Objective:

This study aimed to describe the Japanese government-led health and productivity management (HPM) strategy, specific initiatives, and success factors.

Methods:

Self-described corporation data obtained from the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry for 2014 to 2019 were analyzed descriptively.

Results:

Nationally, more than 8000 corporations participated in the HPM initiative, and performance improved each year. The range of public and private sector incentives supporting the government initiatives also increased.

Conclusions:

Success factors include matching the approach to the company's business environment, reinforcing government-led initiatives and programs, and partnering with the healthcare sector. Despite many challenges, early experience with the countrywide HPM strategy and initiatives may lead to better business outcomes and support the sustainability of Japanese society.

Keywords: aging, health and productivity management, health promotion, incentives, Japan, recognition

Maintaining the current level of economic activity and the social security system are significant issues in Japan, especially given the population decline resulting from the declining birthrate and population aging.1 In particular, ensuring a healthy workforce and the financial health of the medical insurance system are important issues confronting the government. A possible solution is extending the retirement age. In March 2020, Japan's Diet passed a law extending the obligation of corporations to continue providing employment from age 65 years to age 70 years.2 This signaled that the Japanese government is trying to secure the labor force by encouraging long-term employment by corporations. The aging of the Japanese workforce is inevitable in the near future; therefore, it is important for both corporations and society to ensure that working generations acquire healthy habits from a young age to enable them to maintain and improve their health and minimize medical expenses in older age. Therefore, investment in the health of working generations and maintaining health in the workforce will help to resolve Japan's major societal issues. However, under such circumstances and even if society understands the importance of investing in health, it is important to clarify who should pay for this investment in the health of the working generations. Although the government allocates a reasonable budget and leads the initiative, the beneficiaries are workers and corporations; this approach will be unsustainable if additional investment is not drawn from those parties. It is important that workers are supported to change their behavior, especially as they may not have sufficient understanding and motivation to improve their health. However, it is not easy to encourage such workers to invest in their own health.

In Japan, all citizens are expected to have some kind of medical insurance. Most large corporations have established health insurance associations to cover the medical treatment of workers and dependents, whereas small and medium-sized corporations tend to be members of a medical insurance association that covers the whole country. In principle, corporations and workers pay a 50/50 insurance premium, with 70% of any medical expenses incurred paid by insurance and 30% by the individual. The Occupational Safety and Health Act stipulates the obligations of employers and the roles of workers regarding healthcare for workers. That legislation requires employers to ensure that their employees undergo a general health examination each year. Additionally, medical insurance associations are required to conduct certain health promotion plans. Therefore, the government has implemented a policy aimed at guiding investment from corporations in support of their workers’ health in cooperation with medical insurance associations.

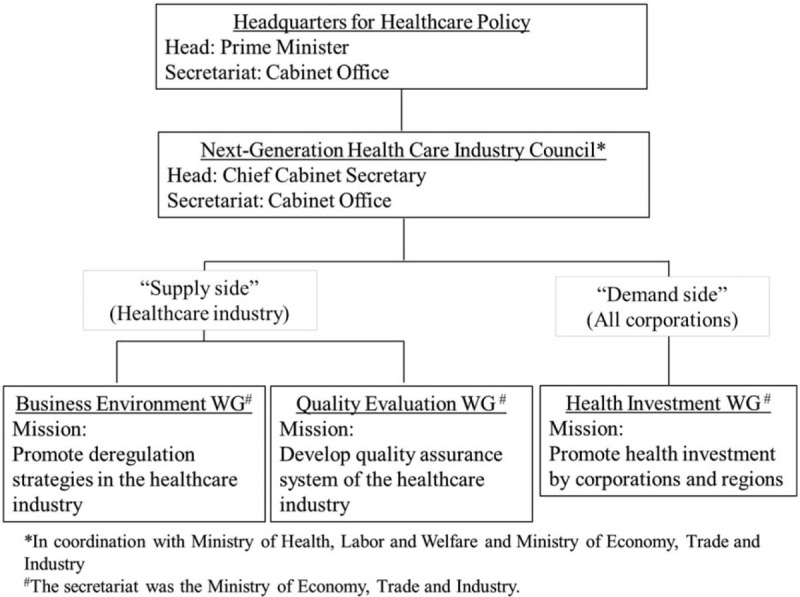

In December 2013, the Japanese Government established the Headquarters for Healthcare Policy (chaired by the Prime Minister), with the Next-Generation Healthcare Industry Council established under the auspices of the Headquarters in 2014.3 The council has three working groups (WGs) to discuss and implement specific measures. These groups are divided into two categories: (1) the Business Environment and the Quality Evaluation WGs that aim to stimulate appropriate demand for healthcare services (demand side); and (2) the Health Investment WG that aims to create a healthcare delivery sector (supply side). Figure 1 shows the organizational structure for promoting the healthcare fields as of 2014. The Japanese government's policy is characterized by working together with the healthcare industry to promote investment in the health of working generations. This is because healthcare is an important domestic industry in an aging society, and the government intends to expand the healthcare field from medical and nursing care to health promotion to foster industry participation. These efforts were led by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW).

FIGURE 1.

Japanese government organizational structure to promote health and productivity management and related fields.

Major elements to promote health and productivity management (HPM) and encourage corporations to invest in their workers’ health were discussed by the Health Investment WG, and policies were established that can be roughly divided into three groups (Table 1).4,5 The first policy group involves support for capacity building in corporations to promote HPM. A corporate “Health and Productivity Management” guidebook6 was published in 2014 to provide corporations with the necessary know-how to promote HPM. This was followed by a training program called “Advisors for HPM” that was developed and implemented in 2016. In addition, corporations that submit HPM Survey Sheets (described later in this paper) provide feedback on the results of their HPM efforts using a mechanism that allows them to understand their strengths and weaknesses based on data that have been compared with those of top corporations and averaged across related industries. The second policy group involves the establishment of recognition programs for corporations promoting HPM, and the introduction of related government and private incentives (discussed later in this paper). The third group of policies involves the formulation of “Guidebook for Disseminating Information regarding Health Management” in 20167 and “Guidelines for Health Investment Management Accounting” in 2020. These guidelines aimed to encourage corporations to disclose information regarding their efforts. In summary, the overall aims of these three policy groups included improving the competence of corporations engaged in HPM so they can achieve the desired results, and providing incentives to corporations to encourage the promotion of HPM. The policies also allow corporations to disclose their efforts in an easy-to-understand manner and communicate with stakeholders (including investors) to improve the public reputation of corporations engaged in HPM.

TABLE 1.

Major Elements of the Health and Productivity Initiatives Led by the Japanese Government

| Elements | Start Year |

| Support for capacity building in corporations to promote HPM | |

| Corporate “Health and Productivity” guidebook | 2014 |

| “HPM Survey Sheets” and feedback | 2014 |

| Training program for “Adviser for HPM” | 2016 |

| HPM recognition programs | |

| Health & Productivity Stock Selection | 2015∗ |

| Certified HPM Corporation Recognition Program | 2017† |

| Large corporation sector | |

| Small & medium-sized corporation sector | |

| Reporting support for disclosing etc | |

| Guidebook for Disseminating Information regarding Health Management | 2016 |

| Guidelines for Health Investment Management Accounting | 2020 |

The first “Health & Productivity Stock Selection” was elected in 2015 based on the HPM 2014 Survey Sheets.

The first “Certified HPM Corporation” was recognized in 2017 based on the 2016 HPM Survey Sheets.

The recognition system is gradually developing as the number of participating corporations increases. Japan has four stock markets and seven sectors, with about 3700 listed corporations. Initially, there was only the “Health & Productivity Stock Selection” program, to which only these listed corporations could apply.8 The “Certified HPM Corporation Recognition Program” was introduced in 2016, which enabled all qualified corporations (including non-listed corporations) to apply.9 The former is a system in which, in principle, one company in each industry sector with the most advanced HPM efforts is selected and awarded. The latter is a system in which corporations that meet certain requirements are certified. This system has two categories based on the number of employees: large corporations and small and medium-sized corporations. Furthermore, since 2019, a list of the top 500 HPM corporations in the large corporation sector has been published. Corporations in the Health & Productivity Stock Selection and the Certified HPM Corporation Recognition Program in the large corporation sector are evaluated using self-administered HPM Survey Sheets.5 These HPM Survey Sheets evaluate four areas: “positioning of HPM in the corporation's philosophy and policies,” “organized frameworks,” “specific systems for implementing HPM,” and “assessment and improvement.” The survey was first developed in 2014, but it has been revised each year to reflect government policy and subsequent responses of applicant corporations. Because the applicable laws/regulations and hazardous factors differ depending on the type of industry, they are not subject to evaluation and are used as negative indicators to cancel certification in the event of a legal violation or major accident.

As mentioned above, Japan has entered an era of a rapidly declining birthrate and population aging. Many other countries will face the same situation in the near future, and Japan's experience is expected to serve as a reference point for other countries. Based on the information published by the METI, we attempted to clarify the status of HPM initiatives and the level of HPM penetration in Japan. Specifically, this study had three objectives: (1) to verify the spread and quality of HPM by analyzing the characteristics and responses of applicant corporations, (2) to verify the direction of HPM policy by analyzing the contents of the HPM Survey Sheets and their trends, and (3) to verify the degree of penetration into social systems by confirming the existence of various government and private incentive systems. We also examined background factors related to the penetration of HPM in Japan and identified challenges for further development.

METHODS

Materials

This study drew on information on the applicant corporations, HPM Survey Sheets (2014 to 2019 versions), aggregated results of our analyses of the responses, and material related to the HPM initiatives published on the METI website.10

Analysis

Changes in the Number of Corporations Applying for the HPM Recognition Program and Response Trends Over Time

We used different procedures to evaluate certified HPM corporations in the large corporation sector and the small and medium-sized corporation sector. In the large corporation sector, corporations submit their HPM Survey Sheets for evaluation and then apply for the Certified HPM Recognition Program if they meet the requirements and want to be certified. In the small and medium-sized corporation sector, corporations wishing to obtain Certified HPM Recognition must submit simplified, self-checking survey sheets and meet the program requirements. We summarized the trends in the number of corporations that submitted HPM Survey Sheets and the number of corporations certified in the large corporation sector. However, we only summarized the trend in the number of certified HPM corporations in the small and medium-sized corporation sector because the application process using self-checking survey sheets was introduced in 2019.

To evaluate the trends in responses, we selected one item from each of the four survey areas. Specifically, we selected: a clear statement of the inclusion of HPM in the organization's philosophy and policies, the existence of a dedicated department for HPM in an organized framework, mental health training for employees within specific systems for implementing HPM, and verification of the effectiveness of assessment and improvement efforts. These items were selected because they were comparable from 2014 to 2019. The responses were evaluated based on the attributes of the responding corporations (number of listed corporation applicants and their share of all responding corporations, number of employees, and type of industry) as well as the selected item in each area.

Content of the HPM Survey Sheets

The HPM Survey Sheets include a section covering attributes (of both corporations and employees), an evaluation section, and a reference section. In this analysis, we targeted the evaluation section, and used reference section information to investigate the status of specific themes that might have needed evaluation the following year.

The evaluation section of the HPM Survey Sheets comprises four areas: “positioning of HPM in the organization's philosophy and policies,” “organized frameworks,” “specific systems for implementing HPM,” and “assessment and improvement” (Table 2). However, because the composition and questions differed slightly from year to year, we identified changes in the question content. There were various types of changes, such as adding new questions, deleting questions, splitting single questions into two questions, and adding or removing answer choices in relation to a question.

TABLE 2.

Outline of the Content of the HPM Survey Sheet

| Positioning of HPM in the organization's philosophy and policies |

| Documented policy for internal stakeholders |

| External information disclosure |

| Dissemination to other corporations |

| Organized frameworks |

| Management structure |

| Implementation structure |

| Cooperation with insurers such as health insurance associations |

| Specific systems for implementing HPM |

| Identifying the health issues of employees |

| Measures to be provided and range of people to be provided |

| Management of the quality of the systems used |

| Assessment and improvement |

| Existence of a Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle |

Government and Private Incentive Programs Linked to the Central Government's HPM Initiatives

We summarized the status of HPM incentive programs by classifying them into economic and non-economic government (national and local) programs and private sector programs, as of March 2020.

RESULTS

Changes in the Number of Corporations Applying for the HPM Recognition Program and Response Trends Over Time

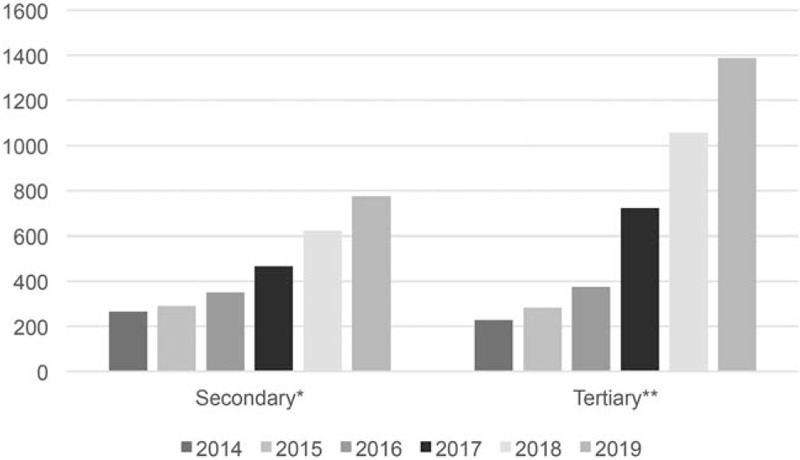

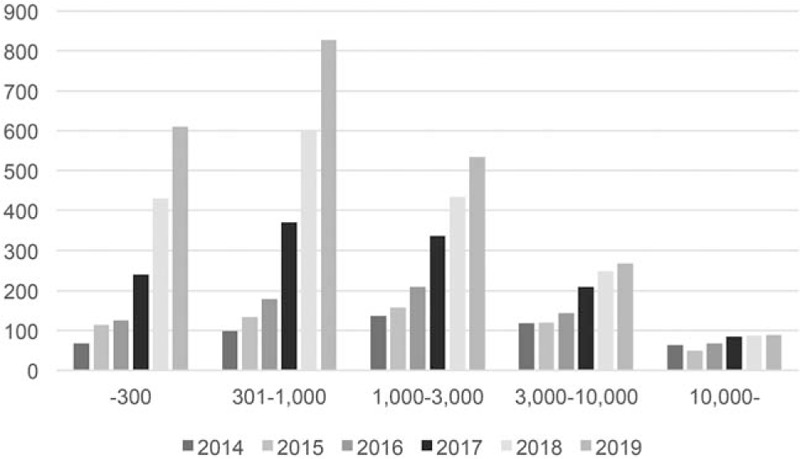

Consistent with the categories often used in Japan, we divided industries into primary industries (eg, agriculture, forestry and fisheries), secondary industries (eg, mining, manufacturing and construction industries), and tertiary industries (eg, finance, insurance, wholesale, retail, service industry, information and communication industry). The number of corporations submitting HPM Survey Sheets increased in both the secondary and tertiary industry sectors, particularly in the latter sector (Fig. 2). The primary industry sector was excluded because the number corporations submitting HPM Survey Sheets was low. In terms of the number of employees, the number of corporations with 10,000 or more employees remained steady, but the number of corporations with 301 to 1000 employees increased significantly (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 2.

Corporations applying for the HPM recognition program by industry sector and year (2014–2019). ∗Secondary industry sector includes the mining, manufacturing, and construction industries. ∗∗Tertiary industry sector includes industries such as the finance, insurance, wholesale, retail, service, and information and communication industries.

FIGURE 3.

Corporations applying for the HPM recognition program by number of employees and year (2014–2019).

Before 2016, only listed corporations were eligible to participate in the HPM survey. In 2016, the scope was expanded to include unlisted corporations. Therefore, the number of corporations participating in the survey increased, with the 2019 survey including 2328 corporations. Of the 3700 listed corporations in Japan, about 26% participated in the 2019 survey, which showed that more unlisted corporations participated than listed corporations. The number of large corporations meeting the criteria for a Certified HPM Corporation increased rapidly since the program commenced in 2016, as did the number of small and medium-sized corporations; 4816 of the 6095 corporations that applied in 2019 were certified (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

HPM Corporation Applicants and HPM Certified Corporations by Sector and Year (2014–2019)

| Large Corporation Sector | Small/Medium Corporation Sector | |||

| Year | Total Applicants | Listed Corporations (% of Total Applicants) | Certified HPM Corporation | Certified HPM Corporation (No. of Total Applicants) |

| 2014 | 493 | 493 (-) | –∗ | –∗ |

| 2015 | 573 | 573 (-) | –∗ | –∗ |

| 2016 | 726 | 610 (84.0) | 235 | 328 (-)† |

| 2017 | 1,237 | 714 (57.7) | 541 | 775 (-)† |

| 2018 | 1,800 | 859 (47.7) | 820 | 2,503 (-)† |

| 2019 | 2,328 | 964 (41.4) | 1480 | 4,816 (6,095) |

Only listed corporations were eligible for the Health & Productivity Stock Selection.

Number of applicants is not available.

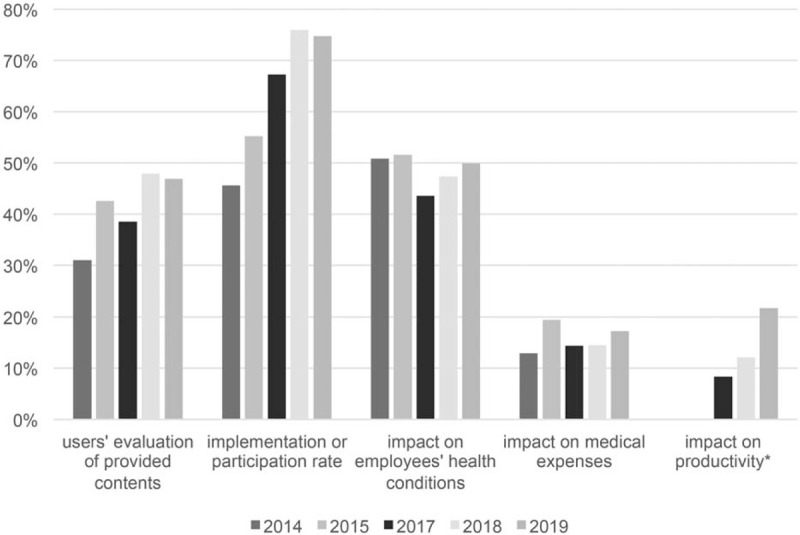

Trends in responses were confirmed using items from each area that were comparable over a 5-year period. The percentage of corporations that had implemented a clear statement of their basic policies (an indicator of the positioning of HPM in their philosophy and policies) gradually increased from 53.3% in 2014 to 88.5% in 2018, but remained unchanged at 87.9% in 2019. The number of corporations with a dedicated HPM department (an indicator of an organized framework) was almost flat, at 10.5% in 2016 when unlisted corporations were first included and 13.1% in 2015. The number of corporations implementing mental health training for employees (an indicator of specific systems for implementing HPM) was also flat between 2017 (48.3%) and 2018 (49.6%). Furthermore, the numbers of corporations verifying their program implementation or participation and that evaluated the impact on productivity also increased, although there was no change in the number of corporations evaluating the impact on health conditions or medical expenses (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Percentage of corporations reporting using HPM evaluation items by item and year (2014–2019). Note: No related items were included in the 2016 version. ∗The choice was not included in the 2014 or 2015 versions.

Content of the HPM Survey Sheets

Changes in the content of the HPM Survey Sheets are described separately under the four areas. Each area, except for “positioning of HPM in the organization's philosophy and policies”, includes some numerical indicators that were used to evaluate the degree of development and effectiveness of corporations’ HPM efforts.

Positioning of HPM in the Organization's Philosophy and Policies

This area includes items classified into three sub-categories: documented policy for internal stakeholders, external information disclosure, and dissemination to other corporations. A documented policy for internal stakeholders requires corporations to document their corporate-wide policy for HPM promotion and institute measures to promote understanding among employees. For example, one item evaluates the degree to which top management regularly communicates the organization's philosophy and policy to employees. Although some items were integrated over the study period, there were no major changes from the 2014 version.

Regarding external information disclosure, it is expected that corporations disclose the system used to promote HPM externally through media such as integrated reports based on the 2014 survey version. The item that asks about dialogue with investors regarding HPM initiatives has been positioned as an evaluation item since the 2018 version, whereas it was included as a reference item in the 2016 and 2017 versions.

In terms of dissemination to other corporations, the degree of understanding and consideration of occupational health practices when ordering products and services has been a continuous evaluation item since the 2014 version. In addition, respondents are asked whether they promote the expansion of HPM to external organizations including their corporate group, business partners, and other local corporations, and whether they make efforts to promote HPM through their business (eg, adding related content to their products and services).

Organized Frameworks

This area consists of three sub-categories: management structure, implementation structure, and cooperation with insurers (eg, health insurance associations). The management structure requires the appointment of a high-level manager as the person responsible for health management. In addition, we evaluated whether the topic of HPM had been discussed at management meetings since the 2016 version.

In terms of the implementation structure, respondents are asked whether they have a dedicated HPM department and how many occupational health experts they have. In 2017, a survey item was added regarding the involvement of labor unions and employee representatives. Regarding cooperation with insurers, the health insurance association is a system unique to Japan that forms part of the universal health insurance system and entrusts a corporation or group of corporations with independent operation under a certain level of guidance from the MHLW. Health insurance associations are obliged to offer health promotion services, and it is recommended that these be offered in partnership with corporations. The main question in this area aims to confirm what corporations and health insurance associations discussed and how often they communicated.

Specific Systems for Implementing HPM

Survey items concerning specific systems were often changed, but the basic items covered identifying employees’ health issues, measures to be provided, range of people receiving these measures, and management of the quality of the systems used.

Regarding the identification of health issues, employers in Japan have a duty to their employees to conduct periodic physical examinations.11 Since 2015, it has also been mandatory to perform stress checks to evaluate psychosocial factors.12 Therefore, the use of this information and the number of health evaluation items other than those required by law have gradually been expanded to more accurately understand the physical and mental health conditions of employees.

The measures to be provided include a range of programs, such as education to improve health literacy, measures aimed at managing employees’ working hours and work–life balance, measures designed to revitalize the workplace and prevent mental health problems, and measures to support return to work and compatibility between work and treatment for people with illnesses. These measures also include implementation of individual health guidance along with health promotion measures such as diet and exercise advice, anti-smoking measures, and infectious disease prevention measures. As noted in the Introduction, corporations tend to implement programs that are covered in the evaluation items. The government has attempted to address various policy-related issues by adding items evaluating actions, such as promotion of sport ahead of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, promotion of non-smoking programs, and measures to prevent measles and rubella epidemics. In addition, other measures related to issues such as improving symptoms associated with presenteeism and older workers were gradually added, meaning the evaluation items in the HPM Survey Sheets are increasingly comprehensive.

The main items concerning management of the quality of systems relate to the participation of professionals (eg, occupational physicians and occupational health nurses) in planning HPM and training opportunities.

Assessment and Improvement

Indicators of the level of assessment and improvement have gradually evolved as the efforts of participating corporations mature. In the 2019 version of the HPM Survey Sheets, the objectives of the business strategy were clarifying HPM implementation, identifying health problems that need to be solved to achieve those objectives, and describing specific measures to solve identified problems. The existence of a Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle was also confirmed. This confirms a series of flows related to three health issues including their basis, the year in which the issues were addressed, current status of the issues, status in the previous year, and targets for the current year and measures to address the issues to achieve these targets. This series of flows makes it possible to identify the relationships between the health issues faced by each corporation, their efforts to address these issues, and management strategies. It is also possible to confirm how a corporation evaluates their level of achievement of the objectives of their business strategy. In the 2014 and 2015 survey versions, respondents were only required to list three health issues, but the 2016 version also required a description of specific measures taken to address the issues. The 2017 version added questions on specific goals. Furthermore, as mentioned above, the 2019 edition included an evaluation of the operation of a PDCA cycle in response to these health issues.

HPM Indices

Several numerical indicators are included in the HPM Survey Sheets in relation to organized frameworks and specific systems for implementing HPM. Regarding organized frameworks, there are questions on the number of people in charge of HPM programs and their specific occupations. To evaluate specific systems for implementing HPM, there are questions on: the number of employees who were found to have high blood pressure or blood sugar levels during their health examination; the ratio of the number of employees who underwent a detailed examination to those who were identified as needing to do so based on the general health examination; proportion of employees with healthy lifestyles; and proportion of employees who were assessed as needing restricted duties based on their general health examination. The section covering measures to be provided confirms the percentage of employees who need provision of specific support services and the rate of participation in those services. In addition, there are questions on the amount of overtime worked and the time spent by workers on paid vacations, which provide indicators of the effectiveness of measures to manage working hours and achieve a work–life balance, and reduce absenteeism, presenteeism, and early retirement as a result of long-term sickness. These indicators are based on the current legal requirements in Japan and on items that do not require the collection of new information. There were no major changes from the 2014 version, so the results were comparable over time.

Government and Private Incentive Programs Linked to the Central Government's HPM Initiatives

The government (national and local) and private sector launched various economic and non-economic incentive programs linked to the HPM initiatives. Government economic incentives included programs whereby certified corporations received preferential rates for working capital loans (four prefectures and one city) and additional points in evaluation of bids for public works projects (five cities). Non-economic incentives included programs for certified HPM corporations to publicize their certification in vacancy advertisements at public recruitment offices, and enabling them to enjoy simplified procedures for extending the resident status of foreign employees, regardless of whether they were large listed corporations or small/medium-sized non-listed corporations. The original recognition program was adopted by 39 of the 47 prefectures, and city-implemented programs now exist in about 50 cities.

In addition, economic incentives offered by private sector corporations (eg, financial institutions) include preferential loans and exemptions from guarantee fees (56 cases), and four insurance premium discount systems that are offered by both non-life insurance corporations and life insurance corporations.

DISCUSSION

Implementation of HPM in Japan was conducted under the governmental policy initiatives. Corporations that introduce HPM are required to undertake programs in four areas. Furthermore, these corporations must discuss HPM at the management level to ensure that the PDCA cycle evolves and they develop better cooperation with stakeholders including employees, health insurance associations, other corporations with which they have business relationships, and investors. In addition, in the area of specific systems, it is assumed that corporations will introduce a range of programs, although the government tends to encourage corporations to address matters related to policy issues.

The increased number of corporations participating in HPM initiatives in Japan may reflect an increase in the number of corporations participating solely for the purpose of obtaining access to incentives by becoming certified, rather than for the purpose of promoting their employees’ health. Although it is not easy to analyze the quality of responding corporations’ health management practices in detail because of changes in the evaluation items over time, our results showed there was progress based on various representative items from the HPM Survey Sheets that had not changed over time. In particular, there was progress in terms of clear statements of basic policies in relation to the positioning of HPM in an organization's philosophy and policies, and in relation to assessment and improvement. Conversely, there was no change in the presence of dedicated HPM departments (an indicator of an organized framework) and the implementation of mental health training for employees, despite the inclusion of small and medium-sized corporations in the survey. These findings indicated that the average performance of participating corporations improved, along with the increase in the number of participants.

Moreover, economic and non-economic incentives offered by the public and private sectors to support HPM promotion increased. Although not considered in this study, the METI analyzed newspapers and magazines and calculated the monthly numbers of items regarding health management.5 They found that media coverage increased following the first announcement of Health & Productivity Management Stock Selection in March 2015 until February 2019, when the second phase of Certified HPM Corporation Recognition was introduced. Media coverage has been consistent since then.

As noted in the Introduction, there are various evaluation or recognition systems related to health promotion and health management in the United States and Europe.13 For example, the Fit-Friendly program is a recognition system operated by the American Heart Association since 2007, which covers 4200 worksites including small corporations.14 The Wellness Council of America, which has been operating for 30 years, has about 5000 member corporations and has operated the Wellness Workplace Award Program since 2012.15 The Health Enhancement Research Organization (HERO) provides a free online HERO scorecard, with version 4 currently used by about 1200 corporations.16 In Europe, Vitality has run the “Britain's Healthiest Workplace” (previously Britain's Healthiest Company) competition since 2013, and 510 organizations have participated.17 The number of corporations participating in government-led health management initiatives in Japan is rapidly increasing. Various public and private incentive schemes are working in tandem, and social recognition is increasing. Therefore, it is important to discuss background factors and challenges to future development.

Background to the Spread of HPM in Japan

The main factors that have led to a spread of HPM measures in Japan over a relatively short time include the fact that they fit the environment in which Japanese corporations operate and are based on government-led initiatives, as well as simultaneous action in supply side measures such as the development of the healthcare industry.

The environment in which Japanese corporations operate has seen a gradual increase in the difficulty of securing excellent human resources because of the declining birthrate and aging population.1 Therefore, hiring human resources has become a major management issue. Under these circumstances, the number of applicants for jobs advertised by exploitative corporations may drop if long working hours or regular overtime become the norm. However, small and medium-sized corporations find it increasingly difficult to hire younger people, and want skilled workers to continue working for them over the long-term. Corporations that invest in their employees’ health tend to be well regarded. In addition, large corporations cooperate with medical insurance associations, with the employer and employees sharing the costs of the premiums more or less equally. Numerous corporations have raised their insurance premiums in response to increased medical expenses and increased contributions they are required to make to the national health insurance scheme in support of older people.18 One aim of HPM is to reduce medical expenses to prevent rising insurance premiums. In addition, published reports confirmed that workers’ health problems have led to a decline in productivity.19 Therefore, the HPM initiatives are appropriate for the environment in which Japanese corporations operate.

Because the initiatives are government-led, it is conceivable that all local governments and financial institutions have aligned themselves with and led the promotion of these initiatives. Local governments operate the national health insurance scheme. Investing in corporations helps to maintain the human resources that support the economy, as well as helping residents to remain healthy after retirement. In addition, financial institutions compete to secure good customers, and corporations that invest in the health of their employees are sought after. Management and industry groups also support the development of the healthcare industry through seminars and advertising, which helps to achieve social recognition of the initiatives.

Challenges in Developing HPM in Japan

In Japan, the HPM movement is expanding as a result of its fit with the environment in which corporations operate, government-led health policies, and industry development. However, there are various challenges to its ongoing development. These challenges relate to four key aspects: improving the quality of HPM, increasing the level of penetration in small and medium-sized corporations, inducing environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investment, and improving the evaluation index used in the recognition program.

Improving the Quality of HPM

The number of applicants for the recognition program is expected to increase, which is the fundamental objective of the government's initiative. However, it is difficult to make an evaluation based on information obtained from individual surveys. Therefore, although its accuracy is limited, the evaluation is conducted via self-administered surveys. Generally, corporations that promote HPM and want to obtain certification tend to conduct activities in accordance with the survey items to obtain a better evaluation. Therefore, if we set evaluation items and add points to specific items in the HPM Survey Sheets that are consistent with government policy, corporations may be encouraged to implement programs based on that policy. For example, the main theme of the government's 2019 to 2020 action plan included the promotion of information disclosure regarding investment by corporations in employee health; therefore, the relevant items in the HPM Survey Sheets were strengthened.5 This highlights that it is necessary to continuously improve these surveys going forward.

The essence of HPM is that top management defines an organization's goals, clarifies the systems relating to employee health and work–life balance that are necessary to achieve those goals, and initiates HPM programs that aim to meet the organization's requirements while embracing the PDCA cycle. Therefore, the design of the HPM Survey Sheets was improved over recent years to allow this framework to be linked to the evaluation process. The weighting of the four key areas when selecting certified corporations has also been changed to place higher priority on evaluation and improvement. The commitment of management and the competence of the person in charge of the HPM program are important factors for setting goals that are consistent with an organization's health policy and embracing the PDCA cycle to ensure that goals are achieved. Continuous effort is necessary, including that related to human resource development.

It is important to control the quality of the services that are provided to improve the quality of HPM programs. Since corporate investment in the health of employees has become more widespread, various areas in the healthcare field have expanded.5 These include consulting, information systems, and solutions. Given that the focus is human health, these areas need to display high standards in terms of ethics and service quality. However, there have been cases where service providers have shown insufficient evidence of their effectiveness, or staff education has been insufficient. To facilitate the healthy development of the industry, the METI has encouraged the establishment of voluntary quality evaluation standards for healthcare services in each area. In addition, the METI published the “Ideal Way of Healthcare Service Guidelines” in April 201920 to create an environment that promotes continuous quality evaluation of healthcare services. It is expected that industry groups will lead the way in quality control. In addition, as numerous services related to HPM follow a “B2B2C” business model, it can be seen that the role of a person in charge of purchasing services to manage the health of employees in a corporation is challenging.

Increasing the Level of HPM Penetration in Small and Medium-Sized Corporations

It has been noted that it is not easy to provide healthcare in small and medium-sized corporations.21 Initially, the HPM initiative in Japan started with the Health & Productivity Stock Selection decree that targeted listed corporations. This resulted in the HPM initiative being criticized for only being available to large corporations. Since then, a small and medium-sized corporation sector has been established, and the number of participating corporations is growing. In addition, support programs for small and medium-sized corporations have been introduced, such as certified programs through local governments and preferential loans from regional financial institutions. However, 26% of listed large corporations that are engaged in HPM programs submitted HPM Survey Sheets, whereas only a small percentage of small and medium-sized enterprises did so.

Although small and medium-sized corporations may lack financial and human resources, top management can more easily establish a healthy culture in a relatively short period of time. For example, there have been cases where a healthy culture has taken root over several years, resulting in significant savings in employee hiring costs. Therefore, it is important to provide incentives that are directly linked to the management of small and medium-sized corporations and support personnel to assist in implementing HPM. There are also various options for incentives, such as expansion of the points system related to public procurement and tax incentives. In addition, there is a movement among life insurance companies that mainly serve small and medium-sized corporations that encourages their sales staff to qualify as HPM advisors and voluntarily support the implementation of HPM programs by their client corporations. These efforts are just beginning, and it is important to collect information on successful cases and for use in further analyses.

Inducing ESG Investment

One aim of the initiatives introduced by the METI is to create an environment in which corporations engaged in HPM are highly valued by investors as investment destinations, leading to an increase in their stock prices. Corporate activities should ensure that social contributions and profits are compatible rather than mutually exclusive. At present in Japan, many large corporations have displayed their commitment to contributing to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals outlined in the “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” adopted by the UN Summit.22 ESG investment supports these efforts from an investment perspective because it not only emphasizes traditional financial information but also considers corporate environmental, social, and governance efforts in relation to investment decision-making, and is being promoted globally as well as in Japan.23 The more ESG-friendly corporations are, the more sustainable they are and the more it is necessary to build a social environment in which those corporations can grow. It has been reported that the portfolio of Koop Award winners, which were recognized as leaders in health and productivity strategy deployment, showed three-times greater performance than the S&P 500 Index in the 14-year period from 2000 to 2014.24 It has also been noted that the stocks of corporations evaluated highly on the HPM Survey Sheets showed high performance.4

Consideration for employees is included in the social dimension of ESG investment. To consider making an investment in a corporation, it is necessary to visualize the efforts of the corporation and make comparisons with other corporations. The 2019 version of the HPM Survey Sheets included items related to dialogue with investors and was evaluated using the Health & Productivity Stock Selection. The METI published guidelines for health investment management accounting in an effort to accelerate this dialogue in 2020.5

Improving the Evaluation Index Used in the Recognition Program

If corporations seek certification in search of incentives, the evaluation indicators that are used will affect their efforts. In other words, if the HPM Survey Sheets and indicators are designed so that factors that produce good results in HPM performance can be reliably evaluated, corporations that have introduced measures based on the indicators will be able to achieve good results.

Similar to the various surveys and checklists used in the United States and Europe, the HPM Survey Sheets are based on corporate best practice and the opinions of experts. They are also revised often to reflect new evidence and policy changes. Pronk summarized the similarities and differences in relation to elements of various health promotion programs outlined in 28 publications (including academic papers, consensus reports, and books), and identified 44 items related to best practice.25 These items were divided into nine categories: leadership, relevance, partnership, comprehensiveness, implementation, engagement, communication, data driven, and compliance. A previous study26 used HERO scorecard data to examine factors in health promotion programs affecting participation in health assessments and biometric screening, the impact on medical costs, and perceptions of organizational and leadership support. That study found that organizational and leadership support was the strongest predictor of success in these areas. However, the provision of incentives only predicted increased participation, and program comprehensiveness and program integration were not significant predictors of any outcomes.

In Japan, employers are legally obliged to ensure that their employees undergo an annual general health examination; therefore, economic incentives are rarely provided at the commencement of HPM programs. However, the HPM Survey Sheets include items related to management leadership, support for managers, and support from other organizations, along with numerical indicators. By designating the current survey items as explanatory variables and using numerical indicators as outcomes, it is possible to examine which factors are associated with the required outcomes, and revise the HPM Survey Sheets and the evaluation standards that are used to select the certified corporations.

CONCLUSIONS

HPM was initiated to solve the problems faced by an aging Japanese society. It is important for every Japanese citizen to remain independent and enjoy a vibrant life as they grow older. Therefore, the consideration of employees through HPM contributes to both the sustainability of the corporation and the health of employees, even after retirement. The development of healthy Japanese corporations directly contributes to the sustainability of Japanese society, which suggests that the efforts of these corporations are fulfilling their social responsibility.

The HPM initiatives that have been promoted by the Japanese government encourage economic expansion, as they are tailored to the environment in which corporations operate and involve both local governments and private corporations. However, it will be necessary to solve various related problems to achieve the government's policy objectives and support further development.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the efforts of members of the Healthcare Industries Division of METI and related committees. We thank Geoff Whyte, MBA, and Audrey Holmes, MA, from Edanz Group (https://en-author-services.edanzgroup.com) for editing drafts of this manuscript.

Footnotes

This study was funded by research funding from the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan, and was partially supported by a Health and Labour Sciences Research Grant 2018 to 2020 (H30-Rodo-Ippan-008) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan.

KM has chaired the Health Investment Working Group since 2014. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We only used public information. No personal information was used in our analyses.

Clinical Significance: Country-wide health and productivity management initiatives is successfully implemented by matching the approach to the company's business environment, reinforcing government-led initiatives and programs, and partnering with the healthcare sector.

REFERENCES

- 1. Statistics Bureau of Japan. Statistical Handbook of Japan 2019; 2020. Available at: https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook/c0117.html. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. The Japan Times News. Japan to amend laws to help elderly work until 70; 2020. Available at: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/02/04/national/japan-amend-laws-elderly-work-until-70/#.XsjUUZVxddg. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Prime Minister's Office of Japan. Health care policy; 2017; 3. Available at: https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/kenkouiryou/en/pdf/2017_policy.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Healthcare Industries Division, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. Enhancing health and productivity management; 2020. Available at: https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/mono_info_service/healthcare/downloadfiles/180717health-and-productivity-management.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Healthcare Industries Division, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. About promotion of health and productivity management initiatives; 2020. Available at: https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/mono_info_service/healthcare/downloadfiles/180710kenkoukeiei-gaiyou.pdf. In Japanese. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Healthcare Industries Division, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. Corporate “Health and Productivity Management” Guidebook-Recommendations for Health Promotion through Cooperation and Collaboration; 2016. Available at: https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/mono_info_service/healthcare/kenko_keiei_guidebook.html. In Japanese. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Healthcare Industries Division, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. Direction of information disclosure regarding “health investment” by corporations; 2015. Available at: https://www.meti.go.jp/committee/kenkyukai/shoujo/kenko_toushi_joho/pdf/report_01_01.pdf. In Japanese. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Healthcare Industries Division, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. METI and TSE to select Health & Productivity Stock Selection; 2014. Available at: https://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2014/1027_03.html. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Healthcare Industries Division, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. Announcement of Organizations Recognized under the 2017 Certified Health and Productivity Management Organization Recognition Program; 2017. Available at: https://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2017/0221_002.html. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Healthcare Industries Division, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. Promotion of health and productivity initiatives; 2020. Available at: https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/mono_info_service/healthcare/kenko_keiei.html. In Japanese. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito N, Nagata T, Tatemichi M, Takebayashi T, Mori K. Needs survey on the priority given to periodical medical examination items among occupational physicians in Japan. J Occup Health 2018; 60:502–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawakami N, Tsutsumi A. The Stress Check Program: a new national policy for monitoring and screening psychosocial stress in the workplace in Japan. J Occup Health 2016; 58:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fonarow GC, Calitz C, Arena R, et al. Workplace wellness recognition for optimizing workplace health. A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015; 131:e480–e497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. American Heart Association. The Fit-Friendly program; 2020. Available at: https://www.heart.org/idc/groups/heart-public/@wcm/@fc/documents/downloadable/ucm_460617.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wellness Council of America. Who we are; 2020. Available at: https://www.welcoa.org/about/. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16. HERO. HERO Health and Well-being Best Practices Scorecard in collaboration with Mercer (HERO Scorecard); 2020. Available at: https://hero-health.org/hero-scorecard/. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vitality. Britain's Healthiest Corporation; 2020. Available at: https://www.vitality.co.uk/business/healthiest-workplace/. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Health and Global Policy Institute. Japan's health insurance system, Japan Health Policy NOW; 2020. Available at: http://japanhpn.org/en/section-3-1/. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagata T, Mori K, Ohtani M, et al. Total health-related costs due to absenteeism, presenteeism, and medical and pharmaceutical expenses in Japanese employers. J Occup Environ Health 2018; 60:e273–e280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Healthcare Industries Division, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. About guide for healthcare service guidelines; 2019. Available at: https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/mono_info_service/healthcare/index_2.html. In Japanese. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rantanen J. Basic occupational health services—their structure, content and objectives. Scand J Work Environ Health 2005; 1: suppl: 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- 22. United Nations. About the sustainable development goals; 2020. Available at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23. ASEAN-Japan Centre. ESG investment, towards sustainable development in ASEAN and Japan; 2019. Available at: https://www.asean.or.jp/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/ESG_web.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goetzel RZ, Fabius R, Fabius D, et al. The stock performance of C. Everett Koop Award winners compared with the Standard & Poor's 500 Index. J Occup Environ Health 2016; 58:9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pronk N. Best practice design principle of worksite health and wellness programs. ACSM's Health Fitness J 2014; 18:42–46. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grossmeier J, Castle PH, Pitts JS, et al. Workplace well-being factors that predict employee participation, health and medical cost impact, and perceived support. Am J Health Promot 2020; 27:349–358. 890117119898613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]