Abstract

Inherent complexity of plant metabolites necessitates the use of multi-dimensional information to accomplish comprehensive profiling and confirmative identification. A dimension-enhanced strategy, by offline two-dimensional liquid chromatography/ion mobility-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (2D-LC/IM-QTOF-MS) enabling four-dimensional separations (2D-LC, IM, and MS), is proposed. In combination with in-house database-driven automated peak annotation, this strategy was utilized to characterize ginsenosides simultaneously from white ginseng (WG) and red ginseng (RG). An offline 2D-LC system configuring an Xbridge Amide column and an HSS T3 column showed orthogonality 0.76 in the resolution of ginsenosides. Ginsenoside analysis was performed by data-independent high-definition MSE (HDMSE) in the negative ESI mode on a Vion™ IMS-QTOF hybrid high-resolution mass spectrometer, which could better resolve ginsenosides than MSE and directly give the CCS information. An in-house ginsenoside database recording 504 known ginsenosides and 58 reference compounds, was established to assist the identification of ginsenosides. Streamlined workflows, by applying UNIFI™ to automatedly annotate the HDMSE data, were proposed. We could separate and characterize 323 ginsenosides (including 286 from WG and 306 from RG), and 125 thereof may have not been isolated from the Panax genus. The established 2D-LC/IM-QTOF-HDMSE approach could also act as a magnifier to probe differentiated components between WG and RG. Compared with conventional approaches, this dimension-enhanced strategy could better resolve coeluting herbal components and more efficiently, more reliably identify the multicomponents, which, we believe, offers more possibilities for the systematic exposure and confirmative identification of plant metabolites.

Keywords: Dimension-enhanced strategy, Multicomponent characterization, Ginsenoside, Offline two-dimensional liquid chromatography, Ion mobility-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry, In-house database

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A dimension-enhanced strategy was proposed by 2D-LC/IM-QTOF-HDMSE.

-

•

New dimensions of tR in 1D-HILIC and CCS were provided.

-

•

An in-house ginsenoside database and a ginsenoside compound library were reported.

-

•

Automated peak annotation was achieved by UNIFI™.

-

•

323 ginsenosides, including 125 unknown, were characterized.

1. Introduction

A “bottleneck” issue that hinders the modernization of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) lies in the dimness of chemical substances they contain, which definitely restricts the pharmacological and efficacy investigations as well as the quality control [1]. The inherent complexity of the chemical substances, which is featured by the coexisting primary and secondary metabolites with wide spans of polarity, molecular weight, and content [2], and pervasive isomerism [3,4], renders the metabolites profiling and characterization being a head-scratching work involved in natural product research. Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC-MS), typically based on reversed-phase chromatography, is currently the most preferable choice in chemical basis elucidation of TCM [5]. However, more and more insufficiencies are exposed or reported when applying one-dimensional LC-MS to characterize the multicomponents of TCM: i) failing to acquire the MSn information of some minor or trace ingredients due to coelution as a result of the singular separation mechanism used and limited peak capacity; ii) the limited coverage of components because of the application of non-specific MS scan methods; iii) irreproducible results due to high dependence on professional skills in analyzing the obtained MSn data; and iv) difficulty in discriminating isomers on account of the limited dimension of structure information (the accessibility of only MS data). Moreover, the lack of specific natural product library is another prominent issue that largely restrains the precise assignment of the profiled compounds, although several metabolites databases are commercially available.

Remarkable progress, in response to these emerging issues, has been made very recently by developing potent analytical strategies with enhanced dimensions in both chromatography and MS. First, two-dimensional liquid chromatography (2D-LC) enables chromatographic separation twice, which can integrate different mechanisms of separation to greatly improve peak capacity and benefit ion response [6,7]. Second, various enhanced MS scan methods, based on data-dependent acquisition (DDA) or data-independent acquisition (DIA), have been available, enabling the untargeted metabolites profiling and characterization, which greatly boosts the coverage and sensitivity in detection of interested components [8,9]. Precursor ion list (obtained by phytochemistry-informed molecular design [10], neutral loss filtering [11], or mass defect filtering (MDF) [12,13], etc) can be predefined to guide MSn data acquisition using DDA or MS/MS experiments, which can improve the sensitivity in target components profiling even facing insufficient chromatographic separation. High-definition MSE (HDMSE) is a potent DIA approach on Waters ion-mobility quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometers (IM-QTOF; such as the SYNAPT HDMS and Vion IMS-QTOF) that enable an additional ion mobility separation and the fragmentation of full scan range of precursors [[14], [15], [16]]. Third, post-acquisition data processing techniques, such as diagnostic product ions filtering (DPIF) [17], nontargeted diagnostic ion network analysis (NINA) [18], mass spectral trees similarity filter (MTSF) [19], statistical analysis-oriented substructure recognition [20], together with the in silico peak annotation vehicles, can replace the laborious manual work and render MS data interpretation more efficient and more reproducible. Fourth, the addition of new dimension in structure information, such as predicted retention time [21] and ion-mobility derived collision cross section (CCS) [22,23], by providing else information orthogonal to MS data, is deemed to benefit the improvement on identification of isomers [24].

Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer, dubbed “the King of medicinal herbs”, currently is extensively consumed in the global scope as the source of herbal medicine (Asian ginseng) and versatile TCM preparations, healthcare products, food additives, and cosmetics [25]. Multiple classes of botanical metabolites, such as polysaccharides, ginsenosides, alkaloids, glucosides, and phenolic acids, have been reported from P. ginseng. Definitely, the ginsenosides thereof are the major bioactive components related to their tonifying effects. The known ginsenosides isolated from the Panax genus can be classified into protopanaxadiol type (PPD), protopanaxatriol type (PPT), oleanolic acid type (OA), octillol type (OT), malonylated, C17-side chain varied, and others [26]. Raw P. ginseng materials can be steamed to prepare the processed products, namely red ginseng, during which a series of chemical transformations can occur. Acidic hydrolysis and dehydration trigger the conversion of neutral ginsenosides into the rare ones, and malonylginsenosides into rare ginsenosides together with malonic acid and acetic acid [27]. An online comprehensive 2D-LC based metabolomics analysis unveiled nine potential markers useful for the differentiation between white ginseng (WG) and red ginseng (RG) [28].

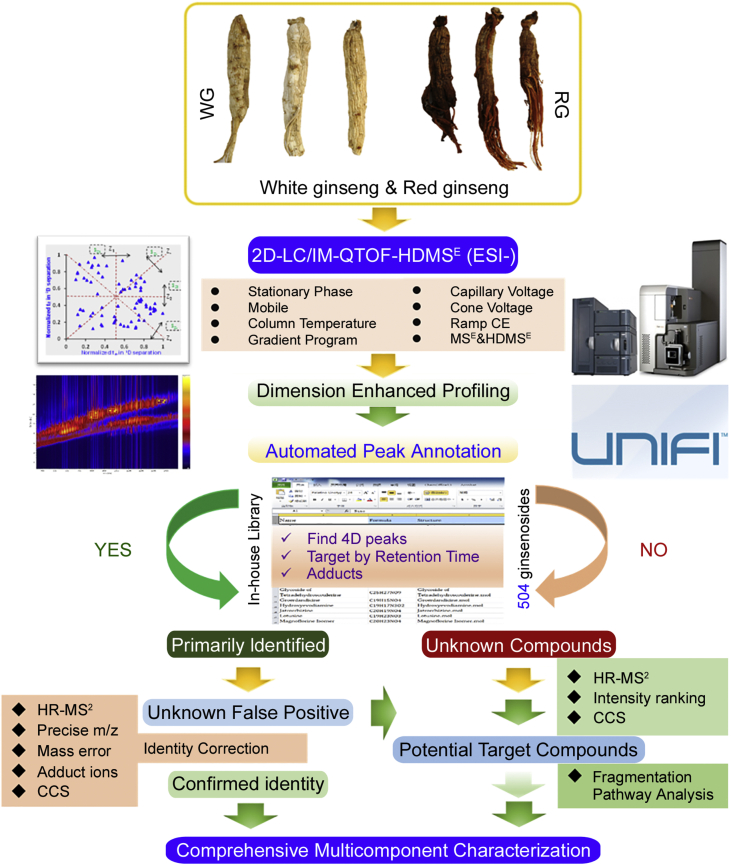

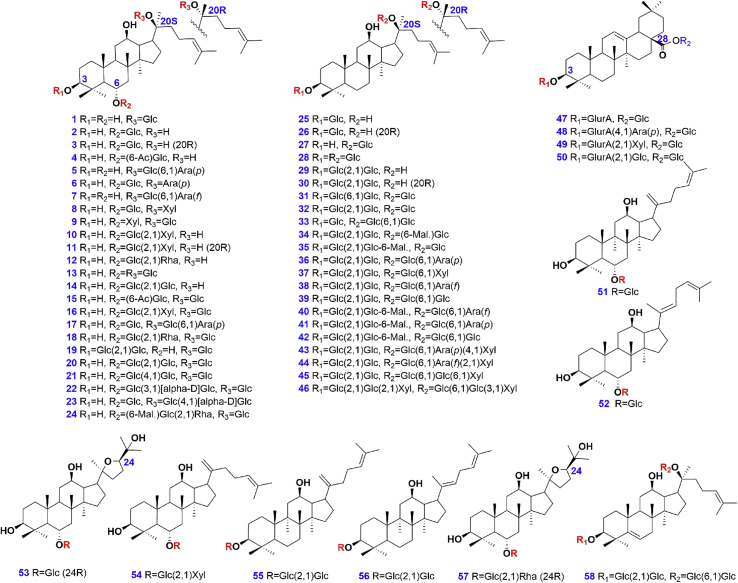

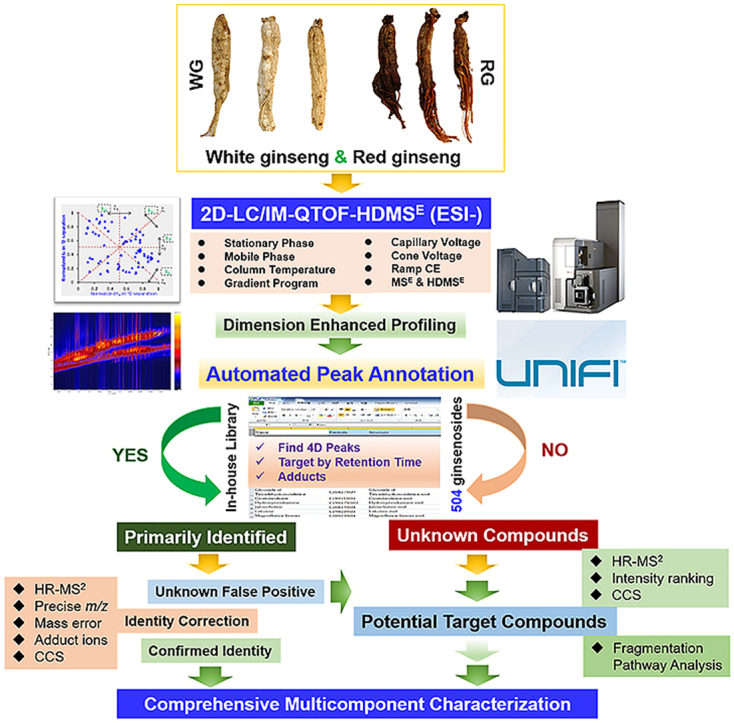

The aim of this work was to develop a dimension-enhanced approach, based on offline 2D-LC/IM-QTOF-MS (ion mobility/quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry), for the in-depth profiling and characterization of botanical metabolites with improved performance and definiteness. Using ginsenoside analysis of WG and RG as the model, a series of efforts were made to enhance the resolution, to elevate the efficiency, and to boost the reliability in ginsenoside characterization (Fig. 1). First, multi-dimensional information related to ginsenosides (involving tR-1D, tR-2D, MS1, MS2, and CCS) was acquired by offline 2D-LC/IM-QTOF-MS, in which IM-derived CCS determination offers a new dimension of information to support structural elucidation. Second, data-independent high-definition MSE (HDMSE) in the negative ESI mode was utilized for alternative acquisition of the fragmentation information regarding the precursors and all their fragments with the least missing of MS2 information. Third, a potent data-processing platform, UNIFI™, could enable efficient peak annotation with reproducible results. Four, an in-house database consisting of 504 known ginsenosides and 58 reference compounds (Fig. 2 and Table 1), was elaborated and incorporated into UNIFI™ to drive automated peak annotation. Hopefully, by this work, we can offer a practical strategy facilitating the comprehensive, efficient, and producible deconvolution of complicated plant metabolites with more reliable results.

Fig. 1.

A schematic diagram exhibiting the four-dimensional separation strategy used for the comprehensive profiling and characterization of ginsenosides from white ginseng (WG) and red ginseng (RG).

Fig. 2.

Chemical structures of 58 ginsenoside reference compounds.

Table 1.

An in-house ginsenoside library of 58 reference compounds.

| No. | Trivial name | Precursors (m/z) |

Formula | tR-2D(min) | tR-1D(min) | Mass error (ppm) | CCS (Å2) [M − H]- |

CCS (Å2) [M + HCOO]- |

Adducts | ESI-MS2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ginsenoside F1 | 683.4380 | C36H62O9 | 16.29 | 6.59 | 0.7 | – | 271.06/386.89 | +HCOO | 637.4306, 475.3681, 391.2841 |

| 2 | Ginsenoside Rh1 | 683.4378 | C36H62O9 | 12.32 | 6.43 | 0.4 | – | 275.43/375.25 | +HCOO | 637.4271, 475.3785, 391.2797 |

| 3 | 20(R)-Ginsenoside Rh1 | 683.4384 | C36H62O9 | 13.23 | 6.30 | 1.1 | – | 278.70 | +HCOO | 637.4308, 475.3783, 391.2843 |

| 4 | Compound I | 725.4481 | C38H64O10 | 19.93 | 4.64 | −0.08 | – | 289.38/402.39 | +HCOO | 679.4417, 637.4311, 475.3789, 391.2856 |

| 5 | Ginsenoside F3 | 815.4807 | C41H70O13 | 12.45 | 12.47 | 1.1 | – | 297.21 | +HCOO | 769.4730, 621.4359, 475.3781, 391.2836 |

| 6 | Sanchinoside A3 | 815.4819 | C41H70O13 | 8.35 | 11.86 | 2.3 | – | 234.11/291.63 | +HCOO | 769.4743, 637.4315, 475.3788 |

| 7 | Ginsenoside F5 | 815.4779 | C41H70O13 | 11.87 | 10.73 | −2.5 | – | 307.79/426.08 | +HCOO | 769.4719, 637.4299, 475.3778, 391.2846 |

| 8 | Compound II | 815.4790 | C41H70O13 | 8.33 | 12.91 | −1.1 | – | 236.08/299.66 | +HCOO | 637.4301, 475.3788, 391.2850 |

| 9 | Pseudoginsenoside Rt3 | 815.4799 | C41H70O13 | 7.78 | 11.81 | 0.07 | – | 238.40/298.86 | +HCOO | 769.4740, 607.4213, 475.3795, 391.2854 |

| 10 | Notoginsenoside R2 | 815.4808 | C41H70O13 | 11.03 | 11.65 | 1.2 | 294.50 | 296.37 | +HCOO | 769.4728, 637.4303, 475.3778, 391.2840 |

| 11 | 20(R)-Notoginsenoside R2 | 815.4810 | C41H70O13 | 11.98 | 12.86 | 1.4 | 298.89 | 301.22 | +HCOO | 769.4737, 637.4296, 475.3781, 391.2841 |

| 12 | Ginsenoside Rg2 | 829.4966 | C42H72O13 | 12.07 | 10.95 | 1.3 | – | 298.75 | +HCOO | 783.4885, 637.4307, 475.3779, 391.2841 |

| 13 | Ginsenoside Rg1 | 845.4914 | C42H72O14 | 6.50 | 14.90 | 1.2 | – | 240.98/294.03 | +HCOO | 799.4834, 637.4307, 475.3772, 391.2841 |

| 14 | Ginsenoside Rf | 845.4914 | C42H72O14 | 10.13 | 15.21 | 1.1 | 301.07 | 303.38 | +HCOO | 799.4836, 637.4308, 475.3781, 391.2842 |

| 15 | Notoginsenoside Rt | 887.4988 | C44H74O15 | 7.16 | 20.20 | −2.5 | 239.88/303.30 | 241.15/315.54 | +HCOO | 841.4943, 781.4727, 637.4306, 619.4201, 475.3788, 391.2847 |

| 16 | Notoginsenoside R1 | 977.5340 | C47H80O18 | 5.90 | 23.77 | 1.4 | 244.07/311.36 | 319.37 | +HCOO, –H, +Cl | 931.5251, 799.4835, 637.4302, 475.3776, 391.2838 |

| 17 | Notoginsenoside Fp1 | 977.5302 | C47H80O18 | 5.88 | 25.45 | −2.7 | – | 320.58 | +HCOO, –H | 931.5222, 799.4813, 637.4301, 475.3776, 391.2841 |

| 18 | Ginsenoside Re | 991.5497 | C48H82O18 | 6.52 | 22.39 | 1.4 | 247.70/320.49 | 252.01/323.99 | +HCOO, –H, +Cl | 945.5409, 783.4883, 637.4307, 475.3772, 391.2841 |

| 19 | Vinaginsenoside R4 | 1007.5456 | C48H82O19 | 8.93 | 27.85 | 2.4 | 326.03 | 261.01/330.29 | +HCOO,–H,+Cl | 961.5373, 799.4845, 637.4310, 619.4213, 475.3785, 391.2846 |

| 20 | 20-O-Glucosylginsenoside Rf | 1007.5408 | C48H82O19 | 5.56 | 28.73 | −2.4 | 246.92/327.81 | 257.92/330.44 | +HCOO,–H,+Cl | 961.5331, 799.4817, 637.4294, 475.3784, 391.2842 |

| 21 | Notoginsenoside N | 1007.5423 | C48H82O19 | 5.08 | 26.02 | 0.9 | 196.35/251.23/330.04 | 262.87/332.94 | +HCOO, –H | 961.5352, 799.4836, 619.4211, 475.3790, 391.2851 |

| 22 | Ginsenoside Re2 | 1007.5405 | C48H82O19 | 5.98 | 26.18 | −2.8 | 245.92/322.41 | 322.22 | +HCOO | 961.5334, 799.4823, 637.4304, 475.3783, 391.2846 |

| 23 | Ginsenoside Re3 | 1007.5407 | C48H82O19 | 5.77 | 26.10 | −2.5 | 261.08/329.06 | 270.98/330.42 | +HCOO | 961.5333, 799.4826, 637.4298, 475.3780.391.2843 |

| 24 | Malonyl-floralginsenoside Re1 | 1031.5447 | C51H84O21 | 7.62 | 27.14 | 1.4 | 242.27/320.37 | – | –H | 945.5419, 927.5315, 799.4845, 783.4894, 637.4311, 475.3782, 391.2842 |

| 25 | Ginsenoside Rh2 | 667.4431 | C36H62O8 | 32.21 | 4.83 | 0.6 | – | 287.43 | +HCOO | 621.4360, 459.3832, 375.2896 |

| 26 | 20(R)-ginsenoside Rh2 | 667.4422 | C36H62O8 | 32.45 | 4.81 | −0.4 | 285.54 | 293.98/392.62 | +HCOO | 621.4375, 459.3851, 375.2905 |

| 27 | Compound K | 667.4417 | C36H62O8 | 31.65 | 5.21 | −1.5 | 271.98 | 276.41/388.49 | +HCOO | 621.4371, 459.3840, 375.2897 |

| 28 | Ginsenoside F2 | 829.4967 | C42H72O13 | 25.39 | 11.81 | 1.4 | – | 237.83/302.56 | +HCOO | 783.4886, 621.4359, 459.3832, 375.2890 |

| 29 | 20(S)-ginsenoside Rg3 | 829.4960 | C42H72O13 | 26.70 | 11.67 | 0.7 | – | 300.13 | +HCOO | 783.4880, 621.4355, 459.3827, 375.2891 |

| 30 | 20(R)-ginsenoside Rg3 | 829.4965 | C42H72O13 | 27.06 | 11.47 | 1.3 | – | 295.66 | +HCOO | 783.4889, 621.4360, 459.3831, 375.2892 |

| 31 | Notoginsenoside K | 991.5504 | C48H82O18 | 21.78 | 23.91 | 2.1 | 317.16 | 255.23/320.25 | +HCOO | 945.5428, 783.4876, 621.4359, 459.3838, 375.2896 |

| 32 | Ginsenoside Rd | 991.5503 | C48H82O18 | 19.49 | 22.58 | 2.0 | 251.66/324.56 | 328.04 | +HCOO | 945.5419, 783.4883, 621.4362, 459.3833, 375.2893 |

| 33 | Gypenoside XVII | 991.5457 | C48H82O18 | 21.78 | 23.80 | 2.7 | – | 258.01/328.27 | +HCOO | 945.5398, 783.4894, 621.4359, 459.3839, 375.2895 |

| 34 | Malonyl-floralginsenoside Rd5 | 1031.5453 | C51H84O21 | 20.44 | 23.61 | 2.0 | 261.14/344.17 | – | –H | 945.5426, 783.4905, 621.4380, 459.3852, 375.2907 |

| 35 | Malonyl-ginsenoside Rd | 1031.5457 | C51H84O21 | 20.41 | 24.04 | 2.4 | 334.76 | – | –H | 945.5412, 837.4073, 537.3445, 459.3826, 375.2895 |

| 36 | Ginsenoside Rb2 | 1123.5926 | C53H90O22 | 15.52 | 32.47 | 1.8 | 214.02/261.33/350.66 | 354.12/268.17 | +HCOO | 945.5417, 783.4887, 621.4360, 459.3830, 375.2894 |

| 37 | Ginsenoside Rb3 | 1123.5917 | C53H90O22 | 16.13 | 32.71 | 1.0 | 214.60/263.11/348.50 | 351.23 | +HCOO | 1077.5832, 945.5408, 783.4883, 621.4355, 459.3827 |

| 38 | Ginsenoside Rc | 1123.5923 | C53H90O22 | 13.94 | 30.01 | 1.5 | 215.10/261.54/341.14 | 343.52 | +HCOO | 1077.5841, 945.5419, 783.4887, 621.4357, 459.3831, 375.2726 |

| 39 | Ginsenoside Rb1 | 1153.6031 | C54H92O23 | 12.59 | 35.37 | 1.7 | 220.30/269.70/347.86 | 349.94 | +HCOO | 1107.5947, 945.5414, 783.4887, 621.4359, 459.3836, 375.2893 |

| 40 | Malonyl-ginsenoside Rc | 1163.5873 | C56H92O25 | 14.92 | 29.28 | 1.5 | 261.84/343.84 | – | –H | 1077.5842, 945.5413, 783.4887, 621.4361, 459.3834, 375.2894 |

| 41 | Malonyl-ginsenoside Rb2 | 1163.5869 | C56H92O25 | 16.58 | 31.13 | 1.2 | 264.96/353.80 | – | –H | 1077.5839, 945.5418, 783.4886, 621.4356, 459.3832, 375.2890 |

| 43 | Malonyl-ginsenoside Rb1 | 1193.5924 | C57H94O26 | 13.42 | 33.79 | −3.0 | 265.56/354.80 | – | –H | 1107.5916, 945.5397, 783.4877, 621.4357, 459.3831 |

| 36 | Ginsenoside Ra1 | 1209.6246 | C58H98O26 | 13.95 | 37.57 | −2.3 | 285.34/357.56 | – | –H | 1077.5819, 945.5401, 783.4885, 621.4361, 459.3838, 375.2898 |

| 44 | Ginsenoside Ra2 | 1255.6291 | C58H98O26 | 12.16 | 37.01 | −3.0 | 226.42/286.51/360.09 | 360.16 | +HCOO | 1209.6218, 1077.5805, 945.5397, 783.4883, 621.4362, 459.3834, 375.2897 |

| 45 | Notoginsenoside R4 | 1285.6453 | C59H100O27 | 10.30 | 39.65 | 1.5 | 227.71/279.113/364.62 | 286.08/366.79 | +HCOO | 1239.6371, 1107.5945, 945.5410, 783.4888, 621.4361, 459.3828, 375.2888 |

| 46 | Notoginsenoside T | 1371.6899 | C64H108O31 | 9.52 | 42.99 | 1.9 | 240.44/292.74/386.76 | – | –H | 1239.6380, 1107.5952, 945.5420, 783.4892, 621.4363, 459.3835, 375.2893, 353.1076 |

| 47 | Chikusetsusaponin IVa | 793.4382 | C42H66O14 | 18.52 | 13.75 | 0.3 | 181.65/219.46/283.64 | – | –H | 631.3833, 455.3516 |

| 48 | Chikusetsusaponin IV | 925.4795 | C47H74O18 | 16.71 | 14.09 | −0.8 | 194.61/248.74/328.11 | – | –H | 793.4378, 613.3742, 455.3531 |

| 49 | Pseudoginsenoside Rt1 | 925.4783 | C47H74O18 | 15.99 | 17.92 | 2.0 | 189.19/247.94/319.41 | – | –H | 925.4773, 763.4252, 613.3736, 455.3524 |

| 50 | Ginsenoside Ro | 955.491 | C48H76O19 | 13.72 | 21.59 | 0.3 | 198.21/248.92/321.10 | – | –H | 793.4360, 613.3727, 455.3513 |

| 51 | Ginsenoside Rk3 | 665.4258 | C36H60O8 | 24.29 | 5.01 | −1.9 | – | 278.51/384.64 | +HCOO | 619.4194, 457.3672 |

| 52 | Ginsenoside Rh4 | 665.4268 | C36H60O8 | 24.92 | 5.13 | 0.4 | – | 284.26 | 621.4085, 457.3698 | |

| 53 | 24(R)-Pseudoginsenoside Rt5 | 699.4331 | C36H62O10 | 10.59 | 6.73 | 0.9 |

269.81/310.45 |

273.59/381.70 | +HCOO | 653.4258, 491.3731, 415.3208 |

| 54 | Notoginsenoside T5 | 797.4683 | C41H68O12 | 22.99 | 9.65 | −1.3 | – | 300.07/423.71 | +HCOO | 751.4620, 619.4204, 457.3686 |

| 55 | Ginsenoside Rk1 | 811.4858 | C42H70O12 | 30.66 | 9.74 | 1.0 | 308.56 | 312.86 | +HCOO | 765.4780, 603.4255, 537.3936, 441.3723 |

| 56 | Ginsenoside Rg5 | 811.4863 | C42H70O12 | 31.12 | 9.47 | 1.7 | 314.06 | 318.11 | +HCOO | 765.4783, 603.4255, 439.3567 |

| 57 | 24(R)-Pseudoginsenoside F11 | 845.4912 | C42H72O14 | 10.26 | 11.48 | 1.0 | 295.46 | 296.87 | +HCOO | 799.4832, 653.4255, 491.3728, 415.3203 |

| 58 | 5,6-Didehydroginsenoside Rb1 | 1151.5861 | C54H90O23 | 11.60 | 35.52 | 0.5 | 220.13/270.43/344.97 | 277.78/346.56 | +HCOO | 1105.5779, 943.5248, 781.4721, 619.4200, 457.3673, 373.2732, 355.2632 |

Compound I: 6-O-β-D-(6′-acetyl)-glucopyranosyl-24-en-dammar-3,6,12,20(S)-tetraol.

Compound II: 6-O-(β-D-glucopyranosyl)-20-O-(β-D-xylopyranosyl)-3,6α,12,20(S)-tetrahydroxy dammar-24-ene.

The CCS values in bold indicate the most intense ones.

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

A total of 58 ginsenoside compounds (Fig. 2 and Table 1), either purchased from Shanghai Standard Biotech. Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) or isolated from the root of P. ginseng and P. notoginseng (structures were established by HRMS and NMR) [29,30], were used as the reference compounds. Acetonitrile, formic acid (FA), and ammonium acetate (AA; Fisher, Fair lawn, NJ, USA) were of LC-MS grade. Ultra-pure water was in-house prepared using a Milli-Q water purification system (Millipore, Bedford. MA, USA). Raw drug materials of white ginseng (the root and rhizome of P. ginseng) and red ginseng, collected in September of 2018, were from Baishan Lincun Chinese Medicine Development Co., Ltd. (Baishan, China). Their authentication was performed according to Flora of China and fingerprint analysis. Voucher specimens (WG20181101 and RG20181101) were deposited at the authors’ laboratory in Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Tianjin, China).

2.2. Sample preparation

The well pulverized, accurately weighed powder of WG and RG (1.5 g) was dispersed in 10 mL aqueous methanol (methanol: water = 70:30, V/V) and vortexed for 2 min. Samples were extracted in a water bath at 40 °C assisted with ultrasound for 30 min. After being centrifuged at a rotate speed of 4000 rpm for 10 min, the resultant supernatant was concentrated under reduced pressure, and further diluted in a 5-mL volumetric flask to the constant volume with the same solvent. The liquid, after the centrifugation process at 14,000 rpm for another 10 min, was used as the test solution (300 mg/mL). A quality control (QC) sample was prepared by pooling the equal volume of the test solutions of WG and RG for method development.

2.3. Offline 2D-LC/IM-QTOF-MS

An offline 2D-LC system was established by configuring hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) and reversed-phase ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (RP-UHPLC). Information regarding 16 candidate stationary phases, examined in this work, is provided in Table S1. The first-dimensional (1D) separation was conducted on an Agilent 1260 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) configured with an Acchrom XAmide column (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 5 μm) maintained at 30 °C. A binary mobile phase, consisting of acetonitrile (A) and 3 mM ammonium acetate in water (B), ran at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min following a gradient elution program: 0–10 min, 95%‒90% (A); 10–20 min, 90%‒88% (A); 20–30 min, 88%‒85% (A); 30–35 min, 85%‒80% (A), and 35–45 min, 80%‒77% (A); 45–48 min, 77%‒74% (A); 48–50 min, 74%‒70% (A); 50–53 min, 70%‒50% (A); 53–54 min, 50%–95% (A); and 54–64 min, 95% (A). The injection volume was 20 μL. The PDA detector monitored the signals at 203 nm for ginsenosides. Aiming to retain the separation from 1D-HILIC and to avoid peak splitting, peaks-oriented fractionation was conducted, which finally led to 13 collections of the eluent for each species. Solvents were removed under a steady flow of N2 at ambient temperature (25 °C). The residues were reconstituted in 100 μL of 70% methanol and further centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min. The resultant supernatants were used as the samples ready for the second-dimensional (2D) separation in RP mode. The 2D-RP separation was performed on an ACQUITY UPLC I-Class/Vion IMS-QTOF system (Waters Corporation, Manchester, UK). An HSS T3 column (2.1mm × 100 mm, 1.8 μm) maintained at 35 °C was used. A binary mobile phase, containing 0.1% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile (B), ran consistent with the following gradient program: 0–2 min, 15%–20% (B); 2–7 min, 20%–30% (B); 7–8 min, 30%–32% (B); 8–18 min, 32%–34% (B), 18–21 min, 34%–40% (B). 21–31 min, 40%–60% (B), 31–33 min, 60%–95% (B), and 33–34 min, 95% (B). The flow rate of 0.3 mL/min was set.

High-definition MSE (HDMSE) data in Continnum format (uncorrected) were acquired in the negative ESI, “Sensitivity” mode. The LockSpray ion source parameters used are as follows: capillary voltage, −2.0 kV; cone voltage, 20 V; source offset, 80 V; source temperature, 120 °C; desolvation temperature, 500 °C; desolvation gas flow (N2), 800 L/h; and cone gas flow (N2), 50 L/h. Data calibration was conducted using an external reference (LockSpray™) by constantly infusing 200 pg/μL leucine enkephalin (LE; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at a flow rate of 10 μL/min, The parameters for the travelling wave IM separation were the default. CCS was calibrated according to the manufacturer’s guidelines using a mixture of calibrants [31]. HDMSE data covered a mass range of m/z 350–1500 at 0.3 s per scan. The low collision energy was set at 6 eV and the high energy ramp was 80–100 eV. Data acquisition and processing were performed by the UNIFI™ 1.9.3.0 software (Waters).

Simplified method validation, referring to the intra-day and inter-day precision for both 1D and 2D separations, repeatability, and approximately the lowest concentration of identification (the lowest amount at which sufficient MS2 ions are obtained suitable for the structural elucidation), was conducted as we previously reported [30].

2.4. Establishment of an in-house ginsenoside database incorporated in UNIFI™

Literature with respect to the phytochemistry studies of the entire Panax genus (2013–2018), as the continuity of our review article [26], was searched for against multiple available databases (e.g. Web of Science, SciFinder, and CNKI) to summarize all the known ginsenosides. The in-house library of ginsenosides was thus established with the information of trivial name, molecular formula, and chemical structure of each compound. First, the structure information was input into an EXCEL file according to a required format. Then the structure of each ginsenoside was drawn using ChemDraw Professional, which was subsequently saved as an .mol file. The .mol file was named with the trivial name consistent with the EXCEL file. Finally, the EXCEL file and all structure files were incorporated into the UNIFI™ software.

2.5. Automated annotation of the HDMSE data

Automated annotation of the HDMSE data was achieved using UNIFI™ by searching the incorporated ginsenoside library. Uncorrected HDMSE data of WG and RG were corrected by the LockMass at m/z 554.2620 (ESI‒). Information of detailed settings for the data processing method by UNIFI™ is presented in Table S2. Programmed peak annotation was accomplished efficiently which generated a table of the primarily identified components. Adduct ions filtering and MS2 data analysis were further utilized to remove false positives and confirm the identities.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Necessity for the development of a dimension-enhanced strategy to enable comprehensive profiling and characterization of plant metabolites

Inherent complexity of botanical metabolome indeed has raised a daunting challenge. A powerful method applicable to TCM multicomponent profiling can be developed by enhancing the dimensions in chromatography and/or MS separation. On one hand, multi-dimensional chromatography by applying orthogonal mechanisms of separation, such as HILIC × RPLC, SEC × RPLC, and ILC × RPLC[32], can better resolve the components that are easily coeluted on the RP columns, and meanwhile, elevate the ion response in MS monitoring [7]. On the other hand, IMS can provide additional separation for the ionized components based on their charge state, size, and shape, by which the CCS value can be offered having the potential to differentiate isomeric herbal metabolites [24,28]. High-resolution MS, by QTOF, IT-TOF, Q-Orbitrap, and LTQ-Orbitrap, greatly enhances the reliability in structural identification by removing collections of false positives [33]. Therefore, it becomes indispensable to develop dimension-enhanced strategies, aiming to comprehensively deconvolute the complexity of medicinal herb metabolomes.

3.2. Establishment, optimization, evaluation, and method validation of an offline 2D-LC/MS system dedicated to ginsenoside analysis

To tackle the insufficiency encountered in the comprehensive characterization of TCM multicomponents, we propose establishing dimension-enhanced approaches, in which 2D-LC enables orthogonal chromatographic separation and IM-QTOF-MS facilitates IM separation providing additional information of drift time (converted into CCS). And accordingly, multi-dimensional information, including tR in each chromatography (tR-1D, tR-2D), high-accuracy MS1 and MS2 data, and CCS, can be obtained to support comprehensive profiling and characterization of the multicomponents of TCM or natural products.

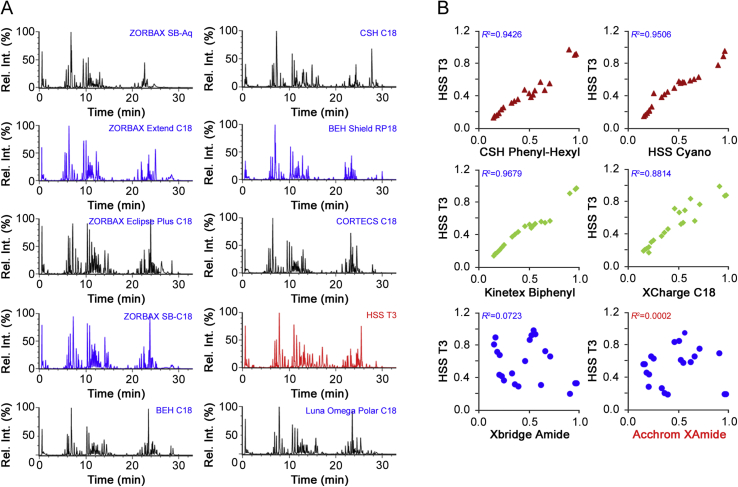

2D-LC in the offline mode was selected to enable dimension-enhanced chromatographic separation of ginsenosides [7,24]. Key parameters that may affect the chromatography performance in each dimension (1D or 2D), involving the stationary phase, mobile phase, column temperature, and gradient eluting program, were optimized in sequence by single-factor experiments. Because of the high selectivity of RP and impressive role of retention time (tR) in structural elucidation (such as to differentiate isomers), RP was used as 2D chromatography coupling to MS detection. Ten C18-alkyl bonding stationary phases (i.e., ZORBAX SB-C18, ZORBAX SB-Aq, ZORBAX Extend C18, ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18, BEH C18, BEH Shield RP18, CSH C18, CORTECS C18, HSS T3, and Luna Omega Polar C18; Table S1) that involved different silica gel cores (fully porous or core-shell) and different bonding technologies from three vendors (Agilent, Waters, and Phenomenex), were examined. By considering the overall separation of major ginsenosides, in contrast, HSS T3 enabled a balanced distribution effect with better peak symmetry (Fig. 3). HSS T3 is a three-bond C18-bonding high-strength silica gel column with a relatively low carbon content (11%), thus enduring pure aqueous phase elution to enhance the retention of polar structures. Further optimizations finally helped establish much more satisfactory 2D chromatography by using acetonitrile-0.1% FA as the mobile phase (Fig. S1) and the HSS T3 column at 35 °C (Fig. S2). Subsequent selection of the 1D stationary phase was based on the selectivity difference with HSS T3 by calculating the linearity regression correlation coefficient (R2) of the relative retention time (0–1) determined on two columns for 21 ginsenosides. In this stage, six different mechanisms of chromatographic columns, i.e., Xbridge Amide, Acchrom XAmide, HSS Cyano, CSH Phenyl-Hexyl, Kinetex Biphenyl, and XCharge C18, were screened. It was found that selectivity difference against HSS T3 for ginsenosides was consistent with the order: Acchrom XAmide > Xbridge Amide > XCharge C18 > CSH Phenyl-Hexyl > HSS Cyano > Kinetex Biphenyl. It indicated that HILIC columns were more orthogonal to the RP-mode HSS T3 in revolving ginsenosides. Comparatively, Acchrom XAmide was a desirable choice. And the satisfactory 1D chromatographic separation was achieved using acetonitrile/3 mM AA as the mobile phase (Fig. S3) and the Acchrom XAmide column set at 30 °C (Fig. S4).

Fig. 3.

Selection of stationary phases for the offline comprehensive 2D-LC system dedicated to good resolution of ginsenosides. (A) Showing the base-peak intensity chromatograms; (B) displaying scatter plots of 21 reference ginsenosides by the relative retention time determined on each candidate 1D column and the 2D HSS T3 column.

Detection of ginsenosides was performed on a Vion™ IMS-QTOF high-resolution LC-MS system, and two key source parameters (capillary voltage and cone voltage) together with ramp collision energy (RCE), were optimized by evaluating the peak areas of six reference compounds, i.e., 20-O-glucosyl-ginsenoside Rf and ginsenoside Re (PPT), ginsenoside Rd (PPD), ginsenoside Ro (OA), 24(R)-pseudoginsenoside F11 (OT), and malonylginsenoside Rd (malonylated). They can include the common five subtypes for ginsenosides. Capillary voltage (1.5–3.5 kV) and cone voltage (0–80 V) were tested. The ion response of all six index compounds positively correlated with the capillary voltage values (Fig. S5). However, the intensity variation by triplicate injections became larger at high levels of capillary voltage. Aiming to maintain a stable performance, we set capillary voltage at 2.0 kV. Cone voltage could induce an alternating trend in ion response, and 20 V could enable the highest response for all ginsenosides. Ramp collision energy, rather than a fixed value, has the potential to acquiring more balanced MS2 spectrum [30], and thus is considered. RCEs, including 20–40 eV, 30–50 eV, 40–60 eV, 60–80 eV and 80–100 eV, were compared by observing the precursor-to-sapogenin ion transition. The fragmentation degree (richness of fragments) of ginsenosides with different numbers of sugars was discriminated even at the same RCE. High mass of ginsenosides became difficult to dissociate. We finally selected RCE of 80–100 eV as diversified product ions could be obtained for most of ginsenosides (Fig. S6).

Orthogonality of the developed 2D-LC system was assessed by calculating the distribution of 76 ginsenosides based on the asterisk equations reported by Camenzuli and Schoenmakers (Supporting Information) [34]. By calculating the spreading of all 76 components around four crossing lines (Z+, Z-, Z1, Z2; Eq. (2) to Eq. (9)) using the relative retention time (tR,norm; Eq. (1)), four Z parameters were calculated at 0.75, 0.98, 0.91, and 0.85, based on which orthogonality () of the 2D-LC system was 0.76 (Fig. S7). In addition, averaged peak width at baseline in 1D and 2D chromatography was approximately 0.80 min and 0.24 min. Peak capacity in each dimension was thus 66 (1nc) and 138 (2nc), respectively. We could deduce effective peak capacity of the HILIC × RP system was estimated at 976 (circle time in 2D separation was replaced by the averaged collection time, 4.07 min) [35]. We can draw a conclusion the developed offline 2D-LC system, by configurating an Acchrom XAmide column (1D) and an HSS T3 column (2D), could greatly improve the resolution of multicomponents from WG and RG. Two cases are illustrated in Fig. S8.

To testify the system suitability of the developed offline 2D-LC/MS approach and simultaneously consider its purpose for qualitative analysis, simplified method validation experiments were performed in terms of precision, repeatability, and limit of detection. Results could demonstrate the offline 2D-LC system established was precise and stable, and had high sensitivity for characterizing ginsenosides. Intra-/inter-day precision, evaluated by five peaks (tR 6.47, 7.25, 11.05, 27.26, and 36.34 min) in 1D (HILIC-UV) and five representative components (ginsenosides Re, -Rd, notoginsenosides Rt, -R2, and malonylginsenoside Rd) in 2D (RP-UHPLC/MS) separation, varied among 0.68%–2.25%/1.58%–3.53% and 1.96%–3.40%/3.36%–7.46%, respectively. Repeatability among six copies of Fr. 7 using four compounds (ginsenosides Re, -Ro, and two isomers of acetylginsenoside Rg1) ranged from 7.12% to 9.69%. The lowest concentrations for identification under the current condition (defined at the lowest amount of analyte that can be identified by the standardized workflows of UNIFI) determined for six ginsenosides (notoginsenoside R1, ginsenosides Re, -Rb1, -Rc, -Rd, and -Ro) varied among 2.0–2.5 ng.

3.3. Comparison of the performance of HDMSE and MSE in profiling and characterizing ginsenosides using WG

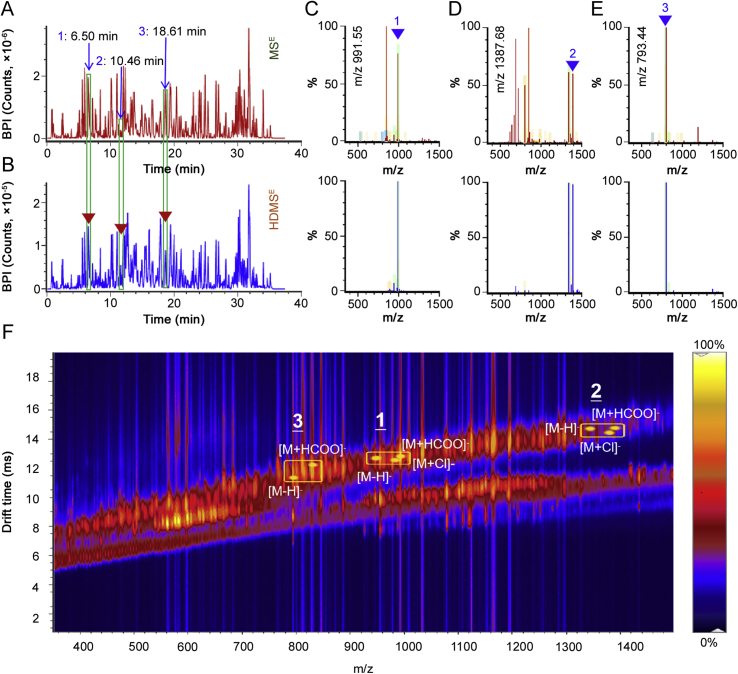

The Waters QTOF instruments (such as the Xevo G2-S and G2-XS series) enable a patent DIA technology, namely MSE, by which the MS/MS fragmentation information of the precursors across the whole scan range can be recorded [22]. The advanced Vion IMS-QTOF mass spectrometer, utilized in this work, provides an additional choice when selecting MSE, dubbed HDMSE [14]. The ion-mobility cell is installed ahead of quadrupole (Q), and thus the precursor ion species can be primarily separated by IM based on the shape, charge, and size, prior to entering quadrupole, making the precursors less complicated. Here we assessed the performance of HDMSE and MSE in profiling of ginsenosides from WG. Fig. 4 shows base peak intensity (BPI) chromatograms and the full-scan spectra of three peaks (1: 6.50 min, m/z 991.55; 2: 10.46 min, m/z 1387.68; 3: 18.61 min, m/z 793.44) recorded between MSE (upper) and HDMSE (lower), as well as a 2D-driftscope plot. Evidently, the total ion intensity obtained by HDMSE (in BPI) was almost an order of magnitude lower than that of MSE (2.4e5 VS 3.5e6; Figs. 4A and B), which might be due to scattering collisions between the ginsenoside ions and drift gas of IM. Moreover, the full-scan spectra of three components displayed much less interference by HDMSE acquisition than MSE, although the ion intensity acquired between two modes was not sharply different (Fig. 4C through Fig. 4E). In addition, because of the addition of IM separation, co-eluting ions got further separation and the drift time exhibited correlation with m/z for three components (t3 < t1 < t2). Different adducts of three compounds are annotated in Fig. 4F.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the performance between MSE (upper) and HDMSE (lower) for ginsenoside analysis. The base peak intensity chromatograms (A and B), the full-scan spectra of three peaks (C through E), and a 2D-driftscope plot (F), are illustrated.

3.4. Streamlined workflows for intelligent identification of ginsenosides by UNIFI™

The software, UNIFI™, controlled the UHPLC/IM-QTOF-MS instrument for data acquisition, and was utilized to process the high-accuracy HDMSE data. Cephalocaudal workflows, by applying Vion IMS-QTOF and UNIFI™ to qualitatively characterizing the components of natural products, are here described.

Step 1: Creation/editing of analysis method. A RP-UHPLC/IM-QTOF-HDMSE operating in the negative ESI mode was set up by optimizing the parameters of chromatography and MS.

Step 2: Data acquisition. The negative HDMSE data of all analytes and LE were recorded.

Step 3: Data input and elaboration of data processing method. All HDMSE data were input into the UNIFI™ software (Table S2).

Step 4: Data processing. The defined data processing method and the in-house ginsenoside library were utilized to annotate the HDMSE data.

Step 5: Confirming of the identification results. To the components listed in “Identified Compounds”, the results should be carefully checked to remove false positives. The ginsenosides involved in “Unknown Compounds” could be characterized manually.

We highlight the necessity of developing an in-house database specific for ginsenoside characterization. Although the TCM library of UNIFI™ records the major components (6399 in total) for almost all the TCM species in Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2015 edition), it is far insufficient for comprehensive identification of ginsenosides from WG and RG. The database of seven Panax-derived TCM in total records 138 compounds, and 112 thereof are ginsenosides. In this work, we established a ginsenoside database which records 504 ginsenosides that have been isolated from the Panax genus up to 2018. Specific database can favor the characterization of more compounds.

3.5. Comprehensive identification of ginsenosides from WG and RG by the intelligent workflows

The versatile data processing platform UNIFI™, by searching the incorporated in-house ginsenoside library, achieved an efficient identification of the ginsenosides simultaneously from WG and RG. Based on the streamlined workflows, as a result, we could identify or tentatively characterize 323 ginsenosides, including 286 compounds from WG and 306 from RG, and 125 thereof have not been isolated from the Panax genus (Table S3). These characterized ginsenosides, based on the difference on sapogenin and the presence of malonyl, were reasonably classified into six subclasses: PPD, PPT, OA, OT, malonylated, and others [26]. Overall, characteristic neutral loss (NL) corresponding to the malonyl substituent (44.01 Da and 86.00 Da) and sugars (162.05 Da for Glc, 146.06 Da for Rha, 132.04 Da for Xyl/Ara, and 176.03 Da for GlurA), and typical product ions associated with the sapogenins (m/z 475.38/391.29 for PPT, 459.38/375.29 for PPD, 455.35 for OA, and 491.37/415.32 for OT), were readily observed, which in general are consistent with the CID (collision-induced dissociation) features we have previously reported [7,11,25,30].

Table 1 lists the retention time of 2D-LC, CCS, and MS2 information of 58 ginsenoside reference compounds. Retention time in 1D HILIC (tR-1D) and CCS are two dimensions of information newly provided in the current work. In particular, IM-derived CCS is beneficial to more reliable assignment of the known components [22]. In case of these 58 ginsenoside compounds, the CCS values of both [M‒H]‒ and [M + HCOO]‒ forms for 26 compounds could be determined. In contrast, the FA-adduct was more easily generated, while malonylginsenosides only gave rich deprotonated precursors. Notably, in some cases, more than one mobility peak could be observed corresponding to a unique compound (with the same m/z value) on the Vion IMS-QTOF instrument, which was similar to the results determined on a SYNAPT G2-Si HDMS system [24]. Taking ginsenoside Rb1 as an example, its mobility trace displayed three peaks (a‒c) with drift time observed at 8.68 ms, 10.69 ms, and 13.70 ms, respectively, consistent with three “identified components” with very similar retention time (Fig. S9). The complex ion clusters around m/z 1107.5966 indicated the presence of at least [M‒H]‒ and [2M‒2H]2‒ (together with their isotope peaks), which corresponded to mobility peaks b and a. Peak c (drift time 13.70 min) was tentatively inferred as a fragment of [2M‒H]‒ generated in the ion-mobility cell with the same m/z value as [M‒H]‒. These “three components” (generated from one compound) had almost the same MS2 spectra deconvoluted by UNIFI™. It exhibits the multiformity of mobility trace for ginsenosides.

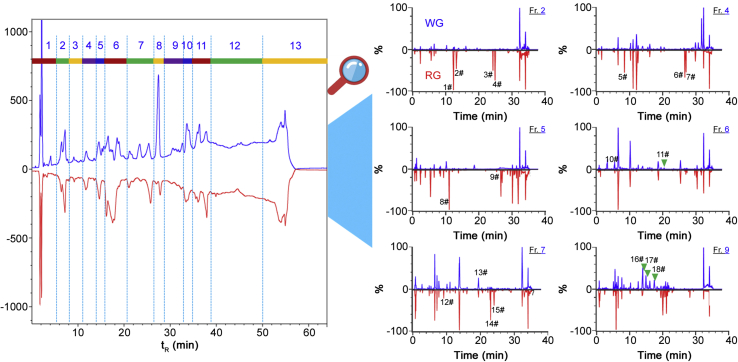

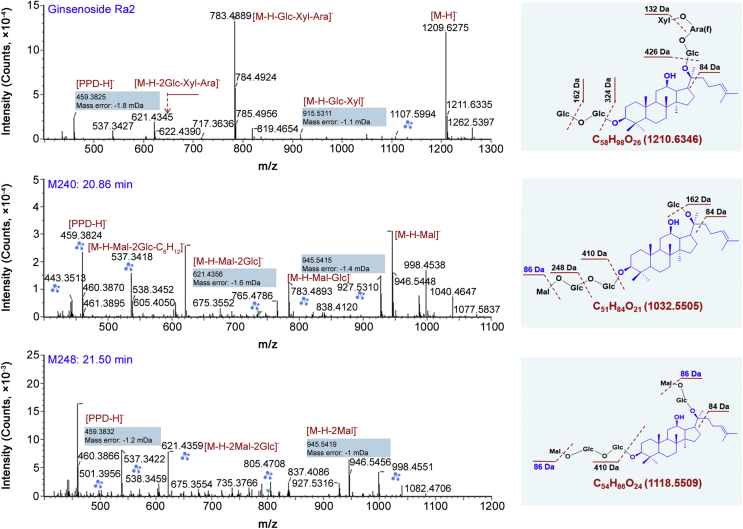

Ginsenosides belonging to the PPD and PPT types occupied top two largest proportions, with 119 (37%) and 87 (27%) compounds identified or tentatively characterized. Using the characterization of ginsenoside Ra2 (152#: tR 12.11 min) as a case (Fig. 5), the deconvoluted MS2 spectra gave diverse product ions, which were easily ascribed to the NL fragments. The base-peak fragment at m/z 783.4889 may be a product ion with 20-sugar chain eliminated. NL of C6H12 (84 Da) was also observed, which was assigned on the C17-side chain with the chemical bond C20–C22 broken [9]. The sapogenin ions m/z 459.3825/375.2895 were the ions associated with the PPD skeleton (Table S3). As a characteristic ginsenoside subcategory with potential anti-diabetic property, 17 malonylginsenosides (5% of the total) were characterized, for which preferable NLs of CO2 (44 Da) and the whole malonyl substituent C3H2O3 (86 Da) were the most important diagnostic information [11]. Here, the characterizations of two unknown compounds 240# (tR 20.86 min, m/z 1031.5453) and 248# (tR 21.50 min, m/z 1117.5450), separately representing mono-malonyl and di-malonyl ginsenosides, were illustrated (Fig. 5). Under the current condition, CID of both two malonylginsenosides easily eliminated the malonyl substituent, and gave diverse product ions consistent with ginsenoside Rd (m/z 945, 927, 783, 621, 537, 459, and 375). The product ions matched with the theoretical ones were marked with a claw symbol, and key cleavages were indicated on the structures. Therefore, they could be tentatively characterized as malonylginsenoside Rd or isomer (PPD-Glc-Glc-Glc-Mal.) and di-malonylginsenoside Rd or isomer (PPD-Glc-Glc-Glc-Mal.-Mal.). Notably, malonylginsenosides are easily transformed into the neutral forms and thus remain rare in RG [27]. OA-type ginsenosides represent another subclass of characteristic components for P. ginseng [26,36]. A total of 21 OA ginsenosides (7% of the total) could be characterized. Characterization of ginsenoside Ro was illustrated (Fig. S10). Its CID generated versatile product ions as a result of NL of Glc (m/z 793), Glc + CO2+H2O (m/z 731), and the generation of sapogenin ion m/z 455.35. These features were useful for characterizing an unknown compound, 114# (tR 9.62 min; m/z 1117.5452). Three OT-type ginsenosides (1% of the total), involving 104# (tR 8.93 min; m/z 861.4865 for [M + HCOO]‒), 122# (tR 10.24 min; m/z 845.4921 for [M + HCOO]‒), and 128# (tR 10.57 min; m/z 699.4337 for [M + HCOO]‒), were detected. The remaining 76 compounds (24% of the total) were all classified into the others, which exhibited diversified sapogenin ions and should be a crucial source for the discovery of novel natural compounds. The established 2D-LC/IM-QTOF-MS approach can also be used as a magnifier to explore the differentiated compounds between WG and RG. Fig. 6 displays six remarkably discriminated fractions and marks 18 potential differentiated compounds between WG and RG.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of the HILIC profiles showing six typical fractions (Frs. 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 9) between white ginseng (WG; upper in blue) and red ginseng (RG; lower in red). Potential differential ginsenosides are annotated using six fractionated samples: 1#, Rh1; 2#, 20(R)-Rh1; 3#, Rk3, 4#, Rh4; 5#: 6′-O-acetyl-Rg1; 6#, Rg3; 7#, 20(R)-Rg3; 8#, noto-R2; 9#, F2; 10#, floralginsenoside A (or isomer); 11#, m-Rd; 12#, 6‴-O-acetylginsenoside Re; 13#, Rd; 14#, quinquenoside III (or isomer), 15#, p-Rc1 (or isomer); 16#, Ro; 17#, m-Rc; 18#, m-Rb3 isomer.

Fig. 5.

Automated annotation of the MS2 spectra of three representative ginsenosides (a reference compound, ginsenoside Ra2; two unknown PPD-type saponins 204# and 248#) by UNIFI™ that incorporates an in-house ginsenoside library. The claw symbol indicates the ions matched with the theoretical fragments.

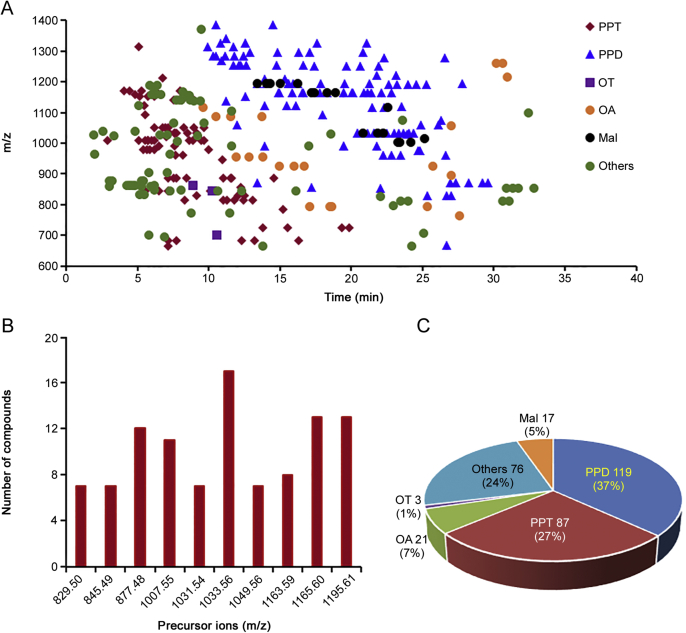

A summary of the structure features, according to the identification results, was made (Fig. 7). On one hand, the retention behavior of ginsenosides exhibited a certain of sapogenin specificity. In general, extension of the attached sugars (showing larger m/z) could weaken the retention of ginsenosides on the RP column. For the PPD- and PPT-types that account for 64% of the total amount, the PPT ginsenosides were eluted earlier than ginsenosides of PPD type. Malonyl substitution could increase the polarity of ginsenosides, and under the current chromatography condition using 0.1% FA in mobile phase, malonylginsenosides (no matter they involve a PPT or PPD sapogenin) were eluted along with the predominant PPD type (Fig. 7A). On the other hand, isomerism is very popular for ginsenosides. Ten precursor masses shown in Fig. 7B all corresponded to more than five identified ginsenosides. How to discriminate isomers in ginsenoside characterization remains a great challenge as most of the isomers gave very similar MS2 spectra. Large-scale prediction of retention time and CCS might be practical solutions, which will be involved in our future work to achieve the differentiation of isomeric ginsenosides [23].

Fig. 7.

A summary of the structure features of the ginsenosides identified from white ginseng (WG) and red ginseng (RG). (A) a 2D-scatter plot (m/z VS tR) of all the 323 ginsenosides; (B) popular isomerism for ginsenosides using ten masses; (C) a pie chart showing the proportion of different ginsenoside subclasses.

By comparing this work with our previous researches or the other reports [7,11,13,22,25,27,30], this integral approach established in the current work is dimension enhanced, enabling four-dimensional separations and giving more structure information. Moreover, this study reports an in silico efficient peak annotation strategy, which can greatly improve the efficiency of analysis and render the identification results reproducible. We will endeavor to improve the reliability of known ginsenosides assignment by establishing “Multi-dimensional Information Ginsenoside Library” in our future work.

4. Conclusion

A dimension-enhanced strategy was presented, in the current work, as a solution to the insufficiencies encountered in the comprehensive metabolites profiling and characterization for herbal medicine. By coupling a powerful Vion IMS-QTOF hybrid high-resolution mass spectrometer to the well-established offline 2D-LC system, four-dimensional separations were achieved offering richer structural information (tR-1D, tR-2D, MS1, MS2, and CCS). Integration of HILIC and RP separations achieved well resolution of ginsenosides simultaneously from WG and RG (orthogonality, 0.76; effective peak capacity, 976). Streamlined data processing by UNIFI™ enabled automated peak annotation with greatly enhanced efficiency and producibility. A specific in-house ginsenoside library, recording 504 known ginsenoside entries, was incorporated into UNIFI, which could render the characterization results more reliable by both MS1 and MS2 (predicted fragments) matching. A ginsenoside library consisting of 58 reference compounds also helped confirm the identities of major ginsenosides from WG and RG. We could finally identify or tentatively characterize 323 saponins (including 286 compounds from WG and 306 from RG), and 125 thereof have not been isolated from the Panax genus.

This integral strategy showed superiority over conventional approaches in three aspects: i) additional 1D chromatography and IM separation greatly expand peak capacity; ii) IM-derived CCS determination provides more dimensional information useful for structural elucidation, particularly having the potential to discriminate isomers; iii) in-house library-driven automated peak annotation enhances both the reliability and efficiency in ginsenoside identification. This work offers more possibilities for the systematic exposure and precise identification of plant metabolites.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81872996), the State Key Research and Development Project (Grant No. 2017YFC1702104), the State Key Project for the Creation of Major New Drugs (2018ZX09711001-009-010), and the Tianjin Municipal Education Commission Research Project (Grant No. 2017ZD07).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Xi'an Jiaotong University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2019.11.001.

Contributor Information

Wenzhi Yang, Email: wzyang0504@tjutcm.edu.cn.

Dean Guo, Email: daguo@simm.ac.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Yang W.Z., Zhang Y.B., Wu W.Y. Approaches to establish Q-markers for the quality standards of traditional Chinese medicine. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2017;7:439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yan Y., Song Q.Q., Chen X.J. Simultaneous determination of components with wide polarity and content ranges in Cistanche tubulosa using serially coupled reverse phase-hydrophilic interaction chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 2017;1501:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2017.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh A., Bajpai V., Kumar S. Analysis of isoquinoline alkaloids from Mahonia leschenaultia and Mahonia napaulensis roots using UHPLC-Orbitrap-MSn and UHPLC-QqQLIT-MS/MS. J. Pharm. Anal. 2017;7:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garran T.A., Ji R.F., Chen J.L. Elucidation of metabolite isomers of Leonurus japonicus and Leonurus cardiaca using discriminating metabolite isomerism strategy based on ultra-high performance liquid chromatography tandem quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 2019;1598:141–153. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2019.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganzera M., Sturm S. Recent advances on HPLC/MS in medicinal plant analysis -An update covering 2011−2016. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018;147:211–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pirok B.W.J., Stoll D.R., Schoenmakers P.J. Recent developments in two-dimensional liquid chromatography: fundamental improvements for practical applications. Anal. Chem. 2019;91:240–263. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b04841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qiu S., Yang W.Z., Shi X.J. A green protocol for efficient discovery of novel natural compounds: characterization of new ginsenosides from the stems and leaves of Panax ginseng as a case study. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2015;893:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2015.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaiswal Y., Liang Z.T., Ho A. Tissue-based metabolite profiling and qualitative comparison of two species of Achyranthes roots by use of UHPLC-QTOF MS and laser micro-dissection. J. Pharm. Anal. 2018;8:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar S., Singh A., Kumar B. Identification and characterization of phenolics and terpenoids from ethanolic extracts of Phyllanthus species by HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS. J. Pharm. Anal. 2017;7:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J.Y., Wang Z.J., Zhang Q. Rapid screening and identification of target constituents using full scan-parent ions list-dynamic exclusion acquisition coupled to diagnostic product ions analysis on a hybrid LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Talanta. 2014;124:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2013.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi X.J., Yang W.Z., Qiu S. An in-source multiple collision-neutral loss filtering based nontargeted metabolomics approach for the comprehensive analysis of malonyl-ginsenosides from Panax ginseng, P. quinquefolius, and P. notoginseng. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2017;952:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2016.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan H.Q., Yang W.Z., Yao C.L. Mass defect filtering-oriented classification and precursor ions list-triggered high-resolution mass spectrometry analysis for the discovery of indole alkaloids from Uncaria sinensis. J. Chromatogr. A. 2017;1516:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2017.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lai C.J.S., Tan T., Zeng S.L. An integrated high resolution mass spectrometric data acquisition method for rapid screening of saponins in Panax notoginseng (Sanqi) J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2015;109:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2015.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jia L., Zuo T.T., Zhang C.X. Simultaneous profiling and holistic comparison of the metabolomes among the flower buds of Panax ginseng, Panax quinquefolius, and Panax notoginseng by UHPLC/IM-QTOF-HDMSE-based metabolomics analysis. Molecules. 2019;24:2188. doi: 10.3390/molecules24112188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen T.F., Ye J., Li H.L. Hybrid multidimensional data acquisition and data processing strategy for comprehensive characterization of known, unknown and isomeric compounds from the compound Dan Zhi Table by UPLC-TWIMS-QTOFMS. RSC Adv. 2019;9:8714–8727. doi: 10.1039/c8ra10100k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pettit M.E., Donnarumma F., Murray K.K. Infrared laser ablation sampling coupled with data independent high resolution UPLC-IM-MS/MS for tissue analysis. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2018;1034:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2018.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He M.Z., Jia J., Li J.M. Application of characteristic ion filtering with ultra-high performance liquid chromatography quadrupole time of flight tandem mass spectrometry for rapid detection and identification of chemical profiling in Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. J. Chromatogr. A. 2018;1554:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye H., Zhu L., Sun D. Nontargeted diagnostic ion network analysis (NINA): a software to streamline the analytical workflow for untargeted characterization of natural medicines. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016;131:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin Y., Wu C.S., Zhang J.L. A new strategy for the discovery of epimedium metabolites using high-performance liquid chromatography with high resolution mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2013;768:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiao X., Lin X.H., Ji S. Global profiling and novel structure discovery using multiple neutral loss/precursor ion scanning combined with substructure recognition and statistical analysis (MNPSS): characterization of terpene-conjugated curcuminoids in Curcuma longa as a case study. Anal. Chem. 2016;88:703–710. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zapadka M., Kaczmarek M., kupcewicz B. An application of QSRR approach and multiple linear regression method for lipophilicity assessment of flavonoids. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019;164:681–689. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi X.J., Yang W.Z., Qiu S. Systematic profiling and comparison of the lipidomes from Panax ginseng, P. quinquefolius, and P. notoginseng by ultrahigh performance supercritical fluid chromatography/high-resolution mass spectrometry and ion mobility-derived collision cross section measurement. J. Chromatogr. A. 2018;1548:64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Z.W., Shen X.T., Tu J. Large-scale prediction of collision cross-section values for metabolites in ion mobility-mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2016;88:11084–11091. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang H., Jiang J.M., Zheng D. A multidimensional analytical approach based on time-decoupled online comprehensive two-dimensional liquid chromatography coupled with ion mobility quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry for the analysis of ginsenosides from white and red ginsengs. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019;163:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang W.Z., Qiao X., Li K. Identification and differentiation of Panax ginseng, Panax quinquefolium, and Panax notoginseng by monitoring multiple diagnostic chemical markers. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2016;6:568–575. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang W.Z., Hu Y., Wu W.Y. Saponins in the genus Panax L. (Araliaceae): a systematic review of their chemical diversity. Phytochemistry. 2014;106:7–24. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Z., Xia J., Wang C.Z. Remarkable impact of acidic ginsenosides and organic acids on ginsenoside transformation from fresh ginseng to red ginseng. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016;64:5389–5399. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b00963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H., Zheng D., Li H.H. Diagnostic filtering to screen polycyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinols from Garcinia oblongifolia by ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography coupled with ion mobility quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2016;912:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2016.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y., Han L.F., Sakah K.J. Bioactive protopanaxatriol type saponins isolated from the roots of Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F. H. Chen. Molecules. 2013;18:10352–10366. doi: 10.3390/molecules180910352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang W.Z., Zhang J.X., Yao C.L. Method development and application of offline two-dimensional liquid chromatography/quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry-fast data directed analysis for comprehensive characterization of the saponins from Xueshuantong Injection. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016;128:322–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paglia G., Angel P., Williams J.P. Ion mobility-derived collision cross section as an additional measure for lipid fingerprinting and identification. Anal. Chem. 2015;87:1137–1144. doi: 10.1021/ac503715v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ji S., Wang S., Xu H.S. The application of on-line two-dimensional liquid chromatography (2DLC) in the chemical analysis of herbal medicines. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018;160:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang A.H., Sun H., Yan G.L. Recent developments and emerging trends of mass spectrometry for herbal ingredients analysis. Trends Anal. Chem. 2017;94:70–76. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camenzuli M., Schoenmakers P.J. A new measure of orthogonality for multi-dimensional chromatography. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2014;838:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2014.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li X.P., Stoll D.R., Carr P.W. Equation for peak capacity estimation in two-dimensional liquid chromatography. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:845–850. doi: 10.1021/ac801772u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shin B.K., Kwon S.W., Park J.H. Chemical diversity of ginseng saponins from Panax ginseng. J. Ginseng Res. 2015;39:287–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.