Highlights

-

•

Hard palate cancer is a rare malignant tumor. Different histological types have been described in the hard palate which can affect its different structures.

-

•

A retrospective review of 4 patients who underwent Surgical resection by trans oral approach was performed for different histological types of malignant tumors of the hard palate.

-

•

Surgical resection is the treatment of choice for malignant tumors of the hard palate. A variety of surgical procedures that can be used via a trans oral approach.

-

•

Survival rate depends on several factors, including early diagnosis, histological characteristic and appropriate management.

Keywords: Malignant tumors, Hard palate, Surgery, Rehabilitation, Prognostic factors

Abstract

Introduction

Cancer of the hard palate is a fairly rare malignant tumor. Different histological types have been described in the hard palate, and that can affect its different structures.

Diagnosis is based on biopsy with histological examination and possibly on immunohistochemical markers to confirm the diagnosis and exclude other diagnostic hypotheses.

The aim of this study was to determine histopathologic, clinical and therapeutic characteristics of malignant tumors of the hard palate.

Patients and methods

A retrospective review of 4 patients who underwent Surgical resection by trans oral approach was performed for different histological types of malignant tumors of the hard palate. These included squamous cell carcinoma (case1 and case 2), mucosal melanoma (case 3), and adenocarcinoma (case 4).

Results

The T stage was analyzed for all cases. Two cases were classified as T2 stage with a tumor size between 2 and 4 cm and the two others, given the extension to the maxillary and nasal cavity were classified as T4a. Cervical lymph node metastasis was found in three patients.

Discussion

Surgical resection is the treatment of choice for malignant tumors of the hard palate. There is a variety of surgical procedures that can be used via a trans oral approach. Reconstruction of palatal defects with a prosthesis is sufficient, whereas larger defects will require a local, regional or even microvascular free tissue flap. The differences between these surgical techniques are presented, and indications are discussed.

Conclusion

The therapeutic management for malignant tumors of the hard palate is essentially surgical, with or without postoperative radiotherapy, discussed on a case-by-case basis. Survival rate depends on several factors, including early diagnosis, histological characteristic and appropriate management.

1. Introduction

Hard plate cancer (HPC) is an uncommon malignant tumor. Etiologic factors dominated by alcohol and tobacco consumption, are similar to those of other oral cavity cancers [1].

The anatomical and histological constitution of the hard palate, with firm attachment of the mucosa to the underlying periosteum and the abundance of minor salivary glands, make the hard palate a site of different histopathologic type of neoplasms [2]. HPC represents approximately 1–3.5% of oral cavity cancers and is most often a squamous cell carcinoma [3].

A variety of treatments have been used to treat hard palate cancer, including surgery, radiotherapy, chemoradiation and combinations of these modalities.

Surgery is the treatment of choice. It is usually performed via a transoral approach without the need to use facial incisions. The choice of the technique is based on location and size of the tumor [4]. In our work we present four cases of HPC treated by a transoral procedure.

Cervical lymph node metastases are associated with decreased survival rates. The deciding factors for clinician’s decisions on whether an elective neck dissection is necessary or not, are the presence of cervical lymph nodes, the primary site of cancer, tumor size and histological study results [5,6].

For HPC, primary reconstruction surgery has been developed allowing an improvement of the quality of life after surgery and avoiding the predisposition to hyper nasal speech, leakage of foods and liquids into the nasal cavity, difficulty swallowing, and improved masticatory function [7,8].

The aim of this study was to determine histopathologic, clinical and therapeutic characteristics of malignant tumors of the hard palate. In addition, we want to highlight the importance of primary prevention; education on risks of alcohol/tobacco use and oral hygiene. Secondary prevention; Early biopsy of any ulceration of the hard palate that does not regress with medical treatment. This would allow early diagnosis and minimal treatment with less morbidity and better survival chances.

2. Patients and methods

Here we present four clinical cases of hard palate tumors treated with surgery and radiation therapy in the otolaryngology – head and neck department of Casablanca university hospital. All surgeries were performed by a senior professor. Data was collected retrospectively. This work has been reported in line with the PROCESS 2018 criteria [30].

2.1. Case 1

A 53-year-old female, who was toothless and a former smoker, presented with an ulcerative painless lesion located at the mucosa of the hard palate. It gradually increased in size over the past year, with a slight discomfort when swallowing.

On physical examination a hard ulcerative lesion was noted in the middle part of the hard palate (Fig. 1). No adenopathy or cranial nerves deficit was observed.

Fig. 1.

Intraoral image showing reddish palatal ulceration.

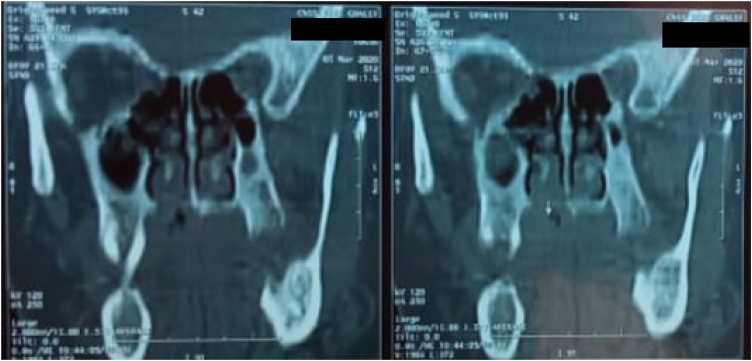

CT scan revealed a mass of the hard palate, right paramedian, measuring 3 × 2 × 2 cm, with bone erosion of the floor of the nasal cavity (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Ct scans showing a hard palate mass destroying adjacent bone structures with erosion of the floor of the nasal cavity.

The histological analysis of the biopsy showed a squamous cell carcinoma.

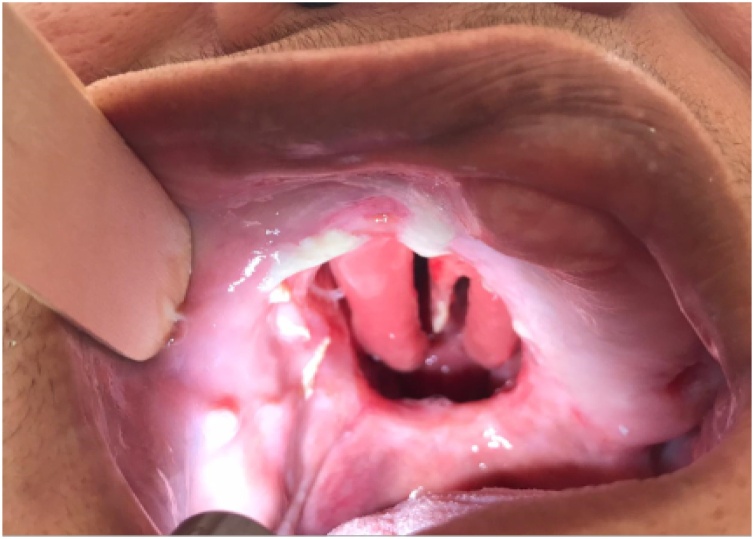

Treatment was based on an inferior maxillectomy (Fig. 3) without neck dissection. The defect was repaired with a dental prosthetic obturator (Fig. 4A and B). Treatment was completed with adjuvant radiotherapy. The patient is disease free on her nine months follow-up with no major swallowing dysfunction.

Fig. 3.

Intraoral image showing a defect after an inferior maxillectomy.

Fig. 4.

A; Postoperative image showing a rehabilitation with dental prosthetic allowing a good oro-nasal separation. B; Palatal obturator prosthesis.

2.2. Case 2

An 84-years-old man, heavy smoker, presented with a three months history of a painless mucosal lesion of the palate.

Intraoral examination found an ulcerative budding lesion of the right hemi palate. The tumor did not exceed the midline. The patient had poor oral hygiene. No lymphadenopathies were found.

CT scan demonstrated a large, hypodense and heterogeneous mass of the right hard palate, measuring 34 × 29.2 × 30.4 mm with bone erosion. Ib level lymphadenopathy was seen.

We did a biopsy of the palatal lesion and the histological study showed a well differentiated, keratinizing and infiltrating squamous cell carcinoma.

A partial lateral maxillectomy with at least a 1-cm margin was performed as well as bilateral selective neck dissection (levels I to III) and adjuvant radiation therapy.

The post-operative defect was managed with obturator prosthesis (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Restoration of cosmesis with dental prosthetic rehabilitation.

After 8 weeks, the patient unfortunately experienced a local recurrence with a rapidly progressing tumor then was lost to follow-up (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Recurrence of squamous cell carcinoma of the hard palate, 8 weeks after resection.

2.3. Case 3

A non-smoker 56-years-old woman, with no medical history, presented with a painless bluish macule of the palate which were progressing for 6 months.

The lesion was irregular, measuring approximately 3 cm, with no extension beyond the midline. The patient had poor oral hygiene.

Extraoral examination did not reveal any lymphadenopathy. The patient was in a good overall physical condition.

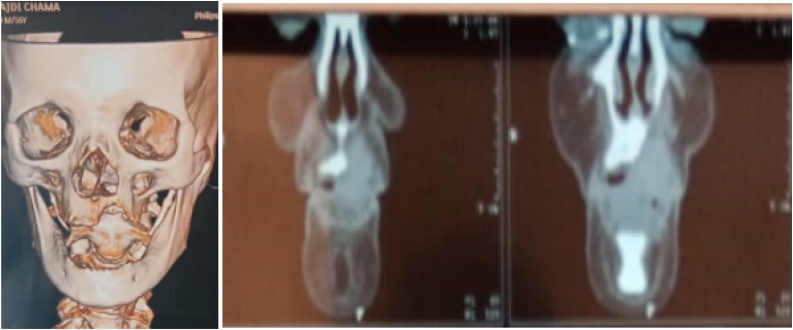

Computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a 30 × 20 mm homogeneous enhanced lesion invading the left maxillary sinus and destroying its bony walls without detectable lymph node invasion (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Ct scan images of a mucosal meloanoma of the hard palate invading bone.

A positron emission tomography (PET) scan showed the hypermetabolic lesion of the hard palate with a hypermetabolic left cervical lymphadenopathy without hypermetabolic focus identifiable elsewhere.

Histological and immunohistochemical studies of the biopsy showed a malignant tumor proliferation expressing diffusely Melan A, PS100 and HMB45, which was suggestive of melanoma.

A total left maxillectomy, level I to III selective neck dissection were performed as well as adjuvant radiation therapy. Postoperatively, the patient underwent prosthetic rehabilitation with good outcomes at her one-year follow-up.

2.4. Case 4

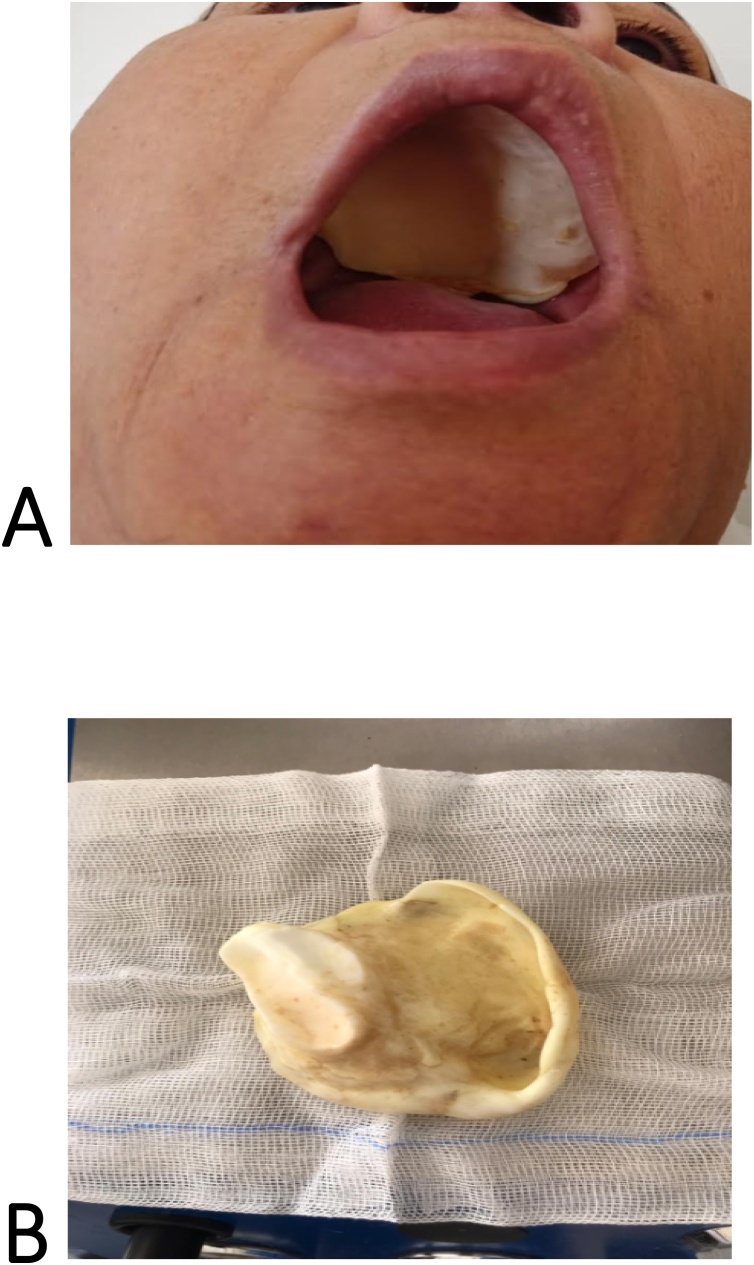

A 66-year-old woman with no relevant medical history, was referred to our Institution for a painless palatal mass that has slowly been growing over 18 months.

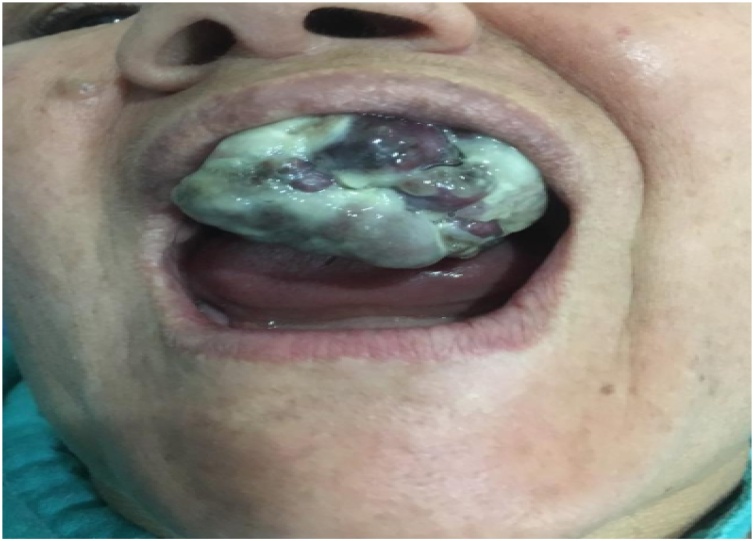

Clinical examination revealed a budding lesion, taking up the entire hard palate and extending to the hard/soft palate junction (Fig. 8). The oral hygiene was poor. There were hard and fixed right level I lymphadenopathies.

Fig. 8.

Oral view showing the palatal mass occupying the oral cavity.

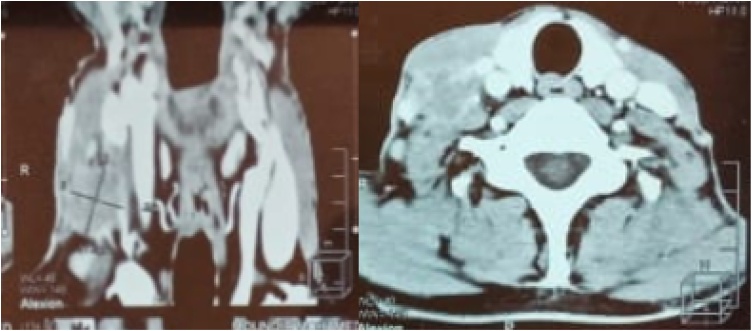

Face and neck CT scans showed a huge mass of 4 × 4 × 3 cm with significant bone destruction, cortical bone expansion and enlarged lymph nodes in the I and II levels (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

CT scans showing the enlarged lymph node in the submandibular region.

Histological examination of the biopsy showed a polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma, with the following positive immunohistochemical markers: Anticytokeratin, clone AE1/AE3.

On the basis of the immunohistochemical results, a diagnosis of polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma was established.

A total maxillectomy with large surgical margins was carried out along with a right-side level I to III neck dissection and post-operative radiotherapy. The patient has benefited from a prosthetic rehabilitation.

3. Discussion

The hard palate (also known as the ‘roof of the mouth’), forms a division between the nasal and oral cavities, the palatine process of the maxillary bone and the horizontal plate of the palatine bone constitute the skeleton of the hard palate. It is 1 of 7 subsites of the oral cavity [1].

Oral cancer is the sixth most common malignancy worldwide. The most common tumors of the oral cavity involve the oral tongue and the floor of the mouth however It is estimated that 1–3.5% of oral cancers are located at the hard palate [3,9].

Several risk factors linked to cancer of the hard palate have been described in epidemiological studies around the world. Major risk factors are cigarette smoking and alcohol misuse. Although poor oral hygiene and poor dentition have been implicated in a few epidemiological studies [10,11].

In our 4 cases a poor buccal hygiene is present in all the patients. Other risk factors were described, including diet and nutrition, socio-economic status, indoor air pollution and ethnicity and race [12].

Different histological types have been described in the hard palate, and that can affect its different structures. The most common malignant salivary gland tumor (MSGT) is adenoid cystic carcinoma, followed by mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma. While most malignant epithelial tumors are squamous cell carcinomas. Several studies have reported that adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) and mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) are the most common malignant MSGTs located at the hard palate [13].

Although minor salivary gland malignant tumors occur fairly frequently in this area, squamous cell carcinoma remains also most common malignancy affecting the hard palate according to other studies [14].

Moreover, primary mucosal melanomas are extremely rare and aggressive malignancies involving several anatomic districts, the incidence of hard palate melanoma represents about 1.4% of all melanomas [15].

All of our patients have benefited from an examination of the oral cavity using a bright light, tongue depressors, and suction. It is paramount in determining the extent and characteristics of the mass; location, size of mass, and search for loose dentition. The usual clinical presentation in our case included bluish macules, ulcerative or budding lesions.

The endoscopic examination allows to take biopsies that are systematic, which alone can confirm the tumor and also look for synchronous cancer present in nearly 10% of cases [16,17].

CT and MR imaging are the most frequently used imaging modalities. CT is useful for evaluating adjacent bone erosion or destruction. Therefore, MR imaging can be used to evaluate the differential diagnosis and extent of the tumor in soft tissue and deep facial spaces. CT and MR images thus can characterize staging of malignant palatal tumors [18].

In our patient we noted T2 staged in 2 cases with a tumor size between 2 and 4 cm and 2 cases classified as T4a extending to the maxillary sinus for one and to the nasal cavity for the other.

Adenoid cystic carcinoma can appear as a malignant lesion have a proclivity to show destructive growth and invasion of the underlying bone. On T2-weighted images, high-grade tumors show hypo intensity whereas low-grade tumors show hyperintensity.

The imagery features of adenocarcinoma are non-specific. It can potentially cause bone resorption, medullary infiltration, and invasion of nearby nerves and blood vessels. Advanced tumors often extend to the maxillary sinus, nasal cavity, and oropharynx and are accompanied with extensive hard palate bone destruction [19].

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the hard palate extend often superiorly to involve the nasal cavity and maxillary sinuses best evaluated with CT scan. However, perineural spread of palatine lesions is best evaluated with MR imaging [21].

Adenocarcinoma of the hard palate may be misdiagnosed because of its similarities to other histological types, leading to inappropriate treatment. For this reason, immunohistochemical markers can be used to reach the diagnosis. Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma is composed by only one cell type that expresses cytokeratins 7, sometimes 14, and also vimentin, but not muscle-specific actin. In our case, the markers that have been used are cytokeratin confirming the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma [20].

This allows to differentiate it from cystic adenoid carcinoma, whose immunohistochemical expression is characterized in the luminal cells by the expression of cytokeratins 7, 8, 14 and 19 while all remaining cells are of myoepithelial origin, which are negative for cytokeratins (except for cytokeratin 14 sometimes) and positive for vimentin and muscle-specific actin [20].

In our study cervical lymph node metastases were found in three patients, of whom one has Level I Iymph node metastasis with polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma and two had Level III lymph node metastasis with squamous cell carcinoma and mucosal melanoma as histological types.

The surgical treatment of malignant tumors of the hard palate must completely remove, with at least 1 cm margin, all the involved tissues with en bloc resection of the mucosa and the underlying bone of the hard palate [22,23].

Surgical resection is performed trans-orally in almost all cases. The external approach is necessary for very advanced malignant neoplasms and when extending into the parapharyngeal space, pterygo-palatal fossa or masticatory space [2].

Approaches to the surgical management of cancer limited to the hard palate and alveolar ridge include: Partial lateral maxillectomy which is tailored for small tumors of the lateral maxillary alveolar ridge and hard palate, that involve the maxillary sinus and nasal cavity. Inferior maxillectomy for tumors of the hard palate limited to the floor of the maxillary sinus that does not involve the nasal cavity and complete maxillectomy for advanced stages extended into the maxillary sinus or nasal cavity and have significant bilateral extension [4,23].

Therapeutic neck dissection should be reserved for clinically and radiographically positive cervical lymph nodes. When unclear margins or perineural or perivascular invasion is present, with cervical lymph node involvement.

Neck dissection (levels I to III) is ipsilateral for tumors that do not involve the midline. Bilateral neck dissection should be performed for tumors involving the midline [6,23].

The indication also depends on the histological type, squamous cell carcinoma of the hard palate should be treated aggressively, and neck dissection should be considered because of the high rate of lymph node metastasis [24].

Patients treated for hard palate cancer require a means of restoring the oral-nasal separation lost by removal of the palate and alveolar bone in order to improve patient’s quality of life.

Four major means of rehabilitation have been described in the literature. It includes: dental prosthetic when the cancer does not involve more than half the hard palate, mucoperiosteal local flap of palatal island flap, regional flaps by temporalis flap allows immediate reconstruction and can be used to correct unilateral and total defects. Otherwise, microvascular free tissue transfer is an option for larger defects [7,25].

Prosthetic rehabilitation for palatal defects offers significant advantages. The prosthesis is well tolerated during radiation therapy and permits visualization of disease recurrence [26]. All our patients have benefited from a prosthetic rehabilitation.

Postoperative radiation therapy is recommended in cases in which there is a large lesion; high-grade T4 and T3, and microscopic criteria; large blood vessel or nerve invasion; or close margins and cervical metastasis [27,28]. Our use of radiation therapy was similar in patients with high-grade T4 and T3 or in which there was significant cervical metastases.

Tumor size > T2, the presence of distant metastases and the positive margins of resection, are factors associated with poor prognosis. The exact site of the tumor does not influence the survival outcome [20]. Bone invasion does not necessarily have much impact on the survival rate [1,5].

Regarding mucosal melanoma, the overall 5-year survival is 15%. A better survival rate was reported for patients diagnosed with a localized or regional disease in comparison to patients with distant disease [28].

Prognostic factors of hard palate carcinoma are mainly the stage, perineural invasion and resection margins. While there is no convincing evidence for the prognostic significance of perineural invasion, it seems that resection margin involvement may lead to a higher rate of recurrence. Even in case of recurrence, the prognosis is excellent in terms of survival. the 5- and 10-year disease-specific survival rates are ranging between 93 and 100% [29].

Given the relative rarity of hard palate tumors and the diverse histological types, we need larger prospective multicentric studies to further detail risk and prognosis factors, and figure out a tailored therapeutic regimen for each patient.

4. Conclusion

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common malignant tumor of the hard palate. The clinical diagnosis is based on a search of risk factors, a complete ENT examination and endoscopic examination. CT scan allows a better analysis of bone invasion, while MRI retains its place in the evaluation of local and regional tumor extension. Surgical biopsy with immunohistochemical study confirms the diagnosis and exclude another diagnostic hypothesis.

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice. All our cases have been treated through an intraoral approach with elective neck dissection when pathological lymph nodes are found. Radiotherapy is considered in case of advanced stage disease, buccal extension, positive margins, perineural spread, or multiple lymph node metastases.

The reconstruction of defect after surgical resection is advisable. It restores almost immediately the phonetic and masticatory functions and it allows direct visualization of the primary site for recurrence detection as in case 2.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not needed for this article by our institution because it is a report of four cases with no research or experiment involved.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case reports and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Registration of research studies

-

1.

Name of the registry: Research Registry

-

2.

Unique identifying number or registration ID: reviewregistry1045

-

3.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): https://www.researchregistry.com/register-now#user-systematicreviewmeta-analysesregistry/addregisterasystematicreviewmeta-analysi/register-a-systematic-reviewmeta-analysis-payment/5fc7e13365c3e5001cf292e4/

Guarantor

Y. Hammouda.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Y. Hammouda: Investigation, Resources, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. S. Halily: Investigation, Resources. Y. Oukessou: Writing - review & editing. S. Rouadi: Validation, Supervision. R. Abada: Validation, Supervision. M. Roubal: Validation, Supervision. M. Mahtar: Validation, Supervision.

References

- 1.Utku Aydil MD, Yusuf Kızıl MD, Faruk Kadri Bakkal MD, Ahmet Köybaşıoğlu MD et Sabri Uslu MD Neoplasms of the Hard Palate. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Aydil U., Kızıl Y., Bakkal F.K., Köybaşıoğlu A., Uslu S. Neoplasms of the hard palate. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014;72(3):619–626. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganly I., Ibrahimpasic T., Patel S.G. Tumors of the oral cavity. In: Montgomery P.Q., Rhys Evans P.H., Gullane P.J., editors. Principles and Practice of Head and Neck Surgery and Oncology. ed 2. Informa Helthcare; London, UK: 2009. pp. 160–191. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simental Alfred A., Jr., Myers Eugene N. Cancer of the hard palate and maxillary alveolar ridge: technique and applications. Oper. Tech. Head. Neck Surg. 2005;16:28–35. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hakim Samer George, Steller Daniel, Sieg Peter, Rades Dirk. Ubai Alsharif. Clinical course and survival in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the maxillary alveolus and hard palate: Results from a single-center prospective cohort. J. Cranio-maxillofacial Surg. 2020;48(January (1)):111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2019.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crean S.J., Bryant C., Bennett J. Four cases of polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1996;25:40. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(96)80010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.M.L Urken. Advances in head and neck reconstruction. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1473–1476. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200309000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beumer J., Curtis T.A., Marunick M.T. Ishiyaku EuroAmerica, Inc.; St. Louis: 1996. Maxillofacial rehabilitation: prosthodontic and surgical considerations. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lale Kostakoglu PET/CT Imaging in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck Problem Solving in Neuroradiology, Chapter 4, 126-207.

- 10.Zheng T.Z., Boyle P., Hu Dentition, oral hygiene and risk of oral cancer: a case-control study in Beijing, Peoples Republic of China. Cancer Causes Control. 1990;1:235–241. doi: 10.1007/BF00117475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marshall J.R., Graham S., Haughey B.P. Smoking, alcohol, dentition and diet in the epidemiology of oral cancer. Eur. J. Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1992;28B:9–15. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(92)90005-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warnakulasuriya S. Causes of oral cancer – an appraisal of controversies. Br. Dent. J. 2009;207:471–475. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian Z., Li L., Wang L. Salivary gland neoplasms in oral and maxillofacial regions: a 23-year retrospective study of 6982 cases in an eastern Chinese population. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010;39:235. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruce M. Wenig MD Neoplasms of the Oral Cavity Atlas of Head and Neck Pathology, Chapter 6, 273-383.e15.

- 15.Oranges Carlo M., Sisti Giovanni, Nasioudis Dimitrios, Tremp Mathias, summa Pietro G.Di, Kalbermatten Daniel F., Largo RenéD., Schaefer Dirk J. Hard palate melanoma: a population-based analysis of epidemiology and survival outcomes. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:5811–5817. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hans Stéphane, Bras Daniel, Réfle Xions N.u. 2010. En Médecine Oncologique N°37 - Tome 7 - Février. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhooge I.J., De Vos M., Van Cauwenberge P.B. Multiple primary malignant tumors in patients with head and neck cancer : results of a prospective study and future perspectives. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:250–256. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199802000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gandhi D., Gujar S., Mukherji S.K. Magnetic resonance imaging of perineural spread of head and neck malignancies. Top. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2004;15(2):79–85. doi: 10.1097/01.rmr.0000130601.57619.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiroki Katoa,∗, Masayuki Kanematsua,b, Hiroki Makitac, Keizo Katoc, Daijiro Hatakeyamac, Toshiyuki Shibatac, Keisuke Mizutad, Mitsuhiro Aokid, CT and MR imaging findings of palatal tumors. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Ferrazzo Kivia Linhares, Alves Sergio Melo, Santos Elisa, Martins Marilia Trierveiler, Machado de Sousa et Suzana. galectin-3 immunoprofile in adenoid cystic carcinoma and polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma of salivary glands. Oral Oncol. 2007;43(6):580–585. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ginsberg L.E., DeMonte F. Imaging of perineural tumor spread from palatal carcinoma. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1998;19(8):1417–1422. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.L.A. Mazzarella, A.H. Friedlander, Intraoral hemimaxillectomy for the treatment of cancer of the palate. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol., 54(2), 157–160. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Peter S. Vosler et Eugene N. Myers. Transoral Inferior Maxillectomy, Operative Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, 32, 227-236.e1.

- 24.Li Quan, Di Wu, Liu Wei-Wei, Li Hao, Liao Wei-Guo. Survival impact of cervical metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma of hard palate. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2013;116(July (1)):23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Persky M.P. Carcinoma of the palate. News from SPOHNC. 2005;14:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson J.T., Aramany M.A., Myers E.N. Palatal neoplasms: reconstructive considerations. Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am. 1983;16:441–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weisberger E., Luna M.A., Guillamondegui O.M. Minor salivary gland tumors of the palate: clinical and pathologic correlates of outcome. Laryngoscope. 1995;105(November) doi: 10.1288/00005537-199511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oranges C.M., Sisti G., Nasioudis D., Tremp M., Di Summa P.G., Kalbermatten D.F., Schaefer D.J. Hard palate melanoma: a population-based analysis of epidemiology and survival outcomes. Anticancer Res. 2018;38(10):5811–5817. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elhakim M.T., Breinholt H., Godballe C., Andersen L.J., Primdahl H., Kristensen C.A., Bjørndal K. Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma: a Danish national study. Oral Oncol. 2016;55:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A., Orgill D.P., For the PROCESS Group The PROCESS 2018 statement: updating consensus preferred reporting of CasE series in surgery (PROCESS) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;(60):279–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]