Abstract

Background: The development of COVID-19 pandemic has affected all segments of the population; however, it had a significant impact on vulnerable subjects, such as in people experiencing homelessness. The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of COVID-19 spread in homeless persons in the city of Rome, Italy.

Design and Methods: Patients included in the study underwent a clinical evaluation and rapid antibody analysis on capillary blood for the presence of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 virus. Symptomatic patients were not included in the screening and immediately referred to local hospitals for further evaluation.

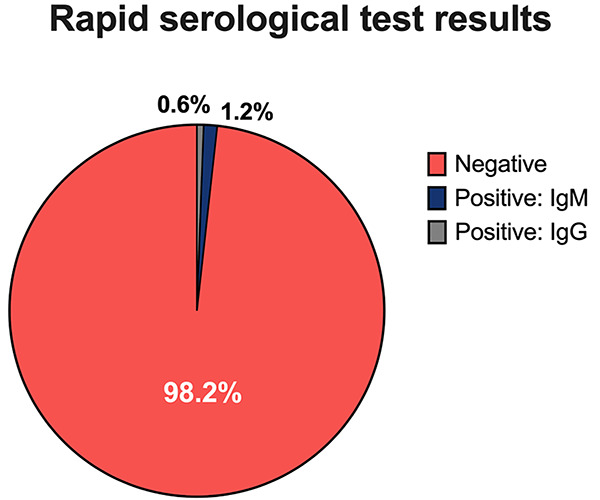

Results: One-hundred seventy-three patients of both sexes were tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection through rapid serological test. Age range was 10-80 years; people came from 35 different countries of origin and 4 continents. Test results were negative for most patients (170-98.2%); two patients had positive IgM (1.2%) and one patient had positive IgG (0.6%).

Conclusions: Our study is the first to evaluate the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in people experiencing homelessness in the city of Rome, Italy. Most patients were negative for COVID- 19, although several factors may have had an impact on this result, such as the exclusion of symptomatic patients, the limited sensitivity of rapid serological tests in the initial stage of infection and the prevention measures adopted in these populations. Larger studies on fragile populations are needed to prevent and intercept new clusters of infection in the upcoming months.

Significance for public health.

The development of COVID-19 pandemic has affected all segments of the population; however, it had a significant impact on vulnerable subjects, such as the homeless population. People experiencing homelessness live in environments that may favor contagion and infection spread; the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 among them is rarely known, and it is possible to imagine them as hidden sources of contagion that may be difficult to trace through epidemiological link studies. Furthermore, people experiencing homelessness have an all-cause mortality higher than the general population, and COVID-19 might further increase this disparity. A more detailed understanding of the characteristics and spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection among the homeless population is of utmost importance to develop public health interventions in these communities and to prevent and intercept new clusters of infection.

Key words: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, homeless population, screening, fragile populations

Introduction

The development of the recent Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic due to the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has affected all segments of the population transversely; however, the infection had a significantly worse impact on vulnerable subjects, such as homeless persons.1-4

In these specific populations the presence of the SARS-CoV- 2 virus is rarely known, and it is possible to imagine them as hidden sources of contagion that may be difficult to trace through epidemiological link studies.5-12 Furthermore, people experiencing homelessness live in congregate settings that may favor contagion and infection spread, as they share common spaces often without adequate social distancing, individual protections such as face masks may be unavailable or incorrectly worn, and in some cases, they may not fully understand rules and means of contagion as they are not correctly and routinely informed. In addition, previous research has shown that homeless persons may have physical and mental diseases that cause a mortality several times higher than the general population, and COVID-19 might further worsen this disparity.13,14

The aim of this preliminary study was to evaluate through rapid serology-based testing the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the homeless population in the city of Rome, Italy.

Design and Methods

The study was performed between April and July 2020 in homeless persons in the city of Rome, Italy, referring to two primary care services dedicated to fragile patients. The first is the Madre di Misericordia Primary Care Service of the Eleemosynaria Apostolica and its mobile healthcare facilities located in the Vatican City State serving a large cohort of fragile patients in the surrounding areas; the second is the Medicina Solidale primary care service, located in a suburban area of the city of Rome, Italy.

At admission, patients were screened for symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, such as fever >37.5°C, cough, tiredness, sore throat and breathing difficulties at the time of the admission and in the 14 days before; if positive to one of these, patients were not admitted to the service and referred to local hospitals for further evaluation.

For each patient, an internal medicine physician compiled a clinical-anamnestic record including personal data, lifestyles and living conditions, performed a basic health assessment with medical examination and vital signs measurement (body temperature measurement, blood pressure measurement, oxygen saturation measurement), and executed a rapid antibody analysis on capillary whole blood samples from the fingertip for the presence of specific antibodies, immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM), to SARS-CoV-2 virus (Biozek Medical COVID-19 Rapid Test, Inzek B.V., Apeldoorn, the Netherlands). In addition, face masks, gloves, hand hygienizing gels were distributed to patients.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki; all patients signed a written informed consent to perform the rapid serological test and participate to the study.

Results

One-hundred seventy-three patients were tested for COVID-19 through rapid serology-based tests between April 14 and July 31, 2020 in two primary care services in the city of Rome, Italy.

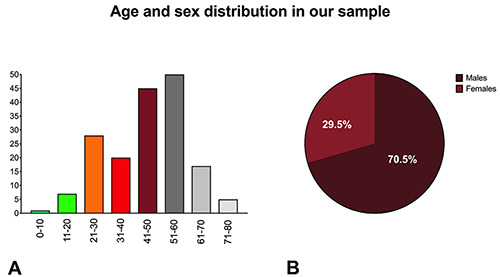

Average age was 45.6 years (age range: 10-80 years). Age distribution is shown in Figure 1A; the most common age groups were 41-50 and 51-60 years (45 and 50 patients, respectively), followed by 21-30, 31-40 and 61-70 years (28, 20 and 17 patients, respectively). The least numerous groups were 0-10, 11-20 and 71-80 years (1, 7 and 5 patients, respectively). The sample included 122 males (70.5%) and 51 females (29.5%) (Figure 1B).

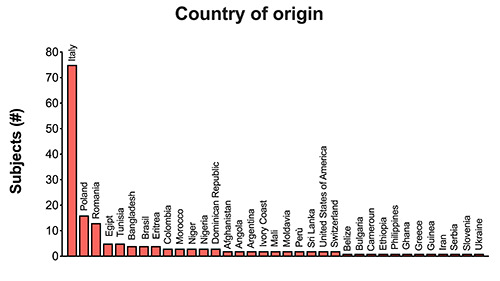

Patients had 35 different countries of origin in four continents; the most represented countries were Italy (43.3%), Poland (9.2%) and Romania (7.5%). Details are shown in Figure 2. Continent of origin was Europe for 114 patients (65.9%), followed by Africa (29 patients, 16.8%), North and South America (18 patients, 10.4%) and Asia (12 patients, 6.9%). Caucasians were the most represented in our sample.

Test results were negative for most patients (170-98.2%); two patients had positive IgM (1.2%) and one patient had positive IgG (0.6%). (Figure 3). The patients with a positive IgG or IgM test were immediately referred to the local hospital for further evaluation and for the activation of the recommended public health protocols.

Discussion

We investigated the prevalence of COVID-19 in a fragile population consisting of homeless persons in the city of Rome, Italy. Fragile populations have specific peculiarities in regard to virus transmission and disease status compared to the general population. 8 These populations usually live in settings that favor infection spread, such as shelters, encampments or abandoned buildings,4 and may not have regular access to basic hygiene supplies or showering facilities,1-3,5,6,11,13-16 thus leading to potential outbreaks as those reported in the past months by several authors.12,17-19 In addition, these persons might be more geographically mobile than the general population,1,4 making it difficult to track and prevent infection transmission.1,16 Furthermore, many homeless persons have chronic or acute comorbidities such as mental and physical conditions, 20 may engage in substance abuse,21 and have limited access to health care structures;9,22 this may worsen the impact of COVID-19 symptoms in these patients leading to a higher rate of SARS-CoV-2 morbidity and mortality.5-12

Figure 1.

Age (A) and sex (B) distribution in our sample.

Figure 2.

Details of country of origin for patients included in our study

Figure 3.

Rapid serology-based test results in our sample. Tests were negative for most patients (170-98.2%); two patients had positive IgM (1.2%) and one patient had positive IgG (0.6%).

Age and sex distribution in our sample included patients of both sexes ranging from 10 and 80 years of age. Although the more represented group was that of adult males, our sample also comprised children and elderly subjects, thus including all tiers of the population.

The large number of different countries of origin of our patients also allowed a good geographical representation of the target population. In fact, our group included people from 35 different countries in four continents. The most represented countries were Italy and other European countries, such as Poland and Romania; these countries reflect a significant portion of the homeless population in Rome.23,24 The number of African-origin people in our sample also confirm a good penetration among people with immigrant status that experience homeless condition, which in Italy is in part represented by Africans.25-27

Our data showed only two IgM positive cases and one positive IgG case among the investigated subjects. These findings may be explained by several factors. The first is that the target population was screened for symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, such as fever >37.5°C, cough, tiredness, sore throat and breathing difficulties at the time of admission or in the previous 14 days and, if positive to one of these, patients were not admitted to the service and referred to local hospitals for further evaluation. This may have prevented people with active SARS-CoV-2 infection to be included in the screening. Secondly, although rapid serological COVID- 19 tests have several advantages such as the easiness to perform and fast response, they may have a limited sensitivity, especially in the early phase of infection before seroconversion; this suggests that negative results at these tests may be unreliable to exclude recent cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection where a rapid antigen test or PCR nasopharyngeal swab would be more appropriate. Comparative studies that evaluated the rapid serological COVID- 19 tests sensitivity and specificity showed a sensitivity ranging from 30% to 96% and a specificity ranging from 96% to 98%.28-32 A Cochrane Review on 54 studies28 showed that rapid serological tests for the combination of IgG/IgM had a sensitivity of 30.1% in the period of 1 to 7 days, 72.2% 8 to 14 days, 91.4% 15 to 21 days, and 96% 21 to 35 days after symptom onset. This suggests that the sensitivity of rapid serological tests can be low in patients suspected for COVID-19 in the early period but improves in patients with at least 7 days of symptoms indicating a higher reliability for detecting previous infection if used >15 days after the onset of symptoms.28-32 In our population, this may have resulted in some false negative cases, while symptomatic patients that may have resulted positive were not included in the screening. For all these reasons, and for the recent introduction of rapid antigen tests, it is important to associate to serological antibody analysis a rapid antigen or PCR nasopharyngeal swab to identify cases in the early days of infection and avoid missing positive cases, especially if asymptomatic.

Last, but not less important, the target populations were previously educated to methods and best practices to prevent infection spread. Furthermore, face masks and hand hygienizing gels were distributed to these populations; these actions may have contributed to the prevention of infection spread and to limit the number of patients with previous infection (positive IgG).33

This study has several limits. The first is the small number of patients evaluated that may have limited the exact representation of virus diffusion among the target population. Furthermore, mental and physical comorbidities have not been investigated. Secondly, the exclusion from the screening of symptomatic patients may have affected the number of positive patients found. The third is that this study relied exclusively on rapid serological tests, while additional screening tests such as rapid antigen or PCR testing from nasopharyngeal swabs and antibody testing for the qualitative detection of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in the blood were not used and would have been more indicative of infection especially in the initial phase of the infection and in asymptomatic patients

In conclusion, our study is the first to report data on people experiencing homelessness in the city of Rome, Italy. Additional studies to evaluate the prevalence of COVID-19 infection in fragile populations, including more testing methods such as nasopharyngeal swab or quantitative analysis on peripheral blood, as well as symptomatic patients, are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of public health interventions against the spread of COVID-19 in these communities and to prevent and intercept new clusters of infection in the upcoming months.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank His Holiness Pope Francis for providing directions, structures, and equipment to make healthcare available for vulnerable populations through the Offices of Papal Charities (Eleemosynaria Apostolica), and Cardinal Konrad Krajewski, Apostolic Almoner, for the extraordinary efforts in the realization of this mission. The authors also wish to thank the Istituto di Medicina Solidale Onlus for the efforts in assisting vulnerable populations and performing screening tests; Mr. Mario Mareri and Giancarlo Trobbiani for helping in data collection; the Assessorato alla Persona, Scuola e Comunità Solidale and the Sala Operativa Sociale of the City of Rome, Italy.

Funding Statement

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Tsai J, Wilson M. COVID-19: a potential public health problem for homeless populations. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e186-e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodkin C, Mokashi V, Beal K, et al. Pandemic planning in homeless shelters: A pilot study of a COVID-19 testing and support program to mitigate the risk of COVID-19 outbreaks in congregate settings. Clin Infect Dis 2020. doi: 10.1093/ cid/ciaa743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewer D, Braithwaite I, Bullock M, et al. COVID-19 among people experiencing homelessness in England: a modelling study. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:1181-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiff R, Buccieri K, Schiff JW, et al. COVID-19 and pandemic planning in the context of rural and remote homelessness. Can J Public Health 2020. doi: 10.17269/s41997-020-00415-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albon D, Soper M, Haro A. Potential implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on the homeless population. Chest 2020;158:477-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosites E, Parker EM, Clarke KEN, et al. Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 infection prevalence in homeless shelters - Four U.S. Cities, March 27-April 15, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:521-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lima NNR, de Souza RI, Feitosa PWG, et al. People experiencing homelessness: Their potential exposure to COVID-19. Psychiatry Res 2020;288:112945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ralli M, Cedola C, Urbano S, et al. Homeless persons and migrants in precarious housing conditions and COVID-19 pandemic: peculiarities and prevention strategies. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020;24:9765-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller JP, Phillips G, Hutton J, et al. COVID-19 and emergency care for adults experiencing homelessness. Emerg Med Australas 2020;32:1084-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flook M, Grohmann S, Stagg HR. Hard to reach: COVID-19 responses and the complexities of homelessness. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:1160-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karb R, Samuels E, Vanjani R, et al. Homeless shelter characteristics and prevalence of SARS-CoV-2. West J Emerg Med 2020;21:1048-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon JC, Montgomery MP, Buff AM, et al. COVID-19 prevalence among people experiencing homelessness and homelessness service staff during early community transmission in Atlanta, Georgia, April-May 2020. Clin Infect Dis 2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbieri A. CoViD-19 in Italy: homeless population needs protection. Recenti Prog Med 2020;111:295-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grove BP, Ver C, Mohanan S. COVID-19's impact on health disparities. Am Fam Physician 2020;102:326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mesa Vieira C, Franco OH, Gomez Restrepo C, Abel T. COVID-19: The forgotten priorities of the pandemic. Maturitas 2020;136:38-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perri M, Dosani N, Hwang SW. COVID-19 and people experiencing homelessness: challenges and mitigation strategies. CMAJ 2020;192:e716-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imbert E, Kinley PM, Scarborough A, et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in a San Francisco homeless shelter. Clin Infect Dis 2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly D, Murphy H, Vadlamudi R, et al. Successful public health measures preventing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) at a Michigan homeless shelter. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2020. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tobolowsky FA, Gonzales E, Self JL, et al. COVID-19 outbreak among three affiliated homeless service sites - King County, Washington, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:523-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai J, Gelberg L, Rosenheck RA. Changes in physical health after supported housing: results from the collaborative initiative to end chronic homelessness. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34:1703-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maremmani AG, Bacciardi S, Gehring ND, et al. Substance use among homeless individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 2017;205:173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res 2000;34:1273-302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Maio G, Van den Bergh R, Garelli S, et al. Reaching out to the forgotten: providing access to medical care for the homeless in Italy. Int Health 2014;6:93-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laurenti P, Bruno S, Quaranta G, et al. Tuberculosis in sheltered homeless population of Rome: an integrated model of recruitment for risk management. ScientificWorldJournal 2012;2012:396302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atella V, Deb P, Kopinska J. Heterogeneity in long term health outcomes of migrants within Italy. J Health Econ 2019;63:19-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Meco E, Di Napoli A, Amato LM, et al. Infectious and dermatological diseases among arriving migrants on the Italian coasts. Eur J Public Health 2018;28:910-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D'Egidio V, Mipatrini D, Massetti AP, et al. How are the undocumented migrants in Rome? Assessment of quality of life and its determinants among migrant population. J Public Health (Oxf) 2017;39:440-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, Takwoingi Y, et al. Antibody tests for identification of current and past infection with SARS-CoV-2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;6:CD013652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ong DSY, de Man SJ, Lindeboom FA, Koeleman JGM. Comparison of diagnostic accuracies of rapid serological tests and ELISA to molecular diagnostics in patients with suspected coronavirus disease 2019 presenting to the hospital. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020;26:1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Elslande J, Houben E, Depypere M, et al. Diagnostic performance of seven rapid IgG/IgM antibody tests and the Euroimmun IgA/IgG ELISA in COVID-19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020;26:1082-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moura DTH, McCarty TR, Ribeiro IB, et al. Diagnostic characteristics of serological-based COVID-19 testing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2020;75:e2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lisboa Bastos M, Tavaziva G, Abidi SK, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of serological tests for covid-19: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020;370:m2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esposito S, Principi N, Leung CC, Migliori GB. Universal use of face masks for success against COVID-19: evidence and implications for prevention policies. Eur Respir J 2020;55: 2001260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]