Abstract

Autophagy and endolysosomal trafficking are crucial in neuronal development, function and survival. These processes ensure efficient removal of misfolded aggregation-prone proteins and damaged organelles, such as dysfunctional mitochondria, thus allowing the maintenance of proper cellular homeostasis. Beside this, emerging evidence has pointed to their involvement in the regulation of the synaptic proteome needed to guarantee an efficient neurotransmitter release and synaptic plasticity. Along this line, an intimate interplay between the molecular machinery regulating synaptic vesicle endocytosis and synaptic autophagy is emerging, suggesting that synaptic quality control mechanisms need to be tightly coupled to neurosecretion to secure release accuracy. Defects in autophagy and endolysosomal pathway have been associated with neuronal dysfunction and extensively reported in Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis among other neurodegenerative diseases, with common features and emerging genetic bases. In this review, we focus on the multiple roles of autophagy and endolysosomal system in neuronal homeostasis and highlight how their defects probably contribute to synaptic default and neurodegeneration in the above-mentioned diseases, discussing the most recent options explored for therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: autophagy, endocytosis, lysosomes, neurodegenerative diseases, synapse

Introduction

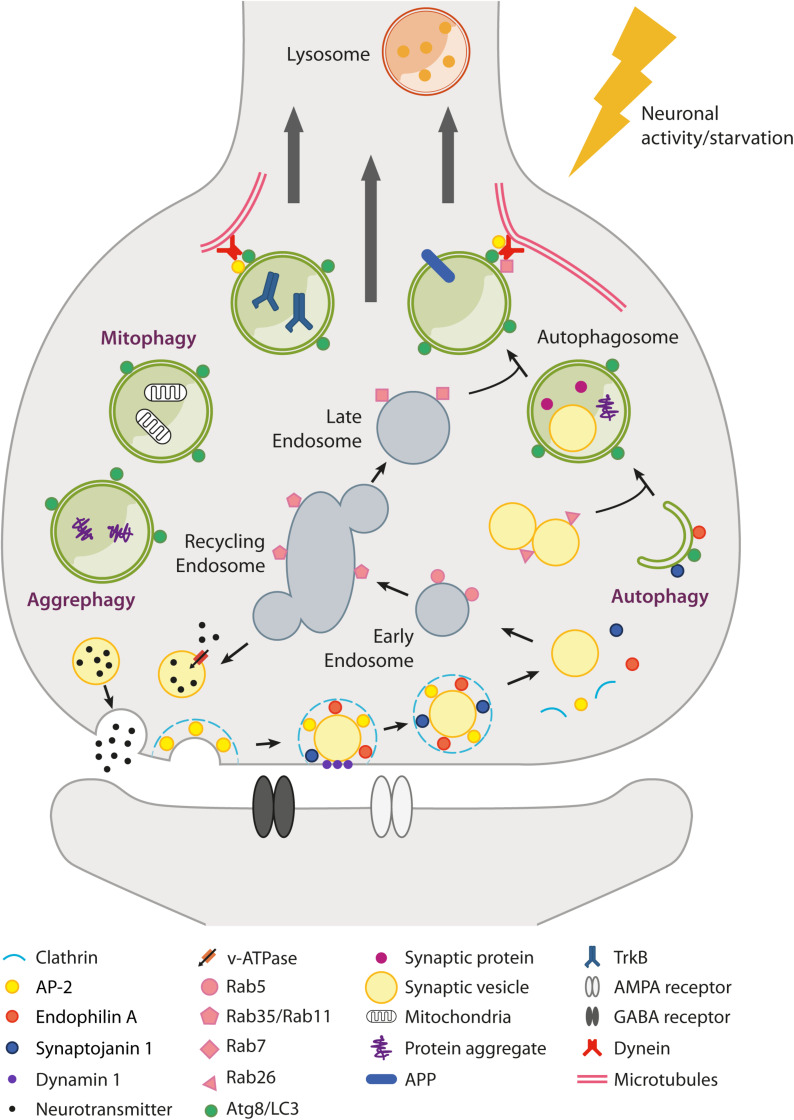

Neurons are complex polarized post-mitotic cells, highly dependent on intracellular trafficking and protein quality control mechanisms to maintain proper homeostasis and sustain their function, particularly at the synaptic level (Wang et al., 2017; Wertz et al., 2020). One of the primary cellular degradative pathways is macroautophagy (hereafter autophagy), an evolutionarily conserved catabolic process that eliminates damaged organelles and misfolded proteins through the selective or non-selective engulfment of cytoplasmic materials in double-membrane autophagosomes. In neurons, autophagosome biogenesis is highly compartmentalized and extensively initiated in distal axons and at synapses in order to meet the need of constantly rejuvenating peripherally located proteins and organelles (Figure 1; Maday et al., 2012; Maday and Holzbaur, 2014). Autophagy intersects at multiple levels with the endolysosomal system (Winckler et al., 2018). Indeed, autophagosomes generated at synaptic terminals fuse with late endosomes, thus acquiring dynein motors and retrograde motility along microtubules (Gutierrez et al., 2004; Deinhardt et al., 2006; Cheng et al., 2015). During their retrograde journey, autophagosomes acidify and degrade their content by fusing with lysosomes, which are enriched at the soma (Lee et al., 2011; Maday et al., 2012). Autophagy induction is under the opposing control of the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), which differentially phosphorylate the ULK1 autophagic initiating complex, leading to its activation or inhibition, respectively. Subsequently, a complex network of proteins regulates the biogenesis, maturation, and trafficking of neuronal autophagosomes (Bingol, 2018).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic overview of autophagy and endolysosomal trafficking at the synapse. Local regulation of protein turnover occurs via autophagy (either non-selective and selective, e.g., mitophagy and aggrephagy) and the endolysosomal system (Rab5/Rab35/Rab7-dependent pathway), which can be stimulated by neuronal activity and nutrient depletion. In particular, metabolic signals activated upon nutrient restriction lead to mTORC1 inhibition and robust autophagy activation in many tissues. However, conflicting results have been raised as to whether starvation or mTORC1 inhibition are able to efficiently induce autophagy in neurons. mTORC1-independent pathways also exist (e.g., trehalose-induced) but are poorly characterized. At the presynaptic terminal, synaptic vesicle (SV) components retrieved after neurotransmitter release (e.g., by clathrin-mediated endocytosis) can transit through the endosomal compartment to be recycled back as newly formed SVs or be directed via late endosomes to lysosomes for degradation. Alternatively, SVs can be degraded via autophagy with a Rab26-dependent mechanism. Several presynaptic endocytic factors (e.g., Endophilin A, Synaptojanin1, AP-2) are implicated in the regulation of synaptic autophagy. Autophagosomes fuse with late endosomes to generate amphisomes and are transported along microtubules back to the soma, where fusion with lysosomes allows the digestion and recycling of cargoes. Autophagosomes can also act as signaling organelles, e.g., modulating neurotrophin-mediated TrkB signaling. Postsynaptically, autophagy and the endolysosomal system regulate neurotransmitter receptor trafficking and degradation.

Autophagy inhibition, e.g., through genetic deletion of the autophagy-related genes 5 and 7 (ATG5, ATG7) involved in autophagosome biogenesis, leads to neurodegeneration in mice (Hara et al., 2006; Komatsu et al., 2006), thus supporting a fundamental role of this process in neuronal physiology and survival. In addition, emerging evidence has pointed to a role of autophagy and endolysosomal system in the turnover of synaptic components, such as synaptic vesicles (SVs), postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptors and mitochondria, thus opening the possibility that these pathways are involved in the shaping of synaptic structure and function (Liang, 2019). It is therefore not surprising that defects in autophagic and endolysosomal pathways have been implicated in the pathogenesis of several human neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease (HD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), probably contributing to synaptic dysfunction and neurodegeneration (Winckler et al., 2018).

Autophagy in Neuronal Homeostasis

Autophagy at the Synapse

During development, autophagy promotes the assembly of presynaptic terminals at the neuromuscular junction in Drosophila (Shen and Ganetzky, 2009) and in specific neuronal subsets in Caenorhabditis elegans (Stavoe et al., 2016). In mouse hippocampal and cortical neurons, autophagy is required for developmental pruning of dendritic spines (Tang et al., 2014).

In mature synapses, the endolysosomal system and endosomal microautophagy (i.e., the engulfment of cargoes through the invagination of late endosome membranes generating multivesicular bodies) are important mechanisms for cytosolic and membrane-associated presynaptic protein sorting and turnover, particularly for SV components (Uytterhoeven et al., 2011, 2015; Fernandes et al., 2014; Sheehan et al., 2016; Jin et al., 2018). Synaptic autophagy is implicated as well in the degradation of specific SV proteins (Hoffmann et al., 2019) or of SVs via a Rab26-dependent pathway (Binotti et al., 2015). It is worth noting that the genetic ablation of the Rab26 guanine-nucleotide exchange factor Plekhg5 results in a late-onset motoneuron disease characterized by impaired autophagy, accumulation of aberrant SVs and degeneration of motoneuron axonal terminals (Lüningschrör et al., 2017). Interestingly, emerging evidence indicates that many presynaptic proteins involved in SV endocytosis play a role in synaptic autophagy: LRRK2, Endophilin-A and synaptojanin 1 are required for autophagosome formation (Murdoch et al., 2016; Soukup et al., 2016; Vanhauwaert et al., 2017), the adaptor proteins AP-2 and PICALM may act as cargo receptors (e.g., for the amyloid precursor protein APP; Tian et al., 2013), and AP-2 participates to autophagosome retrograde transport (Kononenko et al., 2017; Bera et al., 2020). In addition, the presynaptic scaffolding protein Bassoon inhibits autophagy by interacting with ATG5, and its loss leads to increased SV degradation (Okerlund et al., 2017). This molecular crosstalk between SV recycling and autophagy may provide an activity-dependent quality control mechanism needed to guarantee an adequate neurotransmitter release. Indeed, an efficient rejuvenation of SV proteins has been shown to facilitate neurotransmission in Drosophila (Uytterhoeven et al., 2011; Fernandes et al., 2014). On the other hand, in mouse dopaminergic neurons, the pharmacological induction of autophagy with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin reduced the number of SVs and depressed the evoked dopamine release (Hernandez et al., 2012).

Concerning the postsynaptic compartment, the endolysosomal pathway has a well-known relevance in AMPA receptor recycling and degradation according to synaptic activity (Ehlers, 2000; Fernández-Monreal et al., 2012; Zheng et al., 2015). Autophagy is also emerging as being involved in the turnover of specific postsynaptic receptors, such as GABAA and AMPA, thus participating to the fine-tuning of synaptic strength and plasticity (Rowland et al., 2006; Shehata et al., 2012, 2018; Hui et al., 2019; Shen et al., 2020). Scaffolding postsynaptic proteins such as PSD95, PICK1, and SHANK3 are substrates of autophagic degradation as well, implying that a modulation of autophagy can impact on the structural remodeling of dendritic spines by acting on these targets (Nikoletopoulou et al., 2017).

Given that the endolysosomal and autophagic pathways are strictly interconnected, whether they cooperate or are independently regulated for the sorting and degradation of specific cargoes, both at the presynaptic and postsynaptic side, is a matter of investigation. An interesting aspect is that synaptic autophagy is stimulated in response to neuronal activity (Shehata et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015; Soukup et al., 2016; Hill et al., 2019), and may thus intervene under specific conditions. Along this line, recent evidence demonstrated that autophagy induction is required for activity-dependent structural and functional plasticity underlying novel memory formation in vivo (Glatigny et al., 2019). Lysosomes are also trafficked in an activity-dependent manner and can be recruited to dendritic spines upon local synaptic activation (Goo et al., 2017).

Further complicating the picture, besides their conventional function as degradative organelles, a subset of autophagosomes appears to act as signaling organelles able to retrogradely transport BDNF-activated TrkB receptors internalized at the presynapse toward the soma, thus unveiling a novel non-degradative role of autophagosomes at presynaptic boutons (Kononenko et al., 2017; Andres-Alonso et al., 2019).

Mitophagy

Mitochondria provide energy and proper calcium buffering essential for synaptic activities, especially SV recycling (Rangaraju et al., 2014), thus the maintenance of an healthy mitochondrial network is fundamental for neuronal homeostasis. Mitophagy is the selective degradation of damaged or excess mitochondria by autophagy, but mitochondrial fragments may be engulfed by autophagosomes also in a constitutive non-selective process (Maday et al., 2012). Mitophagy can occur in both cell body and distal axons (Cai et al., 2012; Ashrafi et al., 2014; Evans and Holzbaur, 2020). Important mediators of the process, at least under stress conditions, are the Parkinson’s-related proteins PINK1 (PTEN-induced kinase 1) and the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin, which target defective mitochondria for ubiquitination and thus promote the recruitment of ubiquitin-binding autophagy receptors, such as p62/SQSTM1 and optineurin, and of the autophagic machinery (Matsuda et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011). However, the evidence that loss of PINK1 or Parkin had no effect on basal mitophagy in vivo (Lee et al., 2018; McWilliams et al., 2018) suggested the existence of other PINK1/Parkin-independent mechanisms that cooperate in the clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria. Indeed, additional E3 ubiquitin ligases have been identified, as well as mitochondrial autophagic receptors, such as BNIP3, FUND1, and Bcl-2-L-13, which are expressed on the outer mitochondrial membrane and directly interact with LC3 to recruit the nascent phagophore on mitochondria (Villa et al., 2018). Along this line, an unconventional mitophagy receptor in neurons is the phospholipid cardiolipin: normally inserted in the inner mitochondrial membrane, it can be exposed on the mitochondrial surface upon mitochondrial depolarization and directly interacts with LC3 to recruit the autophagic machinery (Chu et al., 2013). Mitochondrial dysfunction and defective mitophagy have been described in various neurodegenerative diseases, including ALS, AD, and HD (Martinez-Vicente, 2017).

Aggrephagy

Since neurons are non-dividing cells, they are particularly vulnerable to the accumulation of damaged or misfolded proteins. The degradation of misfolded protein aggregates is achieved through a selective process called aggrephagy, but some of this clearance is, however, non-selective (Maday et al., 2012; Wong and Holzbaur, 2014a). Several autophagy receptors, able to bind both the degradative targets and the forming autophagosome, have been implicated in aggrephagy (e.g., p62/SQSTM1, optineurin, NBR1, and Ubiquilin-2) (Deng et al., 2017). The binding affinity of autophagy receptors to specific cargoes and to core members of the autophagy machinery is modulated by post-translational modifications of the receptors and by the interaction with autophagy adaptors, such as Huntingtin (Htt) and Alfy/WDFY3. This regulates the efficiency and specificity of aggregate clearance, in ubiquitin-dependent and -independent manners (Deng et al., 2017; Turco et al., 2019). The accumulation in neurons of aggregated pathogenic proteins such as α-synuclein, tau, Aβ, and mutant Huntingtin (mHtt) is a common feature of several neurodegenerative disorders and is related to dysfunctional selective autophagy. Accordingly, genetic mutations in some autophagy receptors have been associated with ALS and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (Deng et al., 2017). In this context, the modulation of specific autophagy receptors may represent a valuable strategy to improve the proteotoxic burden in these disorders.

Autophagy and Neurodegenerative Disorders

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of neurodegenerative dementia, characterized by the extracellular accumulation of amyloid plaques, composed primarily of Amyloid-β (Aβ), and intracellular tau tangles. Defective autophagy and endolysosomal function have been extensively documented as early events in AD, and variants in several genes involved in endosomal trafficking (SORL1, PICALM, CD2AP, BIN1, PLD3) have been recognized as genetic risk factors (Guimas Almeida et al., 2018). Autophagic vacuoles (AVs) and enlarged endosomes accumulate in the brain of AD patients and mouse models, especially in dystrophic neurites and synaptic terminals (Cataldo et al., 2000; Nixon et al., 2005; Yu et al., 2005), likely as a result of impaired AV retrograde transport, maturation and lysosomal clearance (Boland et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2010; Tammineni et al., 2017).

In PS1/APP mice, dystrophic neurites filled with AVs are associated with Aβ plaques (Sanchez-Varo et al., 2012). Indeed, the autophagic and endolysosomal networks have been recognized as crucial sites for APP processing by β- and γ-secretases and for Aβ generation and secretion (Yu et al., 2005; Nilsson et al., 2013; Whyte et al., 2017). The regulated trafficking of APP and secretases through the autophagic and endolysosomal pathways probably determines the net balance between Aβ production and APP/Aβ lysosomal degradation. The levels of the autophagy initiation factor Beclin1 are reduced in AD patient brains, and its depletion in APP transgenic mice decreases autophagy induction and promotes Aβ plaque deposition (Pickford et al., 2008). Vice-versa, Beclin1 mutation inducing constitutively active autophagy decreases Aβ plaque burden and memory deficits in AD mouse models (Rocchi et al., 2017), as does the enhancement of lysosomal activity (Yang et al., 2011; Xiao et al., 2015). Recent evidence indicates that AP-2 regulates the neuronal intracellular trafficking of the β-secretase BACE1 and promotes its delivery to lysosomes for degradation: conditional AP-2 knock-out mice show an accumulation of BACE1 in autophagosomes and endosomes and an increase in Aβ production (Bera et al., 2020). Accordingly, in APP transgenic mice, the enhancement of BACE1 retrograde transport decreases Aβ production and deposition, ameliorates synapse loss, and mitigates cognitive impairment (Ye et al., 2017). Interestingly, AP-2 levels are reduced in iPSC-derived neurons from AD patients (Bera et al., 2020).

Impaired mitophagy is also implicated in AD and results in the accumulation of damaged mitochondria in the hippocampus of AD patients. Mitophagy enhancement ameliorates memory impairment in AD animal models and, interestingly, reduces Aβ deposition and tau hyperphosphorylation (Fang et al., 2019).

Hence, growing evidence supports a role for autophagy and lysosomal enhancement as a therapeutic strategy in AD. Autophagy boosting through intracerebroventricular injection of the disaccharide trehalose (Du et al., 2013) or administration of mTOR-dependent autophagy activators, such as arctigenin, temsirolimus and rapamycin, showed positive effects in AD mouse models, by limiting Aβ production and plaque load and ameliorating cognitive deficits (Spilman et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2014). It cannot be underestimated, however, that this strategy may be beneficial only early in the disease (Majumder et al., 2011), when neuronal loss has not yet occurred. In addition, since in AD brains autophagosome clearance seems to be impaired, it is also possible that strong autophagy induction could exacerbate the already existing neuronal defects. In this sense, lysosomal potentiation (e.g., through viral-mediated overexpression of the lysosomal master regulator TFEB) might be advantageous (Xiao et al., 2015). Concerning the translation of these results to humans, a phase I clinical trial based on oral administration of rapamycin to patients with early onset AD is about to start (NCT04200911).

Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease is characterized by dopaminergic neuronal loss in the substantia nigra and formation of intracellular α-synuclein inclusions, known as Lewy bodies. α-synuclein is itself a substrate of autophagy, but compelling evidence has shown that α-synuclein aggregates directly alter the autophagic-lysosomal pathway. Reduced ATG7 and increased mTOR levels in patients’ brains and α-synuclein transgenic mice suggest a deficiency in autophagy initiation in neurons bearing α-synuclein inclusions (Crews et al., 2010). Consistent with that, α-synuclein overexpression in cell lines inhibits autophagosome biogenesis (Winslow et al., 2010). α-synuclein aggregates also disrupt the retrograde transport of AVs, thus impairing autophagosome maturation and fusion with lysosomes (Tanik et al., 2013; Volpicelli-Daley et al., 2014).

Genetic studies have identified several genes involved in autophagy and lysosomal biology as a risk factor for PD, including those encoding the lysosomal enzymes cathepsin B and glucocerebrosidase, the vacuolar ATPase subunit ATP6V0A1, and the lysosomal K+ channel TMEM175 (Chang et al., 2017). Moreover, many genes associated with familial PD, such as those encoding synaptojanin 1, LRRK2, the lysosomal ATPase ATP13A2 (or PARK9), PINK1 and Parkin, are involved in the autophagic and lysosomal pathways (Hunn et al., 2015; Beilina and Cookson, 2016). In particular, LRRK2 localizes to AVs and its knock-down promotes autophagy in cell lines (Alegre-Abarrategui et al., 2009), but the exact mechanism of autophagy regulation by LRRK2 remains unclear. Idiopathic PD brains and transgenic mice carrying LRRK2 mutations exhibit autophagic, endolysosomal and mitochondrial abnormalities (Ramonet et al., 2011; Rocha et al., 2020). Analogously, PD-related mutations in ATP13A2 cause an impairment of lysosomal function, thus promoting AV and α-synuclein accumulation (Dehay et al., 2012; Usenovic et al., 2012). Interestingly, ATP13A2 depletion causes the reduction of another PD-associated protein, synaptotagmin-11, and this in turn seems to be responsible for the impairment of lysosomal function and autophagosome clearance. Indeed, the overexpression of synaptotagmin-11 in ATP13A2 knocked-down cells rescued the autophagic flux, lysosomal function and α-synuclein clearance, indicating that the two PD-related proteins act in the same pathway (Bento et al., 2016).

Several strategies to boost autophagy and lysosomal function have been tested in PD models. As previously mentioned, a master regulator of the autophagy-lysosomal pathway is the transcription factor TFEB, whose nuclear localization is decreased in PD postmortem midbrains. Viral-mediated TFEB overexpression in a rat model of α-synuclein toxicity stimulated autophagy and lysosomal function, reduced α-synuclein oligomers and conferred neuroprotection to nigral dopaminergic neurons (Decressac et al., 2013). Similar results were obtained upon Beclin-1 gene transfer (Spencer et al., 2009; Decressac et al., 2013). Treatment of different animal models with autophagy-enhancing agents such as trehalose, metformin, rapamycin and temsirolimus efficiently attenuated motor dysfunctions, improved the survival of dopaminergic neurons and reduced α-synuclein aggregates (Crews et al., 2010; He et al., 2016; Lu et al., 2016; Siracusa et al., 2018). In addition, the fact that dopaminergic neurons seem to be particularly vulnerable to mitochondrial dysfunction and that two genes associated with familial PD, Parkin and PINK1, are involved in mitophagy suggests that the development of specific strategies to stimulate mitophagy may provide new therapeutic opportunities for PD (Bingol and Sheng, 2016).

Huntington’s Disease

Huntington’s disease is a polyglutamine (polyQ) disorder caused by a CAG expansion in the Huntingtin gene that renders the mutant protein prone to aggregation (Arrasate and Finkbeiner, 2012). Extensive evidence for autophagy dysfunction has been reported in HD. The expression of several autophagic markers is dysregulated in HD human brains (Martin et al., 2015), and the V471A polymorphism in ATG7, involved in autophagosome biogenesis, is associated with an earlier onset of HD in the Italian population (Metzger et al., 2013). Wild-type Htt (wtHtt) itself exerts several important functions in neuronal autophagy, as it interacts with various autophagic components (Ochaba et al., 2014). Htt is required for stress-induced selective autophagy, such as mitophagy and aggrephagy, as it facilitates cargo recognition and sequestration by interacting with the autophagy receptor p62 (Rui et al., 2015). Accordingly, the presence of empty autophagosomes and the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria has been reported in cellular and animal HD models (Martinez-Vicente et al., 2010; Franco-Iborra et al., 2020). Additionally, wtHtt interacts with the autophagy-activating kinase ULK1 and promotes its activation by interfering with the inhibitory binding of mTOR to ULK1 itself, thus regulating selective autophagy initiation (Rui et al., 2015). Furthermore, the protein is involved in the axonal retrograde transport of autophagosomes, which is disrupted in Htt-depleted neurons or neurons expressing the polyQ mHtt, thus leading to an accumulation of autophagosomes and to an inefficient cargo degradation (Wong and Holzbaur, 2014a).

From a therapeutic perspective, the modulation of autophagy showed promising effects in HD models. Autophagy stimulation with rapamycin decreased polyQ aggregates and attenuated HD in different models (Ravikumar et al., 2004; Sarkar et al., 2008). Trehalose also proved beneficial in HD mouse models (Tanaka et al., 2004), but the contribution of autophagy induction was not addressed in this study. Targeted therapies can also be envisaged and may represent a valid option for HD. In this sense, a recent elegant study identified a mHtt-LC3 linker compound that interacts with the expanded polyQ-tract of mHtt and promotes its selective autophagic degradation, while preserving wtHtt. This compound proved capable of rescuing relevant HD phenotypes in fly and mouse models of the disease (Li et al., 2019).

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is characterized by the progressive loss of motoneurons and by the accumulation of aggregated proteins such as TDP-43 or mutant SOD1 and FUS (Taylor et al., 2016). Familial and sporadic cases have been associated with mutations in genes encoding autophagy cargo receptors, such as p62/SQSTM1 and optineurin (Maruyama et al., 2010; Fecto et al., 2011; Rubino et al., 2012; Yilmaz et al., 2020). Various mutations in p62 are located in the ubiquitin-associated domain or in the LC3-interacting motif, pointing to impaired cargo recruitment to autophagosomes in ALS (Teyssou et al., 2013; Goode et al., 2016). Similarly, ALS-linked mutations in optineurin interfere with the clearance of protein inclusions and of damaged mitochondria in cell lines and neurons (Wong and Holzbaur, 2014b; Shen et al., 2015; Evans and Holzbaur, 2020). Along the same line, ALS mutations in the TBK1 kinase have also been identified (Cirulli et al., 2015; Freischmidt et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2020). TBK1 phosphorylates p62 and optineurin, thus increasing their ability to bind ubiquitinated proteins and enhancing the autophagic clearance of target proteins and mitochondria (Pilli et al., 2012; Matsumoto et al., 2015; Richter et al., 2016). TBK1 variants impact on these functions (Freischmidt et al., 2015; Foster et al., 2020). Additional genes mutated in ALS and involved in the autophagic pathway include Ubiquilin-2 and C9Orf72, the latter being affected by an intronic hexanucleotide repeat expansion that is the most common genetic abnormality in familial ALS (Deng et al., 2011; Renton et al., 2011). Ubiquilin-2 binds ubiquitinated proteins and is implicated in aggregate clearance through the proteasomal system (Hjerpe et al., 2016), but it also interacts with LC3 and with the ATP6V1G1 subunit of the vacuolar ATPase. Indeed, its depletion or mutation impair autophagosome maturation and acidification (N’Diaye et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2020). C9Orf72, in a complex with SMCR8 and WDR41, participates in autophagy initiation by activating Rab8a and Rab39b and regulating ULK1, and its loss in neurons leads to the accumulation of protein aggregates (Sellier et al., 2016; Webster et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2016). Puzzling results have shown, however, that C9Orf72 depletion reduces mTORC1 activity and increases lysosomal biogenesis at the transcriptional level, thus pointing to a negative role of C9Orf72 in the autophagic pathway (Ugolino et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2020). Lysosomal deficits, autophagosome accumulation, mitochondrial pathology and impaired retrograde transport of late endosomes have also been reported in the hSOD1G93A transgenic mouse model. Interestingly, boosting retrograde transport through the overexpression of the dynein adaptor snapin rescued these defects, improved motoneuron survival and reduced disease progression in this model (Xie et al., 2015).

Despite strong genetic evidence pointing to defective autophagy as a central mechanism in ALS, conflicting results have been obtained with the pharmacological modulation of this pathway in ALS models. Autophagy induction with rapamycin or other autophagy enhancers ameliorates TDP-43 clearance and neuronal survival in cellular and animal models, and significantly improves motor and cognitive dysfunctions in TDP-43 transgenic mice (Wang et al., 2012; Barmada et al., 2014). Conversely, rapamycin showed detrimental effects in hSOD1G93A mice (Zhang et al., 2011), while autophagy dampening through the heterozygous deletion of Beclin1 increases the life span of the SOD1G86R model (Nassif et al., 2014). mTOR-independent induction of autophagy with trehalose, instead, reduced protein aggregation, enhanced motoneuron survival, increased life span, and reduced disease progression in mutant SOD1 models (Castillo et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014).

Conclusion

In recent years there has been increasing demonstration of autophagy/endolysosomal dysfunction as a pathogenic mechanism shared by multiple neurodegenerative diseases, likely contributing to synaptic dysfunction and ultimately neuronal death. Interestingly, the selective vulnerability of different neuronal populations has been suggested to rely on intrinsic differences in the efficiency of these proteostasis systems (Diedrich et al., 2011; Tsvetkov et al., 2013). Still, in most cases we lack a thorough description of the molecular mechanisms by which specific disease-associated variants in autophagy genes may cause synaptic defects and, importantly, we lack a precise definition of the extent to which specific synaptic dysfunctions can be reverted by restoring autophagic function. This knowledge will probably be instrumental for the development of new and more specific drugs/approaches: autophagy induction alone may not be sufficient, or even detrimental in some cases, and the modulation of selective autophagic pathways may be advantageous compared to a perturbation of general autophagy.

Author Contributions

SG, FG, and MR wrote the first draft of the manuscript and prepared the figure. All authors participated to literature search, revised the text, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The reviewer FC declared a past co-authorship with one of the authors SG to the handling editor.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Elisa Savino (San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy) and Marco Gervasoni for their help with the artwork. The authors also thank Prof. Flavia Valtorta (San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy), Prof. Fabio Benfenati (Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Genoa, Italy), and Prof. Michele Simonato (University of Ferrara, Italy) for their support.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by Fondazione Cariplo, grant no. 2017-0784 to FG and SG.

References

- Alegre-Abarrategui J., Christian H., Lufino M. M. P., Mutihac R., Venda L. L., Ansorge O., et al. (2009). LRRK2 regulates autophagic activity and localizes to specific membrane microdomains in a novel human genomic reporter cellular model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18 4022–4034. 10.1093/hmg/ddp346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres-Alonso M., Ammar M. R., Butnaru I., Gomes G. M., Acuña Sanhueza G., Raman R., et al. (2019). SIPA1L2 controls trafficking and local signaling of TrkB-containing amphisomes at presynaptic terminals. Nat. Commun. 10:5448. 10.1038/s41467-019-13224-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrasate M., Finkbeiner S. (2012). Protein aggregates in Huntington’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 238 1–11. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi G., Schlehe J. S., LaVoie M. J., Schwarz T. L. (2014). Mitophagy of damaged mitochondria occurs locally in distal neuronal axons and requires PINK1 and Parkin. J. Cell Biol. 206 655–670. 10.1083/jcb.201401070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barmada S. J., Serio A., Arjun A., Bilican B., Daub A., Ando D. M., et al. (2014). Autophagy induction enhances TDP43 turnover and survival in neuronal ALS models. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10 677–685. 10.1038/nchembio.1563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beilina A., Cookson M. R. (2016). Genes associated with Parkinson’s disease: regulation of autophagy and beyond. J. Neurochem. 139 91–107. 10.1111/jnc.13266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bento C. F., Ashkenazi A., Jimenez-Sanchez M., Rubinsztein D. C. (2016). The Parkinson’s disease-associated genes ATP13A2 and SYT11 regulate autophagy via a common pathway. Nat. Commun. 7:11803. 10.1038/ncomms11803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bera S., Camblor-Perujo S., Calleja Barca E., Negrete-Hurtado A., Racho J., De Bruyckere E., et al. (2020). AP-2 reduces amyloidogenesis by promoting BACE1 trafficking and degradation in neurons. EMBO Rep. 21:e47954. 10.15252/embr.201947954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingol B. (2018). Autophagy and lysosomal pathways in nervous system disorders. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 91 167–208. 10.1016/j.mcn.2018.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingol B., Sheng M. (2016). Mechanisms of mitophagy: PINK1, Parkin, USP30 and beyond. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 100 210–222. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binotti B., Pavlos N. J., Riedel D., Wenzel D., Vorbrüggen G., Schalk A. M., et al. (2015). The GTPase Rab26 links synaptic vesicles to the autophagy pathway. eLife 4:e05597. 10.7554/eLife.05597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland B., Kumar A., Lee S., Platt F. M., Wegiel J., Yu W. H., et al. (2008). Autophagy induction and autophagosome clearance in neurons: relationship to autophagic pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 28 6926–6937. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0800-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Q., Zakaria H. M., Simone A., Sheng Z.-H. (2012). Spatial parkin translocation and degradation of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy in live cortical neurons. Curr. Biol. 22 545–552. 10.1016/j.cub.2012.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo K., Nassif M., Valenzuela V., Rojas F., Matus S., Mercado G., et al. (2013). Trehalose delays the progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by enhancing autophagy in motoneurons. Autophagy 9 1308–1320. 10.4161/auto.25188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo A. M., Peterhoff C. M., Troncoso J. C., Gomez-Isla T., Hyman B. T., Nixon R. A. (2000). Endocytic pathway abnormalities precede amyloid β deposition in sporadic alzheimer’s disease and down syndrome: differential effects of APOE genotype and presenilin mutations. Am. J. Pathol. 157 277–286. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64538-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang D., Nalls M. A., Hallgrímsdóttir I. B., Hunkapiller J., van der Brug M., Cai F., et al. (2017). A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies 17 new Parkinson’s disease risk loci. Nat. Genet. 49 1511–1516. 10.1038/ng.3955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X. T., Zhou B., Lin M. Y., Cai Q., Sheng Z. H. (2015). Axonal autophagosomes recruit dynein for retrograde transport through fusion with late endosomes. J. Cell Biol. 209 377–386. 10.1083/jcb.201412046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C. T., Ji J., Dagda R. K., Jiang J. F., Tyurina Y. Y., Kapralov A. A., et al. (2013). Cardiolipin externalization to the outer mitochondrial membrane acts as an elimination signal for mitophagy in neuronal cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 15 1197–1205. 10.1038/ncb2837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirulli E. T., Lasseigne B. N., Petrovski S., Sapp P. C., Dion P. A., Leblond C. S., et al. (2015). Exome sequencing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis identifies risk genes and pathways. Science 347 1436–1441. 10.1126/science.aaa3650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews L., Spencer B., Desplats P., Patrick C., Paulino A., Rockenstein E., et al. (2010). Selective molecular alterations in the autophagy pathway in patients with lewy body disease and in models of α-synucleinopathy. PLoS One 5:e9313. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Decressac M., Mattsson B., Weikop P., Lundblad M., Jakobsson J., Björklund A. (2013). TFEB-mediated autophagy rescues midbrain dopamine neurons from α-synuclein toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 E1817–E1826. 10.1073/pnas.1305623110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehay B., Ramirez A., Martinez-Vicente M., Perier C., Canron M. H., Doudnikoff E., et al. (2012). Loss of P-type ATPase ATP13A2/PARK9 function induces general lysosomal deficiency and leads to Parkinson disease neurodegeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 9611–9616. 10.1073/pnas.1112368109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deinhardt K., Salinas S., Verastegui C., Watson R., Worth D., Hanrahan S., et al. (2006). Rab5 and Rab7 control endocytic sorting along the axonal retrograde transport pathway. Neuron 52 293–305. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H. X., Chen W., Hong S. T., Boycott K. M., Gorrie G. H., Siddique N., et al. (2011). Mutations in UBQLN2 cause dominant X-linked juvenile and adult-onset ALS and ALS/dementia. Nature 477 211–215. 10.1038/nature10353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Z., Purtell K., Lachance V., Wold M. S., Chen S., Yue Z. (2017). Autophagy receptors and neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Cell Biol. 27 491–504. 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diedrich M., Kitada T., Nebrich G., Koppelstaetter A., Shen J., Zabel C., et al. (2011). Brain region specific mitophagy capacity could contribute to selective neuronal vulnerability in Parkinson’s disease. Proteome Sci. 9:59. 10.1186/1477-5956-9-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J., Liang Y., Xu F., Sun B., Wang Z. (2013). Trehalose rescues Alzheimer’s disease phenotypes in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 65 1753–1756. 10.1111/jphp.12108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers M. D. (2000). Reinsertion or degradation of AMPA receptors determined by activity-dependent endocytic sorting. Neuron 28 511–525. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00129-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans C. S., Holzbaur E. L. F. (2020). Degradation of engulfed mitochondria is rate-limiting in Optineurin-mediated mitophagy in neurons. eLife 9:e50260. 10.7554/eLife.50260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang E. F., Hou Y., Palikaras K., Adriaanse B. A., Kerr J. S., Yang B., et al. (2019). Mitophagy inhibits amyloid-β and tau pathology and reverses cognitive deficits in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 22 401–412. 10.1038/s41593-018-0332-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fecto F., Yan J., Vemula S. P., Liu E., Yang Y., Chen W., et al. (2011). SQSTM1 mutations in familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch. Neurol. 68 1440–1446. 10.1001/archneurol.2011.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes A. C., Uytterhoeven V., Kuenen S., Wang Y. C., Slabbaert J. R., Swerts J., et al. (2014). Reduced synaptic vesicle protein degradation at lysosomes curbs TBC1D24/sky-induced neurodegeneration. J. Cell Biol. 207 453–462. 10.1083/jcb.201406026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Monreal M., Brown T. C., Royo M., Esteban J. A. (2012). The balance between receptor recycling and trafficking toward lysosomes determines synaptic strength during long-term depression. J. Neurosci. 32 13200–13205. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0061-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster A. D., Downing P., Figredo E., Polain N., Stott A., Layfield R., et al. (2020). ALS-associated TBK1 variant p.G175S is defective in phosphorylation of p62 and impacts TBK1-mediated signalling and TDP-43 autophagic degradation. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 108:103539. 10.1016/j.mcn.2020.103539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco-Iborra S., Plaza-Zabala A., Montpeyo M., Sebastian D., Vila M., Martinez-Vicente M. (2020). Mutant HTT (huntingtin) impairs mitophagy in a cellular model of Huntington disease. Autophagy (in press). 10.1080/15548627.2020.1728096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freischmidt A., Wieland T., Richter B., Ruf W., Schaeffer V., Müller K., et al. (2015). Haploinsufficiency of TBK1 causes familial ALS and fronto-temporal dementia. Nat. Neurosci. 18 631–636. 10.1038/nn.4000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatigny M., Moriceau S., Rivagorda M., Ramos-Brossier M., Nascimbeni A. C., Lante F., et al. (2019). Autophagy is required for memory formation and reverses age-related memory decline. Curr. Biol. 29 435–448.e8. 10.1016/j.cub.2018.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goo M. S., Sancho L., Slepak N., Boassa D., Deerinck T. J., Ellisman M. H., et al. (2017). Activity-dependent trafficking of lysosomes in dendrites and dendritic spines. J. Cell Biol. 216 2499–2513. 10.1083/jcb.201704068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode A., Butler K., Long J., Cavey J., Scott D., Shaw B., et al. (2016). Defective recognition of LC3B by mutant SQSTM1/p62 implicates impairment of autophagy as a pathogenic mechanism in ALS-FTLD. Autophagy 12 1094–1104. 10.1080/15548627.2016.1170257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimas Almeida C., Sadat Mirfakhar F., Perdigão C., Burrinha T. (2018). Impact of late-onset Alzheimer’s genetic risk factors on beta-amyloid endocytic production. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 75 2577–2589. 10.1007/s00018-018-2825-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez M. G., Munafó D. B., Berón W., Colombo M. I. (2004). Rab7 is required for the normal progression of the autophagic pathway in mammalian cells. J. Cell Sci. 117 2687–2697. 10.1242/jcs.01114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T., Nakamura K., Matsui M., Yamamoto A., Nakahara Y., Suzuki-Migishima R., et al. (2006). Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature 441 885–889. 10.1038/nature04724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q., Koprich J. B., Wang Y., Yu W., Xiao B., Brotchie J. M., et al. (2016). Treatment with trehalose prevents behavioral and neurochemical deficits produced in an AAV α-synuclein rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 53 2258–2268. 10.1007/s12035-015-9173-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez D., Torres C. A., Setlik W., Cebrián C., Mosharov E. V., Tang G., et al. (2012). Regulation of presynaptic neurotransmission by macroautophagy. Neuron 74 277–284. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill S. E., Kauffman K. J., Krout M., Richmond J. E., Melia T. J., Colón-Ramos D. A. (2019). Maturation and clearance of autophagosomes in neurons depends on a specific cysteine protease Isoform, ATG-4.2. Dev. Cell 49 251–266.e8. 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjerpe R., Bett J. S., Keuss M. J., Solovyova A., McWilliams T. G., Johnson C., et al. (2016). UBQLN2 mediates autophagy-independent protein aggregate clearance by the proteasome. Cell 166 935–949. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann S., Orlando M., Andrzejak E., Bruns C., Trimbuch T., Rosenmund C., et al. (2019). Light-activated ROS production induces synaptic autophagy. J. Neurosci. 39 2163–2183. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1317-18.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui K. K., Takashima N., Watanabe A., Chater T. E., Matsukawa H., Nekooki-Machida Y., et al. (2019). GABARAPs dysfunction by autophagy deficiency in adolescent brain impairs GABAA receptor trafficking and social behavior. Sci. Adv. 5:eaau8237. 10.1126/sciadv.aau8237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunn B. H. M., Cragg S. J., Bolam J. P., Spillantini M. G., Wade-Martins R. (2015). Impaired intracellular trafficking defines early Parkinson’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 38 178–188. 10.1016/j.tins.2014.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T., Yu J. T., Zhu X. C., Tan M. S., Wang H. F., Cao L., et al. (2014). Temsirolimus promotes autophagic clearance of amyloid-β and provides protective effects in cellular and animal models of Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol. Res. 81 54–63. 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin E. J., Kiral F. R., Ozel M. N., Burchardt L. S., Osterland M., Epstein D., et al. (2018). Live observation of two parallel membrane degradation pathways at axon terminals. Curr. Biol. 28 1027–1038.e4. 10.1016/j.cub.2018.02.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M., Waguri S., Chiba T., Murata S., Iwata J., Tanida I., et al. (2006). Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature 441 880–884. 10.1038/nature04723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kononenko N. L., Claßen G. A., Kuijpers M., Puchkov D., Maritzen T., Tempes A., et al. (2017). Retrograde transport of TrkB-containing autophagosomes via the adaptor AP-2 mediates neuronal complexity and prevents neurodegeneration. Nat. Commun. 8:14819. 10.1038/ncomms14819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Yu W. H., Kumar A., Lee S., Mohan P. S., Peterhoff C. M., et al. (2010). Lysosomal proteolysis and autophagy require presenilin 1 and are disrupted by Alzheimer-related PS1 mutations. Cell 141 1146–1158. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. J., Sanchez-Martinez A., Zarate A. M., Benincá C., Mayor U., Clague M. J., et al. (2018). Basal mitophagy is widespread in Drosophila but minimally affected by loss of Pink1 or parkin. J. Cell Biol. 217 1613–1622. 10.1083/jcb.201801044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Sato Y., Nixon R. A. (2011). Lysosomal proteolysis inhibition selectively disrupts axonal transport of degradative organelles and causes an Alzheimer’s-like axonal dystrophy. J. Neurosci. 31 7817–7830. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6412-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Wang C., Wang Z., Zhu C., Li J., Sha T., et al. (2019). Allele-selective lowering of mutant HTT protein by HTT–LC3 linker compounds. Nature 575 203–209. 10.1038/s41586-019-1722-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y. (2019). Emerging concepts and functions of autophagy as a regulator of synaptic components and plasticity. Cells 8:34. 10.3390/cells8010034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., He J., Chen L., Zhang N., Tang L., Liu X., et al. (2020). TBK1 variants in Chinese patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol. Aging (in press). 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M., Su C., Qiao C., Bian Y., Ding J., Hu G. (2016). Metformin prevents dopaminergic neuron death in MPTP/P-induced mouse model of Parkinson’s disease via autophagy and mitochondrial ROS clearance. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 19:pyw047. 10.1093/ijnp/pyw047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüningschrör P., Binotti B., Dombert B., Heimann P., Perez-Lara A., Slotta C., et al. (2017). Plekhg5-regulated autophagy of synaptic vesicles reveals a pathogenic mechanism in motoneuron disease. Nat. Commun. 8:678. 10.1038/s41467-017-00689-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maday S., Holzbaur E. L. F. (2014). Autophagosome biogenesis in primary neurons follows an ordered and spatially regulated pathway. Dev. Cell 30 71–85. 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maday S., Wallace K. E., Holzbaur E. L. F. (2012). Autophagosomes initiate distally and mature during transport toward the cell soma in primary neurons. J. Cell Biol. 196 407–417. 10.1083/jcb.201106120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumder S., Richardson A., Strong R., Oddo S. (2011). Inducing autophagy by rapamycin before, but not after, the formation of plaques and tangles ameliorates cognitive deficits. PLoS One 6:e25416. 10.1371/journal.pone.0025416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D. D. O., Ladha S., Ehrnhoefer D. E., Hayden M. R. (2015). Autophagy in Huntington disease and huntingtin in autophagy. Trends Neurosci. 38 26–35. 10.1016/j.tins.2014.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Vicente M. (2017). Neuronal mitophagy in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 10:64. 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Vicente M., Talloczy Z., Wong E., Tang G., Koga H., Kaushik S., et al. (2010). Cargo recognition failure is responsible for inefficient autophagy in Huntington’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 13 567–576. 10.1038/nn.2528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama H., Morino H., Ito H., Izumi Y., Kato H., Watanabe Y., et al. (2010). Mutations of optineurin in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature 465 223–226. 10.1038/nature08971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda N., Sato S., Shiba K., Okatsu K., Saisho K., Gautier C. A., et al. (2010). PINK1 stabilized by mitochondrial depolarization recruits Parkin to damaged mitochondria and activates latent Parkin for mitophagy. J. Cell Biol. 189 211–221. 10.1083/jcb.200910140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto G., Shimogori T., Hattori N., Nukina N. (2015). TBK1 controls autophagosomal engulfment of polyubiquitinated mitochondria through p62/SQSTM1 phosphorylation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24 4429–4442. 10.1093/hmg/ddv179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams T. G., Prescott A. R., Montava-Garriga L., Ball G., Singh F., Barini E., et al. (2018). Basal mitophagy occurs independently of PINK1 in mouse tissues of high metabolic demand. Cell Metab. 27 439–449.e5. 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger S., Walter C., Riess O., Roos R. A. C., Nielsen J. E., Craufurd D., et al. (2013). The V471A polymorphism in autophagy-related gene ATG7 Modifies age at onset specifically in italian huntington disease patients. PLoS One 8:e68951. 10.1371/journal.pone.0068951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch J. D., Rostosky C. M., Gowrisankaran S., Arora A. S., Soukup S. F., Vidal R., et al. (2016). Endophilin-A deficiency induces the Foxo3a-Fbxo32 network in the brain and causes dysregulation of autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Cell Rep. 17 1071–1086. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassif M., Valenzuela V., Rojas-Rivera D., Vidal R., Matus S., Castillo K., et al. (2014). Pathogenic role of BECN1/Beclin 1 in the development of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Autophagy 10 1256–1271. 10.4161/auto.28784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- N’Diaye E. N., Kajihara K. K., Hsieh I., Morisaki H., Debnath J., Brown E. J. (2009). PLIC proteins or ubiquilins regulate autophagy-dependent cell survival during nutrient starvation. EMBO Rep. 10 173–179. 10.1038/embor.2008.238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoletopoulou V., Sidiropoulou K., Kallergi E., Dalezios Y., Tavernarakis N. (2017). Modulation of autophagy by BDNF underlies synaptic plasticity. Cell Metab. 26 230–242.e5. 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson P., Loganathan K., Sekiguchi M., Matsuba Y., Hui K., Tsubuki S., et al. (2013). Aβ secretion and plaque formation depend on autophagy. Cell Rep. 5 61–69. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon R. A., Wegiel J., Kumar A., Yu W. H., Peterhoff C., Cataldo A., et al. (2005). Extensive involvement of autophagy in Alzheimer disease: an immuno-electron microscopy study. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 64 113–122. 10.1093/jnen/64.2.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochaba J., Lukacsovich T., Csikos G., Zheng S., Margulis J., Salazar L., et al. (2014). Potential function for the Huntingtin protein as a scaffold for selective autophagy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 16889–16894. 10.1073/pnas.1420103111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okerlund N. D., Schneider K., Leal-Ortiz S., Montenegro-Venegas C., Kim S. A., Garner L. C., et al. (2017). Bassoon controls presynaptic autophagy through Atg5. Neuron 93 897–913.e7. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickford F., Masliah E., Britschgi M., Lucin K., Narasimhan R., Jaeger P. A., et al. (2008). The autophagy-related protein beclin 1 shows reduced expression in early Alzheimer disease and regulates amyloid β accumulation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 118 2190–2199. 10.1172/JCI33585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilli M., Arko-Mensah J., Ponpuak M., Roberts E., Master S., Mandell M. A., et al. (2012). TBK-1 promotes autophagy-mediated antimicrobial defense by controlling autophagosome maturation. Immunity 37 223–234. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramonet D., Daher J. P. L., Lin B. M., Stafa K., Kim J., Banerjee R., et al. (2011). Dopaminergic neuronal loss, reduced neurite complexity and autophagic abnormalities in transgenic mice expressing G2019S mutant LRRK2. PLoS One 6:e18568. 10.1371/journal.pone.0018568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangaraju V., Calloway N., Ryan T. A. (2014). Activity-driven local ATP synthesis is required for synaptic function. Cell 156 825–835. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B., Vacher C., Berger Z., Davies J. E., Luo S., Oroz L. G., et al. (2004). Inhibition of mTOR induces autophagy and reduces toxicity of polyglutamine expansions in fly and mouse models of Huntington disease. Nat. Genet. 36 585–595. 10.1038/ng1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renton A. E., Majounie E., Waite A., Simón-Sánchez J., Rollinson S., Gibbs J. R., et al. (2011). A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 72 257–268. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter B., Sliter D. A., Herhaus L., Stolz A., Wang C., Beli P., et al. (2016). Phosphorylation of OPTN by TBK1 enhances its binding to Ub chains and promotes selective autophagy of damaged mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 4039–4044. 10.1073/pnas.1523926113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocchi A., Yamamoto S., Ting T., Fan Y., Sadleir K., Wang Y., et al. (2017). A Becn1 mutation mediates hyperactive autophagic sequestration of amyloid oligomers and improved cognition in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS Genet. 13:e1006962. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha E. M., De Miranda B. R., Castro S., Drolet R., Hatcher N. G., Yao L., et al. (2020). LRRK2 inhibition prevents endolysosomal deficits seen in human Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 134:104626. 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland A. M., Richmond J. E., Olsen J. G., Hall D. H., Bamber B. A. (2006). Presynaptic terminals independently regulate synaptic clustering and autophagy of GABAA receptors in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci. 26 1711–1720. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2279-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino E., Rainero I., Chiò A., Rogaeva E., Galimberti D., Fenoglio P., et al. (2012). SQSTM1 mutations in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology, 79 1556–1562. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826e25df [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui Y. N., Xu Z., Patel B., Chen Z., Chen D., Tito A., et al. (2015). Huntingtin functions as a scaffold for selective macroautophagy. Nat. Cell Biol. 17 262–275. 10.1038/ncb3101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Varo R., Trujillo-Estrada L., Sanchez-Mejias E., Torres M., Baglietto-Vargas D., Moreno-Gonzalez I., et al. (2012). Abnormal accumulation of autophagic vesicles correlates with axonal and synaptic pathology in young Alzheimer’s mice hippocampus. Acta Neuropathol. 123 53–70. 10.1007/s00401-011-0896-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S., Krishna G., Imarisio S., Saiki S., O’Kane C. J., Rubinsztein D. C. (2008). A rational mechanism for combination treatment of Huntington’s disease using lithium and rapamycin. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17 170–178. 10.1093/hmg/ddm294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellier C., Campanari M., Julie Corbier C., Gaucherot A., Kolb-Cheynel I., Oulad-Abdelghani M., et al. (2016). Loss of C9ORF72 impairs autophagy and synergizes with polyQ Ataxin-2 to induce motor neuron dysfunction and cell death. EMBO J. 35 1276–1297. 10.15252/embj.201593350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan P., Zhu M., Beskow A., Vollmer C., Waites C. L. (2016). Activity-dependent degradation of synaptic vesicle proteins requires Rab35 and the ESCRT pathway. J. Neurosci. 36 8668–8686. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0725-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehata M., Abdou K., Choko K., Matsuo M., Nishizono H., Inokuchi K. (2018). Autophagy enhances memory erasure through synaptic destabilization. J. Neurosci. 38 3809–3822. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3505-17.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehata M., Matsumura H., Okubo-Suzuki R., Ohkawa N., Inokuchi K. (2012). Neuronal stimulation induces autophagy in hippocampal neurons that is involved in AMPA receptor degradation after chemical long-term depression. J. Neurosci. 32 10413–10422. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4533-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H., Zhu H., Panja D., Gu Q., Li Z. (2020). Autophagy controls the induction and developmental decline of NMDAR-LTD through endocytic recycling. Nat. Commun. 11:2979. 10.1038/s41467-020-16794-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W., Ganetzky B. (2009). Autophagy promotes synapse development in Drosophila. J. Cell Biol. 187 71–79. 10.1083/jcb.200907109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W. C., Li H. Y., Chen G. C., Chern Y., Tu P. H. (2015). Mutations in the ubiquitin-binding domain of OPTN/optineurin interfere with autophagy-mediated degradation of misfolded proteins by a dominant-negative mechanism. Autophagy 11 685–700. 10.4161/auto.36098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siracusa R., Paterniti I., Cordaro M., Crupi R., Bruschetta G., Campolo M., et al. (2018). Neuroprotective effects of temsirolimus in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 55 2403–2419. 10.1007/s12035-017-0496-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukup S. F., Kuenen S., Vanhauwaert R., Manetsberger J., Hernández-Díaz S., Swerts J., et al. (2016). A LRRK2-dependent endophilinA phosphoswitch is critical for macroautophagy at presynaptic terminals. Neuron 92 829–844. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer B., Potkar R., Trejo M., Rockenstein E., Patrick C., Gindi R., et al. (2009). Beclin 1 gene transfer activates autophagy and ameliorates the neurodegenerative pathology in α-synuclein models of Parkinson’s and Lewy body diseases. J. Neurosci. 29 13578–13588. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4390-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spilman P., Podlutskaya N., Hart M. J., Debnath J., Gorostiza O., Bredesen D., et al. (2010). Inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin abolishes cognitive deficits and reduces amyloid-β levels in a mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 5:e9979. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavoe A. K. H., Hill S. E., Hall D. H., Colón-Ramos D. A. (2016). KIF1A/UNC-104 transports ATG-9 to regulate neurodevelopment and autophagy at synapses. Dev. Cell 38 171–185. 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammineni P., Ye X., Feng T., Aikal D., Cai Q. (2017). Impaired retrograde transport of axonal autophagosomes contributes to autophagic stress in Alzheimer’s disease neurons. eLife 6:e21776. 10.7554/eLife.21776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M., Machida Y., Niu S., Ikeda T., Jana N. R., Doi H., et al. (2004). Trehalose alleviates polyglutamine-mediated pathology in a mouse model of Huntington disease. Nat. Med. 10 148–154. 10.1038/nm985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang G., Gudsnuk K., Kuo S. H., Cotrina M. L., Rosoklija G., Sosunov A., et al. (2014). Loss of mTOR-dependent macroautophagy causes autistic-like synaptic pruning deficits. Neuron 83 1131–1143. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanik S. A., Schultheiss C. E., Volpicelli-Daley L. A., Brunden K. R., Lee V. M. Y. (2013). Lewy body-like α-synuclein aggregates resist degradation and impair macroautophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 288 15194–15210. 10.1074/jbc.M113.457408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J. P., Brown R. H., Cleveland D. W. (2016). Decoding ALS: from genes to mechanism. Nature 539 197–206. 10.1038/nature20413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teyssou E., Takeda T., Lebon V., Boillée S., Doukouré B., Bataillon G., et al. (2013). Mutations in SQSTM1 encoding p62 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: genetics and neuropathology. Acta Neuropathol. 125 511–522. 10.1007/s00401-013-1090-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y., Chang J. C., Fan E. Y., Flajolet M., Greengard P. (2013). Adaptor complex AP2/PICALM, through interaction with LC3, targets Alzheimer’s APP-CTF for terminal degradation via autophagy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 17071–17076. 10.1073/pnas.1315110110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsvetkov A. S., Arrasate M., Barmada S., Ando D. M., Sharma P., Shaby B. A., et al. (2013). Proteostasis of polyglutamine varies among neurons and predicts neurodegeneration. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9 586–592. 10.1038/nchembio.1308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turco E., Witt M., Abert C., Bock-Bierbaum T., Su M. Y., Trapannone R., et al. (2019). FIP200 claw domain binding to p62 promotes autophagosome formation at ubiquitin condensates. Mol. Cell 74 330–346.e11. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.01.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugolino J., Ji Y. J., Conchina K., Chu J., Nirujogi R. S., Pandey A., et al. (2016). Loss of C9orf72 enhances autophagic activity via deregulated mTOR and TFEB signaling. PLoS Genet. 12:e1006443. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usenovic M., Tresse E., Mazzulli J. R., Taylor J. P., Krainc D. (2012). Deficiency of ATP13A2 leads to lysosomal dysfunction, α-synuclein accumulation, and neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 32 4240–4246. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5575-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uytterhoeven V., Kuenen S., Kasprowicz J., Miskiewicz K., Verstreken P. (2011). Loss of Skywalker reveals synaptic endosomes as sorting stations for synaptic vesicle proteins. Cell 145 117–132. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uytterhoeven V., Lauwers E., Maes I., Miskiewicz K., Melo M. N., Swerts J., et al. (2015). Hsc70-4 deforms membranes to promote synaptic protein turnover by endosomal microautophagy. Neuron 88 735–748. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhauwaert R., Kuenen S., Masius R., Bademosi A., Manetsberger J., Schoovaerts N., et al. (2017). The SAC1 domain in synaptojanin is required for autophagosome maturation at presynaptic terminals. EMBO J. 36 1392–1411. 10.15252/embj.201695773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa E., Marchetti S., Ricci J.-E. (2018). No Parkin Zone: mitophagy without Parkin. Trends Cell Biol. 28 882–895. 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli-Daley L. A., Gamble K. L., Schultheiss C. E., Riddle D. M., West A. B., Lee V. M. Y. (2014). Formation of α-synuclein lewy neurite-like aggregates in axons impedes the transport of distinct endosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell 25 4010–4023. 10.1091/mbc.E14-02-0741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang I. F., Guo B. S., Liu Y. C., Wu C. C., Yang C. H., Tsai K. J., et al. (2012). Autophagy activators rescue and alleviate pathogenesis of a mouse model with proteinopathies of the TAR DNA-binding protein 43. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 15024–15029. 10.1073/pnas.1206362109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Wang H., Tao Z., Xia Q., Hao Z., Prehn J. H. M., et al. (2020). C9orf72 associates with inactive Rag GTPases and regulates mTORC1-mediated autophagosomal and lysosomal biogenesis. Aging Cell 19:e13126. 10.1111/acel.13126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Martin S., Papadopulos A., Harper C. B., Mavlyutov T. A., Niranjan D., et al. (2015). Control of autophagosome axonal retrograde flux by presynaptic activity unveiled using botulinum neurotoxin type A. J. Neurosci. 35 6179–6194. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3757-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Winter D., Ashrafi G., Schlehe J., Wong Y. L., Selkoe D., et al. (2011). PINK1 and Parkin target Miro for phosphorylation and degradation to arrest mitochondrial motility. Cell 147 893–906. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. C., Lauwers E., Verstreken P. (2017). Presynaptic protein homeostasis and neuronal function. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 44 38–46. 10.1016/j.gde.2017.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster C. P., Smith E. F., Bauer C. S., Moller A., Hautbergue G. M., Ferraiuolo L., et al. (2016). The C9orf72 protein interacts with Rab1a and the ULK1 complex to regulate initiation of autophagy. EMBO J. 35 1656–1676. 10.15252/embj.201694401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertz M. H., Mitchem M. R., Pineda S. S., Hachigian L. J., Lee H., Lau V., et al. (2020). Genome-wide in vivo CNS screening identifies genes that modify CNS neuronal survival and mHTT toxicity. Neuron 106 76–89.e8. 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte L. S., Lau A. A., Hemsley K. M., Hopwood J. J., Sargeant T. J. (2017). Endo-lysosomal and autophagic dysfunction: A driving factor in Alzheimer’s disease? J. Neurochem. 140 703–717. 10.1111/jnc.13935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winckler B., Faundez V., Maday S., Cai Q., Almeida C. G., Zhang H. (2018). The endolysosomal system and proteostasis: from development to degeneration. J. Neurosci. 38 9364–9374. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1665-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow A. R., Chen C. W., Corrochano S., Acevedo-Arozena A., Gordon D. E., Peden A. A., et al. (2010). α-Synuclein impairs macroautophagy: implications for Parkinson’s disease. J. Cell Biol. 190 1023–1037. 10.1083/jcb.201003122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Y. C., Holzbaur E. L. F. (2014a). The regulation of autophagosome dynamics by huntingtin and HAP1 is disrupted by expression of mutant huntingtin, leading to defective cargo degradation. J. Neurosci. 34 1293–1305. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1870-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Y. C., Holzbaur E. L. F. (2014b). Optineurin is an autophagy receptor for damaged mitochondria in parkin-mediated mitophagy that is disrupted by an ALS-linked mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 E4439–E4448. 10.1073/pnas.1405752111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. J., Cai A., Greenslade J. E., Higgins N. R., Fan C., Le N. T. T., et al. (2020). ALS/FTD mutations in UBQLN2 impede autophagy by reducing autophagosome acidification through loss of function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117 15230–15241. 10.1073/pnas.1917371117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q., Yan P., Ma X., Liu H., Perez R., Zhu A., et al. (2015). Neuronal-targeted TFEB accelerates lysosomal degradation of APP, reducing Aβ generation and amyloid plaque pathogenesis. J. Neurosci. 35 12137–12151. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0705-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., Zhou B., Lin M. Y., Wang S., Foust K. D., Sheng Z. H. (2015). Endolysosomal deficits augment mitochondria pathology in spinal motor neurons of asymptomatic fALS mice. Neuron 87 355–370. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D. S., Stavrides P., Mohan P. S., Kaushik S., Kumar A., Ohno M., et al. (2011). Reversal of autophagy dysfunction in the TgCRND8 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease ameliorates amyloid pathologies and memory deficits. Brain 134 258–277. 10.1093/brain/awq341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., Chen L., Swaminathan K., Herrlinger S., Lai F., Shiekhattar R., et al. (2016). A C9ORF72/SMCR8-containing complex regulates ULK1 and plays a dual role in autophagy. Sci. Adv. 2:e1601167. 10.1126/sciadv.1601167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X., Feng T., Tammineni P., Chang Q., Jeong Y. Y., Margolis D. J., et al. (2017). Regulation of synaptic amyloid-β generation through bace1 retrograde transport in a mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 37 2639–2655. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2851-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz R., Müller K., Brenner D., Volk A. E., Borck G., Hermann A., et al. (2020). SQSTM1/p62 variants in 486 patients with familial ALS from Germany and Sweden. Neurobiol. Aging 87 139.e9–139.e15. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W. H., Cuervo A. M., Kumar A., Peterhoff C. M., Schmidt S. D., Lee J. H., et al. (2005). Macroautophagy - A novel β-amyloid peptide-generating pathway activated in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cell Biol. 171 87–98. 10.1083/jcb.200505082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Chen S., Song L., Tang Y., Shen Y., Jia L., et al. (2014). MTOR-independent, autophagic enhancer trehalose prolongs motor neuron survival and ameliorates the autophagic flux defect in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Autophagy 10 588–602. 10.4161/auto.27710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Li L., Chen S., Yang D., Wang Y., Zhang X., et al. (2011). Rapamycin treatment augments motor neuron degeneration in SOD1 G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Autophagy 7 412–425. 10.4161/auto.7.4.14541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng N., Jeyifous O., Munro C., Montgomery J. M., Green W. N. (2015). Synaptic activity regulates AMPA receptor trafficking through different recycling pathways. eLife 4:e06878. 10.7554/eLife.06878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z., Yan J., Jiang W., Yao X. G., Chen J., Chen L., et al. (2013). Arctigenin effectively ameliorates memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease model mice targeting both β-amyloid production and clearance. J. Neurosci. 33 13138–13149. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4790-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]