Abstract

A qualitative case study protocol for an exploration of the transition to practice of new graduate nurses in long-term care is presented. For the new graduated nurse, the transition to professional practice is neither simple nor easy. This time of transition has been examined within the hospital setting, but little work has been done from the perspective and context of long-term care. As the global population continues to age and the acuity of persons accessing services outside of hospital continues to increase, there is a need to better understand the transition experience of new graduate nurses in alternative, tertiary settings such as long-term care. Therefore, the purpose of this report is to situate a study and describe a protocol that explored the transition to practice experience of seven new graduate nurses in long-term care using Yin’s case study methodology. The case or phenomenon being explored is new graduate nurse transition to practice. This report presents an overview of the literature in order to situate and describe the case under study, a thorough description of the binding of the case as well as the data sources utilized, and ultimately reflects upon the lessons learned using this methodology. The lessons learned include challenges related to precise case binding, the role and importance of context in conducting case study research, and difficulties in disseminating study findings. Overall, this report provides a detailed example of the application of the case study design through description of a study protocol in order to facilitate learning about this complex and often improperly utilized study design.

Keywords: case study research, protocol, qualitative research, graduate nurse, long-term care, Registered Practical Nurse, Registered Nurse, clinical practice nursing research, transition to practice

Introduction

Due to a predicted global health workforce shortage in the coming decades (Campbell et al., 2013; Canadian Institute for Health Information [CIHI], 2015), the establishment of programs that support the transition to practice of new graduate nurses (NGNs) has been accelerated (Rush & Adamack, 2013). Coupled with an aging population and an increasing acuity of persons receiving health care, the hiring of NGNs of both nursing designation (i.e., Registered Nurses [RNs] and Registered Practical Nurses [RPNs]) into all health-care settings is a strategy utilized to offset these pressures. Although there is a significant body of literature exploring the transition to practice experience in acute-care, hospital-based settings (Baumann, Hunsberger, Crea-Arsenio, & Rizk, 2015; Beaty, Young, Slepkov, Issac, & Matthews, 2009; Duchscher, 2008, 2009), the transition to practice experience for NGNs in long-term care (LTC) remains unknown. This report presents the protocol for a qualitative case study design that explored the transition to practice experience of NGNs employed in LTC in Ontario, Canada.

Background

Aligned with documented demographic trends, the number of people residing in LTC in Canada continues to increase as does the acuity of the care provided and required (Canadian Nurses Association [CNA], 2008; Giallonardo, Wong, & Iwasiw, 2010). Due to Canadian provincial aging-in-place strategies, older adults entering LTC are older, more frail, and in need of greater medical and personal care than ever before (Canadian Medical Association, 2016). In Ontario, approximately 85% of residents require extensive help with activities of daily living including toileting and eating, 90% have some type of cognitive impairment, and 40% require monitoring for an acute medical condition (Ontario Long Term Care Association, 2018).

In LTC, a large proportion of the staff team employed includes nursing staff, of which RNs and RPNs are both represented with RPNs comprising the majority of the regulated health-care workers largely due to funding restrictions (Canadian Healthcare Association [CHA], 2009; CNA, 2011). These RNs and RPNs, further described within the case definitions, each independently and collaboratively fulfill and manage the diverse and variable care needs of the residents served (CHA, 2009; CNA, 2011). In LTC, the level of care provided by nursing staff is influenced by staffing ratios, educational opportunities, as well as regulation and funding models to support nursing staff (CHA, 2009; CNA, 2008; Robertson, Higgins, Rozmus, & Robinson, 1999). Mirroring the acute-care setting (Baxter, 2007), there is no standardized orientation or training for newly hired nurses in LTC, placing NGNs (RN and RPN) at risk both personally and professionally while negatively impacting patient safety and the quality of care (Baxter, 2010).

LTC homes comprise 55% of the total health-care employer organizations in Ontario; however, only 14% of LTC organizations participate in formal new graduate transition programs (Baumann et al., 2015). This lack of participation in programs designed to ease transition to professional practice may challenge the NGN, especially considering the fact that LTC homes are highly autonomous settings where both RNs and RPNs practice with a high level of independence (Ferguson-Pare, 1995). Understanding the experience of NGNs and their transition to practice within the context of LTC is also important in light of the increasing acuity of patients receiving care in LTC, and a national trend displaying that more nurses are leaving the profession—related to various personal and professional variables inclusive of poor transitioning to practice—than those who are entering it (CHA, 2009; CIHI, 2015; Giallonardo et al., 2010). In fact, it is estimated that between 33% and 61% of new nurses across North America change their initial place of employment or express plans to leave the nursing profession altogether within the first year of practice (Duchscher, 2009). Retention strategies, highlighted in literature related to magnet hospitals, have described and demonstrated the importance of strong orientation and mentorship programming. In planning for project demographic shifts and the resulting need for more nurses in LTC, understanding the experience transitioning into practice in LTC settings in context is paramount.

Objectives

The purpose of this report is to describe the protocol for a case study that explored the transition to practice experience of NGNs in LTC. To date, true to design qualitative case study protocols have been largely absent from the literature. This report, through description of a qualitative case study protocol related to NGN transition to practice in LTC, will offer learning about this complex and often improperly utilized study design. The following sections will provide a description of the design, propositions, the case under study, the data collection and analysis strategies, as well as a reflection on the lessons learned using the case study methodology.

Case Study Design

Yin’s (2014) qualitative case study design, and more specifically, the explanatory case study design with embedded units, was most appropriate for this research described protocol. This was because of the need for study propositions to guide the research within the gaps in the available literature and the opportunity for embedded analysis of the distinct nursing designations within the same phenomenon and context. In this report, context refers to the real-life influence of complex concepts including that from social, physical, and temporal realms (Yin, 2014). Yin’s case study design is an empirical, stand-alone research approach that employs the use of rigor, encourages the development of propositions to guide the study, offers guidance in framing the question, and utilizes an inductive strategy for data analysis (Yazan, 2015; Yin, 2014). In selection of the most appropriate case study approach, consideration of the research question was emphasized. In this section, the various components of the case study design, including the propositions, the research questions, the selection of the specific case study design, and the case and its binding are described.

Propositions

Rather than using hypotheses, which are typical in quantitative research designs, Yin recommends the use of propositions. Although similar in that both propositions and hypotheses provide guidance for a study, these concepts differ in purpose. Propositions are not intended to be confirmed or refuted based on the evidence. Rather, they are considered a strategy to bind the study. This binding means to ensure that the study remains reasonable in scope. In addition, propositions are intended to inform the research questions, inform the analysis, and ensure a thorough exploration of the phenomenon of interest. Yin’s case study approach recommends the use of propositions as conceptual framing for the study. Propositions arise from several sources: (a) the literature review, (b) researcher personal experiences, and (c) theories or models (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Yin, 2014). These propositions served as an initial and preliminary conceptual framework.

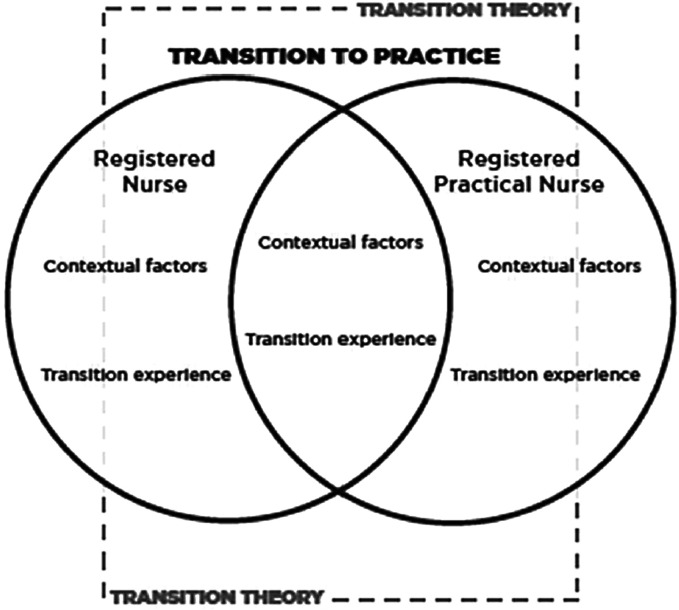

In this described protocol, propositions were developed from the available literature, and more specifically, from transition to practice theory related to the acute-care hospital setting (Benner, 1982; Duchscher, 2008, 2009). Three propositions were developed: (a) transition to practice would be experienced similar to that described in previous studies of NGNs in the acute-care setting (Benner, 1982; Duchscher, 2008, 2009), (b) the context of LTC would influence the NGN and their transition to practice experience, and (c) the transition to practice experience of the RN and RPN new graduate would share similarities based upon the influence of professional context and the required resident care as well as differences based upon variable education and perceived roles and responsibilities within care provision (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Initial conceptual framework.

Research Questions

Developed from the literature review and the propositions, the research questions included: (a) How do new graduate RNs and RPNs working in LTC in Southwestern Ontario describe their experience of transitioning into practice? (b) What contextual factors influence this experience? and (c) How, if at all, does this experience differ according to nursing designation?

Explanatory Single Qualitative Case Study Design

This explanatory qualitative case study, containing one single typical case, aimed to uphold the external validity of the transition to practice experience. As described by Yin (2014), a typical case study design is utilized to capture and describe the conditions of a common situation—such as the transition to practice of NGNs. This typical single-case design ensured representativeness of a typical LTC home, with similar staffing structure and patient care ratios to that of the average LTC home in Ontario. The context, which is of two LTC homes, was meant to bind and influence the case but not the phenomenon of interest.

An explanatory case study was selected for this described protocol as it met the three conditions outlined by Yin (2014). These included that the research sought to explain a “how” or “why” question related to the phenomenon of interest, that the study sought to examine a contemporary phenomenon in context, and that the researchers would have no control over the phenomenon of interest (Yin, 2014). In using an explanatory single-case study design, stemming from the research questions, careful consideration must be placed on what the case, or the unit of analysis, of the study will be. Determining what the case is and is not remains a challenging aspect of case study research (Baxter & Jack, 2008).

The Case

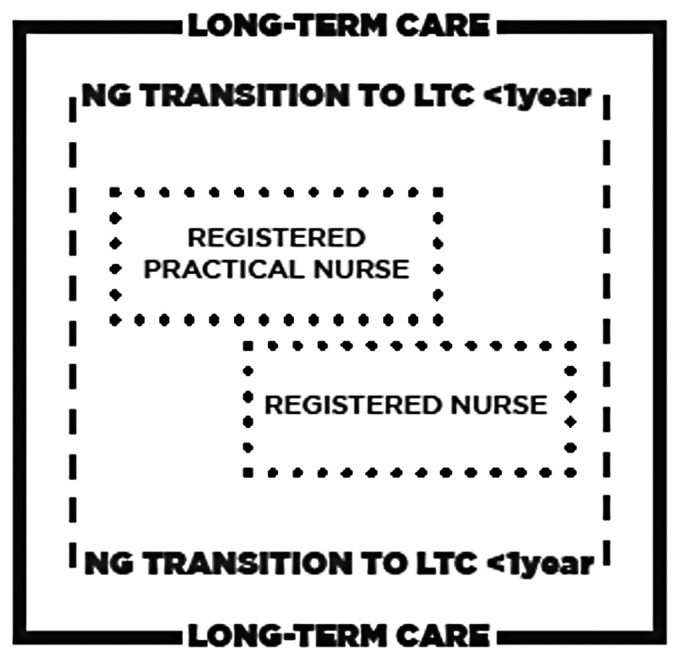

In case study research, emphasis is placed upon the set boundaries of the phenomenon under study. These boundaries provide clarification of what was and what was not studied within the research study (Baxter & Jack, 2008). Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of the case study binding and represents the overall unit of analysis—the transition experience of NGNs in LTC.

Figure 2.

Case study binding.

The “case” in case study research is defined as the phenomenon occurring within a bound context with emphasis on multiple dimensions and is inclusive of the conceptual nature, social size, physical location, and temporality of the case (Miles et al., 2014). Utilizing this definition, the case for this described protocol was the experience of NGN transition to practice in LTC in Southwestern Ontario.

Case Definitions

From the review of the literature, three key terms were identified. These included transition to practice, NGN, and RN and RPN. This terminology provided foundational understanding of the phenomenon under study, aided in the establishment of study propositions, and importantly, assisted in the development of case parameters.

Transition to practice

Transition to practice in the literature is defined as an active process of holistic learning within a professional role (Duchscher, 2008; 2009; Laschinger, Grau, Finegan, & Wilk, 2010) and is a phenomenon that has been investigated and studied in a general manner for several decades. There remains academic interest with this topic because of described relationships between transition to practice and nurse retention, educational preparation, patient safety, and job satisfaction (Baumann et al., 2015; Duchscher, 2008, 2009; Dyess & Sherman, 2009; Laschinger et al., 2010; Purling & King, 2012; Sasichay-Akkadechanunt, Scalzi, & Jawad, 2003; Wolff, Regan, Pesut, & Black, 2010). For this protocol, transition to practice was defined as “a nonlinear experience that moves through personal and professional, intellectual and emotive, and skill and role relationship changes and contains within it experiences, meanings, and expectations” (Duchscher, 2008, p. 442). This broad definition of transition to practice allowed the research to remain inductive in nature and for themes to be explored within this phenomenon of interest.

New graduate nurse

The time frame used to define the NGN in the literature ranges from 6 months (Ministry of Health and Long-term Care [MOHLTC], 2014) to 3 years of practice (Benner, 1982; Bitanga & Austria, 2013; Laschinger et al., 2010). In consideration of the literature, the NGN in this protocol was defined as a nurse, inclusive of either designation (RN or RPN), within the first 12 months of practice (Casey, Fink, Krugman, & Propst, 2004; Duchscher, 2008, 2009; Dyess & Sherman, 2009). This definition allowed for the inclusion of both nurse designations represented within LTC and constituted a time frame that permitted significant practice development and aligned with much of the transition to practice theory (Duchscher, 2008, 2009).

Registered Nurse and Registered Practical Nurse

The professional designation of nurse, whether RN or RPN (also referred to as Licensed Practical Nurse), is a protected title legally bestowed upon individuals who have met required standards (College of Nurses of Ontario [CNO], 2018). Although both RNs and RPNs study from the same body of nursing knowledge, a stronger emphasis on “clinical practice, decision making, critical thinking, leadership, research utilization, and resource management” grant a greater level of autonomous practice to the RN (CNO, 2018, p. 3). In addition, the complexity of the condition of the patient influences the level of nursing care required, with more complex and less stable situations requiring the care of an RN or at minimum the consultation of an RN (CNO, 2018). The entry-to-practice educational requirements of the RN are a baccalaureate degree while the RPN is required to complete a college diploma (CNO, 2018; Registered Practical Nurses Association of Ontario, 2014). Both the RN and the RPN must complete a professional registration and jurisprudence examination to practice in the province of Ontario (CNO, 2018). Regardless of professional nursing designation, both the RN and RPN new graduates in LTC experience a transition to practice which has previously not been explored in the literature. In describing the similarities and differences that RN and RPN new graduates experience during their transition to practice, better supports, tailored to their designation, and specific to their education can be developed.

Case Binding

In case study research, there is emphasis placed upon providing boundaries for the phenomenon under study—the case—in order to avoid having a research study that is too broad (Baxter & Jack, 2008). These boundaries, described and justified within a case binding, provide clarification on what will and what will not be studied (Baxter & Jack, 2008). For this described protocol, the case, described as transition to practice of NGNs in LTC, was further bound by the study setting, the study time frame, and the inclusion of embedded units.

Study setting

Described within this protocol was a large, urban city in southwestern Ontario, Canada, in which the sample was taken from two LTC homes. These LTC homes served as the context for the case and ensured representativeness of a typical LTC home, with similar staffing structure and patient care ratios to that of the average LTC home in urban Ontario. This typicality permitted the use of a single-case study design with embedded units and aimed to uphold the external validity of the transition to practice experience. As described by Yin (2014), a typical case captures and describes the conditions of a common situation. The context, which of two LTCHs, was meant to bind and influence the case, but the geographic location was not intended to influence the phenomenon of interest.

Time frame

The time frame described within this protocol was bound within the established NGN definition of 1 year or less of practice. This time frame allowed for sufficient growth and experience of the NGN during their transition to practice without allowing for too much variability in experience or recall bias.

Embedded units

Yin’s approach to case study research includes the possibility of examining embedded units within a single-case study design (Yin, 2014). Embedded units represent distinct but connected entities within a case (Yin, 2014). This is an important opportunity when studying the context of LTC as both nurse designations are employed and working within a high degree of autonomy and serve as the basis of the two embedded units. These logical subunits add further binding to the case under study and allow the researcher to study both within subunits, between subunits, and to then make assertions about the entire case (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Yin, 2014).

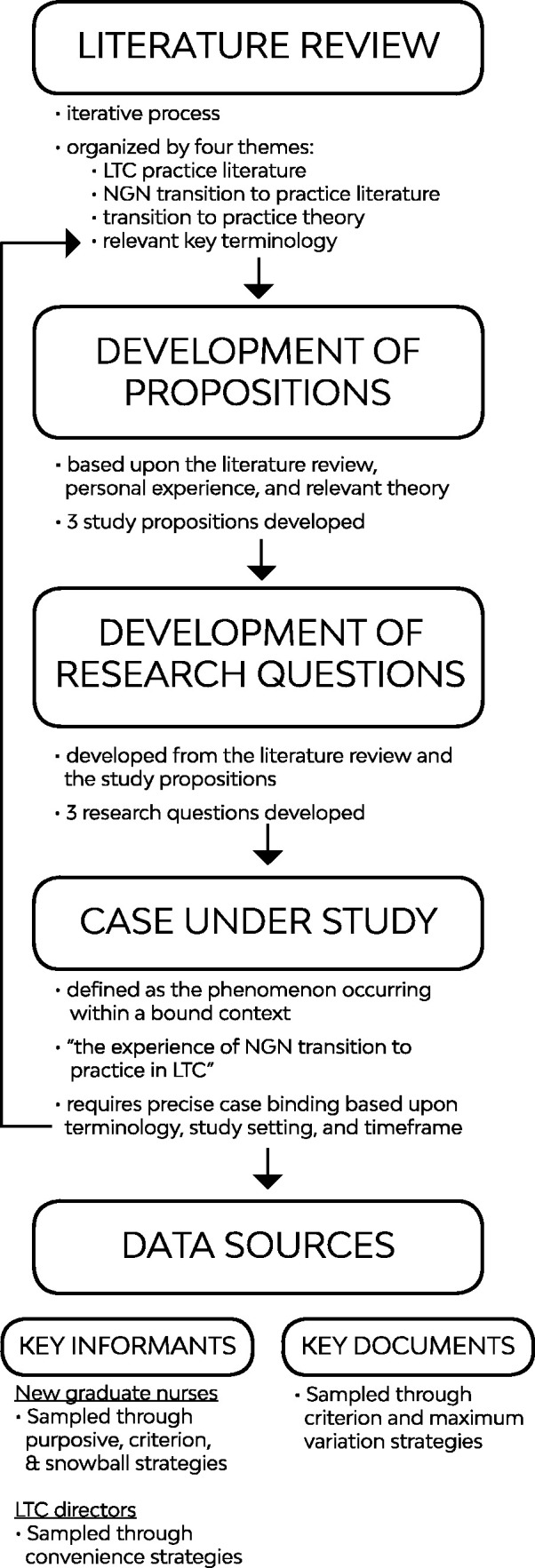

Case Study Methodology

Case study methodology, rooted in the social sciences, aims to understand the essence of a real, contemporary phenomenon within a specified context (Baxter & Jack, 2008). This methodology uses multiple data sources without controlling the behavior under study (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Creswell, 2013; Hancock & Algozzine, 2006). Case study, unlike other qualitative study designs, can be used in both qualitative and quantitative research (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Creswell, 2013). Figure 3 provides a representation of the activities and decisions made in this case study, of which ethics review board approval was received.

Figure 3.

Protocol activities.

Data Sources

A key characteristic of the case study approach is the use of multiple data sources (Yin, 2014). Data from each source are later converged in order to understand the case in its entirety. Purposeful, criterion, and snowball sampling were used to identify Key Informants, while criterion and maximum variation sample were used to identify Key Documents. More information on sampling for each of the data sources is provided in the following sections.

Key Informants

Key Informants were those individuals who shared information and their perspectives and included NGNs and LTC directors at the two LTC homes. NGNs were considered to be the primary sources of data because of their proximity to the phenomenon of interest and their ability to accurately describe their own transition to practice experience.

LTC directors were considered secondary sources of data because of their supervision of NGNs in their practice settings. These secondary sources were able to describe the transition to practice experience of NGNs because of their engagement and relationship with the NGNs. Semistructured interview guides, developed from the literature, transition to practice theory, and directed by the study propositions, guided the interviews with both primary and secondary Key Informants.

Key Documents

The collection and analysis of Key Documents is an important component of case study research, as these documents serve to corroborate evidence from other data sources, provide clarification of terms, and promote further investigation related to document content (Yin, 2014). Key Documents included orientation packages, program overviews to support NGN transition to practice, and policies related to nursing practice or orientation. These documents varied between the two LTC homes in both availability and content as well as provided corroborating evidence and data convergence (Yin, 2014) on themes identified within Key Informant interviews.

Sampling

In case study research methodology, sampling strategies must be identified for each of the included data sources a priori (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Yin, 2014). In this described protocol, the NGN Key Informants, purposive sampling strategies were utilized with characteristics of the desired sample based upon the case and the case binding. Criterion sampling was used to exclude those NGNs who had worked in LTC for greater than 1 year or those who had held a previous nursing position prior to working in LTC. In addition, snowball sampling was used with NGNs who were encouraged to share the study details with other NGN colleagues within their LTC home so as to maximize recruitment in the LTC home. LTC directors, also serving as Key Informants, were sampled through convenience sampling, incorporating those directors of the included LTC homes and serving as gatekeepers. In addition, sampling for Key Documents involved criterion sampling, utilizing broad inclusion criteria on what documents to be analyzed so as to include any document related to the case under study, and maximum variation sampling so that each participant was encouraged to discuss any relevant documents during their interview. The two LTC homes were selected through convenience and criterion sampling so as to ensure that the typicality of the case and phenomenon were maintained (Creswell, 2013; Yin, 2014). Inclusion criteria for the LTC homes included a geographic location—Southwestern Ontario—as well as the requirement that the home employed NGNs. Further definition of specific sampling strategies and other case study terminology is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Case Study Definitions.

| Term | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Case under study | The phenomenon occurring within a bound context and the unit of analysis. |

| Case binding | Those specific boundaries set upon the case under study. May include definitions of key terminology, study setting, time frame, or geography that delineate the conditions that fall within the case as opposed to that which is outside of the case. |

| Context | The real-life influence of social, physical, and temporal concepts on a phenomenon. |

| Convenience sampling | A sampling strategy that includes those who are easy to reach within a certain context. |

| Criterion sampling | A sampling strategy in which the selection of cases or participants is based upon predetermined criteria of importance. |

| Embedded units | A unit of analysis lesser or smaller than the main case under study. |

| Explanatory case study | A case study design with the purpose of explaining how or why a condition or phenomenon came to be. |

| Maximum variation sampling | A sampling strategy in which participants are selected to ensure a wide variety of characteristics. A type of purposive sample. |

| Propositions | The guiding statements of a study that bind the scope, inform the research questions and analysis, and ensure a thorough exploration of the phenomenon of interest. Not intended to be confirmed or refuted. |

| Purposive sampling | A sampling strategy that is selected based upon characteristics of a population to satisfy the objectives of the study. |

| Snowball sampling | A sampling strategy that involves existing study recruits recruiting future participants from those that they know. |

| Typical case study | A case study design that captures and describes the conditions of a common situation within a phenomenon so as to ensure representativeness. |

Sample size

Sample size within case study research is neither explicit nor prescriptive; however, a priori sampling decisions, inclusive of sample size, are included so as to suggest that the complexity of the phenomenon is considered in the planning of the study (Yin, 2014). Data collection included both new graduate RNs and RPNs, LTC directors, and various Key Documents. As such, from each of the recruited LTC homes, the objective was to include a minimum of one to two new graduate RNs, two to three new graduate RPNs, one LTC director, and two Key Documents (Marshall, Cardon, Poddar, & Fontenot, 2013). This objective was based upon knowledge of the staffing ratios in the LTC homes as well as an idea about data saturation. A total of four Key Documents, seven NGNs—four RNs and three RPNs—and two LTC directors were recruited.

Recruitment

Recruitment for this described protocol occurred within the binding of the case and within the natural setting. This ensured that it was the phenomenon of interest, or the case, that was being studied. Recruitment strategies were varied and included posters distributed in LTC homes, face-to-face recruitment within the LTC home, and e-mails from research team gatekeepers who had connections with the LTC home. These various strategies assisted in recruiting the desired sample size.

Data Collection

Yin’s case study approach may involve the collection and analysis of documents, interviews, observations, and artifacts (Yazan, 2015; Yin, 2014). Gathering data, as discussed by Yin (2014), is influenced by the researcher or research team as well as the a priori decisions established within the case study protocol. This can involve both qualitative and quantitative data (Yin, 2014).

Interviews

To explore the transition to practice experience, semistructured interviews with Key Informants, inclusive of NGNs and LTC directors, were completed (Yin, 2010, 2014). Interviews are a preferred data collection strategy in case study design, as the purpose is not to manipulate behavior (Yin, 2014).

Each interview was directed by an interview guide informed by the reviewed literature, the transition to practice theory, as well as the study propositions. The interview guide was pilot tested on two NGNs who had previously worked in LTC to ensure construct validity and gain practice in the interview delivery. Examples of interview questions for NGNs included the following: Describe to me the difference between being a nursing student and being a NGN? What resources helped you with your transition experience? Tell me what it is like being a NGN in LTC? And Describe to me your understanding of the role of a nurse in the LTC setting?

Debriefing following interviews was completed with research team. NGNs were asked demographic questions with each participant interview scheduled outside of scheduled work hours at a mutually agreed upon, neutral location such as a public library or coffee shop. The focused interview was audio-recorded with two digital recorders and transcribed verbatim (Creswell, 2013; Yin, 2014). During each interview, notes and observations were recorded to add to the rich description yielded from the interview. LTC directors were interviewed during work hours with emphasis placed upon their perceptions of and experience with good transition to practice. Interviews lasted for 30 to 90 minutes. Once the interview guide was completed and it appeared that the topic of transition to practice had been exhausted, the data provided were summarized for the interviewee. Each interviewee was then encouraged to confirm or expand upon this summary of findings as a form of member checking (Creswell, 2013).

Document Review

Key Informants were asked to bring Key Documents that may be relevant to their transition to practice. Key Documents that were mentioned in an interview but were not provided at the time were later acquired through LTC home gatekeepers. Key Documents were reviewed to determine how they contributed to, or influenced, the NGN’s transition to practice experience. Notes were transcribed onto the document during the interview.

Data Management

All interviews, documents, and notes were scanned or transcribed verbatim and imported into N-Vivo v.11.4© with all identifying information either removed or redacted.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

For this described protocol, data analysis and interpretation occurred simultaneously with the study findings based upon the principle of data convergence (Yin, 2014). This convergence, completed prior to data analysis, promotes internal validity and reliability of the findings, but most importantly, applies the same template of analysis to all data sources thereby ensuring that the phenomenon under study remains at the centre of inquiry (Baxter & Jack, 2008). The analysis process, as described by Yin (2010), involved five iterative stages: compiling, disassembling, reassembling, interpreting, and concluding. Each of these five stages are further explored.

Compiling

Data were collected and analyzed concurrently to identify emerging themes, inform future interviews, and determine data saturation (Creswell, 2013; Miles et al., 2014). Data management software permitted data manipulation, coding, and theme identification (Yin, 2014).

Disassembling

Data reduction involved a hybrid approach to coding that allowed for inductive, a posteriori code generation while respecting those a priori decisions within the data generated (Creswell, 2013; Yin, 2014). Initial codes used in the analysis were based upon the literature review as well as the study propositions. An edit organizing style of qualitative data analysis was utilized. This involves the researcher acting as an interpreter of the data, searching for meaningful units and organizing these units into categories (Creswell, 2013). These units formed the codes, and the categories the broader themes. Constant comparison was employed so that themes within the data could be identified (Yin, 2014).

Reassembling, Interpreting, and Concluding

After data reduction and the completion of the coding of all transcripts, data were reassembled for content analysis and interpretation (Miles et al., 2014; Yin, 2010). This process resulted in the formulation of a description of the case. Themes were identified from the code list with some consideration of the frequency of codes within analysis as permitted within the methodology.

Discussion

Case study research is methodologically challenging research, as it requires precise binding of the case under study as well as the utilization of multiple, comprehensive data sources (Baškarada, 2014; Baxter & Jack, 2008; Creswell, 2013; Hancock & Algozzine, 2006). As such, and to address a lack of case study exemplars within the literature, strengths of the methodology as well as those lessons learned within this described research project will be shared.

Strengths

Case study research permits an iterative approach to data collection and analysis. From the creation of guiding study propositions all the way to the five stages of analysis encouraged by Yin (2010), data emergence, whether from the literature or from research findings, shapes those decisions and observations within the study. This meant that as data were being collected and themes were being identified, previous and subsequent data points were being evaluated against that which was being developed. This in turn results in data convergence and thereby a deeper insight into the phenomenon of interest based upon all sources of evidence.

Another particular strength of case study design, and important in this particular described protocol, was the ability to embed the two distinct and separate nursing designations within the same context in LTC. The use of embedded units within a single-case study design provided the opportunity to examine the transition experience between subunits and within subunits. This furthered the understanding of the phenomenon of interest and promoted more detailed understanding at the subunit level.

Lessons Learned

Designing a case study is a challenging work. Of particular challenge in the development of this protocol was the process of binding the case. In case study research, there is emphasis placed upon providing boundaries for the phenomenon under study in order to avoid having a research study that is too broad (Baxter & Jack, 2008). This becomes challenging, as a case study design should only be used when the boundaries between the context and the identified phenomenon of interest are unclear but when a clear case can be identified (Yin, 2014). Teasing out a case from within the context and phenomenon, which in this protocol were the LTC setting and the transition to practice experience, respectively, required precise understanding and definition of terminology in order to indicate overall depth and breadth. As the case binding is arguably the most important step in designing a case study, as most decisions are based upon this process, great time and energy should be spent on exhaustive literature review and the careful development of propositions to inform the unit of analysis.

Case study designs, specific to contexts and complex social phenomenon, aim to generalize to theories as opposed to populations (Baškarada, 2014). This complicates the dissemination of research findings as often the results, while extensive and rich, generally only apply to the natural context it was studied within. As such, it is important when completing case study research to provide a detailed description of the setting, the use of the expertise within the research team, as well as the inclusion of rival explanations within the discussion in order for the reader to be able to assess for themselves the credibility or validity of the findings (Baxter & Jack, 2008). In this protocol, it was important to uphold the typicality of the LTC home, collect demographic data, and describe the setting in detail so as to be transparent about findings.

Lastly, of particular challenge in disseminating case study research findings is the difficulty in publishing study results and design description within the confines of academic journals inclusive of page limits and word counts. As case study research requires detailed description of available literature, the case, case binding, and all other a priori decisions related to the study design, little space is left in manuscript preparation to share and describe the rich and extensive findings garnered through this design. This is challenging, as this level of detail is necessary so that the results and findings can be considered within the context of which the phenomenon was studied.

Conclusion

In this report, a description of the case study methodology used to explore the transition to practice experience of NGNs in LTC was provided. This report will facilitate learning about this complex research design and will be of interest to a broad audience. This report demonstrates an application of the explanatory single-case study methodology and provides real-world lessons learned related to the design and utilization of this qualitative research methodology.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Baumann, A., Hunsberger, M., Crea-Arsenio, M., & Rizk, P. (2015). Employment integration of nursing graduates: Evaluation of a provincial policy strategy, Nursing Graduate Guarantee 2013–2014. In Health Human Resources Series 41. Hamilton, ON: Nursing Health Services Research Unit, McMaster University. Retrieved from http://nhsru.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/NGG-Evaluation-Report-2013-2014_digital_Feb-18_15.pdf.

- Baškarada S. (2014) Qualitative case study guidelines. The Qualitative Report 19(40): 1–18. Retrieved from http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol19/iss40/3/. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, P. (2007). Fact sheet: A literature review of orientation programs for new nursing graduates. Hamilton, ON: Nursing Health Services Research Unit.

- Baxter P. E. (2010) Providing orientation programs to new graduate nurses: Points to consider. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development 26(4): 12–17. doi:10.1097/NND.0b013e3181d80319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter P., Jack S. (2008) Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report 13(4): 544–559. Retrieved from http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR13-4/baxter.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Beaty J., Young W., Slepkov M., Isaac W., Matthews S. (2009) The Ontario new graduate nursing initiative: An exploratory process evaluation. Healthcare Policy 4(4): 43–50. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2700701/pdf/policy-04-043.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner P. (1982) From novice to expert. American Journal of Nursing 82(3): 402–407. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.libaccess.lib.mcmaster.ca/stable/3462928?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitanga M. E., Austria M. (2013) Climbing the clinical ladder—One rung at a time. Nursing Management 44(5): 23–27. doi:10.1097/01.NUMA.0000429008.93011.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J., Dussault, G., Buchan, J., Pozo-Martin, F., Guerra Arias, M., Leone, C., . . . Cometto, G. (2013). A universal truth: No health without a workforce (Forum Report, Third Global Forum on Human Resources for Health, Recife, Brazil). Retrieved from http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/GHWA-a_universal_truth_report.pdf.

- Canadian Healthcare Association. (2009). New directions for facility-based long term care. Retrieved from http://www.healthcarecan.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/CHA_LTC_9-22-09_eng.pdf.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2015). Supply of nurses in Canada declines for first time in 2 decades. Retrieved from https://www.cihi.ca/en/spending-and-health-workforce/healthworkforce/supply-of-nurses-in-canada-declines-for-first-time-in.

- Canadian Medical Association. (2016). The state of seniors health care in Canada. Retrieved from https://www.cma.ca/En/Lists/Medias/the-state-of-seniors-health-care-in-canada-september-2016.pdf.

- Canadian Nurses Association. (2008). The long-term care environment: Improving outcomes through staffing decisions. Retrieved from https://www.cna-aiic.ca/∼/media/can/pagecontent/pdf-en/hhr_policy_brief4_2008_e.pdf?la=en.

- Canadian Nurses Association. (2011, June). In it for the long term. Canadian Nurse. Retrieved from https://canadian-nurse.com/en/articles/issues/2011/june-2011/in-it-forthe-long-term.

- Casey, K., Fink, R., Krugman, M., & Propst, J. (2004). The graduate nurse experience. Journal of Nursing Administration, 34(6), 303–311. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Regina_Fink2/publication/8517544_The_Graduate_Nurse_Experience/links/00b4952e3cc246c730000000.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- College of Nurses of Ontario. (2018). RN and RPN practice: The client, the nurse, and the environment. Retrieved from http://www.cno.org/globalassets/docs/prac/41062.pdf.

- Creswell J. W. (2013) Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches, 3rd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Duchscher J. E. B. (2008) A process of becoming: The stages of nursing graduate professional role transition. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing 39(10): 441–450. Retrieved from http://nursingthefuture.ca/assets/Documents/Stages2008.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchscher J. E. B. (2009) Transition shock: The initial stage of role adaption for newly graduated registered nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing 65(5): 1103–1113. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyess S. M., Sherman R. O. (2009) The first year of practice: New graduate nurses’ transition and learning needs. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing 40(9): 403–410. doi:10.3928/00220124-20090824-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson-Pare M. L. (1995) Registered nurses’ perception of their autonomy and the factors that influence their autonomy in rehabilitation and long-term care settings. Canadian Journal of Nursing Administration 9(2): 95–108. Retrieved from http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/8716473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giallonardo L. M., Wong C. A., Iwasiw C. L. (2010) Authentic leadership of preceptors: Predictor of new graduate nurses’ work engagement and job satisfaction. Journal of Nursing Management 18: 993–1003. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock D. R., Algozzine B. (2006) Doing case study research: A practical guide for beginning researchers, New York, NY: Teachers College Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger, H.K.S., Grau, A.L., Finegan, J., & Wilk, P. (2010). New graduate nurse experiences of bullying and burnout in hospital settings. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(12), 2732–2742. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05420.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Marshall B., Cardon P., Poddar A., Fontenot R. (2013) Does sample size matter in qualitative research? A review of qualitative interviews in is research. Journal of Computer Information Systems 54(1): 11–22. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/36e5/5875dadb4011484f6752d2f9a9036b48e559.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B. & Huberman, A.M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded source (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Miles M. B., Huberman A. M., Saldaña J. (2014) Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook, 3rd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. (2014). Guidelines for participation in the Nursing Graduate Guarantee for New Graduate Nurses. Retrieved from http://www.healthforceontario.ca/UserFiles/file/Nurse/Inside/ngg-participation-guidelinesjan-2011-en.pdf.

- Ontario Long Term Care Association. (2018). This is long-term care 2018. Retrieved from https://www.oltca.com/OLTCA/Documents/Reports/ThisIsLongTermCare2018.pdf.

- Purling A., King L. (2012) A literature review: Graduate nurse preparedness for recognizing and responding to the deteriorating patient. Journal of Clinical Nursing 21(23): 3451–3465. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Registered Practical Nurses Association of Ontario. (2014). It’s all about synergies: Understanding the role of the Registered Practical Nurse in Ontario’s health care system. Retrieved from https://www.rpnao.org/sites/default/files/RoleClarityReport_.pdf.

- Robertson E. M., Higgins L., Rozmus C., Robinson J. P. (1999) Association between continuing education and job satisfaction of nurses employed in long-term care facilities. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing 30: 108–113. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.libaccess.lib.mcmaster.ca/docview/223326502?accountid=12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush, K. & Adamack, M. (2013). Expanding the evidence for new graduate nurse transition best practices. Retrieved from http://www.msfhr.org/sites/default/files/Expanding_the_Evidence_for_New_Graduate_Nurse_Transition_Best_Practices.pdf.

- Sasichay-Akkadechanunt T., Scalzi C. C., Jawad A. F. (2003) The relationship between Nurse staffing and patient outcomes. Journal of Nursing Administration 33(9): 478–485. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14501564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff A. C., Regan S., Pesut B., Black J. (2010) Ready for what? An exploration of the meaning of new graduate nurses’ readiness for practice. International Journal of Nursing Education and Scholarship 7(1): doi:10.2202/1548-923X.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazan B. (2015) Three approaches to case study methods in education: Yin, Merriam, and Stake. The Qualitative Report 20(2): 134–152. Retrieved from http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol20/iss2/12/. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. (2010). Qualitative research from start to finish. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Yin R. K. (2014) Case study research: Design and methods, 5th ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]