Abstract

The rise of hydraulic fracturing and unconventional oil and gas (UOG) exploration in the United States has increased public concerns for water contamination induced from hydraulic fracturing fluids and associated wastewater spills. Herein, we collected surface and groundwater samples across Garfield County, Colorado, a drilling-dense region, and measured endocrine bioactivities, geochemical tracers of UOG wastewater, UOG-related organic contaminants in surface water, and evaluated UOG drilling production (weighted well scores, nearby well count, reported spills) surrounding sites. Elevated antagonist activities for the estrogen, androgen, progesterone, and glucocorticoid receptors were detected in surface water and associated with nearby shale gas well counts and density. The elevated endocrine activities were observed in surface water associated with medium and high UOG production (weighted UOG well score-based groups). These bioactivities were generally not associated with reported spills nearby, and often did not exhibit geochemical profiles associated with UOG wastewater from this region. Our results suggest the potential for releases of low-saline hydraulic fracturing fluids or chemicals used in other aspects of UOG production, similar to the chemistry of the local water, and dissimilar from defined spills of post-injection wastewater. Notably, water collected from certain medium and high UOG production sites exhibited bioactivities well above the levels known to impact the health of aquatic organisms, suggesting that further research to assess potential endocrine activities of UOG operations is warranted.

Keywords: Endocrine disrupting chemicals, Water contamination, Hydraulic fracturing, Unconventional oil and gas operations, Hormonal activity, Natural gas production

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

Unconventional oil and natural gas (UOG) operations have increased oil and gas production in the United States over the last three decades by coupling horizontal drilling with hydraulic fracturing to unlock previously inaccessible hydrocarbon deposits. As a result, domestic oil and gas production has surged, with the United States becoming the top producer of both oil and natural gas worldwide until a global crash in prices slowed UOG production in 2015. Production surged again in the last several years, with record U.S. production in 2018 before another recent decline. Hydraulic fracturing, a common form of stimulation utilized to liberate oil and gas from impermeable geologic formations, involves the high pressure injection of water, chemicals, and sand to generate fractures in shale and other low permeability formations and release the trapped natural gas and/or oil (Waxman et al., 2011; Wiseman, 2008). More than 1000 different chemicals have been reported to be used for hydraulic fracturing across the U.S., though between fifteen and fifty are commonly used in any individual well (US EPA, 2015; Waxman et al., 2011). Wastewater from UOG operations is inclusive of two phases, with a gradual transition from one to the next. Following injection, “flowback water” is recovered as a variable percentage of the injected fluids, mixed with formation water that is released from the geological formations. Over time, the relative proportions of the returned injected water and organic chemicals utilized for fracturing decrease over time as the fraction of the formation water increases, generating “produced waters” that is then continually generated over the life of each producing well (Deutch et al., 2011; Engle et al., 2014) and often contains elevated salts, ammonium, dissolved organic matter, naturally occurring radioactive elements, and heavy metals (Akob et al., 2015; Rowan et al., 2015). In the U.S., UOG wells produce an estimated volume of between 3.18 and 3.97 billion m3 of wastewater (inclusive of flowback and produced water) per year (Clark and Veil, 2009; Harkness et al., 2015), which are routinely disposed of through injection into deep disposal wells, reused for hydraulic fracturing operations, spread on roads as a de-icing or dust suppressing agent (Tasker et al., 2018), and/or pumped into open evaporation pits for disposal (Deutch et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2011; Lester et al., 2015; Wiseman, 2008).

Spills, leaks, and unintentional releases of wastewater associated with UOG activities into the environment can impact the quality of surface and groundwater resources through transfer of organic contaminants to drinking water (Burgos et al., 2017; DiGiulio and Jackson, 2016; DiGiulio et al., 2011; Drollette et al., 2015; Rozell and Reaven, 2012; Skalak et al., 2014), heavy metals to nearby groundwater (Fontenot et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2019), stray gas contamination (methane, ethane, propane) into nearby drinking water wells (Darrah et al., 2014; Jackson et al., 2013; Osborn et al., 2011), accumulation of radionuclides in stream sediments near disposal and spill sites (Burgos et al., 2017; Warner et al., 2013), and potential formation of disinfection byproducts downstream from saline wastewater releases (Harkness et al., 2015; Hladik et al., 2014; Parker et al., 2014). Several studies have evaluated UOG operation spill rates (inclusive of pre-injection chemicals, flowback water, and produced waters) across four U.S. states, reporting spills at rates ranging from 2 to 20% of active well sites (Maloney et al., 2017; Patterson et al., 2017), mainly due to improper storage and transport of fluids. Others have previously demonstrated that some commonly used UOG additives can act as endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) both in vitro and in vivo (Blewett et al., 2017; He et al., 2017a; He et al., 2017b; Kassotis et al., 2016a; Kassotis et al., 2015). EDCs are exogenous chemicals or mixtures of chemicals that can interfere with some aspect of hormone action (Diamanti-Kandarakis et al., 2009; TEDX, 2018b; Zoeller et al., 2012) and can disrupt development and contribute to disease in both humans and animals (Vandenberg et al., 2012; Welshons et al., 2003). Our previous research has demonstrated increased endocrine activities in surface water and groundwater near UOG spill sites in Colorado (Kassotis et al., 2014), downstream from an UOG wastewater injection disposal site in West Virginia (Kassotis et al., 2016b), and downstream from an UOG wastewater spill in North Dakota (Cozzarelli et al., 2017).

There is growing evidence, from laboratory and epidemiological studies, suggesting potential adverse health effects for humans and animals exposed to UOG operations (Elliott et al., 2016; Werner et al., 2015). Epidemiological studies have documented associations between UOG operations and human health nearby, including but not limited to increased prevalence of congenital heart defects (McKenzie et al., 2014), lower birth weight and small-for-gestational-age births (Stacy et al., 2015), preterm births and high-risk pregnancies (Casey et al., 2016), higher rates of certain cancers (Finkel, 2016; McKenzie et al., 2017; Mokry, 2010; Rawlins, 2014; Texas Dept State Health Services, 2014), and other adverse outcomes (Jemielita et al., 2015a; Jemielita et al., 2015b; Rabinowitz et al., 2015), though further research is needed to evaluate these associations. Laboratory studies have reported causative impacts of actual or laboratory-created UOG chemicals, mixtures, or fluids on diverse organisms. Specifically, mice gestationally exposed to environmentally-relevant concentrations of a laboratory-created UOG chemical mixture (Kassotis et al., 2016a; Kassotis et al., 2015) resulted in male and female pups that exhibited a range of developmental and reproductive impacts (Nagel et al., 2020), including increased birth weights and metabolic impacts (Balise et al., 2019a; Balise et al., 2019b), reduced sperm counts in males (Kassotis et al., 2015), inappropriate follicle activation leading to an increased rate of follicle atresia in females (Kassotis et al., 2016a), altered immune function (Boule et al., 2018), and increased development of mammary glands and intraductal hyperplasias (Sapouckey et al., 2018). Work in diverse aquatic organisms has demonstrated that exposure to flowback and produced waters results in reduced survival, reproduction, and other adverse endpoints (He et al., 2017a; He et al., 2017b; Blewett et al., 2017; Cozzarelli et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019). Due to this increasing evidence of adverse health impacts, it is critical to fill key data gaps in understanding potential environmental health impacts of UOG operations (US EPA, 2015).

The goals of this study were to characterize the endocrine disrupting activities of water samples collected in a drilling-dense region in Garfield County, Colorado (Fig. 1), to investigate potential associations with UOG operations, and to evaluate geochemical indicators for the presence of UOG wastewater. Specifically, we assessed both surface and groundwater at sites with limited or no UOG influence, sites with a spectrum of drilling activity nearby but without reported spills, and sites that had a documented historical spill. Water samples were collected at each site and processed for estrogen receptor alpha, androgen receptor, progesterone receptor B, glucocorticoid receptor, and thyroid receptor beta (ERα, AR, PR B, GR, TRβ, respectively) activities (agonism and antagonism); diagnostic inorganic geochemical tracers to identify UOG wastewater influence; and targeted organic contaminant measurements. Endocrine activities and inorganic geochemistry were assessed in relation to various UOG production metrics (inverse-distance weighted (IDW) well score, nearby well count, and nearby spill count) to characterize potential impacts of UOG operations. The novel approach presented herein combines established geochemical tracers of UOG operations (Burgos et al., 2017; Cozzarelli et al., 2017; Harkness et al., 2017; Orem et al., 2017; Warner et al., 2012) with endocrine activity analyses to evaluate potential environmental health impacts.

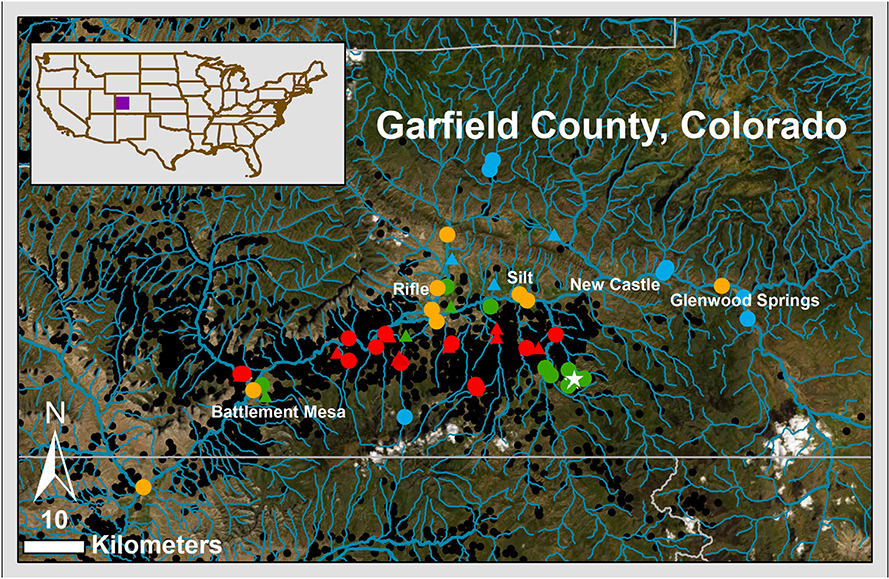

Fig. 1.

Map of Garfield County, Colorado sampling locations. Map of approximate sampling locations, both ground and surface water, from varying inverse-distance weighted well score groups, within and immediately outside Garfield County, Colorado. Triangles depict groundwater sampling sites, and circles denote surface water sites. Colors are utilized to depict degree of potential unconventional oil and gas influence, with reference sites appearing in blue, medium IDW score groups in green, high IDW groups in red. The surface water-specific group with upstream unconventional oil and gas development was depicted in orange, and unconventional oil and gas wells at time of sampling depicted with black circles. Well data obtained from the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission and figure produced using Arc GIS. As pictured, the Colorado River flows right to left in this figure (path follows the blue line from the orange dot on the far-right side (middle) in Gypsum, Colorado to the bottom left of the figure near Grand Junction, Colorado). IDW = inverse distanced weighted (well score). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Well data obtained from the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission and figure produced using Arc GIS. Online server maps hosted by Esri (layers available as “Add Data From ArcGIS Online” in ArcMap). Map image is the intellectual property of Esri and is used herein under license. Copyright © 2014 Esri and its licensors. All rights reserved. Service Layer Credits: National Geographic, Esri, Garmin, HERE, UNEP-WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, increment P Corp. Source: Esri, DigitalGlobe, GeoEye, Earthstar Geographics, CNES/Airbus DS, USDA, USGS, AeroGRID, IGN, and the GIS User Community.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

17β-Estradiol (E2; estrogen agonist, 98% pure), ICI 182,780 (estrogen antagonist, 98% pure), 4,5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT; androgen agonist, ≥97.5% pure), flutamide (androgen antagonist, 100% pure), 3,3′,5-triiodo-L-thyronine (T3; thyroid agonist, ≥95% pure), progesterone (P4; progesterone agonist, ≥99% pure), mifepristone (glucocorticoid/progesterone antagonists, ≥98% pure), dexamethasone (DEX; glucocorticoid agonist, 99.5% pure), and hydrocortisone (glucocorticoid agonist, 98% purity) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO). 1–850 (thyroid antagonist, ≥95% pure) was purchased from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). A stock solution of each chemical was prepared at 10 mM in HPLC-grade methanol and stored at −20 °C; T3 and 1–850 were prepared in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). Stock solutions were then diluted in respective solvents to required working solution concentrations.

2.2. Selection of sample sites and controls

Water samples (n = 67) were collected from ground and surface (both flowing and standing) water sites between September 2014 and February 2015 (Fig. 1, Table 1, Table S1) within Garfield County, Colorado. Sites included surface, standing, and groundwater sources collected from public land and private land. These sites were selected based on previous sampling (Kassotis et al., 2014), connections made through various community groups, and word-of-mouth recommendations, and thus could represent a selection bias. However, care was taken to include a selection of reference samples with little or no UOG activity nearby, a series of samples with other industrial influences, samples with a wide range of UOG activity nearby (from 0 to 157 wells within a one mile radius from sampling site; Table 1, Table S1), and sites with a documented UOG spill that had occurred nearby at some point in the past. Following sampling, Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC) data (available at: http://cogccmap.state.co.us/cogcc_gis_online/) were extracted to Arc GIS and used to determine the number of wells within a one-mile radius of each sample collection site at the time of sampling. Inverse distance weighted (IDW) well scores were calculated; historical natural gas well count was determined using the previously-published Google Earth™ data set, organized by SkyTruth in 2008 from COGCC data (available at: https://skytruth.org/2008/06/colorado-all-natural-gas-and-oil-wells/) (Kassotis et al., 2014) and thus representing the well counts present in 2008. Spill numbers and volumes within one and five miles were also determined for each collection site using the FrackTracker spill registry database (available at: https://www.fractracker.org/map/us/colorado/).

Table 1.

Characteristics of sampling sites.

| Drilling activity category | Sample size (n) | IDW (median, range) | Sampling well count (median, range) | Historical well count (median, range) | Spill number 1 mile (median, range) | Spill number 5 miles (median, range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory controls | 9 | |||||

| Process controls | 7 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Field blanks | 2 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Surface water (all) | 46 | |||||

| Reference (IDW: 0–5) | 7 | 0 (0–4.9) | 0 (0–4) | 0 (0–28) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) |

| UOG-source flowing | 11 | 0 (0–14) | 0 (0–9) | 2 (0–6) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–5) |

| Medium (IDW: 5–125) | 11 | 27.5 (9.9–122.7) | 9 (3–72) | 19 (0–72) | 1 (0–2) | 2 (1−12) |

| High (IDW: 125+) | 14 | 220.3 (125.5–434.3) | 96.5 (68–152) | 90.5 (35–157) | 0 (0–2) | 4 (1–12) |

| Wastewater | 3 | 54.9 (17.4–92.3) | 9 (9–9) | 19 (19–19) | 0 (0–0) | 2 (2–2) |

| Surface water (flowing only) | 34 | |||||

| Reference | 7 | 0 (0–4.9) | 0 (0–4) | 0 (0–28) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) |

| UOG-source flowing | 11 | 0 (0–14) | 0 (0–9) | 2 (0–6) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–5) |

| Medium (IDW: 5–125) | 6 | 35 (9.9–122.7) | 26 (3–72) | 20.5 (0–72) | 1 (0–2) | 2 (1–12) |

| High (IDW: 125+) | 10 | 192.5 (125.5–264.7) | 105 (76–152) | 76 (35–140) | 0 (0–1) | 3.5 (1–12) |

| Wastewater | 0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Groundwater | 21 | |||||

| Reference (IDW: 0–5) | 3 | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) |

| Medium (IDW: 5–125) | 6 | 108.8 (5.1–121.7) | 46.5 (4–72) | 23.5 (2–72) | 0.5 (0–2) | 4.5 (1–12) |

| High (IDW: 125+) | 12 | 171.1 (126.6–233.4) | 85 (68–141) | 59 (14–134) | 0.5 (0–3) | 4 (1–7) |

Descriptive statistics for unconventional oil and gas production metrics near sampling sites. Median and range are provided for the inverse distance weighted (IDW) well score, well count within one mile at the time of sampling, a historical value from 2010, and also number of known/reported spills within one or five miles. Data extracted from the Colorado Oil and Gas Commission website/data sets for calculation of IDW scores and other production metrics. Groups were based on all samples across the study, not performed within each water type; reference samples with no known input from anthropogenic sources separated from medium group as proxy measure of no known anthropogenic impacts. As such, not every group contains the same number of samples within each water type. UOG = unconventional oil and gas; these are flowing surface water samples that while they have low IDW well scores, flow from high UOG well density regions and thus cannot be considered medium IDW or reference sites.

IDW well scores were calculated similarly to those calculated in a previous study (McKenzie et al., 2014) and according to the following equation: IDW well score = .

In this case, di was equal to the distance of the ith well from the sampling site and n was equal to the number of wells located within a one-mile radius of the sampling site. Briefly, every well within one mile of each sampling site was scored based on distance to the sampling site. The inverses of these distances were summed to create IDW scores, with greater weight given to wells closer to sampling sites. Thus, an IDW well score of 20 could either reflect 20 wells that were each located one mile from the sampling site, or 2 wells located 0.1 miles from the sampling site.

Samples were sorted into groups for statistical analyses as follows: all collected water samples were ranked by IDW well scores. Reference sites were separated out as: IDW well scores of <5, no active oil/gas wells within one mile upstream, and not originating in or previously flowing through a high-density UOG region. Remaining samples were split evenly into two drilling-density groups, medium and high, based on IDW well scores. Medium IDW well score samples were defined by IDW well scores of 5–125, and high IDW well score samples were defined as those above 125. A subset (upstream UOG) was separated from medium/high groups and consisted of surface water samples with low IDW well scores (0–14) that had flowed through a high UOG production region within the surrounding five miles. This group contains all samples collected from the Colorado River and other flowing water samples that could have been impacted by other known point sources of pollution, including area wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). Comparisons were made to reference sites and all other sampling sites, and trend p values were evaluated using numerical groupings for reference (0), medium IDW (1), and high IDW (2) where possible to evaluate potential significant changes with increasing/decreasing IDW group. UOG-source flowing and wastewater samples were excluded from trend analyses due to the potential non-linear associations with the other groups, potential for other point sources of pollution for flowing samples, and due to the small sample size for wastewater. Wastewater samples were defined as flowback or produced water to the degree possible through geochemical analysis, though were broadly referred to as wastewater throughout.

2.3. Grab sample collection

A two-pronged sample collection scheme was applied at each sample collection site for 1) endocrine activity assays and analytical organic chemistry and 2) inorganic geochemistry. Samples for endocrine assays were collected as follows, and as described previously (Kassotis et al., 2016b; Kassotis et al., 2014), in one-liter amber glass bottles (Thermo Scientific catalog # 05–719-91) that were certified to meet the EPA standards for metals, pesticides, volatiles, and non-volatiles. Surface water samples were taken from moving stream/river water by submerging bottles, filling completely, and capping without headspace, after rinsing bottle and cap twice with sample site water prior to collection. Standing water samples were collected as above from ponds, lakes, and other non-moving pools of water. Ground water samples were filled at outdoor spigots prior to any treatment systems, as above, making every effort to avoid any potential source of plastic contamination where possible.

Field blanks were collected at two sites and contained 1 L of laboratory HPLC-grade control water (Fisher Scientific, cat # WFSK-4), opened and briefly exposed to the air during sample collection at that site, and then preserved and processed in the same manner as all other experimental samples (Table S1). All samples were stored on ice in the field, shipped in coolers overnight to our laboratories, stored at 4 °C on arrival, and were extracted within two weeks of collection. All processing, extractions, and assays were performed blinded to sample identification using non-identifiable coded IDs. Results were analyzed using these coded IDs and only de-identified to site IDs after analysis. Process controls were prepared using 1 L of Fisher HPLC water and followed the same protocols used for all experimental samples. These controls were included in each assay to assess any receptor activities contributed by the laboratory processing for each set of samples. Neither process controls nor field blanks exhibited any significant bioactivities.

Samples for inorganic geochemistry were collected as follows: water samples from wells were collected prior to any treatment systems and were filtered and preserved in high density polyethylene (HDPE), air tight bottles following USGS protocols (USGS, 2018). Samples were filtered through sterile Millipore (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) syringe filters (0.45-μm) using sterile 20 mL hand syringes for dissolved anions and strontium (Sr). Trace metal samples were preserved in acid-washed HDPE bottles pre-acidified to approximately 1% v/v Optima nitric acid (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), following filtering through a 0.45-micron filter, to reach an end pH < 2. All samples were preserved on ice in the field and shipped in a cooler overnight to the laboratory for analysis of Cl, Br, SO4, HCO3, Ca, Na, Ba, Si, Li, B, Mg, Sr, 87Sr/86Sr, and δ18O.

2.4. Extraction of water samples for bioassays

Water samples for endocrine assays were extracted via a solid-phase extraction (SPE) protocol described in detail previously (Kassotis et al., 2016b; Kassotis et al., 2014). Briefly, samples were pre-filtered using a glass-fiber filter to remove suspended solids, and then solid-phase extracted using Oasis HLB glass cartridges. Elutions were performed with 100% methanol, and a DMSO “keeper” was used during evaporation under nitrogen gas. Reconstitution was performed using 100% methanol to create 4000× stocks in 80:20 methanol:DMSO and were stored at −20 °C, protected from light, until tested. In order to be applied to cells, stock samples were diluted 100 and/or 1000-fold in tissue culture medium, creating final concentrations, in contact with cells, of 40×/4× the original water concentration.

2.5. Sample toxicity

Prior to assessing endocrine activities using nuclear receptor reporter gene assays, all samples were assessed for toxicity at the 40×/4× concentrations to ensure that no cytotoxic concentrations were included in receptor analyses. This testing was performed using the CellTiter 96 nonradioactive cell proliferation assay (Promega cat# G4000) as described previously (Kassotis et al., 2015). Briefly, Ishikawa cells (Sigma cat# 99040201) were seeded into 96-well plates at approximately 30,000 cells/well and allowed to settle. Cells were induced with test chemicals and water sample extracts, diluted in assay media using a 1% methanol vehicle, for 18–20 h, and then dye solution was added. Plates were incubated for a further hour and absorbance was then read at 570 nm. Toxicity was defined as a significant decrease (as per paired t-test) of ≥15% of the vehicle control levels, and samples exhibiting significant toxicity were excluded from analysis. As antagonist assays assess reduction in luminescence, toxicity cannot be uncoupled from antagonism. In addition, cytotoxic signal burst can result in non-specific activation of receptors and incorrectly identify receptor agonism. As such, any sample found to exhibit toxicity at the 40× concentration (CO-16, 19, 63, and 65) was tested for receptor bioactivities at 4× and 0.4×, and samples exhibiting toxicity at both 4× and 40× (CO-23) were tested only at 0.4× and 0.04×.

2.6. Mammalian hormone receptor activity assays

Ishikawa cells were maintained and transiently transfected with plasmids as described previously (Kassotis et al., 2015; Kassotis et al., 2014) for ERα, AR, PR B, GR, and TRβ reporter gene assay assessment. Transfected cells were induced with dilution series of the positive/negative controls (Fig. S1) or of the water sample extracts, diluted in medium using a 1% methanol vehicle. Each sample test concentration was performed in quadruplicate within each assay and each assay was repeated three times with a different cell passage. Further confirmatory cytotoxicity testing was included in reporter gene assays, using CMV-β-Gal activity as a marker of cell number, and as a surrogate marker for sample toxicity as described previously (Kassotis et al., 2014). These assays confirmed that no cytotoxic samples were included in the nuclear receptor assays.

Percent receptor activities were calculated as follows and as described previously (Kassotis et al., 2015; Kassotis et al., 2014): test chemical fold inductions at each concentration were calculated relative to plate-specific solvent control responses (1% methanol or 0.1% DMSO). The maximal positive control fold inductions (200 pM E2, 3 nM DHT, 100 pM P4, 100 nM T3, or 100 nM DEX for ERα, AR, PR B, TRβ, or GR receptor assays, respectively; Fig. S1) were then set at 100% for each respective assay. Agonist activities for test chemicals or samples were calculated as a percent activity relative to the maximal positive control fold induction (i.e. 100% activity at a given concentration would be equivalent to the maximal positive control induced response). Antagonist activities of the samples were calculated as a percent suppression of the co-treated positive control at the EC50 concentration (concentrations required to exhibit half of maximal activity; 20 pM E2, 300 pM DHT, 30 pM P4, 2 nM T3, and 5 nM DEX, respectively), with enhancement of EC50 responses of the positive controls by the water samples designated as additive agonism. The EC50 positive control response was thus considered 100% activity (0% antagonism) and inhibition of this response (in the absence of toxicity) was considered antagonism. Each sample was included as two to three biological replicates (unique assays in cells at varying passage number) and four technical replicates were included for each test concentration within each assay. Significant responses were defined as a significant deviation from control response (for agonism, the vehicle/solvent control; for antagonism, the EC50 control chemical response) based on Kruskal-Wallis tests.

To better assess potential health implications, receptor activities were converted to equivalent concentrations of positive control hormones. This allows for total receptor activation or inhibition by a mixture/environmental sample to be converted to a known concentration of a standard reference chemical that exhibits the same biological effect. These “equivalent concentrations” can be better utilized to perform risk assessments. As such, equivalence was calculated for each water extract that exhibited significant activity over the baseline solvent control (via Kruskal-Wallis) by using the percent activities relative to the positive control agonist and antagonist dose response curves (Fig. S1) and adjusting for the concentration of the extract in order to calculate equivalent concentrations that would elicit that control chemical response. Equivalent concentration values for each water sample and each bioactivity are provided in Table S2.

2.7. Inorganic geochemistry

Major anions were measured using a Dionex ion chromatograph following separation with an ASX-18X anion exchange column. Major cations (Ca, Mg, Na) were analyzed using direct current plasma optical emission spectrometry calibrated to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) 1643e standard. Trace elements were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) on a VG PlasmaQuad-3 also calibrated to the NIST 1643e standard. The detection limit of the ICP-MS for each element was determined by dividing three times the standard deviation of repeated blank measurements by the slope of the external standard. Sr was separated for isotope analysis using an Eichrom Sr-specific resin after concentration by evaporation. Following separation, samples were dried down with phosphoric acid and loaded onto rhenium filaments with TaCl. The 87Sr/86Sr ratios were collected in positive mode on a ThermoFisher Triton thermal ionization mass spectrometer (TIMS). Repeated measurements (n = 98) of the NIST Standard Reference Material (SRM) 987 standard had an external reproducibility of 87Sr/86Sr = 0.710265 ± 0.000006.

2.8. Organic chemical analysis

The concentrations of organic pollutants were determined in solid phase extracts (SPE; as prepared for bioassays) by either solid-phase microextraction (SPME) or water-dichloromethane liquid/liquid extraction followed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) according to previously-published methods (Kassotis et al., 2015; Kassotis et al., 2018). Briefly, volatile chemicals were extracted from SPE extracts using a headspace solid-phase microextraction (SPME) process: an aliquot of the 4000x SPE extracts were diluted with 20 mL of deionized water and 8 g of NaCl, vials were sealed, stirred, and the temperature increased to 30 °C, the 85-μm carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane fiber was inserted into the headspace and left for 15 min, and then was removed and immediately inserted into the hot injection port of the GC for 3 min to desorb. Analysis was performed with an Agilent 6890N gas chromatograph coupled with an Agilent 5973 N quadrupole mass spectrometer (GC–MS; Agilent Technologies). A separate aliquot of the SPE extracts was diluted in deionized water and then was subjected to a 1:1 water-dichloromethane liquid-liquid extraction for less volatile compounds (Kassotis et al., 2015; Kassotis et al., 2018). Analysis of these extracts was performed using a Varian 3400cx GC with a Hewlett Packard cross-linked methylsiloxane DB-5 capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm I.D.) and Varian Saturn 2000 ion-trap mass selective detector. Selection of diagnostic and quantitative ions was optimized, and the calibration equations were developed following the procedure described previously (Kassotis et al., 2015; Kassotis et al., 2018). Given the use of SPE extracts for volatile organic contaminant (VOC) analyses, many volatile contaminants may have poor recovery due to aerosolization; as such, these concentrations should be considered under-estimations of the concentrations likely present in actual water samples. As such, non-detects should infer that the chemicals are below the level of detection given our laboratory processing techniques and analytical capabilities. As such, organic contaminant analyses were considered exploratory/confirmatory in nature and were not utilized in statistical models.

2.9. Statistical analyses

Bioassay data are presented as means ± standard error (SE) from four technical replicates of three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using several methods: Spearman’s correlations were performed between all UOG (IDW well scores, well number within one mile, and spill number within one mile), inorganic geochemistry (trace minerals, metals, isotopes), and receptor agonism/antagonism (relative to positive controls) variables. All water samples were then ranked based on IDW well scores and separated into ranked groups. Robust regression analyses, as described previously (Hampel et al., 1986; Yohai, 1987), were performed to assess relationships between IDW well score groups and endocrine bioactivities. Given the smaller sample size for geochemistry results, we were not appropriately powered for regressions; as such, Kruskal-Wallis with post-test comparisons (Dunnett’s multiple comparison test) between reference samples and UOG sampling groups (by water type), were then performed to assess differences between varying levels of UOG production. All differences for each model and approach were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Given the inherent differences comparing subtypes of surface water, a sensitivity analysis was performed on all surface water analyses to assess any differences in statistical outcomes when excluding all standing water samples (to determine robustness of statistical outcomes). We found that exclusion of standing water samples did not appreciably change the outcomes, as described above, and so all surface water samples were retained. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 and SAS 9.4.

3. Results

Inverse distance weighted (IDW) well scores (normalized metric to account for the number of UOG wells within one mile, and distances of the sampling site from each UOG well) were calculated as described in Materials and methods, and groups and sampling sites are described in Tables 1 and S1. Water samples were separated into groups as follows: reference (IDW well scores <5 and no active wells or spills nearby), medium (IDW well scores of 5–125), high (IDW well scores of 125+), upstream UOG (surface water flowing from high UOG production regions), and UOG wastewater (collected from spills or well pad tanks). Differences were determined relative to reference for each endocrine bioactivity, and associations between UOG production metrics (IDW well scores, number of wells within one or five miles (both at time of sampling, 2014–2015, and historical well counts from 2008), and spill numbers within one and five miles of the sampling sites), endocrine bioactivities, and inorganic geochemistry.

3.1. Surface water receptor bioactivities and UOG operations

Surface water samples (n = 46) were separated into five groups (reference, medium IDW well score, high IDW well score, upstream UOG, and wastewater). Receptor activities are reported as: percent activation relative to a maximal positive control (agonism) and percent inhibition of half-maximal positive control (antagonism).

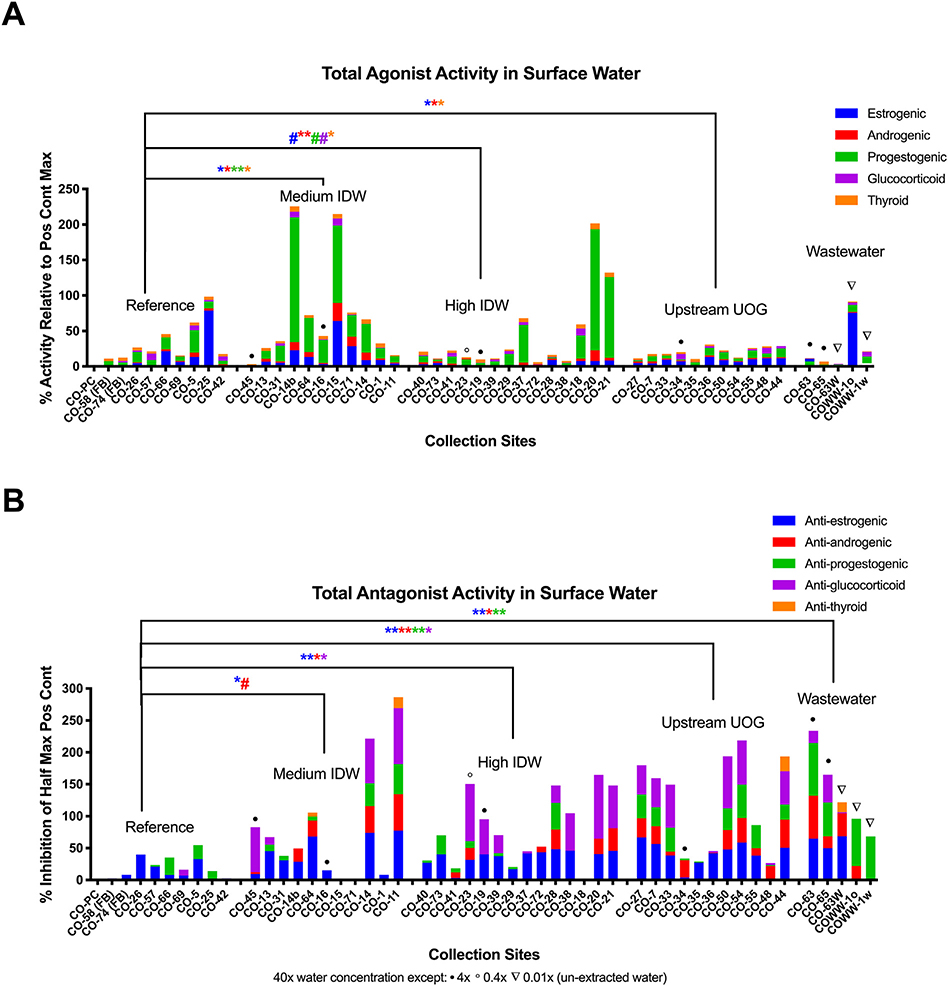

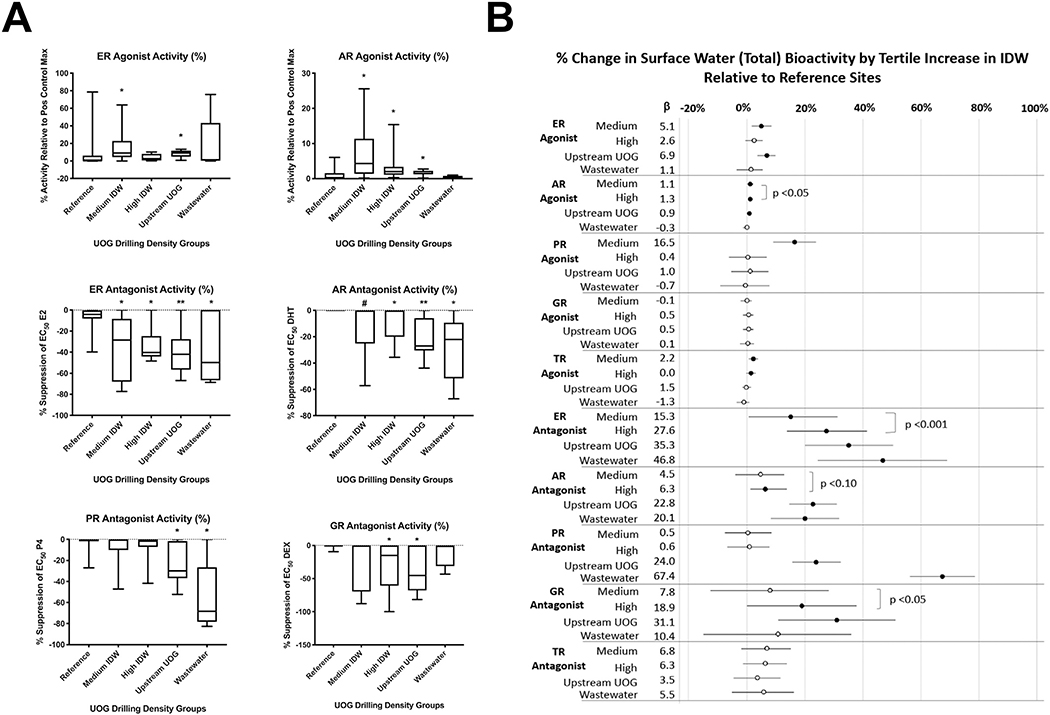

Agonist activities for the estrogen, androgen, progesterone, glucocorticoid, and thyroid receptors (ER, AR, PR, GR, and TR, respectively) were reported in each drilling-intensity group (Fig. 2A). ER, AR, PR, and TR agonist activities were significantly greater in the medium drilling-intensity group relative to the reference sites (robust regressions; p < 0.05). ER, AR, and TR agonist activities were greater in the high drilling-intensity group relative to reference sites (p < 0.10, 0.05, and 0.05, respectively). ER and AR agonist activities were greater in the upstream UOG group (p < 0.05) relative to the reference sites (Fig. 3A, B). While the magnitude of AR agonism was low (~1–1.5), it tended to increase with increasing IDW (p < 0.10; Fig. 3B). Several samples collected on or immediately next to UOG wells (CO-14b, CO-15, CO-20, and CO-21) had supramaximal PR agonist activity (greater activity than the maximal positive control response for the assay), and both the medium and high IDW groups had greater PR agonist activity relative to the reference (p < 0.05 and 0.10, respectively). Equivalent concentrations of positive control hormones for each sample are provided in Table S2. Agonist equivalences were below detection at most reference sites and blanks, and ranged from <LOD (limit of detection) to 4000 pg/L (≤3636 ng/L for CO-WW) for estradiol equivalence in surface water sites, <LOD to 2000 pg/L (<LOD) for dihydrotestosterone equivalence, <LOD to 24,000 pg/L (≤2094 ng/L) for progesterone equivalence, <LOD to 110 pg/L (≤235 ng/L) for dexamethasone equivalence, and <LOD to 570 pg/L (<LOD) for T3 equivalence. PR agonism was additionally correlated with reported spill number within one mile (Fig. S2; p < 0.05), supporting an association with UOG.

Fig. 2.

Endocrine bioactivities in surface water and nearby UOG operations. Combined total mean receptor activities for each water sample at 40× concentration (unless specified otherwise), determined using a transiently transfected human receptor reporter gene assay in Ishikawa cells. Combined total agonist activities (A) as percent activity relative to the mean intra-assay maximal positive control fold induction for each receptor: 200 pM 17β-estradiol (E2), 3 nM dihydrotestosterone (DHT), 100 pM progesterone (P4), 100 nM tri-iodothyronine (T3), or 100 nM dexamethasone (DEX) for ERα, AR, PR B, TRβ, and GR receptor assays, respectively. Combined total antagonist activities (B) as percent suppression of half maximal intra-plate positive control response for each receptor: 20 pM E2, 300 pM DHT, 30 pM P4, 2 nM T3, and 5 nM DEX, respectively. Results from replicate process controls are presented as mean values for each analysis period. Significance marks (** = p < 0.01, * = p < 0.05, # = p < 0.10) are derived from robust regressions performed in SAS 9.4. UOG = unconventional oil and gas. IDW = inverse distance weighted (well score).

Fig. 3.

Surface water bioactivities and relationship to UOG operations. Combined total mean receptor activities for each water sample at 40× concentration (unless specified otherwise), determined using a transiently transfected human receptor reporter gene assay in Ishikawa cells. A) Select box plots and robust regressions of endocrine bioactivities from surface water samples with unconventional oil and gas (UOG) density variables; full correlations between all variables are provided in Fig. S1. B) Stock plots detailing the results of robust regression models performed in SAS 9.4 using inverse distance weighted (IDW) well scores within one mile. All values were compared to reference samples, filled circles denote significant difference from reference and open denote insignificance. P values to right denote trend p values across groups defined by ranking sites by IDW scores.

Antagonist activities for each receptor were also prevalent across the surface water groups (Fig. 2B). ER and AR antagonist activities were greater in the medium IDW well score group relative to the reference sites (p < 0.05 and 0.10, respectively). ER, AR, and GR antagonist activities were greater in the high IDW group relative to reference sites (all p < 0.05). ER, AR, PR, and GR antagonist activities were greater in the upstream UOG group relative to reference sites (p < 0.01, 0.05, 0.01, and 0.05, respectively). ER, AR, and PR antagonist activities were greater in wastewater samples (p < 0.05) relative to the reference sites (Fig. 3A, B). ER, AR, and GR antagonism exhibited increasing bioactivity with increasing IDW (p < 0.001, 0.10, and 0.05, respectively; Fig. 3B). Antagonist equivalences were below detection at most reference sites and blanks, and ranged from <LOD to 260 ng/L (≤222 μg/L for CO-WW) for ICI 182,780 (fulvestrant) equivalence in groundwater sites, <LOD to 20 ng/L (<14 μg/L) for flutamide equivalence, <LOD to 183 ng/L (≤4726 μg/L) for mifepristone (anti-progesterone) equivalence, <LOD to 9666 ng/L (≤63 ng/L) for mifepristone (anti-glucocorticoid) equivalence, and <LOD to 520 ng/L (<834 μg/L) for 1–850 (anti-thyroid) equivalence (Table S2). PR antagonist activity was also negatively correlated with IDW well score and nearby well number at sampling (Fig. S2; p < 0.05).

3.2. Geochemical characterization of UOG wastewater

Produced waters from Western Colorado have been demonstrated previously to have salinity at or near the level of seawater with total dissolved solids (TDS) of up to 20,000 mg/L (Benko and Drewes, 2008; Blondes et al., 2018; Thyne, 2008), and are characterized by a sodium-chloride (Na-Cl) water type (Thomas and McMahon, 2012), high bromide-chloride ratios (Br/Cl > 1.5 × 10−3; molar unit), and relatively high boron-chloride (B/Cl) and strontium-calcium (Sr/Ca) ratios (means of 3.4 × 10−3 and 3.4 × 10−3, respectively). This water chemistry is typical for oil and gas brines from Western Colorado (Harkness et al., 2015; McMahon et al., 2013; Thyne, 2008; Vengosh et al., 2014; Warner et al., 2012) (Figs. 4, S3).

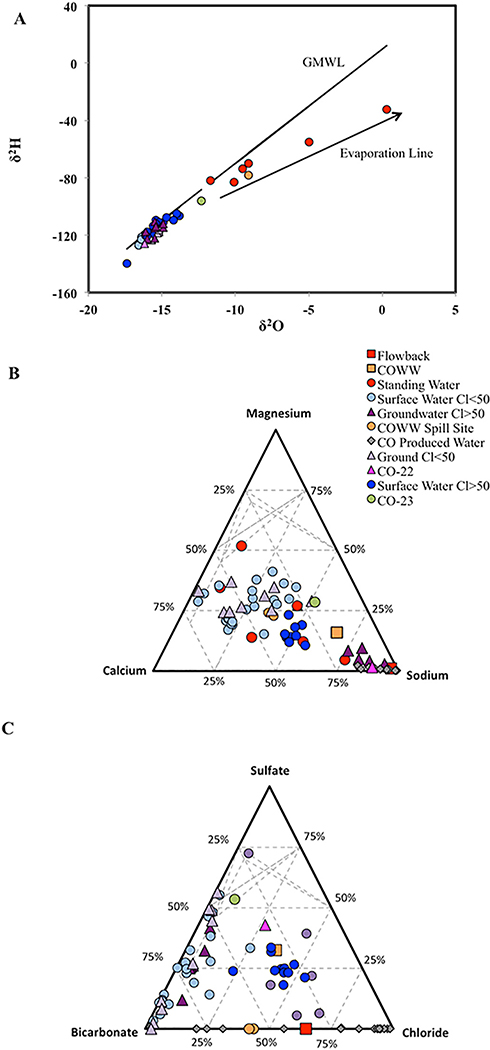

Fig. 4.

Water chemistry variations in surface and groundwater samples. Water isotopes and ternary plots showing water chemistry variations in the surface water and groundwater samples collected in the study area. The δ18O vs. δ2H plot (a) show samples that fall along the Global Meteoric Water Line (GMWL) (Kendall, Carol, and Tyler B. Coplen. “Distribution of oxygen-18 and deuterium in river waters across the United States.” Hydrological processes 15.7 (2001): 1363–1393), which are sourced primarily from rainwater, and samples that fall along an evaporation trend that is typical for formation waters sourced from evaporated seawater. Ternary plots show the relative (%) proportions of major cations (b) and anions (c). The differences in major ion between samples distinguish the different surface and groundwater chemistry types compared to wastewater collected in this study (COWW, COWW spill site) and previous reports for produced waters from Garfield County (CO produced water; refs. Benko and Drewes, 2008, Blondes et al., 2018). Surface and groundwater broken down into lower/higher salinity groups with threshold of 50 mg/L (Cl > 50 thus denote samples with chloride concentrations greater than 50 mg/L). Flowback = CO-63.

A single flowback sample from Garfield County was analyzed in this study (CO-63). The flowback water had TDS of ~4000 mg/L, which is expected for early stage flowback water upon mixing of low-saline injected water and formation water (Kondash et al., 2017; Kondash et al., 2014). The chemistry of this flowback water sample was consistent with data reported in previous studies (McMahon et al., 2013; Thomas and McMahon, 2012; Thyne, 2008). In particular, the water sample had Na-Cl water composition, high Cl and Na concentrations (>1800 mg/L) relative to local surface water and groundwater, high Br/Cl ratio (2.4 × 10−3), B/Cl ratio (6.8 × 10−3), and Sr/Ca ratio (3.0 × 10−2), high lithium (Li = 1.1 mg/L) and barium (Ba = 4.6 mg/L), and a high (radiogenic) strontium isotope (87Sr/86Sr) ratio of 0.71579 (Figs. 4, S3). An additional presumed wastewater sample was collected from an UOG industry pipeline spill (CO-WW1) and exhibited a remarkably different chemical profile with much lower salinity (chloride ~280 mg/L), a Na-bicarbonate-sulfate (Na-HCO3-SO4) water composition that is more typical of background water (Fig. 4), lower Li (200 μg/L), B (970 μg/L), and Ba (480 μg/L) concentrations (Fig. S3), relatively lower Br/Cl (7.0 × 10−4) ratio, and higher B/Cl (1.1 × 10−2) ratio and Sr (3.44 mg/L). This sample was previously reported to contain g/L concentrations for a number of organic contaminants associated with UOG operations (Kassotis et al., 2015).

3.3. Surface water geochemistry and UOG operations

Surface water across the study region had low salinity (Cl < 160 mg/L), and two distinctly different water types. Surface water samples collected from the Colorado River and several small streams had slightly higher salinity (Cl > 100 mg/L) than most other surface water samples and a Na-Ca-Cl-HCO3 water composition (Figs. 4, S3). These parameters are not consistent with the chemistry of the UOG-impacted water, but are consistent with historical Colorado River chemistry (Christensen et al., 2018). A second type of low-salinity surface water was found throughout the region and had distinctly lower Cl concentrations, a Ca-Mg-HCO3-SO4 water composition, lower Sr isotope (87Sr/86Sr) ratios, and higher oxygen isotope (δ18O) values, likely representing the natural surface water of the region.

High concentrations of dissolved salts and metals were found in several standing water or small ponds on or directly adjacent to well pads, with geochemistry consistent with UOG impacts. The chemistry of samples CO-14, 16, and 20 closely matched that of the UOG wastewater (sample CO-63), including elevated Cl concentrations, high Br/Cl and B/Cl ratios, low SO4, and high Sr isotope ratios (Figs. 4, S3). Sample CO-23 was the one sample located neither on nor directly adjacent to well pads exhibiting this geochemical signature, suggesting groundwater mixed with UOG wastewater (Fig. 4).

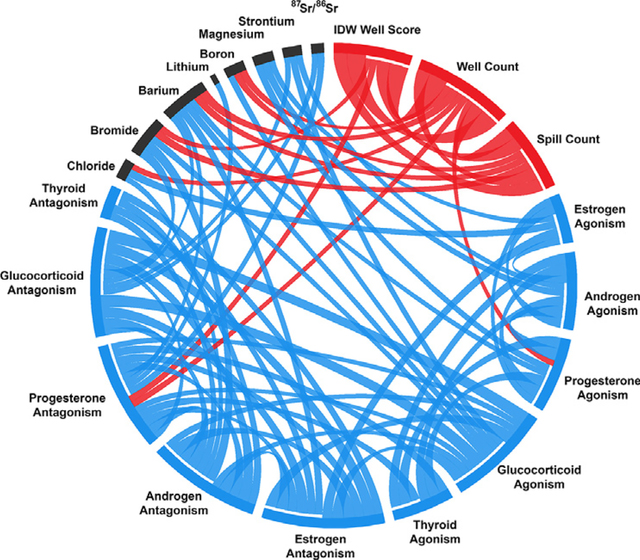

Several differences were observed in the geochemistry of the different groups (Fig. S3). UOG wastewater had high concentrations of Cl, Na, Sr, Ba, Br, Li, and B relative to the reference sites (Fig. S3) and also elevated 87Sr/86Sr ratios; the medium IDW group had high Br/Cl ratios, Si, and Ba concentrations (Fig. S3); and the high IDW group had high Br/Cl ratios (typically elevated in saline UOG produced waters but not saline waters from other sources). A sensitivity analysis was also performed to examine the potential role of the standing water sites in the surface water analysis (standing water sites excluded from models), but these sites were not found to significantly impact interpretation. Several inorganic variables were additionally correlated with UOG production variables (Fig. S2). Specifically, Br/Cl ratios were positively correlated, and Ca negatively correlated with IDW well score and well number at sampling; Ba and B were positively correlated with the historical well number; and Br, Ba, and B were positively correlated with spill number within five miles (all p < 0.05).

Correlations between endocrine activities and the surrogate geochemical tracers were also examined. ER agonism was positively correlated with Cl, TR agonism with Br/Cl ratios, and AR/PR agonism were negatively correlated with SO4 (SO4 have been reported previously to be inversely associated with UOG-impact in some regions (Akob et al., 2015; Akob et al., 2016; Barbot et al., 2013; Rosenblum et al., 2017a)). ER antagonism was positively correlated with Ba, and both AR/GR with Br (Fig. S2).

3.4. Surface water organic chemical analysis and association with UOG operations

A subset of surface water samples was selected (based on bioactivities) and analyzed for various semi-volatile organic contaminants known to be associated with UOG operations (Table 2). 2-Ethylhexanol was detected in all experimental samples (Table 2), including the field blanks and reference sites (though not the process control; suggesting a low-level laboratory contamination), though concentrations were markedly elevated above the blank contamination baseline at several sites nearest UOG operations (particularly CO-20 and CO-23). Naphthalene, 1-methylnaphthalene, and 2-methylnaphthalene were detected only at sites CO-14b and CO-23; 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene, cumene, and m/p-ethyltoluene were detected at sites CO-14 and CO-27; and ethylbenzene at CO-27 (Table 2); these chemicals were not reported in any other samples.

Table 2.

Organic contaminant concentrations for select Colorado surface water samples (μg/L).

| Sampling site | Group | Ethylbenzene | m/p-Xylenes | o-Xylene | Styrene | n-Propylbenzene | Cumene | m/p-Ethyltoluene | 1,3,5-Trimethylbenzene |

| CO-PC | Ref | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.001 | <LOD |

| CO-58 (FB) | Ref | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| CO-26 | Ref | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| CO-57 | Ref | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| CO-42 | Ref | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| CO-14b | Medium | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| CO-15 | Medium | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| CO-14 | Medium | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.004 | 0.003 | <LOD |

| CO-11 | Medium | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| CO-23 | High | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| CO-28 | High | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| CO-20 | High | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| CO-27 | Upstream UOG | 0.002 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.003 | 0.002 | <LOD |

| 1,2,4-Trimethylbenzene | 1,2,3-Trimethylbenzene | d-Limonene | 2-Ethylhexanol-1 | Diethylbenzenes | Naphthalene | 1-Methylnaphthalene | 2-Methylnaphthalene | ||

| <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | ||

| <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.003 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | ||

| <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.012 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | ||

| <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.008 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | ||

| <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.004 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | ||

| <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.002 | <LOD | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.009 | ||

| <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.016 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | ||

| 0.007 | <LOD | <LOD | 0.005 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | ||

| <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.005 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | ||

| <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.586 | <LOD | 13.468 | 21.284 | 11.081 | ||

| <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.004 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | ||

| <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.023 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | ||

| 0.002 | <LOD | <LOD | 0.006 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | ||

Estimated concentrations(μg/L) for various organic contaminants known to be associated with unconventional oil and gas operations, in select Colorado surface and groundwater samples. Concentrations are corrected for laboratory concentration due to solid-phase extraction and reflect the calculated concentration that would be present in μg/L of pure water. Due to the techniques employed in the solid-phase extraction process for endocrine bioassays (sample dry-down under nitrogen gas), many of these semi-volatile organic contaminants may have been aerosolized and thus, these concentrations should be considered under-estimations of the concentrations likely present in actual samples. As such, non-detects should also not infer that the chemicals are not present, only that they are below the level of detection given our laboratory processing techniques and analytical capabilities.

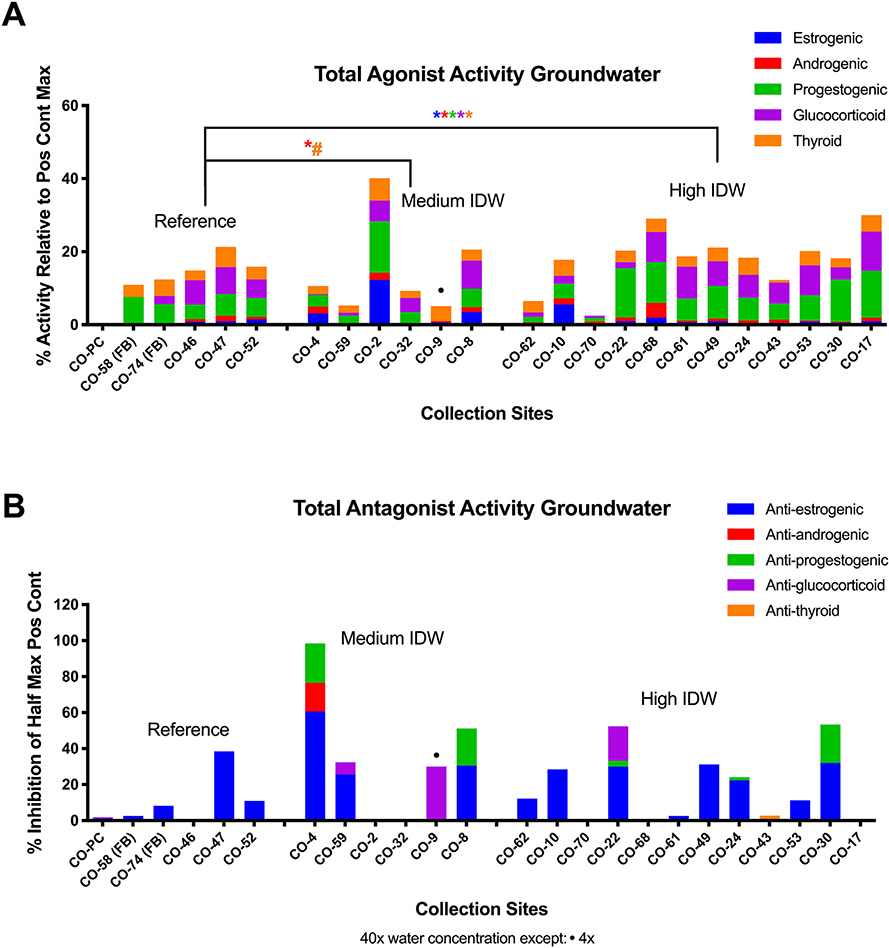

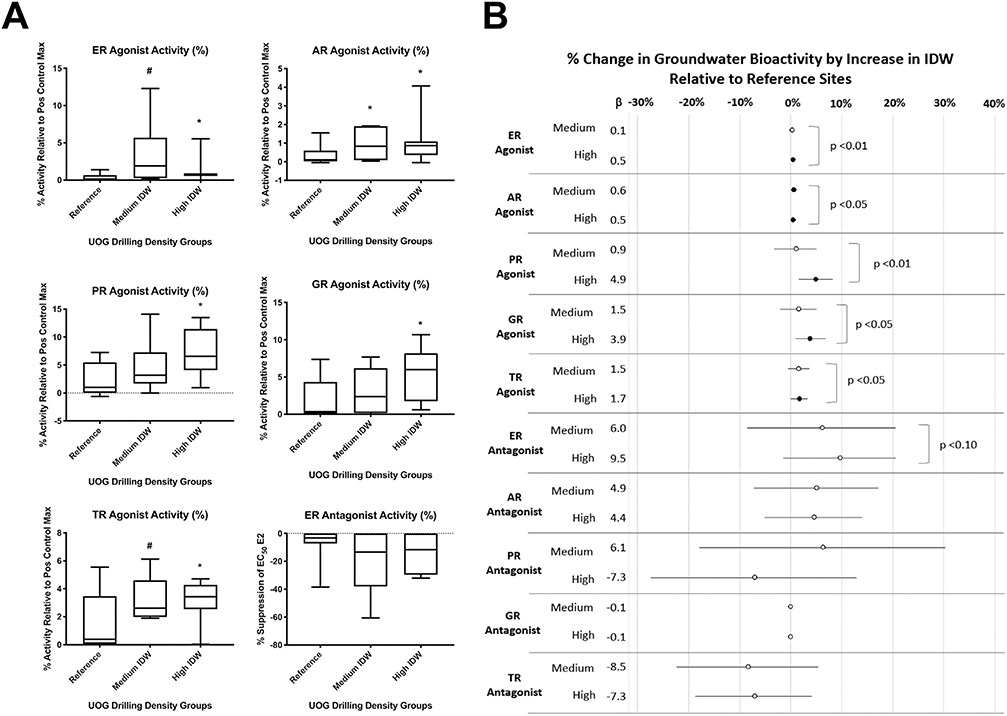

3.5. Groundwater receptor bioactivities and UOG operations

Groundwater samples (n = 21) were separated into three groups (reference, medium, and high IDW well scores). Agonist activities for the ER, AR, PR, GR, and TR were found in each of the designated drilling-intensity groups (Fig. 5A). ER, AR, and TR agonist activity were increased in the medium IDW group relative to reference (p < 0.10, 0.05, and 0.10, respectively). ER, AR, PR, GR, and TR agonist activities were all increased in the high IDW group relative to reference (p < 0.05; Fig. 6A). ER, AR, PR, GR, and TR agonist activities also increased with IDW (p < 0.05). Equivalent concentrations for each sample are provided in Table S2. Agonist equivalences were below detection at most reference sites and blanks, and ranged from <LOD to 140 pg/L for estradiol equivalence in groundwater sites, <LOD to 220 pg/L for dihydrotestosterone equivalence, <LOD to 90 pg/L for progesterone equivalence, <LOD to 110 pg/L for dexamethasone equivalence, and <LOD to 70 pg/L for T3 equivalence. Several agonist activities were significantly correlated with the UOG production variables (Fig. S4). Specifically, PR agonist activity was positively correlated with IDW well scores and spill number within one mile (p < 0.05) and TR agonist activity was positively correlated with spill number within five miles (p < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Endocrine bioactivities in groundwater are associated with nearby UOG operations. Combined total mean receptor activities for each water sample at 40× concentration (unless specified otherwise), determined using a transiently transfected human receptor reporter gene assay in Ishikawa cells. Combined total agonist activities (A) as percent activity relative to the mean intra-assay maximal positive control fold induction for each receptor: 200 pM 17β-estradiol (E2), 3 nM dihydrotestosterone (DHT), 100 pM progesterone (P4), 100 nM tri-iodothyronine (T3), or 100 nM dexamethasone (DEX) for ERα, AR, PR B, TRβ, and GR receptor assays, respectively. Combined total antagonist activities (B) as percent suppression of half maximal intra-plate positive control response for each receptor: 20 pM E2, 300 pM DHT, 30 pM P4, 2 nM T3, and 5 nM DEX, respectively. Results from replicate process controls are presented as mean values for each analysis period. Significance marks (* = p < 0.05, # = p < 0.10) are derived from robust regressions performed in SAS 9.4. UOG = unconventional oil and gas. IDW = inverse distance weighted (well score).

Fig. 6.

Endocrine bioactivities in groundwater are associated with nearby UOG operations. Combined total mean receptor activities for each water sample at 40× concentration (unless specified otherwise), determined using a transiently transfected human receptor reporter gene assay in Ishikawa cells. A) Select box plots and robust regressions of endocrine bioactivities from surface water samples with unconventional oil and gas (UOG) density variables; full correlations between all variables are provided in Fig. S3. B) Stock plots detailing the results of robust regression models performed in SAS 9.4 using inverse distance weighted (IDW) well scores within one mile. All values were compared to reference samples, filled circles denote significant difference from reference and open denote insignificance. P values to right denote trend p values across groups defined by ranking sites by IDW scores.

Antagonist activities for the ER, AR, PR, GR, and TR were less prevalent across the groundwater groups (Fig. 5B), and no significant differences were observed relative to reference sites (Fig. 6B). Antagonist activities were not correlated with any UOG metrics in groundwater (Fig. S4). Antagonist equivalences were below detection at most reference sites and blanks, and ranged from <LOD to 12.5 ng/L for ICI 182,780 (fulvestrant) equivalence in groundwater sites, <LOD to 1.4 ng/L for flutamide equivalence, <LOD to 14.3 ng/L for mifepristone (anti-progesterone) equivalence, <LOD to 35.8 ng/L for mifepristone (anti-glucocorticoid) equivalence, and <LOD for all groundwater for 1–850 (anti-thyroid) equivalence (Table S2).

3.6. Groundwater inorganic geochemistry and UOG operations

Groundwater TDS was <1000 mg/L in all samples, with Cl <100 mg/L (except CO-22). A Na-HCO3-SO4 water type was observed in the more saline samples (Cl >50) and a Ca-Mg-HCO3-SO4 type was found in low-salinity water samples (Fig. 4), consistent with historical groundwater data and distinguished from local oil and gas produced water (Thomas and McMahon, 2012). The stable isotopes of oxygen and hydrogen in the groundwater had values consistent with average surface water derived from rainfall (called the global meteoric water line; Kendall and Coplen, 2001), which suggests these samples originated from a meteoric source that was replenished to become local groundwater. Only one groundwater sample (CO-22) had a Na-Cl-HCO3 -SO4 water type and exhibited higher Cl (190 mg/L), Br/Cl and B/Cl ratios, and low SO4/Cl and Na/Cl ratios, suggestive of produced water impact (Thyne, 2008). The chemistry of this sample was very similar to CO-23, an apparent groundwater-fed pond located on the same property. Differences in inorganic geochemistry between IDW groups were minimal (Fig. S5), though Ba was higher in the medium and high IDW groups relative to the reference sites (p < 0.05 and 0.10, respectively). Several of the geochemical variables were significantly correlated with UOG operations (Fig. S4). Specifically, Ba and Si were positively correlated with IDW well scores; Ba was also positively correlated with current well number; and Cl, Br, and HCO3 were positively correlated with historical well number. Several endocrine activities were positively correlated with known geochemical tracers, supporting an association between the two (Fig. S4).

4. Discussion

We report that UOG operations in Garfield County, CO, are associated with elevated levels of antagonist nuclear hormone activities in local surface water. Previous studies have reported antagonism for multiple nuclear receptors following water contamination with UOG chemicals (Cozzarelli et al., 2017; Kassotis et al., 2016b; Kassotis et al., 2015; Kassotis et al., 2014). In the current study we report that this pattern was observed at sites in both the medium and high IDW well score groups (in many cases significantly increasing with IDW well scores). Endocrine bioactivities were correlated with IDW well scores and nearby well number but not with reported spills nearby, suggesting that identified spills were not the primary determining factor for UOG-associated bioactivities in nearby water. Importantly, this does not rule out a potential influence for non-reported spills or pollution from other chemical uses on well pads (chemicals are used throughout the development process, not just at the hydraulic fracturing stage) occurring at these sites. While not observed at most sites, we did match inorganic geochemical markers known to be associated with UOG wastewater (Cozzarelli et al., 2017; Harkness et al., 2017; Harkness et al., 2015; Warner et al., 2013; Warner et al., 2014; Warner et al., 2012) to the geochemistry in natural water from several sites nearest UOG wells. We also assessed a subset of water extracts from several sites that had exhibited elevated nuclear receptor bioactivities for the presence of selected semi-volatile organic compounds known to be associated with UOG operations (Akob et al., 2016; Cozzarelli et al., 2017; Luek and Gonsior, 2017; Orem et al., 2014; Orem et al., 2017), and detected elevated concentrations of chemicals associated with UOG production (including 2-ethylhexanol, naphthalene, trimethylbenzene, ethyltoluene, and cumene, and others). This presence of multiple receptor antagonism near UOG wells and concurrent presence of UOG-specific chemicals suggests that the endocrine bioactivities could be associated with UOG operations. This association could be inclusive of well pad development, increased truck traffic, potential spills of low-saline injection fluids, work-over chemicals, or other chemicals used throughout the development and production activities at well sites, which would likely be indistinguishable from the chemistry of the local surface water and groundwater.

We observed PR agonist activity at supramaximal activity from certain samples collected near UOG well pads (CO-14b, 15, 20, and 21) and at relatively high levels at a number of other sites near UOG operations (CO-5, CO-16, CO-64, CO-71, CO-14, CO-37, and CO-18). This suggests widespread presence of environmental PR agonists, for which there is minimal information available. There are reports that several PR agonists used as contraceptives, such as levonorgestrel, may be present in municipal wastewater (Fick et al., 2010), though the location of these supramaximal PR activity samples next to or on UOG well pads and upstream of any area WWTP suggest that this is not a plausible source. Instead, we have previously reported PR agonist activity for one of 24 commonly-used UOG chemicals (methylisothiazolin) (Kassotis et al., 2015), providing a potential link, but further research should employ effect-directed analysis to identify the active agents (PR agonists) within the samples.

A number of samples also exhibited a high degree of PR, GR, and TR antagonism, which are also uncommon environmental bioactivities. Environmental PR and GR antagonists, other than mifepristone (Runnalls, 2010), have not previously been reported. Given no known municipal wastewater inputs to these sources, and our previous identification of PR and GR antagonists for select commonly used UOG production chemicals (Kassotis et al., 2016b; Kassotis et al., 2015), this supports potential UOG contamination at several of our sampling sites. Increased bioactivities were noted at some sites in the medium IDW group at greater levels or with greater frequency than those in the high IDW group. This might seem counterintuitive, as greater IDW well scores would be assumed to contribute a greater likelihood of contamination. However, rates of contamination or inadvertent release of fluids are likely to vary by producer (as chemical use varies), geography, and the volume of fluid release at any individual site, resulting in disproportionate impacts due to our relatively modest sample size. Identifying better methods to delineate impacts and stratify samples may alleviate these differences in future studies.

In order to assess potential health outcomes anticipated from exposure to these waters, we converted bioactivities to concentrations of positive control hormones. This technique allows for comparison of total receptor activation by a mixture/environmental sample to be converted to a known concentration of a standard reference chemical that exhibits the same biological effect. By doing so, we can then utilize these “equivalent concentrations” to perform risk assessments (via comparison to human epidemiological and laboratory animal threshold values (Akingbemi and Hardy, 2001; Christiansen et al., 2008; Kelce and Wilson, 1997; Kidd et al., 2007; Mendiola et al., 2011; Sumpter and Jobling, 1995; Tyler et al., 1998)) to determine the level of endocrine activity exhibited by a given environmental sample and evaluate potential adverse health outcome risk. The high degree of conservation in nuclear receptor pathways (i.e. hormones and receptor dynamics operate very similarly across a wide range of species) (Diamanti-Kandarakis et al., 2009) supports this type of risk screening approach. These in vitro bioassays (particularly mammalian reporter gene assays, due to high sensitivity and ease of translation (Naylor, 1999; Soto et al., 2006)) are often applied for this purpose as they can more easily screen potential threats to human and environmental health than much more costly and time-consuming animal studies, since the ability of a chemical to interfere with any aspect of hormone action is a clear indicator of potential resultant health outcomes (Zoeller et al., 2012).

Certain samples exhibited significant bioactivities even when tested at the 4×and/or 0.4× concentrations (i.e. CO-9, 14b, 15, 16, 19, 20, 21, 23, 35, 45). For ER disruption, CO-23 exhibited 1.5 ng/L 17β-estradiol equivalence and 96 ng/L ICI equivalence (ER agonist and antagonist equivalent concentrations, respectively), approximately 10,000 and 3-times greater than the concentrations reported to result in adverse health outcomes in aquatic animals, respectively. Estradiol and ICI can disrupt sea urchin development at 0.1 pg/L (Roepke et al., 2005) and 30 ng/L ICI, respectively (Roepke et al., 2005). For GR disruption, CO-9, 19, 23, and 45 exhibited 29, 67, 7518, and 161 ng/L mifepristone equivalence, approximately 6, 11, 1250, and 26 times greater than the reported bioactive concentration. Five ng/L mifepristone equivalence (antagonism) has been demonstrated to impact egg production, disrupt folliculogenesis (an effect we previously observed in mice developmentally exposed to an UOG mixture (Kassotis et al., 2016a)), and alter gene expression in zebrafish (Bluthgen et al., 2013a; Bluthgen et al., 2013b). Notably, equivalent concentrations reported in the wastewater samples far exceeded the levels observed in surface and groundwater from the area. However, it should be noted that equivalent or greater concentrations for certain receptors (e.g. for ER agonism) have been reported previously from municipal wastewater inputs and some other industrial sources (Lei et al., 2020; Servos et al., 2005). Importantly, these levels of activity are associated with adverse impacts on wildlife in these areas, and thus these potential additional contributory sources to the environment (UOG operations) are of concern to area environmental health.

For PR disruption, CO-20 exhibited 15.7 ng/L progesterone equivalence and CO-23 exhibited 178 ng/L mifepristone equivalence (PR agonist and antagonist equivalent concentrations, respectively), approximately 4.5 and 36 times greater than the concentrations reported to result in adverse health outcomes in aquatic animals, respectively. Progesterone can alter gene expression and oocyte maturation in zebrafish at 3.5 ng/L (Zucchi et al., 2013) and mifepristone can effect zebrafish at 5 ng/L (Bluthgen et al., 2013a; Bluthgen et al., 2013b). Importantly, PR agonist activities for CO-14b, CO-15, CO-20, and CO-21 all resulted in supramaximal activity at tested concentrations, hindering the estimation of equivalent concentrations. In several cases, even with considerable dilution, levels of endocrine disrupting contaminants would still be capable of disrupting the development of fish, amphibians, and other aquatic organisms living in these water sources. Notably, while equivalent concentrations for other receptors generally fell below levels known to disrupt aquatic organism health in isolation, adverse health effects may result from disruption of several receptor pathways simultaneously. It was recently reported, for example, that ER, AR, and PR agonist pathways could all result in inhibition of egg production in fathead minnows through separate mechanisms (Runnalls et al., 2015), suggesting that assessing these endpoints in isolation may underestimate potential health impacts.

The presence, concentrations, and relative ratios of specific inorganic constituents in surface or groundwater (varying by region) can often provide a useful geochemical fingerprint, which can identify the specific source of potential contamination (including UOG operations). This has been demonstrated by a number of studies through the identification of specific geochemical and isotopic tracers that have distinct geochemical signatures (relative ratios) in the formation water (Cozzarelli et al., 2017; Harkness et al., 2017; Harkness et al., 2015; Warner et al., 2013; Warner et al., 2014; Warner et al., 2012). However, where freshwater is used for hydraulic fracturing (industry reports ≤100% of recovered produced waters are reused in other hydraulic fracturing events in Garfield County; US EPA, 2015, though freshwater and chemicals are still routinely mixed with this wastewater for new hydraulic fracturing events), the overall chemistry of the injection fluids would be entirely different from the chemistry of flowback and produced waters. Therefore, spills of the injection fluids or chemical mixtures prior to hydraulic fracturing would not be identifiable using inorganic geochemical tracers, which could potentially have contributed to our findings herein (presence of organic contaminants and increased endocrine bioactivities, but no diagnostic inorganics at most sites). In most regions, the water use for hydraulic fracturing is drawn from local sources and will largely mimic the inorganic geochemistry of regional surface water and/or groundwater. This may increase the utility of specific organic tracers, as certain groups have demonstrated (Rosenblum et al., 2017a; Rosenblum et al., 2017b; Sitterley et al., 2018), though the reported heterogeneity in chemical use may complicate the generalizability of these efforts.

An overall significant increase in some tracers such as Br/Cl ratios, Ba, and B/Cl ratios with IDW and other UOG parameters support the hypothesis that there are chronic releases of small volumes of UOG wastewater to surface water. In cases where the releases are directly associated with storage or disposal sources, or released to very small surface water bodies, the geochemical signatures are easily discernible. In this study, CO-20 (collected from standing water surrounding the wastewater tanks on a well pad) exhibited a distinct pattern that matched that of the region flowback water. CO-14 and CO-16 (collected from small ponds nearby a well pad) also exhibited these markers. The lack of geochemical identifiers of produced water in some other water samples characterized by high endocrine bioactivities could be the result of: releases of fresh injection waters or chemical mixtures that do not contain the tracers, lower salinity produced waters that are diluted so that the tracers are no longer detectable, or from other sources not yet identified. Either way, the lack of geochemical tracers in these samples does not preclude the source of the endocrine disrupting chemicals to be UOG-associated fluids.

The water chemistry for both surface and groundwater in the region is also quite variable, representing different water types related to a variety of likely natural and anthropogenic mechanisms. The saline surface water samples were primarily collected from the Colorado River and tributaries where the salinity is primarily driven by the addition of salts from upstream of the study area as well as significant evaporation of the surface waters in the semi-arid environment. Only one saline groundwater sample was collected with markedly different chemistry. A private drinking water well, CO-22, exhibited classical markers of UOG produced water contamination, and was at the site of a historical spill. CO-23, the surface water sample collected at the same location, exhibited a similar inorganic geochemistry profile that was more saline and distinct from other surface water in the area (with the exception of waters sampled directly adjacent to well pads). The geochemical similarities between CO-22 and CO-23 suggest a link between the surface and groundwater contamination at this location. The samples also shared a bioactivity profile, both exhibiting significant PR agonist, and ER/GR antagonist activities. However, the mixing of older, deeper fluids from producing formations into the shallow groundwater due to natural migration has been reported in this part of Garfield County and cannot be excluded as a potential source of the chemistry profile in these samples (McMahon et al., 2013).

As a third tier of assessment, we also measured the concentration of several chemicals that are reported by industry to be commonly used throughout UOG extraction (US EPA, 2015; TEDX, 2018a; Waxman et al., 2011). A range of volatile organic compounds were detected in our selected bioactive samples. Importantly, we detected elevated 2-ethylhexanol (above background) at CO-20, where we also had very high endocrine bioactivities and geochemical markers of UOG brine contamination. We also detected naphthalene and associated chemicals in CO-14, another produced water-influenced sample. Other UOG-related contaminants were identified in CO-14b, 15, 23, and 27, all above background levels. Concentrations of these putative UOG chemicals were also identified at high levels in the CO wastewater samples reported herein. While these chemicals could originate from other sources, the concurrent endocrine bioactivities and identification of specific produced water contamination via geochemical tracers at several of these sites provides strong support for these chemicals being contributed by nearby UOG operations. Recent research has reported that a number of organic contaminants were removed between 4 and 15 km of UOG releases (McLaughlin et al., 2020), suggesting more proximate impacts for organic contaminants.

Contamination of surface and groundwater with EDCs is now widespread (Barnes et al., 2008; Conley et al., 2017; Kolpin et al., 2002; Loos et al., 2009; Loos et al., 2010), and receptor bioactivities may be elevated through contamination of chemicals from a variety of sources (Alvarez et al., 2013; Conley et al., 2017; Van der Linden et al., 2008). However, every effort was made to identify other potential known sources of contamination. For example, CO-25 (medium IDW well score sample) exhibited approximately 80% ER agonist activity; this sample was collected downstream from a commercial fish hatchery in the region, a known contributor of natural hormones to surface water (Kolodziej et al., 2004). In an effort to address potential impacts of area WWTPs, samples potentially impacted by these were separated into the UOG-source flowing group to alleviate concerns over municipal wastewater impacting interpretation of endocrine bioactivities at sites in medium or high IDW groups. All water samples were subjected to solid phase extraction for endocrine bioassays (SPE, dry-down, and reconstitution), other than the wastewater samples. Given the volatility of many of the chemicals assessed, it is likely that certain contaminants were volatilized and lost during the sample dry-down process, as described previously (Kassotis et al., 2018). As such, non-detects may not represent an absence of a particular chemical from the water at a particular site, and calculated concentrations of detected contaminants should be assumed to be underestimations of the actual concentrations in water from these sites. While our processing of water samples limited accurate measurements of certain chemicals in unadulterated water from these sites, it did allow direct comparisons between chemicals present in the extracts and the bioactivities that those chemicals promoted.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we report elevated levels of antagonist endocrine bioactivities for five nuclear receptors near UOG operations, often independent of reported nearby spills. Importantly, many of these receptor bioactivities (PR/GR antagonism, PR agonism) have no other known potential contributory point source in the region (not downstream of any known area WWTPs). Greater endocrine activities were observed at sites in both the medium and high IDW groups, often from standing pools on or near well pads, suggesting potential impacts for groundwater at these sites and surface water sources via run-off. While some of these samples exhibit a distinct geochemical pattern mimicking produced water from the region, the absence of geochemical evidence for UOG wastewater contamination in other sites suggests potential spills of UOG chemicals associated with the freshwater injection fluids, work-over chemicals, or other chemicals used throughout the development and production activities at well sites, and without the distinguished geochemical fingerprint of UOG wastewater. This work suggests that coupling endocrine bioassays with geochemical analysis in characterizing mechanisms and evaluating possible water quality impacts from UOG operations may provide improved utility to detect contamination throughout the life of a well. The water assessed from some sites exhibited bioactivities well above the levels known to impact the health of aquatic organisms, suggesting further research is needed to assess the health of wildlife populations and human health surrounding UOG operations.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Tested endocrine bioactivities in water near unconventional oil/gas (UOG) operations

Antagonist activities increased near and correlated with density of UOG operations.

Geochemistry supports UOG produced water contamination at some sites.

Organic chemistry analysis suggests UOG contamination at other sites.

UOG-impacted samples disrupted nuclear receptors at environmentally relevant concentrations.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the large number of Garfield County residents who welcomed us onto their properties and allowed us to sample their water for this study, as well as to the many residents who spoke with us and helped connect us with landowners who would be willing to permit sampling. Additional thanks to the efforts of Victoria Balise, Angela Meng, Annie Maas, and Kara C. Klemp for helping to receive and immediately extract the water samples upon receipt in the laboratory, and Nancy Lauer, A.J. Kondash and Gary Dwyer for their assistance with the sample preparation and measurements of inorganic and isotope values.

Many thanks to Donald P. McDonnell for the generous gift of the pSG5-AR, 2XC3ARETKLuc, 3XERETKLuc, and CMV-β-Gal plasmids, and to Dennis Lubahn for the generous gift of CMV-AR1 and PSA-Enh E4TATA-luc.

This project was supported by NIEHS R21ES026395, NIEHS R01 ES021394-04S1, Mizzou Advantage, the University of Missouri, STAR Fellowship Assistance Agreement no. FP-91747101 awarded by the US EPA (CDK), and a crowd-funding campaign via Experiment.com. Additional support throughout the writing of this manuscript was supported by NIEHS F32 ES027320 (CDK). The views and conclusions in this article represent the views of the authors and the US Geological Survey; however, they do not necessarily represent the views of the EPA. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142236.

References

- Akingbemi BT, Hardy MP, 2001. Oestrogenic and antiandrogenic chemicals in the environment: effects on male reproductive health. Ann. Med 33, 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akob DM, Cozzarelli IM, Dunlap DS, Rowan EL, Lorah M, 2015. M. Organic and inorganic composition and microbiology of produced waters from Pennsylvania shale gas wells. Appl. Geochem 60, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Akob DM, Mumford AC, Orem WH, Engle MA, Klinges JG, Kent DB, et al. , 2016. Wastewater disposal from unconventional oil and gas development degrades stream quality at a West Virginia injection facility. Environ. Sci. Technol 50, 5517–5525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez DA, Shappell NW, Billey LO, Bermudez DS, Wilson VS, Kolpin DW, et al. , 2013. Bioassay of estrogenicity and chemical analyses of estrogens in streams across the United States associated with livestock operations. Water Res 47, 3347–3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balise VD, Cornelius-Green JN, Kassotis CD, Rector RS, Thyfault JP, Nagel SC, 2019a. Preconceptional, gestational, and lactational exposure to an unconventional oil and gas chemical mixture alters energy expenditure in adult female mice. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 10, 323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]