Abstract

Effective psychotherapies for late-life depression are underutilized, mainly because of their complexity. “Engage” is a novel, streamlined psychotherapy that relies on neurobiology to identify core behavioral pathology of late-life depression and targets it with simple interventions, co-designed with community therapists so that they can be delivered in community settings. Consecutively recruited adults (≥60 years) with major depression (n=249) were randomly assigned to 9 weekly sessions of “Engage” or to the evidence-based Problem-Solving Therapy (PST) offered by 35 trained community social workers and assessed by blind raters. “Engage” therapists required an average of 30% less training time to achieve fidelity to treatment than PST therapists and had one third of the PST therapists’ skill drift. Both treatments led to reduction of HAM-D scores over 9 weeks. The mixed effects model-estimated HAM-D ratings were not significantly different between the two treatments at any assessment point of the trial. The one-sided 95% CI for treatment-end difference was (−∞, 0.07) HAM-D points, indicating a non-inferiority margin of 1.3 HAM-D points or greater; this margin is lower than the pre-determined 2.2-point margin. The two treatment arms had similar response (HR = 1.08, 95% CI (0.76, 1.52), p = 0.67) and remission rates (HR = 0.89, 95% CI (0.57, 1.39), p = 0.61). We conclude that “Engage” is non-inferior to PST. If disseminated, “Engage” will increase the number of therapists who can reliably treat late-life depression and make effective psychotherapy available to large numbers of depressed older adults.

INTRODUCTION

Most depressed older adults are treated with antidepressants despite their modest efficacy in late-life major depression. 1,2 The public health impact of antidepressants is further attenuated by poor adherence, inadequate dosages, and infrequent follow up.3,4 Effective psychotherapies for late-life depression exist.5–8 Surveys indicate that older adults prefer psychosocial interventions but rarely receive them3,9–11, to a large extent, because of the limited availability of therapists in the community who are trained and able to maintain their skills in evidence-based therapies.12,13,14,15,16 A solution is to streamline psychotherapy so that it can be accessible by community therapists.17

To address this need, we created “Engage”, a psychotherapy based on two domains of knowledge. First, “Engage” relies on neurobiology concepts of depression to identify core behavioral pathology of late-life depression.18 By focusing on core pathology, “Engage” limits its behavioral targets and reduces the number of decisions therapists must make. Second, “Engage” addresses core pathology with simple cognitive-behavioral interventions of known efficacy that have been found acceptable by therapists.19 As a result, “Engage” relies on a parsimonious set of efficacious strategies to address behaviors originating from core neurobiological dysfunctions of depression.18,19

“Engage” theorizes that impairment in reward network functions is a process central to late-life depression.18 This view is supported by animal models of depression in which stressors influence the structure and function of circuits of reward-related, depression-like behaviors.20 Humans with depression have impaired reward valuation functions and impaired communication among neural substrates of expected value estimation and decision-making.21 Deficient reward responsiveness is accompanied by dysconnectivity of the nucleus accumbens, a central reward-processing node, with specific large-scale functional brain networks.22 Depressed patients show lower memory of observed rewards and have impaired ability to use internal value estimations to guide decision-making.23 Along with depression, aging impairs reward processing, reduces the adaptation to changes in reward contingencies,24 and increases sensitivity to punishment.25 Based on the view that abnormal reward functions mediate the clinical expression of depression, “Engage” uses “reward exposure” as its central intervention. Accordingly, “Engage” guides patients to participate in rewarding activities of increasing complexity to stimulate reward functions.

Negativity bias, apathy, and inadequate emotional regulation are clinical manifestations of depression that may serve as barriers to “reward exposure”. Negativity bias, consisting of preferential attention to negative information, confers vulnerability to depression, persists after remission of depression, and increases the risk of relapse.26,27,28,29 In Iate-life depression, apathy is accompanied by abnormal resting functional connectivity of reward and salience network structures.30 Inadequate emotional regulation may be an expression of dysfunction of the cognitive control network, resulting from abnormal interaction of the ventral-rostral anterior cingulate with the medial prefrontal cortex, responsible for appraisal and regulation of emotional functions, and with limbic subcortical circuits mediating emotion processing.31

Engage is personalized through a structured, stepped approach and offers interventions for negativity bias (negative valence systems), apathy (reward and salience networks), and/or emotional dysregulation (cognitive control system) only if they impede “reward exposure”. Its interventions were co-designed with community therapists so that the interventions are acceptable and feasible to deliver in community settings. This approach was taken because a barrier to availability of evidence-based psychotherapies is their acceptability by community therapists. The “Engage” steps are explicitly defined so that they can be easily taught to many clinicians and understood by depressed older patients.

This study compared the efficacy of Engage to that of Problem-Solving Therapy (PST) both offered by trained, community-based therapists. PST is an evidence-based therapy for late-life major depression.6,5,32 Unlike Engage, the premise of PST is that teaching depressed patients to reconceptualize and address problems as they occur alleviates depression. Despite its demonstrated efficacy, PST is underutilized principally because therapists have difficulty learning and consistently utilizing the skills of PST.19,33 This study tested the hypothesis that Engage is non-inferior to PST in reducing symptoms of major depression, with comparable probabilities of response and remission.

METHOD

This two-center, randomized clinical non-inferiority trial compared the efficacy of “Engage” to PST participants, recruited by research teams of Weill-Cornell Medicine and the University of Washington (UW) between 2014 and 2019. Study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of both universities.

Selection Criteria:

Inclusion criteria were: 1) Age≥ 60 years; 2) unipolar, non-psychotic major depression (by SCID,34 DSM-IV); 3) Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)35≥ 20; 4) Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)36 ≥ 24; 5) off antidepressants or on a stable dose of an antidepressant for 12 weeks and no plan to change the dose in the next 10 weeks; and 6) capacity to consent.

Exclusion Criteria:

1) Intent or plan to attempt suicide ; 2) Psychiatric diagnoses other than unipolar, non-psychotic major depression or generalized anxiety disorder; 3) Psychotropic drugs or cholinesterase inhibitors other than a stable course of antidepressants and mild doses of benzodiazepines, i.e., lorazepam up to 1.5 mg daily dose or the equivalent of other benzodiazepines.

Systematic Assessment

Participants were assessed by trained research assistants. Diagnosis of depression was assigned in conferences by agreement of two clinician investigators after review of history, the SCID-R ratings and other data obtained by interviewers.34 Baseline assessment included the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale,37 the Beck Hopelessness Scale,38 the Apathy Evaluation Scale,39 the Positive and Negative Affect Scale, and the Behavioral Activation for Depression Scale40 to assess hedonic capacity, hopelessness, apathy, positive and negative affect, and behavioral activation respectively. Neuroticism was assessed with the subscale of the NEO Personality Inventory at baseline.41 Disability was quantified with the World Health Organization Assessment Schedule II (WHODAS-II).42

The 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D)43 was used as the primary outcome measure because of its use in randomized clinical trials (RCTs), including an earlier proof of concept study comparing “Engage” with PST.30 The MADRS was used as an inclusion criterion because using the same instrument for both eligibility and outcome may lead to early rapid decline in depression scores.44 The HAM-D was administered at baseline and at weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, and 9. Treatment response was defined as a 50% reduction of the baseline HAM-D score. Remission was defined as the attainment of HAM-D≤10 for two consecutive assessment points. This definition of remission is commonly used in studies of depressed older adults whose physical symptoms overlap with symptoms of depression.45

Randomization and Blinding

The study statistician (SB) randomized participants to 9 weekly sessions of either “Engage” or PST at each site using blocked 1:1 randomization with randomly selected block sizes. A similar process was used to randomize therapists to Engage or PST at the outset of the study. Raters were blind to the participant’s randomization status and hypotheses. Therapists were aware of participants’ randomization but not of the hypotheses.

Treatment

Treatment was offered by licensed community social workers randomly assigned to offer either “Engage” or PST. Training in “Engage” or PST was conducted separately in 3 steps: 1: Therapists studied the “Engage” or the PST Manual (Appendix) and clinician investigators (PA, PJR, BR) held a didactic on the intervention; 2) Therapists engaged in one-to-one role-play sessions with trainers (PA, PJR, PM, and BR) who evaluated their fidelity to “Engage” or PST with Adherence Scales (range 1-5); 3) Therapists treated three practice cases and had to achieve treatment fidelity (Adherence Scale score ≥3 satisfactory) on 3 consecutive sessions to be certified; their fidelity scores were assigned by independent raters who were treatment experts and not members of the research team. “Training time” was the sum of a fixed 1.5 hours of didactics, plus varying numbers of role plays needed to achieve fidelity, plus varying numbers of audiotapes needed to achieve fidelity to 3 therapy practice sessions. We randomly selected one session per case during the study to be rated for fidelity by an expert who was not a member of the research team, and we operationalized skill drift dichotomously (Adherence Scale score<3).

“Engage”.

“Engage” begins with “reward exposure”. Patients and therapists develop a list of rewarding social and physical activities and select 2-3 activities to pursue between sessions. During sessions, they: 1. Select a rewarding activity goal; 2. Develop a list of ideas of ways to meet this goal; 3. Choose one of these ideas; and 4. Make an action plan with concrete steps. When patients do not engage or benefit by rewarding activities, the initial three sessions offer observations that guide the therapist to identify the primary barrier to reward exposure (negativity bias, apathy, or emotional dysregulation) and address this barrier with explicitly defined strategies (stepped treatment). A second assessment of barriers to reward exposure occurs between sessions 3-6, and strategies targeting an emerging barrier are introduced when needed.

PST.

The first five weeks are devoted to training patients in the 7-step problem-solving model and subsequent sessions enhance PST skills. Participants are guided to identify problems, set goals to address these problems, propose ways for reaching these goals, create action plans, and evaluate the accomplishment of their goals. They are also instructed to apply the problem-solving model to additional problems between sessions. In the last two sessions, participants create a relapse prevention plan using the PST model.

Data Analysis:

Mixed-effects linear regression analyses46 compared the trajectories of HAM-D scores between “Engage” and PST and included fixed effects for treatment (“Engage” vs. PST), site (Cornell vs. UW), time, treatment x time interaction and a subject-specific random intercept. The model was further adjusted for the imbalance of baseline covariates (i.e. neuroticism and self-efficacy) between the two treatment groups (p ≤ 0.05) that were significantly associated with HAM-D trajectories; these were identified after univariate analysis of each potential covariate (Table 1) in separate mixed effects regression models. The calendar time from baseline to follow-up assessments at weeks 2, 4, 6, 8 and 9 varied, therefore, time was used as a continuous variable. A quadratic time model was chosen based on the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). Pattern mixture modelling47 showed that the treatment effect did not significantly differ between dropout patterns suggesting that data were likely missing at random (MAR). Initially, we introduced a random intercept for therapists (N=35) but removed it from the final model because the variance of the therapists’ intercept was 0. The HAM-D scores estimated by the mixed model were tested for treatment group differences at each assessment point. Group differences in 9-week improvement in HAM-D scores from baseline were also tested from the mixed model. Non-inferiority of “Engage” compared to PST was tested by constructing one-sided 95% CI for the model estimated treatment difference in HAM-D at week 9. The non-inferiority margin (NIM) was pre-determined to be 2.2 HAM-D points at treatment end based on a commonly accepted margin for non-inferiority of antidepressants in placebo-controlled trials.48

Table 1:

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of 249 Older Participants with Major Depression

| Number of Participants (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Characteristics | Engage (n=129) | PST (n=120) | P value | Overall (n=249) |

| Sociodemographic | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 69.3 (7.5) | 71.2 (7.2) | 0.04 | 70.2 (7.4) |

|

| ||||

| Range | 60–89 | 60–89 | ||

|

| ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 43 (33.3) | 37 (30.8) | 0.68 | 80 (32.1) |

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

| Black | 3 (2.3) | 9 (7.5) | 0.07 | 12 (4.8) |

| White | 120 (93.0) | 101 (84.2) | 221 (88.8) | |

| Other | 6 (4.7) | 10 (8.3) | 16 (6.4) | |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 6 (4.7) | 5 (4.2) | 0.99 | 11 (4.4) |

|

| ||||

| Education, mean (SD), years | 16.0 (2.7) | 16.3 (2.5) | 0.45 | 16.1 (2.6) |

|

| ||||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 42 (32.6) | 44 (36.7) | 0.59 | 86 (34.5) |

|

| ||||

| Clinical Characteristics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age of onset, mean (SD), y | 44.8 (24.7) | 45.1 (23.8) | 0.97 | 44.9 (24.2) |

|

| ||||

| Number of previous depressive episodes, mean (SD) | 4.1 (5.7) | 4.1 (5.9) | 0.99 | 4.1 (5.8) |

|

| ||||

| MADRS mean (SD) | 25.2 (4.4) | 25.6 (4.1) | 0.47 | 25.4 (4.3) |

|

| ||||

| HAM-D-24, mean (SD) | 23.1 (4.1) | 23.4 (4.3) | 0.63 | 23.2 (4.2) |

|

| ||||

| MMSE, mean (SD) | 28.8 (1.1) | 28.6 (1.4) | 0.10 | 28.7 (1.3) |

|

| ||||

| WHODAS, mean (SD) | 28.9 (8.0) | 27.9 (7.7) | 0.35 | 28.4 (7.9) |

|

| ||||

| SHAPS, mean (SD) | 2.9 (2.9) | 2.3 (2.4) | 0.10 | 2.6 (2.7) |

|

| ||||

| AES, mean (SD) | 37.5 (8.2) | 36.2 (9.1) | 0.24 | 36.9 (8.7) |

|

| ||||

| Beck Helplessness, mean (SD) | 18.4 (4.7) | 17.8 (4.9) | 0.31 | 18.1 (4.8) |

|

| ||||

| GSE, mean (SD) | 27.1 (5.5) | 28.5 (5.0) | 0.04 | 27.7 (5.3) |

|

| ||||

| NEO, Neuroticism, mean (SD) | 18.5 (4.7) | 17.3 (5.0) | 0.05 | 17.9 (4.9) |

|

| ||||

| On antidepressants during the trial | 50 (38.8) | 55 (45.8) | 0.26 | 105 (42.2) |

| Ever taken antidepressants | 78 (60.5) | 85 (70.8) | 0.10 | 163 (65.5) |

|

| ||||

| BADS, mean (SD) | 73.5 (20.5) | 75.1 (20.3) | 0.55 | 74.2 (20.4) |

|

| ||||

| PANAS Positive Affect, mean (SD) | 23.5 (7.1) | 24.7 (6.1) | 0.36 | 24.1 (6.6) |

|

| ||||

| PANAS Negative Affect, mean (SD) | 26.7 (7.0) | 25.9 (8.6) | 0.62 | 26.3 (7.8) |

SD=Standard Deviation

HAM-D-24: 24 item, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination, SHAPS: Snaith Hamilton Pleasure Scale; AES: Apathy Evaluation Scale; BHS: Beck Hopelessness Scale; GSE: General Self-Efficacy Scale; NEO: NEO Personality Inventory; BADS: Behavioral Activation for Depression Scale; PANAS: Positive and Negative Affect Scale;

Kaplan-Meier curves described the time to treatment response and remission, and group differences were tested with log-rank tests. Response and remission were analyzed with Cox proportional hazards model after adjusting for the imbalance of baseline covariates (i.e. neuroticism and general self-efficacy) between the two treatment groups (p ≤ 0.05) that were also significantly associated with time to remission and time to response. These were identified after univariate analysis of each potential covariate (Table 1) in separate Cox regression models.

Power analysis

A sample of N=300 had power of >88% to conclude non-inferiority of “Engage” compared to PST in the post-treatment difference in HAM-D scores. This assumed a non-inferiority margin of 0.29 for the standardized effect size, which corresponds to 2.2 HAM-D points, a 20% attrition rate (effective sample size N=240), and the true post-treatment HAM-D difference of zero between the treatment arms. Under similar assumptions, we had >83.4% power to conclude non-inferiority of HAM-D when the true post-treatment difference favored PST by a standardized effect size of 0.1 or 6 HAM-D points.

RESULTS

Recruitment and Clinical Characteristics

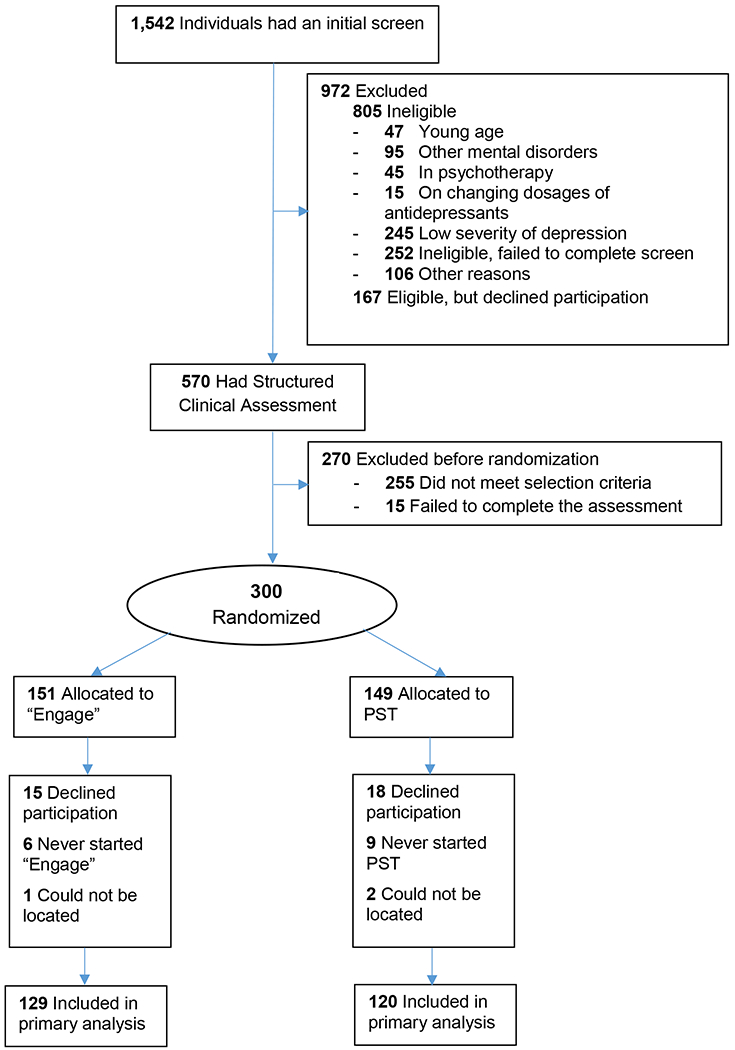

Participants were solicited through advertisements and clinical referrals. Of 1,542 individuals screened, 805 were ineligible and 167 met the screening criteria but declined to participate (Figure 1). The remaining 570 underwent a structured interview, which led to exclusion of 270 individuals. Of the 300 randomized participants, 151 were assigned to the “Engage” arm and 149 to the PST arm. Of those randomized, 22 in the “Engage” arm and 29 in the PST arm did not attend any therapy sessions, as a result 129 “Engage” and 120 PST participants were included in the primary analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow of Participants in the “Engage” vs. PST Trial

Those who entered the trial had major depression of moderate severity (Table 1). “Engage” participants were an average 1.9 years younger and had somewhat higher neuroticism scores and lower self-efficacy scores than PST participants. There were no other significant differences in baseline variables among participants assigned to the two treatments in bivariate comparisons uncorrected for multiple comparisons. Approximately 38.8% of “Engage” and 45.8% of PST participants had been on unchanged dosages of antidepressants prior to study entry and remained on the same dosages during the trial. There were no statistically significant differences in demographics, depression severity, medical burden or disability among participants who had been on antidepressants and those who were not on antidepressants.

Attrition

Of the 249 participants, 82.2% of “Engage” and 82.5% of PST participants completed treatment and the week 9 assessment. The mean number of sessions attended by the “Engage” group was 7.99 (SD: 2.29) and 7.93 (SD: 2.33) by the PST group, i.e. 88.8% and 88.1% of all sessions. The median number of sessions for each group was 9.

Therapist Training and Skill Drift

We recruited 35 community social workers at Cornell and UW and randomly assigned to train in Engage or PST and treat their assigned participants. Engage therapists (n=17) required 12.0 total training hours (sd=3.0) to achieve certification, while PST therapists (n=18) required 19.2 (sd=7.9) (t=−3.24(df=30), p=0.003). Three PST therapists failed to achieve certification and were excluded from further study participation, while all Engage therapists met fidelity standards and were assigned study cases. 5 of 63 Engage sessions (7.9%) and 14 of 59 PST sessions (23.7%) fell below fidelity standards (ratings <3) (chi=5.78 (df=1), p=0.016).

Treatment Outcomes

Severity of Depression

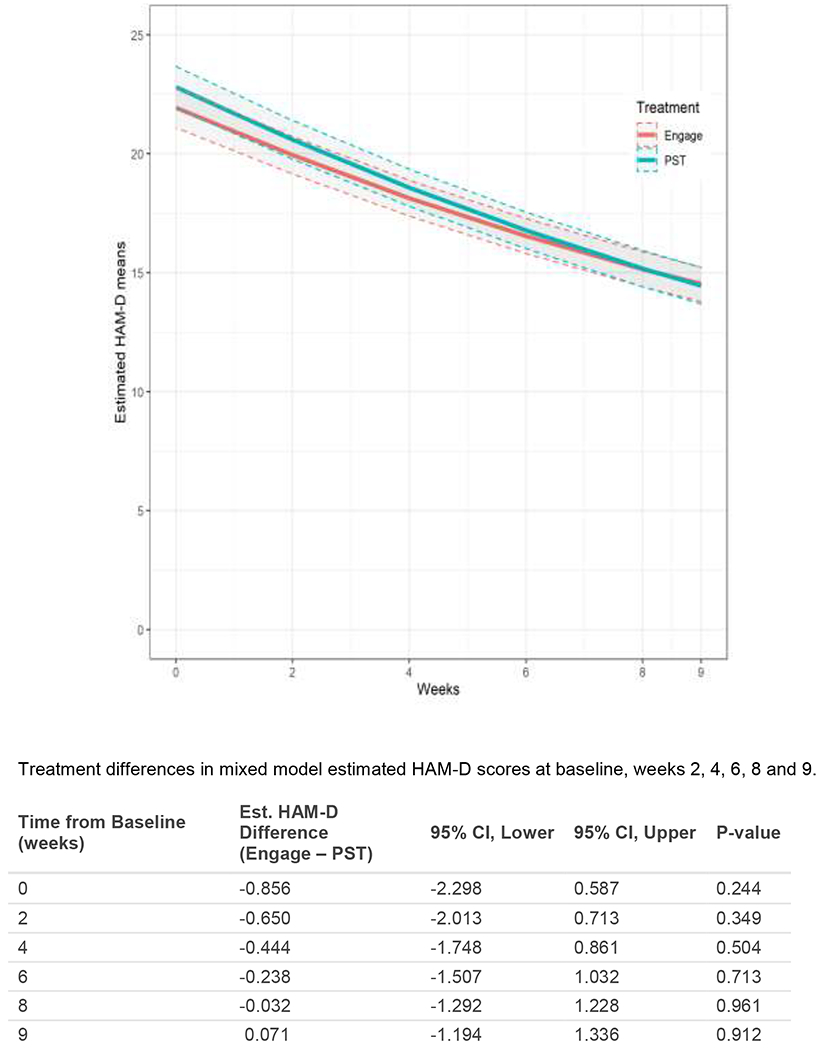

We used mixed effects regression to model the trajectory of depression severity for the two treatment groups. Both treatments were associated with reduction of HAM-D scores; 9-week improvement in “Engage” model estimated mean (95% CI) = 7.42 (6.76, 8.07) and 9-week improvement in PST model estimated mean (95% CI) = 8.34 (7.66, 9.03). Improvement in depression severity from baseline to week 9 in “Engage” participants was 0.92 HAM-D points lower than PST 95% CI (−0.269, 2.123). This 9-week change in HAM-D scores was not significantly different between the two treatment arms (p=0.23). The model estimated HAM-D points were also not significantly different at baseline, weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, and 9 (Figure 2). The end of treatment (9 weeks) model estimated depression severity in “Engage” participants was 0.07 HAM-D points higher than that of PST participants; this difference was not statistically significant. The upper bound of the one sided 95% CI was 1.13 indicating that “Engage” is non-inferior to PST with a margin of 1.13 HAM-D points or greater; this non-inferiority margin is lower than the pre-set 2.2-point margin.

Figure 2.

Model-based HAM-D Trajectories: Mixed Model Estimated Least Square Means of HAM-D by treatment arm over the treatment period of 9 weeks.

Treatment Response.

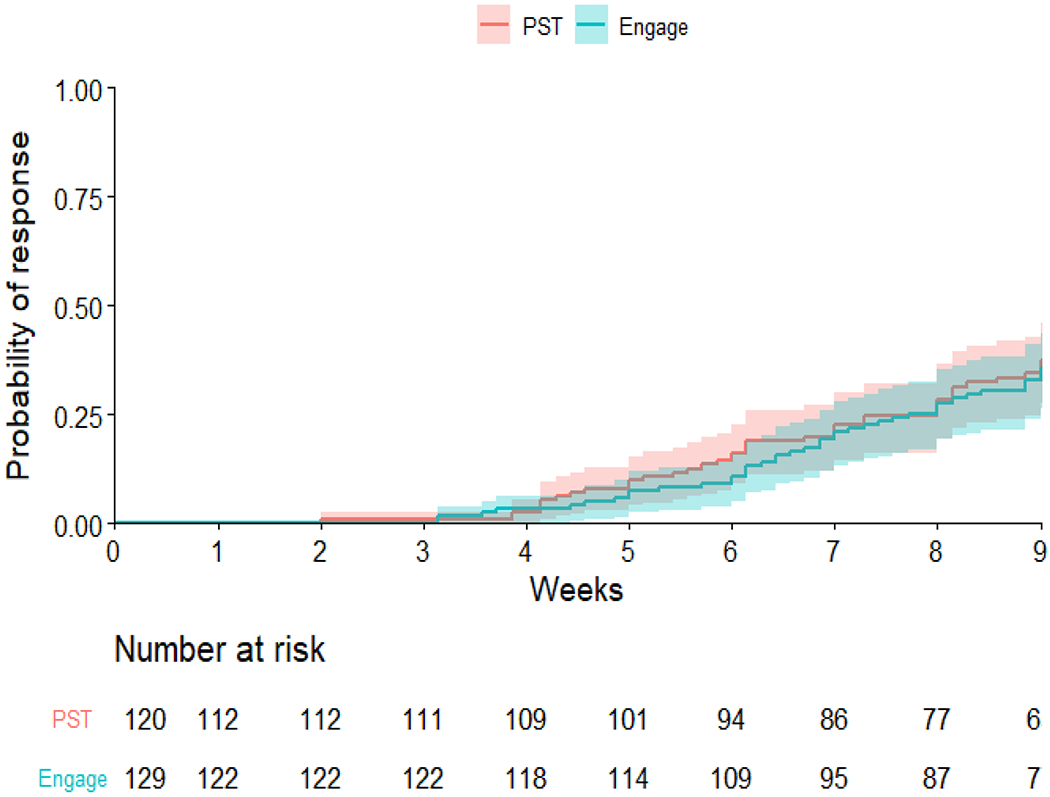

In the Engage arm, 75 participants (58.14%) responded to treatment (50% reduction in HAM-D from baseline), while 65 participants (54.17%) responded in the PST arm. Among those who achieved response by 9 weeks, the average time to response was 6.63 weeks (SD=1.66) in Engage and 6.37 weeks (SD=1.79) in PST and (t=0.68, df=78.87, p=0.50). Survival analysis of time to response showed that the two treatment arms had comparable probabilities of non-response (log-rank χ2(1)=0.1, p=0.8; Figure 3). After adjusting for site, neuroticism and self-efficacy at baseline, the Cox proportional hazard model showed that the two treatment arms had similar response times [HR (Engage vs. PST)= 1.08, 95% CI (0.76, 1.52), p = 0.67].

Figure 3.

Probability of achieving treatment response: Group comparison of the probability of achieving treatment response (50% reduction of Ham-D from baseline) showed no significant difference (log-rank test P value=0.8). The shaded area represents the 95% CIs.

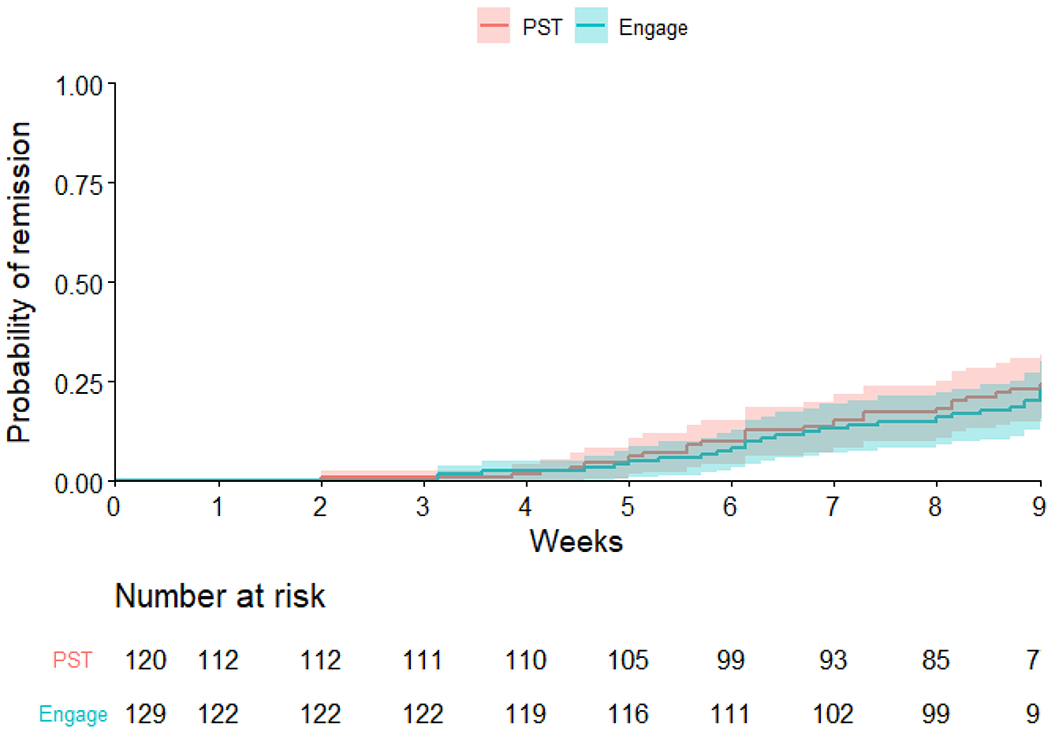

Remission.

In the Engage arm, 38 participants (29.5%) achieved remission (HAM-D ≤ 10 for two consecutive assessments), while 42 participants (35%) remitted in the PST arm. Among those who achieved remission by 9 weeks, the average time to remission was 6.60 weeks (SD=1.83) in Engage 6.29 weeks (SD=1.75) in PST (t=0.63, df=51.00, p=0.53). Survival analysis of time to first achieved remission showed that the two treatment arms had comparable probabilities of non-remission (log-rank χ2(1)=1.6, p=0.20; Figure 4). After adjusting for site, neuroticism and self-efficacy at baseline, the Cox proportional hazard model showed that the two treatment arms had similar remission times [HR (Engage vs. PST) = 0.89, 95% CI (0.57, 1.39), p = 0.61].

Figure 4.

Probability of remission: Group comparison of the probability of achieving remission (HAM-D ≤10 in 2 consecutive assessments) showed no significant difference (log-rank test P value=0.20). The shaded area represents the 95% CIs.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that “Engage” is non-inferior to problem-solving therapy (PST) in reducing depressive symptoms and documented that both treatments led to similar response and remission rates. PST is a powerful evidence-based therapy for major depression that yielded one additional response or remission over supportive therapy for every 4.4 and 5.6 patients respectively by the end of a 12-week trial.5 This is the first RCT to compare the efficacy of “Engage” with a psychotherapy of known efficacy. Its findings are consistent with an earlier proof of concept study in which “Engage” was non-inferior to PST when administered to older historical controls with major depression.30 Importantly, “Engage” therapists required an average of 30% less training time to achieve fidelity to treatment than PST therapists and had one third of the PST therapists’ skill drift.

The principal innovation of “Engage” is its reliance on neurobiological concepts that permit it to focus on core behavioral pathology of late-life depression and to simplify its treatment structure. Identifying reward network dysfunction as a critical abnormality in depression led “Engage” to rely on the simple-to-learn “reward exposure” strategy as its principal intervention. Similarly, identifying three common neurobiologically-based barriers to reward exposure (negativity bias, apathy, inadequate emotion regulation) provided explicit targets for personalization.

An additional innovation is the streamlined and stepped approach to administering targeted behavioral treatment in a manner that is acceptable and easy to use by clinicians and patients. Stepped care was developed in the UK to expand its small mental health workforce and increase the referral options of general practitioners.49 Starting “Engage” treatment with “reward exposure” is parsimonious and an instructive avenue for stepped care. Barriers to rewarding activities not immediately apparent may emerge after attempts to pursue these activities. Thus, “Engage” is a timed and targeted personalized treatment that offers only the interventions each patient needs. Its approach is parsimonious and simpler than the personalization methods of other evidence-based psychotherapies that usually apply modular or preference matching personalization of treatment.50

The rather short training and the low skill drift suggest that “Engage” may be used by non-specialized health workers or by educated lay counselors in prevention studies of older adults at risk for late-life depression. A version of PST, combined with brief behavioral treatment for insomnia, education in self-care of common medical disorders and assistance in accessing medical and social programs was found effective for preventing episodes of major depression in older persons with subsyndromal depression.51 However, a prevention study needs to be conducted if a version of “Engage” is to be clinically used in populations at risk for late-life depression.

Although “Engage” had comparable effectiveness to that of PST, a significant number of patients failed to achieve remission and continued to experience symptoms of depression. Residual depressive symptoms, including anxiety and sleep disturbance, predict early relapse and recurrence of late-life depression.52–54 Extending acute treatment, e.g. to 12 weekly sessions may have increased the response and remission rate. Biweekly sessions of continuation treatment over 4-6 months may have reduced subsyndromal symptoms and monthly sessions of maintenance therapy may have improved the probability of remaining well. While reasonable, these assumptions need to be tested by controlled studies. Clinically, patients with a trajectory of continuing improvement may benefit from additional “Engage” sessions and “Engage” may be combined with pharmacotherapy in patients with persistent symptoms.

The study’s findings should be viewed in the context of its limitations. A large number of screened individuals failed to reach the randomized sample of cognitively unimpaired older adults with major depression. Exclusion of many individuals may have favored the inclusion of highly motivated patients and inflated the positive outcomes of both treatments. The high number of sessions of both treatments attended by patients and the low attrition rate during the RCT, while they are strengths of the study, they also suggest that participants were motivated for treatment. The severity of depression was in the mild to moderate range, a population usually treated with psychotherapy. The participants had no psychiatric co-morbidity other than generalized anxiety disorder. For this reason, no conclusions can be drawn about the efficacy of “Engage” in unmotivated depressed older patients with additional psychiatric diagnoses or high severity of depression. The time between assessments varied among participants in both arms, therefore, treatment effects were estimated from the statistical models at the pre-planned follow-up time periods.

In sum, “Engage” was non-inferior to PST, a powerful, evidence-based treatment of late-life major depression. Reduction of behavioral targets based on neurobiology concepts, use of few efficacious strategies, and stepped personalization led to a streamlined treatment that can be mastered by community clinicians. If disseminated, “Engage” will increase the number of therapists who can reliably treat late-life depression and make effective psychotherapy available to large numbers of depressed older adults.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by R01 MH102252 (GSA), R01 MH102304 (PAA), P50 MH113838 (GSA), T32 MH019132 (GSA), and P50 MH115837 (PAA)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: Dr. Alexopoulos served on Advisory Board of Eisai and of Janssen Pharmaceuticals. He also served on the Speakers Bureaus of Allergan, Otsuka, and Takeda-Lundbeck. Thomas Hull is an employee of ‘Talkspace.’ All other authors report no conflicts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maust DT, Kales HC, Blow FC. Mental Health Care Delivered to Younger and Older Adults by Office-Based Physicians Nationally. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(7):1364–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson JC, Delucchi K, Schneider LS. Efficacy of second generation antidepressants in late-life depression: a meta-analysis of the evidence. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(7):558–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zivin K, Kales HC. Adherence to depression treatment in older adults: a narrative review. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(7):559–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Driscoll HC, Karp JF, Dew MA, Reynolds CF 3rd. Getting better, getting well: understanding and managing partial and non-response to pharmacological treatment of non-psychotic major depression in old age. Drugs Aging. 2007;24(10):801–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arean PA, Raue P, Mackin RS, Kanellopoulos D, McCulloch C, Alexopoulos GS. Problem-solving therapy and supportive therapy in older adults with major depression and executive dysfunction. The American journal of psychiatry. 2010;167(11):1391–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arean PA, Perri MG, Nezu AM, Schein RL, Christopher F, Joseph TX. Comparative effectiveness of social problem-solving therapy and reminiscence therapy as treatments for depression in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61(6):1003–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arean P, Hegel M, Vannoy S, Fan MY, Unuzter J. Effectiveness of problem-solving therapy for older, primary care patients with depression: results from the IMPACT project. Gerontologist. 2008;48(3):311–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiosses DN, Leon AC, Arean PA. Psychosocial interventions for late-life major depression: evidence-based treatments, predictors of treatment outcomes, and moderators of treatment effects. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2011;34(2):377–401, viii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arean PA, Alvidrez J, Barrera A, Robinson GS, Hicks S. Would older medical patients use psychological services? Gerontologist. 2002;42(3):392–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gum AM, Iser L, Petkus A. Behavioral health service utilization and preferences of older adults receiving home-based aging services. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(6):491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raue PJ, Schulberg HC, Heo M, Klimstra S, Bruce ML. Patients’ depression treatment preferences and initiation, adherence, and outcome: a randomized primary care study. Psychiatric services. 2009;60(3):337–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey AG, Gumport NB. Evidence-based psychological treatments for mental disorders: modifiable barriers to access and possible solutions. Behaviour research and therapy. 2015;68:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman HH, Azrin ST. Public policy and evidence-based practice. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2003;26(4):899–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chambers DA. Advancing the science of implementation: a workshop summary. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2008;35(1–2):3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gehart D The core competencies and MFT education: practical aspects of transitioning to a learning-centered, outcome-based pedagogy. J Marital Fam Ther. 2011;37(3):344–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spruill J, Rozensky RH, Stigall TT, Vasquez M, Bingham RP, De Vaney Olvey C. Becoming a competent clinician: basic competencies in intervention. J Clin Psychol. 2004;60(7):741–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyon AR, Munson SA, Renn BN, Atkins DC, Pullmann MD, Friedman E, et al. Use of Human-Centered Design to Improve Implementation of Evidence-Based Psychotherapies in Low-Resource Communities: Protocol for Studies Applying a Framework to Assess Usability JMIR Res Protoc. 2019;8(10):e14990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexopoulos GS, Arean P. A model for streamlining psychotherapy in the RDoC era: the example of ‘Engage’. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(1):14–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crabb RM, Areán PA, Hegel MT. Sustained adoption of an evidence-based treatment: a survey of clinicians certified in problem-solving therapy. Depress Res Treat. 2012;2012:986547–986547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russo SJ, Nestler EJ. The brain reward circuitry in mood disorders. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2013;14(9):609–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rupprechter S, Stankevicius A, Huys QJM, Series P, Steele JD. Abnormal reward valuation and event-related connectivity in unmedicated major depressive disorder. Psychol Med. 2020:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma A, Wolf D, Ciric R, Kable J, Moore T, Vandekar S, et al. Common Dimensional Reward Deficits Across Mood and Psychotic Disorders: A Connectome-Wide Association Study. The American journal of psychiatry. 2017;174:657–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rupprechter S, Stankevicius A, Huys QJM, Steele JD, Series P. Major Depression Impairs the Use of Reward Values for Decision-Making. Scientific reports. 2018;8(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eppinger B, Hammerer D, Li SC. Neuromodulation of reward-based learning and decision making in human aging. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;1235:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dombrovski AY, Siegle GJ, Szanto K, Clark L, Reynolds CF, Aizenstein H. The temptation of suicide: striatal gray matter, discounting of delayed rewards, and suicide attempts in late-life depression. Psychological medicine. 2012;42(6):1203–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck AT. The evolution of the cognitive model of depression and its neurobiological correlates. The American journal of psychiatry. 2008;165(8):969–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dai B, Li J, Chen T, Li Q. Interpretive bias of ambiguous facial expressions in older adults with depressive symptoms. PsyCh journal. 2015;4(1):28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams LM, Gatt JM, Schofield PR, Olivieri G, Peduto A, Gordon E. ‘Negativity bias’ in risk for depression and anxiety: brain-body fear circuitry correlates, 5-HTT-LPR and early life stress. NeuroImage. 2009;47(3):804–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dai Q, Wei J, Shu X, Feng Z. Negativity bias for sad faces in depression: An event-related potential study. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2016;127(12):3552–3560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexopoulos GS, Raue PJ, Kiosses DN, Seirup JK, Banerjee S, Arean PA. Comparing engage with PST in late-life major depression: a preliminary report. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(5):506–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maier S, Szalkowski A, Kamphausen S, Perlov E, Feige B, Blechert J, et al. Clarifying the Role of the Rostral dmPFC/dACC in Fear/Anxiety: Learning, Appraisal or Expression? PloS one. 2012;7(11):e50120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alexopoulos GS, Raue PJ, Kiosses DN, Mackin RS, Kanellopoulos D, McCulloch C, et al. Problem-solving therapy and supportive therapy in older adults with major depression and executive dysfunction: effect on disability. Archives of general psychiatry. 2011;68(1):33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hegel MT, Barrett JE, Oxman TE. Training therapists in problem-solving treatment of depressive disorders in primary care: Lessons learned from the “Treatment Effectiveness Project”. Families, Systems, & Health. 2000;18(4):423–435. [Google Scholar]

- 34.First MB, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV - patient version (SCID-P). Washington: American Psychiatric Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 1979;134:382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakonezny PA, Carmody TJ, Morris DW, Kurian BT, Trivedi MH. Psychometric evaluation of the Snaith-Hamilton pleasure scale in adult outpatients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(6):328–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: The Hopelessness Scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1974;42(6):861–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marin RS, Biedrzycki RC, Firinciogullari S. Reliability and validity of the Apathy Evaluation Scale. Psychiatry research. 1991;38(2):143–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanter JW, Mulick PS, Busch AM, Berlin KS, Martell CR. The Behavioral Activation for Depression Scale (BADS): Psychometric properties and factor structure. J Psychopathol Behav. 2007;29(3):191–202. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Costa PT, McCrae RR. Neo personality inventory-revised (NEO PI-R). Psychological Assessment Resources. 1992;396. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Epping-Jordan JA, Ustun TB. The WHODAS-II: leveling the playing field for all disorders. WHO Mental Health Bulletin. 2000;6:5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamilton M A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riordan Henry J AR. Methods to Reduce Placebo Response in Antidepressant Treatment Trials. Journal for Clinical Studies 2018;10(4):46–49. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lecrubier Y How do you define remission? Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplementum. 2002(415):7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laird N, Ware J. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38:963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roderick JA Little DBR. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2nd Edition ed. Hoboken NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee P, Shu L, Xu X, Wang CY, Lee MS, Liu CY, et al. Once-daily duloxetine 60 mg in the treatment of major depressive disorder: multicenter, double-blind, randomized, paroxetine-controlled, non-inferiority trial in China, Korea, Taiwan and Brazil. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2007;61(3):295–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitchell C, Dwyer R, Hagan T, Mathers N. Impact of the QOF and the NICE guideline in the diagnosis and management of depression: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61(586):e279–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barlow DH, Farchione TJ, Bullis JR, Gallagher MW, Murray-Latin H, Sauer-Zavala S, et al. The Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders Compared With Diagnosis-Specific Protocols for Anxiety Disorders: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(9):875–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dias A, Azariah F, Anderson SJ, Sequeira M, Cohen A, Morse JQ, et al. Effect of a Lay Counselor Intervention on Prevention of Major Depression in Older Adults Living in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(1):13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dombrovski AY, Mulsant BH, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Lenze EJ, Andreescu C, et al. Residual symptoms and recurrence during maintenance treatment of late-life depression. Journal of affective disorders. 2007;103(1–3):77–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kiosses DN, Alexopoulos GS. The prognostic significance of subsyndromal symptoms emerging after remission of late-life depression. Psychol Med. 2013;43(2):341–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deng Y, McQuoid DR, Potter GG, Steffens DC, Albert K, Riddle M, et al. Predictors of recurrence in remitted late-life depression. Depression and anxiety. 2018;35(7):658–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.