Structure of SARS-CoV-2 spike in complex with ACE2 reveals the mechanism of ACE2 induced spike conformational transitions.

Abstract

The recent outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 pose a global health emergency. The SARS-CoV-2 trimeric spike (S) glycoprotein interacts with the human ACE2 receptor to mediate viral entry into host cells. We report the cryo-EM structures of a tightly closed SARS-CoV-2 S trimer with packed fusion peptide and an ACE2-bound S trimer at 2.7- and 3.8-Å resolution, respectively. Accompanying ACE2 binding to the up receptor-binding domain (RBD), the associated ACE2-RBD exhibits continuous swing motions. Notably, the SARS-CoV-2 S trimer appears much more sensitive to the ACE2 receptor than the SARS-CoV S trimer regarding receptor-triggered transformation from the closed prefusion state to the fusion-prone open state, potentially contributing to the superior infectivity of SARS-CoV-2. We defined the RBD T470-T478 loop and Y505 as viral determinants for specific recognition of SARS-CoV-2 RBD by ACE2. Our findings depict the mechanism of ACE2-induced S trimer conformational transitions from the ground prefusion state toward the postfusion state, facilitating development of anti–SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and therapeutics.

INTRODUCTION

Coronaviruses are a family of large, enveloped, positive-stranded RNA viruses that cause upper respiratory, gastrointestinal, and central nervous system diseases in humans and other animals (1, 2). In the past few decades, newly evolved coronaviruses have posed a global threat to public health, including outbreaks of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in 2002–2003 and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in 2012, which caused thousands of infections, and their mortality rates were about 10.0 and 34.4%, respectively (3). The recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is caused by a novel coronavirus named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). By 29 June 2020, there had been 9,962,193 laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections globally, leading to 498,723 deaths. As of 4 November 2020, there were no approved therapeutics or vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 and other human-infecting coronaviruses.

As in other coronaviruses, the spike (S) glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 is a membrane-fusion machine that mediates receptor recognition and viral entry into cells and is the primary target of the humoral immune response during infection (3, 4). The S protein is a homotrimeric class I fusion protein that forms large protrusions from the virus surface and undergoes a substantial structural rearrangement to fuse the viral membrane with the host-cell membrane once it binds to a host-cell receptor (5, 6). The S protein ectodomain consists of a receptor-binding subunit S1 and a membrane-fusion subunit S2 (4, 7, 8). Two major domains in coronavirus S1 have been identified, including an N-terminal domain (NTD) and a C-terminal domain (CTD) also called receptor-binding domain (RBD). Following the RBD, S1 also contains two subdomains (SD1 and SD2) (7). The S2 contains a variety of motifs, starting with the fusion peptide (FP). The FP is conserved across the viral family and composed of mostly hydrophobic residues, which inserts in the host-cell membrane to trigger the fusion event (4, 9). Previous cryo–electron microscopy (cryo-EM) studies on the stabilized ectodomain of SARS-CoV-2 S protein revealed a closed state of the S trimer with three RBD domains in “down” conformation, and an open state with one RBD in the “up” conformation, corresponding to the receptor-accessible state (7, 8); these two states have also been observed in the recent cryo-EM structures of full-length wild-type S trimer (10) and other stabilization constructs of the ectodomain of S trimer (11, 12). Moreover, the mutation SARS-CoV-2 spike D614G has been reported to promote the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 and enhances viral transmissibility in multiple human cell types, while the underling structural basis remains not fully understood (13–15).

SARS-CoV-2 S and SARS-CoV S share 76% amino acid sequence identity, but they bind the same host-cell receptor—human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (16–18). It is usually considered that for coronavirus, the transition process toward the postfusion conformation is triggered when the S1 subunit binds to a host-cell receptor (19). The available crystal and cryo-EM structures of the RBD domain of SARS-CoV-2 interacting with the extracellular peptidase domain (PD) of ACE2 or full-length ACE2, respectively, provide important information on the RBD-ACE2 interaction interface, revealing that the receptor-binding motif (RBM) within RBD directly interacts with ACE2 (17, 20–22). However, a more complete architecture of ACE2 associating with SARS-CoV-2 trimeric S protein remains unavailable; thus, how ACE2 binding triggers the conformational dynamics and allosteric responses of the fusion machine facilitating transitions toward the postfusion state remains elusive.

Here, we present cryo-EM structures of SARS-CoV-2 S trimer in a tightly closed state with packed FP may represent the ground prefusion state, and the S trimer in complex with the receptor ACE2 (termed SARS-CoV-2 S-ACE2) at 2.7- and 3.8-Å resolution, respectively, in addition to an S trimer structure in the unliganded open state. The tightly closed ground prefusion state with originally dominant population may indicate a conformational masking mechanism of immune evasion for SARS-CoV-2 spike. Our data suggested that there is one RBD in the up conformation and is trapped by ACE2 in the S-ACE2 complex. Notably, ACE2 can greatly shift the conformational landscape of S trimer, and the associated ACE2-RBD exhibits continuous swing motions in the context of the S trimer, resulting in conformational dynamics in S1 subunits. We also provided structural basis of the enhanced infectivity induced by spike D614G mutation and demonstrated the RBM T470-T478 loop and residue Y505 as viral determinants for specific recognition of SARS-CoV-2 RBD by ACE2. Our findings reveal the mechanism of ACE2-induced conformational transitions of S trimer from the ground prefusion state toward the postfusion state, enhance our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and provide important information for the design and optimization of anti–SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and therapeutics.

RESULTS

A tightly closed state of SARS-CoV-2 S trimer

Prefusion stabilized ectodomain trimer of SARS-CoV-2 S glycoprotein was produced from human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293F cells using the strategy also adopted in other studies (fig. S1, A to D) (2, 7, 8, 23–28), and was subjected to cryo-EM single-particle analysis (fig. S2, A to B). Our initial reconstruction suggested a preferred orientation problem associated with the S trimer (highly preferred “side” orientation but lacking tilted top views; fig. S2C), which is also the case for the influenza hemagglutinin trimer (but highly preferred “top” orientation) (29). To overcome this problem, we adopted the recently developed tilt stage strategy in data collection with additional data collected at 30° and 40° tilt angles (29). This allowed us to obtain a cryo-EM structure of SARS-CoV-2 S trimer in a closed state at 2.7-Å resolution (with imposed C3 symmetry, termed S-closed) (Fig. 1A, figs. S2 and S3, and table S1). After overcoming the preferred orientation problem, our S-closed map very well resolved the peripheral edge of the NTD domain and the RBM S469-C488 loop (Fig. 1, A to D), which was less well resolved in the similar stabilized ectodomain trimer structures (7, 8). This enabled us to build an atomic model of the SARS-CoV-2 S trimer (Fig. 1B; fig. S2, F and G; and movie S1).

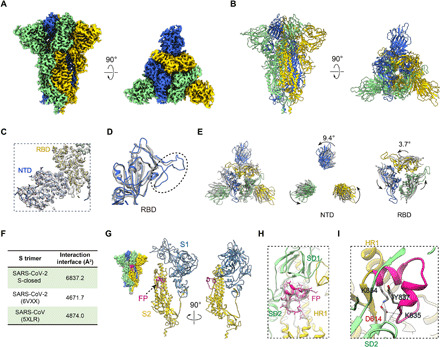

Fig. 1. A tightly closed conformation of SARS-CoV-2 S trimer.

(A and B) Cryo-EM map and model of SARS-CoV-2 S trimer in a tightly closed state, with three protomers shown in different color. (C) Close-up view of the model map fitting in the NTD and RBD regions of the S1 subunit, illustrating that most of the NTD region was well resolved. (D) Overlaid RBD structures of our S-closed (blue) with a cryo-EM structure of SARS-CoV-2 S in closed state (6VXX, gray), illustrating that the RBM S469-C488 loop was captured in our structure (indicated by dotted ellipsoid). (E) Top view of the overlaid structures as in (D) (left) and zoom-in views of specific domains, showing that there is a marked counterclockwise rotation in S1 especially in NTD, resulting in a twisted, tightly closed conformation. (F) Protomer interaction interface analysis by PISA. (G) Location of the captured FP fragment (in deep pink) within the S trimer (left) and one protomer. S1 and S2 subunits are colored steel blue and gold, respectively. (H) Model map fitting for the FP fragment. (I) Close-up view of the interactions between D614 from SD2 and FP, with the hydrogen bonds labeled in dotted lines and the L828-F855 region in FP in deep pink.

Compared with the previous closed-state SARS-CoV-2 S trimer structure (6VXX) (8), our map represents a distinct tightly closed conformation. For instance, the upper portion of the S1 subunit, especially NTD and RBD, depicts a counterclockwise rotation of 9.4° and 3.7°, respectively (Fig. 1E). Accompanying this rotation, there is a slight inward tilt leading the peripheral edge of NTD exhibiting a 12.4-Å inward movement for Cα of T124 (fig. S2H). Collectively, these relative movements twist the complex in a more compact conformation. The average interaction interface between protomers increases from ~4671.7 Å2 in their structure to 6837.2 Å2 in our structure (Fig. 1F). Together, our map represents a tightly closed state of the SARS-CoV-2 S trimer. Furthermore, compared with the closed-state SARS-CoV S trimer structure (30), our S-closed structure also showed a counterclockwise rotation, associating with an RBD inward shift toward the central axis (fig. S4A). As a result, our S-closed structure appears more compact than that of SARS-CoV S trimer (6837.2 Å2 versus 4874.0 Å2 in interaction interface; Fig. 1F). Multibody refinement on S-closed data also showed the most substantial motion in NTD region is along this twisting/untwisting direction (fig. S4B), implying that this motion could be encoded in this dynamic fusion machine. Together, our study revealed a tightly closed conformation of SARS-CoV-2 S trimer, extending the conformational space of this fusion machinery. Of note, during the submission of this manuscript, two cryo-EM studies of a full-length wild-type S trimer (10) and a distinct stabilization construct of the ectodomain of S trimer (11) also reported a tightly closed state of the S trimer with a better-resolved NTD domain as well, substantiating our observations. Moreover, the conformation of our tightly closed state is more comparable to that of the wild-type S trimer prefusion structure [Protein Data Bank (PDB): 6XR8; fig. S4C] (10), implying that our prefusion stabilized ectodomain S-closed structure can very well represent the full-length wild-type S trimer prefusion state.

The tightly closed state with stably packed FP may represent the ground prefusion state of SARS-CoV-2 S trimer

The hydrophobic FP, immediately after the S2′ cleavage site and essential for host-cell membrane fusion, is highly conserved among SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV S proteins (4). Here, our S-closed map enabled us to capture the entire FP of SARS-CoV-2 including the L828-Q853 fragment, which locates on the flank surface of the S trimer, surrounded by HR1 of the S2 subunit from the same protomer, and SD1/SD2 of the S1 subunit from the clockwise neighboring protomer (Fig. 1, G and H). The FP fragment is well ordered, forming two small helices (Y837-G842 and L849-F855) and connecting loops (Fig. 1, G and H). This region was also detected in the recently reported compact closed state (10, 11).

Further interaction analysis revealed that SD2 and HR1 can form hydrogen bonds/salt bridges with the FP fragment, and SD2 plays a key role in this interaction involving six predicted hydrogen bonds/salt bridges (table S2). Noteworthy, among the six SD2-FP interactions, D614 from SD2 contributes to the formation of four hydrogen bonds/salt bridges, mainly through its side-chain atoms, with K835, Y837, and K854 of FP, suggesting that D614 may be essential in the interaction with and stabilization of FP (Fig. 1I, fig. S4D, and table S2). This could be related to the reports suggesting that the D614G mutation of SARS-CoV-2 S enhances viral infectivity (more in Discussion) (31, 32). In line with our observation, the salt bridge between D614 and K854 was also documented in recent reports (10, 12). It appears that before being activated, FP could serve as a linkage that wraps around the neighboring protomers in their S1/S2 interface and simultaneously connects S1 with S2, this way to coordinately lock the S trimer in the tightly closed prefusion state (Fig. 1, G and H). Collectively, our observations lead us to speculate that the dominantly populated compact S-closed structure with inactivated FP may represent the ground prefusion state of the spike protein.

Moreover, we performed multiple rounds of three-dimensional (3D) classification and found that in this dataset, the dominant population of the particles (~94%) is in the tightly closed state and only a minor population (6%) in the open state (fig. S3). Our observations indicate that the open-state S trimer might be intrinsically dynamic and only exists transiently to expose the RBD domain. The dominant population of the SARS-CoV-2 S trimer is in the tightly closed ground prefusion state with inactivated FP and all the RBD domains buried, which may result in “conformational masking” preventing antibody binding and neutralization, similar to that described for HIV-1 envelope (Env) (33, 34), and has also been proposed for SARS-CoV-2 S protein mainly based on biochemical analyses (35). The population distribution of the closed and open states of SARS-CoV-2 S varies among different studies (7, 8), which is reminiscent of observations made with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV S trimers. This observed variation could be potentially due to subtle difference in chemical condition used by different research groups (1, 2, 26, 27, 30, 36).

An architecture of the SARS-CoV-2 S trimer in complex with ACE2

To gain a thorough picture on how the receptor ACE2 binding induces conformational dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 S trimer and triggers transition toward the postfusion state, we determined the cryo-EM structure of SARS-CoV-2 S trimer in complex with human ACE2 PD domain to 3.8-Å resolution (termed SARS-CoV-2 S-ACE2; Fig. 2A and figs. S5, A to E, and S6). Further focused refinements improved the resolution of the S trimer portion of the map to 3.3 Å and the connectivity in the ACE2-RBD portion of the map (figs. S5E and S6). We then built a pseudoatomic model of the complex with combined map information (Fig. 2B). In this dataset, we additionally captured an unliganded S trimer in the open state with one RBD up (resolved to 6.0-Å resolution, termed S-open), but did not detect the closed state (figs. S5, D to F, and S6). We should mention that our biolayer interferometry (BLI) assay revealed a relatively rapid disassociation kinetics between ACE2 and the S trimer (koff = 4.56 × 10−3 s−1; fig. S1E). We thus determined the complex structure in the presence of trace amount of cross-linker glutaraldehyde (Materials and Methods). In addition, we also determined the S-ACE2 complex structure without cross-linker at 5.3-Å resolution, and the two maps are in comparable conformation, suggesting that addition of a cross-linker did not change the conformation of the complex (fig. S5G). We then used the S-ACE2 map at 3.8-Å resolution for a detailed structural analysis.

Fig. 2. The architecture of the SARS-CoV-2 S-ACE2 complex.

(A and B) Cryo-EM map and model of SARS-CoV-2 S-ACE2 complex. We named the RBD up protomer as protomer 1 (light green), and the other two RBD down ones as protomer 2 (royal blue) and protomer 3 (gold). ACE2 was colored in violet red. (C) Side and top views of the overlaid S-open (color) and S-closed (dark gray) structures, showing that in the open process, there is a 71.0° upward/outward rotation of RBD associated with a downward shift of SD1 in protomer 1. (D) Rotations of NTD and CH from the S-closed (gray) to the S-open (in color) state, with the NTD also showing a downward/outward movement (right). (E) Side view of the overlaid S-ACE2 (violet red) and S-open (light green) protomer 1 structures, showing that the angle between the long axis of RBD and the horizontal plane of S trimer reduces from the S-open to the S-ACE2. (F) Top and side views of the overlaid S-ACE2 (violet red) and S-open (color) RBD structures, showing the coordinated movements of RBDs. (G) Protomer interaction interface analysis of S-ACE2 by PISA. (H) Aromatic interactions between the core region of the up RBD-1 (green) and the RBM T470-F490 loop of the neighboring RBD-2 (blue). (I) Overlaid structures of S-ACE2 (gray) and S-closed (color, with the FP fragment in deep pink), indicating a downward shift of SD1 and most of the FP is missing in S-ACE2. Close-up view (right) of the potential clashes between the downward-shifted SD1 β34 and α8 helix of FP. (J) Population shift between the ACE2-unpresented and ACE2-presented S trimer samples.

We first inspected the conformational changes from the closed state to the unliganded open state. In the S-open structure, the only up RBD from protomer 1 (termed RBD-1) showed a 71.0° upward/outward rotation, resulting in an exposed RBM region accessible for ACE2 binding (Fig. 2C). This RBD-1 rotation can be propagated to the underneath SD1, inducing a downward movement of SD1 (Fig. 2C). We also noticed a considerable clockwise rotations of 9.4°, 11.2°, and 12.9° in NTD for protomers 1, 2, and 3, respectively, and counterclockwise rotations in the central helix (CH) of the corresponding S2 subunit, greatly untwisting the S trimer from the tightly closed state (Fig. 2D). Associated with this S1 untwisting, there is a downward/outward movement of NTDs in the scale of ~10 Å (Fig. 2D, right panel). These combined untwisting motions could release the protomer interaction strength, beneficial for the transient raising up of the RBD. Moreover, our local resolution analysis on the S-open map also suggested that other than RBD-1, the consecutive RBD-2 also exhibits considerable intrinsic dynamics (fig. S5D).

Our SARS-CoV-2 S-ACE2 structure revealed that the S trimer binds with one ACE2 through the only up RBD from the transiently open state with one up RBD (more in Discussion), while the other two RBDs remain in the down conformation (Fig. 2, A and B), suggesting that ACE2 binding to SARS-CoV-2 strictly requires the up conformation of RBD. Unlike the observations made with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV S trimers, we did not detect S trimer with two RBD domains up with bound ACE2 (26, 27). Although our S-ACE2 and S-open structures generally resemble each other, especially in the S2 region, there are noticeable differences in the S1 region. Specifically, after ACE2 binding, the up RBD-1 from the S-open state can be pushed tilting downward slightly, with the angle to the horizontal plane of S trimer reduced from 73.2° to 68.6° in the ACE2-bound state (Fig. 2E). This ACE2 binding–induced motion of RBD-1 could be propagated to the neighboring RBD-2 and the consecutive RBD-3 [root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), 1.95 Å; Fig. 2F], collectively disturbing the allosteric network of the fusion machinery. The neighboring protomer interaction interface was reduced from the original ~6837.2 Å2 in the S-closed state to 4898.4 to 5791.2 Å2 in the ACE2-bound state (Fig. 2G). Together, these S1 subunit untwisting and RBD-1 tilting motions could destabilize the prefusion state of S trimer, prepared for the subsequent conformational transitions toward the postfusion state.

Our S-ACE2 structure showed that the core region of the up RBD-1 and the RBM T470-F490 loop of the neighboring RBD-2 could form aromatic interactions with the involvement of Y369/F374 from RBD-1 and F486/Y489 from RBD-2 (Fig. 2H), potentially enhancing interactions between neighboring S1 subunits, beneficial for subsequent simultaneous shedding of S1 subunits. This interaction was not detected in the counterpart of the homologous SARS-CoV S-ACE2 structure, likely due to longer distance between the adjacent up and down RBDs in that structure (1, 27).

It is noteworthy that the originally stably packed FP from protomer 3 surrounded by SD1/SD2 of the neighboring protomer 1 captured in our S-closed structure is now mostly missing in the S-ACE2 structure, which is also the case in the S-open structure. This is mostly caused by the S trimer untwisting motion–induced downward shift of SD1 in the opening process (Fig. 2C). The β34/β37 strands within SD1 shift downward for up to 5.4 Å (Fig. 2I). Consequently, the C590 and T588 from β37 and the connecting loop could clash with Y837 and L841 from the originally packed α8 helix of FP (Fig. 2I), potentially resulting in destabilization and activation of the FP motif from protomer 3. Since the untwisting/downward-shift motions of S1 subunits are allosterically coordinated in the S trimer opening process, the densities corresponding to FPs in protomers 1 and 2 are also missing, indicating a coordinated activation mechanism of FP, which may be one of the key elements prepared for the subsequent fusion of S trimer.

Notably, our data further suggested that the presence of ACE2 could greatly shift the population landscape of S trimer, i.e., from the original 94% closed prefusion state and 6% fusion-prone open state in the absence of ACE2, to 26.2% unliganded open state and 73.8% ACE2-bound open state in the ACE2 present sample (Fig. 2J). Therefore, in the presence of ACE2, the open-state S trimer (although this state only exits transiently with minor population in the absence of ACE2) interacts with ACE2, and this interaction could break the balance between particle populations and greatly shift the S trimer conformational landscape toward the open state, favorable for the receptor binding and transitions toward the postfusion state.

The T470-T478 loop and residue Y505 within RBM play vital roles in the engagement of SARS-CoV-2 spike with host-cell receptor ACE2

The overall ACE2-RBD interaction interface in our S-ACE2 cryo-EM structure is comparable with that of the crystal structures of the RBD domain of SARS-CoV-2 S interacting with the ACE2 PD domain (17, 21), showing that the T470-F490 loop and Q498-Y505 within RBD are key contacting elements (Fig. 3A). Predicted interactions between RBD and ACE2 are listed in table S3. We should mention that the T470-F490 loop can originally be resolved in the S-closed structure but is mostly missing in the S-open structure, indicating that the T470-F490 loop may be activated in the open state. Structural comparison revealed that the conformation of the RBM T470-F490 loop in our SARS-CoV-2 S-ACE2 structure is very distinct from that in the SARS-CoV RBD-ACE2 crystal structure (Fig. 3B) (37), in line with the results from sequence alignment showing that the T470-F490 loop is the most diversified region between SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV S proteins (fig. S7). Still, the local resolution in the RBD/ACE2 portion is not high in our S-ACE2 map due to dynamics in this region; we therefore performed a mutagenesis study to validate our predicted key interaction regions.

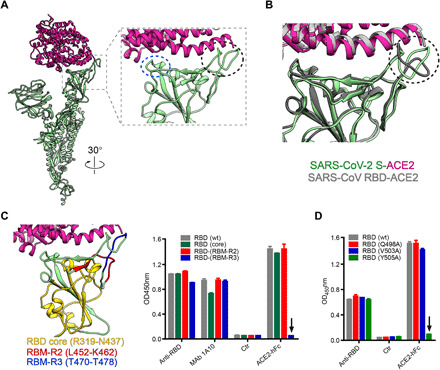

Fig. 3. The T470-T478 loop and residue Y505 within RBM play important roles in the engagement of SARS-CoV-2 spike with receptor ACE2.

(A) The overall view of ACE2 (violet red) bound protomer 1 (light green) from our S-ACE2 structure, and zoom-in view of the interaction interface between ACE2 and RBD, with the key contacting elements T470-F490 loop and Q498-Y505 within RBM highlighted in black ellipsoid and blue ellipsoid, respectively. (B) Superposition of our SARS-CoV-2 S-ACE2 structure with the crystal structure of SARS-CoV RBD-ACE2 (PDB: 2AJF), suggesting that the RBM T470-F490 loop has obvious conformational variations. (C) Binding activities of ACE2-hFc fusion protein to wild-type (wt) and mutant SARS-CoV-2 RBD proteins determined by ELISA. Different structural elements of RBD were colored in the left. Anti-RBD sera and a cross-reactive monoclonal antibody (MAb) 1A10 served as positive controls. Ctr, an irrelevant antibody. The black arrow indicates that mutations in the RBD (RBM-R3) mutant significantly reduced the binding of ACE2-hFc compared with wild-type RBD. (D) Binding of ACE2-hFc fusion protein to wt and single-point mutant forms of SARS-CoV-2 RBD protein measured by ELISA. RBD (Q498A), RBD (V503A), and RBD (Y505A), RBD residues Q498, V503, and Y505 were mutated to Ala, respectively. The downward arrow indicates that the mutation at Y505 completely abolished the binding of ACE2 to RBD protein. OD450, optical density at 450 nm.

To validate the subdomains/residues critical for RBD binding to ACE2, we designed and produced three SARS-CoV-2 RBD mutant proteins, each of which had a single subdomain substituted with the counterpart of SARS-CoV. These RBD mutants were termed RBD-(core), RBD-(RBM-R2), and RBD-(RBM-R3), for which R319 to N437 of the core region, L452 to K462, and T470 to T478 of the RBM from SARS-CoV-2 were substituted, respectively (Fig. 3C and fig. S7). Results from the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) showed that the binding activity of the three RBD mutants toward anti-RBD polyclonal antisera and the cross-reactive monoclonal antibody 1A10 was comparable with that of the wild-type SARS-CoV-2 RBD protein (Fig. 3C), indicating that the mutations did not significantly affect the overall conformation of the RBDs. The mutants RBD-(core) and RBD-(RBM-R2) bound ACE2 as efficiently as the wild-type RBD; in contrast, RBD-(RBM-R3) completely lost ACE2 binding (Fig. 3C). These results pinpoint the RBM-R3 region (residues 470-TEIYQAGST-478) as the critical viral determinant for specific recognition of SARS-CoV-2 RBD by the ACE2 receptor. In addition, we constructed three single-point mutants of SARS-CoV-2 RBD protein, including RBD (Q498A), RBD (V503A), and RBD (Y505A). The results from the ACE2-binding ELISAs showed that single-mutation Y505A was sufficient to completely abolish the binding of ACE2, while the other two mutations did not affect ACE2 binding (Fig. 3D), demonstrating that the residue Y505 of SARS-CoV-2 RBD is a key amino acid required for ACE2 receptor binding. Together, these biochemical analyses substantiate our structural based predictions.

Continuous swing motions of ACE2-RBD in the context of SARS-CoV-2 S trimer

Our S-ACE2 map showed well-defined density for the S trimer region, but relatively lower local resolution in the associated ACE2-RBD region (fig. S5C), suggesting considerable conformational heterogeneity of ACE2-RBD relative to the remaining part of the S trimer. This is in line with the report showing that in SARS-CoV S trimer, the associated ACE2-RBD is relatively dynamic, showing three major conformational states with the angle of ACE2-RBD to the surface of the S trimer at ~51°, 73°, and 111°, respectively (1). To better delineate the conformational space of the ACE2-engaged SARS-CoV-2 S trimer, we performed multibody refinement in Relion 3.1 (Fig. 4, A to C) (38).

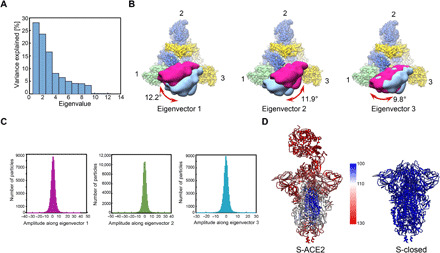

Fig. 4. Conformational dynamics of the S-ACE2 complex determined by multibody refinement.

(A) Contributions of all eigenvectors to the motion in the S-ACE2 complex, with eigenvectors 1 to 3 dominating the contributions. (B) Top view of the map showing the three swing motions of the first three eigenvectors, with S trimer following the color schema as in Fig. 2, and the two extreme locations of ACE2 illustrated in deep pink and light blue densities. The swing angular range and direction are indicated in dark red arrow. (C) Histograms of the amplitudes along the first three eigenvectors. (D) Atomic models of S-ACE2 and S-closed, colored according to the B-factor distribution [ranging from 100 (blue) to 130 Å2 (red)].

Principal components analysis of the movement revealed that approximately 68% of the movement of the S-ACE2 complex can be described by the first three eigenvectors representing swing motions in distinct directions relative to the S trimer (Fig. 4A). Eigenvector 1 describes a swing motion of ACE2-RBD approaching/leaving RBD-2 with the angular range of 12.2°. Eigenvector 2 corresponds to the swing motion of ACE2-RBD toward the original down location of RBD-1 with the angular range of 11.9°, and eigenvector 3 describes the swing motion of ACE2-RBD along the NTD-1 to NTD-3 direction with the angular range of 9.8° (Fig. 4B). Moreover, histograms of the amplitudes along the three eigenvectors are unimodal, indicating that the three swing motions are continuous motions (Fig. 4C). Since the dynamic motions in the S-ACE2 complex are formed by a linear combination of all eigenvectors (39), our data suggested that ACE2-RBD processes on top of the S trimer in a noncorrelated manner. Further, our multibody analysis on the non–cross-linked S-ACE2 dataset showed similar swing motions (fig. S5H), indicating that the presence of a cross-linker did not disturb the mode of ACE2-RBD motions within the S trimer. In addition, compared with the homologous SARS-CoV S-ACE2 complex, which shows discrete movements of ACE2-RBD in one direction (similar to our eigenvector 2 direction) (1), the SARS-CoV-2 S-ACE2 complex exhibits more complex combined continuous swing motions. Moreover, our similar analysis on the up RBD of the S-open data suggested that the up RBD is intrinsically dynamic (fig. S5I), in line with our local resolution data (fig. S5D) and a recent report (40). However, the motion directions of the associated ACE2-RBD in the S-ACE2 complex are divergent to some extent from those of the up RBD in S-open, implying that ACE2 binding could alter the conformational dynamics of the up RBD and potentially the allosteric coordination of S1 subunits. Overall, ACE2 binding accompanying the intrinsic dynamics of the up RBD contributes to the continuous swing motions observed in the S-ACE2 complex.

Furthermore, the B-factor distribution of our S-ACE2 complex demonstrated enhanced dynamics in the S1 region including RBD and NTD (Fig. 4D), facilitating the release of the associated ACE2-S1 component and transitions of the S2 subunit toward a stable postfusion conformation. We found a notable drop in the interaction surface between the S1 and S2 subunits from the S-closed state (8982.3 Å2) to the S-ACE2 state (6521.7 Å2).

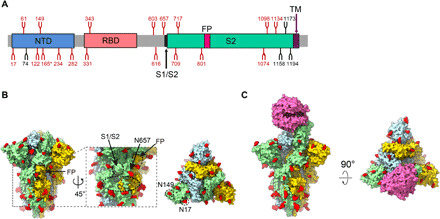

The SARS-CoV-2 S glycan shields

It has been suggested that the large number of N-linked glycans covering the surface of the spike protein of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV could pose a challenge to antigen recognition, which thus may help the virus evade immune surveillance (2, 36). Similar to SARS-CoV S, SARS-CoV-2 S also comprises 22 N-linked glycosylation (Fig. 5A) (8, 41). In our S-closed structure, we resolved the density for 18 N-linked glycans per protomer (Fig. 5, A and B, and fig. S4E), including 2 glycans at sites N17 and N149 located in the NTD (Fig. 5B), while the 3 glycans located in the flexible C-terminal region are missing as in other studies (7, 8). Similar to MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV S trimers (2, 19, 42), the SARS-CoV-2 S trimer also forms a glycan hole in the proximity of the S1/S2 cleavage site and the FP (near the S2′ cleavage site; Fig. 5B). Although there is an extra glycan at the N657 site near the S1/S2 cleavage site in SARS-CoV-2 S, the hole region is still more sparsely glycosylated than the rest of the protomer. This glycan hole might be important for permitting the access of activating host proteases and for allowing membrane fusion to take place without obstruction (2, 19, 42). After ACE2 binding, our S-ACE2 structure revealed that the density corresponding to glycan at the N165 site is weaker in protomer 1, while the other resolved glycans remain visible in the S-ACE2 structure (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5. Organization of the resolved N-linked glycans of SARS-CoV-2 S trimer.

(A) Schematic representation of SARS-CoV-2 S glycoprotein. The positions of N-linked glycosylation sequons are shown as branches. A total of 18 N-linked glycans detected in our S-closed cryo-EM map are shown in red, and the remaining undetected ones in black. After ACE2 binding, the glycan density that appears weaker is indicated (*). (B) Surface representation of the glycosylated S trimer in the S-closed state with N-linked glycans shown in red. The location of glycan hole is indicated in black dotted ellipsoid, with the locations of S1/S2 and FP, and glycan at N657 site near the glycan hole indicated. The newly captured glycans at the N17 and N149 sites are indicated in the top view. (C) Surface representation of the glycosylated S-ACE2 complex with N-linked glycans in red.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we determined a tightly closed state of SARS-CoV-2 S trimer revealing the stably packed FP. We captured the architecture of the SARS-CoV-2 S trimer in complex with ACE2. We found that the ACE2 receptor could markedly shift the conformational landscape of the S trimer, and ACE2 binding triggers considerable conformational dynamics in S1 subunits, resulting in a substantial decrease in S1/S2 interface area. Furthermore, our structural and biochemical analyses revealed that the RBM T470-T478 loop and residue Y505 play vital roles in the binding of SARS-CoV-2 RBD to the ACE2 receptor. Of note, the T470-T478 loop and residue Y505 identified in our study are different from the ACE2-binding sites reported before (22, 43); for instance, in one of these studies, the reported key residues are N481–N487, Q493, and N501 (22). We also depicted a more complete picture of the glycan shielding with a glycan hole of the spike glycoprotein. Our findings depict an important role for FP in stabilization of the S trimer and the mechanism of FP activation and provide structural basis on the enhanced infectivity induced by spike D614G mutation.

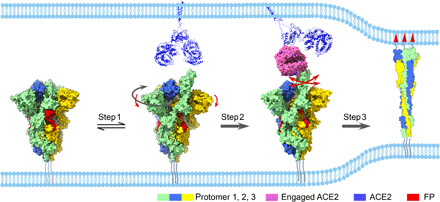

Based on the data, we put forward a mechanism of ACE2-induced conformational transitions of the SARS-CoV-2 S trimer, the dynamic allosteric fusion machine, from the ground prefusion state to the postfusion state (Fig. 6). Under the receptor-free condition, the majority of the S trimers are in the tightly closed ground prefusion state with inactivated FP, and only a minor population of the particles is in the intrinsically transient open state with one RBD up representing the fusion-prone state, forming a dynamic balance between the two states under equilibrium conditions (step 1). However, the presence of ACE2 and subsequent trapping of the RBD (discussed later) could overcome the energy barrier, break the balance, and shift the conformational landscape toward the open state with an untwist/downward-shift motion of S1 subunits, leading to unpacked/activated FPs, weakened interactions among the protomers, and, eventually, an up RBD. In step 2, once the ACE2 traps the up RBD, the associated ACE2-RBD exhibits combined continuous swing motions on the topmost surface of the S trimer. These encoded motions and generated dynamics could disturb the allosteric network and release the constrains imposed on the fusion machinery, beneficial for the destabilization and releasing of the ACE2-S1 component, thereby allowing S2 subunits to refold and fuse the viral and host membranes (step 3). This could be the transition pathway of the dynamic fusion machinery of SARS-CoV-2.

Fig. 6. The proposed mechanism of ACE2-induced conformational transitions of SARS-CoV-2 S trimer.

Conformational transitions from the closed ground prefusion state (with packed FP, in red) to the transiently open state (step 1) with an untwisting motion (highlighted in dark gray arrow) associated with a downward movement of S1 (red arrow), from the open state to the dynamic ACE2 engaged state (step 2), and then all the way to the refolded postfusion state (step 3). The continuous swing motions of ACE2-RBD within S trimer are indicated by red arrows. The S trimer associated with ACE2 dimer (third panel) was generated by aligning the ACE2 of our S-ACE2 structure with the available full-length ACE2 dimer structure (PDB: 6M1D). The postfusion state was illustrated as a cartoon (PDB: 6XRA).

The dominantly populated conformation (94%) for the unliganded SARS-CoV-2 S trimer is in the tightly closed state (more compact than that of SARS-CoV S trimer) with all the RBD domains buried, resulting in conformational masking preventing antibody binding and neutralization at sites of receptor binding. This SARS-CoV-2 conformational masking mechanism of neutralization escape could affect all antibodies that bind to the receptor binding site, similar to that described for HIV-1 Env (33, 34). While for MERS-CoV or SARS-CoV S trimer, the closed state is less populated (5.4 and 27.6%, respectively), indicating the conformational masking mechanism may be less effective for the two viruses (26, 30). Our findings also suggest that unliganded S trimer proteins of SARS-CoV-2 are inherently competent to transiently display conformation with one RBD up ready for ACE2 receptor binding; ACE2 facilitates the capture of the preexisting open conformation that is spontaneously sampled in the unliganded spike, rather than triggering a trimer opening event. Therefore, the spontaneously sampled S trimer conformations and intrinsic dynamics between them, encoded in this fusion machine, may serve a functional role in infectivity.

Our data also suggest that the SARS-CoV-2 S trimer is very sensitive to ACE2. For instance, the presence of ACE2 triggers an extremely thorough conformational landscape transitions from the dominantly closed state (94%) to all open configurations (including 26.2% free open state and 73.8% ACE2-bound open state). While in the counterpart of SARS-CoV, ACE2 induces conformational landscape transitions from 27.6% closed state and 72.4% open state to 24% closed state and 76% open state (including 26.7% free open state and 49.2% ACE2-bound open state) (1, 30). This demonstrates that the SARS-CoV-2 S trimer is much more sensitive to ACE2 than SARS-CoV S in terms of receptor-triggered transformation from the closed prefusion state to the fusion-prone open state, which might have contributed to the observed superior infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with that of SARS-CoV.

It is noteworthy that the SARS-CoV-2 spike D614G mutation has been reported to promote the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2, while the underlying structural basis remains not fully understood (13–15). Here, our S-closed structure demonstrated that D614 is heavily involved in the interaction with K854, K835, and Y837 of FP through its side-chain atoms (Fig. 1I and table S2). This interaction contributes greatly to the linkage/allostery between neighboring protomers and between the S1 and S2 subunits. However, the mutation of D614 to G without side chain could eliminate most of the interactions between D614 and FP, potentially leading to coordinated unpacking/activation of FPs. In a recent in situ structure of SARS-CoV-2 S trimer containing the D614G mutation, the folded structure for FP (the 833 to 853 regions) was not observed (44) and the conformation of their map is more comparable to another closed-state S structure (6VXX) (8), which exhibits an untwist movement relative to our S-closed structure, thus appearing less compact (Fig. 1E). We therefore propose that the D614G mutation could reduce constrains between neighboring protomers and between S1/S2 subunits and consequently lower the energy barrier for conformational transformation from the closed prefusion state to the fusion-prone open state, leading to an even more sensitive SARS-CoV-2 spike to ACE2 binding. Together, the altered allosteric response stimulated by the D614 mutation could be the underling mechanism of enhanced infectivity of the G614 strain. Comparable mechanism has been proposed for other allosteric machines (45).

In summary, our cryo-EM study reveals the unliganded SARS-CoV-2 S trimer to be intrinsically dynamic and to transform between two distinct prefusion conformations, whose relative occupancies could be markedly remodeled by receptor ACE2. These results support a dynamics-based mechanism of immune evasion and ligand recognition (34). Thus, our study delineates the property of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein that simultaneously allows the retention of function and the evasion of the humoral immune response. We also delineate that the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is highly sensitive to the ACE2 receptor; ACE2 binding elicits substantial conformational dynamics in S1 subunits that could trigger transitions of the spike protein toward the postfusion state prepared for viral entry and infection. Collectively, our findings enhance our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 infection and provide important information for the design and optimization of vaccines and therapeutics aimed to block receptor binding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of SARS-CoV-2 S trimer and human ACE2

To express SARS-CoV-2 S glycoprotein ectodomain, the mammalian codon-optimized gene coding SARS-CoV-2 (Wuhan-Hu-1 strain, GenBank ID: MN908947.3) S glycoprotein ectodomain (residues M1–Q1208) with proline substitutions at K986 and V987, a “GSAS” substitution at the furin cleavage site (R682 to R685) was cloned into vector pcDNA 3.1+. A C-terminal T4 fibritin trimerization motif, a TEV protease cleavage site, a FLAG tag, and a His tag were cloned downstream of the SARS-CoV-2 S glycoprotein ectodomain (fig. S1A). A gene encoding human ACE2 PD domain (Q18-D615) with an N-terminal interleukin-10 (IL-10) signal peptide and a C-terminal His tag was cloned into vector pcDNA 3.4. The expression vectors were transiently transfected into HEK293F cells using polyethylenimine. Three days after transfection, the supernatants were harvested. To purify the His-tagged S and ACE2 proteins, the clarified supernatants were added with 20 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, and 4 mM MgCl2, and incubated with Ni–nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) resin at 4°C for 1 hour. The Ni-NTA resin was recovered and washed with 20 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, and 20 mM imidazole. The protein was eluted by 20 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, and 250 mM imidazole.

BLI assay

Before the BLI experiments, SARS-CoV-2 S trimer protein was biotinylated using the EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-LC-Biotin kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then purified using the Zeba spin desalting column (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to manufacturer’s protocols. To determine binding affinity of ACE2, BLI assay was carried out using an Octet Red 96 instrument (Pall FortéBio, USA). Briefly, biotinylated SARS-CoV-2 S trimer protein was loaded onto streptavidin biosensors (Pall FortéBio). S-trimer–bound biosensors were dipped into wells containing varying concentrations of ACE2 protein, and the interactions were monitored over a 500-s association period. Finally, the sensors were switched to dissociation buffer [0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 0.02% Tween 20 and 0.1% bovine serum albumin] for a 500-s dissociation phase. Data were analyzed using Octet data analysis software version 11.0 (Pall FortéBio).

SARS-CoV-2 S-ACE2 complex formation

The purified SARS-CoV-2 S glycoprotein ectodomain and human ACE2 PD domain were mixed at a molar ratio of 1:3 and were incubated on ice for 2 hours. The mixture was purified by gel filtration chromatography using a Superose 6 increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) preequilibrated with 20 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, and 4% glycerol. For cross-linking complex, the buffers of purified SARS-CoV-2 S glycoprotein ectodomain and human ACE2 PD domain were exchanged to 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5) and 200 mM NaCl; then, SARS-CoV-2 S and human ACE2 were mixed at a molar ratio of 1:3. After incubation on ice for 2 hours, the complex was cross-linked by 0.1% glutaraldehyde, which is commonly used in cryo-EM studies of fragile macromolecular complexes (46, 47). The glutaraldehyde was neutralized by adding 20 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5) after being incubated on ice for 1 hour. The mixture was run over a Superose 6 increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) in 20 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, and 4% glycerol. The complex peak fractions were concentrated and assessed by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and negative-staining EM.

Negative-stain sample preparation, data collection, and initial model building

For the negative-stain sample, a volume of 5 μl of SARS-CoV-2 S-ACE2 sample was placed on a plasma-cleaned copper grid for 1 minute. Excess sample on the grid was blotted off using filter paper, and a volume of 5 μl of 0.75% uranyl formate (UF) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to wash the grid. After blotting, another volume of 5 μl of 0.75% UF was placed on the grid again for 1 minute to stain. Grids were visualized under a Tecnai G2 Spirit 120-kV transmission electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and micrographs were taken using an Eagle camera with a nominal magnification of 67,000 ×, yielding a pixel size of 1.74 Å. A total of 41,827 particles were autopicked in EMAN2 (48). After 2D classification, we selected good averages with 13,047 particles for initial model building, which were performed in Relion 3.0 (49).

Cryo-EM sample preparation for SARS-CoV-2 S trimer and S-ACE2 complex

To prepare the cryo-EM sample of SARS-CoV-2 S trimer, the sample was diluted into around 2 mg/ml using buffer with 20 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, and 4% glycerol. A 2.2-μl aliquot of the S trimer sample was applied on a plasma-cleaned holey carbon grid (R2/1, 200 mesh; Quantifoil) or Graphene Oxide-Lacey Carbon grid (300 mesh, EM Resolutions). The grid was blotted with Vitrobot Mark IV (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a blot force of −1 and 1-s blot time at 100% humidity and 8°C and then plunged into liquid ethane cooled by liquid nitrogen. To prepare the cryo-EM sample of S-ACE2 complex with or without cross-linking, we used Graphene Oxide-Lacey Carbon grid (300 mesh, EMR) and adopted the same vitrification procedure as for the S trimer.

Cryo-EM data collection

Cryo-EM movies of the samples were collected on a Titan Krios electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operated at an accelerating voltage of 300 kV with a nominal magnification of ×22,500 (table S1). The movies were recorded on a K2 Summit direct electron detector (Gatan) operated in the super-resolution mode (yielding a pixel size of 1.02 Å after two times binning), under a low-dose condition in an automatic manner using SerialEM (50). Each frame was exposed for 0.15 s, and the total accumulation time was 6.45 s, leading to a total accumulated dose of 50 e−/Å2 on the specimen. To solve the problem of preferred orientation associated with SARS-CoV-2 S trimer, we additionally collected tilt datasets with the stage tilt at 30° or 40°, while the other conditions remained the same.

Cryo-EM 3D reconstruction

Single-particle analysis was mainly executed in Relion 3.1 (38). All images were aligned and summed using MotionCor2 software (51). After contrast transfer function (CTF) parameter determination using CTFFIND4 (52), particle autopicking, manual particle checking, and reference-free 2D classification, particles with S trimer features were maintained for further processing.

For receptor-free S trimer sample, 226,082 particles were picked from nontilt micrographs, and 118,420 remained after 2D classification (fig. S3). These particles went through 3D auto-refine using available SARS-CoV-2 S trimer cryo-EM map (EMDB: 21452) low-pass filtered to 40-Å resolution as initial model (8). These particles were refined into a closed-state map of S trimer with imposed C3 symmetry. We then re-extracted the particles using the refinement coordinates to recenter it. After CTF refinement and polishing, these particles were refined with C3 symmetry again. It is noteworthy that the Euler angle distribution of the map suggested the dataset is lacking tilted top views (fig. S2C, left panel). When we refine the dataset without imposing threefold symmetry, the top view of the map appeared distorted, indicating a preferred orientation problem associated with the sample. To overcome the preferred orientation problem, we additionally collected tilt data and boxed out 198,737 particles from 40° tilt micrographs and 16,010 particles from 30° tilt micrographs. After 2D classification, 184,661 particles remained. We then used goCTF software to determine the defocus for each of the tilt particle, and these particles were re-extracted with corrected defocus (53). After combining the tilt with nontilt particles, we refined the dataset without imposing symmetry, then performed two rounds of 3D and 2D classifications to further clean up the dataset, and obtained a dataset of 151,505 particles, of which 62,368 particles were from the tilt data. We then carried out heterogeneous refinement in CryoSparc (54) and obtained a closed-state map from 142,345 particles and an open-state reconstruction with 9160 particles (fig. S3). After CTF refinement and Bayesian polishing, the closed-state map was refined to 2.7-Å resolution with C3 symmetry, while the open-state map was at 12.8-Å resolution and the resolution was hard to improve, indicating an intrinsic dynamic nature of the open state. The overall resolution was determined on the basis of the gold standard criterion using an Fourier shell correlation (FSC) of 0.143.

For the SARS-CoV-2 S-ACE2 cross-linked dataset, 298,127 particles were picked from original micrographs, and 138,632 particles remained after 2D classification (fig. S6). These particles were refined with an initial model built from our negative staining data. We then re-extracted the particles to recenter them. These particles went through a 3D-2D classification step, resulting in a further cleaned-up dataset of 77,440 particles. We refined these particles into a map of ACE2-bound S trimer complex. We then used this map as an initial model to refine the originally picked 298,127 particles for one round to re-extract and recenter the particles. After 2D classification, 207,742 particles remained. After two rounds of the 3D-2D cleaning step, 136,412 particles were left for further structure determination. After heterogeneous refinement in CryoSparc, class 1 resembled an ACE2-free open state of the S trimer, and classes 2 to 5 adopted the S-ACE2 engaged conformation. For class 1, after further 2D classification, we refined the 24,502 cleaned-up particles into an S-open map at 6.0-Å resolution using nonuniform refinement in CryoSparc. Among the other four classes with bound ACE2, we sorted out good particles for classes 2 to 4 by 2D classification and combined them with class 5 exhibiting good structural details, resulting in a dataset of 68,987 particles. After refinement, Bayesian polishing, and CTF refinement, we reconstructed a 3.8-Å-resolution SARS-CoV-2 S-ACE2 map. The S trimer portion without the up RBD was rather stable, which could be locally refined to 3.3 Å using local refinement in CryoSparc with nonuniform refinement option chosen. The ACE2 associated with the up RBD was subtracted and refined in Relion to obtain an 8.4-Å map with better connectivity. Multibody refinement was applied to analyze the mobility of the S-ACE2, S-closed, and S-open states.

For SARS-CoV-2 S-ACE2 without the cross-linking dataset, we followed similar classification and cleaning-up strategy and obtained 81,820 particles. Through heterogeneous refinement and 2D classification in CryoSparc, we reconstructed a 5.3-Å-resolution SARS-CoV-2 S-ACE2 map from 32,866 particles using nonuniform refinement and an unliganded open-state map of 11.2-Å resolution from 15,149 particles, with the population of 68.4 and 31.6%, respectively. Multibody refinement was also applied to analyze the mobility of the complex.

Pseudoatomic model building

To build the pseudoatomic model for our SARS-CoV-2 S-closed structure, we used the available atomic model of SARS-CoV-2 S (PDB: 6VXX) as initial model (8). We first refined the model against our map using phenix.real_space_refine module in Phenix (55). For the missing loop regions in the S1 subunit, we either built the homology model on the basis of SARS-CoV S structure (PDB: 6CRW) (27) through the SWISS-MODEL webserver (56), or built the loop manually according to the density in COOT (57). For the FP region, we first built the homology model by the Modeller tool within Chimera by using the MERS-CoV S structure (PDB: 6NB3) as template (2, 58, 59) and then used Rosetta to refine this region against the density map (60). Eventually, we used phenix.real_space_refine again for the protomer and S trimer model refinement against the map.

For the SARS-CoV-2 S-ACE2 structure, we used the SARS-CoV-2 RBD-ACE2 crystal structure (PDB: 6M0J) (21) as initial model for the ACE2 and the associated up RBD portion and our S-closed model as initial model for the remaining portion. These models were first refined against the corresponding focused map using Rosetta and Phenix (60) and then combined together in COOT. We then refined the combined model against our 3.8-Å-resolution SARS-CoV-2 S-ACE2 map using Rosetta and Phenix. For the S-open structure, we used the model of SARS-CoV-2 S-ACE2 as initial model with ACE2 removed and refined against the map using Rosetta.

We used phenix.molprobity and phenix.emringer to evaluate the models and calculated B-factors by atom displacement refinement function in phenix.real_space_refine. We used UCSF (University of California, San Francisco) Chimera and ChimeraX for figure generation (59, 61) and also for rotation, translation, RMSD, and vdw contact measurement. Interaction surface analysis was conducted by the PISA (Proteins, Interfaces, Structures and Assemblies) server (62).

Identification of key amino acids involved in ACE2 recognition with RBD mutants by ELISA

To uncover the amino acids important for ACE2 receptor recognition, ACE2 ecotodomain (residues Q18 to S740) gene, with an N-terminal IL-10 signal peptide, tagged with human immunoglobulin G1Fc (IgG1Fc) and His tag at the C terminus, was cloned into the pcDNA 3.4 vector. Codon-optimized RBD (residues V320 to G550) gene fragment, with an N-terminal IL-10 signal peptide, tagged with His tag at the C terminus, was cloned into the pcDNA 3.4 vector. Three SARS-CoV-2 RBD mutants were constructed. For mutant RBD-(core), amino acids R319 to N437 of core region in the SARS-CoV-2 RBD were substituted by the corresponding region of SARS-CoV strain Tor2 (GenBank ID: AAP41037.1). For mutants RBD-(RBM-R2) and RBD-(RBM-R3), residues L452 to K462, and residues T470 to T478 of the RBM region in the SARS-CoV-2 RBD were mutated into the corresponding regions of SARS-CoV strain Tor2, respectively. For single-point mutations of RBD (Q498A), RBD (V503A), and RBD (Y505A), RBD residues Q498, V503, and Y505 were substituted by Ala, respectively. All mutant plasmids were constructed using the MutExpress II Fast Mutagenesis Kit V2 (Vazyme, China) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The proteins were generated using HEK293F expression system and purified as described above.

Anti-RBD polyclonal antibody and monoclonal antibody (MAb) 1A10 were prepared by immunizing BALB/c mice with recombinant SARS-CoV-2 RBD fused with a C-terminal mouse IgGFc tag (Sino Biological Inc., Beijing, China) using previously described protocols (63).

The purified RBD mutants were tested by ELISA for reactivity with the receptor ACE2. Briefly, ELISA plates were coated with 100 ng per well of the purified RBD mutants in PBS at 37°C for 2 hours and then blocked with 5% milk in PBS–Tween 20. Next, the plates were incubated with 50 ng per well of ACE2-hFc fusion protein, 50 μl per well of culture supernatant of hybridoma 1A10, or 50 μl per well of mouse anti-RBD sera (diluted at 1/1000) at 37°C for 2 hours. After washing, the corresponding secondary antibodies, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated anti-human IgG1 (Abcam, USA) or HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), were added and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. After washing and color development, absorbance at 450 nm was determined.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the staffs of the NCPSS Electron Microscopy Facility, Database and Computing Facility, and Protein Expression and Purification Facility for instrument support and technical assistance. Funding: Y.C. was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of CAS (XDB37040103), the National Basic Research Program of China (2017YFA0503503), the NSFC (31670754 and 31872714), the Program of Shanghai Academic Research Leader (20XD1404200), the CAS Major Science and Technology Infrastructure Open Research Projects, and the CAS-Shanghai Science Research Center (CAS-SSRC-YH-2015-01 and DSS-WXJZ-2018-0002). Z.H. was supported by grants from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB29040300), from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2020YFC0845900), and from the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (20431900402). Author contribution: Y.C. and Yanxing Wang designed the experiments; Yanxing Wang, C.Z., Yalei Wang, and Y.Y. purified the proteins; X.H., Q.H., S.W., and C.L. performed the NS-EM; C.L., X.H., and W.H. optimized the cryo-EM sample-preparation condition; C.L., W.H., Yifan Wang, and W.Z. collected the cryo-EM data, with the involvement of F.W. and L.K.; C.X. performed the cryo-EM reconstructions and the model building; C.X., C.L., X.H., Q.H., S.W., Qiaoyu Zhao, W.H., K.C., and Qinyu Zuo performed particle picking; C.Z. and Yanxing Wang performed the biochemical analyses; C.X., Y.C., Yanxing Wang, C.Z., and Z.H. analyzed the data; Y.C., Yanxing Wang, C.X., and Z.H. wrote the manuscript, with inputs from all the others. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Cryo-EM maps have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank, http://www.emdataresource.org/ (accession nos. 30660, 30661 and 30701), and the associated models have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org (accession nos. 7DF3, 7DF4, and 7DK3). Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/sciadv.abe5575/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Song W., Gui M., Wang X., Xiang Y., Cryo-EM structure of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein in complex with its host cell receptor ACE2. PLOS Pathog. 14, e1007236 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walls A. C., Xiong X., Park Y. J., Tortorici M. A., Snijder J., Quispe J., Cameroni E., Gopal R., Dai M., Lanzavecchia A., Zambon M., Rey F. A., Corti D., Veesler D., Unexpected receptor functional mimicry elucidates activation of coronavirus fusion. Cell 176, 1026–1039.e15 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabaan A. A., al-Ahmed S. H., Haque S., Sah R., Tiwari R., Malik Y. S., Dhama K., Yatoo M. I., Bonilla-Aldana D. K., Rodriguez-Morales A. J., SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-COV: A comparative overview. Infez. Med. 28, 174–184 (2020). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang T., Bidon M., Jaimes J. A., Whittaker G. R., Daniel S., Coronavirus membrane fusion mechanism offers a potential target for antiviral development. Antiviral Res. 178, 104792 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosch B. J., van der Zee R., de Haan C. A., Rottier P. J., The coronavirus spike protein is a class I virus fusion protein: Structural and functional characterization of the fusion core complex. J. Virol. 77, 8801–8811 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li F., Structure, function, and evolution of coronavirus spike proteins. Annu Rev. Virol. 3, 237–261 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K. S., Goldsmith J. A., Hsieh C. L., Abiona O., Graham B. S., McLellan J. S., Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 367, 1260–1263 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walls A. C., Park Y. J., Tortorici M. A., Wall A., McGuire A. T., Veesler D., Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell 181, 281–292.e6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epand R. M., Fusion peptides and the mechanism of viral fusion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1614, 116–121 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai Y., Zhang J., Xiao T., Peng H., Sterling S. M., Walsh R. M. Jr., Rawson S., Rits-Volloch S., Chen B., Distinct conformational states of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Science 369, 1586–1592 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wrobel A. G., Benton D. J., Xu P., Roustan C., Martin S. R., Rosenthal P. B., Skehel J. J., Gamblin S. J., SARS-CoV-2 and bat RaTG13 spike glycoprotein structures inform on virus evolution and furin-cleavage effects. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 27, 763–767 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiong X., Qu K., Ciazynska K. A., Hosmillo M., Carter A. P., Ebrahimi S., Ke Z., Scheres S. H. W., Bergamaschi L., Grice G. L., Zhang Y.; CITIID-NIHR COVID-Bio Resource Collaboration, Nathan J. A., Baker S., James L. C., Baxendale H. E., Goodfellow I., Doffinger R., Briggs J. A. G., A thermostable, closed SARS-CoV-2 spike protein trimer. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 27, 934–941 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu J., He C.-L., Gao Q.-Z., Zhang G.-J., Cao X.-X., Long Q.-X., Deng H.-J., Huang L.-Y., Chen J., Wang K., Tang N., Huang A.-L., The D614G mutation of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein enhances viral infectivity and decreases neutralization sensitivity to individual convalescent sera. BioRxiv 10.1101/2020.06.20.161323, (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang L., Jackson C. B., Mou H., Ojha A., Rangarajan E. S., Izard T., Farzan M., Choe H., The D614G mutation in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein reduces S1 shedding and increases infectivity. BioRxiv 10.1101/2020.06.12.148726, (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daniloski Z., Guo X., Sanjana N. E., The D614G mutation in SARS-CoV-2 Spike increases transduction of multiple human cell types. BioRxiv 10.1101/2020.06.14.151357 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou P., Yang X. L., Wang X. G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H. R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C. L., Chen H. D., Chen J., Luo Y., Guo H., Jiang R. D., Liu M. Q., Chen Y., Shen X. R., Wang X., Zheng X. S., Zhao K., Chen Q. J., Deng F., Liu L. L., Yan B., Zhan F. X., Wang Y. Y., Xiao G. F., Shi Z. L., A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579, 270–273 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Q., Zhang Y., Wu L., Niu S., Song C., Zhang Z., Lu G., Qiao C., Hu Y., Yuen K. Y., Wang Q., Zhou H., Yan J., Qi J., Structural and functional basis of SARS-CoV-2 entry by using human ACE2. Cell 181, 894–904.e9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., Schiergens T. S., Herrler G., Wu N. H., Nitsche A., Müller M. A., Drosten C., Pöhlmann S., SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181, 271–280.e8 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walls A. C., Tortorici M. A., Snijder J., Xiong X., Bosch B. J., Rey F. A., Veesler D., Tectonic conformational changes of a coronavirus spike glycoprotein promote membrane fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 11157–11162 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan R., Zhang Y., Li Y., Xia L., Guo Y., Zhou Q., Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 367, 1444–1448 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lan J., Ge J., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou H., Fan S., Zhang Q., Shi X., Wang Q., Zhang L., Wang X., Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 581, 215–220 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shang J., Ye G., Shi K., Wan Y., Luo C., Aihara H., Geng Q., Auerbach A., Li F., Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 581, 221–224 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walls A. C., Tortorici M. A., Bosch B. J., Frenz B., Rottier P. J. M., DiMaio F., Rey F. A., Veesler D., Cryo-electron microscopy structure of a coronavirus spike glycoprotein trimer. Nature 531, 114–117 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walls A., Tortorici M. A., Bosch B. J., Frenz B., Rottier P. J. M., DiMaio F., Rey F. A., Veesler D., Crucial steps in the structure determination of a coronavirus spike glycoprotein using cryo-electron microscopy. Protein Sci. 26, 113–121 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tortorici M. A., Walls A. C., Lang Y., Wang C., Li Z., Koerhuis D., Boons G. J., Bosch B. J., Rey F. A., de Groot R. J., Veesler D., Structural basis for human coronavirus attachment to sialic acid receptors. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 26, 481–489 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pallesen J., Wang N., Corbett K. S., Wrapp D., Kirchdoerfer R. N., Turner H. L., Cottrell C. A., Becker M. M., Wang L., Shi W., Kong W. P., Andres E. L., Kettenbach A. N., Denison M. R., Chappell J. D., Graham B. S., Ward A. B., McLellan J. S., Immunogenicity and structures of a rationally designed prefusion MERS-CoV spike antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E7348–E7357 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirchdoerfer R. N., Wang N., Pallesen J., Wrapp D., Turner H. L., Cottrell C. A., Corbett K. S., Graham B. S., McLellan J. S., Ward A. B., Stabilized coronavirus spikes are resistant to conformational changes induced by receptor recognition or proteolysis. Sci. Rep. 8, 15701 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miroshnikov K. A., Marusich E. I., Cerritelli M. E., Cheng N., Hyde C. C., Steven A. C., Mesyanzhinov V. V., Engineering trimeric fibrous proteins based on bacteriophage T4 adhesins. Protein Eng. 11, 329–332 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan Y. Z., Baldwin P. R., Davis J. H., Williamson J. R., Potter C. S., Carragher B., Lyumkis D., Addressing preferred specimen orientation in single-particle cryo-EM through tilting. Nat. Methods 14, 793–796 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gui M., Song W., Zhou H., Xu J., Chen S., Xiang Y., Wang X., Cryo-electron microscopy structures of the SARS-CoV spike glycoprotein reveal a prerequisite conformational state for receptor binding. Cell Res. 27, 119–129 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korber B., Fischer W. M., Gnanakaran S., Yoon H., Theiler J., Abfalterer W., Hengartner N., Giorgi E. E., Bhattacharya T., Foley B., Hastie K. M., Parker M. D., Partridge D. G., Evans C. M., Freeman T. M., de Silva T. I., McDanal C., Perez L. G., Tang H., Moon-Walker A., Whelan S. P., LaBranche C. C., Saphire E. O., Montefiori D. C., Angyal A., Brown R. L., Carrilero L., Green L. R., Groves D. C., Johnson K. J., Keeley A. J., Lindsey B. B., Parsons P. J., Raza M., Rowland-Jones S., Smith N., Tucker R. M., Wang D., Wyles M. D., Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 spike: Evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell 182, 812–827.e19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korber B., Fischer W. M., Gnanakaran S., Yoon H., Theiler J., Abfalterer W., Foley B., Giorgi E. E., Bhattacharya T., Parker M. D., Partridge D. G., Evans C. M., de Silva T. I.; Sheffield COVID-Genomics Group, La Branche C. C., Montefiori D. C., Spike mutation pipeline reveals the emergence of a more transmissible form of SARS-CoV-2. BioRxiv 10.1101/2020.04.29.069054 , (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwong P. D., Doyle M. L., Casper D. J., Cicala C., Leavitt S. A., Majeed S., Steenbeke T. D., Venturi M., Chaiken I., Fung M., Katinger H., Parren P. W. I. H., Robinson J., van Ryk D., Wang L., Burton D. R., Freire E., Wyatt R., Sodroski J., Hendrickson W. A., Arthos J., HIV-1 evades antibody-mediated neutralization through conformational masking of receptor-binding sites. Nature 420, 678–682 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munro J. B., Gorman J., Ma X., Zhou Z., Arthos J., Burton D. R., Koff W. C., Courter J. R., Smith A. B., Kwong P. D., Blanchard S. C., Mothes W., Conformational dynamics of single HIV-1 envelope trimers on the surface of native virions. Science 346, 759–763 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shang J., Wan Y., Luo C., Ye G., Geng Q., Auerbach A., Li F., Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 11727–11734 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan Y., Cao D., Zhang Y., Ma J., Qi J., Wang Q., Lu G., Wu Y., Yan J., Shi Y., Zhang X., Gao G. F., Cryo-EM structures of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV spike glycoproteins reveal the dynamic receptor binding domains. Nat. Commun. 8, 15092 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li F., Li W., Farzan M., Harrison S. C., Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science 309, 1864–1868 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernandez-Leiro R., Scheres S. H. W., A pipeline approach to single-particle processing in RELION. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 73, 496–502 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakane T., Kimanius D., Lindahl E., Scheres S. H., Characterisation of molecular motions in cryo-EM single-particle data by multi-body refinement in RELION. eLife 7, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melero R., Oscar C., Sorzano S., Foster B., Vilas J.-L., Martínez M., Marabini R., Ramírez-Aportela E., Sanchez-Garcia R., Herreros D., del Caño L., Losana P., Fonseca-Reyna Y. C., Conesa P., Wrapp D., Chacon P., Lellan J. S. M., Tagare H. D., Carazo J.-M., Continuous flexibility analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Spike prefusion structures. IUCrJ 7, 1059–1069 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watanabe Y., Allen J. D., Wrapp D., McLellan J. S., Crispin M., Site-specific glycan analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 spike. Science 369, 330–333 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang Y., Liu C., Du L., Jiang S., Shi Z., Baric R. S., Li F., Two mutations were critical for bat-to-human transmission of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Virol. 89, 9119–9123 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yi C., Sun X., Ye J., Ding L., Liu M., Yang Z., Lu X., Zhang Y., Ma L., Gu W., Qu A., Xu J., Shi Z., Ling Z., Sun B., Key residues of the receptor binding motif in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 that interact with ACE2 and neutralizing antibodies. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 17, 621–630 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ke Z., Oton J., Qu K., Cortese M., Zila V., McKeane L., Nakane T., Zivanov J., Neufeldt C. J., Cerikan B., Lu J. M., Peukes J., Xiong X., Kräusslich H. G., Scheres S. H. W., Bartenschlager R., Briggs J. A. G., Structures and distributions of SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins on intact virions. Nature 10.1038/s41586-020-2665-2 , (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y., Doruker P., Kaynak B., Zhang S., Krieger J., Li H., Bahar I., Intrinsic dynamics is evolutionarily optimized to enable allosteric behavior. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 62, 14–21 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kastner B., Fischer N., Golas M. M., Sander B., Dube P., Boehringer D., Hartmuth K., Deckert J., Hauer F., Wolf E., Uchtenhagen H., Urlaub H., Herzog F., Peters J. M., Poerschke D., Lührmann R., Stark H., GraFix: Sample preparation for single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. Nat. Methods 5, 53–55 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patel A. B., Louder R. K., Greber B. J., Grünberg S., Luo J., Fang J., Liu Y., Ranish J., Hahn S., Nogales E., Structure of human TFIID and mechanism of TBP loading onto promoter DNA. Science 362, eaau8872 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bell J. M., Chen M., Baldwin P. R., Ludtke S. J., High resolution single particle refinement in EMAN2.1. Methods 100, 25–34 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zivanov J., Nakane T., Forsberg B. O., Kimanius D., Hagen W. J. H., Lindahl E., Scheres S. H. W., New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. eLife 7, e42166 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mastronarde D. N., Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J. Struct. Biol. 152, 36–51 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng S. Q., Palovcak E., Armache J. P., Verba K. A., Cheng Y., Agard D. A., MotionCor2: Anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rohou A., Grigorieff N., CTFFIND4: Fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J. Struct. Biol. 192, 216–221 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Su M., goCTF: Geometrically optimized CTF determination for single-particle cryo-EM. J. Struct. Biol. 205, 22–29 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Punjani A., Rubinstein J. L., Fleet D. J., Brubaker M. A., cryoSPARC: Algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., Richardson J. S., Terwilliger T. C., Zwart P. H., PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Waterhouse A., Bertoni M., Bienert S., Studer G., Tauriello G., Gumienny R., Heer F. T., de Beer T. A. P., Rempfer C., Bordoli L., Lepore R., Schwede T., SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W296–W303 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Emsley P., Cowtan K., COOT: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sali A., Comparative protein modeling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. Mol. Med. Today 1, 270–277 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E., UCSF Chimera–A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DiMaio F., Song Y., Li X., Brunner M. J., Xu C., Conticello V., Egelman E., Marlovits T. C., Cheng Y., Baker D., Atomic-accuracy models from 4.5-Å cryo-electron microscopy data with density-guided iterative local refinement. Nat. Methods 12, 361–365 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Meng E. C., Pettersen E. F., Couch G. S., Morris J. H., Ferrin T. E., UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 27, 14–25 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krissinel E., Henrick K., Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qu P., Zhang C., Li M., Ma W., Xiong P., Liu Q., Zou G., Lavillette D., Yin F., Jin X., Huang Z., A new class of broadly neutralizing antibodies that target the glycan loop of Zika virus envelope protein. Cell Discov. 6, 5 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Robert X., Gouet P., Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W320–W324 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/sciadv.abe5575/DC1