Abstract

We report a superspreading event of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection initiated at a bar in Vietnam with evidence of symptomatic and asymptomatic transmission, based on ministry of health reports, patient interviews, and whole-genome sequence analysis. Crowds in enclosed indoor settings with poor ventilation may be considered at high risk for transmission.

Key words: COVID-19, disease cluster, pandemic, reverse transcription PCR, SARS-CoV-2, superspreading, Vietnam, viruses, whole-genome sequencing, respiratory infections, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, coronavirus disease

Superspreading events occur when a few persons infect a larger number of secondary persons with whom they have contact (1,2). For severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), an R0 of 2–3 with 6–8 secondary cases has been suggested to constitute a superspreading event (3).

Although SARS-CoV-2 is known to be transmitted through droplets and fomites, there has been growing evidence of airborne transmission (4,5). Better understanding of specific settings in which superspreading events are facilitated remains critical to inform the development and implementation of control measures to avoid future waves of the pandemic (5).

On March 18, 2020, a 43-year old man, patient 1, sought treatment at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, for fever, cough, muscle aches, fatigue, and headache. A sample from a nasopharyngeal throat swab specimen taken at admission tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by reverse transcription PCR.

During the 14 days before the onset of his symptoms on March 17, he had traveled to Thailand and within Vietnam, between Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. From 10:00 PM on March 14 until 2:30 AM of the next day, he participated in a St. Patrick’s Day celebration at bar X in Ho Chi Minh City. The bar had 2 indoor areas for clients, an »300-m2 area downstairs and an »50-m2 area upstairs, with no mechanical ventilation. During open hours, the left and right entrances were typically kept closed to facilitate cooling with air conditioners that recycle indoor air; the middle entrance was kept open. The bar also has naturally ventilated outdoor spaces (Appendix). Patient 1 was inside the bar during the party.

After the confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 in patient 1, we used contact tracing and testing to detect 18 additional PCR-confirmed cases. Of these, 12 (patients 2–13) were at bar X during the evening of March 14; the other 6 (patients 14–19) were contacts (Table; Appendix Figure). Of the patients with confirmed cases attending the celebration, 4 were in close contact with patient 1: patients 2–4 went to the celebration with patient 1 and patient 6 worked as a waiter in the bar. Patients 2 and 3, who were roommates, had traveled to Malaysia and returned to Vietnam, patient 2 on March 13 and patient 3 on March 6. The other patients, except for patient 1, had no recent history of travel outside of HCMC (Table).

Table. History of travel and patients and contacts of patients positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in cluster associated with bar, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 2020*.

| Patient no. |

Contact history and epidemiologic factors |

Inside bar? |

Travel history† |

Occupation |

Symptom onset |

Diagnosed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients present at bar X for celebration on March 14–15, 2020 | ||||||

| 1 | Attended with patients 2, 3, and 4 | Y | Y | Pilot | 03/17 | Mar 18 |

| 2 | Attended with patients 1, 3, and 4; roommate of patient 3 | UNK | Y | Teacher | Unavail.‡ | Mar 22 |

| 3 | Attended with patients 1, 2, and 4; roommate of patient 2 | UNK | Y | Teacher | Unavail. | Mar 22 |

| 4 | Attended with patients 1, 2, and 3 | UNK | N | Teacher | Mar 21 | Mar 22 |

| 5 | Attendee; works at shoe company Y | UNK | N | Unavail. | Asympt. | Mar 23 |

| 6 | Waiter at bar X; in close contact with patient 1 | Y | N | Bar X waiter | Mar 16 | Mar 23 |

| 7 | Attendee | UNK | N | Unavail. | Unavail. | Mar 24 |

| 8 | Attendee; friend of patient 7 | UNK | N | Teacher | Unavail. | Mar 24 |

| 9 | Attendee | UNK | N | Teacher | Mar 25 | Mar 26 |

| 10 | Attendee | UNK | N | Technician | Asympt. | Mar 26 |

| 11 | Attended with patient 5 | UNK | N | Unavail. | Unavail. | Mar 28 |

| 12 | Attendee | UNK | N | Unavail. | Asympt. | 04/02 |

| 13 |

Attended with patient 12 |

UNK |

N |

Unavail. |

Mar 26 |

04/03 |

| Contacts of patients present at bar X for celebration on March 14–15, 2020 | ||||||

| 14 | Contact of patients 5 and 19 as coworkers at shoe company Y | NA | N | Unavail. | Asympt. | Mar 25 |

| 15 | Household contact of patient 10 | NA | N | Unavail. | Asympt. | Apr 1 |

| 16 | Household contact of patient 6 | NA | N | Unavail. | Unavail. | Mar 27 |

| 17 | Contact (driver) of patients 5 and 14 | NA | N | Driver | Mar 27 | Mar 30 |

| 18 | Household contact of patient 14; also contact of patient 5 as a coworker at shoe company Y | NA | N | Unavail. | Asympt. | Mar 30 |

| 19 | Contact of patients 5 and 14 as coworkers at shoe company Y | NA | N | Unavail. | Unavail. | Apr 6 |

*Asympt., asymptomatic; NA, Not applicable; unavail., unavailable; UNK, unknown. †Traveled to an area with known local transmission in previous 14 d. ‡Because patient did not enroll in the clinical study, but asymptomatic at time of diagnosis.

Figure.

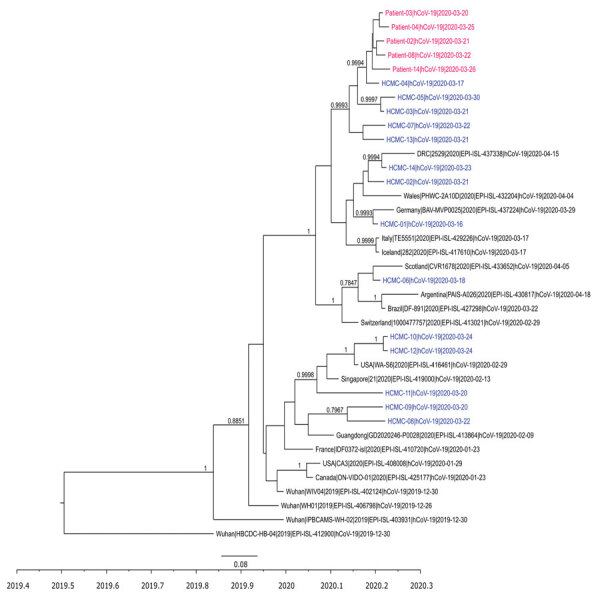

Time-scale phylogenetic tree illustrating the relatedness between whole-genome sequences of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 obtained from patients with confirmed cases of the cluster associated with a bar in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 2020, and reference sequences. Sequences from the cluster patients are in red; sequences from coronavirus disease patients in Ho Chi Minh City, not related to the cluster, are in blue. For those sequences, we obtained 21 genomes from the remaining 35 patients reported in Ho Chi Minh City as of April 24, 2020, for the purpose of the analysis; subsequently, we used 14 nonidentical sequences for the analysis. Representative sequences from patients not in Vietnam are in black. Posterior probabilities ≥75% are indicated at all nodes. The analysis was carried out using BEAST version 1.8.3 (https://beast.community). For time-scale analysis, only 1 representative of sequences that were 100% identical to each other was included. Whole-genome sequences were generated using ARTIC primers version 3 (ARTIC Network, https://artic.network/ncov-2019).

By exploring the epidemiologic links discovered from in-depth interviews, we identified 3 possible transmission chains involving patients who attended the March 14 celebration (Table; Figure; Appendix Figure). Of these, 2 or 3 patients (patients 5, 10, and possibly 14) were asymptomatic but transmitted SARS-CoV-2 to their contacts (Table; Figure). None of the 19 patients with confirmed cases reported that they had respiratory signs or symptoms on March 14–15. However, in addition to patient 1, a total of 5 others developed mild respiratory symptoms (patient 4 on March 16, patient 6 on March 21, patient 9 on March 25, patient 13 on March 26, and patient 17 on March 27), suggesting an incubation period of 2–12 days. Follow-up data were available for 12 patients who participated in our clinical study (Appendix). Six remained asymptomatic during follow-up (Appendix Table 1).

A total of 11 whole-genome sequences of SARS-CoV-2 were obtained from the patients in the cluster. The obtained sequences were either 100% identical or different from each other by only 1–2 nt (Appendix Table 2). Phylogenetically, they clustered together tightly but were different from sequences obtained from other cases in Ho Chi Minh City during the same period.

As of September 15, 2020, only 30 cases of locally acquired infection had been reported in Ho Chi Minh City (6), but this cluster represents the only documented superspreading event (6,7). Together with data from previous reports (3,8,9), these data suggest that closed settings are facilitators of community transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The mechanism by which infected people without symptoms spread SARS-CoV-2 to others, especially in closed settings, warrants further research, including on transmission through aerosols, which has been suggested (4,10).

The high level of genome sequence similarity between the SARS-CoV-2 genomes obtained from the patients and the tight clustering on the phylogenetic tree strengthen the epidemiologic link between the PCR-confirmed cases from this cluster. Together with contact history, these data also support transmission chains involving asymptomatic carriers (patients 5 and 14) as the sources of the ongoing infection. However, the identity of the patient in the index case from the bar could not be confirmed, in part because in-depth interview data were available from only 8 of 13 patients with confirmed cases who consented to participate in the study. In conclusion, our results emphasize that persons in crowded indoor settings with poor ventilation may be considered to be at high risk for SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Appendix. Additional information about the COVID-19 outbreak and response.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Nguyen Thanh Ngoc, Le Kim Thanh, and the OUCRU IT/CTU/Lab management departments, especially Ho Van Hien, Dang Minh Hoang, and Nguyen Than Ha Quyen, for their support. We thank Maia Rabaa at OUCRU for her initial discussion about the analysis, and Leigh Jones at OUCRU for her input with some of the epidemiological data. Finally, we thank the patients for their participation in this study and the doctors and nurses of the Hospital for Tropical Diseases, who cared for the patients and provided the logistic support with the study.

This study was funded by the Wellcome Trust of Great Britain (106680/B/14/Z and 204904/Z/16/Z).

Biography

Dr. Chau is the director of the Hospital for Tropical Diseases in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. He is a frontline healthcare worker in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Chau NVV, Hong NTT, Ngoc NM, Thanh TT, Khanh PNQ, Nguyet LA, et al. Superspreading event of SARS-CoV-2 infection at a bar, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021 Jan [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2701.203480

Members of the group are listed in the Appendix.

References

- 1.Wang SX, Li YM, Sun BC, Zhang SW, Zhao WH, Wei MT, et al. The SARS outbreak in a general hospital in Tianjin, China — the case of super-spreader. Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134:786–91. 10.1017/S095026880500556X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho SY, Kang J-M, Ha YE, Park GE, Lee JY, Ko J-H, et al. MERS-CoV outbreak following a single patient exposure in an emergency room in South Korea: an epidemiological outbreak study. Lancet. 2016;388:994–1001. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30623-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adam DC, Wu P, Wong JY, Lau EHY, Tsang TK, Cauchemez S, et al. Clustering and superspreading potential of SARS-CoV-2 infections in Hong Kong. Nat Med. 2020; Epub ahead of print. 10.1038/s41591-020-1092-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morawska L, Milton DK. It is time to address airborne transmission of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa939. 10.1093/cid/ciaa939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: implications for infection prevention precautions. 2020. [cited on 2020 Jul 24] https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/transmission-of-sars-cov-2-implications-for-infection-prevention-precautions

- 6.Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Updated information about COVID-19 pandemic. Official page on acute respiratory infections COVID-19 [cited 2020 Sep 5].http://http://ncov.moh.gov.vn

- 7.Thanh HN, Van TN, Thu HNT, Van BN, Thanh BD, Thu HPT, et al. Outbreak investigation for COVID-19 in northern Vietnam. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:535–6. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30159-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pung R, Chiew CJ, Young BE, Chin S, Chen MIC, Clapham HE, et al. ; Singapore 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak Research Team. Investigation of three clusters of COVID-19 in Singapore: implications for surveillance and response measures. Lancet. 2020;395:1039–46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30528-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghinai I, Woods S, Ritger KA, McPherson TD, Black SR, Sparrow L, et al. Community Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 at Two Family Gatherings - Chicago, Illinois, February-March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:446–50. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Somsen GA, van Rijn C, Kooij S, Bem RA, Bonn D. Small droplet aerosols in poorly ventilated spaces and SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:658–9. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30245-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix. Additional information about the COVID-19 outbreak and response.