Abstract

Mechanically ventilated patients with ARDS due to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) seem particularly susceptible to AKI. Our hypothesis was that the renal blood flow could be more compromised in SARS-CoV-2 patients than in patients with “classical” ARDS. We compared the renal resistivity index (RRI) and the renal venous flow (RVF) in ARDS patients with SARS-CoV-2 and in ARDS patients due to other etiologies. Prospective, observational pilot study performed on 30 mechanically ventilated patients (15 with SARS-COV-2 ARDS and 15 with ARDS). Mechanical ventilation settings included constant-flow controlled ventilation, a tidal volume of 6 ml/kg of ideal body weight and the PEEP level titrated to the lowest driving pressure. Ultrasound Doppler measurements of RRI and RVF pattern were performed in each patient. Patients with SARS-COV-2 ARDS had higher RRI than patients with ARDS (0.71[0.67–0.78] vs 0.64[0.60–0.74], p = 0.04). RVF was not-continuous in 9/15 patients (71%) in the SARS-COV-2 ARDS group and in and 5/15 (33%) in the ARDS group (p = 0.27). A linear correlation was found between PEEP and RRI in patients with SARS-COV-2 ARDS (r2 = 0.31; p = 0.03) but not in patients with ARDS. Occurrence of AKI was 53% in patients with SARS-COV-2 ARDS and 33% in patients with ARDS (p = 0.46). We found a more pronounced impairment in renal blood flow in mechanically ventilated patients with SARS-COV-2 ARDS, compared with patients with “classical” ARDS.

Supplementary Information

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10877-020-00633-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: ARDS, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Coronavirus, Mechanical ventilation, Renal resistivity index, Acute kidney injury

Introduction

The occurrence of acute kidney injury (AKI) in mechanically ventilated patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) due to the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) ranges between 15 and 23% being as high as 50% in non-survivors. [1, 2]. COVID-19 may per se induce a kidney disease [3] but mechanical ventilation (MV) could play a pivotal role.

Recent guidelines recommend the use of lung-protective mechanical ventilation in ARDS, consisting in low tidal volume (VT) and relatively high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) [4]. This strategy could have a relevant hemodynamic impact [5, 6] and has been shown to increase renal arterial resistances and decrease renal venous return, leading to glomerular congestion and increase in kidney interstitial hydrostatic pressures [5–8]. In SARS-COV-2 ARDS respiratory system compliance (CRS) could be atypically high compared to the degree of arterial hypoxemia, leading the application of relatively high PEEP levels [9, 10]. Since the hemodynamic impact of PEEP is inversely proportional to respiratory system compliance (CRS), it might be then hypothesized that PEEP in patients with COVID-19 infection could result in greater extent of kidney damage compared to ARDS due to different etiologies.

Our hypothesis was that the degree of renal blood flow impairment in SARS-COV-2 ARDS compared to “classic” ARDS could be more pronounced. Accordingly, we performed an ultrasound evaluation of the renal resistivity index (RRI) and renal venous flow pattern (RVF) [11–13] in two groups of patients, i.e. with SARS-COV-2 ARDS and with classical ARDS, ventilated with the same lung-protective protocol.

Materials and Methods

Population

Prospective, observational pilot study performed in a COVID-19 Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and a mixed medical-surgical ICU at University Hospital of Ferrara, Italy. The study was approved by the ethic committee (approval number 339/2020). We included consecutive patients with SARS-COV-2 ARDS or ARDS undergoing mechanical ventilation. Exclusion criteria were: diagnosis of AKI before ICU admission, unsatisfactory ultrasound visualization, arrhythmia, renal replacement therapy and denied consent. All patients included in the SARS-COV-2 ARDS group had laboratory-confirmed COVID-19.

Mechanical ventilation settings

At the time of renal blood flow assessment, all patients were deeply sedated and paralyzed with continuous infusion of cis-atracurium 1–3 mcg/kg/min for clinical reasons. Mechanical ventilation settings included constant-flow controlled ventilation, a tidal volume of 6 ml/kg of ideal body weight and the PEEP level titrated to the lowest driving pressure. [14, 15] Briefly, PEEP was increased by 2 cm H2O step starting from 6 cm H2O, up to the PEEP level leading to a static end-inspiratory plateau pressure (PPLAT) of 28–30 cm H2O; then, the PEEP level corresponding to the lowest driving pressure was chosen.

The driving pressure was measured as:

where PEEPTOT is the total static positive end-expiratory pressure. PPLAT and PEEPTOT were measured through the occlusion technique (i.e. a 4 s airway opening occlusion maneuver at end-inspiration and end-expiration, respectively) [16].

Renal blood flow assessment

Ultrasound evaluation of renal blood flow was performed within 24 h from starting of MV. All the measurements were taken by a single well-trained anesthesiologist with certified experience (FA) on the right kidney with the patient in semi-recumbent position (30°), through a posterolateral approach. Color Doppler images were used to identify the interlobar vessels. An interlobar or arcuate artery was selected for pulse wave Doppler measurements and RRI was calculated as:

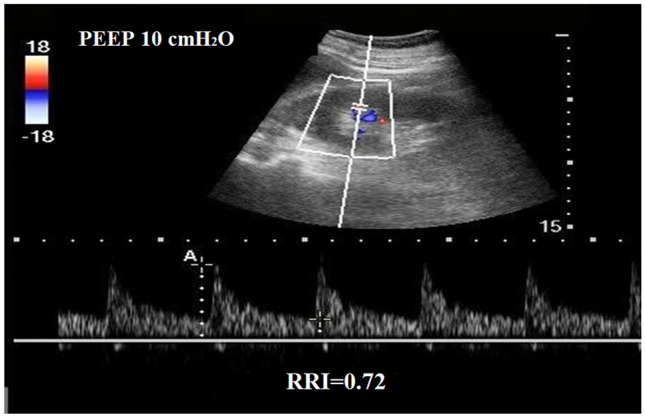

A representative Renal Resistivity Index measurement technique performed is showed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A representative Renal Resistivity Index measurement technique performed in patients with SARS-CoV-2 ARDS at PEEP 10 cm H2O

An RRI > 0.7 was deemed pathological. [11–13]

The RVF pattern was classified as continuous, biphasic or monophasic [11]. Under physiological conditions, the RVF pattern is continuous, whereas during renal congestion it becomes biphasic or even monophasic [11].

For both RRI and RVF three measurements were obtained over 3 cardiac cycles and the mean value was recorded for analysis.

Secondary outcomes

The occurrence of AKI, as well as need for renal replacement therapy (RRT), was recorded. Further, we investigated the ability of RRI to predict the occurrence of AKI and the need of RRT. AKI was defined according to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines as an increase in serum creatinine of 0.3 mg/dL within 48 h, an increase in serum creatinine to 1.5 times the baseline value present within the previous 7 days, or a urinary output <0.5 mL/kg/h for 6 h [17]. Indications for RRT were serum urea >150 mg/dL, severe hyperkalemia (over 6 mmol/L or with sign of electrocardiogram abnormalities), urine output <200 mL/die, fluid overload despite diuretic treatment [18].

Statistical analysis

Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation or medians with interquartile range, as appropriate. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the assumption of normality. Categorical data were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test as appropriate. Mann-Whitney U tests was used to compare continuous variables. Pearson correlation with R square was used to analyze the correlation. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves were used to analyze the ability of RRI to predict AKI. ROC curve analyses are reported as AUROC with 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Optimal cut-off scores were determined using Youden’s Index. Differences in repeated measurements in the two groups were analyzed using Friedman’s rank analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 25.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). For each statistical test a 2-tailed test was performed and a p value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Sample size

Using the upper confidence interval for the population variance approach to the sample size calculation a pilot sample size between 20 and 40 correspond to standardized effect sizes of 0.4 and 0.7 (for 90% power based on a standard sample size calculation). According to this issue, 30 patients (15 for each group) were included in the study.

Results

Population and renal blood flow evaluation

We included in the study 30 patients with ARDS, of which 15 had laboratory-confirmed SARS-COV-2 ARDS. Clinical characteristics and blood gas analysis at ICU admission are shown in Table 1. The median driving pressure was 12 [10–15] cm H2O, resulting in a static compliance of 43 [40–52] cm H2O/ml. Patients in the SARS-COV-2 ARDS group had lower PaO2/FiO2, higher PaCO2 and higher respiratory system compliance (Table 2).

Table 1.

Clinical and demographical characteristics of patients at ICU admission

| Variables | All patients n = 30 |

SARS-CoV-2 ARDS n = 15 | ARDS n = 15 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 64 [60–72] | 62 [55–69] | 67 [62–74] | 0.89 |

| Sex (F/M) | 5/25 | 2/13 | 3/12 | 0.99 |

| SOFA score at ICU admission | 8 [5–10] | 6 [4–10] | 9 [8–10] | 0.05 |

| Need for vasopressor, n (%) | 12 (40) | 5 (33) | 7 (47) | 0.71 |

| Epinephrine, n (%) | 1 (3) | – | 1 (7) | |

| Norepinephrine, n (%) | 11 (37) | 5 (33) | 6 (40) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 17 (57) | 8 (53) | 9 (60) | 0.71 |

| CKD, n (%) | 7 (23) | 3 (20) | 4 (27) | 0.99 |

| BMI > 35 (kg/m2), n (%) | 3 (10) | 1 (7) | 2 (13) | 0.99 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 6 (20) | 3 (20) | 3 (20) | 0.99 |

| Reasons for ICU admission | ||||

| Septic shock | 4 | 4 (27) | – | 0.09 |

| ARDS | 26 | 11 (73) | 15 | 0.09 |

| Laboratory data at ICU admission | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.0 [9.8–13.6] | 10.9 [9.6–12.4] | 12.8 [9.9–13.6] | 0.49 |

| Platelets (109/L) | 219 [179–302] | 263 [204–305] | 208 [143–301] | 0.19 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/L) | 1.0 [0.7–2.5] | 0.8 [0.7–1.2] | 2.5 [0.7–3.6] | 0.11 |

CKD Chronic kidney disease, BMI body mass index, PEEP positive end-expiratory pressure, PaCO2 arterial carbon dioxide tension

Table 2.

Renal blood flow evaluation and respiratory mechanics in patients with C-ARDS and ARDS

| Variables | SARS-CoV-2 ARDS n = 15 | ARDS n = 15 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renal blood flow evaluation | |||

| Renal resistivity index | 0.71 [0.67–0.78] | 0.64 [0.60–0.74] | 0.04 |

| Renal venous flow pattern | |||

| Continuous | 6 (40) | 10 (66) | 0.27 |

| Biphasic | 4 (27) | 3 (20) | 0.99 |

| Monophasic | 5 (33) | 2 (14) | 0.40 |

| Respiratory mechanics | |||

| Tidal volume (mL) | 440 [400–480] | 395 [350–480] | 0.27 |

| Respiratory rate | 18 [18–22] | 18 [16–20] | 0.14 |

| Minute ventilation (L/m) | 7.9 [7.2–9.0] | 7.4 [6.0–8.6] | 0.10 |

| Plateau pressure (cm H2O) | 22 [22–24] | 21 [18–24] | 0.11 |

| PEEP (cm H2O) | 14 [12–14] | 10 [10–12] | 0.004 |

| Driving pressure (cm H2O) | 10 [8–10] | 9 [8–12] | 0.90 |

| Static compliance (ml/cm H2O) | 45 [41–52] | 40 [37–47] | 0.03 |

| Hemodynamic parameters | |||

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 75 [70–80] | 82 [67–91] | 0.21 |

| Heart rate | 90 [86–104] | 89 [79–95] | 0.84 |

| Blood gas analysis | |||

| PaO2/FiO2 (mmHg) | 118 [94–151] | 193 [148–209] | 0.001 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 57 [48–64] | 46 [36–52] | 0.02 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 1.2 [1.2–1.6] | 2.2 [1.1–3.2] | 0.13 |

SARS-CoV-2 ARDS Coronavirus-induced ARDS; PEEP positive end-expiratory pressure, PaCO2 arterial carbon dioxide tension

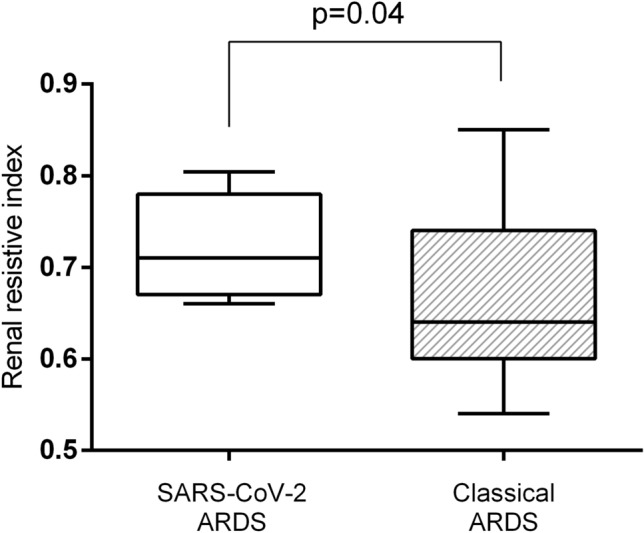

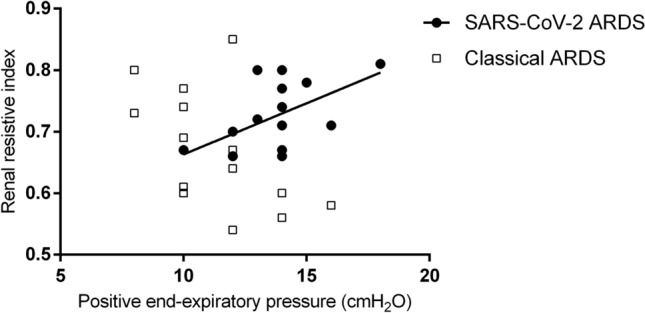

The renal blood flow evaluation was performed after 1 [0–1] day from starting of MV. As shown in Table 1, compared with patients with classical ARDS, patients with SARS-COV-2 ARDS had higher RRI (0.71 [0.67–0.78] vs 0.64 [0.60–0.74], p = 0.04) (Fig. 2). In patients with SARS-COV-2 ARDS, but not in patients with classical ARDS, there was a linear correlation between PEEP and RRI (r2 = 0.31; p = 0.03) (Fig. 3). The RVF was not-continuous in 9/15 patients (71%) in SARS-COV-2 ARDS group and 5/15 (33%) in not-CoV-2 (p = 0.27).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of renal resistivity index or ARDS

Fig. 3.

Correlation between PEEP level and renal resistivity index in patients with SARS-CoV-2 ARDS or ARDS

Secondary outcomes

AKI occurred in 8/15 of patients (53%) in SARS-COV-2 ARDS and in 5/15 (33%) in classical ARDS (p = 0.46). AKI was detected after 2 [1, 2] days (range 1–4) from renal blood flow evaluation. Four patients (4/15, 27%) in SARS-COV-2 ARDS group needed RRT versus one in the classical ARDS group (1/15, 6%; p = 0.33). Additional data regarding SARS-COV-2 ARDS patients are given in Table S1 and Fig. S1. In particular, SARS-COV-2 ARDS patients with AKI were more likely to experience a subsequent impairment in respiratory system compliance (Fig. S1). Taking into account the whole population, patients who developed AKI had higher RRI (0.77 [0.73–0.80] vs 0.66 [0.60–0.69]; p = 0.001) as well as higher percentage of impaired RVF (13/13 vs 1/17; p < 0.001). The RRI was associated with the subsequent occurrence of AKI (AUROC 0.938 [0.93–0.99]; p < 0.001). The Youden index analysis showed that RRI > 0.71 was the best cut-off value to predict AKI, with 90% sensitivity and 100% specificity. The RRI was also a predictor for RRT (AUROC = 0.896 [0.73–0.98]; best cut-off 0.77; sensitivity 80% specificity 92%).

Discussion

The main finding of our study is that the renal blood flow is more compromised in mechanically ventilated patients with SARS-COV-2 ARDS than in patients with classical ARDS.

The pathogenesis of renal dysfunction in patients with COVID 19 is multifactorial [2, 3, 19]. A recent observational study including 116 hospitalized patients shows that non ventilated patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia seldom develop AKI [20]; conversely, the incidence of AKI was up to 23% in patients requiring respiratory support [1]. Despite the most severe disease form in ventilated patients could explain these findings, positive pressure ventilation could per se play a role [5–8]. Lung protective mechanical ventilation protocols for ARDS may result in relatively high PEEP levels, that may critically increase the pericardial pressure decreasing the venous return and causing glomerular congestion via the increase in kidney interstitial hydrostatic pressure [6, 7], which increases arterial resistances [6, 7]. Our data confirm that SARS-CoV-2 induced ARDS is characterized by an atypically high respiratory system compliance (CRS), compared to the degree of arterial hypoxemia [9, 10, 21, 22] Since the hemodynamic effects of PEEP are enhanced when the CRS is relatively high [22–24], we speculate that the effect of PEEP on kidney perfusion could have been more pronounced in patients with SARS-CoV-2 ARDS than in those with classical ARDS. This hypothesis is supported by recent findings showing hemodynamics alteration given by “higher” PEEP levels in SARS-CoV-2 ARDS with static respiratory compliance higher than or equal to 50 mL/cm H2O [24]. Our finding of a linear relationship between RRI and PEEP in patients with SARS-CoV-2 ARDS and not in patients with ARDS (Fig. 3) and the fact that the RVF was not-continuous in 71% of our patients SARS-COV-2 ARDS seems to support this hypothesis. The RRI has recently gained importance as a marker of renal perfusion and to predict AKI [11–13, 25] and its severity [26]. On the other hand, the non-continuous RVF pattern suggests glomerular congestion, which may be an additional cause of renal blood flow impairment [11]. High RRI is associated with need for vasopressors, hypotension and lactate levels [12], whereas non-continuous RVF have been described in the context of increased pulmonary wedge pressure [11]. Even if the RRI difference between SARS-CoV-2 ARDS and classical ARDS could seems numerically low (0.71 [0.67–0.78] vs 0.64 [0.60–0.74]), it reflects a clinically relevant change. Indeed, as showed in previous studies, RRI value over 0.70 is a threshold useful to discern between a normal or a pathological renal blood flow [12, 27]. In particular, RRI > 0.70 was associated with persistent AKI [12] and worse renal prognosis [27] when compared to RRI values between 0.65 and 0.70.

Our study has some limitations. First, due to the lack of clinical study in this field, we were unable to perform an accurate power analysis and the small sample size could limit the interpretation of our results and does not account for covariate adjustment. Second, our study was not designed to separate between the different mechanism that could explain the impairment of renal blood flow. Nonetheless, the correlation between PEEP levels and RRI seems to suggest a possible role of mechanical ventilation in the RRI impairment. Finally, we cannot exclude that the water overload in SARS-COV-2 ARDS could have contribute to the described renal congestion and therefore renal impairment. Nonetheless, hemodynamic monitoring was not systematically available in our patients and therefore it would be impossible to correctly analyses this issue with our data.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we showed that during lung-protective mechanical ventilation, the renal blood flow is more impaired in patients with SARS-CoV-2 ARDS than in patients with classical ARDS. Our findings suggest to carefully assess renal blood flow and even subtle signs of AKI in patients with SARS-CoV-2 ARDS requiring mechanical ventilation. Further studies are needed to assess the specific role of mechanical ventilation in the pathogenesis of the SARS-CoV-2 ARDS kidney perfusion impairment and, eventually, if different approaches to PEEP setting could better preserve renal perfusion.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Information 2 (DOCX 18 kb)

Supplementary Information 3 (DOCX 19 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the nurses and caregivers for their active involvement in the management of patients during this study.

Abbreviations

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- KDIGO

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes

- MV

Mechanical ventilation

- ROC

Receiver operator characteristic

- RRI

Renal resistivity index

- RRT

Renal replacement therapy

- RVF

Renal venous flow pattern

- SARS-CoV-2

Acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Authors’ contributions

FA, VCA and SS was involved in the conception and the design of the study, analyzed the data and wrote the paper. FA and ME collected the data. FA performed the statistical work. MD, GS, FM and LG contributed to analysis of the data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors reviewed the manuscript and agreed with the final version.

Fundings

This study was financially supported by the University of Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy.

Compliance with ethical standard

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Informed consent

Prospective, observational pilot study performed in a COVID-19 Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and a mixed medical-surgical ICU at University Hospital of Ferrara, Italy. The study was approved by the ethic committee (approval number 339/2020). We included consecutive patients with SARS-COV-2 ARDS or ARDS undergoing mechanical ventilation. Exclusion criteria were: diagnosis of AKI before ICU admission, unsatisfactory ultrasound visualization, arrhythmia, renal replacement therapy and denied consent. All patients included in the SARS-COV-2 ARDS group had laboratory-confirmed COVID-19.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the ethic committee (approval number 339/2020).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations

References

- 1.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pei G, Zhang Z, Peng J, Liu L, Zhang C, Yu C, et al. Renal involvement and early prognosis in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(6):1157–1165. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020030276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K, Zhang M, Wang Z, Dong L, et al. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;5:829–838. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poston JT, Patel BK, Davis AM. Management of critically Ill adults with COVID-19. JAMA. 2020; E-pub ahead of printing [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Vieillard-Baron A, Loubieres Y, Schmitt JM, Page B, Dubourg O, Jardin F. Cyclic changes in right ventricular output impedance during mechanical ventilation. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:1644–1650. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.5.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joannidis M, Forni LG, Klein SJ, Honore PM, Kashani K, Ostermann M, et al. Lung-kidney interactions in critically ill patients: consensus report of the Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) 21 Workgroup. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(4):654–672. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05869-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panitchote A, Mehkri O, Hastings A, Hanane T, Demirjian S, Torbic H, et al. Factors associated with acute kidney injury in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s13613-019-0552-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurkan OU, O’Donnell C, Brower R, Ruckdeschel E, Becker PM. Differential effects of mechanical ventilatory strategy on lung injury and systemic organ inflammation in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;285:L710–L718. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00044.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Antonelli M, Cabrini L, Castelli A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Rossi S. COVID-19 pneumonia: ARDS or not? Crit Care. 2020;24:154. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02880-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Husain-Syed F, Birk HW, Ronco C, Schörmann T, Tello K, Richter MJ. Doppler-derived renal venous stasis index in the prognosis of right heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(21):e013584. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliveira RAG, Mendes PV, Park M, Taniguchi LU. Factors associated with renal Doppler resistive index in critically ill patients: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s13613-019-0500-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dewitte A, Coquin J, Meyssignac B, Joannès-Boyau O, Fleureau C, Roze H, et al. Doppler resistive index to reflect regulation of renal vascular tone during sepsis and acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2012;16(5):R165. doi: 10.1186/cc11517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pereira Romano ML, Maia IS, Laranjeira LN, Damiani LP, Paisani DM, Borges MC. Driving pressure-limited strategy for patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS): a pilot randomized clinical trial. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(5):596–604. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201907-506OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahetya SK, Hager DN, Stephens RS, Needham DM, Brower RG. PEEP titration to minimize driving pressure in subjects with ARDS: a prospective physiological study. Respir Care. 2020;65(5):583–589. doi: 10.4187/respcare.07102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hess DR. Respiratory mechanics in mechanically ventilated patients. Respir Care. 2014;59(11):1773–1794. doi: 10.4187/respcare.03410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120:c179–c184. doi: 10.1159/000339789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bagshaw SM, Cruz DN, Gibney RT, Ronco C. A proposed algorithm for initiation of renal replacement therapy in adult critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2009;13:317. doi: 10.1186/cc8037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su H, Yang M, Wan C, Yi LX, Tang F, Zhu HY, et al. Renal histopathological analysis of 26 postmortem findings of patients with COVID-19 in China. Kidney Int. 2020;98(1):219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L, Li X, Chen H, Yan S, Li D, Li Y. Coronavirus disease 19 infection does not result in acute kidney injury: an analysis of 116 hospitalized patients from Wuhan, China. Am J Nephrol. 2020;51(5):1–6. doi: 10.1159/000507471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marini JJ, Gattinoni L. Management of COVID-19 respiratory distress. JAMA. 2020;323(22):2329. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Caironi P, Busana M, Romitti F, Brazzi L, et al. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1099–1102. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X, Wang X, Honore PM, Spapen HD, Liu D. Renal failure in critically ill patients, beware of applying (central venous) pressure on the kidney. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):91. doi: 10.1186/s13613-018-0439-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grasso S, Mirabella L, Murgolo F, Di Mussi R, Pisani L, Dalfino L, et al. Effects of positive end-expiratory pressure in “High Compliance” severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(12):e1332–e1336. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garnier F, Daubin D, Larcher R, Bargnoux AS, Platon L, Brunot V. Reversibility of acute kidney injury in medical ICU patients: predictability performance of urinary tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 × insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 and renal resistive index. Crit Care Med. 2020;4:e277–e284. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haitsma Mulier JLG, Rozemeijer S, Röttgering JG, Spoelstra-de Man AME, Elbers PWG, Tuinman PR, et al. Renal resistive index as an early predictor and discriminator of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: a prospective observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0197967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugiura T, Wada A. Resistive index predicts renal prognosis in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(9):2780–2785. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information 2 (DOCX 18 kb)

Supplementary Information 3 (DOCX 19 kb)