Abstract

Background

Pediatric emergency physicians complete either a pediatric or emergency residency before fellowship training. Fewer emergency graduates are pursuing a pediatric emergency fellowship during the past decade, and the reasons for this decrease are unclear.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to explore emergency residents' incentives and barriers to pursuing a fellowship in pediatric emergency medicine (PEM).

Methods

This was a cross‐sectional survey‐based study. In 2016, we emailed the study survey to all Emergency Medicine Residents' Association (EMRA) members. Survey questions included respondents' interest in a PEM fellowship and perceived incentives and barriers to PEM.

Results

Of 6620 EMRA members in 2016, 322 (5.0%) responded to the survey. Respondents were 59.6% male, with a mean age of 30.6 years. A total of 105 respondents (32.6%) were in their first year of emergency medicine residency, 92 (28.6%) were in their second year, 77 (23.9%) were in their third year, and 48 (14.9%) were in their fourth or fifth year. A total of 102 (31.8%) respondents planned to pursue fellowship training, whereas 120 (37.4%) were undecided. A total of 140 (43.8%) respondents reported considering a PEM fellowship at some point. Among these respondents, the most common incentives for PEM fellowship were (1) a desire to improve pediatric care in community emergency departments (86, 26.7%), (2) to develop an academic focus (54, 16.8%), and (3) because a mentor encouraged a PEM fellowship (40, 12.4%). A perceived lack of financial benefit (142, 44.1%) and length of PEM fellowship training (89, 27.6%) were the most commonly reported barriers.

Conclusion

In a cross‐sectional survey of EMRA members, almost half of the respondents considered a PEM fellowship. PEM leaders who want to promote emergency medicine to pediatric emergency residents will need to leverage the incentives and mitigate the perceived barriers to a PEM fellowship to increase the number of emergency residency applicants.

Keywords: Emergency Resident, Pediatric Emergency Fellowship

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background

Pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) is a relatively young offshoot of pediatrics and emergency medicine. Pediatric emergency physicians most commonly train in pediatrics before fellowship, with a small subset completing an emergency medicine residency. 1 , 2 Studies have demonstrated that only 5% of PEM faculty are emergency medicine trained. 3 , 4 Moreover, although the number of emergency resident graduates has increased by 1500 during the past 5 years, and the number of PEM fellowship positions has increased by 20, even fewer emergency graduates are pursuing a PEM fellowship. 5 , 6 , 7 Historically, emergency graduates have made up 15% of PEM fellows. More recent studies have demonstrated that 8% of current PEM fellows completed an emergency medicine residency. 3 , 4 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10

1.2. Importance

The current state of pediatric emergency care reflects an unusual dichotomy. Nearly all pediatric emergency physicians train in children's hospitals, where most scholarly work in PEM originates, whereas clinicians in general or community emergency departments (ED) provide the vast majority of emergency care to children in the United States. 11 , 12 , 13 Economically, it is infeasible for these EDs to employ a pediatrician or a pediatric emergency physician, as the pediatric volume alone is insufficient to support a physician who can only take care of children. Emergency‐trained pediatric emergency physicians are able to lead pediatric readiness efforts, research, quality improvement, and continuing educational programs in general and community EDs while working without clinical limitations based on patient age. 14 , 15 , 16

1.3. Objectives

There are currently no studies describing emergency resident interest in PEM fellowships, including perceived incentives and barriers. The objective of this study is to address this gap in the literature by completing a survey‐based study of emergency resident interest in PEM fellowships, with a focus on perceived incentives and barriers to PEM motivations for and barriers to pursuing fellowship training in PEM.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and subjects

This was a cross‐sectional survey of all emergency residents. We emailed the study survey to all resident members of the Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association (EMRA) for the year 2016. We administered the surveys using the online survey platform Survey Monkey Pro, including automated survey response and data tabulation. The institutional review board at the Olive View Medical Center and the EMRA Board of Directors both approved the study protocol before commencement.

2.2. Survey design

A multi‐institutional panel of emergency physicians, pediatric emergency physicians, and pediatricians designed the survey. The survey consisted of (1) basic demographic and geographic information aligned with the American Board of Emergency Medicine Report on Residency Training Information 6 ; (2) questions regarding future practice goals and post‐residency training, including interest in PEM fellowship; and (3) perceived incentives and barriers to PEM fellowships.

We drafted a list of potential incentives and barriers to PEM fellowships a priori based on the panel's extensive experience with emergency residents and PEM fellowship applicants. Next, a test group of 5 emergency residents completed the survey and provided feedback on content, ease of completion, and organization. Then, the research committee of the EMRA provided feedback on the revised survey. Finally, we converted the survey into an electronic format for data collection, and an independent editor reviewed its final form for grammatical accuracy (see Supplementary Material for the survey questions).

2.3. Survey administration

We distributed the survey to all members of EMRA via email in the spring of 2016. We sent an initial survey request and 2 follow‐up reminders through the EMRA email list‐serve. Use of the list‐serve allowed us to protect member confidentiality, and no personal information was recorded from the respondents. There was no participant incentive for survey completion.

2.4. Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize the response data. We used Stata/IC 14.2 (College Station, TX) for all analyses and graphical displays.

3. RESULTS

Of 6620 resident members of EMRA in 2016, 320 (5.0%) completed the survey. Missing data were rare; demographic data were missing for 2 respondents.

The Bottom Line

Pediatric emergency medicine is a pediatric‐dominant subspecialty where fewer emergency graduates are pursuing fellowship training. In this survey‐based study of more than 300 emergency residents, nearly half reported some interest in a pediatric emergency medicine fellowship. The investigators identified specific incentives and disincentives to inform efforts to increase emergency medicine resident pursuit of pediatric emergency medicine training.

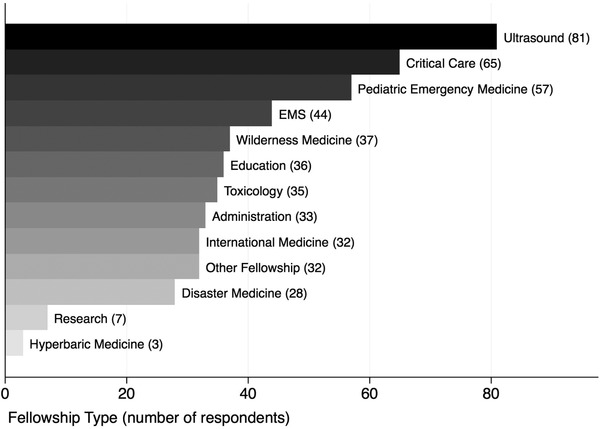

Table 1 describes the respondent demographics, residency program, and desired career characteristics, presented by the respondent‐reported interest in PEM fellowships. There was a relatively balanced division for emergency resident interest in PEM fellowships, with half of the respondents reporting that they were unsure about PEM fellowships and half reporting either some interest (29%) or no interest (20%). Respondents most commonly reported fellowship interests were ultrasound, critical care, and PEM (Figure 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of survey respondents

| Considered PEM, n = 140 | Did not consider PEM, n = 180 | Total, n = 322 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (range) | 30.6 (25–46) | 30.5 (26–40) | 30.6 (25–46) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 80 (58.0) | 110 (61.5) | 190 (59.6) |

| Region, n (%) | |||

| Mid‐Atlantic | 9 (6.4) | 13 (7.3) | 22 (6.9) |

| Midwest | 42 (30.0) | 47 (26.4) | 89 (27.8) |

| Northeast | 37 (26.4) | 74 (41.6) | 113 (35.3) |

| South | 14 (10.0) | 17 (9.6) | 31 (9.7) |

| South East | 16 (11.4) | 8 (4.5) | 24 (7.5) |

| West | 16 (11.4) | 17 (9.6) | 33 (10.3) |

| International | 6 (4.3) | 2 (1.1) | 8 (2.5) |

| Residency type, n (%) | |||

| 3 years | 91 (65.0) | 103 (57.2) | 195 (60.6) |

| 4 years | 36 (25.7) | 67 (37.2) | 104 (32.3) |

| Othera | 13 (9.3) | 10 (5.6) | 23 (7.1) |

| Year in training, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 56 (40.0) | 48 (26.7) | 105 (32.6) |

| 2 | 30 (21.4) | 61 (33.89) | 92 (28.6) |

| 3 | 29 (20.7) | 48 (26.7) | 77 (23.9) |

| 4 | 12 (8.6) | 13 (7.2) | 25 (7.8) |

| Other | 13 (9.3) | 10 (5.6) | 23 (7.1) |

| Future practice setting, n (%) | |||

| Academic | 27 (19.6) | 43 (23.9) | 71 (22.2) |

| Academic and community | 67 (48.6) | 87 (48.3) | 155 (48.4) |

| Community | 43 (31.2) | 48 (26.7) | 91 (28.4) |

| Other | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (0.9) |

| Anticipate applying for fellowship, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 41 (29.5) | 59 (32.8) | 102 (31.8) |

| No | 29 (20.9) | 70 (38.9) | 99 (30.8) |

| Unsure | 69 (49.6) | 51 (28.3) | 120 (37.4) |

There were 23 respondents who were from “other” program lengths, several of whom identified as in combined emergency medicine/pediatrics and emergency medicine/internal medicine residency programs. None of those who self‐identified as in a combined emergency medicine/pediatrics program were interested in a PEM fellowship, but this represented only 7 of these respondents, thus we included these 23 “other” respondents within the reported data. PEM, pediatric emergency medicine.

FIGURE 1.

Number of respondents considering specific fellowships. EMS, emergency medical services

Almost half (140, 43.8%) of the respondents reported having considered a PEM fellowship at some points during residency. Among these residents, the most commonly reported incentives to PEM fellowships were the opportunity to improve pediatric emergency care in community EDs (26.7%), plans to have an academic niche in PEM (16.8%), and a mentor encouraging a PEM fellowship (12.4%; Table 2). Less than 10% of respondents with an interest in PEM reported a desire to work exclusively in academic pediatric EDs. Notably, several respondents reported considering PEM fellowships because of the desire for increased expertise with more complex pediatric patients. In free‐text comments, prominent themes included insecurity in the ability to care for sick children and satisfaction with working with a pediatric population (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Emergency residents’ reported incentives and barriers to considering a fellowship in pediatric emergency medicine

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Incentives | ||

| Improve pediatric care in the community emergency department | 86 | 26.7 |

| Have PEM as a niche in academic emergency medicine | 54 | 16.8 |

| Good mentorship from pediatric emergency physicians | 40 | 12.4 |

| Opportunity to work in an academic children's emergency department | 32 | 9.9 |

| Work only with pediatric patients | 15 | 4.7 |

| Entered emergency medicine planning on PEM fellowship | 11 | 3.4 |

| Interest in PEM research | 9 | 2.8 |

| Other | 25 | 7.8 |

| Barriers | ||

| No financial benefit | 142 | 44.1 |

| 2 or more years is undesirable | 89 | 27.6 |

| Enough pediatric education in general emergency medicine | 79 | 24.5 |

| Considering an alternative fellowship | 66 | 20.5 |

| PEM is dominated by pediatricians | 59 | 18.3 |

| Prefer adult patients | 54 | 16.8 |

| Do not like working with pediatric patients | 35 | 10.9 |

| Do not want to complete a fellowship | 24 | 7.5 |

| No access to PEM mentors | 17 | 5.3 |

| Other | 43 | 13.4 |

PEM, pediatric emergency medicine.

TABLE 3.

Select free‐text responses on incentives and barriers to pediatric emergency medicine fellowships

| Theme | Quote |

|---|---|

| Incentives |

“I love working with kids. They make my day happy.” “I feel pediatric training is a bit limited and I am least comfortable with kids.” “Fear my Peds training will be inadequate upon graduation.” |

| Barriers |

“I do not want to limit my scope of practice; I want to see children and adults in my practice.” “I think a lot of people I talk to realize that it is two more years of interest on student loans, two years less of practice, and no financial benefit to doing the fellowship. Not that money is the reason, but it does matter when you have massive loans, family responsibilities, etc.” “I loved adult EM pathology as well as PEM during sub‐Is. It is difficult though to truly consider another TWO years of training. I think that PEM fellowship for EM‐trained individuals should only be 1 year. The fact it is two additional years is a very large deterrent. We are the best at dealing with all types of critical patients and a year of focused training would give us adequate training for PEM, especially compared to those who are pediatric residency trained.“ “Multiple reasons. Not only is there no financial incentive, there is probably a financial disincentive to work in Peds. There is little opportunity to perform high quality research. The adult world is loaded with quality RCTs, unfortunately not true for Peds. Most Peds EM docs that I have work with just don't seem to function like an ED doc, but more like primary care physicians… There is little pressure for flow compared to the adult world…. I feel like some of the Peds crowd looks down at "adult" EM docs. EM residency can train EM physicians to safely take care of most pediatric patients. The chronically ill patients with complex histories that we probably shouldn't be taking care of generally don't present to community sites and if they do we will be transferring them.” “During medical school, I was discouraged from proceeding with PEM fellowship after going through EM first. It was the philosophy of PEM people I spoke with that PEM academics "prefer" Peds ‐> PEM rather than EM ‐> PEM.” “PEM is lower acuity in general.” “I find the pace of most pediatric emergency departments to be way too slow. I can't see reason to take a pay cut for something that, to me, is less exciting.” “[The] atmosphere in pediatric ED is much different. Very little autonomy make[s] it boring as a resident. Pediatric EM docs practice differently.” |

Among the 140 respondents who indicated an interest in PEM at any point during residency, the most common reasons for loss of interest in PEM were financial concerns (44.1%), length of fellowship training (27.6%), and adequate pediatric exposure in residency (24.5%; Table 2). Nearly 20% of these respondents indicated that the high proportion of pediatrics‐trained pediatric emergency practitioners was a reason to not consider a PEM fellowship (18.3%). From the free‐text responses, prominent themes for not considering a PEM fellowship were the perception that the fellowship would limit the scope of practice, concern for losing the adult emergency medicine knowledge and skill while in the fellowship, lower patient acuity in PEM, and poor experience during dedicated to PEM. Furthermore, multiple respondents commented on the differences in patient flow in the pediatric ED and different practice styles (Table 3).

4. LIMITATIONS

The most prominent limitation is the small response rate. Small response rates are common in this type of research. Although the response rate was only 5.3%, the sample size was relatively large at 322 respondents. As our interest was in emergency residents with any potential for interest in a PEM fellowship, we likely succeeded in identifying a relatively representative sample of those residents; emergency residents with stronger interest in or dislike of PEM may actually be overrepresented in our sample. Moreover, some respondent demographics were similar to published distributions for emergency medicine training programs. 6 An additional limitation is that the survey questions were generally fixed, with no opportunity to directly question respondents to clarify and expand on the responses. We included free‐text options to address this limitation, and many of the responses included notable free‐text responses. To fully characterize emergency medicine incentives and barriers to PEM, further qualitative research is needed.

5. DISCUSSION

Our study primarily suggests that, although a large number of emergency residents consider PEM fellowships, very few pursue it. In 2018, there were 40 emergency medicine–trained fellows in PEM fellowships in the United States of 519 total PEM fellows (7.7%), down from 53 emergency medicine–trained fellows among 474 total PEM fellows in 2015 (11.1%). 6 This apparent decline is consistent with data going back to 2011. 7 , 9 We believe the low and declining number of emergency medicine–trained residents is a problem, for emergency medicine and for PEM, as the vast majority of pediatric emergency care occurs outside of PEM settings. Many patient conditions common to emergency medicine are also seen in PEM, for example, trauma and sepsis, and PEM settings could benefit from the experience and expertise of emergency medicine–trained residents becoming pediatric emergency physicians.

Emergency residents most commonly reported lack of financial incentive as a barrier to PEM fellowships. Residents could have indicated this barrier for several reasons, including the inability to enter directly into the workforce if undertaking a fellowship or the perception of a lower salary in PEM. The only available financial data, however, is limited to academic settings, where the average, unadjusted emergency medicine salary was $22,047 lower for emergency medicine to PEM physicians . 17 Further investigation into salary differences is warranted to aid emergency residents in making more informed decisions regarding PEM fellowships.

The second most commonly reported barrier was the length of fellowship training, either 2 or 3 years depending on the individual PEM program, which is longer than many other fellowship options for emergency residents. This barrier is fixed to some degree and should be taken into consideration when recruiting PEM fellows. Emergency medicine and PEM leaders could address this barrier through the creation of combined emergency residency–PEM fellowship programs and more readily available options, including moonlighting in emergency medicine during PEM fellowships or offering a 2‐year PEM track.

Prominent themes from the free‐text comments included the differences in practice between pediatric and emergency residencies, the perception that PEM is primarily a field composed of pediatricians, and a perception of alienation of emergency physicians in PEM. All 3 issues are additional potential barriers to emergency residents pursuing PEM fellowships. The perceived difference between emergency medicine and PEM cultures is likely explained by PEM developing from 2 distinct specialties. Collaboration between emergency and pediatric physicians could help to address this barrier. 18 Collaboration could include joint local, regional, and national conferences and educational opportunities, more PEM research and quality improvement initiatives that include general EDs and emergency‐trained researchers, and collaborative efforts of the combined American Board of Pediatrics/American Board of Emergency Medicine Pediatric Emergency Medicine sub‐board.

Many of the reported barriers to PEM are modifiable, and the incentives easily promoted. Our data provide an initial opportunity for emergency and PEM leaders to gain insight into the reasons for declining emergency medicine representation in PEM. Moreover, we hope that our results prompt leaders from both groups to consider ways to encourage emergency residents to pursue fellowships in PEM. Although our survey was intentionally brief to encourage participation, further investigation of specific barriers and incentives should be considered given the broad nature of these topics and the declining rates of emergency resident participation in PEM. Investigation of the components of good mentorship, educational comfort with pediatrics in emergency residency, cultural differences between emergency medicine and pediatrics, and potential financial loss may further elucidate fellowship decisions.

In summary, this is the first published study to explore emergency resident barriers and incentives to PEM fellowships. Among >300 emergency residents, nearly half reported some interest in PEM fellowships. Our study provides some initial insight into the factors that influence the decision to pursue a PEM fellowship. Further research into the specific factors leading to the successful matriculation of emergency residents into PEM fellowships as well as the influences on the decision to pursue a fellowship versus an academic or community position should be considered.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jessica J. Wall, Emily MacNeill, Sean M. Fox, Maybelle Kou, and Paul Ishimine contributed to the study concept and design. Jessica J. Wall and Emily MacNeill contributed to the acquisition of the data. Jessica J. Wall and Paul Ishimine contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. Jessica J. Wall contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. Jessica J. Wall, Emily MacNeill, Sean M. Fox, Maybelle Kou, and Paul Ishimine contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. Jessica J. Wall and Paul Ishimine contributed to the statistical expertise.

Supporting information

Supplementary information

Biography

Jessica J. Wall, MD, MPH, is Clinical Assistant Professor Emergency Medicine and Pediatrics at the University of Washington and Assistant Medical Director of Pediatrics, Airlift Northwest.

Wall JJ, MacNeill E, Fox SM, Kou M, Ishimine P. Incentives and barriers to pursuing pediatric emergency medicine fellowship: A cross‐sectional survey of emergency residents. JACEP Open 2020;1:1505–1511. 10.1002/emp2.12234

Presentation: A prior abstract of these results were presented at the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine Annual Meeting, May 19, 2017.

Funding and support: By JACEP Open policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article as per ICMJE conflict of interest guidelines (see www.icmje.org). The authors have stated that no such relationships exist.

Supervising Editor: Benjamin T. Kerrey, MD, MS.

REFERENCES

- 1. Smith‐Coggins R, Baren JM, Counselman FL, et al. American Board of Emergency Medicine report on residency training information (2012‐2013), American Board of Emergency Medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(5):584‐592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Smith‐Coggins R, Marco CA, Baren JM, et al. American Board of Emergency Medicine report on residency training information (2014‐2015). Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(5):584‐594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abel KL, Nichols MH. Pediatric emergency medicine fellowship training in the new millennium. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19(1):20‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murray ML, Woolridge DP, Colletti JE. Pediatric emergency medicine fellowships: faculty and resident training profiles. JEM. 2009;37(4):425‐429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marco CA, Baren JM, Beeson MS, et al. American Board of Emergency Medicine Report on Residency Training Information (2015‐2016). Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67(5):654‐666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Althouse LA, Stockman JA. Pediatric workforce: a look at pediatric emergency medicine data from the American Board of Pediatrics. J Pediatr. 2006;149(5):600‐602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nelson LS, Keim SM, Baren JM, et al. American Board of Emergency Medicine Report on Residency and Fellowship Training Information (2017‐2018). Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(5):636‐648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Number of Accredited Programs Academic Year 2015‐2016 . 2016. Report accessed from https://apps.acgme.org/ads/Public/Reports/Report/3. Accessed November 1, 2018.

- 9. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Number of Accredited Programs Academic Year 2017‐2018 . 2018. Report accessed from https://apps.acgme.org/ads/Public/Reports/Report/3. Accessed November 1, 2018.

- 10. National Resident Matching Program . National Resident Matching Program, Results and Data: Specialties Matching Service 2015 Appointment Year. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Center for Disease Control and Prevention . National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2013 emergency department summary tables. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2013_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2018.

- 12. Schappert SM, Bhuiya F. Availability of pediatric services and equipment in emergency departments: United States, 2006. Natl Health Stat Report. 2012;(47):1‐21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Center for Disease Control . National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2015 Emergency Department Summary Tables . 2018. Accessed from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/web_tables.htm with direct link to pdf at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2015_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2018.

- 14. Remick K, Gausche‐Hill M, Joseph MM, et al. Pediatric readiness in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(6):e123‐e136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ames SG, Davis BS, Marin JR, et al. Emergency department pediatric readiness and mortality in critically ill children. Pediatrics. 2019;144(3):e20190568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ray KN, Olson LM, Edgerton EA, et al. Access to high pediatric‐readiness emergency care in the United States. J Pediatr. 2018;194:225–232.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. AAAEM‐AACEM Faculty Salary Survey results. https://www.saem.org/docs/default-source/aaaem/fy15-aaaem-aacem-faculty-salary-survey-results.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed November 1, 2018.

- 18. Ishimine P, Adelgais K, Barata I, et al. Executive summary: the 2018 Academic Emergency MedicineConsensus Conference: aligning the pediatric emergency medicine research agenda to reduce health outcome gaps. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;25(12):1317‐1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information