Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a malignant tumor with a fairly poor prognosis (5-year survival of less than 50%). Using sorafenib, the only food and drug administration (FDA)-approved drug, HCC cannot be effectively treated; it can only be controlled at most for a couple of months. There is a great need to develop efficacious treatment against this debilitating disease. Glypican-3 (GPC3), a member of the glypican family that attaches to the cell surface by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor, is overexpressed in HCC cases and is elevated in the serum of a large proportion of patients with HCC. GPC3 expression contributes to HCC growth and metastasis. Furthermore, several different types of antibodies targeting GPC3 have been developed. The aim of this review is to summarize the current literatures on the GPC3 expression in human HCC, molecular mechanisms of GPC3 regulation and antibodies targeting GPC3.

Keywords: Glypican-3 (GPC3), Wnt signaling, Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

1. Introduction

Liver cancer is the fourth most common malignancy worldwide and was the ninth leading cause of cancer death in 2017.1,2 The most common form of primary liver cancer is hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Viral hepatitis such as hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis B virus (HBV) and alcohol hepatitis/cirrhosis account for the majority of HCC cases. Incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is rising and has also been associated with the development of HCC. Most HCC patients with symptoms present an advanced stage at diagnosis and surgery is the main treatment.3 Unfortunately, the outcomes are usually poor due to cancer metastasis and tumor recurrence after surgery. Multi-kinase inhibitors have been used to treat HCC.3 However, HCC can only be controlled, at most, for a couple of months. Thus, there is an urgent demand for early diagnosis and the development of an effective treatment for this debilitating disease. In recent years, studies have shown that glypican-3 (GPC3) is specifically expressed in HCC and its expression is associated with poor prognosis, revealing that GPC3 is a critical molecular target in HCC and potentially can be a therapeutic target for HCC treatment.

2. GPC3 expression and biological functions in HCC

2.1. GPC3 molecular structures

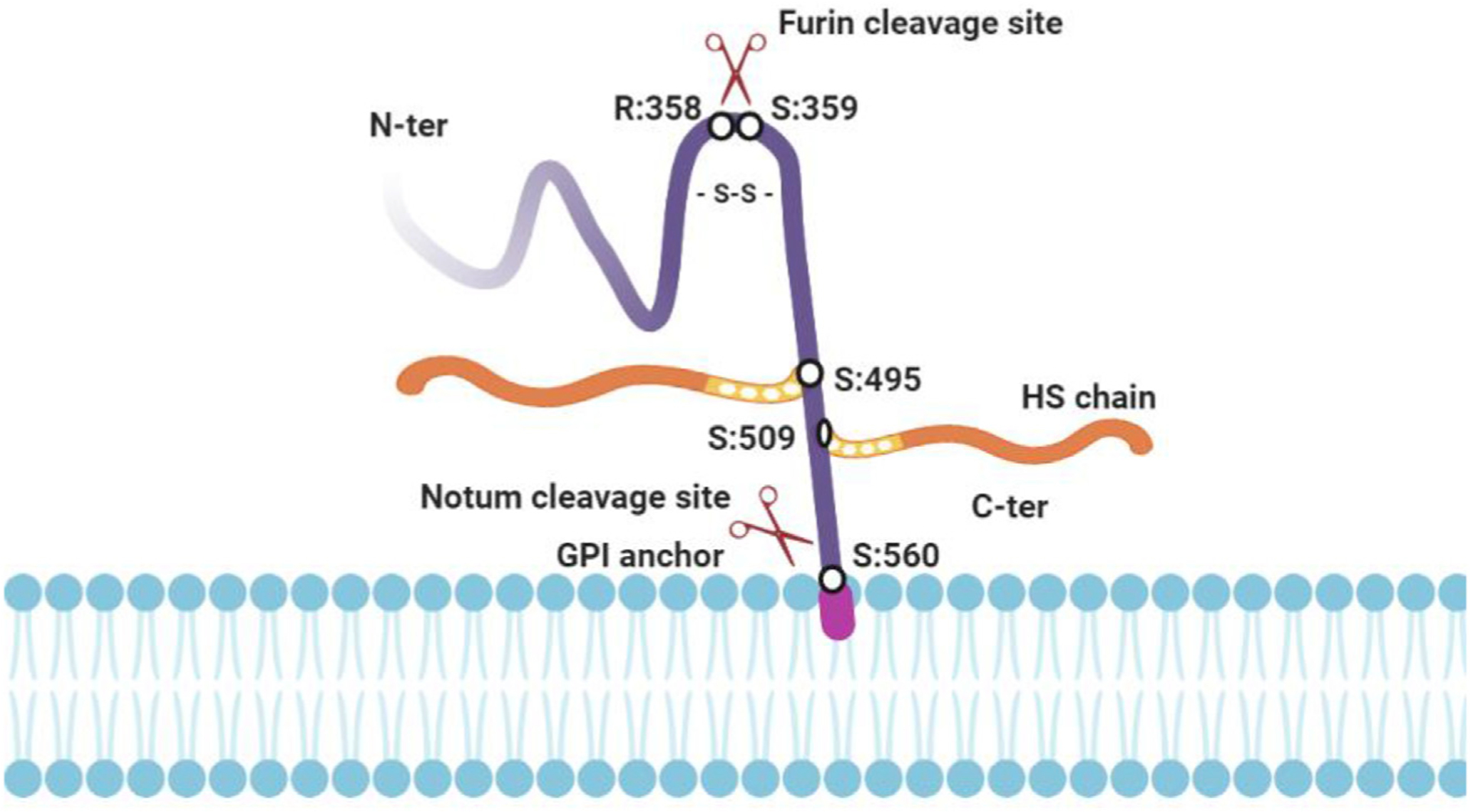

GPC3, a 70 kDa protein, is encoded by the gene GPC3 located on the X chromosome (Xq26.2) and consists of 11 exons.4,5 GPC3 is a member of the glypican family, which has a basic structure consisting of a core protein and a heparan sulfate chain, and binds to the cell membrane via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor.6,7 GPC3 has a cleavage site between Arg358 and Ser359 for Furin protease (Fig. 1). Cleavage by furin results in a 40-kDa N-terminal subunit and a 30-kDa C-terminal subunit. These two subunits can be linked by a disulfide bond. Two heparan sulfate side chains occur near the C-terminal of GPC3 (Ser495 and Ser509). Ser560 of GPC3 inserts into the lipid bilayer and anchors the protein to the bilayer by phosphatidylinositol.8 In addition, GPC3 can be released from the cell surface to the extracellular environment after cleavage by Notum, an extracellular lipase that releases GPC3 by cleaving the GPI anchor.9,10

Fig. 1. The structure of GPC3 protein.

GPC3 consists of a core protein and a heparan sulfate chain. It binds to the cell membrane via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor. GPC3 has a cleavage site between Arg358 and Ser359 for Furin protease. Cleavage by furin results in a 40-kDa N-terminal subunit and a 30-kDa C-terminal subunit. These two subunits can be linked by a disulfide bond. Two heparan sulfate (HS) side chains occur near the C-terminal of GPC3 (Ser495 and Ser509). Ser560 of GPC3 inserts into the lipid bilayer and anchors the protein to the bilayer by phosphatidylinositol. GPC3 can be released from the cell surface into the extracellular environment after cleavage by Notum, an extracellular lipase that releases GPC3 by cleaving the GPI anchor. Fig. 1 is created using tools in BioRender.com. Abbreviations: GPC3, Glypican-3; GPI, glycosylphosphatidylinositol; HS, heparan sulfate.

2.2. Biological functions of GPC3

GPC3 can both negatively and positively regulate cell growth depending on the cell type. GPC3 is highly expressed in mesodermal embryonic tissues. Deletion of the GPC3 gene is involved in the pathogenesis of Simpson-Golabi-Behmel overgrowth syndrome.11,12 In addition, Pellegrini et al.13 showed that the interaction of GPC3 with IGF2 can reduce IGF2-mediated growth in vivo. This evidence indicates that GPC3 negatively regulates embryonic and fetal development. In addition, GPC3 is a negative transcriptional regulator and tumor suppressor that inhibits the growth of breast, ovary, and lung cancer cells.14–17

On the other hand, GPC3 is highly expressed in 70–100% of HCCs.18 GPC3 interacts with Wnt to facilitate Wnt/Frizzled binding for HCC growth.19,20 Knocking down the expression of GPC3 in cell culture reduces Yap signaling.21 Interestingly, soluble GPC3 proteins (GPC3DGPI) act in a dominantly negative form, competing with endogenous GPC3 to inhibit HCC cell growth likely by neutralizing GPC3 binding molecules.22 These studies revealed the proliferative effect of GPC3 in HCC.

2.3. GPC3 expression in HCC tissue

A study by Hsu et al.18 in 1997 showed that MXR7 mRNA, later renamed GPC3, was detected in 143 of 191 (74.8%) HCC tissues. In Zhu et al.’s study,23 northern blot analysis indicated the 2.3 kb GPC3 transcript was detected at high levels in 67% of cases and moderate levels in 17% of cases. In contrast, GPC3 mRNA was either low or not detected in normal livers, focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH), and cirrhotic livers. Densitometry analysis of northern blots indicated that HCC had 21.7-fold increases in GPC3 mRNA levels compared with that of normal livers, and 7.2-fold and 10.8-fold higher GPC3 mRNA expression than that in FNH and liver cirrhosis specimens, respectively.

Capurro et al.24 found that GPC3 protein was highly expressed in 72% (21/29) of HCCs, whereas it was undetectable in hepatocytes isolated from either healthy livers or livers with benign diseases. Consistent with this, Baumhoer et al.25 later confirmed the expression of GPC3 in the liver and other organs and tissues using tissue microarray technology. The immunohistochemical results showed that the expression of GPC3 was detected in 9.2% (11/119) of nonneoplastic liver specimens, 16% (6/38) of preneoplastic nodular liver lesions, and 63.6% (140/220) of HCCs.

2.4. GPC3 as a serum biomarker of HCC

Capurro et al.24 found that GPC3 serum level was significantly increased in 53% (18/34) of HCC patients, but not detectable in the serum of healthy and hepatitis patients. Chen et al.26 analyzed serum GPC3 in 1037 subjects, including 155 HCC patients, 180 with chronic hepatitis, 124 with liver cirrhosis, 442 with non-HCC cancer, and 136 healthy people. The ELISA results showed that the average level of serum GPC3 was 99.94 ± 267.2 ng/ml in HCC patients, which was higher than that of people who had chronic hepatitis (10.45 ± 46.02 ng/ml), liver cirrhosis (19.44 ± 50.88 ng/ml), non-HCC cancer (20.50 ± 98.33 ng/ml), and healthy controls (4.14 ± 31.65 ng/ml). Thus, serum GPC3 is potentially a diagnostic marker of HCC.

Qiao et al.27 determined the serum concentration of three tumor-markers, GPC3, Human-Cervical-Cancer-Oncogene, and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), in 189 cases (101 HCC, 40 cirrhosis, 18 hepatitis, and 30 healthy people). Each marker was evaluated for its diagnostic value. GPC3 was the best marker with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.892. Serum GPC3 levels at a cutoff value of 26.8 ng/ ml had a sensitivity and specificity for HCC diagnosis of 51.5% and 92.8%, respectively. Liu et al.28 showed that serum GPC3 levels were higher than 300 ng/L in 50% (7/14) of HCC patients with serum AFP levels of <100 μg/L.

3. GPC3 activates HCC oncogenic pathway

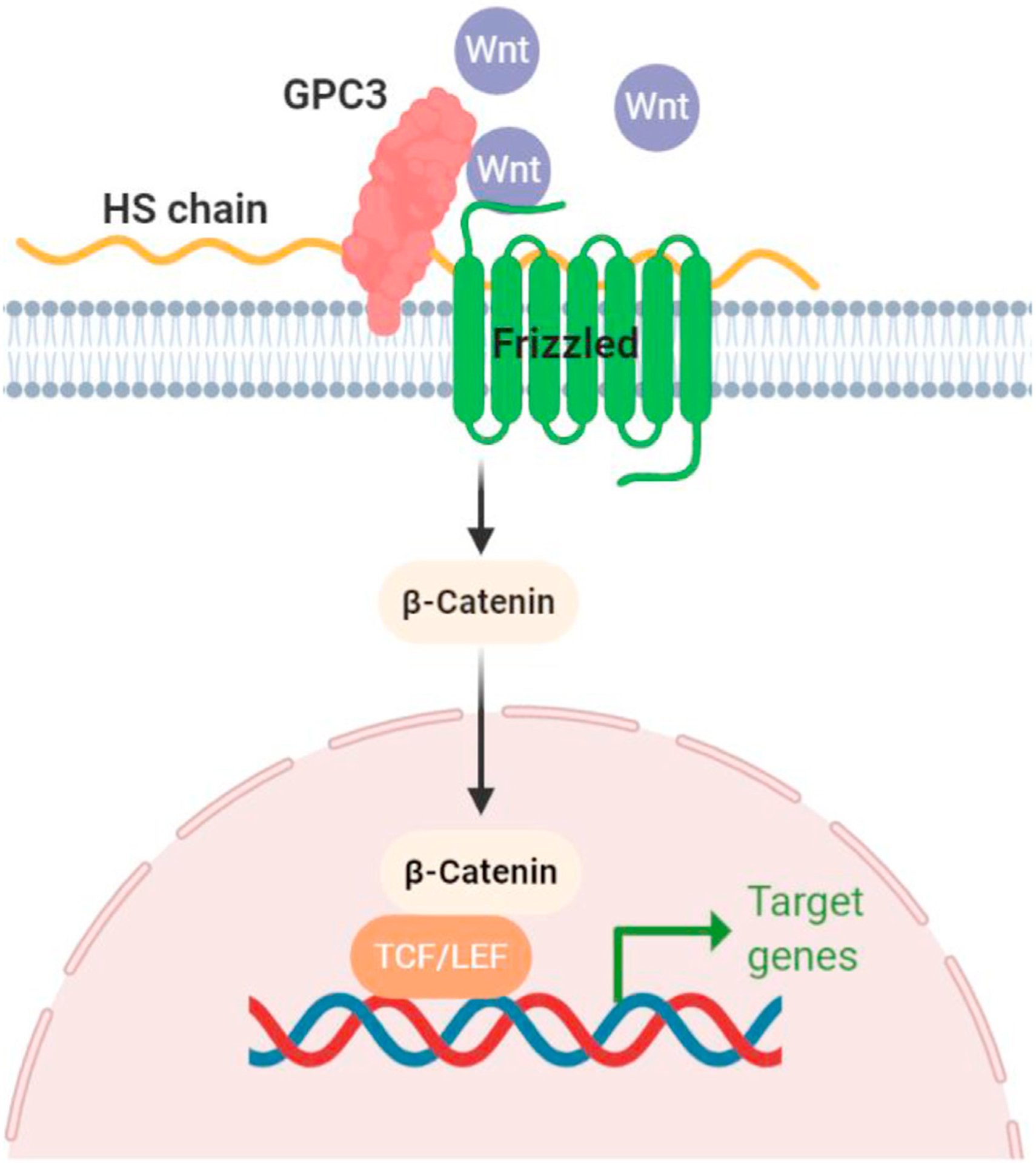

Oncogenic signaling pathways identified as being involved in the development of HCC included growth factor-related pathways such as insulin-like growth factor (IGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), fibroblast growth factors (FGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF); and cell differentiation-related pathways such as Wnt, Hedgehog and Notch signaling. Among these signaling pathways, activation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway is a common feature in HCC although the genetic pathogenesis of HCC is highly heterogeneous.29,30 Wnt signaling resulted in translocation of beta-catenin (β-catenin) into the nucleus to form complexes with T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) transcription factors and activates Wnt target gene expression (Fig. 2).31

Fig. 2. GPC3 and Wnt cell signaling.

GPC3 forms a complex with Wnt and activates Wnt signaling leading to the HCC growth. Fig. 2 is created using tools in Fig. 1 is created using tools in BioRender.com. Abbreviations: GPC3, Glypican-3; HS, heparan sulfate; TCF/LEF, T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor.

Membrane GPC3 can interact with several growth factors, such as Wnt, Hedgehogs, bone morphogenetic factors, and FGF to promote the binding of growth factors to their receptors. Capurro et al.19 showed that GPC3 stimulates Wnt signaling to promote HCC growth. Co-immunoprecipitation analysis revealed that GPC3 interacts with Wnts, and cell-binding assays confirmed that GPC3-expressing cells were capable of binding Wnt (Fig. 2).

The binding of GPC3-Wnt was further illustrated by Li et al.20 using structural analysis and functional evaluation. GPC3 binds Wnt to the cell surface via cysteine-rich hydrophobic groove in the N-lobe of GPC3 containing phenylalanine in position 41 (F41). Functional analysis shows that a residual F41 mutation on GPC3 inhibits the activation of β-catenin in vitro and reduces xenograft tumor growth compared with cells expressing wild-type GPC3 in nude mice.20 Lai et al.32 reported that GPC3-mediated activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in human HCCs could be enhanced by sulfatase 2 (SULF2). In the liver, SULF2 is an oncogenic protein that is overexpressed in 60% of HCC cell lines.33

Mechanistic studies revealed that GPC3 plays a role in the regulation of tumor microenvironment and cancer metastasis. Gao et al.34 showed that GPC3 was involved in HCC cell migration and motility through heparin sulfate chain-mediated cooperation with the HGF/Met pathway, knocking down GPC3 by using GPC3 gene-specific sh-RNA inhibited HCC cell migration and motility. Consistent with this, Montalbano et al.35 showed that the inhibition of GPC3 via siRNA resulted in the inhibition of cell migration and invasion. Qi et al.36 also showed that GPC3 regulates cell invasion and migration through the activation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a key tumor invasion process. Wu et al.37 further showed a clinical correlation in which elevated levels of GPC3 in HCC tumor tissues were positively correlated to the expression of the EMT-associated proteins and tumor vascular invasion. It was also found that GPC3 could regulate EMT of HCC cells by activating p-ERK1/2 signaling.37

4. Therapeutic antibodies against GPC3

Given the important role of GPC3 in HCC progression, several humanized antibodies (Ab) against GPC3 have been developed (Table 1).21,34,38–46 GC33, a murine monoclonal Ab specific for the C-terminal 30-kDa fragment of the human GPC3 was first produced by Nakano et al.38 To apply GC33 for clinical use, Nakano et al.39 generated humanized GC33 by complementarity-determining region grafting and stability optimization. In preclinical models of HCC, humanized GC33 at 5 mg/kg i.v. weekly could induce antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity against cancer cells and inhibit the growth of human GPC3-positive HCC in xenograft mouse models.39,40

Table 1.

Therapeutic antibodies targeting GPC3 in HCC.

| Antibody name | Antibody format | Antigen | Action on Wnt/β-catenin signaling | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC33 | mAb | C-terminal (524–563) | No | 33–40 |

| YP7 | scFv+Fc | C-terminal (511–560) | No | 41,42 |

| YP7 related antibodies | ||||

| YP7-PE38 | YP7 + immunotoxins | 43 | ||

| YP7-DC | YP7 + small molecules | 44 | ||

| YP7-PC | YP7 + small molecules | 44 | ||

| HN3 | VH-hFc | Conformation: both N- and C-terminal domains | Yes | 21 |

| HN3 related antibodies | ||||

| HN3-PE38 | HN3 + immunotoxins | 43 | ||

| HN3-mPE24 | HN3 + immunotoxins | 45 | ||

| ERY974 | bispecific antibody | GPC3 & CD3 | unknown | 46 |

| HS20 | mAb | Heparan sulfate | Yes | 34 |

Abbreviations: GPC3, Glypican-3; mAb, monoclonal antibody; scFv, single-chain variable fragment.

A phase I study was conducted to examine the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetic characteristics of GC33 in 20 patients with advanced HCC (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00746317).47 The primary objective was to determine the maximum tolerated dose of GC33 given intravenously at weekly intervals. A maximum tolerated dose was not reached as there were no dose-limiting toxicities up to the highest planned dose level. Mean half-life (t1/2) was 2.94, 3.46, 5.16, and 6.47 days, and mean total clearance was 1.62, 1.14, 0.799, and 0.784 L/days at 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg, respectively. The most common adverse events were fatigue (50%), constipation (35%), headache (35%), and hyponatremia (35%). NK cell numbers in plasma were reduced following GC33 administration, but no increased incidence of infection was observed. The study showed the well-tolerability of GC33 treatment. However, the completed phase II clinical trial conducted in 185 patients (121 received GC33 and 64 placebo) indicated that GC33 did not have a clinical benefit in advanced HCC, and its efficacy was likely promoted by the antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01507168).48,49

By immunizing mice with a GPC3 peptide (residues: 511–560), Phung et al.41 generated high affinity (Kd = 0.3 nM) anti-GPC3 mouse monoclonal Ab YP7. YP7 is highly specific for GPC3-expressing tumor cells and tissues and can detect low levels of GPC3 in ovarian clear cell carcinoma and melanoma cells. Furthermore, YP7 exhibits strong antitumor activity against HepG2 xenografts in mice. Zhang et al.42 also generated YP7 single-chain variable fragment (scFv) and successfully humanized YP7, while retaining the antitumor effects. Feng et al.21 further isolated HN3, a human heavy-chain variable domain antibody by phage display. HN3 has a high affinity (Kd = 0.6 nM) for cell-surface-associated GPC3 molecules by recognizing a conformational epitope that requires both the amino and carboxy terminal domains of GPC3. Unlike GC33 and YP7, HN3 directly inhibits proliferation of GPC3-positive cells and inhibits the growth of HCC xenograft tumors in nude mice. Mechanistically, HN3 induces cell cycle arrest at G1 phase through Yes-associated protein signaling. In addition to targeting the core protein of GPC3, Gao et al.34 developed a human monoclonal Ab against GPC3, which preferentially recognizes the heparan sulfate chains of GPC3. HS20 inhibits Wnt3a-dependent cell proliferation in vitro and HCC xenograft growth in nude mice. Furthermore, the heparan sulfate-targeting antibody HS20 inhibits HGF-induced motility.

To enhance anti-tumor effects of Ab, Gao et al.43 fused YP7 and HN3 to Pseudomonas exotoxin (PE38) and constructed a recombinant immunotoxin against GPC3. Immunotoxins are chimeric proteins that contain a bacterial or plant toxin along with an antibody that binds specifically to cancer cells.50 HN3-PE38 shows greater anti-tumor cytotoxicity than YP7-PE38 both in vitro and in vivo. The underlying mechanism of HN3-PE38 action involves the inhibition of Wnt3a-induced β-catenin and Yap signaling. Intravenous injection of HN3-PE38 as a single agent or in combination with irinotecan results in the regression of Hep3B and HepG2 xenografts in mice. However, the initial immunotoxin could only be used at a relatively low dose (<0.8 mg/kg) because PE38 had off-target toxicity and induced neutralizing antibodies in humans.51 To develop an anti-GPC3 immunotoxin for clinical use, Wang et al.45 fused HN3 to mPE24 constructing a mPE24-based immunotoxin. mPE24, a second generation PE fragment, has a link containing a furin-cleavage sequence,52 instead of domain II and domain III with seven mutations that suppress B cell epitopes.53 HN3-mPE24 has a high level of cytotoxicity to HCC cells and is found to have reduced side effects and good anti-tumor activity when used at high doses in mice.45 Fu et al.44 replaced PE38 with small molecule cytotoxins and developed antibody-drug conjugates. hYP7 was chosen to couple with Duocarmycin SA (alkylation subunit) and pyrrolobenzodiazepine dimer to construct two GPC3-specific antibody drug conjugates (ADCs) hYP7-DC and hYP7-PC, respectively. These two ADCs showed potency at picomolar concentrations against a panel of GPC3-positive HCC cell lines.

Additionally, by engaging immune cells to destroy tumor cells, Ishiguro et al.46 developed a bispecific antibody ERY974 that consisted of a common light chain but had two different heavy chains that both recognized a different protein, GPC3 or CD3.38 ERY974 exerted significant antitumor efficacy even against tumors with nonimmunogenic features. Treatment also appeared to be safe in monkeys.

5. Conclusion

GPC3 is specifically expressed in HCCs and can be found in HCC patient serum. Increased GPC3 can be considered as a sign of HCC progression. GPC3 can be used as a serum and histochemical marker for diagnosis of early-stage of HCC. Furthermore, GPC3 stimulates HCC growth through the activation of Wnt/b-catenin signaling pathway,32,54–57 which is the most frequently activated pathway in liver carcinogenesis.58 Thus, GPC3 makes an attractive target for the development of new therapeutic tools for HCC treatment. The application of targeting GPC3 to treat HCC deserves attention. Indeed, as described above, several treatment approaches targeting GPC3 have been recently developed and are being evaluated in HCC patients.

Manipulation of GPC3 signaling pathways provides new avenues for HCC treatment. Hu et al.59 reported that curcumin decreased GPC3 expression and inactivated Wnt/β-catenin signaling, leading to the suppression of HCC tumor growth. Curcumin also inhibited proliferation and induced apoptosis of HepG2 cells and suppressed HCC tumor growth in vivo. GPC3 knockdown by siRNA enhanced the suppression effects of curcumin on Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Interference with GPC3-mediated signaling pathways by small molecules is an attractive therapeutic scheme with potential application in patients with HCC. However, currently, no small molecules targeting GPC3 have been developed or evaluated in HCC patients. Small-molecule GPC3 drugs may have the potential to offer increased efficacy, stability, and safety for HCC treatment. Additional research to develop GPC3 targeting small molecular compounds is needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Miranda Claire Gilbert for editing this manuscript. This study was supported by grants funded by the USA National Institutes of Health R01CA222490 to Y.-J. Y. Wan and the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center seed grants to Y.-J. Y. Wan and T.-C. Shih.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Wide-ranging online data for epidemiologic research (WONDER). Underlying cause of death output based on the Detailed Mortality File. https://wonder.cdc.gov/. Accessed Aug 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villanueva A Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1450–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ronot M, Bouattour M, Wassermann J, et al. Alternative Response Criteria (Choi, European association for the study of the liver, and modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [RECIST]) versus RECIST 1.1 in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Oncologist. 2014;19:394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li B, Liu H, Shang HW, Li P, Li N, Ding HG. Diagnostic value of glypican-3 in alpha fetoprotein negative hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Afr Health Sci. 2013;13:703–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo M, Zhang H, Zheng J, Liu Y. Glypican-3: a new target for diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer. 2020;11:2008–2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filmus J, Selleck SB. Glypicans: proteoglycans with a surprise. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:497–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Cat B, David G. Developmental roles of the glypicans. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2001;12:117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Cat B, Muyldermans SY, Coomans C, et al. Processing by proprotein convertases is required for glypican-3 modulation of cell survival, Wnt signaling, and gastrulation movements. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:625–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Traister A, Shi W, Filmus J. Mammalian Notum induces the release of glypicans and other GPI-anchored proteins from the cell surface. Biochem J. 2008;410: 503–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreuger J, Perez L, Giraldez AJ, Cohen SM. Opposing activities of Dally-like glypican at high and low levels of Wingless morphogen activity. Dev Cell. 2004;7:503–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pilia G, Hughes-Benzie RM, MacKenzie A, et al. Mutations in GPC3, a glypican gene, cause the Simpson-Golabi-Behmel overgrowth syndrome. Nat Genet. 1996;12:241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu Y, Papageorgiou A, Polychronakos C. Developmental regulation of the soluble form of insulin-like growth factor-II/mannose 6-phosphate receptor in human serum and amniotic fluid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pellegrini M, Pilia G, Pantano S, et al. Gpc3 expression correlates with the phenotype of the Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome. Dev Dyn. 1998;213: 431–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin H, Huber R, Schlessinger D, Morin PJ. Frequent silencing of the GPC3 gene in ovarian cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1999;59:807–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiang YY, Ladeda V, Filmus J. Glypican-3 expression is silenced in human breast cancer. Oncogene. 2001;20:7408–7412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim H, Xu GL, Borczuk AC, et al. The heparan sulfate proteoglycan GPC3 is a potential lung tumor suppressor. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:694–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powell CA, Xu G, Filmus J, Busch S, Brody JS, Rothman PB. Oligonucleotide microarray analysis of lung adenocarcinoma in smokers and nonsmokers identifies GPC3 as a potential lung tumor suppressor. Chest. 2002;121:6s–7s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu HC, Cheng W, Lai PL. Cloning and expression of a developmentally regulated transcript MXR7 in hepatocellular carcinoma: biological significance and temporospatial distribution. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5179–5184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capurro MI, Xiang YY, Lobe C, Filmus J. Glypican-3 promotes the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma by stimulating canonical Wnt signaling. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6245–6254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li N, Wei L, Liu X, et al. A Frizzled-like cysteine-rich domain in glypican-3 mediates Wnt binding and regulates hepatocellular carcinoma tumor growth in mice. Hepatology. 2019;70:1231–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng M, Gao W, Wang R, et al. Therapeutically targeting glypican-3 via a conformation-specific single-domain antibody in hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E1083–E1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zittermann SI, Capurro MI, Shi W, Filmus J. Soluble glypican 3 inhibits the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2010;126: 1291–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu ZW, Friess H, Wang L, et al. Enhanced glypican-3 expression differentiates the majority of hepatocellular carcinomas from benign hepatic disorders. Gut. 2001;48:558–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Capurro M, Wanless IR, Sherman M, et al. Glypican-3: a novel serum and histochemical marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baumhoer D, Tornillo L, Stadlmann S, Roncalli M, Diamantis EK, Terracciano LM. Glypican 3 expression in human nonneoplastic, preneoplastic, and neoplastic tissues: a tissue microarray analysis of 4,387 tissue samples. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen M, Li G, Yan J, et al. Reevaluation of glypican-3 as a serological marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;423:105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qiao SS, Cui ZQ, Gong L, et al. Simultaneous measurements of serum AFP, GPC-3 and HCCR for diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepato-Gastroenterology. 2011;58:1718–1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu H, Li P, Zhai Y, et al. Diagnostic value of glypican-3 in serum and liver for primary hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4410–4415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bengochea A, de Souza MM, Lefrançois L, et al. Common dysregulation of Wnt/Frizzled receptor elements in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:143–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee HC, Kim M, Wands JR. Wnt/Frizzled signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Biosci. 2006;11:1901–1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev Cell. 2009;17:9–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lai JP, Oseini AM, Moser CD, et al. The oncogenic effect of sulfatase 2 in human hepatocellular carcinoma is mediated in part by glypican 3-dependent Wnt activation. Hepatology. 2010;52:1680–1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lai JP, Thompson JR, Sandhu DS, Roberts LR. Heparin-degrading sulfatases in hepatocellular carcinoma: roles in pathogenesis and therapy targets. Future Oncol. 2008;4:803–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao W, Kim H, Ho M. Human monoclonal antibody targeting the heparan sulfate chains of glypican-3 inhibits HGF-mediated migration and motility of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. PLoS One. 2015;10, e0137664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montalbano M, Rastellini C, McGuire JT, et al. Role of Glypican-3 in the growth, migration and invasion of primary hepatocytes isolated from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2018;41:169–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qi XH, Wu D, Cui HX, et al. Silencing of the glypican-3 gene affects the biological behavior of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10:3177–3184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu Y, Liu H, Weng H, et al. Glypican-3 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through ERK signaling pathway. Int J Oncol. 2015;46:1275–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakano K, Orita T, Nezu J, et al. Anti-glypican 3 antibodies cause ADCC against human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;378:279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakano K, Ishiguro T, Konishi H, et al. Generation of a humanized anti-glypican 3 antibody by CDR grafting and stability optimization. Anticancer Drugs. 2010;21:907–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ishiguro T, Sugimoto M, Kinoshita Y, et al. AntieGlypican 3 antibody as a potential antitumor agent for human liver cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68: 9832–9838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phung Y, Gao W, Man YG, Nagata S, Ho M. High-affinity monoclonal antibodies to cell surface tumor antigen glypican-3 generated through a combination of peptide immunization and flow cytometry screening. MAbs. 2012;4:592–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang YF, Ho M. Humanization of high-affinity antibodies targeting glypican-3 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao W, Tang Z, Zhang YF, et al. Immunotoxin targeting glypican-3 regresses liver cancer via dual inhibition of Wnt signalling and protein synthesis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fu Y, Urban DJ, Nani RR, et al. Glypican-3-specific antibody drug conjugates targeting hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2019;70:563–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang C, Gao W, Feng M, Pastan I, Ho M. Construction of an immunotoxin, HN3-mPE24, targeting glypican-3 for liver cancer therapy. Oncotarget. 2017;8: 32450–32460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ishiguro T, Sano Y, Komatsu SI, et al. An antieglypican 3/CD3 bispecific T celleredirecting antibody for treatment of solid tumors. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9, eaal4291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu AX, Gold PJ, El-Khoueiry AB, et al. First-in-man phase I study of GC33, a novel recombinant humanized antibody against glypican-3, in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:920–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yen CJ, Daniele B, Kudo M, et al. Randomized phase II trial of intravenous RO5137382/GC33 at 1600 mg every other week and placebo in previously treated patients with unresectable advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC; NCT01507168). J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:4102.25403208 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Puig O, Chen YC, Shochat E, et al. Biomarker analysis of a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter phase II trial of intravenous RO5137382/GC33 at 1600 mg Q2W in previously treated patients with unresectable advanced or metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (NCT01507168). J Clin Oncol. 2014;32, e15090. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aruna G Immunotoxins: a review of their use in cancer treatment. J Stem Cells Regen Med. 2006;1:31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.FitzGerald DJ, Wayne AS, Kreitman RJ, Pastan I. Treatment of hematologic malignancies with immunotoxins and antibody-drug conjugates. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6300–6309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weldon JE, Xiang L, Chertov O, et al. A protease-resistant immunotoxin against CD22 with greatly increased activity against CLL and diminished animal toxicity. Blood. 2009;113:3792–3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu W, Onda M, Lee B, et al. Recombinant immunotoxin engineered for low immunogenicity and antigenicity by identifying and silencing human B-cell epitopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:11782–11787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Capurro MI, Xiang YY, Lobe C, Filmus J. Glypican-3 promotes the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma by stimulating canonical Wnt signaling. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6245–6254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang JS, Chao CC, Su TL, et al. Diverse cellular transformation capability of overexpressed genes in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;315:950–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song HH, Shi W, Xiang YY, Filmus J. The loss of glypican-3 induces alterations in Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2116–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gao W, Kim H, Feng M, et al. Inactivation of Wnt signaling by a human antibody that recognizes the heparan sulfate chains of glypican-3 for liver cancer therapy. Hepatology. 2014;60:576–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schulze K, Imbeaud S, Letouzé E, et al. Exome sequencing of hepatocellular carcinomas identifies new mutational signatures and potential therapeutic targets. Nat Genet. 2015;47:505–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hu P, Ke C, Guo X, et al. Both glypican-3/Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and autophagy contributed to the inhibitory effect of curcumin on hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51:120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]