Abstract

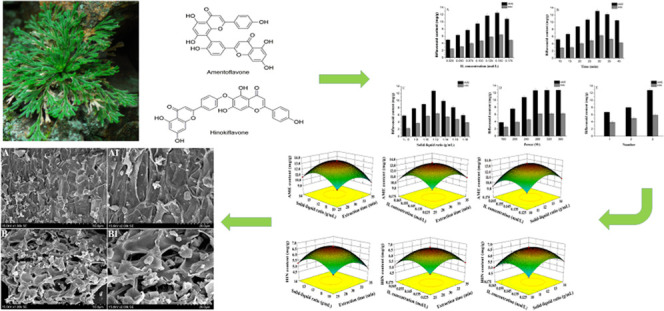

Selaginella tamariscina, a traditional Chinese medicine, contains a variety of bioactive components, among which biflavonoids are the main active ingredients and have antioxidant, antitumor, and anti-inflammatory properties. In this study, ultrasonic-assisted ionic liquid extraction (UAILE) is used for the first time to extract two main biflavonoids (amentoflavone (AME) and hinokiflavone (HIN)) from S. tamariscina. A high-performance liquid chromatography method is used for the simultaneous determination of AME and HIN in S. tamariscina. Then, three novel ILs are synthesized for the first time by a one-step method using benzoxazole and three acids or acid salts as raw materials, and the structures of the synthesized ILs are characterized by elemental analysis, infrared spectroscopy, and NMR spectroscopy, as well as the thermal stability of the ILs is evaluated by thermogravimetric analysis. After screening the extraction effects of three benzoxazole ILs, three pyridine ILs, and three imidazole ILs, it is found that [Bpy]BF4 is the best and therefore selected as the extractant. The optimal extraction process is explored in terms of the yields of AME and HIN from S. tamariscina by a single-factor experiments and response surface analysis. Under the optimal level of each influencing factor (IL concentration of 0.15 mol/L, solid–liquid ratio of 1:12 g/mL, ultrasonic power of 280 W, ultrasonic time of 30 min, and three extraction cycles), the extraction rates of AME and HIN from S. tamariscina are 13.51 and 6.74 mg/g, respectively. Moreover, the recovery experiment of [Bpy]BF4 on the extraction of biflavonoids shows that the recovered IL can repeatedly extract targets six times and the extraction rate is about 90%, which indicates that the IL can be effectively reused. UAILE can effectively and selectively extract AME and HIN, laying the foundation for the application of S. tamariscina.

1. Introduction

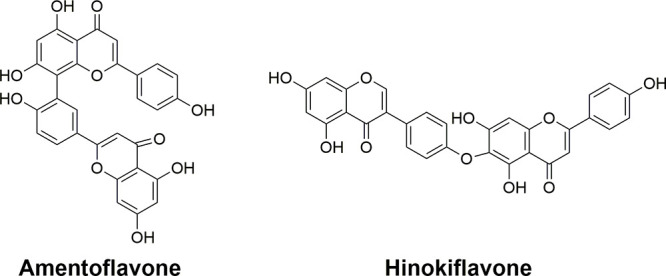

Selaginella tamariscina (Beauv.) Spring, known as Huiyang grass, is a perennial evergreen grass and is distributed in many places of China, including Guizhou, Yunnan, Shandong, Liaoning, and Hebei.1,2 It is mainly used to treat constipation, hematuria, inflammation, chronic hepatitis, gout, and hyperuricemia.3−5 The chemical components in S. tamariscina include biflavonoids, alkaloids, phenylpropanoids, and terpenoids.6−8 Among them, biflavonoids are the characteristic and main active ingredients, especially amentoflavone (AME) and hinokiflavone (HIN) (see Figure 1), which have a variety of significant biological properties such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidation, antivirus, antitumor, hypoglycemic, and vasodilator.9−13 For instance, AME reduces cell viability in hepatocellular carcinoma cells in a dose-dependent manner, but does not affect normal hepatocyte viability, which may be through downregulation of hexokinase 2 (HK2), thereby inhibiting the tyrosine kinase 2 (JAK2)/signaling and transcription activating factor 3 (STAT3) signaling pathway to prevent glycolysis.14 Yang and colleagues15 proved that HIN can inhibit the proliferation of three melanoma cancer cell lines (human melanoma A375, CHL-1 cells, and murine melanoma B16-F10 cells) and induce cancer cell apoptosis as well as prevent cancer cell migration, invasion, and cancer cell stage S for melanoma. In addition, Shim et al.16 found that HIN can inhibit the production of inflammatory mediators NO, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α and inhibit the expression of nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 induced by lipopolysaccharide, thereby showing anti-inflammatory properties.

Figure 1.

Structures of amentoflavone (AME) and hinokiflavone (HIN).

Biflavonoids have attracted the attention of many scholars due to their wide biological activities. Obtaining biflavonoids from medicinal plants is one of the main ways. Currently, there are many traditional methods for extracting biflavonoids, including diafiltration,17 soxhlet extraction,18 heating reflux extraction,19 and alkali-soluble acid precipitation.20 But these extraction methods have the disadvantages of being environmentally unfriendly and time-consuming, as well as having low extraction efficiency.

Ionic liquid (IL), a special molten salt, is usually composed of organic cations and inorganic or organic anions and is also called a room-temperature molten salt.21 Since the composition of ILs can be flexibly adjusted, there are many types of ILs such as imidazole, pyridine, quaternary ammonium, and quaternary phosphorus ILs. The anions cover almost all organic and inorganic anions and the representative anions are HSO4–, BF4–, PF6–, CF3COO–, Br–, etc.22 Compared with conventional organic solvents, IL has special properties, such as designability, low vapor pressure, large liquid range, and strong solubility.23,24 At present, the synthetic methods of ILs are mainly divided into a one-step method25 and a two-step method.26 The one-step synthesis method is a direct synthesis method, which means that the IL can be synthesized in one step through an acid–base neutralization reaction or quaternization reaction. It has the advantages of simple operation, low cost, no byproducts, and easy preparation.

Ultrasonic-assisted ionic liquid extraction (UAILE), a new green extraction approach, can more effectively extract target components from natural products, which can establish a method that has many advantages such as time-saving, simple operation, safety, and high extraction efficiency, and is suitable for the extraction of biflavonoids.27−29 Kou and colleagues30 used IL-ultrasonic-assisted extraction (UAILE) to extract turmeric polysaccharides from ginger, with a yield of 92.82%. Compared with traditional methods, UAILE not only significantly increased the yield of turmeric polysaccharides but also shortened the extraction time.

Based on the unique characteristics of ionic liquids, UAILE is used to extract the main biflavonoids of S. tamariscina, which has many advantages such as strong operability, time-saving, high extraction efficiency, and environment-friendly. First, through the screening of several ionic liquids, the best IL is selected as the extraction solvent. Moreover, process parameters are optimized through a single-factor experiment and response surface design. Finally, this optimal UAILE is compared with the traditional extraction methods, which can provide a reference for the research of biflavonoids.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of Ionic Liquids

Three new benzoxazole ILs, namely, benzoxazole methanesulfonate ([HBox]CH3SO3), benzoxazole hexafluorophosphate ([HBox]PF6), and benzoxazole trifluoroacetate ([HBox]CF3COOH), are synthesized by one-step synthesis. Elemental analysis, NMR, and infrared spectra analysis are used to characterize the structure of the synthesized ionic liquid, and thermogravimetric analysis is used to investigate the thermal stability of the ionic liquid.

2.1.1. Elemental Analysis

An elemental analyzer is used to determine N, C, H, O, N, and S elements of the three benzoxazole ILs. As shown in Table 1, the results indicate that the elemental contents of the ILs are 31.82–46.55% C, 1.92–4.17% H, 5.30–29.80% O, 5.30–6.49% N, and 14.83% S, which show that the elemental analysis test value of each compound is basically consistent with the theoretical value.

Table 1. Results of Elemental Analysis.

| N/% |

C/% |

H/% |

S/% |

O/% |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ILs | experimental value | theoretical value | experimental value | theoretical value | experimental value | theoretical value | experimental value | theoretical value | experimental value | theoretical value |

| [HBox]CH3 SO3 | 6.49 | 6.54 | 44.53 | 44.86 | 4.17 | 3.74 | 14.83 | 14.95 | 29.80 | 29.91 |

| [HBox]PF6 | 5.30 | 5.30 | 31.82 | 31.82 | 1.92 | 1.89 | 5.30 | 6.06 | ||

| [HBox]CF3COOH | 6.03 | 6.01 | 46.55 | 46.35 | 2.16 | 2.14 | 20.70 | 20.60 | ||

2.1.2. NMR Spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy can provide further insight into the chemical composition of the three benzoxazole ILs. [HBox]CH3SO31H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 10.68 (1H, s, H-7), 9.71 (1H, br s, H-8), 7.25 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, H-2), 7.21 (1H, t, J = 8.4 Hz, H-3), 6.98 (1H, d, J = 8.2 Hz, H-5), 6.85 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, H-4), 2.32 (3H, s, CH3SO3); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ: 40.2 (−CH3SO3), 116.6 (C-1), 119.1 (C-2), 119.8 (C-4), 124.6 (C-3), 129.9 (C-5), 151.2 (C-6).

[HBox]PF61H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 6.98 (1H, dd, J = 7.8, 1.6 Hz, H-2), 6.89 (1H, ddd, J = 8.0, 7.2, 1.6 Hz, H-3), 6.83 (1H, dd, J = 8.0, 1.5 Hz, H-5), 6.72 (1H, td, J = 7.5, 1.6 Hz, H-4); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 115.9 (C-5), 119.9 (C-2), 120.9 (C-4), 125.1 (C-3), 125.8 (C-1), 148.6 (C-6).

[HBox]CF3COOH 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 10.68 (1H, s, H-7), 9.71 (1H, br s, H-8), 7.25 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, H-2), 7.21 (1H, t, J = 8.4 Hz, H-3), 6.98 (1H, d, J = 8.2 Hz, H-5), 6.86 (1H, t, J = 7.9 Hz, H-4); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 115.8 (-CF3COO), 116.4 (C-5), 119.7 (C-2), 121.2 (C-4), 123.5 (C-3), 128.4 (C-1), 150.6 (C-6).

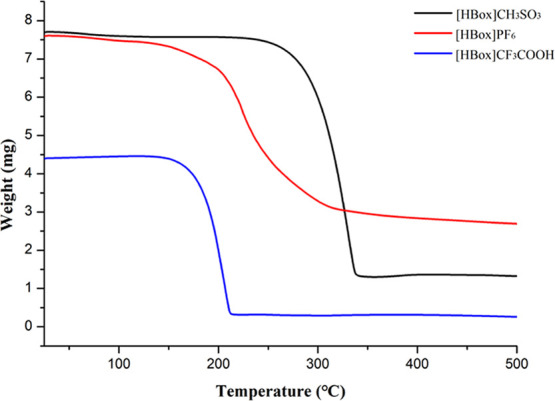

2.1.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis

Thermal analysis is the most well-known technique to determine the thermal stability of ionic liquids.31 According to the thermogravimetric analysis curve in Figure 2, the decomposition temperatures of [HBox]CH3SO3, [HBox]PF6, and [HBox]CF3COOH are about 340, 310, and 215 °C, respectively. Notably, the weight of [HBox]CH3SO3 changes greatly from 7.8 mg to about 1.3 mg. Based on the above experimental results, it can be shown that the ILs have good thermal stability. Additionally, the thermal stability of these compounds may not be related to the benzoxazole ring but is related to the type of anion; the order of thermal stability is [HBox]CH3SO3 > [HBox]PF6 > [HBox]CF3COOH.

Figure 2.

Thermogravimetric analysis curves of the three ionic liquids.

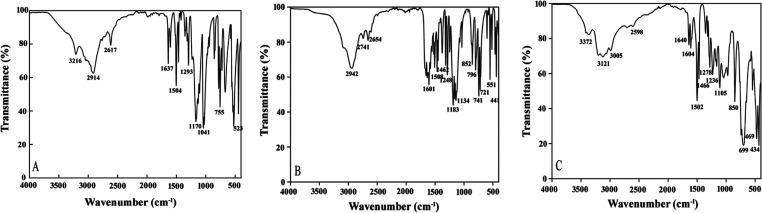

2.1.4. Infrared Spectroscopy Analysis

Infrared spectroscopy analysis can provide a lot of information about the functional groups of compounds, which can help confirm some or all molecular types and structures. Therefore, the main functional groups of the three ionic liquids are observed and investigated in the range of 4000–400 cm–1. When the absorption peak is within 3300–3200 cm–1, the C–H stretching vibration of the three ILs is found on the aromatic ring, and the vibration in the range of 2600–2950 cm–1 is considered as the hydrocarbon stretching vibration on the oxazole ring (see Figure 3). Meanwhile, the absorption peaks within 1640–1630 cm–1 represent the stretching vibration of the C=N double bond. There are absorption peaks at 1600 and 1500 cm–1, which proved the existence of the skeleton vibration of the benzene ring. In addition, when the absorption peaks are within 1300–1000 cm–1, the results indicate that there is a bending vibration of the C–H bond in the benzene ring. Additionally, the absorption peaks at 900–700 cm–1 are proved to be the bending vibration of the benzene ring out of the C–H plane.

Figure 3.

Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra of the three ionic liquids: (A) [HBox]CH3SO3, (B) [HBox]CF3COOH, and (C) [HBox]PF6.

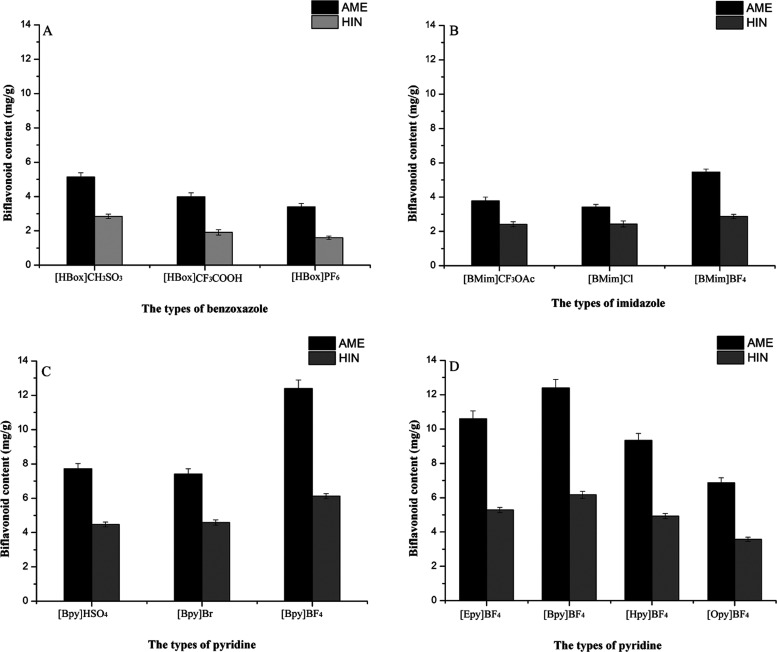

2.2. Screening of ILs

The structure of ILs has a great influence on the extraction effect of the active ingredients from natural products.32 Three different types of ionic liquids are selected, including three benzoxazoles, three imidazoles, and three pyridines, and screened for the extraction of AME and HIN from S. tamariscina (Figure 4A–D). It can be seen from the figure that the order of the influence of the three IL types on their extraction effects is pyridines > benzoxazoles > imidazoles, which may be due to the greater interaction between pyridine ILs and biflavonoids, such as hydrogen bonding effect, electrostatic effect, and van der Waals force.33 Therefore, the extraction capacity of different pyridine ILs will be investigated in detail.

Figure 4.

Effects of different types of ionic liquids on the extraction efficiency of AME and HIN from S.tamariscina: (A) benzoxazoles, (B) imidazoles, (C) different anionic pyridines, and (D) different cationic pyridines.

The anion of ILs has an important influence on the properties of ILs and is considered to be the main factor affecting the extraction rate of the target compounds.34 In this experiment, N-butyl pyridine is selected as the cation and combined with three different types of anions (HSO4–, Br–, and BF4–) separately to investigate the effects on the extraction rate of AME and HIN. Compared with HSO4– and Br– (see Figure 4C), BF4– has a better extraction effect on AME and HIN in S. tamariscina, which may be due to the H bond interaction between BF4– and biflavonoids.35 In addition, the BF4– IL solution can effectively penetrate into the cells, thereby increasing the solubility of the target product. Therefore, BF4– is the best anion and therefore selected to extract AME and HIN from S. tamariscina.

In order to evaluate the influence of pyridine ILs with different cations on the extraction rate of two biflavonoids, BF4– is combined with 4 different cations ([Epy]+, [Bpy]+, [Hpy]+, and [Opy]+) to form different ILs. As shown in Figure 4D, as the alkyl chain length increases from ethyl to butyl, the extraction yields of AME and HIN increased significantly, which may be due to the enhanced hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interaction between ILs and target compounds. When the cation further changes from butyl to octyl, the extraction rate gradually decreased, which may be due to the increase in the viscosity of the ILs, resulting in the weakening of the solvation effect.36 Meanwhile, the molecular weight of the ILs increased, resulting in an increase in steric hindrance, thereby reducing the contact between IL molecules and biflavonoids.37 In conclusion, [Bpy]+ is employed as the appropriate cation for further optimization.

Based on the above experimental results, it can be concluded that the IL with the best extraction effect for AME and HIN in S. tamariscina is [Bpy]BF4, which is selected for further single-factor investigation.

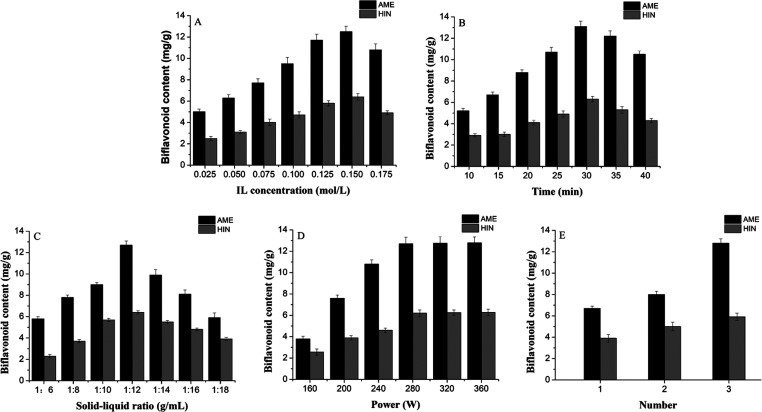

2.3. Single-Factor Experiments

After IL screening, the influence of five parameters, i.e., IL concentration, extraction power, ultrasonic time, solid–liquid ratio, and the number of extractions on the extraction of AME and HIN from S. tamariscina is investigated. As ILs are relatively sticky, Hizaddin et al. found that pyridine ILs are best soluble in a series of ethyl alcohols at the same temperature38 and so we used ethanol to dissolve the ILs.

The concentration of IL is the main factor that affects the extraction rate of active ingredients of natural products. To find the best IL concentration, a series of different ionic liquid concentrations (0.025, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1, 0.125, 0.15, and 0.175 mol/L) are investigated on the extraction effects of AME and HIN. As the IL concentration is in the range of 0.025–0.15 mol/L (see Figure 5A), with the increase of the IL concentration, the extraction rates of AME and HIN gradually increase. When the IL concentration is 0.15 mol/L, the extraction rate reaches a maximum. However, the extraction rate decreases gradually from 0.15 to 0.175 mol/L. This may be because the increase of IL concentration leads to the increase of IL viscosity, thereby decreasing the IL diffusion capacity, which makes it difficult for the IL solution to penetrate plant tissues to fully extract the target compounds.39,40 Therefore, [Bpy]BF4 concentrations of 0.125, 0.15, and 0.175 mol/L are used for the subsequent optimization study of RSM.

Figure 5.

Effects of extraction parameters on AME and HIN yields of S. tamariscina: (A) IL concentration, (B) extraction time, (C) solid to liquid ratio, (D) ultrasound power, and (E) number of extractions.

The extraction of active ingredients from natural products requires a longer time, and too long extraction time produces a lot of impurities. Hence, it is necessary to determine the appropriate extraction time. In this study, the effect of different extraction times (10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, and 40 min) on the extraction rates of AME and HIN is determined. As illustrated in Figure 5B, when the ultrasonic time is in the range of 10–30 min, the extraction rate of the two biflavonoids gradually increases and the extraction rate of biflavonoids reaches a maximum value at 30 min. However, the extraction rate shows a downward trend at 30–40 min. As a shorter extraction time will lead to incomplete extraction of the target product and, after complete extraction, the excess time will increase the energy consumption and cause wastage,41 25, 30, and 35 min are selected for further RSM optimization.

The ratio of solvent to raw medicinal materials is a key factor affecting the extraction efficiency of biflavonoids, and hence, changing the solid–liquid ratio can change the contact area between the solvent and medicinal materials.42 As shown in Figure 5C, when the solid–liquid ratio improved from 1:6 to 1:12 g/mL, the extraction rate of AME increased from 5.85 to 13.10 mg/g and that of HIN increased from 2.12 to 6.12 mg/g. This may be because as the solid–liquid ratio is enhanced, the contact area between the medicinal materials and the solvent expands, thereby promoting energy transfer. However, with the further improvement of the solid–liquid ratio, the extraction efficiency shows a downward trend. If the solid–liquid ratio is too high, a lot of impurities will be produced in the IL solution, which causes the biflavonoid content to decrease significantly.42 In addition, a large amount of solvent will cause unnecessary waste, and less solvent will make the extraction of the targets incomplete. Finally, three solid-to-liquid ratios of 1:10, 1:12, and 1:14 g/mL are selected for the optimization study for evaluating RSM.

The effects of different ultrasonic powers (160, 200, 240, 280, 320, and 360 W) are investigated on the extraction rate of AME and HIN, and other process parameters are as follows: IL concentration is 0.15 mol/L, solid–liquid ratio is 1:12 g/mL, and ultrasonic time is 20 min. As shown in Figure 5D, when the ultrasonic power is increased from 160 to 280 W, the extraction rate of AME increases from 3.79 to 12.10 mg/g and that of HIN increases from 2.13 to 6.11 mg/g. This may be the mechanical action, cavitation performance, and thermal effect produced by ultrasound, which can increase the speed of molecular motion, thereby improving the extraction efficiency.43 Interestingly, as the extraction power is in the range of 280–360 W, the extraction rate of the two diflavonoids hardly changes. Therefore, 280 W is selected as the best ultrasonic power.

The effects of the number of extractions 1, 2, and 3 on the extraction rate of AME and HIN are investigated (see Figure 5E) with IL concentration of 0.15 mol/L, solid–liquid ratio of 1:12 g/mL, and ultrasonic time of 20 min. When the number of extractions is 1 or 2, the extraction effect is not good. As the number of extractions increases, the extraction rate of the two biflavonoids gradually increases. When the extraction number is 3, the extraction yields of the biflavonoids reach maximum values of 11.87 and 5.73 mg/g, respectively. This shows that the increase of the extraction number is beneficial to the significant improvement of the extraction yields and so in the UAILE experiment, we choose to repeat the extraction three times.

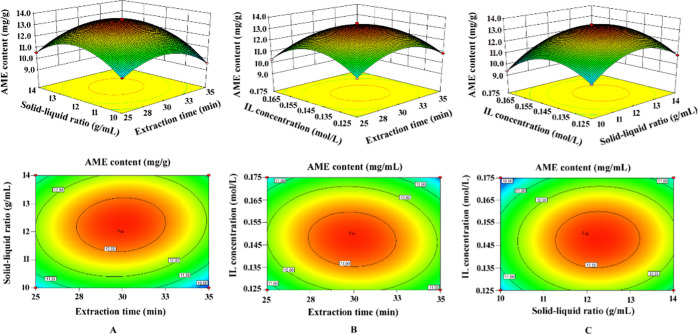

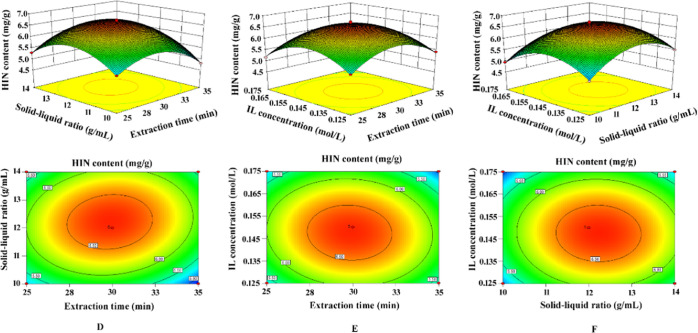

2.4. Analysis of Response Surfaces

On the basis of the analysis results of the single-factor experiment, three factors—extraction time (X1), solid–liquid ratio (X2), and ionic liquid concentration (X3)—are further optimized by the response surface method. Based on the Box–Behnken technology, Design-Expert 8.0.6.1 software was used to carry out the experimental design of three factors, three levels, and five central points (a total of 17 groups). In addition, the extraction rates of AME (Y1) and HIN (Y2) are the response values. The Box–Behnken factor level design is shown in Table S1 of the Supporting Information, and the experimental results are shown in Table S2 of the Supporting Information. The experimental data in Table S2 of the Supporting Information are fitted to obtain the quadratic multiple linear regression equation of the response surface model for extracting AME and HIN from S. tamariscina.

Analysis of variance on the multiple quadratic regression models Y1 and Y2 is performed to determine whether they are statistically significant. It can be seen from the experimental data in Tables 2 and 3 that the p values of the two models is less than 0.0001, indicating that the regression model is significant and the scheme is feasible. The correlation coefficients (R2) of the two models are 0.9981 and 0.9976, respectively, which shows that the model equations have a good linear relationship. Additionally, the lack of fit for AME and HIN is meaningless with p > 0.05. The primary term X2 and the secondary terms X12, X22, and X32 of the model have the most significant impact on the extraction of two targets from S. tamariscina. The above results show that the two models can accurately analyze and predict the extraction rate of AME (Y1) and HIN (Y2) in the IL extract.

Table 2. ANOVA Results of the Regression Equation for Y1.

| source | sum of squares | df | F value | P value | R2 | R2 (adj) | significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| model | 35.44 | 9 | 398.67 | <0.0001 | 0.9981 | 0.9955 | significant |

| X1 | 0.040 | 1 | 4.07 | 0.0834 | |||

| X2 | 1.30 | 1 | 132.10 | <0.0001 | |||

| X3 | 0.76 | 1 | 77.19 | <0.0001 | |||

| X1X2 | 0.22 | 1 | 22.08 | 0.0022 | |||

| X1X3 | 0.12 | 1 | 12.12 | 0.0103 | |||

| X2X3 | 0.031 | 1 | 3.10 | 0.1217 | |||

| X12 | 8.37 | 1 | 847.58 | <0.0001 | |||

| X22 | 11.07 | 1 | 1120.64 | <0.0001 | |||

| X32 | 10.07 | 1 | 1019.28 | <0.0001 | |||

| residual | 0.069 | 7 | |||||

| lack of fit | 0.012 | 3 | 0.28 | 0.8354 | not significant | ||

| pure error | 0.057 | 4 | |||||

| cor total | 35.51 | 16 |

Table 3. ANOVA Results of the Regression Equation for Y2.

| source | sum of squares | df | F value | P value | R2 | R2 (adj) | significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| model | 8.19 | 9 | 327.49 | <0.0001 | 0.9976 | 0.9946 | significant |

| X1 | 0.030 | 1 | 10.68 | 0.0137 | |||

| X2 | 0.22 | 1 | 79.82 | <0.0001 | |||

| X3 | 0.16 | 1 | 58.84 | 0.0001 | |||

| X1X2 | 0.076 | 1 | 27.49 | 0.0012 | |||

| X1X3 | 0.022 | 1 | 7.89 | 0.0262 | |||

| X2X3 | 6.728 × 10–3 | 1 | 2.42 | 0.1638 | |||

| X12 | 2.23 | 1 | 800.98 | <0.0001 | |||

| X22 | 2.40 | 1 | 863.73 | <0.0001 | |||

| X32 | 2.24 | 1 | 805.11 | <0.0001 | |||

| residual | 0.019 | 7 | |||||

| lack of fit | 8.206 × 10–3 | 3 | 0.97 | 0.4887 | not significant | ||

| pure error | 0.011 | 4 | |||||

| cor total | 8.21 | 16 |

The three-dimensional response surface and contour lines (Figures 6 and 7) reflect the influence of the relationship between variables on the extraction of the target compound and are drawn using Design-Expert 8.0.6.1 software. The ordinate represents the content of AME or HIN, and the abscissa represents the variable of any two parameters. Figures 6 and 7 show that the three contour plots of the two biflavonoids are elliptical, and the response surface plots are all convex figures opening downwards, indicating that the interaction of three factors has a significant impact on the extraction rates of AME and HIN. The optimal extraction conditions of the biflavonoids obtained by the quadratic regression equation are as follows: extraction time, 29.83 min; solid–liquid ratio, 1:12.2 g/mL; and IL concentration, 0.148 mol/L. Under these extraction conditions, the theoretical outputs of AME and HIN are 13.57 and 6.71 mg/g, respectively. In the actual situation, the extraction process was adjusted to an extraction time of 30 min, a solid–liquid ratio of 1:12 g/mL, and an IL concentration of 0.15 mol/L. The best yields of AME and HIN are 13.51 and 6.74 mg/g, respectively, which are basically consistent with the predicted values.

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional surface and contour map of the interaction between each of the two factors in response surface analysis on the yield of AME. Interactions between (A) extraction time and solid–liquid ratio, (B) extraction time and IL concentration, and (C) solid–liquid ratio and IL concentration.

Figure 7.

Three-dimensional surface and contour map of the interaction between each of the two factors in response surface analysis on the yield of HIN. Interactions between (D) extraction time and solid–liquid ratio, (E) extraction time and IL concentration, (F) solid–liquid ratio and IL concentration.

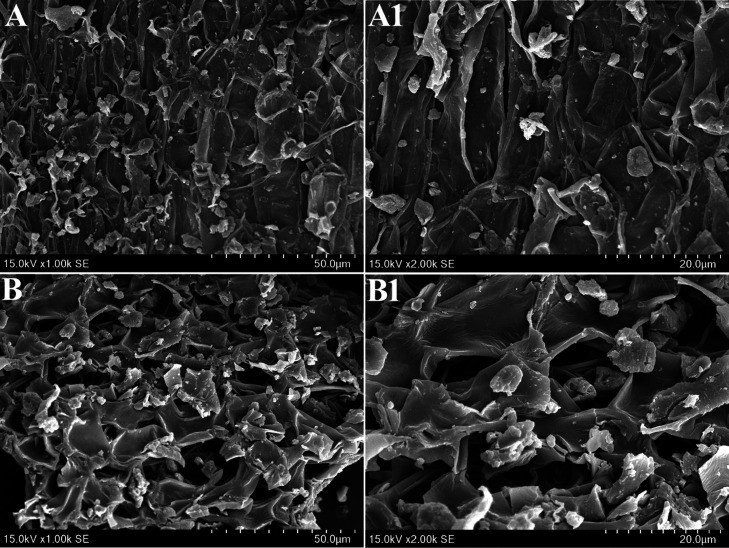

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

To analyze the micron surface features of the raw materials before and after using UAILE, the surface morphology features of S. tamariscina are obtained under 1000 and 2000 magnification using the scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The SEM results of Figure 8A,A1 shows that the untreated S. tamariscina distinctly shows an intact cell structure, thick cell walls, and clear boundaries between different tissues. On the contrary, the cell structure of S. tamariscina is almost completely destroyed by UAILE technology in Figure 8B,B1, which facilitates the dissolution of biflavonoids from the cells into the IL solution. This may be due to the violent vibration of the ultrasound, which has a very strong destructive effect on natural products, thereby deforming the cell tissue, destroying the structure of the cell wall, and accelerating the permeability of the solvent.44 The above results indicate that the UAILE technology may cause a difference in the surface morphology of S. tamariscina before and after extraction.

Figure 8.

SEM images of the IL extract from (A, A1) S. tamariscina raw materials and (B, B1) treated samples by UAILE observed under 1000 and 2000 magnification, respectively.

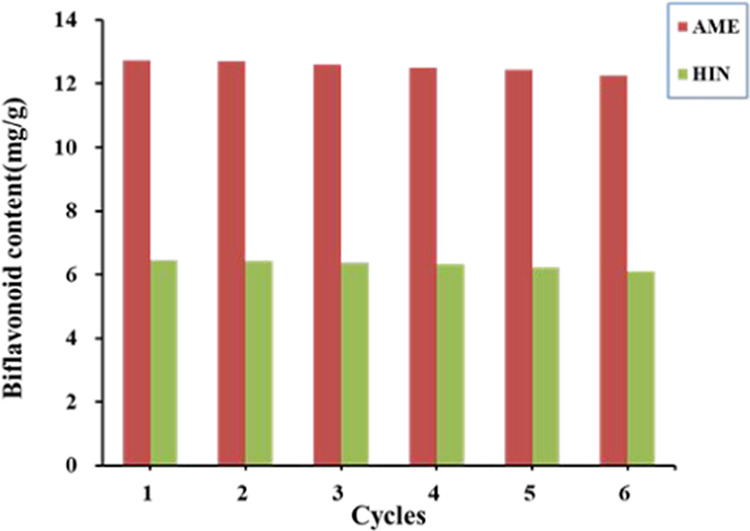

2.6. Performance of Recovered [Bpy]BF4

After extraction, [Bpy]BF4 is recovered and used to extract AME and HIN in the next batch of S. tamariscina. First, the samples are dissolved in 100 mL of hot water and are extracted three times with an equal volume of ethyl acetate. Then, the extracted IL aqueous solution is combined, concentrated under reduced pressure, and dried to a constant weight under vacuum at 60 °C to obtain [Bpy]BF4.

Under the optimal extraction conditions, the effects of the recovered [Bpy]BF4 on the extraction efficiency of AME and HIN in S. tamariscina are studied in detail. As indicated in Figure 9, the extraction rates of AME and HIN decreased slightly with the increase in the number of repeated operations, and the extraction rates of the two biflavonoids still reached about 90% of the satisfactory extraction yields in the sixth cycle. The results show that the recovered [Bpy]BF4 can be repeated six times to extract AME and HIN from S. tamariscina. Therefore, it can be proved that [Bpy]BF4 is an ideal solvent to extract the two biflavonoids from S. tamariscina, with obvious advantages such as high efficiency and good recyclability.

Figure 9.

Performance of the recovered [Bpy]BF4 on the yields of AME and HIN.

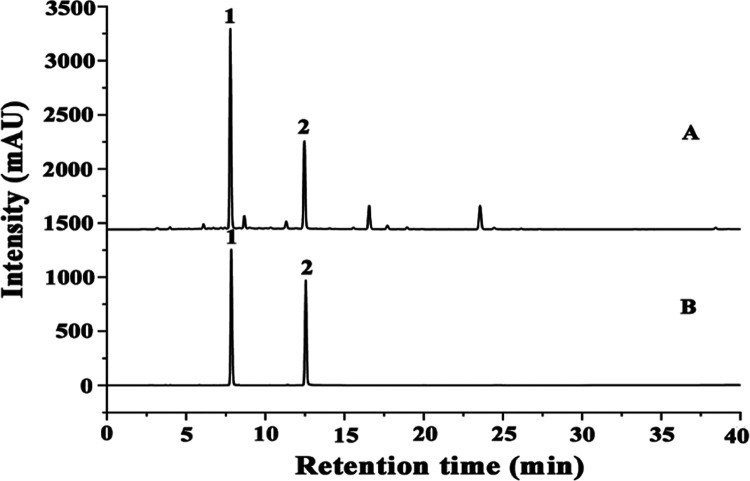

2.7. Method Validation

The extract of S. tamariscina is analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to establish a reliable and precise quantitative analysis method for AME and HIN. The methodological investigation of HPLC is further carried out, including precision, repeatability, stability, and recovery.

Based on the peak area values of different concentrations of AME and HIN in the HPLC diagrams, the linear relationship of the two biflavonoids in the IL extract is investigated for the first time, and their linear regression equation is established. The regression equation of the AME reference substance is Y = 34688X + 5.4043 (R2 = 0.9995), which shows that AME has a good linear relationship with the peak areas in the range of 0.041–0.244 mg/mL. The regression equation of the HIN reference substance is Y = 36860X + 75.613 (R2 = 0.9996), indicating that HIN has a good linear relationship with the peak areas within 0.040–0.243 mg/mL (see Table 4). The results from the tables confirm that the biflavonoids show good linearity and their correlation coefficients (R2) are both greater than 0.999. Additionally, LOQs (S/N = 10) and LODs (S/N = 3) for AME and HIN of S. tamariscina extracts are less than 0.286 and 0.081 μg/mL, respectively.

Table 4. Method Validation for the Two Standard Compoundsa.

| precision (n = 6)b |

stability (n = 5)b |

repeatability (n = 6)b |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| analyte | calibration curve | R2 | LOD (μg/mL) | LOQ (μg/mL) | retention time | peak area | retention time | peak area | retention time | peak area | recovery (n = 6)b |

| AME | Y = 34688X + 5.4043 | 0.9995 | 0.064 | 0.243 | 0.206 | 0.121 | 0.756 | 0.601 | 0.047 | 0.120 | 1.59 |

| HIN | Y = 36860X + 75.613 | 0.9996 | 0.081 | 0.286 | 0.177 | 0.115 | 1.143 | 1.803 | 0.035 | 1.407 | 1.08 |

LOD, limit of detection (S/N = 3); LOQ, limit of quantification (S/N = 10).

Intraday precision, interday precision, stability, repeatability, and recovery are expressed as relative standard deviation (RSD) (%).

Under the optimal extraction conditions, stability, precision, repeatability, and recovery of the IL extracts are assessed in detail. The precision of peak area and retention time is measured to repeat the same analyte six times according to the chromatographic conditions in Section 4.5, and their relative standard deviations (RSDs) are less than 2%, which shows good accuracy. The stability is explored based on the determination of each analyte at 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12 h at 25 °C, and the RSD of the peak area and retention time is less than 2% for the two bioflavonoids, which indicates that AME and HIN are stable in the IL extract at 12 h. The repeatability is determined by weighing the same sample six times to prepare the extract according to sample preparation in Section 4.4, and the results illustrate that the extraction yields of the two biflavonoids have good repeatability with RSDs < 2%. The recoveries for AME and HIN are evaluated by adding the same target products with known content into 3.1 g of raw materials (n = 6), respectively, and it can be seen from Table 4 that the established methods have acceptable recoveries for AME and HIN.

The application of this method makes the components basically reach the baseline separation, and the retention time is appropriate, the resolution of each peak is high, the peak shape is good, and the methodological investigation is reasonable. Therefore, this method is suitable for the determination of AME and HIN in S. tamariscina.

3. Conclusions

In this study, three benzoxazole ILs with novel structures, i.e., [HBox]CH3SO3, [HBox]PF6, and [HBox]CF3COOH, are synthesized for the first time using benzoxazole as the raw material by a one-step synthesis method. The structures of the synthesized ionic liquids are identified through elemental analysis, NMR spectroscopy, and infrared spectroscopy. The experimental results of thermogravimetric analysis prove that the synthesized ILs have good thermal stability.

The effects of three types of ILs on the extraction of AME and HIN from S.tamariscina are investigated, and the IL with the best extraction effect is [Bpy]BF4. The optimal process parameters are as follows: IL concentration, 0.15 mol/L; ultrasonic time, 30 min; solid to liquid ratio, 1:12 g/mL; ultrasonic power, 280 W; number of extractions, three; and extraction rates of AME and HIN, 13.51 and 6.74 mg/g, respectively. The [Bpy]BF4 can be recycled at least six times, and the extraction rates of AME and HIN dropped only slightly. Generally speaking, UAILE technology for extracting AME and HIN fromS. tamariscina is a suitable, green, and efficient method, which helps to lay the foundation for the research of its medicinal value.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

S. tamariscina (batch no: 20180325) is purchased from Zunyi traditional Chinese medicine market, Guizhou, and is identified as the dried whole grass of S. tamariscina by Prof. Yujin Zhang at the Department of Pharmacy of Zunyi Medical University. The benzoxazole ionic liquid is prepared in the laboratory, and the imidazole and pyridine ionic liquids are bought from Aolike New Material Technology Co., Ltd. (Qingdao, China; see Table S3 of Supporting Information for the analysis test design). Amentoflavone (AME) and hinokiflavone (HIN) standards (>98% purity) are provided from Zeye Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). Chromatographic grade acetonitrile and other analytical grade reagents are provided by Taoyuan Chemical Reagent Company (Zunyi, China). Three benzoxazole ILs, namely, benzoxazole methanesulfonate ([HBox]CH3SO3), benzoxazole hexafluorophosphate ([HBox]PF6), and benzoxazole trifluoroacetate ([HBox]CF3COOH), are synthesized by one-step synthesis.

4.2. Preparation of Benzoxazole Ionic Liquids

Benzoxazole (0.1 mol) is dissolved in 50 mL of absolute ethanol, placed in a three-neck flask, and cooled to 5 °C. Then, the sample is mixed well with 20 mL of 0.1 mol methanesulfonic acid and reacted at room temperature for 4 h under the protection of N2. After the reaction, the crude product is washed with ethyl acetate (20 mL × 3), recrystallized in absolute ethanol, and further dried under reduced pressure to obtain orange-red crystals (melting point, 104 °C; yield, 75.6%).

Benzoxazole (0.1 mol) is placed in a three-neck flask and dissolved in 50 mL of absolute ethanol at 5 °C. After the sample is mixed well with 20 mL of 0.1 mol trifluoroacetic acid, the mixture is reacted at room temperature for 2 h under the protection of N2. Then, the obtained crude product is washed with diethyl ether (10 mL × 3), recrystallized in ethyl acetate, and further dried under reduced pressure to obtain reddish crystals (melting point,108 °C; yield, 80.4%).

Benzoxazole (0.1 mol) is dissolved in 50 mL of absolute ethanol, placed in a three-neck flask, and cooled to 5 °C. Then, the sample is mixed well with 20 mL of 0.1 mol sodium hexafluorophosphate and reacted at room temperature for 4 h under the protection of N2. After the synthesized crude product is washed with ethyl acetate (20 mL × 3), the IL is recrystallized in absolute ethanol, and further dried under reduced pressure to obtain sandy and thick liquids (yield, 76.7%).

4.3. Structural Characterization of ILs

An element analyzer (model: VARIOEL) is employed for the elemental analysis of the synthetic ILs, including carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and sulfur. Meanwhile, the functional group characterizations of the ILs are performed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (model: Nicolot is50), and the samples are prepared by KBr compression; the wavenumber range is 4000–400 cm–1. The thermal stability of ILs is investigated using a thermogravimetry differential thermal analyzer (model: 1600LF). The NMR hydrogen spectrum and carbon spectrum of ILs are detected by an NMR instrument (model: Agilent-400 MHz DDZ), and the sample is dissolved in DMSO-d6.

4.4. Preparation of Samples

According to the process design scheme, the dried S. tamariscina is crushed and sieved (100 mesh, 21–73 μm), and 5.0 g of the powder is weighed, placed in a 100 mL conical flask, and extracted by the UAILE technique in a ultrasonic device (F-100S, Fuyang Technology Group Co. Ltd., Shenzhen, China). In short, the plants are mixed with a fixed volume of IL solution, which is dissolved using a pre-established volume of ethanol, and reacted at a certain ultrasonic power and time.45 After the reaction, the extract is obtained by filtration and concentrated under reduced pressure.

4.5. Determination of Biflavonoid Content

The content of biflavonoids of the S. tamariscina extract is measured using a 1260 high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Agilent, American). The determined chromatographic conditions are as follows: a Megres reversed-phase C18 chromatographic column (5 μm, 250×4.6 mm, Hanbang, China), a mobile phase of acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid solution using gradient elution (see Table S4 of Supporting Information for the analysis test design), a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min, a column temperature of 25 °C, a detection wavelength of 330 nm, and an injection volume of 10 μL. The calibration curve equations for the two biflavonoids are YA = 34688X + 5.4043 (R2 = 0.9995) for AME (0.041–0.244 mg/mL) and YB = 36860X + 75.613 (R2 = 0.9996) for HIN (0.040∼0.243 mg/mL). Each peak of the samples in the HPLC profile (Figure 10) is identified by the retention times of AME and HIN, respectively. Thus, the content of the two biflavonoids in the S. tamariscina extract is obtained by the formula

where C is the concentration of biflavonoids and m is the mass of the medicinal materials.

Figure 10.

HPLC chromatograms of the (A) S. tamariscina extracts and (B) standard mixture solution (1: AME, 2: HIN).

4.6. Process Optimization

4.6.1. Single-Factor Experiments

To investigate and analyze experimental results on the biflavonoids of the extract from S. Tamariscina under UAILE, IL concentration (0.025, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1, 0.125, 0.15, and 0.175 mol/L), ultrasonic power (160, 200, 240, 280, 320, and 360 W), ultrasound time (10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, and 40 min), solvent–material ratio (1:6, 1:8, 1:10, 1:12, 1:14, 1:16, and 1:18 g/mL), and the number of extractions (1, 2, and 3 times) are evaluated as process parameters.

4.6.2. RSM Design

Based on the experimental results of the single-factor experiments, three process parameters (extraction time, solid–liquid ratio, and IL concentration) have a significant impact on the extraction rate of each biflavonoid and are further investigated by RSM technology. According to the Box–Behnken experimental design (three factors, three levels, and five5 central points), 17 groups of random trials are designed and carried out. The quadratic polynomial model is used to evaluate the relationship between the response value (biflavonoid extraction rate) and the three variables (see Table S2 of Supporting Information for the analysis test design), which is given by the following equation

| 1 |

where Y is the extraction rate and X1, X2, and X3 are the three factors investigated.

4.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy

The microstructure of S. tamariscina samples before and after extraction is measured by a Quanta 200 scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hillsboro). To enable the electrical conductivity, a thin layer of gold (5–10 nm; 10 mA; 30 s) is plated on the surface of the sample by a KYKY SBC-12 sputter coater (Beijing, China) at room temperature.

4.8. Recovery of [Bpy]BF4

Based on the extraction optimization, two biflavonoids from the S. tamariscina extract are isolated by liquid–liquid extraction method, and the recovered IL is continued to be used to extract the target samples from the plant in the subsequent extraction procedure. In brief, the IL extract is dissolved in water deionized 30 times. Next, two biflavonoids and [Bpy]BF4 are extracted with ethyl acetate as the insoluble organic reagent (Vethyl acetate/Vextract = 3:1, v/v). The content of the two biflavonoids is measured by the HPLC method as given in Section 3.3. In addition, the IL that was distributed in the sublayer was concentrated to remove deionized water, dried under vacuum, and reused to investigate the extraction capability of target compounds. No obvious absorbance of the two biflavonoids is detected at 330 nm in the recycled [Bpy]BF4 solution, indicating that AME and HIN are successfully separated.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Science Foundation of China 81302639, the Science and Technology Foundation of Guizhou Province of China (QKHPTRC[2019]5657, QKHZC[2019]2953), and the Program for Excellent Young Talents of Zunyi Medical University (15zy-004).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c04723.

Factors and levels of the Box–Behnken design; Box–Behnken experimental results; chemical structures of the ionic liquids; and HPLC gradient elution program (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Liu R.; Zou H.; Zou Z.-X.; Cheng F.; Yu X.; Xu P.-S.; Li X.-M.; Li D.; Xu K.-P.; Tan G.-S. Two new anthraquinone derivatives and one new triarylbenzophenone analog from Selaginella tamariscina. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 21, 1–6. 10.1080/14786419.2018.1452008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G.-g.; Jing Y.; Zhang H.-m.; Ma E.-l.; Guan J.; Xue F.-n.; Liu H.-x.; Sun X.-y. Isolation and cytotoxic activity of selaginellin derivatives and biflavonoids from Selaginella tamariscina. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 390–392. 10.1055/s-0031-1298175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung Y.-J.; Lee E. H.; Lee C. G.; Rhee K.-J.; Jung W.-S.; Choi Y.; Pan C.-H.; Kang K. AKR1B10-inhibitory Selaginella tamariscina extract and amentoflavone decrease the growth of A549 human lung cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 202, 78–84. 10.1016/j.jep.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Wang Y.-L.; Gao D.; Cai L.; Yang Y.-Y.; Hu Y.-J.; Yang F.-Q.; Chen H.; Xia Z.-N. Comparing coagulation activity of Selaginella tamariscina before and after stir-frying process and determining the possible active constituents based on compositional variation. Pharm. Biol. 2018, 56, 67–75. 10.1080/13880209.2017.1421673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X.-k.; Wang W.-w.; Zhang L.; Su C.-f.; Wu Y.-y.; Ke Y.-y.; Hou Q.-w.; Liu Z.-y.; Gao A.-s.; Feng W.-s. Antihyperlipidaemic and antioxidant effect of the total flavonoids in Selaginella tamariscina (Beauv.) Spring in diabetic mice. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2013, 65, 757–766. 10.1111/jphp.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.; Wu Y.; Bi R.; Liu S.; Liu Z.; Liu Z.; Song F.; Shi Y. Therapeutic effects of Selaginella tamariscina on the model of acute gout with hyperuricemia in rats based on metabolomics analysis. Chin. J. Chem. 2017, 35, 1117–1124. 10.1002/cjoc.201600810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B. T.; Hung N. D.; Lee J. H.; Min B. S.; Woo M. H. Lignan derivatives from Selaginella tamariscina and their nitric oxide inhibitory effects in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 524–529. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z.; Xin T.; Bartels D.; Li Y.; Gu W.; Yao H.; Liu S.; Yu H.; Pu X.; Zhou J.; Xu J.; Xi C.; Lei H.; Song J.; Chen S. Genome analysis of the ancient tracheophyte Selaginella tamariscina reveals evolutionary features relevant to the acquisition of desiccation tolerance. Mol. Plant 2018, 11, 983–994. 10.1016/j.molp.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H.-J.; Kim M.-M. Amentoflavone induces autophagy and modulates p53. Cell J. 2019, 21, 27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen F.; Chen Y.; Chen L.; Qin J.; Li Z.; Xu J. Amentoflavone promotes apoptosis in non-small-cell lung cancer by modulating cancerous inhibitor of PP2A. Anat. Rec. 2019, 302, 2201–2210. 10.1002/ar.24229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W.; Liu C.; Liu F.; Liu Z.; Lai G.; Yi J. Hinokiflavone induces apoptosis and inhibits migration of breast cancer cells via EMT signalling pathway. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2020, 38, 249–256. 10.1002/cbf.3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Feng X.; Li L.; Song K.; Zhang L. Preparation and antitumor evaluation of hinokiflavone hybrid micelles with mitochondria targeted for lung adenocarcinoma treatment. Drug Delivery 2020, 27, 565–574. 10.1080/10717544.2020.1748760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J.; Zhao R.; Ye T.; Yang S.; Li Y.; Yang F.; Wang G.; Xie Y.; Li Q. Antitumor activity in colorectal cancer induced by hinokiflavone. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 34, 1571–1580. 10.1111/jgh.14581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.; Yu S. Amentoflavone suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma by repressing hexokinase 2 expression through inhibiting JAK2/STAT3 signaling. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 107, 243–253. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.; Zhang Y.; Luo Y.; Xu B.; Yao Y.; Deng Y.; Yang F.; Ye T.; Wang G.; Cheng Z.; Zheng Y.; Xie Y. Hinokiflavone induces apoptosis in melanoma cells through the ROS-mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and impairs cell migration and invasion. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 103, 101–110. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.02.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim S. Y.; Lee S. G.; Lee M. Biflavonoids isolated from Selaginella tamariscina and their anti-inflammatory activities via ERK 1/2 signaling. Molecules 2018, 23, 523–533. 10.3390/molecules23040926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Andrés M.; Andres-Iglesias C.; Garcia-Serna J. Production of molecular weight fractionated hemicelluloses hydrolyzates from spent coffee grounds combining hydrothermal extraction and a multistep ultrafiltration/diafiltration. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 292, 12–21. 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.121940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubas A. L. V.; Machado M. M.; Bianchet R. T.; Hermann K. A. D.; Bork J. A.; Debacher N. A.; Lins E. F.; Maraschin M.; Coelho D. S.; Moecke E. H. S. Oil extraction from spent coffee grounds assisted by non-thermal plasma. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 250, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tungmunnithum D.; Drouet S.; Kabra A.; Hano C. Enrichment in antioxidant flavonoids of stamen extracts from Nymphaea lotus L. using ultrasonic-assisted extraction and macroporous resin adsorption. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 24–35. 10.3390/antiox9070576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu G. H.; Li T. H.; Zhao Y. F.; Chen F. S. Effects of high hydrostatic pressure combined with heat treatment on the antigenicity and conformation of beta-conglycinin. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 246, 1065–1072. 10.1007/s00217-020-03472-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khiratkar A. G.; Balinge K. R.; Patle D. S.; Krishnamurthy M.; Cheralathan K. K.; Bhagat P. R. Transesterification of castor oil using benzimidazolium based bronsted acid ionic liquid catalyst. Fuel 2018, 231, 458–467. 10.1016/j.fuel.2018.05.127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal B.; Ghosh S.; Basu B. Task-specific properties and prospects of ionic liquids in cross-coupling reactions. Top. Curr. Chem. 2019, 377, 252–263. 10.1007/s41061-019-0255-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji S.; Wang Y. J.; Su Z. Y.; He D. D.; Du Y.; Guo M. Z.; Yang D. Z.; Tang D. Q. Ionic liquids-ultrasound based efficient extraction of flavonoid glycosides and triterpenoid saponins from licorice. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 13989–13996. 10.1039/C8RA01056K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y.; Li D.; Ma X.; Jiang F.; He Q.; Qiu S.; Li Y.; Wang G. Ionic liquid(-)ultrasound-based extraction of biflavonoids from Selaginella helvetica and investigation of their antioxidant activity. Molecules 2018, 23, 112–124. 10.3390/molecules23123284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S.; Lindeman S.; Tran C. D. Chiral ionic liquids: synthesis, properties, and enantiomeric recognition. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 2576–2591. 10.1021/jo702368t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh G.; Kamboj R.; Mithu V. S.; Chauhan V.; Kaur T.; Kaur G.; Singh S.; Kang T. S. Nicotine-based surface active ionic liquids: synthesis, self-assembly and cytotoxicity studies. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 496, 278–289. 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudries H.; Nabet N.; Chougui N.; Souagui S.; Loupassaki S.; Madani K.; Dimitrov K. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of antioxidant phenolics from capparis spinosa flower buds and LC-MS analysis. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 13, 2241–2252. 10.1007/s11694-019-00144-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira T. M. S.; dos Santos J. A. S.; Modesto L. A.; Souza L. S.; dos Santos M. P. V.; Bezerra D. G.; de Paula J. A. M. An eco-friendly method for extraction and quantification of flavonoids in dysphania ambrosioides. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2019, 29, 266–270. 10.1016/j.bjp.2019.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dadi D. W.; Emire S. A.; Hagos A. D.; Eun J. B. Effect of ultrasound-assisted extraction of moringa stenopetala leaves on bioactive compounds and their antioxidant activity. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2019, 57, 77–86. 10.17113/ftb.57.01.19.5877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kou X. R.; Ke Y. Q.; Wang X. Q.; Rahman M. R. T.; Xie Y. Z.; Chen S. W.; Wang H. X. Simultaneous extraction of hydrophobic and hydrophilic bioactive compounds from ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Food Chem. 2018, 257, 223–229. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.02.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahnavaz Z.; Zaharani L.; Khaligh N. G.; Mihankhah T.; Johan M. R. Synthesis, characterisation, and determination of physical properties of new two-protonic acid ionic liquid and its catalytic application in the esterification. Aust. J. Chem. 2020, 20153 10.1071/CH20153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Sun C.; Yang J.; Ma X.; Jiang Y.; Qiu S.; Wang G. Ionic liquid-microwave-based extraction of biflavonoids from Selaginella sinensis. Molecules. 2019, 24, 8–20. 10.3390/molecules24132507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji S.; Wang Y.; Gao S.; Shao X.; Cui W.; Du Y.; Guo M.; Tang D. Highly efficient and selective extraction of minor bioactive natural products using pure ionic liquids: application to prenylated flavonoids in licorice. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 80, 352–360. 10.1016/j.jiec.2019.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Qian Y.; Tian Y. J.; Yuan S. M.; Wei W.; Wang G. Optimization of ionic liquid-assisted extraction of biflavonoids from Selaginella doederleinii and evaluation of its antioxidant and antitumor activity. Molecules 2017, 22, 45–56. 10.3390/molecules22040586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji S.; Wang Y. J.; Gao S. K.; Shao X.; Cui W.; Du Y.; Guo M. Z.; Tang D. Q. Highly efficient and selective extraction of minor bioactive natural products using pure ionic liquids: application to prenylated flavonoids in licorice. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 80, 352–360. 10.1016/j.jiec.2019.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F.; Zhang X.; Zhang Q.; Du X.; Yang L.; Zu Y.; Yang F. Simultaneous synergistic microwave-ultrasonic extraction and hydrolysis for preparation of trans-resveratrol in tree peony seed oil-extracted residues using imidazolium-based ionic liquid. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 94, 266–280. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.08.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K.; Li M.; Wen X.; Chen X.; He Z.; Ni Y. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench) polysaccharides based on response surface methodology and antioxidant activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 114, 1056–1063. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.03.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hizaddin H. F.; Hadj-Kali M. K.; Ramalingam A.; Hashim M. A. Extraction of nitrogen compounds from diesel fuel using imidazolium- and pyridinium-based ionic liquids: experiments, COSMO-RS prediction and NRTL correlation. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2015, 405, 55–67. 10.1016/j.fluid.2015.07.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- López C. J.; Caleja C.; Prieto M. A.; Barreiro M. F.; Barros L.; Ferreira I. C. F. R. Optimization and comparison of heat and ultrasound assisted extraction techniques to obtain anthocyanin compounds from Arbutus unedo L. Fruits. Food Chem. 2018, 264, 81–91. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.04.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y.; Li D.; Ma X.; Jiang F.; He Q.; Qiu S.; Li Y.; Wang G. Ionic liquid-ultrasound-based extraction of biflavonoids from Selaginella helvetica and investigation of their antioxidant activity. Molecules 2018, 23, 62–74. 10.3390/molecules23123284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; Niu Y.; Liu J.; Shi M.; Xu R.; Kang W. Efficient extraction of anti-inflammatory active ingredients from Schefflera octophylla leaves using ionic liquid-based ultrasonic-assisted extraction coupled with HPLC. Molecules 2019, 24, 18–29. 10.3390/molecules25010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M.; Zhang J.; Liu C.; Cui Y.; Li C.; Liu Z.; Kang W. Ionic liquid-based ultrasonic-assisted extraction to analyze seven compounds in psoralea fructus coupled with HPLC. Molecules 2019, 24, 42–52. 10.3390/molecules24091699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q.; Wu S.; Wang C.; Yi Y.; Zhou W.; Wang H.; Li F.; Tan Z. Ultrasonic-assisted extraction of sinomenine from Sinomenium acutum using magnetic ionic liquids coupled with further purification by reversed micellar extraction. Process Biochem. 2017, 58, 282–288. 10.1016/j.procbio.2017.04.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. M.; Wei H. Z.; Zhao Y.; Sun W. J.; Sun C. L. The optimization, kinetics and mechanism of m-cresol degradation via catalytic wet peroxide oxidation with sludge-derived carbon catalyst. J. Hazard Mater. 2017, 326, 36–46. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yohannes A.; Zhang B.; Dong B.; Yao S. Ultrasonic extraction of tropane alkaloids from Radix physochlainae using as extractant an ionic liquid with similar structure. Molecules 2019, 24, 52–63. 10.3390/molecules24162897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.