Abstract

Objective:

Restoring cardiopulmonary circulation with effective chest compression remains the cornerstone of resuscitation, yet real-time compressions may be suboptimal. This project aims to determine whether in patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA; population), chest compressions performed with free-standing audiovisual feedback (AVF) device as compared to standard manual chest compression (comparison) results in improved outcomes, including the sustained return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), and survival to the intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital discharge (outcomes).

Methods:

Scholarly databases and relevant bibliographies were searched, as were clinical trial registries and relevant conference proceedings to limit publication bias. Studies were not limited by date, language, or publication status. Clinical randomized controlled trials (RCT) were included that enrolled adults (age ≥ 18 years) with IHCA and assessed real-time chest compressions delivered with either the standard manual technique or with AVF from a freestanding device not linked to an automated external defibrillator (AED) or automated compressor.

Results:

Four clinical trials met inclusion criteria and were included. No ongoing trials were identified. One RCT assessed the Ambu CardioPump (Ambu Inc., Columbia, MD, USA), whereas three assessed Cardio First Angel™ (Inotech, Nubberg, Germany). No clinical RCTs compared AVF devices head-to-head. Three RCTs were multi-center. Sustained ROSC (4 studies, n = 1064) was improved with AVF use (Relative risk [RR] 1.68, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.39–2.04), as was survival to hospital discharge (2 studies, n = 922; RR 1.78, 95% CI 1.54–2.06) and survival to hospital discharge (3 studies, n = 984; RR 1.91, 95% CI 1.62–2.25).

Conclusion:

The moderate-quality evidence suggests that chest compressions performed using a non-AED free-standing AVF device during resuscitation for IHCA improves sustained ROSC and survival to ICU and hospital discharge.

Trial Registration:

PROSPERO (CRD42020157536).

Key Words: Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, chest compression, feedback, in-hospital cardiac arrest, medical device

INTRODUCTION

In-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) is common and carries high morbidity and mortality. Data from the American Heart Association's (AHA) Get with the Guidelines-Resuscitation registry indicates that between 2008 and 2017, the U. S. annual incidence of IHCA was 292,000, or roughly 1/100 admissions.[1] The primary causes are cardiac (50%–60%), including myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, and heart failure.[2] Respiratory failure results in roughly 40% of cases and increases in frequency with longer hospital stays.[2] IHCA outcomes vary significantly globally, with return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) rates ranging from 20% to 73%,[3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] and North American and European rates ranging 43%–73%.[8,9,10,11,12,27] Survival to hospital discharge ranges from 1% to 42% globally,[4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,28,29] with North American and European rates ranging from 15% to 30%.[8,9,10,11,12,27] Furthermore, while outcomes have been improved over recent decades, 1-year survival rates remain low (13%), with favorable neurological outcomes reported in 20% to 85% of cases.[1]

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) with effective chest compression remains the cornerstone of resuscitation.[3,30,31,32,33,34,35] International guidelines note the critical importance of compression components, including position, rate, force, depth, interruptions, recoil, excessive ventilation avoidance, no-flow time, and flow fraction.[3,33,34,35,36] Despite this, increasing evidence suggests that compressions administered in real-time may be suboptimal.[37,38] Some have proposed that real-time audiovisual feedback (AVF) may aid resuscitation efforts by improving the quality of delivered chest compressions,[33,39,40,41] and both the AHA and the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) have made cautious recommendations supporting their use.[27,33,35]

Several AVF devices have been developed and marketed. Some are free-standing, whereas others are linked to automated external defibrillators (AED) or other monitoring equipment. The devices are generally applied between the victim's chest and the rescuer's hands. The reliant technology ranges in complexity from a metronome to tensile springs, accelerometers, pressure sensors, and triaxial magnetic sensing [Table 1].[3,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51] Feedback may be given in audio, visual, or tactile format. Stand-alone AVF devices provide benefits in cost and simplicity, making them potentially useful for applications both in-and outside of hospital settings. Despite an abundance of non-randomized and simulation studies [Tables 2 and 342,44,45,48,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72] data from clinical randomized controlled trials (RCT) are sparse [Table 4].[3,51,73,74] To date, there have been no < 15 non-AED compression AVF devices have been released to market [Table 1]. The bulk of available evidence is from non-randomized or crossover studies of simulated resuscitations. Seven devices [20 studies; Tables 2 and 3] have published RCT data from simulated resuscitations, none have published non-randomized clinical studies, and only two have available clinical RCT data [4 studies; Table 43,51,73,74] The results of the simulation RCTs suggest that free-standing non-AED AVF devices are associated with: (1) no improvement in correct hand position (1 of 1 study); (2) improved compression rate (12 of 15 studies; 3 no change); (3) improved compression depth (12 of 16 studies; 3 no change; 1 worse); (4) possibly improved compression release/chest recoil (4 of 7 studies; 3 no change); (5) unchanged no-flow fraction (1 of 1 study); (6) improved number inefficient compressions (2 of 2 studies); and (7) improved number of correct/error free compressions (7 of 7 studies). Moreover, there are at least five free-standing AVF devices marketed without any published studies, including Beaty (Medical Feedback Technologies Ltd.), CPR-1100 (Nihon Kohden), PrestoPatch™ (Nexus Control Systems LLC.), PrestoPush™ (Nexus Control Systems LLC.), and ПP -01 (PR-01; FactorMed Technika).

Table 1.

Description of hand-held compression feedback devices that are not linked to an automated external defibrillator or external device

| Device | Manufacturer (city, country) | Commercial availability | Reliant technology | Power Source | Feedback type | Feedback method | Measurement items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambu CardioPump | Ambu Inc. (Columbia, MD, USA) | Available | Tensile springs | Mechanical | Auditory Visual |

Metronome Visual scale |

Compression depth Compression rate Recoil |

| Beaty | Medical Feedback Technologies ltd. (Even Yehuda, Israel) | Available | Accelerometer | Battery | Auditory | Audio tone | Adequate compression |

| Cardio First Angel™ | Inotech (Nubberg, Germany) | Available | Tensile springs | Mechanical | Auditory Tactile |

Audible click Tactile click |

Compression depth Compression rate |

| CPR-1100 CPR Assista | Nihon Kohden Corp. (Tokyo, Japan) | Available | Accelerometer | Battery | Visual Auditory |

Light indicator Metronome Verbal Cue |

Compression depth Compression rate Device tilt Sinking of patient’s back |

| CPRCard™ | Laerdal (Stavanger, Norway) | Available | Accelerometer | Battery | Visual | Digital meters | Compression depth Compression rate |

| CPREzy™ | Health Affairs, LTD. (London, UK) | Available | Metronome Pressure sensor |

Battery | Visual | Light indicator | Compression depth Compression rate |

| CPR-plus™ | Kelly Medical Products (Princeton, USA) | Discontinued | Pressure sensor | Mechanical | Visual | Needle gauge | Compression depth |

| CPR PRO®b | Ivor Medical (Rijeka, Croatia) | Discontinued | Accelerometer | None | Audio Tactile Visual |

Digital screen of smartphone mounted on device | Compression depth |

| CPRmeter™ | Laerdal (Stavanger, Norway) | Discontinued | Accelerometer | Battery | Visual | Digital screen Inactivity timer |

Compression depth Compression rate |

| CPRmeter 2™ | Laerdal (Stavanger, Norway) | Available | Accelerometer | Battery | Visual | Digital screen Inactivity timer |

Compression depth Compression rate |

| CPR RsQ Assist® | CPR RsQ Assist Inc. (Naples, USA) | Available | Metronome | Battery | Auditory | Metronome Voice |

None |

| LinkCPR™ | SunLife Science (Shanghai, China) | Available | Accelerometer | Battery | Visual | Wristbanddigital screen | Compression depth Compression rate |

| Pocket CPR™ | Zoll Medical Corp. (Chelmsford, USA) | Available | Accelerometer | Battery | Auditory Visual |

Light indicator Metronome Verbal cue |

Compression depth Compression rate |

| TrueCPR™ | Physio-Control (Redmond, USA) | Available | Electromagnetic sensors | Battery | Auditory Visual |

Metronome Digital screen |

Compression depth Compression rate Verbal prompt for rescue breathing |

| U-cpr | |||||||

| ПР-01 (PR-01) | FactorMed Technika (Moscow, Russia) | Available | Accelerometer | Battery | Visual Auditory |

Light indicator Verbal cue |

Compression depth Compression rate |

aCan communicate with a Nihon Kohden defibrillator via Bluetooth connection, bThe base device does not contain measuring technology itself. It serves as an ergonomic consul or mount for an electronic device (e.g., iPhone with CPR PRO application) containing an accelerometer. CPR: Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Table 2.

Simulation randomized controlled manakin studies investigating chest compressions administered either with or without the assistance of a free-standing audiovisual feedback device (not linked to external monitor or automated external defibrillator)

| Device | Author (year) | Population | Sample size | Comparison | Primary outcome and findings | Secondary outcomes and findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPREzy™ | Beckers (2007) | Students | 202 | SMC | Device use associated with improved compression rate and depth | No change in full recoil or hand position |

| Bielski (2018) | Lifeguards | 41 | SMC | Compression depth was significantly better and the standard manual compression group. No-flow fraction did not improve | Device use improved full chest release (87% vs. 68%; P=0.02) | |

| Noordergraaf (2006) | Hospital employees | 224 | SMC | Fewer ineffective compressions in the device group | Decreased time to ineffective compressions in the device group | |

| Yeung (2014) | Life support providers (unspecified) | 101 | SMCQ-CPR with metronome | CPREzy™ use improved compression depth over both comparators | CPREzy™ use improved compression rate and decreased proportion of compressions with inadequate depth compared to both comparators. Compression release was unchanged | |

| Veiser (2010) | Paramedics, emergency physicians | 93 | SMC | Device group had improved percentage of compressions with correct depth and rate, and higher rate of error free compressions | ||

| CPR PRO® | Kovic (2013) | Health care providers | 24 | SMC | Decreased rescuer perceived exertion and maximal HR in device group | Decreased hand and wrist pain in device group |

| CPRmeter™ | Buléon (2013) | Students | 144 | SMC | Improved efficient compression rate in the device group | Improved compression rate and percentage of compressions of adequate depth in the device group |

| Buléon (2016) | Health care providers | 60 | SMC | Improved efficient compression rate in the device group | Improved compression rate, percentage of compressions of adequate depth, and adequate release in the device group | |

| Calvo-Buey (2016) | Health care providers | 88 | SMC | Improved compression depth and complete release in device group | Higher compression rate in device group, although rates in both groups met guideline standards | |

| Delaunay (2015)a | Health care providers | 60 | SMC | Improved correct compressions in device group | No change in compression rate | |

| Duwat (2014)a | Paramedics | 120 | SMC | Decrease in compressions of adequate depth in device group | Less dispersion of compression frequency with device use | |

| Iskrzycki (2018) | Lifeguards | 50 | SMC | Improved quality of CPR score (median 69 [33-77] vs. 84 [55-93]; P<0.001) | Compression score, depth and rate improved significantly in the device group | |

| CPR RsQ Assist® | Yuksen (2017) | Health care providers | 80 | SMC | Improved compression rate at 4 min in the device group | No change in compression depth at 2 min, but improved depth in controls at 4 min |

| LinkCPR™ | Liu (2018) | Laypersons | 124 | SMC | Improved compression rate and depth in device group | Improved correct compressions and compression fraction in device group |

| Pocket CPR™ | Grassl (2009) | Inexperienced laypersons | 42 | SMC | The device did not consistently improve compression depth or rate | |

| Pozner (2011) | Nurses | 12 | SMC | Increased compression depth and lower rate in the device group resulting increased compression rate in recommended range | Chest recoil and fatigue did not differ between groups | |

| TrueCPR™ | Al-Jeabory (2017) | Physicians | 60 | SMC | Increased compression depth and lower rate in the device group resulting in increased compression rate in recommended range | Decreased incorrect compressions in device group |

| Grassl (2016)a | Health care providers | 202 | SMC | Increased percentage of correct compressions with device | Compression rate within recommended rage for both groups | |

| Majer (2018) | Nurses | 38 | SMC | Lower rate in the device group resulting in increased compression rate in recommended range | Compression depth varied greatly in both groups. Full chest recoil was improved in the device group | |

| Ozel (2016) | Students | 83 | SMC with/out metronome | Device use associated with improved rate (both groups within guideline range) and depth |

aAbstract only. IQR: Inter-quartile range; SMC: Standard manual compressions; Q-CPR: Quantitative measurement of cardiopulmonary resuscitation; HR: Heart rate

Table 3.

Simulation randomized controlled manakin studies comparing chest compressions administered either with or without the assistance of a free-standing audiovisual feedback device (not linked to external monitor or automated external defibrillator), and comparing at least two devices

| Author (year) | Groups | Population | Sample size | Primary outcome and findings | Secondary outcomes and other findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bydzovsky (2015)a | CPREzy™ PocketCPR™ SMC |

Nurses | 152 | Both devices improved compression quality compared to SMC controls | Direct comparisons between the devices not provided |

| Davis (2018) | CPR RsQ Assist® PocketCPR™ TrueCPR™ SMC |

Students and healthcare providers | 118 | Compression depth was poor across all groups, but TrueCPR™ and PocketCPR™ demonstrated statically (not clinically) significant improvements compared to control and CPR RsQ Assist®. PocketCPR™ had the greatest % compressions with sufficient depth, while TrueCPR™ had the greatest % with adequate rate | Controls outperformed all devices in no‐flow time (P<0.001) and flow fraction (P<0.001). Full recoil was not improved by device use (P=0.31) |

| Dixon (2010)a | CPREzy™ Unspecified 1 Unspecified 2 |

Healthcare providers | 21 | No improvement in compression depth or compression effectiveness (depth vs. incomplete release vs. incorrect hand placement) | |

| Kurowski (2015) | PocketCPR™ TrueCPR™ SMC |

Paramedics | 167 | TrueCPR™ improved compression depth and effectiveness of compressions versus comparators | PocketCPR™ was the only group whose rate fell outside guideline recommendations |

| Schachinger (2013a)b | CPRmeter® PocketCPR™ SMC |

Students | 240 | A significant delay in time to first compression was noted for the PocketCPR™ versus others | |

| Schachinger (2013b)b | CPRmeter® PocketCPR™ SMC |

Students | 240 | All groups reached recommended compression depth and rate | ECR was lower for PocketCPR™ compared to SMC. Both devices showed improvement in ECR decline. |

| Zapletal (2014)b | CPRmeter® PocketCPR™ SMC |

Students | 240 | Effective compressions were significantly improved for PocketCPR™ versus CPRmeter® and SMC (others not significant) | Both devices showed improvement in ECR decline. Overall performance in the PocketCPR® group was considerably inferior to standard BLS |

aAbstract only; bSingle study. Data presented in 3 abstracts. Full manuscript not available. SMC: Standard manual compressions; ECR: Effective compression ratio; BLS: Basic life support

Table 4.

Prospective randomized human clinical trials of adult patients (age ≥18 years) being treated for in-hospital cardiac arrest with cardiopulmonary resuscitation including chest compressions administered either with or without the assistance of a free-standing audiovisual feedback device (not linked to external monitor or automated external defibrillator)

| Device | Author (year), Citation | Methodology | Setting | Sample size | Population | Primary outcome and findings | Secondary outcomes and findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambu CardioPump | Cohen (1993) | RCT | Inpatient | 62 | Adult patients in medical ICU, coronary care unit, cardiac-catheterization laboratory, and medical wards at 1 academic medical center | Improved sustained ROSC in the device group (62% vs. 30%; P<0.03). Improved survival for ≥24 h (45% vs. 9%; P<0.04) | No improvement in survival to hospital discharge (7% vs. 0%; P=NS). Improved neurological status (GCS) in device group (8.0±1.3 vs. 3.5±0.3; P<0.02) |

| Cardio First Angel™ | Goharani (2019) | RCT | ICU | 900 | Adult patients with cardiac arrest in a mixed med-surg ICU at 8 academic medical centers | Improved sustained ROSC in the device group (66.7% vs. 42.4%, P<0.001) | Improved survival to ICU discharge (59.8% vs. 33.6%) and survival to hospital discharge (54% vs. 28.4%, P<0.001) in the device group |

| Vahedian-Azimi (2016) | RCT | ICU | 80 | Adult patients with cardiac arrest in a mixed med-surg ICU at 4 academic medical centers | Improved sustained ROSC in device feedback group (72% vs. 35%; P=0.001) | Decrease in rib fractures (57% vs. 85%; P=0.02), but not sternum fractures (5% vs. 17%; P=0.15) | |

| Vahedian-Azimi (2020) | RCT | ICU | 22 | Adult patients with cardiac arrest in a mixed med-surg ICU at 4 academic medical centers | The incidence of ROSC was similar between groups (P=0.64) | Guideline adherence was improved in the intervention group (P=0.0005). No significant decrease in rib fractures (P=0.31) or sternum fractures (P=0.15) |

RCT: Randomized controlled trial; ICU: Intensive care unit; ROSC: Return of spontaneous circulation; GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale; NS: Nonsignificant

Data comparing free-standing non-AED AVF devices head-to-head are far fewer,[42,50,68,69,70,71,72] and which devices display the highest performance remains unclear. The objective of this project is to address the following research question: in patients with IHCA (population), does chest compression performed with a free-standing non-AED AVF device as compared to standard manual chest compressions (comparison) result in improved outcomes including sustained ROSC, and survival to ICU and survival to hospital discharge (outcomes).

METHODS

Prospective human RCTs of adult patients (age ≥ 18 years) being treated for IHCA with CPR, including chest compressions, were considered for inclusion. All trials were required to compare standard manual chest compressions to chest compressions performed with a free-standing AVF device (not linked to an external monitor or AED). AFV devices linked to AEDs or automated compressors differ significantly from smaller free-standing (generally handheld) AVF devices. These devices often differ in the underlying technology, software algorithms, and intrinsic capabilities, as well as in size, cost, and the logistic practicality of deployment and maintenance in non-acute care (e.g. emergency department) or critical care environments (e.g. general medical floors). Prior meta-analyses have either excluded the free-standing AVF devices or combined their data that of devices linked to AEDs or automatic compressors.[75,76] This effort represents the first meta-analysis assessing only the free-standing AVF device subgroup.

The primary outcome was sustained ROSC, defined as ROSC lasting >30 min. The secondary outcomes were survival to intensive care unit (ICU) discharge, survival to hospital discharge, and adverse events. The project was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020157536).

A comprehensive literature search strategy [Appendix 1] was developed in conjunction with a librarian specializing in systematic reviews of the following databases: China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Cochrane CENTRAL, CINAHL, Directory of Open Access Journals, Embase, Korean Journal Database, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature, IEEE-Xplorer, information/Chinese Scientific Journals Database, Google Scholar, Magiran, PsycInfo, PubMed, Scopus, Scientific Electronic Library Online, Scientific Information Database, Turkish Academic Network and Information Center (TÜBİTAK ULAKBİM), Research Gate, Russian Science Citation Index, and Web of Science. The search terms included the following National Library of Medicine MeSH terms: CPR, and heart arrest. Additional non-MeSH terms included cardiac arrest, in-hospital, and the following individual device names: Beaty, Cardio First Angel, CardioPump, CPR-1100 CPR Assist, CPRCard, CPREzy, CPR-plus, CPR PRO, CPRmeter, CPR RsQ Assist, LinkCPR, Pocket CPR, PrestoPatch, PrestoPush, TrueCPR and ПP -01 (PR-01).

Only clinical RCT of free-standing compression AVF devices were included. Crossover studies and those assessing AED-linked devices were excluded. Searches were not limited by date, language, or publication status. To limit publication bias, clinical trial registries were searched including ClinicalTrials.gov, World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP), and the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR). The bibliographies of the relevant articles were also searched. Conference proceeding from relevant disciplines in the past 5 years were also searched. Experts in the field were also contacted to inquire about possible ongoing trials. Grey literature was only eligible for inclusion if the authors responded to correspondence affirmatively with the requested information.

Risk-of-bias (RoB) was assessed using two validated tools: (1) Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE),[78] and (2) RoB 2.0: Revised tool for Risk of Bias in randomized trials.[78] The authors considered methods of randomization and allocation, blinding (of treatment administrator, participants, and outcome assessors), selective outcome reporting (e.g., failure to report adverse events), incomplete outcome data, and sample size calculation. Each trial was graded as high, low, or unclear RoB for each of these criteria.

Statistical analysis

Model selection depended on assessments of common effect size. A fixed-effects model was used if all studies share the same true effect and the inter-study observed effect varied because of random error, or there was intra-study variation. A random-effects model was used if the true effect differed between studies due to inter-and intra-study variation. This was conducted using a restricted maximum likelihood method utilizing the “meta” code.[79]

The presence of heterogeneity and its impact on the meta-analysis was evaluated using the Cochran's Chi-square or Q test (P > 0.10) and I-Squared (I2) index (I2≥ 75% indicating considerable heterogeneity) respectively.[80] However, it is known that Cochran's Chi-square suffers from poor power when the number of collected studies is small.[81] In addition, outlying studies can have a great impact on conventional heterogeneity measures and on the conclusions of a meta-analysis.[81] For this reason, the Tau-squared (τ2) was used as a second means to determine the between-study variance.[81] In the event of significant heterogeneity between studies, we planned to do subgroup analysis or meta-regression. If significant heterogeneity did not exist, then meta-regression was not to be performed.

The common effect size was calculated as the hazard ratio (HR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) for each main outcome. In addition, the visual assessment of the forest plots was used to find the magnitude of differences.

Publication was assessed using funnel plot analysis and the Begg and Mazumdar,[82] Egger et al.,[83] or Harbord's et al.[84] tests, where appropriate. A nonparametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication bias (ref) was conducted, and the modified effect size was estimated after adjusting for publication bias.[85]

We preplanned a sensitivity analysis to examine the effect of each study on the pooled effect size. All analyses were performed using STATA16 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

RESULTS

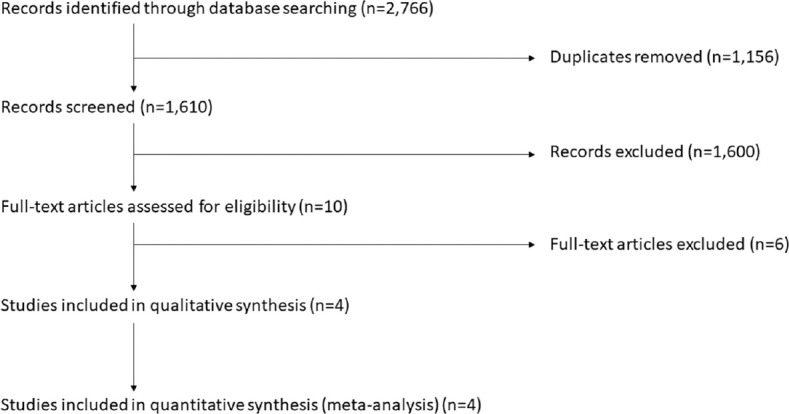

The primary search yielded 2,766 references. Figure 1 from the Prisma flow diagram. Four clinical RCTs met the inclusion criteria. No ongoing trials were identified in Clinicaltrials.gov, WHO ICTRP, or ANZCTR. One of 4 clinical RCTs assessed the active compression active decompression Ambu CardioPump (Ambu Inc., Columbia, MD, USA),[73] whereas 3 assessed the active compression passive decompression Cardio First Angel™ [Inotech, Nubberg, Germany; Table 4].[3,51,74] No clinical RCTs compared AVF devices head-to-head. Three of 4 studies were multi-center,[3,51,74] whereas 1 was single-center.[73] One clinical RCT took place in a high-income economy (USA).[73] Three studies took place in a middle-income economy (Iran).[3,51,74]

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

The results of the trials' quality assessments are summarized in summarized in Table 5. All 4 studies were reported as low risk of selection bias. Three of 4 studies were low risk for allocation concealment,[3,51,74] whereas concealment was not described in 1 study and was thus marked unclear.[73] In none of the studies were personnel blinded as sham device use was deemed unethical or impractical; however, this may introduce performance bias. All four studies contained a control group (standard manual compressions). Each of the four included studies was low risk for attrition bias. All included studies reported their intended primary outcomes. One study did not report adverse events.[73] All included studies reported a sample size or power calculation.

Table 5.

Grade quality of evidence ratings

| Certainty assessment |

Summary of findings |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study number | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Number of patients |

Effect |

|||

| CC with AVF device | Standard manual CC | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute (95% CI) | Certainty | |||||||

| Sustained ROSC | |||||||||||

| 4 | RCT | Not serious | Seriousa | Not serious | Not serious | None | 351/530 (66.2%) | 217/534 (40.6%) | RR 1.68 (1.39-2.04) | 276 more per 1000 (from 158 more to 423 more) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| Survival to ICU discharge | |||||||||||

| 2 | RCT | Not serious | Seriousa | Not serious | Not serious | None | 278/461 (60.3%) | 156/461 (33.8%) | RR 1.78 (1.54-2.06) | 264 more per 1000 (from 189 more to 359 more) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| Survival to hospital discharge | |||||||||||

| 3 | RCT | Not serious | Seriousa | Not serious | Not serious | None | 253/490 (51.6%) | 132/494 (26.7%) | RR 1.91 (1.62-2.25) | 243 more per 1000 (from 166 more to 334 more) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

aRisk of bias due to lack of blinding. CC: Chest compressions; AVF: Audiovisual feedback; ROSC: Return of spontaneous circulation; RCT: Randomized controlled trial; CI: Confidence interval; RR: Relative risk

Low heterogeneity was observed between studies for all study outcomes (I2 range 0–13.9, τ2 range 0–0.01, all P > 0.05). The small study number limits the interpretation of the funnel plots. However, the Egger's, Begg's and Harbord's test results indicated no significant bias [Table 6]. Heterogeneity was sought within individual studies by sensitivity analysis. The results showed that the range of HR after removing a study was within the 95% CI of HR, indicating low heterogenity [Table 7].

Table 6.

Assessment of publication bias using the Begg’s, Egger’s, and Harbord’s tests

| Outcomes | Begg’s test |

Egger’s test |

Harbord’s test |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z | P | Z | P | Z | P | |

| Initial rhythm asystole | −1.04 | 0.703 | −0.17 | 0.865 | −0.60 | 0.548 |

| Initial rhythm VF or VT | 1.56 | 0.118 | 1.53 | 0.124 | 0.96 | 0.252 |

| Initial rhythm “other” | 1.04 | 0.296 | 1.00 | 0.316 | 1.05 | 0.293 |

| Intubated before arrest | 0.00 | 1.000 | 0.62 | 0.534 | 0.64 | 0.523 |

| Sustained ROSC | −0.34 | 0.865 | 1.21 | 0.226 | 1.24 | 0.215 |

| Survival to ICU discharge | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Survival to hospital discharge | 1.04 | 0.296 | 0.55 | 0.585 | 0.91 | 0.363 |

VF: Ventricular fibrillation; VT: Ventricular tachycardia; ROSC: Return of spontaneous circulation; ICU: Intensive care unit

Table 7.

The results of sensitivity analyses

| QOL | Sensitivity analyses results |

|---|---|

| HR range after removing the study | |

| Initial rhythm asystole | 0.492-1.744 |

| Initial rhythm VF or VT | 0.591-1.326 |

| Initial rhythm “other” | 0.666-4.290 |

| Intubated before arrest | 0.618-1.495 |

| Sustained ROSC | 1.408-2.933 |

| Survival to ICU discharge | 0.946-4.956 |

| Survival to hospital discharge | 0.890-3.642 |

VF: Ventricular fibrillation; VT: Ventricular tachycardia; ROSC: Return of spontaneous circulation; ICU: Intensive care unit; QOL: Quality of life; HR: Heart rate

The results of the meta-analysis on the common effect size revealed no significant difference between device and control groups for baseline rhythm (asystole, ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, other) and intubation before arrest (all P > 0.05).

Sustained ROSC (4 studies, n = 1064) was improved with AVF use (Relative risk [RR] 1.68, 95% CI 1.39–2.04).[3,51,74,75] Survival to hospital discharge (2 studies, n = 922) was also improved with AVF use (RR 1.78, 95% CI 1.54–2.06),[51,74] as was survival to hospital discharge (3 studies, n = 984; RR 1.91, 95% CI 1.62–2.25).[51,73,74] Although not an endpoint of our meta-analysis, one study reported the endpoint of survival ≥ 24 h and found improvement with AVF device use.[73] In addition, only one study reported on neurologic status, similarly finding improvements with AVF device use; however, this was also not an endpoint for our analysis.[73] As there was no substantial heterogeneity in the models, no meta-regression was conducted.

DISCUSSION

Many factors may influence IHCA outcomes. Hospital-level factors such as bed size, location, and academic status have all been shown to influence ICHA outcomes.[86] Other confounding factors include hospital wealth and cultural beliefs surrounding end-of-life care.[87] Reported rates of ROSC vary from as low as 20% (Iran)[4] to as high as 71% (Brazil);[7] however, a meta-analysis of studies published between 2006 and 2015 found that IHCA ROSC rates average 47%–48% with survival to hospital discharge rates averaging a dismal 14%–15%.[26]

A large gap exists between current knowledge of CPR quality and its optimal implementation, contributing to potentially preventable deaths.[74,88] Early defibrillation (when appropriate) and initiation of CPR with quality compressions remain cornerstones of resuscitation.[3,30,31,32,33,34,35,74] Real-time AVF is one strategy identified by the AHA and ILCOR as a strategy that may improve guideline adherence and IHCA outcomes.[27,33,35] Simulated studies show improved CPR quality with feedback devices [Tables 2 and 3];[42,44,45],48,,52,[53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72] however, the evidence for improvement in clinical outcomes is still very limited [Tables 4 and 5].[3,51,73,74] That said, these devices have also been shown to be easy to use by both medical professionals and lay persons[45] and remain an understudied opportunity to improve IHCA outcomes.

AFV devices linked to AED's or automated compressors differ significantly from small free-standing (generally handheld) AVF devices. Not only do they differ in the underlying technology, software algorithms, and intrinsic capabilities but also in size, cost, and the logistic practicality of deployment and maintenance in non-acute care (e.g. emergency department) or critical care environments (e.g. general medical floors). Prior meta-analyses have either excluded the free-standing AVF devices or combined their data with that of devices linked to AEDs or automatic compressors.[75,76] This effort represents the first meta-analysis assessing only the free-standing AVF device subgroup. Despite a large number of AVF devices on the market, only two devices (4 studies) have published RCT results. The remainder have only been studied in medical simulation scenarios or have no published studies. The small number of included studies is a limitation of this analysis. That said, the results suggest that real-time AVF with a free-standing AVF device (either Ambu CardioPump or Cardio First Angel™) when managing IHCA is associated with improved rates of sustained ROSC and survival to ICU and hospital discharge. Patients who received CPR with AVF device use were 1.68 times as likely to have sustained ROSC, 1.78 times as likely to survive to ICU discharge, and 1.91 times to survive to hospital discharge compared to those who received standard CPR.

These results are likely generalizable to ICU patients in middle- and high-income countries. Three of the studies took place in a middle-income economy (Iran), while one was conducted in a high-income economy (USA). Of note, Iran has a similar prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors as in the United States.[89] The impact on resuscitation efforts in healthcare environments in low-income economies remains unclear.

Free-standing AVF devices have the potential to improve patient outcomes following IHCA. These devices have the advantages of being inexpensive, portable, and low maintenance as compared to devices linked to AEDs or automated compressors. As such, they could be more widely available to providers outside acute care environments like the ICU, emergency department, or operating theater. However, these results should be interpreted with caution, as insufficient evidence is available to comment on long-term neurological or functional status or discharge destination (i.e. home, rehab, long-term care facility). In addition, data were not stratified by specialty or practice experience level of the provider (e.g. nurse, resident physician, attending physician) using the device. Moreover, no data were available regarding provider injuries with device use (e.g. wrist or back injuries) as some have voiced concern regarding this matter.[90,91] Greater study of these devices is needed before the widespread implementation of their use in inpatient care environments.

CONCLUSION

The existing moderate certainty evidence suggests that chest compressions performed using a non-AED free-standing AVF device during resuscitation for IHCA may improve rates of sustained ROSC and survival to ICU and hospital discharge. Data on discharge destination, level of health, and neurologic status on discharge are lacking.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Research quality and ethics statement

Data used in this article came from publicly available sources that contain aggregate, de-identified information only. Thererefore, Institutional Review Board approval was not required. Applicable EQUATOR Network (https://www.equator-network.org/) research reporting guidelines were followed.

Appendix 1: Literature Search Strategy

MEDLINE via PubMed:

(”Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation”[Mesh] OR “Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation”[tiab] OR CPR[tiab] OR “Cardio-pulmonary resuscitation”[tiab] OR “Cardio pulmonary resuscitation”[tiab] OR “Basic Cardiac Life Support”[tiab] OR “chest compression”[tiab] OR “chest compressions”[tiab])

AND

(”Equipment Design”[Mesh] OR “Mobile Applications”[Mesh] OR “real-time”[tiab] OR “real time”[tiab] OR “Cardio First Angel”[tiab] OR “Ambu CardioPump”[tiab] OR “CPR-1100 CPR Assist”[tiab] OR CPRCard[tiab] OR CPREzy[tiab] OR “CPR-plus”[tiab] OR “CPR PRO”[tiab] OR CPRmeter[tiab] OR “CPR RsQ Assist”[tiab] OR LinkCPR[tiab] OR Pocket CPR[tiab] OR TrueCPR[tiab] OR “PR-01”[tiab] OR QCPR[tiab] OR “ZOLL AED Plus”[tiab] OR “Intellisense CPR”[tiab] OR “feedback device”[tiab] OR “feedback devices”[tiab] OR “adjunct device”[tiab] OR “adjunct devices”[tiab] OR ((”hand-held”[tiab] OR portable[tiab]) AND (device[tiab] OR devices[tiab])) OR “mobile application”[tiab] OR “mobile applications”[tiab] OR “mobile apps”[tiab] OR “electronic apps”[tiab] OR “software application”[tiab] OR “software applications”[tiab] OR “software app”[tiab] OR “software apps”[tiab])

AND

(”randomized controlled trial”[pt] OR “controlled clinical trial”[pt] OR randomized[tiab] OR placebo[tiab] OR “drug therapy”[sh] OR randomly[tiab] OR trial[tiab] OR groups[tiab] NOT (”animals”[mh] NOT “humans”[mh]))

CINAHL

((MH “Resuscitation, Cardiopulmonary”) OR (MH “Advanced Cardiac Life Support”) OR TI (”Cardio-pulmonary resuscitation” OR “Cardio pulmonary resuscitation” OR “Basic Cardiac Life Support” OR “chest compression” OR “chest compressions”) OR AB (”Cardio-pulmonary resuscitation” OR “Cardio pulmonary resuscitation” OR “Basic Cardiac Life Support” OR “chest compression” OR “chest compressions”))

AND

((MH “Mobile Applications”) OR (MH “Biophysical Instruments”) OR (MH “Equipment Design”) OR (MH “Equipment and Supplies”) OR TI (”real-time” OR “real time” OR “Cardio First Angel” OR “Ambu CardioPump” OR “CPR-1100 CPR Assist” OR CPRCard OR CPREzy OR “CPR-plus” OR “CPR PRO” OR CPRmeter OR “CPR RsQ Assist” OR LinkCPR OR Pocket CPR OR TrueCPR OR “PR-01” OR QCPR OR “ZOLL AED Plus” OR “Intellisense CPR” OR “feedback device” OR “feedback devices” OR “adjunct device” OR “adjunct devices” OR ((”hand-held” OR portable) AND (device OR devices)) OR “mobile application” OR “mobile applications” OR “mobile apps” OR “electronic apps” OR “software application” OR “software applications” OR “software app” OR “software apps”) OR AB (”real-time” OR “real time” OR “Cardio First Angel” OR “Ambu CardioPump” OR “CPR-1100 CPR Assist” OR CPRCard OR CPREzy OR “CPR-plus” OR “CPR PRO” OR CPRmeter OR “CPR RsQ Assist” OR LinkCPR OR Pocket CPR OR TrueCPR OR “PR-01” OR QCPR OR “ZOLL AED Plus” OR “Intellisense CPR” OR “feedback device” OR “feedback devices” OR “adjunct device” OR “adjunct devices” OR ((”hand-held” OR portable) AND (device OR devices)) OR “mobile application” OR “mobile applications” OR “mobile apps” OR “electronic apps” OR “software application” OR “software applications” OR “software app” OR “software apps”))

China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CHKD-CNKI)

((”Cardiopulmonary resuscitation” OR “Compression” OR “CPR” OR “cardiac arrest”) AND “feedback” AND “in-hospital”) OR (”Cardio First Angel” OR “CardioPump” OR “Beaty” OR “CPR Assist” OR “CPRCard” OR “CPR-plus” OR “CPR Pro” OR “CPRmeter” OR “CRP RsQ” OR “LinkCPR” OR “Pocket CPR” OR “TrueCPR” OR “U-CPR” OR “??-01” OR “PR-01”)

Cochrane CENTRAL

(cardiopulmonary resuscitation.sh. OR (Cardio-pulmonary resuscitation or Cardio pulmonary resuscitation or Basic Cardiac Life Support or chest compression or chest compressions).mp.)

AND

(mobile applications.sh. OR equipment design.sh. OR (real-time OR real time OR Cardio First Angel OR Ambu CardioPump OR CPR-1100 CPR Assist OR CPRCard OR CPREzy OR CPR-plus OR CPR PRO OR CPRmeter OR CPR RsQ Assist OR LinkCPR OR Pocket CPR OR TrueCPR OR PR-01 OR QCPR OR ZOLL AED Plus OR Intellisense CPR OR feedback device OR feedback devices OR adjunct device OR adjunct devices OR ((hand-held OR portable) AND (device OR devices)) OR mobile application OR mobile applications OR mobile apps OR electronic apps OR software application OR software applications OR software app OR software apps).mp)

information/Chinese Scientific Journals database (CSJD-VIP)

((”Cardiopulmonary resuscitation” OR “Compression” OR “CPR” OR “cardiac arrest”) AND “feedback” OR “in-hospital”) OR (”Cardio First Angel” OR “CardioPump” OR “Beaty” OR “CPR Assist” OR “CPRCard” OR “CPR-plus” OR “CPR Pro” OR “CPRmeter” OR “CRP RsQ” OR “LinkCPR” OR “Pocket CPR” OR “TrueCPR” OR “U-CPR” OR “??-01” OR “PR-01”)

Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ)

((”Cardiopulmonary resuscitation” OR “Compression” OR “CPR” OR “cardiac arrest”) AND “feedback” OR “in-hospital”) OR (”Cardio First Angel” OR “CardioPump” OR “Beaty” OR “CPR Assist” OR “CPRCard” OR “CPR-plus” OR “CPR Pro” OR “CPRmeter” OR “CRP RsQ” OR “LinkCPR” OR “Pocket CPR” OR “TrueCPR” OR “U-CPR” OR “??-01” OR “PR-01”)

EMBASE

('resuscitation'/exp OR “Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation”:ab, ti OR CPR: ab, ti OR “Cardio-pulmonary resuscitation”:ab, ti OR “Cardio pulmonary resuscitation”:ab, ti OR “Basic Cardiac Life Support”:ab, ti OR “chest compression”:ab, ti OR “chest compressions”:ab, ti)

AND

('CPR feedback device'/exp OR 'mobile health application'/exp OR “real-time”:ab, ti OR “real time”:ab, ti OR “Cardio First Angel”:ab, ti OR “Ambu CardioPump”:ab, ti OR “CPR-1100 CPR Assist”:ab, ti OR CPRCard: ab, ti OR CPREzy: ab, ti OR “CPR-plus”:ab, ti OR “CPR PRO”:ab, ti OR CPRmeter: ab, ti OR “CPR RsQ Assist”:ab, ti OR LinkCPR: ab, ti OR Pocket CPR: ab, ti OR TrueCPR: ab, ti OR “PR-01”:ab, ti OR QCPR: ab, ti OR “ZOLL AED Plus”:ab, ti OR “Intellisense CPR”:ab, ti OR “feedback device”:ab, ti OR “feedback devices”:ab, ti OR “adjunct device”:ab, ti OR “adjunct devices”:ab, ti OR ((”hand-held”:ab, ti OR portable: ab, ti) AND (device: ab, ti OR devices: ab, ti)) OR “mobile application”:ab, ti OR “mobile applications”:ab, ti OR “mobile apps”:ab, ti OR “electronic apps”:ab, ti OR “software application”:ab, ti OR “software applications”:ab, ti OR “software app”:ab, ti OR “software apps”:ab, ti)

AND

('crossover procedure':de OR 'double-blind procedure':de OR 'randomized controlled trial':de OR 'single-blind procedure':de OR (random* OR factorial* OR crossover* OR cross NEXT/1 over* OR placebo* OR doubl* NEAR/1 blind* OR singl* NEAR/1 blind* OR assign* OR allocat* OR volunteer*):de, ab, ti)

Korean Journal Database (KCI)

((”Cardiopulmonary resuscitation” OR “Compression” OR “CPR” OR “cardiac arrest”) AND “feedback”) OR (”Cardio First Angel” OR “CardioPump” OR “Beaty” OR “CPR Assist” OR “CPRCard” OR “CPR-plus” OR “CPR Pro” OR “CPRmeter” OR “CRP RsQ” OR “LinkCPR” OR “Pocket CPR” OR “TrueCPR” OR “U-CPR” OR “??-01” OR “PR-01”)

Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature

(tw:(”Cardio-pulmonary resuscitation” OR “Cardio pulmonary resuscitation” OR “Basic Cardiac Life Support” OR “chest compression” OR “chest compressions” OR cpr))

AND

(tw:(”real-time” OR “real time” OR “Cardio First Angel” OR “Ambu CardioPump” OR “CPR-1100 CPR Assist” OR cprcard OR cprezy OR “CPR-plus” OR “CPR PRO” OR cprmeter OR “CPR RsQ Assist” OR linkcpr OR pocket AND cpr OR truecpr OR “PR-01” OR qcpr OR “ZOLL AED Plus” OR “Intellisense CPR” OR “feedback device” OR “feedback devices” OR “adjunct device” OR “adjunct devices” OR ((”hand-held” OR portable) AND (device OR devices)) OR “mobile application” OR “mobile applications” OR “mobile apps” OR “electronic apps” OR “software application” OR “software applications” OR “software app” OR “software apps”))

Magiran

((”Cardiopulmonary resuscitation” OR “Compression” OR “CPR” OR “cardiac arrest”) AND “feedback”) OR (”Cardio First Angel” OR “CardioPump” OR “Beaty” OR “CPR Assist” OR “CPRCard” OR “CPR-plus” OR “CPR Pro” OR “CPRmeter” OR “CRP RsQ” OR “LinkCPR” OR “Pocket CPR” OR “TrueCPR” OR “U-CPR” OR “??-01” OR “PR-01”)

Russian Science Citation Index

(”Cardiopulmonary resuscitation” OR “Compression” OR “CPR” OR “cardiac arrest”) OR (”Cardio First Angel” OR “CardioPump” OR “Beaty” OR “CPR Assist” OR “CPRCard” OR “CPR-plus” OR “CPR Pro” OR “CPRmeter” OR “CRP RsQ” OR “LinkCPR” OR “Pocket CPR” OR “TrueCPR” OR “U-CPR” OR “??-01” OR “PR-01”)

Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO)

((”Cardiopulmonary resuscitation” OR “Compression” OR “CPR” OR “cardiac arrest”) AND “Feedback”) OR (”Cardio First Angel” OR “CardioPump” OR “Beaty” OR “CPR Assist” OR “CPRCard” OR “CPR-plus” OR “CPR Pro” OR “CPRmeter” OR “CRP RsQ” OR “LinkCPR” OR “Pocket CPR” OR “TrueCPR” OR “U-CPR” OR “??-01” OR “PR-01”)

Scopus

(TITLE-ABS-KEY (”real-time” OR “real time” OR “Cardio First Angel” OR “Ambu CardioPump” OR “CPR-1100 CPR Assist” OR cprcard OR cprezy OR “CPR-plus” OR “CPR PRO” OR cprmeter OR “CPR RsQ Assist” OR linkcpr OR pocket AND cpr OR truecpr OR “PR-01” OR qcpr OR “ZOLL AED Plus” OR “Intellisense CPR” OR “feedback device” OR “feedback devices” OR “adjunct device” OR “adjunct devices” OR ((”hand-held” OR portable) AND (device OR devices)) OR “mobile application” OR “mobile applications” OR “mobile apps” OR “electronic apps” OR “software application” OR “software applications” OR “software app” OR “software apps”))

AND

(TITLE-ABS-KEY (”Cardio-pulmonary resuscitation” OR “Cardio pulmonary resuscitation” OR “Basic Cardiac Life Support” OR “chest compression” OR “chest compressions” OR cpr))

Tübitak Ulakbim

((”Cardiopulmonary resuscitation” OR “Compression” OR “CPR” OR “cardiac arrest”) AND “feedback”) OR (”Cardio First Angel” OR “CardioPump” OR “Beaty” OR “CPR Assist” OR “CPRCard” OR “CPR-plus” OR “CPR Pro” OR “CPRmeter” OR “CRP RsQ” OR “LinkCPR” OR “Pocket CPR” OR “TrueCPR” OR “U-CPR” OR “??-01” OR “PR-01”)

Web of Science

TS=(”real-time” OR “real time” OR “Cardio First Angel” OR “Ambu CardioPump” OR “CPR-1100 CPR Assist” OR cprcard OR cprezy OR “CPR-plus” OR “CPR PRO” OR cprmeter OR “CPR RsQ Assist” OR linkcpr OR pocket AND cpr OR truecpr OR “PR-01” OR qcpr OR “ZOLL AED Plus” OR “Intellisense CPR” OR “feedback device” OR “feedback devices” OR “adjunct device” OR “adjunct devices” OR ((”hand-held” OR portable) AND (device OR devices)) OR “mobile application” OR “mobile applications” OR “mobile apps” OR “electronic apps” OR “software application” OR “software applications” OR “software app” OR “software apps”)

AND

TS=(”Cardio-pulmonary resuscitation” OR “Cardio pulmonary resuscitation” OR “Basic Cardiac Life Support” OR “chest compression” OR “chest compressions” OR cpr)

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen LW, Holmberg MJ, Berg KM, Donnino MW, Granfeldt A. In-hospital cardiac arrest: A Review. JAMA. 2019;321:1200–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perman SM, Stanton E, Soar J, Berg RA, Donnino MW, Mikkelsen ME, et al. Location of in-hospital cardiac arrest in the United States-Variability in event rate and outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003638. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vahedian-Azimi A, Hajiesmaeili M, Amirsavadkouhi A, Jamaati H, Izadi M, Madani SJ, et al. Effect of the cardio first AngelTM device on CPR indices: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Crit Care. 2016;20:147. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1296-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajbaghery MA, Mousavi G, Akbari H. Factors influencing survival after in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2005;66:317–21. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Movahedi A, Mirhafez SR, Behnam-Voshani H, Reihani H, A Ferns G, Malekzadeh J. 24-Hour survival after cardiopulmonary resuscitation is reduced in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2017;9:175–8. doi: 10.15171/jcvtr.2017.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boland Parvaz SH, Mohammadzadeh A, Amini A, Abbasi HR, Ahmadi MM, Ghafaripour S. Cardiopulmonary arrest outcome in Nemazee Hospital, Southern Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2009;11:437–41. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva RM, Silva BA, Silva FJ, Amaral CF. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of adults with in-hospital cardiac arrest using the Utstein style. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2016;28:427–35. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20160076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donoghue AJ, Abella BS, Merchant R, Praestgaard A, Topjian A, Berg R, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation for in-hospital events in the emergency department: A comparison of adult and pediatric outcomes and care processes. Resuscitation. 2015;92:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mallikethi-Reddy S, Briasoulis A, Akintoye E, Jagadeesh K, Brook RD, Rubenfire M, et al. Incidence and survival after in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in nonelderly adults: US experience, 2007 to 2012. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10:e003194. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fennelly NK, McPhillips C, Gilligan P. Arrest in hospital: A study of in hospital cardiac arrest outcomes. Ir Med J. 2014;107:105–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Sullivan E, Deasy C. In-hospital cardiac arrest at cork university hospital. Ir Med J. 2016;109:335–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergum D, Haugen BO, Nordseth T, Mjølstad OC, Skogvoll E. Recognizing the causes of in-hospital cardiac arrest-a survival benefit. Resuscitation. 2015;97:91–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.09.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pembeci K, Yildirim A, Turan E, Buget M, Camci E, Senturk M, et al. Assessment of the success of cardiopulmonary resuscitation attempts performed in a Turkish university hospital. Resuscitation. 2006;68:221–9. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yokoyama H, Yonemoto N, Yonezawa K, Fuse J, Shimizu N, Hayashi T, et al. Report from the Japanese registry of CPR for in-hospital cardiac arrest (J-RCPR) Circ J. 2011;75:815–22. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang CH, Chen WJ, Ma MH, Chang WT, Lai CL, Lee YT. Factors influencing the outcomes after in-hospital resuscitation in Taiwan. Resuscitation. 2002;53:265–70. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(02)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang CH, Chen WJ, Chang WT, Tsai MS, Yu PH, Wu YW, et al. The association between timing of tracheal intubation and outcomes of adult in-hospital cardiac arrest: A retrospective cohort study. Resuscitation. 2016;105:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shao F, Li CS, Liang LR, Qin J, Ding N, Fu Y, et al. Incidence and outcome of adult in-hospital cardiac arrest in Beijing, China. Resuscitation. 2016;102:51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan JC, Wong TW, Graham CA. Factors associated with survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest in Hong Kong. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:883–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fennessy G, Hilton A, Radford S, Bellomo R, Jones D. The epidemiology of in-hospital cardiac arrests in Australia and New Zealand. Intern Med J. 2016;46:1172–81. doi: 10.1111/imj.13039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Girotra S, Nallamothu BK, Spertus JA, Li Y, Krumholz HM, Chan PS, et al. Trends in survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1912–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peberdy MA, Kaye W, Ornato JP, Larkin GL, Nadkarni V, Mancini ME, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of adults in the hospital: A report of 14720 cardiac arrests from the national registry of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2003;58:297–308. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(03)00215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bansal A, Singh T, Ahluwalia G, Singh P. Outcome and predictors of cardiopulmonary resuscitation among patients admitted in Medical Intensive Care Unit in North India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2016;20:159–63. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.178179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong ML, Carey S, Mader TJ, Wang HE. American Heart Association National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Investigators. Time to invasive airway placement and resuscitation outcomes after inhospital cardiopulmonary arrest. Resuscitation. 2010;81:182–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Alwan A, Ehlenbach WJ, Menon PR, Young MP, Stapleton RD. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation among mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:556–63. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3247-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aziz F, Paulo MS, Dababneh EH, Loney T. Epidemiology of in-hospital cardiac arrest in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2013-2015. Heart Asia. 2018;10:e011029. doi: 10.1136/heartasia-2018-011029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu A, Zhang J. Meta-analysis of outcomes of the 2005 and 2010 cardiopulmonary resuscitation guidelines for adults with in-hospital cardiac arrest. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:1133–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morrison LJ, Neumar RW, Zimmerman JL, Link MS, Newby LK, McMullan PW, Jr, et al. Strategies for improving survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest in the United States: 2013 consensus recommendations: A consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:1538–63. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828b2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallmuller C, Meron G, Kurkciyan I, Schober A, Stratil P, Sterz F. Causes of in-hospital cardiac arrest and influence on outcome. Resuscitation. 2012;83:1206–11. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohn AC, Wilson WM, Yan B, Joshi SB, Heily M, Morley P, et al. Analysis of clinical outcomes following in-hospital adult cardiac arrest. Intern Med J. 2004;34:398–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valenzuela TD, Kern KB, Clark LL, Berg RA, Berg MD, Berg DD, et al. Interruptions of chest compressions during emergency medical systems resuscitation. Circulation. 2005;112:1259–65. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.537282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christenson J, Andrusiek D, Everson-Stewart S, Kudenchuk P, Hostler D, Powell J, et al. Chest compression fraction determines survival in patients with out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation. Circulation. 2009;120:1241–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.852202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Idris AH, Guffey D, Aufderheide TP, Brown S, Morrison LJ, Nichols P, et al. Relationship between chest compression rates and outcomes from cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2012;125:3004–12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.059535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhanji F, Finn JC, Lockey A, Monsieurs K, Frengley R, Iwami T, et al. Part 8: Education, implementation, and teams: 2015 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Circulation. 2015;132:S242–68. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hazinski MF, Nolan JP, Aickin R, Bhanji F, Billi JE, Callaway CW, et al. Part 1: Executive summary: 2015 International consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Circulation. 2015;132:S2–39. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soar J, Mancini ME, Bhanji F, Billi JE, Dennett J, Finn J, et al. Part 12: Education, implementation, and teams: 2010 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Resuscitation. 2010;81(Suppl 1):e288–330. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koster RW, Baubin MA, Bossaert LL, Caballero A, Cassan P, Castrén M, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines for resuscitation 2010 section 2.Adult basic life support and use of automated external defibrillators. Resuscitation. 2010;81:1277–92. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abella BS, Alvarado JP, Myklebust H, Edelson DP, Barry A, O'Hearn N, et al. Quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation during in-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2005;293:305–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stiell IG, Brown SP, Christenson J, Cheskes S, Nichol G, Powell J, et al. What is the role of chest compression depth during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest resuscitation.? Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1192–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823bc8bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abella BS, Edelson DP, Kim S, Retzer E, Myklebust H, Barry AM, et al. CPR quality improvement during in-hospital cardiac arrest using a real-time audiovisual feedback system. Resuscitation. 2007;73:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edelson DP, Litzinger B, Arora V, Walsh D, Kim S, Lauderdale DS, et al. Improving in-hospital cardiac arrest process and outcomes with performance debriefing. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1063–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.10.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Couper K, Kimani PK, Abella BS, Chilwan M, Cooke MW, Davies RP, et al. The system-wide effect of real-time audiovisual feedback and postevent debriefing for in-hospital cardiac arrest: The cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality improvement initiative. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:2321–31. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kurowski A, Szarpak Ł, Bogdański Ł, Zaśko P, Czyżewski Ł. Comparison of the effectiveness of cardiopulmonary resuscitation with standard manual chest compressions and the use of TrueCPR and PocketCPR feedback devices. Kardiol Pol. 2015;73:924–30. doi: 10.5603/KP.a2015.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Truszewski Z, Szarpak L, Kurowski A, Evrin T, Zasko P, Bogdanski L, et al. Randomized trial of the chest compressions effectiveness comparing 3 feedback CPR devices and standard basic life support by nurses. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:381–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kovic I, Lulic D, Lulic I. CPR PRO® device reduces rescuer fatigue during continuous chest compression cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A randomized crossover trial using a manikin model. J Emerg Med. 2013;45:570–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeung J, Davies R, Gao F, Perkins GD. A randomised control trial of prompt and feedback devices and their impact on quality of chest compressions-a simulation study. Resuscitation. 2014;85:553–9. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gruber J, Stumpf D, Zapletal B, Neuhold S, Fischer H. Real-time feedback systems in CPR. Trends Anaesth Crit Care. 2012;2:287–94. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ameryoun A, Meskarpour-Amiri M, Dezfuli-Nejad ML, Khoddami-Vishteh H, Tofighi Sh. The assessment of inequality on geographical distribution of non-cardiac intensive care beds in Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2011;40:25–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Y, Huang Z, Li H, Zheng G, Ling Q, Tang W, et al. CPR feedback/prompt device improves the quality of hands-only CPR performed in manikin by laypersons following the 2015 AHA guidelines. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36:1980–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guenther SPW, Schirren M, Boulesteix AL, Busen H, Poettinger T, Pichlmaier AM, et al. Effects of the Cardio First AngelTM on chest compression performance. Technol Health Care. 2018;26:69–80. doi: 10.3233/THC-170862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davis TL, Hoffman A, Vahedian-Azimi A, Brewer KL, Miller AC. A comparison of commercially available compression feedback devices in novice and experienced healthcare practitioners: A prospective randomized simulation study. Med Devices Sensors. 2018;1:e10020. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goharani R, Vahedian-Azimi A, Farzanegan B, Bashar FR, Hajiesmaeili M, Shojaei S, et al. Real-time compression feedback for patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest: A multi-center randomized controlled clinical trial. J Intensive Care. 2019;7:5. doi: 10.1186/s40560-019-0357-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beckers SK, Skorning MH, Fries M, Bickenbach J, Beuerlein S, Derwall M, et al. CPREzy improves performance of external chest compressions in simulated cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2007;72:100–7. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bielski A, Iskrzycki Ł, Gaweł W, Wieczorek W, Kamińska H, Smereka J, et al. CPREzy chest compression feedback device use by lifeguards: A randomized crossover trial. Anestezjol I Ratow. 2018;12:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Noordergraaf GJ, Drinkwaard BW, van Berkom PF, van Hemert HP, Venema A, Scheffer GJ, et al. The quality of chest compressions by trained personnel: The effect of feedback, via the CPREzy, in a randomized controlled trial using a manikin model. Resuscitation. 2006;69:241–52. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Buléon C, Parienti JJ, Halbout L, Arrot X, De Facq Régent H, Chelarescu D, et al. Improvement in chest compression quality using a feedback device (CPRmeter): A simulation randomized crossover study. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:1457–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Buléon C, Delaunay J, Parienti JJ, Halbout L, Arrot X, Gérard JL, et al. Impact of a feedback device on chest compression quality during extended manikin CPR: A randomized crossover study. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:1754–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.05.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Calvo-Buey JA, Calvo-Marcos D, Marcos-Camina RM. Randomised study of the relationship between the use of CPRmeter® device and the quality of chest compressions in a simulated cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Enferm Intensiva. 2016;27:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.enfi.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Delaunay J, Buléon C, Halbout L, Arrot X, Fellahi JL, Hanouz JL, et al. Evaluation in simulation of the impact on the quality of the external cardiac massage of a guiding tool, the CPRmeter®, during a prolonged resuscitation. Prospective randomized study. Anesth Reanim. 2015;1:A273–4. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Duwat A, Akinbusoye O, Hubert V, Petiot S, Mahjoub Y, Dupont H. Impact of using CPRmeter® on the quality of chest compressions for paramedical resuscitation personnel. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2014;33(Suppl 2):A391–2. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iskrzycki L, Smereka J, Rodriguez-Nunez A, Barcala Furelos R, Abelarias Gomez C, Kaminska H, et al. The impact of the use of a CPRMeter monitor on quality of chest compressions: A prospective randomised trial, cross-simulation. Kardiol Pol. 2018;76:574–9. doi: 10.5603/KP.a2017.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yuksen C, Prachanukool T, Aramvanitch K, Thongwichit N, Sawanyawisuth K, Sittichanbuncha Y. Is a mechanical-assist device better than manual chest compression? A randomized controlled trial. Open Access Emerg Med. 2017;9:63–7. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S133074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grassl K, Leidel BA, Stegmaier J, Bogner V, Huppertz T, Kanz KG. Cardiac massage in the context of the amateur resuscitation. Notfall Rettungsmed. 2009;12:117–22. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pozner CN, Almozlino A, Elmer J, Poole S, McNamara D, Barash D. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation feedback improves the quality of chest compression provided by hospital health care professionals. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:618–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Al-Jeabory M, Wieczorek W, Kaminska H, Nadolny K, Ladny JR, Szarpak L. Influence of CPR feedback device on chest compression quality. Pilot study. Anestezjol i Ratow. 2017;11:363–7. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grassi L, Babini G, Semeraro F, Scapigliati A, Luciani A, Novelli D, et al. The impact of a CPR feedback device on the quality of chest compressions performed by the attendees to Italian Resuscitation Council annual congress. Resuscitation. 2016;106:e19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Majer J, Madziala A, Dabrowska A, Dabrowski M. The place of TrueCPR feedback device in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Should we use it? A randomized pilot study. Disaster Emerg Med J. 2018;3:131–6. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Akbuga Ozel B, Ozel G, Mamak Ekinci E, Goger B, Delikanli C, Ersoy E, et al. Comparison of standard CPR and CPR feedback methods in terms of the effectiveness of chest compressions during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A randomized controlled study. Emerg Med J. 2016;33:917–7. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bydzovsky J. Influence of feedback devices on CPR provided by nurses. Resuscitation. 2015;96:72. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dixon M, Montgomery A, Howard J. Do mechanical CPR feedback devices improve the quality of chest compressions on simulated patients in a hospital bed. Resuscitation. 2010;81:S11. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schachinger F, Voittl J, Bsuchner P, Stumpf D, Zapletal B, Greif R, et al. Activation time while using stand-alone feedback devices during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A randomised simulation study. Resuscitation. 2013;84:S19. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schachinger F, Voitl J, Zapletal B, Greif R, Stumpf D, Nierscher FJ, et al. Comparison of standard BLS and the use of CPR feedback devices assessing the new parameter Effective Compression Ratio (ECR): A randomised simulation study. Resuscitation. 2013;84:S3. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zapletal B, Greif R, Stumpf D, Nierscher FJ, Frantal S, Haugk M, et al. Comparing three CPR feedback devices and standard BLS in a single rescuer scenario: A randomised simulation study. Resuscitation. 2014;85:560–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cohen TJ, Goldner BG, Maccaro PC, Ardito AP, Trazzera S, Cohen MB, et al. A comparison of active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation with standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation for cardiac arrests occurring in the hospital. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1918–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312233292603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vahedian-Azimi A, Bashar FR, Miller AC. A comparison of CPR with standard manual compressions versus compressions with real-time audio-visual feedback: A randomized controlled pilot study. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2020;10:32–7. doi: 10.4103/IJCIIS.IJCIIS_84_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kirkbright S, Finn J, Tohira H, Bremner A, Jacobs I, Celenza A. Audiovisual feedback device use by health care professionals during CPR: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised and non-randomised trials. Resuscitation. 2014;85:460–71. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang SA, Su CP, Fan HY, Hou WH, Chen YC. Effects of real-time feedback on cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality on outcomes in adult patients with cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2020;155:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1.Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:383–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hardy RJ, Thompson SG. A likelihood approach to meta-analysis with random effects. Stat Med. 1996;15:619–29. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960330)15:6<619::AID-SIM188>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lin L, Chu H, Hodges JS. Alternative measures of between-study heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Reducing the impact of outlying studies. Biometrics. 2017;73:156–66. doi: 10.1111/biom.12543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Harbord RM, Egger M, Sterne JA. A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat Med. 2006;25:3443–57. doi: 10.1002/sim.2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–63. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Merchant RM, Berg RA, Yang L, Becker LB, Groeneveld PW, Chan PS. Hospital variation in survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000400. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Steinberg SM. Cultural and religious aspects of palliative care. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2011;1:154–6. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.84804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Meaney PA, Bobrow BJ, Mancini ME, Christenson J, de Caen AR, Bhanji F, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality: [corrected] improving cardiac resuscitation outcomes both inside and outside the hospital: A consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128:417–35. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829d8654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sarrafzadegan N, Mohammmadifard N. Cardiovascular disease in Iran in the last 40 years: Prevalence, mortality, morbidity, challenges and strategies for cardiovascular prevention. Arch Iran Med. 2019;22:204–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Curran R, Sorr S, Aquino E. Potential wrist ligament injury in rescuers performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2013;6:123–5. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.110776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Perkins GD, Augré C, Rogers H, Allan M, Thickett DR. CPREzy: An evaluation during simulated cardiac arrest on a hospital bed. Resuscitation. 2005;64:103–8. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]