Key Points

Question

Does frailty differ between women and men with decompensated cirrhosis awaiting liver transplant, and is frailty associated with the gender gap in mortality in this population?

Findings

In this multicenter cohort study of 1405 patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplant, women displayed worse frailty scores despite similar liver disease severity. Frailty attenuated the known gender gap in wait list mortality, mediating 13% of the gap.

Meaning

These findings identified frailty as a novel factor associated with the gap in wait list mortality between women and men with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplant.

This multicenter cohort study assesses whether frailty is associated with the gap in mortality between women and men among patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplant.

Abstract

Importance

Female liver transplant candidates experience higher rates of wait list mortality than male candidates. Frailty is a critical determinant of mortality in patients with cirrhosis, but how frailty differs between women and men is unknown.

Objective

To determine whether frailty is associated with the gap between women and men in mortality among patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective cohort study enrolled 1405 adults with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplant without hepatocellular carcinoma seen during 3436 ambulatory clinic visits at 9 US liver transplant centers. Data were collected from January 1, 2012, to October 1, 2019, and analyzed from August 30, 2019, to October 30, 2020.

Exposures

At outpatient evaluation, the Liver Frailty Index (LFI) score was calculated (grip strength, chair stands, and balance).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The risk of wait list mortality was quantified using Cox proportional hazards regression by frailty. Mediation analysis was used to quantify the contribution of frailty to the gap in wait list mortality between women and men.

Results

Of 1405 participants, 578 (41%) were women and 827 (59%) were men (median age, 58 [interquartile range (IQR), 50-63] years). Women and men had similar median scores on the laboratory-based Model for End-stage Liver Disease incorporating sodium levels (MELDNa) (women, 18 [IQR, 14-23]; men, 18 [IQR, 15-22]), but baseline LFI was higher in women (mean [SD], 4.12 [0.85] vs 4.00 [0.82]; P = .005). Women displayed worse balance of less than 30 seconds (145 [25%] vs 149 [18%]; P = .003), worse sex-adjusted grip (mean [SD], −0.31 [1.08] vs −0.16 [1.08] kg; P = .01), and fewer chair stands per second (median, 0.35 [IQR, 0.23-0.46] vs 0.37 [IQR, 0.25-0.49]; P = .04). In unadjusted mixed-effects models, LFI was 0.15 (95% CI, 0.06-0.23) units higher in women than men (P = .001). After adjustment for other variables associated with frailty, LFI was 0.16 (95% CI, 0.08-0.23) units higher in women than men (P < .001). In unadjusted regression, women experienced a 34% (95% CI, 3%-74%) increased risk of wait list mortality than men (P = .03). Sequential covariable adjustment did not alter the association between sex and wait list mortality; however, adjustment for LFI attenuated the mortality gap between women and men. In mediation analysis, an estimated 13.0% (IQR, 0.5%-132.0%) of the gender gap in wait list mortality was mediated by frailty.

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings demonstrate that women with cirrhosis display worse frailty scores than men despite similar MELDNa scores. The higher risk of wait list mortality that women experienced appeared to be explained in part by frailty.

Introduction

Liver transplant is a well-established therapy for patients with end-stage liver disease. However, despite efforts to allocate deceased donor livers using objective metrics (eg, the laboratory-based Model for End-stage Liver Disease incorporating sodium level [MELDNa]), liver transplant is disproportionately available to men compared with women. Specifically, women awaiting liver transplant in the US are 17% to 30% less likely than men to receive this life-saving therapy, leading to a 30% increased odds of wait list mortality in women relative to men.1,2,3,4,5

The reason for the gap between women and men in wait list outcomes is not fully known but is likely multifactorial.6 Hypotheses have included underestimation of renal dysfunction in women by the MELDNa score4 and decreased access to size-appropriate livers due to women’s small body size,1,7 but neither of these hypotheses is fully explanatory. Underlying both hypotheses is the biological sex difference in muscle-related factors that results in lower production of creatinine and overall body size. However, the lack of objective metrics to measure these muscle-related sex differences in individuals with cirrhosis has hindered the community’s ability to fully explore the factors underlying these hypotheses.

Frailty, a geriatric construct commonly defined as a distinct biological syndrome of decreased physiologic reserve and increased vulnerability to health stressors,8 has recently been recognized as a critical factor associated with outcomes in patients with cirrhosis.9 Given cirrhosis-related protein synthetic dysfunction and ammonia-related myotoxicity, reduced muscle mass and muscle function are thought to play a dominant role in the frail phenotype in patients with cirrhosis7 and therefore might differ in women and men. In this study, we aimed to study differences in frailty between women and men with cirrhosis and, if found, evaluate the contribution of these differences to the gender gap in wait list mortality.

Methods

Patients

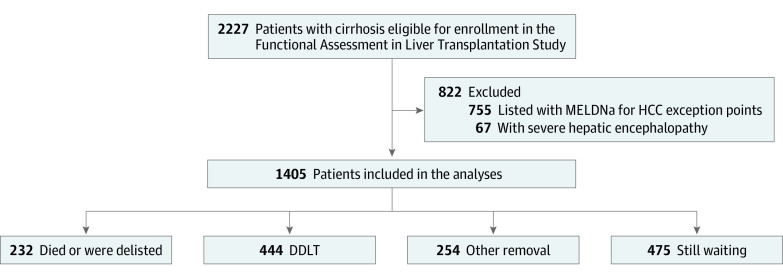

For this cohort study, we prospectively enrolled ambulatory patients with cirrhosis who were listed (or were eligible for listing) for liver transplant at the 9 US centers participating in the Functional Assessment in Liver Transplantation (FrAILT) cohort study: University of California, San Francisco (n = 895); Johns Hopkins Medical Institute, Baltimore, Maryland (n = 157); Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, Texas (n = 89); Columbia University, New York, New York (n = 88); Duke University, Durham, North Carolina (n = 48); University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (n = 42); Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, California (n = 35); Northwestern Medicine, Chicago, Illinois (n = 27); and University of Arkansas, Little Rock (n = 24). At the University of California, San Francisco, eligible patients were approached consecutively; at other sites, patients were approached based on the availability of clinical research coordinator support, not on patient characteristics. Patients were excluded if they had severe hepatic encephalopathy defined by a Numbers Connection Test score of greater than 120 seconds at initial screening given concern regarding the ability to provide informed consent (n = 67). Excluded were patients who were listed with MELDNa exception points for HCC (n = 755) (Figure 1). Each site’s institutional review board approved this study, and all patients provided written informed consent. We adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Figure 1. Flowchart of Functional Assessment in Liver Transplantation Study Participant Enrollment.

DDLT indicates deceased donor liver transplant; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MELDNa, laboratory-based Model for End-stage Liver Disease incorporating sodium level.

Study Procedures

Data collection started on January 1, 2012. Eligible patients were approached during their clinic visit; signed informed consent was obtained by trained study personnel before administration of study procedures. At enrollment and every clinic visit, trained study personnel administered 3 tests—grip strength,8 timed chair stands,10 and balance testing10—which were input into the online calculator (https://liverfrailtyindex.ucsf.edu). A higher index indicated that the patient had greater frailty. Interrater reliability has previously been assessed with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.93.11 Given that grip strength normative values are lower in women than in men,9 grip strength is adjusted in the Liver Frailty Index (LFI) equation using sex-specific z scores so that the index value can be compared equally between women and men.

Demographic and laboratory data were collected from the electronic health record according to a data collection protocol that was standardized across sites. Presence of ascites was ascertained from the hepatologists’ physical examination results or the management plan associated with the clinic visit on the same day as the frailty assessment. Ascites was categorized as present if documented on examination and/or the patient was undergoing large-volume paracenteses. Hepatic encephalopathy was categorized as present if the patient took at least 60 seconds to complete the Numbers Connection Test A.12 Wait list mortality was ascertained from the electronic health record until October 1, 2019.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from August 30, 2019, to October 30, 2020. Baseline demographics were presented as mean (SD), median (interquartile range [IQR]), or number (percentage) as appropriate. Effect estimates for the differences between women and men were provided as odds ratios with 95% CIs. The primary outcome was wait list mortality, defined as death or delisting for being too sick for liver transplant. Follow-up times for those who did not achieve a terminal wait list event were censored no later than October 1, 2019.

We used multilevel mixed-effects linear regression to quantify differences between women and men in the LFI; the estimated regression coefficient for sex reflected the mean difference in frailty between women and men. This approach allowed us to use multiple measurements per participant when longitudinal data were available, as previously used by the FrAILT Study group.13 To account for confounding by characteristics known to be associated with frailty, we adjusted the model for age, MELDNa score, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy (selected a priori). To allow for random intercepts and slopes, participant and follow-up time were modeled as random effects. To confirm differences between women and men, 3 sensitivity analyses were performed: (1) structured with 2 levels (participant and visit) to account for participant-level correlation, (2) structured with 3 levels to additionally account for center-level correlation, and (3) structured with MELDNa score and ascites modeled as time-varying covariates. All 3 of these models yielded similar results; we reported the output from model 1 in the results.

To evaluate the association of sex with risk of wait list mortality, we estimated the cumulative incidence of wait list mortality within 12 months by sex. To evaluate the biological implications of sex and frailty on wait list mortality, we modeled the hazard function, described as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs for each variable, with Cox proportional hazards regression to estimate wait list mortality risk. Participants who underwent living donor liver transplant or were removed for reasons other than being too sick (ie, social factors) were censored on the day of their transplant or removal from the waiting list. For the multivariable regression, all variables associated with wait list mortality with a P value of less than .10 in univariable analysis were evaluated for inclusion in the final multivariable model and eliminated using backward regression (using a threshold 2-sided P < .05). Sex was retained in the final model as the primary variable of interest. The interaction between sex and baseline frailty was assessed to determine whether the association of frailty with wait list mortality was different for women and men. To determine whether frailty accounted for the association of sex with wait list mortality risk, we compared multivariable models with and without the LFI using the Akaike information criterion and sex regression coefficients using bootstrap methods (100 replications). To account for center-level differences, we allowed the baseline hazard functions to differ between centers. Sensitivity analyses evaluating these associations with and without this center adjustment did not change the qualitative interpretation of our results. Causal mediation analysis was used to quantify the contribution of frailty to the sex disparity that was based on a framework of counterfactuals and causal methods14 using an extension of the Baron and Kenny procedure (PARAMED module).15 Two models were estimated: (1) a linear regression model of frailty conditional on sex and (2) a logistic regression model of wait list mortality conditional on sex and the mediator frailty; both models were adjusted for the Cox proportional hazards regression covariates (baseline MELDNa score, age, and albumin level) and wait list time.

To evaluate the same association in the real-world context of known differing rates of liver transplant between women and men,3 we conducted a sensitivity analysis using Fine and Gray16 competing risk regressions to estimate mortality risk (using subhazard ratios) with deceased donor liver transplant as the competing risk. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and STATA, version 15.0 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

Data were analyzed from 1405 patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplant; 578 (41%) were women and 827 (59%) were men. The median age was 58 (IQR, 50-63) years. Median follow-up time was 10.6 (IQR, 4.3-20.1) months for women and 10.2 (IQR, 4.5-22.4) months for men (P = .83). During their time in the study, women and men each had a median of 2 visits (IQR, 1-3; P = .45).

Characteristics of the Study Cohort

Patient characteristics are given in Table 1. Women were similar to men by age and race but had a lower body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by square of height in meters; median, 28 [IQR, 24-32] vs 28 [IQR, 25-33]). Disease etiology differed significantly by sex (women, chronic hepatitis C virus (127 [22%] vs men, 223 [27%]), alcohol (110 [19%] vs 273 [33%]), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (133 [23%] vs 132 [16%]), autoimmune/cholestatic disease (133 [23%] vs 74 [9%]), and other (75 [13%] vs 108 [13%]). Rates of hypertension (202 [35%] vs 347 [42%]) and coronary artery disease (23 [4%] vs 66 [8%]) were lower in women than in men, but rates of diabetes (162 [28%] vs 256 [31%]) were similar. The median MELDNa scores were similar for women (18 [IQR, 14-23]) and men (18 [IQR, 15-22]). Mean serum albumin levels (3.1 [0.7] and 3.2 [0.7] g/dL) and the proportions undergoing dialysis (23 [4%] and 41 [5%]), with ascites (208 [36%] and 323 [39%]), or with hepatic encephalopathy (116 [20%] and 165 [20%]) were also similar for women and men, respectively.

Table 1. Characteristics of the 1405 Patients With Cirrhosis Included in This Study .

| Characteristica | All patients (N = 1405) | Categorized by sex | Effect estimate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (n = 578) | Men (n = 827) | |||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 58 (50 to 63) | 58 (50 to 63) | 57 (49 to 63) | 0.3 (−0.6 to 1.3) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 927 (66) | 363 (63) | 562 (68) | 0.81 (0.65 to 1.01) |

| Black | 84 (6) | 40 (7) | 41 (5) | 1.54 (0.98 to 2.44) |

| Hispanic | 295 (21) | 133 (23) | 157 (19) | 1.23 (0.95 to 1.60) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 70 (5) | 29 (5) | 50 (6) | 0.88 (0.54 to 1.41) |

| Other | 28 (2) | 12 (2) | 17 (2) | 0.80 (0.35 to 1.83) |

| Height, mean (SD), cm | 171 (11) | 162 (7) | 177 (8) | −15 (−16 to −14) |

| Body mass index, median (IQR)a | 28 (25 to 33) | 28 (24 to 32) | 28 (25 to 33) | −0.9 (−1.5 to −0.3) |

| Etiology of liver disease, No. (%) | ||||

| Chronic hepatitis C virus | 351 (25) | 127 (22) | 223 (27) | 0.76 (0.60 to 0.98) |

| Alcohol | 379 (27) | 110 (19) | 273 (33) | 0.46 (0.36 to 0.60) |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | 267 (19) | 133 (23) | 132 (16) | 1.59 (1.21 to 2.08) |

| Autoimmune/cholestatic disease | 211 (15) | 133 (23) | 74 (9) | 2.98 (2.20 to 4.04) |

| Other | 197 (14) | 75 (13) | 108 (13) | 0.87 (0.64 to 1.19) |

| Hypertension, No. (%) | 548 (39) | 202 (35) | 347 (42) | 0.75 (0.60 to 0.94) |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 422 (30) | 162 (28) | 256 (31) | 0.87 (0.69 to 1.10) |

| Coronary artery disease, No. (%) | 84 (6) | 23 (4) | 66 (8) | 0.46 (0.28 to 0.75) |

| MELDNa score, median (IQR) | 18 (14 to 23) | 18 (14 to 23) | 18 (15 to 22) | 0.0 (−0.6 to 0.7) |

| Total bilirubin level, mg/dL | 2.5 (1.5 to 4.1) | 2.6 (1.6 to 4.3) | 2.3 (1.4 to 3.9) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.5) |

| Creatinine level, mg/dLb | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | −0.1 (−0.2 to −0.1) |

| Albumin level, g/dL | 3.1 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.7) | 3.2 (0.7) | −0.1 (−0.1 to 0.01) |

| Dialysis, No. (%) | 70 (5) | 23 (4) | 41 (5) | 0.87 (0.52 to 1.44) |

| Ascites, No. (%) | 534 (38) | 208 (36) | 323 (39) | 0.86 (0.69 to 1.07) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy, No. (%) | 281 (20) | 116 (20) | 165 (20) | 1.04 (0.80 to 1.36) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; MELDNa, laboratory-based Model for End-stage Liver Disease incorporating sodium level.

SI conversion factors: To convert albumin to g/L, multiply by 10; bilirubin to μmol/L, multiply by 17.104; and creatinine to μmol/L, multiply by 88.4.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by square of height in meters.

Includes those who were not undergoing dialysis.

Rates of Frailty

Table 2 displays frailty measurements at baseline assessment. At baseline, LFI was numerically and statistically significantly higher in women than in men (mean [SD], 4.12 [0.85] vs 4.00 [0.82]; P = .003), indicating a greater degree of frailty. Women displayed worse grip strength (median, 19.7 [95% CI, 15.7-24.3] vs 32.3 [95% CI, 26.0-39.0] kg) (including sex-adjusted grip strength [mean (SD), −0.31 (1.08) vs −0.16 (1.08) kg]; P = .01), a higher proportion with balance of less than 30 seconds (145 [25%] vs 149 [18%]; P = .003), and a lower number of chair stands per second (median, 0.35 [IQR, 0.23-0.46] vs 0.37 [IQR, 0.25-0.49]; P = .04).

Table 2. Baseline Frailty Assessments by Sex.

| Frailty metric | All patients (N = 1405) | Categorized by sex | Effect estimate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (n = 578) | Men (n = 827) | |||

| LFI, mean (SD) | 4.05 (0.84) | 4.12 (0.85) | 4.00 (0.82) | 0.12 (0.03 to 0.20) |

| Individual components | ||||

| Grip strength, median (IQR), kg | 26.3 (19.3 to 34.3) | 19.7 (15.7 to 24.3) | 32.3 (26.0 to 39.0) | −12.6 (−13.4 to −11.7) |

| Sex-adjusted grip strength, mean (SD), kg | −0.22 (1.08) | −0.31 (1.08) | −0.16 (1.08) | −0.15 (−0.26 to −0.03) |

| Balance <30 s, No. (%) | 295 (21) | 145 (25) | 149 (18) | 1.48 (1.15 to 1.92) |

| Chair stands per second, median (IQR) | 0.36 (0.24 to 0.48) | 0.35 (0.23 to 0.46) | 0.37 (0.25 to 0.49) | −0.02 (−0.04 to 0.00) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; LFI, Liver Frailty Index.

We then used multilevel mixed-effects linear regression to leverage the data from the multiple, longitudinal frailty assessments (n = 3436) available from our cohort. In unadjusted, multilevel mixed-effects linear regression, the LFI was 0.15 (95% CI, 0.06-0.23) units higher in women than in men (P = .001). After adjusting for other variables found to be associated with frailty (age, MELDNa score, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy), we observed that the sex differences in LFI persisted at 0.16 (95% CI, 0.08-0.23) units higher in women than in men; P < .001).

Sex, Frailty, and Wait List Mortality

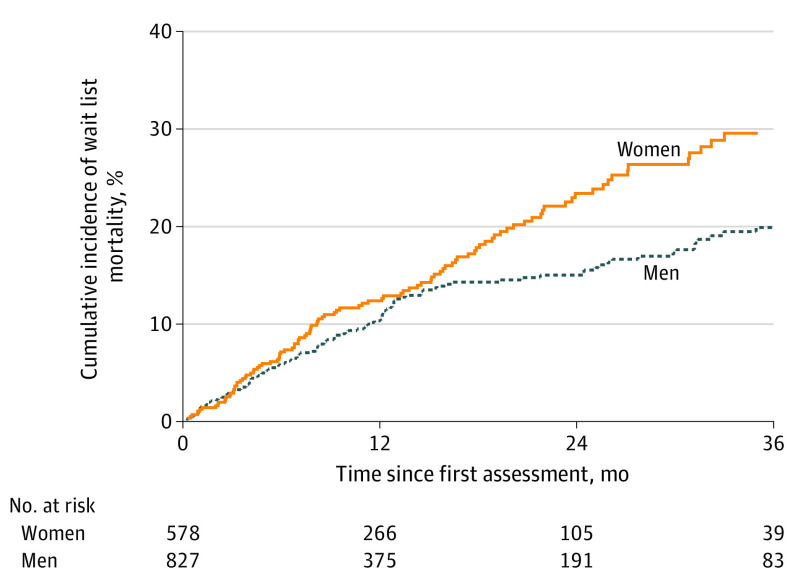

By the end of follow-up, 110 women (19%) and 122 men (15%) died or were removed from the wait list for being too sick for transplant (P = .03), and 160 women (28%) and 284 men (34%) underwent deceased donor liver transplant (P = .008). The cumulative incidence of wait list mortality for women was 2.7% at 3 months, 6.9% at 6 months, 12.1% at 12 months, and 22.9% at 24 months; for men, 2.7% at 3 months, 5.8% at 6 months, 10.2% at 12 months, and 14.8% at 24 months (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Cumulative Incidence of Wait List Mortality by Sex.

In univariable Cox proportional hazards regression, the HR of wait list mortality for women vs men was 1.34 (95% CI, 1.03-1.74) and for a 1-SD decrease in the LFI was 2.00 (95% CI, 1.74-2.29) (Table 3). After adjustment for the variables that were significantly associated with wait list mortality in multivariable analysis except for the LFI, the HR of wait list mortality for women vs men remained similar at 1.30 (95% CI, 1.00-1.68; P = .05); the model’s Akaike information criterion was 2462. After adjustment for the LFI, the HR of wait list mortality for women decreased to 1.20 (95% CI, 0.92-1.57; P = .17) with reduction in the model’s Akaike information criterion to 2408, demonstrating improvement in model fit. There was no significant interaction between sex and the LFI (P = .32), suggesting the association of frailty with mortality was similar by sex. When stratified by sex, the association of LFI (per 1-SD worsening) with mortality among women was an HR of 1.54 (95% CI, 1.28-1.86, P < .001) and among men, an HR of 1.65 (95% CI, 1.37-1.99, P < .001).

Table 3. Univariable and Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Models With and Without the LFI to Evaluate the Association Between Sex and Wait List Mortalitya.

| Factor | HR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariableb | Multivariable modelsc | ||

| Without LFI | With LFI | ||

| Women | 1.34 (1.03-1.74) | 1.30 (1.00-1.68) | 1.20 (0.92-1.57) |

| P value | .03 | .05 | .17 |

| MELDNa score per 5 units | 1.59 (1.41-1.80) | 1.55 (1.37-1.76) | 1.42 (1.25-1.62) |

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Age per 5 y | 1.14 (1.06-1.23) | 1.18 (1.09-1.27) | 1.10 (1.02-1.19) |

| P value | .001 | <.001 | .01 |

| Albumin level per 1 g/dL | 0.57 (0.46-0.71) | 0.65 (0.51-0.81) | 0.72 (0.57-0.90) |

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | .004 |

| LFI per 1-SD worsening | 2.00 (1.74-2.29) | NA | 1.76 (1.52-2.03) |

| P value | <.001 | NA | <.001 |

| Akaike information criterion | NA | 2462 | 2408 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; LFI, Liver Frailty Index; MELDNa, laboratory-based Model for End-Stage Liver Disease incorporating sodium level; NA, not applicable.

Calculated with the addition of confounding variables, adjusted for within-center correlations.

Other variables that were significant in univariable analysis but not in multivariable analysis were Hispanic ethnicity, diabetes, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and height.

All variables associated with wait list mortality with a P value of less than .10 in univariable analysis were evaluated for inclusion in the final multivariable model and eliminated using backward regression.

In a sensitivity analysis evaluating the association among sex, frailty, and wait list mortality in the real-world context of differing transplant rates between women and men using competing risk regression, the results remained qualitatively unchanged (eTable 2 in the Supplement). In mediation analysis to quantify the contribution of frailty to the sex gap in wait list mortality, we estimated that 13.0% (0.5%-132.0%) of the sex gap in wait list mortality was mediated by frailty.

Exploration of Disease Etiology and Frailty by Sex

Last, we performed exploratory analyses to evaluate the association between disease etiology and frailty. Liver Frailty Index scores were similar between women and men for every disease etiology except for autoimmune/cholestatic disease, for which women had a significantly higher median LFI score than men (3.89 [95% CI, 3.41-4.38] vs 3.57 [95% CI, 3.07-4.05]; P = .003) (eTable 1 in the Supplement). However, autoimmune/cholestatic disease etiology was not associated with wait list mortality (HR, 1.02; 95% CI 0.66-1.56; P = .94), nor was there a significant interaction between the LFI and autoimmune/cholestatic disease etiology (P = .22 for the interaction term).

Discussion

In our multicenter FrAILT study of 1405 patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplant, we observed that women displayed higher rates of frailty than men. This observation was true despite lower prevalence of medical comorbidities in women, comparable MELDNa scores at the time of assessment, and similar rates of ascites and hepatic encephalopathy. This sex difference in frailty attenuated the association between female sex and wait list mortality and improved model quality for estimation of wait list mortality (as assessed by the Akaike information criterion). Mediation analysis allowed us to quantify this outcome: an estimated 13.0% of the sex gap in wait list mortality was attributable to frailty.

Although the sex difference in the individual components of the frailty score as well as the composite index was numerically small (albeit statistically significant) and accounted for a relatively small proportion of the gender gap in wait list mortality, the greatest clinical significance of our data lies at the population level. This outcome is an effect that must be multiplied by the 15 years during which it has persisted across the entire US liver transplant system and will continue to persist if it is not recognized. If it is not recognized, it cannot be addressed. Our analyses are novel because we were able to identify—and quantify—the contribution of frailty to this gender gap, which has not previously been reported owing to lack of granular and objective frailty data. The FrAILT cohort is unique and distinct from other cohorts, including the United Network for Organ Sharing/Organ Procurement and Transport Network registry, in that it contains an objective assessment of frailty, which studies have shown is potentially modifiable in patients with cirrhosis.17

Based on our clinical experience as transplant clinicians, our team hypothesized that women would display higher rates of frailty than men for 2 major reasons. First, women had more than double the rate of cholestatic liver disease, and cholestasis is associated with accelerated bone mineral loss as well as direct myotoxicity.18 However, although women with cholestatic liver disease displayed higher rates of frailty than men with cholestatic liver disease, both women and men with cholestatic liver disease displayed much lower LFI scores, indicating better physical function than patients with any other disease etiology. Second, women in the general population display higher rates of frailty components (eg, weakness, low levels of physical activity, and exhaustion).19 Indeed, we observed that women in our cohort performed significantly worse than men in each of the LFI components, in line with findings in the general population. Given the known association between frailty and mortality in patients with cirrhosis, this sex difference in frailty could plausibly explain our findings.

We note that interpretation of our findings requires a general understanding of the sex-related issues that we considered during development of the LFI. Population-based norms for grip strength are lower in women than men. As a point of reference, among US women and men without known cirrhosis and aged 55 to 59 years (where the median age of our cohort was), median dominant hand grip strength was 38.7 (IQR, 32.4-47.8) kg in men and 24.1 (IQR, 20.7-30.2) kg in women. Therefore, we developed the LFI using grip strength adjusted by sex-specific z scores. We specifically explored sex differences in chair stands and balance and sex-specific associations with wait list mortality but did not observe any. Therefore, we believe that the LFI is accurately scaled by sex and accounts for the expected sex-based differences. It is still possible, however, that biological differences in the components contributing to the sex difference in the LFI were to be expected, but we would not expect these differences to mediate the association between sex and wait list mortality.

Limitations

Additional limitations include the fact that our study only enrolled patients who were seen in the ambulatory setting, limiting the generalizability of our results to those who are acutely ill. Because frailty assessments were only conducted during clinic visits, we do not know how frailty might have changed at the end of follow-up. Although we believe that multicenter enrollment enhances our study’s generalizability to transplant patients in a wide range of centers, another potential limitation is the heterogeneity of our multicenter data. Sensitivity analyses evaluating the associations between frailty and the gender gap in wait list mortality with or without center stratification yielded similar results and conclusions. The sex differences that we observed were statistically significant but numerically small and must be interpreted in the context of liver transplant on a national scale during the 15 years that this disparity has been reported. Last, the observational design of this study precluded our ability to prove causality. Use of Cox proportional hazards regression as our primary analytic technique—rather than competing risks regression, which is often the favored statistical method to treat liver transplant wait list data20—allowed for more natural causal inference.

Conclusions

How do we place these findings in the context of current clinical transplant practice? Since the initial report that women experienced higher rates of wait list mortality than men,2 many explanations have been proposed—for example, underestimation of renal dysfunction using serum creatinine level in the MELDNa score or reduced access to size-appropriate livers—but little has changed in our transplant practice to directly address this disparity.6 This outcome is largely owing to the fact that these factors require changes in the liver transplant system at the national policy level, a process that is slow and requires the issue to be prioritized over many other critical issues, such as pediatric wait list mortality or geographic disparities in transplant access. What makes frailty unique among the explanatory factors for this mortality gap between women and men is that the gap is potentially modifiable—and modifiable in ways that are immediately actionable at the level of the patient, the clinician, and the center. Clinicians can use these data to advise women awaiting liver transplant of their frailty-related excess mortality risk as motivation to engage in exercise and nutrition-based interventions in an attempt to mitigate this effect. Centers can play a role by incorporating systematic measurement of frailty into their routine procedures for baseline and longitudinal assessments of their liver transplant candidates to identify those patients—particularly women—at greatest risk. Our data offer the liver transplant community the opportunity to change this gap in wait list mortality between women and men.

eTable 1. Liver Frailty Index Scores by Disease Etiology and Sex

eTable 2. Subhazard Ratios in Univariable and Multivariable Competing Risk Regression to Evaluate the Association Between Sex and Wait-list Mortality

References

- 1.Lai JC, Terrault NA, Vittinghoff E, Biggins SW. Height contributes to the gender difference in wait-list mortality under the MELD-based liver allocation system. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(12):2658-2664. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03326.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moylan CA, Brady CW, Johnson JL, Smith AD, Tuttle-Newhall JE, Muir AJ. Disparities in liver transplantation before and after introduction of the MELD score. JAMA. 2008;300(20):2371-2378. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathur AK, Schaubel DE, Gong Q, Guidinger MK, Merion RM. Sex-based disparities in liver transplant rates in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(7):1435-1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03498.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen AM, Heimbach JK, Larson JJ, et al. Reduced access to liver transplantation in women: role of height, MELD exception scores, and renal function underestimation. Transplantation. 2018;102(10):1710-1716. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Locke JE, Shelton BA, Olthoff KM, et al. Quantifying sex-based disparities in liver allocation. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(7):e201129. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verna EC, Lai JC. Time for action to address the persistent sex-based disparity in liver transplant access. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(7):545-547. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nephew LD, Goldberg DS, Lewis JD, Abt P, Bryan M, Forde KA. Exception points and body size contribute to gender disparity in liver transplantation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(8):1286-1293.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. ; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group . Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146-M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai JC, Rahimi RS, Verna EC, et al. Frailty associated with waitlist mortality independent of ascites and hepatic encephalopathy in a multicenter study. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(6):1675-1682. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M85-M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.M85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang CW, Lebsack A, Chau S, Lai JC. The range and reproducibility of the Liver Frailty Index. Liver Transpl. 2019;25(6):841-847. doi: 10.1002/lt.25449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weissenborn K, Rückert N, Hecker H, Manns MP. The Number Connection Tests A and B: interindividual variability and use for the assessment of early hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol. 1998;28(4):646-653. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(98)80289-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lai JC, Dodge JL, Kappus MR, et al. ; Multi-Center Functional Assessment in Liver Transplantation (FrAILT) Study . Changes in frailty are associated with waitlist mortality in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2020;73(3):575-581. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.VanderWeele TJ. Mediation analysis: a practitioner’s guide. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37(1):17-32. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emsley R, Liu H. PARAMED: Stata module to perform causal mediation analysis using parametric regression models. Updated April 26, 2013. Accessed July 23, 2020. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s457581.html

- 16.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496-509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams FR, Berzigotti A, Lord JM, Lai JC, Armstrong MJ. Review article: impact of exercise on physical frailty in patients with chronic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50(9):988-1000. doi: 10.1111/apt.15491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guañabens N, Cerdá D, Monegal A, et al. Low bone mass and severity of cholestasis affect fracture risk in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(7):2348-2356. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexandre TDS, Corona LP, Brito TRP, Santos JLF, Duarte YAO, Lebrão ML. Gender differences in the incidence and determinants of components of the frailty phenotype among older adults: findings from the SABE Study. J Aging Health. 2018;30(2):190-212. doi: 10.1177/0898264316671228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim WR, Therneau TM, Benson JT, et al. Deaths on the liver transplant waiting list: an analysis of competing risks. Hepatology. 2006;43(2):345-351. doi: 10.1002/hep.21025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Liver Frailty Index Scores by Disease Etiology and Sex

eTable 2. Subhazard Ratios in Univariable and Multivariable Competing Risk Regression to Evaluate the Association Between Sex and Wait-list Mortality