Abstract

Background

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are at increased risk of exposure to severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). Personal protective equipment (PPE) is mandated for HCWs. However, the physiological effects on the HCWs while working in the protective gear remains unexplored. This study aimed to assess the physiological effects of the prolonged use of PPE on HCWs.

Materials and methods

Seventy-five HCWs, aged 18–50 years were enrolled in this prospective, observational, cohort study. The physiological variables [heart rate, oxygen saturation, and perfusion index (PI)] were recorded at the start of duty, 4 hours after wearing N95 filtering facepiece respirator (FFR), pre-donning, and post-doffing. The rating of perceived exertion (RPE) score and modified Borg scale for dyspnea was evaluated. The physiological variables were represented as the mean ± standard deviation. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to show any difference in RPE and modified Borg scale for dyspnea. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

There is a statistically significant difference in the physiological parameters post-doffing compared with baseline: Heart rate (p < 0.001); oxygen saturation (p < 0.001); PI (p < 0.001). RPE score showed increased discomfort with continuous use of N95 FFR. However, exertion increased only marginally. The major adverse effects noted with PPE use were fogging, headache, tiredness, difficulty in breathing, and mask soakage, with a resultant mean duration of donning to be 3.1 hours.

Conclusion

The use of PPE can result in considerable changes in the physiological variables of healthy HCWs. The side effects may lead to excessive exhaustion and increased tiredness after prolonged shifts in the intensive care unit (ICU) while wearing PPE.

How to cite this article

Choudhury A, Singh M, Khurana DK, Mustafi SM, Ganapathy U, Kumar A, et al. Physiological Effects of N95 FFP and PPE in Healthcare Workers in COVID Intensive Care Unit: A Prospective Cohort Study. Indian J Crit Care Med 2020;24(12):1169–1173.

Keywords: COVID-19, Healthcare workers, Heart rate, Intensive care unit, N95 respirators, Oxygen saturation, Perfusion index, Personal protective equipment, Physiological, Stress

Introduction

The pandemic caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) has put unprecedented stress on global healthcare services. The frontline healthcare workers (HCWs) are at increased risk of exposure to infected patients. Therefore, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Centers for Disease Control have issued guidelines for droplet barrier precautions and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) to mitigate the risk.1,2 The N95 respirator forms a critical component of the PPE kit along with gloves, gown, and eyewear. However, the stress and discomfort encountered while wearing the PPE puts an additional burden on the HCWs and encumbers their working.3

The tolerability of the PPE and its physiological effects on HCWs remains unexplored.4,5 Hence, we undertook this study to evaluate the physiological effects and tolerability of PPE kit along with N95 respirator on HCWs while they were engaged in their daily routine activities of intensive care unit (ICU).

Materials and Methods

This prospective, observational study was approved by the institutional Ethics Committee (IEC/VMMC/SJH/Project/2020-07/CC-11) and registered with CTRI (CTRI/2020/027112). Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The study was conducted in August 2020 at VMMC and Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi. The participants were enrolled from the healthy HCWs posted in COVID ICU during this period which included doctors, nurses, and technicians, aged between 18 years and 50 years. Those with cardiac or respiratory comorbidities and pregnancy were excluded. A total of 75 HCWs were enrolled in the study.

All the HCWs were instructed to have breakfast and adequate water intake before participation in the study. Avoidance of any strenuous activity was advised. Observations from each participant were taken only once. The ambient temperature of ICU varied from 25 to 28°C and the relative humidity from 60 to 70%.

The observations were made only during the daytime shift. The baseline observations were taken at the beginning of the morning shift which included the pulse rate (HR), oxygen saturation (SpO2), and the perfusion index (PI). The parameters were obtained using a pulse oximeter probe based on Masimo technology (MX 550-Phillips). For all measurements, the finger probe was applied to the second finger of the right hand. Perceived exertion was rated using a modified CR10 scale by Foster et al.;6 a scale of 0 to 10 was used in which 0 was at rest and 10 was maximal hard work perceived. Modified Borg scale for dyspnea7 was used to assess the comfort level of the participants where 0 denoted no dyspnea to a maximal score of 10.

All the HCWs wore N95 filtering facepiece respirator (FFR) (valveless) after performing a proper seal test and were divided into two groups, A and B according to the workload: light work in the nursing area just outside ICU and heavy work inside ICU. The light work outside ICU included paperwork, labeling sample bottles, making drugs, answering the telephone, maintaining patient records, and facilitating the work of coworker inside ICU, whereas heavy work inside ICU after wearing additional PPE along with FFR included patient care, delivering drugs, bedding, counseling patients, helping them with their needs, and monitoring vitals. This was done to decrease exposure time to patients, thus leading to a maximum contact time of not >4 hours for each HCW. However, they were instructed to doff off before their scheduled work time in the event of any discomfort or if there was any breach in PPE.

The group A HCWs were involved in light work outside ICU, wearing just the N95 FFR, whereas group B HCWs were the first to don PPE to deliver healthcare inside COVID ICU. Observations were recorded only for the group A HCWs on a particular day who would interchange in the next shift so as not to repeat observations from the same HCW twice. The observations for the defined parameters were recorded at the beginning of the shift as a baseline (T1), at the end of 4 hours of light work (T2), after 15 minutes of rest and before donning (T3), and lastly, post-doffing after working in ICU (T4). The period, the HCW was able to work inside the ICU was also recorded along with the adverse effects noted by them.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS statistical software version 24.0 was used for statistical analysis. Demographic data were represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The physiological variables were also represented as mean ± SD and to bring out the difference between these variables at various time points (baseline, post 4 hours of N95, pre-donning, and post-doffing) t-test was carried out. The data from the rating of perceived exertion (RPE) scores and modified Borg scale for dyspnea were represented as median (IQR) and Wilcoxon signed-rank test was carried out to show any difference. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The adverse effects noted due to PPE and N95 FFR were represented as percentages.

Results

A total of 75 HCWs participated in the study—53 were doctors, 21 nurses, and 1 ICU technician. Forty of these were females and 35 males with a mean age of 29.05 ± 2.12 years.

Physiological Parameters (Table 1)

Table 1.

Comparison of physiological parameters at various time intervals

| Variables | Heart rate (beats/minute) | Oxygen saturation (%) | Perfusion index | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean difference (CI) | p value | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (CI) | p value | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (CI) | p value | |

| Baseline (T1) vs 4 hours after N95 (T2) | 99.8 ± 14.86 | −1.41 (−3.26, 0.433) | 0.131 | 97.87 ± 1.17 | 0.13 (−0.11, 0.37) | 0.272 | 5.0 ± 2.41 | 0.38 (0.24, 0.52) | <0.001 |

| 101.21 ± 15.78 | 97.73 ± 1.12 | 4.62 ± 2.21 | |||||||

| Baseline (T1) vs PPE off (doffing) (T4) | 99.8 ± 14.86 | −9.03 (−11.24, −6.81) | <0.001 | 97.87± 1.17 | 0.85 (0.62, 1.08) | <0.001 | 5.0 ± 2.41 | 1.37 (0.9, 1.84) | <0.001 |

| 108.83 ± 14.33 | 97.01± 1.12 | 3.63 ± 1.94 | |||||||

| PPE on (donning) (T3) vs PPE off (doffing) (T4) | 99.97 ± 15.38 | −8.85 (−13.15, −4.55) | <0.001 | 97.71± 1.09 | 0.69 (0.42, 0.97) | <0.001 | 4.76 ± 2.36 | 1.12 (0.59, 1.66) | <0.001 |

| 108.83 ± 14.33 | 97.01 ± 1.12 | 3.63 ± 1.94 | |||||||

Bold terms represent statistical significance. PPE, personal protective equipment

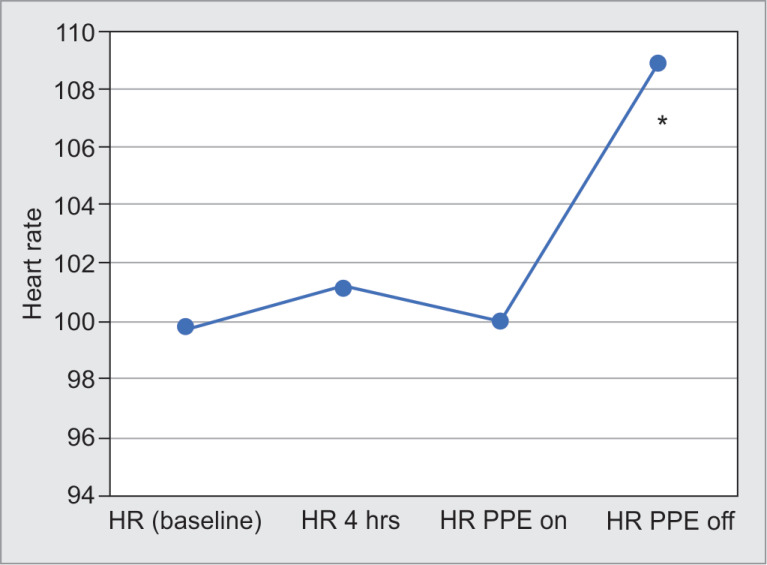

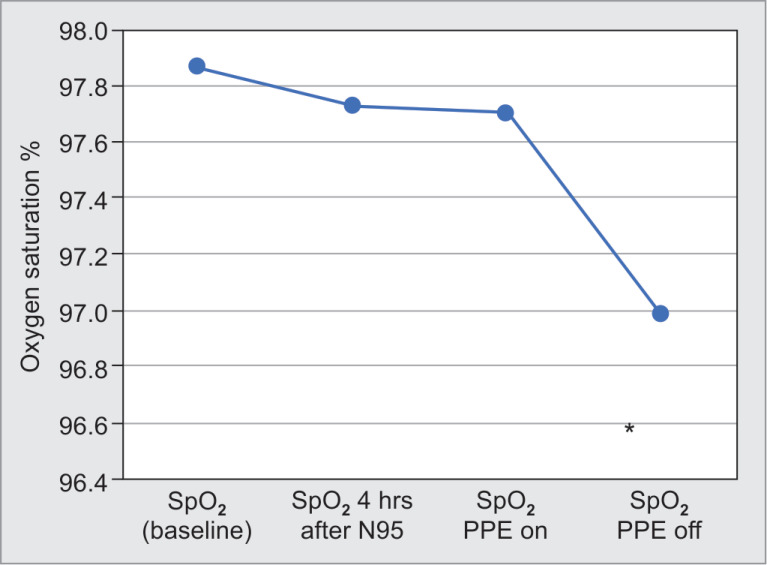

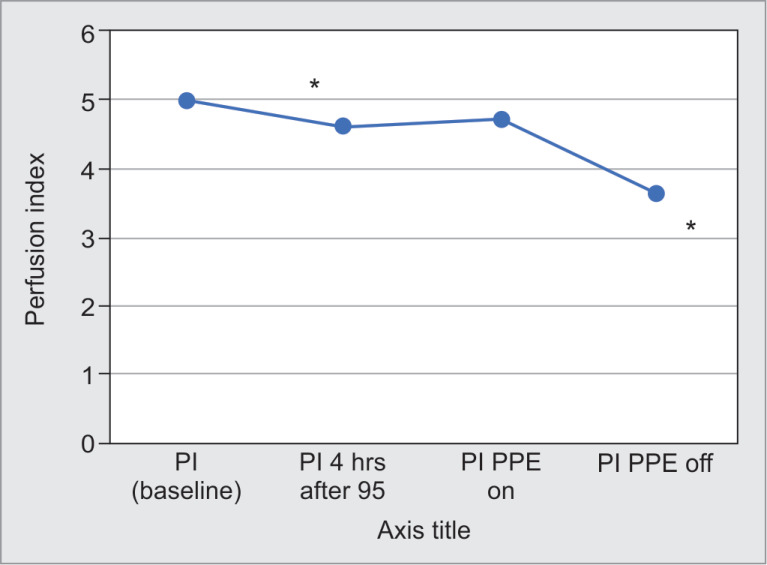

The physiological parameters were significantly altered after 8 hours of duty when compared with the baseline (Figs 1 to 3).

Fig. 1.

Heart rate (HR) variations. *p < 0.001(when compared with baseline)

Fig. 3.

SpO2 variations. *p < 0.001(when compared with baseline)

Heart rate (HR) characteristic showed a significant increase in the mean heart rate post-doffing when compared with baseline heart rate, at 4 hours after N95 FFR application, and at pre-donning (95% CI: −11.237, −6.817; p < 0.001; 95% CI: −9.994, −5.233; p < 0.001; 95% CI: −13.152, −4.554; p < 0.001, respectively). However, no statistical significance was noted between heart rate after 4 hours of N95 FFR application to that of baseline (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Perfusion index (PI) variations. *p < 0.001(when compared with baseline)

Comparison of PI showed a decrease in PI post-doffing when compared with baseline PI and after doffing PPE (95% CI: 0.8996, 1.8418; p < 0.001) suggesting a significant decrease in blood flow to fingers. Similar findings were noted at 4 hours after N95 application (95% CI: 0.5328, 1.4419; p < 0.001) and pre-donning when compared with post-doffing PI (95% CI: 0.5856, 1.6597; p < 0.001). A statistically significant difference between PI at baseline and that after 4 hours of N95 was demonstrated (95% CI: 0.2442, 0.5225; p < 0.01) (Fig. 3).

When oxygen saturation was analyzed, a statistical significant difference was observed between baseline saturation, at 4 hours post N95 and pre-donning when compared with that after doffing [95% CI: 0.624, 1.082; p < 0.001; (95% CI: 0.448, 0.992; p < 0.001; 95% CI: 0.415, 0.971; p < 0.001)] (Table 1).

The RPE scores showed that exertion 4 hours after N95 FFR application, pre-donning, as well as post-doffing, were significant when compared with that of baseline (Z = −8.660, p < 0.001 and Z = −8.324, p < 0.001, respectively).

The modified Borg scale for dyspnea showed statistically significant results when post-donning and doffing were compared with the baseline (Z = −2.499, p = 0.012 and Z = −7.61, p < 0.001, respectively). Statistical significance was also noted between post-donning and post-doffing (Z = −7.440, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

RPE and modified Borg scoring for dyspnea

| Scores | Mean ± SD | Z | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| RPE scores | |||

| 4 hours of N95 vs baseline | 2 ± 0 | −8.660 | <0.001 |

| 0 | |||

| PPE off (doffing) vs baseline | 3 ± 0.293 | −8.324 | <0.001 |

| 0 | |||

| PPE off (doffing) vs PPE on (donning) | 3 ± 0.293 | −8.246 | <0.001 |

| 2 ± 0.0 | |||

| Modified Borg scale for dyspnea | |||

| 4 hours of N9 vs baseline | 0.200 ± 0.358 | −0.463 | 0.643 |

| 0.167 ± 0.287 | |||

| PPE off (doffing) vs baseline | 3.107 ± 0.708 | −7.610 | <0.001 |

| 0.167 ± 0.287 | |||

| PPE off (doffing) vs PPE on (donning) | 3.107 ± 0.708 | −7.440 | <0.001 |

| 0.340 ± 0.594 | |||

Bold terms represent statistical significance. PPE, personal protective equipment; RPE, rating of perceived exertion

All HCWs complained of fogging, whereas 90% had a headache and 60% had breathing difficulty (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adverse effects reported by the participants

| Adverse effects | Participants (n = 75) |

|---|---|

| Fogging | 75 (100%) |

| Headache | 68 (90.67%) |

| Tiredness | 53 (70.67%) |

| Difficulty in breathing | 45 (60%) |

| Mask soakage | 18 (24%) |

| PPE breach | 3 (4%) |

| Palpitation | 2 (2.67%) |

| Bronchospasm | 1 (1.33%) |

Discussion

The novel coronavirus pandemic mandates the use of PPE with respiratory protective equipment to reduce exposure in HCWs. However, this protection is not without certain adverse physiological consequences.5 Our study evaluated the physiological changes associated with the use of PPE and N95 respirator among frontline HCWs during this COVID pandemic.

A significant increase in heart rate from the baseline was noted in our study with the prolonged use of N95 respirator and PPE (post-doffing). These findings may signify the physiological responses to hypoxia and hypercarbia caused by the dead space of the N95 FFR which might have led to the accumulation of carbon dioxide.3,5,8 The reduced availability of O2 and an increasing amount of CO2 can result in increased heart rate and blood pressure exponentially, even at low workloads. This physiological alteration may increase aortic and left ventricular pressures, leading to an upsurge of cardiac overload and coronary demand.9 Moreover, the increased respiratory load against the valveless breathing mask leads to increased respiratory muscle load and pulmonary artery pressure, in turn, adding to the cardiac overload. However, the increase in heart rate after 4 hours (light work) is not significant which is corroborated by the findings of Kao et al. who noted a mild decrease in heart rate with FFR during 4 hours of sedentary activity.10 Therefore, FFR-associated increase in heart rate after prolonged periods of donning PPE and N95 correlates to breathing resistance, work level, physical fitness, FFR-associated anxiety, and increased retention of CO2.11,12

A study on the impact of the surgical mask on SpO2 in surgeons during surgery revealed that a significant decrease in SpO2 occurs only in procedures longer than 60 minutes.13 The change in oxygen saturation from the baseline to 4 hours of N95 usage and post-donning was noted to be <1%. These findings were similar to those seen during qualitative respirator-fit testing done for N95 FFR among controls and subjects.14 The decrease in SpO2 from baseline to post-doffing can be explained by the increase in work rendered by HCW after donning PPE. A similar finding was noted by Spurling et al. wherein they found poor saturation of hemoglobin secondary to the increased partial pressure of CO2 at higher exercise intensity.15

Moreover, the effect of microenvironments like the high temperatures and humidity levels prevailing in our work environment might have led to a high microenvironment temperature and humidity inside the N95 FFR as well as the PPE.3,16 This results in a higher resistance offered while breathing through the FFRs and consequently drop-in oxygen saturation seen post-doffing, which though statistically significant, does not seem to be clinically significant.

The PI is a reliable indicator of peripheral perfusion which is expressed as a percentage ranging from 0.02 to 20%. Fall in PI was more in the post-doffing period when compared with 4 hours after N95 from the baseline. The most likely cause is the redistribution of body fluids, as HCWs were involved in heavy work post-donning. So, muscle cells consumed more energy and oxygen leading to a decrease in nutrients and an increase in molecules, such as, carbon dioxide resulting in vasodilation.17 In addition, the vasodilatation secondary to the extreme heat due to prolonged donning of PPE can lead to profuse sweating causing dehydration and redistribution of body fluids.18

Comfort is an important issue concerning N95 FFR tolerance. The level of self-perceived discomfort among the participants increased over time with the use of the N95 respirator and PPE. While this finding hardly seems unexpected, we used a modified Borg dyspnea scale for assessing it. The post-doffing scores were much higher suggesting that PPE and FFRs imposed an extra burden on the HCWs while working for a prolonged duration in the ICU making their working environment more stressful. Moreover, with prolonged working hours, the level of exertion required to perform the work increased significantly after 4 hours of wearing N95 as well as post-doffing leading to increased fatigability and discomfort. Meyer et al. in his work on 30 subjects also suggested that the preferable duration of wearing respiratory equipment is 1 hour in an atmosphere of 18°C is a more conducive working environment.19

The mean duration of heavy work with protective gear (PPE with N95) in our study was 3.1 hours. During this work duration, fogging was the most common adverse effect noted by the HCWs, followed by headache, tiredness, breathing difficulty, and N95 soakage with sweat as the im causes of discomfort. If the mask is not well fitted for the HCW, it may result in a leak from the nasal bridge causing fogging of the protective eye gear leading to poor visibility, thus hampering work.20,21 It has also been anecdotally suggested that extended wear of PPE and protective eye gear might lead to entrapment of exhaled moisture in the filters of FFR, theoretically resulting in increased breathing resistance. The face mask forms a closed circuit for the inspired and expired air. Rebreathing of the expired air increases arterial CO2 concentrations thereby increasing the intensity of acidity in the acidic environment.22 Thus, individuals working with a mask would have physiological effects similar to a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) person exercising, such as, discomfort, fatigue, dizziness, headache, shortness of breath, muscular weakness, and drowsiness.23

The majority of our HCWs experienced a headache. Jyong et al.24 in the HAPPE study reported an increase of 81% in the incidence of headache in frontline HCW due to wearing PPE for >4 hours per day (OR 3.91, 95% CI: 1.35, 11.31; p = 0.012). A plausible explanation could be elevated PCO2 levels which might lead to vasodilatation and headache in HCW.25 However, studies on FFR with exhalation valves showed that the presence of the valve did not significantly ameliorate the FFR's PCO2 impact or the elevated PCO2 level.5

Though PPE is crucial for protecting the HCWs in a physically demanding environment of increased risk of infection with COVID-19, its negative impact cannot be overlooked. Healthcare workers’ health is crucial for effective control of this pandemic. So, institutional policies should be framed to ensure scheduled frequent breaks during long shifts, adequate hydration, and nutrition, safe removal of PPE, and reporting of symptoms related to their PPE. Research on designing more comfortable protective gear should be encouraged along with better engineering modifications to work environments, such as, negative pressure environments with proper monitoring of work area temperature and humidity.

However, our study is not without limitations. The tough work environment without adequate air conditioning and ventilation added to the discomfort. A study in a more controlled environment with appropriate temperature and humidity controls should be devised. Our study is a single-center study, so the findings cannot be generalized due to different working conditions at different hospitals. Larger sample size may be considered for future studies. Healthcare workers caring for patients with contagious life-threatening illnesses during a pandemic may be willing to tolerate respirators for periods longer than that observed in our study. It is important to note that infection control procedures and appropriate processes for disinfecting, changing, and maintaining respirators would need to be considered if HCWs were to use respirators for an extended duration. As this was an observational study so the partial pressures of carbon dioxide, oxygen, and lactate levels were not measured which could have provided more conclusive evidence for the physiological changes that occur.

Conclusion

Healthcare workers underwent significant physiological changes while using PPE and FFR over prolonged shifts with a notable tachycardia. These hemodynamic perturbations coupled with the additional stress of wearing FFRs and PPE for a long duration and the toll, the pandemic takes on health caregivers, adds to their discomfort with a resultant reduction in their work efficiency.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Deepak Shukla, Consultant ICMR, for his contribution in statistical analysis of data. Also we would like to extend our gratitude to the healthcare workers (resident doctors, nurses technicians and orderlies) in our institute who have participated in the study as well as those who did not for their continuous efforts to care for critically ill COVID patients. A real tribute to them for their tireless efforts in controlling the pandemic in our country. We thank all the participants for their cooperation to help carry out this project.

Highlights

The health and safety of healthcare workers are of utmost importance in this COVID pandemic; however, the baseline data regarding the physiological effects which occur in them after prolonged use of PPE remains unexplored.

We studied the changes in the physiological parameters (an increased HR, decreased SpO2, and PI) and the increased discomfort along with the exertion resulting from wearing PPE during prolonged working hours. These changes coupled with the anxiety and fears related to this pandemic and direct exposure to increased viral loads make them more vulnerable to infection in case of a breach in PPE or decreased immunity.

These changes highlight the need for institutional policies for better working conditions for the HCWs, shorter working shifts or appropriate breaks during the shifts to maintain hydration and rest, and research on better quality PPE as these HCWs are frontline workers on whom the medical care rests in this pandemic.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.A World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2020. Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and considerations during severe shortages: interim guidance, 6 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seto WH, Tsang D, Yung RW, Ching TY, Ng TK, Ho M, et al. Advisors of expert SARS group of hospital authority. Effectiveness of precautions against droplets and contact in prevention of nosocomial transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Lancet. 2003;361(9368):1519–1520. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13168-6. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Tokura H, Guo YP, Wong AS, Wong T, Chung J, et al. Effects of wearing N95 and surgical facemasks on heart rate, thermal stress and subjective sensations. Int Archi Occupat Environ Health. 2005;78(6):501–509. doi: 10.1007/s00420-004-0584-4. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radonovich LJ, Jr,, Cheng J, Shenal BV, Hodgson M, Bender BS. Respirator tolerance in health care workers. JAMA. 2009;301(1):36–38. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.894. (Reprinted) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberge RJ, Coca A, Williams WJ, Powell JB, Palmiero AJ. Physiological impact of the N95 filtering facepiece respirator on healthcare workers. Respir Care. 2010;55(5):569–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster C, Florhaug JA, Franklin J, Gottschall L, Hrovatin LA, Parker S, et al. A new approach to monitoring exercise training. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2001;15(1):109–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson RC, Jones PW. A comparison of the visual analogue scale and modified Borg scale for the measurement of dyspnoea during exercise. Clin Sci. 1989;76(3):277–282. doi: 10.1042/cs0760277. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tong PS, Kale AS, Ng K, Loke AP, Choolani MA, Lim CL, et al. Respiratory consequences of N95-type mask usage in pregnant healthcare workers—a controlled clinical study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2015;4(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s13756-015-0086-z. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melnikov VN, Divert VE, Komlyagina TG, Consedine NS, Krivoschekov SG. Baseline values of cardiovascular and respiratory parameters predict response to acute hypoxia in young healthy men. Physiol Res. 2017;66(3):467–479. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.933328. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kao TW, Huang KC, Huang YL, Tsai TJ, Hsieh BS, Wu MS. The physiological impact of wearing an N95 FFR during hemodialysis as a precaution against SARS in patients with end-stage renal disease. J Formos Med Assoc. 2004;103(8):624–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones JG. The physiological cost of wearing a disposable respirator. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1991;52(6):219–225. doi: 10.1080/15298669191364631. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaye J, Buchanan F, Kendrick A, Johnson P, Lowry C, Bailey J, et al. Acute carbon dioxide exposure in healthy adults: evaluation of a novel means of investigating a stress response. J Neuroendocri. 2004;16(3):256–264. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-8194.2004.01158.x. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beder A, Büyükkoçak U, Sabuncuoğlu H, Keskil ZA, Keskil S. Preliminary report on surgical mask induced deoxygenation during major surgery. Neurocirugia (Astur) 2008;19(2):121–126. doi: 10.1016/s1130-1473(08)70235-5. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laferty EA, McKay RT. Physiologic effects and measurement of carbon dioxide and oxygen levels during qualitative respirator fit testing. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chas.8b13507 J Chem Health Safe. 2006;13:22–28. DOI: [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spurling KJ, Moonsie IK, Perks JL. Hypercapnic respiratory acidosis during an in-flight oxygen assessment. AMHP. 2016;87(2):144–147. doi: 10.3357/AMHP.4345.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nielsen R, Berglund LG, Gwosdow AR, Dubois AB. Thermal sensation of the body as influenced by the thermal microclimate in a face mask. Ergonomics. 1987;30(12):1689–1703. doi: 10.1080/00140138708966058. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joyner MJ, Casey DP. Regulation of increased blood flow (hyperemia) to muscles during exercise: a hierarchy of competing physiological needs. Physiolog Rev. 2015;95(2):549–601. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2013. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vegfors M, Lindberg L, Lennmarken C. The influence of changes in blood flow on the accuracy of pulse oximetry in humans. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1992;36(4):346–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1992.tb03479.x. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer JP, Hery M, Herrault J, Hubert G, Francois D, Hecht G, et al. Field study of subjective assessment of negative pressure half-masks. Influe Work Condit Comfort Effici. Appl Ergonom. 1997;28(5-6):331–338. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(97)00007-0. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu W-H, Liu W-C. Assessment of physiological loads and subjective discomforts for wearing N95 facemask. (Abstract). Healthcare Systems Ergonomics and Patient Safety International Conference, Strasbourg, FR. Jun 25–27, 2008, [[Accessed 15 Apr 2009].]. http://www.heps2008.org/abstract/data/POSTER/Hsu.pdf http://www.heps2008.org/abstract/data/POSTER/Hsu.pdf Available from URL:

- 21.Belkin NL. A century after their introduction, are surgical masks necessary? Assoc. Oper. Room Nurs. J. 1996;64:602–607. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)63628-4. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobson TA, Kler JS, Hernke MT, Braun RK, Meyer KC, Funk WE. Direct human health risks of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide. Nat Sustain. 2019;2(8):691–701. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith CL, Whitelaw JL, Davies B. Carbon dioxide rebreathing in respiratory protective devices: influence of speech and work rate in full-face masks. Ergonomics. 2013;56(5):781–790. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2013.777128. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jyong J, Bharatendu C, Goh Y, Zy Tang J, Wx Sooi K, Lin Tan Y, et al. Headaches associated with personal protective equipment-a cross-sectional study amongst frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19 (HAPPE study). Headache. 2020;60:864–877. doi: 10.1111/head.13811. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu W. Should, and how can, exercise be done during a coronavirus outbreak? an interview with Dr. Jeffrey A. woods. J Sport Health Sci. 2020;9(2):105. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.01.005. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]