Highlights

-

•

Now that laparoscopic surgery is widespread, minimally invasive surgery is desired.

-

•

Natural orifice specimen extraction is minimally invasive surgery.

-

•

Transanal specimen extraction and transvaginal specimen extraction.

-

•

Natural orifice specimen extraction appears to be feasible and safe.

Abbreviations: NOSE, natural orifice specimen extraction; OABP, oral antibiotic bowel preparation; VAS, visual analogue scale; TASE, transanal specimen extraction; TVSE, transvaginal specimen extraction; DST, double stapling technique

Keywords: Colon cancer, Laparoscopic surgery, Natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE), Case series

Abstract

Introduction

In recent years, natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) has been attracting attention as a further minimally invasive operation for colorectal cancer, and not only improvement of appearance, but also reduction of pain and wound-related complications due to abdominal wall destruction has been reported. However, NOSE is technically complicated and difficult, and it has not yet been widely used. The aim of this study was to confirm the feasibility, safety, and short-term outcomes of total laparoscopic colon cancer surgery with NOSE.

Case presentation

From May 2018 to October 2019, eight patients with stage 0 or I colon cancer underwent NOSE surgery in our hospital. Transanal specimen extraction was performed in six cases, and transvaginal specimen extraction was performed in two cases. All operations were successfully accomplished without conversion to open surgery. The anastomosis method was double stapling technique in three cases and overlap method in five cases. The median operative time was 224 min. The median blood loss was 10 mL. The median time to first flatus was 1 day, and the median time to first stool was 2 days. The median postoperative observation period was 18 months, but there was no recurrence. There were no postoperative complications in these cases.

Conclusion

Total laparoscopic colon cancer surgery with NOSE appears to be feasible, safe, and show promising efficacy for selected patients.

1. Introduction

With the widespread use of laparoscopic surgery, further minimally invasive surgery is desired. Conventional laparoscopic colorectal surgery requires abdominal minilaparotomy for extraction of the specimen. However, the laparotomy incision often causes postoperative pain, wound infection, and incisional hernia [[1], [2], [3]]. In recent years, natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) has been attracting attention as a further minimally invasive operation for colorectal cancer, and not only improvement of appearance, but also reduction of pain and wound-related complications due to abdominal wall destruction has been reported [[4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]]. However, NOSE is technically complicated and difficult, and it has not yet been widely used. The aim of this study was to verify the feasibility, safety, and short-term outcomes of total laparoscopic colon cancer surgery with NOSE. This paper has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [11].

2. Case presentation

More than 100 cases of totally laparoscopic surgery with intracorporeal anastomosis were performed in our department by May 2018, and the procedure has been established. Leveraging these experiences led to the introduction of NOSE. This study was a prospective study conducted by a single operator at a single institution. The operator is a specialist with over ten years of experience in laparoscopic colorectal surgery. From May 2018 to December 2019, NOSE surgery was performed on eight patients with consent for this surgery for TNM stage 0 or stage I colon cancer. Of the eight cases, four were men and four were women. In four cases, the lesion had undergone endoscopic mucosal resection before surgery (Table 1). All patients were fully informed of the study design according to the Ethics Committee on Clinical Investigation of Osaka Medical College Hospital, which approved the protocol (No. 2017-161), and provided their written, informed consent to participate.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics (n = 8).

| Case | Age (year) | Sex | BMI (kg/m2) | ASA | Medical history | Abdominal operation history | Tumor location | Histological type | Preoperative treatment history | Stage* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51 | Male | 23.5 | 2 | None | None | Sigmoid colon | tub1 | EMR | Ⅰ |

| 2 | 53 | Male | 22.8 | 1 | None | None | Descending colon | tub1 | EMR | Ⅰ |

| 3 | 62 | Female | 23.1 | 1 | None | 2 | Sigmoid colon | tub1 | EMR | Ⅰ |

| 4 | 73 | Female | 22.6 | 1 | Cervical cancer | None | Cecum | tub1 | None | 0 |

| 5 | 67 | Female | 16.9 | 2 | None | None | Sigmoid colon | tub1 | EMR | Ⅰ |

| 6 | 83 | Male | 21.0 | 2 | Hypertension, Cerebral infarction | 1 | Descending colon | tub1 | None | Ⅰ |

| 7 | 66 | Female | 28.9 | 1 | Dyslipidemia | None | Ascending colon | tub1 | EMR | Ⅰ |

| 8 | 63 | Male | 18.2 | 1 | None | None | Sigmoid colon | tub1 | None | Ⅰ |

BMI: Body mass index. ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists.

EMR: Endoscopic mucosal resection.

Clinical stage is classified by UICC-8 staging.

The standard procedures, such as skin preparation, antibiotic prophylaxis, surgical technique, and wound closure, were similar for all patients. Preoperatively, all patients received routine mechanical bowel preparation combined with oral antibiotic bowel preparation (OABP). The OABP involved kanamycin plus metronidazole only on the day before surgery. Cefmetazole sodium (1 g/dose) was given intravenously 30 min before surgery and at 3 h intervals thereafter only on the operative day. Postoperative analgesia was maintained by continuous fentanyl infusion for 48 h. Intravenous infusion of flurbiprofen or oral administration of loxoprofen was used as an additional analgesic at the patient’s request. Pain was assessed using the visual analogue scale (VAS) and the number of additional analgesics from the operation day to the 3rd postoperative day.

3. Surgical technique

Tumour-specific mesenteric excision was performed as a standard surgical technique. The colon was resected intracorporeally using a 60-mm, linear laparoscopic stapler. Specimens were removed by transanal specimen extraction (TASE) or transvaginal specimen extraction (TVSE).

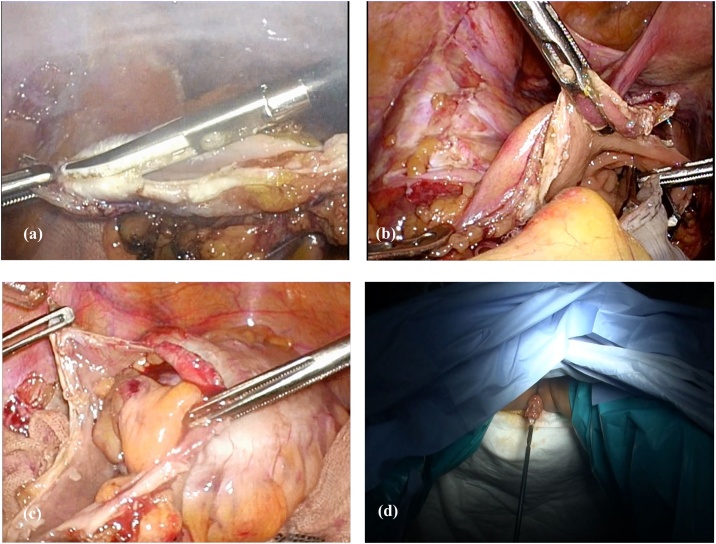

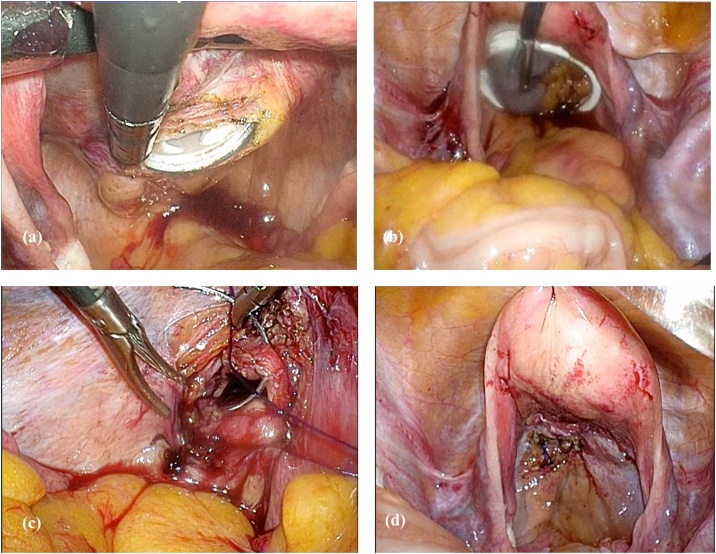

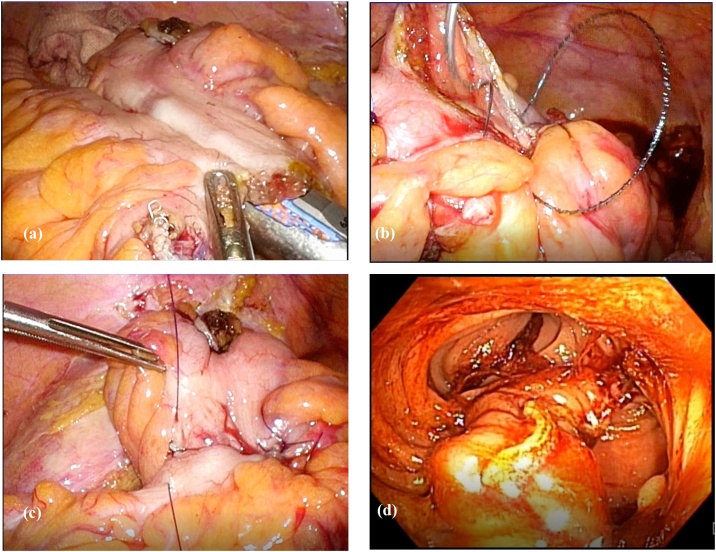

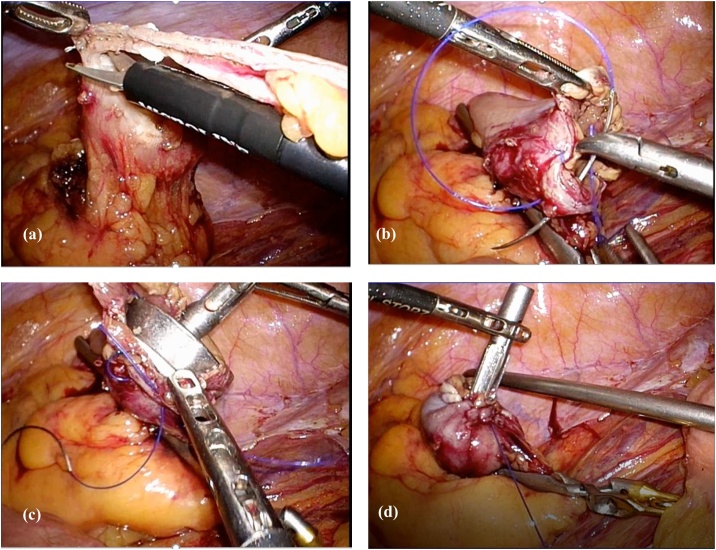

In cases of TASE, the staple at the stump of the anal side intestine was excised, and the specimen was removed with forceps inserted from the anal. The open intestinal stump was closed again using a 60-mm, linear laparoscopic stapler (Fig. 1). In cases of TVSE, the posterior vaginal vault was opened using the pipe inserted from the vagina as a guide, and the specimen was extracted with forceps inserted from the vagina. The opened posterior vaginal vault was closed by continuous suturing with 3-0 Vicryl (Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH, USA) (Fig. 2). An anastomosis was performed after removing the specimen. The anastomosis method was the overlap method or the double stapling technique (DST) method. The overlap method was performed by firing one 60-mm linear stapler load in an isoperistaltic side-to-side manner. The enterotomy was closed with the Albert-Lembert method, continuous suture using a 3-0 V-Loc (Medtronic, USA) and interrupted suture using 3-0 PDS (Ethicon) (Fig. 3). In cases using the DST method, the anvil head was inserted from the 12-mm port wound or anus. The staple at the stump of the oral side intestine was excised, and purse string suture was performed using 2-0 prolene (Ethicon). The anvil head was inserted into the open stump and tied down. The circular endostapler (Intraluminal stapler/ILS Ethicon) was introduced through the anus, and anastomosis was performed (Fig. 4). A leakage test was routinely carried out by colonoscopic instillation of air.

Fig. 1.

Transanal specimen extraction.

(a) The staple at the stump of the anal side intestine is excised.

(b) Inserting forceps through the anus.

(c) Carefully pulling the specimen into the intestinal tract.

(d) The specimen is removed from the anal canal.

Fig. 2.

Transvaginal specimen extraction.

(a) The posterior vaginal vault is opened using the pipe inserted from the vagina as a guide.

(b) The specimen is extracted with forceps inserted from the vagina.

(c) The opened posterior vaginal vault is closed by continuous suturing with 3-0 Vicryl (Ethicon).

(d) Posterior vaginal vault after suture closure.

Fig. 3.

Anastomosis by the overlap method.

(a) Firing one 60-mm linear stapler load in an isoperistaltic side-to-side manner.

(b) The enterotomy is closed with the Albert method, with continuous suture using a 3-0 V-Loc (Medtronic).

(c) Further reinforcement is closed with interrupted sutures using 3-0 PDS (Ethicon) in the Lembert method.

(d) Endoscopic image of the anastomosis site.

Fig. 4.

Anastomosis by the double stapling technique.

(a) The staple at the stump of the oral side intestine is excised.

(b) Purse string suture using 2-0 prolene (Ethicon) in the abdominal cavity.

(c) Inserting the anvil head into the open stump.

(d) Tying the thread and fixing the anvil head. A circular endostapler (intraluminal stapler/ILS, Ethicon) is introduced through the anus, and anastomosis is performed.

The peritoneal cavity was thoroughly washed with warm saline. A drainage tube was not placed. Peritoneal fluid samples were collected under sterile conditions before anastomosis and after intraperitoneal lavage and sent for cultures and cytologic examination. This case series has been reported in line with the PROCESS Guideline [12].

All operations were successfully completed. TASE was performed in 6 cases, and TVSE was performed in 2 cases. One case of TVSE was single-incision laparoscopic surgery. The anastomosis method was DST in 3 cases and the overlap method in 5 cases. Cytologic examination was negative both times. Bacterial and fungal cultures at the time when the anastomosis was performed to thoroughly wash the abdominal cavity detected bacteria in 3 of 8 cases. There were no postoperative complications in these cases. The median time to first flatus was 1 day, and the median time to first stool was 2 days (Table 2). From the second day after surgery, the VAS scale dropped below 30 (Table 3). The median postoperative observation period was two years, and there have been no recurrences.

Table 2.

Operative results.

| Case | Viscerotomy site | Anastomosis | Operation time (min) | Blood loss (ml) | CY (before*) | CY (after**) | Fluid culture (before*) | Fluid culture (after**) | First flatus (days) | First stool (days) | Postoperative length of stay (days) | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TASE | Overlap | 204 | 10 | – | – | – | Candida albicans | 1 | 3 | 10 | None |

| 2 | TASE | Overlap | 236 | 10 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | 8 | None |

| 3 | TASE | DST | 221 | 10 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 3 | 10 | None |

| 4 | TVSE | Overlap | 258 | 10 | – | – | – | Enterococcus faecalis | 1 | 4 | 13 | None |

| 5 | TASE | DST | 179 | 10 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | 10 | None |

| 6 | TASE | Overlap | 226 | 10 | – | – | – | Enterococcus faecium, Clostridium species | 1 | 1 | 9 | None |

| 7 | TVSE (SILS) | Overlap | 303 | 10 | – | – | – | – | 2 | 2 | 10 | None |

| 8 | TASE | DST | 174 | 10 | – | – | – | – |

SILS: Single incision laparoscopic surgery. CY: Cytologic examination.

Before anastomosis.

After intraperitoneal lavage.

Table 3.

Postoperative pain outcomes.

| TASE | TVSE | |

|---|---|---|

| Pain scale (VAS score) | ||

| Day 0 | 43 (0–80) | 45 (40–50) |

| Day 1 | 35 (10–60) | 40 (40–40) |

| Day 2 | 18 (0–40) | 30 (20–40) |

| Day 3 | 16 (0–30) | 25 (20–30) |

| Number of additional analgesics | ||

| Day 0 | 0.8 (0–1) | 1 (1–1) |

| Day 1 | 2 (0–4) | 2 (2–2) |

| Day 2 | 0.3 (0–2) | 0.5 (0–1) |

| Day 3 | 0 | 0.5 (0–1) |

VAS score: Visual analogue scale score.

Values are expressed as medians (range).

4. Discussion

In recent years, the number of articles reporting the usefulness of laparoscopic colorectal surgery using NOSE has been gradually increasing. Previous studies reported that laparoscopic colorectal surgery with NOSE required only small incisions, resulting in faster gastrointestinal recovery, less postoperative pain, shorter hospital stay, and good cosmetic outcomes [9,[13], [14], [15], [16]]. However, laparoscopic surgery using NOSE is technically complicated and difficult, and it requires an enterotomy within the peritoneal cavity, which can cause bacterial infection and cancer cell transplantation. According to a meta-analysis, NOSE has a longer surgery time than the conventional method, but there is less wound infection, and postoperative complications such as anastomotic leakage are similar to those of the conventional method [9]. In this report, although a bacterial culture test after intraperitoneal lavage was positive in 3 of 8 cases, high fever did not occur, and the increase in values indicating inflammation on blood testing was milder than in the conventional method. There were no postoperative complications. In addition, NOSE is comparable to the conventional method in terms of 5-year disease-free survival, the number of harvested lymph nodes, and securing an appropriate surgical margin [9,17,18]. Based on these findings, NOSE is considered feasible and oncologically safe. However, it is important to remember that NOSE is a procedure that deviates from the principle of cancer surgery in which the tumour should not be exposed, and cancer cell implantation may occur. In order to prevent local recurrence of cancer, it is important to adequately lavage the intestinal tract and the abdominal cavity, to use a specimen extraction bag or wound retractor. In addition, this technique has limitations when the tumor is large, so it is important to select the appropriate cases. There are two methods of NOSE: transanal specimen extraction (TASE) and transvaginal specimen extraction (TVSE). There are various types of intracorporeal anastomoses, such as side-to-side anastomosis using a linear stapler and double stapling technique using a circular stapler. It is important to select an appropriate specimen extraction route and anastomosis method for each case. In order to avoid increasing postoperative complications, the technique of intracorporeal anastomosis should be fully mastered before starting NOSE. NOSE has been reported to be comparable to conventional methods in both short-term and long-term outcomes, but long-term outcomes for advanced cancer require more careful judgment. This technique may provide both an attractive way to reduce abdominal incision-related morbidity and a bridge to pure natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) colon surgery.

5. Conclusion

Total laparoscopic colon cancer surgery with NOSE appears to be feasible, safe, and show promising efficacy for selected patients.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

None of the authors have anything to disclose.

Ethical approval

The Ethics Committee on Clinical Investigation of Osaka Medical College Hospital, which approved the protocol (No. 2017-161).

Consent

All patients were fully informed of the study design according to the Ethics Committee on Clinical Investigation of Osaka Medical College Hospital, which approved the protocol (No. 2017-161), and provided their written, informed consent to participate.

Author contribution

#Study conception design: Shinsuke Masubuchi, Junji Okuda, and Keitaro Tanaka

#Data acquisition: Shinsuke Masubuchi, and Masashi Yamamoto

#Data analysis and interpretation: Shinsuke Masubuchi, Junji Okuda, Yoshihiro Inoue, Keitaro Tanaka and Kazuhisa Uchiyama

#Drafting the article: Shinsuke Masubuchi, and Masashi Yamamoto

#Critical revision for intellectual content: Shinsuke Masubuchi, Junji Okuda, Yoshihiro Inoue, Keitaro Tanaka and Kazuhisa Uchiyama

#Final approval of the manuscript: Shinsuke Masubuchi, Junji Okuda, Masashi Yamamoto, Yoshihiro Inoue, Keitaro Tanaka and Kazuhisa Uchiyama

#Agree to be accountable for all aspects of work to ensure that questions regarding accuracy & integrity investigated & resolved: Shinsuke Masubuchi, Junji Okuda, Masashi Yamamoto, Yoshihiro Inoue, Keitaro Tanaka and Kazuhisa Uchiyama.

Registration of research studies

researchregistry6369 available at: https://www.researchregistry.com/browse-the-registry#home/.

Guarantor

Shinsuke Masubuchi, Junji Okuda, Masashi Yamamoto, Yoshihiro Inoue, Keitaro Tanaka and Kazuhisa Uchiyama.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Acknowledgements

None.

Contributor Information

Shinsuke Masubuchi, Email: sur124@osaka-med.ac.jp.

Junji Okuda, Email: sur017@osaka-med.ac.jp.

Masashi Yamamoto, Email: sur138@osaka-med.ac.jp.

Yoshihiro Inoue, Email: sur129@osaka-med.ac.jp.

Keitaro Tanaka, Email: sur036@osaka-med.ac.jp.

Kazuhisa Uchiyama, Email: uchi@osaka-med.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Romy S., Eisebring M.C., Bettschart V. Laparoscope use and surgical site infection in digestive surgery. Ann. Surg. 2008;247:627–632. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181638609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh R., Omiccioli A., Hegge S. Dose the extraction-site location in laparoscopic colorectal surgey have an impact on incisional hernia rates? Surg. Endosc. 2008;22:2596–2600. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9845-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winslow E.R., Fleshman J.W., Birnbaum E.H. Wound complications of laparoscopic vs. open colectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2002;16:1420–1425. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8837-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hisada M., Katsumata K., Ishizaki T. Complete laparoscopic resection of the rectum using natural orifice specimen extraction. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16707–16713. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i44.16707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costantino F.A., Diana M., Wall J. Prospective evaluation of peritoneal fluid contamination following transabdominal vs. transanal specimen extraction in laparoscopic left-sided colorectal resections. Surg. Endosc. 2012;26:1495–1500. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-2066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Awad Z.T., Griffin R. Laparoscopic right hemicolectomy: a comparison of natural orifice vs. transabdominal specimen extraction. Surg. Endosc. 2014;28:2871–2876. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xingmao Z., Haitao Z., Jianwei L. Totally laparoscopic resection with natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) has more advantages comparing with laparoscopic-assisted resection for selected patients with sigmoid colon or rectal cancer. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:1119–1124. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-1950-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung A.L., Cheung H.Y., Fok B.K. Prospective randomized trial of hybrid NOTES colectomy vs. conventional laparoscopic colectomy for left-sided colonic tumors. World J. Surg. 2013;37:2678–2682. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu R.J., Zhang C.D., Fan Y.C. Safety and oncological outcomes of laparoscopic NOSE surgery compared with conventional laparoscopic surgery for colorectal diseases: a meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2019;9:597. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishimura A., Kawahara M., Suda K. Totally laparoscopic sigmoid colectomy with transanal specimen extraction. Surg. Endosc. 2011;25:3459–3463. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Koshy K., Fowler A., Orgill D.P., For the SCARE Group The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agha R.A., Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Franchi T., Kerwan A., O’Neill N for the PROCESS Group The PROCESS 2020 guideline: updating consensus preferred reporting of case series in surgery (PROCESS) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;60 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flora E.D., Wilson T.G., Martin I.J. A review of natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) for intra-abdominal surgery: experimental models, techniques, and applicability to the clinical setting. Ann. Surg. 2008;247:583–602. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181656ce9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weibel S., Jokinen J., Pace N.L. Efficacy and safety of intravenous lidocaine for postoperative analgesia and recovery after surgery: a systematic review with trial sequential analysis. Br. J. Anaesth. 2016;116:770–783. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willingham F.F., Brugge W.R. Taking NOTES: transluminal flexible endoscopy and endoscopic surgery. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2007;23:550–555. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32828621b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolthuis A.M., Mueleman C., Tomassetti C. Laparoscopic sigmoid resection with transrectal specimen extraction: a novel technique for the treatment of bowel endmetriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2011;2:1348–1355. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parks J.S., Kang H., Kim H.J. Long-term outcomes after Natural Orifice Specimen Extraction vs. conventional laparoscopy-assisted surgery for rectal cancer: a matched case-control study. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2018;94:26–35. doi: 10.4174/astr.2018.94.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denost Q., Adam J.P., Pontallier A. Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision with coloanal anastomosis for rectal cancer. Ann. Surg. 2015;261:138–143. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]