Abstract

A nationwide outbreak of human listeriosis in Switzerland was traced to persisting environmental contamination of a cheese dairy with Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b, sequence type 6, cluster type 7488. Whole-genome sequencing was used to match clinical isolates to a cheese sample and to samples from numerous sites within the production environment.

Keywords: outbreak, listeriosis, Listeria monocytogenes, bacteria, serotype 4b, sequence type 6, ST6, hypervirulent emerging clone, cheese, cheese production environment, contamination, persistence, food safety

Listeriosis is a potentially lethal infection, and the elderly population, pregnant women, and immunocompromised persons at particular risk (1). Foods, in particular ready-to-eat foodstuffs, including meat, fish, dairy products, fruits, and vegetables, represent the major vehicle for sporadic cases and outbreaks of listeriosis (2). Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b sequence type 6 (ST6) has emerged since 1990 as a hypervirulent clone that is associated with particularly worse outcome for case-patients who have Listeria meningitis and therefore poses a particular threat to consumer health (3,4).

L. monocytogenes ST6 is increasingly associated with outbreaks, including an outbreak linked to frozen vegetables in 5 countries in Europe during 2015–2018 (5), an outbreak associated with contaminated meat pâté in Switzerland during 2016 (6), and the largest listeriosis outbreak globally, which occurred in South Africa during 2017–2018 (7,8). More recently, the largest outbreak of listeriosis in Europe in the past 25 years was reported in Germany and was traced back to blood sausages contaminated with L. monocytogenes ST6 belonging to a particular clone referred to as Epsilon1a (9).

Human listeriosis is a reportable disease in Switzerland. All cases of culture- or PCR-confirmed human listeriosis are reported to the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (SFOPH). Diagnostic laboratories and regional (cantonal) laboratories forward isolates to the Swiss National Reference Centre for Enteropathogenic Bacteria and Listeria for strain characterization, ensuring early recognition of Listeria clusters among food isolates or human cases. We report an outbreak of listeriosis associated with cheese contaminated with L. monocytogenes 4b ST6 in Switzerland.

The Study

In 2018, the SFOPH recorded 52 human cases of listeriosis, corresponding to a normal annual incidence rate of 0.6 cases/100,000 inhabitants (10). However, during March 6, 2018–July 31, 2018, an increase of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b from 13 human cases was recorded. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) was performed on these strains by using MiSeq next generation sequencing technology (Illumina, https://www.illumina.com). Sequencing reads were mapped against an mutlilocus sequencing typing (MLST) scheme based on 7 housekeeping genes and a 1,701-locus core genome MLST (cgMLST) scheme by using Ridom SeqSphere+ software version 5.1.0 (11). STs and cluster types (CTs) were determined upon submission to the L. monocytogenes cgMLST Ridom SeqSphere+ server (https://www.cgmlst.org/ncs/schema/690488/).

A cluster was defined as a group of isolates with <10 different alleles between neighboring isolates (9,11). Twelve of 13 isolates were assigned to ST6 CT7448, a unique profile in the database, showed by cluster detection to be closely related. Accordingly, we defined an outbreak case-patient as a patient who had listeriosis and L. monocytogenes ST6 CT7448. An outbreak investigation was initiated by the SFOPH, and patients were contacted to assess food exposures by using a standardized questionnaire. Diagnostic and cantonal laboratories were notified nationwide to ensure rapid submission of L. monocytogenes isolates to the National Reference Centre for Enteropathogenic Bacteria and Listeria for laboratory typing, including WGS. However, the questionnaire-based outbreak investigation did not lead to a suspect food, and the vehicle of infection remained unknown.

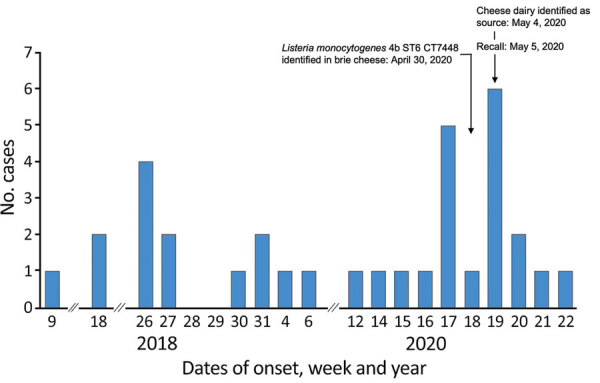

In a second wave, onset dates ranged from January 22 to May 26, 2020 (Figure 1). Another 27 cases of infection with L. monocytogenes serotype 4b were recorded; 4 cases were in hospital patients who had underlying conditions. During this period, questionnaire-based data were not available to support a food hypothesis.

Figure 1.

Cases of human listeriosis caused by Listeria monocytogenes ST6 CT7488, by week and year, Switzerland, 2018 and 2020. CT, cluster type; ST, sequence type.

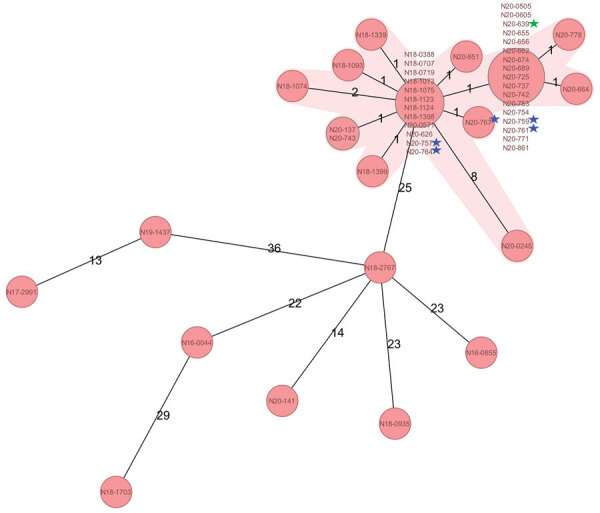

A total of 22 strains grouped on the basis of WGS in a tight cluster, with the exception of N20–2045, which differed by >8 alleles (Figure 2). This strain was within the cluster definition. However, in absence of supportive epidemiologic data, we were not able to verify whether N20–0245 was truly involved in the outbreak.

Figure 2.

Minimum-spanning tree based on cgMLST allelic profiles of 34 human Listeria monocytogenes isolates, 1 food isolate, and 5 environmental isolates, Switzerland. Each circle represents an allelic profile based on sequence analysis of 1,701 cgMLST target genes. Values on connecting lines indicate number of allelic differences between 2 strains. Each circle contains the strain identification(s). The food isolate is indicated by a green star, and environmental strains are indicated by blue stars. Outbreak strains are shaded in pink and are shown in comparison with other L. monocytogenes sequence type 6 isolates from Switzerland collected during 2016–2020. cgMLST, core genome multilocus sequence typing.

Median age of the patients was 81 years (range <1–99 years). More than half of the patients were female (18/34, 53%). Of the 34 human isolates, 30 were from blood samples and 1 each from an abscess, ascites, maternal placenta tissue, or stool sample (Table). One case of perinatal transmission and 10 deaths (29%) were reported.

Table. Listeria monocytogenes 4b sequence type 6 cluster type 7448 isolates associated with listeriosis outbreak, Switzerland, 2018–2020*.

| Isolate ID | Date of isolation | Origin | Source | Patient age, y/sex | BioSample accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N18–0388 | 2018 Mar 6 | Human | Blood | 82/F | SAMN15325567 |

| N18–0707 | 2018 Apr 30 | Human | Ascitic fluid | 79/F | SAMN15325568 |

| N18–0719 | 2018 May 2 | Human | Blood | 59/F | SAMN15325569 |

| N18–1073 | 2018 Jun 26 | Human | Blood | <1/F | SAMN15325570 |

| N18–1074 | 2018 Jun 26 | Human | Blood | 88/F | SAMN15325571 |

| N18–1075 | 2018 Jun 26 | Human | Maternal placenta tissue | 38/F | SAMN15325572 |

| N18–1093 | 2018 Jun 27 | Human | Blood | 82/M | SAMN15325573 |

| N18–1123 | 2018 Jul 3 | Human | Blood | 81/M | SAMN15325574 |

| N18–1124 | 2018 Jul 3 | Human | Blood | 99/M | SAMN15325575 |

| N18–1339 | 2018 Jul 24 | Human | Blood | 82/F | SAMN15325576 |

| N18–1398 | 2018 Jul 31 | Human | Blood | 48/M | SAMN15325577 |

| N18–1399 | 2018 Jul 31 | Human | Blood | 14/M | SAMN15325578 |

| N20–0137 | 2020 Jan 22 | Human | Blood | 77/M | SAMN15325579 |

| N20–0245 | 2020 Feb 7 | Human | Blood | 73/M | SAMN15325580 |

| N20–0505 | 2020 Mar 17 | Human | Blood | 73/M | SAMN15325581 |

| N20–0571 | 2020 Mar 30 | Human | Blood | 85/M | SAMN15325582 |

| N20–0605 | 2020 Apr 6 | Human | Blood | 73/M | SAMN15325583 |

| N20–0626 | 2020 Apr 15 | Human | Blood | 85/M | SAMN15325584 |

| N20–0655 | 2020 Apr 20 | Human | Blood | 66/F | SAMN15325585 |

| N20–0656 | 2020 Apr 20 | Human | Blood | 81/F | SAMN15325586 |

| N20–0662 | 2020 Apr 22 | Human | Blood | 86/F | SAMN15325587 |

| N20–0664 | 2020 Apr 22 | Human | Blood | 69/F | SAMN15325588 |

| N20–0674 | 2020 Apr 23 | Human | Blood | 84/F | SAMN15325589 |

| N20–689 | 2020 Apr 29 | Human | Blood | 63/F | SAMN15325590 |

| N20–725 | 2020 May 4 | Human | Blood | 81/M | SAMN15325592 |

| N20–737 | 2020 May 5 | Human | Blood | 86/M | SAMN15325593 |

| N20–742 | 2020 May 6 | Human | Blood | 78/F | SAMN15325594 |

| N20–743 | 2020 May 6 | Human | Blood | 37/M | SAMN15325595 |

| N20–753 | 2020 May 8 | Human | Blood | 75/M | SAMN15325596 |

| N20–754 | 2020 May 8 | Human | Blood | 85/F | SAMN15325597 |

| N20–771 | 2020 May 11 | Human | Blood | 95/F | SAMN15325598 |

| N20–778 | 2020 May 12 | Human | Blood | 95/F | SAMN15325599 |

| N20–851 | 2020 May 22 | Human | Perianal abscess | 85/M | SAMN15325600 |

| N20–861 | 2020 May 26 | Human | Blood | 83/F | SAMN15325601 |

| N20–639 | 2020 Apr 30 | Food | Cheese sample | NA/NA | SAMN15325591 |

| N20–757 | 2020 May 3 | Environment | Scrub sponge | NA/NA | SAMN15375881 |

| N20–759 | 2020 May 3 | Environment | Drainage channel | NA/NA | SAMN15375882 |

| N20–761 | 2020 May 3 | Environment | Door handle | NA/NA | SAMN15375884 |

| N20–764 | 2020 May 3 | Environment | Cellar floor | NA/NA | SAMN15375885 |

| N20–767 | 2020 May 3 | Environment | Ripening cellar floor | NA/NA | SAMN15375883 |

*ID, identification; NA, not applicable.

On April 30, 2020, a cheese manufacturer reported to the cantonal laboratory detection of L. monocytogenes from a sample of soft (brie) cheese made from pasteurized milk. Analysis had been conducted as part of the manufacturer’s routine quality control practices, which are mandatory in Switzerland (Swiss Foodstuffs Act, Article 23). The cheese isolate N20–639 matched the outbreak strain CT by WGS (Table; Figure 2). The cantonal authorities started the tracing of the distribution chain of the dairy. The cheese producer supplied several buyers who provide cheese to retailers throughout Switzerland. The buyers were requested to immediately stop the delivery of the products of this specific producer.

These findings prompted extensive environmental sampling on the production site of the manufacturer. A total of 50 swab specimens from locations, such as vats, cheese harps, skimming devices, sink drains, brushes, scrub sponges, trays, door handles, ripening cellar floors, and walls were obtained. Swabs were incubated in Half Frazer Broth (Bio-Rad, https://www.bio-rad.com) at 30°C for 48 h. L. monocytogenes was detected by real-time PCR with the Assurance Genetic Detection System (Endotell, https://www.endotell.ch) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To obtain strains for WGS, 5 enriched Half Frazer Broth cultures were streaked on chromogenic Listeria agar plates (Oxoid, Pratteln, Switzerland) and incubated at 37°C for 24 h.

L. monocytogenes was identified in 11 (22%) of 50 environmental samples, and all 5 sequenced isolates matched the outbreak strain CT (Table; Figure 2). These results lead to a recall on May 5, 2020, of 26 items, including brie, sheep and goat cheese, and organic cheeses; production was stopped immediately. The findings were reported to the Epidemic Intelligence Information System for Food and Waterborne Diseases and Zoonoses. After the recall of the implicated products and a public warning issued by the Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office, 7 cases of listeriosis caused by the outbreak strain were recorded (Figure 1). The last known case caused by this outbreak strain was sampled on May 20, 2020, and reported to SFOPH on May 25, 2020. Sequence data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, MD, USA) BioSample database under project no. PRJNA640586. We provide accession numbers (Table).

Conclusions

This prolonged outbreak of L. monocytogenes 4b ST6 CT7448 caused 34 laboratory-confirmed listeriosis cases and 10 deaths. The outbreak investigation is an example of successful collaboration between laboratories and food safety and public health authorities to determine sources of contamination and reconstruct outbreak development. The results of the investigation implicated a cheese dairy with sanitation shortcomings and persisting environmental contamination throughout the production site. Isolation and WGS typing of L. monocytogenes from a quality-control cheese sample provided crucial information that enabled identification of the origin of contamination. WGS played a key role in showing close relatedness between the isolates from the cheese item and from the environment, and in linking the listeriosis cases from 2018 to the 2020 outbreak.

This outbreak highlights the risk for recontamination of pasteurized cheese products during manufacturing and emphasizes the need for routine sampling of products, manufacturing equipment, and the production environment. Routine quality controls should include WGS typing of environmental L. monocytogenes isolates to enable early recognition of potential food contamination and to ultimately mitigate the risk for listeriosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health and the Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office for critically reviewing the manuscript.

This study was partly supported by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, Division Communicable Diseases.

Biography

Dr. Nüesch-Inderbinen is a research associate at the Institute for Food Safety and Hygiene, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland. Her primary research interest is pathogenic and antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in humans, animals, and the food chain.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Nüesch-Inderbinen M, Bloemberg GV, Müller A, Stevens MJA, Cernela N, Kollöffel B, et al. Listeriosis caused by persistence of Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b sequence type 6 in cheese production environment. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021 Jan [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2701.203266

References

- 1.Allerberger F, Wagner M. Listeriosis: a resurgent foodborne infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:16–23. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03109.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchanan RL, Gorris LG, Hayman MM, Jackson TC, Whiting RC. A review of Listeria monocytogenes: an update on outbreaks, virulence, dose-response, ecology, and risk assessments. Food Control. 2017;75:1–13. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.12.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maury MM, Tsai YH, Charlier C, Touchon M, Chenal-Francisque V, Leclercq A, et al. Uncovering Listeria monocytogenes hypervirulence by harnessing its biodiversity. Nat Genet. 2016;48:308–13. 10.1038/ng.3501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koopmans MM, Brouwer MC, Bijlsma MW, Bovenkerk S, Keijzers W, van der Ende A, et al. Listeria monocytogenes sequence type 6 and increased rate of unfavorable outcome in meningitis: epidemiologic cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:247–53. 10.1093/cid/cit250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Multi-country outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes PCR serogroup IVb MLST ST6, 2017. [cited 2020 Jun 6]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/rapid-risk-assessment-multi-country-outbreak-listeria-monocytogenes-pcr-serogroup

- 6.Althaus D, Jermini M, Giannini P, Martinetti G, Reinholz D, Nüesch-Inderbinen M, et al. Local outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b sequence type 6 due to contaminated meat pâté. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2017;14:219–22. 10.1089/fpd.2016.2232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas J, Govender N, McCarthy KM, Erasmus LK, Doyle TJ, Allam M, et al. Outbreak of listeriosis in South Africa associated with processed meat. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:632–43. 10.1056/NEJMoa1907462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith AM, Tau NP, Smouse SL, Allam M, Ismail A, Ramalwa NR, et al. Outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes in South Africa, 2017–2018: laboratory activities and experiences associated with whole-genome sequencing analysis of isolates. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2019;16:524–30. 10.1089/fpd.2018.2586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halbedel S, Wilking H, Holzer A, Kleta S, Fischer MA, Lüth S, et al. Large nationwide outbreak of invasive listeriosis associated with blood sausage, Germany, 2018–2019. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1456–64. 10.3201/eid2607.200225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Food Safety Authority. Trends and sources of zoonoses and zoonotic agents in foodstuffs, animals and feedingstuffs including information on foodborne outbreaks, antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria and some pathogenic microbiological agents in 2018. [cited 2020 Jun 6]. https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/zoocountryreport18ch.pdf

- 11.Ruppitsch W, Pietzka A, Prior K, Bletz S, Fernandez HL, Allerberger F, et al. Defining and evaluating a core genome multilocus sequence typing scheme for whole-genome sequence-based typing of Listeria monocytogenes. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2869–76. 10.1128/JCM.01193-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]