Highlights

-

•

A cervical desmoid tumor could be successfully controlled with proton therapy.

-

•

Desmoid tumors commonly occur in the limbs and trunk, rarely in the neck.

-

•

Proton beam therapy was selected to reduce radiation related adverse events.

Keywords: Desmoid tumor, Desmoid fibromatosis, Radiation, Proton beam therapy

Abstract

Desmoid tumors are benign, but may have a locally invasive tendency that commonly results in local recurrence. Most occur on the body trunk or extremities, whereas a head and neck desmoid tumor is relatively rare. The efficacy of radiotherapy has been suggested and 50–60 Gy is used for unresectable or recurrent desmoid tumors, but there are few reports of use of particle beam therapy. However, since this tumor occurs more often in younger patients compared to malignant tumors and the prognosis is favorable, there may be an advantage of this therapy. We treated a male patient with a head and neck recurrent desmoid tumor with proton beam therapy (PBT) at a dose of 60 Gy (RBE). This patient underwent surgical resection as initial treatment, but the tumor recurred only six months after surgery, and resection was performed again. After PBT, the tumor gradually shrank and complete remission has been achieved for 10 years without any severe late toxicity. Here, we report the details of this case, with a review of the literature. We suggest that PBT may reduce the incidence of second malignant tumors by reducing the dose exposure around the planning target volume.

1. Introduction

Desmoid tumor is a rare tumor that accounts for less than 3% of all soft tissue tumors. Desmoid tumors do not metastasize, but do have a high tendency for local invasion [1]. Surgery is the first-choice treatment and radiotherapy of 50–60 Gy is also a treatment option for cases that are inoperable or have postoperative recurrence [2]. In this article, we report successful use of proton beam therapy (PBT) for long-term control of a postoperative recurrent desmoid tumor of the neck that had shown a tendency to increase in size.

2. Case

A 69-year-old man received PBT for a recurrent cervical desmoid tumor at our hospital. He or his family did not experienced colorectal adenoma or adenocarcinoma. He had become aware of a right cervical mass in 64 years old. The mass slowly increased in size and numbness in the right shoulder progressed. He visited an otorhinologist and the mass was diagnosed as a desmoid tumor at the C3-C6 cervical vertebrae. Tumor resection was performed in same years. However, about 6 months after surgery, the tumor began to increase in size. Surgical resection with the sternocleidomastoid muscle was performed in 66 years old by orthopedists in our hospital. The pathological diagnosis was desmoid-type fibromatosis. The surgical margin was unclear and residual tumor was not clearly found.

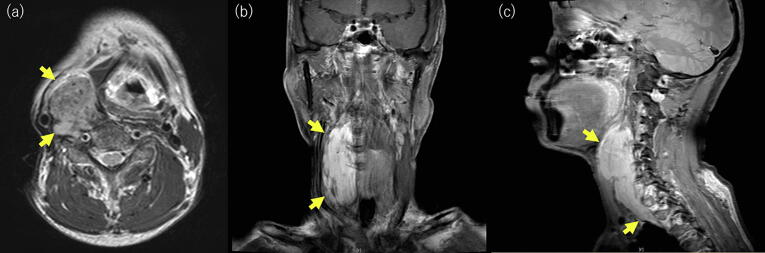

About 1 year later the tumor had regrown and that another year later he had right neck pain and a pressing feeling. Further surgical resection was impossible because the tumor was adjacent to the carotid artery and had widely infiltrated vertebral bodies. Therefore, PBT was recommended, because at that time, IMRT was not common in Japan, and it was impossible to deliver enough dose to the tumor keeping tolerance dose to spinal cord with three dimensional radiotherapy. Prior to PBT (Fig. 1) the tumor extended from the level of the bifurcation of the right common carotid artery to the entrance to the thorax at the Th2 level, with wide infiltration of vertebral bodies and compression of the right internal carotid artery outward. The tumor size was 110 mm vertically and up to 40 mm horizontally.

Fig. 1.

MRI of the desmoid tumor before proton beam therapy. (a) Axial T2-weighted image. (b) Coronal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image. (c) Sagittal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image.

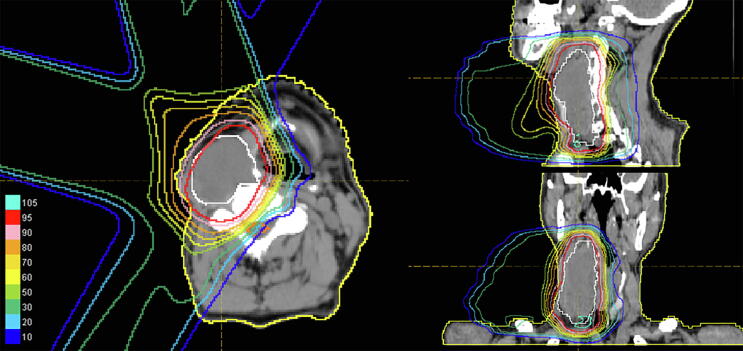

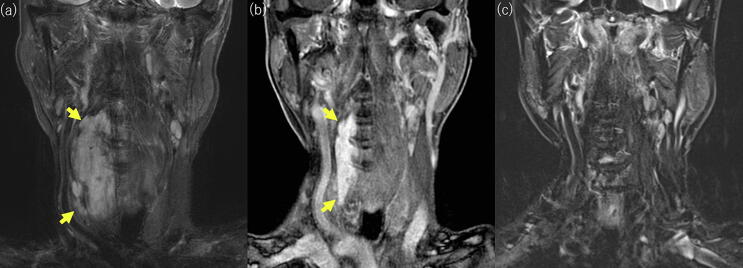

PBT was administered at a total dose of 60 Gy (relative biological effectiveness (RBE)) in 30 fractions. The dose distribution is shown in Fig. 2. We define Clinical tumor volume (CTV) as equal to gross tumor volume (GTV). Margins of 1.3 cm were added to give the planning target volume (PTV). Treatment beams were delivered with 3 ports. Eight months after PBT, the tumor had shrank to 70 mm vertically and continued to shrink gradually (Fig. 3b). No recurrent tumor was detected on MRI in 78 years old (Fig. 3c), and he has been in complete remission for 10 years. Grade 2 dermatitis and pharyngitis occurred as acute adverse events, with no late adverse events. These doses were calculated assuming the RBE to be 1.1 [3].

Fig. 2.

Irradiation plan for proton beam therapy. Three beams were used for irradiation. The CTV was defined as equal to the GTV and was irradiated with a total dose of 60 Gy (RBE)/30 fr.

Fig. 3.

MRI showing the course after proton beam therapy. (a) Coronal short TI inversion recovery image before PBT. (b) Coronal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image 8 months after PBT. (c) Coronal short TI inversion recovery image 8 years and 8 months after PBT.

3. Discussion

Desmoid tumors occur most often between the ages of 15 and 60, with a peak at 30 to 40 years old [1], [4], [5]. The tumor is benign and does not metastasize, but can invade nearby tissue aggressively and often painfully. Some desmoid tumors do not increase in size and 20% decrease naturally [6], [7], but some grow rapidly and local recurrence is common because of the lack of a capsule and infiltrative growth [8]. Desmoid tumors arise from connective tissues and occur in many body regions, but most are found in the extremities, abdominal wall and chest wall, and particularly in the abdominal cavity and abdominal wall in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis [8].

Head and neck (H&N) desmoid tumors are relatively rare. In the EORTC (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer) study, 44 desmoid tumors were analyzed, but only one was a H&N tumor [9]. In studies by Spear et al. [2] and Guadagnolo et al. [10] the H&N desmoid rates were 5/107 and 16/115, respectively. The local recurrence rate is 16–33%, even after complete surgical resection [4], [11], [12], [13], and a large surgical margin was originally thought to be necessary to achieve local control [11], [12]. Therefore, treatment of progressive desmoid tumor is difficult, although some studies have suggested no significant relationship between the surgical margin and local control rate [6], [14], [15]. Treatment is particularly challenging for an aggressive H&N desmoid tumor because complete resection is difficult. de Bree et al. reported resection with a microscopically free surgical margin in 38–55% of adult cases [8]. Localization near the branchial plexus, involvement of the deep cervical fossa, and tumors in skin of head were more likely to have positive margin [8].

Radiotherapy is a treatment option for recurrent or unresectable desmoid tumor, and the recommended dose is around 60 Gy. Spear et al. suggested 60–65 Gy for a desmoid gross tumor and 50–60 Gy for a microscopic residual tumor as optimal doses for radiotherapy [2]. In 115 cases, Guadagnolo et al. found no advantage for the tumor control rate at a dose >56 Gy, and adverse events such as soft tissue necrosis and edema increased by dose escalation to >56 Gy [10]. A prospective phase II study (EORTC62991-22998) showed a 3-year local control rate of 81.5% with 56 Gy in 28 fractions [9], while Guadagnolo et al. reported a 10-year local control rate of 75% [10]. These results suggest that moderate-dose radiotherapy is effective for desmoid tumors.

Baumert et al. found that half of recurrences after radiotherapy for desmoid tumors are outside the irradiation field and in the PTV and vicinity of the PTV [15]. Therefore, a wide margin is recommended: the CTV margin needs to be ≥5 cm along the muscle fibers when the gross tumor volume (GTV) is the tumor area evident on imaging [2], [11], [15], [16]. The protocol of the ERTOG trial also set a margin of 5 cm in the direction along muscle fibers and 2 cm in all other directions [9]. However, such a large irradiation field is not suitable for cervical desmoid tumors [8]. In our case, the CTV margin was limited to the gross tumor due to the adjacency of the laryngopharynx and spinal cord to the tumor, but long-term local control was achieved with a good therapeutic effect and no adverse effects.

Desmoid tumors are most common at age 15 to 60 years old [1]. The prognosis of a desmoid tumor depends on site, growth and treatment, but most tumors are not life-threatening. However, for younger people, the risk of secondary cancer is a significant problem. Recent progress of radiotherapy has made it possible to avoid risk organs such as the spinal cord and parotid gland by using intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). There are very few reports of secondary cancer after radiotherapy for a desmoid tumor [10]. However, many studies have compared the dose distribution and risk of secondary cancer after PBT and IMRT, and all have suggested that PBT can reduce the secondary cancer risk [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22].

Studies using particle beams for recurrent desmoid tumor after surgical resection have reported favorable results, including for tumors of the abdominal wall by Nagata et al. [23], [24] and of the right flank by Kil et al. [25]. There are few reports of particle beam therapy for desmoid tumors: a search for “Proton/Carbon therapy, Desmoid” in PubMed yielded only three reports (Table 1). These include Nagata et al. and Kil et al., plus a report by Seidenssal et al. [26] of 44 radiotherapy cases, including 15 treated with PBT and 1 with carbon ions (with reirradiation). The 3- and 5-year progression-free survival rates were 72.3% and 58.4% with median follow-up of 32 months and a median dose 54 Gy, but the effects of particle types were not examined [26].

Table 1.

Reported cases of use of particle beam therapy for desmoid tumors, including this case.

| Author | Patient | TumorLocation | Radiation qualityTotal dose | Previous treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nagata et al.(2016) | 39 years old Male | Abdominal wall | Proton50 Gy(RBE)/25fr | Surgery(Once) | PR(two years follow) |

| Kil et al.(2012) | 36 years old Female | Right flank | Proton50 Gy(RBE)/25fr | Surgery(Once) | CR(two years follow) |

| This case | 69 years old Male | Right cervical | Proton60 Gy(RBE)/30fr | Surgery(Twice) | CR(ten years follow) |

*Seidensaal et al. reported 44 radiotherapy cases, including 15 treated with proton beams and 1 with a carbon beam, with 3-/5-year PFS of 72.3%/58.4% (median follow-up 32 months, median dose 54 Gy).

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, we experienced a case of long-term control of a head and neck desmoid tumor using PBT. This case suggests that PBT may be expected to favorable treatment considering secondary malignancies and long-term surviva.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could appear to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Kasper B., Ströbel P., Hohenberger P. Desmoid tumors: clinical features and treatment options for advanced disease. Oncologist. 2011;16(5):682–693. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spear M.A., Jennings L.C., Mankin H.J., Spiro I.J., Springfield D.S., Gebhardt M.C., Rosenberg A.E., Efird J.T., Suit H.D. Individualizing management of aggressive fibromatoses. Int J Radiat Oncol*Biol*Phys. 1998;40(3):637–645. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00845-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paganetti H., Niemierko A., Ancukiewicz Marek, Gerweck Leo E., Goitein Michael, Loeffler Jay S. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53(2):407–421. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02754-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mankin H.J., Hornicek F.J., Springfield D.S. Extra-abdominal desmoid tumors: a report of 234 cases: desmoid tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102(5):380–384. doi: 10.1002/jso.21433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Ortega DY, Martín-Tellez KS, Cuellar-Hubbe M, Martínez-Said H, Álvarez-Cano A, Brener-Chaoul M, et al. Desmoid-type fibromatosis. Cancers. 2020;12(7):1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Salas S., Dufresne A., Bui B., Blay J.-Y., Terrier P., Ranchere-Vince D., Bonvalot S., Stoeckle E., Guillou L., Le Cesne A., Oberlin O., Brouste V., Coindre J.-M. Prognostic factors influencing progression-free survival determined from a series of sporadic desmoid tumors: a wait-and-see policy according to tumor presentation. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(26):3553–3558. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.5489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gounder M.M., Mahoney M.R., Van Tine B.A., Ravi V., Attia S., Deshpande H.A., Gupta A.A., Milhem M.M., Conry R.M., Movva S., Pishvaian M.J., Riedel R.F., Sabagh T., Tap W.D., Horvat N., Basch E., Schwartz L.H., Maki R.G., Agaram N.P., Lefkowitz R.A., Mazaheri Y., Yamashita R., Wright J.J., Dueck A.C., Schwartz G.K. Sorafenib for advanced and refractory desmoid tumors. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(25):2417–2428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Bree E., Zoras O., Hunt J.L., Takes R.P., Suárez C., Mendenhall W.M., Hinni M.L., Rodrigo J.P., Shaha A.R., Rinaldo A., Ferlito A., de Bree R., Eisele D.W. Desmoid tumors of the head and neck: a therapeutic challenge: desmoid tumors of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2014:1517–1526. doi: 10.1002/hed.23496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keus R.B., Nout R.A., Blay J.-Y., de Jong J.M., Hennig I., Saran F., Hartmann J.T., Sunyach M.P., Gwyther S.J., Ouali M., Kirkpatrick A., Poortmans P.M., Hogendoorn P.C.W., van der Graaf W.T.A. Results of a phase II pilot study of moderate dose radiotherapy for inoperable desmoid-type fibromatosis—an EORTC STBSG and ROG study (EORTC 62991–22998) Ann Oncol. 2013;24(10):2672–2676. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guadagnolo B.A., Zagars G.K., Ballo M.T. Long-term outcomes for desmoid tumors treated with radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol*Biol*Phys. 2008;71(2):441–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nuyttens J.J., Rust P.F., Thomas C.R., Turrisi A.T. Surgery versus radiation therapy for patients with aggressive fibromatosis or desmoid tumors: a comparative review of 22 articles. Cancer. 2000;88(7):1517–1523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballo MT, Zagars GK, Pollack A, Pisters PW, Pollack RA. Desmoid tumor: prognostic factors and outcome after surgery, radiation therapy, or combined surgery and radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(1):158-167. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Huang K., Fu H., Shi Y.-Q., Zhou Y., Du C.-Y. Prognostic factors for extra-abdominal and abdominal wall desmoids: A 20-year experience at a single institution: Extra-Abdominal and Abdominal Wall Desmoids. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100(7):563–569. doi: 10.1002/jso.21384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner B., Alghamdi M., Henning J.-W., Kurien E., Morris D., Bouchard-Fortier A., Schiller D., Puloski S., Monument M., Itani D., Mack L.A. Surgical excision versus observation as initial management of desmoid tumors: a population based study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45(4):699–703. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baumert B.G., Spahr M.O., Hochstetter A.V., Beauvois S., Landmann C., Fridrich K., Villà S., Kirschner M.J., Storme G., Thum P., Streuli H.K., Lombriser N., Maurer R., Ries G., Bleher E.-A., Willi A., Allemann J., Buehler U., Blessing H., Luetolf U.M., Davis J.B., Seifert B., Infanger M. The impact of radiotherapy in the treatment of desmoid tumours. An international survey of 110 patients. A study of the Rare Cancer Network. Radiat Oncol. 2007;2(1) doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ballo M.T., Zagars G.K., Pollack A. Radiation therapy in the management of desmoid tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol*Biol*Phys. 1998;42(5):1007–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00285-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung C.S., Yock T.I., Nelson K., Xu Y., Keating N.L., Tarbell N.J. Incidence of second malignancies among patients treated with proton versus photon radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol*Biol*Phys. 2013;87(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miralbell R., Lomax A., Cella L., Schneider U. Potential reduction of the incidence of radiation-induced second cancers by using proton beams in the treatment of pediatric tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol*Biol*Phys. 2002;54(3):824–829. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02982-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Athar B.S., Paganetti H. Comparison of second cancer risk due to out-of-field doses from 6-MV IMRT and proton therapy based on 6 pediatric patient treatment plans. Radiother Oncol. 2011;98(1):87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sethi R.V., Shih H.A., Yeap B.Y., Mouw K.W., Petersen R., Kim D.Y., Munzenrider J.E., Grabowski E., Rodriguez-Galindo C., Yock T.I., Tarbell N.J., Marcus K.J., Mukai S., MacDonald S.M. Second nonocular tumors among survivors of retinoblastoma treated with contemporary photon and proton radiotherapy: Second Tumors After Photon RT for Rb. Cancer. 2014;120(1):126–133. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hillbrand M., Georg D., Gadner H., Pötter R., Dieckmann K. Abdominal cancer during early childhood: a dosimetric comparison of proton beams to standard and advanced photon radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2008;89(2):141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eaton B.R., MacDonald S.M., Yock T.I., Tarbell N.J. Secondary malignancy risk following proton radiation therapy. Front Oncol. 2015;26(5):261. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagata T., Demizu Y., Okumura T., Sekine S., Hashimoto N., Fuwa N., Okimoto T., Shimada Y. Carbon ion radiotherapy for desmoid tumor of the abdominal wall: a case report. World J Surg Onc. 2016;14(1) doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-1000-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagata T., Demizu Y., Okumura T., Sekine S., Hashimoto N., Fuwa N., Okimoto T., Shimada Y. Erratum to: Carbon ion radiotherapy for desmoid tumor of the abdominal wall: a case report. World J Surg Onc. 2017;15(1) doi: 10.1186/s12957-017-1154-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kil W.J., Nichols R.C., Jr, Kilkenny J.W., Huh S.Y., Ho M.W., Gupta P., Marcus R.B., Indelicato D.J. Proton therapy versus photon radiation therapy for the management of a recurrent desmoid tumor of the right flank: a case report. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7(1) doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seidensaal K, Harrabi SB, Weykamp F, Herfarth K, Welzel T, Mechtersheimer G, et al. Radiotherapy in the treatment of aggressive fibromatosis: experience from a single institution. Radiat Oncol. 2020;15(1):143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]