Abstract

Introduction

Most healthcare professionals rarely experience situations of a request for organ donation being made to the patient’s family and need to have knowledge and understanding of the relatives’ experiences.

Objective

To describe relatives’ experiences when a family member is confirmed brain dead and becomes a potential organ donor.

Methods

A literature review and a thematic data analysis were undertaken, guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses reporting process. A total of 18 papers, 15 qualitative and 3 quantitative, published from 2010 to 2019, were included. The electronic search was carried out in January 2019.

Results

The overarching theme When life ceases emerged as a description of relatives’ experiences during the donation process, including five subthemes: cognitive dissonance and becoming overwhelmed with emotions, interacting with healthcare professionals, being in a complex decision-making process, the need for proximity and privacy, and feeling hope for the future. The relatives had different needs during the donation process. They were often in shock when the declaration of brain death was presented, and the donation request was made, which affected their ability to assimilate and understand information. They had difficulty understanding the concept of brain death. The healthcare professionals caring for the patient had an impact on how the relatives felt after the donation process. Furthermore, relatives needed follow-up to process their loss.

Conclusion

Caring science with an explicit relative perspective during the donor process is limited. The grief process is individual for every relative, as the donation process affects relatives’ processing of their loss. We assert that intensive care unit nurses should be included when essential information is given, as they often work closest to the patient and her or his family. Furthermore, the relatives need to be followed up afterwards, in order to have questions answered and to process the grief, together with healthcare professionals who have insight into the hospital stay and the donation process.

Keywords: acute illnesses, advance practice nurses, death/dying, intensive care unit, other—zero level, practice, qualitative research, research

Around the world, there is a need of organs for transplantation. In 2018, Scandiatransplant (organ exchange organization for Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and Estonia, with a combined population of 28 million) had 2,285 persons on the transplantation waiting list (Scandiatransplant, 2019). The donation process includes identifying a potential donor and medical suitability, obtaining consent, and finally performing donation surgery (Johnsson & Tufvesson, 2001). In a Swedish prospective observational study of all intensive care unit (ICU) deaths in Sweden from January 1, 2009 to December 31, 2014, women were more likely than men were to become donors (Nolin et al., 2017).

Before a donation decision, a medical suitability evaluation is made to determine whether donation is possible. The transplant surgeon determines the medical fitness of the organs. The ICU contacts the transplant coordinator, who is the link between the ICU and the transplant center (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2018). Organ functions and blood samples are examined (Johnsson & Tufvesson, 2001) and if consent to donation is obtained and the medical examination finds the organs suitable for transplantation, medical treatment is continued until the organ donation operation. In 2018, 546 patients became Donation after Brain Death donors and 10 became Donator after Circulatory Death donors within Scandiatransplant (Scandiatransplant, 2019).

Grief can be defined as a normal and natural reaction to loss, including its physical, emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and spiritual manifestations (Hall, 2014). In a traumatic crisis such as a family member’s death, the individual’s basic identity, security, and existence are threatened. According to Kübler-Ross (1969), a crisis is individual and is comprised of five, not necessarily linear, phases. Although it has been challenged at times, the Kübler-Ross model remains one of the best-known and most influential models of grief. A Netherlands study describes that healthcare professionals provide better support to relatives prior to donation requests when they address the relatives’ needs and adapt their message to individual circumstances (de Groot et al., 2016). In order for healthcare professionals to be able to provide optimal support for a patient’s relatives, they need knowledge about their experience during the donation process.

Aim

The aim was to describe the content and scope in research on relatives’ experiences when a family member is confirmed brain dead and becomes a potential organ donor.

Research Design and Methods

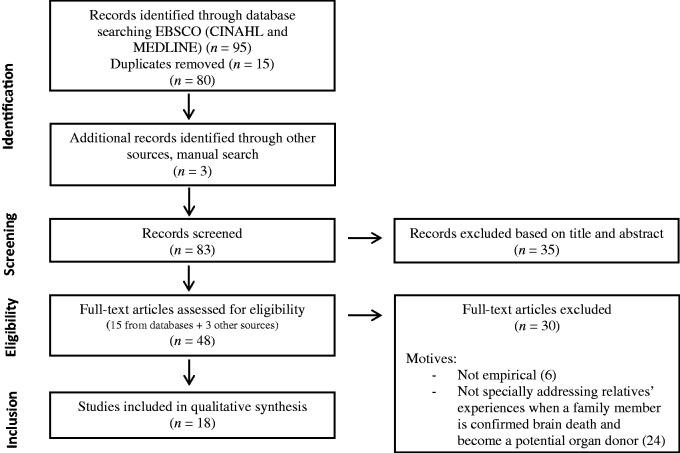

The current literature review used a modified version of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart to illustrate the results of the searches (Moher et al., 2015). This study used a method of literature review as described by Whittemore and Knafl (2005). In MedLine, searches were made on MeSH headings along with key words and words in titles and abstracts. Specific MeSH terminology included Brain and Family. Database search and database controlled vocabulary were conducted in combination with keywords in Cinahl and MedLine via EBSCO host. The search yielded 95 results, and after removal of 15 duplicates, 80 citations were reviewed. Inclusion criteria were the following: studies in English published between January 2010 and January 2019, with the search terms: organ donation AND famil* OR relativ* AND experience* AND brain death. Exclusion criteria included the following: research from the healthcare professionals’ perspective, if the research focused on organ donation for medical research purposes, and if the research focused on the relatives to child or pregnant potential donor. If the article title did not contain any exclusion criteria, the abstract was read. The search process is outlined in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses chart (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Results of Search Strategy Based on the PRISMA Statement.

Source: Moher et al. (2015).

The initial search yielded 80 articles. After the abstracts were read, 65 articles were excluded due to inadequately described results or unsuitable aims, resulting in 15 studies ultimately being included in the analysis. A manual search of the found studies’ reference lists revealed three additional studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria and contained no exclusion criteria. These 18 articles—15 qualitative and three quantitative—were read in full (Table 1). Data analysis was completed using a systematic approach consisting of sorting, categorizing, and summarizing data in an effort to create meaningful conclusions about the state of the knowledge (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). The studies’ methodological and/or theoretical rigor was evaluated on a three-level scale: high, medium, or low (Critical Apprasial Skills Programme, CASP, 2010). Furthermore, the studies were evaluated on a two-level scale (high or low) according to data relevance (Table 1). No studies were excluded based on these two evaluations. The final search output was 18 papers, which reported on 16 studies.

Table 1.

Summary of the Reviewed Studies (n = 18).

| Authors/Year (References) | Country | Research design | Aim and objective | Sample | Data collection, key measurements, analyze method | Major findings relevant to the review | Methodo-logical and theoretical rigor | Relevance of data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berntzen & Bjørk (2014) | Norway | Qualitative | To investigate the experience of Norwegian donor families during organ donation after brain death. | Donor families (n = 20) | Semi-structured family interviews and individual interviewsContent analysis | Reconciliation with the decision of organ donation and the subsequent situation was gained through understanding the organ donation process, recognition of the increased strain, and satisfaction resulting from the contribution made by organ donation. | High | High |

| da Silva Knihs et al. (2015) | Brazil | Qualitative | To understand the experience of families in the process of hospitalization, brain death, and interview for organ donation. | Donor families (n = 18) | Semi-structured family interviews and individual interviewsPhenomenological approach | The path walked by the families is difficult and makes it necessary to rethink the care provided to these people by health professionals throughout the process. The time between the report of the death and the provision of information about organ donation is important for the family to organize its thoughts and make the best decision. The study shows that this time has not been respected. | High | High |

| de Groot et al. (2016) | Netherlands | Qualitative | To explore the perspectives of relatives regarding the request for consent for donation in cases without donor registration. | Donor relatives (n = 24) | In-depth group interviews and individual interviews and one letterContent analysis | Relatives of unregistered, brain-dead patients usually refuse consent for donation, even if they harbor prodonation attitudes themselves, or knew that the deceased favored organ donation. Half of those who refused consent for donation mentioned afterwards that it could have been an option. The decision not to consent to donation is attributed to contextual factors, such as feeling overwhelmed by the notification of death immediately followed by the request, not being accustomed to speaking about death, inadequate support from other relatives or healthcare professionals, and lengthy procedures. | High | High |

| Fernandes et al. (2015) | Brazil | Qualitative | To identify experiences and feelings on the organ donation process, from the perspective of a relative of an organ donor in a transplant unit. | Donor families (n = 7) | Semi-structured family interviewsContent analysis | Participants’ highlighted poor sensitivity of the medical staff communicating the relative’s brain death—the potential donor and the lack of socioemotional support prior to the situation experienced by the family. There were needs to provide social–emotional support for families facing the experience of the organ donation process. | High | High |

| Gyllstrom Krekula et al. (2018) | Sweden | Qualitative | To explore donor relatives’ experiences of the medical treatment enabling organ donation, as well as to examine the donor relatives’ attitudes toward donating their own organs, and whether their experiences have influenced their own inclination to donate or not. | Donor relatives (n = 21) | Semi-structured interviews with open-ended questionsQualitative and quantitativeContent analysis | Brain death and organ donation proved to be hard to understand for many donor relatives. The prolonged interventions provided after death in order to enable organ donation misled some relatives to believe that their family member still was alive. Most donor relatives were either inspired to, or reinforced in their willingness to donate their own organs after having experienced the loss of a family member who donated organs. Having experienced the donation process closely did not discourage the donor relatives from donating their own organs, but rather inspired a willingness to donate. | Medium | Low |

| Jensen(2016) | Denmark | Qualitative | To explore the transformative practices of hope in Danish organ donation. | Donor families (n = 80) | Observation and interviewsThematic analysis | Hope was used by families as an existential lens to understand, reinterpret, and articulate the emotional burdens and rewards of consenting to organ donation. | Low | Low |

| Kentish-Barnes et al. (2019) | France | Qualitative | To determine (a) what it means for family members to make the decision, (b) how they interact with the deceased patient in the ICU, and (c) how family members describe the impact of the process and of the decision on their bereavement process. | Donor families (n = 24) | Semi structured interviews by phoneGrounded theory | In spite of caregivers’ efforts to focus organ donation discussions and decision on the patient, family members feel a strong decisional responsibility that is not experienced as a burden but a proof of their strong connection to the patient. Brain death, however, creates ambivalent experiences that some family members endure, whereas others use as an opportunity to perform separation rituals. Last, organ donation can be experienced as a form of comfort during bereavement provided family members remain convinced their decision was right. | Medium | Low |

| Kentish-Barnes et al. (2018) | France | QuantitativeProspective observational | To assess the experience of the organ donation process and grief symptoms in relatives of brain-dead patients who discussed organ donation in the ICU. | Relatives of donors and non-donor patients (n = 202) | QuestionnairesDescriptive statistics and statistical analysis | Experience of the organ donation process varied between relatives of donor versus nondonor patients, with relatives of nondonors experiencing lower quality communication, but the decision was not associated with subsequent grief symptoms. Importantly, understanding of brain death is a key element of the organ donation process for relatives. | High | High |

| Kim et al. (2014) | Korea | QuantitativeCross-sectional survey | To investigate the satisfaction of the families of brain dead donors with regard to donation processes as well as their emotions after the donation. | Donor families (n = 45) | QuestionnairesDescriptive statistics | Missing the dead person and pride were the most common emotions experienced after organ donation followed by grief, family coherence, and guilt. Religious practices were observed to be most helpful for psychological stress relief after donation, followed by spending time with family and friends. 24.1% responded that they had not overcome their suffering. | High | Low |

| Manuel et al. (2010) | Canada | Qualitative | To describe and interpret what life is like for individuals who have consented to donate the organs of a deceased relative for transplantation. | Donor families (n = 5) | Family members’ narrative descriptionsThematic analysisPhenomenological approach | Thematic analysis of the participants’ narrative descriptions identified five essential themes: the struggle to acknowledge the death, the need for a positive outcome of the death, creating a living memory, buying time, and the significance of support networks in the organ donation decision. The integration of these themes revealed the essence of the experience as creating of a sense of peace. | Medium | Low |

| Manzari, Mohammadi, Heydari, Aghamohammadian Shearbaff, et al. (2012) | Iran | Qualitative | To explore the specific needs of families with a brain-dead patient during the organ donation process. | Donor families (n = 35) | Unstructured in-depth interviews and field notesContent analysis | The findings indicated that the families faced with an organ donation request of a brain-dead loved one experienced a lasting effect long after the patient’s demise regardless of their decision to donate or refusal to donate. In conclusion, this study highlights the importance of family support and follow-up in an efficient healthcare system aimed at developing trust with the families and providing comfort during and after the final decision. | High | High |

| Manzari, Mohammadi, Heydari, Sharbaf, et al. (2012) | Iran | Qualitative | To explore families’ experiences of an organ donation request after brain death. | Relatives of donors (n = 14) and nondonor (n = 12) patients | Unstructured in-depth interviewsContent analysis | The findings indicated that the families faced with an organ donation request involving a brain-dead loved one experienced a lasting effect long after the patient’s demise, regardless of their consent or refusal to donate. | Medium | High |

| Marck et al. (2016) | Australia | Qualitative | To describe the experiences of families of potential organ and tissue donors eligible for donation after circulatory death or brain death. | Family members(n = 49)consenting (n =24)potential donors (n = 9) and non-consenting (n = 16) | Semi-structured interviews, face by face , or by phoneThematic analysis | The families’ valued frank communication, trusted health professionals and were satisfied with the care their family member received and with donation processes, despite some apparent difficulties. Family satisfaction, infrequently assessed, is an important outcome, and these findings may assist in the education of Australian organ donation professionals. | Medium | Low |

| Neate et al. (2015) | Australia | Qualitative | To understand reasons for consent decisions. | Family members (n = 49), consenting (n =24), potential donors (n = 9) and non-consenting (n = 16) | Semi-structured interviews, face by face , or by phoneThematic analysis | Donation was consistent with the deceased’s explicit wishes or known values and the desire to help others or oneself—including themes of altruism, pragmatism, preventing others from being in the same position, consolation received from donation, and aspects of the donation conversation and care that led families to believe donation was right for them. | Medium | Low |

| Smudla et al. (2012) | Hungary | QuantitativeProspective cohort | To explore communication in the ICU regarding brain stem death and consent to donation, and to analyze 3 to 6 months post donation consequences of organ recovery concerning psychosocial wellbeing (depression and grief reaction) of the relatives who decided to support organ donation. | Donor relatives (n = 29) | QuestionnaireDescriptive statistics and test of significant differences | Bereavement and depression did not correlate with age, marital status, or degree of religiousness. Females had higher physical distress and more severe depression. The psychological reaction was lower among relatives with higher education. Depressive symptoms occurred in 72.4% of participants. Individuals who did not have confidence in the brain death diagnosis had more intense grief reaction and more serious depressive symptoms. | Medium | Low |

| Sque et al. (2018) | United Kingdom | Qualitative | To elicit bereaved families’ experiences of organ and tissue donation. A specific objective was to determine families’ perceptions of how their experiences influenced donation decision making. | Donor families (n = 43) | Semi-structured interviews, face by face, or by phoneContent analysis | Temporally interwoven experiences appeared to influence families’ decisions to donate the organs of their deceased relative for transplantation. When families experienced their relative’s critical illness fluctuations of hope and despair came, in which the option of organ and tissue donation appeared to assist families in their grief. Determination to fulfil the wishes of the deceased was apparent. Participants disclosed a range of preconceived attitudes and beliefs that had the potential to negatively impact on the donation decision. Some families also experienced a lack of knowledge about donation. Consent to donation appeared to give meaning to the life and death of the deceased person, and for some families, a belief that their relative would “live on” through the recipient. | Medium | Low |

| Walker & Sque (2016) | United Kingdom | Qualitative | To provide insight into the perceived benefits of organ and tissue donation for grieving families who experienced end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. | Donor families (n = 43) | Semi-structured interviews, face by face, or by phoneContent analysis | Covered a trajectory of hope and despair, in which the option of organ and tissue donation appeared to give meaning to the life and death of the deceased person and was comforting to some families in their bereavement. Organ donation has the potential to balance hope and despair at the end of life when the wishes of the dying, deceased, and bereaved are fulfilled. | Medium | Low |

| Yousefi et al. (2014) | Iran | Qualitative | To investigate the decision-making process of organ donation in families with brain death. | Donor families (n = 16) | Semi-structured, face by face interviewsThematic analysis | Prohibiting factors were shock, hope for recovery, unknown process, conflict of opinions, and worrying association.The findings indicated that there is ambiguity as well as different interpretations regarding brain death. | Medium | Low |

Note. ICU = intensive care unit

Data Analysis

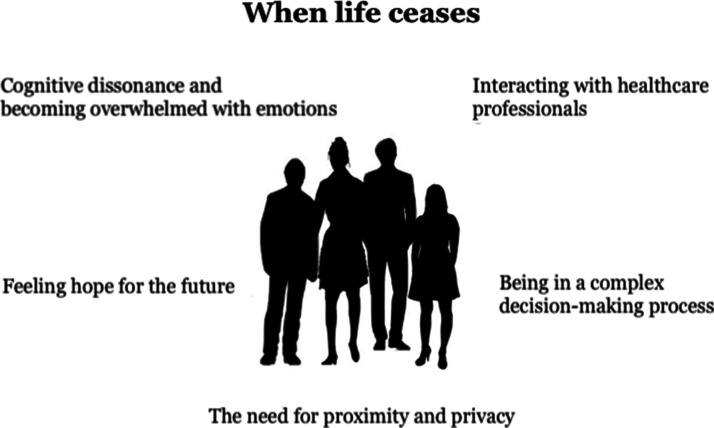

Data analysis was performed in accordance with Whittemore and Knafl’s method (2005) and included the following steps: data reduction, data display, data comparison, and conclusion. The first step was to read the studies in order to understand the whole and to get an overview of each article. Thereafter, similarities and differences between the studies were examined with reference to aim, method and findings, focusing on the chosen data collection method, selection of participants, study purpose, and method of analysis used. Data comparison included rereading each article to ensure that nothing was missed or misunderstood. The results were summarized in fewer words, using codes for each article. The codes were then sorted based on content such as death, donation, and communication, which resulted in heading groups summarized into one theme comprised of five subthemes (Figure 2). Conclusions were drawn and verified with the intent of capturing the breadth and depth of relevant literature (Moher et al., 2015). Rules and guidelines were used to ensure that no misinterpretations arose, and we strove to bridle our preunderstanding during the work, which entails setting aside one’s own preunderstandings of and assumptions about a phenomenon while studying it (Dahlberg & Nyström, 2007).

Figure 2.

Theme and subthemes as a description of relatives' experiences during the donation process.

Findings

The theme When life ceases was established as a description of relatives’ experiences during the donation process, including five subthemes: cognitive dissonance and becoming overwhelmed with emotions, interacting with healthcare professionals, being in a complex decision-making process, the need for proximity and privacy, and feeling hope for the future (Figure 2). The subthemes are described below.

Cognitive Dissonance and Becoming Overwhelmed With Emotions

Relatives described the sudden and unexpected occurrence of illness as a surreal situation from which they wanted to escape (de Groot et al., 2016; Manuel et al., 2010; Walker & Sque, 2016; Yousefi et al., 2014). They experienced feelings of shock and distrust, and sometimes had difficulty understanding information, with a feeling that their loss was overwhelming (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014; Manuel et al., 2010; Neate et al., 2015; Yousefi et al., 2014). Furthermore, the relatives experienced feelings of denial, guilt, fear, helplessness, anger, and confusion when they understood the seriousness of the situation (Jensen, 2016; Walker & Sque, 2016). They thought and hoped that recovery was possible, especially if their loved one was young (Yousefi et al., 2014). Hearing that recovery was not possible often came as a shock (Marck et al., 2016). The relatives reveal the difficulty accepting that brain death means finiteness (da Silva Knihs et al., 2015).

It was difficult to receive a great deal of information in a short period of time understanding brain death, due to the experience of a “living body,” for instance, a beating heart and a warm body (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014; da Silva Knihs et al., 2015; Fernandes et al., 2015; Gyllstrom Krekula et al., 2018; Manuel et al., 2010; Manzari, Mohammadi, Heydari, Aghamohammadian Shearbaff, et al., 2012; Marck et al., 2016; Neate et al., 2015). Others expressed that they understood the information, but when they saw their loved one warm and normal, skepticism arose in them regarding the diagnosis of brain death (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014; de Groot et al., 2016). Other reasons for difficulty understanding brain death included the presence of a mechanical ventilator and the fact that their loved one looked the same (Gyllstrom Krekula et al., 2018), often with an absence of visible bodily injury (Yousefi et al., 2014). Relatives had difficulty determining when brain death had actually occurred (de Groot et al., 2016; Gyllstrom Krekula et al., 2018). Being present at the hospital and seeing that the care provided did not produce results facilitated their understanding of the gravity of the situation (Yousefi et al., 2014).

Relatives had difficulty distinguishing between brain death and coma (Fernandes et al., 2015; Manzari, Mohammadi, Heydari, Aghamohammadian Shearbaff, et al., 2012; Marck et al., 2016). Some said they did not feel comfortable with the concept of brain death (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014; Marck et al., 2016; Neate et al., 2015). Information had to be based on individual needs, and mistrust arose when too little information was given (Fernandes et al., 2015; Yousefi et al., 2014). Relatives wanted to know if the brain death was irreversible, and why it had occurred (Manzari, Mohammadi, Heydari, Aghamohammadian Shearbaff, et al., 2012; Yousefi et al., 2014). An understanding of brain death was facilitated for relatives if graphic illustrations such as a computed tomography scan of the brain were shown or if the relatives were present during neurological tests (Manzari, Mohammadi, Heydari, Aghamohammadian Shearbaff, et al., 2012; Marck et al., 2016; Walker & Sque, 2016). Furthermore, it facilitated the relatives’ consent to donation when they experienced the request as empathetic (Manuel et al., 2010).

Interacting With Healthcare Professionals

Relatives described healthcare professionals as supportive, caring, and empathetic, which gave them confidence and satisfaction (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014; Fernandes et al., 2015; Manuel et al., 2010; Marck et al., 2016; Walker & Sque, 2016). Direct and honest information, without false hope, and repeated information were appreciated (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014; Kim et al., 2014; Marck et al., 2016; Sque et al., 2018; Walker & Sque, 2016). Relatives also appreciated being addressed by name (Marck et al., 2016). Relatives lacked an understanding of the donation process and experienced it as complex (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014; Marck et al., 2016). When consent was given, the relatives needed to know that the care would be continued, as well as its purpose (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014). Sometimes, they did not understand whether the care was for the patient or for donation purposes (Gyllstrom Krekula et al., 2018). Some expressed the importance of careful care being continued until the end (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014; Manuel et al., 2010).

Some relatives described that healthcare professionals did not inform them clearly which created distrust, and that it was too late to question the process when they received the request concerning donation (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014; Manuel et al., 2010; Manzari, Mohammadi, Heydari, Aghamohammadian Shearbaff, et al., 2012; Yousefi et al., 2014). A sense of frustration and confusion arose if the healthcare professionals conveyed hope when they knew the situation was hopeless (Marck et al., 2016). Some relatives lacked information about when the mechanical ventilator would be turned off, and about the surgery (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014; Manzari, Mohammadi, Heydari, Aghamohammadian Shearbaff, et al., 2012). Some felt anxiety over the surgery (Gyllstrom Krekula et al., 2018). When consent to donation was given, some relatives noted that the attitude of the healthcare professionals changed for the better (Manzari, Mohammadi, Heydari, Aghamohammadian Shearbaff, et al., 2012). Relatives appreciated being able to return to the ICU after surgery for a final farewell (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014). Some relatives described that after donation, they did not receive the support they needed (Fernandes et al., 2015; Manzari, Mohammadi, Heydari, Aghamohammadian Shearbaff, et al., 2012; Yousefi et al., 2014). Questions and concerns often appear weeks after the donation had taken place (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014; Manzari, Mohammadi, Heydari, Aghamohammadian Shearbaff, et al., 2012; Marck et al., 2016). The relatives also described feelings of guilt, sadness, and anxiety (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014; Manuel et al., 2010; Manzari, Mohammadi, Heydari, Aghamohammadian Shearbaff, et al., 2012). Many expressed the need for follow-up conversations, but few were given the opportunity (Fernandes et al., 2015; Marck et al., 2016).

Being in a Complex Decision-Making Process

For some relatives, the donation request came unexpectedly, while others raised the issue themselves (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014; Marck et al., 2016; Sque et al., 2018). Some suggested leaflets discussing organ donation being made available at the ICU, to facilitate the decision if the request should come (de Groot et al., 2016). Some said the donation request had come too quickly, while others wished they had been asked earlier (Neate et al., 2015). When the request came unexpectedly, relatives perceived it as overwhelming (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014; Fernandes et al., 2015). Others said that they felt thankful when the request was made carefully (Walker & Sque, 2016). If the donation was cancelled, the relatives could feel disappointed (Marck et al., 2016; Walker & Sque, 2016).

Some relatives expressed a need to separate the death from the donation decision (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014). Some described that their decision was facilitated if the will of the deceased was known and that it was important to follow the will of the deceased (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014; Manuel et al., 2010; Neate et al., 2015; Sque et al., 2018; Walker & Sque, 2016; Yousefi et al., 2014). Furthermore, some relatives described a sense of responsibility and a moral obligation to the patients awaiting transplantation (Kentish-Barnes et al., 2019).

The desire and willingness of the patient to be a donor was the most frequent reason organs were donated (34%), followed by the advice of family or friends (31%; Kim et al., 2014). If the donation request was made several times, it could be perceived as annoying (Neate et al., 2015). If the deceased had no expressed will, relatives referred to their personal attributes such as kindness or generosity (Manuel et al., 2010; Neate et al., 2015). Altruistic, spiritual, and religious beliefs affected the relatives’ decision making (Yousefi et al., 2014). Reasons why relatives refused donation included physical and emotional fatigue, and the desire to be present when mechanical ventilation was ceased (Neate et al., 2015). Relatives who did not have confidence in the brain death diagnosis had a more intense grief reaction (p = .020) and more serious depressive symptoms (p = .002) 3 to 6 months after the donation, than did those who felt confident (Smudla et al., 2012).

Relatives who took a donor stance felt more supported by clinicians (p < .001), compared with relatives who took a nondonor stance (Kentish-Barnes et al., 2018). Concerning satisfaction with the donation process, the decision moment was rated the highest, followed by the offers of information, whereas satisfaction with the actual donation procedure was the lowest (Kim et al., 2014).

The Need for Proximity and Privacy

Spending time with the deceased in the ICU was important for the relatives to be able to say goodbye to their loved one (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014). For some relatives, consenting to donation was a strategy to allow the family members to have more time to say goodbye (Manuel et al., 2010). Relatives described a strong feeling of protecting the deceased person’s body (Sque et al., 2018). The period between signing the consent form and the actual transfer of the body was a difficult time for the relatives (Manzari, Mohammadi, Heydari, Aghamohammadian Shearbaff, et al., 2012).

It was also important to relatives that they were not confined to a waiting room shared with other patients’ relatives, as they needed privacy in a calm place in order to reflect and grieve (Jensen, 2016; Sque et al., 2018). For some relatives, the process of saying goodbye began immediately when their loved one was collapsing, for others when they received the information, and for yet others during the donor operation (Gyllstrom Krekula et al., 2018). Some relatives also requested a quicker process for the delivery of the body to the family for burial (Manzari, Mohammadi, Heydari, Aghamohammadian Shearbaff, et al., 2012).

Feeling Hope for the Future

Relatives expressed a feeling of hope throughout the process; initially, there was hope for recovery, and in some cases, even after the patient had been declared brain dead (Fernandes et al., 2015; Jensen, 2016; Walker & Sque, 2016). Some felt hope for recovery as long as the medical interventions were ongoing (Manuel et al., 2010). Relatives described a change in their hope from dealing with survival to the opposite—a worthy death (Jensen, 2016). The possibility of organ donation also involved a feeling of hope, that their loved one’s life not had been wasted (Jensen, 2016; Sque et al., 2018; Walker & Sque, 2016). The donation offered help in their grief and gave them pride, trust, and hope (Jensen, 2016; Kim et al., 2014; Manzari, Mohammadi, Heydari, Sharbaf, et al., 2012; Marck et al., 2016). Knowing about the outcome of the donation created different feelings; some felt it was bittersweet to have this knowledge (Walker & Sque, 2016).

Relatives expressed that the knowledge of their loved one living on through the recipients was a positive memory (Berntzen & Bjørk, 2014; Jensen, 2016; Kentish-Barnes et al., 2019; Manuel et al., 2010; Neate et al., 2015; Sque et al., 2018; Walker & Sque, 2016). After the donation, closeness to God, religious practices, and spending time with family and friends were helpful for psychological stress relief (Kim et al., 2014; Manzari, Mohammadi, Heydari, Sharbaf, et al., 2012; Yousefi et al., 2014). When asked 1 year later, no relative who accepted donation regretted his or her decision, whereas two among eight relatives of nondonor patients did express doubt about their decision, and feelings of guilt (Kentish-Barnes et al., 2019).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to describe relatives’ experiences, when a family member was confirmed brain dead and became a potential organ donor. The overarching theme When life ceases emerged as a description of relatives’ experiences during the donation process including five subthemes. Cognitive dissonance and becoming overwhelmed with emotions, interacting with healthcare professionals, being in a complex decision-making process, the need for proximity and privacy, and feeling hope and relief. The relatives described their loved one’s illness as occurring dramatically. In order for healthcare professionals to offer adequate support, it is important to have knowledge about the grieving process to be able to facilitate the relative’s understanding of death as far as possible. Professionals need to communicate to relatives that all reactions—except violence—are accepted, and that the grief process is individual. The denial phase often occurs initially, with reactions such as panic, outrage, indifference, and shielding (Kübler-Ross, 1969). Relatives can look calm but may be experiencing chaos under the surface. Kübler-Ross (1969) describes reactions such as anger, guilt, and fear, whereby relatives may blame themselves for what happened to their family member. This tallies with the descriptions given by relatives, of denial, guilt, fear, anger, and confusion. Healthcare professionals need to be aware of these reactions, so that the behaviors of relatives in the form of anger and aggression do not lead to a loss of care. Relatives sometimes had difficulty understanding the concept of brain death, because their family member’s body was technically still functioning, and looked whole and alive. Understanding of the death was facilitated if the relatives were included, for instance being allowed to look at graphic illustrations such as a computed tomography scan of the brain. The relatives emphasized the importance of time and the possibility to say goodbye to their loved one, with some expressing that the deceased was both present and absent. We emphasize the importance of creating time and circumstances for the relatives to bid farewell. The relatives requested a calm place or waiting room to reflect and grieve, away from the relatives of other patients in the ICU. This is natural, as these relatives had been faced with the worst imaginable scenario as their loved one’s life had ceased. Furthermore, it is essential that healthcare professionals tailor interventions for the uniqueness of the person, their relationship and circumstances, as there is no “one-size-fits-all” model or approach to grief (Hall, 2014).

Some relatives described that the donation request had come unexpectedly and surprisingly, while others raised the issue themselves. An Australian study emphasizes the need for staff members to collaborate and be open-minded during the donor process (Thomas et al., 2009). Studies describe how trained pro-donation and donation practitioners affect the consent rate positively (Jansen et al., 2011; Sanner, 2007). Another study indicates that ICU nurses in university hospitals with short working experience have the least positive attitudes toward donor advocacy, which is problematic as many potential organ donation patients are in university hospitals (Forsberg et al., 2015). The caregiver’s seniority, and the training he or she has received, plays an essential role in how he or she will apprehend family members. Knowledge of their family member’s willingness to donate or not facilitated the relatives’ decision. This knowledge is a reminder to state, whether we are positive or negative to donating if we end up in such a situation. It might be interesting to compare studies in relation to beliefs and ethnic origins, because the relationship to death can differ between these groups.

This is also interesting from a gender perspective, as a recent Swedish study describes that women are more likely to become donors than men are (Nolin et al., 2017). We can only speculate that women may generally be more involved in the family and take a stand on important issues more than men do.

For the relatives, the donation could be a positive aspect of an otherwise tragic situation and lighten their memories of the events. They described the importance of the healthcare professionals being honest. Healthcare professionals sometimes avoid talking about death and instead act hopeful, which can create false hope (Keshtkaran et al., 2016). Relatives described a reduced ability to acquire information, which is a common reaction in the denial phase (Kübler-Ross, 1969). Information and the opportunity to ask questions are necessary in order to avoid misinterpretations. Healthcare professionals state that they can be both open and reluctant to providing information to relatives when forecasting the patient's deterioration, but sometimes experience it as easier to care for patients when their family is not present (Oroy et al., 2015). This was contrary to the relatives’ wishes, which emphasizes the importance of being present at the ICU and receiving constant, understandable information. A Swedish study describes that nurses were rarely present when the physician informed patients’ families (Lind et al., 2012). This is unfortunate, as an experienced and engaged nurse can be a key part of the multidisciplinary organ donor team. Therefore, a nurse should be present when prognosis information and the declaration of death are given and when the donation request is made, because nurses often work closest to the patient and their family. This is in accordance with an English study that emphasizes the importance of including a special donor coordinator when requesting consent for organ donation (Vincent & Logan, 2012).

The relatives experienced hope throughout the process, first for recovery and then for something else, expressed as a feeling of confidence, and a wish that their family member’s body would cope until the donation operation had been performed. A time after their loved one’s death, the donation gave them a sense of honor and pride, in accordance with Kübler-Ross’ (1969) final phase, acceptance, in which the person can look back on the situation as a painful memory, but with understanding. In order for healthcare professionals to be able to provide optimal support for the patient’s relatives, they need knowledge about the relatives’ experience during the donation process. Relatives can experience disappointment if the donation they had consented to ultimately does not take place. Thus, it is important that information be conveyed that the donation may not occur due to issues such as body quality or forensic investigations (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2018). For healthcare professionals, it is essential to address the relatives’ needs and adapt their message to individual circumstances (de Groot et al., 2016). It is also important to show understanding and respect regardless of whether the relatives consent to donation or not.

A Dutch study describes that whether the relatives consent to the organ donation or not, the grieving process is not impacted; rather it is dissatisfaction with the healthcare that is associated with symptoms of depression and grief (Cleiren & Zoelen, 2002). Relatives raised questions after the ICU stay and expressed a need for follow-up. This is in line with other research on relatives’ needs after a loved one’s ICU stay (Frivold et al., 2016). Therefore, we strongly recommend that follow-up meetings be offered after a donation process. For some, it may be necessary to do this repeatedly. It could also be interesting to have a post-interview evaluation grid. Another useful way to help relatives in their processing and understanding is the use of an ICU diary (Johansson et al., 2018).

Limitations and Strengths

The current review had several limitations. First, the studies were from Australia, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, France, Hungary, Iran, Korea, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and United Kingdom, which have different healthcare systems; thus, this could be a weakness regarding validity. However, many findings turned out to be equivalent regardless of country, which strengthens the transferability. Second, the methods of the 15 interviews studies differed, depending on if they were carried out in one or more stages, who attended, the locale for the interview, and how far after the event they were conducted. Third, in three of the studies, relatives’ experiences involved donors after both Donation after Brain Death and Donator after Circulatory Death; however, since many countries currently have both, this strengthens the transferability. Fourth, there may be a limitation regarding the low number of studies included; however, the results are based on interviews with a high number of participants, which strengthens the validity. With a different methodology, for instance using interviews, the results might be more distinct, in depth regarding relatives’ experiences, and provided opportunities to ask any supplementary questions. Strength was that all included studies had received ethical approval, and another strength was that 14 of the studies were published in 2014 or after.

Conclusions and Suggestions for Future Direction

The experiences of relatives of potential organ donors are essential for healthcare professionals to be able to provide optimal support to them before, during, and after the donation process. This study further speaks for follow-up for relatives of patients who had the donation request raised, to enable them to process their loss and carry on with life. This knowledge is also essential for the public, as the need for future potential donors is comprehensive.

The current state-of-the-art science of organ donor suggests that a clinical study aimed at describing ICU nurses’ experience of caring for potential organ donors may be useful. We hope that this effort will help to identify a solution for developing effective intervention strategies, in order to provide better conditions for the donor patient and their relatives.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank ICU nurse Jenny Olofsson who started the literature search, and gave valuable input throughout the process.

Author Contributions

Birgitta Kerstis drafted the manuscript and coordinated the research group. Margareta Widarsson contributed to the analysis and revised the article for important intellectual content. Both authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Birgitta Kerstis https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0242-0343

References

- Berntzen H., Bjørk I. T. (2014). Experiences of donor families after consenting to organ donation: A qualitative study. Intensive Critical Care Nursing, 30(5), 266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleiren M. P., Zoelen A. J. (2002). Post-mortem organ donation and grief: A study of consent, refusal and well-being in bereavement. Death Studies, 26(10), 837–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). (2010). Caps checklists: 10 questions to help you make sense of systematic. http://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- da Silva Knihs N., Leitzke T., de Aguiar Roza B., Schirmer J., Domingues M., Arena T. J. C. (2015). Understanding the experience of family facing hospitalization, brain death, and donation interview. Cuidado e Saude, 14(4), 1520–1527. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg K., Dahlberg H., Nyström M. (2007). Reflective lifeworld research (2nd ed.). Studentlitteratur AB.

- de Groot J., van Hoek M., Hoedemaekers C., Hoitsma A., Schilderman H., Smeets W., Vernooij-Dassen M., van Leeuwen E. (2016). Request for organ donation without donor registration: A qualitative study of the perspectives of bereaved relatives. BMC Medical Ethics, 17(1), 38 10.1186/s12910-016-0120-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes M. E., Bittencourt Z. Z., Boin I. F. (2015). Experiencing organ donation: Feelings of relatives after consent. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 23(5), 895–901. 10.1590/0104-1169.0486.2629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg A., Lennerling A., Fridh I., Rizell M., Lovén C., Flodén A. (2015). Attitudes towards organ donor advocacy among Swedish intensive care nurses. British Association of Critical Care Nurses, 20(3), 126–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frivold G., Slettebø Å., Dale B. (2016). Family members’ lived experiences of everyday life after intensive care treatment of a loved one: A phenomenological hermeneutical study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(3–4), 392–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyllstrom Krekula L., Forinder U., Tibell A. (2018). What do people agree to when stating willingness to donate? On the medical interventions enabling organ donation after death. PLoS One, 13(8), e0202544 10.1371/journal.pone.0202544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall C. (2014). Bereavement theory: Recent developments in our understanding of grief and bereavement. Cruse Bereavement Care, 33(1), 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen N. E., van Leiden H. A., Haase-Kromwijk B. J., van der Meer N. J., Kruijff E. V., van der Lely N., van Zon H., Meinders A.-J., Mosselman M., Hoitsma A. J. (2011). Appointing ‘trained donation practitioners’ results in a higher family consent rate in the Netherlands: A multicenter study. European Society for Organ Transplantation, 24(12), 1189–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen A. M. (2016). “Make sure somebody will survive from this”: Transformative practices of hope among Danish organ donor families. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 30(3), 378–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson M., Wåhlin I., Magnusson L., Runeson I., Hanson E. (2018). Family members’ experiences with intensive care unit diaries when the patient does not survive. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 32(1), 233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsson C., Tufvesson G. (2001). Transplantation. Studentlitteratur AB. [Google Scholar]

- Kentish-Barnes N., Chevret S., Cheisson G., Joseph L., Martin-Lefevre L., Si Larbi A. G., Viquesnel G., Marqué S., Donati S., Charpentier J., Pichon N., Zuber B., Lesieur O., Ouendo M., Renault A., Le Maguet P., Kandelman S., Thuong M., Floccard B., Mezher C., … Azoulay E. (2018). Grief symptoms in relatives who experienced organ donation requests in the ICU. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 198, 751–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentish-Barnes N., Cohen-Solal Z., Souppart V., Cheisson G., Joseph L., Martin-Lefevre L., Si Larbi A. G., Viquesnel G., Marqué S., Donati S., Charpentier J., Pichon N., Zuber B., Lesieur O., Ouendo M., Renault A., Le Maguet P., Kandelman S., Thuong M., Floccard B., … Azoulay E. (2019). Being convinced and taking responsibility: A qualitative study of family members’ experience of organ donation decision and bereavement after brain death. Critical Care Medicine, 47(4), 526–534. 10.1097/ccm.0000000000003616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshtkaran Z., Sharif F., Navab E., Gholamzadeh S. (2016). Lived experiences of Iranian nurses caring for brain death organ donor patients: Caring as “Halo of ambiguity and doubt”. Global Journal of Health Science, 8(7), 281–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. S., Yoo Y. S., Cho O. H. (2014). Satisfaction with the organ donation process of brain dead donors’ families in Korea. Transplantation Proceedings, 46(10), 3253–3256. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.09.094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kübler-Ross E. (1969). On death and dying. Tavistock Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Lind R., Lorem G. F., Nortvedt P., Hevroy O. (2012). Intensive care nurses’ involvement in the end-of-life process–perspectives of relatives. Nursing Ethics, 19(5), 666–676. 10.1177/0969733011433925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuel A., Solberg S., MacDonald S. (2010). Organ donation experiences of family members. Nephrology Nursing Journal: Journal of the American Nephrology Nurses’ Association, 37(3), 229–236; quiz 237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzari Z. S., Mohammadi E., Heydari A., Aghamohammadian Shearbaff H. R., Modabber Azizi M. J., Khaleghi E. (2012). Exploring the needs and perceptions of Iranian families faced with brain death news and request to donate organ: A qualitative study. International Journal of Organ Transplantation Medicine, 3(2), 92–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzari Z. S., Mohammadi E., Heydari A., Sharbaf H. R., Azizi M. J., Khaleghi E. (2012). Exploring families’ experiences of an organ donation request after brain death. Nursing Ethics, 19(5), 654–665. 10.1177/0969733011423410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marck C. H., Neate S. L., Skinner M., Dwyer B., Hickey B. B., Radford S. T., Weiland T. J., Jelinek G. A. (2016). Potential donor families’ experiences of organ and tissue donation-related communication, processes and outcome. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, 44(1), 99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M., Shekelle P., Stewart L. A., & Prisma-P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4, 1 https://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neate S. L., Marck C. H., Skinner M., Dwyer B., McGain F., Weiland T. J., Hickey B. B., Jelinek G. A. (2015). Understanding Australian families’ organ donation decisions. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, 43(1), 42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolin T., Mardh C., Karlstrom G., Walther S. M. (2017). Identifying opportunities to increase organ donation after brain death. An observational study in Sweden 2009–2014. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 61(1), 73–82. 10.1111/aas.12831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oroy A., Stromskag K. E., Gjengedal E. (2015). Do we treat individuals as patients or as potential donors? A phenomenological study of healthcare professionals’ experiences. Nursing Ethics, 22(2), 163–175. 10.1177/0969733014523170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanner M. A. (2007). Two perspectives on organ donation: Experiences of potential donor families and intensive care physicians of the same event. Journal of Critical Care, 22(4), 296–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scandiatransplant. (2019). Welcome to Scandiatransplant http://www.scandiatransplant.org

- Smudla A., Hegedűa K., Mihály S., Szabó G., Fazakas J. (2012). The HELLP concept—Relatives of deceased donors need the help earlier in parallel with loss of a loved. Annals of Transplantation, 17(2), 18–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socialstyrelsen (The National Board of Health and Welfare). (2018). Organ- och vävnadsdonatorer i Sverige 2017 (Organ and tissue donors in Sweden 2017). https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2018-6-22.pdf

- Sque M., Walker W., Long-Sutehall T., Morgan M., Randhawa G., Rodney A. (2018). Bereaved donor families’ experiences of organ and tissue donation, and perceived influences on their decision making. Journal of Critical Care, 45, 82–89 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S., Milnes S., Komesaroff P. J. (2009). Understanding organ donation in the collaborative era: A qualitative study of staff and family experiences. Internal Medicine Journal, 39(9), 588–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent A., Logan L. J. (2012). Consent for organ donation. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 108(suppl_1), i80–i87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker W., Sque M. (2016). Balancing hope and despair at the end of life: The contribution of organ and tissue donation. Journal of Critical Care, 32, 73–78. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R., Knafl K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi H., Roshani A., Nazari F. (2014). Experiences of the families concerning organ donation of a family member with brain death. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 19(3), 323–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]