Abstract

Objectives

The overall study aim was to synthesise understandings and experiences regarding the concept of spiritual care (SC). More specifically, to identify, organise and prioritise experiences with the way SC is conceived and practised by professionals in research and the clinic.

Design

Group concept mapping (GCM).

Setting

The study was conducted within a university setting in Denmark.

Participants

Researchers, students and clinicians working with SC on a daily basis in the clinic and/or through research participated in brainstorming (n=15), sorting (n=15), rating and validation (n=13).

Results

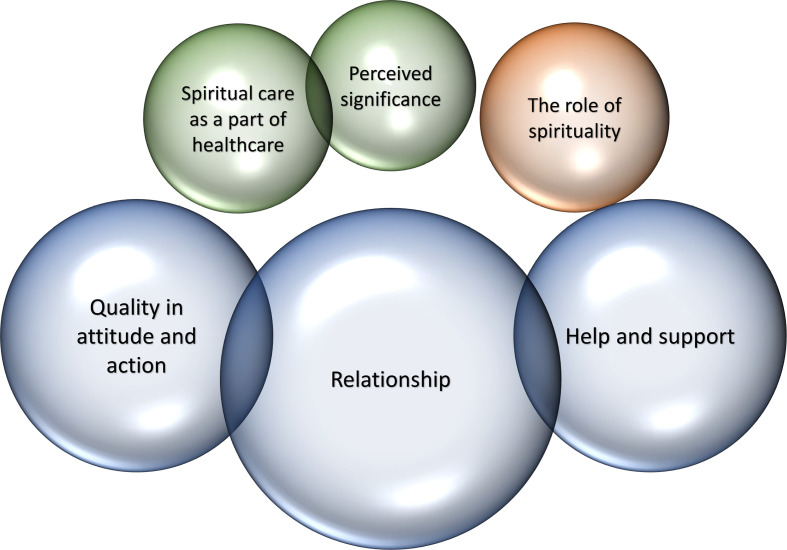

Applying GCM, ideas were identified, organised and prioritised online. A total of 192 unique ideas of SC were identified and organised into six clusters. The results were discussed and interpreted at a validation meeting. Based on input from the validation meeting a conceptual model was developed. The model highlights three overall themes: (1) ‘SC as an integral but overlooked aspect of healthcare’ containing the two clusters SC as a part of healthcare and perceived significance; (2) ‘delivering SC’ containing the three clusters quality in attitude and action, relationship and help and support, and finally (3) ‘the role of spirituality’ containing a single cluster.

Conclusion

Because spirituality is predominantly seen as a fundamental aspect of each individual human being, particularly important during suffering, SC should be an integral aspect of healthcare, although it is challenging to handle. SC involves paying attention to patients’ values and beliefs, requires adequate skills and is realised in a relationship between healthcare professional and patient founded on trust and confidence.

Keywords: medical ethics, rehabilitation medicine, palliative care, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

One strength of this study of professionals’ perspectives on what constitutes spiritual care in Denmark was that participants involved represented researchers, students and clinicians all addressing ‘existential and spiritual care’ in their professional work.

We employed a method that is recognised for the mapping of understandings of spiritual care: group concept mapping, with more than required number of participants involved in all the research phases (data generation, analyses, validation of results, discussion) which also strengthening the validity and reliability of the study.

The number of statements generated was high and despite removal of more than 40% of the ideas due to redundancy, the remaining number of ideas included in the analysis was close to recommended maximum of 200 statements. This strength implied the challenge of management of statements in the third phase of the analysis, a limitation we countered by paying close attention to rigorous methodology.

Fewer statements might lower the richness of the material, but it also facilitates increased depth with the analytical process leading to the conceptual model.

As this research project centred on professional perspectives on spiritual care, we only included professional users in the study, however, the need for the present study was identified by the base patient user panel of our research group that we consult ongoingly.

Background

The number of international research articles concerning spirituality and spiritual care (SC) and the relationship between spirituality and health have increased exponentially throughout the past decades.1 In the research literature, ‘spirituality’ tends to be understood as a collective designation for the interior life with its convictions, practices, emotions and sources of meaning that are present as a source of hope and energy in every person.2–4 SC, on the other hand, is broadly understood as a type of care that addresses and seeks to meet existential and spiritual needs and challenges in connection with illness and crisis.2 3 5–15

Research has shown that SC increases the quality of life of patients.16–26 Failure to provide SC is associated with existential and spiritual distress, which again is associated with risk of depression and reduced health, with increased healthcare costs as a consequence.27 Spirituality is described as particularly important during a crisis, whether such spirituality involves religious convictions or just the open-mindedness towards ‘more between heaven and earth’.28 29 The growing research on SC has shown that life-threatening illness often leads to an intensification of spiritual considerations and needs. These intensify in step with the severity of disease as well as prospect of imminent death.30 31 The same tendency is found in Denmark, one of the most secular cultures in the world, where research has shown a relationship between the severity of illness and increase in existential and spiritual needs and considerations.32 Consequently, there is a growing necessity to address spiritual needs among cancer patients who experience an immensely present fear of death.33 Particularly, senior patients with cancer, have frequent experiences of ‘existential loneliness’ and feelings of ‘invisibility’, longing for opportunities to discuss death and spiritual needs with peers, hereby increasing their risk of isolation and depression,34 especially during crisis such as the COVID-19 crisis.35–37

Some of the reasons given for not prioritising SC is lack of time and money. However, a recent US Harvard study suggests that it is not feasible to neglect SC as patients who felt spiritually well-supported cost half of those who did not the last week prior to death; for ethnical minorities and for religious people, the difference was even higher. The authors argue that the patients who receive limited SC experience more worries, anxiety, shortness of breath, pain increasing the probability that they will be hospitalised and die at intensive care units (ICUs), instead of at home. Limited access to SC is not only a large strain on the dying persons and their relatives, it is also expensive for society in terms of added healthcare costs.38

But what is the role of SC within cultures, that are more secular than the US culture? Research projects from Scandinavian research institutions have given an insight into Scandinavian patients’ and relatives’ spiritual needs (see publications at www.faith-health.org/?p=5592). The Scandinavian research projects show that illness activate often dormant spiritual needs. This seems particularly to be the case for Denmark, which international sociologists characterise as ‘the least religious society in the world’.39 Religiosity is described as among the largest taboos in Denmark, as religion is often relegated to the private sphere, partly inspired by trends in Lutheran thinking, partly inspired by natural science discourse and positivist philosophy.40 41 Religion is of limited significance in the public domain and is very difficult to verbalise for Danes.42 This is, however, not the same as stating that Danes are non-believers. Anonymous surveys, such as Eurobarometer,43 finds that only 9% of Danes describe themselves as ‘atheists’, 13% as ‘non-believers/agnostics’, whereas 75,4% describe themselves as ‘believers/religious’.43 Approximately one-third of the latter believe in a ‘personal God’, the rest in ‘a higher power’. In many ways, Danes may figuratively be said to be the people in the world with the highest degree of ‘passive’ membership of the church, which can be activated in case of existential and spiritual needs. More than 76% of Danes are members of the Danish National Evangelical Lutheran Church (the world’s highest degree of membership of any organised church), whereas only 2% go to church on a weekly basis (the world’s lowest degree of religious practice). This ‘membership’ does not merely concern church attendance; it involves cultural, ethnical and existential affiliation, and for many people symbolises the belief that there is ‘more between heaven and earth’ without them retorting to active religion. Thus, the title of a PhD-thesis that investigates the spirituality of young Danes and Swedes in the Øresund region fittingly reads: ‘I’m a believer, but I’ll be damned if I’m religious’.44 This ‘passive membership’ can be activated if a person experiences a loss of control in connection with a crisis, especially illness, either of his own or in the nearest family. Nothing thus seems to move secular people to think about existential, spiritual and religious issues more than crisis and illness, and nowhere are people more confronted with illness, than at the hospital. And dying people, even in secular societies like Denmark, often have unmet ambivalent spiritual needs.26 Because spiritual and/or religious considerations seem tabooed and ambivalent in a secular society like Denmark, and because many Danes have limited language for these considerations there is a need for competent SC. Potentially many Danes will be existentially unprepared, when encountering suffering. This leads us to the question of what SC is.

Based on years of consensus processes and dialogue in Nordic Network for Faith and Health, including research and writing by the authors of the present article, we sought to approach the definitions and understandings through group concept mapping (GCM) methodology.45–47 GCM methodology is a mixed-method approach to generating and structuring ideas on a specific topic. During the GCM process, participants are involved in several steps of the research process and the final results are illustrated in maps where ideas on the specific topic are organised thematically.

Objective

Much uncertainty remains as to what the concept of SC includes. The objective of this article was hence to identify, organise and prioritise experiences with the way SC is conceived and practised by professionals in research and the clinic in a secular Danish context.

Methods

We used a GCM approach to synthesise understandings and experiences regarding SC among members of a ‘SC Research Group’ in Denmark.

Participants

Researchers, students and clinicians connected to the ‘existential and SC research group’ at the Research Unit of General Practice), Institute of Public Health at the University of Southern Denmark (SDU) were invited to participate in the study. Thus, purposive sampling was applied. Participants were to fulfil the following inclusion criteria: (1) Having at least completed a master’s degree AND (2) Having professional clinical experience with SC OR (3) Having professional research experience with SC.

Eighteen persons who met the inclusion criteria were identified and invited either through email or personal contact. All were informed about the study design including participation in at least one of three elements: brainstorming, sorting and rating, and validation of data. Participation was not compensated. All 18 persons agreed to participate. All participants gave information regarding age, gender, profession, employment, years working with SC as a clinician, and years working with SC as a researcher (table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (n=18)

| Age, median (IQR) | 47, 5 (42.3–51.8) |

| Age, range | 27–75 |

| Women, n (%) | 10 (56) |

| Participated in brainstorm, n (%) | 15 (83) |

| Participated in sorting/rating, n (%) | 15 (83) |

| Participated in validation, n (%) | 13 (72) |

| Participated in both sorting/rating and validation, n (%) | 11 (61) |

| Research experience, years, median (IQR) | 9, 5 (2.8–10.8) |

| Research experience, years, range | 1–44 |

| Type of research experience, n (%)* | |

| Literature or bibliographic | 2 (11) |

| Qualitative | 15 (83) |

| Quantitative | 11 (61) |

| Both qualitative and quantitative | 9 (50) |

| Employment, n (%)* | |

| Research assistant | 2 (11) |

| PhD student | 2 (11) |

| Post.doc. | 4 (22) |

| Research fellow | 2 (11) |

| Associate professor | 3 (17) |

| Professor | 1 (6) |

| Physician or MD | 6 (33) |

| Chaplain | 2 (22) |

*Some participants contribute to this statistic more than once, why the sum does not equal 100%.

Patient and public involvement

As this research project centred on professional perspectives on SC, we only included professional users in the study. However, the need for the present study became clear out of the base patient user panel of our research group that we consult ongoingly.

Study design and procedures

To address the aim of the study, GCM45–47 was applied. The following phases were included in the structured GCM process1: preparing for GCM,2 generating the ideas (brainstorming),3 structuring the statements (sorting and rating),4 GCM analysis (data analysis),5 interpreting the map (validation) and6 utilisation (developing a conceptual model).48 These six phases provided a structure for the process (figure 1).

Figure 1.

First cluster rating map with six clusters (uploaded).

In general, GCM involves a type of integrative mixed method participatory approach, combining qualitative and quantitative approaches to data collection and analysis. The process may involve face-to-face group sessions, online participation or both.47 48 In this study, both were applied. Phasesone to four were conducted on-line, whereas phasefive took place during a face-to-face session. Brainstorming was completed using Microsoft Excel, whereas sorting, labelling, rating and generation of cluster rating map was performed using the CS Global Max software system.49

Preparing for GCM

Before initiating the data collection, a focus prompt was formulated and piloted. The final version was: ‘In my professional perspective, SC is characterized by ….’

Generation of ideas (brainstorming)

Through email, participants were instructed to brainstorm with as many brief continuations as possible to the focus prompt using an attached Excel file. They were reminded to keep each sentence/idea short containing only one meaning (g, ‘SC is an important aspect of palliative care’), and it was clarified that the word ‘professional’ related to both clinical and research-based perspectives. Participants forwarded their Excel file and an overall list of ideas was generated. Identical ideas were individually identified by the second and last author and removed after consensus was reached.

Structuring the statements (sorting and rating)

Again, the participants received an e-mail containing information about the sorting and rating tasks as well as a link to online participation using CS Global Max software. The first task was to sort all the ideas generated during the brainstorm into clusters, and to label each cluster. This was an individual task performed according to individual preferences. Next, the participants rated the importance of each idea on a four-point ordinal scale; a score of one being ‘Unimportant’ and a score of four being ‘Very important’.

GCM analysis (data analysis)

Based on phases 2 and 3, a Cluster Rating Map was generated using the CS Global Max software to be presented at the face-to-face validation meeting in phase 5. For further information, see section on data analysis.

Interpreting the map (validating)

At the validation session, the Cluster Rating Map was presented to the participants and they engaged in a group discussion, revising and interpreting the map, for example, the number and content of derived clusters and the labels.

Utilisation (developing a conceptual model)

Finally, the participants created a conceptual model based on the Cluster Rating Map generated using the CS Global Max software (phase 4) and input from the validation session (phase 5). For further information, see section on data analysis.

Data analyses

Participant characteristics

Participant data on age, gender, research experience, employment type and types of involvement in the GCM process were registered. Age and research experience were reported using median and IQR due to lack of normal distribution of the data. Data on gender, profession, employment and project involvement were presented in percentages. Analyses of participant data were performed using Microsoft Excel 365 ProPlus.

Data from GCM

CS Global Max software wasused to perform data analyses based on the ideas derived from the brainstorming. The analyses were conducted in several steps. First, ideas gathered were consolidated; if needed, identical ideas were removed, and ideas revised in order to clarify the meaning. The remaining ideas were then imported into CS Global Max in preparation for phases 3 and 4.

Participant data from phase 3 were to be included in the cluster analysis if more than 75% of the ideas were sorted and if less than five ideas remained unrated. Based on the sorting and rating of these ideas (phase 3), multidimensional scaling analysis and cluster analysis were performed in which related ideas were grouped into clusters.48 During this process, several cluster solutions were generated and the one that matched the data the best (ie, the cluster solution representing sufficient details on the topic) was applied, creating the Cluster Rating Map (phase 4). Within the multidimensional scaling analysis, the stress value is a statistic used to indicate ‘goodness of fit’. A low stress value (<0.39) was used to determine congruence between the raw data and processed data.48 Based on the labels provided by the participants in phase 3, cluster labels were suggested by CS Global Max software. Besides illustrating the labelled clusters in relation to each other, the importance of ideas included in each cluster was also depicted by the number of layers in each cluster, based on median values for importance ratings given for each idea in the cluster.

The Cluster Rating Map was validated at the face-to-face validation meeting (phase 5), revising the number and labels of clusters. The final conceptual model was generated based on this validated Cluster Rating Map, thematic analysis and consensus among participants. Thus, the participants analysed the clusters and the included ideas to determine if the included ideas were placed in a cluster that best matched the meaning of the ideas and discussed to obtain consensus.

Results

All participants were involved in at least one of the three phases. In total, 15 (83%) were involved in the brainstorming phase, 15 (83%) in sortingand rating online only, and finally, 13 (72%) participatedat the validation meeting. Overall, 10 (56%) were involved in all three phases. The number of participants involved in the study is on par with recommendations of core literature on the GCM methodology.46

During the brainstorm phase, participants generated a total of n=327 ideas. Identical ideas were identified and removed before 192 unique ideas were imported into the CS Global Max software for sorting and labelling. In the third phase, all participants sorted 100% of the ideasinto between 2 and 21 clusters, and four participants (22%) left between one and fiveideas unrated (n=10). As the proportions of unsorted and unrated statements for each participant were below the predefined criteria, the 192 ideas were all included in the analyses (phase 4). Cluster solutions from 10 to 6 clusters were applied; the one with six clusters matched the data the best and was used to create the first Cluster Rating Map (figure 1). These initial six clusters contained between 23 and 49 ideas and were preliminarily labelled by CS Global Max, based on a variety of labels suggested by individual participants during phase 3. The clusters represented ideas with varying importance, which is depicted by the height of each cluster. The most important ideas were placed in the highest clusters. A total of n=44 ideas (23%) with high importance (median=4) were identified across the six clusters. The multidimensional scaling analysis involved 24 iterations and revealed a low stress value of 0.3023.

Discussions at the face-to-face validation meeting (phase 5) resulted in revision of the Cluster Rating Map. First, the participants decided to keep the same number of clusters but renamed four clusters. In the thematic analysis, the authors agreed on the cluster location of 96% (n=185) of the ideas. Thus, seven ideas were moved between clusters. The final six clusters are presented in table 2. The 192 ideas sorted into the final six clusters are presented in online supplemental appendix 1 along with median importance ratings for each idea. There are no additional data available.

Table 2.

Description of the final six group concept mapping clusters of understanding of spiritual care

| Cluster | Summary-content |

| 1. Spiritual care as a part ofhealthcare No of ideas: 24 |

SC is agrowing type of healthcare which goes beyond biophysical and social needs and relates to patients’ and relatives’ existential and spiritual needs. Health professionals (eg, nurses, chaplains, psychologists and medical doctors) often engage in interdisciplinary work with patients and relatives through dialogue about spiritual issues. SC is a particularly important aspect of rehabilitation, palliative care, and general practice. |

| 2. Perceived significance No of ideas: 27 |

SC is an underprioritised aspect of healthcare and not perceived as relevant for all patients. It is also perceived as difficult to approach—especially in a secular country (eg, Denmark). It is a sphere of healthcare which, particularly in a multicultural and pluralistic context, calls for more attention: for example, in the fields of education, supervision and research. It is an area with the potential to relieve anxiety and suffering, and thereby support a holistic approach to healthcare. |

| 3. The role of spirituality No of ideas: 23 |

Spirituality is an essential part of spiritual care. Spirituality may comprise both patients’ existential, spiritual and religious concerns into an existential frame of self-concept. It emphasizes the connection/relationship between an individual self (body, mind and spirit/soul) and that individual’s self-transcending experiences, meaning and not rarely also sacred entities like oracles, prophets, spirits and/or deities (ie, God). It is always embedded and understoodwithin and with regard to the prevailing culture. |

| 4. Help and support No of ideas: 34 |

SC involves supporting and helping patients when they face existential/spiritual/religious crises in healthcare. This involves taking the time to explore the patients’ spiritual history and not just their medical history; supporting both patients and relatives through active listening, and using dialogue to explore their thoughts, feelings and outlook on life; and assisting patients in finding meaning and purpose in the things they value, and, if possible, gaining inner peace and well-being. |

| 5. Quality in attitude and action No of ideas: 35 |

SC is attentive and respectful towards patients’ values and beliefs. Healthcare professionals achieve this by acknowledging and supporting patients’ personal dignity through empathic listening and by offering comfort, compassion, love and advice. |

| 6. Relationship No of ideas: 49 |

SC requiresrelationships between healthcare professionals and patients that are characterised by empathy and trustworthiness. Healthcare professionals are aware of their responsibility for this relationship with the patient. The professional encounter should be grounded in a committed and compassionate relationship. SC takes place when healthcare professionals are fully present and engaged in exploring the patients’ resources, allowing periods of silence in conversation, or holding the hands of a patient in need of a hand to hold. |

SC, spiritual care.

bmjopen-2020-042142supp001.pdf (68.4KB, pdf)

The first cluster named SC as a part of healthcare contained 24 ideas, for example, ‘Attending one of the four aspects of health along with physical, psychological and social’ suggesting that SC should be understood and practised as a standard aspect of healthcare. The second cluster named perceived significance contained 27 ideas capturing a broad spectrum of notions related to SC, for example, ‘recognising that SC can play a fundamental role in the healing process’ but also that SC is not easy to grasp and practice in secular culture and that it, in order to be qualified, needs to be an integrated aspect of basic and continued learning in healthcare. The third cluster named The role of spirituality included 23 ideas about the nature and role of spirituality, for example, ‘being an essential part of being human’, recognising that it may variously comprise patients’ existential, religious and spiritual concerns. The fourth cluster named Help and support comprised 34 ideas that involved helping patients or a family to cope with existential, religious and/or spiritual issues such as hope and fear, and that SC involved ‘non-verbal relational communication’ and that it requires ‘accepting any belief system my patients/their relatives/their caregivers may hold.’ The fifth cluster named Quality in attitude and action contained 35 ideas such as ‘being ‘out in the open’ with the patient even if I have no treatment or ailment for their disease’ and that SC should be attentive and respectful towards patients’ values and beliefs, something that basic inquiry into the patients background (including believes) may assist. The sixth cluster named Relationship included 49 ideas that all emphasised the importance and nature of relations in healthcare, for example, ‘human equality between health professionals and patients’ underlining the importance of being aware of one’s own weakness and fundamental values.

Based on the discussion and decisions at the validation meeting, a final conceptual model revealing what characterises SC was developed (figure 2). The conceptual model encompassed six clusters reflecting vital aspects of SC. They clustered in three over-all themes: (1) SC as an integral but underdeveloped part of healthcare (involving two concepts), (2) delivering SC (involving three concepts) and (3) the role of spirituality.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model (uploaded). Three themes are presented. Green: spiritual care as an integral but underdeveloped part of healthcare. Blue: delivering spiritual care. Red: the role of spirituality.

Discussion

Although substantial research documents the integral role of SC for high-quality patient-centred care there is much uncertainty as to what SC actually is and how it is best practised. Accordingly, in this study a GCM approach was used to synthesise experiences among researchers, students and clinicians involved in an ‘Existential and Spiritual Care Research Group’ in Denmark. As mentioned in the Conceptual Model, three overall themes emerged: (1) SC as an integral but underdeveloped part of healthcare, (2) Delivering SC and (3) The role of spirituality.

SC as an integral but underdeveloped part of healthcare (green colour theme)

SC was found to be a part of healthcare (cluster 1) and has continued to grow as an important theme, partly due to the enhanced focus on the interactions of biological, psychological and social issues in healthcare. We recognised that nurses, medical doctors, psychologists and chaplains already engage in existential and spiritual issues with their patients and that it is particularly true for palliative care, general practice and rehabilitation.

This finding resonates well with WHO that identified spiritual problems among the dying as part of ‘total pain’ consisting of physical, psychological, social but also spiritual pain. According to WHO’s definition of palliative care, (2002) it is care that consists of treatment and care directed towards ‘total pain’, that is, care of all four aspects of pain, including patients’ ‘pains and other problems of both physical, psychological, psychosocial and existential/spiritual type’.50–52 WHO emphasises that existential and spiritual beliefs have decisive impact on humans in crisis, and that providing existential and SC among patients with life-threatening, terminal conditions is a vital quality-of-life enhancing factor.53 Likewise, The World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA) Europe has presented a Wonca Tree of Core Competencies and Characteristics of Family Medicine highlighting the holistic modelling that focuses on ‘physical, psychological, social, cultural and existential’ aspects of care.54 Documents highlight the degree to which SC is part of patient-centred care.55 56 Like the WHO and WONCA, the Danish Quality Model underlines that the care and treatment of patients include incorporating existential and SC,57 and there is an increased focus on existential and spiritual needs included in the National Board of Health’s ‘Professional guidelines for palliative efforts’58 and ‘Recommendations for palliative efforts’.59 Despite these affirmations on all four aspects of health, of suffering and of pain, few documents speak of the existential and spiritual dimension of rehabilitation. Apart from patients’ needs for both physical,60 psychological61–64 and social rehabilitation,65 patients likewise may be in need of existential and/or spiritual rehabilitation. We thus permit ourselves to coin the concept of existential and spiritual rehabilitation to reflect the need for coping with the spiritual challenges following a cancer diagnosis involving meaning, generativity, hope, and, for some, faith in a higher being and in life after death. Such existential and spiritual rehabilitation may be of great importance, whether a person recovers from a disease, has just been diagnosed or is incurable.

Despite these affirmations, there was agreement (confirmed in the GCM data) that SC is the most underdeveloped and difficult aspect of patient-centred, holistic healthcare (Cluster 2). Danish as well as international studies indicate that both senior patients and healthcare professionals (HCPs) experience existential and spiritual needs as very difficult to address16 25 66–73 and that these needs therefore remain largely unmet.74 This has consequences not only for the patients and HCPs, but also at the economic level through prolonged stays in hospitals (in particular ICUs) and hospices.38 One of today’s largest societal health challenges is thus how to meet the existential needs of patients, in particular those challenged by life-threatening disease. The European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) has appointed a Task Force for SC. Here SC is seen as care directed towards the spiritual needs which people may experience in case of severe illness with similar initiatives in other realms of healthcare.51

There may be many reasons for this deficiency in modern healthcare: SC is hard to define, it involves personal values that are difficult to base on empirical evidence, and to put into general guidelines for healthcare practice. In Denmark, where spiritual values are highly individualised and private, this mightbe difficult to an even greater extent. SC thus involves strategic leadership and proactive attention if it is to be implemented in a qualified and non-arbitrary manner.75

Delivering SC (blue colour theme)

SC was found to provide help and support patients (cluster 4) as they cope with existential, religious and/or spiritual issues. This can be done among others by taking the patients’ spiritual history alongside their medical history. Numerous tools have been developed for spiritual history taking, among which the FICA tool is the best known.76 But it also involves a particular type of attitude, active listening fostering dialogue about things that matter deeply, supporting their reflections on values in life. Such personal attitudes and qualities are central to SC (cluster 5) whereforethe delivery of SC can never be considered a task external to the person providing SC. German hospice chaplain Thomas Harding thus speaks of Wahrnehmungas a fundamental aspect of SC.77 The word Wahrnehmung is not directly translatable but literally means to take true, and this could well be said to be a core of SC: taking in and caring for the truth or essence of the other person. Although SC does not require religious studies with detailed insight into world religious beliefs, SC is attentive to the beliefs and values of patients supporting their dignity by means of empathic listening, and by offering comfort, compassion, love and advice.

Such qualities can only be achieved by means of what may be another innermost requirement of SC: Significant, enriching and trust-inspiring relationships between HCPs, patients and relatives (cluster 6). In fact, research has identified spirituality as relational in its core, as the individual human being relates inwards, outwards and upwards—to self, to others and (for some) to the divine/transcendent,78 a tripartite movement that has been identified in patterns of mindfulness, meditation and prayer as well.79 80 Such ‘healing’ relationships are promoted by the HCP’s empathic, non-judgemental and appreciative attitude towards the patient, that make the patient feel seen, heard and understood in his/her suffering, but furthermore by an awareness of mutuality in the relationship: that both patient and HCP is depending on one another’s willingness to invest him/herself in the relationship and to share in a common human vulnerability. Research indicate that HCPs’ability to relate to patients in the fullness of their humanity, rather than as to objects (ie, as I-Thou, instead of I-It)81 might be among the most important spiritual experiences of all.82 Recognising the potential of experiences of mutualityin the relationship between HCPs and patients is not to deny that the HCP–patient relationship is inherently asymmetrical.83 It is pointing to aninter human, relational dimension that enables the HCP to use his/her biomedical knowledge and technical competence as appropriately and meaningful as possible in a way that resonates with both the HCPs’ and the patients’ spirituality, regardless their potential differences. This, in turn, brings us to the third overall theme of the Conceptual Model of SC which impacts the understanding of the former two overall themes: the role of spirituality.

The role of spirituality (red colour theme)

Spirituality was found to be an integral part of human life, comprising various patients’ existential, spiritual and religious concerns (cluster 3). Spirituality is the connection between the different parts of the human being (body, mind and soul). This resonates with international incentives to define spirituality. EAPC, thus, defines spirituality as ‘the dynamic dimension of human life regarding the way people (individuals and society) experience, express and/or seek meaning, purpose and transcendence, and the way they connect to the moment, to themselves, to others, to nature, to the important and/or the holy aspects’.84 This definition emerged from a consensus process and develops further a similar consensus-based definition in an American health professional context.21 Important to note is, that care is not only directed towards patients’ individual existential perspectives or considerations, but towards exactly ‘the dynamic dimension of human life’, a dimension which other researchers summarise as a person’s inner vitality and/or energy always at play as the foundation of what can bring us through a severe crisis.85

In a mixed-method study,86 514 randomly selected adult Danes were asked which associations among 115 possible ones they related to the concept of spirituality. The respondents could tick off as many boxes as they would. Factor analyses indicated six clear nodes of understandings: (1) Well-being, (2) New Age ideology, (3) A part of religious life, (4) A weak striving opposed to religiosity, (5) Inspiration in human life. A sixth association expressed a negative attitude to spirituality understood and (6) Selfishness. Also, our present study shows how spirituality covers a wide field where most of them may overlap, but also contain differences and tensions, which may in turn help explain, why SC is not easy to practise and integrate into healthcare. In many ways, attending to patients’ needs for SC and spiritual rehabilitation calls for significant different training of HCPs than providing physical, psychological and social rehabilitation.

Ironically, because spirituality constitutes a fundamental core aspect of each human being, it calls for SC to be a well-integrated aspect of healthcare (cluster 1), but it also makes it difficult to practise SC, because each individual has to be treated as a unique being with a unique kind of spirituality and with unique values associated to that spirituality. The fundamentality and universality of spirituality bear the paradox that it is fundamental to healthcare and at the same time difficult to provide.

Strengths and limitations

The use of GCM methodology in the present study is considered a strength Hence, GCM implies a structured approach mixing quantitative and qualitative methodology by combining qualitative data generation (ie, ideas on a specific topic) and statistical analyses to support the structuring of data. Further, participants are involved throughout the entire research process (data generation, analyses, validationof results, discussion). This study was conducted with the purposeof synthesising understandings and experiences regarding SC among members of a specific ‘Spiritual Care Research Group’. Thus, the sample size was relativelysmall (n=18). However, according to GCM literature, tenpersons is generally considered to be minimum in order to perform a valid statistical analysis.46

Conclusion

The present GCM investigation has identified six clusters of understandings of SC that could be organised in three overall themes: (1) SC as an integral but underdeveloped part of healthcare, (2) Delivering SC and (3) The role of spirituality. Because spirituality in the common understanding is a fundamental aspect of each individual human being, SC should be an integral aspect of healthcare. Paradoxically, precisely because of this fundamentality, it is nevertheless also challenging to practise SC, as it involves the individual spirituality of the HCP, tuning in on the individual spirituality of the patient (or relative) and engaging care for needs for which there are no quick fixes but that require personal attunement and investment. The benefits of engaging in SC nevertheless seem plentiful, both for HCPs, patients and relatives.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @nchvidt, @AKKorup, @Katjas75

Contributors: One of the particularities of the GCM methodology is that it allows for a large degree of active contribution of several collaborators to analysis and writing of a manuscript which is the case also in this article. NCH: contributed with overall planning of research project together with EEEW and KTN, contributed to all phases of data generation, contributed to most phases of analysis, wrote the first draft of the paper and contributed to all subsequent drafts of the paper. KTN: contributed with overall planning of research project together with EEEW and NCH, contributed to all phases of data generation, contributed to all phases of analysis, contributed to all drafts of the paper. AKK: contributed to most phases of analysis, in particular demographics and modelling of Conceptual Model, and contributed to the writing of all drafts of the paper. CP: contributed to most phases of analysis and to the writing of all drafts of the paper. DGH: contributed to most phases of analysis and to the writing of all drafts of the paper. DTV: contributed to most phases of analysis and to the writing of all drafts of the paper. EAH: contributed to most phases of analysis and to the writing of all drafts of the paper. ERH: contributed to most phases of analysis and to the writing of all drafts of the paper. EF: contributed to most phases of analysis and to the writing of all drafts of the paper. FL: contributed to most phases of analysis and to the writing of all drafts of the papper. HBB: contributed to most phases of analysis and to the writing of all drafts of the paper. JAW: contributed to most phases of analysis and to the writing of all drafts of the paper. KFT: contributed to most phases of analysis and to the writing of all drafts of the paper. KS: contributed to most phases of analysis and to the writing of all drafts of the paper. LM: contributed to most phases of analysis and to the writing of all drafts of the paper. RDN: contributed to most phases of analysis and to the writing of all drafts of the paper. SS-F: contributed to most phases of analysis and to the writing of all drafts of the paper. TKS: contributed to most phases of analysis and to the writing of all drafts of the paper. VØS: contributed to most phases of analysis and to the writing of all drafts of the paper. JS: contributed to most phases of analysis and to the writing of all drafts of the paper. EEEW: contributed with overall planning of research project together with NCH and KTN, contributed to all phases of data generation, contributed to all phases of analysis, contributed to all drafts of the paper.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: According to Danish legislation, ethical approval as well as approval from the Danish Data Protection Agency was not required, as no subjects were exposed to medical interventions and/or devices and no sensitive data was collected. However, we have obtained approval (Approval Number 10.367, 'Existential Patient Needs') of SDU RIO, the agency that handles all approvals on behalf of The Danish Data Protection Agency at our University of Southern Denmark, also with regard to GDPR.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. Danish interpretation of GDPR does not allow for the sharing of the data of this article in an open access format. However, researchers can contact the last author if interested in the data.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Koenig H, Koenig H, King D, et al. Handbook of religion and health, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murgia C, Notarnicola I, Rocco G, et al. Spirituality in nursing: a concept analysis. Nurs Ethics 2020;27:0969733020909534:1340–3. 10.1177/0969733020909534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nolan S, Saltmarsh P, Leget C. Spiritual care in palliative care: working towards an EAPC Task force. EJPC 2011;18:86–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torskenæs KB, Baldacchino DR, Kalfoss M, et al. Nurses' and caregivers' definition of spirituality from the Christian perspective: a comparative study between Malta and Norway. J Nurs Manag 2015;23:39–53. 10.1111/jonm.12080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pembroke NF. Appropriate spiritual care by physicians: a theological perspective. J Relig Health 2008;47:549–59. 10.1007/s10943-008-9183-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puchalski CM. Spiritual Care: Compassion and service to others : Puchalski CM, A time for listening and caring: spirituality and the care of the chronically ill and dying. Oxford University Press, 2006: 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roser T, Care S. Ethische, organisationale und spirituelle Aspekte der Krankenhausseelsorge. Ein praktisch-theologischer Zugang : Borasio GD, Augustyn B, Bausewein C, et al., Mit einem Geleitwort von Eberhard Schockenhoff. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinclair S, Mysak M, Hagen NA. What are the core elements of oncology spiritual care programs? Palliat Support Care 2009;7:415–22. 10.1017/S1478951509990423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Speck P. The evidence base for spiritual care. Nurs Manage 2005;12:28–31. 10.7748/nm2005.10.12.6.28.c2038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White G. An inquiry into the concepts of spirituality and spiritual care. Int J Palliat Nurs 2000;6:479–84. 10.12968/ijpn.2000.6.10.9047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards A, Pang N, Shiu V, et al. The understanding of spirituality and the potential role of spiritual care in end-of-life and palliative care: a meta-study of qualitative research. Palliat Med 2010;24:753–70. 10.1177/0269216310375860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Health Service Religious and Spiritual Care of Patients - Best Practice Guidelines and Faith Information Resource. NHS Foundation Trust, 2010November(CM11638). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greasley P, Chiu LF, Gartland M. The concept of spiritual care in mental health nursing. J Adv Nurs 2001;33:629–37. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01695.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross L, McSherry W, Giske T, et al. Nursing and midwifery students' perceptions of spirituality, spiritual care, and spiritual care competency: a prospective, longitudinal, correlational European study. Nurse Educ Today 2018;67:64–71. 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McSherry W, MSherry R, Watson R. Care in nursing: principles values and skills. Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balboni TA, Paulk ME, Balboni MJ, et al. Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: associations with medical care and quality of life near death. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:445–52. 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Nawawi NM, Balboni MJ, Balboni TA. Palliative care and spiritual care: the crucial role of spiritual care in the care of patients with advanced illness. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2012;6:269–74. 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3283530d13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strang S, Strang P. Spiritual thoughts, coping and 'sense of coherence' in brain tumour patients and their spouses. Palliat Med 2001;15:127–34. 10.1191/026921601670322085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, et al. Exploring the spiritual needs of people dying of lung cancer or heart failure: a prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers. Palliat Med 2004;18:39–45. 10.1191/0269216304pm837oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen SR, Mount BM, Tomas JJ, et al. Existential well-being is an important determinant of quality of life. Evidence from the McGill quality of life questionnaire. Cancer 1996;77:576–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the consensus conference. J Palliat Med 2009;12:885–904. 10.1089/jpm.2009.0142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Efficace F, Marrone R. Spiritual issues and quality of life assessment in cancer care. Death Stud 2002;26:743–56. 10.1080/07481180290106526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vallurupalli M, Lauderdale K, Balboni MJ, et al. The role of spirituality and religious coping in the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative radiation therapy. J Support Oncol 2012;10:81–7. 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarakeshwar N, Vanderwerker LC, Paulk E, et al. Religious coping is associated with the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med 2006;9:646–57. 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams JA, Meltzer D, Arora V, et al. Attention to inpatients' religious and spiritual concerns: predictors and association with patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:1265–71. 10.1007/s11606-011-1781-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moestrup L, Hvidt NC. Where is God in my dying? A qualitative investigation of faith reflections among hospice patients in a secularized Society. Death Stud 2016;40:618–29. 10.1080/07481187.2016.1200160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caldeira S, Carvalho EC, Vieira M. Spiritual distress-proposing a new definition and defining characteristics. Int J Nurs Knowl 2013;24:77–84. 10.1111/j.2047-3095.2013.01234.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.la Cour P, Hvidt NC. Research on meaning-making and health in secular society: secular, spiritual and religious existential orientations. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:1292–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall DE, Koenig HG, Meador KG. Conceptualizing "Religion". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 2004;47:386–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones JM, Cohen SR, Zimmermann C, et al. Quality of life and symptom burden in cancer patients admitted to an acute palliative care unit. J Palliat Care 2010;26:94–102. 10.1177/082585971002600205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thuné-Boyle IC, Stygall JA, Keshtgar MR, et al. Do religious/spiritual coping strategies affect illness adjustment in patients with cancer? A systematic review of the literature. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:151–64. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.la Cour P. Existential and religious issues when admitted to hospital in a secular society: patterns of change. Ment Health Relig Cult 2008;11:769–82. 10.1080/13674670802024107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fleischer E, Jessen G. Eksistentielle samtaler med ældre - vanskelige samtaler og tunge emner. Suicidologi 2008;2:16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heap K. Samtalen I Eldreomsorgen. Oslo: Kommuneforlaget, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 35.González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Castellanos Miguel Ángel, et al. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. 87 Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 2020: 172–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heidari M, Yoosefee S, Heidari A. COVID-19 pandemic and the necessity of spiritual care. Iran J Psychiatry 2020;15:262–3. 10.18502/ijps.v15i3.3823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrell BR, Handzo G, Picchi T, et al. The Urgency of Spiritual Care: COVID-19 and the Critical Need for Whole-Person Palliation. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;60:e7–11. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.06.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balboni T, Balboni M, Paulk ME, et al. Support of cancer patients' spiritual needs and associations with medical care costs at the end of life. Cancer 2011;117:5383–91. 10.1002/cncr.26221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zuckerman P. Society without God: what the least religious nations can tell us about contentment. New York: New York University Press, 2008: ix, 227. [Google Scholar]

- 40.EEØ J, Mørk LB. Vi tier om religion og psykisk sygdom : EEØ J, Berlingske Tidende. København: Berlingske Medier, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor C. Reformation and the secular age. Journal of the Council for Research on Religion 2020;1:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gundelach P. Små og Store Forandringer. Danskernes Værdier siden 1981. [Small and Big Changes. The Values of the Danes since 1981]. København: Hans Reitzels Forlag, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 43.European Commission,, ZACAT, GESIS Data Service . Eurobarometer 90.4 (December 2018): attitudes of Europeans towards biodiversity, public perception of illicit tobacco trade, awareness and perceptions of EU customs, and perceptions of Antisemitism 2018. Available: https://zacat.gesis.org/webview/index.jsp?headers=http%3A%2F%2F193.175.238.79%3A80%2Fobj%2FfVariable%2FZA7556_V204&v=2&stubs=http%3A%2F%2F193.175.238.79%3A80%2Fobj%2FfVariable%2FZA7556_V11&weights=http%3A%2F%2F193.175.238.79%3A80%2Fobj%2FfVariable%2FZA7556_V440&V204slice=1&study=http%3A%2F%2F193.175.238.79%3A80%2Fobj%2FfStudy%2FZA7556&charttype=null&tabcontenttype=row&V11slice=1&V204subset=1+-+10%2C11%2C12+-+13%2C14&mode=table&top=yes

- 44.Rosen I. I'm a believer - but I'll be damned if I'm religious. Belief and religion in the Greater Copenhagen Area - a focus group study. Lunds Universitet, 2009: 196 s. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trochim WMK. An introduction to concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Eval Program Plann 1989;12:1–16. 10.1016/0149-7189(89)90016-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kane M, Trochim WMK. Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trochim W, Kane M. Concept mapping: an introduction to structured conceptualization in health care. Int J Qual Health Care 2005;17:187–91. 10.1093/intqhc/mzi038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Concept Mapping for Planning and Evaluation Thousand oaks, California. Sage Publications, 2007. https://methods.sagepub.com/book/concept-mapping-for-planning-and-evaluation [Google Scholar]

- 49.Concept Systems I Cs global max 2005.

- 50.WHO Definition of palliative care. Available: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- 51.Best M, Leget C, Goodhead A, et al. An EAPC white paper on multi-disciplinary education for spiritual care in palliative care. BMC Palliat Care 2020;19:9. 10.1186/s12904-019-0508-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.World Health Organization Who definition of palliative care. Available: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- 53.Group W. Development of the WHOQOL: rationale and current status. Int J Ment Health 1994;23:24–56. 10.1080/00207411.1994.11449286 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allen J, Gay B, Crebolder H, et al. The European definition of general practice / family medicine (short version). European Academy of teachers in general practice (network within WONCA Europe, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vincensi BB. Interconnections: spirituality, spiritual care, and patient-centered care. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2019;6:104–10. 10.4103/apjon.apjon_48_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Puchalski C, McSherry W, Ross L. The spiritual history: an essential element of patient-centred care. spiritual assessment in healthcare practice, 2010: 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nielsen V, Christensen JG, Kvalitetsmodel DD. 2. version, 2. udgave AF akkrediteringsstandarder for sygehuse: Institut for Kvalitet OG Akkreditering I Sundhedsvæsenet, Juni 2013. Available: https://www.ikas.dk/FTP/PDF/D12-6522.pdf

- 58. Sundhedsstyrelsen.Kf S, Faglige retningslinier for den palliative indsats: omsorg for alvorligt syge OG døende. København: Sundhedsstyrelsen, 1999: 116 sider.p. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sundhedsstyrelsen. Anbefalinger for den palliative indsats. København: Sundhedsstyrelsen, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Salakari MRJ, Surakka T, Nurminen R, et al. Effects of rehabilitation among patients with advances cancer: a systematic review. Acta Oncol 2015;54:618–28. 10.3109/0284186X.2014.996661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Holm LV, Hansen DG, Johansen C, et al. Participation in cancer rehabilitation and unmet needs: a population-based cohort study. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:2913–24. 10.1007/s00520-012-1420-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fulton C. Patients with metastatic breast cancer: their physical and psychological rehabilitation needs. Int J Rehabil Res 1999;22:291–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ronson A, Body J-J. Psychosocial rehabilitation of cancer patients after curative therapy. Support Care Cancer 2002;10:281–91. 10.1007/s005200100309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Body JJ, Lossignol D, Ronson A. The concept of rehabilitation of cancer patients. Curr Opin Oncol 1997;9:332–40. 10.1097/00001622-199709040-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peikert ML, Inhestern L, Bergelt C. Psychosocial interventions for rehabilitation and reintegration into daily life of pediatric cancer survivors and their families: a systematic review. PLoS One 2018;13:e0196151. 10.1371/journal.pone.0196151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Balboni TA, Balboni M, Enzinger AC, et al. Provision of spiritual support to patients with advanced cancer by religious communities and associations with medical care at the end of life. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1109–17. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bruce A, Boston P. Relieving existential suffering through palliative sedation: discussion of an uneasy practice. J Adv Nurs 2011;67:2732–40. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05711.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lundmark M. Attitudes to spiritual care among nursing staff in a Swedish oncology clinic. J Clin Nurs 2006;15:863–74. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01189.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Buxton F. Spiritual distress and integrity in palliative and non-palliative patients. Br J Nurs 2007;16:920–4. 10.12968/bjon.2007.16.15.24515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Assing Hvidt E, Søndergaard J, Ammentorp J, et al. The existential dimension in general practice: identifying understandings and experiences of general practitioners in Denmark. Scand J Prim Health Care 2016;34:385–93. 10.1080/02813432.2016.1249064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Assing Hvidt E, Søndergaard J, Hansen DG, et al. 'We are the barriers': Danish general practitioners' interpretations of why the existential and spiritual dimensions are neglected in patient care. Comunication and Medicine 2016;14:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mako C, Galek K, Poppito SR. Spiritual pain among patients with advanced cancer in palliative care. J Palliat Med 2006;9:1106–13. 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Delgado-Guay MO, Hui D, Parsons HA, et al. Spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain in advanced cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;41:986–94. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pearce MJ, Coan AD, Herndon JE, et al. Unmet spiritual care needs impact emotional and spiritual well-being in advanced cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:2269–76. 10.1007/s00520-011-1335-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Paal P, Neenan K, Muldowney Y, et al. Spiritual leadership as an emergent solution to transform the healthcare workplace. J Nurs Manag 2018;26:335–7. 10.1111/jonm.12637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Borneman T, Ferrell B, Puchalski CM. Evaluation of the FICA tool for spiritual assessment. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40:163–73. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hagen T, Riedner C, Anamnese S, Frick E, roser T, Spiritualität und Medizin Gemeinsame Sorge für den Kranken Menschen. Münchner Reihe Palliative Care MRPC. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2009: 229–34. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Swinton J, Bain V, Ingram S, et al. Moving inwards, moving outwards, moving upwards: the role of spirituality during the early stages of breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Care 2011;20:640–52. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01260.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ladd KL, Spilka B, Inward SB. Inward, outward, and upward: cognitive aspects of prayer. J Sci Study Relig 2002;41:475–84. 10.1111/1468-5906.00131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ladd KL, Ladd ML, Harner J, et al. Inward, outward, upward prayer and big five personality traits. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 2007;29:151–76. 10.1163/008467207X188711 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Buber M.I And thou. London/New York: Bloomsbury; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lomax JW, Kripal JJ, Pargament KI. Perspectives on "sacred moments" in psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 2011;168:12–18. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Scott JG, Scott RG, Miller WL, et al. Healing relationships and the existential philosophy of Martin Buber. Philos Ethics Humanit Med 2009;4:11. 10.1186/1747-5341-4-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vd G, Leget C, Wulp M. Spiritual care in palliative care: working towards an EAPC Task force. EJPC 2011;18:86–9. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Torskenæs KB. The spiritual dimension in nursing: a mixed method study on patients and health professionals. Oslo: Menighetsfacultetet, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 86.la Cour P, Assing Hvidt E, Hvidt NC. What is the meaning of the word "Spirituality"? A mixed methods investigation of a concept calling for meaning [Ref. Research Unit of General Practice, SDU: Odense, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-042142supp001.pdf (68.4KB, pdf)