Abstract

Introduction

Caregivers of persons with dementia experience challenges that can make preparing for end-of-life particularly difficult. Feeling prepared for death is associated with caregiver well-being in bereavement and is promoted by strategies supporting a palliative approach. Further conceptualization of caregiver preparedness for death of persons with dementia is needed to guide the practice of healthcare providers and to inform development of a preparedness questionnaire.

Objectives

We aimed to: 1) explore the end-of-life experiences of caregivers of persons with dementia to understand factors perceived as influencing preparedness; and 2) identify the core concepts (i.e., components), barriers and facilitators of preparedness for death.

Methods

This study used an interpretive descriptive design. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with sixteen bereaved caregivers of persons with dementia, recruited from long-term care homes in Ontario. Data was analyzed through reflexive thematic analysis.

Findings

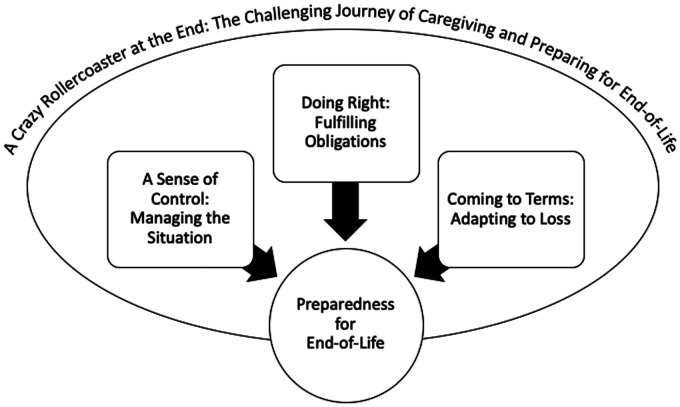

Four themes were interpreted including: ‘A crazy rollercoaster at the end’ which described the journey of caregivers at end-of-life. The journey provided context for the development of core concepts (i.e., components) of preparedness represented by three themes: ‘A sense of control, ‘Doing right’ and ‘Coming to terms’.

Conclusion

The study findings serve to expand the conceptualization of preparedness and can guide improvements to practice in long-term care. Core concepts, facilitators and influential factors of preparedness will provide the conceptual basis and content to develop the Caring Ahead: Preparing for End-of-Life with Dementia questionnaire.

Keywords: caregiver, chronic illnesses, death preparedness, death/dying, dementia, palliative care

Family/friend caregivers of persons with dementia [PWD] experience challenges in the caregiving journey that can make preparing for death particularly difficult. The early introduction of a palliative approach focused on optimizing quality-of-life while preparing for end-of-life [EOL] is recommended (van der Steen et al., 2014). A palliative approach aims to promote caregiver feelings of death preparedness, a complex multi-dimensional, dynamic concept associated with well-being in bereavement. In this study, we explored the EOL experiences of caregivers of PWD living in long-term care settings to understand preparedness for death. The findings contributed to the conceptualization of death preparedness and will be used to inform development of the Caring Ahead: Preparing for EOL with Dementia questionnaire.

Literature Review

An estimated 50 million persons worldwide are living with dementia, a neurocognitive, unpredictable and often progressive disorder that can impair memory, thinking, mobility and personality (Mitchell et al., 2009; World Health Organization, 2019). The majority of care for PWD is delivered by family/friends who provide an increasing amount of emotional, physical and financial support as dementia progresses (World Health Organization, 2019). Positive experiences and benefits of caregiving include feeling needed and having purpose, reciprocating care, skill development and personal growth (Quinn & Toms, 2018). However, caregiving is also associated with negative physical and mental health symptoms pre and post-bereavement, burden and increased health-care utilization by caregivers (Bremer et al., 2015; Watson et al., 2018).

Burden, depression and anxiety are reported as significantly higher (p < 0.001) amongst caregivers of PWD than other caregivers (Harding et al., 2015; Karg et al., 2018; Romero et al., 2014). In addition, negative symptoms and burden accumulate as dementia advances and can influence bereavement (Costa-Requena et al., 2015). Up to 20% of caregivers experience complicated grief (i.e., intrusive thoughts inhibiting function) after the death of a PWD, compared to only 3.7% of the general population (Hebert et al., 2006a; Kersting et al., 2011). The high prevalence of mental health concerns amongst caregivers of PWD demonstrates a major health disparity.

There is promising evidence that outcomes for caregivers and the quality-of-dying for PWD is improved when caregivers feel more prepared for EOL (van der Steen et al., 2013). However, between 53 and 67% of caregivers of persons with neurodegenerative diseases feel unprepared for death (Terzakis, 2019). ‘Death preparedness’ (i.e., awareness and readiness for death) is modifiable through interventions and predicts caregiver outcomes in bereavement such as, complicated grief, depression and anxiety (Barry et al., 2002; Caserta et al., 2019; Hebert et al., 2006a). Relationships between communication with healthcare providers and complicated grief (adj Odds Ratio [OD] 0.8, 95%CI 0.4,1.5), as well as between advance care planning (i.e., conversations about goals and wishes for care) and death preparedness (B = 0.27, 95% CI 0.1,0.45) have been demonstrated that should be leveraged to guide improvements in care (Nielsen et al., 2016; Schulz et al., 2015).

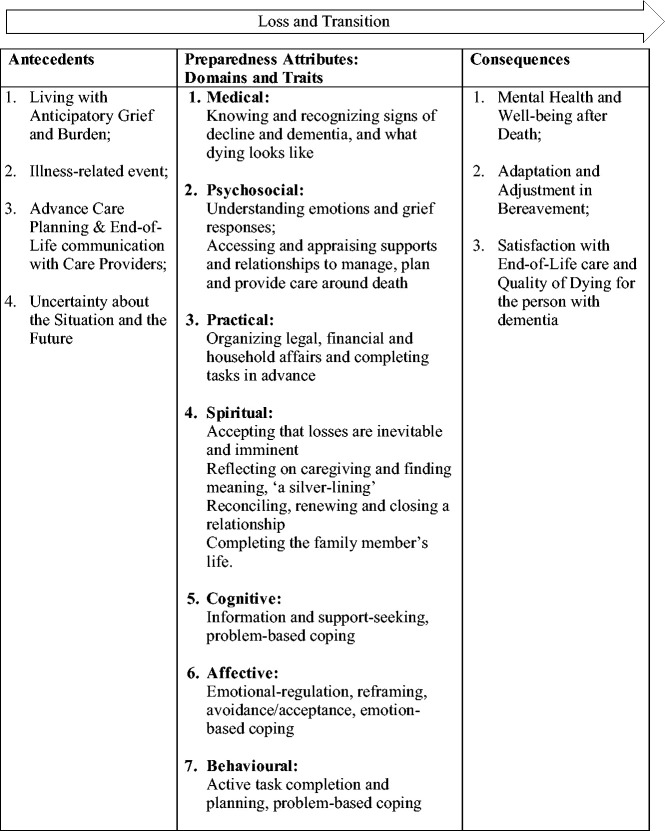

Altogether, there is strong evidence that promoting preparedness for death in caregivers of PWD has positive impacts and should therefore be an aspect and quality indicator for EOL care. However, limitations exist in the conceptualization, definition and measurement of preparedness for death. Reviews of preparedness studies and instruments have found that the concept of caregiver preparedness for death for PWD is often not defined and existing instruments have limited conceptual adequacy (Durepos et al., 2019; Nielsen et al., 2016; Terzakis, 2019). To address these gaps, we conducted a concept analysis of death preparedness for caregivers of PWD using literature, developed a theoretical definition and the ‘Caregiver Preparedness for End-of-Life of Persons with Dementia’ model (see Figure 1) (Durepos et al., 2018). The new model built upon and integrated the ‘Theoretical Framework of Preparedness’ developed by Hebert et al. (2006b).

Figure 1.

‘Caregiver Preparedness for End-of-Life in Dementia’ Model.

Note from: Durepos et al., (2018) What does death preparedness mean for family caregivers of persons with dementia? American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care, X(X), 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909118814240; and Durepos et al., (2019) Caregiver preparedness for death in dementia: An evaluation of existing tools. Aging and Mental Health, https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1622074

Based on this new model, preparedness is defined as, “a self-perceived cognitive, affective and behavioural quality or state of readiness to maintain self-efficacy and control in the face of loss” (Durepos et al., 2018). The concept is described as having seven attributes across medical, psychosocial, spiritual and practical domains (Hebert et al., 2006b; Durepos et al., 2018). Cognitive (knowledge, information), affective (emotional-regulation, attitude, support) and behaviours (skills, actions) are described as traits underlying the concept, promoted through problem and emotion-based coping strategies (Hebert et al., 2006b; Durepos et al., 2018). Strategies such as EOL discussions are theorized as reducing uncertainty, enhancing preparedness for changes, needs and losses within domains, and promoting caregiver well-being in bereavement (Hebert et al., 2006a; Durepos et al., 2018). Caregiver death preparedness is therefore a holistic quality indicator/outcome for strategies supporting a palliative approach and EOL care.

Aims

The aims of this qualitative study were to identify the core concepts of preparedness for death amongst caregivers of PWD and to understand influential factors, facilitators and barriers. Study implications are particularly relevant for nurses and healthcare providers practicing a palliative approach in long-term care where the majority of PWD experience EOL. This study represented phase one of a mixed methods study (qual->QUAN) to develop and evaluate the ‘Caring Ahead: Preparing for EOL with Dementia” questionnaire (Creswell et al., 2011). Research questions included: 1) What are the experiences of caregivers of PWD during EOL, and what factors influence preparedness for death? 2) What are the core concepts (i.e., components), facilitators and barriers to preparedness for death?

Methods

Design

This study used an interpretive descriptive design (Thorne, 2016) as it is appropriate for exploring a phenomenon relevant to clinical practice and aims to produce a coherent conceptual description of a phenomenon applicable to practice. The authors are members of health disciplines (nursing and social work) and this study emerged from clinical practice with PWD and caregivers in long-term care. Interpretive description assumes the existence of multiple realities constructed through social interactions with the world and influenced by context (Thorne, 2016). The research approach was loosely based on constructive realism and the authors assumed they were interacting with participants to create a representation of preparedness by describing the underlying, common and shared patterns in their experiences (Cupchik, 2001; Thorne, 2016). Pre-existing theoretical knowledge informed sampling and data collection in this study, but the analysis was inductive with the end study-product grounded in the data (Thorne, 2016).

Sampling

Purposive sampling, including criterion, maximum variation and snowball sampling strategies, was used to recruit a sample of bereaved caregivers of PWD to act as information-rich cases from long-term care settings (i.e., 24-hour residential care facilities) in Central Ontario (Patton, 2015; Thorne, 2016). Participants were recruited with the following criteria: 1) English-speaking adults over 18 years old; 2) bereaved between 3 to 24 months, who previously provided: 3) unpaid, emotional, physical or financial care; 4) to a family member/friend with dementia residing in long-term care. Participants with diverse characteristics (e.g., gender, relationship) known to influence caregiving and EOL experiences were recruited for maximum variation (Patton, 2015; Schulz et al., 2015; Thorne, 2016). All participants resided in Canada. However the majority of Canadians report having beliefs and traditions influencing EOL experiences that stem from an additional ethnic origin (Ontario Palliative Care Network, 2019).

Recruitment

Staff members in two long-term care homes (i.e., Director of Care and administrative assistant) and an educator with the local Alzheimer Society assisted with recruitment by posting flyers in their settings and by contacting bereaved caregivers known to them by email or telephone to let them know about the study (Patton, 2015). Participants were offered a $25 gift card as an incentive. To minimize researcher intrusion, interested participants contacted us or gave permission to staff to share their contact information (Roberts & McGilloway, 2011). Recruited participants let other persons who met the inclusion criteria know about the study which facilitated snowball sampling (Patton, 2015). Sampling continued until the data became redundant (Thorne, 2016).

Data Collection and Analysis

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by the lead author (P.D.) in the participants’ preferred location (i.e., home or by telephone) from June to September 2018. P.D. is a nurse (PhD student) with specialty training in a palliative approach, counselling and experience conducting research interviews about EOL. An iterative interview guide was used to explore experiences at EOL and perceptions of preparedness, with questions organized around domains of the existing Preparedness Model (see Supplement) (Hebert et al., 2006a; Durepos et al., 2018; Thorne, 2016). The interviews lasted 30 to 90 minutes. P.D. recorded field notes during interviews to capture data about participants’ moods, emphasized concepts and recorded a reflective note in her reflexive journal to record personal reactions immediately following the interview (Braun et al., 2014). Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, identifying information was removed and transcripts were proofed for accuracy against the recording (Patton, 2015).

Data analysis began concurrent with data collection as P.D. was immersed in the data, listened repeatedly to interview recordings, and recorded emerging patterns in her field notes and journal. Meaningful participant quotations within transcripts were defined as the units of analysis (Elo et al., 2014).The authors used an inductive data-driven approach to analyze the data (Thorne, 2016) and followed the six-steps of reflexive thematic analysis: 1) becoming familiar with the data by reading and re-reading transcripts; 2) generating initial surface-level codes to organize and describe the data within transcripts; 3) searching for common, underlying patterns across the data-set and collating initial codes into themes that went beyond the surface-level; 4) reviewing the themes in relation to the data; 5) defining and labelling themes with details and the overarching narrative; and 6) reporting the findings (Braun et al., 2014). The authors each analyzed three transcripts independently until they had generated and reviewed themes (i.e., step 4) (Braun et al., 2014; Patton, 2015). The authors then met together, discussed and compared their findings and defined preliminary themes based on consensus.

Using the themes as codes, P.D. proceeded to analyze all of the remaining transcripts using QSR’s NVIVO 12.0 qualitative analysis software. P.D. developed new codes to reflect the data as needed and clarified/modified the themes to produce a coherent conceptual description of preparedness core concepts, facilitators, barriers and influential contextual factors. P.D. met frequently with the study authors during analysis over the next three months to ensure the findings were data-driven (Elo et al., 2014; Thorne, 2016).

Trustworthiness

To enhance conformability and ensure the findings were data-driven we critically reflected on our assumptions and potential influences on the research process. As the lead author P.D., also critically reflected on her role as the research instrument to ensure the interview questions were not leading, recorded her reactions to the data in a reflexive journal and debriefed with another author (Elo et al., 2014). The authors maintained an audit trail of decisions made regarding the study design, sampling, data collection and analysis for transparency and dependability (Elo et al., 2014). Credibility of the findings was promoted through the independent analysis of transcripts by all authors for researcher triangulation (Elo et al., 2014).

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (#4503). Written informed consent was obtained prior to each interview. Sensitive interviewing techniques were employed including: frequent breaks and/or discontinuation of the interview if needed, a list of supportive resources provided at the end of the interview, validation of emotions availability of the interviewer for follow-up and connection to additional resources if needed) (Brayda & Boyce, 2014; Roberts & McGilloway, 2011). All of the participants demonstrated emotions during the interview (e.g., crying, sadness), however no participants wanted to end the interview. The majority of participants expressed that completing the interview was beneficial to their well-being and was a rewarding way to help caregivers.

Findings

A sample of 16 bereaved caregivers, primarily adult-children (70%) of PWD (i.e., care recipients) who were deceased were interviewed (see Table 1). The overarching theme, ‘A Crazy Roller Coaster at the End’ described the challenging journey that caregivers experience leading up to death and provides context for the development of core concepts (i.e., components) of preparedness for EOL. Three additional themes represented inter-connected core concepts comprising preparedness. ‘A Sense of Control’ managing the situation focused on the PWD and meeting their needs. ‘Doing Right’ fulfilling obligations focused on societal needs and customs at EOL. ‘Coming to Terms’ adapting to loss focused on the caregiver themselves. Figure 2 displays the three core concepts comprising preparedness that were developed (and influenced) by the context of the caregiving journey.

Table 1.

Participant Sample (n = 16).

| Characteristic | N (%) | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CG Gender | Male | 7 (43.75) | |

| Female | 9 (56.25) | ||

| CG Age (years) | 60 (11.5) | ||

| CG Relationship to deceased | Spouse | 3 (18.75) | |

| Adult Child | 12 (75.0) | ||

| Other (Nephew) | 1 (6.25) | ||

| CG Time bereaved (months) | 9.6 (6.9) | ||

| CG Present at time of death | Yes | 7 (43.75) | |

| Location of death | LTC | 11 (68.75) | |

| Hospital | 4 (25.0) | ||

| Home | 1 (6.25) | ||

| CG Ethnic Background | British | 10 (62.5) | |

| European | 3 (18.75) | ||

| Asian | 2 (12.5) | ||

| South Asian | 1 (6.25) | ||

| CG Religion | Agnostic | 4 (25.0) | |

| Christian (any denomination) | 9 (56.25) | ||

| Jewish | 2 (12.5) | ||

| Hindu | 1 (6.25) | ||

| CG Employment Status | Retired | 5 (31.25) | |

| Full-time | 8 (50.0) | ||

| Part-time | 2 (12.5) | ||

| Currently not working | 1 (6.25) | ||

| CG Education | Less than High School | 1 (6.25) | |

| High School | 1 (6.25) | ||

| College / University | 8 (50.0) | ||

| Graduate School | 6 (37.5) | ||

| CG Household Annual Income | 51-100,000 | 6 (37.5) | |

| $101-150,000 | 3 (18.75) | ||

| $151-200,000 | 3 (18.75) | ||

| Greater than $200,000 | 4 (25.0) | ||

| CR Gender | Male | 8 (50.0) | |

| Female | 8 (50.0) | ||

| CR Age (years) | 85.9 (6.4) | ||

| CR Time in LTC (years) | 2.9 (1.8) | ||

| CR Time with dementia (years) | 9.4 (6.0) | ||

| Type of dementia | Alzheimer’s | 6 (37.5) | |

| Vascular | 3 (18.75) | ||

| Korsakoff | 1 (6.25) | ||

| Unknown | 6 (37.5) | ||

| CR Ethnic background | British | 10 (62.5) | |

| European | 2 (12.5) | ||

| South Asian | 1 (6.25) | ||

| East Asian | 2 (12.5) | ||

| Nordic | 1 (6.25) | ||

| CR Religion | Agnostic | 2 (12.5) | |

| Christian (any denomination) | 11 (68.75) | ||

| Jewish | 1 (6.25) | ||

| Hindu | 1 (6.25) | ||

| Muslim | 1 (6.25) | ||

| CR Education | Less than high school | 2 (12.5) | |

| High school | 5 (31.25) | ||

| University / college | 5 (31.25) | ||

| Graduate school / professional certificate | 3 (18.75) | ||

| Trade school | 1 (6.25) |

Note. CG = caregiver; CR = care recipient (i.e., person with dementia); LTC = long-term care.

Figure 2.

Core Concepts of Preparedness Developed in the Context of the Caregiving Journey.

Theme 1. “A crazy rollercoaster at the end”: The challenging journey of caregiving and preparing for EOL. This theme describes participants’ experience of caring for their family member as a dynamic, process of emotional upheaval, responses to decline and created context for the development of preparedness. Specifically, the rate (sudden or gradual), nature of decline (expected or unexpected) and quality-of-life of the PWD are contextual factors along the journey that influence the core concepts of preparedness.

Participants described experiencing, “one crisis after another, after another…with so many ups and downs for years” (P01) and a “crazy rollercoaster at the end…we weren’t prepared for” (P12). A pattern of medical events characterized the last year of the PWD’s life, including the loss of “vocal capabilities…ability to focus… swallowing… recognizing family” (P15). Participants described PWD as having “a long, slow deterioration in overall health and quality-of-life” (P04). However, the final months/days of life were often described as rapid or sudden. A participant explained, “We had lots of time…years even, but no time…when it mattered” (P16).

During the last year of life, PWD were perceived as, “already gone” (P15) and “ready to die” (P07). Participants expressed that PWD had poor quality-of-life and the participants were therefore “ready” (P06) or “waiting for it to be over” (P05). Thus, the quality-of-life for the PWD appeared to influence feelings of preparedness for death. A predictable trajectory and nature decline (expected by the participant) as well as a slower rate of decline were also viewed as motivating and promoting preparedness. A participant explained, “I had some time because there was some lead-up right? They said, ‘she’s got [pneumonia]’ and she slowly slipped away…that’s a great gift” (P06). In contrast, rapid and unexpected decline presented barriers to preparedness. A participant explained, “He went from completely functional to hell in 45 days…I wasn’t prepared for that rate of decline” (P16). Overall, the journey of caregiving for someone with dementia during EOL was described as a roller coaster and preparedness was influenced by contextual factors such as the quality-of-life of the PWD, the rate and nature of decline.

Theme 2. “A sense of control”: Managing the situation. A core concept comprising preparedness was managing the situation which focused on meeting the needs of the PWD. Managing the situation meant feeling competent in the caregiver role and confident in goals for the PWD, and was facilitated by being proactive, knowledgeable about dementia and resourceful. Some participants described themselves as, “…checking all the boxes” (P16) and “…staying on top of things” (P15). Strategies such as organizing and planning, advocating and articulating goals, information and resource-seeking assisted participants to maintain a sense of control and meet the needs of the PWD. A participant explained, “I felt in control…I did exactly what I wanted to do every step of the way…If they say someone is dying, don’t just sit there! Make plans (P06). Another participant explained, “We worked hard to educate ourselves…Our intent was always to make sure that we were able to give him all the supports that he needed…” (P11).

Having transparent, collaborative relationships and confidence in healthcare providers and other family members to meet the PWD’s needs also enabled participants to manage the situation. A participant shared, “the charge nurse had her finger on everything…I knew they would keep him comfortable” (P14). Communication from healthcare providers assisted participants to understand the PWD’s health status, which promoted a sense of control. A participant explained, “I called a physician friend …he was the one who said, ‘it sounds like he’s palliative’…and it was just reassuring to hear that…” (P02). In contrast, inadequate care, a lack of continuity and limited communication with staff were perceived as barriers to preparedness.

Information-seeking and communicating with staff were important for participants to understand the potential nature for decline and trajectory of changes associated with dementia described as influencing preparedness in the caregiving journey (Theme 1).

Theme 3. “Doing right”: Fulfilling obligations. A core concept of preparedness was fulfilling perceived moral and legal obligations that are the result of societal needs and expectations for EOL. Obligations were perceived “duties” (P01) to fulfill before, during and after death. Meeting moral obligations to society meant supporting quality-of-life, dignity, comfort and companionship while dying and traditional/customary celebrations of life and legacy at EOL (e.g., cultural, spiritual, personal). Alternatively, legal obligations to society meant completing worldly, practical and financial affairs at EOL. Participants perceived that fulfilling obligations was necessary to avoid regrets and emotional distress. A participant explained, “I don’t think you can ever fully prepare…But I would say no regrets is the most important thing…” (P06). The fulfillment of obligations was facilitated by understanding the PWD’s wishes related to traditions/customs and legal affairs, and making arrangements before death.

A participant summarized moral obligations to be fulfilled:

You want to bring that person as many experiences, connections and enforcement or recognition of their contribution to the lives of family members and their friends. To give them self-esteem, to give them comfort they’ve made the most of their lives (P03).

Another participant explained how they had fulfilled the need for a traditional ceremony for EOL, “I arranged…a prayer service…You felt like you had done right by her you know” (P15). Participants explained that (similar to managing the situation) fulfilling moral obligations was facilitated by planning, making arrangements and information-seeking about societal traditions at EOL:

In the Jewish tradition…There are laws that are supposed to be followed when it comes to any rite of passage… It almost becomes like an exercise that you’ve done before (P09).

For some participants fulfilling legal obligations, such as completing financial and government affairs was a relatively smooth process. A participant explained, “By the time [my husband] passed everything was in place…Everyone should have a will” (P02). For other participants fulfilling legal obligations and “all the different things that we had to tie up…was a steep learning curve” (P13) and “a nightmare” (P15). Participants perceived that consolidating and joining bank accounts, having a will, designating surrogate decision-making power, and learning about their family member’s estate in advance of death facilitated the fulfillment of legal obligations. A sudden or rapid rate of decline (as described in Theme 1) for the PWD during the caregiving journey therefore made it more difficult to fulfill obligations.

In this study, obligations and the fulfillment of duties were influenced by the relationship of the participant (i.e., spouse vs. adult child), gender and culture. Spouse participants interviewed described having less difficulty fulfilling obligations than adult child participants, and therefore relationships may have created a barrier. Discussions about health and EOL for example were sometimes described as, “private…between your Dad and I” (P16), meaning that they were reserved for spouse relationships. Participants of minority ethnic origins (n = 3) also emphasized that gender and culture influenced how their societal obligations were defined, and how they were fulfilled. A participant of Chinese origin stated for example, “Traditionally…My Dad didn’t tell my Mom what was going on with the money…All of a sudden he’s not there anymore and we had to dig up stuff” (P13). A participant of South Asian ethnic origin also explained, “In my country girls are sometimes lower class… My brother got Power of Attorney, and staff had to call him for permission for everything, even though I was there” (P10). In summary, fulfilling obligations focused on meeting societal obligations and duties during EOL that were influenced by culture, gender and relationships.

Theme 4. “Coming to terms”: Adapting to loss. This theme focused on the caregiver themselves, and their constant need to adapt to decline, loss and changing identity. Accepting what could not be changed (including personal limitations), finding meaning, reframing the situation to focus on positive aspects, and coping with emotions were perceived as facilitating ‘coming to terms’. A participant described accepting change and loss stating, “I think you sort of got used to the idea over a period of time. I mean you knew he was going to die, you just didn’t know quite when” (P07) and “There’s no quality of life really, I didn’t want him to live that way” (P15). A predictable trajectory/expected nature of decline, as well as perceptions of limited quality-of-life within the caregiving journey therefore promoted participants adaptation to loss. Feelings of existential distress contrasted those of acceptance and were often associated with perceptions that obligations were not fulfilled and the needs of the PWD were not met. A participant stated, “I have to forgive myself…I tell myself I did my best…But he didn’t deserve that…it was just not fair” (P16).

Strategies of reframing or “making the best of the situation” (P06), focusing on positive aspects and “being thankful” (P08) were perceived as facilitating acceptance, adaptation and reconciliation with change and loss. Participants described positive aspects of their experiences such as, “a new closeness…where we had been emotionally distant before” (P01), “intimacy” (P02), and “a new softness in his personality” (P16). Similarly, reflecting on personal growth and searching for meaning amidst challenges were described as important. A participant shared, “There was a greater purpose in this because we’ve been able to help out other people…it's part of the healing” (P11). Practicing self-care, setting priorities, seeking emotional support, and coping with emotions or, “going into the feeling” (P02) also facilitated ‘coming to terms’. A participant described prioritizing her family stating, “It was like we were standing in the middle of a hurricane. So, we really worked hard to focus on our own little family just to support and love on each other” (P11).

Participants perceived that during EOL and bereavement, caregivers were adapting to a new identity and were therefore, “…in transition” (P02). Adult children perceived they were an “orphan now” (P07), “the head of my family” (P16) and the “next generation to go” (P09). In contrast, spouse caregivers spoke more often about losing their purpose. A spouse participant explained, “You wake up in the morning and you don’t have a purpose…the little birds have left the nest, the wife is gone…That’s what you’re on earth for right?” (P02). Participants perceived that caregivers should, “…keep their friends” (P01) and “…sustain their hobbies, anything that gives them purpose” (P07) in order to adapt and prepare.

Adapting to loss was also facilitated by resolving conflicts, reconciling with the PWD, and finding peace within oneself. Participants perceived that, “saying what you need to say” (P05), “letting go” (P11) and “writing in a journal” (P07) were beneficial. A meaningful reconciliation between the PWD and another family member was described by a participant who shared, “Even though he was non-responsive they were able to reconcile…there’s all kinds of stuff if you’re brave enough to go after it” (P16). Similarly, other participants explained, “I learned that lesson with my mother, to make sure I said the things that were on my mind before she left me…to get it off my chest” (P09) and “I have peace” (P10). In particular, participants expressed a need to accept personal limitations related to unmet needs and unfulfilled obligations to the PWD. Coming to terms was therefore closely linked to the perceived development of core concepts in Theme 2 and Theme 3.

Discussion

Four themes emerged in this study. The first theme, ‘A crazy roller coaster at the end’ described the journey of caregivers of PWD and factors (rate, nature of decline and quality-of-life) perceived as influencing feelings of preparedness for death. The description of this journey provided context for the development of three core concepts of preparedness for death: managing the situation, which focused on the PWD; fulfilling obligations, which focused on society; and adapting to loss, which focused on the caregiver themselves. The study findings are particularly relevant to healthcare professionals (e.g., nurses and healthcare providers) supporting PWD and caregivers in the long-term care. The findings serve to: 1) further conceptualize preparedness for death; and 2) highlight facilitators and barriers that can guide practice. Altogether these findings will provide the conceptual basis for a preparedness questionnaire.

In general, the study findings support the validity of the pre-existing theoretical knowledge of preparedness (Hebert et al., 2006a; Durepos et al., 2018). Preparedness was previously defined as, “a self-perceived cognitive, affective and behavioural quality or state of readiness to maintain self-efficacy and control in the face of loss” (Durepos et al., 2018). In addition to highlighting ‘A sense of control’ as a core concept of preparedness however, the findings from the study suggest that the core concepts ‘Coming to terms’ and ‘Doing right’ are equally important. Previously ‘adaptation’ was also previously perceived as a consequence whereas in this study adapting emerged as a core concept. Caregiving is theorized as a process of adaptation, referred to as ‘seeking normal’ and ‘coming to terms’ in a grounded theory exploring caregiver experiences at EOL (Duggleby et al., 2017; Penrod et al., 2012). Therefore, the theoretical definition of preparedness may need to be amended to include all three core concepts. A new definition could state, ‘caregiver preparedness for death in dementia is a self-perceived cognitive, affective and behavioural quality or state of readiness to manage the situation, fulfill obligations and adapt to loss’.

The core concepts identified also provide new insight into the meaning of, and relationships between preparedness attributes. Perceived attributes of preparedness such as ‘knowing and recognizing signs of decline and dementia’ are currently organized into medical, psychosocial, practical and spiritual domains in the existing model (Durepos et al., 2018). However, the attributes could be re-grouped according to the core concepts which may be more meaningful that organizing attributes by domain. For example, participants described the attributes ‘Accepting that losses are inevitable and imminent’; ‘Reflecting on caregiving and finding meaning; Understanding emotions and grief; and ‘Reconciling, renewing and closing a relationship’ as facilitators for ‘Coming to terms’ in this study. Re-grouping and revising the attributes in light of the core concepts which are written in lay language, may make the concept of preparedness more accessible and concrete for healthcare providers to discuss and promote in practice (Litzelman et al., 2017).

Perceived facilitators of preparedness in this study can be promoted in practice by healthcare providers and can be translated into questionnaire items aimed at measuring preparedness. Facilitators include for example: making arrangements in advance to fulfill obligations, articulating goals for EOL, maintaining a social network and sources of purpose other than caregiving, having transparent collaborative relationships with care providers, seeking out supportive resources and ‘back-up’, practicing self-care and coping with emotions. It is promising that strategies supporting a palliative approach (e.g., Goals of Care conversations) are increasingly being implemented in long-term care that incorporate preparedness facilitators identified in this study (Kaasalainen & Sussman, 2019). However, further research evaluating the impact of interventions on caregiver death preparedness as an outcome is needed to assess intervention effectiveness/quality.

Facilitators/barriers to preparedness identified here also correspond with unmet needs of caregivers reported in long-term, such as poor communication with healthcare providers, a lack of psychosocial support, and limited access to resources (De Cola et al., 2017; Whitlatch & Orsulic-Jeras, 2018). End-of-life discussions with healthcare providers in particular are lacking and occur with only 22% of caregivers in long-term care, which likely impedes preparedness (Morin et al., 2016). Having unresolved conflicts with the person who is dying (i.e., unfinished business) and a perceived inability to provide comfort, are also linked to poor caregiver outcomes and distress in bereavement (Holland et al., 2020); highlighting the need for strategies such as reconciling, promoting comfort and personhood described as facilitators of preparedness in this study.

Strengths and Limitations

Study strengths include strategies to enhance trustworthiness of the findings such as: 1) journaling and debriefing for reflexivity and conformability; 2) researcher triangulation; 3) maintenance of an audit trail for dependability and 3) maximum variation sampling for transferability. Thick-description of the methods and findings was provided to support and transferability, transparency and dependability (Elo et al., 2014; Thorne, 2016). Spouse caregivers, persons with lower socioeconomic status and education, and persons from minority cultures were recruited with a wide range of experiences. However, the high proportion of adult-child caregivers and few persons representing minorities limits the inferences that can be made about subgroups in the study. A population-based, representative sampling strategy was not used and therefore the findings may only be applicable to participants in the study (Patton, 2015). In addition, data regarding the participants’ number of hours caregiving was not collected that may have influenced EOL experiences. Lastly, data were collected retrospectively and were of an extremely sensitive nature. Participants may have experienced recall bias and/or selectively shared data that influenced the study findings (Patton, 2015).

Implications for Practice

Healthcare providers (including nurses and allied health) are promoting a palliative approach to improve EOL experiences and outcomes for PWD and their caregivers. However, strategies often remain focused on medical (e.g., pain and symptom management) or practical aspects of death (e.g., documentation of resuscitation status), and professionals often avoid discussing emotional aspects of death (e.g., grief, traditions, spiritual beliefs) (Brazil et al., 2012; McMahan et al., 2013). Based this study, it is clear that both practical and emotional support are needed by caregivers to promote feelings of preparedness. Spiritual and psychosocial care are requisite palliative care competencies for nurses and other healthcare providers in most countries (Ontario Palliative Care Network, 2019). Therefore, providers require additional training to support caregivers in existential distress, to practice active listening, psychotherapy, coaching persons in self-care and goal-setting (Kulasegaram et al., 2018). Providers should focus on being transparent, collaborative, sharing information about dementia and ‘what to expect’, keeping caregivers informed about health changes and helping caregivers understand the meaning of the changes to promote feelings of preparedness for death.

Conclusion

Overall, this study fulfilled the objectives to explore the EOL experiences of caregivers and produce a coherent conceptual description of preparedness that is relevant to clinical practice. Four themes were interpreted describing the caregiving journey and factors influencing preparedness, and three core concepts comprising preparedness: managing the situation, fulfilling obligations and adapting to loss. The situations and losses experienced by caregivers as they prepared for EOL (Theme 1) provided insight into the information-needs of caregivers that healthcare providers should anticipate and address (e.g., surrounding dementia trajectory). The core concepts of preparedness focused on meeting the needs of the PWD, society and the caregiver. Behaviours (e.g., organizing, arranging, communicating) described as facilitating core concepts of preparedness should also be promoted in healthcare providers’ practice, and included on the Caring Ahead: Preparing for EOL with Dementia questionnaire.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-son-10.1177_2377960820949111 for “A Crazy Roller Coaster at the End”: A Qualitative Study of Death Preparedness With Caregivers of Persons With Dementia by Pamela RN, PhD Jenny PhD Tamara Sussman PhD Noori Akhtar-Danesh PhD Sharon Kaasalainen RN, PhD in SAGE Open Nursing

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant 159269; the Canadian Frailty Network Interdisciplinary Fellowship IFP 2018-03 (funded through National Centers of Excellence); an operating grant from the Alzheimer Society of Brant, Haldimand-Norfolk, Hamilton-Halton Branch; the Canadian Nurses Foundation, Registered Nurses Foundation of Ontario (Mental Health Interest Group) and Shalom Village Long-Term Care Home. The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

ORCID iDs

Pamela Durepos https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8828-8314

Jenny Ploeg https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8168-8449

References

- Barry L. C., Kasl S. V., Prigerson H. G. (2002). Psychiatric disorders among bereaved persons: The role of perceived circumstances of death and preparedness for death. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 10(4), 447–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayda W., Boyce T. (2014). So you really want to interview me? Navigating “sensitive” qualitative research interviewing. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 13(1), 318–334. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V., Rance N. (2014). How to use thematic analysis with interview data (process research) In Vossler A., Moller N. (Eds.), The counselling and psychotherapy research handbook (pp. 183–197). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Brazil K., Kaasalainen S., McAiney C., Brink P., Kelly M. L. (2012). Knowledge and perceived competence among nurses caring for the dying in long-term care homes. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 18(2), 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremer P., Cabrera E., Leino-Kilpi H., Lethin C., Saks K., Sutcliffe C., Soto M., Zwakhalen S. M. G., Wübker A., & RightTimePlaceCare Consortium. (2015). Informal dementia care: Consequences for caregivers’ health and health care use in 8 European countries. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 119(11), 1459–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caserta M., Utz R., Lund D., Supiano K., Donaldson G. (2019). Cancer caregivers’ preparedness for loss and bereavement outcomes: Do preloss caregiver attributes matter? Omega – Journal of Death and Dying, 80(2), 224–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Requena G., Val M. E., Cristòfol R. (2015). Caregiver burden in end-of-life care: Advanced cancer and final stage of dementia. Palliative & Supportive Care, 13(3), 583–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J., Klassen A., Plano Clark V., Smith K. (2011). Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. National Institutes of Health, 541–545. [Google Scholar]

- Cupchik G. (2001). Constructive realism: An ontology that encompasses positivist and constructivist approaches to the social sciences. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- De Cola M. C., Lo Buono V., Mento A., Foti M., Marino S., Bramanti P., Manuli A., Calabrò R. S. (2017). Unmet needs for family caregivers of elderly people with dementia living in Italy: What do we know so far and what should we do next. Inquiry: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, 54 10.1177/0046958017713708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggleby W., Tycholiz J., Holtslander L., Hudson P., Nekolaichuk C., Mirhosseini M., Parmar J., Chambers T., Alook A., Swindle J. (2017). A metasynthesis study of family caregivers’ transition experiences caring for community-dwelling persons with advanced cancer at the end of life. Palliative Medicine, 31(7), 602–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durepos, P., Sussman, T., Ploeg, J., Akhtar-Danesh, N., Punia, H., & Kaasalainen, S. (2018). What does death preparedness mean for family caregivers in dementia? American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 36(5), 436–446. 10.1177/1049909118814240. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Durepos, P., Ploeg, J., Akhtar-Danesh, N., Sussman, T., Orr, E., & Kaasalainen, S. (2019). Caregiver preparedness for death in dementia: An evaluation of existing tools. Aging and Mental Health https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13607863.2019.1622074 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Elo S., Kääriäinen M., Kanste O., Pölkki T., Utriainen K., Kyngäs H. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open, 4(1). 10.1177/2158244014522633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harding R., Gao W., Jackson D., Pearson C., Murray J., Higginson I. J. (2015). Comparative analysis of informal caregiver burden in advanced cancer, dementia, and acquired brain injury. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 50(4), 445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert R., Dang Q., Schulz R. (2006. a). Preparedness for the death of a loved one and mental health in bereaved caregivers of patients with dementia: Findings from the REACH study. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 9(3), 683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert R., Prigerson H., Schulz R., Arnold R. (2006. b). Preparing caregivers for the death of a loved one: A theoretical framework and suggestions for future research. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 9(5), 1164–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland J. M., Plant C. P., Klingspon K. L., Neimeyer R. A. (2020). Bereavement-related regrets and unfinished business with the deceased. Death Studies, 44(1), 42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaasalainen S., Sussman T. (2019). Evaluating the strengthening a palliative approach in Long-Term care (SPA-LTC) program in Canada. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 20(3), B17. [Google Scholar]

- Karg N., Graessel E., Randzio O., Pendergrass A. (2018). Dementia as a predictor of care- related quality of life in informal caregivers: A cross-sectional study to investigate differences in health-related outcomes between dementia and non-dementia caregivers. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersting A., Brähler E., Glaesmer H., Wagner B. (2011). Prevalence of complicated grief in a representative population-based sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 131(1-3), 339–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulasegaram P., Thompson G., Sussman T., Kaasalainen S. (2018). End-of-Life care communication training programs for Long-Term care staff: A scoping review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 56(6), e80. [Google Scholar]

- Litzelman D. K., Inui T. S., Schmitt-Wendholt K. M., Perkins A., Griffin W. J., Cottingham A. H., Ivy S S. (2017). Clarifying values and preferences for care near the end of life: The role of a new lay workforce. Journal of Community Health, 42(5), 926–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahan R., Knight S., Fried T., Sudore R. (2013). Advance care planning beyond advance directives: Perspectives from patients and surrogates. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 46(3), 355–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell S. L., Teno J. M., Kiely D. K., Shaffer M. L., Jones R. N., Prigerson H. G., Volicer L., Givens J. L., Hamel M. B. (2009). The clinical course of advanced dementia. The New England Journal of Medicine, 361(16), 1529–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin L., Johnell K., Van den Block L., Aubry R. (2016). Discussing end-of-life issues in nursing homes: A nationwide study in France. Age and Ageing, 45(3), 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M. K., Neergaard M. A., Jensen A. B., Bro F., Guldin M. B. (2016). Do we need to change our understanding of anticipatory grief in caregivers? A systematic review of caregiver studies during end-of-life caregiving and bereavement. Clinical Psychology Review, 44, 75–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Palliative Care Network. (2019). Ontario palliative care competency framework https://www.ontariopalliativecarenetwork.ca/en/competencyframework

- Patton M. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Penrod J., Hupcey J., Shipley P., Loeb S., Baney B. (2012). A model of caregiving through the end of life: Seeking normal. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 34(2), 174–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn C., Toms G. (2018). Influence of positive aspects of dementia caregiving on caregivers’ well-being: A systematic review. The Gerontologist, 59(5), e584–e596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A., McGilloway S. (2011). Methodological and ethical aspects in evaluation research in bereavement. Bereavement Care, 30(1), 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Romero M. M., Ott C. H., Kelber S. T. (2014). Predictors of grief in bereaved family caregivers of person's with Alzheimer's disease: A prospective study. Death Studies, 38(6-10), 395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R., Boerner K., Klinger J., Rosen J. (2015). Preparedness for death and adjustment to bereavement among caregivers of recently placed nursing home residents. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 18(2), 127–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzakis K. (2019). Preparing family members for the death of a loved one in long-term care. Annals of Long-Term Care, 27(2), 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. (2016). Interpretive description: Qualitative research for applied practice (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Steen J. T., Onwuteaka-Philipsen B. D., Knol D. L., Ribbe M. W., Deliens L. (2013). Caregivers’ understanding of dementia predicts patients’ comfort at death: A prospective observational study. BMC Medicine, 11, 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Steen J. T., Radbruch L., Hertogh C. M. P. M., de Boer M. E., Hughes J. C., Larkin P., Francke A. L., Jünger S., Gove D., Firth P., Koopmans R. T. C. M., Volicer L., & European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC). (2014). White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: A Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for palliative care. Palliative Medicine, 28(3), 197–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson B., Tatangelo G., McCabe M. (2018). Depression and anxiety among partner and offspring carers of people with dementia: A systematic review. The Gerontologist, 59(5), e597–e610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch C. J., Orsulic-Jeras S. (2018). Meeting the informational, educational and psychosocial support needs of persons living with dementia and their family caregivers. The Gerontologist, 58(suppl_1), S58–S73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2019). Dementia key facts. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-son-10.1177_2377960820949111 for “A Crazy Roller Coaster at the End”: A Qualitative Study of Death Preparedness With Caregivers of Persons With Dementia by Pamela RN, PhD Jenny PhD Tamara Sussman PhD Noori Akhtar-Danesh PhD Sharon Kaasalainen RN, PhD in SAGE Open Nursing