Abstract

Background:

Chagas disease (CD), caused by Trypanosoma cruzi, has been increasingly encountered as a cause of cardiovascular disease in the United States. We aimed to examine trends of hospital admissions and cardiovascular outcomes of cardiac CD (CCD).

Methods:

Search of 2003-2011 Nationwide Inpatient Sample database identified 949 (age 57±16 years, 51% male, 72.5% Hispanic) admissions for CCD.

Results:

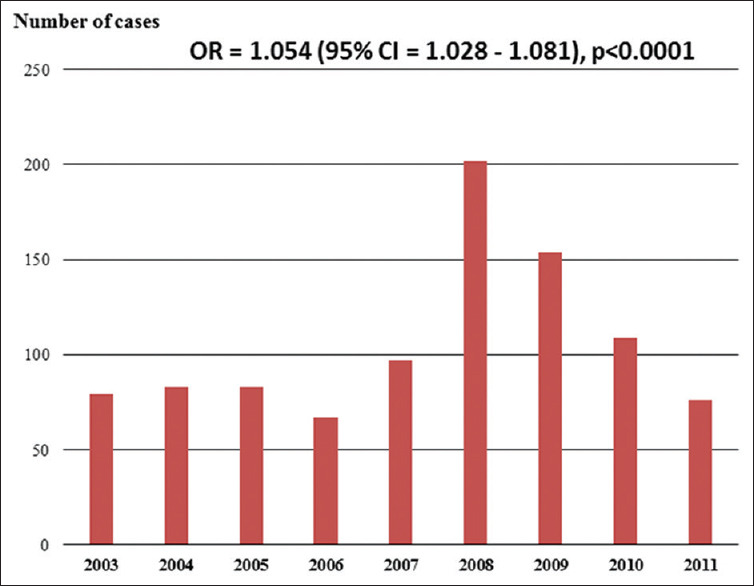

A significant increase in the number of admissions for CCD was noted during the study period (OR=1.054; 95% CI=1.028-1.081; P< 0.0001); 72% were admitted to Southern and Western hospitals. Comorbidities included hypertension (40%), coronary artery disease (28%), hyperlipidemia (26%), tobacco use (12%), diabetes (9%), heart failure (5%) and obesity (2.2%). Cardiac abnormalities noted during hospitalization included atrial fibrillation (27%), ventricular tachycardia (23%), sinoatrial node dysfunction (5%), complete heart block (4%), valvular heart disease (6%)] and left ventricular aneurysms (5%). In-hospital mortality was 3.2%. Other major adverse events included cardiogenic shock in 54 (5.7%), cardiac arrest in 30 (3.2%), acute heart failure in 88 (9.3%), use of mechanical circulatory support in 29 (3.1%), and acute stroke in 34 (3.5%). Overall, 63% suffered at least one adverse event. Temporary (2%) and permanent (3.5%) pacemakers, implantable cardioverter defibrillators (10%), and cardiac transplant (2.1%) were needed for in-hospital management.

Conclusions:

Despite the remaining concerns about lack of awareness of CCD in the US, an increasing number of hospital admissions were reported from 2003-2011. Serious cardiovascular abnormalities were highly prevalent in these patients and were frequently associated with fatal and nonfatal complications.

Key Words: Chagas cardiomyopathy, Chagas heart disease, outcomes, Trypanosoma cruzi

INTRODUCTION

Chagas disease (CD) is a parasitic disease caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi. Transmission occurs most often through an insect vector called the triatomine bug. Inoculation of a bite wound by fecal material from the bug containing the protozoan parasite will then initiate the infection. CD is the most burdensome parasitic disease in the “Region of the Americas” according to the 2015 World Health Organization Global Health Estimates.[1] While historically this was a disease confined to endemic areas of rural Latin America, as international migration increased, the epidemiology of this disease has been changing.[2] Estimating the true burden of CD in the United States (US) is challenging, but one calculation suggested that there are approximately 300,167 individuals with the asymptomatic indeterminate form in this country.[3] Based on this, a conservative estimate of those individuals who have progressed to chronic cardiac CD (CCD) and are currently living in the US is 30,000–45,000.[4] This estimate was calculated using immigration data combined with native country seroprevalence and represents a substantial disease burden. With an ongoing upward trend in international migration, it is likely that the prevalence of CD in the US would be rising.[2] A recent study has estimated the number of affected individuals in the US at 238,091, based on data from the Foreign-Born Hispanic population and the American Community Survey.[5] There is a paucity of epidemiological data regarding CD in the US, and there is also likely a lack of awareness of this disease relative to its increasing burden.[6,7] By searching a Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database, we were able to identify all hospitalizations related to CCD within the study period. From this, we aimed to provide temporal admission trends as well as epidemiological and outcomes data including patients' demographics, geographical trends, as well as adverse events and interventions during hospitalization.

METHODS

Data source

Data were obtained from the NIS database, a part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, for the calendar years 2003 through 2011. The database contains discharge-level data for ~ 8 million hospital stays from ~ 1000 hospitals each year. It is designed to approximate a 20% stratified sample of community hospitals. A total of 46 states, representing ~ 96% of the US population, participate in NIS. Hospital ownership, patient volume, teaching status, urban or rural location, and geographic region are used for stratified sampling, and discharge weights provided by the sponsor are used to obtain national estimates. The database is publicly available and contains de-identified information, and therefore, the study was deemed exempt from institutional research board review. A complete description of the methods can be found in previous publications.[8,9,10]

Study population

All hospitalizations with a principal diagnosis ( first or second diagnosis) of CCD were included in the study. This was done using an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification code 086.0. The study sample included a total of 949 patients. Patient and hospital characteristics along with outcome parameters were extracted.

Patient and hospital characteristics

Baseline demographic and clinical features studied included both patient-level and hospital-level characteristics. Patient-level characteristics included demographics, primary payer, income quartile, all comorbidity measures for use with administrative data, other cardiovascular comorbidities (tobacco smoking, obesity, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and known heart disease), and psychosocial information. Hospital-level characteristics included hospital location (urban or rural), hospital bed size (small, medium, or large), hospital region (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West), and teaching versus nonteaching status.

Outcome measures

The outcome measures evaluated were inhospital mortality, cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest, acute systolic or diastolic congestive heart failure, intra-aortic balloon pump use, cardioverter-defibrillator implantation, discharge to a facility other than home, length of stay, cost of hospitalization, and major adverse cardiovascular events. The latter was defined as inhospital mortality, length of hospital stay exceeding 4 days, acute heart failure, cardiogenic shock, and discharge to a facility other than home.

Statistical analysis

Weighted data were used for all statistical analyses. Results were expressed as numbers (%) for categorical variables and mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables. Differences between groups were analyzed with the use of the Student's t-test for continuous variables and the Chi-square test for categorical variables, respectively. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to report the trend for annual rate of hospital admission for CCD. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA).

RESULTS

Patient population

The demographic and baseline clinical and psychosocial characteristics of 949 patients with CD admitted to hospital between 2003 and 2011 are listed in Table 1. The mean age of the 949 patients admitted with CD was 57 ± 16 years, 51% were male, and the majority (73%) were Hispanic. Among cardiovascular risk factors, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and established coronary disease were the most prevalent. Heart failure (primarily with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction) was present historically in 5.1%. Selected psychosocial, neurologic, systemic, and organ system-specific historical information is also listed in Table 1. As shown in Figure 1, a significant increase in the number of admissions for CCD was noted during the study period (OR = 1.054; 95% CI = 1.028–1.081; P < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and psychosocial characteristics of patients admitted with cardiac Chagas disease

| Variable | Mean±SD or (%) (n=949) |

|---|---|

| Demographic information | |

| Age (years) | 57±16 |

| Male | 51 |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 16.9 |

| Black | 2.6 |

| Hispanic | 72.5 |

| Asian | 0.6 |

| Native American | 0 |

| Other | 7.5 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors and diseases | |

| Hypertension | 40 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 26 |

| Smoking | 12 |

| Obesity | 2 |

| Morbid obesity | 0.6 |

| Coronary artery disease | 28 |

| Heart failure | 5.1 |

| Reduced ejection fraction | 4.6 |

| Preserved ejection fraction | 0.5 |

| Psychosocial factors | |

| Depression | 10.7 |

| Psychosis | 1.7 |

| Anxiety disorder | 2.6 |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 3.2 |

| Cocaine abuse or dependence | 0.9 |

| Amphetamine abuse or dependence | 0.6 |

| Neurologic conditions | |

| Migraine headache | 1.2 |

| Transient ischemic attack/stroke | 4.7 |

| Seizure | 3 |

| Systemic and other organ system conditions | |

| Sepsis | 4.9 |

| Hypothyroidism | 13.6 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 1 |

| Liver disease | 2.2 |

| Renal failure | 12.2 |

| Fluid and electrolytes abnormalities | 19.8 |

| Acute or chronic venous thromboembolism | 3.7 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 2.5 |

| Collagen vascular disease | 1.2 |

| Deficiency anemia | 14.7 |

| Blood loss anemia | 1 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 5.3 |

| Coagulopathy | 4 |

| Pulmonary circulation disease | 3.2 |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 2 |

| Metastatic disease | 0.5 |

| Lymphoma | 0.6 |

SD: Standard deviation

Figure 1.

Bar graph showing the number of cases of cardiac Chagas disease admitted to the United States hospitals between 2003 and 2011

Insurance, hospital, and cost characteristics

Majority (56%) of the patients admitted with CCD had insurance coverage by Medicare or Medicaid, whereas 19% had private insurance and 12% were self-pay. Income was evenly distributed among quartiles. Overall, 72% of the patients were admitted to hospitals in Southern or Western states, followed by the Northeastern (21%) and Midwestern (7%) states. Nearly 92% of admissions were classified as emergent or urgent rather than elective and one-fourth occurred during weekend days. Large teaching hospitals admitted most of the patients with CCD. The length of stay was 5 ± 16 days at a mean hospital cost of $31,586 ± 97,903.

Electrocardiographic abnormalities

Certain electrocardiographic (ECG) abnormalities in patients admitted with CCD are listed in Table 2. Importantly, 27% of the patients were in atrial fibrillation and 23% had ventricular tachycardia. Evidence of sinus node dysfunction was present in 5% and complete heart block was noted in 4%.

Table 2.

Electrocardiographic abnormalities among patients admitted with cardiac Chagas disease

| Variable | Percent (n=949) |

|---|---|

| Electrocardiographic abnormalities | |

| Atrioventricular block | |

| First degree | 1.4 |

| Second degree | |

| Type 1 | 1 |

| Type 2 | 0 |

| Complete | 4 |

| Sinoatrial node dysfunction | 5.1 |

| Block branch block | |

| Right | 2.6 |

| Right+left anterior fascicle | 1.4 |

| Right+left posterior fascicle | 0.5 |

| Left | 3 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 26.9 |

| Atrial flutter | 1.4 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 22.7 |

| Premature ventricular contractions | 3.1 |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 1.5 |

Adverse events during hospitalization

Overall, any major adverse event, defined as inhospital mortality, length of hospital stay >4 days, acute heart failure, cardiogenic shock, or discharge to a facility other than home, occurred in 63% of the patients. Majority of these complications were cardiovascular in nature that occurred in 46% of the entire cohort. The latter included rhythm abnormalities (atrial fibrillation in 27% and ventricular tachycardia in 23%), acute heart failure (9%), cardiogenic shock (6%), and cerebrovascular ischemia (8%). In general, 1 in 8 patients admitted with CCD was discharged to a facility other than home following an average hospital stay of 5 days [Table 3].

Table 3.

Adverse events and interventions during hospitalization among patients admitted with cardiac Chagas disease

| Variable | Percent (n=949) |

|---|---|

| Adverse events during hospitalization | |

| Any major adverse event | 63* |

| Any cardiac complication | 46 |

| Mortality | 3.2 |

| Cardiac arrest | 3.2 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 26.9 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 22.7 |

| Acute heart failure | 9.3 |

| Reduced ejection fraction | 8.3 |

| Preserved ejection fraction | 1 |

| Valvular heart disease | 6 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 5.7 |

| Left ventricular aneurysm | 5 |

| Acute cerebrovascular accident | |

| Stroke | 3.5 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 4.7 |

| Acute pulmonary embolism | 1.6 |

| Cardiac tamponade | 0.5 |

| Discharge to facility other than home | 13.1 |

| Interventions during hospitalization | |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator | 10 |

| Electronic pacemaker | |

| Temporary | 2 |

| Permanent | 3.5 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 2 |

| Other mechanical circulatory support | 1.1 |

| Cardiac transplant | 2.1 |

*Defined as inhospital mortality, length of hospital stay exceeding 4 days, acute heart failure, cardiogenic shock, and discharge to a facility other than home

Interventions during hospital stay

Permanent electronic pacemakers were inserted in 3.5% of the patients and 10% required an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Mechanical circulatory support was needed in 3.1% and cardiac transplant was performed in 2.1% of the patients [Table 3].

DISCUSSION

Major findings

The present study indicates that an increasing number of patients with CCD are being admitted to hospitals in the US. A large majority of such patients were admitted to hospitals located in the Southern and Western states, possibly reflecting the pattern of settlement of immigrants from endemic areas. The age of patients in this cohort was 57 years, and there was a relatively high prevalence of cardiac risk factors and comorbid conditions such as hypertension (40%), coronary artery disease (28%), hyperlipidemia (26%), and tobacco use (12%). There was a particularly high prevalence of atrial fibrillation (27%) and ventricular tachycardia (23%) in these individuals, and adverse events were frequently (63%) observed during hospitalization. The latter included cardiogenic shock (5.7%), cardiac arrest (3.2%), acute heart failure (9.3%), and acute stroke (3.5%). Permanent electronic pacemakers (3.5%), implantable cardioverter defibrillators (10%), and mechanical circulatory support devices (3.1%) were needed by some patients, and 2.1% underwent cardiac transplant surgery. Inhospital mortality was 3.2%.

Chagas heart disease

Worldwide, CD affects nearly 6–7 million individuals mainly in endemic regions of Latin America at a substantial economic burden.[1,11,12] In recent years, migration from these endemic regions has resulted in appearance of the disease in the US and other formerly unaffected areas.[2,3,4,5,13,14] It is estimated that over 300,000 individuals living in the US have been infected by T. cruzi[3] and that 30,000–45,000 of them suffer its cardiac consequences.[4] It is likely that the burden of CCD in this country would increase with the upward trend in international migration.[2] An important concern regarding CD is that awareness of the disease is quite low among US physicians,[7] and thus, the number of admissions for CCD, as presented in this report, is likely a gross underestimation of the true burden of the disease.

Comparison with a Brazilian cohort

Despite the increasing number of chronic cases of CD appearing in this country, there has been no large-scale report of the characteristics of such patients. Since CD is not commonly an indigenous disease in the US, it is likely that the epidemiology and clinical characteristics of the disease differ from those in endemic areas. We have compared the findings of the present study with those of a relatively large cohort of patients with CCD from Brazil [Table 4].[15] As shown, the average age of the US cohort is about 10 years older, and they more often have atrial fibrillation or flutter despite much lower incidence of palpitation as a symptom. It can be postulated that some of these differences are related to the absence of reinfection in those who have migrated to nonendemic regions.[16] ECG abnormalities, cardiomegaly, and ventricular apical aneurysm were all reported more frequently in the Brazilian cohort. Other studies have also reported a relatively low prevalence of ECG abnormalities among CD patients in nonendemic areas[17] compared to endemic regions.[18] The prevalence of ECG abnormalities also differs among treated and untreated patients with CCD.[19] Overall, it appears that ECG may be a useful screening tool in endemic regions but not in nonendemic regions.[20]

Table 4.

Comparison of the present cohort of patients with cardiac Chagas disease with a regional cohort in Brazil

| Variable | Present cohort (n=949) | Brazilian cohort[15] (n=424) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusive years | 2003–2011 | 1986–1991 | |

| Demographic information and symptoms | |||

| Age (years) | 57±15.7 | 47±11 | - |

| Male (%) | 51.1 | 58.3 | 0.014 |

| Palpitations (%) | 1 | 29.7 | <0.001 |

| Syncope (%) | 1.4 | 6.4 | <0.001 |

| Electrocardiographic abnormalities | |||

| First- and second-degree atrioventricular block | 2.4% | 9% | <0.001 |

| Conduction abnormality | |||

| Right bundle branch block (%) | 2.6 | 18.6 | <0.001 |

| Left anterior fascicular block (%) | 13.2 | ||

| Left anterior fascicular block+right bundle branch block (%) | 1.4 | 24.3 | <0.001 |

| Left bundle branch block (%) | 3 | 7.1 | 0.0004 |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter (%) | 28.3 | 3.1 | <0.001 |

| Premature ventricular contractions (%) | 3.1 | 37.3 | <0.001 |

| Ventricular tachycardia (%) | 22.7 | 48.3 | <0.05 |

| Cardiac structural abnormalities | |||

| Ventricular aneurysm (%) | 4.7 | 10.5 | 0.004 |

| Cardiomegaly (%) | 0.5 | 26.9 | <0.001 |

Clinical implications

The pathogenesis of chronic CCD has been gradually unraveling in recent years.[21,22] Among various potentially contributing factors, infection-initiated immune response (myocarditis) and coronary microvascular abnormalities (myocyte apoptosis and necrosis) appear to play major roles in the development of CCD.[23,24,25,26,27] Cardiac involvement in CD evolves from the initial acute myocarditis through a quiescent intermediate form and finally to chronic CCD characterized by conduction abnormalities, sinus node dysfunction, arrhythmias, left ventricular apical aneurysm and thromboembolic events. Sudden death is a relatively common mode of death in patients with CCD and has not been well studied in affected individuals in the US.[28] Such individuals are likely to not be fully represented in the NIS data. The current evidence, as presented in this report, calls for improved systematic surveillance for early recognition of the disease and better understanding of the scope of CD in this country. Finally, strategies to improve awareness of the existence of CD in the US are needed among health-care professionals.

Limitations

This is a retrospective study and thus subject to limitations incurred in uncontrolled design. The data are, however, derived from a large, nationally representative database and thus provide real-life information of epidemiological significance. It is important to bear in mind that the accuracy of the data may have been influenced by the coding practices of individual hospitals. Furthermore, information contained in this sample is administrative in nature and that each admission is considered one individual. It is thus likely that multiple admissions have occurred for some individuals during the study period. Finally, the data did not contain important prognostic information including several components of a commonly used risk score.[15] Despite these limitations, the data represent a unique report on the scope of CCD in the US in recent years.

CONCLUSION

CCD represents a growing etiology of chronic heart disease with significant morbidity and mortality. The general characteristics of the affected individuals may be significantly different in endemic and nonendemic regions. The effective diagnosis of CCD thus requires familiarity with the unique pathophysiologic features and phenotypic expression of the disease. The current sample of patients with CCD in the US indicates that serious cardiovascular abnormalities are highly prevalent in these patients and are frequently associated with fatal and nonfatal complications.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Research quality and ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board / Ethics Committee. The authors followed applicable EQUATOR Network (http://www.equator-network.org/) guidelines during the conduct of this research project.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO Estimates for 2000-2015. [Last accessed on 2019 Jun 21]. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates/en/

- 2.Rassi A, Rassi A, Marin-Neto JA. Chagas disease. Lancet Lond Engl. 2010;375:1388–402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanaway JD, Roth G. The burden of Chagas disease: Estimates and challenges. Glob Heart. 2015;10:139–44. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bern C, Montgomery SP. An estimate of the burden of Chagas disease in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:e52–4. doi: 10.1086/605091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manne-Goehler J, Umeh CA, Montgomery SP, Wirtz VJ. Estimating the Burden of Chagas Disease in the United States. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0005033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bern C. Chagas' disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:456–466. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1410150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stimpert KK, Montgomery SP. Physician awareness of Chagas disease, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:871–2. doi: 10.3201/eid1605.091440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatia N, Agrawal S, Garg A, Mohananey D, Sharma A, Agarwal M, et al. Trends and outcomes of infective endocarditis in patients on dialysis. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40:423–9. doi: 10.1002/clc.22688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agrawal S, Garg L, Garg A, Mohananey D, Jain A, Manda Y, et al. Recent trends in management and inhospital outcomes of acute myocardial infarction in renal transplant recipients. Am J Cardiol. 2017;119:542–52. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agrawal S, Garg L, Sharma A, Mohananey D, Bhatia N, Singh A, et al. Comparison of inhospital mortality and frequency of coronary angiography on weekend versus weekday admissions in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118:632–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abuhab A, Trindade E, Aulicino GB, Fujii S, Bocchi EA, Bacal F. Chagas' cardiomyopathy: The economic burden of an expensive and neglected disease. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2375–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee BY, Bacon KM, Bottazzi ME, Hotez PJ. Global economic burden of Chagas disease: A computational simulation model. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:342–8. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nunes MC, Dones W, Morillo CA, Encina JJ, Ribeiro AL. Council on Chagas Disease of the Interamerican Society of Cardiology. Chagas disease: An overview of clinical and epidemiological aspects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:767–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pérez-Molina JA, Norman F, López-Vélez R. Chagas disease in non-endemic countries: Epidemiology, clinical presentation and treatment. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2012;14:263–74. doi: 10.1007/s11908-012-0259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rassi A, Jr, Rassi A, Little WC, Xavier SS, Rassi SG, Rassi AG, et al. Development and validation of a risk score for predicting death in Chagas' heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:799–808. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prata A. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of Chagas disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1:92–100. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sánchez-Montalvá A, Salvador F, Rodríguez-Palomares J, Sulleiro E, Sao-Avilés A, Roure S, et al. Chagas cardiomyopathy: Usefulness of EKG and echocardiogram in a non-endemic country. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157597. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rojas LZ, Glisic M, Pletsch-Borba L, Echeverría LE, Bramer WM, Bano A, et al. Electrocardiographic abnormalities in Chagas disease in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soverow J, Hernandez S, Sanchez D, Forsyth C, Flores CA, Viana G, et al. Progression of baseline electrocardiogram abnormalities in chagas patients undergoing antitrypanosomal treatment. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6:ofz012. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandez AB, Nunes MC, Clark EH, Samuels A, Menacho S, Gomez J, et al. Electrocardiographic and echocardiographic abnormalities in Chagas disease: Findings in residents of rural Bolivian communities hyperendemic for Chagas disease. Glob Heart. 2015;10:159–66. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanowitz HB, Machado FS, Jelicks LA, Shirani J, de Carvalho AC, Spray DC, et al. Perspectives on Trypanosoma cruzi-induced heart disease (Chagas disease) Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;51:524–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Machado FS, Jelicks LA, Kirchhoff LV, Shirani J, Nagajyothi F, Mukherjee S, et al. Chagas heart disease: Report on recent developments. Cardiol Rev. 2012;20:53–65. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e31823efde2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jelicks LA, Chandra M, Shirani J, Shtutin V, Tang B, Christ GJ, et al. Cardioprotective effects of phosphoramidon on myocardial structure and function in murine Chagas' disease. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:1497–506. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chandra M, Tanowitz HB, Petkova SB, Huang H, Weiss LM, Wittner M, et al. Significance of inducible nitric oxide synthase in acute myocarditis caused by Trypanosoma cruzi (Tulahuen strain) Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:897–905. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanowitz HB, Huang H, Jelicks LA, Chandra M, Loredo ML, Weiss LM, et al. Role of endothelin 1 in the pathogenesis of chronic chagasic heart disease. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2496–503. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2496-2503.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandra M, Shirani J, Shtutin V, Weiss LM, Factor SM, Petkova SB, et al. Cardioprotective effects of verapamil on myocardial structure and function in a murine model of chronic Trypanosoma cruzi infection (Brazil Strain): An echocardiographic study. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:207–15. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00320-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Souza AP, Tanowitz HB, Chandra M, Shtutin V, Weiss LM, Morris SA, et al. Effects of early and late verapamil administration on the development of cardiomyopathy in experimental chronic Trypanosoma cruzi (Brazil strain) infection. Parasitol Res. 2004;92:496–501. doi: 10.1007/s00436-004-1080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sternick EB, Martinelli M, Sampaio R, Gerken LM, Teixeira RA, Scarpelli R, et al. Sudden cardiac death in patients with chagas heart disease and preserved left ventricular function. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:113–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]