Short abstract

Background

Sleep is essential for health and recovery. Hospital stays may affect adolescents’ sleep quality negatively as routines in the ward are not adapted for adolescents’ developmental status or sleep habits. The aims with this study were to (a) explore and describe how adolescents experience sleep in the family-centered pediatric ward, (b) explore and describe how adolescents experience the presence or absence of a parent during the hospital stay, and (c) identify circumstances that the adolescents describe as influential of their sleep in the pediatric wards.

Methods

This is a qualitative interview study employing thematic analysis with an inductive and exploratory approach. Sixteen adolescents aged between 13 and 17 years participated in the study.

Results

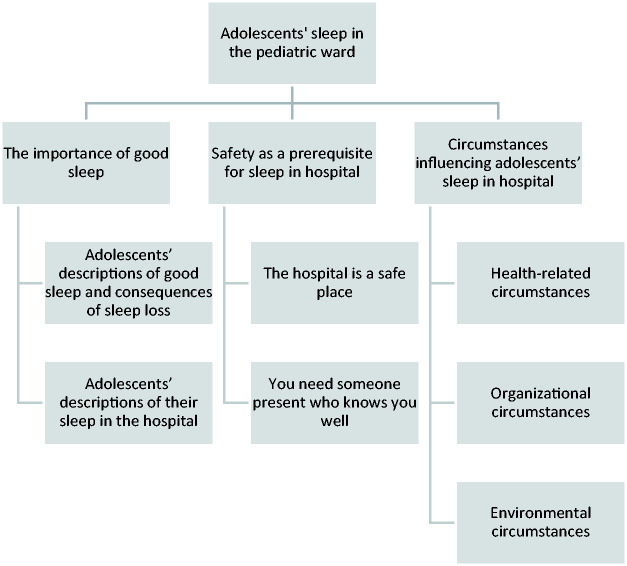

Three themes were found: the importance of good sleep, safety as a prerequisite for sleep in hospital, and circumstances influencing adolescents’ sleep in hospital.

Conclusion

The adolescents described their sleep at the pediatric ward positively, but mentioned disturbing factors associated with pain, nightly check-ups, noises, and inactivity. Parental presence was perceived as very positive both during the night and the day.

Keywords: adolescents, family-centered care, pediatrics, qualitative, sleep

Introduction

In general, adolescents are a healthy population group. However, every year more than 20,000 adolescents (4% of 15–19 years old) are admitted to hospitals in Sweden, due to a variety of diagnoses with varying severity. The mean admission time is 3.5 days (Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare], 2017). Adolescents, just like “every human being below the age of 18 years old,” have the right to the best health care possible and the child’s interests must be of primary concern according to the Convention of the Rights of the Child (United Nations, 1989). Consequently, hospitalized adolescents should be guaranteed to fully enjoy their right to health and development as stated in the Convention.

Sleep changes over the life course, both in terms of length and timing. Sufficient sleep, defined as sleeping at least 85% of the total time in bed, falling asleep in 30 minutes or less, no more than one nocturnal awakening, and being awake for 20 minutes or less after initially falling asleep (Ohayon et al., 2017), is fundamental for health and recovery (Owens & Weiss, 2017; Shochat, Cohen-Zion, & Tzischinsky, 2014). Specifically, sleep is important for healing, both in terms of tissue repair and cellular immune function (Pulak & Jensen, 2016), whereas insufficient sleep is associated with negative outcomes, such as increased stress responsivity, mood swings, decreased cognition, and less ability of performing and decision-making (Jansson-Frojmark, Norell-Clarke, & Linton, 2016; Medic, Wille, & Hemels, 2017; Owens & Weiss, 2017; Shochat et al., 2014). Adolescents’ normal sleep behavior differs from children’s and adults’ in terms of preferred timing and length due to a shift delay in circadian rhythm and a developmentally based slowing of the sleep-drive (Owens & Weiss, 2017). Further, there are other factors associated with adolescence such as intensive evening use of electronic media and increased demands from school, meaning a more time-consuming homework load that also may impact bedtimes and sleep (Garmy & Ward, 2017; Owens & Weiss, 2017).

Sleep deprivation in patients admitted to hospital has been reported as a common problem in both adults (Beltrami et al., 2015; Kamdar, Needham, & Collop, 2012; Pulak & Jensen, 2016) and children (Clift, Dampier, & Timmons, 2007; Kudchadkar, Aljohani, & Punjabi, 2014; Lee, Narendran, Tomfohr-Madsen, & Schulte, 2017). However, there is little reported on adolescents’ sleep in hospital and the findings are contradictory. An Australian study (Herbert et al., 2014) did not find any differences between adolescent’s sleep duration in pediatric wards, compared to their sleep at home before admission. Contrary to this finding, adolescents in shared patient rooms at pediatric wards in the United Kingdom described how their sleep was frequently interrupted (Clift et al., 2007), and adolescents in the United States have reported more frequent awakenings and later bedtimes in hospital than at home (Meltzer, Davis, & Mindell, 2012).

Adolescents have reported better satisfaction with being admitted to pediatric wards than adult wards (Sadeghi, Abdeyazdan, Motaghi, Rad, & Torkan, 2012). However, previous studies report that pediatric wards have a lack of specific facilities and activities for adolescents, as the wards cater primarily for younger children and infants, which leads to passivity and boredom (Clift et al., 2007; Massimo, Rossoni, Mattei, Bonassi, & Caprino, 2016). Similarly, being admitted to adult wards with older people comes with its own issues. Dean and Black (2015) describe how adolescents felt lonely, scared, and frightened in adult wards. Partly because of the unfamiliar environment but also because of adult patients who did not respect the adolescents’ personal space and sometimes behaved disorientedly. Moreover, adolescents described a lack of competence among the nursing staff in managing professional relationships with adolescents, leading to patronizing staff treating adolescents like small children (Dean & Black, 2015). In another study, adolescents at adult wards expressed feelings of being out of place and that they missed the company of other young people (Olsen, Jensen, Larsen, & Sorensen, 2016).

Rather than sharing a hospital room with a stranger and only meeting staff, family-centered care is a special approach of care for children and their families in pediatric wards, ensuring that all family members are seen as care takers (Shields, Pratt, & Hunter, 2006). This includes accommodation for parents and facilities to ease their hospital stay such as bathrooms, places to cook and eat, and laundry facilities (Shields, 2015). In Sweden, most hospitals offer rooms for adolescents less than 18 years old in family-centered pediatric wards, where they are not only allowed, but expected to be accompanied by a parent or other adult. On one hand, the possibility of having a parent accommodated in the pediatric ward has been reported to reduce stressful aspects of being admitted to hospital in children (Coyne, Hallstrom, & Soderback, 2016; Shields et al., 2006; Shields et al., 2012), younger adolescents (Clift et al., 2007), and parents (Angelhoff, Edell-Gustafsson, & Morelius, 2018). On the other hand, Swedish adolescents usually do not sleep in the same room as their parents at home, and older adolescents may live in their own apartments for studies or work. In this developmental stage marked by an increased need for autonomy, adolescents may find it undesirable to be cared for by a parent. Consequently, adolescents may want another relative or a friend to accompany them or even prefer to stay at the hospital by themselves. To the best of our knowledge, there is no previous study that describes how adolescents experience their stay in single-patient rooms at a family-centered pediatric ward.

Adolescents in shared rooms have described how their sleep was interrupted by bright light and noises, such as crying and yelling from younger children (Clift et al., 2007). Sleep has a key role in facilitating recovery, health, and well-being. Hospital stays may affect adolescents’ sleep quality negatively as routines at the ward are not adapted for adolescents’ activities or sleep habits. In order to provide optimal nursing interventions for adolescents admitted to hospital, more knowledge is warranted regarding adolescents’ sleep in pediatric wards. Therefore, this study aims to (a) explore and describe how adolescents experience sleep in the family-centered pediatric ward, (b) explore and describe how adolescents experience the presence or absence of a parent during the hospital stay, and (c) identify circumstances that the adolescents describe as influential of their sleep in the pediatric ward.

Methods

Design

This is a qualitative interview study employing thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) with an inductive and exploratory approach.

Participants and Procedure

Ethical approval was received by the Regional Ethical Committee (Dnr: 2017/473-31). Purposeful sampling was used to include adolescents with a recent experience of sleeping in hospitals. Swedish speaking adolescents, 13 to 17 years old, with sufficient cognitive and physical ability to participate in an interview, who had been admitted at least one night at a family-centered pediatric ward, were invited to participate in the study. Adolescents in palliative care and regular users of sleep-interfering medication were excluded from the study.

To cover perceptions from adolescents with different diagnoses and experiences, a university hospital with three family-centered pediatric wards for children aged 0 to 17 years old, specialized in oncology, surgery, and emergency medicine, respectively, was selected for data collection. During January through May 2018, eligible adolescents were identified by a department coordinator who gave written and oral information about the study in the wards. The coordinators also established contact between the adolescents and the authors. After informed consent, the interviewer contacted the adolescents in the ward or by phone to set a time for the interview and to ensure that the adolescents had a chance to ask questions regarding the study. Additional informed consent for participation was required and obtained from one parent for participants below the age of 15, in accordance with The Swedish Ethical Review Act, Article §18 (Swedish Code of Statutes, 2003). The act states that adolescents below the age of 15 should be informed about studies and should decide for themselves whether or not to participate. For children below the age of 15, both the child and the parent should be informed and consent. When the interview was conducted in the pediatric ward, the parents were given the option to be present if the adolescent wished.

Data Collection

The interview guide was semistructured with a focus on the adolescents’ habitual sleep patterns at home, perceptions of sleeping at a pediatric ward, how they perceived the presence or absence of their parents, previous experiences from being admitted to hospital, and factors influencing their sleep in the pediatric ward. The interviewers were registered nurse specialists in pediatric nursing (CA) and psychiatric nursing (JL) with previous experience of qualitative data collection through face-to-face and telephone interviewing. They conducted the interviews in their roles as researchers. None of the interviewers had any current or previous clinical or personal contact with the participants.

Ten of the interviews were conducted face to face in the patient room during the adolescents’ hospital admission (CA). In six cases, the adolescents were discharged from the hospital before a time could be set for an interview. The interviews were therefore conducted by phone instead (JL or CA). For telephone interviews, the adolescents were encouraged to choose a time that suited them to ensure that they would be relaxed and undisturbed during their interview. In all phone interviews, the adolescents were at home and all interviews were carried out according to plan (no rescheduling due to disturbing environmental factors). The onsite interviews started with an approximately five-minute-long informal conversation, during which demographic data were collected, before the audio recording started. The phone interviews were recorded promptly after greeting. The interviews had a recorded median time of 13 minutes.

Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was chosen, following the six steps described by Braun and Clarke (2006), for identifying, analyzing, and reporting themes within data. Codes were identified with an inductive approach using the aim to direct the analysis process in six steps: (a) The interviews were transcribed verbatim (by CA and JL) and read several times for familiarization of data. (b) Initial codes were then generated by two of the authors (CA and JL) independently of each other, to enhance consistency and credibility of coding. A coding comparison calculation showed an agreement score between 85% and 100%. (c) The codes were collated into potential themes and a theme map was made to check that the themes work in relation to the coded extracts and the data set. (d) The themes were reviewed and discussed in the research group until (e) definitions and names of the themes were set (Figure 1) and (f) the final report was produced. The software program NVivo 12 Pro was used to handle data during the analyzing process.

Figure 1.

Theme map.

Findings

Sixteen adolescents, nine girls and seven boys, participated in the study (for demographic data, see Table 1). Three themes were found: the importance of good sleep, safety as a prerequisite for sleep in hospital, and circumstances influencing adolescents’ sleep in hospital.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics.

| Study alias | Female (F)/Male (M) | Age | Number of nights at the hospitala | Cause of admission | Acute or planned admission | Accompanied during the night(s) by | Interview setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adam | M | 17 | 3 | Surgery, foot | Planned | Mother/fatherb | By phone |

| Alice | F | 16 | 3 | Surgery, spinal | Planned | Mother | By phone |

| Anton | M | 14 | 1 | Pain/neurological loss | Acute | Father | In the patient room |

| Casper | M | 15 | 1 | Surgery, foot | Planned | Mother | In the patient room |

| Elin | F | 13 | 4 | Surgery, spinal | Planned | Mother/father | In the patient room |

| Emma | F | 17 | 1 | Surgery, gallstone | Acute | Boyfriend | In the patient room |

| Hanna | F | 17 | 1 | Neurological loss | Acute | Mother | In the patient room |

| Julia | F | 15 | 1 | Surgery, foot | Planned | Mother | By phone |

| Kevin | M | 14 | 5 | Fracture, leg | Acute | Father | In the patient room |

| Linn | F | 13 | 3 | Surgery, hip | Planned | Motherc | In the patient room |

| Lucas | M | 17 | 2 | Surgery, ear | Planned | Father | By phone |

| Moa | F | 16 | 7 | Surgery, spinal | Planned | Mother | By phone |

| Oscar | M | 17 | 1 | Oncology, treatment | Planned | Mother | In the patient room |

| Robin | M | 17 | 1 | Epileptic seizures | Acute | Mother | In the patient room |

| Sara | F | 13 | 1 | Urinary problems, treatment | Planned | Mother | In the patient room |

| Tilde | F | 17 | 3 | Surgery, ear | Planned | Mother | By phone |

At time for the interview.

The mother and the father took turns of the nights.

Present during the interview.

Theme 1: The Importance of Good Sleep

This theme includes two subthemes: “Adolescents’ descriptions of good sleep and consequences of sleep loss” and “Adolescents’ descriptions of their sleep in the hospital,” describing adolescents’ experiences of sleep at home and in hospital. The descriptions of the adolescent’s habitual sleep and consequences of sleep loss are used in the findings as a foundation to understand how they experienced their sleep in the hospital.

Adolescents’ descriptions of good sleep and consequences of sleep loss

The adolescents described good sleep in terms of sleep duration, going to bed at a certain time and waking up another, falling asleep directly on bedtime, sleeping through the night without awakenings, and waking up feeling rested and joyful. They also mentioned dreams; good dreams were mentioned with good sleep whereas nightmares were said to predict poor sleep. The participant Robin defined a good sleep thus: “that you’re happy when you’re going to bed so that you’re happy when you’re going to sleep and then that you fall asleep fast and kinda get to sleep the whole night and kinda wake up rested like.”

Some adolescents knew that too little or too much sleep was negative for them and someone also spoke of the importance of obtaining deep sleep in order to wake up feeling alert. Sleep was considered important in order to be able to manage school, work and other activities. Lucas described how sleep duration affected his ability to perform:

If I sleep like six hours per day then, uh, per night then I won’t be as physically active, uh, the day after, but if I sleep like eight to ten hours the day before I’ll perform better you know in different situations for example school, football field and such.

They described how a night of poor sleep at home affected them in their daily life as it led to daytime sleepiness, energy loss, and a decreased ability to concentrate and perform in school. Sleep loss also affected their mood as they more easily became easily angry and grumpy. It was common for them to sleep in during weekends to regain energy and be more alert.

Adolescents’ descriptions of their sleep in the hospital

Almost all adolescents started the interview by saying that they had slept well in the hospital. They described how they had gone to bed earlier in the evening and that they stayed longer in bed in the morning than they did at home. Some said that they slept as well as they did at home. However, when they started to describe their sleep more specifically, they described a light sleep with frequent awakenings during the night. A typical answer would start positively but end with an elaboration of phenomena that in fact had disrupted their sleep: “It’s been pretty good, the thing is that you don’t sleep as deeply because you get woken up like this” (Linn). Most adolescents described that they were difficult to wake up at night and easily went back to sleep after the awakenings. Therefore, they did not think that the awakenings interfered with their sleep that much.

The adolescents were used to being physically active. As there was not much for them to do during the days, they were inactive and felt passive. Kevin who was admitted to the hospital because of a leg fracture, described that there was not much to do during the days: “I scratch my leg and I watch movies.” Lying passively in the patient bed without anything to do during the day made the adolescents bored, tired, and lethargic, and it was common to take a nap or rest. Adam reflected over how the lack of activity affected his sleep at night and what he could do about it:

You know it’s yourself you have to try and keep occupied during the day, cause if you don’t do anything during a whole day and just sit and like check your phone or something then you don’t burn any energy and that makes that when you’re gonna sleep you won’t be able to sleep, so I’d like to say just try to do something in general, maybe that’s just playing cards for a bit, or try to sit up or try to move a bit, just do something and instead of just lying doing absolutely nothing cause then it will be hard to sleep.

Theme 2: Safety as a Prerequisite for Sleep in Hospital

This theme describes how nurses and the presence of someone who knew the adolescents, well provided safety which facilitated sleep. The theme includes two subthemes: “The hospital is a safe place” and “You need someone present who knows you well.”

The hospital is a safe place

The adolescents were admitted because of illness, trauma, or surgery, but could relax at the ward, knowing that they were at the right place with skilled people who wanted them to recover quickly. They described that they felt safe and well cared for at the hospital. The hospital was a safe place, where nothing bad could happen to them: “I felt that the hospital was always a safe place, you know you feel safe here and that calms you down a bit” (Casper).

The adolescents felt that they were listened to and treated with respect at all hours by the nurses. They described the nurses and doctors as competent and considerate. It was comforting to know that the staff checked on them repeatedly to see that everything was under control or if the adolescent needed something, especially during the night. It also felt safe knowing that they easily could press the alarm button if they needed help.

You need someone present who knows you well

All adolescents had a parent who stayed with them during the night, except for one girl who had her boyfriend accompany her. The parents were an important source of support for the adolescents. They wanted their parents to be there, not only for practical support but also for emotional support and company. Alice had undergone major spinal surgery and expressed the importance of having her mother present:

You know it is a comfort to have someone with you considering that a lot of things happen and you’re in pain and you need help so it is a great, you know I think it’s a great comfort to have someone with you … during such period cause it’s pretty hard.

It should be noticed that in this context the presence of a parent was perceived as natural for the adolescents. It had not occurred to them that they could have stayed at the hospital by themselves and they were surprised by the question of how they had experienced having a parent present during the night. Sara explained: “If I’d lived in some country where I couldn’t bring any people then I’d never gone to the sick bay, you know you want someone to support you and knows stuff about you.”

The adolescents described the safeness of having someone else in the room, watching over them during the night. The parents’ presence made them calmer and able to relax. The parents could console, comfort, and give pep talks to decrease worries and anxiety when the adolescents were unable to sleep. Lucas described how his father’s presence helped him to fall asleep the night before his surgery: “then I had this, couldn’t sleep, he [implied: Dad] checked [implied: me], he saw that I couldn’t sleep and maybe spurred me on then said to me, everything is going to be fine and such, eventually I slept.” Moreover, the adolescents described that it felt secure to have the parents in the room, as nurses and doctors could enter the room any time during the night. The parents did not necessarily have to do anything, the presence of having them sleeping in the same room decreased anxious mood and facilitated sleep. This was described by Adam, whose parents had been taking turns to keep him company in the hospital overnight:

Then you wake up a little then you need to look at something, you can’t just like close your eyes and then fall back asleep again but you need to look at something, so instead of just staring into the ceiling I could either just look around me or I could watch Mum and Dad when they slept, then I was inspired and fell asleep too.

It was important to have someone present who knew them personally, understood their needs, and could call for help if necessary. The adolescents described that they appreciated have the parents present to help them with practical support, such as help during toilet visits, help to change clothes, and to go and get things outside the room. “It was nice having a parent here who could help me or … when I needed to go into the loo then, it’s always nice to have a parent to help me, who knows me a bit better, best” (Casper).

The parents could also act as an interpreter between the doctors and the adolescent if it was unclear what the doctor said. Moreover, the adolescents described how they appreciated the company, both during the day and the night. Without company, the hospital stay would have been both lonely and boring. Having someone present made it easier to cope with the situation and time went faster when they had someone to talk to and play games with. But they missed their peers and other adolescents in their own age at the ward.

Emma had her boyfriend staying overnight. She described that she was surprised when the nurses asked her and her parents if she wanted her boyfriend to stay with her: “I thought like only like relatives were allowed to join so, um, but that was a relieved feeling.” They were all comfortable with this arrangement and she was satisfied to have the option, as she and her boyfriend had plans for the evening before she got ill and was acutely admitted to the hospital. She continued,

He [implied: boyfriend] slept here, so that also felt a bit comforting … I usually have great great difficulties falling asleep when I’m alone so, uh, it was nice that he was here that made it a bit easier.

According to the adolescents, the absence of company would have been dreadful. They thought that it would be difficult to cope with the situation if they were not allowed to have someone there with them, and that it would have affected their mood negatively. Moa explained: “I don’t think I would have managed that week unless she [implied: Mum] had slept there.”

Theme 3: Circumstances Influencing Adolescents’ Sleep in Hospital

The adolescents described several circumstances that affected their sleep in the hospital. This theme contained three subthemes: health-related circumstances, organizational circumstances, and environmental circumstances.

Health-related circumstances

Pain was the most common reason for disrupted sleep in the hospital. Pain made it difficult to fall asleep and was a reason for awakenings during the night. The pain was relieved by analgesics, administered by the nurses. The drugs made the adolescents tired and sleepy, especially morphine. This helped them to fall asleep and they described that they probably had better sleep because of the drugs. On the other hand, drug treatment administered as intravenous infusions affected sleep negatively because of beeping sounds from the infusion pump and the need to go to the toilet during the night. The health condition and the drugs made the adolescents tired and drowsy during the day as well, which was pointed out by Moa:

I was completely out of it when I slept, uh, but then I was tired all the time and I dunno if that was because I slept poorly or if it was like the surgery made me so tired, and all the medications.

Other health-related issues such as urinary catheters, venous catheters, plasters that chafed, and sounds from suction and other medical devices also affected the adolescents sleep negatively.

Organizational circumstances

Nightly routines at the ward, such as regular vital sign checks and drug administration, affected the adolescents sleep as they were awakened several times during the night. However, they described that they fell asleep again rather quickly.

Despite nightly check-ups, the adolescents did not describe the nurses themselves as disruptive during the night; they did their job and helped the adolescents feel better.

The nurses worked quietly when they entered the room and the adolescents described that sometimes they did not even notice them. “A few times I noticed it, when they were going to attached the drip and such stuff, but they were actually very silent so it wasn’t as if I was scared or what you might say” (Tilde). However, some adolescents expressed that they felt worried and exposed during the night as they did not know who would enter the room or when during the night. This unpredictability was less apparent in one of the wards, whose routines included the regular times for vital sign checks and drug administration each night. This was appreciated by the adolescents as they knew when they could expect the nurses to enter the room and they could relax and sleep in between visits.

Environmental circumstances

There’s no place like home. The hospital environment and the patient rooms were described as alien, sterile, boring and depressing. The adolescents wished for more colors and joyful pictures on the walls. The atmosphere and the fact of being at a hospital affected their sleep negatively. Moa reflected over why she did not like to stay overnight at the hospital:

I often sleep at friends’, I often stay at hotels you know when I’m travelling, uh, I don’t know if the thing is that it’s a hospital but it’s nothing like the personnel then really were amazing and it really was a very nice hospital but I think it’s just that it’s a hospital generally.

Unfamiliar noises in the room or from other patient rooms and the corridor had a negative impact on their ability to fall asleep in night. The adolescents at one of the wards were disturbed by construction workers using an elevator outside the building from early morning to late evening. This woke them up in the morning and decreased their ability to rest during daytime.

Another issue that was brought up was the light. The adolescents wanted a dark room when they were sleeping. The patient rooms were too bright, and the adolescents wished for better blinds to improve sleep. They also mentioned the room temperature as they thought the rooms were too cold and they were happy that they were allowed extra blankets.

However, there were some positive thoughts expressed about the environment as well. The adolescents appreciated having their own, private room. They enjoyed that the patient beds were height adjustable and comfortable, even though the size of the beds was described as not always appropriate for adolescents. Alice shared her thoughts about the beds:

I’m pretty small and I thought that the bed was pretty small so I feel that there are bigger teens that you know that when they are in hospital then it might not be comfortable for them at all to be able to sleep cause the bed is so like tiny, I think they should have some different sizes on the beds.

The adolescents also appreciated having TV and DVD player in the room so that they could entertain themselves somehow during the days.

Discussion

This is the first study to describe adolescents’ experiences of staying overnight in a family-centered pediatric ward. In summary, the adolescents described their sleep at hospital positively, but they mentioned disturbing factors associated with pain, nightly check-ups, noises, and inactivity. Parental presence, as in the family-centered care model (Shields, 2015), was perceived as very positive both during the night and the day.

The perception of safety was connected to personal relationships; in that the adolescents expressed a need to have a parent, or other person that they felt safe with, present for practical and emotional support. The parents’ presence was described as helpful for coping with the situation and making it easier to relax and sleep during the night. According to Pelander and Leino-Kilpi (2010), separation from parents and family has been described as the worst experience during hospitalization by younger children (7–11 years). Clift et al. (2007) have reported how hospitalized children (11–15 years) wished for their parents to stay at the hospital during the nights. However, in that study, only one 13-year-old boy had a parent resident during his hospital stay, which he thought reduced his feelings of anxiety. To our knowledge, this is the first study reporting adolescents’ (13–17 years) descriptions of the importance of parental presence during their hospitalization. According to Campa, Hazan, and Wolfe (2009), the probability of seeking an attachment figure, a safe haven, is high when a person is facing a negative situation. Further, parents are the most important attachment figures among young adults. In the current study, this could explain the adolescents’ wish for a parent to stay, as the parents were their safe haven when the adolescents experienced the negative situation of being admitted to hospital. Adolescents must always stay in the center of the care and be treated with dignity and respect, acknowledging their competence and supporting their actions in conjunction with the need of their family (Coyne et al., 2016; Soderback, Coyne, & Harder, 2011). However, in some families, the parents might not be the right individuals to support the adolescent. The pediatric nurse must be attentive to the adolescent’s perspective of what is best for that specific individual (Coyne et al., 2016). We suggest that adolescents should have the opportunity to be accompanied by a parent or other attachment figure during hospitalization, to cope with the negative feelings that a hospital admission could bring. Previous studies have found that there is a lack of accommodation possibilities for parents in the pediatric wards (Stremler, Adams, & Dryden-Palmer, 2015) or that adolescents are admitted to adult wards (Dean & Black, 2015; Olsen et al., 2016). A clinical implication of our findings is that all children below the age of 18 always should be admitted to pediatric wards, organized to accommodate parents during their child’s hospital stay.

A salient theme regarded the relation between safety and good sleep. Safety was also associated with the hospital context as they described that they felt safe at the pediatric ward and trusted the competency of the nurses; some to a point where nightly check-ups or procedures were slept through. Others described that the nightly procedures were disturbing as it was out of their control when someone would enter their room or who it would be.

Even though the adolescents first described their sleep as good at the pediatric ward, they all described interruptions during the night that led to nocturnal awakenings. This was mainly due to health-related circumstances and routines at the ward. Previous studies of sleep in pediatric wards have implicated that vital sign checks and medical treatments during the night should be scheduled at the same time, and when medically appropriate they should be less frequently performed (Angelhoff et al., 2018; Meltzer et al., 2012). What this study adds is that a lack of control over whom or when someone comes in to the room during the night may increase feelings of insecurity and exposure and decrease the adolescent’s ability to relax and sleep. The adolescents at the ward with fixed schedule for vital sign checks and medical treatments appreciated knowing when the nurses would come in. In cases where a fixed schedule is not appropriate for the care, the nurse must inform the adolescent about the schedule for the night so that the adolescent feels comfortable and able to sleep.

Passivity and inactivity were described as other circumstances that influenced the adolescents’ sleep negatively. They described that the pediatric wards were designed for younger children and they missed peers and activities that suited their age. Adolescent wards, specially designed for teenagers’ needs (Payne et al., 2012), could be one way to reduce inactivity and improve sleep.

Strengths and Limitations

One strength with this study is that we included adolescents of both sexes in various ages and diagnoses in three different pediatric wards to get a broad view of the subject. Moreover, the interviews were conducted during the adolescents’ hospitalization, or shortly after, to capture their actual experiences. A limitation of this study is the wide range of days in the hospital. Perceptions of sleep could change over time when sleeping in a hospital due to frequent night awakenings. Those who had been in the hospital for only one night might have a different perception if they had been in the hospital longer. Moreover, those with a planned stay could have been more prepared psychologically than those who were admitted acute. This could also have influenced the adolescents’ perceptions. Another limitation of the study is that could be that no psychiatric ward was included, which reduces the transferability of the findings. Further, some interviews were short. However, they included informative data and were appropriate to be included in the analysis. The COREQ checklist for reporting was used to ensure that all relevant information was included in the paper (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007).

Conclusion

To conclude, in general adolescents described their sleep at hospital in positive words although disturbing factors were also mentioned and their sleep patterns were different than usual. Their parents were identified as an important source of safety and associated with the ability to sleep. The adolescents wanted the parents to be there to support them, practically as well as emotionally. Pain, medical treatment, vital sign checks, and the environment were influencing the adolescents’ sleep negatively. Boredom and inactivity were also perceived as barriers to good sleep. Taken together, the results indicate that parental participation, predictability regarding vital sign check timings, and an environment that facilitates activity should be considered when reconstructing or building new hospitals to improve adolescents’ sleep during hospitalization.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to give a special thank you to Mia Ekstedt, Crown Princess Viktoria Children’s Hospital, Linköping, Sweden, for her help with recruitment, and all the participating adolescents for their time. The authors would also like to express their gratitude to Iain Clarke for proofreading the manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by Ebba Danelius Foundation, Filip Schelin Foundation, Foundation for Paediatric Research Linköping University, and Lawrence S. Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing University of Toronto.

ORCID iD

Charlotte Angelhoff https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0174-8630

References

- Angelhoff C., Edell-Gustafsson U., Morelius E. (2018). Sleep quality and mood in mothers and fathers accommodated in the family-centred paediatric ward. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(3–4), e544–e550. doi:10.1111/jocn.14092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltrami F. G., Nguyen X. L., Pichereau C., Maury E., Fleury B., Fagondes S. (2015). Sleep in the intensive care unit. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia, 41(6), 539–546. doi:10.1590/S1806-37562015000000056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [Google Scholar]

- Campa M. I., Hazan C., Wolfe J. E. (2009). The form and function of attachment behavior in the daily lives of young adults. Social Development, 18(2), 288–304. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00466.x [Google Scholar]

- Clift L., Dampier S., Timmons S. (2007). Adolescents' experiences of emergency admission to children's wards. Journal of Child Health Care, 11(3), 195–207. doi:10.1177/1367493507079561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne I., Hallstrom I., Soderback M. (2016). Reframing the focus from a family-centred to a child-centred care approach for children's healthcare. Journal of Child Health Care, 20(4), 494–502. doi:1367493516642744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean L., Black S. (2015). Exploring the experiences of oung people nursed on adult wards. British Journal of Nursing, 24(4), 229–236. doi:10.12968/bjon.2015.24.4.229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmy P., Ward T. M. (2017). Sleep habits and nighttime texting among adolescents. The Journal of School Nursing, 1059840517704964. doi:10.1177/1059840517704964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert A. R., de Lima J., Fitzgerald D. A., Seton C., Waters K. A., Collins J. J. (2014). Exploratory study of sleeping patterns in children admitted to hospital. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 50(8), 632–638. doi:10.1111/jpc.12617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson-Frojmark M., Norell-Clarke A., Linton S. J. (2016). The role of emotion dysregulation in insomnia: Longitudinal findings from a large community sample. British Journal of Health Psychology, 21(1), 93–113. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamdar B. B., Needham D. M., Collop N. A. (2012). Sleep deprivation in critical illness: Its role in physical and psychological recovery. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine, 27(2), 97–111. doi:10.1177/0885066610394322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudchadkar S. R., Aljohani O. A., Punjabi N. M. (2014). Sleep of critically ill children in the pediatric intensive care unit: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Review, 18(2), 103–110. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2013.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Narendran G., Tomfohr-Madsen L., Schulte F. (2017). A systematic review of sleep in hospitalized pediatric cancer patients. Psychooncology, 26(8), 1059–1069. doi:10.1002/pon.4149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massimo L., Rossoni N., Mattei F., Bonassi S., Caprino D. (2016). Needs and expectations of adolescent in-patients: The experience of Gaslini Children's Hospital. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 28(1), 11–17. doi:10.1515/ijamh-2014-0070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medic G., Wille M., Hemels M. E. (2017). Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nature and Science of Sleep, 9, 151–161. doi:10.2147/nss.s134864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer L. J., Davis K. F., Mindell J. A. (2012). Patient and parent sleep in a children's hospital. Pediatric Nursing, 38(2), 64–71; quiz 72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohayon M., Wickwire E. M., Hirshkowitz M., Albert S. M., Avidan A., Daly F. J., … Vitiello M. V. (2017). National Sleep Foundation’s sleep quality recommendations: First report. Sleep Health, 3(1), 6–19. doi:10.1016/j.sleh.2016.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen I. O., Jensen S., Larsen L., Sorensen E. E. (2016). Adolescents’ lived experiences while hospitalized after surgery for ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology Nursing, 39(4), 287–296. doi:10.1097/sga.0000000000000154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens J. A., Weiss M. R. (2017). Insufficient sleep in adolescents: Causes and consequences. Minerva Pediatrica, 69(4), 326–336. doi:10.23736/s0026-4946.17.04914-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne D., Kennedy A., Kretzer V., Turner E., Shannon P., Viner R. (2012). Developing and running an adolescent inpatient ward. Archives of Disease in Childhood: Education and Practice Edition, 97(2), 42–47. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2011-300068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelander T., Leino-Kilpi H. (2010). Children's best and worst experiences during hospitalisation. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, 24(4), 726–733. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00770.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulak L. M., Jensen L. (2016). Sleep in the intensive care unit: A review. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine, 31(1), 14–23. doi:10.1177/0885066614538749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi N., Abdeyazdan Z., Motaghi M., Rad M. Z., Torkan B. (2012). Satisfaction levels about hospital wards' environment among adolescents hospitalized in adult wards vs. pediatric ones. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 17(6), 430–433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields L. (2015). What is “family-centred care”? European Journal for Person Centered Healthcare, 3(2), 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Shields L., Pratt J., Hunter J. (2006). Family centred care: A review of qualitative studies. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15(10), 1317–1323. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01433.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields L., Zhou H., Pratt J., Taylor M., Hunter J., Pascoe E. (2012). Family-centred care for hospitalised children aged 0–12 years. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 10, CD004811. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004811.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shochat T., Cohen-Zion M., Tzischinsky O. (2014). Functional consequences of inadequate sleep in adolescents: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Review, 18(1), 75–87. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2013.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare]. (2017). Diagnoser i slutenvård [Diagnoses in inpatient care]. Retrieved from http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik/statistikdatabas/diagnoserislutenvard

- Soderback M., Coyne I., Harder M. (2011). The importance of including both a child perspective and the child's perspective within health care settings to provide truly child-centred care. Journal of Child Health Care, 15(2), 99–106. doi:10.1177/1367493510397624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stremler R., Adams S., Dryden-Palmer K. (2015). Nurses' views of factors affecting sleep for hospitalized children and their families: A focus group study. Research in Nursing & Health, 38(4), 311–322. doi:10.1002/nur.21664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Code of Statutes. ( 2003). SFS 2003:460: Lag om etikprövning av forskning som avser människor [The act concerning the ethical review of research involving humans]. Retrieved from https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/lag-2003460-om-etikprovning-av-forskning-som_sfs-2003-460

- Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx