Abstract

Background:

Betel nut (areca) is the world’s fourth most commonly used addictive substance. Arecoline, a muscarinic agonist in areca, is also a partial agonist for the addiction-related high-affinity brain nicotine receptors. In many countries, smokeless tobacco is commonly mixed with areca.

Objective:

We sought to evaluate the knowledge of self-harm, and addiction associated betel quid use in an unban population.

Methods:

We conducted a survey study of 200 betel quid users in Yangon, Myanmar, and a survey of betel quid vendors to determine the relative amounts of areca and tobacco in the available quids.

Results:

The data determined that a large majority of the survey subjects (84%) used tobacco with their areca. Users had a general awareness that betel chewing was “a bad habit” (85%) and 80% were aware of the cancer risks. Understanding areca addiction remains a challenge since, aside from the strong muscarinic activity of arecoline stimulating salivation, overt neurologic effects are difficult for even the users to identify. Fifty eight percent of the respondents indicated that chewing betel quid had effects like drinking coffee, and 55.5% indicated that it had effects like drinking alcohol. Data obtained from the quid vendors indicated that 75% added tobacco in equal amounts to areca.

Conclusion:

The concomitant use of nicotine and areca indicates that betel quid addiction includes a significant component of nicotine dependence. However, the additional activities of areca, including the muscarinic effects of arecoline, indicate that potential cessation therapies should optimally address other factors as well.

Keywords: Areca, tobacco, addiction, cancer, drug dependence, cessation therapy

Introduction

Most of South Asia has an ancient cultural tradition of chewing preparations of areca, commonly known as “betel nut” or “betel quid.” Although widely used, the term “betel nut” is a misleading term. It arose from the fact that areca “nut” is wrapped in the leaf or inflorescence of the vine Piper betle. Areca “nut” is actually not a true nut, but rather the central stone of the fruit (drupe) of the tropical palm tree Areca catechu (Gupta & Warnakulasuriya, 2002). The leaf is swabbed with slaked lime (calcium oxide and calcium hydroxide), and pieces of areca, usually with other ingredients are wrapped together in the leaf to form a packet known as a betel quid (Rooney, 1993). This combination is known by many names in the various countries where it is used; for example, it is called paan in India, and in neighboring Myanmar it is kunya. The areca nut has been known by different names around the world (India: supari, Sri Lanka: puwak, Thailand: mak) and has been used in different forms (ripe, unripe, partially ripe, sun-dried, cured) (WHO, 2004). Additives to the quid also vary widely among countries, communities, and individuals and may include spices, sweeteners, catechu (a resinous extract from the wood of the Acacia tree), and very often tobacco (Rooney, 1993). Historically, the caustic lime is added to the betel quid since it makes the absorption of the active alkaloids more efficient, although the lime itself can increase the damage to tissues in the mouth (Thomas & MacLennan, 1992).

With an estimated 600 million users worldwide, areca is one of the four most commonly used addictive substances in the world, along with alcohol, caffeine, and tobacco. Although all of these addictions are to varying degrees socially tolerated, like tobacco use, areca use presents a serious public health burden due to its potential to cause oral disease and cancers (Garg, Chaturvedi, & Gupta, 2014; Song, Wan, & Xu, 2015; Trivedy, Craig, & Warnakulasuriya, 2002).

Areca is widely used by the people of Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Myanmar, China, Taiwan, Papua New Guinea, and Palau of the West Pacific, to name a few. The percentages of users vary from country to country. Twenty to forty percent of Indian, Pakistani, and Nepalese populations use betel quid, whereas 72–80% of Palauan population consume areca (Gupta & Warnakulasuriya, 2002; Lee et al., 2012). Other countries like Thailand have shown a downward trend of consumption. However, due to migration of people, areca use is often reported in the Western World as well (Auluck, Hislop, Poh, Zhang, & Rosin, 2009; Changrani, Gany, Cruz, Kerr, & Katz, 2006; Pobutsky & Neri, 2012; Warnakulasuriya, 2002), and areca products are readily available in specialty food stores across the U.S.A. (Bachman, 2013).

Areca use in Asia has a tradition of thousands of years (Krais et al., 2017; Rooney, 1993; Van der Veen & Morales, 2015; Williams, Malik, Chowdhury, & Chauhan, 2002), and the relatively recent spread of tobacco use into Asia has permitted the facilitation of enhanced addiction with nicotine dependence (Gupta & Warnakulasuriya, 2002; Niaz et al., 2017). In countries like Myanmar and India, where smokeless tobacco is commonly mixed with areca and the other ingredients of the betel quid, oral cancer has become the most common form of cancer (Akhtar, 2013; Lee et al., 2012; Shah, Chaturvedi, & Vaishampayan, 2012). An estimated 23 million of the 54 million inhabitants of Myanmar chew betel quids. Most chewers obtain their betel quid from small roadside shops, of which there are approximately 15,000 in Yangon alone (Glatman, unpublished).

Areca is a recognized class 1 carcinogen, and its traditional preparation with slaked lime and other ingredients promotes submucosal fibrosis and other oral health problems (WHO, 2004). Betel quid use has been formally demonstrated and validated to be an addictive substance using DSM-5 criteria (Lee et al., 2018). Subjective reports suggest that areca and betel quid chewing produces a sense of euphoria, sweating, salivation, palpitations, heightened alertness, relaxation, improved digestion, and increased work capacity (Winstock, 2002). Small-scale studies have suggested the dependency potential of areca use; however, definitive studies testing this hypothesis are lacking (Winstock, Trivedy, Warnakulasuriya, & Peters, 2000). In general, this is because betel quid use and addiction is a very understudied area (Little & Papke, 2015). The widespread cultural acceptance of the practice in areas where it is used is comparable to tobacco use 25 years ago, when big tobacco companies argued that “people smoke not because they are addicted, but because smokers find smoking a pleasurable activity with certain emotional and cognitive benefits.” (Robinson & Pritchard, 1992). This claim was not even credible when it was made in 1992 (Hughes, 1993), although it might have been believed by many smokers fifty years earlier. We simply do not know enough about the potentially addictive molecules in areca to understand the factors that compel the habitual use of betel products. However, one of well-known active molecules in areca, arecoline, was recently shown to be a partial agonist of the same brain nicotine receptors that are associated with tobacco addiction (Papke, Horenstein, & Stokes, 2015), suggesting a common mechanism for the two addictions. This addictive potential would certainly be augmented in users who include tobacco as an additive to their betel quid.

General knowledge of both the addictive properties and health hazards of areca use make a compelling case for helping individuals treat their addiction and improve their health. The question arises then, what is the level of appreciation of ordinary betel quid users for these risks? To address this, we conducted two surveys, the first survey interviews with betel quid users in the vicinity of betel quid stands in Yangon to determine the attitudes and knowledge of these typically low-income users. The main data set of the first survey represents two sample groups of 100 subjects each, who were surveyed at very different times of the Myanmar year, the driest and the wettest. One important issue of the user survey was the degree to which the use of betel quid facilitated the use of smokeless tobacco, mixed into the betel quid. The second survey was of betel quid vendors to get an objective measure of the frequency with which tobacco was mixed with the betel quid available to the survey subjects and the relative amounts of tobacco and areca present in the quids.

Methods

Betel quid user survey

Participants

All subjects were current betel quid chewers 18 years of age or older. Potential participants were approached at random by interviewers and asked if they were areca users and would be willing to participate in a survey. Interviews were conducted in tea shops or beverage stands in the vicinity of betel quid stands selected at random at various locations around Yangon (see supplementary Figure S1). Subjects received no compensation other than a soft drink or a cup of tea during the interview. Equal numbers of interviews (100 each) were conducted in January and August of 2018.

Procedures

Trained interviewers were all native speakers of Burmese and fluent speakers of English. They gave personal interviews using a questionnaire lasting on average 10–15 min. No personal identifiers were obtained from any of the respondents and all answers were kept anonymous. The answers were translated by the interviewers from Burmese to English and the data collated and compiled by the first author, who had no personal contact with the subjects aside from being present at some of the interview sites in January. Data were compiled and statistics calculated using Excel (Microsoft).

Measures

The first part of the questionnaire covered demographic information on age and education as well as background questions related to their use of areca products. The second part of the questionnaire covered their personal experience with areca products, their subjective experiences of betel quid use, and their knowledge/opinions of health issues related to use of betel products. The second group of subjects was asked an additional set of questions regarding their motivations for chewing betel nut.

Betel quid composition survey

We obtained additional data from a random selection of 12 betel quid vendors in Yangon in the same neighborhoods where users were interviewed. Each vendor made three quids in the presence of one of the coauthors or a member of the survey team. The quids were weighed at each stage, beginning with the leaf, to evaluate the amount of lime, areca, and tobacco added.

Results

The demographics of the two survey samples were similar (supplementary Figure S2). Most subjects were aged 25–45, and 85% of the subjects in the January survey and 86% in August were male. The educational background of the two groups was also similar, with most subjects having a high school education or equivalent. This was somewhat higher than reported in the 2009 Noncommunicable Disease Risk Factor Survey (STEPS) conducted by the World Health Organization of 7450 households across Myanmar, where only 18% of their study subjects had completed secondary education (WHO, 2009). Similar to the STEPS survey, most of our subjects reported that they were “self-employed.”

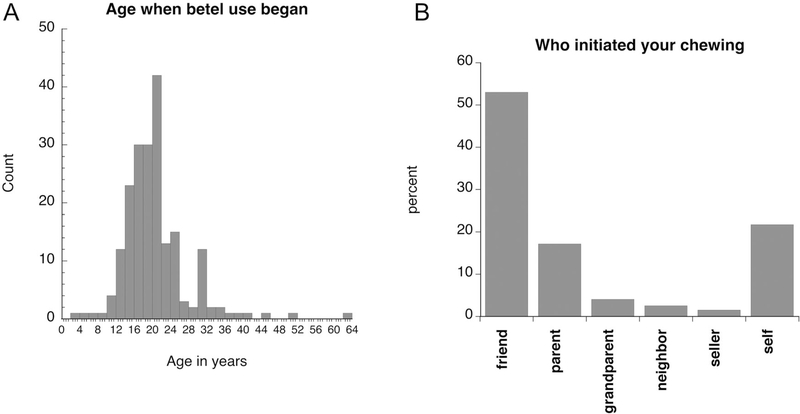

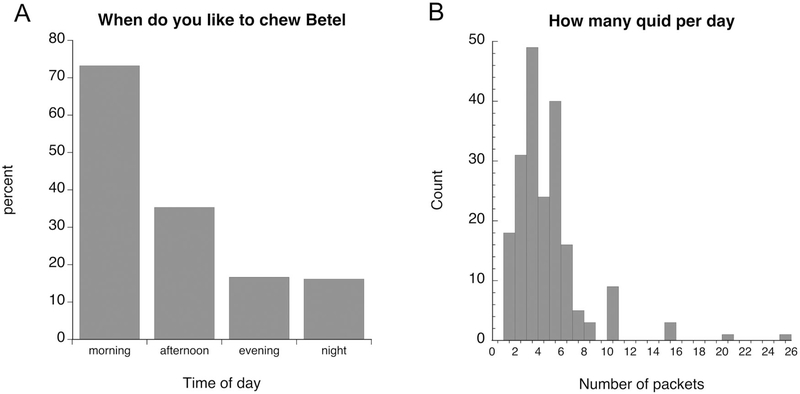

Most of the survey participants reported that they began chewing betel quid by the age of about 20, although several began as children or adolescents (Figure 1A). Not surprisingly, most participants indicated that they started chewing betel quid with friends, although a significant number (20%) indicated that they picked up the practice on their own (Figure 1B). Most respondents indicated (Figure 2A) that that their favorite time to chew betel quid was in the morning (73%), followed by afternoon (35%), and 7% indicated that they chewed all throughout the day. On average the subjects indicated that they chewed 4.3 quids per day (median = 4), although there were outliers who chewed considerably more (Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Initial use of areca. (A) The average age at which subjects began using betel quid was 20 years old (±0.5), with a median age of 19. (B) Leading influences on the initiation of betel use.

Figure 2.

Daily use of betel quid by study subjects. (A) Preferred time(s) of day. Although the highest reported use was in the mornings, 13% of the subjects reported using betel quid at all times of day. (B) The average number of quids chewed per day was 4.3 (±0.2), with a median of 4.

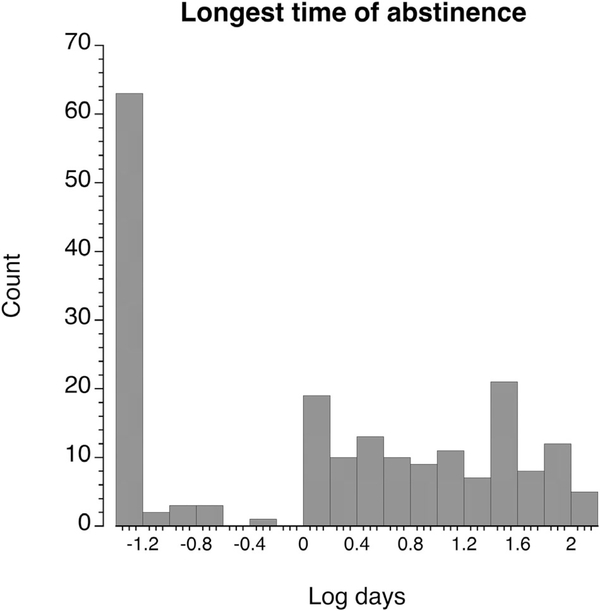

The answers to the question of the longest period of abstinence from betel quid over the last year was clearly bimodal (Figure 3), with 36.5% not having missed a single day in the past year. A significant number (17%) reported that they had gone without betel for 1 or 2 days, and the remainder reported variable periods of abstinence of up to three months or more.

Figure 3.

The longest period without chewing betel quid within the last year. The subjects fell into two groups, with 37% reporting that they had not gone as long as a day without chewing, and the remaining 63% had varying durations of abstinence. Not fitting a normal distribution, data were plotted as the log of the duration. For those subjects who reported abstinence periods of a day or longer, the average was 10.1 days (±1.1), with a median of 10 days.

The survey subjects reported that they spent on average 27,700 ± 1640 (median 24,000) Myanmar Kyat per month on betel quid. Currently, the minimum salary in Yangon is 4800 Myanmar Kyat per day, so for people making minimum wage the reported monthly outlay for betel quid equated to a week’s salary.

Table 1 provides a summary of the answers to the series of yes/no questions. For the most part, the answers to these questions were similar for the two sample groups. One of the largest disparities between the two sample groups was in response to the question, “Does betel nut have effects in the brain?” Users had a general (85%) awareness that betel chewing was “a bad habit,” a small majority (55%) acknowledged that they were addicted, and 51% had tried to quit. There was also a general awareness of the cancer risks associated with betel use, with 85.5% aware of an increased risk of mouth cancer and 77% aware of an increased risk of throat cancer. As with the users of tobacco products alone (Shiffman & Terhorst, 2017), users had some difficulty identifying the CNS effects of betel. Only slightly more than half the participants said they thought that betel had effects in the brain. A total of 58% respondents indicated that it had effects like drinking coffee, and 55.5% indicated that it had effects like drinking alcohol. Interestingly, of the 36% who said it had no effects in the brain, 68% of those indicated that it had either coffee-like or alcohol-like effects or both, suggesting a lack of appreciation of the brain as a site of action for these drugs. An increased capacity for work was reported by 33.5%. A large majority of the survey subjects (84%) used tobacco with their quid, and 58.5% also smoked tobacco, but only 10.5% indicated that they also chewed tobacco without betel. Comparing those who do not add tobacco to the overall data showed no other obvious differences.

Table 1.

Survey responses to yes or no questions.

| Question | January | August | Average |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you mix tobacco with betel? | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.84 |

| Do you smoke tobacco? | 0.55 | 0.62 | 0.585 |

| Do you ever chew tobacco without betel? | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.105 |

| Does anyone else in your house chew betel? | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.50 |

| Do you use betel in religious ceremonies? | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.535 |

| Have you ever chewed in a forbidden area | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.305 |

| Do you experience sweating while chewing? | 0.54 | 0.64 | 0.59 |

| Do you think chewing betel nuts is a good habit? | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.15 |

| Do you think you are addicted to betel nut chewing? | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.545 |

| Have you ever tried quitting the habit? | 0.56 | 0.46 | 0.51 |

| Will you try to stop others from chewing betel nut? | 0.77 | 0.68 | 0.725 |

| Has anyone tried to stop you from chewing betel nut? | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.645 |

| Have you ever consulted a doctor because of betel nut? | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.11 |

| Does chewing betel nuts have any immediate effects? | 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.475 |

| Does chewing betel make it difficult to chew or swallow? | 0.39 | 0.68 | 0.535 |

| Do you think chewing betel nuts can cause mouth cancer? | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.855 |

| Do you think chewing betel nuts can cause throat cancer? | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.77 |

| Is a small quantity of betel nuts is dangerous to health? | 0.69 | 0.51 | 0.60 |

| Do you know of any advantages of chewing betel nuts? | 0.37 | 0.26 | 0.32 |

| Have you ever read any articles about betel nut? | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.51 |

| Have you ever had any dental problems? | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.265 |

| Have you ever had problems with your tongue? | 0.36 | 0.45 | 0.405 |

| Have you ever experienced any hearing difficulties? | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.155 |

| Do you have difficulty in everyday speaking? | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.455 |

| Do you think chewing of betel nuts can cause skin rashes? | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.25 |

| Are there effects of betel nut chewing on heart? | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.555 |

| Are there effects of betel nut chewing in the brain? | 0.56 | 0.16 | 0.36c |

| Are there effects of betel similar to drinking coffee? | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.58 |

| Are there effects of betel nut similar to drinking alcohol? | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.555 |

| Does betel increase your capacity to work? | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0.335 |

| Does chewing of betel nut can stimulate your salivation? | 0.94 | 0.81 | 0.875 |

| Do you think chewing of betel nuts can affect pregnancy? | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.865 |

| Does chewing of betel nuts have any effect on kidneys? | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

The people surveyed in August were also asked an additional set of questions about what conditions made them more or less likely to want to chew betel nut (Table 2). The strongest motivation was “being bored” with 56%. Only 7% said that being bored made them less likely to chew betel. That was by far the lowest number for the “less likely” reply. Of the seven who said they did not chew betel because they were bored, four said they did with friends, which was the second highest motivating factor overall.

Table 2.

Motivations to chew betel quid.

| Condition | More | No difference | Less |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | |||

| Feeling nervous or anxious | 15 | 70 | 15 |

| Feeling relaxed or comfortable: | 37 | 49 | 14 |

| Feeling sad or unhappy: | 22 | 66 | 12 |

| Feeling bored: | 56 | 37 | 7* |

| Feeling happy: | 20 | 62 | 18 |

| Being with friends: | 41 | 47 | 12 |

| Feeling tired or sleepy: | 29 | 48 | 23 |

| Being busy with my hands: | 18 | 48 | 34 |

| Trying to concentrate: | 29 | 41 | 30 |

| (b)* | |||

| Feeling nervous or anxious | 1 | ||

| Feeling relaxed or comfortable: | 0 | ||

| Feeling sad or unhappy: | 1 | ||

| Feeling bored: | 0 | ||

| Feeling happy: | 2 | ||

| Being with friends: | 4 | ||

| Feeling tired or sleepy: | 1 | ||

| Being busy with my hands: | 1 | ||

| Trying to concentrate: | 1 | ||

Responses of the seven subjects who were not inclined to chew when bored, regarding what conditions did make them feel more like chewing.

Composition of betel quids in yangon

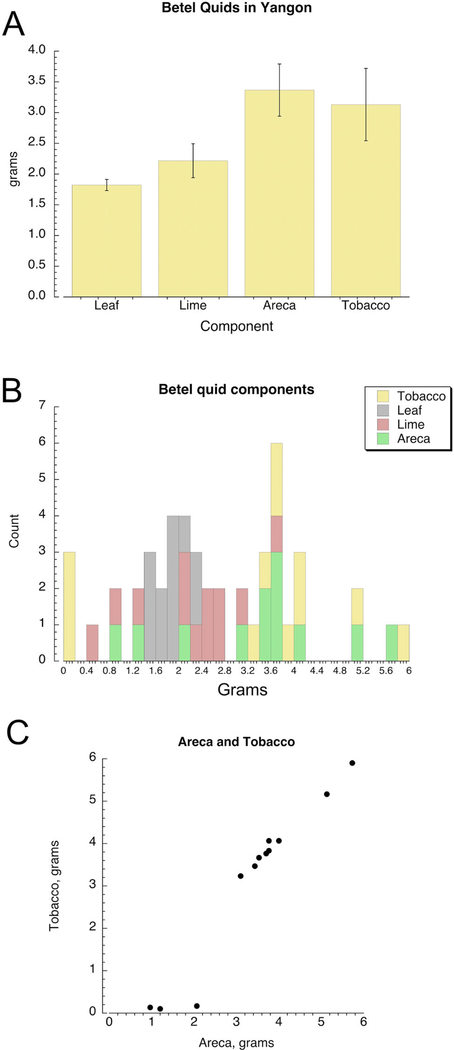

While the composition of betel quids (paan) can be quite variable in some countries like India (Patidar, Parwani, Wanjari, & Patidar, 2015; Rooney, 1993; WHO, 2004), in Myanmar the quid tend to be rather simple, containing primarily just the four key ingredients, betel leaf, slaked lime, areca, and tobacco. In order to cross-validate the respondents’ reports of combined use of areca with tobacco, we obtained additional data from a random selection of betel quid vendors in Yangon. Although the quids from the different vendors varied significantly, the individual vendors were each relatively consistent in how they assembled their three sample quids, with a standard deviation in the composition of less than 15% of the mean for each ingredient and the total weight, so that the three quid averages were used to represent each vendor in the group comparisons. The averages from the 12 vendors are shown in Figure 4A. The individual values are histogramed in Figure 4B. As expected, the leaf weights were the most consistent factor among the vendors, with a standard deviation of 16% the average. The most variable factor was the amount of tobacco, with a standard deviation of 62% the average. As can be seen in the histograms, the reason for this was that three of the vendors added little or no tobacco at all. For most the other vendors, there was a clear correlation between the amounts of areca and tobacco in the quids (Figure 4C). This variation in tobacco composition was consistent with the survey result that indicated that a few of the respondents preferred and could obtain quid without tobacco.

Figure 4.

The composition of betel quids sold by vendors within the study area. (A) The average values (±SEM) in grams of the four principle quid components. (B) Histograms of the values from the 12 vendors sampled. (C) The generally strong correlation between the amounts of tobacco and areca in the quids made by individual vendors.

Discussion

The cultural tradition of areca nut use in South Asia goes back thousands of years (Krais et al., 2017; Van der Veen & Morales, 2015), while tobacco use in European cultures has a much shorter history (Papke, 2014). In the centuries following Magellan’s first visit to the Philippines in 1521, when the ship’s doctor recorded the natives’ practice of chewing areca nut (Mack, 2001), there came the potential for these two addictions to synergize both psychologically and pathologically. Unfortunately, general awareness of the health impact of tobacco smoking, especially as related to cancer, only emerged in the mid-twentieth century, and likewise in 1960 areca, especially in combination with tobacco, was implicated as a causal factor in oral cancers (Muir & Kirk, 1960). Although areca alone is recognized as a class 1 carcinogen (WHO, 2004), the likelihood of cancer is greatly increased when it is combined with tobacco (Gupta, Pindborg, & Mehta, 1982).

One of our key findings is that users had an awareness of the harms associated with using betel quid, but a lack of awareness of its addictive effects. The scope of our survey was similar to one conducted in two socioeconomically distinct areas of Karachi (Khan et al., 2013). In that study, as in the present study, most respondents were aware of the health liability of betel quid chewing. While most acknowledged it was a bad habit, only about half perceived that they were addicted. Curiously, less than half (≈30%) of those respondents felt that chewing betel quid had any immediate effects, including the stimulation of saliva (<35%). The perception of CNS effects was also rather low in the Karachi study, with 47% classifying it as a stimulant, and only 14% identifying it as a depressant. One notable difference was that in the Karachi study, less than half of the subjects (43%) indicated that they mixed their areca with tobacco, suggesting that for the subjects in the Karachi study the most important factor was areca.

Another key finding observed in our survey was the reported dual use of areca and tobacco. Our results of the vendor survey were in good agreement with the user survey, indicating that, just as the majority of users reported chewing tobacco in their quid, the majority of vendors added tobacco to their products. Interestingly, for the vendors who added tobacco, we saw a strong correlation between the amount of areca and the amounts of tobacco, with essentially equal amounts of each. This suggests that for most of the habitual betel quid users in Yangon, tobacco and areca probably contribute equally to their dependence.

Our survey of vendors was based a random selection of from the same neighborhoods where interviews were conducted. The vendors work from unregulated street-side stalls and usually sell only betel quid (plus a few other goods sometimes, i.e. cigarettes). They purchase the components of the quids from larger wholesalers, who in turn buy from larger wholesalers in the city’s large produce market or directly from the farms. Almost all betel quid sold to users in Yangon is sold through these street-side vendors, either directly or from secondary sellers who purchase packets of quid and offer them for sale along with bottled water to drivers stopped in traffic.

The combined effects of areca and tobacco on dependence is not clear. As previously noted, the arecoline in areca is itself a partial activator of brain nicotine receptors (Papke et al., 2015); it is therefore interesting to consider how the pharmacological effects of a combination of areca and tobacco compare to tobacco alone. The addition of a partial agonist, even at a low concentration, has a general tendency to blunt the effects of the full agonist (Papke, Trocme-Thibierge, Guendisch, Abbas Al Rubaiy, & Bloom, 2011), so it is unlikely that the combination of these drugs in betel quid would be additive to the effects of tobacco alone. However, without a better understanding of areca pharmacology, it is not possible to predict what other interactions might promote the combined use.

The likelihood of cancer is greatly increased when areca is combined with tobacco (Gupta et al., 1982). But it is important to note that areca alone is recognized as a class 1 carcinogen (WHO, 2004). Apart from causing oral submucosal fibrosis, leukoplakia, and oral cancer, the habit can cause a variety of other diseases and metabolic derangements (Javed, Bello Correra, Chotai, Tappuni, & Almas, 2010). Alkaloids, tannins, polyphenol, fats, carbohydrates, crude fiber, protein, and water are some of the compounds that have been extracted from areca. These compounds have various effects ranging from carcinogenic, anticarcinogenic, mutagenic, and genotoxic (Sharan, Mehrotra, Choudhury, & Asotra, 2012). Several mechanisms of actions result in toxicity: (1) The production of reactive oxygen species produced from auto-oxidation from the polyphenols in saliva. (2) Nitrosation of alkaloids by the presence of slaked lime. (3) Release of chronic inflammatory mediators from host cells, leading to formation of reactive oxygen species and pro-inflammatory cytokines, resulting in tissue damage, and promotion of the transformation and growth of cancer cells (Hung et al., 2007).

It is well documented that prolonged and excessive use of areca nut, with or without tobacco, has the potential for the development of premalignant (leukoplakia, oral submucous fibrosis) and malignant lesions (oral squamous cell carcinoma). In countries like India, where there is widespread use of areca, most often in combination with tobacco, the most common form of cancer is oral (Manoharan, Tyagi, & Raina, 2010). Leukoplakia is a white plaque in the oral mucosa. 4.2% of leukoplakias develop into oral squamous cell carcinoma over a 20-year period (Yen, Chen, Chang, & Chen, 2008). In 62% of cases, cessation of areca nut chewing results in resolution of lesions. Oral submucous fibrosis is characterized by increased fibrosis of lamina propria and epithetical atrophy. It results in stiffening of the oral mucosa, accompanied with a burning sensation. 7.6% of oral submucous fibrous lesions over a 17-year period develop into squamous cell carcinoma (Trivedy et al., 2002). The risk can be reduced by eliminating the habit of using areca.

The third key finding is related to quitting. Our data show that, even though the majority of betel quid users on the streets of Yangon are aware of some of the health effects of using the product, only about half tried quitting (and most for only a short period of time). These results are consistent with other surveys of betel quid use in Myanmar (Myint, Narksawat, & Sillabutra, 2016). Although the incidence of oral cancers is very high in Myanmar, oral health screens are at best sporadic and voluntary, so there is a great need for government-sponsored public health education (Mizukawa et al., 2017). In India, gutka, commercially produced packets of areca and smokeless tobacco, carry graphic warnings of the oral health hazards (Gravely et al., 2016), while the hand-made quids widely available in Myanmar of course carry no such warnings. Moreover, in Myanmar there is not only ancient cultural acceptance of betel quid use, there is an expectation, at least in some communities, that men chew betel quid as an expression of their masculinity (Moe, Boonmongkon, Lin, & Guadamuz, 2016).

As noted previously, addiction to betel quid may be different from tobacco products alone because of the effects from areca nut, which potentially produce different psychoactive and withdrawal effects. We need better characterization of addiction to areca alone as well as in combination with tobacco. Nonetheless, we know some of the mechanisms of action of areca nut and tobacco, and this knowledge might guide our discovery of pharmacological treatments for this population. We also know that use occurs socially or when people are bored, which would inform us of the types of behavioral treatments that are necessary. Some of the challenges associated with cessation from betel quid use include its role in culture (e.g. religious ceremonies), traditional social and household use, and the lack of avenues to seek help through health professionals or government agencies. One recently implemented innovative approach is to use the betel quid vendors themselves to reach quid users, by providing oral health information and products (Glatman, 2018).

The sum impact of areca product use is certainly thousands of preventable cancers every year and much more precancerous oral disease. Due to the continued use of areca products by immigrant populations, the health liability of areca use is not limited to Asian nations. Although the majority of consumers were aware of the negative health effect of betel quid use, most were not cognizant of its addictive effects. One path to prevention of areca-related disease is to educate the population of the potential for addiction to betel quid and the health and financial costs associated with its addiction. But in order to have maximum effect on prevention and cessation, we also need to gain new insights into the root causes of areca addiction (see Commentary, this issue).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental data for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2019.1624774

References

- Akhtar S (2013). Areca nut chewing and esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma risk in Asians: A meta-analysis of case-control studies. Cancer Causes & Control, 24, 257–265. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0113-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auluck A, Hislop G, Poh C, Zhang L, & Rosin MP (2009). Areca nut and betel quid chewing among South Asian immigrants to Western countries and its implications for oral cancer screening. Rural Remote Health, 9, 1118 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19445556 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman SA (2013). Betel nut product characteristics and availability in King County, Washington: A secret shopper study (M. P. H.). Seattle, WA: University of Washington; Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1773/24272 [Google Scholar]

- Changrani J, Gany FM, Cruz G, Kerr R, & Katz R (2006). Paan and Gutka use in the United States: A pilot study in Bangladeshi and Indian-Gujarati immigrants in New York City. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 4, 99–110. doi: 10.1300/J500v04n01_07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg A, Chaturvedi P, & Gupta PC (2014). A review of the systemic adverse effects of areca nut or betel nut. Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology, 35(1), 3–9. doi: 10.4103/0971-5851.133702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatman S (2018). An innovative approach to an ancient problem. Social Innovations Journal, 47, 1–3. Retrieved from https://socialinnovationsjournal.org/75-disruptive-innovations/2824-an-innovative-approach-to-an-ancient-problem [Google Scholar]

- Gravely S, Fong GT, Driezen P, Xu S, Quah AC, Sansone G, … Pednekar MS (2016). An examination of the effectiveness of health warning labels on smokeless tobacco products in four states in India: Findings from the TCP India cohort survey. BMC Public Health, 16, 1246. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3899-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta PC, Pindborg JJ, & Mehta FS (1982). Comparison of carcinogenicity of betel quid with and without tobacco: An epidemiological review. Ecology of Disease, 1, 213–219. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6765307 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta PC, & Warnakulasuriya S (2002). Global epidemiology of areca nut usage. Addiction Biology, 7, 77–83. doi: 10.1080/13556210020091437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR (1993). Smoking is a drug dependence: A reply to Robinson and Pritchard. Psychopharmacology, 113, 282–283. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7855194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung SL, Lin YJ, Chien EJ, Liu WG, Chang HW, Liu TY, & Chen YT (2007). Areca nut extracts-activated secretion of leukotriene B4, and phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and elevated intracellular calcium concentrations in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Journal of Periodontal Research, 42, 393–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2006.00958.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javed F, Bello Correra FO, Chotai M, Tappuni AR, & Almas K (2010). Systemic conditions associated with areca nut usage: A literature review. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 38, 838–844. doi: 10.1177/1403494810379291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MS, Bawany FI, Shah SR, Hussain M, Arshad MH, & Nisar N (2013). Comparison of knowledge, attitude and practices of betelnut users in two socio-economic areas of Karachi. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 63, 1319–1325. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24392573 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krais S, Klima M, Huppertz LM, Auwarter V, Altenburger MJ, & Neukamm MA (2017). Betel nut chewing in Iron Age Vietnam? Detection of areca catechu alkaloids in dental enamel. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 49, 11–17. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2016.1264647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Ko AM, Warnakulasuriya S, Ling TY, Sunarjo, Rajapakse PS, … Ko YC (2012). Population burden of betel quid abuse and its relation to oral premalignant disorders in South, Southeast, and East Asia: An Asian Betel-quid Consortium Study. American Journal of Public Health, 102, e17–e24. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C-H, Ko AM-S, Yang FM, Hung C-C, Warnakulasuriya S, Ibrahim SO, … Ko Y-C (2018). Association of DSM-5 betel-quid use disorder with oral potentially malignant disorder in 6 betel-quid endemic Asian populations. JAMA Psychiatry, 75, 261–269. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little MA, & Papke RL (2015). Betel, the orphan addiction. Journal of Addiction Research and Therapy, 6, 130–132. [Google Scholar]

- Mack TM (2001). The new pan-Asian paan problem. Lancet (London, England), 357, 1638–1639. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11425364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoharan N, Tyagi BB, & Raina V (2010). Cancer incidences in rural Delhi-2004–05. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 11, 73–77. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20593934 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizukawa N, Swe Swe W, Zaw Moe T, Moe Thida H, Yoshioka Y, Kimata Y, … Than S (2017). The incidence of oral and oropharyngeal cancers in betel quidchewing populations in South Myanmar rural areas. Acta Medica Okayama, 71, 519–524. doi: 10.18926/AMO/55589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moe T, Boonmongkon P, Lin CF, & Guadamuz TE (2016). Yauk gyar mann yin (Be a man!): Masculinity and betel quid chewing among men in Mandalay, Myanmar. Culture Health & Sexuality, 18, 129–143. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1055305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir CS, & Kirk R (1960). Betel, tobacco, and cancer of the mouth. British Journal of Cancer, 14, 597–608. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13773626 doi: 10.1038/bjc.1960.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myint SK, Narksawat K, & Sillabutra J (2016). Prevalence and factors influencing betel nut chewing among adults in West Insein Township, Yangon, Myanmar. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health, 47, 1089–1097. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29620822 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niaz K., Maqbool F., Khan F., Bahadar H., Ismail Hassan F., & Abdollahi M. (2017). Smokeless tobacco (paan and gutkha) consumption, prevalence, and contribution to oral cancer. Epidemiology and Health, 39, e2017009. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2017009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL (2014). Merging old and new perspectives on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochemical Pharmacology, 89(1), 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.01.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Horenstein NA, & Stokes C (2015). Nicotinic activity of arecoline, the psychoactive element of “betel nuts”, suggests a basis for habitual use and anti-inflammatory activity. PLoS One, 10, e0140907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Trocme-Thibierge C, Guendisch D, Al Rubaiy SAA, & Bloom SA (2011). Electrophysiological perspectives on the therapeutic use of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonists. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 337, 367–379. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.177485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patidar KA, Parwani R, Wanjari SP, & Patidar AP (2015). Various terminologies associated with areca nut and tobacco chewing: A review. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, 19, 69–76. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.157205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pobutsky AM, & Neri EI (2012). Betel nut chewing in Hawai’i: Is it becoming a public health problem? Historical and socio-cultural considerations. Hawaii Journal of Medicine & Public Health, 71, 23–26. Retrieved fromhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22413101 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JH, & Pritchard WS (1992). The role of nicotine in tobacco use. Psychopharmacology, 108(4), 397–407. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1410152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney DF (1993). Betel chewing traditions in South-East Asia. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shah G, Chaturvedi P, & Vaishampayan S (2012). Arecanut as an emerging etiology of oral cancers in India. Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology, 33, 71–79. doi: 10.4103/0971-5851.99726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharan RN, Mehrotra R, Choudhury Y, & Asotra K (2012). Association of betel nut with carcinogenesis: Revisit with a clinical perspective. PLoS One, 7, e42759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, & Terhorst L (2017). Intermittent and daily smokers’ subjective responses to smoking. Psychopharmacology (Berlin), 234, 2911–2917. doi: 10.1007/s00213-017-4682-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H, Wan Y, & Xu YY (2015). Betel quid chewing ithout tobacco: A meta-analysis of carcinogenic and precarcinogenic effects. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 27, NP47–NP57. doi: 10.1177/1010539513486921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SJ, & MacLennan R (1992). Slaked lime and betel nut cancer in Papua New Guinea. Lancet (London, England), 340, 577–578. Retrieved fromhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1355157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedy CR, Craig G, & Warnakulasuriya S (2002). The oral health consequences of chewing areca nut. Addiction Biology, 7, 115–125. doi: 10.1080/13556210120091482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Veen M, & Morales J (2015). The Roman and Islamic spice trade: New archaeological evidence. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 167, 54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnakulasuriya S (2002). Areca nut use following migration and its consequences. Addiction Biology, 7, 127–132. doi: 10.1080/13556210120091491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2004). Betel-quid and areca-nut chewing. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2009). Noncommunicable Disease Risk Factor Survey Myanmar 2009.

- Williams S, Malik A, Chowdhury S, & Chauhan S (2002). Sociocultural aspects of areca nut use. Addiction Biology, 7, 147–154. doi: 10.1080/135562101200100147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstock A (2002). Areca nut-abuse liability, dependence and public health. Addiction Biology, 7, 133–138. doi: 10.1080/13556210120091509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstock AR, Trivedy CR, Warnakulasuriya KA, & Peters TJ (2000). A dependency syndrome related to areca nut use: Some medical and psychological aspects among areca nut users in the Gujarat community in the UK. Addiction Biology, 5, 173–179. doi: 10.1080/13556210050003766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen AM, Chen SC, Chang SH, & Chen TH (2008). The effect of betel quid and cigarette on multistate progression of oral pre-malignancy. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine, 37, 417–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00652.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.