Abstract

Protein kinases control nearly every facet of cellular function. These key signaling nodes integrate diverse pathway inputs to regulate complex physiological processes, and aberrant kinase signaling is linked to numerous pathologies. While fluorescent protein-based biosensors have revolutionized the study of kinase signaling by allowing direct, spatiotemporally precise kinase activity measurements in living cells, powerful new molecular tools capable of robustly tracking kinase activity dynamics across diverse experimental contexts are needed to fully dissect the role of kinase signaling in physiology and disease. Here, we report the development of an ultrasensitive, second-generation excitation-ratiometric protein kinase A (PKA) activity reporter (ExRai-AKAR2), obtained via high-throughput linker library screening, that enables sensitive and rapid monitoring of live-cell PKA activity across multiple fluorescence detection modalities, including plate reading, cell sorting and one- or two-photon imaging. Notably, in vivo visual cortex imaging in awake mice reveals highly dynamic neuronal PKA activity rapidly recruited by forced locomotion.

Reporting Summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Fluorescent protein (FP)-based kinase activity biosensors are powerful tools for probing the spatiotemporal dynamics of signaling pathways in living cells1. Kinase activity imaging is increasingly being used to unravel the molecular regulation of protein kinase A (PKA), a prototypical kinase that integrates multiple pathways to orchestrate diverse physiological processes. In particular, recent efforts have focused extensively on the brain2–9, where PKA activity is tightly controlled by neuromodulatory signaling10 and plays a key role in regulating synaptic plasticity and neuronal excitability. Yet most currently available kinase biosensor designs offer limited sensitivity that greatly restricts their reliable application in physiologically relevant in vivo systems or experimentally versatile high-content detection modalities. We recently developed an excitation-ratiometric PKA activity reporter (ExRai-AKAR), which uses a PKA substrate peptide and phosphoamino acid-binding forkhead-associated 1 (FHA1) domain to modulate the peak excitation wavelength of cpEGFP in response to phosphorylation by PKA in living cells11 (Supplementary Fig. 1a). At the time, ExRai-AKAR had already proved to be the most sensitive kinase biosensor reported so far, exhibiting a twofold or better dynamic range than previous best-in-class reporters such as AKAR4 (ref. 12), AKAR3-EV13 and tAKARα (ref. 5) (see Supplementary Table 1), enabling the visualization of subtle changes in PKA activity. Despite this advance, however, the performance of ExRai-AKAR still falls short of past efforts that have successfully extended the application of fluorescent biosensor-based imaging beyond the petri dish14. Here, we report the development of an optimized, second-generation excitation-ratiometric PKA sensor, ExRai-AKAR2, that offers several-fold improvements in dynamic range, signal-to-noise ratio and sensitivity.

Results

Development and characterization of ExRai-AKAR2.

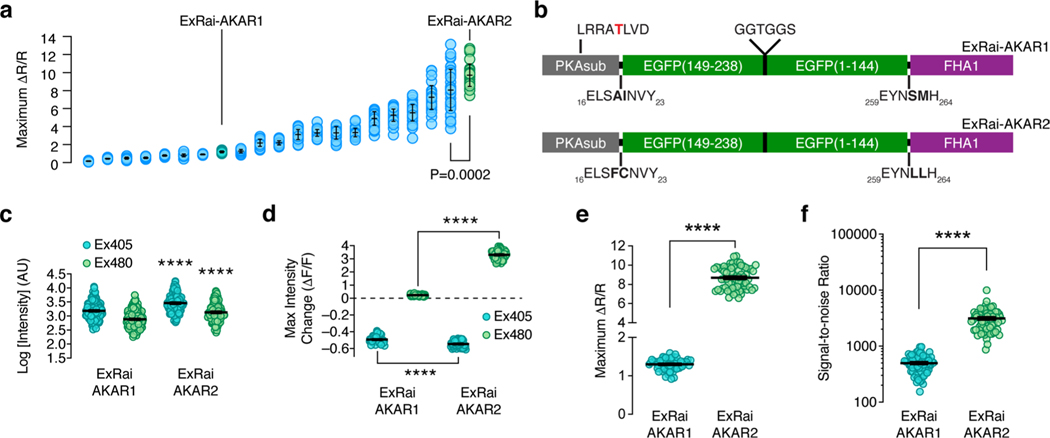

Given the well-known importance of linker sequences in influencing biosensor performance15–17, we set out to further enhance ExRai-AKAR by generating a randomized library in which the pairs of residues at positions 19/20 and 271/272, which correspond to the sites immediately preceding and following cpEGFP, were replaced with any amino acid (Supplementary Fig. 1b). To help identify variants with the potential for very large excitation-ratio changes, we first screened ~ 19,000 transformed Escherichia coli colonies for bright fluorescence at 380 nm and dim fluorescence at 480 nm, and selected 369 clones for in vitro determination of maximum fluorescence (ΔF/F) and ratio (ΔR/R) changes after phosphorylation by PKA (see Methods) (Supplementary Fig. 1c). We then tested 20 top responders alongside the original ExRai-AKAR in HeLa cells stimulated with Fsk and 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) to induce maximal PKA activity (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Despite incomplete agreement with the in vitro results across the panel, a single clone with the linker pair FC-LL was found to exhibit the best performance under both conditions (ratio change (ΔR/R), 11.9 and 9.7 ± 0.23; mean ± s.e.m., n = 30 cells) and was designated ExRai-AKAR2 (Extended Data Fig. 1b).

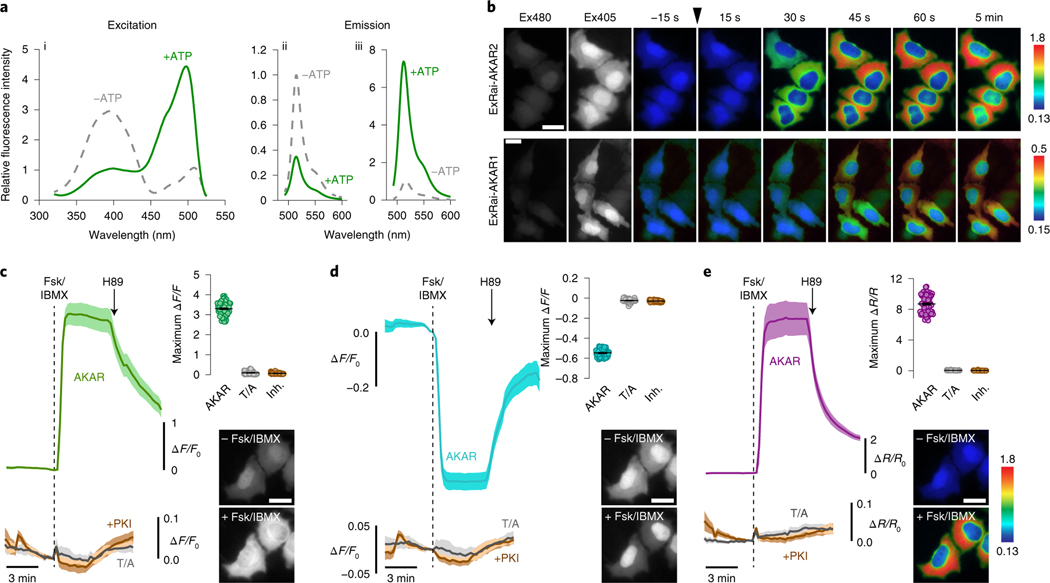

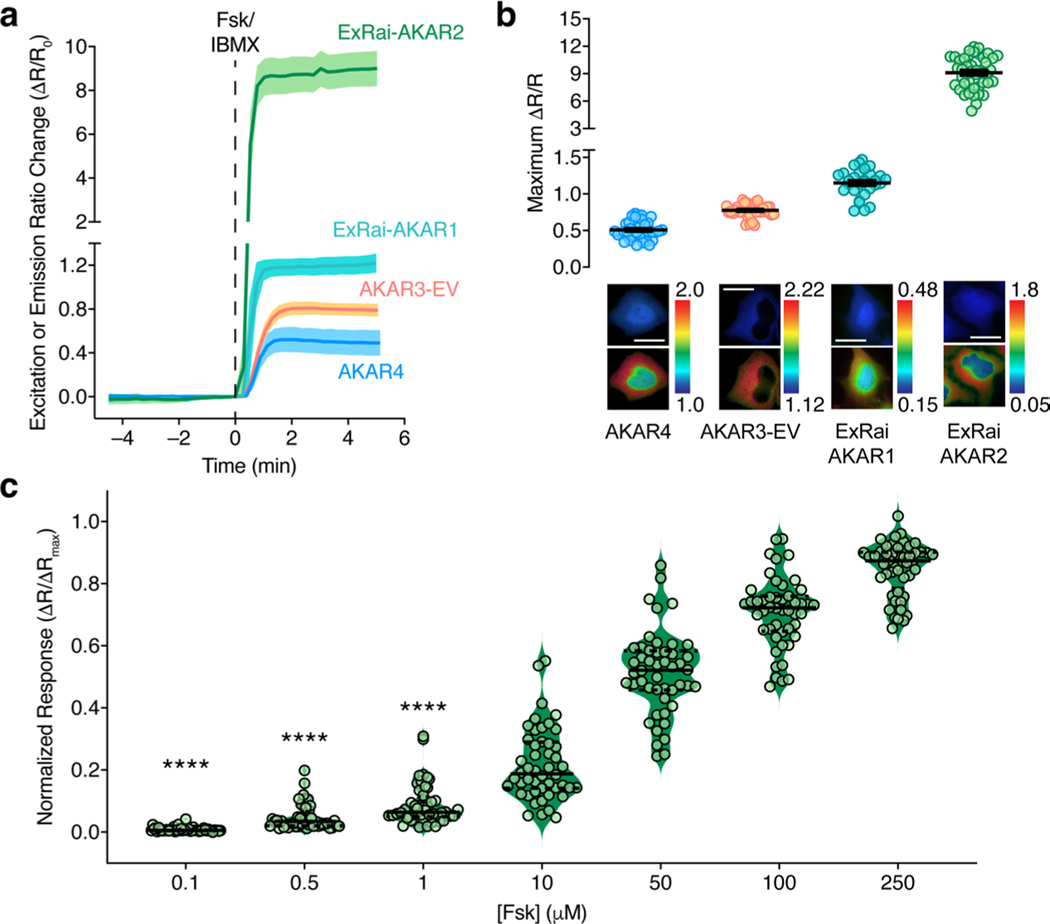

Purified ExRai-AKAR2 displayed two in vitro excitation maxima at approximately 400 and 500 nm, which decreased by 65% and increased by 417%, respectively, on coincubation with purified PKA catalytic subunit and ATP (Fig. 1a). In HeLa cells, ExRai-AKAR2 was modestly but significantly brighter compared with ExRai-AKARl, showing 76 and 87% greater fluorescence intensity at 480- and 405-nm excitation, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 1c,d). PKA stimulation further induced rapid and reversible fluorescence changes in HeLa cells expressing ExRai-AKAR2 (Fig. 1b–e, Extended Data Fig. 1e and Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3), yielding a 330 ± 4% (maximum ΔF/F, 395%; n = 70) intensity increase at 480-nm excitation, a 54.7 ± 0.4% (maximum ΔF/F, −61.1%; n = 70) intensity decrease at 405-nm excitation and an 869 ± 13% (maximum ΔR/R, 1,095%; n = 70) excitation-ratio increase in the cytosol. On the other hand, neither cells expressing a negative-control ExRai-AKAR2 construct with a mutated phospho-acceptor site (T/A), nor cells cotransfected with the potent and selective inhibitor PKI, showed any response to PKA stimulation (Fig. 1c–e and Supplementary Fig. 2). ExRai-AKAR2 clearly outperformed existing PKA sensors imaged under similar conditions (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1), including showing a sevenfold greater ΔR/R (869 ± 13% versus 130 ± 2%, P< 0.0001) and sixfold higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR, 3,121 ± 168 versus 498 ± 22, P < 0.0001) versus ExRai-AKAR1 (Extended Data Fig. 1e,f). ExRai-AKAR2 also responded to lower doses of Fsk than previously reported for ExRai-AKAR1 (ref. 11) (Extended Data Fig. 2c), suggesting ExRai-AKAR2 shows enhanced sensitivity.

Fig. 1 |. Identification and characterization of ExRai-AKAR2.

a, Representative ExRai-AKAR2 fluorescence spectra collected at 530 nm emission (i) and 400 nm (ii) or 480 nm excitation (iii) without (gray traces) or with (green traces) ATP in the presence of PKA catalytic subunit. n = 3 independent experiments. b, Representative pseudocolored images showing the responses of ExRai-AKAR2 and ExRai-AKAR1 to Fsk/IBMX stimulation in HeLa cells. Excitation at 480 nm (Ex480) and at 405 nm (Ex405) images to the left show probe fluorescence at the beginning of the experiment. The arrowhead indicates the time when drug was added. Images are representative of three independent experiments for each sensor. c–e, Average timecourses (left) and maximum Ex480 (c), Ex405 (d) or 480/405 ratio responses (e) (right, top) in HeLa cells expressing ExRai-AKAR2 (AKAR, green, teal or purple curve; n = 70 cells), a negative-control phospho-acceptor mutant (T/A, gray curves; n = 59 cells) or ExRai-AKAR2 plus a PKA inhibitor construct (+PKI, brown curves; n = 51 cells) and treated with 50 μM Fsk/100 μM IBMX (Fsk/IBMX). Timecourses are representative of and maximum responses are combined from three independent experiments. Solid lines indicate mean responses; shaded areas, s.d. Images show ExRai-AKAR2 Ex480 (c), Ex405 fluorescence (d) or 480/405 nm excitation ratio (e) (pseudocolored) before and after stimulation. Warmer colors in b and e indicate higher ratios. All scale bars, 10 μm.

Robust detection of local PKA activity using ExRai-AKAR2.

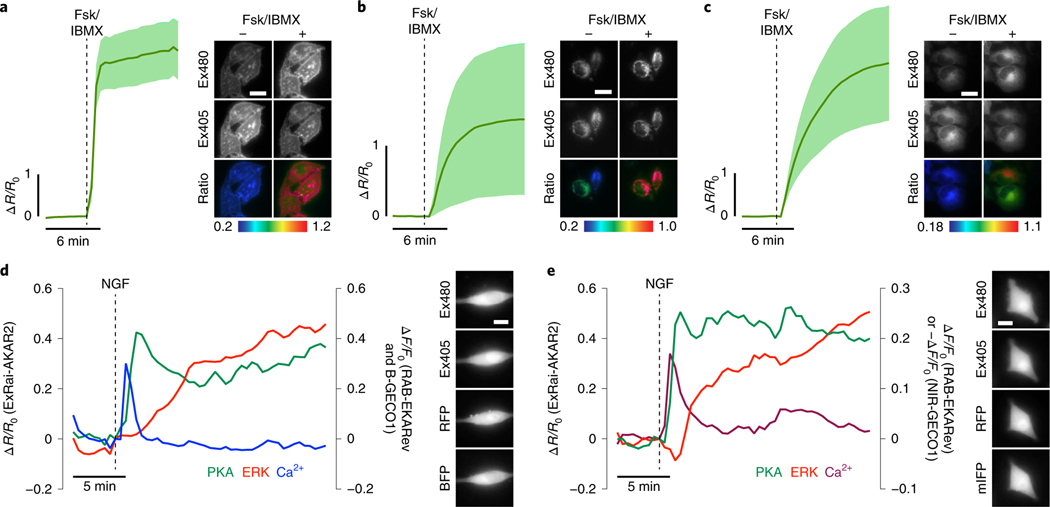

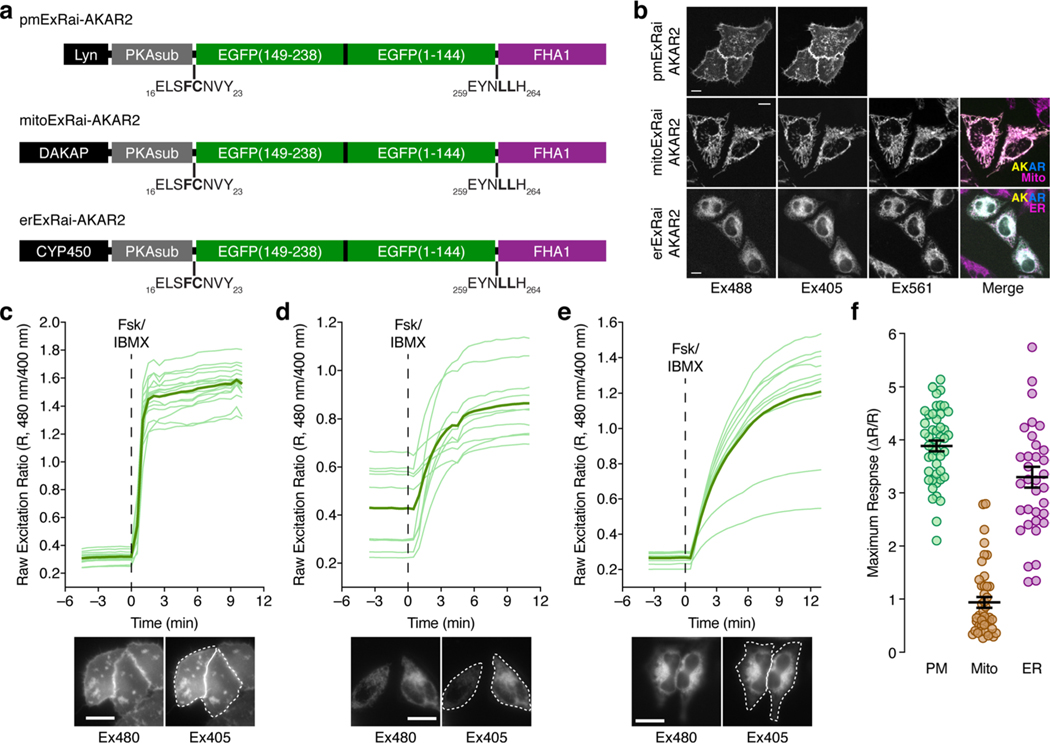

PKA activity is highly compartmentalized through both the localized production/degradation of cAMP and the recruitment of the PKA holoenzyme to subcellular structures via A-kinase anchoring proteins18,19. Biosensor targeting through the incorporation of different localization tags is a frequently used strategy for enabling the selective visualization of local signaling activity in different subcellular compartments20, yet subcellular targeting often reduces biosensor dynamic range21 to the extent that reliably tracking subcellular signaling events becomes challenging. We therefore tested the ability of ExRai-AKAR2 to report subcellular PKA activity dynamics and found that ExRai-AKAR2 can still display relatively high sensitivity when targeted (Fig. 2a–c and Extended Data Fig. 3). Subcellularly targeted variants of ExRai-AKAR2 exhibited average dynamic ranges of 389 ± 10% (maximum ΔR/R, 514%; n = 46) and 330 ± 20% (maximum ΔR/R, 647%; n = 35) when localized to the plasma membrane and endoplasmic reticulum membrane, respectively, in HeLa cells (Fig. 2a–c and Extended Data Fig. 3). A lower, yet still robust stimulated response (93.7 ± 10.1%, maximum ΔR/R, 280%; n = 43) was observed from ExRai-AKAR2 targeted to the outer mitochondrial membrane. This reduced dynamic range may truly reflect a lower level of PKA activity at this location22, likely influenced by the local balance between PKA and phosphatase activities, although some direct perturbation of the biosensor response caused by the targeting motif itself cannot be excluded.

Fig. 2 |. Subcellular kinase activity detection and multiplexed imaging using ExRai-AKAR2.

a-c, Live-cell timecourses of 480/405 nm excitation-ratio responses from plasma membrane- (a), outer mitochondrial membrane- (b) or endoplasmic reticulum-targeted ExRai-AKAR2 in HeLa cells (c) stimulated with 50μM Fsk and 100μM IBMX (Fsk/IBMX). n = 15 (pmExRai-AKAR2), 14 (mitoExRai-AKAR2) and 17 cells (erExRai-AKAR2) and are representative of three, four and three independent experiments, respectively. Solid lines indicate mean responses; shaded areas, s.d. Images show the Ex480 and Ex405 intensity, as well as the 480/405nm excitation ratio (pseudocolored), before and after stimulation (see also Extended Data Fig. 3). d,e, Representative single-cell traces showing three-color multiplexed imaging of PKA, ERK and Ca2+ dynamics using ExRai-AKAR2 (green trace), RAB-EKARev (red trace) and either B-GECO1 (d) (blue trace) or NIR-GECO1 (e) (magenta trace) in PC12 cells stimulated with 200 ngml−1 of NGF. Curves are representative of eight cells from eight experiments for each combination. Representative images of each channel are shown to the right. Traces from additional cells are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4 and 5. Scale bars in a-e, 10 μm.

Multiplexed imaging of growth-factor-stimulated signaling.

As a key signaling hub, PKA regulates and engages in frequent cross-talk with multiple signaling pathways to direct cellular behavior, and fully elucidating this dynamic interplay requires imaging multiple sensors simultaneously11. We thus took advantage of the single emission wavelength of ExRai-AKAR2 to directly investigate the coordination of growth-factor-induced PKA, extracellular signal-related protein kinase (ERK) and Ca2+ signaling dynamics via multiplexed imaging. In PC12 cells coexpressing ExRai-AKAR2, the red-fluorescent ERK sensor RAB-EKARev23 and either the blue or near-infrared fluorescent Ca2+ sensor B-GECO1 (ref. 24) (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 4) or NIR-GECO1 (ref. 25) (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 5), treatment with nerve growth factor (NGF) induced a rapid and transient intracellular Ca2+ increase, followed by sustained increases in ERK and PKA activities (Fig. 2d,e and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). Notably, the rise in ERK activity typically lagged the Ca2+ transient by several minutes, whereas PKA activity was often triggered almost immediately by elevated Ca2+ levels and always preceded ERK activation, suggesting a specific temporal coordination between PKA and ERK that is consistent with the role of PKA in regulating ERK in this system26.

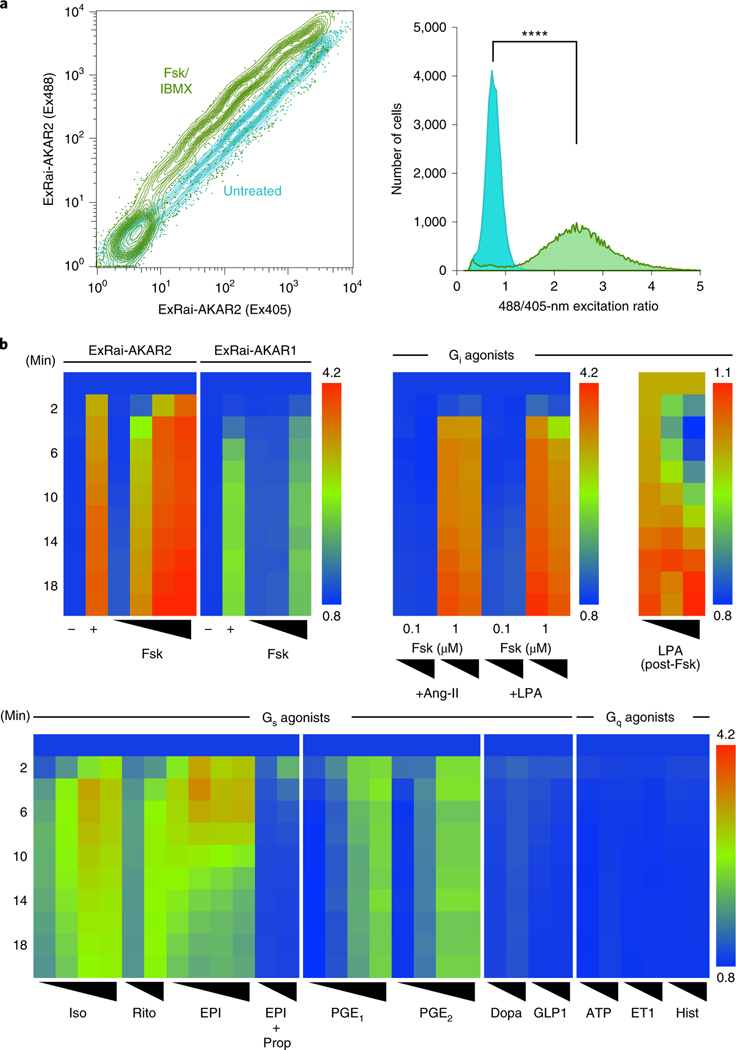

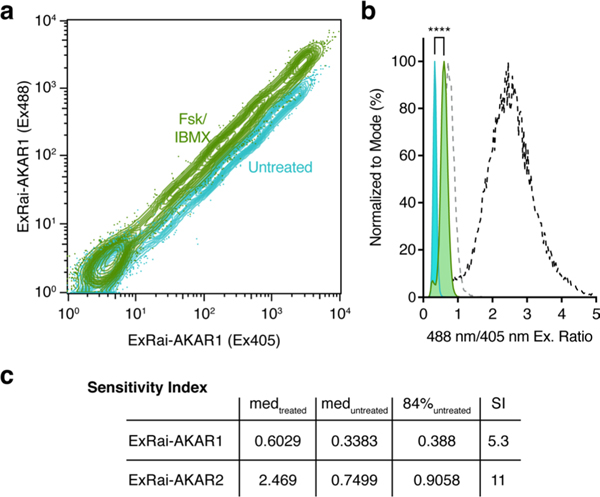

ExRai-AKAR2 supports high-throughput detection modalities.

With its greatly improved sensitivity, we expect ExRai-AKAR2 to permit robust monitoring of live-cell PKA activity regardless of the detection modality. Indeed, ExRai-AKAR2 exhibited twofold higher sensitivity compared with ExRai-AKAR1 in human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells subjected to fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) following Fsk/IBMX stimulation (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 6). ExRai-AKAR2 also showed higher dynamic range and sensitivity, as well as faster response kinetics, than ExRai-AKAR1 when we measured the response on a fluorescence plate reader (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 7), consistent with our single-cell imaging data. Thus, given the role of PKA as an integrator of multiple G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling pathways3,5,27, ExRai-AKAR2 may provide a sensitive readout for high-throughput identification of new GPCR modulators. As a proof of concept, we screened ExRai-AKAR2-expressing HEK293T cells against a series of GPCR agonists in 96-well plates (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8). ExRai-AKAR2 responded strongly to several Gαs agonists, capturing dose-dependent activity variations, as well as important temporal dynamics. We also detected dose-dependent suppression of Fsk-stimulated activity in response to Gαi agonists. On the other hand, no obvious PKA activity was detected in response to treatment with Gαs agonists whose cognate receptors are not expressed in HEK293T cells, or from Gαq-coupled agonists (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 8).

Fig. 3 |. ExRai-AKAR2 permits robust, multi-modal detection of live-cell PKA activity.

a, Flow cytometric measurement of PKA activity in HEK293T cells using ExRai-AKAR2. Left, contour plot showing 488- and 405-nm-excited fluorescence intensities of transfected cells without (teal) and with (green) Fsk/IBMX stimulation. Right, frequency distribution of 488/405 nm excitation ratio illustrating the significant population shift caused by stimulation (****P< 0.0001, two-tailed Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). Data are representative of three independent experiments. See also Extended Data Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 6. b, Heatmap showing excitation-ratio timecourses recorded on a fluorescence plate reader in HEK293T cells expressing ExRai-AKAR2 or ExRai-AKARI as indicated. Upper left, ExRai-AKAR2 versus ExRai-AKARI: untreated (–); 50 μM Fsk plus 100 μM IBMX (+); Fsk dose series (10 nM, 100 nM, 1 μM, 15 μM for ExRai-AKAR2 and 100 nM, 1 μM, 15 μM for ExRai-AKARI). Upper right, ExRai-AKAR2 with Gi-coupled receptor agonists: Fsk (100 nM, 1 μM) costimulation with angiotensin II (Ang-II; 1 μM, 10 μM) or LPA (50 nM, 500 nM); LPA dose series (control, 50 nM, 1 μM following 100 nM Fsk for 20 min). Bottom, ExRai-AKAR2 with Gs- or Gq-coupled receptor agonists: Iso (5 nM, 10 nM, 20 nM, 50 nM); epinephrine (EPI) (100 nM, 500 nM, 1 μM, 10 μM); EPI (1 μM, 10 μM) with propranolol (Prop) (10 μM) costimulation; ritodrine (Rito) (1 μM, 10 μM); PGE1 (1 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM, 1 μM); PGE2 (1 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM, 1 μM); dopamine (Dopa) (1 μM, 10 μM); glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1) (10 nM, 20 nM); ATP (1 μM, 10 μM); endothelin 1 (ET1) (30 nM, 100 nM) and histamine (Hist) (1 μM, 10 μM). Warmer colors represent higher ratios/PKA activity. Data are averaged from three independent experiments (see also Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8).

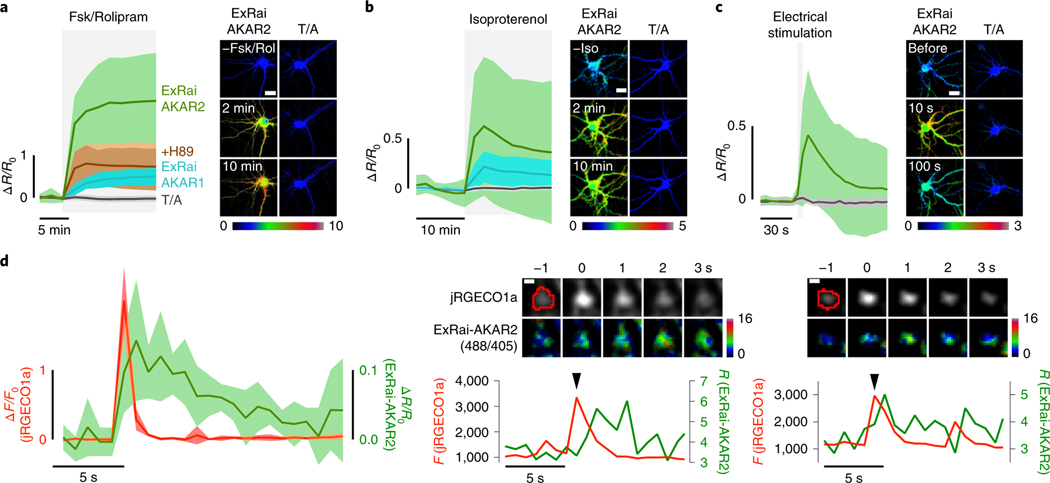

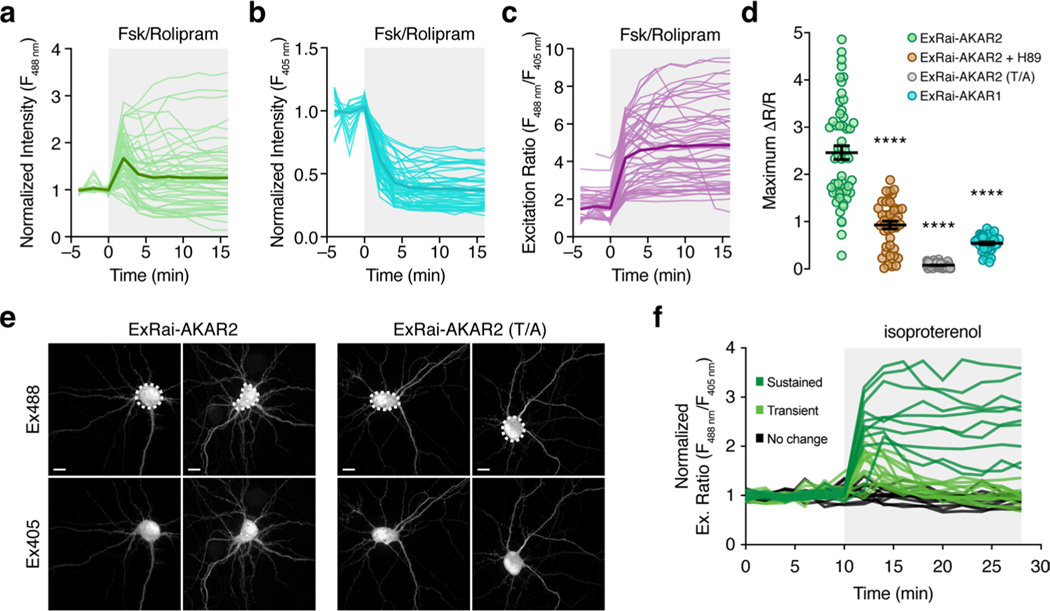

Imaging PKA activity in primary cells using ExRai-AKAR2.

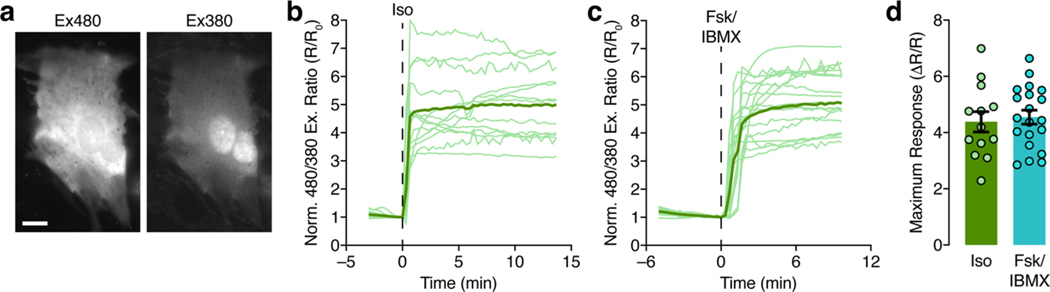

PKA signaling plays a vital role in regulating both cardiac and neuronal function, and we found that ExRai-AKAR2 robustly detected PKA activity in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes, as well as in cultured primary rat hippocampal neurons (Fig. 4a–d and Extended Data Fig. 5–7). In neurons, ExRai-AKAR2 showed a rapid, more than twofold normalized response (R488/405; ΔR/R, 246 ± 15%; n = 54) to maximal stimulation with Fsk and rolipram (Rol), representing a dramatic improvement over ExRai-AKAR1 (maximum AR/R, 54 ± 3%; n = 40) and a substantial leap in dynamic range compared with the state-of-the-art fluorescence lifetime imaging micros-copy-fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FLIM-FRET) sensor tAKARα (~26% normalized response) currently used for neuronal imaging4,5. The response from ExRai-AKAR2 could be suppressed by cotreatment with a PKA inhibitor (H89; ΔR/R, 93 ± 8%; n = 41), while cells expressing ExRai-AKAR2 (T/A) showed negligible changes (ΔR/R, 7.8 ± 0.6%; n = 63) (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 6). Stimulation with 1 μM isoproterenol (Iso) produced a 77 ± 6% (n = 136) excitation-ratio increase (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 6), and a train of 300 electrical pulses induced a rapid 54 ± 8% increase (n = 31; Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4 |. PKA activity imaging in cultured neurons using ExRai-AKAR2.

a, Left, average timecourses in hippocampal neurons treated with 50 μM Fsk and 2 μM Rol. n = 54 (ExRai-AKAR2, green trace), 63 (ExRai-AKAR2(T/A), gray trace), 41 (ExRai-AKAR2 + H89, brown trace) and 40 (ExRai-AKAR1, teal trace) cells combined from four, four, three and three experiments, respectively. Right, images showing the Ex488/Ex405 excitation ratio (pseudocolored) before and after stimulation for ExRai-AKAR2 and ExRai-AKAR2(T/A). See also Extended Data Fig. 6. b, Left, average timecourses in hippocampal neurons treated with 1 μM Iso. n = 136 (ExRai-AKAR2, green trace), 129 (ExRai-AKAR2(T/A), gray trace) and 132 (ExRai-AKARI, teal trace) cells combined from three experiments each. Right, images showing the Ex488/Ex405 excitation ratio (pseudocolored) before and after stimulation for ExRai-AKAR2 and ExRai-AKAR2(T/A). See also Extended Data Fig. 6. c, Left, average timecourses in hippocampal neurons with electrical stimulation. n = 31 (ExRai-AKAR2, green trace) and 42 (ExRai-AKAR2(T/A), gray trace) cells combined from three experiments each. Right, images showing the Ex488/Ex405 excitation ratio (pseudocolored) before and after stimulation for ExRai-AKAR2 and ExRai-AKAR2(T/A). d, Left, average responses from jRGECO1a (red trace) and ExRai-AKAR2 (R488/405, green trace) aligned to Ca2+ peaks. n = 7 cells, representing three independent experiments. Middle and right; upper, representative images of an identified Ca2+ transient event and corresponding ExRai-AKAR2 ratio image with identified region of interest circled in red and lower, representative timecourses from jRGECO1a (red trace) and ExRai-AKAR2 (R488/405, green trace) corresponding to the Ca2+ transient event (arrow) from the pictured region. See also Extended Data Fig. 7. Solid lines in a-c,d (left) indicate mean responses; shaded areas, s.d. Scale bars, 20 μm (a-c) and 1 μm (d).

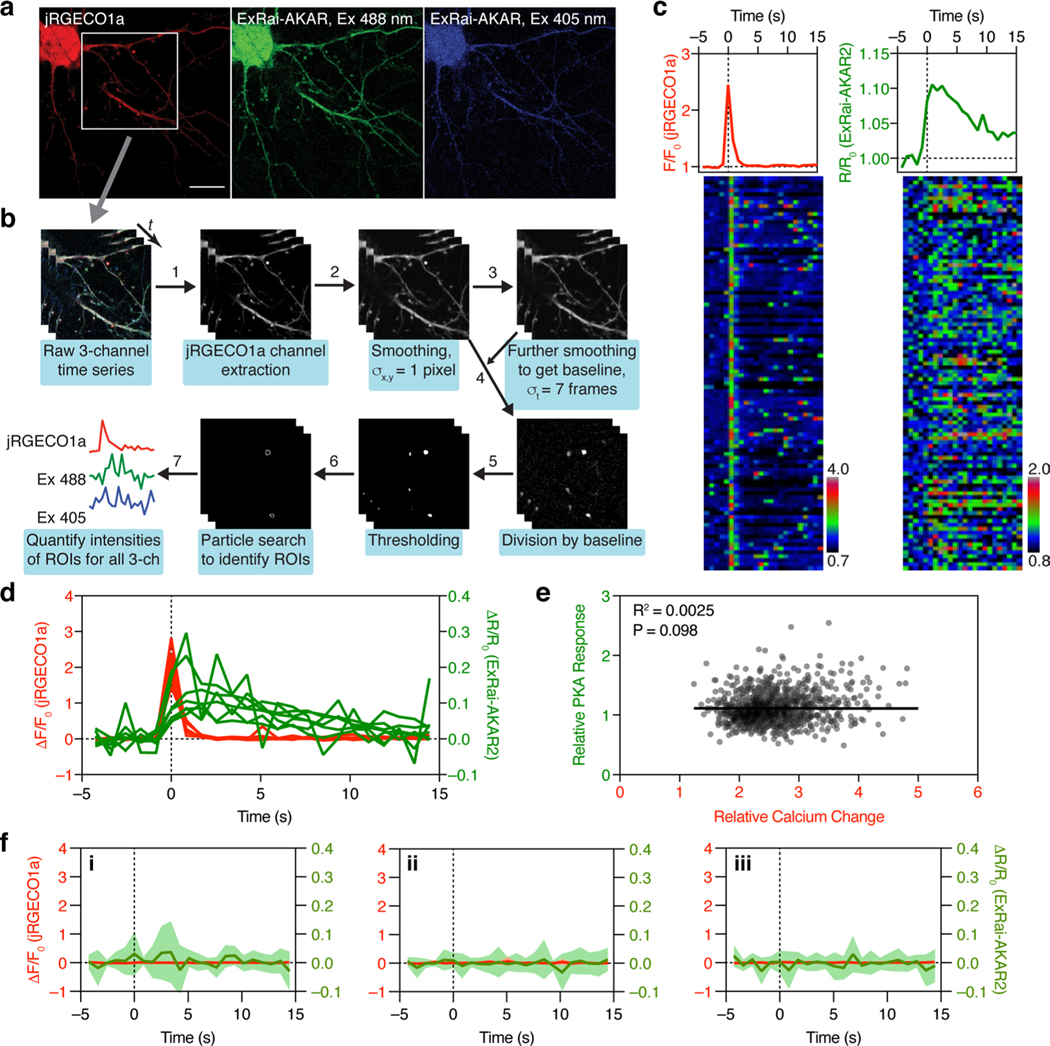

Neuronal synaptic plasticity is widely regarded as the cellular correlate of learning and memory28, with N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-dependent long-term potentiation (LTP) among the most studied forms of synaptic plasticity4,29,30. Biochemical studies have demonstrated that Ca2+ influx through NMDA-type glutamate receptors (NMDARs) activates multiple downstream signaling pathways, including PKA. However, the spatiotemporal interaction of Ca2+ entry and PKA activity has not been explored. To this end, we cotransfected cultured rat hippocampal neurons with ExRai-AKAR2 and the red Ca2+ indicator jRGECO1a31 and directly imaged Ca2+ dynamics and PKA activity during glycine stimulation, which activates NMDARs and induces Ca2+ transients. We were able to observe local PKA activity increases (~10% ΔR/R0) within 1 s of individual postsynaptic Ca2+ transients, which decayed to basal levels in ~10 s (Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig. 7). The relative PKA response was not correlated with the amplitude of Ca2+ influx but rather showed high variability (Extended Data Fig. 7) indicating the likely coregulation of PKA activity by other signals such as GPCRs in addition to Ca2+. Similar observations have been reported for PKCa (ref. 32). Such events, which most likely arise from the spontaneous fusion of individual presynaptic vesicles33,34, fall below the noise level of existing PKA sensors4,5, thus demonstrating the high sensitivity of ExRai-AKAR2 to report PKA activity.

Ultrafast in vivo kinase activity imaging in awake mice.

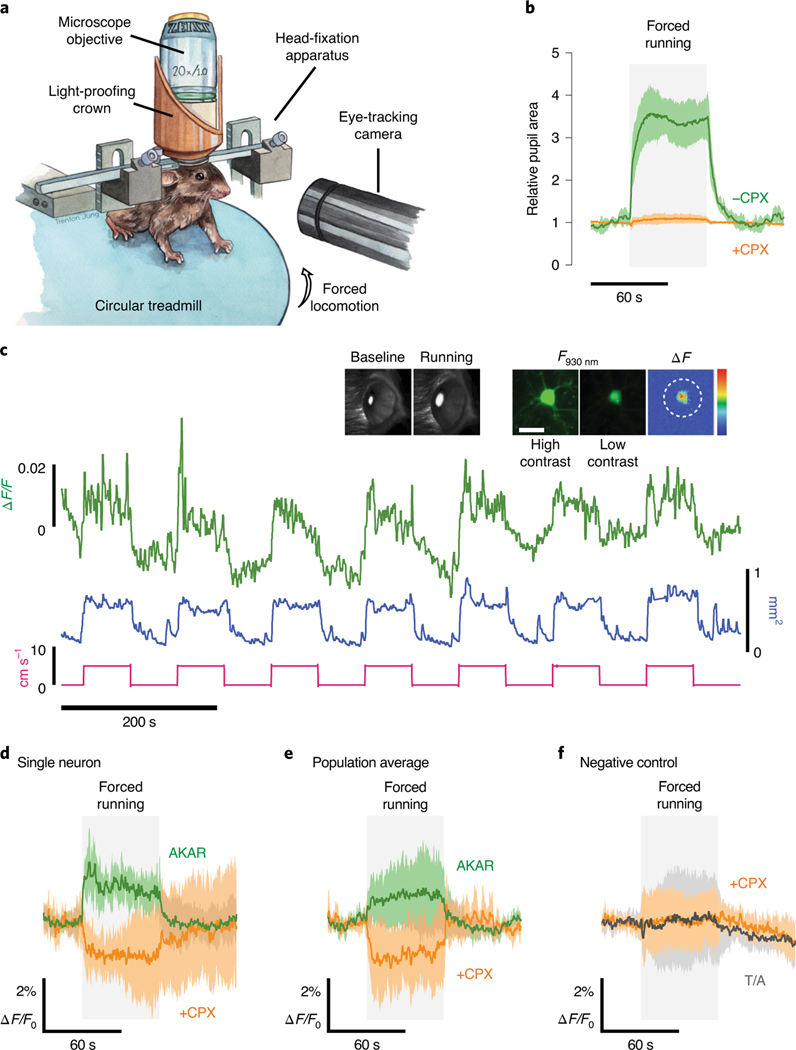

Recent efforts to track in vivo PKA activity have suffered from technical limitations that restrict temporal resolution5 or have relied on spatial averaging that obscures single-cell responses35. In contrast, the unprecedented sensitivity and straightforward, intensity-based readout of ExRai-AKAR2 should allow ultrafast monitoring of single-cell PKA dynamics in vivo using standard two-photon imaging (Extended Data Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 2). To test this, we performed head-fixed two-photon imaging in the primary visual cortex (V1) of awake mice during forced locomotion, which is known to induce noradrenergic and cholinergic activation36–40. Pupil diameter, which is controlled by a number of neuromodulators (for example, norepinephrine, dopamine and acetylcholine41) known to modulate intracellular PKA through their respective GPCRs, reliably increased ~3.5-fold during forced locomotion (Fig. 5b), while injection of the potent, broad neuromodulator blocker chlorprothixene (CPX) abolished this effect (Fig. 5b), raising the question whether similar fast-acting neuromodulation is present in the cortex.

Fig. 5 |. ExRai-AKAR2 enables rapid and sensitive kinase activity imaging in vivo.

a, Mice were head-fixed on a circular treadmill and subjected to pupillometry together with two-photon imaging of L2/3 neurons expressing ExRai-AKAR2. b, Average pupillometry timecourses show relative pupil area in mice subjected to forced running before (−CPX, green; n = 7 trials across four animals) and after (+CPX, orange; n = 4 trials across four animals) injection of CPX (5 mgkg−1; highly potent D1R, D2R, D3R, H1R, 5-HT2R, mAchR, α1 adrenergic receptor antagonist). c, Representative traces from a forced locomotion experiment with pupillometry and head-fixed two-photon imaging. Forced locomotion (5cms−1, pink trace) induced robust pupil dilation (mm2, blue trace) and diverse ExRai-AKAR2 responses (ΔF/F, green trace) in V1 L2/3 neurons. Insets, high- (middle) and low-contrast (right) images of a representative neuron expressing ExRai-AKAR2 (F930 nm) and the mean-subtracted response to forced locomotion (μF, right). A three-dimensional region of interest encompassing the neuronal soma was selected to quantify ExRai-AKAR2 responses (dashed circle). Scale bar, 20 μm. Representative images of eye pupil monitoring during baseline and forced running are also shown to the left. Back illumination from scattered two-photon excitation light provided clear pupil segmentation for dilation measurements. d,e, Averaged ExRai-AKAR2 responses for a representative neuron (d) (n = 7 repeats from a single neuron) and average response across the whole population of neurons (e). The average population response was positive before (green trace, P = 0.0140, one-sample t-test, n = 10 neurons from two mice, 0.88± 0.29%) and negative after (orange trace, P= 0.0019, unpaired t-test; n = 4 neurons from two mice, −1.28±0.54%) CPX injection. f, The ExRai-AKAR2 phosphomutant (T/A) showed minimal responses to forced locomotion both before (gray trace, P=0.933, n = 11 neurons from two mice, 0.04±0.40%) and after CPX injections (orange trace, P= 0.895, n = 7 neurons from two mice, 0.05±0.42%). Solid lines in b,d-f indicate mean responses; shaded areas, s.d.

Following adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated expression of ExRai-AKAR2 in V1, we were able to perform volumetric two-photon imaging and acquire PKA activity measurements at 5.83 Hz, >600-fold faster than current state-of-the-art 2pFLIM sensors5, all while maintaining single-cell resolution, thereby allowing us to visualize rapid and diverse ExRai-AKAR2 responses from individual layer 2/3 neurons of V1 during very brief periods of mild forced locomotion (5 cm s−1 for 1 min, Fig. 5c–e). On average, V1 neurons displayed robust (~2%) increases in ExRai-AKAR2 signal (P = 0.0140, Fig. 5e) despite the modest stimulus used and the muted neuromodulatory signaling associated with V1. We also observed short response latencies (significantly increased ΔF/F by 350 ms, P = 0.0116; Extended Data Fig. 8) that reached a population peak response within 5 s. CPX injection completely inverted the ExRai-AKAR2 response to forced locomotion (P = 0.0019, Fig. 5d,e), suggesting that neuromodulation plays a strong role in shaping cortical PKA responses5. Meanwhile, mice infected with AAV expressing the ExRai-AKAR2 phospho-acceptor mutant (T/A) showed no significant fluorescence response to forced running either before (P = 0.933) or after CPX injections (P = 0.8954, Fig. 5e). These results support the specificity and selectivity of ExRai-AKAR2 and provide a foundation for its use in vivo.

Discussion

Efforts to optimize the performance of genetically encoded fluorescent biosensors have taken on increasing urgency due to the growing use of in vivo imaging to visualize endogenous changes in biochemical activity triggered by physiological behaviors. Here, we were able to vastly enhance the performance of our previously developed ExRai-AKAR through the application of high-throughput linker library screening. The most striking feature of ExRai-AKAR2 is its extremely high dynamic range, which increased by roughly sevenfold compared with ExRai-AKAR1 (Extended Data Fig. 1) and by up to 20-fold compared with widely used ratiometric FRET-based PKA sensors11 (Supplementary Table. 1). This large dynamic range gives ExRai-AKAR2 unprecedented sensitivity to detect subtle changes in PKA activity, and indeed, ExRai-AKAR2 exhibited 50-fold higher sensitivity than ExRai-AKAR1 (ref. 11) in dose–response experiments (Extended Data Fig. 2). Such exquisite sensitivity not only enabled us to observe subsecond PKA activity increases immediately following individual postsynaptic Ca2+ transients during LTP (Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig. 7), likely arising from single spontaneous presynaptic vesicle release events33,34, but also permitted robust detection of PKA activity changes via both FACS- and microplate reader-based assays (Fig. 3), thus highlighting the broad experimental use of ExRai-AKAR2.

PKA signaling plays a central role in regulating neuronal function, both as a mediator of activity-dependent synaptic plasticity (that is, LTP and LTD)28 and as an integrator of diverse GPCR-based neuromodulatory inputs3,5,10. In vivo PKA activity imaging can therefore serve as a natural complement to the growing toolkit of genetically encoded Ca2+ (refs. 25,42), voltage43,44 and neuromodulator45,46 indicators. Yet current in vivo PKA imaging uses probes that have been specifically optimized for 2pFLIM2,5, which inherently limits temporal resolution due to the need for relatively long acquisition intervals. Fluorescence photometry can be used to boost SNR and improve the temporal resolution of 2pFLIM47,48; however, this approach necessarily sacrifices spatial resolution. In contrast, the high sensitivity and simple, intensiometric readout of ExRai-AKAR2 enabled us to achieve ultrafast in vivo imaging of PKA activity with single-cell resolution using standard 2p imaging, through which we revealed robust, millisecond-timescale recruitment of neuronal PKA activity by neuromodulatory signaling induced by a modest locomotor stimulus (Fig. 5). Although these experiments benefited from our ability to perform single-wavelength imaging owing to the large phosphorylation-induced intensity change of the anionic chromophore species (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 8), future improvements in 2p imaging hardware should enable fast, dual-excitation-ratiometric imaging of ExRai-AKAR2, yielding even greater in vivo SNR.

In sum, ExRai-AKAR2 is an ultrasensitive, accessible tool for dynamically monitoring PKA activity with plug-and-play compatibility across diverse experimental modalities, providing new capabilities for elucidating the spatiotemporal dynamics of PKA signaling, particularly in vivo. Studies of this prototypical kinase notably inspired the very first fluorescent kinase activity reporter49,50, and given the generality of the linker optimization approach, ExRai-AKAR2 is similarly poised to lead the way for an entirely new collection of kinase activity reporters to transform in vivo signaling studies.

online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-020-00660-y.

Methods

Generating ExRai-AKAR2.

To generate the linker library, the cpEGFP domain of ExRai-AKARI was PCR amplified using degenerate primers (forward primer 5′-GGCACCGGCGGCAGCGAGCTCAGCNNSNNSAACGTCTATA-TCAAGGCCGACAAGCAGAAG–3′ and reverse primer 5′-CGATCTGTTCTTGAGAAAACTTATGSNNSNNGTTGTACTCCAGCTTGTGCCCCAGGATGTT–3′; green fluorescent protein- (GFP-)complementary sequences underlined; N indicates any base and S indicates G or C) and inserted via Gibson assembly into Sacl/Sphl-digested pRSETb (Invitrogen) between a PKA substrate sequence and FHA1 domain. The resulting plasmid mixture was transformed into E. coli DH5α cells, and transformed colonies from ten plates were scraped and pooled to extract the final library. Plasmid library DNA was then transformed into E. coli BL21 cells, which were spread across 20 LB ampicillin agar plates. Transformed colonies were photographed at two illumination wavelengths (387/45 and 480/40 excitation filters) using an in-house fluorescence imager equipped with a broad-spectrum lamp source (MAX-303, Asahi Spectra) and a Thorlabs USB digital camera mounted behind a Thorlabs emission filter wheel (535/50 emission filter). Colonies with bright fluorescence at 387-nm excitation and dim fluorescence at 480-nm excitation were selected for lysate screening.

Selected colonies were cultured for 24 h at 37 °C in deep-well 96-well plates, after which 100 μl from each well was aliquoted into clear 96-well plates for storage and subsequent retrieval. The remaining cultures were incubated for 24 h at 18 °C in the presence of 0.4 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) to induce biosensor expression. Following centrifugation, bacterial pellets were lysed using a combination of freeze/thaw and enzymatic extraction (B-PER, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cleared lysates (80 μl) were aliquoted into clean 96-well plates containing 10 μl of 10× kinase assay buffer (500 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM DTT, 0.1% Brij 35) and read on a Spark 20M fluorescence plate reader (TECAN) at 380- and 480-nm excitation to obtain baseline intensities. Plates were reread after incubation for 1 h at 30 °C with ATP (3 μl, 10 mM stock) and recombinant PKA catalytic subunit (PKAcat) (7 μl, 300 μg ml−1 stock), which was purified as described51. Lysates expressing ExRai-AKAR1 and ExRai-AKAR1(T/A) were included as positive and negative controls, respectively. Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel version 16.39 to calculate ΔF/F and ΔR/R values and identify interesting clones. Plasmid DNA was then prepped from stored bacterial aliquots for sequencing and linker identification, and candidate sensors were subcloned into pcDNA3.1(+) behind a Kozak sequence via BamHI/EcoRI digestion for subsequent validation in mammalian cells.

Plasmids.

ExRai-AKAR1 (ref. 11), mCherry-tagged PKIa (ref. 49), RAB-EKARev23, B-GECO1 (ref. 24) and NIR-GECO1 (ref. 25) were described previously. ExRai-AKAR2(T/A) was generated by subcloning a SacI/EcoRI-digested fragment containing the cpEGFP, FHA1 and linkers from ExRai-AKAR2 into a SacI/EcoRI-digested ExRai-AKAR1(T/A) backbone. Plasma membrane-, outer mitochondrial membrane- and ER-targeted ExRai-AKAR2 variants were generated by subcloning a BamHI/EcoRI-digested fragment containing full-length ExRai-AKAR2 into BamHI/EcoRI-digested backbones containing the N-terminal 11 amino acids from Lyn kinase (MGCIKSKRKDK), an N-terminal 30 amino acid leader sequence from DAKAP1 (MAIQLRSLFPLALPGMALLGWWWFFSRKK) and the N-terminal 27 amino acids from CYP450 (MDPVVVLGLCLSCLLLLSLWKQSYGGG), respectively. For neuronal expression, ExRai-AKAR2 and ExRai-AKAR2(T/A) were subcloned into pCAGGS using standard molecular cloning techniques. All constructs were verified by sequencing.

Biosensor purification and in vitro characterization.

Polyhistidine-tagged ExRai-AKAR2 in pQTEV was transformed into E. coli BL21 cells and purified by nickel affinity chromatography. Briefly, cells were grown at 37 °C to an optical density (OD600 nm) of 0.3–0.4 and then induced overnight at 18 °C with 0.4 mM IPTG. The cells were pelleted, resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 300 mM NaCl) containing 1 mM PMSF and Complete EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche), and lysed by sonication. Following centrifugation at 25,000g for 30 min at 4 °C, the clarified lysate was loaded onto an Ni-NTA column, and bound protein was subsequently eluted using an imidazole gradient (10–200 mM). Eluted fractions were analyzed via SDS-PAGE, pooled and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal columns (30-kD cut-off, Millipore). Protein concentrations were determined using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on a Spark 20M microplate reader (Tecan).

One-photon excitation and emission spectra were obtained on a PTI QM-400 fluorometer using FelixGX v.4.1.2 software (Horiba). Excitation scans were collected at 530-nm emission, and emission scans were performed at 400- and 480-nm excitation. Purified biosensor (1 μM) was incubated with 5 μg of PKAcat for 30 min at 30 °C in kinase assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 0.01% Brij 35) without ATP for unphosphorylated spectra or with 200 μM ATP for phosphorylated spectra.

Two-photon excitation (2PE) spectra (unscaled) were measured using a tunable femtosecond InSight DeepSee Dual (Spectra Physics) laser coupled to a PC1 photon counting spectrofluorimeter (ISS). The details of the experimental setup, as well as the measurement procedure, are described in ref. 52. A combination of short-pass filters, 770SP, 633SP and 680SP (all Semrock), was used to eliminate the scattered laser light.

The two-photon molecular brightness as a function of excitation wavelength λ, F2(λ), in the whole spectral range is a linear combination of the contributions from the neutral (subscript N in the following, peaking near 800 nm) and anionic (subscript A in the following, peaking near 940 nm) forms of the chromophore. The two forms coexist in equilibrium in protein solution, with relative weights that change on phosphorylation. F2(λ) can thus be presented as follows:53,54

| (1) |

where ρA,N is the relative fraction of form A or , and φ is the fluorescence quantum yield of form A or N. Since we collect the total fluorescence spectrum, the quantum yield of the initially excited neutral form technically comprises fluorescence from both the neutral and anionic excited states that appears as a result of excited-state proton transfer. σ2(λ)is the two-photon absorption cross section of either form as a function of wavelength.

To obtain the 2PE spectrum in units of molecular brightness, we independently measured ρA, φA and σ2,A(λ) and normalized the unscaled 2PE spectrum to the product in the region where the contribution from the neutral form is negligible (λ > 940 nm). The peak extinction coefficients of the neutral and anionic forms for the unphosphorylated sensor were obtained by gradual stepwise alkaline titration of the sample and recording of the absorption spectrum at each step, as described previously54. Plotting the optical density of the anionic peak (504 nm) versus the neutral peak (400 nm) at the start of titration gives the ratio of the corresponding extinction coefficients. Comparing the optical densities of the denatured protein absorption peak (with a known extinction coefficient of 44,000 M−1 cm−1 at 450 nm, ref. 55) to those of the initial anionic and neutral forms provides a second equation that allows calculating the peak extinction coefficients of both A and N forms. Alkaline titration of the phosphorylated sample failed to yield extinction coefficients because at a certain point during titration the solution suddenly became very strongly scattering, likely because of protein aggregation. Therefore, we assumed the same extinction coefficient values for both the N and A forms of the phosphorylated sensor as were obtained for the unphosphorylated sensor. ρA and ρN values (for either the unphosphorylated or phosphorylated form) were measured using the peak optical densities of the two forms in the absorption spectrum (at neutral pH) and known extinction coefficients.

The two-photon absorption cross section of the anionic forms of both the unphosphorylated and phosphorylated sensor was measured relative to Rhodamine 6G in methanol at two different wavelengths, 940 nm ( = 9 GM, ref. 52) and 960 nm (= 13 GM, ref. 52), where 1 GM (Goeppert-Mayer) = 10−50 cm4s. Here, we used a modification of the method described in ref. 52. First, we measured the total 2PE fluorescence signal I as a function of laser power P for both the sample and reference solutions (the peak optical density in 3 × 3 mm2 cuvettes was less than 0.1)52. Total (spectrally integrated) fluorescence was collected at 90° to excitation through a combination of filters, 770SP (Semrock) and 520LP (Chroma), using the left emission channel of a PC1 spectrofluorimeter (ISS). The power dependences of fluorescence were fit to a quadratic function I = aP2, from which the coefficients as and aR were obtained for the sample (index S) and reference (index R), respectively. Second, the one-photon excited fluorescence signals were measured from the same samples under the same registration conditions. For one-photon excitation, we used the strongly attenuated radiation from the 488-nm line of an IMA101040 ALS (Melles Griot) argon ion laser (selected with an interference filter). The power dependences were measured at the same maximum laser power values and were fitted to the linear function I = bP, from which the coefficients bS and bR were obtained. The two-photon absorption cross section can then be calculated as follows:

| (2) |

Here, λ1 is the wavelength used for one-photon excitation (488 nm in this case), and λ2 is the wavelength used for two-photon excitation (940 or 960 nm in this case). This approach corrects for the laser beam properties in the excitation volume (canceled by the ratio aS/aR), fluorescence collection efficiencies (canceled by the ratios aS/aR and bR/bS), PMT spectral sensitivity (canceled by the ratios aS/bS and bR/aR), and differences in quantum yields and concentrations between S and R solutions (canceled by the ratios aS/bS and bR/aR). The two-photon cross sections obtained at 940 and 960 nm excitation for the same protein state (either unphosphorylated or phosphorylated) give very similar peak cross section values, presented in Supplementary Table 2 (if the spectral shapes of the two-photon absorption are taken into account).

Fluorescence quantum yields were measured in diluted samples (OD < 0.1) with an absolute method, using a Quantaurus-QY (Hamamatsu) integrating sphere fluorimeter. We used 400 nm for the excitation wavelength of the neutral forms. For the anionic forms, the quantum yield was measured with the excitation wavelength scanned in the region of a short-wavelength part of the absorption peak for the anionic form (480–510 nm) with 5-nm steps. The quantum yield value did not depend on excitation wavelength in the range of 480–505 nm (for the unphosphorylated state) or from 485 to 495 nm (for the phosphorylated state). The average values of the quantum yields are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

Finally, the products ρAφAσ2,A(λm) were calculated using the 2P cross section taken at spectral maximum λm for both sensor states, and the 2PE spectra were scaled to these values. The results are presented in Extended Data Fig. 8. The two-photon absorption peak wavelengths of the anionic bands do not coincide with the corresponding one-photon absorption peak wavelengths that are expected near 1,000 nm. This shift was observed previously for other fluorescent proteins and dyes and is probably due to specific enhancement of a particular vibronic transition in two-photon absorption56.

Cell culture and transfection.

HeLa and HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Gibco) containing 1 g l−1 of glucose, 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma) and 1% (v/v) penicillin-streptomycin (Pen-Strep) (Sigma-Aldrich). PC12 cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco) containing 1 g l−1 of glucose, 10% (v/v) FBS (Sigma), 5% donor horse serum (Gibco) and 1% (v/v) Pen-Strep (Sigma-Aldrich). All cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. For imaging experiments, cells were plated onto sterile 35-mm glass-bottomed dishes and grown to 50–70% confluence. Transient transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), after which cells were cultured for an additional 24 h (HeLa, HEK293T) or 48 h (PC12). HeLa cells were given fresh culture medium 2 h after transfection.

Neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes were isolated from the cardiac ventricles of 1–2-day-old Sprague-Dawley rat pups as described57. All animals were treated according to UC San Diego Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. Myocytes (3.0 × 104 cm−2) were plated on laminin-coated 35-mm glass-bottomed dishes and cultured in DMEM containing 15% FBS. Cells were transfected after 24 h using PolyJet (SignaGen Laboratories) and cultured an additional 48 h, with a media exchange occurring 24 h after transfection.

Hippocampal neurons were obtained from embryonic day 18 Sprague-Dawley rats and plated onto poly-L-lysine-coated 18-mm glass coverslips in standard 12-well tissue culture dishes at a density of 150,000 cells per well in neurobasal media (Gibco) supplemented with 2% B-27, 4 mM GlutaMax, 50 U ml−1 of Pen-Strep and 5% horse serum (Hyclone). Culture media was changed the next day to NM0 (neurobasal media supplemented with 2% B-27, 2 mM GlutaMax and 50 U ml−1 of Pen-Strep), and neurons were fed once a week with NM0. At 15–18 d in vitro, neurons were transfected with the indicated plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). All experimental procedures involving animals were conducted according to the National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal research and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Biosensor localization.

HeLa cells expressing mitochondrial- or ER-targeted ExRai-AKAR2 were stained for 30 min with MitoTracker RED (Invitrogen) or ER-Tracker RED (Invitrogen), respectively, at a final concentration of 1 mM in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) (Gibco). These cells, as well as cells expressing plasma membrane-targeted ExRai-AKAR2, were imaged on a Nikon Ti2 spinning-disk confocal microscope (Nikon Instruments) equipped with an S Fluor 40×/1.3 numerical aperture (NA) oil objective (Nikon) and a Photometrics Prime95B sCMOS camera (Photometrics) and housed in the Nikon Imaging Center at UC San Diego. GFP images were acquired using 488- and 405-nm lasers at 10 and 40%, respectively, and 200-ms exposure times. Red fluorescent protein (RFP) images were acquired using a 561-nm laser at 20% power and 200 ms exposure time.

Time-lapse fluorescence imaging.

Widefield epifluorescence imaging.

Cells were washed twice with HBSS and subsequently imaged in HBSS in the dark at 37 °C. Forskolin (Fsk) (Calbiochem), IBMX (Sigma), H89 (Sigma), Iso (Sigma) and NGF (Harlan Laboratories) were added as indicated.

HeLa and HEK293T cells were imaged on a Zeiss AxioObserver Z7 microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a Definite Focus.2 system (Carl Zeiss), a 40×/1.4 NA oil objective and a Photometrics Prime95B sCMOS camera (Photometrics) and controlled by METAFLUOR 7.7 software (Molecular Devices). Dual GFP excitation-ratio imaging was performed using 480DF20 and 405DF20 excitation filters, a 505DRLP dichroic mirror and a 535DF50 emission filter. RFP intensity was imaged using a 572DF35 excitation filter, a 594DRLP dichroic mirror and a 645DF75 emission filter. Dual cyan/yellow emission ratio imaging was performed using a 420DF20 excitation filter, a 455DRLP dichroic mirror and two emission filters (473DF24 for cyan fluorescent protein and 535DF25 for yellow fluorescent protein). Filter sets were alternated by an LEP MAC6000 control module (Ludl Electronic Products Ltd). Exposure times ranged from 200 to 500 ms, and images were acquired every 15–30 s.

Multiplexed imaging in PC12 cells was performed on a Zeiss AxioObserver Z1 microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a Definite Focus system (Carl Zeiss), a 40×/1.3 NA oil objective and a Photometrics Evolve 512 EMCCD (Photometrics) and controlled by METAFLUOR 7.7 software (Molecular Devices). Dual GFP excitation-ratio imaging was performed using 480DF30 and 405DF40 excitation filters, a 505DRLP dichroic mirror and a 535DF45 emission filter. RFP intensity was imaged using a 555DF25 excitation filter, a 568DRLP dichroic mirror and a 650DF100 emission filter. Blue fluorescent protein (BFP) intensity was imaged using a 405DF40 excitation filter, a 450DRLP dichroic mirror and a 475DF40 emission filter. mIFP intensity was imaged using a 640DF30 excitation filter, a 660DRLP dichroic mirror and a 700DF75 emission filter. All filter sets were alternated using a Lambda 10–2 filter changer (Sutter Instruments). Exposure times for each channel were 500 ms, with electron multiplying gain set to 50, and images were acquired every 30 s.

Neonatal cardiomyocytes were imaged on a Zeiss Axiovert 200M (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a 40×/1.3 NA oil objective and an 0RCA-Flash4.0 LT+ digital CMOS camera (Hamamatsu) controlled by METAFLUOR 7.7 software (Molecular Devices). Dual GFP excitation-ratio imaging was performed using a 480DF30 excitation filter/505DRLP dichroic mirror, a 380DF10 excitation filter/450DRLP dichroic mirror and a 535DF45 emission filter. All filter sets were alternated using a Lambda 10–2 filter changer (Sutter Instruments). Exposure times were 500 ms for each channel, and images were acquired every 20 s.

Raw fluorescence images were corrected by subtracting the background fluorescence intensity of a cell-free region from the emission intensities of biosensor-expressing cells at each time point. GFP excitation ratios (Ex480/Ex405 or Ex480/Ex380) and RFP, BFP or mIFP fluorescence intensities were then calculated at each time point. All biosensor response timecourses were subsequently plotted as the normalized fluorescence intensity or ratio change with respect to time zero (ΔF/F0 or ΔR/R0), calculated as (F − F0)/F0 or (R − R0)/R0, where F and R are the fluorescence intensity and ratio value at a given time point, and F0 and R0 are the initial fluorescence intensity or ratio value at time zero, which was defined as the time point immediately preceding drug addition. Maximum intensity (ΔF/F) or ratio (ΔR/R) changes were calculated as , where Fmax and Fmin or Rmax and Rmin are the maximum and minimum intensity or ratio value recorded after stimulation, respectively. Graphs were plotted using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software).

Confocal fluorescence imaging of cultured hippocampal neurons.

Neurons were imaged 2–4 d after transfection on a Zeiss spinning-disk confocal microscope equipped with an AxioObserver Z1 stand, a Yokogawa CSU-X1A 5000 spinning-disk unit, a Definite Focus system, a 20×/0.8 NA air objective and a 63×/1.6 NA oil objective, a Photometrics Evolve EMCCD camera, four lasers (a Lasos ML 8 100-mW Argon laser (405/458/488-nm), a Lasos DPSS 50-mW 405-nm laser, a Lasos DPSS 40-mW 561-nm laser and a Lasos DPSS 30-mW 639-nm laser) and an AOTF, controlled by ZEN 1.1.1.0 software (Zeiss). Dual GFP excitation-ratio imaging was performed using the 488- and 405-nm lasers, a RQFT 405/488/568/647 dichroic mirror and a 525/50 emission filter. jRGECO1a was imaged using the 561-nm laser, the RQFT 405/488/568/647 dichroic mirror and a 629/62 emission filter. Exposure time for every channel was 50 ms with electron multiplying gain set to 1,000.

Neurons were preincubated in 37 °C artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF, 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM D-glucose and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) for at least 60 min before being mounted on the microscope. Coverslips with neurons were mounted on a heated, custom-built chamber with (for Iso and electrical stimulations) or without perfusion (for Fsk/Rol and glycine stimulation) and imaged in ACSF warmed to 37 °C.

For Fsk/Rol stimulation, image stacks were acquired every 2 min. After 2–3 baseline images, 50 μM Fsk and 2 μM Rol were manually added to the chamber. For Iso stimulation, neurons were perfused with warm ACSF, and image stacks were acquired every 2 min. After five baseline images, neurons were stimulated with 1 μM Iso in ACSF. For electrical stimulation, neurons were perfused with warm ACSF in a custom electrical stimulation chamber and image stacks were acquired every 5 s. After 24 baseline images, neurons were stimulated with 300 pulses of 1 ms at 50 Hz (ref. 58). For glycine stimulation, neuron culture media were supplemented with 200 μM DL-AP5 1 d before experiments. The next day, neurons were preincubated in basal ACSF (ACSF supplemented with 200 μM DL-AP5, 1 μM TTX, 1 μM strychnine and 100 μM picrotoxin) for at least 1 h before imaging. Images (fixed Z position) were acquired in streaming mode (roughly one image every 0.85 s). Following 5–10 min of baseline recording, neurons were stimulated with glycine (ACSF without MgCl2, supplemented with 1 μM TTX, 1 μM strychnine, 100 μM picrotoxin and 200 μM glycine).

For image analysis of Fsk/Rol, Iso and electrical stimulation experiments, images were max-projected along the z axis, and background-subtracted intensity values of the cell soma (Extended Data Fig. 6e) were normalized to the average intensity during baseline. For glycine stimulation experiments, images were processed and analyzed as follows (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b): jRGECO1a images were smoothed using a Gaussian filter with σ = 1 pixel. Baseline images were generated by further smoothing along the time axis with σ = 7 frames. The smoothed images were divided by the baseline images. Ca2+ transient events were identified in the resulting ratio images using a threshold of 1.5. jRGECO1a intensity, and ExRai-AKAR2 ratio values were aligned to the peak of individual Ca2+ transient events and normalized using five data points before Ca2+ transients. For Extended Data Fig. 7f, random time points were used for alignment and normalization. All image analysis and quantification were performed using ImageJ/Fiji.

Awake in vivo two-photon fluorescence imaging, pupillometry and forced locomotion.

All animals were treated in accordance with the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. Animals were double housed and kept on a 12h/12 h light/dark cycle, with temperature and humidity maintained at 22 ± 2 °C and 30–70%, respectively. Imaging experiments were performed at similar times of day to avoid circadian cycle-related effects. A craniotomy was made in C57BL/6 mice at the age of 3–5 months over the primary visual cortex (V1), and a mixture of AAV2/1-CaMKII-Cre (Addgene no. 105558, ~2 × 109 vg ml−1) and AAV2/9-hSyn1-DIO-ExRai-AKAR2 (or the T/A mutant, HHMI-Janelia Viral Tools, ~5 × 1013 vg ml−1) was injected (100 nl per site) through stereotaxic surgery. A cranial window was made by placing a 4 × 4-mm glass coverslip over the craniotomy and a stainless-steel head bar was attached to the skull during surgery to allow rigid head-fixation during imaging. Mice were allowed to recover for 1–2 weeks before imaging.

Retinotopy was performed to verify the location of V1, and the mice were habituated to a head-fixed circular treadmill (Fig. 5 a). The treadmill was equipped with an encoder for speed measurements, as well as a stepper motor for forced locomotion. Awake in vivo two-photon imaging was carried out with a custom-built, two-photon laser-scanning microscope (Sutter) controlled by ScanImage 2018 (Vidrio Technologies) and light-proofed to allow imaging in ambient light. Providing ambient light was important to prevent complete dilation of the pupil during imaging. Neurons expressing ExRai-AKAR2 were imaged using a 20×/1.0 NA water-immersion objective (Zeiss) and a Ti:Sapphire laser (Insight X3, Spectra Physics) tuned at 930 nm with <100 mW of power delivered to the back-aperture of the objective. A resonant scanner (Sutter) and a piezo stage (nPFocus 250, nPoint) were used to achieve high-speed volume imaging (256 × 256 × 10 pixels, 130 × 130 × 40 μm3 volumes, 5.833 Hz). A fast (149 FPS) IR-sensitive camera (CM3-U3–13Y3M-CS, FLIR) tracked eye movements and pupil size. Following baseline acquisition (1 min), the treadmill was gently turned by the stepper motor at 5 cm s−1 for 1 min every other minute repeatedly (>7 times) to assess the effect of forced locomotion. To test the role of neuromodulation, CPX (5 mg kg−1) was administered by intraperitoneal injection and imaging was commenced >15 min after injection.

The resulting volume image videos were motion-corrected with rigid three-dimensional registration (NoRMCorre59 implemented in MATLAB R2018b) and cropped for subsequent analysis. Pupil diameter was estimated by fitting an ellipse to the pupil, which is sufficiently back-illuminated by the two-photon laser during imaging.

Fluorescence microplate reading.

Black-walled, clear-bottom 96-well assay plates (Costar) were coated with 0.1 mg ml−1 of poly-D-lysine in boric acid buffer (pH 8.5) for 24 h and then seeded with 5 × 104 HEK293T cells per well. Cells were transfected the same day using Lipofectamine 2000 and cultured for 24 h.

Fluorescence intensity was read on a Spark 20M fluorescence plate reader using SparkControl Magellan 1.2 (TECAN). Cells were washed once and then placed in HBSS to acquire a baseline reading. Afterward, the HBSS was washed out and exchanged with 60 μl of HBSS containing the indicated concentrations of Fsk (Calbiochem), IBMX (Sigma), angiotensin II (Sigma), lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) (Enzo Life Science), Iso (Sigma), epinephrine (Sigma), propranolol (Sigma), ritodrine (Sigma), prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) (Cayman Chemical), PGE2 (Cayman Chemical), dopamine (Sigma), glucagon-like peptide 1 (Sigma), ATP (New England BioLabs), endothelin 1 (Sigma) or histamine (Sigma-Aldrich). For each cycle, each well was read twice with 480-nm excitation/520-nm emission and 400-nm excitation/520-nm emission. Plate reader data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel 16.39. Raw fluorescence values from each well were corrected by subtracting the background fluorescence intensity of a nontransfected well. GFP excitation ratios (F480/F400) were then calculated for each well at each time point. All timecourses were normalized by dividing by the baseline ratio acquired preceding drug addition.

Flow cytometry.

Transiently transfected HEK293T cells were collected with 0.25% trypsin for 1 min at room temperature, washed twice with 1× DPBS, resuspended in sort buffer (1× DPBS, 0.5% BSA, 25 mM HEPES, pH 7 and 1 mM EDTA) at a density of 5 × 106 cells per ml and strained (FALCON) to prevent clogging. Approximately 200 μl of strained, suspended cells was aliquoted and treated with 50 μ.M Fsk and 100 μM IBMX for 10 min. Both Fsk/IBMX-treated and untreated cells were sorted for fluorescence intensity at 405- (520/35 emission filter) and 488-nm excitation (530/40 emission filter) on a BD Influx Cell Sorter running BD FACS Software v.1.2.0.142 (BD Biosciences). Debris, dead cells and cell aggregates were gated out before fluorescence interrogation by monitoring the forward and side scatter (Supplementary Fig. 6). Approximately 500,000 single cells were measured, and 100,000 cells were randomly selected for analysis and plotted with FlowJo 10.6.1 software. Sorting was repeated three times.

To compare the sensitivity of ExRai-AKAR2 and ExRai-AKAR1, we calculated the sensitivity index (SI) using the method of Telford et al.60.

| (3) |

where medtreated is the median ratio value after Fsk/IBMX stimulation, meduntreated is the median ratio value in unstimulated cells, and 84%untreated is the 84th percentile of the median ratio value in unstimulated cells. The results are summarized in Extended Data Fig. 4.

Statistics and reproducibility.

The bacterial lysate screen (Supplementary Fig. 1) was performed once. All other experiments were independently repeated as noted in the figure legends. All replication attempts were successful. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software). For Gaussian data, pairwise comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test or Welch’s unequal variance t-test, and comparisons among three or more groups were performed using ordinary one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons. To test for significant deviations from baseline in Fig. 5d-f, the average response of the first 30 s of each forced-running trial was analyzed with one-sample t-tests. Non-Gaussian data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U-test for pairwise comparisons or the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test for analyses of three or more groups. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Averaged live-cell imaging and plate reader timecourses depict mean ± s.d.; bar graphs and scatter plots depict the mean ± s.e.m. and violin plots depict the median and quartiles, as indicated in the figure legends.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Identification and characterization of ExRai-AKAR2.

a, Maximum 480 nm/405 nm excitation ratio changes (ΔR/R) of ExRai-AKAR linker variants in HeLa cells stimulated with 50 μM Fsk and 100 μM IBMX. The best-performing candidate was designated ExRai-AKAR2 (P = 0.0002, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction). From left to right: n = 34, 27, 27, 31, 31, 49, 29, 27, 23, 30, 40, 30, 41, 24, 32, 43, 43, 40, 32, 45, and 30 cells combined from 3 independent experiments each. b, Domain structures of ExRai-AKAR1 and ExRai-AKAR2. c, ExRai-AKAR2 is modestly but significantly brighter than ExRai-AKAR1 in both excitation channels (****P < 0.0001; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction). n = 227 (ExRai-AKAR1) and 136 cells (ExRai-AKAR2) imaged in multiple fields across 4 and 5 separate experiments, respectively. Data are plotted as log-transformed intensity values. Brightness increases for each channel were calculated by subtracting the average log intensity of ExRai-AKAR1 from that of ExRai-AKAR2 and then reversing the log transformation (10x). For example, the average log intensities at 480-nm excitation for ExRai-AKAR2 and ExRai-AKAR1 were 3.129 and 2.883, respectively. Given that 10(3.129–2.883) = 1.762, we conclude that ExRai-AKAR2 has ~76% higher 480 nm-excited intensity, on average, than ExRai-AKAR1. d, ExRai-AKAR2 exhibits significantly larger fluorescence intensity changes in both excitation channels versus ExRai-AKAR1 in response to PKA stimulation (****P < 0.0001; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction). n = 68 (ExRai-AKAR1) and 70 (ExRai-AKAR2) cells combined from 3 independent experiments. e,f, ExRai-AKAR2 exhibits a dramatically higher (e) maximum 488 nm/405 nm excitation ratio change (ΔR/R) and (f) signal-to-noise ratio compared with ExRai-AKAR1 in HeLa cells stimulated with Fsk/IBMX (****P < 0.0001; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction). Data in f are pooled from 3 (ExRai-AKAR2) and 4 (ExRai-AKAR1) experiments. Error bars indicate mean±s.e.m. ExRai-AKAR2 data in d, e are reproduced from Fig. 1c–e.

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Comparing ExRai-AKAR2 performance with previous PKA sensors.

(a, b) Side-by-side comparison of ExRai-AKAR2 with existing intensity-ratio-based PKA sensors. a, Average time-course showing the enhanced ratio response (ΔR/R0) of ExRai-AKAR2 (n = 18) versus ExRai-AKAR1 (n = 11), AKAR4 (n = 18), and AKAR3-EV (n = 18) in HeLa cells stimulated with 50 μM Fsk and 100 μM IBMX (Fsk/IBMX). Solid lines indicate average responses; shaded areas, s.d. b, Summary of the maximum ratio changes (ΔR/R) for ExRai-AKAR2 (n = 44), ExRai-AKAR1 (n = 39), AKAR4 (n = 38), and AKAR3-EV (n = 36) following Fsk/IBXM stimulation. Representative pseudocolor images below the graph depict the raw emission (AKAR4, AKAR3-EV) or excitation ratio (ExRai-AKAR1, ExRai-AKAR2) before (upper) and after (lower) Fsk/IBMX stimulation. Warmer colors indicate higher ratios. Scale bars, 10 μm. Data are representative of (a) or combined from (b) 2 independent experiments. Error bars in b indicate mean±s.e.m. c, Fsk dose response of ExRai-AKAR2. HeLa cells expressing ExRai-AKAR2 (n = 48) were successively stimulated with the indicated concentrations of Fsk, followed by 100 μM IBMX. Data are plotted as ΔR/ΔRmax = (R[Fsk]−R0)/(RIBMX − R0), where R[Fsk] is the maximum ratio recorded after the addition of a given Fsk dose, RIBMX is the maximum ratio recorded following IBMX addition at the end of the experiment, and R0 is the ratio recorded immediately prior to the first drug addition (for example, t = 0). Data are combined from 2 independent experiments. Solid and dashed lines indicate the median and quartiles, respectively. ****P < 0.0001 vs. 0; two-tailed Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Detecting local PKA signaling with subcellularly targeted ExRai-AKAR2.

a, Domain structures of ExRai-AKAR2 constructs targeted to the plasma membrane, outer mitochondrial membrane, and ER membrane. b, Representative confocal fluorescence images showing the plasma membrane, mitochondrial, and ER localization of pmExRai-AKAR2, mitoExRai-AKAR2, and erExRai-AKAR2, respectively, in both excitation channels (Ex488, Ex405). For mito- and erExRai-AKAR2, images of the red fluorescence signal (Ex561) from MitoTracker RED and ER-Tracker RED, respectively, are also shown. Merged images (far right) depict the overlay of the Ex488 (yellow), Ex405 (cyan), and Ex561 (magenta) channels. Images are representative of 2 independent experiments per condition. c–e, Time-course plots showing all individual traces corresponding to the raw 480/405 excitation ratio responses of pmExRai-AKAR2 (left), mitoExRai-AKAR2 (middle), and erExRai-AKAR2 (right), along with representative epifluorescence images of both excitation channels (below) illustrating ROI selection (dashed white lines), for the experiments shown in Fig. 2a–c. Thick lines indicate mean responses, and thin lines depict individual single-cell traces. Scale bars in b–c, 10 μm. f, Summary of the maximum excitation ratio changes (ΔR/R) for pmExRai-AKAR2 (PM; n = 46 cells from 3 experiments), mitoExRai-AKAR2 (Mito; n = 43 cells from 4 experiments), and erExRai-AKAR2 (ER; n = 35 cells from 3 experiments) in HeLa cells stimulated with Fsk/IBMX. Error bars in d indicate mean±s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. ExRai-AKAR2 is a more sensitive FACS probe than ExRai-AKAR1.

HEK293T cells transfected with ExRai-AKAR1 were analyzed via flow cytometry before and after stimulation with 50 μM Fsk and 100 μM IBMX as described in the Methods. a, Contour plot showing the 488 nmand 405 nm-excited fluorescence intensities of transfected cells without (teal) and with (green) Fsk/IBMX stimulation. b, Frequency distribution of 488 nm/405 nm excitation ratio illustrating the population shift caused by Fsk/IBMX stimulation (****P < 0.0001; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. Overlaid gray and black dashed lines depict the frequency distributions for ExRai-AKAR2 transfected cell populations before and after Fsk/IBMX treatment, respectively (redrawn from Fig. 3a). c, Table summarizing the input values and results of the sensitivity index (SI) calculation (see Methods). ExRai-AKAR2 shows 2-fold higher sensitivity compared with ExRai-AKAR1.

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. Imaging PKA activity in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes using ExRai-AKAR2.

a, Representative images of 480 nm-excited (Ex480) and 380 nm-excited (Ex380) fluorescence from a neonatal rat ventricular myocyte (NRVM) expressing ExRai-AKAR2. Scale bar, 10 μm. b,c, Time-lapse epifluorescence imaging of ExRai-AKAR2 excitation ratio changes in NRVMs stimulated with (b) 100 nM Iso or (c) 50 μM Fsk and 100 μM IBMX. Thick lines indicate mean responses, and thin lines depict individual single-cell traces. d, Summary of maximum 480 nm/380 nm excitation ratio changes. Bars represent mean±s.e.m. n = 13 (Iso) and 20 (Fsk/IBMX) cells from 3 independent experiments for b–d.

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. Imaging PKA activity using ExRai-AKAR2 in cultured hippocampal neurons.

a–c, Time-course plots showing all individual traces of the PKA-induced change in ExRai-AKAR2 fluorescence in hippocampal neurons stimulated with 50 μM Fsk and 2 μM rolipram (Rol) at 488-nm (a) and 405-nm (b) laser excitation, along with the raw 488 nm/405 nm excitation ratio (c). Thick lines indicate mean responses, and thin lines depict individual single-cell traces. d, Summary of the maximum Fsk/Rol-stimulated ExRai-AKAR responses in cultured hippocampal neurons. Error bars represent mean±s.e.m. Data in d correspond to time-courses shown in Fig. 3a. n = 54 (ExRai-AKAR2), 63 (ExRai-AKAR2[T/A]), 41 (ExRai-AKAR2 + H89) and 40 (ExRai-AKAR1) cells. ****P < 0.0001 vs. ExRai-AKAR2, Welch’s ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons. e, Representative confocal fluorescence images of the 488 nm (Ex488) and 405 nm (Ex405) channels for hippocampal neurons expressing ExRai-AKAR2 (left) or ExRai-AKAR2[T/A] (right), illustrating the selection of ROIs (dashed white lines) for experiments reported in Fig. 4a–c. Scale bars, 10 μm. f, Plot of ExRai-AKAR2-expressing neurons showing heterogeneous PKA responses of individual neurons treated with 1 μM isoproterenol, representing 36 neurons from one of three independent experiments shown in Fig. 4b.

Extended Data Fig. 7 |. Correlated Ca2+ and PKA dynamics during LTP in cultured hippocampal neurons.

a, Representative confocal fluorescence images of the 561 nm (jRGECO1a, red), 488 nm (Ex488, green), and 405 nm (Ex405, blue) channels for hippocampal neurons co-transfected with ExRai-AKAR2 and jRGECO1a, for experiments reported in Fig. 4d. Scale bar, 20 μm. b, Flow chart showing how Ca2+ transients were identified and how ROIs were drawn. c, (upper) Average responses of jRGECO1a (red) and ExRai-AKAR2 (green) for the neuron shown in (a). (lower) Color-coded time-courses of the jRGECO1a (left) and ExRai-AKAR2 (right) responses for 100 representative Ca2+ transients presented as raster plots. Each row represents one ROI. d, Responses of jRGECO1a (red) and ExRai-AKAR2 (green) in all 7 hippocampal neurons aligned to the peaks of Ca2+ transients. e, Relationship of relative PKA response and calcium influx from 1108 events in 7 neurons. Pearson correlation is not significant (P = 0.098, R2 = 0.0025). f, Aligning average responses from jRGECO1a (red) and ExRai-AKAR2 (R488/405, green) to randomly selected time points in the recording shows that PKA transients are specifically triggered by Ca2+ spikes. Three randomizations were performed using the 7 cells from 3 separate experiments. Solid lines indicate mean responses from 7 cells; shaded areas, s.d.

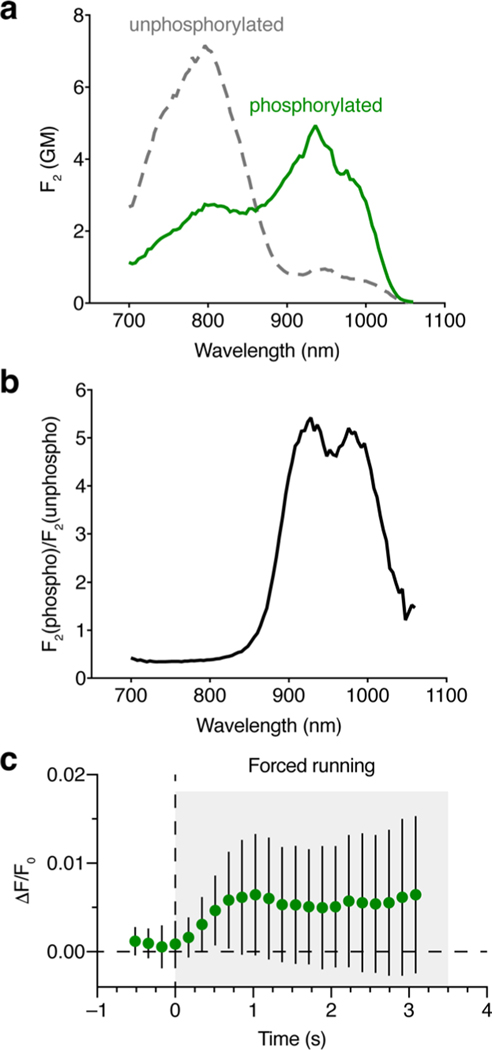

Extended Data Fig. 8 |. In vivo imaging of PKA activity using ExRai-AKAR2.

(a, b) Two-photon characterization of ExRai-AKAR2. a, Two-photon excitation spectra of purified ExRai-AKAR2 in the unphosphorylated (gray curve) and phosphorylated (green curve) states. The spectra are presented in molecular two-photon brightness values, F2, measured in GM (see Methods for details). Each spectrum consists of two overlapping bands – one belonging to the neutral form (peaking at 800 nm) and another belonging to the anionic form (peaking near 940 nm). n = 3 independent experiments. b, Ratio of the F2 values for phosphorylated and unphosphorylated ExRai-AKAR2. The ratio shows two peaks: at 930 nm (5.4) and 980 nm (5.1). The presence of two peaks is explained by a slight shift of the anionic two-photon absorption band upon phosphorylation (from 948 to 936 nm). Although excitation at 930 nm is the best for two-photon imaging, the whole range from 905 to 1000 nm provides a good contrast with F2(phospho)/F2(unphopsho) >4.6. c, Sub-second response latencies for ExRai-AKAR2 following the onset of forced locomotion. Data from Fig. 5e are re-plotted here at higher temporal frequency. Significant deviations from baseline are detected as early as 350 ms (P = 0.0116, one-tailed one-sample t-test against baseline=0; P = 0.0364, paired one-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction against last baseline point at t = 0). Error bars indicate s.d..

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to R. Campbell (University of Alberta) for generously providing B-GECO1 and NIR-GECO1 and to S. S. Taylor (UC San Diego) for providing purified PKA catalytic subunit. We also wish to thank D. Schmitt, along with E. Griffis and D. Bindels from the UC San Diego Nikon Imaging Center, for assistance with confocal imaging, as well as R. C. Johnson and O. Martinez for helping with subcloning, T.W. Jung for scientific illustrations, and J. Heller Brown and C. Brand for helping with cardiac myocyte experiments. Work in J.Z’s laboratory is supported by the National Institutes of Healthy (NIH) (grant nos. R35 CA197622 and R01 DK073368) and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9500-18-1-0051). Work by R.L.H. and J.Z. was also supported by the NIH Brain Initiative (grant no. R01 MH111516). L.T. was supported by NIH (grant no. DP2 MH107056). The work of M.D., T.E.H. and R.S.M. was supported by NIH (grant nos. U01 NS094246 and U24 NS109107). R.S.M. also acknowledges support from an NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (grant no. F31NS108593).

Footnotes

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Custom ImageJ macros and MATLAB code used to analyze in vitro and in vivo neuronal imaging data are available upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Extended data is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589–020-00660-y.

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589–020-00660-y.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Greenwald EC, Mehta S & Zhang J. Genetically encoded fluorescent biosensors illuminate the spatiotemporal regulation of signaling networks. Chem. Rev 118, 11707–11794 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Y, Saulnier JL, Yellen G & Sabatini BL A PKA activity sensor for quantitative analysis of endogenous GPCR signaling via 2-photon FRET-FLIM imaging. Front Pharm. 5, 56 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y. et al. Endogenous Gαq-coupled neuromodulator receptors activate protein kinase A. Neuron 96, 1070–1083.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang S & Yasuda R. Imaging ERK and PKA activation in single dendritic spines during structural plasticity. Neuron 93, 1315–1324.e3 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma L. et al. A highly sensitive a-kinase activity reporter for imaging neuromodulatory events in awake mice. Neuron 99, 665–679.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamaguchi T. et al. Role of PKA signaling in D2 receptor-expressing neurons in the core of the nucleus accumbens in aversive learning. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 11383–11388 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castro LRV et al. Striatal neurones have a specific ability to respond to phasic dopamine release. J. Physiol 591, 3197–3214 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yapo C. et al. Detection of phasic dopamine by D1 and D2 striatal medium spiny neurons. J. Physiol 595, 7451–7475 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yagishita S. et al. A critical time window for dopamine actions on the structural plasticity of dendritic spines. Science 345, 1616–1620 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jongbloets BC, Ma L, Mao T & Zhong H. Visualizing protein kinase a activity in head-fixed behaving mice using in vivo two-photon fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy. J. Vis. Exp e59526 10.3791/59526 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta S. et al. Single-fluorophore biosensors for sensitive and multiplexed detection of signalling activities. Nat. Cell Biol 20, 1215–1225 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Depry C, Allen MD & Zhang J. Visualization of PKA activity in plasma membrane microdomains. Mol. Biosyst 7, 52–58 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komatsu N. et al. Development of an optimized backbone of FRET biosensors for kinases and GTPases. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 4647–4656 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tian L. et al. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat. Methods 6, 875–881 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyawaki A. et al. Fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ based on green fluorescent proteins and calmodulin. Nature 388, 882–887 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakai J, Ohkura M & Imoto K. A high signal-to-noise Ca(2+) probe composed of a single green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol 19, 137–141 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hires SA, Zhu Y & Tsien RY Optical measurement of synaptic glutamate spillover and reuptake by linker optimized glutamate sensitive fluorescent reporters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 4411–4416 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinberg SF & Brunton LL Compartmentation of G protein-coupled signaling pathways in cardiac myocytes. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 41, 751–773 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carnegie GK, Means CK & Scott JD A-kinase anchoring proteins: from protein complexes to physiology and disease. IUBMB Life 61, 394–406 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hertel F & Zhang J. Monitoring of post-translational modification dynamics with genetically encoded fluorescent reporters. Biopolymers 101, 180–187 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Surdo NC et al. FRET biosensor uncovers cAMP nano-domains at β-adrenergic targets that dictate precise tuning of cardiac contractility. Nat. Commun 8, 15031 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen MD & Zhang J. Subcellular dynamics of protein kinase A activity visualized by FRET-based reporters. Biochem Biophys. Res Commun 348, 716–721 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding Y. et al. Ratiometric biosensors based on dimerization-dependent fluorescent protein exchange. Nat. Methods 12, 195–198 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao Y. et al. An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators. Science 333, 1888–1891 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qian Y. et al. A genetically encoded near-infrared fluorescent calcium ion indicator. Nat. Methods 16, 171–174 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herbst KJ, Allen MD & Zhang J. Spatiotemporally regulated protein kinase A activity is a critical regulator of growth factor-stimulated extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling in PC12 cells. Mol. Cell Biol 31, 4063–4075 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu V. et al. Illuminating the Onco-GPCRome: novel G protein-coupled receptor-driven oncocrine networks and targets for cancer immunotherapy. J. Biol. Chem 294, 11062–11086 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huganir RL & Nicoll RA AMPARs and synaptic plasticity: the last 25 years. Neuron 80, 704–717 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liao D, Scannevin RH & Huganir R. Activation of silent synapses by rapid activity-dependent synaptic recruitment of AMPA receptors. J. Neurosci 21, 6008–6017 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu W. et al. Activation of synaptic NMDA receptors induces membrane insertion of new AMPA receptors and LTP in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuron 29, 243–254 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dana H. et al. Sensitive red protein calcium indicators for imaging neural activity. eLife 5, e12727 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colgan LA et al. PKCα integrates spatiotemporally distinct Ca2+ and autocrine BDNF signaling to facilitate synaptic plasticity. Nat. Neurosci 21, 1027–1037 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leitz J & Kavalali ET Fast retrieval and autonomous regulation of single spontaneously recycling synaptic vesicles. eLife 3, e03658 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang A-H et al. A trans-synaptic nanocolumn aligns neurotransmitter release to receptors. Nature 536, 210–214 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goto A. et al. Circuit-dependent striatal PKA and ERK signaling underlies rapid behavioral shift in mating reaction of male mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 6718–6723 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paukert M. et al. Norepinephrine controls astroglial responsiveness to local circuit activity. Neuron 82, 1263–1270 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reimer J. et al. Pupil fluctuations track rapid changes in adrenergic and cholinergic activity in cortex. Nat. Commun 7, 13289 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Polack P-O, Friedman J & Golshani P. Cellular mechanisms of brain state-dependent gain modulation in visual cortex. Nat. Neurosci 16, 1331–1339 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fu Y. et al. A cortical circuit for gain control by behavioral state. Cell 156, 1139–1152 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee AM et al. Identification of a brainstem circuit regulating visual cortical state in parallel with locomotion. Neuron 83, 455–466 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDougal DH & Gamlin PD Autonomic control of the eye. Compr. Physiol 5, 439–473 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]