Abstract

Introduction

The rising prevalence of dementia has led to increased numbers of people with dementia being admitted to acute hospitals. This demand is set to continue due to an increasingly older population who are likely to have higher levels of dependency, dementia, and comorbidity. If admitted to the hospital, people with dementia are at higher risk of poor outcomes during and following a hospital admission. Yet, there remains a significant lack of specialist support within acute hospitals to support people with dementia, their families and hospital staff.

Methods

Admiral Nurses are specialists that work with families affected by dementia and provide consultancy and support to health and social care colleagues to improve the delivery of evidenced based dementia care. Historically, Admiral Nurses have predominantly been based in community settings. In response to the increasing fragmentation of services across the dementia trajectory, the Admiral Nurse model is evolving and adapting to meet the complex needs of families impacted upon by dementia inclusive of acute hospital care.

Results

The Admiral Nurse acute hospital model provides specialist interventions which improve staff confidence and competence and enables positive change by improving skills and knowledge in the provision of person-centred dementia care. The role has the capacity to address some of the barriers to delivering person centred dementia care in the acute hospital and contribute to improvements across the hospital both as a result of direct interventions or influencing the practice of others.

Conclusion

Improving services for people with dementia and their families requires a whole system approach to enable care coordination and service integration, this must include acute hospital care. The increasing numbers of people with dementia in hospitals, and the detrimental effects of admission, make providing equitable, consistent, safe, quality care and support to people with dementia and their families a national priority requiring immediate investment. The inclusion of Admiral Nursing within acute hospital services supports service and quality improvement which positively impacts upon the experience and outcomes for families affected by dementia.

Keywords: acute hospital, dementia, admiral nursing, specialist nursing

Background

The UK population is ageing. In 2007 approximately 16% of the UK population were aged 65 years or over compared with just over 18% in 2017 this % is projected to grow to almost 21% by 2027 according to the Office of National Statistics (ONS; 2018a). Similarly, the number of people over 85 will increase to 3.2 million by 2041 which will equate to 4% of the total population; this will place further pressure on already struggling resources (ONS,2018b). There will be increasing numbers of people with complex care needs, due mainly to this increasingly older population who are likely to have higher levels of dependency, dementia, and comorbidity (Kingston et al., 2018). Increased age is the highest risk factor for developing dementia (Alzheimer’s Disease International [ADI], 2014).

Dementia

It is estimated there are currently 850,000 people living with dementia in the UK and, if current estimates relating to incidence and prevalence are realised, this will increase to 1 million people by 2025 and 2 million by 2051 (Prince et al., 2014). The rising prevalence of dementia has led to a greater number of people with dementia being admitted to an acute hospital (Sleeman et al., 2015: Department of Health [DOH], 2009), with figures ranging from 29% to 42% in adults over the age of 70 years (Timmons et al., 2016). It is estimated that 6% of the total number of people affected by dementia are in acute care at any one time (Briggs et al., 2017).

Comorbidity and Dementia

People aged over 65 living with dementia have an average of four comorbidities, whereas people without dementia have on average two (Poblador-Plou et al., 2014), including conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, chronic cardiac failure, hypertension, vascular or heart disease and musculoskeletal disorders (Browne et al., 2017; Bunn et al., 2016; Fox et al., 2014). However, the true extent of comorbidities experienced by people with dementia may remain underestimated due to the difficulties people living with dementia often have in reporting symptoms (Page et al., 2018).

Comorbidity and multimorbidity present real challenges to health care as often systems are in place that promote the management and or monitoring of singular disease processes rather than considering the impact of one condition on another. This can lead to an effect called diagnostic overshadowing, that is to say symptoms are attributed to one of a person’s conditions (such as dementia or mental illness) as opposed to being seen as the result of a wider interaction with another co-morbidity (Voss et al., 2017). Dementia and coexisting comorbid conditions often interact, causing either complication with treatment, or, an acceleration or exacerbation of one of the disease trajectories (Page et al., 2018). As a result, there is an increased likelihood of an acute hospital admission for people with dementia and comorbid conditions compared to people with the same comorbid conditions without dementia (DOH, 2016).

Frailty and Dementia

There is growing evidence regarding the relationship between frailty and dementia. Frailty describes a condition in which multiple body systems gradually lose their in-built reserves and resilience (Chen et al., 2014). Frailty is often present in people who also have a diagnosis of dementia or cognitive impairment, particularly in people over 75 years (Kulmala et al., 2014). The presence of frailty is associated with increased poor health outcomes (Barclay et al., 2014). The delayed provision of healthcare and support can lead to an increased risk of unplanned hospital admissions, institutionalisation, morbidity and mortality in this population (ADI 2016; Buckinx et al., 2015; Keeble et al., 2019; Turner & Clegg, 2014; World Health Organization [WHO], 2016).

Acute Hospital Admissions

With such a background of complexity, if admitted to the hospital, people with dementia are at higher risk of poor outcomes during, and following a hospital admission (ADI 2016). Poor outcomes include delirium, falls, reduced mobility, incontinence, functional decline, mortality, longer length of stay, reduced quality of life, and increased likelihood of discharge to residential care compared to those without dementia or cognitive impairment (Fogg et al., 2017; George et al., 2013; Sampson et al., 2009; Timmons et al., 2015). Due to the increasing numbers of people with dementia in hospitals, the variation in the symptoms, and the impact of any comorbid conditions, providing consistent, good quality care and support to people with dementia in acute hospitals is complex (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], 2018). This creates challenges for acute hospital clinicians and for service capacity, in relation to the coordination of care and support for people with dementia, alongside assessing and managing the needs of carers (NICE, 2018).

People with dementia are not generally admitted to a hospital due to the dementia condition itself, so dementia is rarely the care or treatment priority (Timmons et al., 2016). Around 43% of unplanned hospital admissions for people with dementia are due to sentinel events superimposed upon the dementia, such as, pneumonia and urinary tract infections (Sampson et al., 2009). It must also be noted that many people admitted to an acute hospital may be living with dementia but as yet have received no formal diagnosis (Fogg et al., 2017; Timmons et al., 2015). Despite the national diagnosis rate target of 66.7% being reached, there remains significant local variations which can range from 42.6% to 90.3% (National Health Service Digital, 2019).

Policy

Given the aging population and the increasing demand this places upon health and social care services, UK policy aims to increase the provision and delivery of proactive community-based care, supporting people to live at home or in sheltered housing for as long as possible (NHS 2019; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD], 2018). However, this is problematic when there are limited services available to meet the demand in the community given the reduced numbers of community hospital beds, community nurses and General Practitioners (GP) on top of a general paucity of dementia specific resources (NHS 2019; Care Quality Commission [CQC], 2014). Such a proposed shift from reliance on acute hospital care to a community-based response, will require a radical redesign of community versus acute hospital services and resources.

The National Health Service Long Term Plan (NHS, 2019) intends to move services ‘closer to home’ and improve ‘out of hospital’ care. The overall aims are to (1) reduce the pressure on acute hospital resources, (2) give people more control over their health, and (3) provide more personalised care. The Long Term Plan (NHS, 2019) also places emphasis on improving discharge processes following a hospital admission and reducing the length of stay. Such an approach has the potential to reduce the impact of deconditioning and other negative events for people with dementia within the acute setting. People with dementia are at higher risk of deconditioning and subsequent discharge to a care home than the equivalent aged population without cognitive impairment (Fogg et al., 2017; Timmons et al., 2015). Deconditioning is a complex process of physiological change following a period of inactivity which can result in functional losses in areas such as, further compromised mental status, reduced degree of continence, reduced ability to accomplish activities of daily living and is often linked to frailty and increased risk of falls (Gillis & MacDonald, 2005).

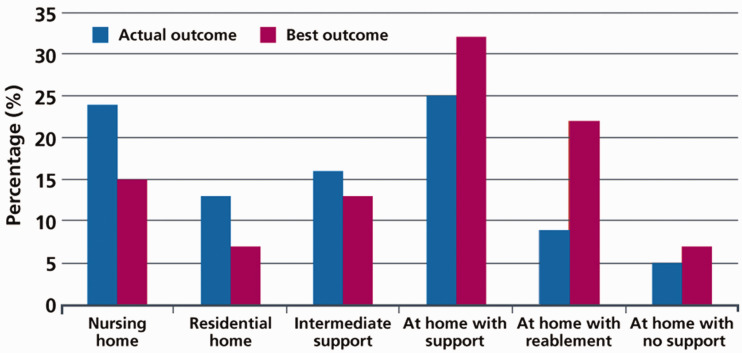

Reducing a person’s length of stay can limit the effects of deconditioning, improving opportunities to discharge people with dementia to the most clinically appropriate setting; an area that requires improvement (NHS, 2019) (see Figure 1). Such aims place emphasis on improved integration between primary, community and intermediate care services that are responsive and promote preventative or primary care-based interventions before a situation becomes critical, thus, reducing the risk of avoidable hospital admissions.

Figure 1.

Where People Are Discharged vs Where Would Be Best (NHS, 2019, p. 23. Source Newton Europe).

Acknowledging the detrimental effects an acute hospital admission can pose for a person with dementia, their family and the wider health and social care systems, has made appropriate, person centred, quality care for this population a worldwide public health priority (Prince et al., 2016: WHO, 2015). It is recognised that current processes and practices are financially costly to the healthcare system (Prince et al., 2016). In addition to the increased length of stay for people with dementia, due to their complex needs, they often require more nursing resources which increases the cost of their hospital care (ADI, 2016). Consequently, dementia strategies in many countries, including Scotland, England, Northern Ireland, Wales and Australia (Table 1), have identified that improving acute hospital dementia care is a key objective not only for the person with dementia, but also their family carers (NICE, 2018; NHS, 2019).

Table 1.

Examples of National Strategies inclusive of Acute Care.

| Country | Strategy document | Available at: |

|---|---|---|

| Scotland (Scottish Government, 2017) | National Dementia strategy: 2017–2020 | https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-national-dementia-strategy-2017-2020/ |

| England | Prime Ministers Challenge on Dementia 2020 | https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/414344/pm-dementia2020.pdf |

| Northern Ireland | Improving dementia services in Northern Ireland a Regional Strategy 2011 | https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/publications/improving-dementia-services-northern-ireland-regional-strategy |

| Wales (Welsh Government, 2019) | Dementia Action Plan for Wales 2018–2022 | https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2019-04/dementia-action-plan-for-wales.pdf |

| Australia | National framework for Action on Dementia 2015–2019 | https://www.ceafa.es/files/2017/05/AUSTRALIA-1.pdf |

Family Carers of People With Dementia

It is not only the person with dementia that is at increased risk of poor outcomes resulting from an acute hospital admission; the families and carers of people with dementia also have negative experiences. Carers often feel poorly equipped to manage the complex needs of the person they care for. They often assume the role of carer with little, or no understanding of dementia, or its effects on themselves or the person they care for (Aldridge, 2019). There may be perceived benefits for some carers who consider it a rewarding experience that strengthens family bonds through the shared close and intimate relationship (Aldridge, 2019). However, for many, the effects are negative with high rates of perceived burden, social isolation, poor physical and mental health and financial hardship (Brodaty & Donkin, 2009). These effects on carers may be overlooked by acute hospital staff whose role is to focus primarily on the acute medical needs of the patient, in this case the person with dementia. However, failure to acknowledge the family’s needs is short-sighted as family carers are often pivotal to the success, or failure, of the person with dementia being successfully discharged and returned home (Aldridge et al., 2019b).

The expectations of family carers’ may be considered unrealistic by hospital staff, but equally the expectation of hospital staff in relation to the input of family carers, may be equally unrealistic. Such issues are often unexplored which has the potential to increase the risk of discontentment. Jurgens et al. (2012) suggest improved consultation with families could be better addressed through inclusion and proactive communication. However, evidence points to poor outcomes for carers, including poor communication (Bridges et al., 2010), relationship conflict with staff (Whittamore et al., 2014) and cycles of discontent (Jurgens et al., 2012); all of which result in widespread dissatisfaction (Alzheimer’s Society, 2009). Similarly, physical and mental decline, and adverse incidents for the person with dementia, can also lead to increased carer strain and dissatisfaction for families during an admission (George et al., 2013). Discharge planning, inclusive of people with dementia and their carers, needs to be improved (Dewing & Dijk, 2016) as acute hospitals still fail to acknowledge the needs of family carers (Bauer et al., 2014; Dewing & Dijk, 2016). The most recent annual National Audit of Dementia in acute hospitals (Royal College of Psychiatrists [RCP] 2019) identified that while there have been some improvements in the support and inclusion of carers, there is still further work needed to improve communication, discharge planning, carer support and staffs’ understanding of dementia (Thompson et al., 2019).

Barriers and Enablers to Good Quality Care in Acute Hospitals

A plethora of barriers have been identified that thwart the provision of good dementia care in acute hospitals. These is a lack of focus and leadership, inadequate training, difficulties assessing the risks and benefits to treatment, stigma, discrimination, inadequate staffing, unsafe environments, poor clinical pathways and policies (Featherstone et al., 2019; Handley et al., 2017; Houghton et al., 2016; Timmons et al., 2016). This is compounded by the fact that nursing staff are struggling to deliver person-centred dementia care in acute care settings due to the institutional drivers of routine, efficiency, risk management and risk reduction (Featherstone et al., 2019).

The often-complex needs of individuals with dementia suggests that people with dementia require specialised services to provide appropriate clinical management during a hospital admission. Conversely, it has been identified that there is a lack of specialist dementia services and/or practitioners available in hospitals to not only deliver direct care, but to support staff. Such roles could be beneficial in supporting staff to develop their practice and improve the overall quality of acute care provision for people with dementia and their family carers. Enabling positive change to improve the care of people with dementia and their families is complex and requires multifactorial and multi-level approaches (George et al., 2013).

Clinical Expertise in Dementia

Training is often seen as the solution to many of these problems, and it is still acknowledged that there is still much to be achieved in ensuring that the acute hospital workforce is appropriately trained in dementia (RCP 2019). However, there are many more factors that need to be considered. Handley et al. (2017) identifed that changes in dementia practice occur when staff are influenced by those who possess clinical expertise and organisational authority. Such experts in the field can support the implementation of learning, assessment tools and holistic care planning alongside role modeling behaviour and improved communication techniques. Having access to clinical experts in dementia care for advice on complex situations has been identified as a means of reassuring and empowering staff to make changes and improve dementia care in acute hospitals (Handley et al., 2017) which in turn, has the potential to improve outcomes and experiences for people with dementia and their families and carers (George et al., 2013).

Therefore, the need to employ staff with clinical expertise and organisational authority to facilitate positive change to enable the delivery of person-centred dementia care is clearly needed within acute hospital settings (Handley et al., 2017). Such specialist roles can act as the catalyst for positive change, breaking down barriers and enabling improved quality of dementia care in hospitals. Admiral Nurses, specialists in dementia care, are well placed to fill this current gap and influence such change within acute hospital settings.

Admiral Nurses

Admiral Nurses are registered nurses specialising in dementia care who work with families affected by dementia inclusive of the person with dementia and their family carer(s) and are continually trained, developed and supported by the charity Dementia UK.

Admiral Nurses work across traditional service boundaries seeking to the quality of life for people with dementia and their family carers implementing a biopsychosocial approach to dementia care in order to meet their complex needs. Admiral Nurses also provide support specialist advice, support and training to other health and social care professionals.

Admiral Nurses were named by the family of Joseph Levy CBE BEM, who founded the charity now known as Dementia UK. Joseph had vascular dementia and was known affectionately as “Admiral Joe” because of his love of sailing.

Admiral Nursing in Acute Hospitals

Over recent years the model of Admiral Nursing has developed rapidly offering specialist support across health and social care systems, with a more recent development being their introduction into acute hospitals. Admiral Nurses are specialists who work across health and social care systems to deliver care to families affected by dementia who have complex needs. Although Admiral Nurse services can vary; for example. in their composition, funding, remit and care setting; their core principles and values remain the same, with services that focus on supporting families affected by dementia with complex needs (Aldridge et al., 2019a; Gridley et al., 2019).

Dementia UK (The charity that developed Admiral Nursing) identified the need to improve the care and support offered to people with dementia, their families, and staff within acute hospital settings some time ago with the introduction of the first Admiral Nurse to Southampton Hospital in 2012. Over the past three years, there has been a significant increase in Admiral Nurses working in acute hospitals, with Dementia UK currently working in partnership with 20 services, to provide 31 Admiral Nurses within acute care settings across the United Kingdom with 10 further posts in development.

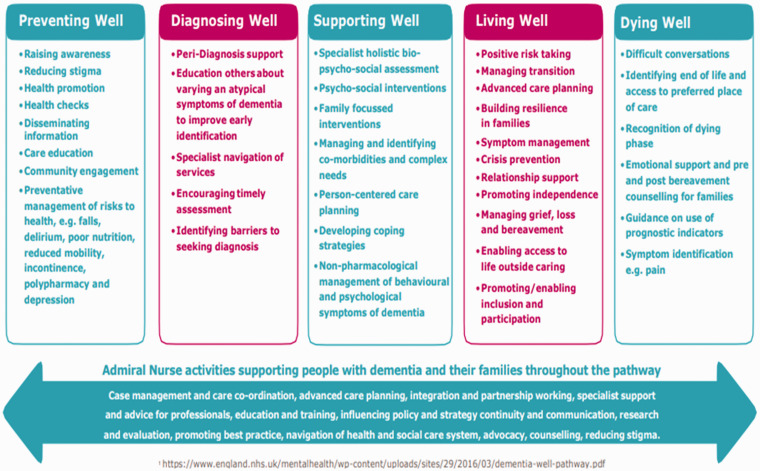

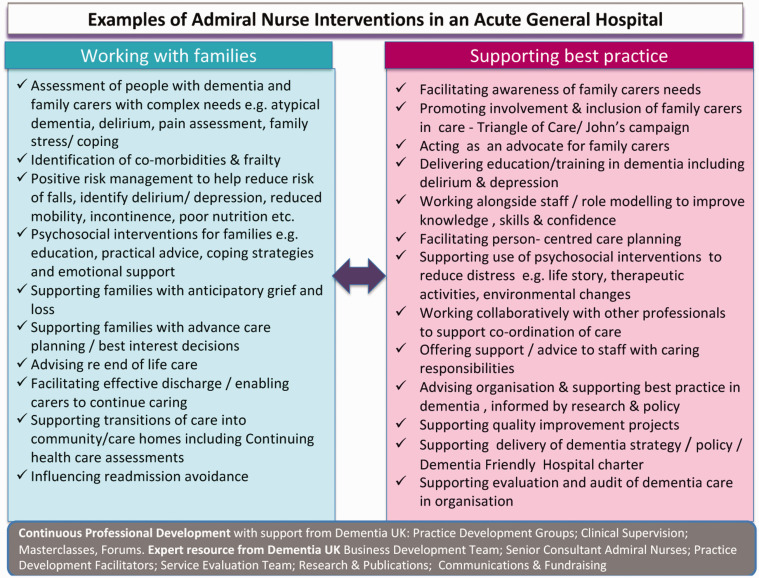

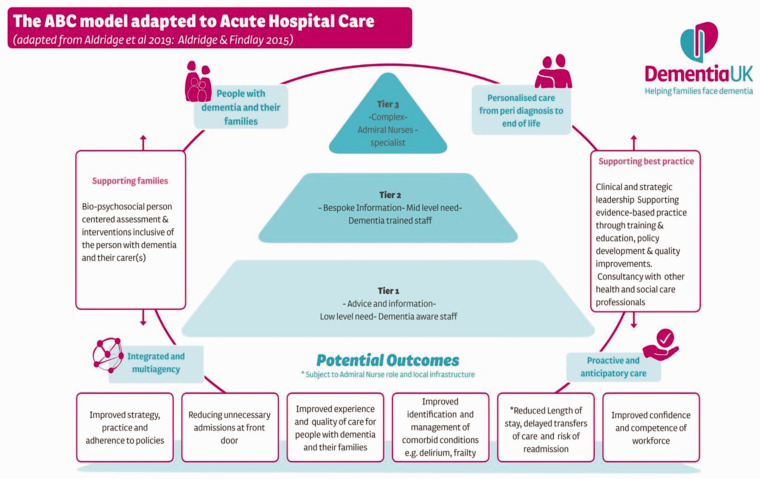

Admiral Nurses provide specialist support to people with dementia and their families from peri diagnosis through to post-bereavement, using a biopsychosocial approach to care (Aldridge & Harrison Dening, 2019) across the NHS Dementia Well Pathway (NHS 2016; Figure 2). The aim of Admiral Nursing services within acute care settings is to optimise the outcomes for families affected by dementia by delivering relationship-centred dementia care and improving the practice of staff across the hospital (Figure 3). Admiral Nurses deliver holistic, person-centred dementia care at a Tier 3 (Figure 4), providing specialist clinical support to families who are facing high levels of complexity underpinned by the 18-point Admiral Nurse Assessment Framework (Harrison Dening, 2010).

Figure 2.

Examples of Admiral Nurse Activities Across the NHS Dementia Well Pathway (NHS 2016).

Figure 3.

Examples of Admiral Nurse Interventions in a Acute General Hospital (Thompson et al., 2019).

Figure 4.

The Admiral Nurse ABC Model in Acute Hospitals (Adapted From Integrated Community Model; Aldridge & Findlay, 2015; ABC Tiered Model; Aldridge et al., 2019a).

Alongside their direct clinical interventions with families, Admiral Nurses provide support, education and consultancy to other health and social care professionals promoting best practice in dementia care. Such an approach builds staff confidence, competence and enables positive change by improving their skills and knowledge in the provision of person-centred dementia care. Admiral Nurses in acute hospital settings are actively involved in strategic design and development of dementia services in hospitals, as well as leading, and supporting audit and evaluation of identified quality improvement initiatives and policy development to improve the delivery of dementia care. Admiral Nurses also work closely with existing services and stakeholders with the aim of supporting reduced fragmentation of service provision across the dementia pathway. This work aims to contribute to a reduction in length of stay, inappropriate admissions, failed discharges and ensuring families get the right support.

Case Study

Lister Admiral Nurse Service

The service comprises of one full time Admiral Nurse working across East and North Hertfordshire NHS Trusts hospital sites and is primarily based at Lister hospital.

Working with Families

Inpatients with dementia and their carers(s) can be referred to the service if they have complex needs. Complex needs may include issues such as the carer struggling to cope, complex family dynamics, high levels of distress, changes in the presentation of the person with dementia, complex decision-making, comorbidities and end of life care. The Lister Admiral Nurse works in collaboration with the community-based Admiral Nurse team delivered by Carers in Herts, this increases the opportunities for families affected by dementia to receive a more cohesive service between acute and community care.

Service evaluation data from Jan 2018 to Dec 2018 demonstrated that the Lister Admiral Nurse had received a total of 214 referrals. Much of the Admiral Nurse’s work involves ‘care at the bedside’ with provision of clinically effective, evidenced based practice and case management of complex cases. This is achieved by delivering and coordinating specialist clinical care and support during highly challenging times in the hospital for families affected by dementia. If complex needs are identified prior to hospital discharge families are referred to the community Admiral Nurse Service for ongoing support or, to other appropriate services proportionate to the level of need as defined within the ABC tiered model (Aldridge et al., 2019a; Figure 4). The ABC tiered model (Aldridge et al., 2019a) was developed to ensure that families affected by dementia could be directed to the right level of support to meet their needs. Mapping services to the model ensures efficient use of services, whilst promoting an integrated model of service provision for peri and post diagnostic dementia support.

Other interventions which directly support families include facilitating family meetings, educating and supporting carers (e.g. Lasting Power of Attorney [DOH], 2005]; John’s Campaign [Gerrard & Jones, 2014]), and advocating on families' behalf by educating staff on families’ needs and preferences for care, and how to identify and manage the person with dementia’s pain.

Supporting Best Practice

In addition to the direct work with families, the Admiral Nurse role within the acute hospital is to provide support, advice, training and development to other members of staff within the Trust. The Admiral Nurse delivered 996 activities during this same period to support best practice in dementia care across the Trust, this equated to 83 activities per month. Two thirds of these activities related to directly advising other health and social care professionals (including nurses, allied healthcare professionals, consultants, healthcare support workers and social workers) across all wards and departments within the hospital on a range of issues including:

person centred dementia care

mental capacity assessments and deprivation of liberty safeguards

managing activities of daily living

pain management

changing and distressed behaviours

the needs of families/carers

palliative care

The Admiral Nurse has also led on developing new pathways for dementia and delirium, dementia strategy meetings and updating policies in relation to dementia and supports the 80 dementia champions (Dementia champions are staff members who seek training above and beyond what is required of them to better support people living with dementia in there are of work and is not limited to clinical roles).

This work of the Admiral Nurse was highlighted by the Care Quality Commission (CQC) report identifying individuals who have made a difference in NHS Trusts (CQC, 2018; Table 2).

Table 2.

CQC Comments in Relation to Lister Admiral Nurse (CQC 2018).

| “This has proved vital in ensuring families feel supported and reducing carer breakdown. A dementia care pathway and a delirium pathway were launched by (the Admiral Nurse) within the Trust in 2018. They are a guide to help staff deliver good dementia care and help identify and raise awareness of delirium. The dementia care pathway is easy to read and covers identifying confusion; involving families; raising awareness; documentation and assessment; care on wards considering referrals and discharge from hospital ….it is in line with the trusts dementia policy …… |

| (The Admiral Nurse) provides tier two training on a monthly basis for all staff who have regular contact with someone living with dementia. This helps raise their knowledge and skills for someone caring with dementia, along with the ability to educate and support families. All the changes introduced by (the Admiral Nurse) have helped improve the experience of a hospital admission for people with dementia and their families” |

During the 12-month evaluation period, 436 staff received Tier 1 Dementia awareness training (Skills for Health, 2018) delivered by the Admiral Nurse. A post training questionnaire was given to all participants, 95% of participants reported the training had improved their confidence, and 93% reported the training had improved their skills when working with people with dementia. Free text responses were encouraged within the questionnaires and following data analysis the key themes arising from staff feedback regarding what they would do differently as a result of undertaking Tier 1 training were;

Refer to appropriate services

Provide appropriate information and support to families

Consider the needs of the family

Increased awareness of dementia symptoms

A further 56 staff were trained at Tier 2 (Skills for Health, 2018) with participants completing a post training questionnaire in which they reported their knowledge of ‘key legislation relevant to dementia care’ and how to ‘implement a person-centred approach to care’ had increased. There were several key themes arising from free text feedback within the questionnaires in relation to what they would now do differently as a result of the training;

Demonstrate greater understanding to people with dementia

Apply a personalised approach

Provide more time to people with dementia and their families

Encourage completion of ‘This is Me’ (‘This is Me’ is a document produced by the Alzheimer’s Society to help hospital staff better understand the needs of people with dementia.)

Ensure effective pain identification and management

Consider the needs of the family/carer(s)

The Admiral Nurse also supports student nurse induction by raising awareness of the needs of people with dementia.

Although a relatively new adaptation of the Admiral Nurse role, this case study demonstrates some of the benefits of the Admiral Nurse model when applied to the acute hospital setting. The role has capacity to address some of the barriers to delivering person centred dementia care in the acute hospital and contribute to improvements across the hospital, both as a result of direct interventions or by influencing the practice of others.

Conclusion

Continually increasing numbers of people with dementia in hospitals, and the significant detrimental impact of an admission, make the provision of equitable, consistent, safe, good quality care and support to people with dementia and their families in hospital an international priority which requires immediate attention and investment. Training is only one part of the solution.

Specialist clinicians such as Admiral Nurses should be seen as an essential, not optional component of dementia service provision to meet the complex needs of people with dementia and their family/carer(s) across all settings inclusive of acute hospitals to address some of the deficits in care that currently exist.

By stepping away from the medical model of nursing and providing a biopsychosocial approach to dementia care within acute hospitals Admiral Nurses deliver interventions which positively impacts upon the experience and outcomes for families affected by dementia, but also their fellow hospital staff as they become more confident and competent in their own practice . This approach and model of care are easily transferable and could be adapted to other healthcare systems outside of the UK. More research into the benefits of such interventions is required and would be welcomed.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Zena Aldridge https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5982-8070

References

- Aldridge Z. (2019). Chapter 16. Supporting families and carers of people with dementia In Harrison Dening K. (Ed.), Evidence-Base practice I dementia for nurses and nursing students (pp. 212–222). Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge Z., Findlay N. (2015, September 2–4). Norfolk admiral nurse pilot: An evaluation report [Paper presentation], PO3.74. Alzheimer’s Europe Conference, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

- Aldridge Z., Harrison Dening K. (2019). Admiral nursing in primary care: Peri and post-diagnostic support for families affected by dementia within the UK primary care network model. OBM Geriatrics, 3(4), 16 10.21926/obm.geriatr.1904081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge Z., Burns A., Harrison Dening K. (2019. a). ABC model: A tiered, integrated pathway approach to peri-and post-diagnostic support for families living with dementia (innovative practice). Dementia, 147130121983808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge Z., Davies V., Harrison Dening K. (2019. b). Admiral nursing: Supporting families affected by dementia within a holistic intermediate care team. British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 15(5), 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. (2014). World Alzheimer, Report 2014: Dementia and risk reduction https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2014.pdf

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. (2016). World Alzheimer, Report 2016: Improving healthcare for people living with dementia. Coverage, quality and costs now and in the future https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2016.pdf

- Alzheimer’s Society. (2009). Counting the cost http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?fileID=787

- Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council. (2015). National Framework for Action on Dementia 2015–2019 https://www.ceafa.es/files/2017/05/AUSTRALIA-1.pdf

- Barclay S., Froggatt K., Crang C., Mathie E., Handley M., Iliffe S., Manthorpe J., Gage H., Goodman C. (2014). Living in uncertain times: Trajectories to death in residential care homes. British Journal of General Practice, 64(626), e576–e583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer K., Schwarzkopf L., Graessel E., Holle R. (2014). A claims data-based comparison of comorbidity in individuals with and without dementia. BMC Geriatrics, 14, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges J., Flatley M., Meyer J. (2010). Older people’s and relatives’ experiences in acute care settings: Systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(1), 89–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs R., Dyer A., Nabeel S., Collins R., Doherty J., Coughlan T., O'Neill D., Kennelly S. P. (2017). Dementia in the acute hospital: The prevalence and clinical outcomes of acutely unwell patients with dementia. QJM: Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians, 110(1), 33–37. 10.1093/qjmed/hcw114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H., Donkin M. (2009). Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clinical Neuroscience, 11(2), 217–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne J., Edwards D. A., Rhodes K. M., Brimicombe D. J., Payne R. A. (2017). Association of comorbidity and health service usage among patients with dementia in the UK: A population-based study. BMJ Open, 7(3), e012546 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckinx F., Rolland Y., Reginster J.-Y., Ricour C., Petermans J., Bruyère O. (2015). Burden of frailty in the elderly population: Perspectives for a public health challenge. Archives of Public Health, 73(1), 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn F., Goodman C., Pinkney E. (2016). Specialist nursing and community support for the carers of people with dementia living at home: An evidence synthesis. Health and Social Care in the Community, 24(1), 48–67. 10.1111/hsc.12189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Care Quality Commission. (2014). Cracks in the pathway https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20141009_cracks_in_the_pathway_final_0.pdf

- Care Quality Commission. (2018). Driving improvement – individuals who have made a difference in NHS trusts https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20180706_drivingimprovementnhs70_acute.pdf

- Chen X., Mao G., Leng S. X. (2014). Frailty syndrome: An overview. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 9, 433–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. (2005). Mental capacity act. HMSO. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. (2009). Living well with dementia: A national dementia strategy. Crown Publications.

- Department of Health. (2016). Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia 2020: Implementation plan https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/challenge-on-dementia-2020-implementation-plan

- Dewing J., Dijk S. (2016). What is the current state of care for older people with dementia in general hospitals? A literature review. Dementia (London, England), 15(1), 106–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone K., Northcott A., Bridges J. (2019). Routines of resistance: An ethnography of the care of people living with dementia in acute hospital wards and its consequences. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 96, 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogg C., Meredith P., Bridges J., Gould G. P., Griffiths P. (2017). The relationship between cognitive impairment, mortality and discharge characteristics in a large cohort of older adults with unscheduled admissions to an acute hospital: A retrospective observational study. Age and Ageing, 46(5), 794–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox C., Smith T., Maidment I., Hebding J., Madzima T., Cheater F., Cross J., Poland F., White J., Young J. (2014). The importance of detecting and managing comorbidities in people with dementia? Age and Ageing, 43(6), 741–743. 10.1093/ageing/afu101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George J., Long S., Vincent C. (2013). How can we keep patients with dementia safe in our acute hospital’s? A review of challenges and solutions. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 106(9), 355–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard N., Jones J. (2014). John’s campaign for the right to stay with people with dementia, for the right of people with dementia to be supported by family carers https://johnscampaign.org.uk/#/

- Gillis A., MacDonald B. (2005). Deconditioning in the hospitalized elderly. The Canadian Nurse, 101(6), 16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridley K., Aspinal F., Parker G., Weatherly H., Faria R., Longo F., van den Berg B. (2019). Specialist nursing support for unpaid carers of people with dementia: A mixed methods feasibility study. Health Services and Delivery Research, 7(12), 1–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handley M., Bunn F., Goodman C. (2017). Dementia friendly interventions to improve the care of people living with dementia admitted to hospitals: A realist review. BMJ Open, 7(7), e015257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison Dening K. (2010). Admiral nursing: Offering a specialist nursing approach. Dementia Europe, 1, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton C., Murphy K., Brooker D., Casey C. (2016). Healthcare staffs’ experiences and perceptions of caring for people with dementia in acute setting: Qualitative evidence synthesis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 61, 104–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurgens F. J., Clissett P., Gladman J. R., Harwood R. H. (2012). Why are family carers of people with dementia dissatisfied with general hospital care? A qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics, 12(1), 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeble E., Parker S. G., Arora S., Neuberger J. (2019). Frailty, hospital use and mortality in the older population: Findings from the Newcastle 85+ study. Age and Ageing, 48, 797–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston A., Robinson L., Booth H., Knapp M., Jagger C.; MODEM Project. (2018). Projections of multi-morbidity in the older population in England to 2035: Estimates from the population ageing and care simulation (PACSim) model. Age and Ageing, 47(3), 374–380. 10.1093/ageing/afx201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulmala J., Nykänen I., Mänty M., Hartikainen S. (2014). Association between frailty and dementia: A population-based study. Gerontology, 60(1), 16–21. 10.1159/000353859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service Digital. (2019, October). Recorded dementia diagnosis https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/recorded-dementia-diagnoses/october-2019

- National Health Service. (2016). NHS England Transformation Framework—The well pathway for dementia https://www.england.nhs.uk/mentalhelath/wp-content/uploads/sites/29/2016/03/dementia-well-pathway.pdf

- National Health Service. (2019). NHS long term plan https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/nhs-long-term-plan-june-2019.pdf

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. ( 2018). NICE Guideline NG97 Dementia: Assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97 [PubMed]

- Northern Ireland Department of Health. (2011). Improving dementia services in Northern Ireland —A regional strategy https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/publications/improving-dementia-services-northern-ireland-regional-strategy

- Office of National Statistics. (2018. a). Overview of the UK population: November 2018 An overview of the UK: How its changed, why it’s changed and how its projected to change in the future. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/overviewoftheukpopulation/november2018 [Google Scholar]

- Office of National Statistics. (2018. b). Living longer: How our population is changing and why it matters overview of population ageing in the UK and some of the implications for the economy, public services, society and the individual . https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/ageing/articles/livinglongerhowourpopulationischangingandwhyitmatters/2018-08-13#how-is-the-uk-population-changing

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2018). Care needed: Improving the lives of people with dementia. OECD health policy studies. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Page A., Etherton-Beer C., Seubert L. J., Clark V., Hill X., King S., Clifford R. M. (2018). Medication use to manage comorbidities for people with dementia: A systematic review. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research, 48(4), 356–367. [Google Scholar]

- Poblador-Plou B., Calderón-Larrañaga A., Marta-Moreno J., Hancco-Saavedra J., Sicras-Mainar A., Soljak M., Prados-Torres A. (2014). Comorbidity of dementia: A cross-sectional study of primary care older patients. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 84 10.1186/1471-244X-14-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M., Comas-Herrera A., Knapp M. (2016). World Alzheimer report 2016: Improving healthcare for people living with dementia: Coverage, quality and costs now and in the future. Alzheimer’s Disease International. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/67858/1/Comas-Herrera_World%20Alzheimer%20report_2016.pdf

- Prince M., Knapp M., Guerchet M., McCrone P., Prina M., Comas-Herrera A. (2014). Dementia UK: Second edition-overview. Alzheimer’s Society.

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2019). National Audit of Dementia Care in General Hospitals: Round four audit report https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/improving-care/ccqi/national-clinical-audits/national-audit-of-dementia

- Sampson E. L., Blanchard M. R., Jones L., Tookman A., King M. (2009). Dementia in the acute hospital: Prospective cohort study of prevalence and mortality. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 195(1), 61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Government. (2017). National Dementia Strategy 2017–2020. https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-national-dementia-strategy-2

- Skills for Health. (2018). Dementia core skills education and training framework https://www.skillsforhealth.org.uk/services/item/176-dementia-core-skills-education-and-training-framework

- Sleeman K., Davies J., Verne J., Gao W., Higginson I. (2015). The changing demographics of inpatient hospice death: Population-based, cross-sectional study in England, 1993-2012. Lancet, 385 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S93. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60408-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R., Gilby J., O’Connor C. (2019). The role of the admiral nurse in supporting the dementia friendly hospital charter. Journal of Dementia Care, 27, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Timmons S., Manning E., Barrett A., Brady N. M., Browne V., O’Shea E., Molloy D. W., O’Regan N. A., Trawley S., Cahill S., O'Sullivan K., Woods N., Meagher D., Ni Chorcorain A. M., Linehan J. G. (2015). Dementia in older people admitted to hospital: A regional multi-hospital observational study of prevalence, associations and case recognition. Age and Ageing, 44(6), 993–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons S., O’Shea E., O’Neill D., Gallagher P., de Siún A., McArdle D., Gibbons P., Kennelly S. (2016). Acute hospital dementia care: Results from a national audit. BMC Geriatrics, 16(1), 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner G., Clegg A. (2014). Best practice guidelines for the management of frailty: A British geriatrics society, age UK and royal college of general practitioners report. Age and Ageing, 43(6), 744–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss S., Black S., Brandling J., Buswell M., Cheston R., Cullum S., Kirby K., Purdy S., Solway C., Taylor H., Benger J. (2017). Home or hospital for people with dementia and one or more other multimorbidities: What is the potential to reduce avoidable emergency admissions? The HOMEWARD project protocol. BMJ Open, 7(4), e016651. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh Government. (2019). Dementia action plan for Wales https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2019-04/dementia-action-plan-for-wales.pdf

- Whittamore K. H., Goldberg S. E., Bradshaw L. E., Harwood R. H.; Medical Crises in Older People Study Group. (2014). Factors associated with family caregiver dissatisfaction with acute hospital care of older cognitively impaired relatives. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 62(12), 2252–2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2015). Dementia: A public health priority http://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/en/

- World Health Organization. (2016). WHO Clinical Consortium on Health Ageing Topic focus: Frailty and intrinsic capacity http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272437/WHO-FWC-ALC-17.2-eng.pdf?ua=1