Abstract

The purpose of this research is to demonstrate through a techno-economic assessment that aniline can be industrially produced using a profitable and inherently safer process than the ones currently employed. The aniline production process was designed using process simulation software. From this, the mass and energy balances were determined, the equipment sizing was performed and the net present value (NPV) was calculated to be USD 93.5 million. Additionally, a heat integration analysis was carried out in order to improve process profitability, obtaining a new NPV of USD 97.5 million. The economic sensitivity analysis showed that the process could withstand fixed capital investment changes of up to +89%, weighted average cost of capital changes between 16–24% and a decrease in cyclohexylamine demand of up to 44%. The conceptual design is still profitable when aniline price is varied in a range of 1224–1840 $/t and phenol cost in a range of 815–1178 $/t.

Keywords: Chemical engineering, Industrial chemistry, Safety engineering, Process modeling, Computer-aided engineering, Phenol to aniline, Process design, Process safety, Energy analysis, Economic evaluation

Chemical engineering; Industrial Chemistry; Safety engineering; Process Modeling; Computer-Aided Engineering; Phenol to aniline; process design; process safety; energy analysis; economic evaluation

1. Introduction

Aniline is a highly versatile chemical used as a starting raw material to synthesize textile dyes such as indigo and induline, as well as several pharmaceutical drugs such as acetaminophen, sulfadiazine and sulfapyridine (Lamture, 2018). However, its most important use is found in the synthesis of methylene diphenyl diisocyanate (MDI), which in turn is the precursor of polyurethane foams used as insulation materials in construction and automobile industries. Because of these important applications, the aniline market was estimated to be over USD 11.5 billion in 2016 and its demand will likely grow with an annual rate of 6.5% (Pulidindi and Chakraborty, 2017), a rate that would require increasing aniline supply through new manufacturing facilities or revamping current plants.

Nevertheless, increasing the aniline supply represents a potential risk since the synthesis route currently used by 85% (Wang et al., 2019) of the aniline production companies worldwide (nitration of benzene) is highly hazardous, as it involves the use of strong acids in high concentrations, such as sulfuric acid and nitric acid, and the production of unstable and explosive byproducts such as dinitrophenol, picric acid, dinitrobenzene and nitrobenzene (Badeen et al., 2011; Cuypers et al., 2018; Kletz, 2009; Trebilcock and Dharmavaram, 2013). These conditions have caused multiple fatal accidents throughout history. The most prominent ones occurred in USA (1960) and China (2005), where a total of 22 people died and 368 were seriously injured (Lodal, 2004; Schiermeier, 2005).

Given the aforementioned problems, the aim of this work is to design and evaluate the profitability of an aniline production process via amination of phenol, a process that does not require highly concentrated strong acids and releases water as the main byproduct (Cuypers et al., 2018), which could significantly reduce risks and potential industrial accidents. The chosen synthesis route is an example of inherently safer design as it complies with the principle of substitution (Kletz, 2009), which recommends replacing hazardous substances with others that do not represent as much potential risk; thus eliminating the source of hazard instead of trying to control it by incorporating a greater number of safety layers into the process. As a result, the aniline supply could be increased without compromising the health and life of people who work at or near the facility.

At present, the Halcon synthesis route is a profitable aniline production process via the amination of phenol. However, the limitations of this route are the following: (i) high temperatures (425 °C) and pressures (200 bar) are required to carry out the reaction (Kent, 2007), (ii) the catalyst is quickly deactivated and (iii) a large excess of ammonia (ammonia:phenol ratio of 20:1) is required to inhibit byproduct formation (Cuypers et al., 2018), a feature that increases the recycling and compression costs, as well as total capital investment.

Given that the nitration of benzene and the Halcon synthesis route – two of the most commonly used aniline production processes – require severe operating conditions, and that the design of a process employing a safer reaction mechanism remains unexplored, we report a novel and profitable aniline manufacturing process via the amination of phenol using an alternative preexisting synthesis route.

The present work is organized as follows. In Section 2, the aniline synthesis route with the greatest potential for economic viability and inherent safety is selected based on a multi-criteria decision analysis. Additionally, reaction mechanism, reactor selection and process modeling is explained. In Section 3, methodology for equipment selection and sizing, environmental impact assessment, economic evaluation, heat integration and sensitivity economic analysis is described. Sections 4.1–4.4 show process design, environmental impact and NPV results and analysis. Sections 4.5–4.6 explain heat integration analysis. Section 4.7 details the NPV sensitivity analysis. Finally, conclusions are stated in Section 5.

2. Theory

2.1. Synthesis route selection

A multi-criteria decision analysis was carried out in order to select the synthesis route with the greatest potential for economic viability and inherent safety. The following criteria were taken into consideration: rate law availability as described for heterogeneous catalytic systems, reaction temperature, reaction pressure, selectivity, measured yield, phenol phase and ammonia:phenol molar ratio. The weighting factors were calculated according to the analytical hierarchical process (Odu, 2019; Partovi, 2007), a method widely used in industry to systematize decision making and decrease subjectivity when a large number of variables must be evaluated.

The decisive factor for the synthesis route selection is the availability of the kinetic expression since it allows to accurately size the reactor and, therefore, the separation units, which must be modeled according to the reactor's outlet composition. The second most important criteria are the reaction temperature and pressure. Processing under less severe conditions, or following the so-called attenuation principle (Kletz, 2009), increases the inherent safety of a chemical process and is the all-time trend of process design in chemical engineering. Yield and selectivity are the third most important criteria because these values help ensure process profitability. Finally, phenol phase and ammonia excess are the least important criteria because vaporized phenol can be handled at low pressures and ammonia is a relatively inexpensive raw material, so these would not impact process safety or economics significantly. The multi-criteria decision analysis is shown in Table 1 considering that the score ranges from 1 (least beneficial) to 5 (most beneficial).

Table 1.

Multi-criteria decision analysis of the selected aniline synthesis routes.

| Weighting factor | Criteria | Process |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halcon | (Ono and Ishida, 1981) | (Katada et al., 1997) | (Cuypers et al., 2018) | ||

| 33.42% | Rate law availability | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| 18.90% | Temperature | 1 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| 18.90% | Pressure | 1 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| 10.12% | Yield | 5 | 3 | 1 | 5 |

| 10.12% | Selectivity | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| 5.44% | Phenol phase | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 3.10% | Ammonia excess | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| 100.0% | Total | 1.74 | 4.16 | 2.63 | 3.28 |

The aniline synthesis route presented by Ono and Ishida (1981) is selected to develop the process design since it has the highest score in the multi-criteria decision analysis.

Its main advantages are: (i) the rate law allows a precise modeling of the reaction system, (ii) the reaction pressure (1–2 bar), temperature (250 °C) and ammonia:phenol ratio (9.2:1) are significantly lower than the operating conditions required by more established processes, thus improving process economics and increasing process safety since leaks can be more easily controlled (Heikkilä, 1999), (iii) the reaction mechanism is safer since, in contrast to the nitration of benzene, the reactants and byproducts generated are not unstable (null reactivity index according to NFPA standard) and strong acids are not required in high concentrations, (iv) the raw materials needed such as ammonia, hydrogen, phenol, sodium hydroxide, hydrochloric acid and methyl iso-butyl ketone (MIBK) are industrially available and (v) the cost of phenol and ammonia is lower than the price of aniline (Veritrade, 2019).

Furthermore, the byproducts generated such as cyclohexanone, cyclohexylamine and dicyclohexylamine constitute an advantage for the project as these are substances with a high market value used in nylon production, corrosion inhibition and vulcanization acceleration respectively. Therefore, they will also be recovered in order to have three additional products for sale.

Even though the presence of hydrogen on the selected synthesis route may pose a safety risk, this gas has been safely produced, stored and used for years in a variety of chemical industries (CHFCA, 2016). Additionally, the safe use of this substance is ensured by engineering controls and has a growing safety record (U.S. Department of Energy, 2019).

In order to compare the inherent safety between the nitration of benzene, the Halcon process and the synthesis route developed by Ono and Ishida (1981), the inherent safety index (ISI) methodology developed by Heikkilä (1999) was employed in this study. This index is a representative measure for assessing chemical process safety during early design stages (Husin et al., 2017), such as the one presented in this research. It is calculated by determining each sub index using the criteria given by Heikkilä (1999) and then performing the total sum for each column. A comparison between the preliminary ISI for the three processes is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

ISI for the nitration of benzene, the Halcon process and the synthesis route presented by Ono and Ishida (1981). The lower index represents a safer process.

| Sub index | Process |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitration of benzene | Halcon | Ono and Ishida (1981) | |

| Chemical interaction | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Flammability, Explosiveness & Toxic Exposure | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| Corrosiveness | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Heat of main reaction | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Heat of side reaction | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Process temperature | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Process pressure | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Equipment safety | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| ISI | 26 | 25 | 19 |

As shown in Table 2, the aniline synthesis route presented by Ono and Ishida (1981) is a safer pathway than the current commercial aniline manufacturing methods since it has the lowest ISI. This suggests the fact that the absence of unstable byproducts and strong acids, as well as low operating temperatures and pressures, are essential features for designing a safer alternative.

2.2. Reaction mechanism

The amination of phenol can be divided into two steps as shown in Eqs. (1) and (2), where the hydrogenation of phenol is the rate-limiting step (Cuypers et al., 2018; Ono and Ishida, 1981). The rate law and kinetic parameters of Eq. (1) were obtained from González-Velasco et al. (1986).

| (1) |

| (2) |

These chemical reactions were carried out in two reactors: the first one (R-101) carried out the synthesis of cyclohexanone and the second (R-102) the synthesis of aniline from the latter. According to the experimental results obtained by Ono and Ishida (1981) and given that the rate law for Eq. (2) has not been determined yet, a conversion reactor was used in the simulation environment to convert cyclohexanone into aniline with a selectivity of 71.8%. Additionally, generation of byproducts was taken into account.

Formation of cyclohexylamine given by Eq. (3) has a selectivity of 22.8% (Ono and Ishida, 1981).

| (3) |

On the other hand, formation of dicyclohexylamine given by Eq. (4) has a selectivity of 5.4% (Ono and Ishida, 1981).

| (4) |

In order to perform the simulation, it is assumed that the selectivity percentages obtained in the lab-scale experiment developed by Ono and Ishida (1981) do not vary in an industrial scale. Nevertheless, the reactor modeling should consider flow disturbances and axial dispersion effects (Bahadori, 2012) if a detailed engineering study is to be developed.

2.3. Reactor selection

The multitubular reactor was chosen since it is recommended for the synthesis of cyclohexanone via hydrogenation of phenol, as well as other relevant exothermic and endothermic industrial reactions (Moran and Henkel, 2016). Some of its technical advantages are: (i) heat transfer from the reaction medium is effective due to high transfer area; (ii) the catalyst can be evenly distributed and (iii) the separation of the catalyst from the reaction product is simple. An important advantage in terms of design and reliability is that the mathematical modeling of this reactor is well known. This allows for predicting the unit's performance with a low degree of uncertainty and reduces the risk when building the production facility (Overtoom et al., 2009; Salmi et al., 2019).

Both reactors were operated near isothermal conditions in order to control byproducts formation. Nonetheless, reaching isothermal conditions in the first reactor was complex since hydrogenation of phenol is an exothermic reaction. As a result, the temperature increased towards a local maximum value, the so-called reactor hot spot. This phenomenon had to be mitigated because it could deactivate the catalyst, increase the corrosion rate, decrease the selectivity and, overall, decrease process safety (Salmi et al., 2019).

Different strategies can be devised to decrease the magnitude of the hot spot: (i) dilute the catalyst with an inert solid material close to the entrance of the reactor (Salmi et al., 2019), (ii) use two independent cooling circuits through the reactor shell (Eigenberger and Ruppel, 2012) and (iii) dilute the feed with an inert substance, such as steam (Dimian and Bildea, 2008). For simulation purposes, strategies (ii) and (iii) were used to decrease the magnitude of this phenomenon.

2.4. Process modeling

The aniline production process was modeled using ProMax process simulator by BR&E (Bryan Research and Engineering, 2019). Key assumptions for reaction system modeling and process design, as well as thermodynamic package selection, are shown in sections S1 – S3 of the supplementary material.

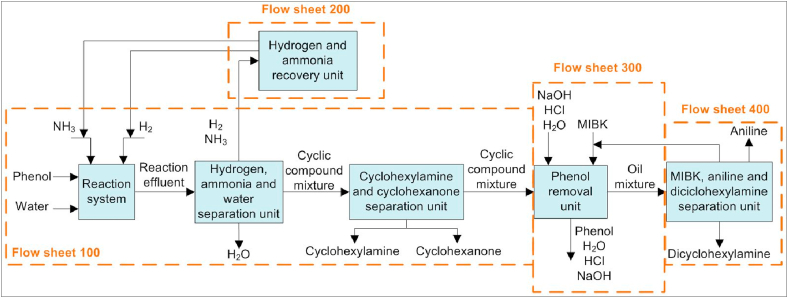

An overview of the aniline production process is presented in Figure 1. Flow sheet 100 models the reaction system as described on Section 2.2, separates hydrogen, ammonia and water from the reaction effluent and finally recovers cyclohexylamine and cyclohexanone as final products. Flow sheet 200 models the separation of ammonia from hydrogen in order to independently recycle both gases to the reaction system in flow sheet 100. Flow sheet 300 removes the unconverted phenol from the cyclic compound mixture incoming from flow sheet 100 using a liquid-liquid extraction unit. Lastly, flow sheet 400 separates and recycles to flow sheet 300 the organic solvent used (MIBK) in the liquid-liquid extraction unit and then recovers aniline and dicyclohexylamine as final products. The aniline production process is thoroughly explained throughout Sections 2.4.1–2.4.4.

Figure 1.

Aniline production block flow diagram.

2.4.1. Flow sheet 100: reaction system and separation units

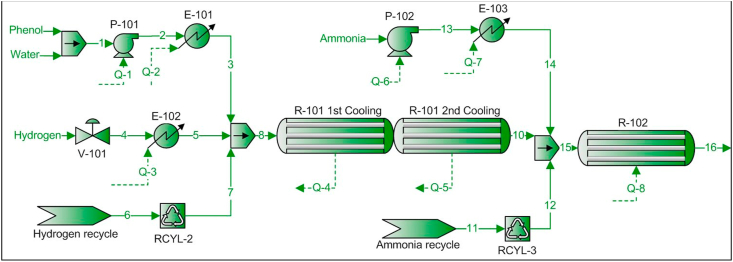

As shown in Figure 2, a gaseous phenol, hydrogen and water mixture (stream 8) at 250 °C and 2 bar enters the multitubular cyclohexanone synthesis reactor (R-101). Once the reaction takes place, the exiting stream at 250 °C and 1.7 bar is mixed with ammonia at the same operating conditions and enters the multitubular aniline, cyclohexylamine and dicyclohexylamine synthesis reactor (R-102).

Figure 2.

PFD – Flow sheet 100 – Reaction system.

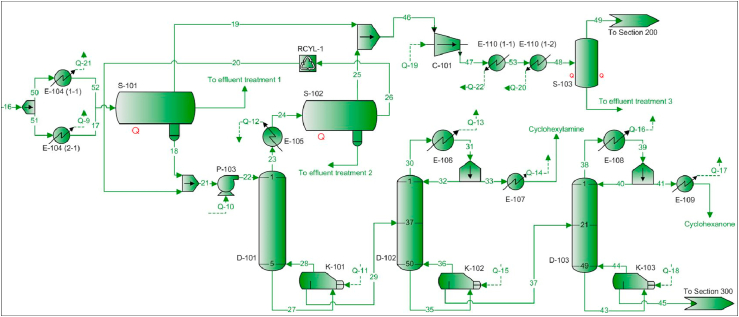

Then, as shown in Figure 3, the exiting reaction mixture (stream 16) composed by phenol, steam, hydrogen, cyclohexanone, aniline, cyclohexylamine, dicyclohexylamine and ammonia at 250 °C and 1.4 bar is cooled through a heat exchanger network (E-104) and enters a three-phase separator (S-101). The gaseous mixture (stream 19) is mostly composed of steam, ammonia and hydrogen and is sent to flow sheet 200 for further separation. The aqueous phase would be sent to an effluent treatment unit and the aniline-rich organic phase (stream 18) enters stripper D-101 to remove the remaining ammonia and water traces. On one hand, removing the dissolved ammonia allows the recycling of a larger amount of this raw material, thus reducing its purchase cost due to the excess used in R-102. On the other hand, removing water is also essential as it reduces the stage efficiency due to its high surface tension and its low miscibility with the organic phase (Gouw, 1977).

Figure 3.

PFD – Flow sheet 100 – Separation units.

At the top of D-101, the mixture containing mostly ammonia and steam (stream 23) cools down through a heat exchanger (E-105). Then, it enters a three-phase separator (S-102) to obtain an ammonia-rich gaseous phase (stream 25) that joins the gaseous stream obtained in S-101. The aqueous phase would be sent to an effluent treatment unit and the organic phase rich in cyclic compounds (stream 20) is recycled to D-101.

The bottoms product obtained from D-101 (stream 29) is an organic phase rich in aniline, phenol, cyclohexanone, cyclohexylamine and dicyclohexylamine that is subjected to a distillation sequence. According to the heuristic rules (Seader et al., 2011), cyclohexylamine is removed in a first distillation column (D-102) since it is the lightest component in the mixture. Cyclohexanone is removed as a distillate in the second column (D-103) because it is the second lightest component. The separation of the aniline-phenol-dicyclohexylamine mixture (stream 45) is explained in flow sheets 300 and 400.

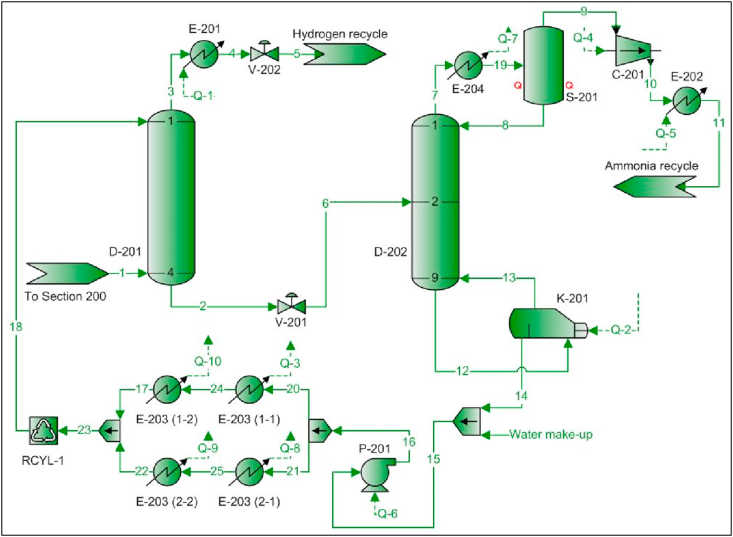

2.4.2. Flow sheet 200: hydrogen and ammonia recovery units

The gas streams obtained (stream 1) from S-101 and S-102 enter flow sheet 200 (see Figure 4) in order to recycle hydrogen and ammonia to reactors R-101 and R-102 respectively. This separation was needed since the presence of ammonia in the cyclohexanone synthesis reactor (R-101) can significantly decrease the reaction yield as it dilutes the reactants. Likewise, it causes premature deactivation of the catalyst in R-101 (Argyle and Bartholomew, 2015), which leads to increased downtime and operation and maintenance costs.

Figure 4.

PFD – Flow sheet 200 – hydrogen and ammonia recovery units.

Ammonia separation by absorption with water was employed since it can be carried out at low pressures and at temperatures of approximately 20 °C. It is also an efficient method given the high affinity between those molecules (Seader et al., 2011). Once the ammonia is absorbed in column D-201, hydrogen is recovered (stream 3) and recycled to R-101. At the bottom of the same equipment, the resulting aqueous ammonia solution (stream 2) is sent to desorption column D-202. The bottoms product (stream 14) is water that is recycled to column D-201 in order to create the absorption loop and the distilled product (stream 9) is ammonia that is recycled to R-102.

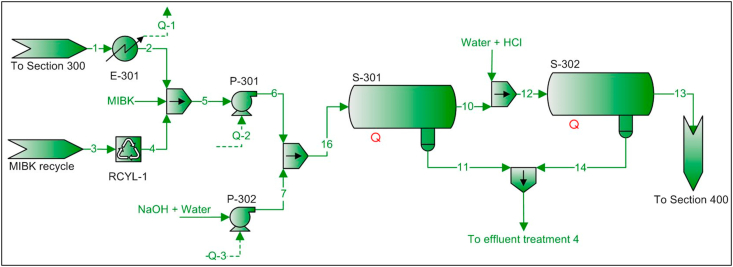

2.4.3. Flow sheet 300: phenol removal units

The purpose of this part of the process (see Figure 5) is to remove the remaining phenol from the aniline-phenol-dicyclohexylamine mixture incoming from flow sheet 100. Using a distillation column to separate this component is technically and economically unfeasible owing to the fact that the average relative volatility of the aniline-phenol mixture is 1.05. This implies that it is necessary to design distillation columns with more than 130 stages and with high reflux ratios (Seader et al., 2011). However, phenol is an acid molecule that instantaneously reacts with sodium hydroxide in aqueous medium to form the phenolate ion (Palma et al., 2007), according to Eq. (5):

| (5) |

Figure 5.

PFD – Flow sheet 300 – phenol removal units.

As the reaction proceeds, the concentration of phenol in the organic phase decreases and, simultaneously, the concentration of the phenolate ion in the aqueous phase increases, which poses a technically and economically feasible possibility to separate phenol from the aniline-rich organic phase. Nevertheless, this separation could not be carried out just by mixing an aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide with the organic phase because aniline is also soluble in water. Therefore, an organic solvent was added so that the affinity of aniline for the organic phase is greater than its affinity for the aqueous phase.

The organic solvent selected to carry out the liquid-liquid extraction was MIBK due to the following reasons: (i) it is recommended in the industrial solvent selection guide developed by SANOFI (Prat et al., 2013), which evaluates the impact of the substance on the environment, occupational safety and health, (ii) it is chemically stable if mixed with sodium hydroxide, water, aniline, phenol and dicyclohexylamine, (iii) it has a high volatility compared to that of aniline and dicyclohexylamine, (iv) it is an industrially available raw material and (v) it has a moderate cost.

First, the aniline-phenol-dicyclohexylamine mixture from flow sheet 100 (stream 1) is cooled in a heat exchanger (E-301) in order to favor the separation of the aqueous phase and the organic phase when the sodium hydroxide solution is added. This temperature decrease also increases process safety since an increase in the vapor pressure of the stream is avoided when mixed with the organic solvent, which has a low boiling point compared to the inlet temperature of the mixture from flow sheet 100.

Secondly, this stream is mixed with MIBK and an aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide. In S-301, the aqueous phase (stream 11) containing 98% of the phenol initially present in the aniline-rich organic phase (stream 1) would be sent to an effluent treatment plant. Then, the organic phase (stream 10) is mixed with an aqueous solution of hydrochloric acid in S-302 to neutralize and remove sodium hydroxide traces.

The aqueous phase obtained from S-302 (stream 14) would be mixed with stream 11 and sent to an effluent treatment plant. The amount of unconverted phenol in this mixture is 823.65 kg/h. The organic phase (stream 13) composed mostly of MIBK, aniline and dicyclohexylamine is sent to flow sheet 400.

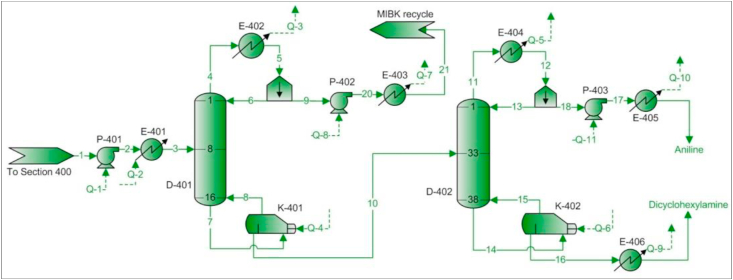

2.4.4. Flow sheet 400: MIBK, aniline and dicyclohexylamine separation units

Flow sheet 400 (see Figure 6) has two purposes: (i) separate and recycle to flow sheet 300 the MIBK present in the aniline-dicyclohexylamine-MIBK mixture entering this area and (ii) separate aniline and dicyclohexylamine.

Figure 6.

PFD – Flow sheet 400 – MIBK, aniline and dicyclohexylamine separation units.

The feed condition of saturated liquid is chosen to operate column D-401. This scenario is recommended when the concentration of heavy components in the stream is greater than or equal to 50% (Agrawal and Herron, 1997). This condition is met considering that aniline and dicyclohexylamine constitute 52% of the stream.

Once the MIBK is recovered as distillate (stream 9), it is pumped through P-402 and cooled in E-403 before being recycled to flow sheet 300. Finally, the bottoms product from column D-401 (stream 10) enters a second distillation column (D-402) in which aniline and dicyclohexylamine are separated as distillate and bottoms products respectively.

3. Methodology

The following methodology applied for the process described in Section 2.4. Plant capacity is 50000 metric tonnes of aniline. Product purity required for aniline, cyclohexylamine and dicyclohexylamine is 99.5% wt., while for cyclohexanone is 99.0% wt.

3.1. Equipment selection and sizing

Equipment sizing was developed in order to obtain key specifications such as heat transfer area and vessel weight, which are the required parameters to estimate total equipment cost. In the case of pressure vessel sizing, a minimum practical wall thickness was considered if the one calculated was below the recommended values by the ASME BPV Code Sec. VIII D.1 (Towler and Sinnott, 2013). Specific sizing methodology is shown through Sections S4 – S9 of the supplementary material.

3.2. Environmental metric

The E-factor was calculated in order to assess the environmental impact of the aniline production process. As seen in Eq. (6), this metric relates the amount of waste generated per unit of manufactured product:

| (6) |

For bulk chemical production processes, as is the present case, the acceptable range for this parameter is 1–5 tonne of waste per tonne of product (Sheldon, 2017).

3.3. Economic analysis

The economic analysis was comprised by the following three aspects: (i) the CAPEX calculation, (ii) the OPEX calculation and (ii) the NPV calculation.

The CAPEX was calculated by adding up the fixed capital investment (FCI) and the working capital (WC). The FCI was calculated by adding up the purchase cost of equipment (PC), the direct costs (DC) and the indirect costs (IC).

The PC was calculated with the empirical correlations provided by Towler and Sinnott (2013) in the year 2010, which correspond to a Chemical Engineering Plant Cost Index (CEPCI) of 532.9. The CEPCI of 607.5 in 2019 was used to have a more accurate estimate of the purchase cost. Additionally, the construction material to be employed is stainless steel 304 according to the chemical compatibility charts (Craig and Anderson, 1995).

The DC are comprised by the installation, instrumentation and control, piping, electrical systems, buildings, service facilities and land costs. They were calculated according to the percentages recommended by Peters et al. (2003), as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Direct cost calculation.

| Direct costs | |

|---|---|

| Installation | 40% of PC |

| Instrumentation and Control | 40% of PC |

| Piping system | 45% of PC |

| Electrical system | 25% of PC |

| Buildings | 40% of PC |

| Service facilities | 70% of PC |

| Land | 6% of PC |

The IC are comprised by the engineering and supervision, contingencies, legal expenses, construction expenses and contractor's fee costs. They were calculated according to the percentages recommended by Peters et al. (2003), as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Indirect cost calculation.

| Indirect costs | |

|---|---|

| Engineering & supervision (E&S) | 17.5% of DC |

| Contingencies | 10% of (DC + E&S) |

| Legal expenses | 2% of (DC + E&S) |

| Construction expenses and contractor's fee | 15% of (DC + E&S) |

Finally, the WC was calculated assuming it is 15% of the CAPEX (Peters et al., 2003).

The OPEX is comprised by variable and fixed costs.

The variable cost includes raw materials, utilities, labor, effluent treatment, supervision, quality control, indirect plant costs, research and development and administrative costs. The raw material (Veritrade, 2019) and utility costs (Turton et al., 2009) are shown in Tables 5 and 6. It should be noted that utilities such as electrical power, cooling water, chilled water and steam are not explicitly modeled; rather it is assumed that these are charged at a fixed rate by an off-site.

Table 5.

Raw material costs.

| Raw material | Unit cost ($/t) |

|---|---|

| Phenol | 815.00 |

| Ammonia | 289.00 |

| Hydrogen | 655.00 |

| MIBK | 1468.00 |

| Sodium hydroxide | 280.00 |

| Hydrochloric acid | 150.00 |

| Water | 3.07 |

| Pd/Al2O3 (R-101) | 1400.00 |

| Pd/Al2O3 (R-102) | 1400.00 |

Table 6.

Utility costs.

| Utility | Unit cost |

|---|---|

| Low pressure steam, LPS ($/t) | 27.70 |

| Medium pressure steam, MPS ($/t) | 28.31 |

| High pressure steam, HPS ($/t) | 29.97 |

| Chilled water ($/t) | 0.19 |

| Cooling water ($/t) | 0.05 |

| Electrical power ($/kWh) | 0.074 |

The labor cost (LC) is $ 29.6/h and the man-hours (MH) required by the process were calculated assuming 1.17 MH are required for each manufactured tonne of liquid product (Peters et al., 2003).

In relation to the effluent treatment cost, it is assumed that wastewater is treated by an outsourcer at a fixed cost per unit mass of $ 0.73/t, which includes reverse osmosis, hydrogen peroxide oxidation, flocculation and sedimentation (Guo et al., 2014).

Supervision, quality control, indirect plant costs, research and development and administrative costs were determined according to the percentages recommended by Peters et al. (2003), as shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Variable cost calculation.

| Variable costs | |

|---|---|

| Supervision (SUP) | 15% of LC |

| Quality control | 15% of LC |

| Indirect plant costs | 60% of (LC + SUP + MNT) |

| Research and development | 2% of Gross Annual Sales |

| Administrative costs | 20% of (LC + SUP + MNT) |

Finally, the fixed cost includes equipment maintenance, operational supplies, local taxes, rent, insurance and financial interests. These costs were determined according to the percentages recommended by Peters et al. (2003), as shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Fixed cost calculation.

| Fixed costs | |

|---|---|

| Equipment maintenance (MNT) | 6% of FCI |

| Operational supplies | 0.75% of FCI |

| Local taxes | 2.5% of FCI |

| Rent | 10% of Land |

| Insurance | 0.7% of FCI |

| Financial interests | 5% FCI |

The NPV was calculated taking into account the following key assumptions:

-

•

The selling price of aniline, cyclohexanone, cyclohexylamine and dicyclohexylamine is 1840.00, 1700.00, 3700.00 and 2500.00 $/t respectively (Alibaba, 2019a, 2019b; Veritrade, 2019).

-

•

The weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is 20%.

-

•

The U.S. federal corporate income tax rate is 21%.

-

•

A Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) 5-year schedule depreciation method is employed.

-

•

Economic life of the project is 10 years.

3.4. Heat integration

A pinch analysis was performed using methodology developed by IChemE (2005) to identify the streams that could be integrated in order to increase process profitability. Each integration was done separately on the simulation software. The NPV corresponding to each integration was calculated and compared to the base NPV. The energy integrations that increased the base NPV were coupled to recalculate this economic indicator. It should be noted that a minimum approach temperature of 10 °C was assumed in order to size the additional heat exchanger required for each integration (Towler and Sinnott, 2013).

This analysis did not consider the cooling or heating streams through the reactors nor those of the reboilers and condensers since process operability and control may be impacted by increasing the number of interdependencies (Marton et al., 2016). Nonetheless, this hypothesis should be further analyzed by performing a detailed engineering study.

3.5. NPV sensitivity analysis

Five parameters were selected to perform the sensitivity analysis. Towler and Sinnott (2013) recommend varying the FCI, the product price (aniline) and the raw material unit cost (phenol) between 0% and 50%, -20% and 0%, and 0% and +30% respectively. Nonetheless, the evaluation intervals were expanded in order to test process NPV under more conservative and rigorous scenarios. FCI was varied between 0% and +100%, aniline selling price between -50% and 0%, and phenol unit cost between 0% and +50%.

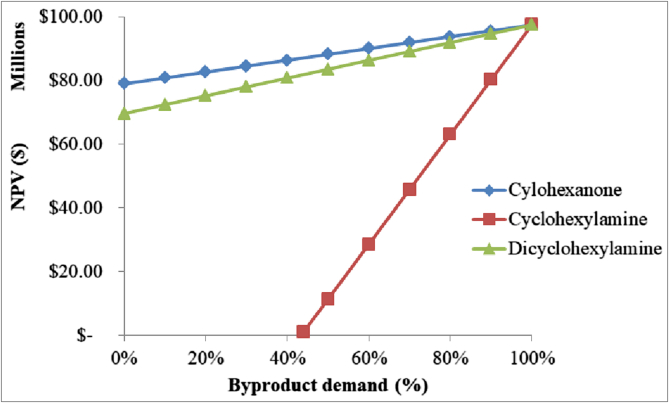

Cyclohexanone, cyclohexylamine and dicyclohexylamine demand was varied in a range of 100%–0% to evaluate how the process NPV depends on each byproduct. A market demand of 100% for the byproduct being analyzed implies that every manufactured stock is sold, whereas a market demand of 0% means that the byproduct is not being sold.

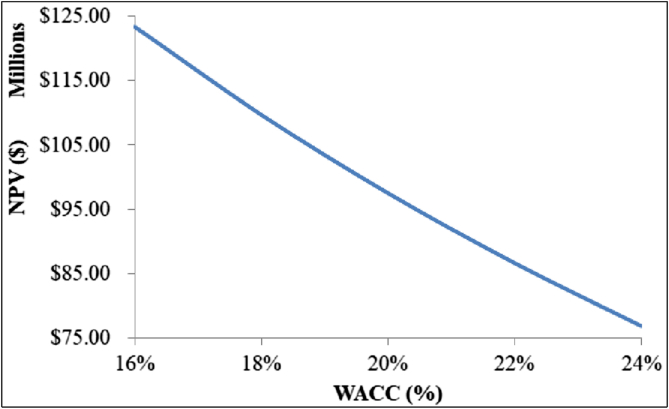

WACC was varied between 16% and 24% because it is the recommended range to evaluate new technologies producing an established market product (Peters et al., 2003).

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Reactor hot spot

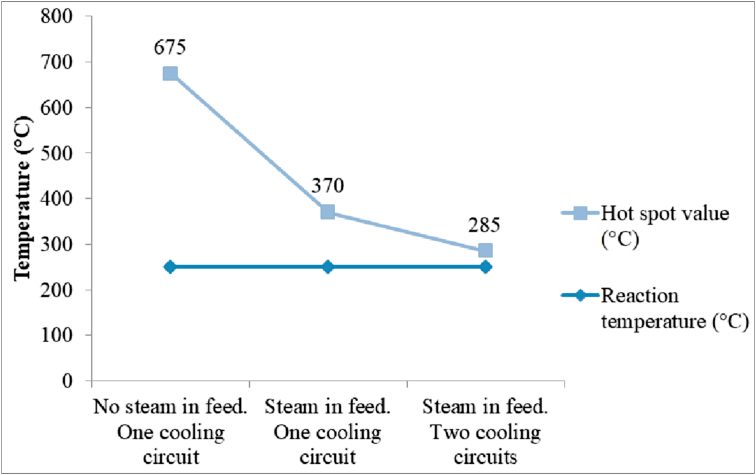

Figure 7 shows the simulation results obtained after applying the aforementioned hot spot mitigation strategies to the cyclohexanone synthesis reactor (R-101).

Figure 7.

Hot spot value with different mitigation strategies in the first reactor (R-101).

Extreme caution should be taken into consideration when modeling a reactor since the process validity depends on the performance of the reaction system. As shown in Figure 7, the hot spot value is 425 °C greater than the ideal reaction temperature when no mitigation strategies are applied, so it is essential to apply those that best fit the process at an early design stage since they will affect process requirements. For instance, the presence of steam as an inert substance in the reactor feed will affect equipment size and energy requirements downstream.

Using steam reduces the hot spot value by 305 °C, which is a significant improvement that increases process safety. The steam acts as an inert substance diluting the reaction mixture, causing the rate of reaction to decrease and, therefore, the hot spot magnitude as well. However, when the two cooling circuits are coupled, the hot spot value decreases 390 °C overall since they allow a more uniform temperature profile across the reactor shell, thus increasing heat transfer between the reaction mixture and the cooling water (Eigenberger and Ruppel, 2012).

To summarize, the hot spot value is only 35 °C higher than the ideal reaction temperature when both of the mitigation strategies are employed, in contrast to the 425 °C increase. A hot spot value of 285 °C is acceptable since the hydrogenation of phenol is effective in the temperature range of 220–290 °C (González-Velasco et al., 1986).

4.2. Mass and energy balances

Tables 9 and 10 show the simulation results for the mass and energy balances.

Table 9.

Simulation results for total product and raw material mass flow.

| Classification | Component | Mass flow (kg/h) |

|---|---|---|

| Products | Aniline | 5764.27 |

| Cyclohexanone | 422.87 | |

| Cyclohexylamine | 1761.32 | |

| Dicyclohexylamine | 426.00 | |

| Raw materials | Phenol | 9616.78 |

| Ammonia | 2399.18 | |

| Hydrogen | 168.73 | |

| MIBK | 37.25 | |

| Water | 8175.33 | |

| Sodium hydroxide | 439.97 | |

| Hydrochloric acid | 51.05 | |

| Waste | Effluents | 12504.05 |

Table 10.

Simulation results for total energy requirements.

| Utility | Energy requirement (MW) |

|---|---|

| HPS | 15.9 |

| MPS | 3.4 |

| LPS | 12.0 |

| Cooling water | 29.2 |

| Chilled water | 6.3 |

| Electrical power | 2.3 |

As seen in Table 10, the HPS usage constitutes 51% of the total heating energy requirement. In order to decrease utility costs, improve cooling water utilization and reduce the environmental impact, the heat integration analysis developed in Section 4.5 is focused on reducing this particular energy requirement.

4.3. Environmental impact

According to Table 9, the E-factor is 1.5 tonnes of waste per tonne of manufactured product, a value near the lower limit established for bulk chemical production processes. Hence, the conceptual design explained throughout Sections 2.4.1–2.4.4 has a low environmental impact. The E-factor can be further reduced by recovering the water and unconverted phenol from the effluent stream at flow sheet 300, as it constitutes 57% of the total waste generated by the process.

4.4. Net present value

The designed aniline production process is profitable with a NPV of USD 93.5 million, providing an alternative synthesis route to replace the nitration of benzene with a safer process. A heat integration analysis is developed in Section 4.5 to further improve process profitability.

4.5. Heat integration

According to a pinch analysis, the minimum cooling and heating utility required are 16059.22 kW and 493.49 kW respectively. In order to achieve such conditions a mixed-integer nonlinear program must be coded to know with certainty which combination of streams to integrate (Furman and Sahinidis, 2002). Even though this formulation could allow reaching those cooling and heating targets, it does not guarantee an increase in process profitability because additional heat exchangers and pressure drops may lead to higher capital and operation costs. Therefore, three combinations with the highest energy requirements were chosen and independently analyzed in order to increase the profitability of the process, as shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

Thermodynamic properties of the useable streams.

| Stream Name | Flow sheet | Supply Temperature (°C) | Target Temperature (°C) | Heat Duty (kW) | Heat capacity (kW/K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47 | 100 | 197.82 | 15.66 | 2600.8 | 14.28 |

| 16 | 100 | 250.28 | 26.28 | 8003.6 | 35.73 |

| 13 | 100 | -32.98 | 250.02 | 1336.1 | 4.72 |

| 2 | 100 | 49.59 | 251.93 | 4413.1 | 21.81 |

| 16 | 200 | 103.40 | 17.22 | 7188.8 | 83.41 |

| 10 | 200 | 71.05 | 250.00 | 1535.8 | 8.58 |

Since most of the useable streams are below the pinch, the criterion used to select the combinations is that the heat capacity of the hot stream must be greater than the heat capacity of the cold stream (Smith, 2005).

Stream 16 in flow sheet 200 was integrated with stream 13 in flow sheet 100 (First integration) because the difference in their heat capacities is the highest, which allows to take full advantage of the energy stored in stream 16 and thus decrease the amount of HPS required for stream 13.

Stream 16 in flow sheet 100 was integrated with stream 2 from same flow sheet (Second integration) since its temperature and heat capacity are greater than those of stream 47 (found in same flow sheet). By process elimination, stream 47 was integrated with stream 10 from flow sheet 200 (Third integration).

4.6. Economic analysis with heat integration

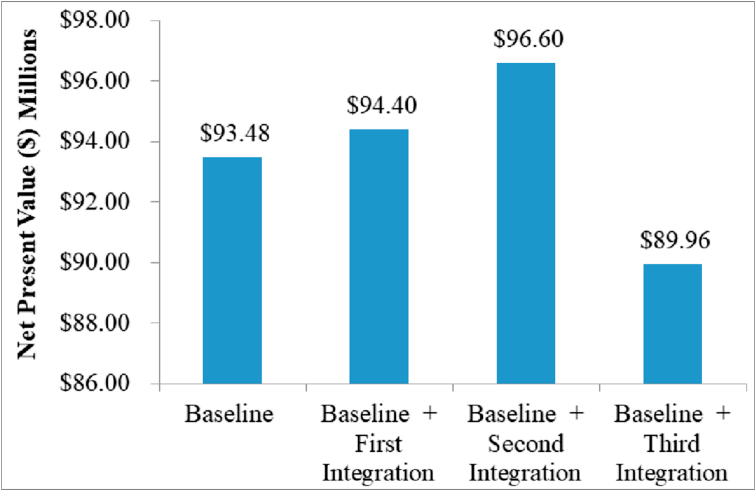

Figure 8 shows how the process NPV fluctuated when the first, second and third integrations were coupled into the baseline process.

Figure 8.

Process NPV corresponding to the first, second and third integration.

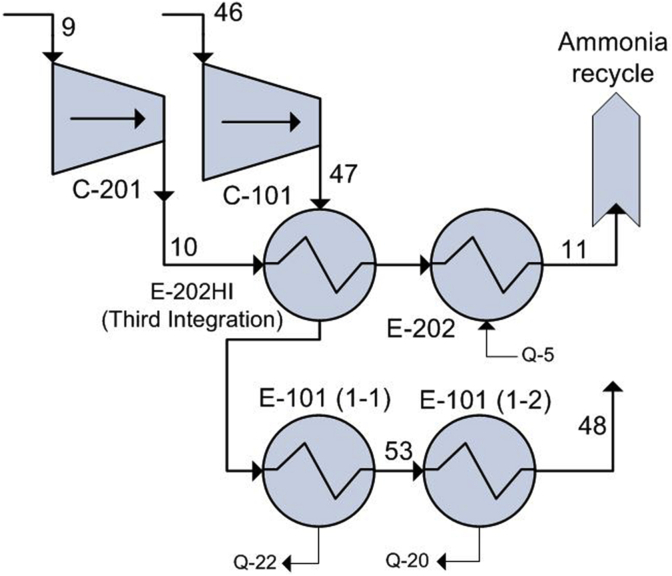

Unlike the first and second integration, the third integration was not coupled into the base process since it decreased its NPV. As shown in Figure 9, the pressure drop generated by the additional heat exchanger (E-202HI) required an increase in compressor power from 418.42 (C-201) and 1826.44 kW (C-101) to 655.93 kW and 1842.13 kW respectively, which did not compensate the decrease in heating and cooling utility costs. Additionally, the transfer area required by E-202HI (452.8 m2) is significantly larger than the one required by E-202 in the base case scenario (162.6 m2) since gas-gas heat transfer is less effective than saturated steam-gas transfer.

Figure 9.

PFD corresponding to the third integration.

In order to reduce compressor power and attempt to increase profitability, the tube pitch of the heat exchangers involved in this integration was changed from 1.25 to 1.30. Nevertheless, this generated a significant increase in the total capital investment, also resulting in a lower NPV (USD 90.7 million). To sum up, the first and second integration were coupled into the baseline process to recalculate the NPV. A summary of the economic evaluation with and without heat integration is shown in Table 12.

Table 12.

Economic evaluation results for the baseline and integrated processes.

| Parameter | Baseline process | Integrated process |

|---|---|---|

| CAPEX ($ M) | 75.3 | 75.0 |

| OPEX ($ M/yr) | 108.9 | 107.8 |

| NPV ($ M) | 93.5 | 97.5 |

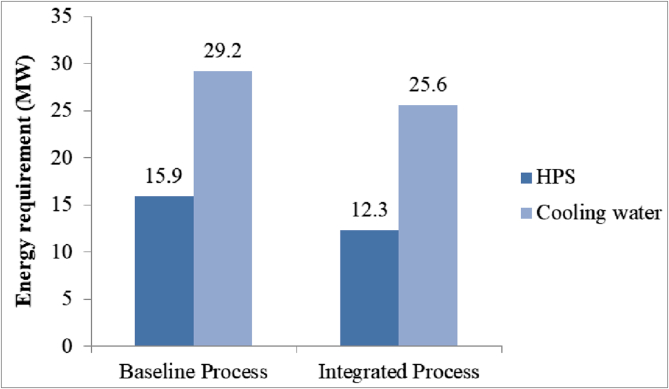

These heat integrations also decreased the total heating and cooling energy requirements, as shown in Figure 10. HPS and cooling water usage was reduced by 23% and 12% respectively, providing annual savings of USD 1.1 million and consequently increasing process profitability.

Figure 10.

HPS and cooling water energy requirement for the baseline and integrated processes.

4.7. Sensitivity analysis

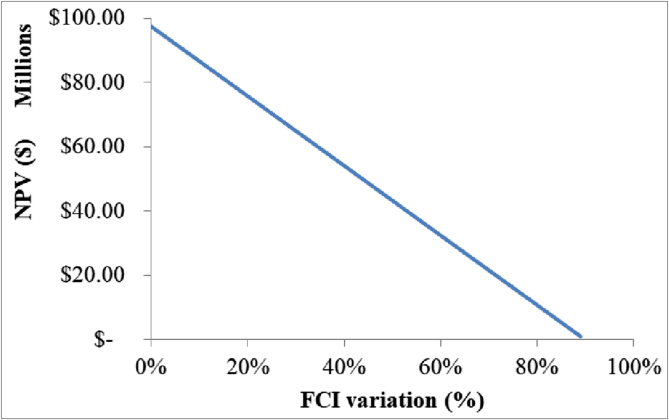

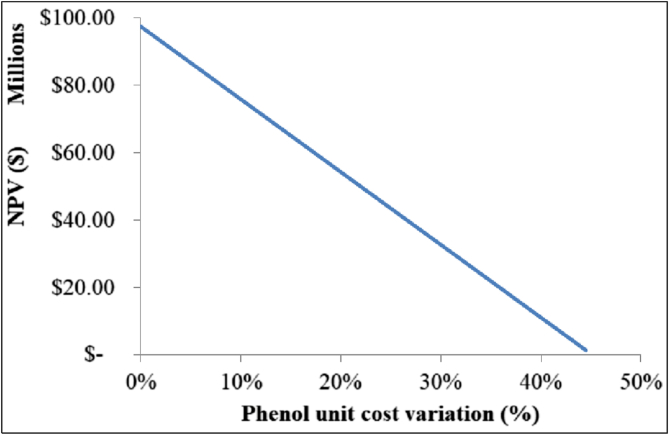

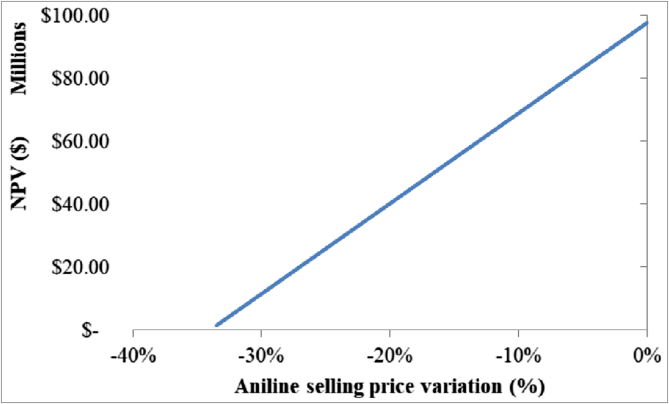

Unit costs and prices may change over time given that the bulk chemical market is dynamic, mainly due to global supply and demand fluctuations. Since these variations may result in different economic outcomes for the designed aniline production process, Figures 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15 show how the NPV changes with the proposed scenarios given in Section 3.5.

Figure 11.

NPV variation in the selected FCI range.

Figure 12.

NPV variation in the selected phenol unit cost range.

Figure 13.

NPV variation in the selected aniline selling price range.

Figure 14.

NPV variation when the byproduct demand decreases.

Figure 15.

NPV variation in the selected WACC range.

According to Figure 11, the process is profitable in the range of 0% to +89% FCI, meaning that redundant equipment and better instrumentation and control can be purchased in order to improve operational reliability, increase process safety and avoid unexpected plant shutdowns. Additionally, these results constitute a positive indicator for future detailed engineering studies since the process may still be profitable when equipment sizing is more precisely determined.

According to Figure 12, the process is profitable until the phenol unit cost increases by 44.5%, or when it fluctuates in the range of 815–1178 $/t. This is a positive indicator since in the 2016–2017 period the phenol cost reached a maximum of 1146.4 $/t due to high benzene feedstock costs (Dietrich, 2017). Nonetheless, to avoid the impact of these unexpected peaks, the aniline manufacturing facility could be installed near a phenol production plant in order to secure higher profit margins from efficient logistic cost of this raw material.

Then, as shown in Figure 13, the process is profitable until the aniline selling price decreases by 33.5%, or when it fluctuates in the range of 1840–1224 $/t. Hence, there is reasonable evidence to suggest that this process will be profitable even during global supply and demand variations since aniline price was reported as 1433 $/t in 2008 (I.C.I.S, 2008) and 1800 $/t in 2012 (Pan, 2012), prices that fall within the range established before. Nevertheless, it is essential to establish negotiation terms with the buyer during economic volatility periods. Additionally, the process may be vulnerable to the entry of a new technology that produces aniline with a lower price than the one proposed in this present work. However, it is important to underscore the high robustness of the process given its added value of process safety and byproduct generation that would normally render it unprofitable.

Finally, as illustrated in Figure 14, the process is profitable even if cyclohexanone and dicyclohexylamine are not sold. Even though the cyclohexylamine market demand can only decrease to 44% before the process NPV becomes negative, this scenario may be unrealistic in view of the fact that this byproduct's demand is projected to have a sustainable growth in North America, Europe and Asia, fueled by applications in artificial sweeteners, corrosion inhibitors, synthetic chemicals and water treatment industries (Global Market Insights, 2017). It is important to note that demand forecasts may be susceptible to abrupt fluctuations due to unpredictable events such as health, social, political or economic situations. To avoid the impact of these negative scenarios, reduce the dependence on cyclohexylamine sales and improve the predictability of the economic indicators, future work must be focused on developing more selective catalysts to reduce byproduct formation.

Finally, according to Figure 15, the process is profitable across the whole range of possible WACC values, which is a positive indicator for future shareholders.

5. Conclusions

Simulation results revealed that the designed aniline production process is technically and economically feasible with a NPV of USD 97.5 million. Consequently, this project can proceed to further evaluation stages where improvements such as phenol recovery from flow sheet 300, water recycling and more heat integrations can be developed. Moreover, the E-factor of 1.5 tonnes of waste per tonne of product suggests that the design might be environmentally friendly. However, a life cycle assessment should be developed once a detailed engineering study is undertaken to further confirm the environmental viability of this process.

In relation to the rigorous sensitivity analysis scenarios, the conceptual design could support FCI changes of up to +89%, thus posing an opportunity to improve operational reliability and process safety through equipment redundancy and better instrumentation and control respectively. It was shown that the proposed process is robust because it does not depend on cyclohexanone or dicyclohexylamine sales. The cyclohexylamine sales have a significant impact on process profitability as this byproduct's demand can only decrease to 44%, but given that its market is projected to grow, it may be unlikely for the process to have unsold stocks. Even though the process is sensitive to the unit cost of phenol, its profitability could be increased if it is installed near a phenol production plant, thus avoiding unexpected cost fluctuations and keeping the range between 815 – 1178 $/t. Moreover, aniline price can be varied in a range of 1224–1840 $/t to accommodate for market dynamics. Finally, it was demonstrated that aniline can be produced with greater safety than the processes currently used since low pressures are required and no unstable byproducts are generated. All these make the present conceptual design an interesting technological alternative for aniline production.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Sergio Bugosen: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Ivan D. Mantilla: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Francisco Tarazona-Vasquez: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

Supplementary Material

References

- Agrawal R., Herron D.M. Optimal thermodynamic feed conditions for distillation of ideal binary mixtures. AIChE J. 1997;43:2984–2996. [Google Scholar]

- Alibaba . 2019. Shenyang East Chemical Science-Tech [WWW Document]. Cyclohexylamine Cas108-91-8.https://bit.ly/2Xl40jC URL. [Google Scholar]

- Alibaba . 2019. Haihang Industry Co. [WWW Document]. Stable Qual. Dicyclohexylamine.https://bit.ly/3eGiQak URL. [Google Scholar]

- Argyle M.D., Bartholomew C.H. Heterogeneous catalyst deactivation and regeneration: a review. Catalysts. 2015;5:145–269. [Google Scholar]

- Badeen C., Turcotte R., Hobenshield E., Berretta S. Thermal hazard assessment of nitrobenzene/dinitrobenzene mixtures. J. Hazard Mater. 2011;188:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahadori A. Prediction of axial dispersion in plug-flow reactors using a simple method. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2012;33:200–205. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan Research and Engineering . 2019. ProMax 5.0. [Google Scholar]

- CHFCA . 2016. Canadian Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Association [WWW Document]. Hydrog. - A New Era Energy.http://www.chfca.ca/fuel-cells-hydrogen/about-hydrogen/ URL. [Google Scholar]

- Craig B., Anderson D. second ed. ASM International; Ohio: 1995. Handbook of Corrosion Data. [Google Scholar]

- Cuypers T., Tomkins P., De Vos D.E. Direct liquid-phase phenol-to-aniline amination using Pd/C. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2018;8:2519–2523. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich J. 2017. Independent Commodity Intelligence Services (I.C.I.S) [WWW Document]. Price Mark. Trends US Phenol, Acetone Face Uptrend post Harvey.https://www.icis.com/explore/resources/news/2017/09/07/10141110/price-and-market-trends-us-phenol-acetone-face-uptrend-post-harvey/ URL. [Google Scholar]

- Dimian A., Bildea C. Chemical Process Design: Computer-Aided Case Studies. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2008. Phenol hydrogenation to cyclohexanone; pp. 129–172. [Google Scholar]

- Eigenberger G., Ruppel W. Catalytic fixed-bed reactors. Ullmann’s Encycl. Ind. Chem. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Furman K.C., Sahinidis N.V. A critical review and annotated bibliography for heat exchanger network synthesis in the 20th century. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2002;41:2335–2370. [Google Scholar]

- Global Market Insights . 2017. Global Market Insights [WWW Document]. Ind. Cyclohexylamine Mark. Size, Ind. Anal. Report, Reg. Outlook, Appl. Dev. Potential, Price Trend, Compet. Mark. Share Forecast. 2019 - 2025.https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/industrial-cyclohexylamine-market URL. [Google Scholar]

- González-Velasco J.R., Gutiérrez-Ortiz J.I., González-Marcos J.A., Romero A. Kinetics of the selective hydrogenation of phenol to cyclohexanone over a Pd-alumina catalyst. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 1986;32:505–512. [Google Scholar]

- Gouw T. Removal of water in the distillation of hydrocarbon mixtures. J. Anal. Chem. 1977;49:1887–1888. [Google Scholar]

- Guo T., Englehardt J., Wu T. Review of cost versus scale: water and wastewater treatment and reuse processes. Water Sci. Technol. 2014;69:223–234. doi: 10.2166/wst.2013.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkilä A. Helsinki University of Technology; 1999. Inherent Safety in Process Plant Design: an Index-based Approach. [Google Scholar]

- Husin M.F., Hassim M.H., Ng D.K.S. A heuristic framework for process safety assessment during research and development design stage. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2017;56:739–744. [Google Scholar]

- I.C.I.S . 2008. I.C.I.S Limited [WWW Document]. Chem. Profile Aniline.https://bit.ly/2LHiPZ3 URL. [Google Scholar]

- IChemE . 2005. Pinch Analysis Spreadsheet. [Google Scholar]

- Katada N., Iijima S., Igi H., Niwa M. Synthesis of aniline from phenol and ammonia over zeolite beta. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 1997;105 B:1227–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Kent J. 2007. Kent and Riegel’s Handbook of Industrial Chemistry and Biotechnology, 11th Ed. Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Kletz T. fifth ed. Butterworth-Heinemann; Burlington, Massachusetts: 2009. What Went Wrong? Case Histories of Process Plant Disasters and How They Could Have Been Avoided. [Google Scholar]

- Lamture J. first ed. Notion Press; Chetpet, Chennai: 2018. Aniline and its Analogs. [Google Scholar]

- Lodal P.N. Distant replay: what can reinvestigation of a 40-year-old incident tell you? A look at Eastman Chemical’s 1960 aniline plant explosion. Process Saf. Prog. 2004;23:221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Marton S., Svensson E., Harvey S. ECEEE Industrial Efficiency. European Council for an Energy Efficient Economy; Berlin: 2016. Investigating operability issues of heat integration for implementation in the oil refining industry. [Google Scholar]

- Moran S., Henkel K.-D. Reactor types and their industrial applications. Ullmann’s Encycl. Ind. Chem. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Odu G.O. Weighting methods for multi-criteria decision making technique. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2019;23:1449–1457. [Google Scholar]

- Ono Y., Ishida H. Amination of phenols with ammonia over palladium supported on alumina. J. Catal. 1981;72:121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Overtoom R., Fabricius N., Leenhouts W. Proceedings of the 1st Annual Gas Processing Symposium. Elsevier B.V.; 2009. Shell GTL, from bench scale to world scale; pp. 378–386. [Google Scholar]

- Palma M.S.A., Paiva J.L., Zilli M., Converti A. Batch phenol removal from methyl isobutyl ketone by liquid-liquid extraction with chemical reaction. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2007;46:764–768. [Google Scholar]

- Pan V. 2012. Independent Commodity Intelligence Services (I.C.I.S) [WWW Document]. China’s Shandong Haihua Runs Aniline Unit 70% after Restart.https://www.icis.com/explore/resources/news/2012/07/25/9580734/china-s-shandong-haihua-runs-aniline-unit-at-70-after-restart/ URL. [Google Scholar]

- Partovi F. An analytical model of process choice in the chemical industry. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2007;105:213–227. [Google Scholar]

- Peters M., Timmerhaus K., West R. fifth ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2003. Plant Design and Economics for Chemical Engineers. [Google Scholar]

- Prat D., Pardigon O., Flemming H.W., Letestu S., Ducandas V., Isnard P., Guntrum E., Senac T., Ruisseau S., Cruciani P., Hosek P. Sanofi’s solvent selection guide: a step toward more sustainable processes. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2013;17:1517–1525. [Google Scholar]

- Pulidindi K., Chakraborty S. Synthetic & bio-based aniline market size by process (reduction, substitution), by product (synthetic, bio-based) by application (MDI, rubber processing chemicals, agrochemicals, dyes & pigments), by end-user (construction, rubber products, transportation [WWW document] Glob. Mark. Insights. 2017 https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/synthetic-and-bio-based-aniline-market URL. [Google Scholar]

- Salmi T., Mikkola J., Wärnå J. second ed. CRC Press Taylos & Francis; New York: 2019. Chemical Reaction Engineering and Reactor Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Schiermeier Q. Chinese cities face toxic spills [WWW Document] Nature. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Seader J., Henley E., Roper D. third ed. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2011. Separation Process Principles. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon R.A. The: E factor 25 years on: the rise of green chemistry and sustainability. Green Chem. 2017;19:18–43. [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. second ed. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, West Sussex: 2005. Chemical Process Design and Integration. [Google Scholar]

- Towler G., Sinnott R. second ed. Elsevier; Oxford: 2013. Chemical Engineering Design: Principles, Practice and Economics of Plant and Process Design. [Google Scholar]

- Trebilcock R.W., Dharmavaram S. Assessment of chemical reactivity hazards for nitration reactions and decomposition of nitro-compounds. Chem. Process Des. Saf. Nitration Ind. 2013;1155:121–139. [Google Scholar]

- Turton R., Bailie R., Whiting W., Shaeiwitz J. third ed. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: 2009. Analysis, Synthesis, and Design of Chemical Processes. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Energy Office of energy efficiency & renewable energy [WWW document] Safe Use Hydrog. 2019 https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/safe-use-hydrogen URL. [Google Scholar]

- Veritrade . 2019. Veritrade [WWW Document]https://www.veritradecorp.com/ URL. [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Yang Y., Zhang L. Research on the direct amination of benzene to aniline by NiAlPO 4 –5 catalyst. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019;33:1–12. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.