Highlights

-

•

Gigantomastia is a rare condition characterized by excessive diffuse enlargement of both breasts.

-

•

The etiology remains poorly understood with most common being pubertal and gestational with idiopathic gigantomastia being rare.

-

•

PASH (Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia) is a histopathological diagnosis and association with Idiopathic gigantomastia is still rarer.

Keywords: Idiopathic gigantomasia, Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH), Diffuse breast enlargement, Endogenous hormone stimulation, Reduction mammoplasty

Abstract

Background

Gigantomastia is a rare condition characterized by excessive diffuse enlargement of both breasts and can be physically and psychosocially disabling for the patient. Despite an extensive search, the etiology remains poorly understood with most common being pubertal and gestational gigantomastia, with incidence of Idiopathic gigantomastia associated with bilateral PASH being extremely rare.

Methods

A 37 year old lady with bilateral gigantomastia and severe back pain with a normal radiological, hormonal and histopathological evaluation underwent reduction mammoplasty with objective of weight and volume reduction of the breasts along with aesthetic enhancement.

Results

The excised specimen weighed 3.5 and 5 kg respectively in left and right breast with uneventful post operative period and symptomatic relief to the patient. The histopathology was suggestive of macromastia with pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia like areas with focally PR positive status on IHC.

Conclusion

Most commonly etiological factor for gigantomastia is endogenous hormone stimulation. While idiopathic gigantomastia is rare those associated with PASH are still rarer with around 13 cases reported in the literature till date. PASH is a beingn mesenchymal proliferative lesion of the breast, mostly found in premenopausal women and rarely manifests clinically. Reduction mammoplasty can make a significant improvement in life of such young patients with explained risk of probability of recurrence. Among the various techniques available inverted T scar pattern with superiomedical pedicle are preferred as the learning curve is shorter, have greater versatility, and is reproducible with consistent results.

1. Introduction

Gigantomastia is a rare condition characterized by excessive diffuse enlargement of both breasts and can be physically and psychosocially disabling for the patient [1]. In some texts gigantomastia (Greek, gigantikos: giant) is defined as excessive breast tissue more than 2.5 kg [2,3]. Patients experience physical and psychological discomfort, such as pain, muscular discomfort, skin ulceration [4] due to overstretching, loss of nipple sensation, and social stigma. Despite an extensive search the etiology remains poorly understood [5], with most common being pubertal and gestational gigantomastia.

Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH) of breast is a rare benign proliferation of non specialized fibrous mammary stroma [6] first described in 1986 by Vuitch et al. [7] on histopathology. It is usually asymptomatic and found incidentally on breast biopsies of premenopausal women. However, bilateral diffuse PASH that causes rapid breast enlargement without forming discrete nodular masses is extremely rare.

The etiology of PASH has not been well established. It is known to express progesterone and estrogen receptors, indicating that it is hormone-sensitive [8]. Gigantomastia due to PASH is very rare. Fewer than 10 cases have been reported in the literature [9] and only one recurrence has been reported [10]. Thus case was diagnosed as Idiopathic gigantomastia which was later confirmed as PASH after histopathological examination of the resected specimen. This work has been reported in line with the surgical case report (SCARE) guidelines criteria [11].

2. Case report

A 37 year lady, homemaker, presented with a history of painless progressive and massive enlargement of breasts for 8 years with severe back pain, impairment of daily functioning and psychological embarrassment with no family history of similar complaint. She had menarche at the age of 11 years and menstrual cycles were regular with normal flow. Her obstetrics history was P3A0. All pregnancies were full term with normal vaginal delivery. Her first pregnancy was 18 years ago, and last 10 years ago with history of breastfeeding for 2 years in the first two pregnancies and 1 year in the last one. She had no history of any drug intake, alcohol and smoking. Her BMI was 23.8 kg/m2. Breast examination revealed no palpable lump or axillary lymph nodes with normal overlying skin (Picture 1, Picture 2, Picture 3, Picture 4).

Picture 1.

Bilateral gigantomastia.

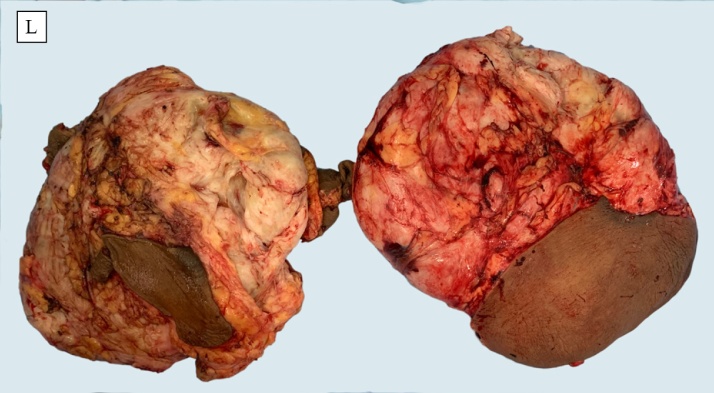

Picture 2.

Resected bilateral breast specimens.

Picture 3.

Pre-operative image of the patient.

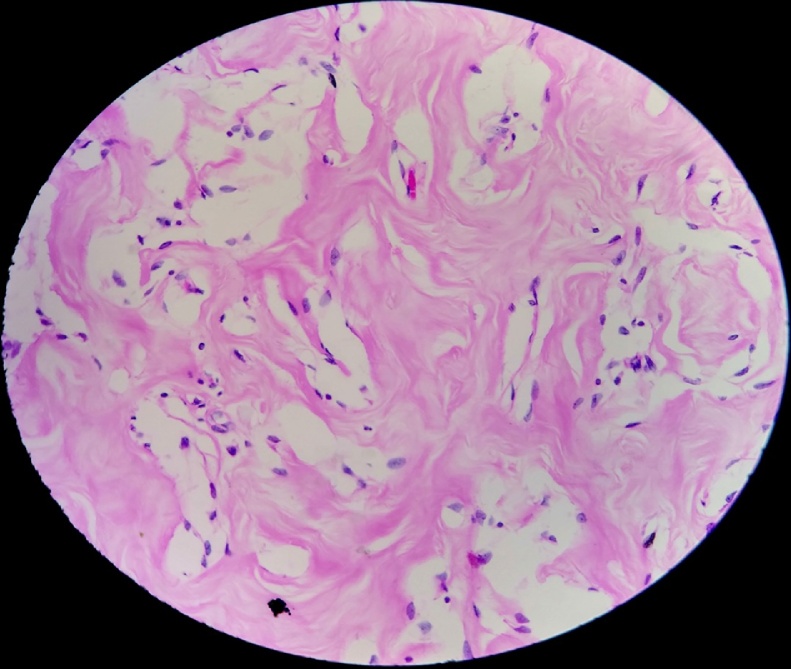

Picture 4.

Histopathological slide showing PASH.

As a part of etiological evaluation laboratory assays were conducted (β Hcg, S.LH, S.FSH, S. prolactin, S.TSH, S.GH, IGF, LFT) which were normal. Breast Ultrasonography was suggestive of gigantomastia with no abnormal findings (BIRADS 2). MRI was planned due to large and dense breasts which had similar findings. Ultrasound guided core cut biopsy of the breast revealed normal breast tissue.

She was planned for bilateral reduction mammoplasty with inverted T scar and wise pattern with superomedial pedicle flap. The objective was of weight and volume reduction of the breasts along with aesthetic enhancement.

She underwent surgery with negative suction drain placement. The excised specimen weighed 3.5 and 5 kg respectively of left and right side breast with an uneventful post-operative period. The histopathology was suggestive of macromastia with pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH) like areas and was focally PR (progesterone receptor) positive on immunohistochemistry.

3. Discussion

The first paper using the term gigantomastia was by Lewison et al. in 1960. Patients with gigantomastia suffer from physical problems, such as mastalgia, ulceration, infection, postural problems, lower back pain, chronic traction injury of the fourth, fifth, and sixth intercostal nerves hence loss of nipple sensation and psychological problems such as social stigma.

Etiological factors for gigantomastia include endogenous hormone stimulation in pregnancy and puberty, drug induced and idiopathic. Patients presenting with excessive breast growth, having no obvious precipitating cause with all hormonal investigations appearing normal are categorized as idiopathic gigantomastia. Drug induced rare associations of gigantomastia include penicillamine [12], neothetazone [13], and cyclosporine [14]. The mechanism of action of these pharmacological agents remains unclear. Cessation of the drug with or without a reduction procedure is the mainstay of treatment.

In 2016 Anne Dancey et al. [15] conducted a meta-analysis of all published cases of gigantomastia irrespective of etiology to give a case series of 115 patients. It included 57 cases of juvenile gigantomastia, 41 cases of pregnancy induced gigantomastia, 13 cases of idiopathic gigantomastia and four cases of drug-induced gigantomastia. Ten patients were noted to have concurrent immunological diseases (myasthenia gravis, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis). In eight cases the gigantomastia was noted to be familial and these presented as juvenile gigantomastia. The results of that study, which indicated puberty and pregnancy to be the major etiology, imply that gigantomastia might be related to endogenous hormonal stimulation.

Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia is a rare but benign mesenchymal proliferative breast lesion presenting mostly in premenopausal women [8,16]. It is found incidentally in approximately 23% of breast biopsies [17], but it is rare for it to manifest clinically. It mimics fibroadenoma and is rare, as fewer than 200 cases have been reported. Bilateral diffuse PASH causing rapid breast enlargement is even rarer, with fewer than 10 cases reported which were idiopathic. In our case the diagnosis was made on histopathology examination of the specimen postoperatively.

As per the available literature Imaging studies in PASH usually show non-specific findings [6]. Mammography does not reveal any abnormalities in most cases. Histologically it is observed as a complex network of slit- like spaces lined by discontinuous endothelial-like flat spindle cells without mitosis or nuclear atypia [18,19], separated by dense collagenous and fibrous areas of stroma. However, these pseudo vascular spaces are not true vascular structures, as they contain no erythrocytes.

The hypothesis that PASH is related to elevated hormone levels is controversial. A study by Erin Bowman et al., a case series of retrospective data analysis of 24 PASH patients found (95%) samples were ER or PR positive which supported a hormonal basis for its development [8] similar to our case where the specimen was PR positive.

Jun Hyeok Kim et al. [10] in 2018 reported a case of Recurrent PASH-caused gigantomastia in a 33-year-old woman which has never been reported in the literature, who had undergone bilateral reduction mammoplasty 4 years back for gigantomastia. Mastectomy was done and histopathology was consistent with findings suggestive of PASH. It is the single case report ever reported for recurrence in PASH associated gigantomastia.

Either Reduction mammoplasty or mastectomy with breast reconstruction can be considered as a preferable line of management. The patients are reluctant to undergo total mastectomy and with little evidence of recurrence in such cases reduction mammoplasty can be planned with explained risk and patient can be kept in close follow-up.

As in this case there was no evidence of any underlying malignant or premalignant disease on radiology and core needle biopsy, keeping in mind the age of the patient we planned for reduction mammoplasty with explained risk of recurrence due to hypertrophy of the remaining breast tissue.

Most authors conclude that gigantomastia cannot be influenced by conservative or medical treatment and only resolves with surgical maneuvers. Moreover with hormonal therapy even if attempted the results will be very slow and inconsistent and with such a huge size of breasts symptomatic relief is expected to take a very long time.

Among the various techniques available inverted T scar pattern and superiomedical pedicle was preferred as the learning curve is shorter, have the greatest versatility, and it is reproducible with consistent and predictable results [2]. Surgery can make a significant improvement in quality of life of these patients with immediate relief. As the etiology of the disease is poorly understood, these patients need proper endocrinological and radiological evaluation before any treatment can be planned.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

No approval is required for this type of study.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Author contribution

All the authors had role in data collection, writing of paper and review of case with follow up.

Registration of research studies

N/A.

Guarantor

Dr Aakansha Vashistha, Dr Prabha Om, Dr Farukh khan, Dr Manish Rundla.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Journal Name: Journal of Case Reports and Images in … [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 19]. Available from: https://www.ijcrisurgery.com/archive/early_view_articles/28_Z12_2016040014_CR_EV.pdf.

- 2.Find in a Library With WorldCat. 2020. Stone’s plastic surgery facts and figures [Internet]https://www.worldcat.org/title/stones-plastic-surgery-facts-and-figures/oclc/768771290 [cited 2020 Sep 19]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoda I. Syed A., Brogi Edi, Koerner Fred, Rosen Paul Peter. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2014. Rosen’s Breast Pathology; p. 152. ISBN 978-1- 4698-7070-0. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma K., Nigam S., Khurana N., Chaturvedi K.U. Unilateral gestational macromastia—a rare disorder. Malays. J. Pathol. 2004;26(2):125–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thorne Charles. In: Grabb and Smith’s Plastic Surgery: Editor-in-Chief. seventh edition. Thorne Charles H., Chung Kevin C., Gosain Arun, Gurtner Geoffrey C., Mehrara Babak Joseph, Peter Rubin J., Spear Scott L., editors. Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health; Philadelphia: 2014. p. 593. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wieman S.M., Landercasper J., Johnson J.M. Tumoral pseudoangi- omatous stromal hyperplasia of the breast. Am. Surg. 2008;74:1211–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vuitch M.F., Rosen P.P., Erlandson R.A. Pseudoangiomatous hyperplasia of mammary stroma. Hum. Pathol. 1986;17:185–191. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(86)80292-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowman E., Oprea G., Okoli J. Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH) of the breast: a series of 24 patients. Breast J. 2012;18:242–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2012.01230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho Min Jeng, Yang Jung-Hyun, Choi Hyeon-Gon, Kim Wan Seop, Yu Yeong-Beom, Park Kyoung Sik. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2015;88(March (3)):166–169. doi: 10.4174/astr.2015.88.3.166. Published online 2015 Feb 27, PMCID: PMC4347046 PMID: 25741497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim Jun Hyeok, Baek Seung Eun, Yoo Tae Kyung, Lee Ahwon, Oh Deuk Young. Relapsed bilateral gigantomastia caused by pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia after reduction mammoplasty. Arch. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2018;24(2):78–82. doi: 10.14730/aaps.2018.24.2.78. pISSN: 2234-0831 eISSN: 2288-9337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A., Orgill D.P., For the SCARE Group The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakai Y., Wakamatsu S., Ono K. Gigantomastia induced by bucillamine. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2002;49:193–195. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200208000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott E.H.M. Hypertrophy of the breast, possibly related to med- ication: a case report. S. Afr. Med. J. 1970;44:449–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cerveli V., Orlando G., Giudiceandre F. Gigantomastia and breast lumps in a kidney transplant recipient. Transplant. Clin. Immunol. 1999;31:3224–3225. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(99)00701-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dancey Anne, Khan M., Dawson J., Peart F. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery; Selly Oak Hospital, Birmingham, UK: 2007. British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferreira M., Albarracin C.T., Resetkova E. Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia tumor: a clinical, radiologic and pathologic study of 26 cases. Mod. Pathol. 2008;21:201–207. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3801003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ibrahim R.E., Sciotto C.G., Weidner N. Pseudoangiomatous hyperplasia of mammary stroma. Some observations regarding its clinicopatho- logic spectrum. Cancer. 1989;63:1154–1160. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890315)63:6<1154::aid-cncr2820630619>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nassar H., Elieff M.P., Kronz J.D. Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH) of the breast with foci of morphologic malignancy: a case of PASH with malignant transformation? Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010;18:564–569. doi: 10.1177/1066896908320835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deniz S., Vardar E., Öztürk R. Pseudo-angiomatous stromal hy- perplasia of the breast detecting in mammography: case report and review of the literature. Breast Dis. 2014;34:117–120. doi: 10.3233/BD-130360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]