Abstract

Moral dilemmas are present in all settings in which nurses work. Nurses are moral agents who must make moral decisions and take moral action in very complex social systems. Nurses are accountable for their actions, and it is therefore imperative that they have a solid foundation in ethics. There are multiple ethical frameworks nurses can utilize to justify their actions. A theory of moral ecology is presented here as a way to conceptualize the relationships between these frameworks. The first two steps of moral action, moral sensitivity and moral judgment, are explored in a pluralistic context. Specifically, multiple ethical frameworks that inform the practice of nursing are presented using an ecological model. Nurses work in a variety of practice environments, with different populations, across a spectrum of situations. An ecological model acknowledges that nurses are influenced by the complex social, and ethical, systems in which they find themselves taking moral action. When faced with ethical issues in practice, a nurse's moral sensitivity and moral judgment may be guided by ethical systems most proximal to the situation. Nurses bring individual moral beliefs to work and are influenced by the ethical directives of employers, the discipline's code of ethics, principles of bioethics, and various approaches to normative ethics (virtue, consequential, deontological, and care). Any of the frameworks presented may justifiably be applied in various nursing circumstances. I propose that the multiple ethical frameworks nurses utilize exist in a relationally nested manner and a model of moral ecology in nursing is provided.

Keywords: ethical decision-making, nursing theory, moral agency, nursing ethics, moral ecology

Moral dilemmas, situations in which two or more ethically justifiable courses of action exist, arise daily in health-care settings. In these situations, the clinician facing the dilemma must choose one moral action at the expense of the alternatives and is therefore destined to act immorally regardless of the action taken (McConnell, 2014). To face a moral dilemma, one must be a moral agent. Individual moral agents are people expected to make ethical decisions and be held accountable for their actions. There are multiple notions of right and wrong that influence individual nurses and nurses, as licensed professionals, are accountable for their actions; therefore, nurses are moral agents.

Moral agents must take moral action within a situational context. Rest (1986) proposed four steps to moral action: moral sensitivity or awareness, moral judgment or decision-making, moral intent, and moral character or ability to transform intent into action. For the purpose of this discussion of moral ecology in nursing, it is assumed that nurses intend to act morally in their work. It is also assumed that nurses are not always able to engage in actions they deem moral due to a variety of constraints, and that this is a cause of moral distress, a topic beyond the scope of this article. Therefore, the first two steps of moral action, moral sensitivity and moral judgment, are emphasized. Nurses bring to work their own individual moral perspectives. Their work is also influenced by multiple ethical frameworks. How nurses identify or describe work-related ethical issues, and how they make moral decisions in dynamic health-care contexts are not necessarily static. It is proposed here that the multiple ethical frameworks guiding nurses' moral action may exist in a relationally nested manner. The model of moral ecology is used to explore moral sensitivity or awareness and moral judgment or decision-making in nursing.

Moral Pluralism

There has been debate in the nursing community regarding whether a unique ethical framework should be developed, or an existing framework adopted. A different path forward for nursing is to adopt a pluralistic approach to ethics (McCarthy, 2006). Given the widely divergent practice, educational, and research settings in which nurses work, there is potential value in providing nurses with a multitude of frameworks from which to draw guidance. Providing nurses freedom and flexibility to apply a variety of different perspectives based on the specific context in which they find themselves is a good disciplinary fit given the complex landscape in which nursing occurs.

Moral pluralism posits that many different moral views can conflict with one another, yet still exist simultaneously. Moral absolutism claims there are universal moral principles that apply to all. Moral relativism on the other hand asserts that moral values vary across groups and over time. As practicing nurses find themselves in positions in which they must apply some ethical framework in action, adopting a pluralistic approach allows nurses to approach what are often very complicated situations with a toolbox of frameworks from which they can utilize what is most applicable and most proximal. What is proposed here is a theory of moral ecology grounded in pluralism.

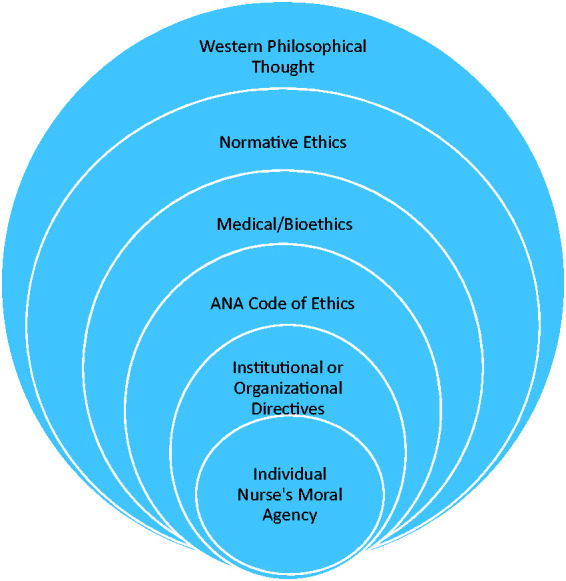

This model may be used in educational settings to teach concepts of moral sensitivity and judgment. Introducing nursing students to the language used and ideas expressed in multiple frameworks can help them develop an awareness of ethical issues and the skills to justify their decisions based on an identified framework. In practice, nurses may reflect on this model as they apply one or more of the ethical frameworks in nursing action. Nurses ought not act in ways that violate their own morals; if nurses violate ethical directives of the workplace or the discipline they risk losing jobs and licensure. Extending beyond those individual, organizational, and disciplinary perspectives are principles of ethics in health care in general and beyond that normative ethics that inform society's perceptions of right and wrong. The visual representation of the model, see Figure 1, presents nurses' individual moral perspectives within larger ethical systems that are related to, not separate from, one another.

Figure 1.

An ecological model of ethics in nursing.

Moral Ecology

Urie Bronfenbrenner's (1977) ecological model of human development is widely used as a framework to understand individual behavior in the context of complex social systems. He proposed that in order to understand human development, there must be more than mere observation of human behavior; there must also be examination of the systems in which that behavior occurs. He described the ecological environment in which human development occurs as “a nested arrangement of structures, each contained within the next” (p. 514). He goes on to describe the microsystem as the relationships between a person and the immediate setting. The mesosystem refers to the relationships between those settings; the exosystem is an extension of the mesosystem that contains additional social structures that indirectly impact the individual. Finally, the macrosystem is the overarching culture or subculture in which social structures and activities exist, imparting implicit and explicit ideology.

Moral ecology uses this theoretical understanding of human behavior to understand the relationship between individual moral action and the ethics and values of the systems in which the moral agent finds him or herself. To understand moral action, it is necessary to understand the multiple ethical systems in which that action occurs. It is possible that an individual nurse's moral awareness, decision-making, and subsequent action may be situated in such a manner.

This is not an exhaustive presentation of ethical frameworks, nor does it delve into the benefits, drawbacks, or debates regarding their utility in nursing. The aim is to present the overarching, nested ethical influences affecting the day-to-day work of practicing nurses. As illustrated in Figure 1, the ethical systems affecting the nurse as a moral agent, from the micro to the macro level, are individual morals or values, institutional or organizational ethical directives, the American Nurses Association (ANA) Code of Ethics, the principles of medical or bioethics, and normative ethics (virtue, consequential, deontological, and care ethics), all of which are recognized within the broad context of Western philosophical thinking. This model is presented from the lens of American nursing; however, if useful, the model of moral ecology can be applied substituting different layers; the International Council of Nurses Code of Ethics and Islamic ethics for example.

Normative Ethics

Normative ethics is the branch of ethics interested in answering questions such as what ought we do, or what is the right course of action? Three commonly discussed approaches to normative ethics are virtue ethics, consequentialism, and deontology. One characteristic that separates nursing from other health-related disciplines is an emphasis on holism or whole person care. Nurses recognize humans as bio-psycho-social-spiritual-cultural beings living in ever changing environments. A cornerstone of nursing is providing care to people. Multiple definitions of nursing reflect this. Merriam-Webster (n.d.) defines a nurse as, “a person who cares for the sick or infirm.” The International Council of Nurses (n.d.) defines nursing as “an integral part of the health care system, encompassing the promotion of health, prevention of illness, and care of physically ill, mentally ill, and disabled people of all ages, in all health care and other community settings.” Because care is a central concept to nursing, feminist or care ethics is also included in this discussion of normative ethics in nursing.

Virtue Ethics

Virtues, and their counterpart vices, are character traits or personal dispositions. Virtue ethics trace back to ancient Greece, Aristotle in particular. According to Aristotle (1998), Happiness is the “chief good,” the impetus for human activity, the one thing that humans choose for its own sake, and the “working of the soul in the way of perfect Excellence” (p. 17). He differentiated Excellence into Intellect (reason) and Moral (character) Excellence. Moral Excellence, a person's character, develops over time through a process called habituation, in which she or he repeatedly acts in qualitatively similar ways. Actions reveal a person's underlying propensities toward good or bad. Aristotle does not articulate specific right acts, but rather warns that feelings and actions exist along a spectrum of which the extremes are to be avoided. His doctrine of the mean guides us away from excess on one end, defects on the other, and suggests that virtue is the middle state between these two faulty states (Aristotle, 1998).

The founder of modern nursing, Florence Nightingale, also placed great emphasis on a person's character. Virtues, as ontological matters reflected in habitual behaviors, were of extreme importance to her. She had strong opinions about the kind of character nurses should possess. She reportedly interviewed nurses applying to her school and kept notes regarding their character. She wrote at the end of her famous Notes on Nursing, “Surely woman should bring the best she has, whatever that is, to the work of God's world . . . you want to do the thing that is good . . . ” (Nightingale, 1992, p. 76). To promote nursing as an honorable profession, she needed to upend the deleterious beliefs and perceptions Victorian England held regarding nursing. She raised the moral bar for nursing to the point where behaving immorally and behaving unprofessionally were synonymous (Sellman, 1997). To this end, being moral or virtuous is a character trait of nurses. It does not begin and end when one arrives to and leaves work. Several nursing scholars advocate for virtue ethics in nursing including Armstrong (2006), Arries (2005), Bliss, Baltzy, Bull, Dalton, and Jones (2017), Brody (1988), and Lutzen and Barbosa da Silva (1996).

The following is an example of how virtue ethics might be used to frame moral awareness and decision-making in nursing. A patient has died after several hours of enduring extreme pain. The patient's family member arrives and asks, “Did she suffer?” Truthfulness is a virtue; virtuous people are honest. The two ends of the honesty spectrum would be telling the truth, “yes, she suffered a great deal” or lying, “no, it was very peaceful.” The nurse could justifiably respond with a middle state, “she was in some pain and we tried to keep her comfortable.” Such a response acknowledges that absolute truth may cause the family member additional grief and lying is a vice.

Consequentialism or Utilitarianism

Consequentialism refers to the idea that the rightness or wrongness of an action is determined based on the consequences of that action (Horner & Westacott, 2000). The right action, therefore, is the one that results in the best consequences. Utilitarianism is one form of consequentialism. Very simplistically, utilitarianism proposes that given the choice between two actions, the best option is the one that results in the greatest good for the greatest number. As with Aristotle's virtues, happiness or pleasure is what constitutes good in this framework, and for the same reason, happiness or pleasure has intrinsic value, apart from being a means to something else (Horner & Westacott, 2000). Utilitarianism demands consideration of the consequences of action on everybody impacted by that action, not only the moral actor. Furthermore, utilitarianism posits that all peoples' happiness counts equally.

Jeremy Bentham, a leading figure in utilitarianism, was primarily interested in the relationship between individuals and the state and laid out his ideas on morality and law in his 1789 work, Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1907). Utilitarianism is therefore, not surprisingly, used as a tool to inform public policy decision-making. John Stuart Mill (2002), a contemporary of Bentham, proposed a harm principle which suggests that the only justifiable reason for limiting a person's freedom is to prevent harm to others. This principle has informed public health policy in the United States (Childress et al., 2002; Roberts & Reich, 2002). It also underpins mental health policies dictating the specific circumstances under which individuals may be involuntarily hospitalized or medicated.

The following is an example of how consequentialism might be used to frame moral awareness and decision-making in nursing. A patient on an inpatient psychiatric unit receives bad news over the phone. The patient begins beating his head against the wall. As staff members approach him, he lunges at them spitting, kicking, and hitting. The charge nurse directs him to be placed in physical restraints. Even though this action violates the patient's right to freedom and movement, it is justified in order to protect the safety of staff and other patients on the unit.

Deontology or Duty Ethics

As a duty-based approach to ethics, deontology treats the consequences of action as wholly irrelevant. Immanual Kant is perhaps the most well-known proponent of deontology, particularly his notion of a categorical imperative; a rule without exception. Kant proposed that there are right and wrong actions, regardless of context and consequence. He suggested that there was a universal, unconditional moral obligation called the categorical imperative (Johnson & Cureton, 2018). Two of the specific formulations of his categorical imperative are as follows: “act only on that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it should become universal law” and “act as to use humanity, both in your own person and in the person of every other, always at the same time as an end, never simply as a means” (Bell, 2003, p. 736). In its most simplistic form, the categorical imperative is a directive to treat others as ends in and of themselves, rather than as a means to an end, or The Golden Rule, treat others as you wish to be treated.

In this framework, universal duties include be honest, do not steal, and do not kill people. These duties apply to all people in all situations. In addition to such universal duties, the nursing profession also identifies specific duties nurses must observe. The ANA (2015b) provides a Scope and Standards of Practice; “the standards are authoritative statements of the duties that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, or specialty, are expected to perform competently” (p. 3). There are 17 behavioral standards articulated in the most recent version of this document, which include standards of practice and professional performance (ANA, 2015b). In this respect, nurses' moral agency, that is, the justification for choosing a specific course of action and the ability to be held accountable for that action is at least partially derived from a deontological framework.

The following is an example of how deontology might be used to frame moral awareness and decision-making in nursing. A non-English speaking patient arrives in the emergency department. The nurse assesses that her condition is emergent, but not life threatening. The nurse gets the patient situated but does not immediately initiate any treatment and instead calls for a translator. The nurse is justified in delaying this patient's care because of his or her duty to communicate with patients in a manner they understand.

Feminist or Care Ethics

Feminist ethics in general pushes against traditional normative ethics in several ways. Jagger (1992) argued that traditional ethics shows less concern for women's interests or issues, views moral issues that arise in the private world as trivial, implies that women are less morally mature than men, values masculine traits while undervaluing feminine traits, and favors reliance on rules and universals rather than relationships and context in moral reasoning. One particular type of feminist ethics is care ethics. This approach to ethics brings into focus the values and virtues historically associated with women. In direct opposition to the utilitarian call to remain impartial, to count everybody's interests equally, care ethics gives permission to think of those with whom we have a relationship first. As communal beings, the relationships formed with others are central to the human experience; therefore, those relationships must be considered when making ethical decisions. Noddings (1984) described ethics as being concerned with relationships between two people, one who is cared for and one who provides that care. This description of care ethics seems particularly well suited to nursing practice.

Carol Gilligan is a discernable champion of care ethics. Her work In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women's Development (1982) was a rebuttal to Lawrence Kohlberg's widely accepted theory of moral development. She argued that Kohlberg's theory of human moral development was biased toward a masculine perspective; a perspective that places enormous value on autonomy, rights, and justice. It also positioned women as morally inferior to men. Gilligan noted that this inherent bias overshadowed other values such as attachment, responsibility, and context. She proposed an ethical system in which decisions are based on what is best for the people involved in the relevant contextual relationship.

One final aspect of care ethics applicable to nursing is recognition of the power dynamics inherent in relationships between caregivers and the recipients of that care. While this dynamic is present in caring relationships in general, the relationship between mother and child is often used as an archetype. In a basic form, the maternal relationship is about meeting the needs of others through cooperation and community; this is a perspective that traditional ethics misses. It misses this in part because it overvalues the public sphere, the world of men, and undervalues the private sphere, the world of women. Virginia Held turned this idea on its head by suggesting that the concerns of the public sphere would not even be possible were it not for the caring behaviors present in familial relationships. As an example, from her perspective care can exist without justice, but justice cannot exist without care (Held, 2006).

There is a rather robust body of literature regarding care and caring in nursing. Benner and Wrubel's (1989) The Primacy of Caring: Stress and Coping in Health and Illness is widely referenced. Jean Watson has established the Watson Caring Science Institute (n.d.). Other writers on caring in nursing include Gadow (1999), Bowden (2000), Liaschenko (1993), Paley (2002), Bottorff (1991), and Tarlier (2004). This body of literature addresses care as an aspect of nursing practice, as a theoretical construct in nursing, and as an ethical framework. With respect to the role of caring in nursing ethical theory, Fry (1989) wrote,

Present theories of medical ethics have a tendency to support theoretical and methodological views of ethical argumentation and moral justification that do not fit the practical sense of nurses' decision-making in patient care and, as a result, tend to deplete the moral agency of nursing practice rather than enhance it. (p. 98)

The following is an example of how care ethics might be used to frame moral awareness and decision-making in nursing. A patient is dying from end-stage liver failure secondary to alcohol addiction. He has been on an acute care floor for 3 weeks and has not had any visitors during that time. A nurse has taken care of this patient 15 of the last 21 days and has developed a fondness for him. As this nurse's shift ends, it is anticipated that the patient will die in the next few hours. The nurse clocks out, gives the patient a bed bath and sits with him until he dies. The nurse is justified in blurring the lines between personal and professional relationships and caring for him while off-the-clock in recognition of his human dignity and to prevent him from dying alone.

Medical Ethics or Bioethics

While nursing is its own distinct profession, it has long existed in the “shadow” of medicine. Prior to the advent of nursing schools operating under the sole leadership of nurses, physicians often taught nursing students. To this day, a common misperception is that nurses work under, rather than alongside, physicians. Due to the primacy of medicine in all aspects of health care and the historical development of nursing as a profession, nurses are inherently affected by the field of medicine, and in this case medical ethics.

The code of ethics for medical practice can be traced back to the Greek physician Hippocrates. The Hippocratic Oath, written around 400 BC introduced principles to be upheld by physicians and their students. It was drafted in antiquity and innumerable advances in technology, science, and the economics or politics of health care since that time make parts of the oath obsolete. There are, however, duties outlined in it that are as relevant now as they were then. For example, it obliges physicians to provide only beneficial treatments, to protect patients from harm and injustice, and to maintain confidentiality (Hippocratic Oath, n.d.). These remain fundamental canons of medicine.

The first edition of Beauchamp and Childress' Principles of Biomedical Ethics was published in 1979. In it, they proposed four principles to be applied in biomedical settings or situations to help guide decision-making. While this book is now in its seventh edition, the four original principles have never been altered. These widely accepted principles of bioethics are as follows: beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice (Beauchamp & Childress, 2012). Beneficence calls us to act in the best interest of others, non-maleficence means avoiding harm to others, autonomy refers to the rights of individuals to make their own decisions, and justice requires that we treat people fairly and equitably (Beauchamp & Childress, 2012).

The following is an example of how bioethics might be used to frame moral awareness and decision-making in nursing. A 56-year-old patient has Stage III pancreatic cancer. She has undergone several rounds of chemotherapy with minimal effect. While in her 30s, she underwent radiation therapy for breast cancer, which was effective. These therapies resulted in pain, fatigue, blistering skin, hair loss, and persistent nausea. She has decided that she does not want any further chemotherapy or radiation. Her oncology nurse practitioner is participating in an institutional review board approved research trial of an experimental medication. The risks and benefits of this experimental treatment were explained to her. The patient's husband wants her to participate in the trial. The patient is declining all treatment offered. While the oncology nurse practitioner believes metastasis can be prevented by further treatment, the patient is recognized as an autonomous decision maker and her wishes are respected. The nurse practitioner agrees to adopt a palliative, rather than curative, approach to her care.

Nursing Code of Ethics

In 1926, the ANA published its first “suggested” code of ethical behavior for nurses (Epstein & Turner, 2015). The first formal code of nursing ethics was adopted in 1950, and it has undergone multiple revisions since that time, most recently in 2015. There are currently nine provisions in the Code of Ethics for Nurses (2015a), outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Provisions in the American Nurses Association Code of Ethics for Nurses.

| Provision 1 | The nurse practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person. |

| Provision 2 | The nurse's primary commitment is to the patient, whether an individual, family, group, community, or population. |

| Provision 3 | The nurse promotes, advocates for, and protects the rights, health, and safety of the patient. |

| Provision 4 | The nurse has authority, accountability, and responsibility for nursing practice, makes decisions, and takes action consistent with the obligation to promote health and to provide optimal care. |

| Provision 5 | The nurse owes the same duties to self as to others, including the responsibility to promote health and safety, preserve wholeness of character and integrity, maintain competence, and continue personal and professional growth. |

| Provision 6 | The nurse, through individual and collective effort, establishes, maintains, and improves the ethical environment of the work setting and conditions of employment that are conducive to safe, quality health care. |

| Provision 7 | The nurse, in all roles and settings, advances the profession through research and scholarly inquiry, professional standards development, and the generation of both nursing and health policy. |

| Provision 8 | The nurse collaborates with other health professionals and the public to protect human rights, promote health diplomacy, and reduce health disparities. |

| Provision 9 | The profession of nursing, collectively through its professional organizations, must articulate nursing values, maintain the integrity of the profession, and integrate principles of social justice into nursing and health policy. |

This Code of Ethics has clearly drawn on multiple ethical frameworks. It is both normative and aspirational and was written to be applicable in all settings. Its purpose is to state the ethical values, obligations, duties, and professional ideals of nurses individually and collectively, provide the profession's nonnegotiable ethical standard, and express nursing's understanding of its commitment to society (ANA, 2015a). In addition to informing decision-making in nursing practice, it is also intended to “inform every aspect of the nurse's life” (ANA, 2015a, p. vii).

The following is an example of how the ANA Code of Ethics for Nurses might be used to frame moral awareness and decision-making in nursing. A nursing professor teaches in a state that is considering legislation denying hospitals the ability to act as sanctuaries for undocumented individuals. The nurse educator facilitates a classroom debate with undergraduate nursing students, accompanies graduate students to the capital to listen to hearings, and volunteers as a member of a statewide hospital association task force to fight the proposed bill. These activities promote human dignity, collaboration with other disciplines, and help inform health policy to promote social justice and reduce health disparities.

Institutional or Organizational Directives

The final ethical framework that may impact nursing action is an organizational or institutional directive. A specific example would be the Ethical and Religious Directives (ERDs) for Catholic health-care services. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops produces this document, and its sixth edition was published in 2018. The purpose of the ERDs is

to reaffirm the ethical standards of behavior in health care that flow from the Church's teaching about the dignity of the human person … [and] to provide authoritative guidance on certain moral issues that face Catholic health care today. (United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2018, p. 4)

The 77 directives span six parts: the social responsibility of Catholic health-care services, the pastoral and spiritual responsibility of Catholic health care, the professional-patient relationship, issues in care for the beginning of life, issues in care for the seriously ill and dying, and collaborative arrangements with other health-care organizations and providers (United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2018). Every employee in Catholic health-care organizations are expected to act in accordance with these directives. While some of the directives would be supported by other frameworks presented (e.g., #34 respect each person's privacy and confidentiality), others are specifically supported by the Catholic Church's beliefs regarding specific issues (e.g., #48 in cases of extrauterine pregnancy no intervention is morally licit which constitutes a direct abortion).

The following is an example of how the ERDs might be used to frame moral awareness and decision-making in nursing. The operating room charge nurse is contacted to schedule a dilation and curettage, biopsy, and intrauterine device placement for a 34-year-old woman experiencing excessive vaginal bleeding of unknown origin. The nurse is aware of directive #53,

direct sterilization of either men or women, whether permanent or temporary, is not permitted in a Catholic health care institution. Procedures that induce sterility are permitted when their direct effect is the cure or alleviation of a present and serious pathology and a simpler treatment is not available. (United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2018, p. 19)

Prior to scheduling the procedure, the nurse contacts the physician for clarification. The patient has experienced severe bleeding for 2 weeks and was prescribed oral progesterone with no effect. It has not been possible to obtain a tissue sample to rule out hyperplasia or endometrial cancer in the outpatient setting. The proposed procedures are necessary to stop the severe bleeding and obtain tissue samples for diagnostic purposes. The intrauterine device is not being placed for birth control and current, simpler treatment is ineffective. The charge nurse therefore schedules the procedure.

Conclusion

As individual moral agents, nurses work within environments where multiple ethical frameworks coexist. As illustrated, any of these frameworks could be useful to help practicing nurses recognize ethical issues and provide justification for choosing different courses of action. First and foremost, however, nurses must not act in ways that violate their own sense of morality. They also must adhere to the ethical standards of the organizations in which they work and the profession as a whole. Beyond these frameworks that are most proximal to the nurse as moral agent are general principles of bioethics and most distant, but not irrelevant, are various normative ethical perspectives. They might contradict and they all coexist in what is proposed as a nested relationship. As described, this model of moral ecology in nursing may be useful in academic settings to introduce the multiple ethical frameworks impacting nursing practice to students. It may be used by practicing nurses in any environment to help raise awareness of ethical issues and provide language to describe the decision-making process and justification for a chosen course of action.

A pluralistic theory of moral ecology in nursing provides a way for nursing to free itself from thinking that moral agency needs to derive from a single position, whether that be a specific nursing ethical framework or an existing ethical framework. Nurses practice in morally pluralistic environments. They also work in environments of applied not theoretical ethics. The values of specific work settings, the profession of nursing, the broad health-care field, and general social views of morality are all at play when individual nurses directly face ethical issues in practice. Moral sensitivity, decision-making, and action all occur in the sociocultural context of these layers. When faced with situations in which ethical decisions must be made, it would be appropriate to justify nursing action using any of the frameworks identified. Positioning nurses as moral agents in this light allows flexibility. As situations and contexts change, so may the decision-making and justification for moral action. The more tools practicing nurses have in their ethical decision-making toolbox the more prepared they might be when called upon to use them.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- American Nurses Association (2015. a) The code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements, Silver Spring, MD: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association (2015. b) Nursing: Scope and standards of practice, 3rd ed Silver Spring, MD: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Aristotle (1998) Nichomachean ethics, Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong A. (2006) Towards a strong virtue ethics for nursing practice. Nursing Philosophy 7: 110–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arries E. (2005) Virtue ethics: An approach to moral dilemmas in nursing. Curationis 28: 64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp T., Childress J. (2012) Principles of biomedical ethics, 7th ed Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bell D. (2003) Kant. In: Bunnin N., Tsui-James E. P. (eds) The Blackwell companion to philosophy, 2nd ed Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 725–740. [Google Scholar]

- Benner P., Wrubel J. (1989) The primacy of caring: Stress and coping in health and illness, Menlo Park, CA: Addison Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Bentham J. (1907) Introduction to the principles of morals and legislation, Oxford, England: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bliss S., Baltzly D., Bull R., Dalton L., Jones J. (2017) A role for virtue in unifying the ‘knowledge’ and ‘caring’ discourses in nursing theory. Nursing Inquiry 24(4): e12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottorff J. (1991) Nursing: A practical science of caring. Advances in Nursing Science 14: 26–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden P. (2000) An ‘ethic of care’ in clinical settings: Encompassing ‘feminine’ and ‘feminist’ perspectives. Nursing Philosophy 1: 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Brody J. (1988) Virtue ethics, caring and nursing. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice 2(2): 87–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. (1977) Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist 32: 513–531. [Google Scholar]

- Childress J., Faden R., Gaare R., Gostin L., Kahn J., Bonnie R., Nieburg P. (2002) Public health ethics: Mapping the terrain. The Journal of Law and Medical Ethics 30: 170–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein B., Turner M. (2015) The nursing code of ethics: Its value, its history. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 20(2): 33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry S. (1989) The role of caring in a theory of nursing ethics. Hypatia 4(2): 88–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow S. (1999) Relational narratives: The postmodern turn in nursing ethics. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice 13: 57–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan C. (1982) In a different voice: Psychological theory and women's development, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Held V. (2006) The ethics of care: Personal, political, and global, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hippocratic Oath. (n.d.). Encyclopedia Brittanica online. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hippocratic-oath.

- Horner C., Westacott E. (2000) Thinking through philosophy, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- International Council of Nurses. (n.d.). Nursing definitions. Retrieved from https://www.icn.ch/nursing-policy/nursing-definitions.

- Jagger A. (1992) Feminist ethics. In: Becker L., Becker C. (eds) Encyclopedia of ethics, New York, NY: Garland Press, pp. 363–364. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R., & Cureton, A. (2018). Kant's moral philosophy. In E. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/cgibin/encyclopedia/archinfo.cgi?entry=kant-moral.

- Liaschenko J. (1993) Feminist ethics and cultural ethos: Revisiting a nursing debate. Advances in Nursing Science 15: 71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutzen K., Barbosa da Silva A. (1996) The role of virtue ethics in psychiatric nursing. Nursing Ethics 3: 202–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy J. (2006) A pluralist view of nursing ethics. Nursing Philosophy 7: 157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, T. (2014). Moral dilemmas. In E. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/cgi-bin/encyclopedia/archinfo.cgi?entry=moral-dilemmas.

- Mill J. (2002) On liberty, Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale F. (1992) Notes on nursing, Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott Company. [Google Scholar]

- Noddings N. (1984) Caring: A feminine approach to ethics and moral education, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nurse. (n.d.). In Merriam Webster online. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/nurse.

- Paley J. (2002) Caring as a slave morality: Nietzschean themes in nursing ethics. Journal of Advanced Nursing 40: 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rest J. (1986) Moral development: Advances in research and theory, New York, NY: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts M., Reich M. (2002) Ethical analysis in public health. Lancet 359: 1055–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellman D. (1997) The virtues in the moral education of nurses: Florence Nightingale revisited. Nursing Ethics 4(1): 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarlier D. (2004) Beyond caring: The moral and ethical bases of responsive nurse-patient relationships. Nursing Philosophy 5: 230–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (2018) Ethical and Religious Directives for catholic health care services, 6th ed Washington, DC: Author. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson Caring Science Institute. (n.d.). About WCSI. Retrieved from https://www.watsoncaringscience.org/about-wcsi/.