Abstract

Immune cells are present in normal breast tissue and in breast carcinoma. The nature and distribution of the immune cell subtypes in these tissues are reviewed to promote a better understanding of their important role in breast cancer prevention and treatment. We conducted a review of the literature to define the type, location, distribution, and role of immune cells in normal breast tissue and in in situ and invasive breast cancer. Immune cells in normal breast tissue are located predominantly within the epithelial component in breast ductal lobules. Immune cell subtypes representing innate immunity (NK, CD68+, and CD11c+ cells) and adaptive immunity (most commonly CD8+, but CD4+ and CD20+ as well) are present; CD8þs cells are the most common subtype and are primarily effector memory cells. Immune cells may recognize neoantigens and endogenous and exogenous ligands and may serve in chronic inflammation and immunosurveillance. Progression to breast cancer is characterized by increased immune cell infiltrates in tumor parenchyma and stroma, including CD4+ and CD8+ granzyme B+ cytotoxic T cells, B cells, macrophages and dendritic cells. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer may serve as prognostic indicators for response to chemotherapy and for survival. Experimental strategies of adoptive transfer of breast tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte may allow regression of metastatic breast cancer and encourage development of innovative T-cell strategies for the immunotherapy of breast cancer. In conclusion, immune cells in breast tissues play an important role throughout breast carcinogenesis. An understanding of these roles has important implications for the prevention and the treatment of breast cancer.

Keywords: breast tissue, breast cancer breast immunology, breast immune cells, intraepithelial lymphocytes, breast ductal cells, immunotherapy for breast cancer, breast cancer immunology, tumor immunology, tumor infiltrating lymphocytes

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women with over 316,000 cases annually in the United States.1 Most breast cancers arise in the breast milk ducts, either as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), or as invasive ductal carcinoma. Breast cancer develops through the accumulation of mutational changes, most commonly in the ductal epithelium. The development and progression of these changes can be influenced by multiple elements in the ductal microenvironment, both cellular such as immune cells, adipocytes, fibroblasts, and the microbiome, and soluble including growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, prostaglandins, and others. Among the most important of these elements are the immune cells, which are considered to play a critical role throughout the course of breast carcinogenesis, beginning in normal breast tissue with immunosurveillance and continuing through primary and metastatic breast cancer. The ductal cellular layer in the normal breast contains a significant immune cell population consisting of CD8+and CD4+ T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, NK cells, and other immune cell subtypes.2–4 Together, these immune cells provide important innate and adaptive immunity to the epithelial layer for both protection against exogenous and endogenous agents, and elimination of transformed cells. An understanding of the immune cellular population in normal breast tissue may thus have important implications for breast cancer prevention, improved methods of risk assessment, and the regulation of breast carcinogenesis.

Progression through the carcinogenic pathway from normal breast tissue to breast cancer is accompanied by quantitative and qualitative changes in the nature and location of the immune cell population, including an increase in immune cell content in both the parenchymal and stromal compartments. The immune cell infiltration in breast cancer consists of multiple cellular subtypes, including CD3+ (CD4+ and CD8+) cells, B cells, monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells, and NK cells.4–6 The presence of multiple immune cell subtypes in both the parenchyma and stroma places these cells in close proximity to tumor cells and other cells in the microenvironment, and allows these cells to influence tumor growth in multiple ways, either directly through CD4+ and CD8+ cell-mediated cytotoxicity, or indirectly through immunosuppressive or immunostimulatory actions from secreted cytokines, growth factors and other agents. Their distribution and characteristics may also vary according to the subtype of breast cancer, their estrogen responsiveness, their mutational load, and the formation of tertiary lymphoid structures. Importantly, detailed analysis of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) has demonstrated prognostic properties for these cells,7–10 and harvesting and administration of TILs to patients has resulted in durable complete regression of solid tumors as well providing knowledge to allow development of cellular therapy with gene-modified T cell receptors for treatment of breast and other cancers.11 Together these findings indicate an important role for immune cells in the breast throughout breast carcinogenesis, and significant changes in these cells during the course of these events. To clarify these significant properties, we have conducted a review of the literature of the nature and characteristics of ductal immune cells in normal breast tissue, of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer, and the efforts to translate the latter findings into both valuable prognostic indicators and successful immunotherapeutic treatment options for breast cancer, including ongoing and innovative trials at our institution.

Materials and Methods

A literature search was conducted through PubMed and cross-references to identify publications describing the nature and distribution of immune cells in normal breast tissue and in breast cancer. Normal breast tissue may include tissue from women at normal risk (such as from reduction mammoplasty), as well as from the contralateral breast or from tissue adjacent to a breast cancer in women with a breast cancer. For studies of breast cancer, emphasis was placed on immune cells in the primary tumor.

Results and Discussion

Immune Cells in the Normal Breast

Breast Ductal Anatomy

The ductal anatomy and its relationship to the distribution of immune cells in the normal breast is illustrated in Fig 1. The principle unit in the breast ductal system is the acini which drains into an intralobular and then the extralobular duct; together these structures constitute the terminal ductal lobular unit (TDLU). The intralobular terminal ducts are lined by cuboidal epithelium, and the extralobular terminal duct and major ducts are lined by pseudostratified columnar epithelium or a double layer of cuboidal epithelium. The TDLU is considered to be the predominant site of the origin of breast cancer.12 The vast majority of breast cancers are carcinomas which arise in the epithelium and include in situ and invasive ductal and invasive lobular carcinoma. Gene expression studies have indicated that hormone-related pathways are highly enriched in the TDLU, including various hormone-related genes that are associated with breast carcinogenesis. It has been proposed that the imbalanced hormone-reactions may result in the early-onset of neoplastic transformation that occurs mostly in breast TDLUs.12 The breast ducts are surrounded by stroma which consists of extracellular matrix, fibroblasts, adipocytes, immune cells, microbiome, and blood vessels. The breast ducts and stroma together comprise the breast microenvironment.

Fig.1. The nature and distribution of immune cells in normal breast tissue.

A variety of immune cells are present in normal breast tissue, including both lymphocytes and myeloid-derived cells. Immune cells are located primarily within the ductal epithelium (intraepithelial) but may be present in the stroma as well (not depicted). The stromal extracellular matrix (ECM) also contains a variety of cell types and structures which may interact with immune cells and the epithelium (adapted from Degnim et al2).

Distribution of Immune Cells Within Normal Breast Tissue

Normal breast tissue contains immune cells of both myeloid (monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells) and lymphoid (T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes) lineage. Immune cells in normal breast tissue are predominantly localized to the lobules rather than the stroma and fat (Fig 1),2 are comprised of cells of both the innate and adaptive immune systems, and thus may potentially provide protection against bacterial and other pathogens as well as immune surveillance and elimination of epithelial cells with mutational changes. Immune cells identified in early studies were predominantly lymphocytes,13 including CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes,14, 15 and macrophages.13–15 Five recent studies have further characterized this intraepithelial immune cell population in normal breast tissue.2–4, 6, 16 Overall, immune CD45+ cells are prominent among the ductal epithelial cells. CD8+ T cells are the most common cells in all series, and in the study by Degnim et al,2 CD8+T cells and CD11c+ (dendritic) cells were present in virtually all lobules and among the most numerous across lobules, while CD68+ cells (macrophages/monocytes) were also numerous across lobules; CD4+ and CD20+ cells were less frequent. They also found both dendritic cells and CD8+ cells were consistently observed in intimate association with the epithelium of lobular acini and were primarily located at the basal aspect of the epithelium.2 The anatomical distribution of immune cells in normal breast tissue and their relationship to epithelial cells is depicted in Fig 1. The presence of the immune cells in the in TDLU places them at the predominant site of the origin of breast cancer - TDLU epithelial;12 this close proximity provides an important opportunity for the immune cells to influence the behavior of epithelial cells. Zumwalde et al,3 using flow cytometry of breast tissue organoids from reduction mammoplasty specimens, reported that CD8+ cells represented 75% of CD3+ cells; essentially all of the CD8α+ cells expressed CD8+β, indicating they were distinct from intestinal intra-epithelial cells which are CD8+αα.6 Ruffell et al6 examined normal breast tissue either adjacent to breast cancer or from prophylactic mastectomy specimens and found CD3+ (CD4+ and CD8+) cells were the most common, while myeloid-lineage cells including macrophages, dendritic cells and neutrophils were also prominent. The distribution of immune cell types thus appears to be quite consistent across multiple types of normal breast tissue.

Interestingly, in the study of normal breast organoids by Zumwalde et al,3 they identified an important subtype of CD3+ cells, γδ T cells. The T cell receptor (TCR) of these cells consists of γ and δ chains rather than the conventional α and β chains, and the receptor is considered to act as a pattern recognition receptor and a bridge between innate and adaptive immune responses.17 These cells possess cytotoxic activity, and serve to control the integrity of epithelium.18 The subtype Vγ2+ γδ T cells was found to be consistently present in preparations of mammary ductal epithelial organoids.3

Immunogenicity of Immune Cells in Normal Breast Tissue

An important question is the immunogenicity of the immune cells in normal breast tissue. It is noted that the immune cells in the breast ducts are in proximity to draining lymph nodes in the ipsilateral axilla and mediastinum, and thus all of the principle cellular and lymphatic components necessary for adaptive cellular immune response are present within the ductal system. In the study by Zumwalde et al3 further analysis of the CD8+ T cells indicated they were almost exclusively CD45RO+/CD27− cells, and thus were effector memory T cells (TEM). The presence of TEM in the intraepithelial lymphocyte population of the normal breast indicates these cells have been antigen-activated, as well as indicating the presence of a dynamic immune network between ductal epithelium and regional lymph nodes. Importantly, TEM may persist for considerable periods of time,19 and Hussein et al5 has shown that the CD3+ population of cells in normal breast tissue are granzyme + cells and thus have cytotoxic functions, suggesting an important protective role for these intraepithelial immune cells. There are several potential sources of antigens for activation of these CD8+ T cells, both exogenous (e.g. viral, bacterial) and endogenous (nuclear and cytosolic proteins, DNA, extracellular proteins). Neoantigens, for example, could arise through mutational changes in ductal epithelium from exposure to estrogens and other carcinogens.20 A recent review has demonstrated that normal breast tissue at normal risk for breast cancer (such as from a reduction mammoplasty) as well as normal breast tissue at increased risk for breast cancer (such as normal breast tissue adjacent to breast cancer) contain widespread genomic changes including loss of heterozygosity, small segmental deletions, DNA methylation, and telomere shortening.21, 22 This could provide an excellent source of neoantigens through associated frameshift or other mutational changes. In addition, the release of damage-associated- or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (DAMPS, PAMPS) from injured or dying epithelial or microbial cells may be recognized by macrophages (also present among ductal intraepithelial immune cells), eliciting release of cytokines and chemokines, chronic inflammation, and production of reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen intermediates which may then cause mutations in neighboring epithelial cells.23–25 As noted by Degnim et al,2 the consistent presence of CD8+ cells and dendritic cells, interspersed within the breast epithelium, strongly suggests a role for antigen presentation and immune effector function, as well as stress response and maintenance of epithelial integrity. In a subsequent study by Degnim et al,16 they compared the distribution of immune cells in the lobules of women with benign breast disease (BBD) to breast samples from women with no known breast abnormalities and found BBD lobules showed greater densities of CD8+ T cells, CD11c+ dendritic cells, CD20+ B cells, and CD68+ macrophages compared with the normal controls.16 The authors concluded that elevated infiltration of both innate and adaptive immune effectors in BBD tissues suggests an immunogenic microenvironment. Lastly, it has also been shown that many of the mutational changes observed in normal high risk breast tissue are also present in the adjacent breast cancer, thus providing a potentially comparable immunogenic environment for immune cells.26 Azizi et al, in a study of normal breast tissue from prophylactic mastectomy tissue, observed a large number of normal breast tissue resident immune cell states, including 13 myeloid and 19 T cell clusters that were not observed in circulation or in the secondary lymphoid tissue. The set of clusters found in normal breast tissue cells represented a subset of those observed in the breast cancers, supporting the widespread immunogenic environment of these tissues.

Intraepithelial Immune Cells and the Microenvironment

The immune cells within the intraepithelial layer are also surrounded by, and may be influenced by, major components of the microenvironment including the extracellular matrix and the interstitial matrix (Fig 1). The extracellular matrix (ECM) consists of the ductal and endothelial basement membranes, and the interstitial matrix is comprised of connective tissue and cellular components (fibroblast, adipocyte, endothelial, inflammatory).27 A dynamic interaction is thought to exist between the multiple components of the microenvironment which serves to maintain and promote the contribution of each component. The components of the microenvironment are also considered to play a significant role during breast carcinogenesis. With progression of the epithelial cells in the carcinogenic pathway, there is increasing influence of these components, including the ECM, fibroblasts, and adipocytes on transformed cells. As Ghajar and Bissell28 have pointed out, simple changes in ECM composition can alter diffusion and permeability through the ECM, and diffusion restrictions could foster tumorigenesis over short and long term-scales by restricting clearance of factors secreted by enveloped cells. Fibroblasts, a major component of the ECM, can be reprogrammed into cancer-associated-fibroblasts (CAFs) by cytokines and growth factors secreted by transformed epithelial cells.29 CAFs can be activated to promote tumor initiation, remodeling of the ECM, and modulation of immune cells.29 Adipocytes are also important components of the ECM and are in close proximity to epithelial cells, tumor and immune cells. Breast cancer cells induce production of endocrine and paracrine enzymes and bioactive lipids by adipocytes, which in turn drive increased growth and invasion of tumor cells.30 Leptin is also an important secretory product of adipocytes, which can stimulate production of several proinflammatory factors including IL-1, IL-6, and TNFα.31 Obesity is an important risk factor for breast cancer in postmenopausal women and may promote procarcinogenic processes in adipocytes. Several factors including Leptin, TNFα, IL-6, and resistin are secreted by normal adipocytes and which are increased with obesity and have procarcinogenic effects.32 These in turn can modify the immune system and promote tumor growth.33 Together these findings indicate a diverse population of cells within the ductal epithelial layer and microenvironment of normal breast tissue and which interact to play a major role in early breast carcinogenesis.

Estrogenic Effects on Normal Breast Immune Cells

Estrogen is the predominant hormone in women during both premenopausal and postmenopausal time periods. Estrogens play an important role throughout breast carcinogenesis, from influencing risk, to the development of contralateral breast cancer, to the progression of primary breast and metastatic breast cancer. These actions are achieved primarily through estrogenic actions on breast epithelial cells, however there is important evidence that immune cells contain estrogen receptors and are regulated by estrogens as well. This would provide an important opportunity for estrogens to influence immunosurveillance, as well as the development and progression of breast cancer. Estrogenic actions result from binding to cytoplasmic receptors ERα and ERβ and activation of genomic pathways, although estrogens may also activate growth factor receptor activity with signaling through nongenomic pathways by ligand-independent ERα signaling involving binding of E2 to a membrane-anchored receptor, the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER1), with subsequent activation of G proteins.34 Immune cells of both the innate (dendritic cells, macrophages, neutrophils) and adaptive (CD4+, CD8+, B cells) cell types, and in both normal tissue and in breast cancer, have been shown to possess estrogen receptors and to be responsive to estrogens.35–37 The response of immune cells to the estrogenic effects may include altered immune cell proliferation, secretion of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors.35, 38, 39

In breast cancer the distribution of immune cell types may vary according to tumor subtype as well as between stroma and tumor parenchyma (see below). The distribution of immune cells between stroma and parenchyma/ductal epithelium provides an opportunity for these cells, following estrogen stimulation, to influence multiple components of the microenvironment including other immune cells, epithelial cells, fibroblasts, adipose cells and endothelium. Ultimately, the response of immune cells will also be influenced by cell density, estrogen levels, extracellular matrix composition, blood supply, and the specific estrogen receptor which is stimulated.38, 40 While estrogens are probably the major steroid which influences cell behavior, it is recognized that these cells may also contain receptors for other steroids, including progesterone, glucocorticoids, and androgens,38 and respond and be influenced by these hormones as well. Together, the cellular responsiveness of immune cells to estrogens (and other hormones) further clarifies events regulating progression in carcinogenesis, as well as suggest an additional potentially important role for antiestrogen therapy.

Immune Cells in Ductal Carcinoma in situ

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is an important precursor lesion for invasive ductal carcinoma and accounts for 16% of all breast cancers annually in the United States.1 DCIS contains tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILS), and multiple studies have examined TIL in DCIS both according to cell density, according to the presence of aggressive features, and according to cell type. DCIS is characterized by an increase in the density and extent of immune cell infiltration compared to normal breast tissue.5, 41–43 The immune cell infiltrate in DCIS is also increased in more aggressive lesions, being greater in high grade tumors,41–46 ER negative tumors,41, 44 HER2+ or TNBC,43, 44, 46, 47 and also correlates with tumors with necrosis.5, 43, 44 High-grade DCIS has significantly higher percentages of FoxP3+ cells, CD68+ and CD68+PCNA+ macrophages, HLADR+ cells, CD4+ T cells, CD20+ B cells, and total tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) compared to nonhigh-grade DCIS.5, 48 Hussein and Hassan5 noted a marked increase in the density of mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrates, including CD20+, CD68+, CD3+ and granzyme B+ cytotoxic T cells from normal breast tissue to DCIS to invasive breast cancer. On average, ER− DCIS has been found to contain higher numbers of all tumor infiltrating lymphocyte subsets than ER+ DCIS, and ER+ DCIS was more likely to have to have a high CD8/FoxP3 ratio( >4) than ER− DCIS.41 Thompson et al41 observed that CD3+ T cells predominated across all DCIS subtypes at all ages, with slightly more CD4+ T cells than CD8+T cells on average. CD20+ B cells were the next most common tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, followed by FOXP3+ Treg. Others have observed B cells in DCIS and in invasive carcinoma which were typically found in perivascular locales clustering in aggregates with T cells, forming ectopic follicles,49, 50 and indicating that the presence of B cells in neoplastic mammary tissue is the result of chronic activation rather than nonspecific chemoattraction.49 There is evidence also that TILs in DCIS are immunosuppressive. PD-L1 is an immunosuppressive surface ligand on lymphocytes; Thompson et al41 demonstrated that 81% of DCIS lesions contained PD-L1+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. They considered this to suggest an active immune response within DCIS and supported tumor infiltrating lymphocyte expression of PD-L1 as a marker of downregulation of the body’s immune response within DCIS. FOXP3+ Treg cells are another important immunosuppressive cell which are increased in DCIS,41, 44, 48, 51, 52 and are associated with high nuclear grade, comedo-type necrosis, hormone receptor (HR) negativity, high Ki-67 proliferation index, and p53 overexpression.44 Kim et al44 found the high infiltration of FOXP3+ TIL and the presence of PD-L1+ immune cells were associated with tumor recurrence in patients with pure DCIS. Pure DCIS associated with higher numbers of B lymphocytes has also been shown to be associated with a shorter recurrence-free interval (P = 0.04).53 Bates et al52 observed high numbers of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells identified in patients with DCIS at increased risk of relapse (P = 0.04). CD8+ HLADR+ T cells, CD8+ HLADR− T cells, and CD115+ cell populations have also shown to be associated with risk of recurrence.48 Together these findings indicate a prominent presence of TIL and which may play an important immunosuppressive role in DCIS.

Immune Cells in Invasive Carcinoma of the Breast

The immune cell content of breast tissue increases progressively from normal breast tissue to breast cancer.4–6, 54, 55 This is best illustrated by studies comparing the immune cell distribution in breast cancer and related normal breast tissue. In a study of mastectomy specimens utilizing IHC and flow cytometry, Ruffell et al6 observed that breast cancer tissues contained infiltrates dominated by CD8+ and CD4+ lymphocytes, with minor populations of NK cells and B lymphocytes, whereas in the normal breast tissue myeloid-lineage cells including macrophages, mast cells, and neutrophils were more evident. A similar immune profile was observed in breast tissues obtained in prophylactic mastectomy tissue. Activated T lymphocytes also predominated in tumor tissue, with both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells displaying increased expression of activation markers CD69 and HLA-DR. They concluded these findings indicated a shift within tumors toward a Th2-type response in breast cancer characterized by the increased presence of B cells and CD4+ T cells, in comparison with normal breast tissue.6 At the transcriptional level, Azizi et al4 compared by singe cell sequencing the immune cell distribution in breast cancer with that of normal adjacent breast tissue. They found a significant increase in the diversity of cell states, reflected in an increase in variance of gene expression, among T cells, monocytes, and NK cells in tumor compared with normal tissue. This suggested that the increased heterogeneity of cell states and marked phenotypic expansions found within the tumor were likely due to more diverse local microenvironments within the tumor.4 Two small studies utilizing high-throughput sequencing of the T cell receptor beta chain to characterize diversity of the T cell infiltrate have been performed. Beausang et al56 demonstrated that there are unique compartments of enriched clonotypes in tumor and tumor-adjacent normal breast tissue, as well as identifying sequences shared among patients and unlikely to be involved in specific tumor recognition. Park et al57 studied tumors pre- and post-neoadjuvant therapy and demonstrated a clonal expansion and decrease in diversity in those patients with pathologic complete response to therapy.

The complexity of the composition of immune cells in breast cancer reflects a “cross-talk” between components of the innate immune response as it regulates the tumor microenvironment and the polarity of the adaptive immune response within that tumor.49 Lymphocytes of the myeloid lineage, i.e. tumor-associated macrophages, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and dendritic cells, can create immunostimulatory or immunosuppressive milieus that affect the fate of T cells capable of homing to the tumor. In turn, macrophage polarization can be driven to M1 or M2 phenotypes by the cytokines expressed by cytotoxic or regulatory T cells.49, 58

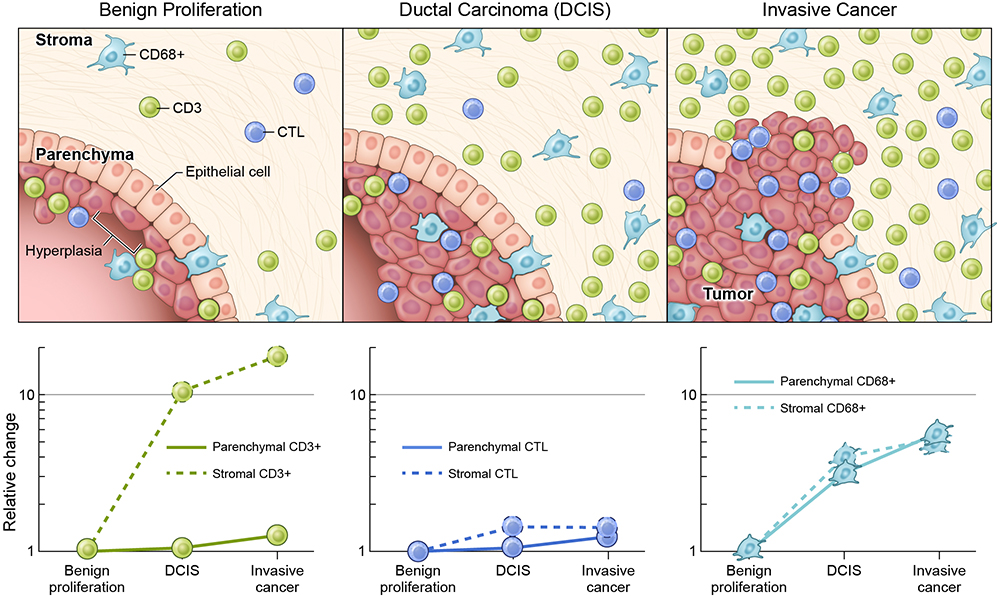

Within breast cancer the distribution of immune cells may also differ between the tumor parenchyma and stroma. In a study of breast cancer mastectomy specimens, immune cells were delineated in the tumors and surrounding stroma by immunohistochemical staining to identify CD3 (T cells), CD20 (B cells), CD68 (macrophages) and granzyme B (cytotoxic subset of CD3+ cells).5 The breast samples ranged the spectrum of breast disease: normal, benign proliferative disease (usual ductal hyperplasia [UDH]), DCIS, and invasive ductal carcinoma. While there was a progressive increase in all cell types in both the parenchyma and stroma moving from normal mammary tissue to ductal carcinoma, the most striking difference from benign proliferative disease to DCIS to invasive cancer was the influx of CD3+ cells in the stroma of the latter two tissue types: average 4.2 cells/mm2 v. 46.6 cells/mm2 v. 77.0 cells/mm2, respectively (Figure 2). Interestingly, increases in the cytotoxic subset (granzyme B) were restricted to immune cells in the parenchyma: 16.3 vs 0.7 cells/mm2 in the parenchyma vs stroma of invasive cancer.5 Solinas et al,59 in their review, similarly found that the incidence of stromal TIL ranged from 15% to 25%, whereas intratumoral TIL ranged from 5% - 10%. As will be discussed below, stromal TILs also have important prognostic value.

Fig 2. Immune cells in breast proliferative disease and breast cancer.

Immune Cells, including CD68+(Macrophages/Monocytes),CD3+ (CD4+, CD8+), and Cytotoxic Lymphocytes (CTL) are Present in Breast Proliferative Disease and Increase in the Parenchyma and Stroma With Progression to Breast Cancer. Relative Increases for Each Cell Type, With Benign Proliferation as a Baseline, are Shown on a Logarithmic Scale in the Graphs Below the Figure. (Adapted from Data from within Hussein and Hassan5)

Immune Cell Distribution According to Breast Cancer Subtype

The distribution of TIL varies quantitively and qualitatively according to subtype in breast cancer. This has been demonstrated in several series. Stanton et al,54 in a review of 13,914 patients, found a median of 20% of patients with triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) demonstrated lymphocyte-predominant breast cancer (LPBC; ≥ 50%−60% lymphocytic infiltrate) at the time of diagnosis compared with 16% of HER2+ tumors and 6% of HR+ cancers. A median of 60% of TNBC samples had infiltrating CD8+ T-cells in contrast to only 43% of HR+ tumors. TNBC tumors were also more likely to have FOXP3+ infiltrates than the HR+ subtype. Their findings indicated that hormone receptor–positive disease may be the least immunogenic of the common breast cancer subtypes. Liu et al,60 in another study, reported a high density infiltration of Treg and FOXP3P+Tumor, but not CD8+Tumor, correlated significantly with HER2 overexpression. Increased infiltration of Tregs and CTLs was significantly more common in those tumors with unfavorable histologic features, including high histologic grade and negative ER and PR status. They proposed that further studies to explore the functional status and action modes of CTLs and Tregs in different tissue locations and in different breast cancer subtypes will lead to a better understanding of the nature of breast carcinoma immunity. Denkert et al61 observed the percentage of tumors with high TILs was higher in TNBC [30%] and HER2-positive breast cancer [19%] than in luminal–HER2-negative tumors [13%] p<0.0001. Their data supported the hypothesis that breast cancer is immunogenic and might be targetable by immune-modulating therapies. Mohamed et al62 reported HER2/neu positive breast cancer had a significantly higher CD8+ content (26.1%) as compared to luminal A (13.5%), luminal B (17.0), or TNBC (14.5%) This, however, did not apply to CD3+ or CD45RO+ type cells, and there was no significant correlation between CD45RO+ TILs and clinico-pathological parameters. Their study was conducted in the Sudan, and their finding that a higher CD8+ content was observed in HER2/neu positive breast cancer is in agreement with the other studies, and suggests that the biological factors regulating TIL distribution according to subtype in North Africa may be similar to those in the United States.

Mutational Load of Breast Cancer Cells

The finding that immune cell types in breast cancer varied according to breast cancer subtype suggested the mutational load of breast cancer subtypes may also vary. When this was studied it was found there are also striking differences in the mutational load of breast cancer between subtypes. The genomic characteristics of each subtype has recently been analyzed and presented in detail in an analysis of cancer-adjacent breast tissue from The Cancer Genome Atlas Network.22 The findings for different subtypes can be summarized as follows: the overall mutation rate was lowest in luminal A subtype and highest in the basal like and Her2 enriched (HER2E) subtypes. The luminal A subtype harbored the most significantly mutated genes, with the most frequent being PIK3CA (45%), followed by MAP3K1, GATA3, TP53, CDH1 and MAP2K4. Twelve per cent of luminal A tumors contained likely inactivating mutations in MAP3K1 and MAP2K4. TP53 and PIK3CA mutations were the most common in Luminal B cancer (29% each); this contrasted with basal-like tumors where TP53 mutations occurred in 80% but PIK3CA mutations were absent or rare. Ten percent of sporadic breast cancer may have a strong germline contribution. Luminal tumors were mostly diploid whereas luminal B tumors were mostly aneuploid. Regarding Her2+ tumors, there are at least two types of clinically defined HER2 tumors, luminal-mRNA-subtype/HER2+tumours, and HER2E-mRNA subtype (HER2 enriched). A comparison identified 302 differentially expressed genes. The HER2E mRNA subtype typically showed high aneuploidy, the highest somatic mutation rate, and DNA amplification of other potential therapeutic targets including FGFRs, EGFR, CDK4 and cyclin D1. TP53 mutations were significantly enriched in HER2E or ER-negative tumors whereas GATA3 mutations were only observed in luminal subtypes or ER+ tumors. The basal-like subtype included triple negative breast cancer (TNBC; 75%) as well as other mRNA subtypes (25%), and showed basal-like tumors with a high frequency of TP53 mutations (80%). PIK3CA was mutated in 9% of cases; however, inferred PI(3)K pathway activity, whether from gene, protein, or high PI(3)K/AKT pathway activities was highest in basal-like cancers. Expression features showed high expression of genes associated with cell proliferation. While chromosome 8q24 is amplified across all subtypes, high MYC activation seems to be a basal-like characteristic. Other major genomic changes include ATM mutations (3%), BRCA1 (30%) and BRCA2 (6%) inactivation, RB1 loss (20%) and cyclin E1 amplification (9%). Together, these findings indicate a significant mutational burden across breast cancer subtypes. This may have important clinical, therapeutic, and biological implications. A high mutational burden would be associated with increased genomic instability and neoantigen development, increased cell injury and death, and development of chronic inflammation. At the same time altered secretion of secretory products could influence the activity, distribution, and interaction of associated immune and other cell types.

Nature of Immune Cells in Tertiary Lymph Structures in Breast Cancer

Tertiary lymph structures (TLS)/organs (TLO) are ectopic lymphoid organs which develop at sites of chronic inflammation including autoimmune diseases, infection, and tumors. TLS have a defined structure, are comprised of multiple cell types including both innate (dendritic, macrophages and neutrophils) and adaptive (B cells and T cells) as well as plasma cells and high endothelial venules.63, 64 TLS are believed to be the site of immune response activation against tumor by recruiting and activating TIL.65 The TLS may be within the tumor or in a peritumoral location. TLS are generally associated with tumors with a more aggressive phenotype such as high grade tumors, triple negative breast cancer, and HER2+ tumors.62, 65, 66 Liu et al65 reported TLS were associated with higher tumor grade, apocrine phenotype, necrosis, extensive in situ component, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), high TIL, hormone receptor negativity, HER2 positivity, and c-kit expression. A favorable impact of TLS density on overall survival and disease- free survival of patients has been observed.62, 63, 66–71 An Important component of TLS are high endothelial venules (HEV). These are specialized post–capillary venules found in lymphoid tissues that support high levels of lymphocyte extravasation from the blood.72 High densities of tumor HEVs correlated with increased naive, central memory and activated effector memory T-cell infiltration and upregulation of genes related to T-helper 1 adaptive immunity and T-cell cytotoxicity.67 In the study by Martinet et al67 high densities of tumor HEVs independently conferred a lower risk of relapse and significantly correlated this activity with longer metastasis-free, disease-free, and overall survival rates. Together, the presence and characteristics of TLS have important clinical implications: their presence in poor-prognostic tumors may be important both for selection of therapy and entry into clinical trials. The identification of an organized immune cell collection with effector memory cells in and adjacent to breast cancer and capable of antitumor activity may encourage efforts to promote its development and expansion in these tumors. The presence, in TLS, of HEVs which can enhance movement of lymphocytes into these tumors also encourages efforts to identify agents which can promote the activity of these vessels.

Immune Cells as a Prognostic Biomarker

With renewed interest in immune cells, investigators have interrogated large prospectively collected patient samples associated with seminal clinical trials to evaluate the role of immune cells as prognostic markers. The first of these studies was reported by Denkert et al10 after analysis of the GeparDuo and GeparTrio trial cohorts. Pre-treatment core biopsies of tumor and stroma were analyzed for lymphocytic infiltrate evaluated by routine hematoxylin and eosin staining. Two categories of immune infiltrate were defined: iTu-Ly (intratumoral lymphocytes) in direct contact with tumor cells or within tumor cell nests and str-Ly (stromal lymphocytes) without direct contact with tumor cells. Lymphocyte predominant breast cancer (LPBC) was defined as tumors with >60% of either iTu-Ly or str-Ly and represented 11% of the study population. LPBC demonstrated an increased incidence of pathologic complete response (pCR 41.7%, 10 of 24) when compared to those tumors with no lymphocytic infiltrate (2.8%, 1 of 36) or focal infiltrate (10.8%, 17 of 158). This was also demonstrated in gene expression data of the same cohort.10In an analysis of the BIG 02–98 multi-institutional randomized phase III trial, increasing lymphocyte infiltration was associated with improved prognosis in the subgroup of node-positive patients with triple negative breast cancer (TNBC). LPBC represented only 10.6% of the TNBC cohort using a threshold of 50%, but prognosis improved linearly with each 10% increase in lymphocyte infiltration.8

Tumor samples from patients in the ECOG 1199 and 2197 trials have been analyzed for the presence of intraepithelial (iTIL) or stromal (sTIL) lymphocytes.9 Overall the median iTIL score was 0%, and LPBC was again a minority of cases (4.4%), although over 80% of cancers had a sTIL score >10. Higher sTIL scores were associated with better prognosis; for every 10% increase in sTILs, a 14% reduction of risk of recurrence or death was noted (P = .02), and an 18% reduction of risk of distant recurrence (P = .04), and 19% reduction of risk of death. However, in Liu et al,60 the effects of CD8+Tumor infiltration, and the ratio of CD8+Tumor/FOXP3P+Tumor on OS and PFS, were not significant, whereas patients with high FOXP3+Tumor had a significantly shorter OS (P = 0.007) and PFS (P = 0.003) both in the ER-positive and ER-negative groups. Interestingly, recent studies have indicated that the spatial location and organization of CD8+ TILs within the tumor may be important in relation to relapse-free survival (RFS).73 Egelston et al73 reported that the presence of islands of infiltrating CD8+ T cells was more significantly associated with RFS than CD8+ T cell infiltration into either tumor stroma or total tumor. The integrin CD103, a marker for tissue resident memory T cells (TRM) appeared to mediate localization into cancer islands within tumors. The TRM subset has been implicated in cancer surveillance of melanoma and lung cancer.74, 75 Savas et al76 utilized single-cell RNA sequencing techniques to derive a CD8+ TRM signature from primary TNBC tumors; when applied to a bulk RNA data, the signature was associated with improved patient survival.

A review of 15 studies of TIL classification also identified differences in lymphocyte infiltration across tumor subtypes.54 LPBC was more frequently identified in TNBC (20%) and HER2+ (16%) specimens than in hormone receptor positive/HER2− tumors (6%). Efforts have been made to unify the classification of TILs within breast cancer specimens, with a focus on stromal lymphocytes as the most reproducible and significant prognostic indicator of likelihood of response.7 In an analysis by Denkert et al61 of pooled data from the German Breast Cancer Group, classification of tumors by degree of stromal lymphocyte invasion allowed one to predict response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in all molecular subtypes, but differences in survival outcomes may suggest a different biology of the immunological infiltrate in hormone receptor positive tumors. While pathological complete response (pCR) was attained in 28% of luminal Her2− tumors with high TILs (>60%) as compared to 6% and 11% in low (≤10%) and intermediate TILs, the presence of TILs was associated with shorter overall survival in that subtype. TNBC with high TILs demonstrated a higher pCR rate (50% high vs 31% intermediate and low) and was associated with longer disease free and overall survival. The gains were more modest in Her2+ tumors with a 48% pCR rate in high TILs specimens vs 39% in intermediate and 32% in low samples, but still associated with longer disease free survival.61 Together, these findings support a prognostic role of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer. The prognostic significance may correlate inversely with tumor hormone receptor status, suggesting there may also be a prominent hormonal influence on these lymphocytes in hormone receptor positive tumors.

Lastly, the effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on immune cell distribution has also been examined. In the study of Ruffell et al6 their findings suggested that neoadjuvant chemotherapy further altered the complexity of the immune microenvironment of the residual tumors. They found residual tumors treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy contained increased percentages of infiltrating myeloid cells, accompanied by an increased CD8/CD4T-cell ratio and higher numbers of granzyme B-expressing cells, compared with tumors not treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The effect of chemotherapy has also been examined by García-Martínez et al,77 who evaluated tumors using IHC to define CD3+ cells, subsets of CD4+ and CD8+ cells, and the presence of B cells and monocytes before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy.77 They observed a decrease in the number of CD3+ cells after chemotherapy and a decrease in the CD4:CD8 ratio. They concluded that an IHC-based profile of immune cell subpopulations in breast cancer is able to identify a group of tumors highly sensitive to neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Immune-based Therapies for Breast Cancer

The majority of the studies of lymphocytes in breast cancer has focused on characterizing the nature of the lymphocyte infiltrate, with some gene expression data that may hint at the functional role of these cells in an anti-cancer response. Chemokines thought to be responsible for lymphocyte migration and gene expression signatures associated with Type I effector responses have been shown to correlate with pCR.78, 79 Programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) and one of its ligands (PD-L1) have also been correlated with higher pCR rate and improved prognosis in breast cancer.80 These molecules are part of the immune checkpoint pathway that limits T cell response. PD-L1 gene expression of immune cells in breast cancer has been shown to be positively associated with CD8+ and CD4+ memory activated T cells, but not with CD4+ memory resting or T-regulatory cells or other immune cell subpopulations.81 In other histologies, expression of PD-L1 may correlate with response to checkpoint inhibition, but there are significant challenges to its use as a predictive biomarker, highlighted by the KEYNOTE-86 trial of pembrolizumab in patients with TNBC in which PD-L1 status was not the strongest discriminator between responders and non-responders.82 The overall response rate in that trial was 18.5%. Similarly modest results were seen in an ER+ population in KEYNOTE-28 with an overall response rate of 12%.83, 84 Checkpoint inhibitors have been combined with chemotherapy demonstrating improvement in median overall survival, more pronounced in those patients with PD-L1+ tumors (Impassion130 trial),84 and an increase in the pathologic complete response rate in women with triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-522).85 A comprehensive review of current and proposed combination strategies identified thirteen ongoing randomized phase III clinical trials investigating the strategy in patients with breast cancer.86

Given the presence of an immune infiltrate in stages as early as DCIS, strategies to boost the immune response to potential tumor antigens by vaccination have been explored in prevention, adjuvant, neoadjuvant and metastatic settings.87 Additional efforts explore the use of tumor ablative strategies (i.e. cryoablation, radiofrequency ablation, stereotactic radiation) for potential release of tumor-associated antigens in conjunction with checkpoint inhibitor monoclonal antibodies to increase response rates.88, 89 A recent review highlighted the ways in which the breast cancer immune-oncology field is building on the information about TIL phenotype to branch into different promising avenues of research.90 Few groups have studied the phenotype and function of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes cultured from freshly resected breast cancer. In the Surgery Branch of the National Cancer Institute, NIH, TILs derived from fragments of metastatic breast cancer and cultured in interleukin-2 were predominantly CD4+, in contrast to our experience with metastatic melanoma-derived TIL which are predominantly CD8+ cells.91, 92 Whole exome sequencing of the resected tumor identified candidate neoepitopes for further study, and TIL cultures were capable of identifying neoantigens processed by autologous antigen-presenting cells in vitro, in both Class I and Class II restricted fashion.11, 93 In a study of primary breast tumors, another group used an agonistic antibody against 4–1BB/CD137 during the initial TIL cultures and were able to generate more robust CD8+ populations. In two of these patient-derived cultures, the expanded CD8+ TILs were capable of mutation-specific recognition of Class I predicted neoepitopes.94 Tumor-specific TIL could be utilized to identify tumor neoantigens that could then be utilized in patient-specific vaccine strategies or to create cell-based treatments with autologous TIL or TIL-derived T-cell receptor gene-engineered products. We recently demonstrated proof of principle in a single case report of complete regression of refractory metastatic breast cancer after adoptive cell transfer with interleukin-2 and pembrolizumab.11

In conclusion, immune cells are identified in breast tissue throughout carcinogenesis, beginning in normal breast tissue in women at normal risk for breast cancer and continuing through breast cancer primary tumors and breast cancer metastases. The immune cells in normal breast tissue may play an important role in immunosurveillance and clarify our understanding of the prevention (and development) of early events in breast carcinogenesis. Our understanding of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes is increasing dramatically. These cells have prognostic value for breast cancer outcomes and serve in adoptive transfer and other capacities to treat disseminated breast cancer. This knowledge is allowing us to recognize and to modify T cells in multiple ways, including selection of tumor neoantigen-specific T cells, to the engineering of T cell receptors (TCR) to recognize specific tumor associated neoantigens and to insert these TCRs into lymphocytes (including PBL), for the development of vaccines which recognize tumor-specific antigens in breast cancer metastases. Together, these findings allow immunology and immunotherapy to serve as the major fourth modality for the management of patients with cancer, alongside surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy. This should significantly improve our ability to prevent and treat breast cancer and many other malignancies.

Highlights.

Immune cells are an important component of normal breast tissue and serve in innate and adaptive immunity.

Immune cells in normal breast tissue may play an important role in the immunosurveillance and prevention of breast cancer.

Immune cell infiltrates are increased in breast cancer and have an important prognostic and therapeutic role.

Selection and genetic engineering of breast cancer T cell lymphocytes provides multiple opportunities for innovative treatment approaches for breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

Funding. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Abbreviations

- TNBC

triple negative breast cancer

- TCR

T cell receptor

- PBL

peripheral blood lymphocytes

- TIL

tumor infiltrating lymphocytes

- pCR

pathologic complete response

- LPBC

lymphocyte predominant breast cancer

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- CAF

cancer-associated-fibroblast

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- RFS

relapse-free survival

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts and Figures 2017–2018.

- 2.Degnim AC, Brahmbhatt RD, Radisky DC, et al. Immune cell quantitation in normal breast tissue lobules with and without lobulitis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;144:539–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zumwalde NA, Haag JD, Sharma D, et al. Analysis of Immune Cells from Human Mammary Ductal Epithelial Organoids Reveals Vdelta2+ T Cells That Efficiently Target Breast Carcinoma Cells in the Presence of Bisphosphonate. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2016;9:305–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azizi E, Carr AJ, Plitas G, et al. Single-Cell Map of Diverse Immune Phenotypes in the Breast Tumor Microenvironment. Cell. 2018;174:1293–1308.e1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hussein MR, Hassan HI. Analysis of the mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate in the normal breast, benign proliferative breast disease, in situ and infiltrating ductal breast carcinomas: preliminary observations. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:972–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruffell B, Au A, Rugo HS, Esserman LJ, Hwang ES, Coussens LM. Leukocyte composition of human breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2796–2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salgado R, Denkert C, Demaria S, et al. The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer: recommendations by an International TILs Working Group 2014. Ann Oncol 2015;26:259–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loi S, Sirtaine N, Piette F, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in a phase III randomized adjuvant breast cancer trial in node-positive breast cancer comparing the addition of docetaxel to doxorubicin with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy: BIG 02–98. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:860–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams S, Gray RJ, Demaria S, et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancers from two phase III randomized adjuvant breast cancer trials: ECOG 2197 and ECOG 1199. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2959–2966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denkert C, Loibl S, Noske A, et al. Tumor-associated lymphocytes as an independent predictor of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zacharakis N, Chinnasamy H, Black M, et al. Immune recognition of somatic mutations leading to complete durable regression in metastatic breast cancer. Nat Med. 2018;24:724–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang J, Yu H, Zhang L, et al. Overexpressed genes associated with hormones in terminal ductal lobular units identified by global transcriptome analysis: An insight into the anatomic origin of breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 2016;35:1689–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferguson DJ. Intraepithelial lymphocytes and macrophages in the normal breast. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1985;407:369–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giorno R Mononuclear cells in malignant and benign human breast tissue. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1983;107:415–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lwin KY, Zuccarini O, Sloane JP, Beverley PC. An immunohistological study of leukocyte localization in benign and malignant breast tissue. Int J Cancer. 1985;36:433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Degnim AC, Hoskin TL, Arshad M, et al. Alterations in the Immune Cell Composition in Premalignant Breast Tissue that Precede Breast Cancer Development. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:3945–3952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holtmeier W, Kabelitz D. gammadelta T cells link innate and adaptive immune responses. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2005;86:151–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kabelitz D, Wesch D. Features and functions of gamma delta T lymphocytes: focus on chemokines and their receptors. Crit Rev Immunol. 2003;23:339–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999;401:708–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy D, Liehr JG. Estrogen, DNA damage and mutations. Mutat. Res. 1999;424:107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danforth DN Jr., Genomic Changes in Normal Breast Tissue in Women at Normal Risk or at High Risk for Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer (Auckl). 2016;10:109–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Network TCGA. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490(7418):61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karin M, Lawrence T, Nizet V. Innate immunity gone awry: linking microbial infections to chronic inflammation and cancer. Cell. 2006;124:823–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chow MT, Moller A, Smyth MJ. Inflammation and immune surveillance in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012;22:23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Troester MA, Hoadley KA, D’Arcy M, et al. DNA defects, epigenetics, and gene expression in cancer-adjacent breast: a study from The Cancer Genome Atlas. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2016;2:16007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frantz C, Stewart KM, Weaver VM. The extracellular matrix at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:4195–4200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghajar CM, Bissell MJ. Extracellular matrix control of mammary gland morphogenesis and tumorigenesis: insights from imaging. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130:1105–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohlund D, Elyada E, Tuveson D. Fibroblast heterogeneity in the cancer wound. J Exp Med. 2014;211:1503–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoy AJ, Balaban S, Saunders DN. Adipocyte-Tumor Cell Metabolic Crosstalk in Breast Cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2017;23:381–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delort L, Rossary A, Farges MC, Vasson MP, Caldefie-Chezet F. Leptin, adipocytes and breast cancer: Focus on inflammation and anti-tumor immunity. Life Sci. 2015;140:37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cabia B, Andrade S, Carreira MC, Casanueva FF, Crujeiras AB. A role for novel adipose tissue-secreted factors in obesity-related carcinogenesis. Obes Rev. 2016;17:361–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madeddu C, Gramignano G, Floris C, Murenu G, Sollai G, Maccio A. Role of inflammation and oxidative stress in post-menopausal oestrogen-dependent breast cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2014;18:2519–2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Segovia-Mendoza M, Morales-Montor J. Immune Tumor Microenvironment in Breast Cancer and the Participation of Estrogen and Its Receptors in Cancer Physiopathology. Front Immunol. 2019;10:348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kovats S Estrogen receptors regulate innate immune cells and signaling pathways. Cell Immunol. 2015;294:63–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faas M, de Vos P, Melgert B. Sex hormones and immunoregulation. http://www.brainimmune.com/sex-hormones-and-immunoregulation 2011.

- 37.Khan D, Ansar Ahmed S. The Immune System Is a Natural Target for Estrogen Action: Opposing Effects of Estrogen in Two Prototypical Autoimmune Diseases. Front Immunol 2015;6:635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bereshchenko O, Bruscoli S, Riccardi C. Glucocorticoids, Sex Hormones, and Immunity. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bouman A, Heineman MJ, Faas MM. Sex hormones and the immune response in humans. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11:411–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Navarro FC, Herrnreiter C, Nowak L, Watkins SK. Estrogen Regulation of T-Cell Function and Its Impact on the Tumor Microenvironment. Gender and the Genome. 2018;2:81–91. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson E, Taube JM, Elwood H, et al. The immune microenvironment of breast ductal carcinoma in situ. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:249–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tower H, Ruppert M, Britt K. The Immune Microenvironment of Breast Cancer Progression. Cancers. 2019;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hendry S, Pang JB, Byrne DJ, et al. Relationship of the Breast Ductal Carcinoma In Situ Immune Microenvironment with Clinicopathological and Genetic Features. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:5210–5217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim M, Chung YR, Kim HJ, Woo JW, Ahn S, Park SY. Immune microenvironment in ductal carcinoma in situ: a comparison with invasive carcinoma of the breast. Breast Cancer Res. 2020;22:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen XY, Yeong J, Thike AA, Bay BH, Tan PH. Prognostic role of immune infiltrates in breast ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;177:17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gil Del Alcazar CR, Huh SJ, Ekram MB, et al. Immune Escape in Breast Cancer During In Situ to Invasive Carcinoma Transition. Cancer discovery. 2017;7:1098–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pruneri G, Lazzeroni M, Bagnardi V, et al. The prevalence and clinical relevance of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2017;28:321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Campbell MJ, Baehner F, O’Meara T, et al. Characterizing the immune microenvironment in high-risk ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;161:17–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DeNardo DG, Coussens LM. Inflammation and breast cancer. Balancing immune response: crosstalk between adaptive and innate immune cells during breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coronella-Wood JA, Hersh EM. Naturally occurring B-cell responses to breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2003;52:715–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martin F, Ladoire S, Mignot G, Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F. Human FOXP3 and cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:4121–4129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bates GJ, Fox SB, Han C, et al. Quantification of regulatory T cells enables the identification of high-risk breast cancer patients and those at risk of late relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5373–5380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miligy I, Mohan P, Gaber A, et al. Prognostic significance of tumour infiltrating B lymphocytes in breast ductal carcinoma in situ. Histopathology. 2017;71:258–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stanton SE, Adams S, Disis ML. Variation in the Incidence and Magnitude of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Breast Cancer Subtypes: A Systematic Review. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1354–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ben-Hur H, Cohen O, Schneider D, et al. The role of lymphocytes and macrophages in human breast tumorigenesis: an immunohistochemical and morphometric study. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:1231–1238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beausang JF, Wheeler AJ, Chan NH, et al. T cell receptor sequencing of early-stage breast cancer tumors identifies altered clonal structure of the T cell repertoire. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E10409–e10417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park JH, Jang M, Tarhan YE, et al. Clonal expansion of antitumor T cells in breast cancer correlates with response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Int J Oncol. 2016;49:471–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sica A, Allavena P, Mantovani A. Cancer related inflammation: the macrophage connection. Cancer Lett. 2008;267:204–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Solinas C, Carbognin L, De Silva P, Criscitiello C, Lambertini M. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer according to tumor subtype: Current state of the art. Breast. 2017;35:142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu F, Lang R, Zhao J, et al. CD8(+) cytotoxic T cell and FOXP3(+) regulatory T cell infiltration in relation to breast cancer survival and molecular subtypes. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:645–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Denkert C, von Minckwitz G, Darb-Esfahani S, et al. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis in different subtypes of breast cancer: a pooled analysis of 3771 patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mohamed M, Sarwath H, Salih N, et al. CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes strongly correlate with molecular subtype and clinico-pathological characteristics in breast cancer patients from Sudan. Translational Medicine Communications. 2016;1:4. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sautes-Fridman C, Petitprez F, Calderaro J, Fridman WH. Tertiary lymphoid structures in the era of cancer immunotherapy. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2019;19:307–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Engelhard VH, Rodriguez AB, Mauldin IS, Woods AN, Peske JD, Slingluff CL Jr., Immune Cell Infiltration and Tertiary Lymphoid Structures as Determinants of Antitumor Immunity. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950). 2018;200:432–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu X, Tsang JYS, Hlaing T, et al. Distinct Tertiary Lymphoid Structure Associations and Their Prognostic Relevance in HER2 Positive and Negative Breast Cancers. Oncologist. 2017;22:1316–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee HJ, Park IA, Song IH, et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures: prognostic significance and relationship with tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancer. Journal of clinical pathology. 2016;69:422–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Martinet L, Garrido I, Filleron T, et al. Human solid tumors contain high endothelial venules: association with T- and B-lymphocyte infiltration and favorable prognosis in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5678–5687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Martinet L, Filleron T, Le Guellec S, Rochaix P, Garrido I, Girard JP. High endothelial venule blood vessels for tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are associated with lymphotoxin beta-producing dendritic cells in human breast cancer. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950). 2013;191:2001–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sofopoulos M, Fortis SP, Vaxevanis CK, et al. The prognostic significance of peritumoral tertiary lymphoid structures in breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68:1733–1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Song IH, Heo SH, Bang WS, et al. Predictive Value of Tertiary Lymphoid Structures Assessed by High Endothelial Venule Counts in the Neoadjuvant Setting of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49:399–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin L, Hu X, Zhang H, Hu H. Tertiary Lymphoid Organs in Cancer Immunology: Mechanisms and the New Strategy for Immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Girard JP, Springer TA. High endothelial venules (HEVs): specialized endothelium for lymphocyte migration. Immunol Today. 1995;16:449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Egelston CA, Avalos C, Tu TY, et al. Resident memory CD8+ T cells within cancer islands mediate survival in breast cancer patients. JCI Insight. 2019;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Malik BT, Byrne KT, Vella JL, et al. Resident memory T cells in the skin mediate durable immunity to melanoma. Sci Immunol. 2017;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ganesan AP, Clarke J, Wood O, et al. Tissue-resident memory features are linked to the magnitude of cytotoxic T cell responses in human lung cancer. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:940–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Savas P, Virassamy B, Ye C, et al. Single-cell profiling of breast cancer T cells reveals a tissue-resident memory subset associated with improved prognosis. Nat Med. 2018;24:986–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Garcia-Martinez E, Gil GL, Benito AC, et al. Tumor-infiltrating immune cell profiles and their change after neoadjuvant chemotherapy predict response and prognosis of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schmidt M, Weyer-Elberich V, Hengstler JG, et al. Prognostic impact of CD4-positive T cell subsets in early breast cancer: a study based on the FinHer trial patient population. Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Park IA, Hwang SH, Song IH, et al. Expression of the MHC class II in triple-negative breast cancer is associated with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and interferon signaling. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pelekanou V, Barlow WE, Nahleh ZA, et al. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and PD-L1 Expression in Pre- and Posttreatment Breast Cancers in the SWOG S0800 Phase II Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Trial. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17:1324–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zerdes I, Sifakis EG, Matikas A, et al. Programmed death-ligand 1 gene expression is a prognostic marker in early breast cancer and provides additional prognostic value to 21-gene and 70-gene signatures in estrogen receptor-positive disease. Mol Oncol 2020;14:951–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nanda R, Chow LQ, Dees EC, et al. Pembrolizumab in Patients With Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Phase Ib KEYNOTE-012 Study. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2460–2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rugo HS, Delord JP, Im SA, et al. Safety and Antitumor Activity of Pembrolizumab in Patients with Estrogen Receptor-Positive/Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Advanced Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:2804–2811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schmid P, Adams S, Rugo HS, et al. Atezolizumab and Nab-Paclitaxel in Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2108–2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schmid P, Cortes J, Pusztai L, et al. Pembrolizumab for Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2020;382:810–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Adams S, Gatti-Mays ME, Kalinsky K, et al. Current Landscape of Immunotherapy in Breast Cancer: A Review. JAMA oncology. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Benedetti R, Dell’Aversana C, Giorgio C, Astorri R, Altucci L. Breast Cancer Vaccines: New Insights. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017;8:270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hickey RM, Kulik LM, Nimeiri H, et al. Immuno-oncology and Its Opportunities for Interventional Radiologists: Immune Checkpoint Inhibition and Potential Synergies with Interventional Oncology Procedures. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28:1487–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hwang WL, Pike LRG, Royce TJ, Mahal BA, Loeffler JS. Safety of combining radiotherapy with immune-checkpoint inhibition. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:477–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gatti-Mays ME, Balko JM, Gameiro SR, et al. If we build it they will come: targeting the immune response to breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2019;5:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Goff SL, Zacharakis N, Assadipour Y, et al. Recognition of autologous neoantigens by tumor infiltrating lymphocytes derived from breast cancer metastases San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium San Antonio, TX2016. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Goff SL, Dudley ME, Citrin DE, et al. Randomized, Prospective Evaluation Comparing Intensity of Lymphodepletion Before Adoptive Transfer of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes for Patients With Metastatic Melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2389–2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Assadipour Y, Zacharakis N, Crystal JS, et al. Characterization of an Immunogenic Mutation in a Patient with Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:4347–4353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Harao M, Forget MA, Roszik J, et al. 4–1BB-Enhanced Expansion of CD8(+) TIL from Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Unveils Mutation-Specific CD8(+) T Cells. Cancer Immunol Res 2017;5:439–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]