Abstract

Objective:

There are concerns about nonscientific and/or unclear information on the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) that is available on the Internet. Furthermore, people's ability to understand health information varies and depends on their skills in reading and interpreting information. This study aims to evaluate the readability and creditability of websites with COVID-19-related information.

Methods:

The search terms “coronavirus,” “COVID,” and “COVID-19” were input into Google. The websites of the first thirty results for each search term were evaluated in terms of their credibility and readability using the Health On the Net Foundation code of conduct (HONcode) and Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL), Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG), Gunning Fog, and Flesch Reading Ease Score (FRE) scales, respectively.

Results:

The readability of COVID-19-related health information on websites was suitable for high school graduates or college students and, thus, was far above the recommended readability level. Most websites that were examined (87.2%) had not been officially certified by HONcode. There was no significant difference in the readability scores of websites with and without HONcode certification.

Conclusion:

These results suggest that organizations should improve the readability of their websites and provide information that more people can understand. This could lead to greater health literacy, less health anxiety, and the provision of better preventive information about the disease.

Saeideh Valizadeh-Haghi

INTRODUCTION

As a large family of viruses, coronaviruses are responsible for multiple diseases. In humans, these include the common cold alongside severe diseases such as Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) [1]. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was first reported in Wuhan, China, on December 31, 2019 [2]. According to a report published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in May 2020, COVID-19 spread across 216 countries very rapidly [3]. As a vaccine for this virus has yet to be developed, non-pharmacological interventions, such as increased hygiene, are crucial for controlling the virus and reducing the risk of infection [4, 5].

Many people consider the Internet to be a useful and important source of health information [6–9] that can encourage the use of preventive strategies and consultation with physicians [10]. On March 13, 2020, Google Trends reported that the term “coronavirus” was searched five million times (supplemental appendix), underlining the importance of the Internet as a source for health information. However, multiple studies demonstrate that health websites may not be credible and may contain inaccurate or misleading information [11–16]. Therefore, the information found on health websites could increase uncertainty and anxiety and, thereby, serve to harm people's health [17–19].

Trust in online health information has recently been of great concern [20] due to deficiencies in people's ability to judge the quality of this information [21, 22]. The current COVID-19 pandemic further raises concerns about nonscientific, misleading, and unclear information disseminated via the Internet or other media [23, 24], which can increase anxiety among the population. This pandemic may be particularly problematic for people with cyberchondria, defined as compulsive searching for health information online [25], because the existence of inaccurate information on the Internet could serve to increase this behavior. Apart from individuals with health anxiety, the pandemic's high mortality rate causes widespread fear, anxiety, and stress for people around the globe [26].

Although different motivations can contribute to online health information-seeking, searching for information about COVID-19 online can be understood as one way to cope with the stress associated with the pandemic [27]. For instance, people may search for information about COVID-19 to gain clarity about their own or a relative's symptoms as an attempt to alleviate uncertainty [28]. However, the fear and anxiety caused by pandemics such as COVID-19 can serve as an additional barrier to understanding information correctly [29] and may lead to further anxiety, inappropriate use of information, and unnecessary referrals to medical centers.

The proper use of health information depends on people's ability to understand, interpret, and comprehend that information [30] and can be influenced by many factors, including its readability [31]. To be considered readable, a text should be easy to read and contain concepts that are easy to understand [32]. Organizations such as the American Medical Association (AMA) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) advise that the readability of health information should not exceed a sixth-grade level [33] and should be understandable to eleven years olds [34]. Moreover, it should not use medical jargon [35]. However, online health information is often written in at a level that is not easily understood by many people [36–41].

Considering the increased use of the Internet to obtain health information on COVID-19 [42], it is of great importance to understand the readability and credibility of health websites. The objective of this study was to evaluate the readability and credibility of publicly accessible health websites containing COVID-19-related information.

METHODS

Website selection and categorization

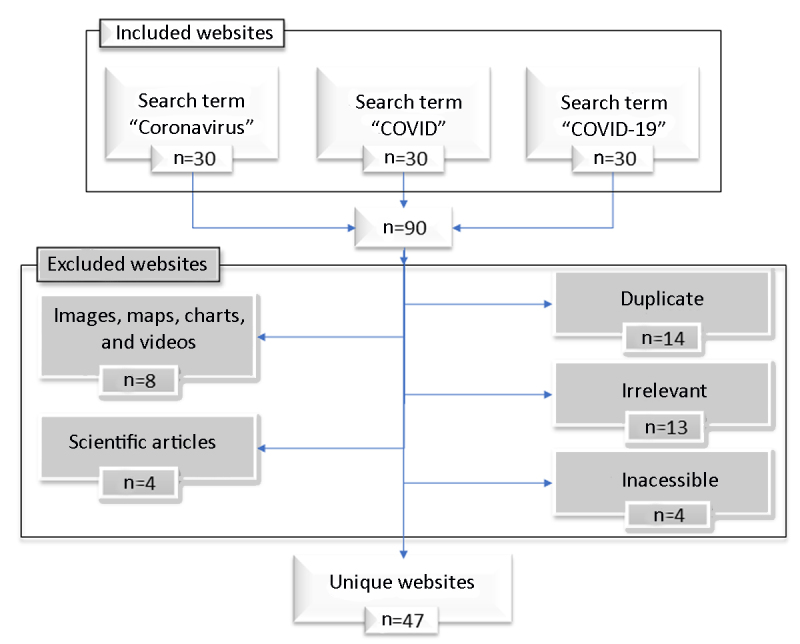

The authors searched for “coronavirus,” “COVID,” and “COVID-19” using Google, the most frequently used Internet search engine [43, 44], on February 26, 2020. The search was performed using Google Chrome, and the browser history, cached images, and cookies were removed before the searches were carried out. As 90% of all search engine users browse only the first 3 pages of results pages (i.e., the first 30 results) [45], the first 30 websites returned by Google for each of the 3 keywords were examined, resulting in a total of 90 websites.

We excluded non-English-language websites, irrelevant websites, scientific papers, duplicate websites, inaccessible websites, primarily non-text-based websites (e.g., YouTube), and advertisement-sponsored links. Based on these criteria, forty-three websites were excluded, and forty-seven unique websites were selected for evaluation (Figure 1). These websites were then divided into the following five categories according to their statement of affiliation: commercial, news, educational, governmental, and organizational.

Figure 1.

Google search flow diagram for website retrieval

Readability evaluation tools

Four readability scales, each of which uses different techniques, were used to evaluate the readability of the websites: Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL), Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG), Gunning Fog, and Flesch Reading Ease Score (FRE). These scales have been used in many readability evaluation studies of health websites on various topics and are reliable [46–53], and NIH recommends using FKGL, Gunning Fog, and SMOG for readability evaluations [54].

The FRE scale produces a score between 0 and 100, with higher scores indicating higher readability levels: scores of 90–100, 60–70, and 0–30 indicate that text can be understood by fifth-grade students, eighth- or ninth-grade students, and university graduates, respectively. The Gunning Fog scale produces scores of 5, 10, 15, or 20, which indicate that text is easy to read, hard to read, difficult to read, or very difficult to read, respectively. The SMOG and FKGL scales estimate the years of education a person needs to have completed to understand a written text; for example, a score of 7.4 indicates that a seventh-grader can understand the text. To apply these scales, a free online readability checker (Readability Formulas) was utilized [55]. This web-based tool has been used in readability evaluations of a wide variety of health-related websites [36, 46, 50, 56–59].

Credibility evaluation tool

Various tools—including JAMA [60], DISCERN [61], and Health On the Net Foundation code of conduct (HONcode) [62]—are available for evaluating the credibility of health websites. The HONcode consists of nine criteria: authority, complementarity, privacy, attribution, justifiability, transparency, financial disclosure, and advertising policy. The nonprofit HON Foundation, which is officially related to WHO, checks the credibility of websites at the request of the institutions hosting the websites. If they meet the criteria, the HON logo is placed on the website, which indicates that the website has been officially certified and is a reliable source of health information. The HON Foundation also provides a toolbar extension compatible with Chrome and Firefox browsers that helps people easily identify HONcode-certified websites while browsing [63]. HONcode is the oldest and most-used ethical and trustworthiness code for medical and health-related information available on the Internet [64]. It is reliable and has been used in multiple studies to assess the credibility of health websites [11, 12, 14–16, 65–67]. Therefore, we used the HONcode toolbar to identify certified websites containing information on COVID-19.

Statistical analysis

We tested whether HONcode-certified websites were more readable than non-HONcode-certified websites using independent t-tests. We also tested whether readability scores differed among website categories and depended on the website position on the search results pages using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 18.

RESULTS

We analyzed forty-seven unique websites containing information on COVID-19 retrieved via Google. The retrieved websites appearing on the first page of the search results included more HONcode-certified websites than those on the second and third pages (Table 1). However, even on the first page of results, most websites were not officially approved. In total, only six websites were HONcode-certified, and all were commercial and/or organizational.

Table 1.

Frequency and categorization of websites retrieved via Google

| Variables | Health On the Net Foundation code of conduct (HONcode) certified | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Search results page | |||||

| 1 | 4 | (27%) | 11 | (73%) | 15 |

| 2 | 1 | (7%) | 14 | (93%) | 15 |

| 3 | 1 | (6%) | 16 | (94%) | 17 |

| Category | |||||

| News | 0 | (—) | 14 | (100%) | 14 |

| Governmental | 0 | (—) | 18 | (100%) | 18 |

| Commercial | 2 | (40%) | 3 | (60%) | 5 |

| Organization | 4 | (44%) | 5 | (56%) | 9 |

| Educational | 0 | (—) | 1 | (100%) | 1 |

| Total | 6 | (13%) | 41 | (87%) | 47 |

ANOVA showed no significant effect of website category on readability scores (Table 2). There was also no significant effect of search results page number on readability scores (Table 3).

Table 2.

Readability scores of websites according to their category

| Reada-bility formula | Mean (SD) | p-value | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| News | Governmental | Commercial | Organizational | Educa-tional* | ||||||||||

| FRE | 51.8 | (7.2) | Fairly difficult | 44.5 | (14.1) | Difficult | 52.8 | (6.0) | Fairly difficult | 42.2 | (13.4) | Difficult | 45.5 | 0.212 |

| Gunning Fog | 12.9 | (2.2) | Hard to read | 13.4 | (2.5) | Hard to read | 12.2 | (1.2) | Hard to read | 13.9 | (2.7) | Hard to read | 14.2 | 0.687 |

| FKGL | 11.0 | (2.1) | 11th grade | 11.6 | (2.4) | 11th grade | 10.4 | (1.5) | 10th grade | 11.9 | (2.4) | 12th grade | 12.7 | 0.681 |

| SMOG | 9.9 | (1.5) | 10th grade | 10.5 | (2.0) | 10th grade | 9.4 | (0.9) | 9th grade | 10.6 | (1.9) | 10th grade | 11.4 | 0.596 |

There was only one website in this category.

SD=standard deviation, FKGL=Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, SMOG=Simple Measure of Gobbledygook, FRE=Flesch Reading Ease Score.

Table 3.

Readability scores of websites according to their search results page number

| Readability formula | Mean (SD) | p-value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | ||||||||

| FRE | 47.0 | (14.3) | Difficult | 47.7 | (7.8) | Difficult | 46.7 | (13.1) | Difficult | 0.971 |

| Gunning Fog | 13.1 | (2.5) | Hard to read | 13.3 | (2.1) | Hard to read | 13.3 | (2.5) | Hard to read | 0.949 |

| FKGL | 11.4 | (2.4) | 11th grade | 11.4 | (1.7) | 11th grade | 11.3 | (2.5) | 11th grade | 0.992 |

| SMOG | 10.1 | (2.0) | 10th grade | 10.3 | (1.3) | 10th grade | 10.3 | (2.0) | 10th grade | 0.935 |

T-tests showed no significant differences in readability scores between HONcode-certified and non-HONcode-certified websites (Table 4).

Table 4.

Readability scores of websites depending on their Health On the Net Foundation code of conduct (HONcode) certification

| Readability formula | Mean (SD) | p-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HONcode-certified | Non-HONcode-certified | |||||||

| FRE | 46.2 | (16.7) | Difficult | 47.3 | (11.2) | Difficult | 0.884 | |

| Gunning Fog | 12.8 | (3.0) | Hard to read | 13.3 | (2.2) | Hard to read | 0.648 | |

| FKGL | 11.1 | (2.9) | 11th grade | 11.4 | (2.1) | 11th grade | 0.725 | |

| SMOG | 9.8 | (2.3) | 10th grade | 10.3 | (1.7) | 10th grade | 0.541 | |

Among prominent international and national organizations, the readability of website content published by the National Health Service (NHS) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) scored highest and lowest, respectively (Table 5). The readability level of content available through the WHO and NIH websites was “difficult to read.”

Table 5.

Readability levels for websites published by prominent international and national organizations

| Organization | Grade level | Reading level | Users' age and grade level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), https://www.cdc.gov | 16 | Very difficult to read | 22 years old and older | College graduate |

| National Institutes of Health (NIH), https://www.nih.gov | 13 | Difficult to read | 18–19 years old | College level entry |

| World Health Organization (WHO), https://www.who.int | 12 | Difficult to read | 17–18 years old | 12th graders |

| European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en | 12 | Difficult to read | 17–18 years old | 12th graders |

| GOV.UK, https://www.gov.uk | 11 | Fairly difficult to read | 15–17 years old | 10th and 11th graders |

| Patient, https://patient.info | 10 | Standard/average | 14–15 years old | 9th and 10th graders |

| Healthline, https://www.healthline.com | 9 | Fairly difficult to read | 13–15 years old | 8th and 9th graders |

| Australian Government Department of Health, https://www.health.gov.au | 8 | Standard/average | 12–14 years old | 7th and 8th graders |

| New Zealand Government Ministry of Health, https://www.health.govt.nz | 8 | Standard/average | 12–14 years old | 7th and 8th graders |

| National Health Service (NHS), https://www.nhs.uk | 7 | Fairly easy to read | 11–13 years old | 6th and 7th graders |

DISCUSSION

Low literacy levels are a barrier to health knowledge. One solution to this problem is to provide content in plain language that is easy to read [68]. Using plain language can help convey information to a wider population [69] and allows users to find what they need, understand what they have found, and then use this information to meet their needs [70]. On a global level, individual reading abilities and the readability levels of consumer information contribute to the overall health of all people and society [71]. Due to the importance of readability in the context of health literacy, health promotion, and patient self-care, we evaluated the readability and credibility of COVID-19 information available on websites intended for the general public that were retrieved via Google searches.

Patient education materials should be easily understood by an average eleven-year-old or students in the sixth grade [34]. The results of this study show that the readability of COVID-19 information on websites is more advanced than the recommended level and is generally aimed at high school graduates or college students. This finding is consistent with studies examining online information on Ebola [72] and other diseases [73–75]. Moreover, our findings show that the readability level of website content published by international and national health organizations such as WHO and CDC was far above the recommended sixth-grade reading level. This is concerning because individuals consider these websites to be major sources of reliable health information, especially in health crises such as the current COVID-19 outbreak.

We also examined the readability levels of websites based on their category. Government websites were expected to be more readable than other types of websites, because their purpose is usually to educate the general public [76]. However, we found that the readability scores of websites in all categories, including governmental websites, were far above the recommended level. Although previous studies reported that governmental websites were more readable than other types of websites [73], we found that the readability of commercial websites was more suitable for a public audience than governmental websites. However, it should be noted that the information on commercial websites has been found to be of lower quality than other types of websites [77, 78]. Consequently, people looking for information on the symptoms, prevention, treatment, and management of COVID-19 may come across websites that contain readable but inaccurate information or, conversely, accurate but unreadable information, meaning that decisions based on this information could increase their anxiety and even threaten their health [17–19].

Most people tend to browse search results presented on the first page [74, 79]. Therefore, we expected that websites appearing on the first page of the search results would be more readable than those on the second and third pages. However, we found no significant difference in the mean readability scores of websites appearing on different pages of the search results. While organizations make efforts to increase the rankings of their websites in search engine results, we recommend that they also pay attention to the readability of their websites to ensure that their content can be understood. This would allow users to better understand the websites' content, satisfy their information needs, and help to prevent the spread of dangerous infectious diseases such as COVID-19.

We found that most websites that we examined were not officially certified by the HON Foundation. Therefore, individuals searching for information on COVID-19 may encounter websites that contain misinformation, which could lead to incorrect decision-making and anxiety. Moreover, both HONcode-certified and non-certified websites had poor readability scores. This finding contrasts with a similar study on prostate health, in which more credible websites were found to have better readability [80]. Therefore, we recommend that authoritative organizations providing health information about various infectious diseases, including COVID-19, pay more attention to increasing the readability of their websites to help people understand the information that is provided.

Limitations

There were some limitations in this study. For example, searches were conducted through Google Search, and using other search engines might have generated different results. In addition, due to the dynamic characteristics of websites, alternative results might have been obtained if the searches were conducted at different times.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (project no. 23640). This research has been approved by the ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (ethics code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1399.133).

SUPPLEMENTAL FILE

Appendix: Interest in coronavirus-related searches over time, based on Google trends

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: The Organization; [cited 2 Mar 2020]. <https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus>. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: The Organization; 2020. [cited 2 Mar 2020]. <https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019>. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report - 100 [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: The Organization; 29 April 2020. [cited 30 Apr 2020]. <https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200429-sitrep-100-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=bbfbf3d1_6>. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heymann DL, Shindo N. COVID-19: what is next for public health? Lancet [Internet]. 2020. February 22;395(10224):542–5. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30374-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steckelberg JM. What is MERS-CoV, and what should I do? [Internet] Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research; 2018. [cited 20 Dec 2019]. <http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sars/expert-answers/what-is-mers-cov/faq-20094747>. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choudhury SM, Arora T, Alebbi S, Ahmed L, Aden A, Omar O, Taheri S. How do Qataris source health information? PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166250 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck F, Richard JB, Nguyen-Thanh V, Montagni I, Parizot I, Renahy E. Use of the Internet as a health information resource among French young adults: results from a nationally representative survey. J Med Internet Res. 2014. May 13;16(5):e128 DOI: 10.2196/jmir.2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simou E. Health information sources: trust and satisfaction. Int J Healthc. 2015;2(1). DOI: 10.5430/ijh.v2n1p38. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alduraywish SA, Altamimi LA, Aldhuwayhi RA, AlZamil LR, Alzeghayer LY, Alsaleh FS, Aldakheel FM, Tharkar S. Sources of health information and their impacts on medical knowledge perception among the Saudi Arabian population: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2020. March 19;22(3):e14414 DOI: 10.2196/14414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atkinson NL, Saperstein SL, Pleis J. Using the Internet for health-related activities: findings from a national probability sample. J Med Internet Res. 2009. February;11(1):e4 DOI: 10.2196/jmir.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamzehei R, Ansari M, Rahmatizadeh S, Valizadeh-Haghi S. Websites as a tool for public health education: determining the trustworthiness of health websites on Ebola disease. Online J Public Health Inform. 2018. December 30;10(3):e221 DOI: 10.5210/ojphi.v10i3.9544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ansari M, Hamzehei R, Valizadeh-Haghi S. Persian language health websites on Ebola disease: less credible than you think? J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2020. December;95(1):2 DOI: 10.1186/s42506-019-0027-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritchie L, Tornari C, Patel PM, Lakhani R. Glue ear: how good is the information on the World Wide Web? J Laryngol Otol. 2016. February;130(2):157–61. DOI: 10.1017/S0022215115003230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahmatizadeh S, Valizadeh-Haghi S. Evaluating the trustworthiness of consumer-oriented health websites on diabetes. Libr Philos Pract. 2018. Spring;(1786). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rahmatizadeh S, Valizadeh-Haghi S, Kalavani A, Fakhimi N. Middle East respiratory syndrome on health information websites: how much credible they are? Libr Philos Pract. 2019. September 14;(2885). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valizadeh-Haghi S, Rahmatizadeh S. Evaluation of the quality and accessibility of available websites on kidney transplantation. Urol J. 2018. September 26;15(5):261–5. DOI: 10.22037/uj.v0i0.4252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eagle S. Diseases in a flash!: an interactive, flash-card approach 14th ed. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis; 2011. 796 p. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sokic N. Hypochondria in the age of COVID-19 [Internet] Healthing.ca; 2020. [cited 13 Mar 2020]. <https://www.healthing.ca/diseases-and-conditions/coronavirus/hypochondria-in-the-age-of-covid-19>. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Starcevic V. Cyberchondria: challenges of problematic online searches for health-related information. Psychother Psychosom [Internet]. 2017. May;86(3):129–33. DOI: 10.1159/000465525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson J, Rainie L. The future of truth and misinformation online Pew Research Center; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyer C. When the quality of health information matters: Health on the Net is the quality standard for information you can trust [Internet] Health On the Net Foundation; 2013. [cited 19 Mar 2018]. <http://www.hon.ch/Global/pdf/TrustworthyOct2006.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valizadeh-Haghi S, Moghaddasi H, Rabiei R, Asadi F. Health websites visual structure: the necessity of developing a comprehensive design guideline. Arch Adv Biosci. 2017. September 26;8(4):53–9. DOI: 10.22037/jps.v8i4.18175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nyilasy G. Fake news in the age of COVID-19. Pursuit [Internet] University of Melbourne; [cited 12 Jun 2020]. <https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/fake-news-in-the-age-of-covid-19>. [Google Scholar]

- 24. The Conversation. False information fuels fear during disease outbreaks: there is an antidote The Conversation; [Internet]. 9 February 2020. [cited 12 Jun 2020]. <https://theconversation.com/false-information-fuels-fear-during-disease-outbreaks-there-is-an-antidote-131402>. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Starcevic V, Baggio S, Berle D, Khazaal Y, Viswasam K. Cyberchondria and its relationships with related constructs: a network analysis. Psychiatr Q. 2019. September;90(3):491–505. DOI: 10.1007/s11126-019-09640-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahase E. Coronavirus: COVID-19 has killed more people than SARS and MERS combined, despite lower case fatality rate. BMJ. 2020. February 18;368:m641 DOI: 10.1136/bmj.m641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chasiotis A, Wedderhoff O, Rosman T, Mayer AK. Why do we want health information? the goals associated with health information seeking (GAINS) questionnaire. Psychol Heal. 2020. March;35(3):255–74. DOI: 10.1080/08870446.2019.1644336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khazaal Y, Chatton A, Cochand S, Hoch A, Khankarli MB, Khan R, Zullino DF. Internet use by patients with psychiatric disorders in search for general and medical informations. Psychiatr Q. 2008. December;79(4):301–9. DOI: 10.1007/s11126-008-9083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calvo MG, Carreiras M. Selective influence of test anxiety on reading processes. Br J Psychol. 1993. August;84(pt. 3):375–88. DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1993.tb02489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berland GK, Elliott MN, Morales LS, Algazy JI, Kravitz RL, Broder MS, Kanouse DE, Muñoz JA, Puyol JA, Lara M, Watkins KE, Yang H, McGlynn EA. Health information on the Internet: accessibility, quality, and readability in English and Spanish. J Am Med Assoc. 2001. May 23;285(20):2612–21. DOI: 10.1001/jama.285.20.2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. National Work Group on Literacy and Health; Weiss BD; University of Texas Health Science Center. Communicating with patients who have limited literacy skills. J Fam Pract. 1998. February;46(2):168–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albright J, de Guzman C, Acebo P, Paiva D, Faulkner M, Swanson J. Readability of patient education materials: implications for clinical practice. Appl Nurs Res. 1996. August;9(3):139–43. DOI: 10.1016/s0897-1897(96)80254-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss BD. Health literacy: a manual for clinicians [Internet] Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Foundation; 2003. [cited 6 Nov 2020]. <http://lib.ncfh.org/pdfs/6617.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cotugna N, Vickery CE, Carpenter-Haefele KM. Evaluation of literacy level of patient education pages in health-related journals. J Community Health. 2005. June;30(3):213–9. DOI: 10.1007/s10900-004-1959-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raj S, Sharma VL, Singh AJ, Goel S. Evaluation of quality and readability of health information websites identified through India's major search engines. Adv Prev Med. 2016:1–6. DOI: 10.1155/2016/4815285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Fahimuddin FZ, Sidhu S, Agrawal A. Reading level of online patient education materials from major obstetrics and gynecology societies. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. May;133(5):987–93. DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eltorai A, Ghanian S, Adams C, Born C, Daniels A. Readability of patient education materials on the American Association for Surgery of Trauma website. Arch Trauma Res. 2014. April 30;3(1):e18161 DOI: 10.5812/atr.18161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manchaiah V, Dockens AL, Flagge A, Bellon-Harn M, Azios JH, Kelly-Campbell RJ, Andersson G. Quality and readability of English-language Internet information for tinnitus. J Am Acad Audiol. 2019. January;30(1):31–40. DOI: 10.3766/jaaa.17070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vives M, Young L, Sabharwal S. Readability of spine-related patient education materials from subspecialty organization and spine practitioner websites. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009. December 1;34(25):2826–31. DOI: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b4bb0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Helitzer D, Hollis C, Cotner J, Oestreicher N. Health literacy demands of written health information materials: an assessment of cervical cancer prevention materials. Cancer Control. 2009. January;16(1):70–8. DOI: 10.1177/107327480901600111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Badarudeen S, Sabharwal S. Readability of patient education materials from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America web sites. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008. January;90(1):199–204. DOI: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Google Trends. Coronavirus [Internet] Google; 2020. [cited 13 Mar 2020]. <https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?cat=45&date=today1-m&q=%2Fm%2F01cpyy>. [Google Scholar]

- 43. StatCounter. Global stats: browser, OS, search engine including mobile usage share [Internet] Search Engine Market Share Worldwide; 2020. [cited 5 Mar 2020]. <https://gs.statcounter.com/search-engine-market-share>. [Google Scholar]

- 44. eBiz. Top 15 best search engines [Internet] eBiz MBA, eBusiness guide; September 2019. [cited 19 Oct 2019]. <http://www.ebizmba.com/articles/search-engines>. [Google Scholar]

- 45. iProspect. Blended search results study 2008 [Internet] iProspect; 2008. [cited 10 Sep 2017]. <http://www.iprospect.com>. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rayess H, Zuliani GF, Gupta A, Svider PF, Folbe AJ, Eloy JA, Carron MA. Critical analysis of the quality, readability, and technical aspects of online information provided for neck-lifts. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017. March 1;19(2):115–20. DOI: 10.1001/jamafacial.2016.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Varela-Centelles P, Ledesma-Ludi Y, Seoane-Romero JM, Seoane J. Information about oral cancer on the Internet: our patients cannot understand it. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015. April;53(4):393–5. DOI: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hadden K, Prince LY, Schnaekel A, Couch CG, Stephenson JM, Wyrick TO. Readability of patient education materials in hand surgery and health literacy best practices for improvement. J Hand Surg Am. 2016. August 1;41(8):825–32. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Royal KD, Erdmann KM. Evaluating the readability levels of medical infographic materials for public consumption. J Vis Commun Med. 2018. July 3;41(3):99–102. DOI: 10.1080/17453054.2018.1476059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alamoudi U, Hong P. Readability and quality assessment of websites related to microtia and aural atresia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015. February;79(2):151–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brigo F, Otte WM, Igwe SC, Tezzon F, Nardone R. Clearly written, easily comprehended? the readability of websites providing information on epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2015. March 1;44:35–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grewal P, Alagaratnam S. The quality and readability of colorectal cancer information on the Internet. Int J Surg. 2013;11(5):410–3. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chi E, Jabbour N, Aaronson NL. Quality and readability of websites for patient information on tonsillectomy and sleep apnea. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017. July;98:1–3. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. MedlinePlus. Choice rev online National Library of Medicine; 2006. August 1;43(12):43Sup-0363. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Readability Formulas. Contact us [Internet] My Byline Media; [cited 19 Oct 2019]. <http://www.readabilityformulas.com/contactus.php>. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maskell K, McDonald P, Paudyal P. Effectiveness of health education materials in general practice waiting rooms: a cross-sectional study. Br J Gen Pract. 2018. December;68(677):e869–76. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp18X699773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cherrez-Ojeda I, Felix M, Mata VL, Vanegas E, Gavilanes AWD, Chedraui P, Simancas-Racines D, Calderon JC, Ortiz F, Blum G, Plua A, Gonzalez G, Moscoso G, Morquecho W. Preferences of ICT among patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing hemodialysis: an Ecuadorian cross-sectional study. Healthc Inform Res. 2018. October;24(4):292–9. DOI: 10.4258/hir.2018.24.4.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ng MK, Mont MA, Piuzzi NS. Analysis of readability, quality, and content of online information available for “stem cell” injections for knee osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 2020. March;35(3):647–51.e2. DOI: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perruzza D, Jolliffe C, Butti A, McCaffrey C, Kung R, Gagnon L, Lee P. Quality and reliability of publicly accessible information on laser treatments for urinary incontinence: what is available to our patients? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. Nov-Dec 2020;27(7):1524–30. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Silberg WM, Lundberg GD, Musacchio RA. Assessing, controlling, and assuring the quality of medical information on the Internet: caveant lector et viewor—let the reader and viewer beware. JAMA. 1997. April 16;277(15):1244–5. DOI: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540390074039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Charnock D. The DISCERN handbook: quality criteria for consumer health information on treatment choices Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Radcliffe Medical Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Health on the Net Foundation. The commitment to reliable health and medical information on the Internet [Internet] The Foundation; 2017. [cited 10 Apr 2020]. <https://www.hon.ch/HONcode/Patients/Visitor/visitor.html>. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Health on the Net Foundation. HONcode toolbar [Internet] The Foundation; [cited 3 Feb 2020]. <https://www.hon.ch/en/tools.html#honcodeextension>. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Señor IC, Fernández-Alemán JL, Toval A. Are personal health records safe? a review of free web-accessible personal health record privacy policies. J Med Internet Res. 2012. August 23;14(4):e114 DOI: 10.2196/jmir.1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saraswat I, Abouassaly R, Dwyer P, Bolton DM, Lawrentschuk N. Female urinary incontinence health information quality on the Internet: a multilingual evaluation. Int Urogynecol J. 2016. January;27(1):69–76. DOI: 10.1007/s00192-015-2742-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Khazaal Y, Fernandez S, Cochand S, Reboh I, Zullino D. Quality of web-based information on social phobia: a cross-sectional study. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(5):461–5. DOI: 10.1002/da.20381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grohol JM, Slimowicz J, Granda R. The quality of mental health information commonly searched for on the Internet. Cyberpsychology Behav Soc Netw. 2014. April;17(4):216–21. DOI: 10.1089/cyber.2013.0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Quesenberry AC. Plain language for patient education. J Consum Health Internet. 2017. April 3;21(2):209–15. DOI: 10.1080/15398285.2017.1311611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Drake BF, Brown KM, Gehlert S, Wolf LE, Seo J, Perkins H, Goodman MS, Kaphingst KA. Development of plain language supplemental materials for the Biobank informed consent process. J Cancer Educ. 2017. December;32(4):836–44. DOI: 10.1007/s13187-016-1029-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. US Department of Health & Human Services. Writing for the web [Internet] The Department; 2019. [cited 9 Nov 2019]. <https://www.usability.gov/how-to-and-tools/methods/writing-for-the-web.html>. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martinez S. Consumer literacy and the readability of health education materials. Perspect Commun Disord Sci Cult Linguist Divers Popul. 2011;18(1):20–6. DOI: 10.1044/cds18.1.20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Castro-Sánchez E, Spanoudakis E, Holmes AH. Readability of Ebola information on websites of public health agencies, United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015. July;21(7):1217–9. DOI: 10.3201/eid2107.141829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mcinnes N, Haglund BJAA. Readability of online health information: implications for health literacy. Inform Health Soc Care. 2011. December 18;36(4):173–89. DOI: 10.3109/17538157.2010.542529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van Deursen AJAM, van Dijk JAGM. Using the Internet: skill related problems in users' online behavior. Interact Comput. 2009. December;21(5–6):393–402. DOI: 10.1016/j.intcom.2009.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zuchowski KA, Sanders AE. Readability and implications for health literacy: a look at online patient-oriented disease information by Alzheimer's disease research centers. Alzheimer's Dement. 2018. July 1;14(7):P1380 DOI: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.06.2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76. American Cancer Society. Cancer information on the Internet [Internet] The Society; 2016. [cited 20 Feb 2018]. <http://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-basics/cancer-information-on-the-internet.html>. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Khazaal Y, Chatton A, Cochand S, Zullino D. Quality of web-based information on cocaine addiction. Patient Educ Couns. 2008. August;72(2):336–41. DOI: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ostry A, Young ML, Hughes M. The quality of nutritional information available on popular websites: a content analysis. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(4):648–55. DOI: 10.1093/her/cym050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yi YJ, Stvilia B, Mon L. Cultural influences on seeking quality health information: an exploratory study of the Korean community. Libr Inf Sci Res. 2012. January;34(1):45–51. DOI: 10.1016/j.lisr.2011.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Koo K, Yap RL. How readable is BPH treatment information on the Internet? assessing barriers to literacy in prostate health. Am J Mens Health. 2017. March;11(2):300–7. DOI: 10.1177/1557988316680935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix: Interest in coronavirus-related searches over time, based on Google trends