bower C, Jacob J, Cassidy PM, Beldavs Z, Culbreath K, Phillips WE Jr, Hardy DJ, Vargas RL, Oethinger M, Ansari U, Stanton R, Albrecht V, Halpin AL, Karlsson M, Rasheed JK, Kallen A. 2019. Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa at US Emerging Infections Program sites, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis 25:1281–1288. doi: 10.3201/eid2507.181200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gniadek TJ, Carroll KC, Simner PJ. 2016. Carbapenem-resistant non-glucose-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli: the missing piece to the puzzle. J Clin Microbiol 54:1700–1710. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03264-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Somboro AM, Osei Sekyere J, Amoako DG, Essack SY, Bester LA. 2018. Diversity and proliferation of metallo-beta-lactamases: a clarion call for clinically effective metallo-beta-lactamase inhibitors. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e00698-18. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00698-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhanel GG, Golden AR, Zelenitsky S, Wiebe K, Lawrence CK, Adam HJ, Idowu T, Domalaon R, Schweizer F, Zhanel MA, Lagace-Wiens PRS, Walkty AJ, Noreddin A, Lynch Iii JP, Karlowsky JA. 2019. Cefiderocol: a siderophore cephalosporin with activity against carbapenem-resistant and multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli. Drugs 79:271–289. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-1055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page MGP. 2019. The role of iron and siderophores in infection, and the development of siderophore antibiotics. Clin Infect Dis 69:S529–S537. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamano Y. 2019. In vitro activity of cefiderocol against a broad range of clinically important Gram-negative bacteria. Clin Infect Dis 69:S544–S551. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Critchley IA, Basker MJ. 1988. Conventional laboratory agar media provide an iron‐limited environment for bacterial growth. FEMS Microbiology Lett 50:35–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1988.tb02907.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2020. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Thirtieth Informational Supplement. M100-S30. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 13.EUCAST. 2020. Breakpoints for cefiderocol from EUCAST. https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/Addenda/Cefiderocol_addendum_20200501.pdf.

- 14.Lewis TS, Holliday NM, Knapp CC, Kilian SB, Olson BJ, Pike CL, Donnnerbauer EK, Mehta NP, Fritsche TR, Gattis A, Waugh N, Doing K, Vlooswijk J, Cornelisse A, Scopes E, Williams J, Leonte A-M, Shono K. 2019. A multi-site study comparing a commercially prepared dried MIC susceptibility system to the CLSI/ISO broth microdiluion method for defiderocol using Gram-negative non-fastidious organisms, abstr AAR-761. ASM Microbe 2019, San Francisco, CA. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simner PJ, Patel R. 2021. Cefiderocol antimicrobial susceptibility testing considerations: the Achilles’ heel of the Trojan horse? J Clin Microbiol 59:e00951-20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00951-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Humphries RM, Ambler J, Mitchell SL, Castanheira M, Dingle T, Hindler JA, Koeth L, Sei K, Hardy D, Zimmer B, Butler-Wu S, Dien Bard J, Brasso B, Shawar R, Dingle T, Humphries R, Sei K, Koeth L, Standardization Working Group of the Subcommittee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 2018. CLSI Methods Development and Standardization Working Group best practices for evaluation of antimicrobial susceptibility tests. J Clin Microbiol 56:e01934-17. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01934-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kazmierczak KM, Tsuji M, Wise MG, Hackel M, Yamano Y, Echols R, Sahm DF. 2019. In vitro activity of cefiderocol, a siderophore cephalosporin, against a recent collection of clinically relevant carbapenem-non-susceptible Gram-negative bacilli, including serine carbapenemase- and metallo-beta-lactamase-producing isolates (SIDERO-WT-2014 Study). Int J Antimicrob Agents 53:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shionogi, Inc. 2019. Cefiderocol FDA briefing document. https://www.fda.gov/media/131703/download.

- 19.Humphries RM, Green DA, Schuetz AN, Bergman Y, Lewis S, Yee R, Stump S, Lopez M, Macesic N, Uhlemann AC, Kohner P, Cole N, Simner PJ. 2019. Multicenter evaluation of colistin broth disk elution and colistin agar test: a report from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. J Clin Microbiol 57:e01269-19. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01269-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albano M, Karan MJ, Schuetz AN, Patel R. 2021. Comparison of agar dilution to broth microdilution for testing in vitro activity of cefiderocol against Gram-negative bacilli. J Clin Microbiol 59:e00966-20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00966-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simner PJ, Bergman Y, Trejo M, Roberts AA, Marayan R, Tekle T, Campeau S, Kazmi AQ, Bell DT, Lewis S, Tamma PD, Humphries R, Hindler JA. 2018. Two-site evaluation of the colistin broth disk elution test todDetermine colistin in vitro activity against Gram-negative bacilli. J Clin Microbiol 57:e01163-18. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01163-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simner PJ, Johnson JK, Brasso WB, Anderson K, Lonsway DR, Pierce VM, Bobenchik AM, Lockett ZC, Charnot-Katsikas A, Westblade LF, Yoo BB, Jenkins SG, Limbago BM, Das S, Roe-Carpenter DE. 2017. Multicenter evaluation of the modified carbapenem inactivation method and the Carba NP for detection of carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii. J Clin Microbiol 56:e01369-17. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01369-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]