Key Points

Question

What is the role of neutrophil extracellular traps in coronary thrombosis in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and myocardial infarction?

Findings

This case series report demonstrated a high burden of neutrophil extracellular traps (median density, 61%) in the coronary thrombi of 5 patients with ST-elevated myocardial infarction and COVID-19, compared with a historical series of 50 patients without COVID-19 (median NET density, 19%), which was a significant difference.

Meaning

Targeting intravascular neutrophil extracellular traps might be a relevant goal of treatment and a feasible way to prevent coronary thrombosis in patients with severe COVID-19.

This case series study reports formation of neutrophil extracellular traps in 5 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 with ST-elevated myocardial infarction and compares findings with 50 patients who had experienced myocardial infarction before the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.

Abstract

Importance

Severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is characterized by the intense formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), leading to the occlusion of microvessels, as shown in pulmonary samples. The occurrence of ST-elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) is a serious cardiac manifestation of COVID-19; the intrinsic mechanism of coronary thrombosis appears to still be unknown.

Objective

To determine the role of NETs in coronary thrombosis in patients with COVID-19.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a consecutive series of patients with COVID-19 at an academic tertiary hospital in Madrid, Spain, who underwent primary coronary interventions for STEMI in which coronary aspirates were obtained in the catheterization laboratory using a thrombus aspiration device. Patients with COVID-19 who experienced a STEMI between March 23 and April 11, 2020, from whom coronary thrombus samples were aspirated during primary coronary intervention, were included in the analysis. These patients were compared with a series conducted from July 2015 to December 2015 of patients with STEMI.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The presence and quantity of NETs in coronary aspirates from patients with STEMI and COVID-19. The method for the analysis of NETs in paraffin-embedded coronary thrombi was based on the use of confocal microscopy technology and image analysis for the colocalization of myeloperoxidase-DNA complexes and citrullinated histone H3. Immunohistochemical analysis of thrombi was also performed. Clinical and angiographic variables were prospectively collected.

Results

Five patients with COVID-19 were included (4 men [80%]; mean [SD] age, 62 [14] years); the comparison group included 50 patients (44 males [88%]; mean [SD] age, 58 [12] years). NETs were detected in the samples of all 5 patients with COVID-19, and the median density of NETs was 61% (95% CI, 43%-91%). In the historical series of patients with STEMI, NETs were found in 34 of 50 thrombi (68%), and the median NET density was 19% (95% CI, 13%-22%; P < .001). All thrombi from patients with COVID-19 were composed of fibrin and polymorphonuclear cells. None of them showed fragments of atherosclerotic plaque or iron deposits indicative of previous episodes of plaque rupture.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this small case series of patients with COVID-19 and myocardial infarction, NETs seem to play a major role in the pathogenesis of STEMI in COVID-19 disease. Our findings support the idea that targeting intravascular NETs might be a relevant goal of treatment and a feasible way to prevent coronary thrombosis in patients with severe COVID-19 disease.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has been shown to predispose patients to thrombotic disease in both venous and arterial circulation.1 This is believed to be secondary to inflammation, platelet activation, endothelial dysfunction, and stasis.2

It has been suggested that organ dysfunction in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with excessive formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and vascular damage. Moreover, autopsy studies have identified mechanical vessel obstruction by aggregated NETs as a central pathogenic determinant of COVID-19.3

Acute cardiac injury is common in patients with severe COVID-19 and contributes to patient mortality.4 The occurrence of ST-elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) is a serious cardiac manifestation of the disease,5 but the intrinsic mechanism of coronary thrombosis in COVID-19 has not been demonstrated. Here, we present an immunohistochemical and NET analysis of a series of coronary thrombi from 5 patients with COVID-19 who had a STEMI.

Methods

Ethical Approval

The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Puerta de Hierro–Majadahonda, Madrid, Spain. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants before they were included in the study.

Tissue Samples

Intracoronary aspirates were obtained during primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in the catheterization laboratory, using a thrombus aspiration device. The aspirated samples were rinsed with phosphate buffer saline immediately after extraction and fixed in neutral buffered formalin, 10%. In the Pathology Department, samples were paraffin embedded and hematoxylin and eosin stained. Perls stain was used for the detection of iron deposits to identify areas of old intraplaque hemorrhage. For immunohistochemical analysis, several antibodies (Dako [Glostrup]) were used to identify foamy macrophages (CD68), endothelial cells and platelet adhesion molecules (CD31), and neutrophil cytoplasmic myeloperoxidase.

Immunofluorescence, Visualization, and Quantification of NETs

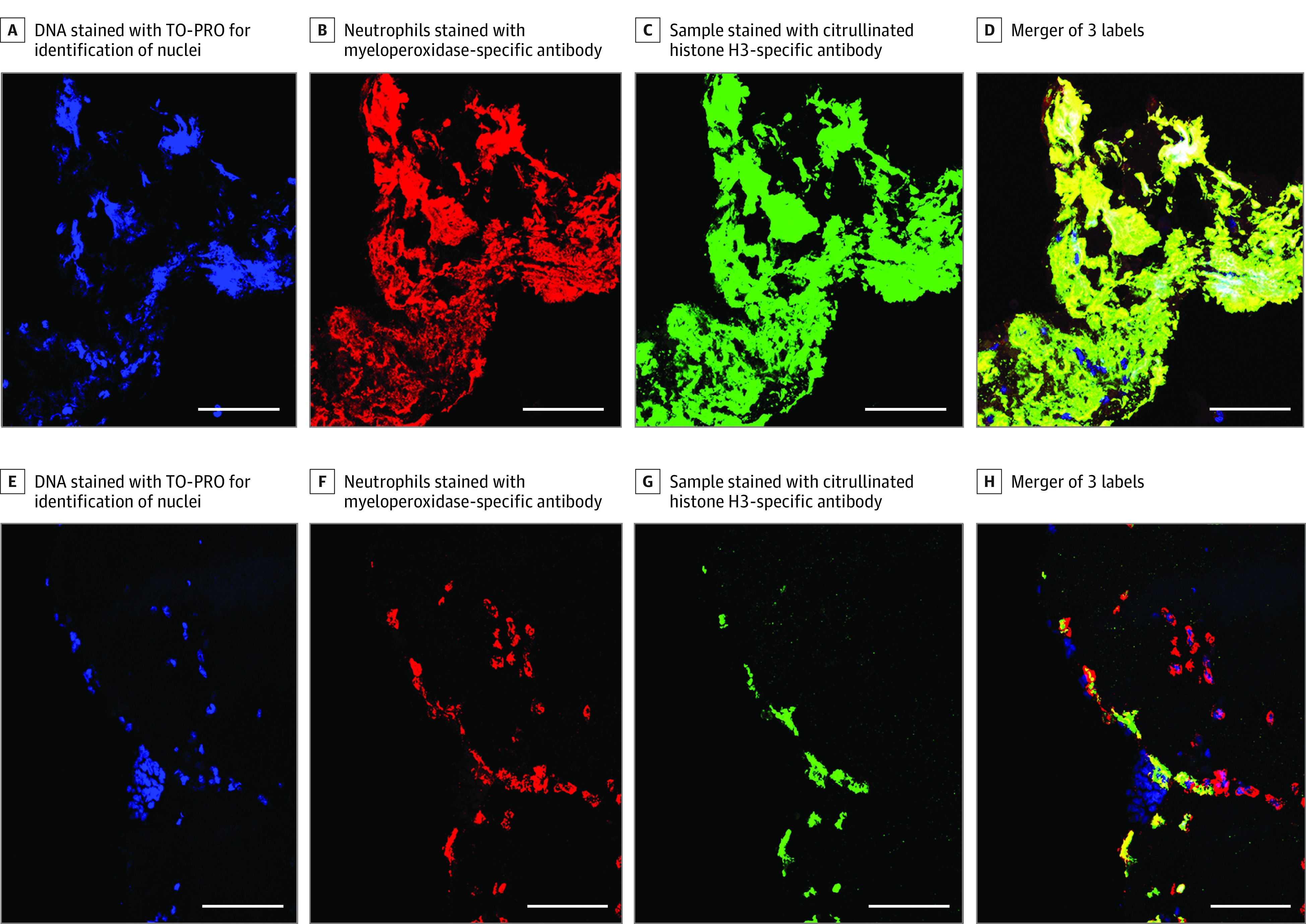

The method for the analysis of NETs in paraffin-embedded coronary thrombi has been described elsewhere.6 Briefly, it is based on the use of confocal microscopy technology and image analysis for the colocalization of myeloperoxidase-DNA complexes and citrullinated histone H3, which are hallmarks of NETs (Figure). NETs were identified as the colocalization area of both antibodies and quantified using ASF software, version 2.6.07266 (Leica), to determine the colocalization ratio in each sample by applying the Pearson correlation coefficient.

Figure. Immunofluorescence of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Thrombi Aspirated During Primary Coronary Intervention in Patients With ST-Elevated Myocardial Infarction.

A-D, Representative images of the coronary aspirate from a patient with ST-elevated myocardial infarction and coronavirus disease 2019. E-H, Representative images of coronary aspirate from a patient with ST-elevated myocardial infarction without coronavirus disease 2019. A and E, DNA stained with TO-PRO for the identification of nuclei. B and F, Neutrophils stained with myeloperoxidase-specific antibody. C and G, Sample stained with citrullinated histone H3–specific antibody. D, Merger of the 3 labels confirms the presence of extracellular traps by colocalization of myeloperoxidase and citrullinated histone H3. H, Merger of the 3 labels showing neutrophil extracellular traps to a lesser extent than in sample D. Bars represent 50 μm.

Patients

Between March 23 and April 11, 2020, 10 patients with STEMI and COVID-19 were treated with primary PCI in our hospital. In 5 of these 10 patients, intracoronary material was obtained by aspiration, and they were included in the study. For comparison purposes, a series from July 2015 to December 2015 of 50 consecutive patients with STEMI, in whom coronary thrombi were aspirated during PCI, was used.

For the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection, nasopharyngeal swabs were tested using reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (Cobas 6800 SARS-CoV-2 test [Roche Diagnostic]) as part of routine clinical care, following the manufacturer's instructions. Clinical variables, including age, sex, height, weight, and cardiovascular risk factors; procedural times, such as symptom onset–to-balloon time; and procedure-associated data (eg, target vessel, number of diseased vessels or use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa), were collected prospectively.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean and SD or median and interquartile range values for numerical variables and proportions (%) for categorical variables. The 95% CIs for medians were estimated based on the method of Mood and Graybill.7 We used χ2 or Fisher exact tests to compare proportions, and t or Mann-Whitney U tests for numerical variables. Analyses were performed using Stata version 16 (StataCorp). Any P < .05, 2 tailed, was considered significant.

Results

Among the 5 patients with COVID-19 and STEMI, 4 were men and the mean (SD) age was 62 (14) years (range, 45-80 years). In the series of 50 patients with STEMI, there were 44 men (88%) and the mean (SD) age was 58 (12) years (range, 39-84 years). A comparison of clinical, angiographic, and histological features of the 2 groups of patients is shown in Table 1. Individualized information on the 5 patients with COVID-19 and STEMI is summarized in Table 2.

Table 1. Comparison of Clinical Characteristics and Coronary Thrombus Histology in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and ST-Elevated Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) vs a Previous Series of Patients With STEMI.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| With COVID-19 (n = 5) | Without COVID-19 (n = 50) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 62 (14) | 58 (12) | .54 |

| Male | 4 (80) | 44 (88) | .51 |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 28.0 (27.3-30.1) | 27.6 (24.9-30.3) | >.99 |

| Hypertension | 4 (80) | 21 (42) | .17 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Current | 0 | 29 (58) | .02 |

| Former (>1 y) | 2 (40) | 10 (20) | |

| Nonsmoking | 3 (60) | 11 (22) | |

| Dyslipidemia | 0 | 26 (52) | .05 |

| Diabetes type 2 | 0 | 4 (8) | >.99 |

| Angiography | |||

| TIMI status pre-PCI of 0 or Ib | 3 (60) | 48 (98) | .02 |

| Culprit vessel | |||

| Right coronary artery | 4 (80) | 22 (44) | .49 |

| Circumflex coronary artery | 1 (20) | 8 (16) | |

| Other | 0 | 20 (40) | |

| Stent | 1 (20) | 45 (92) | .001 |

| Laboratory values | |||

| Troponin T, mean (SD), ng/mL | 28.0 (26.4-58.0) | 91.64 (37.0-142.0) | .20 |

| White blood cell count, median (IQR), cells/μL | 18 300 (11 500-19 400) | 11 100 (9700-14 800) | .05 |

| Platelet count, median (IQR), cells × 103/μL | 346 (322-419) | 232 (176-255) | .02 |

| C-reactive protein, mean (SD), mg/dL | 2.9 (1.9) | 2.6 (4.9) | .14 |

| Coronary thrombi analysis | |||

| NET density, median (IQR) | 61 (56-75) | 19 (12- 27) | <.001 |

| Polymorphonuclear cells at moderate or intense levels | 3 (60) | 28 (57) | >.99 |

| Fibrin, moderate or intense amount | 5 (100) | 25 (51) | .06 |

| Perls stain, positive statusc | 0 | 8 (16) | >.99 |

| Plaque fragments presentc | 0 | 26 (65) | .01 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); NET, neutrophil extracellular traps; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

SI conversion factors: To convert C-reactive protein to mg/L, multiply by 10; platelet count to cells × 109/μL, multiply by 1.0; troponin T to μg/L, multiply by 1.0; white blood cell count to cells × 109/μL, multiply by 0.001.

The P values indicate results of t, Mann-Whitney U, χ2, or Fisher exact tests comparing groups with or without COVID-19.

TIMI grade flow: 0, no perfusion; I, penetration without perfusion; II, partial perfusion; and III, complete perfusion.

Perls stain was used for the detection of iron deposits, indicative of previous episodes of plaque rupture; plaque fragments of atherosclerosis plaque were identified by the presence of foamy macrophages (CD68 positivity), endothelial cells (CD31 positivity), iron (Perls positivity), and/or calcium deposits.

Table 2. Clinical, Analytical, and Angiographic Features of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and ST-Elevated Myocardial Infarction and Histological Analysis of Their Coronary Thrombi Obtained During Primary Angioplasty.

| Characteristic | Patient No. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Medical history | |||||

| Hypertension | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Smoking history | No | No | No | Former | Former |

| Other | No | No | No | Asthma | No |

| Days of COVID-19 symptoms | 10 | 10 | 21 | 19 | 11 |

| Angiography | |||||

| TIMI status pre-PCIa | III | II | 0 | I | 0 |

| Culprit vessel | RCA | CCA | RCA | RCA | RCA |

| Coronary plaque by intravascular ultrasonography | Mild | No | No | Moderate | Mild |

| Stent | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| TIMI status post-PCI | III | II | III | III | I |

| Laboratory values | |||||

| Troponin T, ng/mL | 19.1 | 28.0 | 58.0 | 142.0 | 26.4 |

| White blood cell count, cells/μL | 11 100 | 11 500 | 18 300 | 19 400 | 21 500 |

| Lymphocyte count, cells/μL | 530 | 1540 | 1420 | 2140 | 440 |

| Platelet count, cells × 103/μL | 346 | 322 | 419 | 503 | 157 |

| D-dimer, μg/mL | 0.53 | 1.31 | 0.63 | 1.61 | 11.46 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 14.10 × 105 | NA | 16.85 × 105 | 6.18 × 105 | 9.88 × 105 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dL | 5.2 | 1.37 | 0.91 | 2.5 | 4.58 |

| In-hospital death | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Coronary thrombi analysis | |||||

| NET density, % | 60.8 | 43.1 | 56.0 | 90.7 | 74.5 |

| Polymorphonuclear cells | Intense | Mild | Moderate | Mild | Intense |

| Fibrin | Intense | Moderate | Intense | Moderate | Moderate |

| Perls stain resultb | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Plaque fragmentsc | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

Abbreviations: CCA, circumflex coronary artery; NA, not available; NET, neutrophil extracellular traps; RCA, right coronary artery; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

SI conversion factors: To convert C-reactive protein to mg/L, multiply by 10; D-dimer to nmol/L, multiply by 5.476; ferritin to μg/L, multiply by 1.0; platelet count to cells × 109/μL, multiply by 1.0; troponin T to μg/L, multiply by 1.0; white blood cell count to cells × 109/μL, multiply by 0.001.

TIMI grade flow: 0, no perfusion; I, penetration without perfusion; II, partial perfusion; III, complete perfusion.

Perls stain for the detection of iron deposits, indicative of previous episodes of plaque rupture.

Plaque fragments of atherosclerosis plaque, identified by the presence of foamy macrophages (CD68 positivity), endothelial cells (CD31 positivity), iron (Perls positivity), and/or calcium deposits.

In the present series, NETs were detected in all 5 samples from the patients with COVID-19 (Figure), and the median density of NETs was 61% (95% CI, 43%-91%). We compared these results with those obtained in the 2015 series of patients with STEMI, in which NETs were found in 34 (68%) of the thrombi extracted during primary PCI, and the median density of NETs was 19% (95% CI, 13%-22%; P < .001). A box-and-whisker plot comparing the NET density data between both groups is available in the eFigure in the Supplement.

Histologically, the thrombi from the patients with COVID-19 were mostly composed of fibrin and presented some degree of polymorphonuclear cell infiltration (mild to intense). Conversely, none of them showed fragments of atherosclerotic plaque or iron deposits indicative of previous episodes of plaque rupture. In the patients from the 2015 series, 26 of 50 thrombi (65%) contained plaque fragments.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study is the first published analysis of NETs in coronary thrombi from patients with COVID-19 and STEMI. Until now, the intrinsic mechanism of coronary occlusion in STEMI in patients with COVID-19 appears not to have been shown; our results suggest an important role of NETs in the pathogenesis of coronary thrombosis in COVID-19.

NETs are web-like structures of DNA and proteins (histones, microbicide proteins, and oxidant enzymes) released by neutrophils to ensnare pathogens; however, when not properly regulated, NETs have been shown to play a vital role in initiating and accreting inflammation and thrombosis.8 It has been shown that exaggerated NET formation in COVID-19 contributes to rapid occlusion of pulmonary microvessels and severe organ damage,9 and targeting NETs as potential drivers of COVID-19 is under investigation.10

In the present study, all patients with COVID-19 had abundant NETs in their thrombi and the burden of NETs was significantly higher than in patients with STEMI and without COVID-19 infection from the 2015 series. Regarding immunohistochemical analysis, all thrombi were composed of fibrin and polymorphonuclear cells; none of them contained atherosclerotic plaque fragments, unlike most coronary thrombi (65%) from patients with STEMI and without infection. The prevalence of plaque fragments in the historical control patients is similar to that found in a series11 of 142 patients with STEMI that was previously published by our group.

The coagulation changes associated with COVID-19 suggest the presence of a hypercoagulable state that might increase the risk of thromboembolic complications.12 The most typical findings are an increased D-dimer concentration, a relatively modest decrease in platelet count, and a prolongation of the prothrombin time.1 None of these alterations was remarkable at the time of STEMI in this series, except in 1 patient who presented a high D-dimer concentration. Even considering the small sample size, these findings would indirectly support the idea of an important role of neutrophils and NETs in coronary thrombus development in patients with COVID-19.

On the other hand, an association between NETs and unfavorable clinical outcomes after STEMI has been suggested, although NET-specific components measured peripherally have not yet thrown definite results.13 We hypothesize that the mechanism of thrombus formation mediated by NETs may contribute to the poor prognosis of patients with COVID-19 who experience a STEMI. Further research is needed to confirm these preliminary results.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the small sample size, which is dependent on the number of patients with COVID-19 and STEMI attended to in our hospital since the beginning of the pandemic who underwent PCI and thrombus aspiration. Only in the 5 patients presented here were coronary aspirates obtained for analysis. For unclear reasons, possibly associated with earlier and more extended use of anti-inflammatory treatments, this type of heart infarct with high thrombotic load has not occurred in the patients with COVID-19 infection admitted to our institution after the first epidemic outbreak. However, the differences found from patients with STEMI in the prepandemic era were marked enough to be evident even in such a small sample.

Conclusions

Our results reinforce the relevant role of NETs in the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. In our opinion, these findings support the idea that targeting intravascular NETs might be a relevant goal of treatment and a feasible way to prevent coronary thrombosis in patients with severe COVID-19.

eFigure. Boxes and whiskers plot comparing NETs density in patients with STEMI, with and without COVID-19 disease.

References

- 1.Levi M, Thachil J, Iba T, Levy JH. Coagulation abnormalities and thrombosis in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(6):e438-e440. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30145-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jiménez D, et al. ; Global COVID-19 Thrombosis Collaborative Group, Endorsed by the ISTH, NATF, ESVM, and the IUA, Supported by the ESC Working Group on Pulmonary Circulation and Right Ventricular Function . COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up, JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2950-2973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thierry AR, Roch B. Neutrophil extracellular traps and by-products play a key role in COVID-19: pathogenesis, risk factors, and therapy. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9):E2942. doi: 10.3390/jcm9092942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonow RO, Fonarow GC, O’Gara PT, Yancy CW. Association of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with myocardial injury and mortality. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):751-753. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bangalore S, Sharma A, Slotwiner A, et al. ST-segment elevation in patients with COVID-19—a case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(25):2478-2480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santos A, Martín P, Blasco A, et al. NETs detection and quantification in paraffin embedded samples using confocal microscopy. Micron. 2018;114:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2018.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mood AM, Graybill FA. Introduction to the Theory of Statistics. 2nd ed. McGraw–Hill; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuo Y, Yalavarthi S, Shi H, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) as markers of disease severity in COVID-19. MedRxiv. 2020; 2020.04.09.20059626.

- 9.Carsana L, Sonzogni A, Nasr A, et al. Pulmonary post-mortem findings in a large series of COVID-19 cases from Northern Italy: a two-centre descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;(10):1135-1140. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30434-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mozzini C, Girelli D. The role of neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID-19: only an hypothesis or a potential new field of research? Thromb Res. 2020;191:26-27. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blasco A, Bellas C, Goicolea L, et al. Immunohistological analysis of intracoronary thrombus aspirate in STEMI patients: clinical implications of pathological findings. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2017;70(3):170-177. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Xiao M, Zhang S, et al. Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(17):e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langseth MS, Ragnhild Helseth R, Ritschel V, et al. Double-stranded DNA and NETs components in relation to clinical outcome after ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Scientific Reports. 2020;10(1):5007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Boxes and whiskers plot comparing NETs density in patients with STEMI, with and without COVID-19 disease.