Abstract

Introduction:

The Autoimmunity Screening for Kids (ASK) study is a large scale pediatric screening study in Colorado for celiac disease (CD) and type 1 diabetes. This is a report of the CD outcomes for the first 9,973 children screened through ASK.

Methods:

ASK screens children aged 1–17 years for CD using two highly sensitive assays for transglutaminase autoantibodies (TGA): a radiobinding (RBA) assay for IgA TGA and an electrochemiluminescence (ECL) assay that detects all TGA isotypes. Children who test positive on either assay are asked to return for confirmatory testing. Those with a confirmed RBA TGA level ≥ 0.1 (twice the upper limit of normal) are referred to the Colorado Center for Celiac Disease for further evaluation, all others are referred to primary care.

Results:

Of the initial 9,973 children screened, 242 children were TGA+ by any assay. Of those initially positive, 185 children (76.4%) have completed a confirmation blood draw with 149 children (80.5%) confirming positive by RBA TGA. Confirmed RBA TGA+ was associated with family history of celiac disease (OR=1.83; 95%CI 1.06–3.16), non-Hispanic white ethnicity (OR=3.34; 2.32–4.79), and female sex (OR=1.43; 1.03–1.98). Gastrointestinal symptoms of CD, assessed at the initial screening, were reported equally often among the RBA TGA+ vs. TGA- children (32.1% vs. 30.5%, p=0.65).

Conclusions:

The initial results of this ongoing mass-screening program confirm a high prevalence of undiagnosed CD autoimmunity in a screened US population. Symptoms at initial screening were not associated with TGA status.

Keywords: screening, celiac disease, type 1 diabetes, autoimmunity

Introduction:

Celiac disease (CD) is a common gluten-mediated autoimmune enteropathy estimated to affect up to 2–3% of the adolescent population in Colorado.[1,2] Current guidelines recommend screening for celiac disease with tissue transglutaminase autoantibody (TGA) testing in symptomatic individuals and asymptomatic individuals with high risk features based on a family history of CD, concurrent autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes, and particular genetic syndromes.[3] While classic gastrointestinal symptoms and signs such as diarrhea, abdominal distension, vomiting, and malabsorption commonly prompt evaluation for CD, the non-classic and subclinical presentations are often overlooked. [4–7] In fact, over half of individuals may be asymptomatic at presentation and, therefore, may not be identified by the current recommendations for serologic screening.[8,9] Specifically, in an international prospective cohort study of children at genetic risk for celiac disease -The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study - the presence of symptoms was a poor predictor of celiac disease autoimmunity. [10]

The difficulty of identifying cases based on the presence of symptoms contributes to diagnostic delay that may be over ten years on average.[11] This diagnostic delay has a negative impact on both the patient’s overall health and healthcare utilization.[12] Untreated celiac disease may lead to significant morbidity including osteoporosis[13], growth stunting[14], infertility[15], neuropathy[16], and gastrointestinal lymphomas.[17,18]

While celiac disease meets many of the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for a chronic disease that should be considered for universal screening, screening for celiac disease in asymptomatic persons remains controversial.[19] While treating individuals with symptomatic celiac disease has clear benefit, the natural history of asymptomatic, screening-detected celiac disease with respect to its associated morbidities remains largely unknown. Limited studies have suggested that untreated asymptomatic celiac disease autoimmunity may negatively affect growth and bone health.[20, 21] However, the risk of morbidity must also be balanced with the cost of screening and the social and economic burden of a gluten-free diet.

While general pediatric population screening studies have been reported from Europe, to our knowledge, the Autoimmunity Screening for Kids (ASK) is the first large scale pediatric screening study in the United States.[22–27] ASK screens children simultaneously for celiac disease and type 1 diabetes. The overall objective of the ASK program is to raise awareness of the importance of type 1 diabetes and celiac disease in the community, and to reduce the morbidity of delayed diagnosis associated with these conditions. It will also assess the harms and benefits of a mass screening approach. Here we report the study design and preliminary screening results for celiac disease in the initial 9,973 children screened between January 2017 and July 2018. The screening results for type 1 diabetes will be reported separately.

Methods:

Study Participants:

The protocol was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and includes children ages 1–17 years who live in Colorado. Between January 2017 and July 2018, families at private pediatric practices, community clinics, urgent cares, and the Children’s Hospital Colorado (CHCO) and its satellite locations were approached for participation in the study and the study was advertised both electronically and at community events. Eligible participants were screened for transglutaminase autoantibodies (TGA) to detect celiac disease autoimmunity and for islet autoantibodies (IA) to detect pre-symptomatic type 1 diabetes. Exclusion criteria included those who already carried a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes (children with type 1 diabetes in Colorado are routinely screened for celiac disease), celiac disease, and those who were not fluent in English or Spanish.

Initial Screening:

The initial screen consisted of a venipuncture or capillary draw at the selected sites. Parents were also asked to fill out basic demographic information, family history, and gluten-free diet information. Parents and children were asked to complete a symptom questionnaire together. Celiac disease symptoms were assessed over the past 3 months including diarrhea (defined as 3 or more stools per day), frequent stomach aches or being gassy or bloated, constipation (defined as less than 2 stools/week), vomiting (not associated with illness), difficulty gaining weight, and poor growth (this was assessed over the past 2 years). This symptom questionnaire was administered before the children or parents were aware of autoantibody status. Results of the blood draw were shared with families within approximately 4 weeks. Children who initially screen negative are offered annual free repeat screening. Parents were also given the option of having the study staff share the research results with the child’s primary care physician.

Confirmation Testing:

Children that initially screened positive for TGA or IA were invited back to the Barbara Davis Center for Diabetes (BDC) for a confirmation visit (Supplementary Figure 1). A venous blood draw was collected to confirm positive results. Weight and height were also recorded. Parents and children were asked to fill out a more extended celiac disease symptom questionnaire (Supplementary Table 1). Those who confirmed positive with a TGA radiobinding assay (RBA) result ≥2 times the upper limit of normal were referred to the Children’s Hospital Colorado Center for Celiac Disease (CCCD) for clinical evaluation. Children with a low positive RBA result (<2 times the upper limit of normal) were referred back to their primary care physician. Not all TGA positive children were seen at the CCCD. For those that were not, the research team contacted each family for additional information regarding the outcomes specifically about whether the child has been assessed by a gastroenterologist, whether they have undergone an intestinal biopsy, and whether they have adapted a gluten-free diet.

Tissue Transglutaminase Autoantibody Assays:

Two highly sensitive assays were used for screening and confirmation testing in all participants. The radiobinding assay (RBA) detects the TGA IgA isotype only and has been previously extensively published. [28, 29] The primary outcome of the ASK study is persistent celiac autoimmunity defined as positivity on two consecutive blood draws for RBA TGA at the cutoff value of 0.05 or greater. Higher antibody levels particularly above ten times the upper limit of normal have been tied to an increased risk of enteropathy.

The electrochemiluminescence assay (ECL) is unique in its ability to detect autoantibodies of the IgA, IgG, IgD, IgE and IgM isotypes [30,31] and may be helpful in individuals with selective IgA deficiency, those on a low-gluten containing diet, and those positive for TGA IgM only due to a very recent seroconversion. To fully assess the clinical utility of the ECL TGA assay, ASK continues to follow study participants positive only by this assay. However, for the purpose of this report ‘confirmed TGA’ was defined as the presence of either ECL TGA or RBA TGA at screening and the presence of RBA TGA at the confirmation visit. Total IgA level was not measured.

Study Outcomes:

The primary outcome of this study is confirmed RBA TGA. The decision to proceed to endoscopic evaluation occurred after clinical referral and was outside of the study protocol. Secondary outcomes include biopsy-proven celiac disease (Marsh 2 or greater), potential celiac disease (positive serology and biopsy with Marsh score <2), a serologic diagnosis of celiac disease compatible with ESPGHAN criteria[32], persistent autoimmunity being followed on a gluten-containing diet, repeat negative serologic evaluation on a gluten-containing diet at follow up, and empiric placement on a gluten-free diet by family or pediatrician without diagnostic confirmation.

Statistical Analysis:

Demographic characteristics of children participating in the screening are presented according to their TGA status as means (± SD) for continuous variables or percentages (%) for categorical variables; they were compared using Student t-test or χ2 test or Fisher exact test, respectively. Independent associations between the presence of TGA and age, sex, race/ethnicity or having a first degree relative with CD were evaluated by multiple logistic regression. Firth logistic regression was used to reduce the bias of binary logistic regression in the analysis of rare events by using a penalized maximum likelihood estimation. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were evaluated. The statistical significance level was defined as p<0.05. Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

Results:

Initial Screen:

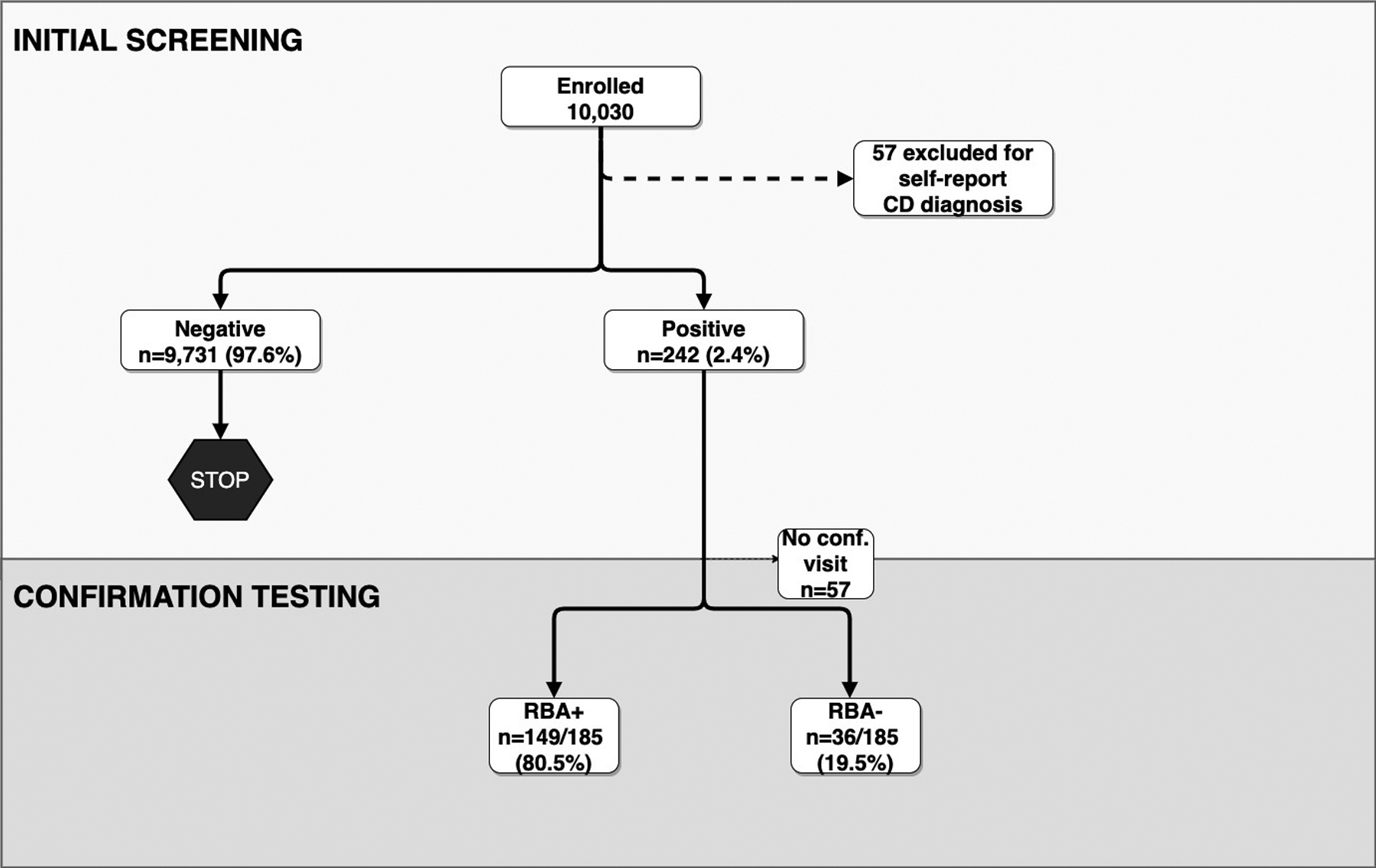

As of July 11, 2018, 9,973 children were screened for celiac autoantibodies. Family history of celiac disease in a first-degree relative was reported in 3.8% of all screened. Overall, 242 children (2.4%) tested TGA+ at the initial screening (Figure 1). Of these, 183 (75.6%) were positive by both the RBA and ECL assays, 4 (1.7%) were positive by RBA only, and 55 (22.7%) children screened positive by ECL only. Demographic characteristics of the study participants by the outcome of their initial screening are shown in Table 1. Among the screening-detected cases, 9.9% (24/242) had a first-degree relative with celiac disease and 11.1% (27/242) had a first-degree relative with type 1 diabetes, compared to, respectively, 3.7% and 4.8% in children who tested negative for TGA. Of the TGA positive children, 15/242 (6.2%) were positive for both TGA and islet autoantibodies. As of 3/5/2020, 505 children have been re-screened and 6 initially TGA negative children have become TGA positive.

Figure 1: Screening and confirmation results for transglutaminase autoantibodies (TGA).

(Conf, confirmation; ECL, Electrochemiluminescence Assay; RBA, Radiobinding Assay; TGA, tissue transglutaminase)

Table 1:

Characteristics of study population by TGA status at the initial screening test only

| TGA Positive | TGA Negative (n=9,731) | Total (n=9,973) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBA only (n=4) | ECL only (n=55) | RBA and ECL (n=183) | |||

| Age, y Mean (SD) | 8.9 (1.6) | 9.3 (4.4) | 10.3 (3.9) | 9.3 (4.4) | |

| < 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 203 (2.1) | 203 (2.0) |

| 2–5 | 0 | 15 (27.3) | 30 (16.4) | 2530 (26) | 2575 (25.8) |

| 6–9 | 2 (50.0) | 16 (29.1) | 58 (31.7) | 2665 (27.4) | 2741 (27.5) |

| 10–13 | 2 (50.0) | 16 (29.1) | 65 (35.5) | 2571 (26.4) | 2654 (26.6) |

| 14–17 | 0 | 8 (14.6) | 30 (16.4) | 1762 (18.1) | 1800 (18.0) |

| Sex, Male | 2 (50.0) | 28 (50.9) | 77 (42.1) | 4853 (49.9) | 4960(49.7) |

| First-degree relative of a patient with celiac disease | 0 | 7 (12.7) | 17 (9.3) | 356 (3.7) | 380 (3.8) |

| First-degree relative of a patient with type 1 diabetes | 0 | 9 (16.4) | 18 (9.8) | 467 (4.8) | 494 (5.0) |

| Islet Autoimmunity | 0 | 4 (7.2) | 11 (6.0) | 333 (3.4) | 348 (3.5) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2 (50.0) | 32 (58.2) | 119 (65) | 3338 (34.3) | 3491 (35.0) |

| Hispanic | 2 (50.0) | 16 (29.1) | 55 (30.1) | 5068 (52.1) | 5141 (51.6) |

| African American | 0 | 3 (5.5) | 2 (1.1) | 772 (7.9) | 777 (7.8) |

| Other race | 0 | 4 (7.3) | 7 (3.8) | 553 (5.7) | 564 (5.7) |

(TGA, tissue transglutaminase; RBA, radiobinding assay; ECL electrochemiluminescence assay; CD, celiac disease; SD, standard deviation; T1D, type 1 diabetes; y, years old).

The columns denote the number of subjects (%), unless otherwise noted.

At the initial screening, 60 RBA TGA+ subjects (32.1%) reported one or more symptoms of celiac disease. This was not different from the participants who screened negative as 2,970 subjects or 30.5% reported one or more celiac symptoms (p-value 0.65). Symptom prevalence at the initial screen is outlined in Table 2. Vomiting was the only symptom found to be distributed differently among the RBA TGA+ and TGA negative groups with a respective frequency of 6.4% versus 3.6% (p-value 0.04). The presence of two or more symptoms was more common in the TGA+ group compared to the TGA negative group with a respective frequency of 18.7% versus 13.7%, although not statistically significant (p-value 0.05). Other assessed individual symptoms including weight loss, poor growth, constipation, stomach aches, and diarrhea were not different between groups. There was also no association between the age at the time of the initial screening and the presence of symptoms at the initial screen (p-value 0.12).

Table 2:

Prevalence of symptoms at the initial screening according to transglutaminase autoantibody (TGA) status

| TGA | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | RBA + n=187 n (%) |

NegativeA n=9,731 n ( %) |

P-value |

| Weight Loss | 6 (3.2%) | 334 (3.4%) | 0.87 |

| Vomiting | 12 (6.4%) | 347 (3.6%) | 0.04 |

| Poor Growth | 10 (5.4%) | 455 (4.7%) | 0.66 |

| Stomach Aches | 50 (26.7%) | 2142 (22.0%) | 0.12 |

| Diarrhea | 11 (5.9%) | 454 (4.7%) | 0.44 |

| Constipation | 22 (11.8%) | 1158 (11.9%) | 0.95 |

| Any of the above | 60 (32.1%) | 2,970 (30.5%) | 0.65 |

| Two or more symptoms | 35 (18.7%) | 1329 (13.7%) | 0.05 |

(TGA, tissue transglutaminase; RBA, radiobinding assay)

This analysis excluded the 55 ECL positive only participants.

Confirmation Testing:

Of the 242 initially TGA+ children, 185 (76.4%) returned for a confirmation blood draw (Figure 1). The children who did not return for a confirmation visit did not differ with respect to demographic characteristics compared to those who did complete the confirmation visit (Supplementary Table 2). Of those who completed the confirmation visit, thus far, 80.5% (149/185 children) were confirmed RBA TGA+, 10.8% (20/185 children) continued to be only ECL TGA+ and 8.6% (16/185 children) were TGA negative by both assays. Therefore, 149 children met the outcome of persistent autoimmunity, but this does not account for children who have not yet returned for their confirmation visit.

Of the 55 children who were initially TGA+ only by ECL, 42 returned for confirmation testing. Twelve of these participants subsequently confirmed positive by RBA and were included in the primary outcome. Twenty children remained positive on ECL only and 10 children were subsequently negative by both RBA and ECL testing.

Per study protocol, 41 participants who had lower-level confirmed RBA TGA+ (less than two times the upper limit of normal) were referred to their primary care health providers. The remaining 108 children with higher-level confirmed RBA TGA+ were referred to the CCCD.

Characteristics associated with presence of confirmed RBA TGA+:

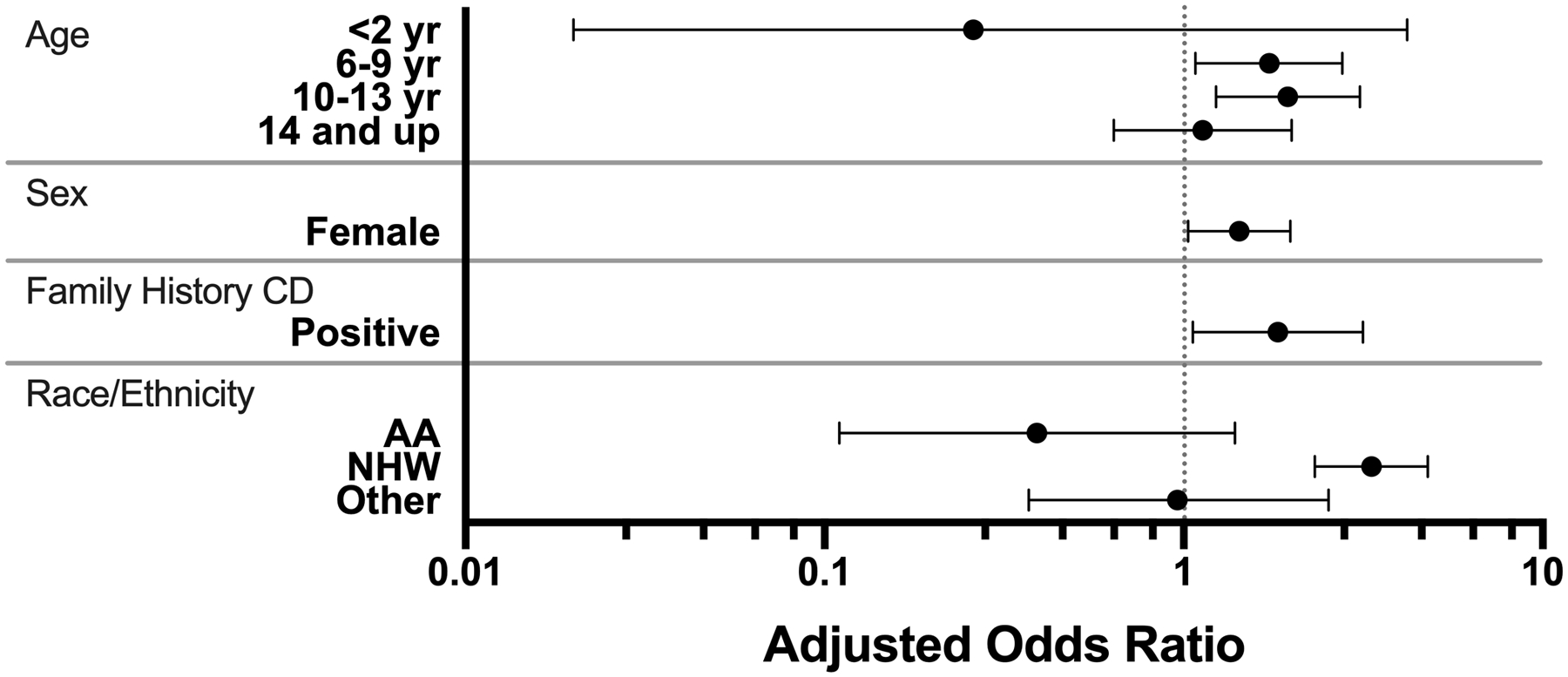

Independent associations between the presence of confirmed RBA TGA+ and age, sex, race/ethnicity or having a first degree relative with CD were assessed in multiple logistic regression models (Figure 2 and Table 3). The prevalence of confirmed RBA TGA+ was clearly higher in non-Hispanic white compared to Hispanic children (2.9% vs 0.8%). The association with ethnicity was significant (OR=3.34; 2.32–4.79) and independent of age, sex, and family history of celiac disease. Presence of celiac disease in a first-degree relative (OR=1.83; 1.06–3.16) and female sex (OR=1.43; 1.03–1.98) were also independently associated with confirmed RBA TGA+. Interestingly, children 6–13 years old were nearly twice as likely to express RBA TGA+ than younger children or older teenagers. These associations held true when limiting cases to those with a RBA TGA over ten times the upper limit of normal (data not shown).

Figure 2: Association of confirmed radiobinding assay (RBA) tissue transglutaminase (TGA) + cases with demographic characteristics by logistic regression model.

(AA, African American, NHW, Non-Hispanic White)

A Model adjusted for age, sex, family history of celiac disease, and self-reported ethnicity and race. Odds ratio compare those who confirm positive by RBA to those who initially screened negative.

B Reference groups included 2–5 yrs for age, male for sex, no family history of celiac disease, and Hispanic for race/ethnicity.

Table 3:

Association of confirmed RBA TGA+ status with age, sex, family history of celiac disease, and race/ethnicity, N=9,973

| Category | N of screened | N of confirmed cases | Prevalence, % (95% CI) | Unadjusted | Adjusted for the other variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |||||

| Age | <2 | 203 | 0 | 0 | 0.23 (0.01–3.77) | 0.30 | 0.26 (0.02–4.19) | 0.34 |

| 2–5 (ref) | 2575 | 27 | 1.05 (0.69–1.52) | |||||

| 6–9 | 2741 | 48 | 1.75 (1.29–2.32) | 1.67 (1.04–2.67) | 0.03 | 1.73 (1.08–2.77) | 0.02 | |

| 10–13 | 2654 | 53 | 2.00 (1.50–2.60) | 1.91 (1.20–3.03) | 0.006 | 1.95 (1.23–3.10) | 0.005 | |

| 14–17 | 1800 | 21 | 1.17 (0.72–1.78) | 0.12 (0.64–1.98) | 0.70 | 1.13 (0.64–2.00) | 0.67 | |

| Sex | M (ref) | 4960 | 62 | 1.25 (0.96–1.60) | ||||

| F | 5012 | 87 | 1.74 (1.39–2.14) | 1.40 (1.01–1.94) | 0.05 | 1.43 (1.03–1.98) | 0.03 | |

| First-degree relative of a patient with celiac disease | No (ref) | 9593 | 134 | 1.40 (1.17–1.65) | ||||

| Yes | 380 | 15 | 3.95 (2.23–6.43) | 2.90 (1.68–5.00) | 0.0001 | 1.83 (1.06–3.16) | 0.03 | |

| Race/ Ethnicity | Hispanic (ref) | 5141 | 43 | 0.84 (0.61–1.13) | ||||

| African American | 777 | 2 | 0.26 (0.03–0.93) | 0.31 (0.07–1.27) | 0.10 | 0.39 (0.11–1.39) | 0.15 | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 3491 | 100 | 2.86 (2.34–3.47) | 3.50 (2.44–5.01) | <.0001 | 3.34 (2.32–4.79) | <.0001 | |

| Other race | 564 | 4 | 0.71 (0.19–1.81) | 0.85 (0.30–2.37) | 0.75 | 0.96 (0.37–2.53) | 0.94 | |

(CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio)

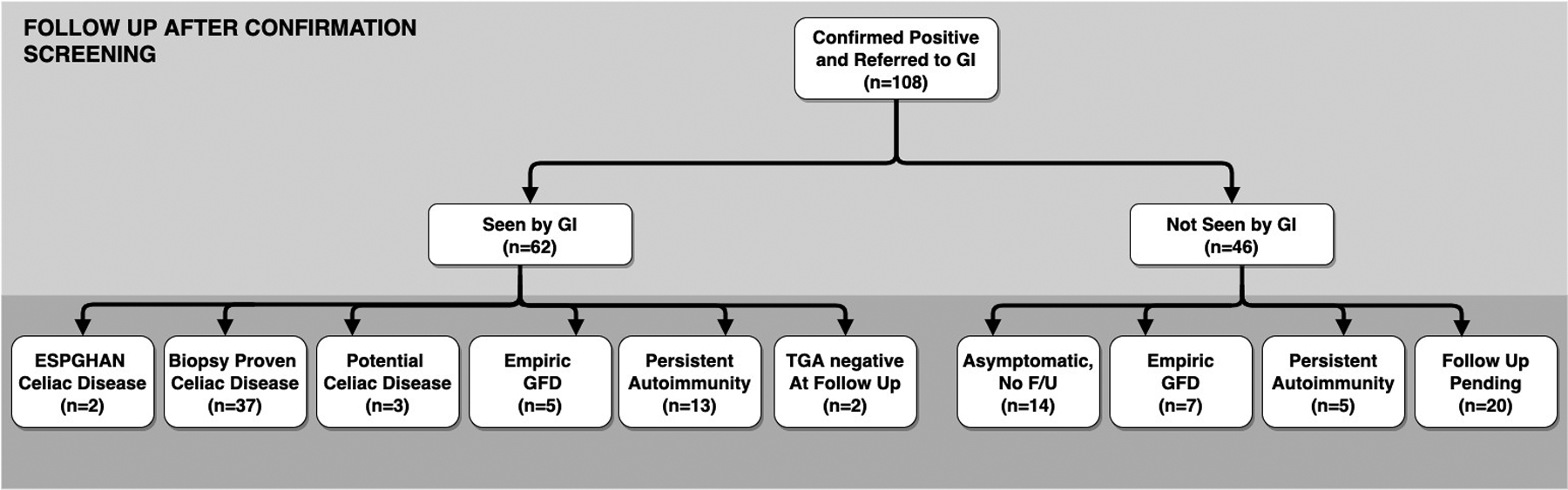

Follow-up of confirmed positive children:

Of the 108 confirmed RBA TGA + children referred for follow up, 62 were seen by a gastroenterologist. The decision to follow up with a gastroenterologist was associated with the presence of symptoms at their confirmation screen and RBA TGA value. Of note, 80% of children who followed up with a gastroenterologist had symptoms at their confirmation screen, while only 61% of children who did not follow up with a gastroenterologist had symptoms at their confirmation screen (p-value 0.039). Mean RBA TGA value was higher among those seen by gastroenterology; those seen by a gastroenterologist had a mean TGA of 0.56 and those who were not seen by a gastroenterologist had a mean TGA of 0.41 (p-value 0.013).

Thirty seven children have biopsy-proven celiac disease (Marsh 2 or greater), 3 children have potential celiac disease (positive serology and biopsy with Marsh score <2), 2 children have a serologic diagnosis of celiac disease compatible with ESPGHAN criteria, 18 children have persistent autoimmunity and are being followed on a gluten-containing diet, 2 children had negative serologic testing on a gluten-containing diet (not detected at a clinical visit), and 12 children were empirically placed on a gluten-free diet by their family or pediatrician without diagnostic confirmation. (Figure 3) Fourteen children have opted not to follow up clinically for these results as they remain asymptomatic. These represent the preliminary results of the follow up of confirmed positive children and efforts are being made to determine the outcomes of the remaining confirmed positive children who have not yet followed up.

Figure 3: Outcomes of participants referred for further evaluation.

(EMA, endomysial autoantibody; F/U, follow up; GI, gastroenterology; GFD, gluten-free diet)

European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) diagnosis requires high positive TGA and positive EMA per the 2020 guidelines.

Biopsy proven celiac disease refers to Marsh 2 or greater.

Potential celiac disese refers to positive TGA with Marsh 1 or lower.

Empiric GFD refers to children placed on a GFD before diagnostic confirmation of celiac disease.

Persistent autoimmunity refers to children with positive TGA and being followed on a gluten containing diet.

TGA negative at follow up refers to children who had a negative serologic evaluation at their follow up assessment.

Asymptomatic and no follow up refers to children reported to still have no symptoms and, therefore, have not returned for further assessment.

Discussion:

The ASK study is performing large scale screening for pediatric celiac disease in Colorado and this is a report of the initial screening results for the first 9,973 children. While previous screening studies using epidemiologic cohorts, school children, military personnel, blood donors, and health fair attendees have framed celiac disease as common in the United States,[7,33–35] the ASK study is the first mass pediatric screening effort of this size for celiac disease in the United States that will be prospectively following the outcomes of children who screen positive. There is a high prevalence of TGA positivity (2.4%) at the initial screening visit. With an 80% positive confirmation rate using the ‘gold standard’ RBA assay, we estimate that at least 1.9% of all screened Colorado children have undiagnosed persistent TGA positivity. This number is not necessarily representative of the Colorado general population since the ASK screened population was enriched with Hispanic children, representing 51.6% of all screened, compared to 21.7% of the Colorado population. These demographic characteristics do affect celiac disease autoimmunity risk; 2.9% of non-Hispanic white children have confirmed TGA positivity, while only 0.8% of Hispanic children were positive. The increased prevalence among non-Hispanic white children corroborates previous reports of ethnic differences in the risk of celiac disease, which may be due to a combination of genetic, environmental, and socioeconomic factors.[36,37] For example, Hispanic children more commonly carry the lower risk HLA-DQ8 compared to non-Hispanic whites who more commonly carry higher risk HLA-DQ2 alleles.[2,38]

In our study, the presence of symptoms generally did not differ between children who screened positive versus those who screened negative at initial testing. In fact, 2/3 of children RBA TGA positive on their initial screening reported no GI symptoms. Of note, even those with the highest TGA levels by RBA and most likely to have CD [32,39] (greater than ten times the upper limit of normal) were as likely to report symptoms (16/57, 28.1%) as those who were TGA negative (2970/9731, 30.5%, p-value 0.69). These findings are consistent with a previously reported Finnish targeted screening study of at-risk children.[40] Finally, most TGA positive children (90%) identified through ASK do not have a first-degree relative with CD. Therefore, screening based only on risk factors such as symptoms or family history will miss the majority of cases.

These are the initial findings of mass screening for pediatric celiac disease in a US population. ASK remains uniquely poised in follow-up studies to address several concerns raised by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) statement regarding mass screening for celiac disease in asymptomatic individuals. Further follow up of children diagnosed with CD through ASK - children who were not recognized as symptomatic by their families or healthcare providers, will allow us to study the potential benefits and harms of mass screening. The potential medical benefits of treating screening-identified celiac disease and earlier diagnosis must be balanced with the potential psychosocial and economic burdens of screening-identified celiac disease. Follow up at the Colorado Center for Celiac Disease assesses symptoms, lab abnormalities, growth parameters, quality of life, anxiety, and depression to evaluate for these benefits and burdens.

Diagnosing celiac disease through screening may reduce the healthcare utilization and the cost of unrecognized celiac disease[12,41] particularly with respect to prescription medication use, primary health care visits, and missed days of school. However, screening also increases costs to the healthcare system particularly in the case of false positive tests, negative biopsies, and close monitoring of asymptomatic individuals who opt to remain on a gluten containing diet. Regarding mass screening for type 1 diabetes through ASK, it could be cost effective given a certain baseline prevalence of diabetic ketoacidosis and a preexisting infrastructure for screening.[42] While the outcomes of interest may vary between type 1 diabetes and celiac disease, similar methods may be applied to study the cost effectiveness of screening for celiac disease in the future.

Limitations and Strengths:

Total IgA level is not measured in ASK participants, therefore individuals with IgA deficiency may have tested false negative on the RBA TGA assay. IgA deficiency remains rare in the healthy population (around 0.4%) and is only slightly higher in the celiac disease population - around 1.9%.[43] On the other hand, most of the children with selective IgA deficiency and celiac disease would be picked up by the ECL TGA assay. ASK is planning a substudy to determine in-depth characterization of the immunoglobulin isotypes in children with persistent TGA detectable only by the ECL assay.

Another reason for potential missed cases involve the 1.3% of participating children already on a gluten-free diet at the time of screening; these factors would lead to an underestimation of the true prevalence of undiagnosed pediatric celiac disease autoimmunity in this screened US population.

The follow-up of TGA+ screening-detected cases is ongoing and the full spectrum of clinical outcomes in this population will not be known for several years. While nearly 20% of the screening-detected TGA+ cases have not yet completed the confirmation visit, their demographic characteristics were not different from those of children who completed confirmation testing. The study has limited resources to offer full clinical evaluation of screening-detected cases, including intestinal biopsy and treatment. While most of the children complete the clinical evaluation at the CCCD, some may follow up with private gastroenterologists due to health insurance restrictions, location, or parental preference. The study team is contacting all subjects not seen at the CCCD in an effort to determine their outcomes and to encourage follow-up if not seen elsewhere. However, as already noted, there are 12 children who elect to self-treat with a gluten-free diet without proper diagnosis of celiac disease and without consultation with a dietitian. The potential for lack of proper follow-up in TGA positive children remains a limitation and also has ethical considerations.

The strengths of this report include the size of the study population and robust representation of major racial/ethnic groups. To our knowledge, it is currently the only pediatric mass celiac disease screening effort in a general population in the United States. The initial symptom questionnaire was administered prior to the subject’s knowledge of their screening results limiting recall bias and making the symptoms reported more representative of what would be noted in the primary care setting. Subsequently, the initial symptoms reported may be an indication of who would be screened in the primary care setting under current USPSTF recommendations and who may be missed.

Conclusions:

ASK aims for the eventual implementation of a mass autoimmune screening program that would be feasible in the primary care setting. In this initial report, we find a high prevalence of undiagnosed celiac disease autoimmunity in a screened US population. Most screening-identified children do not have a family history of celiac disease (~90% without) or symptoms (~70% without) at the time of screening. Universal screening appears to be the only way to detect all cases of celiac disease and has the potential to reduce diagnostic delay and associated morbidity. A longer follow-up period is needed to properly assess the costs of screening and the effect on morbidity and quality of life of screening-identified children and families.[44–47]

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Autoimmunity Screening for Kids (ASK) study design (BDC, Barbara Davis Center for Diabetes,CCCD, Colorado Center for Celiac Disease, ECL,Electrochemiluminescence Assay, PCP, Primary Care Physician, RBA, Radiobinding Assay)

Supplementary Table 1: Comparison of symptom questionnaires at the initial screen to the confirmation screen

Supplementary Table 2: Comparison of characteristics of screening-positive children who did or did not complete the confirmation visit. (ECL, electrochemiluminescence assay; RBA, radiobinding assay; CD, celiac disease)

* One subject who was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes prior to returning for a confirmation visit was excluded.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS KNOWN

Celiac disease is common and most children remain undiagnosed.

Universal screening remains controversial due to limited evidence on associated morbidity and cost of screening.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

This study confirms a high prevalence of undiagnosed celiac disease autoimmunity in a population screened in the US.

Despite the current USPSTF recommendation for symptom-based autoantibody screening, ASK supports previous findings that symptoms were not predictive of a positive celiac autoantibody screen.

Most children who screened positive for celiac disease in this mass screening program did not have a family history of celiac disease

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

The ASK Study Group (See appendix)

The ASK Study is funded by JDRF International, The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, and Janssen Research and Development, LLC.

Grant Support: ASK is funded by grant 3-SRA-2018-564-M-N from JDRF International, The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, and Janssen Research and Development, LLC. Dr. Stahl is supported by the NIH training T32DK067009 grant and the SSCD-Beyond Celiac Early Career grant.

Abbreviations:

- ASK

Autoimmunity Screening for Kids Study

- BDC

Barbara Davis Center for Diabetes

- CCCD

Children’s Hospital Colorado Center for Celiac Disease

- ECL

Electrochemiluminescence assay

- HLA

Human Leukocyte Antigen

- IA

Islet autoantibodies

- RBA

Radiobinding Assay

- TGA

Tissue transglutaminase autoantibody

- TEDDY

The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young Study

- USPSTF

US Preventive Services Task Force

- WHO

World Health Organization

Appendix

The ASK Study Group

Marian Rewers, MD, PhD, PI, Aaron Barbour, BS, Kimberly Bautista, BS, Judith Baxter, MPH, Fran Dong, MS, Paul Dormond-Brooks, BS, Kimberly Driscoll, PhD, Daniel Felipe-Morales, BS, Brigitte Frohnert, MD, Patricia Gesualdo, RN, MSPH, Yong Gu, MD, PhD, Michelle Hoffman, RN, Rachel Karban, MPH, Flor Sepulveda, BS, Hanan Shorrosh, BS, Kimberly Simmons, MD, Andrea Steck, MD, Iman Taki, BS, Kathleen Waugh, MS, Liping Yu, MD, Barbara Davis Center for Diabetes, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus

Edwin Liu, MD, and Marisa Stahl, MD, Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, CO, United States

R. Brett McQueen, PhD, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Aurora, CO, United States

Jill Norris, PhD, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Colorado School of Public Health, Aurora, CO, United States

Project scientist: Jessica Dunne, PhD, JDRF International

Other contributors: Joseph Hedrick, PhD, Richard Insel, MD, Anne Koralova, PhD, Jeff Krischer, PhD

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: E.L. serves as a consultant for Takeda Pharmaceuticals and IM Therapeutics. For all other authors, there are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

RESOURCES

- 1.Leonard MM, Sapone A, Catassi C, Fasano A. Celiac Disease and Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity: A Review. JAMA 2017;318(7):647–56 doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.9730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu E, Dong F, Baron AE, et al. High Incidence of Celiac Disease in a Long-term Study of Adolescents With Susceptibility Genotypes. Gastroenterology 2017;152(6):1329–36.e1 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill ID, Fasano A, Guandalini S, et al. NASPGHAN Clinical Report on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Gluten-related Disorders. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2016;63(1):156–65 doi: 10.1097/mpg.0000000000001216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ludvigsson JF, Leffler DA, Bai JC, et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut 2013;62(1):43–52 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Kalleveen MW, de Meij T, Plotz FB. Clinical spectrum of paediatric coeliac disease: a 10-year single-centre experience. Eur J Pediatr 2018;177(4):593–602 doi: 10.1007/s00431-018-3103-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fasano A, Catassi C. Coeliac disease in children. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2005;19(3):467–78 doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubio-Tapia A, Ludvigsson JF, Brantner TL, Murray JA, Everhart JE. The prevalence of celiac disease in the United States. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 2012;107(10):1538–44; doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rampertab SD, Pooran N, Brar P, Singh P, Green PH. Trends in the presentation of celiac disease. Am J Med 2006;119(4):355.e9–14 doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.08.044[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reilly NR, Fasano A, Green PH. Presentation of celiac disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2012;22(4):613–21 doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agardh D, Lee HS, Kurppa K, et al. Clinical features of celiac disease: a prospective birth cohort. Pediatrics 2015;135(4):627–34 doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3675[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green PHR, Stavropoulos SN, Panagi SG, et al. Characteristics of adult celiac disease in the USA: results of a national survey. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 2001;96(1):126–31 doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03462.x[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mattila E, Kurppa K, Ukkola A, et al. Burden of illness and use of health care services before and after celiac disease diagnosis in children. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2013;57(1):53–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Posthumus L, Al-Toma A. Duodenal histopathology and laboratory deficiencies related to bone metabolism in coeliac disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;29(8):897–903 doi: 10.1097/meg.0000000000000880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meazza C, Pagani S, Laarej K, et al. Short stature in children with coeliac disease. Pediatric endocrinology reviews : PER 2009;6(4):457–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casella G, Orfanotti G, Giacomantonio L, et al. Celiac disease and obstetrical-gynecological contribution. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 2016;9(4):241–49 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mearns ES, Taylor A, Thomas Craig KJ, et al. Neurological Manifestations of Neuropathy and Ataxia in Celiac Disease: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019;11(2) doi: 10.3390/nu11020380[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludvigsson JF, Lebwohl B, Rubio-Tapia A, et al. Does celiac disease influence survival in lymphoproliferative malignancy? Eur J Epidemiol 2013;28(6):475–83 doi: 10.1007/s10654-013-9789-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leslie LA, Lebwohl B, Neugut AI, Gregory Mears J, Bhagat G, Green PH. Incidence of lymphoproliferative disorders in patients with celiac disease. Am J Hematol 2012;87(8):754–9 doi: 10.1002/ajh.23237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou R, Blazina I, Bougatsos C, Mackey K, Grusing S, Selph S. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews. Screening for Celiac Disease: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jansen MA, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Gaillard R, et al. Growth trajectories and bone mineral density in anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody-positive children: the Generation R Study. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2015;13(5):913–20.e5 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simmons JH, Klingensmith GJ, McFann K, et al. Celiac autoimmunity in children with type 1 diabetes: a two-year follow-up. The Journal of Pediatrics 2011;158(2):276–81.e1 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maki M, Mustalahti K, Kokkonen J, et al. Prevalence of Celiac disease among children in Finland. N Engl J Med 2003;348(25):2517–24 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021687[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tommasini A, Not T, Kiren V, et al. Mass screening for coeliac disease using antihuman transglutaminase antibody assay. Arch Dis Child 2004;89(6):512–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korponay-Szabo IR, Szabados K, Pusztai J, et al. Population screening for coeliac disease in primary care by district nurses using a rapid antibody test: diagnostic accuracy and feasibility study. BMJ 2007;335(7632):1244–7 doi: 10.1136/bmj.39405.472975.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Koppen EJ, Schweizer JJ, Csizmadia CG, et al. Long-term health and quality-of-life consequences of mass screening for childhood celiac disease: a 10-year follow-up study. Pediatrics 2009;123(4):e582–8 doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mustalahti K, Catassi C, Reunanen A, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in Europe: results of a centralized, international mass screening project. Ann Med 2010;42(8):587–95 doi: 10.3109/07853890.2010.505931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gatti S, Lionetti E, Balanzoni L, et al. Increased Prevalence of Celiac Disease in School-age Children in Italy. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li M, Yu L, Tiberti C, et al. A report on the International Transglutaminase Autoantibody Workshop for Celiac Disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 2009;104(1):154–63 doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Candon S, Mauvais FX, Garnier-Lengline H, Chatenoud L, Schmitz J. Monitoring of anti-transglutaminase autoantibodies in pediatric celiac disease using a sensitive radiobinding assay. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2012;54(3):392–6 doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318232c459[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu L Islet Autoantibody Detection by Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) Assay. Methods Mol Biol 2016;1433:85–91 doi: 10.1007/7651_2015_296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao Z, Miao D, Michels A, et al. A multiplex assay combining insulin, GAD, IA-2 and transglutaminase autoantibodies to facilitate screening for pre-type 1 diabetes and celiac disease. J Immunol Methods 2016;430:28–32 doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2016.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabo I, et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for Diagnosing Coeliac Disease 2020. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2019. doi: 10.1097/mpg.0000000000002497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Catassi C, Kryszak D, Bhatti B, et al. Natural history of celiac disease autoimmunity in a USA cohort followed since 1974. Ann Med. 2010;42(7):530–538. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2010.514285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(3):286–292. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riddle MS, Murray JA, Porter CK. The incidence and risk of celiac disease in a healthy US adult population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(8):1248–1255. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jansen MAE, Beth SA, van den Heuvel D, et al. Ethnic differences in coeliac disease autoimmunity in childhood: the Generation R Study. Arch Dis Child 2017;102(6):529–34 doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mardini HE, Westgate P, Grigorian AY. Racial Differences in the Prevalence of Celiac Disease in the US Population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2009–2012. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 2015;60(6):1738–42 doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu E, et al. , Risk of pediatric celiac disease according to HLA haplotype and country. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2014. 371(1): p. 42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu E, Bao F, Barriga K, et al. Fluctuating transglutaminase autoantibodies are related to histologic features of celiac disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2003;1(5):356–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kivela L, Kaukinen K, Huhtala H, Lahdeaho ML, Maki M, Kurppa K. At-Risk Screened Children with Celiac Disease are Comparable in Disease Severity and Dietary Adherence to Those Found because of Clinical Suspicion: A Large Cohort Study. The Journal of Pediatrics 2017;183:115–21.e2 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.12.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mearns ES, Taylor A, Boulanger T, et al. Systematic Literature Review of the Economic Burden of Celiac Disease. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(1):45–61. doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0707-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McQueen RB, et al. , Cost and Cost-Effectiveness of Large-Scale Screening for Type 1 Diabetes in Colorado. Diabetes Care, 2020: p. dc192003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pallav K, Xu H, Leffler DA, Kabbani T, Kelly CP. Immunoglobulin A deficiency in celiac disease in the United States. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;31(1):133–7 doi: 10.1111/jgh.13176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kivela L, Popp A, Arvola T, Huhtala H, Kaukinen K, Kurppa K. Long-term health and treatment outcomes in adult coeliac disease patients diagnosed by screening in childhood. United European Gastroenterology 2018;6(7):1022–31 doi: 10.1177/2050640618778386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurppa K, Paavola A, Collin P, et al. Benefits of a gluten-free diet for asymptomatic patients with serologic markers of celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2014;147(3):610–17.e1 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.003[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahadev S, Gardner R, Lewis SK, Lebwohl B, Green PH. Quality of Life in Screen-detected Celiac Disease Patients in the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol 2016;50(5):393–7 doi: 10.1097/mcg.000000000000043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kinos S, Kurppa K, Ukkola A, et al. Burden of illness in screen-detected children with celiac disease and their families. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2012;55(4):412–6 doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31825f18ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Autoimmunity Screening for Kids (ASK) study design (BDC, Barbara Davis Center for Diabetes,CCCD, Colorado Center for Celiac Disease, ECL,Electrochemiluminescence Assay, PCP, Primary Care Physician, RBA, Radiobinding Assay)

Supplementary Table 1: Comparison of symptom questionnaires at the initial screen to the confirmation screen

Supplementary Table 2: Comparison of characteristics of screening-positive children who did or did not complete the confirmation visit. (ECL, electrochemiluminescence assay; RBA, radiobinding assay; CD, celiac disease)

* One subject who was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes prior to returning for a confirmation visit was excluded.