Abstract

This article reviews and categorises early policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, based on a dataset of 496 measures taken by 54 countries between January 1 and April 28 and collected by the OECD from government officials and additional sources. Findings show a large diversity of measures, some of which were urgent and necessary, some that may continue to be beneficial once the pandemic has subsided, while others are potentially disruptive for the functioning of markets or damaging for the environment. National allocations of measures show differences between developed OECD countries, which used more agriculture or support related measures, and emerging economies, which focused on trade policies, information provision or food assistance. A minimum USD 47.6 billion was allocated by OECD governments to the agriculture and food sector, mostly in the form of domestic food assistance and support to agriculture and the food chain.

Keywords: Agriculture policy, Food policy, COVID-19

1. Introduction

In the first few months of 2020, governments in many countries affected by the COVID-19 outbreak implemented lockdown regulations to limit the diffusion of the virus in their populations. These regulations forced most sectors to limit or halt their activities, with the exception of health, agriculture and food, and a few other sectors deemed essential for the basic needs of the population.

Despite exemptions, these essential sectors faced significant challenges, due to both supply side factors (in particular health-related risks to workers with the sector, and limitations on the flows of people and products) and demand side ones (deriving from lockdowns and the economic burden imposed on a large share of the population unable to work). In the agriculture and food sector, these factors translated into three main types of impacts (Lusk et al., 2020, OECD, 2020b):

-

•

Impacts on agricultural production: Border and internal measures created seasonal labour shortages especially for fruits and vegetable production, thereby exacerbating food losses, and constraining access to agriculture inputs.

-

•

Shifts in consumer demand: Income shocks reduced the demand for high value food products and increased food insecurity (Amare et al., 2020, Bauer, 2020). Confinement measures shifted the demand for food from restaurant and caterers to staple and ready-to-eat foods and to supermarkets. A collapse in oil prices reduced the demand for biofuels.

-

•

Disruptions to the food supply chain: Processors and manufacturers were particularly affected by labour force impacts, which included workers becoming infected, absenteeism, and the effects of physical distancing and sanitary requirements. These effects were especially severe for perishable fruits and vegetables (Mahajan and Tomar, 2020), and for the dairy and meat sectors. Slower safety, quality and certification checks, as well as impediments to transport and logistics services, limited access to inputs for food production.

Governments responded to these constraints by undertaking a wide range of agriculture and food policy measures, with the objective of ensuring the continued production and delivery of affordable food to consumers, and addressing the needs of a growing vulnerable population. However, the types of policy response governments undertook varied widely across countries.

This paper analyses the first set of agriculture and policy measures undertaken by 54 OECD and emerging economies1 between January 1 and April 28, 2020. The assessment is valuable for three reasons. First, major policy decisions affecting agriculture and food were taken in the first few months of the COVID-19 crisis, when lockdowns were implemented in most OECD and G20 countries. While measures continue to be introduced, such major policy shifts warrant early inspection. Second, some of those measures may not be easily reversible, and have the potential to change the long term path of government policy – for better or worse (Barrett, 2020). Building on the emerging literature, the paper initiates a discussion on the potential medium to long term implications of responses to COVID-19 in agriculture and food. Third, as governments react to an unprecedented crisis, they are scrutinising responses in other countries, both to draw quick lessons in terms of which policies may be effective, but also to anticipate potential spill-over effect across markets. These concerns are evident from information sharing and discussions at international fora, including the OECD, FAO, the G20 and the WTO. At the same time, the comparative analysis can help shed light on whether developed and developing economies have adopted different policy responses commensurate with the age structure of their populations and economic constraints in the food sector (Alon et al., 2020).

The analysis builds on a unique set of 496 unique measures collected directly from governments, and from complementary information found on public databases and reported in the 2020 edition of the OECD Agriculture Policy Monitoring and Evaluation (OECD, 2020a).2 , 3 The investigative approach to compiling the database means that it may not be fully comprehensive. However, the fact that it is based on reports directly from officials, validated by analysts that follow these countries’ agricultural policies, provides relative confidence that it captures the key policy measures in place in the countries covered during the period of reference. While the coverage is not fully global it does span countries at a broad spectrum of development levels, and includes the largest agricultural economies. Other efforts, which may be more comprehensive in specific dimensions, have been conducted by other international organisations. The World Bank developed a living document in which it tracked over 1000 social protection measures in over 195 countries (Gentilini et al., 2020). The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) set up an online database on trade restrictions the agricultural sector (Laborde, Mamun and Parent, 2020), while the Agricultural Market Information System (AMIS) initiative monitored market and trade related policy developments that may affect the four key commodity markets that it follows (wheat, maize, soybeans and rice).4 ,The unique feature of the OECD database used in this paper, compared to those other efforts, is that it covers a broader set of measures spanning food and agriculture, from ministries’ administrative decisions, to international agreements, labour measures, biosafety protocols, and producer and consumer assistance.

The following section of the paper presents a categorisation of measures undertaken by governments. The third section discusses their significance and potential implications for the sustainability and resilience of the sector. The last section draws a few take away messages and identifies areas for further investigation.

2. Categorising the diversity of policy responses

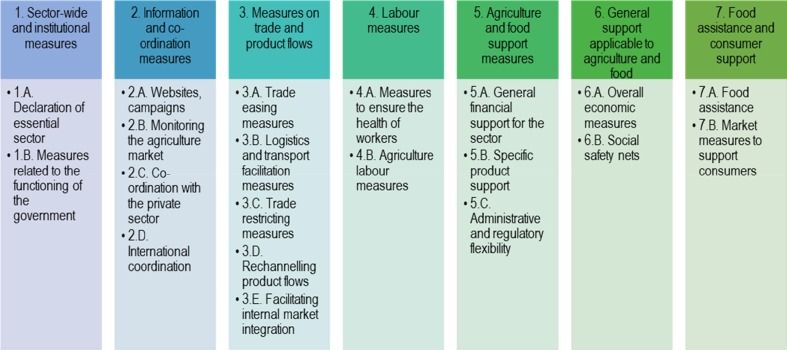

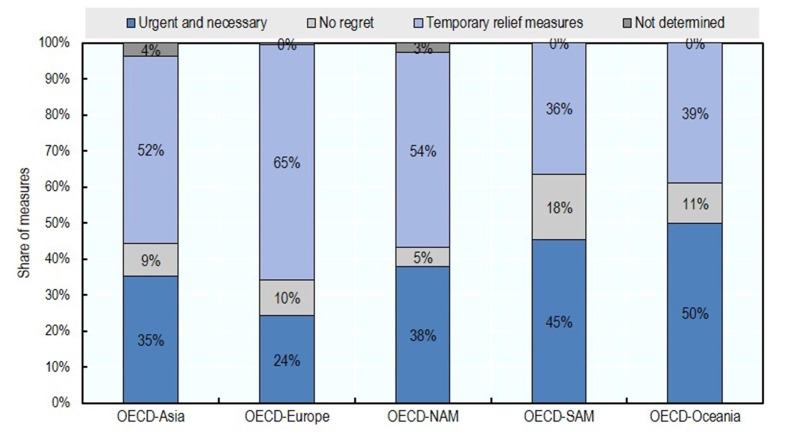

A diverse set of agriculture and food related measures were taken by governments in response to the crisis, focusing on agricultural production, the functioning of the food chain and consumer demand.5 OECD (2020a) orders these measures into seven broad categories:6 1) Sector-wide and institutional measures, 2) Information and co-ordination measures, 3) Measures on trade and product flows, 4) Labour measures, 5) Agriculture and food support measures, 6) General support applicable to agriculture and food, 7) Food assistance and consumer support. Each of these categories is further separated into 20 sub-categories of measures, as indicated in Fig. 1 and illustrated in Table 1 .

Fig. 1.

Agriculture and food policy actions in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. Source: OECD (2020a).

Table 1.

Examples of countries and specific measures by sub-category.

| Sub-category | Examples of countries | Examples of specific measures |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Sector-wide and institutional measures | ||

| 1.A. Declaration of essential sector | All countries with lockdowns (e.g., OECD countries except Korea). | In Australia, farming, food and beverage production, livestock sale yards and wool auctions and those who support these businesses, including food markets and food banks were exempt from indoor and outdoor gathering restrictions. |

| 1.B. Measures related to the functioning of the government | Canada, Costa Rica, Greece, Mexico, Norway or the US. | In Israel, a limited number of “essential” employees were allowed to continue their work activities in the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD). Services in farms and ports of entry have continued. |

| 2. Information and co-ordination measures | ||

| 2.A. Websites, campaigns | China, Germany, Iceland, India, Ireland, or Japan. | In Ireland, a Regional Farm Labour Database was established to link farming families with available relief workers in the event that a farmer contracts COVID-19. |

| 2.B. Monitoring the agriculture market | Chile, the EU, Norway, or South Africa. | In Norway, the Ministry and the Norwegian Agriculture Agency closely monitored the situation regarding access to food in the international market. |

| 2.C. Co-ordination with the private sector | Canada, Denmark, Mexico, Poland or the UK. | In Canada, the government established an Industry-Government COVID-19 working group made up of national sector organisations, who meet by phone three times per week to share information and discuss issues facing industry. |

| 2.D. International coordination | G20 members, Latin American countries, or selected WTO members. | Agriculture ministers of the G20 adopted a statement in which they discouraged trade restrictions, stressed the need to take the necessary actions to improve the functioning of food chains, and to support affected populations. |

| 3. Measures on trade and product flows | ||

| 3.A. Trade easing measures | Colombia, India, Israel, Portugal or Switzerland. | Colombia decreased tariffs to 0% for imports of yellow maize, sorghum, soybeans and soybean flour until June 30, 2020, with a possibility of renewal of three months. |

| 3.B. Logistics and transport facilitation measures | Argentina, Brazil, Canada, China, EU, Latvia, Spain, or the UK. | The European Union created “Green Lanes” through which shipments of goods (including food and livestock) are able to cross borders in 15 min or less, including any checks or health screenings. |

| 3.C. Trade restricting measures | Bulgaria, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, or Viet Nam. | In Viet Nam, on March 25, the government temporarily suspended rice exports. The decision was subsequently reversed in favour of a monthly quota for rice exports. |

| 3.D. Rechannelling product flows | Japan, Korea the Philippines or the US. | In the United States, USDA purchased fresh produce, dairy, and meat from affected food distributors, to be delivered to food banks and non-profit organisations. |

| 3.E. Facilitating internal market integration | China, Costa Rica, India, Ireland, Israel, Lithuania, or Korea. | In China, central and local governments supported e-commerce as an alternative channel for the purchase and distribution of agricultural inputs, such as seeds, fertilisers, sprinklers, and other agricultural machinery. |

| 4. Labour measures | ||

| 4.A. Measures to ensure the health of workers | Argentina, Denmark, Japan, New Zealand, or Turkey. | In Japan, the Ministry of Agriculture Food and Forestry developed operation guidelines for farmers and food business operators in case one of the workers got infected by Covid-19 and made it available online. |

| 4.B. Agriculture labour measures | Australia, Austria, Estonia, Finland, Hungary, Italy or Korea. | In Korea, the government implemented several policy measures to increase the sector’s attractiveness. Visa regulations were temporarily alleviated to allow foreign visitors or migrant workers from other industries to work for the agricultural sector. |

| 5. Agriculture and food support measures | ||

| 5.A. General financial support for the sector | Brazil, China, India, EU member states, Kazakhstan, or Mexico. | In India, The central government granted the 3% prompt repayment incentive (PRI) to all farmers for all short-term crop loans of maximum INR 300 000 which were due up to 31 May 2020, even if farmers failed to repay loans until this date. |

| 5.B. Specific product support | Belgium, Croatia, Iceland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, or Portugal. | In the Netherlands, compensation schemes were announced for horticultural producers who have experienced severe losses due to declining demand, and for French fry potato growers experiencing demand downfalls. |

| 5.C. Administrative and regulatory flexibility | Czech Republic, France, Germany, or Spain. | In Spain, the enrolment period for agricultural insurance contracts was extended, and the government also relaxed documentation requirements for animal transport. |

| 6. General support applicable to agriculture and food | ||

| 6.A. Overall economic measures | EU Member states, New Zealand, or the US. | In New Zealand, food producers were eligible together with other business to benefit from the stimulus package, more than half of which to be disbursed by mid-June. |

| 6.B. Social safety nets | Brazil, Chile, Denmark, Indonesia, or Russia. | In Indonesia, a social safety net program provided support for essential goods, including free electricity, housing support, essential goods and education. |

| 7. Food assistance and consumer support | ||

| 7.A. Food assistance | Australia, Canada, China, Italy, or the UK. | In the United Kingdom, digital supermarket vouchers were provided to low-income families with children in lieu of free school meals from shuttered schools. |

| 7.B. Market measures to support consumers | Croatia, the Philippines, Poland, Slovenia. | In the Philippines, a 60-day price freeze for basic goods and agriculture products nationwide was implemented. Prices were monitored. |

Source: Derived from OECD (2020a).

As Table 1 displays, each of the covered countries employed different sets of measures in response to the COVID-19 crisis. Table A1 in the Appendix provides a count of measures of reported measures by country and category that further exemplifies this diversity; some countries applied measures in few categories, others covered all categories. The following section uses the seven categories of Fig. 1 to further categorise the type of measures undertaken by governments.

3. Distribution, scope, and indicative implications of the policy responses

This section analyses and discusses the distribution and types of measures undertaken by the 54 covered countries from January 1 to April 28, 2020. To draw observations about the numbers and category of measures, we used the total number of unique measures reported by each country and that of the EU separately. However, when considering regional or national differences in the use of measures, we also counted EU measures as applied to each EU member state. While this inflates the number of measures for these countries, it is a more faithful representation of the measures that apply to each country.

At the outset, it should be noted that the number of measures is an imperfect means to gauge engagement, as a single measure could have large effects while a group of smaller measures could have minimal implications. Still, it is assumed here that the distribution of the number of measures across different categories can give some indication of areas of particular emphasis for governments. Crossed with the type of measures employed, this can provide a sense of overall directions of the policy responses taken in the first four months of 2020, as done by Gentilini et al. (2020) for social protection and job measures. Partial measures of budget and stringency are also used in this section to provide complementary information.

4. Emphasis of government measures

4.1. Overall categorical distribution of measures

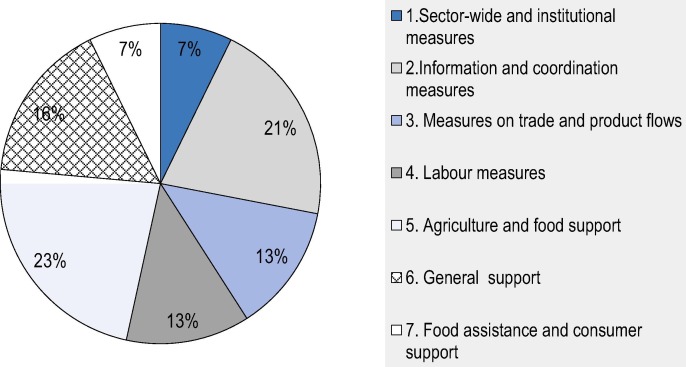

The number of measures are unevenly distributed among above-define 7 categories. The most frequently observed measures belong to category 5 (representing close to a quarter of total measures) on agriculture and food support, followed by categories 2, 6, 3 and 4 that cover information, general economic support, trade and product flows, and labour measures (Fig. 2 ). At the same time, within each category, over 80% of countries undertook at least one measure, and 60% of the covered countries had measures covering all seven categories (Fig. 3 ). Furthermore both information and coordination measures and measures on trade and product flows can be found in practically all countries.

Fig. 2.

Total number of measures by category Source: Derived from OECD (2020a).

Fig. 3.

Proportion of categories of measures adopted by countries and number of categories covered Source: Derived from OECD (2020a).

This suggests that a large majority of country introduced wide set of measures to support their agricultural sector, encompassing information, coordination, market and trade measures. In addition, governments undertook a particularly large number of agriculture and food support measures.

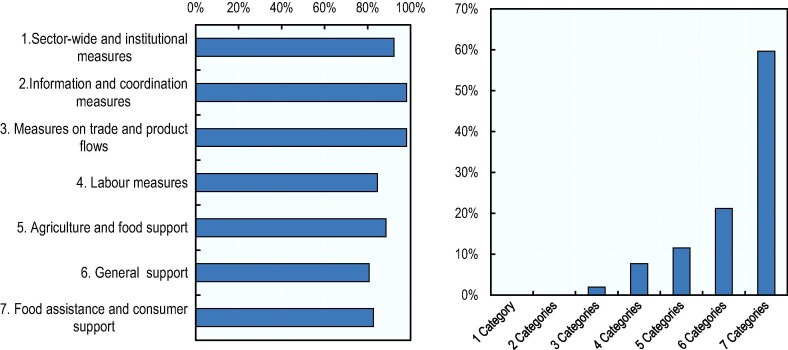

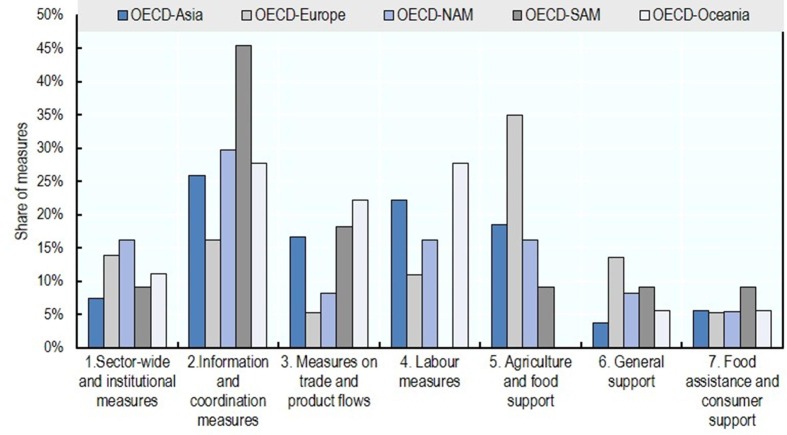

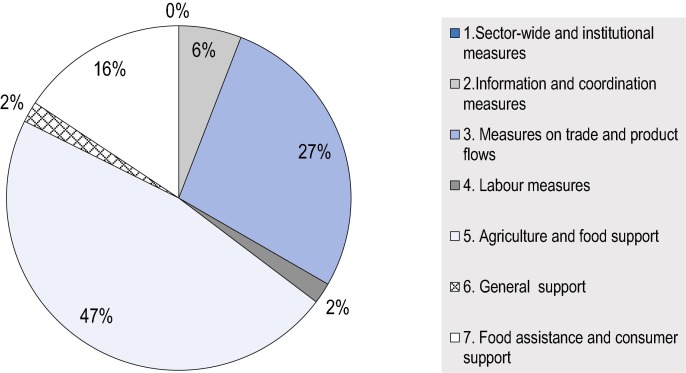

4.2. Distribution across OECD and emerging economies

Looking at cross-country differences, OECD (mostly developed) and non-OECD emerging economies implemented a different balance of measures (Fig. 4 ). OECD countries introduced twice as many measures on average as non-OECD emerging economies (although the covered set of countries include more OECD countries). More specifically, measures in OECD countries focused largely on agricultural support (category 5) and information and coordination (category 2). In contrast, emerging economies adopted primarily measures related to trade flows (category 3) and information and coordination measures (category 2). The cross-regional differences under categories 3 (product and trade flows) and 5 (agriculture and food support) are also the largest across all categories. OECD countries also introduced general support measures (category 6) with a share of total measures that was twice as large as that of emerging economies, while the reverse can be observed on food assistance and consumer support measures (category 7), as shown in Fig. 5 .

Fig. 4.

Distribution of measures by categories, OECD and emerging economies. Source: Derived from OECD (2020a).

Fig. 5.

Distribution of measures by category and OECD sub-regions. Source: Derived from OECD (2020a).

These differences may be explained by existing commitments to government spending and by income levels. The prevalence of agricultural support in OECD countries is consistent with a historical tendency to support the sector; a trend that is only emerging in other countries. In contrast, a number of emerging countries in the dataset are large traders of food, with relatively low agricultural support (OECD, 2020a). The differences between OECD and non-OECD countries also reflect differences in funding capacity and in the focus of government spending under crisis (Alon et al., 2020). Differences in the rates of general support and food assistance can be attributed to the higher share of food in total expenditures in lower income countries. A loss in income will affect the food security of many households, as seen for instance in Nigeria (Amare et al., 2020).

Significant variations can also be seen across OECD regions. Over a third of measures undertaken by OECD European countries were found in the category of agriculture and food support measures, whereas these measures were not introduced in the OECD countries of Oceania, which use very limited agriculture support. Over 45% of measures in Chile7 were information and coordination measures (category 2). Close to half of the measures implemented by Oceanian and by Asian OECD countries are in categories 2 and 4 on information, coordination and labour. North American countries implemented measures that focused on information and coordination (category 2), and also introduced sector-wide and institutional measures, labour, and agriculture and food support measures (categories 1, 4 and 5) in identical proportions (representing 16% of their total). Japan and Korea undertook a number of often innovative information and coordination measures compared to other countries (OECD, 2020a).

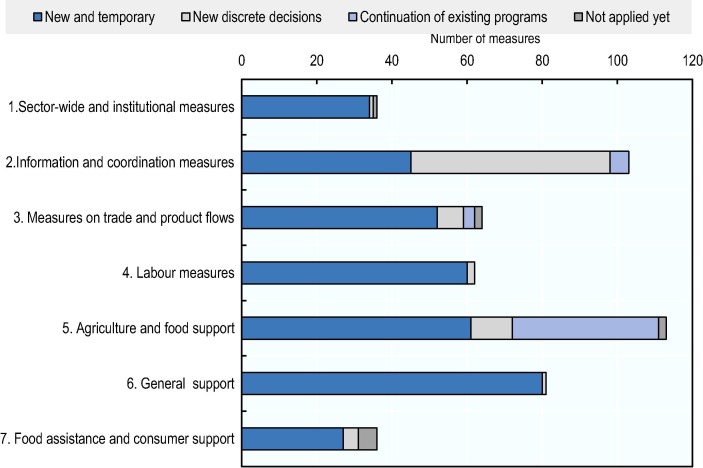

4.3. New policies vs reformulated existing polices

Interestingly, few of the unique measures—9% of the total—built on existing policy programs. The large majority of measures were new and temporary (73%) or new discrete (lasting) decisions (16%) that changed a policy without setting any particular limit. Some measures were announced but not applied yet (Fig. 6 ).

Fig. 6.

Measures’ novelty and dynamics. Source: Derived from OECD (2020a).

In most OECD countries and emerging economies, these measures were undertaken in contexts with complex pre-existing agriculture and food policies and regulations (OECD, 2020a). While some governments adapted existing policies and support mechanisms to respond to this new situation, many of the response measures were added to the existing set of support measures. This raises the question of whether new support and existing support may be reinforcing each other, overlapping in ways that make one policy redundant, or counteracting each other. An example of the latter was China releasing stocks of rice and procuring more rice at the same time.

4.3.1. Reported public expenditures

Budgetary expenditures provide a complementary indication of the importance of different measures. Unfortunately, the dataset does not include specific budgetary expenditure for every measure.8 Instead some of the largest programs and initiative were reported.

Table 2 gives a decomposition of these reported budget by category of measure. In total, a minimum USD 47.7 billion had been assigned to agriculture and food measures as of April 2020. As expected this budget was spent almost entirely on food assistance and agriculture and food support measures. Nearly all of this amount (USD 47.6 billion) was allocated in OECD countries. Within the OECD, the largest share of the budget, or over USD 45.9 billion, was reported by North America countries, with Europe (USD 1.3 billion), Oceania (USD 0.4 billion) and Asia (USD 0.02 billion) following. The sector also benefited from general economic measures, including recovery packages, in many countries, the total of which exceeds USD 1.5 trillion in the countries covered in the dataset.

Table 2.

Reported budget by category of measure.

| Category of measure | Minimum budgetary expenses (USD million) |

|---|---|

| 1. Sector-wide and institutional measures | 160 |

| 2. Information and co-ordination measures | 168 |

| 3. Measures on trade and product flows | 3 383 |

| 4. Labour measures | 71 |

| 5. Agriculture and food support measures | 14 036 |

| 6. General support applicable to agriculture and food1 | 1 517 305 |

| 7. Food assistance and consumer support | 29 977 |

| Total for agriculture and food specific measures2 | 47 738 |

| Total for all measure | 1 565 043 |

Notes: 1. These measures apply to multiple sectors. 2. All categories except general support measures (category 6).

Source: Derived from OECD (2020a).

The geographical repartition of this incomplete budget information is partially consistent with the trends in number of measures, in that OECD countries used more support measures than others, but it also diverges when considering more specific measures. Counts of measures are not a good proxy for budgetary importance, and could misrepresent the importance of a government’s response. Moreover, the association only makes sense for measures that inherently require budgetary spending (belonging mostly to categories 5, 6 and 7). In particular, setting up green lanes will not be expensive, but can be extremely powerful in ensuring the functioning of agriculture and food supply chains.

Nonetheless, the estimated minimum budget of USD 47.7 billion represents significant spending in four months, even if the amount is small in the context of total annual support provided by consumers and taxpayers to the agricultural sector, which exceeded USD 700 billion in 2017–19 across all 54 countries surveyed.

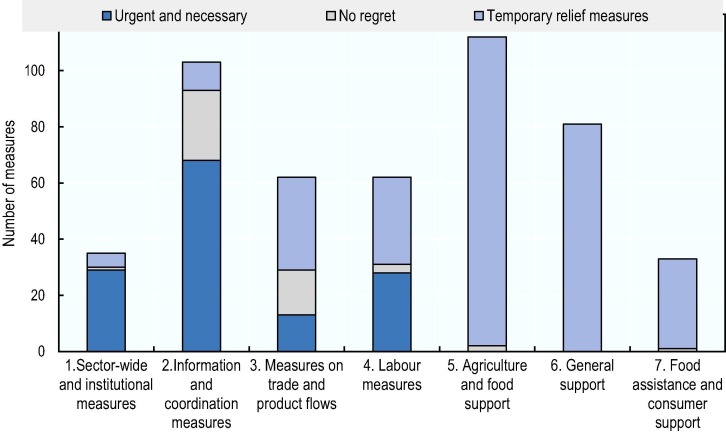

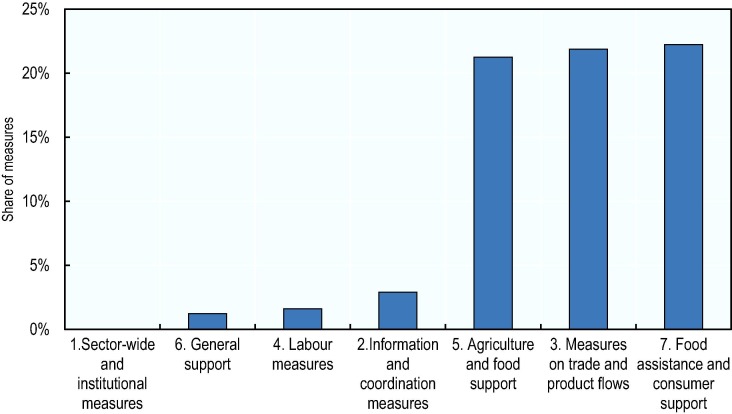

4.3.2. Policy objectives, indicative implications and exit strategies

To better understand the possible implications of the policy responses, measures were sorted into three groups according to their timing and scope. The proposed classification aims to illustrate the range of measures and their possible implications. It offers a plausible grouping of measures, although for some subcategories of measures the assignation and boundaries could be debatable. The three groups of measures are defined as follows.

-

•

Urgent and necessary measures: These emergency measures are absolutely necessary to safeguard the safety of workers and ensure the minimum functioning of the agriculture value chains. Examples include declaring that the food sector is exempted from lockdown or setting up green lanes to facilitate markets. These measures are unambiguously meant to be eliminated as soon as either lockdowns are removed or the safety of workers can be guaranteed. This group includes 138 unique measures (28% of the total).

-

•

No regret measures: These measures would be beneficial for the food and agriculture sector even outside of the crisis period, such as the setting up of digital solutions to ease marketing and trade, training measures, or some trade facilitating measures. This group includes 48 unique measures (10%).

-

•

Temporary relief measures: This group includes all other measures. They are deemed necessary to contain the impacts of the crisis on producers, consumers and other agents along the food chain for the proper functioning of the food system, but they need to include sunset clauses to avoid translating into systemic support in the long run. This category includes administrative flexibilities, different type of agriculture or consumer support, and other measures. This group includes the remaining 302 unique measures (62%).

Consistent with these definitions, most of the urgent and necessary measures are in categories 1 to 4, covering sector-wide and institutional measures, information and coordination, trade and product flows and labour measures (Fig. 7 ). No-regret measures are largely found in categories 2 and 3 on information and coordiation and on trade and product flows. Temporary relief measures include all general support measures (category 6) and almost all agriculture and food and consumer support measures (categories 5 and 7).

Fig. 7.

Distribution of measures by group and category. Source: Derived from OECD (2020a).

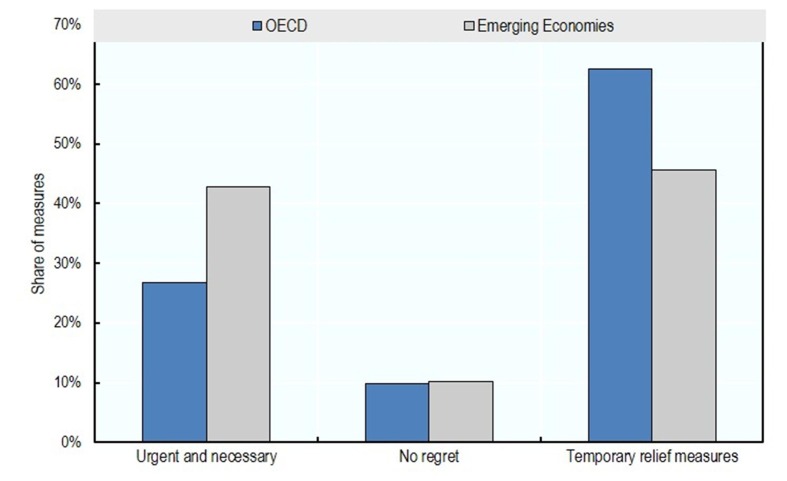

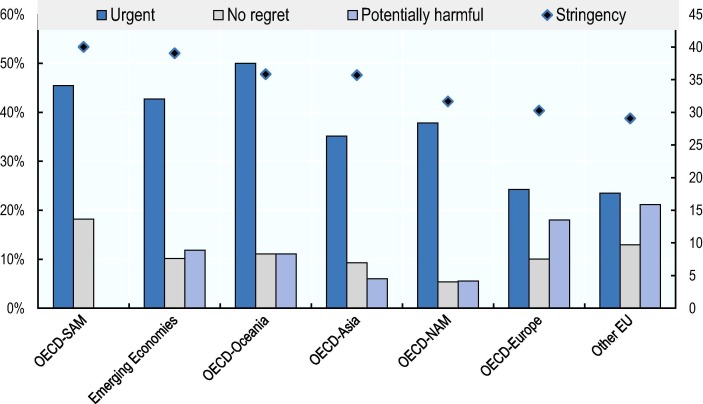

As shown in Fig. 8 , neither OECD nor emerging economies have introduced a large share of no regret measures (10% each). The principal difference between the two groups is that OECD countries have introduced a larger proportion of temporary relief measures than emerging economies, while the reverse is observed in the case of urgent and necessary measures. These differences, if commensurate with the importance of government actions, are in line with the propensity of OECD countries to use funding for relief measures.

Fig. 8.

Distribution of measures by groups and regions. Source: Derived from OECD (2020a).

Slight differences are also observed among OECD regions (Fig. 9 ). OECD Oceanian countries had a relatively larger proportion of urgent and necessary measures, OECD South America (Chile) has a relatively larger proportion of no regret measures, and Asian, European and North American countries included a larger set of measures belonging to the group of temporary relief measures.

Fig. 9.

Proportion of measures by group within OECD regions. Note: NAM: North America; SAM: South America. Source: Derived from OECD (2020a).

While urgent and necessary measure may not be needed to the same extent in each country, no regret policies should be encouraged everywhere as they offer long term benefit, potentially bolster the sector’s resilience and do not create distortions in the long run. At the same time, temporary relief measures include social and food assistance measure that could be warranted so long as the economies are shocked, particularly in developing countries. Agriculture support measures in OECD countries, which often aim to support farmers’ income in the face of demand drops, will need more immediate sunset clauses, commensurate with the lifting of market restrictions, to avoid introducing further market distortions into already distorted agriculture markets.

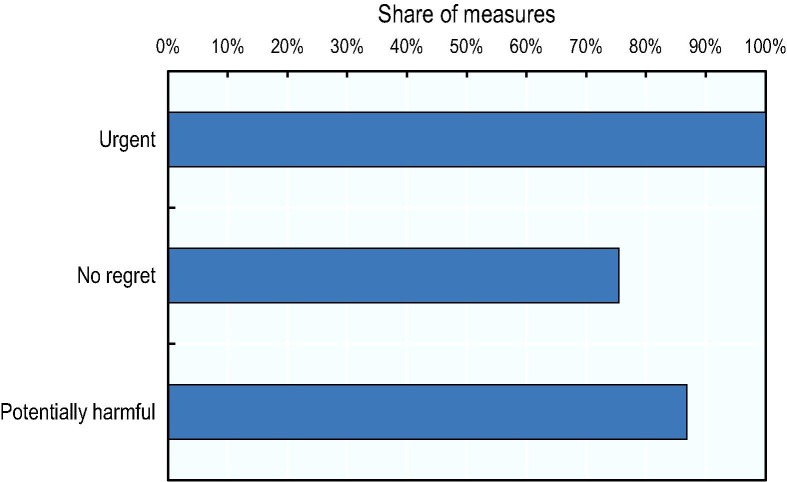

4.4. Distribution and types of measures with potentially negative consequences on markets, trade or the environment

Within the group of temporary relief measures, some measures have the potential to disrupt markets and trade, and to aggravate environmental stresses. These include trade restrictions and specific support to particular commodities, as well as the relaxation of environmental regulations, and should therefore be lifted as soon as possible. Fifty-two measures (10.5% of total unique measures) were identified in this subgroup, mostly belonging to categories 5, 3 and 7, focusing on agriculture and food support, product and trade flows and food assistance and consumer support (Fig. 10 ).

Fig. 10.

Distribution of measures with potentially negative consequences for markets, trade or the environment across categories. Source: Derived from OECD (2020a).

As shown in Fig. 11 , these potentially market distorting or environmentally harmful measures represent above 20% of measures applied in the agriculture and food support, trade and product flows and food assistance (5, 3 and 7) categories, and less than 5% of measures applied in other categories. At the same time 87% of countries applied potentially harmful measures for markets, trade or the environment, a proportion inferior to that for urgent measures but larger than the one for no regret measures (Fig. 12 ).

Fig. 11.

Percentage of measures with potentially negative consequences on markets, trade or the environment n in each category of measures. Source: Derived from OECD (2020a).

Fig. 12.

Proportion of countries adopting measures that are urgent, no regret or with potentially negative consequences on markets, trade or the environment. Note: Potentially harmful measures are measures with potentially negative consequences on markets, trade or the environment. Source: Derived from OECD (2020a).

Measures with potentially negative consequences for markets, trade or the environment were found to be mostly temporary and new (62%), or building on existing policies (23%). Still, 12% of these measures were new measures that may last beyond the crisis if not reconsidered promptly. They also represented 16% of measures adopted in OECD countries, and 12% of measures undertaken by governments in emerging economies.

4.5. Stringency of lockdowns and emphasis of responses

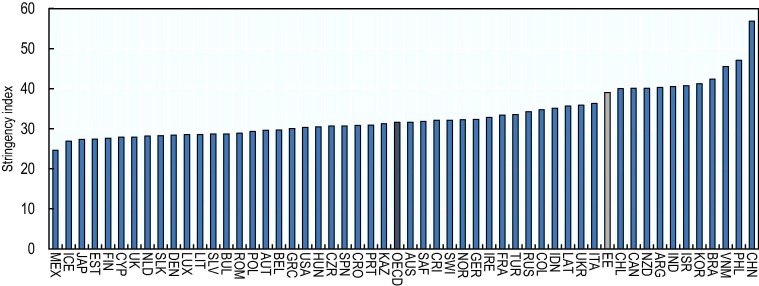

Responses by governments on agriculture and food were largely related to the application of lockdowns and their consequences. To consider this factor, averages of the University of Oxford’s government stringency index (Hale et al., 2020), taken between January 1 and April 28 were derived for all the covered countries. As shown in Fig. 13 these indices vary from 25 to 56, with larger indices indicating more stringent measures during that period.

Fig. 13.

Average government stringency indices (January 1-April 28). Note: OECD: average for OECD countries, EE: average value for emerging economies. Source: Derived from Hale et al. (2020).

Of interest, the sample average of the stringency index was larger for emerging economies (EE on Fig. 13) than for OECD countries during this period. This was the case for Asian countries in particular, which were perhaps more aware of the urgency of reaction from their experience with the previous SARS virus. But it also applies to several South American countries, which had low infection rates early on but have large agglomerations of relatively poor populations.

The fact that governments in emerging countries adopted stringent overall responses to the virus outbreak, together with possible concerns on food security, may explain why their early agriculture and food measures with response to COVID-19 focused on information coordination, trade and market measures, while initiating food assistance and consumer support programmes. In contrast, governments in many OECD countries, which did not implement as strong lockdown measures, appear to have prioritised measures on overall social and business support, farm support and labour measures.

No statistical relationship could be drawn between the number of measures and the stringency of government responses. At the same time, Fig. 14 suggests that regions with higher stringency indices may have had higher proportions of urgent measures than others and regions with relatively lower stringency indices have more potentially harmful measures for markets, trade or the environment. Still no definitive conclusion can be drawn from this preliminary data analysis.

Fig. 14.

Proportion of measures by group and stringency of government responses. Left axis: proportion of measures, right axis stringency index. Notes: Urgent: urgent and necessary measures; Potentially harmful: measures with potentially negative consequences on markets, trade or the environment; SAM: South America; NAM: North America; Other EU: EU member states that are not OECD countries. Source: Derived from OECD (2020a).

5. Conclusion: Moving towards a robust and resilient recovery

This article provides an overview of early policy responses undertaken by governments in response to the COVID-19 outbreak and associated lockdown policies. While it does not consider the effectiveness of adopted measures, it is clear that those adopted as a matter of urgency by the countries covered in this article played a critical role in ensuring the continued delivery of food to markets and in supporting a large population facing major income shortfalls. Government measures also helped the value chain to redirect food products from traditional public and private catering services to retailers and food banks. The crisis encouraged changes that were needed pre-crisis and are likely to deliver a better functioning of agriculture and food sector in the future, such as improved information on market condition, and coordination among stakeholders. Furthermore, some governments provided innovative responses to key challenges for the sector. These were achieved with limited expenditures but likely positive effects and may provide examples for others to follow in future crises.

At the same time, other measures, while most often temporary, were likely detrimental to the functioning of the sector as a whole, with adverse effects on consumers (import restrictions or local promotion measures), producers (export restrictions), food chain actors (market distorting measures), and the environment (regulatory relaxations, input subsidies). This was done despite national, regional and international calls, statements and agreements to avoid measures that would impede the smooth functioning of domestic and international markets. The effects of these measures will need to be assessed when the crisis is over, to help all actors learn lessons ahead of future new crises. By aiming to support some actors at the detriment of others, they also may have impacted the actual resilience of the entire food system, even if temporarily.

The analysis of the distribution of the measures undertaken by 54 countries during the first four months of 2020 provides some early insights into emphasis, scope and regional diversity of policy responses. Emerging economies, which on balance had more stringent lockdowns than OECD countries, focused their attention on trade and market interventions, information and coordination and food assistance measures, and more particularly on measures that were urgent and necessary. By contrast, OECD countries relied more on support measures, be that in the form of agriculture and food sector support, general economic assistance, or temporary relief measures. South American and Oceanian OECD countries undertook a relatively larger share of urgent or no-regret measures than Asian, North American and European members. 16% of the measures taken by OECD countries could also be “potentially harmful”, in the sense of disrupting markets and trade or leading to negative environmental outcomes, with higher proportions for OECD and non-OECD European countries. Lastly, a first and incomplete review of announced expenditures suggest that at least USD 48 billion was spent on the sector, with most expenses in North American countries, focusing on food assistance and agriculture and food support measures. This is a significant amount, but only represents about 7% of the total support that these countries provided to their agriculture sectors in 2019.

More analysis will be needed on the key measures undertaken by each country, to gauge their effectiveness and overall costs, when data become available. More broadly, a better understanding of the measures taken will be needed to understand which have the potential to strengthen the resilience of the agriculture and food sector in the face of future crises, not least those associated with climate change.

6. Disclaimer

The first section of this article, which describes policy responses, draws on OECD (2020a). Views reflected in this article do not necessarily reflect that of the OECD or its member countries.

Footnotes

37 OECD countries (mostly a developed country group, with the EU coverage also extending to some non OECD members) and 13 emerging economies: Argentina, Brazil, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, the Philippines, Russia, South Africa, Ukraine and Viet Nam.

Unique measures count European Union measures separately from its member states (including the United Kingdom). If considering that EU measures are applied in covered member state countries, as done in part of section 2, the total goes up to 979.

It is envisioned that a more complete exercise will be conducted in 2021, enabling to gauge whether governments have reoriented their policy responses.

It should be noted that not all countries faced the virus at the same time. Lockdowns and resulting agriculture measures may vary across countries with the dynamics of the virus.

While categories were designed to be mutually exclusive, a few measures could be considered to belong to two of the seven categories. These measures were grouped with the closest respective category in order to avoid double counting.

Chile is the only South American OECD country in the dataset. Colombia joined the OECD on April 28, 2020 so it was not considered an OECD country in this paper.

An analysis of agriculture-related budgetary expenses and support measures will be compiled for the entire year 2020 in the 2021 edition of the OECD Agriculture Monitoring and Evaluation Report.

Appendix.

(See Table A1 )

Table A1.

Number of measures by category and country in the dataset.

| 1.Sector wide & institutional | 2.Information & coordination | 3.Trade & product flow | 4. Labour | 5.Agriculture & food support | 6. General support | 7.Food assistance & consumer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Australia | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Belgium1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Brazil | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Bulgaria1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Canada | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Chile | 1 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| China | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Colombia | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Costa Rica | 2 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Croatia1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Cyprus1 | 1 | ||||||

| Czech Republic1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Denmark1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | ||||

| Estonia1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | ||||

| European Union2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| Finland1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| France1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | |||

| Germany1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Greece1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | |||

| Hungary1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||||

| Iceland | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Indonesia | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| India | 2 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 1 | |

| Ireland1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Israel | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| Italy1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | |

| Japan | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |

| Kazakhstan | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Korea | 6 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Latvia1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | |||

| Lithuania1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Luxemburg1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | ||||

| Mexico | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Netherlands1 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Norway | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | ||

| New Zealand | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Philippines | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Poland1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Portugal1 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Romania1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Russ | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| South Africa | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| Slovakia1 | 3 | ||||||

| Slovenia1 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Spain1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Switzerland | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Turkey | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Ukraine | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| United Kingdom1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| United States | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Viet Nam | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Notes: 1. Also applied measures adopted by the European Union. 2. Measures apply to all 2020 EU Member States (i.e., UK included). Source: Authors based on OECD (2020a).

References

- Alon, T. et al. (2020), How should policy responses to the COVID-10 pandemic differ in the developing world?, National Bureau of Economic Research, http://www.nber.org/papers/w27273.

- Amare M., et al. International Food Policy Research Institute; 2020. Impacts of COVID-19 on food security: Panel data evidence from Nigeria. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett C. Actions now can curb food systems fallout from COVID-19. Nature Food. 2020;1:319–320. doi: 10.1038/s43016-020-0085-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, L. (2020), Hungry at Thanksgiving: A Fall 2020 update on food insecurity in the U.S., https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/11/23/hungry-at-thanksgiving-a-fall-2020-update-on-food-insecurity-in-the-u-s/ (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Gentilini, U. et al. (2020), Social Protection and Jobs Responses to COVID-19, Living paper, June 12 2020; World Bank, Washington DC, http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/590531592231143435/pdf/Social-Protection-and-Jobs-Responses-to-COVID-19-A-Real-Time-Review-of-Country-Measures-June-12-2020.pdf.

- Hale, T. et al. (2020), Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Blavatnik School of Government. Data use policy: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY standard., https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker.

- Laborde, D., A. Mamun and M. Parent (2020), COVID-19 Food Trade Policy Tracker [dataset], International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Washington DC, https://www.ifpri.org/project/covid-19-food-trade-policy-tracker.un.

- Lusk, J. et al. (2020), Economic Impacts of COVID-19 on Food and Agricultural Markets, CAST Commentary, Council for Agricultural Science and Technology (CAST), Ames, IA., https://www.cast-science.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/QTA2020-3-COVID-Impacts.pdf.

- Mahajan K., Tomar S. Covid-19 and supply chain disruption: evidence from food markets in India. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ajae.12158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD (2020), Agriculture Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris., Doi: 10.1787/928181a8-en.

- OECD (2020), COVID-19 and the Food and Agriculture Sector: Issues and Policy Responses, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=130_130816-9uut45lj4q&title=Covid-19-and-the-food-and-agriculture-sector-Issues-and-policy-responses.