Abstract

Megakaryocytes (MKs) give rise to platelets, which are blood cells that are essential to prevent hemorrhage. Although the majority of MKs localize to the bone marrow, there is a distinct population of lung-residing MKs (MKL). In this issue of the JCI, Pariser et al. examined gene expression patterns of MKs collected from murine and nonhuman primate bone marrow or lung. This Commentary explores the premise that environmental factors from the lung determine the genetic and phenotypic similarity of MKL to lung dendritic cells, distinguishing MKL from bone marrow MKs. Indeed, while MKL retain the ability to make platelets, they also process and present antigens that activate CD4+ lymphocytes. These data suggest that MKL may play an important role in immune processes beyond platelet production.

Megakaryocytes in the lung

Megakaryocytes (MKs) are unique cells that give rise to circulating platelets. The majority of MKs reside in the bone marrow (BM), where they differentiate from hematopoietic stem cells, mature, and release proplatelets into the vascular lumen that are quickly converted into platelets (1, 2). However, MKs have also been found in other organs such as the lungs, liver, and spleen (3, 4), with up to 8% of murine MKs residing in the lungs (5). Although lung MKs were first observed in the late 19th century, their biological function and relevance have remained obscure. In this issue of the JCI, Pariser et al. have begun to unravel the mysteries of lung-residing MKs (MKL) by uncovering their unique properties, and reveal that MKL are genetically and phenotypically similar to resident lung dendritic cells (6).

Previous findings suggest that MKL can produce platelets (4, 7). Although it is debated whether a substantial proportion of circulating platelets are generated from MKL, the recent reemergence of this unique MK population has led to questions about if and how MKL differ from BM MKs. Pariser and colleagues isolated BM and lung myeloid-enriched cells from both mice and nonhuman primates and characterized the populations using single-cell RNA sequencing. The researchers found that MKL have gene expression patterns that are more similar to lung dendritic cells than autologous BM MKs. Indeed, MKL express high levels of markers such as major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II), CD11c, ICAM, and CCR7, with MHC-II being a marker that appears to faithfully differentiate MKL and BM MKs. In addition, the MKL population is predominantly diploid, or 2N, which is in stark contrast to larger BM MKs that have an average ploidy of 16N. Although both MKL and BM MKs are capable of generating proplatelets in culture, the overall platelet-generating capacity of each population was not investigated. Together, these data suggest that MKL are both morphometrically and genotypically unique, and therefore may play an important role in processes beyond platelet production.

The immune phenotype of MKL is plastic

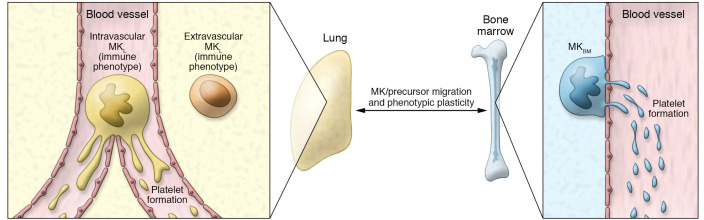

One of the more intriguing findings from Pariser et al. (6) is that the immune phenotype of MKL is plastic and driven by the tissue environment. The BM and lung have many environmental distinctions, some of the most notable being differences in the higher oxygenation and increased accessibility to pathogens in the lungs. Therefore, Pariser and colleagues aimed to determine the roles that these unique environments play in formation and/or maintenance of their resident MKs. To do this, the authors cleverly used neonatal (P0) mouse lungs to determine if the MKL phenotype changes over development. They found that P0 MKL did not yet resemble the MKL in adult lungs, suggesting that this immune phenotype is not an inherent property of the MK population, but is rather gained over time as a result of the MKL environment. Likewise, the converse was also found to be true. While exposure of BM MKs to hypoxic and normoxic conditions failed to impact expression of MHC-II molecules, BM MKs had the capacity to adopt an MKL-like phenotype under the influence of pathogen-associated molecular patterns and lung-associated immune molecules, such as IL-33. In vivo administration of BM MKs to the lungs further confirmed this plasticity; after 48 hours, infused BM MKs upregulated both MHC-II and CCR7. Of note, however, resident MKL secreted more immune molecules compared with BM MKs upon stimulation with lipopolysaccharide. This result suggests that the MKL programming results in functionally distinct MKs (6). What has yet to be fully addressed, however, is the source(s) of the MKL population. Are the MKL derived from hematopoietic stem cells that reside in the BM? And if not, is there a pool of resident hematopoietic stem cells in the lung? This study and previous work document distinct intravascular and extravascular MKL populations (Figure 1) (4). Indeed, the present study shows that extravascular MKL represented approximately 60% of the total MKL population. This result raises the question of whether the MKL with an immune phenotype are mainly localized in the lung parenchyma, while MKL that are lodged in blood vessels produce platelets. Furthermore, there is the possibility that there is more than one population of MKL that could originate from different sources. Indeed, the notion of MK plasticity may further complicate these questions because of the possibility for continuous exchange of MKs or MK progenitors between the BM and lungs (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Model for MK plasticity.

The lung contains intravascular and extravascular populations of megakaryocytes (MKL). MKL that are large, polyploid (average of 16N), and intravascular are ideally positioned to release proplatelets into flowing blood. Extravascular diploid (2N) MKL resemble lung dendritic cells. The local environment modulates the phenotype of BM MKs (MKBM) and MKL. Notably, MKBM that are transferred into the lungs adopt an MKL-like phenotype (6). MKs or MK progenitors may continuously migrate between the BM and the lungs.

What is the functional consequence of having immune-like MKs in the lungs? One obvious role of the MKL could be in their response to pathogens. MHC class I molecules are found on all nucleated cells and platelets and are in charge of the presentation of cytosolic proteins to CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Prior work has shown that platelets (8) and MKs derived from BM (9) can present peptides through MHC class I molecules, thereby promoting CD8+ lymphocyte proliferation. In contrast, MHC-II molecules are found on professional antigen-presenting cells, such as dendritic cells, macrophages, and B lymphocytes, and are in charge of presentation of extracellular antigens that have been internalized and hydrolyzed in phagolysosomes. Another important finding by Pariser et al. is the identification of MHC-II on MKL. The authors demonstrated that MKL were more potent than BM MKs in phagocytosis of E. coli. Moreover, using elegant in vitro and in vivo approaches, they showed that MKL presented antigens through MHC-II to specifically promote CD4+ T lymphocyte activation (6). The biological implications of MKL immune functions are interesting and far reaching, as MKL may not only have a complementary role to other lung immune cells, but may also generate a distinct pool of platelets with immune functions that have been previously overlooked.

Questions of origin

One of the looming questions that remains is whether MKL are immune cells that express MK markers or are MKs masquerading as immune cells. At its core, such cell origin questions can become almost philosophical. What makes an MK an MK? Its gene expression profile? The ability to make platelets? The data in Pariser et al. reveal common cell markers and functions between MKL and BM MKs, including the ability to produce platelets (6). As such, the data seem to point to MKL having an MK origin, with the lung environment modifying the cells. However, this identity question can only be definitively answered by determining if the cells of origin and subsequent differentiation trajectories of these two (or more) MK populations are the same, and if the trajectories differ, where might the lineages diverge. Future studies tracing the lineage of both BM and MKL will be essential in establishing that location determines MK function.

Version 1. 01/04/2021

Print issue publication

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Copyright: © 2021, American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Reference information: J Clin Invest. 2021;131(1):e144964. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI144964.

See the related article at Lung megakaryocytes are immune modulatory cells.

Contributor Information

Eric Boilard, Email: Eric.Boilard@crchudequebec.ulaval.ca.

Kellie R. Machlus, Email: kmachlus@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Machlus KR, et al. The incredible journey: From megakaryocyte development to platelet formation. J Cell Biol. 2013;201(6):785–796. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201304054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noetzli LJ, et al. New insights into the differentiation of megakaryocytes from hematopoietic progenitors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39(7):1288–1300. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.312129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis E, et al. Histologic studies of splenic megakaryocytes after bone marrow ablation with strontium 90. J Lab Clin Med. 1992;120(5):767–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lefrancais E, et al. The lung is a site of platelet biogenesis and a reservoir for haematopoietic progenitors. Nature. 2017;544(7648):105–109. doi: 10.1038/nature21706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potts KS, et al. Membrane budding is a major mechanism of in vivo platelet biogenesis. J Exp Med. 2020;217(9):e20191206. doi: 10.1084/jem.20191206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pariser DN, et al. Lung megakaryocytes are immune modulatory cells. J Clin Invest. 2020;131(1):e137377. doi: 10.1172/JCI137377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuentes R, et al. Infusion of mature megakaryocytes into mice yields functional platelets. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(11):3917–3922. doi: 10.1172/JCI43326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapman LM, et al. Platelets present antigen in the context of MHC class I. J Immunol. 2012;189(2):916–923. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zufferey A, et al. Mature murine megakaryocytes present antigen-MHC class I molecules to T cells and transfer them to platelets. Blood Adv. 2017;1(20):1773–1785. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017007021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]