Abstract

Introduction:

The purpose of this study was to quantify and qualify the 3-dimensional (3D) condylar changes using mandibular 3D regional superimposition techniques in adolescent patients with Class II Division 1 malocclusions treated with either a 2-phase or single-phase approach.

Methods:

Twenty patients with Herbst appliances who met the inclusion criteria and had cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) images taken before, 8 weeks after Herbst removal, and after the completion of multibracket appliance treatment constituted the Herbst group. They were compared with 11 subjects with Class II malocclusion who were treated with elastics and multibracket appliances and who had CBCT images taken before and after treatment. Three-dimensional models generated from the CBCT images were registered on the mandible using 3D voxel-based superimposition techniques and analyzed using semitransparent overlays and point-to-point measurements.

Results:

The magnitude of lateral condylar growth during the orthodontic phase (T2-T3) was greater than that during the orthopedic phase (T1-T2) for all condylar fiducials with the exception of the superior condyle (P <0.05). Conversely, posterior condylar growth was greater during the orthopedic phase than the subsequent orthodontic phase for all condylar fiducials (P <0.05). The magnitude of vertical condylar development was similar during both the orthopedic (T1-T2) and orthodontic phases (T2-T3) across all condylar fiducials (P <0.05). Posterior condylar growth during the orthodontic phase (T2-T3) of the 2-phase approach decreased for all condylar fiducials with the exception of the posterior condylar fiducial (P <0.05) when compared with the single-phase approach.

Conclusions:

Two-phase treatment using a Herbst appliance accelerates condylar growth when compared with a single-phase regime with Class II elastics. Whereas the posterior condylar growth manifested primarily during the orthopedic phase, the vertical condylar gains occurred in equal magnitude throughout both phases of the 2-phase treatment regime.

Untreated Class II malocclusions do not appear to be self-corrective at the occlusal level despite favorable skeletal base change.1,2 Nonextraction Class II treatment regimens can generally be divided into either 2-phase treatment, which involves the use of a functional appliance and subsequent multibracket appliances, or alternatively, a single-phase treatment regime, which involves Class II mechanics (ie, Class II elastics) concurrent with fixed appliance therapy.3–6 Two-phase treatment has been associated with an acceleration but not an increase in absolute mandibular length, increased overall treatment times,7 and a relapse of the dentoalveolar movements between phases8 when compared with a treatment protocol that does not involve the use of a functional appliance.

Introduced in 1905 by Emil Herbst, the Herbst appliance is a rigid noncompliant intermaxillary appliance9 designed to keep the mandible in a continuous protrusive position using the maxillary and mandibular dentitions as anchorage units by means of bilateral telescopic arms.10 This continuous “bite jumping” is maintained while still permitting the opening and lateral excursive movements involved with eating or speaking.11,12 Closure of the mouth can only occur with the mandible in a protruded position.13 It has been proposed that this protrusion induces condylar growth stimulation as an adaptive response to the forward positioning of the mandible, with the possibility of some degree of mandibular growth redirection.14

The noncompliant nature of the Herbst appliance and its continuous bite jumping effect make it the ideal clinical model to study the capacities of functional appliances to produce orthopedic change.15–17 One of the main limitations of studies using removable functional appliances has been the role that compliance may play in delivering the therapeutic intervention.18 Compliance with removable functional appliances may also be limited owing to impairment of speech, sleeping patterns, and family relationships while in treatment and may explain why 34% of patients who were given a Twin-block did not complete their functional appliance treatment.19 Conversely, the Herbst appliance approximates what occurs in animal studies because the actual period of intervention is relatively short and compliance factors are eliminated.14,20

The contemporary literature supports that at least in the short- to medium-term (ie, 30 months) there appears to be greater skeletal contribution to the overall degree of sagittal correction in the 2-phase group.21 During the orthopedic phase (T1-T2) with the Herbst appliance, evidence supports that there is 1.6 mm of additional sagittal temporomandibular joint (TMJ) displacement in the Herbst group, with similar amounts of vertical TMJ displacement in both single-phase and 2-phase protocols after the orthodontic phase (T2-T3).22 However, the overall orthopedic contributions to a Class II correction with the 2-phase regime appear to decline and even reverse over time as treated individuals enter late adolescence and beyond.23 There appears to be more similarities than differences in the long-term between single-phase treatment with Class II elastic use and 2-phase treatment with the Herbst appliance.24 Thus, the main benefit of the Herbst appliance from a cephalometric perspective may simply be stated as “you get the growth when you need it” in subjects with Class II malocclusions.25 The acceleration of mandibular growth after continuous bite jumping during the orthopedic phase is believed to allow for approximately equal continued maxillary and mandibular growth during the subsequent orthodontic phase, with the dentoalveolar Class II correction maintained by subsequent interdigitation.26

Lateral cephalometric studies are limited for assessing the magnitude of condylar changes owing to projection error and difficulties in landmark identification,27 especially when changes are small.28 Methods that seek to minimize the errors associated with landmark identification22,29,30 are associated with superimposition errors, which tend to be exaggerated in the condylar area31 and fail to distinguish the contributions of condylar change from physiological32 and/or therapeutic glenoid fossa changes.33 Furthermore, reference frame orientation affects the perceived direction of condylar change, which can affect mandibular projection29 owing to its relationship to mandibular growth rotation.34–36 Although the Pancherz analysis37 has been used widely in the contemporary 2-dimensional (2D) lateral cephalometric literature, it may not be a valid38 means of describing condylar growth changes in the overall dentofacial complex owing to its reliance on the mandibular occlusal plane of the initial radio-graph.29 Lateral cephalometric studies also cannot differentiate temporary displacement of the mandible from true mandibular growth.39,40

Recently, Souki et al41 were able to demonstrate the use of cone-beam computer tomography (CBCT) and mandibular voxel-based 3-dimensional (3D) regional superimpositions in growing adolescents, during the active period of Herbst appliance treatment with comparisons with matched untreated controls using a common 3D reference frame.42 Although there have been some initial forays into the determination of condylar changes that occur during the initial orthopedic phase (T1-T2) of 2-phase treatment, there has been no 3D quantification of these condylar changes in the orthodontic phase (T2-T3) of 2-phase treatment or in single-phase treatment with Class II elastics (T1-T2).

The goals of this study were to quantify and qualify the 3D condylar changes during the initial orthopedic phase (T1-T2) with the Herbst appliance and subsequent orthodontic phase (T2-T3) of a 2-phase treatment regime for adolescents’ Class II Division 1 malocclusions, with the 2-phase treatment regime with the Herbst appliance (T1-T3) compared with a group of matched subjects treated with Class II elastics in a single-phase treatment protocol (T1-T2) using mandibular 3D regional superimposition techniques.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Ethics approval for this retrospective study was obtained from the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 1647867). All subjects who were treated with a 2-phase treatment regime with the Herbst appliance were sourced from the office of a specialist orthodontist from Geelong, Australia. The subjects were selected by searching the practice database for an item code denoting Herbst appliance insertion. The consent to the use of records was taken in accordance with the Victorian Health Records Act 2001 and Federal Privacy Act 1988 when the subjects started their course of orthopedic and/or orthodontic treatment.

A sample size calculation completed using G*Power version 3.1.9243 determined the following for comparisons of condylar effects during the initial orthopedic (T1-T2) and subsequent orthodontic (T2-T3) phases:

Nine subjects would provide 80% statistical power in detecting a 1-mm difference in a posterior direction for the posterior condylar fiducial assuming a standard deviation of 0.87 mm and a significance level of P <0.05 using values obtained by Souki et al41 during the active period of Herbst appliance treatment and a paired 2-sided t test with the null hypothesis of no statistically significant difference in the magnitude of posterior condylar growth during the orthopedic and orthodontic phases of a 2-phase treatment regime.

Ten subjects would provide 80% statistical power in detecting a 1-mm difference in the superior direction for the superior condylar fiducial assuming a standard deviation of 0.99 mm and a significance level of P <0.05 using a paired 2-sided t test with a null hypothesis of no statistically significant differences in the magnitude of vertical condylar growth during the orthopedic and orthodontic phases using values obtained by Souki et al41 during the active period of Herbst appliance treatment.

The Herbst sample consisted of 20 consecutively treated subjects who completed a 2-phase regime using a Herbst appliance that consisted of stainless steel crowns fitted to the maxillary and mandibular first permanent molars, with a cantilevered arm extended forward from the mandibular first molar to the level of the mandibular first premolar. The maxillary framework incorporated a Hyrax expansion screw to accommodate the advancement of the mandibular arch, whereas a well-adapted 0.040-inch stainless steel lingual arch connected the left and right mandibular molars. The lower framework also featured occlusal rests on the mandibular first premolars or second primary molars. Activation of the appliance involved an initial activation of 5 mm with subsequent 2-mm activations to bring the incisors into an overcorrected edge-to-edge position. If there was insufficient overjet to achieve the desired amount of mandibular advancement, then a preorthopedic phase incorporating limited fixed appliances was commenced before the start of Herbst appliance treatment. CBCT scans were taken before the start of treatment (T1), 8 weeks after removal of the Herbst appliance (T2), and when the multibracket appliances were removed (T3). The mean age for the subjects with Herbst appliances for the initial radiograph was 12.76 ± 0.89 years. The activation of the Herbst appliance started an average of 3.09 ± 1.87 months after the initial radiograph, at an average age of 13.01 ± 0.86 years. The mean treatment time for the orthopedic phase with the Herbst appliance was 7.79 ± 1.82 months, and the orthodontic phase was 22.08 ± 3.69 months for a total treatment time of 29.87 ± 4.56 months.

The single-phase Class II elastics group consisted of 11 de-identified, matched subjects with Class II malocclusions with pretreatment (T1) and posttreatment (T2) CBCT scans obtained from collections at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC; the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minn; and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. The average age of the Class II elastics group at the initial radiograph was 13.52 ± 0.97 years, and these subjects were treated over a period of 22.97 ± 9.24 months.

Subjects in both 2-phase and single-phase regimes were restricted to adolescents presenting with Class II skeletal (ANB >4°) and dental (bilateral Class II molar relationships >4 mm) relationships who were treated near peak pubertal growth as established by cervical vertebral maturation (CVM) between stages 3 and 4.44 Subjects were excluded if there was any history of early orthodontic treatment other than limited fixed appliances to provide sufficient overjet for Herbst activation, craniofacial syndrome, or incomplete pre- and posttreatment records, which included 1 or more condyles outside of the field of view at any time point.

All CBCT scans used in this study were taken using an i-CAT machine (Imaging Sciences International, Hat-field, Pa) with a 16 × 22 cm field of view and patients in maximum intercuspation. De-identification and downsizing of the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine scans to 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5-mm voxel sizes were achieved using Slicer CMF (version 3.1, www.slicer.org) and conversion to the gipl.gz file format to decrease computational time for the eventual 3D voxel-based mandibular superimposition stage.45 Slicer CMF was then employed to perform head orientation of T1 surface models generated following an automated thresholding algorithm to generate full-skull models by means of the intensity segmenter and model maker modules. The transforms module was then used to align the Frankfort horizontal, midsagittal, and transporionic planes to match the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes of the T1 skull surface models.46 This step ensured that all T1 mandibles were placed in a common coordinate system within the Slicer software as described by Ruellas et al42 for subsequent vectorial descriptions of condylar direction.

X: medial-lateral

Y: anterior-posterior

Z: superior-inferior

The 3D volumetric models of the mandible were subsequently segmented in ITK-SNAP (version 3.6; open-source software, http://www.itksnap.org) with refinements to the Slicer CMF segmentation by means of the active contour and adaptive segmentation tools available in ITK-SNAP. These refined mandibular segmentations were converted subsequently into 3D surface models using the model maker module within Slicer CMF to produce T1, T2, and T3 surface models.45,46

Manual approximation of T2 and T3 CBCTs and segmentations onto the T1 mandible were performed by means of cross-sectional views in all 3 planes of space, in Slicer CMF using the transforms module with the aim of decreasing subsequent computational time. Regions of interest (masks) on the T2 and T3 mandibular segmentations were then identified on the approximate T2 and T3 segmentations in ITK-SNAP. The masks are used to define the stable regions of superimposition for the mandibular body voxel-based image registration as seen in Supplementary Figure 1.46 A fully-automated voxel-based growing mandibular superimposition was then performed using the growing registration module in Slicer CMF to generate a matrix that allowed for subsequent superimposition of the T2 and T3 mandibular surface models onto the original T1 mandibular surface model.41,46

Manual landmark identification then occurred with 3 open windows of ITK-SNAP to visualize all 2 (Class II elastics) or 3 (Herbst) mandibular time points simultaneously in 3D space. The axial, coronal, and sagittal views of the original gray scale images recreated by multiplanar reconstruction and the 3D volumetric model were used in landmark placement.41,47 Fivecondylar landmarks as seen in Supplementary Figure 2 were placed on each condyle, which could subsequently be identified using the Q3DC tool in Slicer CMF to allow for comparisons with the work by Souki et al.41 Quantification of point-to-point linear distance was performed using the mesh statistics tool in Slicer CMF for each plane of 3D space.41,47 Condylar changes subsequently could be visualized by semitransparency overlays of the T1, T2, and T3 mandibular surface models.41,45,46

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed with Excel (Microsoft, version 16.13.1, Redmond, Wash) and MATLAB (Math-works, version 9.1.0.441655, Natick, Mass). Means, standard deviations, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for all subjects. Statistical differences were assessed using paired t tests for intragroup differences between the orthopedic and orthodontic phases in the Herbst subjects and unpaired t tests for overall condylar changes between the 2-phase and single-phase regimes. Manual landmark placement and subsequent Q3DC linear measures were conducted using Slicer CMF 3.1.41,47

The reliability of intraobserver manual landmark placement error was assessed with the placement of the 5 condylar fiducials on 5 separate days with linear distances assessed using the Q3DC tool (Supplementary Table I). A Bland-Altman plot was performed for the Q3DC, and the mesh statistics tool of the same manual landmarks can be seen in Supplementary Figure 3.

RESULTS

The descriptive statistics comparing the Herbst and Class II elastics groups are summarized in Table I from the 2D cephalometry generated from the CBCTs. The 2 groups were well matched for age, duration in multibracket appliances, ramus length, and divergency before the start of treatment. There were significant differences between the 2 groups, with an increased total duration of treatment in the Herbst and multibracket group compared with the Class II elastics group (respectively, 29.87 ± 4.56 months and 22.97 ± 9.24 months). At T1, the Herbst group also presented with greater mandibular retrognathism, shorter effective mandibular length and corpus length, and a greater ANB than the Class II elastics group (respectively, CoGn 112.06 ± 4.78 mm and 116.54 ± 6.07 mm, GoPg 79.68 ± 4.69 mm and 82.47 ± 3.20 mm, ANB 6.27° ± 1.87° and 3.32° ± 2.14°).

Table I.

Demographics and statistical comparison for the 2-phase (Herbst and multibracket appliances) and 1-phase (Class II elastics) subjects

| Herbst and multibracket appliances | Class II elastics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P value |

| Age, y | 13.01 | 0.86 | 13.52 | 0.97 | 0.167 |

| Sex | 6 males | 14 females | 4 males | 7 females | N/A |

| Orthopedic phase, mo | 7.79 | 1.82 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Orthodontic phase, mo | 22.08 | 3.69 | 22.98 | 9.24 | 0.375 |

| Total duration, mo | 29.87 | 4.56 | 22.98 | 9.24 | 0.037* |

| Effective mandibular length CoGn, mm | 112.06 | 4.78 | 116.54 | 6.07 | 0.005* |

| Ramus length CoGo, mm | 51.22 | 3.80 | 52.79 | 3.90 | 0.133 |

| Corpus length GoPg, mm | 79.68 | 4.69 | 82.47 | 3.20 | 0.008* |

| FMPA, o | 22.38 | 5.27 | 23.99 | 4.67 | 0.389 |

| ANB, o | 6.27 | 1.87 | 3.32 | 2.14 | 0.001* |

N/A, not applicable.

Statistically significant at P <0.05 based on a 2-tailed independent Student t test.

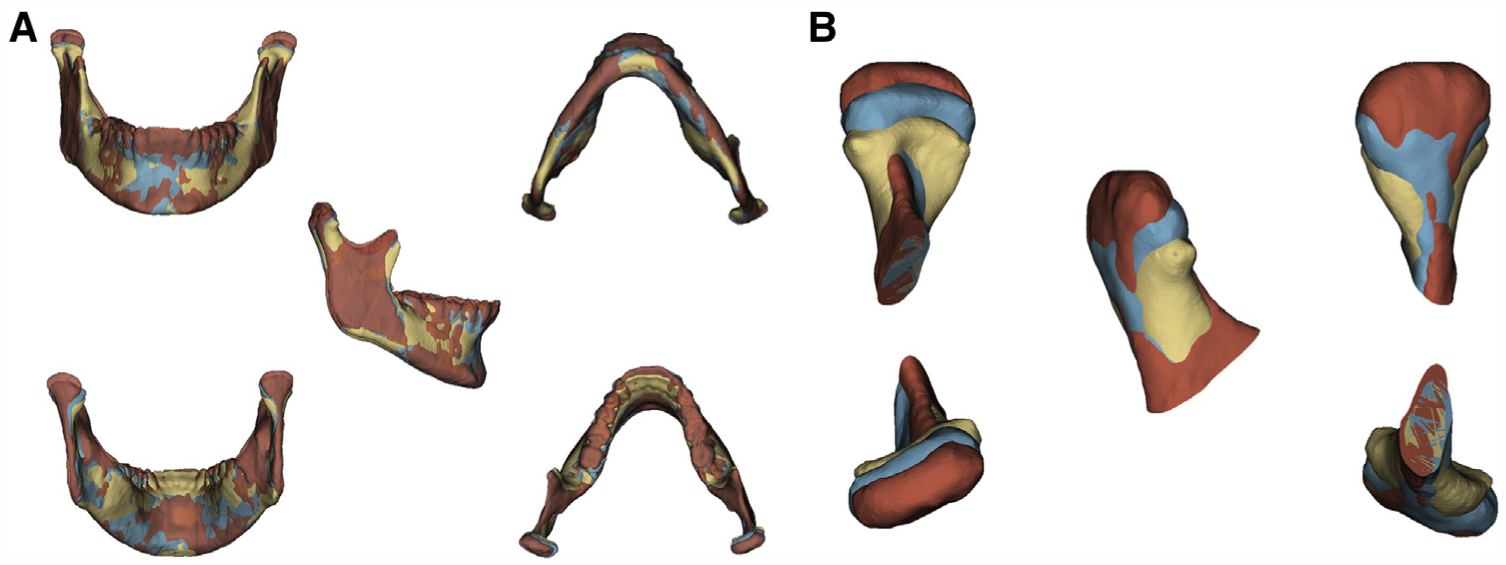

The condylar fiducials featured in this study can be seen in Supplementary Figure 2 on 1 of the mandibles used in this study. The semitransparent overlays of the T1, T2, and T3 mandibular superimpositions for 1 representative subject from the Herbst and multibracket appliances groups are shown in Figures 1, A and B.

Fig 1.

Superimposed mandibles (A) and close-ups of the right condyle (B) for one of the 2-phase Herbst and multibracket appliances subjects at timepoints T1 (yellow), T2 (blue) and T3 (red).

Right- and left-side condylar changes appeared to be symmetrical throughout all time points in the Herbst group and the Class II elastics group, with no statistically significant differences (P >0.05) between the contralateral condyles, and as such they were combined. This allowed us to treat contralateral condyles as a single group for subsequent intra- and intergroup comparisons.

The means, standard deviations, and 95% confidence intervals for the condylar changes occurring in the Herbst and multibracket appliances groups through the 2-phases and the overall Herbst and multibracket appliances in comparison with the Class II elastics group, can be seen in Tables II and III. Linear distances of condylar fiducial changes during the orthopedic phases (T1-T2) found by Souki et al,41 who studied the effect of a 1-step activation Herbst in 25 subjects over a period of 7.9 ± 0.4 months are also presented in Table II.

Table II.

Combined condylar changes for the orthopedic (T1-T2) and orthodontic (T2-T3) phases in a 2-phase treatment regime with the Herbst appliance and multibracket appliances with a comparison with the findings of Souki et al41

| Orthopedic phase (T1-T2) | Souki et al41 group (T1-T2) | Orthodontic phase (T2-T3) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROI | Coordinates | Mean | SD | 95% CI | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | 95% CI | ||

| Condyle superior | X | 0.28 | 0.72 | 0.05 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.82 | 0.29 | 0.81 |

| Y | 1.64 | 1.12 | 1.28 | 2.00 | 1.90 | 1.07 | 0.04 | 1.13 | −0.33 | 0.40 | |

| Z | 2.97 | 1.87 | 2.37 | 3.57 | 2.58 | 0.99 | 2.99 | 1.89 | 2.39 | 3.60 | |

| 3D | 3.86 | 1.37 | 3.42 | 4.30 | 3.45 | 1.20 | 3.45 | 1.69 | 2.91 | 3.99 | |

| Condyle lateral | X | 0.34 | 0.71 | 0.11 | 0.57 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.95 | 0.78 | 0.70 | 1.20 |

| Y | 1.12 | 1.05 | 0.78 | 1.46 | 0.96 | 0.59 | 0.20 | 1.08 | −0.15 | 0.55 | |

| Z | 2.74 | 1.68 | 2.21 | 3.28 | 2.40 | 1.19 | 2.79 | 1.85 | 2.20 | 3.38 | |

| 3D | 3.26 | 1.62 | 2.75 | 3.78 | 2.28 | 1.06 | 3.31 | 1.71 | 2.76 | 3.86 | |

| Condyle medial | X | 0.19 | 0.67 | −0.02 | 0.40 | 0.91 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.42 | 0.93 |

| Y | 1.86 | 1.17 | 1.49 | 2.23 | 2.27 | 1.44 | 0.45 | 1.08 | 0.11 | 0.80 | |

| Z | 2.67 | 1.62 | 2.15 | 3.19 | 1.80 | 0.79 | 3.14 | 2.10 | 2.46 | 3.81 | |

| 3D | 3.60 | 1.42 | 3.15 | 4.06 | 2.30 | 1.39 | 3.68 | 1.76 | 3.12 | 4.24 | |

| Condyle anterior | X | 0.21 | 0.73 | −0.03 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.72 | 0.86 | 0.44 | 0.99 |

| Y | 1.62 | 1.04 | 1.29 | 1.96 | 1.85 | 1.13 | 0.27 | 1.12 | −0.08 | 0.63 | |

| Z | 2.95 | 1.78 | 2.38 | 3.52 | 1.81 | 0.98 | 2.70 | 1.83 | 2.12 | 3.29 | |

| 3D | 3.74 | 1.43 | 3.29 | 4.20 | 2.70 | 1.21 | 3.24 | 1.64 | 2.72 | 3.76 | |

| Condyle posterior | X | 0.38 | 0.79 | 0.12 | 0.63 | 1.25 | 0.88 | 0.74 | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.94 |

| Y | 1.52 | 0.99 | 1.20 | 1.84 | 1.20 | 0.87 | 0.45 | 0.98 | 0.14 | 0.77 | |

| Z | 2.60 | 1.88 | 2.00 | 3.20 | 2.26 | 0.85 | 2.91 | 1.92 | 2.29 | 3.52 | |

| 3D | 3.50 | 1.43 | 3.05 | 3.96 | 2.75 | 1.20 | 3.38 | 1.65 | 2.86 | 3.91 | |

ROI, mm; SD, standard deviation; X, medial-lateral; Y, anterior-posterior; Z, superior-inferior; 3D, 3D Euclidean distance.

(+): lateral, posterior, and superior; all measurements are positive unless otherwise noted to represent directionality.

Table III.

Combined condylar changes for a 2-phase treatment regime with the Herbst appliance and multibracket appliances (T1-T3) and the single-phase Class II elastics group (T1-T2)

| Herbst and multibracket appliances (T1-T3) | Class II elastics (T1-T2) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROI | Coordinates | Mean | SD | 95% CI | Mean | SD | 95% CI | ||

| Condyle superior | X | 0.82 | 0.95 | 0.52 | 1.13 | 1.17 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 1.54 |

| Y | 1.68 | 1.44 | 1.22 | 2.14 | 0.99 | 1.25 | 0.43 | 1.54 | |

| Z | 5.97 | 3.04 | 5.00 | 6.94 | 3.70 | 2.48 | 2.60 | 4.80 | |

| 3D | 6.69 | 2.52 | 5.89 | 7.50 | 4.21 | 2.56 | 3.08 | 5.35 | |

| Condyle lateral | X | 1.29 | 0.80 | 1.03 | 1.54 | 1.21 | 1.48 | 0.56 | 1.87 |

| Y | 1.32 | 1.54 | 0.83 | 1.81 | 0.95 | 1.36 | 0.35 | 1.56 | |

| Z | 5.53 | 2.67 | 4.68 | 6.39 | 3.22 | 2.69 | 2.02 | 4.41 | |

| 3D | 6.04 | 2.77 | 5.15 | 6.92 | 3.78 | 3.10 | 2.41 | 5.16 | |

| Condyle medial | X | 0.86 | 0.96 | 0.56 | 1.17 | 0.68 | 0.98 | 0.24 | 1.11 |

| Y | 2.32 | 1.25 | 1.91 | 2.72 | 1.19 | 1.39 | 0.58 | 1.81 | |

| Z | 5.81 | 2.90 | 4.88 | 6.73 | 3.75 | 2.81 | 2.50 | 4.99 | |

| 3D | 6.75 | 2.22 | 6.04 | 7.46 | 4.30 | 2.84 | 3.04 | 5.56 | |

| Condyle anterior | X | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.64 | 1.21 | 1.15 | 0.92 | 0.75 | 1.56 |

| Y | 1.90 | 1.18 | 1.52 | 2.27 | 1.09 | 1.15 | 0.58 | 1.60 | |

| Z | 5.65 | 2.86 | 4.74 | 6.57 | 3.35 | 2.22 | 2.36 | 4.33 | |

| 3D | 6.39 | 2.42 | 5.61 | 7.16 | 3.94 | 2.28 | 2.93 | 4.95 | |

| Condyle posterior | X | 1.12 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 1.40 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.50 | 1.29 |

| Y | 1.97 | 1.23 | 1.58 | 2.37 | 1.01 | 1.53 | 0.33 | 1.69 | |

| Z | 5.51 | 2.94 | 4.57 | 6.45 | 3.36 | 2.85 | 2.10 | 4.63 | |

| 3D | 6.30 | 2.58 | 5.47 | 7.12 | 3.93 | 2.97 | 2.62 | 5.25 | |

ROI, mm; SD, standard deviation; X, medial-lateral; Y, anterior-posterior; Z, superior-inferior; 3D, 3D Euclidean distance.

(+): lateral, posterior, and superior; all measurements are positive unless otherwise noted to represent directionality.

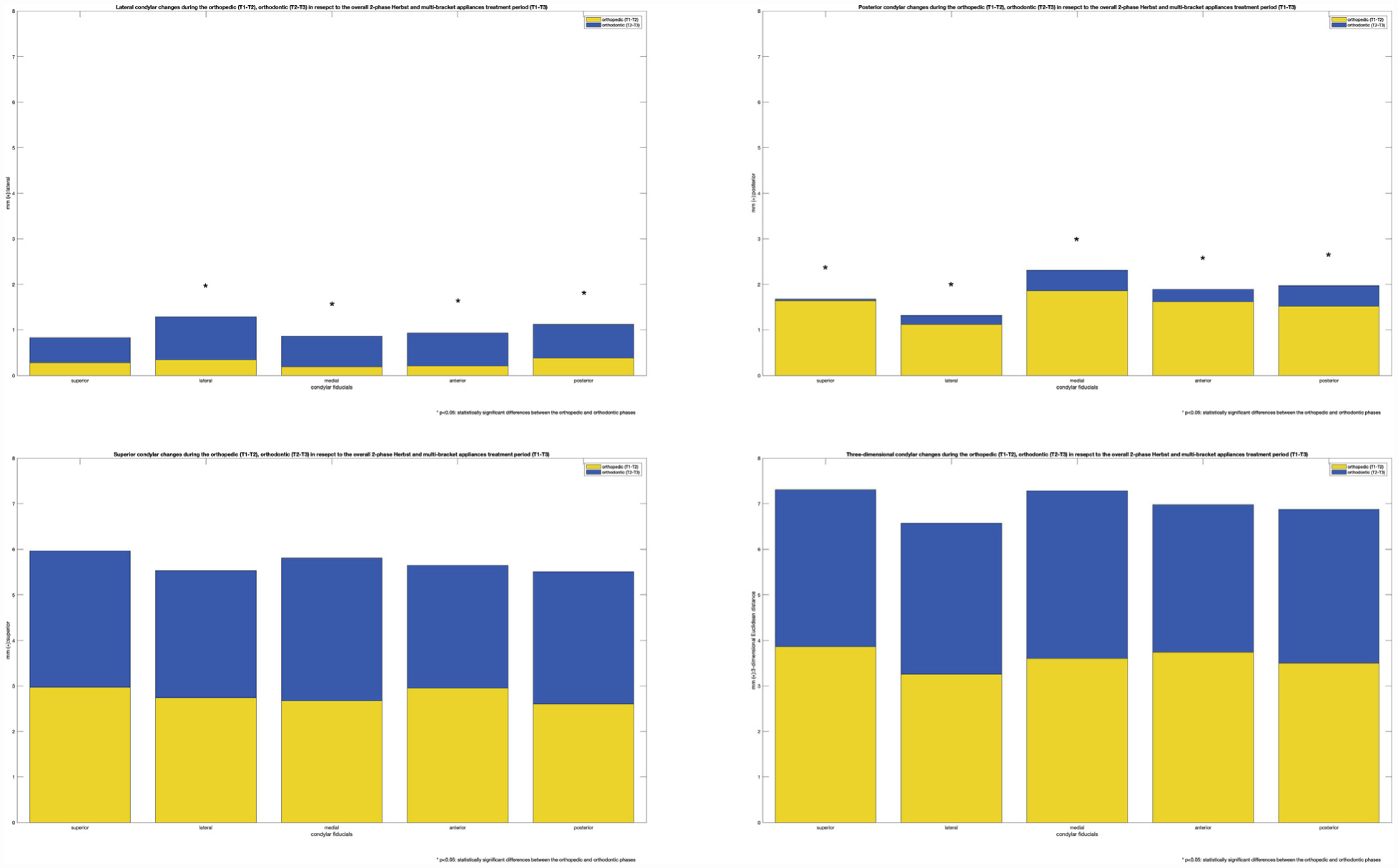

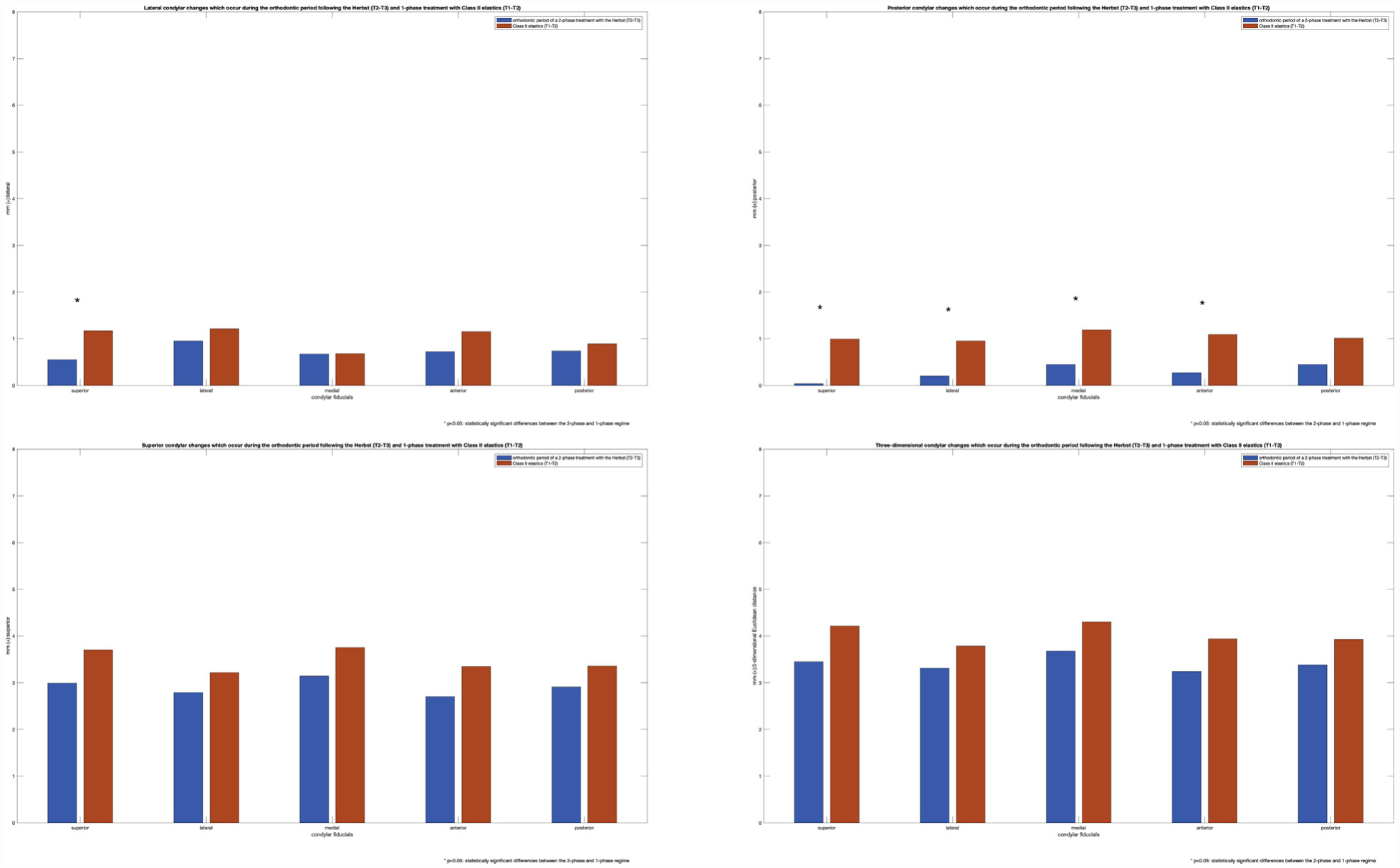

Intragroup comparisons of condylar growth magnitudes between the orthopedic (T1-T2) and orthodontic phases (T2-T3) in the overall Herbst and multibracket treatments (T1-T3) are shown in Supplementary Table II and illustrated through a series of stacked bar plots in Figure 2. Comparisons between the 2 treatment periods within the 2-phase regime suggested that the magnitude of lateral condylar development appears to be greater during the orthodontic phase (T2-T3) than the initial orthopedic phase (T1-T2) for all condylar fiducials with the exception of the superior condylar fiducial (P <0.05). Conversely, posterior condylar development appeared to be greater during the orthopedic phase (T1-T2) than the subsequent orthodontic phase (T2-T3) for all condylar fiducials (P <0.05). The magnitude of vertical condylar development appeared to be similar during both the orthopedic (T1-T2) and orthodontic phases (T2-T3) across all condylar fiducials (P <0.05).

Fig 2.

Lateral, posterior, vertical and 3D Euclidean condylar changes during the orthopedic (T1-T2) and orthodontic (T2-T3) phases in respect to the overall 2-phase treatment regime (T1-T3).

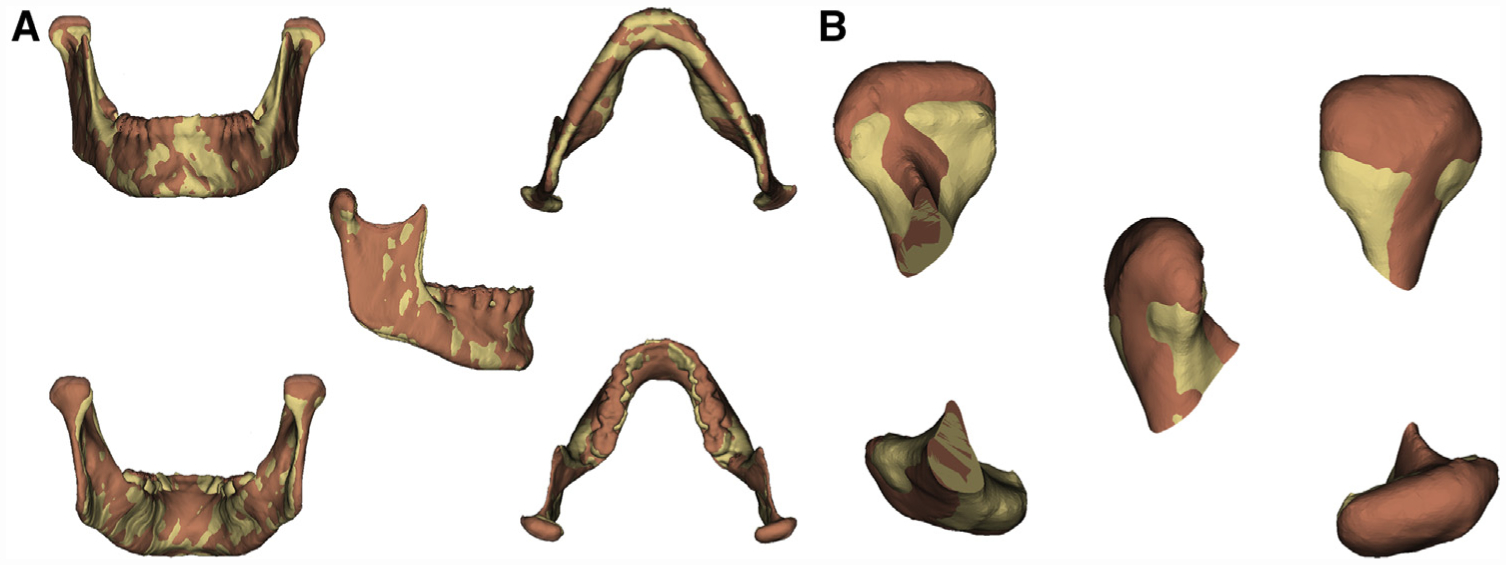

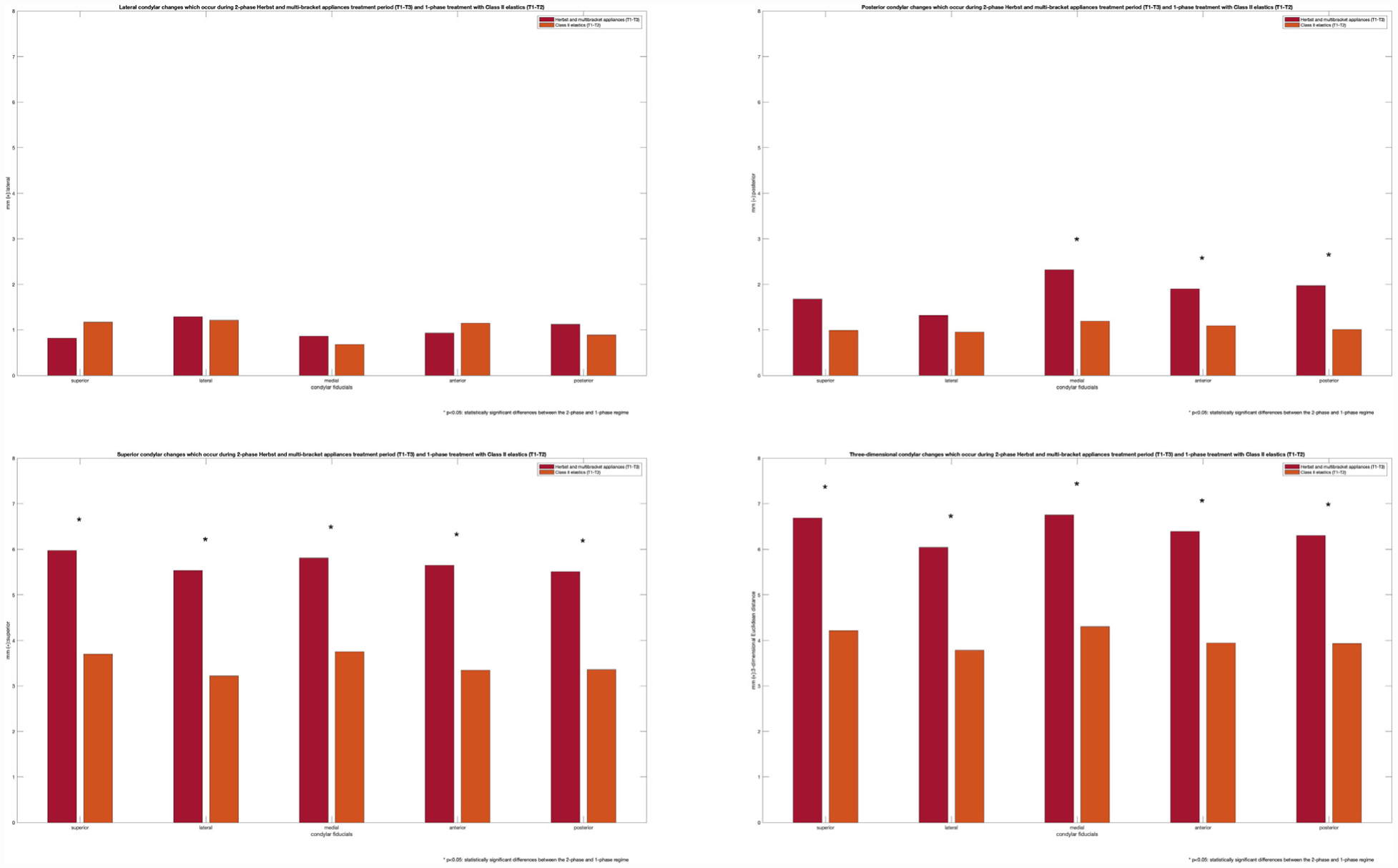

Semitransparent overlays of the T1, T2 mandibular superimpositions for 1 representative subject in the Class II elastics group are shown in Figures 3, A and B. Intergroup comparisons between the overall 2-phase Herbst and multibracket appliances (T1-T3) and the matched single-phase Class II elastics group (T1-T2) are explored in Supplementary Table III and described by the series of bar plots in Figure 4. There did not appear to be any difference between the magnitude of lateral condylar development between the 2 treatment regimens (P >0.05). This study showed an additional 0.96 mm of posterior condylar growth at the posterior condylar fiducial (P <0.05) and 2.27 mm of vertical condylar growth at the superior condylar fiducial (P <0.05) when the 2-phase regime was compared with the single-phase regime as seen in Table IV.

Fig 3.

Superimposed mandibles (A) and close-ups of the right condyle (B) for one of the single-phase Class II elastics subjects at timepoint T1 (yellow) and T2 (orange).

Fig 4.

Lateral, posterior, vertical and 3D Euclidean condylar changes occuring during the 2-phase treatment regime (T1-T3) and single-phase treatment (T1-T2).

Table IV.

The additional condylar change found in the 2-phase treatment regime (T1-T3) when compared with single-phase treatment (T1-T2)

| Additional condylar gain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROI | Coordinates | Mean | % fold-change | P value |

| Condyle superior | X | −0.34 | −29.37 | 0.147 |

| Y | 0.69 | 70.31 | 0.053 | |

| Z | 2.27 | 61.29 | 0.003* | |

| 3D | 2.48 | 58.90 | 0.001* | |

| Condyle lateral | X | 0.08 | 6.30 | 0.824 |

| Y | 0.37 | 38.58 | 0.338 | |

| Z | 2.32 | 72.15 | 0.002* | |

| 3D | 2.25 | 59.49 | 0.007* | |

| Condyle medial | X | 0.19 | 27.52 | 0.476 |

| Y | 1.12 | 93.95 | 0.003* | |

| Z | 2.06 | 54.93 | 0.009* | |

| 3D | 2.45 | 57.06 | 0.001* | |

| Condyle anterior | X | −0.23 | −19.65 | 0.353 |

| Y | 0.80 | 73.34 | 0.012* | |

| Z | 2.31 | 68.96 | 0.001* | |

| 3D | 2.44 | 61.95 | 0.000* | |

| Condyle posterior | X | 0.22 | 24.81 | 0.356 |

| Y | 0.96 | 95.68 | 0.016* | |

| Z | 2.14 | 63.67 | 0.007* | |

| 3D | 2.36 | 60.08 | 0.003* | |

ROI, mm; X, medial-lateral; Y, anterior-posterior; Z, superior-inferior; 3D, 3D Euclidean distance.

(+): lateral, posterior, and superior; all measurements are positive unless otherwise noted to represent directionality.

Statistically significant at P <0.05 based on a 2-tailed independent Student t test.

Comparisons of condylar changes during the orthodontic phase of the 2-phase regime (T2-T3) with the matched single-phase Class II elastics group (T1-T2) are explored in Supplementary Table IV and described by the series of bar plots in Figure 5. A decrease in the amount of posterior condylar growth was found for all condylar fiducials with the exception of the posterior condylar fiducial (P <0.05) after the use of the Herbst appliance. Overall, there appeared to be a trend toward decreased condylar growth magnitude after removal of the Herbst appliance in the 2-phase regime, although this did not reach statistical significance. A decrease in the lateral condylar change at the superior condylar fiducial was also observed (P <0.05).

Fig 5.

Lateral, posterior, vertical and 3D Euclidean condylar changes during the orthodontic phase of 2-phase treatment regime (T2-T3) and single-phase treatment with Class II elastics (T1-T2).

DISCUSSION

Condylar growth remodeling is an important developmental process that contributes to the mandibular position and thus chin projection.48 This study investigated condylar remodeling in both treatment regimens and during each phase of the 2-phase treatment regime. Both the remodeling of the glenoid fossa and the positional changes of the condyle within the glenoid fossa have been described previously by Atresh et al49 in 16 of 20 subjects with Herbst appliances and the entirety of the Class II elastics sample used in this study. Together, these 2 studies have explored the 3 adaptive processes in the TMJ thought to contribute to mandibular position and thus chin projection,48 using 3D methods.

The results of this 3D CBCT study indicate that significant condylar gains do occur with the use of the Herbst appliance compared with those found when subjects are treated solely with Class II elastics, and these condylar changes persist to the end of active orthodontic treatment. The only comparable study on the magnitudes and direction of condylar growth described in this article would be that of Souki et al,41 who assessed condylar remodeling during the Herbst phase. The use of 5 individual landmarks on each condyle, denoting the superior, lateral, medial, anterior, and posterior condyle, also may be a more anatomically valid means to represent the condylar changes as opposed to using a singular condylion landmark.50

One-step mandibular activation of a cantilever Herbst appliance produced approximately 1.0–2.3 mm of posterior condylar growth and 1.8–2.6 mm of vertical condylar growth over an average period of 7.9 ± 0.4 months.41 In the present study, we observed 1.1–1.9 mm of posterior condylar growth and 2.7–3.0 mm of superior condylar growth during the orthopedic phase (T1-T2) over a period of 7.79 ± 1.82 months. The present results of the orthopedic phase are comparable to findings by Souki et al,41 as well as a previous lateral cephalometric study by Pancherz and Fischer,33 which reported an average of 1.8 mm of posterior condylar growth and 2.9 mm of vertical condylar growth subsequent to 7.5 months of active Herbst appliance treatment.

The novel contributions of the present study are 2-fold. This is the first study to reveal the magnitude and direction of condylar growth during the subsequent orthodontic phase (T2-T3) using CBCT. The present study also elucidates the magnitude and direction condylar of growth remodeling during single-phase orthodontic treatment with Class II elastics. The magnitude of condylar growth during the orthodontic phase after orthopedic treatment is minimal in a posterior direction, whereas marked vertical condylar growth continues. The present study found minimal posterior condylar growth ranging from 0.14 to 0.77 mm and continued vertical condylar growth of 2.39 to 3.6 mm during the subsequent orthodontic phase after the initial orthopedic phase with the Herbst appliance. Thus, most of the sagittal condylar growth in a 2-phase treatment regime with the Herbst appliance and subsequent multibracket appliances occurs during the orthopedic phase (T1-T2) with minimal contributions during the subsequent orthodontic phase (T2-T3). Conversely, the amount of vertical condylar development is approximately equivalent throughout the 2 treatment periods. These findings support previous lateral cephalometric studies that demonstrated more posteriorly directed condylar growth direction and a greater magnitude of growth during the Herbst phase; after the Herbst phase, there was a more vertically redirected condylar growth pattern with22 or without29,33 the use of multibracket appliances.

Previous 2D lateral cephalometric work also suggested differences in condylar growth expression during and subsequent to Herbst appliance treatment in various vertical facial patterns.30 Although an attempt to study the effects of vertical facial pattern on the direction of condylar growth during the orthopedic phase (T1-T2) and orthodontic phase (T2-T3) was attempted, the variance present in the orthopedic condylar changes measured suggested that subgroup analysis would have been unlikely to produce sufficient power to detect statistically significant differences in condylar growth direction. A post-hoc power analysis suggests that to achieve 80% statistical power with a significance level of P <0.05 in detecting a 1-mm difference in condylar growth direction between vertical facial patterns during the orthodontic phase (T2-T3), a sample size of 22 subjects and 71 subjects in each divergency group would be required for the sagittal and vertical directions.

In the present study, the magnitudes of condylar growth during single-phase Class II treatment using Class II elastics were determined to be approximately 1.01 ± 1.53 mm of posterior and 3.70 ± 2.48 mm of vertical condylar growth over a treatment period of 22.81 ± 8.69 months. The previous studies of Atresh et al49 and LeCornu et al51 reported only overall condylar and chin displacements relative to anterior cranial base superimpositions for 2-phase with Herbst compared with single-phase orthodontic treatment with Class II elastics. To our knowledge, there are no studies in the literature that have reported the condylar growth remodeling changes that occur throughout a single-phase treatment regime with Class II elastics (T1-T2) using a 3D voxel-based mandibular superimposition technique. The findings presented here may serve as a useful reference for subsequent investigations into condylar growth in growing subjects with Class II malocclusions.

When condylar changes between treatment regimens were compared, the 2-phase treatment regime with the Herbst appliance (T1-T3) produced greater condylar remodeling effects than the Class II elastics group (T1-T2). There appears to be an additional 0.96 mm of posterior condylar growth at the posterior condylar fiducial (P <0.05) and 2.27 mm of vertical condylar growth at the superior condylar fiducial (P <0.05). The results of the present study differ from the 2D cephalometric findings of Serbesis-Tsarudis and Pancherz22 that suggested a therapeutic condylar gain of 1.6 mm in the sagittal direction, with no vertical condylar gains when 2-phase Herbst treatment was compared with the use of Class II elastics in a single-phase treatment plan. Such differences between studies may reflect differences in the superimposition technique, 2D vs 3D imaging, the landmarks used, and the reference plane from which the condylar growth direction was measured. Whereas the aforementioned landmarks are representative of most clinically significant surfaces of the condyle, in the present study, the small and variable amount of posterior condylar growth at the lateral and superior condylar surfaces were not statistically significant between the 2-phase and single-phase treatment regimes.

Although these additional condylar changes appear small in magnitude, the 2-phase approach with Herbst and subsequent multibracket appliances produces posterior and vertical condylar growth of 1.97 ± 1.23 mm and 5.97 ± 3.04 mm, respectively. This amounted to an enhancement of condylar growth by 95.7% in the posterior and 61.3% in the vertical direction with an average increase in treatment time of 7.79 ± 1.82 months when compared with single-phase treatment. The present findings support the notion that, at least in the short- to medium-term, the use of a 2-phase treatment regime with the Herbst appliance allows one to “get the growth when you need it” in the region of the condyle, and the condylar changes that are established during the active Herbst appliance phase persist to the end of active orthodontic treatment.25 However, this must be reconciled with what appears to be no statistically significant differences in chin projection when 2-phase treatment with the Herbst appliance was compared with a single-phase treatment with Class II elastics.49 The disappearance of the gains in chin projection in the order of 1.5 mm during the initial orthopedic phase (T1-T2) with a Herbst appliance over untreated Class II controls is perplexing given the condylar gains seen in this study.41 Whereas a pilot study by LeCornu et al51 suggested that 1 of the therapeutic effects of the Herbst appliance during the orthopedic phase (T1-T2) may be anterior glenoid fossa remodeling, Atresh et al49 reported that the glenoid fossa remodels posteriorly in both the orthopedic (T1-T2) and orthodontic (T2-T3) phases. Furthermore, the condyle-fossa relationship remains relatively constant throughout, and thus the TMJ complex appears to be displaced posteriorly as a unit throughout treatment for patients treated with the Herbst appliance or Class II elastics.49

An expected increase in chin projection as a result of the favorable condylar growth demonstrated in this study with the Herbst appliance may be obscured by vertical dentoalveolar changes or vertical maxillary growth.52 Furthermore, anterior mandibular displacement to an edge-to-edge construction bite creates a transient increase in lower anterior facial height and steepening of the mandibular plane. One hypothesis is that the additional condylar growth in the 2-phase treatment regime may contribute to the maintenance of facial divergence throughout the orthopedic phase. A future 3D superimposition study of the same subjects to assess the vertical maxillary growth, as well as the maxillary and mandibular dentoalveolar changes, may clarify these effects.

However, there are limitations to this retrospective CBCT study. Only 2 of the 3 possible sources of methodological error in this study were able to be tested. These included errors in landmark placement of the 5 condylar fiducials, as well as measurement errors associated with Euclidean distance calculation. The latter increases in importance when the magnitudes of linear measures are small, such as those found in the present study.28 Using the Bland-Altman plot comparing sequential Euclidean linear distance calculations of the same landmarks, we found that there were no significant systematic biases in measurement error when using the Q3DC tool. Unfortunately, we could not test superimposition error in this study. However, the superimposition method used in this study has been previously validated by Ruellas et al.46 Using 3D Euclidean distances, they found mean differences of 0.38 mm and 0.37 mm for the right and left superior condylion fiducials after superimposition with a mandibular body voxel-based method in growing subjects. The results of this study may be different if alternative 3D regions of reference45 were used for superimposition.

When the use of the 5 condylar fiducials as an alternative to anatomic condylion was tested for intraobserver variability, it approximated the size of individual voxels.27 The additional condylar change in the 2-phase regime at the lateral condylar fiducial was within the variability of measurements in the lateral direction (−0.19 to 0.26 mm). Meanwhile, both the additional posterior (0.96 mm) and vertical (2.27 mm) condylar gains were outside of the variance in the posterior and vertical directions. This suggests that both the posterior and vertical condylar gains found in this study were not only statistically significant but appeared to be relatively robust to measurement errors associated with landmark placement.

The 2-phase group was statistically more retrognathic than the single-phase group when looking at corpus length (CoGn) or effective mandibular length (GoPg). However, the differences between groups for these measures (4.48 mm for CoGn and 2.78 mm for GoPg) were smaller than the variance found for each measure. When these differences were compared with the overall corpus length or effective mandibular length, they represented a 4% and 3.5% difference in size between the 2 groups, respectively. The clinical significance of this difference is questionable given the wide variety of Class II malocclusion presentations. The main purpose of this study was to investigate the process by which condylar remodeling occurs in the 2 treatment regimens used to treat Class II malocclusions in growing adolescents rather than differences between the groups.

The ANB was also greater in the 2-phase group. However, the standard deviation of SNA53,54 and SNB53 measures from CBCT-extracted lateral cephalograms ranged between 3–4° for SNA and 1.5° for SNB. Given the degree of variation found in these angular measures, ANB may not be an appropriate measure of skeletal disharmony for volumetric CBCT data.

The reliability of using CVM stages to identify subjects who are about to experience peak mandibular growth has recently been called into question. Mellion et al55 found that changes in stature were more reliable than radiographic methods such as hand-wrist radiography or CVM and suggested that these methods did not offer a marked advantage over chronological age for pubertal growth prediction. Gray et al56 found considerable individual variation in peak mandibular growth when using CVM stages. When age, sex, and CVM were used in a mixed model to predict peak mandibular growth, they found that chronological age was a better predictor than CVM. As this study was designed as a follow-up to Atresh et al,49 we chose to use the same inclusion and exclusion criteria so that the 2 works could remain comparable.

Unfortunately, there was a 7–8–month difference between the 2 regimes in overall treatment time. This difference in overall treatment time cannot be addressed by extrapolation of annualized rates in the Class II elastics group because it assumes continued linear rates of condylar growth in the last 7–8 months of treatment. Furthermore, there was a trend toward decreased condylar growth during the orthodontic phase (T2-T3) after the use of the Herbst appliance, which reached statistical significance in the posterior direction for all condylar fiducials with the exception of the posterior condyle (P <0.05). This suggests that the condylar gains found in short- to medium-term 2-phase regimes are related to growth acceleration, as an alternative to growth enhancement.39 This is an important distinction because an enhancement of condylar growth suggests a net gain in size, whereas acceleration suggests that these size gains are seen in a shorter period of time—they will ultimately reach the same size given sufficient time.5,7 In the case of growth acceleration, this deceleration of the rate of condylar growth during the orthodontic phase is expected.5 More research is required to determine whether equivalent treatment timeframes would produce equivalent condylar outcomes between the 2 treatment regimens.

CONCLUSIONS

CBCT and 3D mandibular regional voxel-based superimposition techniques of the mandible in growing adolescent subjects demonstrated the following:

The Herbst appliance when incorporated in a 2-phase regime produced an additional 0.96 mm of posterior condylar growth at the posterior condylar fiducial and 2.27 mm of vertical condylar growth at the superior condylar fiducial when compared with single-phase treatment with Class II elastics by the end of treatment. This represented an increase in condylar growth of 95.7% and 61.3%, respectively, with an average increase in treatment time of 7.79 ± 1.82 months.

Most of the sagittal condylar growth occurred during the orthopedic (T1-T2) phase with minimal contributions in the subsequent orthodontic (T2-T3) phase in a 2-phase regime.

There were equivalent amounts of vertical condylar growth in the orthopedic (T1-T2) and orthodontic (T2-T3) phases when the Herbst and multibracket appliances were used.

There was a trend toward decreased condylar growth during the orthodontic phase (T2-T3) after the use of the Herbst appliance when compared with single-phase treatment with Class II elastics. This reached statistical significance for all condylar fiducials in the posterior direction with the exception of the posterior condyle.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr Paul Buchholz for the collection and provision of the Herbst records.

This work was supported in part by the Australian Society of Orthodontists Foundation for Research and Education and the Stanley Jacobs Trust for Orthodontic Research.

Footnotes

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest, and none were reported.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2019.09.011.

REFERENCES

- 1.You ZH, Fishman LS, Rosenblum RE, Subtelny JD. Dentoalveolar changes related to mandibular forward growth in untreated Class II persons. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2001;120:598–607: quiz 676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsourakis AK, Johnston LE Jr. Class II malocclusion: the aftermath of a “perfect storm”. Semin Orthod 2014;20:59–73. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pancherz H The Herbst appliance—its biologic effects and clinical use. Am J Orthod 1985;87:1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pancherz H, Malmgren O, Hägg U, Ömblus J, Hansen K. Class II correction in Herbst and bass therapy. Eur J Orthod 1989;11:17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai M, McNamara JA. An evaluation of two-phase treatment with the Herbst appliance and preadjusted edgewise therapy. Semin Orthod 1998;4:46–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baccetti T, Franchi L, Stahl F. Comparison of 2 comprehensive Class II treatment protocols including the bonded Herbst and headgear appliances: a double-blind study of consecutively treated patients at puberty. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2009;135:698.e1–10: discussion 698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tulloch JFC, Phillips C, Proffit WR. Benefit of early Class II treatment: progress report of a two-phase randomized clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998;113:62–72: quiz 73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keeling SD, Wheeler TT, King GJ, Garvan CW, Cohen DA, Cabassa S, et al. Anteroposterior skeletal and dental changes after early Class II treatment with bionators and headgear. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998;113:40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paulsen HU, Papadopoulos MA. The Herbst Appliance Orthodontic treatment of the Class II noncompliant patient: current principles and techniques. London, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: Elsevier; 2006. p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pancherz H Treatment of Class II malocclusions by jumping the bite with the Herbst appliance. A cephalometric investigation. Am J Orthod 1979;76:423–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langford NM Jr. The Herbst appliance. J Clin Orthod 1981;15: 558–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howe RP. The bonded Herbst appliance. J Clin Orthod 1982;16: 663–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNamara JA, Howe RP, Dischinger TG. A comparison of the Herbst and Fr€ankel appliances in the treatment of Class II malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1990;98:134–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valant JR, Sinclair PM. Treatment effects of the Herbst appliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1989;95:138–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hägg U, Pancherz H. Dentofacial orthopaedics in relation to chronological age, growth period and skeletal development. An analysis of 72 male patients with Class II division 1 malocclusion treated with the Herbst appliance. Eur J Orthod 1988;10:169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pancherz H, Fackel U. The skeletofacial growth pattern pre- and post-dentofacial orthopaedics. A long-term study of Class II malocclusions treated with the Herbst appliance. Eur J Orthod 1990; 12:209–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnston LE. Functional appliances: a mortgage on mandibular position. Aust Orthod J 1996;14:154–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pacha MM, Fleming PS, Johal A. A comparison of the efficacy of fixed versus removable functional appliances in children with Class II malocclusion: a systematic review. Eur J Orthod 2016;38: 621–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Brien K, Wright J, Conboy F, Sanjie Y, Mandall N, Chadwick S, et al. Effectiveness of treatment for class II malocclusion with the herbst or twin-block appliances: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003;124:128–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pancherz H, Hägg U. Dentofacial orthopedics in relation to somatic maturation. An analysis of 70 consecutive cases treated with the Herbst appliance. Am J Orthod 1985;88:273–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson B, Hansen K, Hägg U. Class II correction in patients treated with Class II elastics and with fixed functional appliances: a comparative study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2000;118: 142–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serbesis-Tsarudis C, Pancherz H. “Effective” TMJ and chin position changes in Class II treatment. Angle Orthod 2008;78:813–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson B, Hägg U, Hansen K, Bendeus M. A long-term follow-up study of Class II malocclusion correction after treatment with Class II elastics or fixed functional appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2007;132:499–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janson G, Sathler R, Fernandes TMF, Branco NCC, de Freitas MR. Correction of Class II malocclusion with Class II elastics: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2013;143:383–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pancherz H In: Burkhardt DR, McNamara JA, Baccetti T. Maxillary molar distalization or mandibular enhancement: a cephalometric comparison of comprehensive orthodontic treatment including the pendulum and the Herbst appliances Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003;123:108–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burkhardt DR, McNamara JA, Baccetti T. Maxillary molar distalization or mandibular enhancement: a cephalometric comparison of comprehensive orthodontic treatment including the pendulum and the Herbst appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003;123:108–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baumrind S, Frantz RC. The reliability of head film measurements. 1. Landmark identification. Am J Orthod 1971;60:111–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baumrind S, Frantz RC. The reliability of head film measurements. 2. Conventional angular and linear measures. Am J Orthod 1971; 60:505–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pancherz H, Ruf S, Kohlhas P. Effective condylar growth” and chin position changes in Herbst treatment: a cephalometric roentgenographic long-term study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998; 114:437–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pancherz H, Michailidou C. Temporomandibular joint growth changes in hyperdivergent and hypodivergent Herbst subjects. A long-term roentgenographic cephalometric study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2004;126:153–61: quiz 254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baumrind S, Miller D, Molthen R. The reliability of head film measurements. 3. Tracing superimposition. Am J Orthod 1976;70:617–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buschang PH, Santos-Pinto A. Condylar growth and glenoid fossa displacement during childhood and adolescence. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998;113:437–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pancherz H, Fischer S. Amount and direction of temporomandibular joint growth changes in Herbst treatment: a cephalometric long-term investigation. Angle Orthod 2003;73:493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Björk A Variations in the growth pattern of the human mandible: longitudinal radiographic study by the implant method. J Dent Res 1963;42(1 Pt 2):400–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Björk A, Skieller V. Facial development and tooth eruption. An implant study at the age of puberty. Am J Orthod 1972;62:339–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Björk A, Skieller V. Normal and abnormal growth of the mandible. A synthesis of longitudinal cephalometric implant studies over a period of 25 years. Eur J Orthod 1983;5:1–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pancherz H The mechanism of Class II correction in Herbst appliance treatment. A cephalometric investigation. Am J Orthod 1982; 82:104–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Houston WJB. The analysis of errors in orthodontic measurements. Am J Orthod 1983;83:382–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Livieratos FA, Johnston LE. A comparison of one-stage and two-stage nonextraction alternatives in matched Class II samples. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1995;108:118–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnston LE. Let’s pretend. Semin Orthod 2014;20:249–52. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Souki BQ, Vilefort PLC, Oliveira DD, Andrade I, Ruellas AC, Yatabe MS, et al. Three-dimensional skeletal mandibular changes associated with Herbst appliance treatment. Orthod Craniofac Res 2017;20:111–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Oliveira Ruellas AC, Tonello C, Gomes LR, Yatabe MS, Macron L, Lopinto J, et al. Common 3-dimensional coordinate system for assessment of directional changes. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2016;149:645–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 2009;41:1149–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baccetti T, Franchi L, McNamara JA Jr. The cervical vertebral maturation (CVM) method for the assessment of optimal treatment timing in dentofacial orthopedics. Semin Orthod 2005;11:119–29. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen T, Cevidanes L, Franchi L, Ruellas A, Jackson T. Three-dimensional mandibular regional superimposition in growing patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2018;153:747–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Oliveira Ruellas AC, Yatabe MS, Souki BQ, Benavides E, Nguyen T, Luiz RR, et al. 3D mandibular superimposition: comparison of regions of reference for voxel-based registration. PLoS One 2016;11:e0157625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yatabe M, Garib D, Faco R, de Clerck H, Souki B, Janson G, et al. Mandibular and glenoid fossa changes after bone-anchored maxillary protraction therapy in patients with UCLP: a 3-D preliminary assessment. Angle Orthod 2017;87:423–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruf S, Pancherz H. Temporomandibular joint growth adaptation in Herbst treatment: a prospective magnetic resonance imaging and cephalometric roentgenographic study. Eur J Orthod 1998;20: 375–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Atresh A, Cevidanes LHS, Yatabe M, Muniz L, Nguyen T, Larson B, et al. Three-dimensional treatment outcomes in Class II patients with different vertical facial patterns treated with the Herbst appliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2018; 154:238–48.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lagravère MO, Low C, Flores-Mir C, Chung R, Carey JP, Heo G, et al. Intraexaminer and interexaminer reliabilities of landmark identification on digitized lateral cephalograms and formatted 3-dimensional cone-beam computerized tomography images. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2010; 137:598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.LeCornu M, Cevidanes LHS, Zhu H, Wu CD, Larson B, Nguyen T. Three-dimensional treatment outcomes in Class II patients treated with the Herbst appliance: a pilot study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2013;144:818–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schudy FF. Vertical growth versus anteroposterior growth as related to function and treatment. Angle Orthod 1964;34: 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumar V, Ludlow J, Soares Cevidanes LH, Mol A. In vivo comparison of conventional and cone beam CT synthesized cephalograms. Angle Orthod 2008;78:873–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cattaneo PM, Bloch CB, Calmar D, Hjortshøj M, Melsen B. Comparison between conventional and cone-beam computed tomography–generated cephalograms. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2008;134:798–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mellion ZJ, Behrents RG, Johnston LE Jr. The pattern of facial skeletal growth and its relationship to various common indexes of maturation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2013; 143:845–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gray S, Bennani H, Kieser JA, Farella M. Morphometric analysis of cervical vertebrae in relation to mandibular growth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2016;149:92–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.