SETD2 controls neocortical area patterning and social behaviors.

Abstract

Proper formation of area identities of the cerebral cortex is crucial for cognitive functions and social behaviors of the brain. It remains largely unknown whether epigenetic mechanisms, including histone methylation, regulate cortical arealization. Here, we removed SETD2, the methyltransferase for histone 3 lysine-36 trimethylation (H3K36me3), in the developing dorsal forebrain in mice and showed that Setd2 is required for proper cortical arealization and the formation of cortico-thalamo-cortical circuits. Moreover, Setd2 conditional knockout mice exhibit defects in social interaction, motor learning, and spatial memory, reminiscent of patients with the Sotos-like syndrome bearing SETD2 mutations. SETD2 maintains the expression of clustered protocadherin (cPcdh) genes in an H3K36me3 methyltransferase–dependent manner. Aberrant cortical arealization was recapitulated in cPcdh heterozygous mice. Together, our study emphasizes epigenetic mechanisms underlying cortical arealization and pathogenesis of the Sotos-like syndrome.

INTRODUCTION

The six-layered mammalian cerebral cortex, also known as the neocortex, is tangentially subdivided into distinct functional areas including the primary motor cortex (M1), visual cortex (V1), somatosensory cortex (S1), and auditory cortex (A1), which fulfills the function of sensory perception, autonomous movements, and social behaviors. These areas are anatomically and functionally distinct subdivisions distinguished from one another by differences in patterns of gene expression, cytoarchitecture, and input and output connections (1, 2). The formation and specification of distinct functional areas within the neocortex is called neocortical area patterning, also referred to as arealization (3). The process of neocortical arealization is a stereotypical hierarchy initiated by morphogens (fibroblast growth factors, bone morphogenetic proteins, and WNTs) secreted from telencephalic patterning centers, such as commissural plate, cortical hem, and cortical antihem. These molecules subsequently set up the gradient expression of major early patterning transcription factors (TFs; Emx2, Pax6, Coup-TF1, and Sp8) and dictate the rostral/caudal and ventral/dorsal positional identity within cortical precursor cells in the ventricular zone (VZ) by a complex interaction (2). The graded distributed TFs impart general area identity to cortical neurons and ultimately form sharp regional boundaries between anatomically distinct and functionally specialized subdivisions, which are progressively refined through additional patterning TFs (i.e., Bhlhb5, Lmo4, Lhx2, Tbr1, Pbx, and Ctip1) and thalamocortical inputs (2, 4–9).

Histone methylation is essential for embryonic development, and its proper regulation is critical for ensuring the orchestrated expression of gene networks that control pluripotency, body patterning, and differentiation along specified lineages (10). Dysregulated histone methylation can cause defects in body patterning and development of specific organs (11). Although the interplay of layer-specific TFs and histone modifiers including actions of the Polycomb Repressive Complex is essential for the temporal control of cortical neurogenesis and gliogenesis (12–15), very little is known whether histone modifications play a direct role in cortical arealization (16).

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by defects with social communication and by repetitive and/or restricted patterns of behaviors. Neuroanatomical and imaging studies indicated that ASD may involve a combination of brain enlargement in some areas and reduction in others (17, 18). The Sotos-like syndrome (also known as the Luscan-Lumish syndrome, OMIM 616831), an overgrowth syndrome with clinical characteristics of intellectual disability, speech delay, macrocephaly, facial dysmorphism, and ASD, is genetically associated with loss-of-function SETD2 mutations (19, 20). SETD2 (also known as HYPB), the lysine-36 of histone H3 trimethyltransferase (H3K36me3), has been reported to be involved in regulating transcription, alternative splicing, and DNA repair (21–23) and has implications in multiple cellular processes during embryonic development and carcinogenesis (24, 25). However, it remains elusive whether the H3K36me3 methyltransferase activity of SETD2 is critical for brain development, social behaviors, and the pathogenesis of the Sotos-like syndrome.

Here, we report that Setd2 conditional knockout (cKO) mice display defects of social interaction, motor learning, and spatial memory, reminiscent of patients with the Sotos-like syndrome bearing SETD2 mutations. Loss of Setd2 in neural precursors results in defects of cortical area patterning with irregular upper-layer cytoarchitecture. Anterograde labeling indicates aberrant corticothalamic and thalamocortical projections in brains of Setd2 cKO mice. The Setd2-deficent cortices display reduced expression of cPcdh, adhesion molecules crucial for establishing neuronal identity and neural circuits (26–28). Similar to Setd2 mutants, Pcdhαβγ+/− mice also exhibit defects of the acquisition of cortical area identities. Last, the SETD2L1815W mutation found in a patient with the Sotos-like syndrome abolishes the trimethyltransferase activity of SETD2.

RESULTS

Setd2 is required for proper area patterning of the cerebral cortex

We first asked whether SETD2, the methyltransferase for H3K36me3, regulates areal patterning of the cerebral cortex. We generated Setd2 cKO mice using the Cre/loxP system. Both Nestin-Cre and Emx1-Cre were applied to respectively ablate Setd2 in neural precursors throughout the nervous system (Setd2Nestin-cKO) or in the dorsal forebrain that generates the neocortex (Setd2Emx1-cKO) (fig. S1, A and B). Setd2Nestin-cKO and Setd2Emx1-cKO mice were born at Mendelian ratios (fig. S1C), but Setd2Nestin-cKO pups died a few hours after birth. In situ hybridization (ISH) revealed that the transcripts of Setd2 are expressed in both progenitor [ventricular zone/subventricular zone (VZ/SVZ)] and neuronal [cortical plate (CP)] zones in developing neocortices, which are mostly lost in Setd2Nestin-cKO and Setd2Emx1-cKO brains (fig. S1D). SETD2 is also expressed in developing human brains (fig. S1E).

At postnatal day zero (P0), Lmo4 expression normally delineates the frontal/motor cortex and is excluded from somatosensory cortex (5); Epha7 is expressed throughout the neocortex but at lower levels in intermediate parts of the neocortex corresponding to the somatosensory area (29); Rorβ is expressed in layer IV with a high lateral to low medial gradient (30). ISH experiments revealed medial retraction of Lmo4 and Epha7 at the caudal motor cortex, accompanied by medial extension of Rorβ at the cingulate cortex in Setd2Nestin-cKO and Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices (fig. S2A), implying regional shifts of cortical areas. Since Setd2Nestin-cKO mice could not survive postnatally, we used Setd2Emx1-cKO mice for further analysis. The width and area of P7 Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices were ~10% smaller than of controls (Fig. 1, A and B, and fig. S2, B and C). To monitor expression changes of Lmo4, Cad8, and Rorβ in the entire neocortex, we carried out whole-mount ISH at P7, when neurons have migrated to their proper positions in the neocortex. Lmo4 (a marker that is highly expressed rostrally in motor cortex, medially in cingulate cortex, and caudally in higher-order visual areas but is excluded from primary sensory areas) expression revealed that the somatosensory region of Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices expanded medially, with the visual area compressed caudally relative to control cortices (Fig. 1C and fig. S2D). The territories of Cad8 (a marker mainly labeling frontal/motor and visual cortex) expression in the frontal/motor and visual cortices were blurred in Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices (Fig. 1D and fig. S2E). Moreover, Rorβ (a marker highly expressed in S1, A1, and V1) expression revealed that the entire sensory map, especially the barrel cortex, was greatly diminished in Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices. Consistent with the observations in Lmo4 ISH, visual area was also compressed caudally in Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices (Fig. 1E and fig. S2F).

Fig. 1. Ablation of Setd2 causes abnormal area patterning of the cerebral cortex.

(A) Representative images of fixed P7 control and Setd2Emx1-cKO brains. (B) Comparison of cortical area of hemispheres (blue in schematic). (C to E) Analyses of Lmo4 (C), Cad8 (D), and Rorβ (E) expression by whole-mount ISH on P7 control and Setd2Emx1-cKO brains. Arrowheads indicate expression alterations. (F, H, and J) Lmo4 (F), Cad8 (H), and Rorβ (J) expressions in P7 control and Setd2Emx1-cKO sagittal brain sections, with boxed somatosensory regions magnified on the right. (G, I, and K) Quantifications of normalized intensities of ISH signals in (F), (H), and (J). n = 3 brains for each genotype. (L and M) Left: 5-HT immunostaining on control (L) and Setd2Emx1-cKO (M) tangential sections of P7 flattened cortices. Right: 5-HT reveals primary sensory areas. (N to Q) Measurements of 5-HT–stained tangential sections. n = 6 for control [n = 5 in (Q)] and n = 4 for Setd2Emx1-cKO. Data are represented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. Scale bars, 1 mm (A, C to E, F, H, J, L, and M) and 100 μm (magnified views in F, H, and J).

We further studied the expression of molecular markers (Lmo4, Cad8, and Rorβ) in P7 sagittal sections to assess the role of Setd2 in regulating cortical regionalization. Lmo4 and Cad8 are predominantly expressed in layers II/III and layer V in rostral cortical areas (31, 32), and Rorβ is a layer IV marker (33). In Setd2Emx1-cKO mutants, Lmo4-labeled cells span the whole thickness of layer V of the somatosensory region, and Lmo4’s expression in the frontal/motor cortices was greatly reduced (Fig. 1, F and G). Similarly, the layered distribution of Cad8-expressing cells was also indiscernible in Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices (Fig. 1, H and I), while Rorβ expression was severely reduced in Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices (Fig. 1, J and K). Of note, expression patterns of Lmo4, Cad8, and Rorβ in P7 Setd2Emx1-het (heterozygous) cortices did not display abnormalities found in Setd2Emx1-cKO mice (fig. S3). We thus examined serotonin [5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)] distribution in tangential sections of flattened P7 cortices. In accordance with ISH results, Setd2Emx1-cKO mice displayed prominent caudal expansion of the frontal/motor cortex, caudomedial shift of the somatosensory cortex, and compromised anterolateral barrel subfield (Fig. 1, L to Q).

Dysregulated patterning TFs lead to abnormal area patterning in Setd2Emx1-cKO mice. Therefore, we examined the expression of four major patterning TFs, Emx2, Pax6, Coup-TF1, and Sp8, in the VZ of E13.5 (embryonic day 13.5) control and Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices. ISH experiments revealed that their expression patterns were not altered in cortical progenitors of Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices, indicating that Setd2 regulates cortical arealization in a patterning TF-independent way (fig. S4).

The layered structure of cerebral cortex is largely intact in Setd2Emx1-cKO brains

We next asked whether ablation of Setd2 leads to defects of cortical neurogenesis. At P7, the cortical thickness was not changed in Setd2Emx1-cKO brains (fig. S5, A and B). However, we noticed that there were patches of tissue devoid of cells in the superficial layer of lateral cortices (Fig. 1J and fig. S5, C, F, and L). To determine whether cellular loss of superficial cortical neurons could account for the honeycomb-like structures, we quantified cleaved Casp3+ cells and did not detect enhanced cell death in P0 Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices (fig. S5, D and E). Moreover, cell densities were the same in P7 control and Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices (fig. S5, F and G). Accordingly, immunofluorescent staining of SATB2, CTIP2, and FOXP2, markers for layer-specific projection neurons, did not detect abnormalities in medial Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices (fig. S5, H to K). Although immunofluorescent staining of CUX1 in lateral Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices revealed honeycomb-like structures at layer IV, cell densities of CUX1+ cells were not altered (fig. S5, L and M). To ask whether Setd2 loss hampers self-renewal and transit amplification of cortical progenitors, we performed 30-min bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) pulse labeling at E13.5 and E15.5. Control and Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices exhibited comparable densities of BrdU+ cells (fig. S5, N and O). Moreover, ratios of intermediate progenitor cells (TBR2+) were the same between control and Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices (fig. S5, P and Q). Thus, Setd2 loss has minimal effects on self-renewal and transit amplifying of cortical progenitors but causes aberrant cytoarchitectures of lateral upper layers.

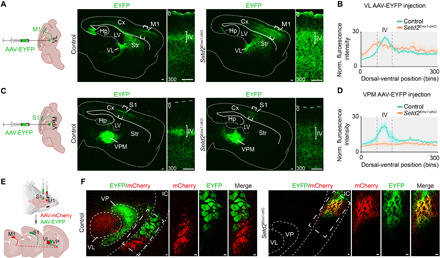

Setd2 is essential for the formation of corticothalamic-cortical circuits

Shifts of cortical areas and aberrant cytoarchitecture could lead to disrupted circuits between the neocortex and the thalamus (9, 34, 35). Hence, we injected anterograde adeno-associated viruses expressing enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (AAV-EYFP) into the ventral lateral nucleus (VL) or the ventral posteromedial nucleus (VPM) of adult control and Setd2Emx1-cKO thalami. In control mice, neurons in VL and VPM mostly projected into layer IV of motor and somatosensory cortex, respectively (Fig. 2, A and B). In contrast, these projections became obscure and dispersed in Setd2Emx1-cKO brains (Fig. 2, C and D). Next, AAV-EYFP and AAV-mCherry were simultaneously injected into layer VI of ipsilateral somatosensory and motor cortex, which anterogradely labeled descending tracts from corticothalamic projection neurons to the ventral posterior nucleus (VP) and VL of the thalamus, respectively, in adult control brains. In contrast, these tracts failed to project into VP and VL but showed overlapping characteristics in the internal capsule (IC) of Setd2Emx1-cKO brains (Fig. 2, E and F). Because regional identity in Setd2Emx1-cKO brains was altered, we examined areal identities of injection sites by applying Rorβ ISH on adjacent coronal sections of adult brains. Results showed that AAV-mCherry or AAV-EYFP virus were precisely injected into layer VI of the M1 or S1 cortex in both control and Setd2Emx1-cKO brains (fig. S6). Thus, loss of Setd2 causes impairments in reciprocal corticothalamic projections. Given that extrinsic mechanisms such as thalamocortical input can regulate area patterning and shape cortical plate cytoarchitecture (2), the failed thalamocortical topography and compromised thalamic input may partly account for disorganized layer IV neurons in lateral Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices.

Fig. 2. Setd2 is essential for the formation of corticothalamo cortical circuits.

(A and C) Representative adult sagittal sections showing anterograde labeling of thalamocortical projections by injecting recombinant AAV-EYFP into the VL (ventral lateral nucleus of thalamus) (A) and the VPM (ventral posteromedial nucleus of thalamus) (C). Boxed regions are enlarged in right panels showing the thalamocortical projection terminated in cortices. (B and D) Quantifications of the fluorescence distribution in motor cortices (A) and somatosensory cortices (C). n = 3 brains for each genotype; data are presented as means ± SEM. (E) Schematic illustration showing anterograde labeling of corticothalamic axons to demarcate VL and VP (ventral posterior nucleus of thalamus) by injecting AAV-mCherry and AAV-EYFP into layer VI of M1 and S1 cortex. (F) Representative adult coronal sections indicating corticothalamic projections terminated in VL and VP, respectively, in control brains (left). The enlarged boxes displaying discrete axons in the IC. In Setd2Emx1-cKO brains (right), corticothalamic axons from M1 and S1 fail to sort into VL and VP, with overlapping tracts in the IC. Cx, cortical cortex; Hp, hippocampus; LV, lateral ventricle; Str, striatum; IC, internal capsule. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Setd2Emx1-cKO mice exhibit defects in social interaction, motor learning, and spatial memory

Loss-of-function SETD2 mutations were identified in the Sotos-like syndrome, an overgrowth syndrome with clinical characteristics of intellectual disability, macrocephaly, and ASD. We have shown that Setd2 loss causes aberrant cortical arealization and corticothalamic-cortical projections. We then examined whether these structural alterations caused by Setd2 loss associate with behavioral alterations found in patients with the Sotos-like syndrome. Open-field tests indicated that Setd2Emx1-cKO mice tended to be immobilized and did not explore the center area (Fig. 3, A to D and movie S1). This could be due to either decreased willingness of Setd2Emx1-cKO mice to explore, a hallmark of ASD, or increased anxiety. To discriminate these two possibilities, we performed three-chamber social tests and found that Setd2Emx1-cKO mice spent significantly shorter time with strangers compared to controls and were more likely to stay in the central chamber (Fig. 3, E and F, and movie S2). However, the immobility time for Setd2Emx1-cKO mice spent in tail suspension and forced swim tests was comparable to control mice (Fig. 3, G and H), indicating that Setd2Emx1-cKO mice did not show depression-related behavior. Moreover, Setd2Emx1-cKO and control mice spent similar amount of time in open arms of elevated plus maze (Fig. 3I), suggesting that Setd2Emx1-cKO mice were not hypersensitive to anxiety. Morris water maze experiments indicate that Setd2Emx1-cKO mice have compromised capacity for spatial learning (Fig. 3J). In the probe trial, Setd2Emx1-cKO crossed the platform fewer times (Fig. 3K), whereas control and Setd2Emx1-cKO mice showed no differences in swimming distances and velocity (Fig. 3, L and M). In addition, rotarod tests revealed defects of motor coordination and learning in Setd2Emx1-cKO mice (Fig. 3N). Setd2Emx1-cKO mice did not show enhanced repetitive patterns of behavior such as self-grooming (fig. S7A). Previous studies showed that EMX1 is also expressed in whisker pad muscles in addition to the dorsal forebrain (36). We therefore measured whisker movements (vibrating frequencies and angular velocities) of freely moving control and Setd2Emx1-cKO mice. Data showed that whisker movements of Setd2Emx1-cKO mice were indistinguishable to controls (fig. S7, B to E), ruling out that the social behavior defects in Setd2Emx1-cKO mice are due to whisker pad muscle dysfunctions. Overall, loss of Setd2 in mice recapitulates some ASD-like phenotypes including intellectual disability and defects in social communications found in human patients with the Sotos-like syndrome with SETD2 mutations.

Fig. 3. Setd2Emx1-cKO mice exhibit defects in social interaction, motor learning, and spatial memory.

(A) Representative traces of a control mouse and a Setd2Emx1-cKO mouse in the open-field arena. (B to D) Quantification of mobility time (B), number of entries into center (C), and time in the center (D) in the open-field test. (E) Representative tracing heatmap of a control mouse and a Setd2Emx1-cKO mouse during three-chamber sociability test and novel sociability test. (F) Quantification of (E). (G and H) Immobility time in tail suspension (G) and forced swim test (H). (I) Time spent in open arms in elevated plus maze test. (J) Latency to find the hidden platform across training days. (K) Frequencies of platform crossing during a probe trial (without a platform) after training. (L and M) Distance moved (L) and velocity (M) during the probe trial. (N) Latency to fall during the rotarod test. Each point represents data derived from one mouse. Data are represented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant. n = 9 mice for control [n = 7 in (I)] and n = 11 mice for Setd2Emx1-cKO.

Haploinsufficient Pcdhαβγ cortices display defects of area patterning

To gain insights into global changes in gene expression profiles, we examined transcriptomic alterations upon Setd2 deletion using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis. Notably, almost all clustered protocadherin (cPcdh), genes encoding adhesion molecules crucial for establishing neuronal identity and neural circuits (26, 37), were drastically down-regulated in E13.5 Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices (Fig. 4A; fig. S8, A to D; and tables S3 and S4). In mammals, clustered Pcdh proteins are encoded by more than 50 Pcdh genes that are tandemly organized into three gene clusters (Pcdhα, Pcdhβ, and Pcdhγ) (38). cPcdh genes were found to be mutated or dysregulated in a wide variety of neurological and neurodevelopmental disorders including ASD (39–42). The down-regulation of cPcdh transcripts was validated by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) in adult cortices (Fig. 4B) and ISH in P7 cortices (fig. S8E). To investigate whether Setd2 regulates area patterning via cPcdh, we generated cPcdh mutant mice, in which the Pcdhα, Pcdhβ, and Pcdhγ locus (~ 914 kb) were removed by the CRISP/Cas9 gene editing system (Fig. 4C). Because mice that lack cPcdh were observed to be homozygous lethal and heterozygous viable (28), we used cPcdh heterozygotes (Pcdhαβγ+/−) for further analysis. We examined the expression of Lmo4, Cad8, and Rorβ by ISH on P7 sagittal sections. In Pcdhαβγ+/− brains, the expression of both Lmo4 and Cad8 were greatly compromised in the upper layers of the somatosensory cortices. It is noteworthy that Pcdhαβγ+/− brains exhibited a notable reduction of Lmo4 expression in the frontal/motor cortices (Fig. 4, D to G). In addition, Rorβ expression was also remarkably reduced in Pcdhαβγ+/− cortices (Fig. 4, H and I). These expression changes of areal markers in Pcdhαβγ+/− cortices largely recapitulated those found in Setd2Emx1-cKO brains (Fig. 1, F to K).

Fig. 4. Pcdhαβγ haploinsufficient cortices display area patterning deficiency.

(A) E13.5 control and Setd2Emx1-cKO dorsal cortices were subjected to RNA-seq transcriptome analysis. Fold change (log2) of expressions of cPcdh genes in Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices relative to control is shown. (B) Validation of Setd2 and cPcdh expression of adult control and Setd2Emx1-cKO neocortices by qRT-PCR analysis (n = 3 mice for each genotype). (C) Generation and genotyping of Pcdhαβγ heterozygous mice. WT, wild-type; gRNA, guide RNA. (D, F, and H) ISH for Lmo4 (D), Cad8 (F), and Rorβ (H) mRNA expression in P7 control and Pcdhαβγ+/− sagittal brain sections, with boxed somatosensory regions magnified on the right. (E, G, and I) Quantification of normalized intensity of ISH signals in boxed regions of (D), (F), and (H). The y axes represent relative positions from the pial surface to the ventricle surface, with cortices evenly divided into 500 bins. The intensity values are normalized to background. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. Data are represented as means ± SEM. Scale bars, 1 mm (D, F, and H), 100 μm (magnified views in D, F and H).

Loss of SETD2-mediated H3K36me3 modifications and enhanced DNMT3A/B association at cis-regulatory sites of cPcdh genes in Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices

We next asked whether the expression of cPcdh depends on the H3K36 trimethylation activity of SETD2. As expected, the H3K36me3 modification was diminished in E11.5 Setd2Emx1-cko dorsal forebrains and in E13.5 Setd2Emx1-cKO and Setd2Nestin-cKO cortices (Fig. 5A), supporting that SETD2 is the primary methyltransferase for H3K36me3. Furthermore, chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) detected nearly complete loss of H3K36me3 at gene bodies (Fig. 5B), as well as cPcdh’s key cis-regulatory loci (HS-7L, HS5-1aL, and HS16) in E13.5 Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices (Fig. 5, C and D). It has been reported that dimethylation and trimethylation at H3K36 can be recognized by DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A) and DNMT3B, respectively, suggesting that SETD2 may have a role in DNMT3A/B-mediated DNA methylation (43, 44). Moreover, the DNA methylation profiling indicated that loss of SETD2 causes decreased CpG methylation levels in the gene body regions but increased levels in the intergenic regions (45). We thus analyzed DNMT3A and DNMT3B binding to the cPcdh enhancers and promoters in E13.5 control and Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices using ChIP-qPCR (quantitative PCR) and observed enhanced binding of DNMT3A and DNMT3B (especially DNMT3B) to HS7L and HS5-1aL enhancers of cPcdh in Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices. In contrast, the associations of DNMT3A/B with cPcdh promoters were not altered in Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices (Fig. 5E). Previous studies showed that enhancers’ activities are inversely correlated with DNA methylation density (46). Therefore, the enrichment of de novo DNA methyltransferases DNMT3A/B at cPcdh enhancers in Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices may contribute to the down-regulation of cPcdh.

Fig. 5. H3K36me3 modifications are reduced in cis-regulatory sites of cPcdh genes in Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices.

(A) H3K36me3 immunofluorescence on E11.5 (left) coronal and E13.5 (right) sagittal brain sections. Boxed regions were enlarged on the right. (B) ChIP-seq density heatmaps in E13.5 control (n = 2) and Setd2Emx1-cKO (n = 2) cortices. Plots depicting H3K36me3 signals from 3 kb upstream of the transcription start site (TSS) to 3 kb downstream of the transcription end site (TES). Each line in a heatmap represents one gene. (C) Genomic structure of cPcdh genes on mouse chromosome 18. Deoxyribonuclease (DNase) I hypersensitive sites (HS) are indicated as black arrows. (D) H3K36me3 levels at three HS elements in E13.5 control and Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices. The green frame shows the HS position and size. (E) ChIP-qPCR analyses showing DNMT3A/B binding to the HS region and promoters of cPcdh locus in E13.5 dorsal cortices. Quantification of enrichment was displayed as fold enrichment over immunoglobulin G (IgG) controls (n = 3 animals for each genotype). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. Data are represented as means ± SEM. Scale bars, 100 μm. CoP, commissural plate.

The H3K36me3 methyltransferase activity of SETD2 is required for the transcription of cPcdh

We then examined whether recovering SETD2-mediated H3K36me3 could restore the expression of cPcdh in cortical neurons. To this end, we engineered three human SETD2-expressing constructs including SETD2FL (wild-type SETD2), SETD2∆SET (methyltransferase deleted), and SETD2L1815W (a point mutation identified in a patient with the Sotos-like syndrome) (19, 20). These SETD2-expressing constructs were individually transfected into SETD2-knockout 293T (293TSETD2-KO) cells in which almost no H3K36me3 modification could be detected. Results showed only the expression of SETD2FL but not SETD2∆SET or SETD2L1815W could restore the H3K36me3 modification in 293TSETD2-KO cells (Fig. 6A and fig. S9, A and B).

Fig. 6. The H3K36me3 methyltransferase activity of SETD2 is required for the transcription activation of cPcdh.

(A) Western blots for 293TSETD2-KO cells transduced with pCIG (vector), the full-length human SETD2 (SETD2FL), the SET domain–deleted human SETD2 (SETD2∆SET), and a point mutation of human SETD2 (SETD2L1815W), and 293T cells transduced with pCIG as the control. Histone H3 is used as loading control. (B) Schematic overview of the in utero electroporation (IUE) strategy for Setd2fl/fl embryos. Animals were euthanized and analyzed at E18.5. (C) Schematic diagram of experimental setup for measuring genes expressions in electroporated cortical cells. FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; cDNA, complementary DNA. (D) qRT-PCR analyses on sorted EGFP+ cells from electroporated E18.5 cortices. Four embryos used for pCAG-Cre-IRES-EGFP, pCAG-Cre-IRES-EGFP/pCAG-SETD2FL and pCAG-Cre-IRES-EGFP/pCAG-SETD2∆SET IUE. Three embryos use for pCAG-Cre-IRES-EGFP/pCAG-SETD2L1815W IUE. Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. (E) Working model. Histone H3 trimethylation at lysine-36 mediated by SETD2 is required for expression of cPcdh genes, cortical area patterning, proper establishment of corticothalamic circuits, and subsequent social behaviors. Data are represented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

To investigate whether Setd2 is sufficient to maintain the expression of cPcdh via its trimethyltransferase activity, we electroporated the E14.5 Setd2fl/fl cortices with plasmids expressing the Cre recombinase to ablate Setd2, with transduced cells coexpressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) for cell sorting. In parallel, one of the three SETD2-expressing constructs was coelectroporated (Fig. 6B). Sorted cells were then subjected to qRT-PCR for measuring expression levels of cPcdh (Fig. 6C). Results showed only expressing SETD2FL, but not SETD2∆SET or SETD2L1815W, could rescue the expression of cPcdh in Setd2-KO cortical cells (Fig. 6D). Collectively, SETD2 maintains the expression of cPcdh through its trimethyltransferase activity on H3K36, and the Sotos-like syndrome–associated SETD2L1815W is devoid of trimethyltransferase activity, hence failing to maintain the expression of cPcdh in cortical neurons.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we unveiled that knockout of Setd2 in the neocortex causes defects in social interaction, motor learning, and spatial memory in mice, recapitulating impaired social behaviors and intellectual disability found in patients with the Sotos-like syndrome bearing frameshift, nonsense, or missense mutations of SETD2 (19, 20, 47–49). We further revealed that SETD2 is required for proper area patterning of the cerebral cortex and the formation of corticothalamic-cortical circuits. SETD2 maintains the expressions of cPcdh in an H3K36me3 methyltransferase–dependent manner (Fig. 6E).

Cortical layer formation and area patterning are precisely coordinated to ensure construction of functional cytoarchitecture and establishment of cognitive and social behaviors (50). Area and neuronal identities of the neocortex are specified at both progenitor and neuronal levels (51). Although Setd2 and H3K36me3 were broadly distributed in developing neocortex, they seem to have minimal roles in maintaining the progenitor pool. Nonetheless, defects of cortical arealization and aberrant corticothalamic-cortical circuits were salient in Setd2Emx1-cKO mice. While distributions of several layer-specific markers (SATB2, CTIP2, and FOXP2) were not changed in Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices, dysregulated cytoarchitecture in the lateral superficial layers and aberrant expression of Lmo4 and Cad8 were prominent, pointing to compromised neuronal identities upon Setd2 loss. Notably, the expression of Rorβ, a marker for layer IV projection neurons, was remarkably reduced in both Setd2Emx1-cKO and Pcdhαβγ+/− mice, suggesting that layer IV–specific characteristics were impaired. Similarly, in Pcdh20 knockdown and Pcdh10 knockout mice, Rorβ-positive cells were markedly decreased and layer IV neurons were ectopically positioned (52). These findings further stressed the causal role of cPcdh in refining neuronal identities in the developing neocortex. Single-cell transcriptome analysis would offer molecular insights into potential changes of neuronal identities upon loss of Setd2.

Correct corticothalamic-cortical connections require proper cytoarchitectural organization and area patterning of the neocortex (9). For example, M1 and S1 normally receive thalamocortical axon inputs from the VL and VP of the thalamus, respectively, that terminate in layer IV. However, the anterograde labeling of VL and VP revealed that in the absence of Setd2, this precise thalamocortical wiring was disrupted. Hence, changes of areal and neuronal identities in Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices could aberrantly direct circuit connections between neocortex and thalamus, which are probably the structural basis for abnormal behaviors. Moreover, patterning defects in Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices were not due to altered expression of patterning TFs. Overall, these data highlight that SETD2 is a pivotal epigenetic modifier in specifying neuronal identity, shaping cortical area, and establishing proper neural connectivity.

Neurodevelopment is regulated by diverse histone methylation mechanisms to ensure proper operation of gene regulatory networks (53). The stochastic expression of variable cell surface proteins, including cPcdh, is essential for defining individual neuronal identity in the brain. Members of the Pcdh adhesion molecules have been implicated in multiple aspects of neural circuit formation, including axon outgrowth and targeting, dendrite arborization, as well as synaptic formation and plasticity (54). Moreover, epigenetic dysregulations of cPcdh are increasingly found in a wide variety of neurological and neurodevelopmental disorders including ASD (55). Multiple cis-elements are embedded in the cPcdh loci, including the deoxyribonuclease (DNase) I hypersensitive site (HS) elements and oriented CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) binding sites. Accordingly, epigenetic status at these cis-elements, such as DNA methylation and CTCF/cohesin-mediated DNA looping, is required for the proper expression of cPcdh in neurons (56, 57). The deletion of essential HS elements (HS5-1, 16, 17, 17′, 18, 19, and 20) could markedly decrease the expression of specific cPcdh isoforms (58). DNMT3B can associate with H3K36me3 in gene bodies to prevent spurious transcription (44). Here, we emphasized the transcription regulations of cPcdh by SETD2-mediated H3K36me3 modification and revealed enhanced association of DNMT3A/B with some HS elements of the Setd2Emx1-cKO genome, which might facilitate the establishment of CpG methylation. Increased cytosine methylation would reduce the binding of CTCF to DNA, thereby hampering the formation of CTCF-dependent topologically associated domain and leading to decreased expression of cPcdh (59, 60). Barrel structures are lost in the somatosensory cortex of CTCF-cKO and HS16-20 deletion brains (58, 61), which is coincident with observations in Setd2Emx1-cKO cortices. In summary, Setd2 governs cortical development partially in a cPcdh-dependent fashion, which provides insights into roles of histone modification and DNA methylation in controlling gene expression.

A missense variant SETD2L1815W was identified using Sanger sequencing in a patient with Sotos-like syndrome (20). We notably unveiled that the SETD2L1815W could abolish SETD2’s trimethyltransferase activity on H3K36, thus failing to rescue the diminished expression of cPcdh in Setd2-depleted neural cells. Intriguingly, the SETD2L1815W mutation resides outside the SET methyltransferase domain, which provides novel hints regarding histone modification mechanisms mediated by SETD2. Notably, the SETD2 mutations identified in Soto-like patients are heterozygous, whereas homozygous Setd2 mutants were used in the current study to get an explicit understanding of its roles in cortical development and social behaviors. It is possible that heterozygous, mutated SETD2 in Soto-like patients might have dominant-negative effects, which could be validated in corresponding point mutation mice.

In summary, our study advances the understanding of histone methylation in neurodevelopment and the Sotos-like syndrome by revealing previously unknown functions of SETD2, the trimethyltransferase for H3K36, in maintaining cPcdh expression, patterning cortical areas, and establishing neural connectivity, as well as in regulating cognitive, motor learning, and social behaviors. These previously unidentified findings bring molecular insights into the pathogenesis and treatment of patients with Sotos-like and ASD-related disorders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and genotyping

All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Ethical Committee at Wuhan University. C57BL/6 background mice used in this study were kept in a 12-hour light/dark cycle, with water and food ad libitum. Mice with conditional deletion of Setd2 were obtained by, first, crossing Setd2fl/fl (generated by Applied StemCell) females with Emx1-Cre (the Jackson Laboratories, stock number 005628) or Nestin-Cre males (the Jackson Laboratories, stock number 003771). Emx1-Cre; Setd2fl/+ (Setd2Emx1-het) or Nestin-Cre; Setd2fl/+ males were crossed with Setd2fl/fl females to obtain cKO mice (Setd2Emx1-cKO or Setd2Nestin-cKO). Setd2fl/+ and Setd2fl/fl were phenotypically indistinguishable from each other and used as controls. Pcdhαβγ+/− mice were generated in the Shanghai Model Organisms Center Inc. The primer set forward 5′-gatttggaggacatgcacaagtcatgtacaag-3′/reverse 5′-tgctttgggggaaagctgaactgaagga-3′/reverse 5′-tatcttttctcggctggtgacgaaatgaagc-3′ was used for Pcdhαβγ heterozygous mice genotyping. The primer set forward 5′-agctgtgagtcactgattc-3′/reverse 5′-atcactgagtctaagaacgg-3′ was used for Setd2 floxed mice genotyping, and band sizes for Setd2fl/+ mice are 211 base pairs (bp) (wild-type allele) and 266 bp (targeted allele with 5′ loxP). Forward 5′-cctgttacgtatagccgaaa-3′/reverse 5′-cttagcgccgtaaatcaatc-3′ was used for Emx1-Cre and Nestin-Cre genotyping with a band size of 319 bp.

Tissue fixation and sectioning

The pregnant dam was anesthetized with 0.7% (w/v) pentobarbital sodium (105 mg/kg of body weight) in 0.9% sodium chloride. Embryos were sequentially removed from the uterus. The brains of embryos were dissected in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at 4°C. For P0, P7, and adult mice, mice were anesthetized with 0.7% (w/v) pentobarbital sodium solution followed by transcardiac perfusion with 4% PFA in PBS (P0, 5 ml; P7, 10 ml; adult, 30 ml). Brains were dissected and postfixed in 4% PFA overnight at 4°C. The next day, brains were dehydrated in 20% (w/v) sucrose overnight at 4°C. Flattened cortices were performed as described (9). Perfused brains were dissected and cut along the midline. Subcortical, midbrain, and hippocampal structures were removed under a dissecting microscope, leaving a hollow hemisphere of the cortex. The cortex was flattened between glass slides with 1.1-mm spacers and postfixed overnight with 4% PFA at 4°C, followed by dehydration overnight in 20% sucrose at 4°C. For sectioning, brains were embedded in Tissue-Tek® O.C.T. Compound (SAKURA) and cut at 40 μm for P7 tangential sections, 20 μm for adult brains, and 14 μm for other stages with a cryostat (Leica CM1950).

In situ hybridization

Sections were dried in a hybridization oven at 50°C for 15 min and fixed in 4% PFA for 20 min at room temperature, followed by permeabilization in proteinase K (2 μg/ml) in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Before hybridization, sections were acylated in 0.25% acetic anhydride for 10 min. Then, sections were incubated with a digoxigenin-labeled probe diluted (0.2 ng/μl) in hybridization buffer [50% deionized formamide, 5× SSC, 5× Denhart’s, transfer RNA (tRNA) (250 μg/ml), and herring sperm DNA (500 μg/ml)] under coverslips in a hybridization oven overnight at 65°C. The next day, sections were washed four times for 80 min in 0.1× SSC at 65°C. Subsequently, they were treated with ribonuclease (RNase) A (20 μg/ml) for 20 min at 37°C and then blocked for 3.5 hours at room temperature in 10% normal sheep serum. Slides were incubated with 1:5000 dilution of Anti-Digoxigenin-AP, Fab fragments from sheep (Roche) overnight at 4°C. BCIP/NBT (bromochloroindolyl phosphate/nitro blue tetrazolium) (Roche) was used as the color-developing agent. ISH primers used are listed in table S1.

Mice behavior tests

We used 9- to 12-week-old age-matched male mice for behavioral tests. Mice were housed (three to five animals per cage) in standard filter-top cages with access to water and rodent chow at all times, maintained on a 12:12-hour light/dark cycle (09:00 to 21:00–hours lighting) at 22°C, with relative humidity of 50 to 60%. All behavioral assays were done blind to genotypes.

Morris water maze

Mice were introduced into a stainless, water-filled circular tank, which is 122 cm in diameter and 51 cm in height with nonreflective interior surfaces and ample visual cues. Two principal axes were drawn on the floor of the tank, each line bisecting the maze perpendicular to one another to create an imaginary “+.” The end of each line demarcates four cardinal points: north, south, east, and west. To enhance the signal-to-noise ratio, the tank was filled with water colored with powdered milk. A 10-cm circular plexiglass platform was submerged 1 cm below the surface of the water in middle of the southwest quadrant. Mice started the task at fixed points, varied by day of testing (62). Four trials were performed per mouse per day with 20-min intervals for 7 days. Each trial lasted 1 min and ended when the mouse climbed onto and remained on the hidden platform for 10 s. The mouse was given 20 s of rest on the platform during the intertrial interval. The time taken by the mouse to reach the platform was recorded as its latency. Times for four trials were averaged and recorded as a result for each mouse. On day 8, the mouse was subjected to a single 60-s probe trial without a platform to test memory retention. The mouse started the trial from northeast, the number of platform crossings was counted, and the swimming path was recorded and analyzed using the EthoVision XT 13 (Noldus).

Three-chamber test for social interaction and novelty behavior

A transparent apparatus made using acrylic resin was used to evaluate social interaction and novelty behavior. The sociability task apparatus has three chambers, each 40 cm long and 30 cm wide and separated evenly by walls with two retractable doors (3 cm by 5 cm each), allowing access to each location of the cage. Before the test, mice were habituated in the center chamber and allowed to freely explore all chambers for 10 min. After the habituation period was complete, the test mouse was placed in the center chamber, and an unfamiliar mouse (stranger I) was placed in one of two chambers, a plastic container with openings that allow for visual and smell recognition but prevents direct contact, leaving the other side chamber empty. The doors were opened and the trace of the test mouse was recorded for 10 min (social interaction test). To measure preference for social novelty, a second unfamiliar mouse (stranger II) was placed in the empty chamber. Doors were opened again and the traces of the test mouse were recorded for an extra 10 min (novelty behavior test). The smells and feces of mice were cleaned with 70% ethanol during intervals.

Rotarod test

The test consists of four trials per day for 7 days with the rotarod (3 cm in diameter) set to accelerate from 4 to 40 rpm over 5 min. The trial started once the mice were placed on the rotarod rotating at 4 rpm in partitioned compartments. The time for each mouse spent on the rotarod was recorded. At least 20 min of recovery time was allowed between trials. The rotarod apparatus was cleaned with 70% ethanol and wiped with paper towels between each trial.

Elevated plus maze test

The elevated plus maze, made of gray polypropylene and elevated about 40 cm above the ground, consists of two open arms and two closed arms (each 9.5 cm wide and 40 cm long). To assess anxiety, the test mouse was placed in the central square facing an open arm and was allowed to explore freely for 5 min. The time spent in the open arm was analyzed with the EthoVision XT 13 (Noldus).

Open-field test

The test mouse was gently placed near the wall side with a length of 50 cm, a width of 50 cm, and a height of 50 cm of open-field arena and allowed to explore freely for 20 min. Only the last 10 min of the movement of the mouse was recorded by a video camera and further analyzed with EthoVision XT 13 (Noldus).

Forced swimming test

For the forced swimming test, the test mouse was placed into a 20-cm-height and 17-cm-diameter glass cylinder filled with water with a depth of 10 cm at 22°C. The test continues for 6 min, and the immobility time of the last 5 min was recorded for further processing.

Tail suspension test

The test mouse was suspended in the middle of a tail suspension box (55-cm height by 60-cm width by 11.5-cm depth) above the ground by its tail. The mouse tail was adhered securely to the suspension bar using adhesive tapes. After 1 min of accommodation, the immobility time was recorded by a video camera and analyzed by EthoVision XT 13 (Noldus).

Self-grooming

The test mouse was placed in a 50-cm-length by 50-cm-width by 50-cm-height open-field arena and allowed to explore freely for 30 min. The time of self-grooming was recorded.

Whisker tracking

Animals were placed into a Perspex rectangular arena (20 cm by 30 cm by 15 cm), which was illuminated by an infrared light-emitting diode array (850 nm; WP-R15030, WORK POWER, China). Mice were filmed overhead using a high-speed video camera (WP-UT050/M, WORK POWER, China) at 500 frames per second with the resolution of 800 × 600 pixels. For both control and Setd2Emx1-cKO mice, sugar pellets were introduced to the arena to promote exploration. For each mouse, 6 to 10 clips were collected opportunistically (by manual trigger) when the animal was locomoting around in the view of the camera, which ranged from 0.5 to 2 s. Videos that lasted more than 1 s were selected and further analyzed by the ARTv2 software (63).

Whole-mount ISH

Whole-mount ISH was performed, as previously reported (64). P7 brains were fixed overnight in 4% PFA and stored in 100% methanol at −80°C. On the day of the experiment, they were rehydrated sequentially in methanol (75, 50, 25%, and PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20) and treated with a 6% hydrogen peroxide solution for 60 min at 4°C. Brains were then treated with proteinase K (20 μg/ml) for 1 hour and rinsed with 10 mM glycine in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20. After that, they were postfixed for 20 min in 4% PFA/0.2% glutaraldehyde. Brains were incubated in hybridization solution [50% deionized formamide, 5× SSC, 20% SDS, tRNA (500 μg/ml), and heparin (50 μg/ml)] for 1 hour at 70°C and then hybridized to riboprobes (0.1 to 0.2 ng/μl) in hybridization solution overnight at 70°C. The next day, brains were washed four times (45 min each) at 70°C with wash solution (50% formamide, 2× SSC, and 1% SDS) and rinsed three times (10 min each) with MABT [0.1 M maleic acid, 150 mM NaCl, and 1% Tween 20 (pH 7.5)]. Brains were then blocked in blocking solution (10% normal sheep serum in MABT) for 3.5 hours and incubated with anti-digoxigenin antibody (1:5000) in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. The next day, brains were washed at least five times for 1 hour each in MABT at room temperature, followed overnight at 4°C. Last, brains were incubated in NTMT [100 mM NaCl, 100 mM tris-HCl (pH 9.5), 50 mM MgCl2, 1% Tween 20, and 2 mM levamisole], and color development reaction was performed by NBT/BCIP solution at room temperature.

Immunohistochemical staining and Nissl staining

Frozen brain sections were pretreated with 0.3% H2O2 for 15 min to deactivate endogenous peroxidase. Sections were blocked with 3% normal sheep serum with 0.1% Tween 20 at room temperature for 2 hours. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti–5-HT antibody (1:1000; ImmunoStar, 20080) diluted in blocking buffer, followed by addition of the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (1:50; VECTASTAIN Elite ABC system, Vector Laboratories). Peroxidase was reacted in 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (5 mg/ml) and 0.075% H2O2 in tris-HCl (pH 7.2). Sections were dehydrated, cleared in xylene, and mounted in neutral balsam. For Nissl staining, sections were stained with 0.25% cresyl violet (Sigma-Aldrich) solution for 15 min at 65°C. Then, sections were decolorized in ethanol for 1 min, dehydrated in ethanol for 5 min, cleared in xylene for 10 min, and mounted in neutral balsam.

Immunofluorescence

Sections were dried at room temperature and incubated for 25 min in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95°C. For BrdU staining, sections were treated with 2 N HCl for 30 min at room temperature. Sections were then blocked in 3% normal sheep serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS (blocking buffer) for 1 hour at room temperature. Then, sections were incubated in primary antibodies [rat anti-CTIP2 (1:500; Abcam, ab18465), mouse anti-SATB2 (1:500; Abcam, ab51502), rabbit anti-CUX1 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-13024), mouse anti-FOXP2 (1:250; Sigma-Aldrich, AMAB91361), rabbit anti-H3K36me3 (1:100; Abcam, ab9050), rabbit anti–cleaved Casp3 (1:100; Cell Signaling Technology, 9664S), rabbit anti-TBR2 (1:1000; Abcam, ab23345), and rat anti-BrdU (1:500; Abcam, ab6326)] in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. After three times of rinsing in PBS, sections were incubated in secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-mouse, Alexa Fluor 555–conjugated anti-mouse, Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-rat, Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-rabbit, and Alexa Fluor 555–conjugated anti-rabbit; Thermo Fisher Scientific; 1:1000) for 1 hour at room temperature. Nuclei were labeled by incubation in PBS containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (0.1 μg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich), and samples were mounted in ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

AAV anterograde tracer

Both AAV-mCherry and AAV-EYFP viruses (4.70 × 1012 vector genomes/ml) were purchased from BrainVTA. The AAV-mCherry construct contains the following elements: two inverted terminal repeats, an elongation factor 1 α promoter, the coding sequence for mCherry, the woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element, and a SV40 pA signal. The AAV-EYFP construct was generated by replacing the mCherry coding sequence in AAV-EYFP with the coding sequence for mCherry. Both constructs were packaged and serotyped with the AAV2/9 capsid protein.

Stereotactic injection

Adult mice were used for anterograde monosynaptic neuronal tracing. Briefly, the mouse was anesthetized with 0.7% (w/v) pentobarbital sodium (105 mg/kg of body weight) in 0.9% sodium chloride via an intraperitoneal injection. Then, the mouse was placed into the cotton-padded stereotactic apparatus (RWD Life Science) with the front teeth latched onto the anterior clamp. The head was shaved using an electric razor and was fully stabilized by inserting the ear bars into the ear canal. After that, the surgical area was cleaned thoroughly using a cotton swab that was dipped in 70% ethyl alcohol. An incision was made vertically down the midline of the mouse’s head using the scalpel. Once the bregma is visualized, blood covering the surface of the skull was gently removed with a sterile cotton tip. A syringe filled with viral particle was placed in the stereotactic apparatus (QSI, Stoelting). The intersection of bregma and the interaural line was set as zero. One hundred nanoliters of virus was infused into the hemisphere in reference from bregma: −1.17 mm medial/lateral, −1.06 mm anterior/posterior, and −3.39 mm dorsal/ventral for the ventrolateral nucleus (VL); −1.62 mm medial/lateral, −1.82 mm anterior/posterior, and −3.50 mm dorsal/ventral for ventral posteromedial nucleus (VPM); −1.44 mm medial/lateral, +1.31 mm anterior/posterior, and −1.30 mm dorsal/ventral for M1; and −2.04 mm medial/lateral, −0.50 mm anterior/posterior, and −1.17 mm dorsal/ventral for S1 at a rate of 20 nl/min. The syringe was kept inside for 10 more minutes once the injection is finished to ensure that residual virus was fully absorbed. The skin was sutured gently to close the incision. Three weeks (injection sites at M1 and S1) or 4 weeks (injection sites at VPM and VL) later, mice were euthanized for brain processing.

RNA isolation and RT

RNA isolation was performed using the RNAiso Plus (TAKARA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Tissues or cells were homogenized using a glass Teflon in 1 ml or 500 μl of RNAiso Plus reagent on ice, and phase separation was achieved with 200 or 100 μl of chloroform. After centrifugation at 12,000g for 15 min at 4°C, RNA was precipitated by mixing aqueous phase with equal volumes of isopropyl alcohol and 0.5 μl of glycogen (20 mg/ml). Precipitation was dissolved in DNase/RNase-free water (not diethylpyrocarbonate treated; Ambion). One microgram of total RNA was converted to complementary DNA (cDNA) using Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus reverse transcriptase (TAKARA) under standard conditions with oligo(dT) or random hexamer primers and Recombinant RNase Inhibitor (TAKARA). Then, the cDNA was subjected to qRT-PCR using the SYBR Green assay with 2× SYBR Green qPCR master mix (Bimake). Thermal profile was 95°C for 5 min and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 20 s. Gapdh was used as endogenous control genes. Relative expression level for target genes was normalized by the Ct value of Gapdh using a 2−ΔΔCt relative quantification method. Reactions were run on a CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). The primers used are listed in table S2.

RNA-seq library construction

Total RNA was extracted, as described above. The concentration and quality of RNA were measured with NanoDrop 2000c (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies), respectively. RNA-seq libraries were constructed by the NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, no. E7775). Briefly, mRNA was extracted by poly-A selected with magnetic beads with poly-T and transformed into cDNA by first- and second-strand synthesis. Newly synthesized cDNA was purified by AMPure XP beads (1:1) and eluted in 50 μl of nucleotide-free water. RNA-seq libraries were sequenced by the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform with pair-end reads of 150 bp. The sequencing depth was 60 million reads per library.

RNA-seq data processing

All RNA-seq raw fastq data were cleaned by removing the adaptor sequence. Cutadapt (version 1.16; http://cutadapt.readthedocs.io/en/stable/guide.html) was used for this step with the parameters -u 0 -u -30 -U 0 -U -30 -m 30. Cleaned reads were mapped to the mouse reference genome (mm10) using TopHat (version 2.1.1; http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat/index.shtml) with default settings. The gene expression level was calculated by Cufflinks (version 2.2.1; http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/cufflinks) and normalized by fragments per kilobase of bin per million mapped reads. Differentially expressed genes are defined as ones with a false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 0.05. To identify significantly enriched Gene Ontology terms (FDR < 0.05), Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID, version 6.8) was used.

Plasmids

The pCAG-Cre-IRES-EGFP was a gift from Z. Yang. To synthesize the pCAG-SETD2FL, the pCAGGS vector (65) was linearized by digestion with Not I (New England Biolabs). Primers containing 15-bp appendages homologously matching the ends of the linearized vector were used to amplify SETD2FL fragments. After purification using the Universal DNA Purification Kit (TIANGEN), vectors and fragments were mixed and homologously recombined according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit, Vazyme). The pCAG-SETD2∆SET was amplified using primers flanking sequences encoding the AWS-SET-postSET domain (1476 to 1690 amino acids), with the pCAG-SETD2FL as the template. The 3′ overhangs of both primers are complementary to each other for annealing. After that, the PCR product was homologously recombined using the ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit. The pCAG-SETD2L1815W was also generated from the pCAG-SETD2FL. The SETD2L1815W is a missense mutation of SETD2 that converts a UUG codon (leucine) into a UGG codon (tryptophan). A pair of single mutagenic primers was used to amplify pCAG-SETD2L1815W. Then, the PCR templates were digested with Dpn I, and PCR products were transformed into DH5α cells. Positive clones were identified and purified by the EndoFree Maxi Plasmid Kit (TIANGEN).

Cell lines and transfection

293TSETD2-KO cells were generated using the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing. The guide RNA (gRNA) sequence of human SETD2 for CRISPR/Cas9 is 5′-actctgatcgtcgctaccat-3′ (66). Complementary oligonucleotides for the gRNA were annealed and ligated into the single gRNA–expressing plasmid (pGL3-U6, Addgene no. 51133). For 293TSETD2-KO cell line construction, the pGL3-U6-gRNA and Cas9-expressing plasmid (spCas9-BlastR) was transfected into 293T cells by calcium phosphate transfection system. Seventy-two hours after transfection, cells were treated with puromycin (500 ng/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich) and blasticidine S hydrochloride (3 μg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 48 hours. After 3 days, colonies were selected through limited dilution and seeded in 96-well plates. Positive single-cell colonies were validated by genomic PCR and Western blots. For genomic PCR, PCR primers were designed, flanking the gRNA target site, and the size of PCR products is 263 bp. The sequence of primers is listed in table S2. PCR products were sequenced and compared to wild-type SETD2 sequence using SnapGene 3.2.1. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s media (DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich), 10% fetal bovine serum (Lonsera) and 1× penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) according to standard protocol. For routine culturing, cells were passaged every 3 days using 0.25% trypsin (Gibco). The day before transfection, 293T cells (2 × 105 cells per well) were seeded in 12-well plates for 16 hours. One microgram of pCIG (67) was diluted into 100 μl of Opti-MEM medium. Polyethyleneimine (PEI) was added to the plasmids mix with a plasmids:PEI ratio of 1:2, and the mix was incubated for 20 min. Then, the plasmids:PEI mixture was added dropwise to each well. The transfection of pCIG, pCAG-SETD2FL, pCAG-SETD2∆SET, or pCAG-SETD2L1815W in 293TSETD2-KO cells was done parallelly. After 3 days, cells were harvested for Western blots.

Western blot analysis

Cells were washed in cold PBS and collected in 1× SDS loading buffer. Proteins were denatured in a melt bath for 10 min at 95°C. After a short centrifugation at 12,000g, the supernatants of the samples were prepared for electrophoresis. Protein samples were loaded, along with a molecular weight marker (Thermo Fisher Scientific), onto 8 or 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels. Then, samples were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore) with a pore size of 0.45 μm. The membrane was blocked with nonfat milk (10%) in tris-buffered saline containing 0.3% Tween 20 (TBST; pH 7.4) for 1 hour at room temperature. The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-H3K36me3 (1:1000; Abcam, ab9050), rabbit anti-SETD2 (1:1000; LSBio, LS-C332416/71567), rabbit anti-H3 (1:10,000; ABclonal, A2348), and rabbit anti-ACTIN (1:100,000; ABclonal, AC026). After three times of washing with TBST, the membrane was incubated with anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG)–conjugated horseradish peroxidase secondary for 1 hour at room temperature. Signals were detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

In utero electroporation

In utero microinjection and electroporation were performed as described (68). Briefly, after a 2-cm laparotomy on deeply anesthetized pregnant females, embryos were carefully pulled out using ring forceps through the incision and placed on sterile and irrigated drape. For knockout experiments, pCAG-Cre-IRES-EGFP (2 μg/ul) containing 0.05% Fast Green (Sigma-Aldrich) was injected into the lateral ventricle of E14.5 embryos using a pulled borosilicate needle (WPI). For gain-of-function experiments, pCAG-Cre-IRES-EGFP with pCAG-SETD2FL, pCAG-SETD2∆SET, or pCAG-SETD2L1815W (2 μg/μl each) containing 0.05% Fast Green were coinjected. The electroporation was performed on heads using a 5-mm forceps-like electrodes (BEX) connected to an electroporator (CUY21VIVO-SQ, BEX) with the following parameters: 36 V, 50-ms duration at 1-s intervals for five times. Then, uteri were reallocated in the abdominal cavity, and both peritoneum and abdominal skin were sewed with surgical sutures. The whole procedure was completed within 30 min. Mice were warmed on a heating pad until they woke up and were given analgesia treatment (ibuprofen) in drinking water.

Preparation of single-cell suspension

The pregnant dam was anesthetized with 0.7% (w/v) pentobarbital sodium, and electroporated embryos were dissected for further processing. Cortices were cut into small pieces using ultrafine spring microscissors, followed by incubating with prewarmed papain–containing enzyme mix: 5 ml of DMEM/F12 (Gibco), 100 U of papain (Worthington), 1× N-Acetyl-L-cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich), and 30 μl of DNase I (4 mg/ml) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. Samples were dissociated by gently pipetting up and down three times per 10 min to prepare single-cell suspension, followed by centrifugation at 300g for 3 min and resuspension in 1 ml of PBS.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

Single-cell suspension was filtered through a 40-μm nylon mesh before fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). The BD FACSAria III was used for FACS. For each experiment, 10,000 cells from untreated cortices were used to set the voltage parameters and all gates. Live and single cells were identified on the basis of the size and physical differences of cells using the forward scatter/side scatter plot and then the side scatter height (H)/side scatter area (A) plot. The gated population was then analyzed and sorted according to the EGFP fluorescence and detected by a 488-nm laser and photomultiplier tubes. About 5000 cells were sorted and stored in 500 μl of TRIzol reagent at −80°C for RNA extraction.

Primer-specific RT, preamplification, and real-time qPCR

Primer-specific RT and preamplification were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions (single-cell sequence specific amplification kit, Vazyme). Briefly, individual primer sets were pooled to a final concentration of 0.1 μM for each primer. Approximately 10 ng of total RNA was added into the RT-PreAmp Master Mix (2.5 μl of reaction mix, 0.5 μl of primer pool, 0.1 μl of RT/Taq enzyme, and 1.9 μl of nuclease-free water) in a 0.5-ml tube. After brief centrifugation at 4°C, the mix was immediately subjected to sequence-specific RT at 50°C for 60 min. Then, inactivation of the reverse transcriptase and activation of the Taq polymerase were achieved by heating to 95°C for 3 min. Subsequently, in the same tube, cDNAs went through 11 to 20 cycles of sequence-specific amplification by denaturing at 95°C for 15 s, annealing, and elongation at 60°C for 15 min. Then, the cDNA was diluted by 1/50 and subjected to qRT-PCR, as described above. Primers used are listed in table S2.

ChIP and ChIP-qPCR assay

For each experiment, single-cell suspensions from E13.5 dorsal cortices were collected, as described above. Cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and then quenched with 0.125 M glycine for 5 min. Cross-linked samples were then rinsed in PBS twice, and harvested in ice-cold IP buffer [100 mM NaCl, 50 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.1), 5 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.02% NaN3, 0.5% SDS, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride], followed by sonication in a Bioruptor Pico (Diagenode) at a setting of “30 s on/30 s off, 30 cycles” at 4°C. Twenty microliters of aliquot was taken for checking the efficiency of sonication. Thirty microliters of lysate (3%) was kept to quantify DNA before immunoprecipitation (input). Immunoprecipitation was performed overnight at 4°C on a rotating wheel with sheared chromatin and indicated antibodies: 3 μg of rabbit anti-H3K36me3 antibody (Abcam, ab9050), 4 μg of rabbit anti-DNMT3A antibody (Abcam, ab2850), 4 μg of rabbit anti-DNMT3B antibody (Abcam, ab122932), and 4 μg of control IgG antibody (ABclonal, AC005). The next day, immunocomplexes were incubated with 50 μl of Protein G Sepharose beads for 4 hours at 4°C, followed by washing three times with wash buffer I [20 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.1% SDS] and once with wash buffer II [20 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.1% SDS]. Protein-DNA complexes were decross-linked in 120 μl of elution buffer (1% SDS and 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate) by shaking at 65°C for 3 hours. The elution was incubated overnight at 65°C with 2 μl of proteinase K (20 mg/ml) (Sangon Biotech) and 2 μl of RNase A (10 mg/ml) (TAKARA). DNA extraction, precipitation, and resuspension were performed using a DNA purification kit (QIAGEN). For ChIP-qPCR, the cDNA was subjected to real-time qPCR using a CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Primers used are listed in table S2.

ChIP-seq library construction

ChIP-seq libraries were constructed by the StepWise DNA Lib Prep Kit for Illumina (ABclonal, RK20202). For each sample, 40 μl of purified ChIP DNA (about 300 pg) was end-repaired by dA tailing, followed by adaptor ligation with the Full DNA Adapter Kit for Illumina Set_A (ABclonal, RK20282). Each adaptor was marked with an index of 6 bp, which can be recognized after mixing different samples together. Adaptor-ligated ChIP DNA was purified by AMPure XP beads (1:1) and then used as template for 16 cycles of PCR amplification. Amplified ChIP DNA was purified again using AMPure XP beads (1:1) in 22 μl of low-EDTA TE buffer. For multiplex sequencing, libraries with different index were mixed together with equal molar quantities by considering appropriate sequencing depth (20 million reads per library). Libraries were sequenced by the Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform with pair-end reads of 150 bp.

ChIP-seq data processing

All ChIP-seq raw fastq data were removed of adaptor sequence, as the same way of RNA-seq data processing. Cutadapt (version 1.16; http://cutadapt.readthedocs.io/en/stable/guide.html) was used for this step with the parameters -u 0 -u -30 -U 0 -U -30 -m 30. Cleaned reads were aligned to the mouse reference genome (mm10) using BWA (version 0.7.15; http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net) with default settings. Peaks calling was finished by MACS2 (version 2.1.1; https://github.com/taoliu/MACS) with the parameters --nomodel --keep-dup all -p 1E-10 --broad --broad-cut- off 1E-10 --extsize 147. bedGraphToBigWig (UCSC-tools) was used to generate the bigWIG files displayed on browser tracks throughout the manuscript.

Image acquisition

Bright-field images were taken using Leica Aperio VERSA 8 and Aperio ImageScope software (Leica). Confocal images were acquired using Zeiss LSM 880 with Airyscan with a 10× objective at 1024 × 1024 pixel resolution. For images taken as tile scans, the stitching was performed using the ZEN software. Brightness and contrast were adjusted, and images were merged using Adobe Photoshop CC (version 20.0.0). Schematics were drawn using Adobe Illustrator CC (version 23.0). Image capturing and processing for controls and mutants were done in the same parameters.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Position-matched sections from control and Setd2Emx1-cKO brains (n ≥ 3 mice for each genotype) were used for further quantification. To quantify the intensity of layer-specific or area-specific distributed ISH signals and AAV-EGFP–labeled fluorescence of cortex, the images were binned against dorsal-ventral or rostral-caudal position. A plot of normalized average signal intensity with SEM across those regions was generated using ImageJ. To quantify the intensity of ISH signals of Pax6, Coup-TF1, Emx2, Sp8, Pcdhα 4, Pcdhβ 17, and Pcdhγ c4 in cortices, ImageJ was used as previously reported (8). Briefly, normalized integrated density = integrated density of selected area − area of selected × mean gray value of background readings. For 5-HT staining, the area and length of fixed regions were measured using ImageJ. For immunofluorescence (except for cleaved Casp3 immunofluorescence staining), more than 200 cells were counted for each sample using Image-Pro Plus software (version 6.0.0.260). Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 8.0.2). Data analyzed by unpaired two-tailed t test were pretested for equal variance by F tests. Unpaired Student’s t tests (two-tailed) were chosen when the data were distributed with equal variance. For normally distributed data with unequal variance, an unpaired t test with Welch’s correction was used. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used for multiple-group comparison. Significant difference is indicated by a P value less than 0.05 (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001). No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes, but our sample sizes are similar to those reported in previous publications. Experiments were not randomized. Investigators were blinded to the animal genotype during tissue section staining, image acquisition, and image analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Z. Yang and Q. Wu for reagents and technical support. Funding: Y.Zhou was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFA0800700), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 31970770 and 31671418), the Hubei Natural Science Foundation (2018CFA016), the Medical Science Advancement Program (Basic Medical Sciences) of Wuhan University (TFJC2018005), and the State Key Laboratory Special Fund 2060204. M.W. was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2016YFA0502100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 81972647 and 31771503), and Science and Technology Department of Hubei Province of China (2017ACA095). Y.L. was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31970676). Author contributions: Y.Zhou and M.W. conceived and designed the project. L.X. and Y.Zheng performed and analyzed data. X.W., Y.L., D.H., X.L., and A.W. contributed to ChIP-seq, FACS, construction of knockout cell lines, and in utero electroporation. Q.L., Z.L., and S.W. conducted bioinformatics analysis. F.X. assisted with neural circuit–tracing experiments. Y.Zhou and L.X. wrote the paper. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: Raw and processed datasets generated during the study are available in the GEO repository using the accession numbers GSE138153 and GSE137622. All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/7/1/eaba1180/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.O’Leary D. D., Sahara S., Genetic regulation of arealization of the neocortex. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 18, 90–100 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Leary D. D., Chou S.-J., Sahara S., Area patterning of the mammalian cortex. Neuron 56, 252–269 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alfano C., Studer M., Neocortical arealization: Evolution, mechanisms, and open questions. Dev. Neurobiol. 73, 411–447 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joshi P. S., Molyneaux B. J., Feng L., Xie X., Macklis J. D., Gan L., Bhlhb5 regulates the postmitotic acquisition of area identities in layers II-V of the developing neocortex. Neuron 60, 258–272 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cederquist G. Y., Azim E., Shnider S. J., Padmanabhan H., Macklis J. D., Lmo4 establishes rostral motor cortex projection neuron subtype diversity. J. Neurosci. 33, 6321–6332 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou S.-J., Perez-Garcia C. G., Kroll T. T., O’Leary D. D. M., Lhx2 specifies regional fate in Emx1 lineage of telencephalic progenitors generating cerebral cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 1381–1389 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedogni F., Hodge R. D., Elsen G. E., Nelson B. R., Daza R. A., Beyer R. P., Bammler T. K., Rubenstein J. L., Hevner R. F., Tbr1 regulates regional and laminar identity of postmitotic neurons in developing neocortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 13129–13134 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golonzhka O., Nord A., Tang P. L., Lindtner S., Ypsilanti A. R., Ferretti E., Visel A., Selleri L., Rubenstein J. L., Pbx regulates patterning of the cerebral cortex in progenitors and postmitotic neurons. Neuron 88, 1192–1207 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greig L. C., Woodworth M. B., Greppi C., Macklis J. D., Ctip1 controls acquisition of sensory area identity and establishment of sensory input fields in the developing neocortex. Neuron 90, 261–277 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jambhekar A., Dhall A., Shi Y., Roles and regulation of histone methylation in animal development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 625–641 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byrd K. N., Shearn A., ASH1, a Drosophila trithorax group protein, is required for methylation of lysine 4 residues on histone H3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 11535–11540 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narayanan R., Pirouz M., Kerimoglu C., Pham L., Wagener R. J., Kiszka K. A., Rosenbusch J., Seong R. H., Kessel M., Fischer A., Stoykova A., Staiger J. F., Tuoc T., Loss of BAF (mSWI/SNF) complexes causes global transcriptional and chromatin state changes in forebrain development. Cell Rep. 13, 1842–1854 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirabayashi Y., Suzki N., Tsuboi M., Endo T. A., Toyoda T., Shinga J., Koseki H., Vidal M., Gotoh Y., Polycomb limits the neurogenic competence of neural precursor cells to promote astrogenic fate transition. Neuron 63, 600–613 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pereira J. D., Sansom S. N., Smith J., Dobenecker M.-W., Tarakhovsky A., Livesey F. J., Ezh2, the histone methyltransferase of PRC2, regulates the balance between self-renewal and differentiation in the cerebral cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 15957–15962 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li W., Shen W., Zhang B., Tian K., Li Y., Mu L., Luo Z., Zhong X., Wu X., Liu Y., Zhou Y., Long non-coding RNA LncKdm2b regulates cortical neuronal differentiation by cis-activating Kdm2b. Protein Cell 11, 161–186 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delgado R. N., Mansky B., Ahanger S. H., Lu C., Andersen R. E., Dou Y., Alvarez-Buylla A., Lim D. A., Maintenance of neural stem cell positional identity by mixed-lineage leukemia 1. Science 368, 48 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amaral D. G., Schumann C. M., Nordahl C. W., Neuroanatomy of autism. Trends Neurosci. 31, 137–145 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanfield A. C., McIntosh A. M., Spencer M. D., Philip R., Gaur S., Lawrie S. M., Towards a neuroanatomy of autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis of structural magnetic resonance imaging studies. Eur. Psychiatry 23, 289–299 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lumish H. S., Wynn J., Devinsky O., Chung W. K., Brief Report: SETD2 mutation in a child with autism, intellectual disabilities and epilepsy. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 3764–3770 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luscan A., Laurendeau I., Malan V., Francannet C., Odent S., Giuliano F., Lacombe D., Touraine R., Vidaud M., Pasmant E., Cormier-Daire V., Mutations in SETD2 cause a novel overgrowth condition. J. Med. Genet. 51, 512–517 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luco R. F., Pan Q., Tominaga K., Blencowe B. J., Pereira-Smith O. M., Misteli T., Regulation of alternative splicing by histone modifications. Science 327, 996–1000 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kizer K. O., Phatnani H. P., Shibata Y., Hall H., Greenleaf A. L., Strahl B. D., A novel domain in Set2 mediates RNA polymerase II interaction and couples histone H3 K36 methylation with transcript elongation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 3305–3316 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carvalho S., Vitor A. C., Sridhara S. C., Martins F. B., Raposo A. C., Desterro J. M., Ferreira J., de Almeida S. F., SETD2 is required for DNA double-strand break repair and activation of the p53-mediated checkpoint. eLife 3, e02482 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu M., Sun X.-J., Zhang Y.-L., Kuang Y., Hu C.-Q., Wu W.-L., Shen S.-H., Du T.-T., Li H., He F., Xiao H.-S., Wang Z.-G., Liu T.-X., Lu H., Huang Q.-H., Chen S.-J., Chen Z., Histone H3 lysine 36 methyltransferase Hypb/Setd2 is required for embryonic vascular remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 2956–2961 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu Q., Xiang Y., Wang Q., Wang L., Brind’Amour J., Bogutz A. B., Zhang Y., Zhang B., Yu G., Xia W., Du Z., Huang C., Ma J., Zheng H., Li Y., Liu C., Walker C. L., Jonasch E., Lefebvre L., Wu M., Lorincz M. C., Li W., Li L., Xie W., SETD2 regulates the maternal epigenome, genomic imprinting and embryonic development. Nat. Genet. 51, 844–856 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mountoufaris G., Chen W. V., Hirabayashi Y., O’Keeffe S., Chevee M., Nwakeze C. L., Polleux F., Maniatis T., Multicluster Pcdh diversity is required for mouse olfactory neural circuit assembly. Science 356, 411–414 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katori S., Hamada S., Noguchi Y., Fukuda E., Yamamoto T., Yamamoto H., Hasegawa S., Yagi T., Protocadherin-α family is required for serotonergic projections to appropriately innervate target brain areas. J. Neurosci. 29, 9137–9147 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasegawa S., Kumagai M., Hagihara M., Nishimaru H., Hirano K., Kaneko R., Okayama A., Hirayama T., Sanbo M., Hirabayashi M., Watanabe M., Hirabayashi T., Yagi T., Distinct and cooperative functions for the Protocadherin-α, -β and -γ clusters in neuronal survival and axon targeting. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 9, 155 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubenstein J. L., Anderson S., Shi L., Miyashita-Lin E., Bulfone A., Hevner R., Genetic control of cortical regionalization and connectivity. Cereb. Cortex 9, 524–532 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakagawa Y., O’Leary D. D. M., Dynamic patterned expression of orphan nuclear receptor genes RORα and RORβ in developing mouse forebrain. Dev. Neurosci. 25, 234–244 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arlotta P., Molyneaux B. J., Chen J., Inoue J., Kominami R., Macklis J. D., Neuronal subtype-specific genes that control corticospinal motor neuron development in vivo. Neuron 45, 207–221 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]