Highlights

-

•

Diffuse angiosarcoma of the heart cause non-specific symptoms fever and chest pain.

-

•

It is difficult to diagnose because no solid tumor can be detected.

-

•

A high level of suspicion is a premise to initiate biopsies of the pericardium and myocardium.

Keywords: Cardiac angiosarcoma, Haemoptysis, Pulmonary infiltrates, Transoesophageal echocardiography, Autopsy

Abstract

Introduction

We present a very rare case with diffuse cardiac angiosarcoma. Because all symptoms are often non-specific, this diagnosis is difficult to establish. To our knowledge this is the first clinical description of this rare disease.

Presentation of case

A 47-year-old female presented with bilateral pulmonary infiltrates and non-specific symptoms as fever, chest pain and dyspnoea on exertion. She was treated with antibiotics for suspected lung infection but deteriorated developing rapid recurrent pleural effusion. Her transthoracic- and transoesophageal-echocardiography as well as the thoracentesis and endobronchial ultrasound findings were normal. A minimally invasive pulmonary wedge resection, partial pleurectomy and pericardial fenestration was performed. The pathologic interpretation of these specimen was very difficult and a correct diagnosis could be made only by the second reference pathologist. While awaiting reference histology report she was administered high-flow oxygen therapy for hypoxia, antibiotics, catecholamines and corticosteroids. The patient deteriorated very rapidly and died in the ICU.

Discussion

As in earlier studies, misdiagnosis delayed the actual diagnosis, especially because there was no clinical suspicion for angiosarcoma. Pathologic evaluation may be difficult because different growth patterns may be present in the same tumour and pleural or lung specimen may show only very tiny tumour formations within a fibrosing tissue changes.

Conclusion

This case report highlights the difficulties to establish a diagnosis of diffuse angiosarcoma in time. An early diagnosis, to initiate oncologic treatment, require a high level of clinical suspicion and a histological proof from pericardial or myocardial biopsy.

1. Introduction

Angiosarcoma involving the heart and lungs is a rare disorder with less known clinical features [1]. It is an aggressive subtype of soft-tissue sarcoma with a propensity for local recurrence and metastasis associated with a generally poor prognosis, unless diagnosed early [2]. According to the WHO histological classification of tumours of the heart and pericardium, the main groups are benign tumours, tumours of uncertain biologic behaviour, germ cell tumours and malign tumours. The majority of the malignant primary tumours can be categorized into three main types: sarcomas, primary cardiac lymphoma and metastatic tumours of the heart [3]. The incidence of cardiac tumours in autopsy cases has been reported from 0.0017% to 0.33 [4].

Seventy five percent of primary cardiac tumours are benign and 25% are malignant, of which 95% are sarcomas and the remaining 5% include lymphomas [5,6]. Angiosarcoma, accounts for around 30% of primary malignant lesions of the heart [4,5]. Primary cardiac tumours usually present with symptoms and clinical signs resulting from intracardiac obstruction and systemic embolization or recurrent pericardial effusion in a patient with otherwise nonspecific symptoms and without pertinent medical history as well. Systemic or constitutional symptoms may be present [7,8]. They are diagnosed most often through transthoracic echocardiograms (TTE) and transoesophageal echocardiograms (TEE), MRI, and CT scan [7].

We report an unusual case of an advanced cardiac angiosarcoma that presented a diagnostic challenge as the symptoms indicated for pulmonary infection and imaging diagnostics did not show any solid tumour. Neither the standard laboratory nor an earlier reference laboratory workup correlated to angiosarcoma. Unfortunately, this medical mystery could only be solved post-mortem. The aim of this report is to enable the reader to consider diffuse angiosarcoma as a cause for non-specific symptoms and/or cardiac restriction at an earlier stage of disease.

2. Materials and methods

The patient documents, diagnostics and treatment modalities were retrospectively evaluated by the authors and are presented here. This work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [10]. Despite exhaustive attempts to contact the only living family member of the deceased patient, this was unsuccessful. Therefore the paper was sufficiently anonymised not to cause harm to the patient or their family.

3. Case description

A 47-year old unmarried female, with a history of hypothyroidism and diagnosed with endometriosis was evaluated for bilateral pulmonary infiltrates in April 2019. She had a history of fever, chest pain and dyspnoea on exertion. The patient reported to have decreased appetite, increased fatigue, haemoptysis and yellowish expectorates since February 2019. Contrast-CT of the chest excluded major pulmonary artery embolism, revealed small ground-glass opacities and consolidations resembling pneumonic infiltrates (Figs. 1a, b and 2a). The patient required cardiopulmonary resuscitation following anaphylactic shock caused by contrast medium at that day. TTE and TEE were done shortly afterwards by a cardiologist but no abnormal findings were reported.

Fig. 1.

Chest CT scans.

Chest CT scan with contrast medium (a,b) and follow-up native CT-scan showing a certain progression of pleural effusion and pulmonary infiltrates, non-specific for lung metastases. 1a & b: chest CT scan 11/04/2019 with small infiltrates, atelectasis and a subpleural nodule. Mild cardiomegaly. 1c & d: chest CT scan 15/05/2019 with bilateral pleural effusion and blurry infiltrates on the right side.

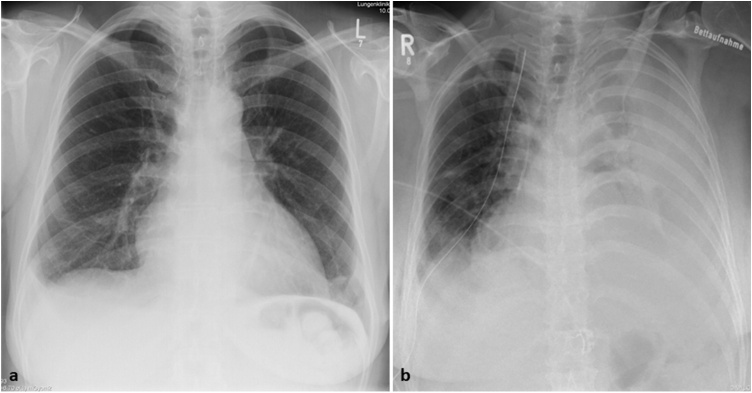

Fig. 2.

Chest X-rays.

Chest X-rays with mild cardiomegaly at initial presentation and massive progression of bilateral pleural effusion during second admission. 2a: Chest X-ray at the time of first admission. 2b: Chest X-ray, 5 weeks thereafter.

Considering her persistent symptoms of chest pain and bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, she was referred to us at Lungenklinik Hemer (tertiary care pulmonary hospital), where we excluded a pulmonary tuberculosis. Her laboratory investigations revealed signs of a bronchopulmonary infection with elevated C-reactive protein. In flexible bronchoscopy investigation, serous and some purulent secretion was found. No pathological microorganism was observed in the bronchoalveolar lavage. Hence, empirically oral antibiotics were prescribed and the patient was discharged into ambulatory care and follow-up.

She presented again to our hospital three weeks later. Her blood tests revealed elevated eosinophils to 10% (normal < 7%), C-reactive protein of 6.5 (normal <0.8) mg/dl and D-Dimer up to 4 (normal <0.8) mg/l. On the day of admission her chest X-ray showed a mild cardiomegaly and a minimal right sided pleural effusion (Fig. 1a). Pleural tapping was performed with both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, but no malignant cells and no mycobacterium bacilli were found in the pleural effusion. Repeated bronchoalveolar lavage revealed negative bacteriological and mycological results. Endobronchial ultrasound with transbronchial needle aspiration was performed to clarify pulmonary infiltrates and exclude atypical mycobacteriosis. Both the endobronchial and transbronchial lymph node and lung biopsies were normal. Neither evidence of any tumour nor malignancy was noted even in repeated cytological or immunocytochemistry investigations. The subsequent chest X-ray detected cardiomegaly, the repeated TTE examination showed a moderate pericardial effusion, but a good left ventricular function and no right ventricular failure. The patient’s general condition was deteriorating. The rapid changes with a massive pleural effusion led treating doctors to focus more on lungs and pleural problem. We repeated CT-scan of the chest without intravenous contrast medium, which revealed pulmonary subsegmental atelectasis, progressive consolidation of the ground-glass opacities with infiltration in the middle lobe and a large bilateral pleural effusion with compression atelectasis of lower lobes, cardiomegaly, and pericardial effusion (Figs. 1c & 2d). Within a period of 14 days, she progressed to a massive pleural effusion, requiring pleural drainage (Fig. 2b). And to tackle recurrent pleural effusions, chest tubes were placed bilaterally.

Since the aforementioned changes could not be explained with the available laboratory pathological, microbiological or immunological reports, video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) with partial pleurectomy, pericardial fenestration and diagnostic wedge resection was indicated and performed by a surgical specialist. The patient could not tolerate single lung ventilation that hindered us from performing a complete exploration of the thorax. Postoperatively the clinical status exhibited only slight improvement with less exhaustion during bed side mobilisation. However, the pleura was thickened pointing towards an active serositis.

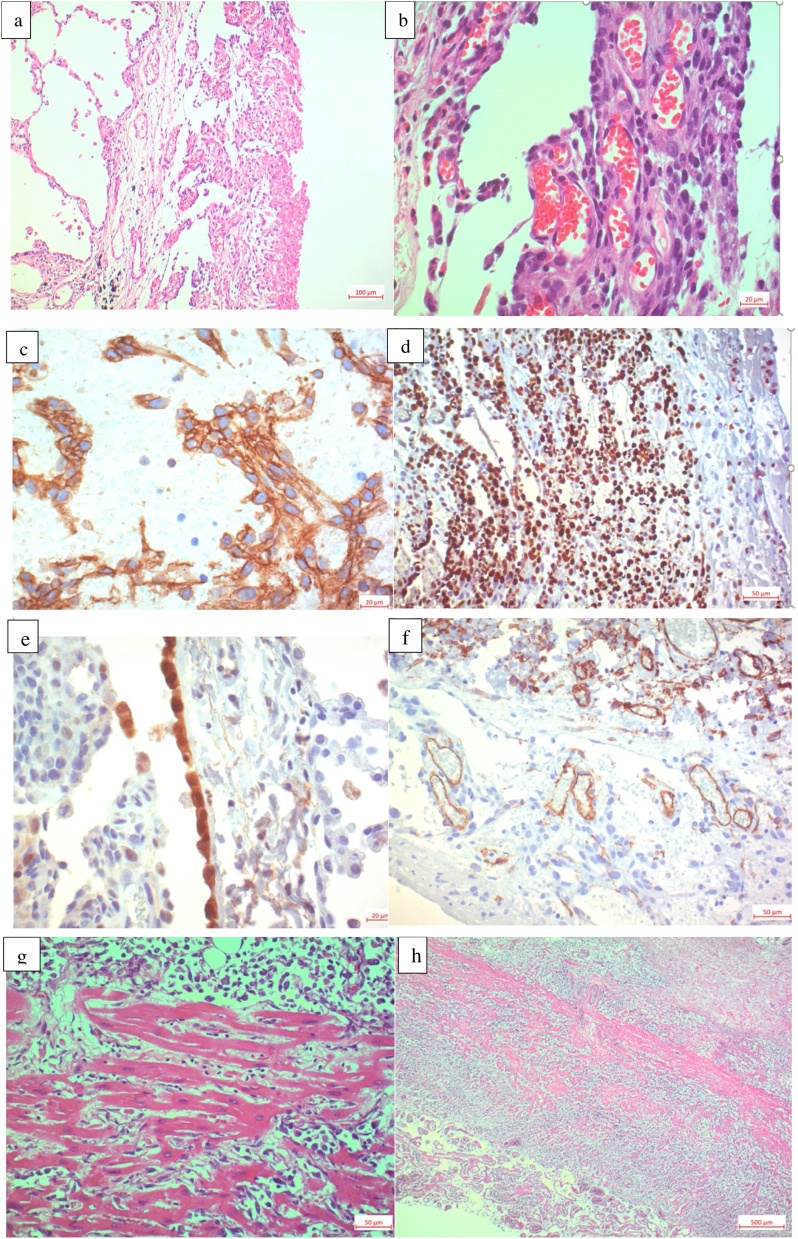

The histological examination of parietal pleura and wedge of right Segment 10 was initially interpreted as mesothelial hyperplasia. The pathologist interpreted the expression of the immunohistochemical markers CD31 and D2-40 as a vascular neoplasm, possibly of lymphatic origin (Fig. 3a–f). A carcinoma, lymphoma and mesothelioma could be ruled out by exclusion. Due to the rarity of these findings and the lack of conclusive diagnosis from the pleura and lung biopsies, a second pathologic opinion was requested. This report arrived 14 days later and favoured a lymphatic vascular proliferation of intermediate malignancy, possibly an epithelioid haemangioendothelioma. These specimens were sent for a third pathologic opinion. While waiting for reference report the patient passed away in the intensive care unit (ICU), despite optimum care provided by the medical team. Post-mortem, the family as well as the medical team mutually agreed to determine a precise cause of death through an autopsy.

Fig. 3.

Histology from autopsy specimen. Histology from lung wedge resection specimen. a H&E-stained alveolar lung tissue, 100×. Visceral pleura covered with a vascular tumor and a fibrin coat on the right side. b H&E stained 400× pleural specimen with intratumor vessels. c Positive stain with the panvascular marker CD31, 400×. d Immunohistochemistry stained with MIB-1 showing 60% proliferative cells with brown nuclear staining, 200×. e Calretinine stained lung tissue negative inside the tumor but one positive mesothelial layer, 400×. f CD34 stained tumor: negative within the tumor vessels but positive within the internal control of non-neoplastic vessels, 200×. g H&E-stained heart muscle with diffuse angiosarcoma infiltration of the myocardiumh H&E-stained specimen showing pulmonary vein infiltration, 25×.

The autopsy revealed a diffuse cardiac angiosarcoma involving the entire heart, with myocardium infiltration, intrapericardial adhesions and a near complete pericardial sac obliteration. The tumour tissue surrounded the pulmonary trunk including pulmonary arteries and visceral pleura bilaterally. In the autopsy specimen, the typical cellular atypia / anaplasia and geographic necrosis were more obvious (Fig. 3g & h) than in the biopsy specimen. The second referential pathologic interpretation was received 18 days’ post-mortem and confirmed angiosarcoma in all specimens (Fig. 3a–f).

4. Discussion and conclusion

This was a rare diagnostic challenge with abnormally rapid deterioration of the patient. Unfortunately, she passed away while awaiting a conclusive histological diagnosis from the reference laboratory. Although we have ample experience in treating lung as well as soft tissue tumours, we could not correspond any such difficult and unclear case in terms of diagnosis.

4.1. Clinical difficulties

Approximately 80% of cardiac angiosarcoma cases have been reported to originate in the right atrium and patients often present with dyspnoea, chest pain, hypotension, tachycardia and syncope [2]. Other symptoms such as arrhythmias and pericardial effusions, emboli, could result from atrial wall invasion and are combined with fever and weakness in some cases [11]. Although dyspnoea on exertion, mild fever and chest pain were present in our patient, these remain non-specific symptoms. Only the draining of haemorrhagic effusion during pericardial fenestration was an indicator of malignancy. Evidence has shown that these malignant tumours are frequently associated with haemorrhagic pericardial effusion [8,11,12].

On chest radiography, as in our case, the most common but non-specific finding is cardiomegaly [2]. Interestingly, others found TTE to have 75% sensitivity in detecting primary cardiac angiosarcoma with tumour extension into the pericardium causing pericardial effusion in 88%. Left ventricular ejection fraction was preserved in 94% of the patients and pericardial fluid cytology was negative for malignant cells in all tested patients (100%) [12]. In our case and truly unfortunate, her TTE, TEE, chest CT, pleural fluid and bronchoalveolar lavage cytology and the transbronchial lymph node biopsies did not give any definitive clues towards malignancy. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) might have been better than CT in characterizing the soft tissue and distinguishing between different abnormalities specific to the myocardium. In addition, it can help distinguish between thrombi and tumour in the cardiac cavity [13]. Due to unaccepted bleeding risk and low sensitivity, heart biopsy or pericardial fluid cytology testing is rarely used [11].

In earlier studies, misdiagnosis often delayed the actual diagnosis, especially because clinicians generally had a low level of clinical suspicion for angiosarcoma, as it was true for our patient. Metastases, mainly pulmonary are present in around 36%–80% of patients at the time of diagnosis [8,9,14] allowing for only palliative treatment strategies [11]. The overall survival of angiosarcoma is poor, with a reported 3–15 months and most patients develop distant metastases [6,9]. The pulmonary manifestation in our case was ground glass opacities and infiltrates without any solid nodules and thus making it more suspicious for infection than sarcoma metastases. During her treatment, the massive bilateral effusions were the only obvious findings of severe illness (Fig. 2b). As the autopsy report indicated -a layer of tumour tissue encased the heart including the auricles, the pericardium, the pulmonary trunk, the pulmonary arteries, and the visceral pleura bilaterally-, it is easy to understand, why all the medical investigations performed failed to discover such a diffuse lesion.

4.2. Pathological difficulties

Not just the clinical diagnostics but the cytological examinations of the bronchial aspirates, pleural fluid and transbronchial needle aspiration of lymph nodes failed to produce any conclusive findings.

Angiosarcoma can be diagnosed when cytology shows abnormal mitoses, single malignant cells, 3-dimensional clusters, multiple prominent or bar-shaped nucleoli and vasoformative features, including hemophagocytosis, cytoplasmic lumina/vacuoles containing red blood cells and endothelial wrapping but a high index of suspicion is required for an accurate diagnosis [15]. Macroscopically, cardiac angiosarcoma present with two different types of growth; a well-defined mass with haemorrhagic and necrotic components extending from the pericardium into the cardiac chamber or a diffusely infiltrating mass with extension into the pericardium [2]. The latter one was found in our patient.

The myocardium may be infiltrated by spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei, frequent mitotic figures, rare giant cells, and extensive areas of necrosis. These spindle cells tend to create vascular channels [16]. Even direct tumour biopsies and histopathological examination may be insufficient to establish the definitive diagnosis [14]. Heart angiosarcoma may be difficult to identify because different growth patterns may be present in the same tumour: a vascular area with anatomizing channels, a solid high-grade epithelioid area, or a spindle cell Kaposi-like area. Cardiac angiosarcoma have well differentiated vascular channels mixed with poorly differentiated solid areas of epithelioid cells and spindle cells which hamper the success of initial biopsy diagnosis with variations depending on the area evaluated by the pathologist [13].

In our case, the tentative diagnosis from the operative specimen was a vascular tumour of intermediate grade, probably epithelioid haemangioendothelioma. Local invasion of myocardium, large vessels and lymph node involvement were first seen in the autopsy, leading to the final diagnosis. Furthermore, cellular atypia/anaplasia and geographic necrosis were more obvious at the autopsy material compared to the ante-mortem lung and pleural specimen with only very tiny tumour formations within a fibrosing pleuritis.

4.3. Management difficulties

Due to the rarity of this fatal condition and the lack of a specific clinical presentation, the diagnosis of cardiac angiosarcoma requires a high degree of suspicion and urgent initiation of therapy, whereby most cardiac angiosarcomas are found in late stages making a complete resection impossible [14]. In our patient the initiating of an early oncological therapy with nothing but a vague indication of haemangioendothelioma would not have been medically sound. The extremely rapid disease progression made a definitive therapy even more challenging. Even today, in everyday clinical practice and with all the diagnostic tools available, recognising a cardiac tumour especially a malignant one, still remains arduous. Woefully, patients with advanced cardiac malignancies can more than often, only be offered best supportive care aiming to alleviate the symptoms but a curative approach is usually out of question. To put this into our patient’s perspective, an early diagnosis could have at least facilitated a palliative chemotherapy.

In conclusion, detecting cardiac tumours is challenging and can only be achieved by keeping a keen eye on the patient history, signs and symptoms as well as clinical findings. A diffuse cardiac angiosarcoma might be more difficult to diagnose based on TEE as compared to other solid cardiac malignancies. Moreover, in presence of non-specific symptoms in addition to signs of cardiac restriction, a cardiac angiosarcoma should be ruled out. The diffuse wallpaper like tumor growth encompassing the mediastinal structures leading to diagnostic confusion and difficulty in establishing a cytological or a histological diagnosis are the two most important factors presenting as major hindrances towards a timely diagnosis and in turn treatment. We recommend that these factors will be kept in mind, while diagnosing and treating similar cases in the future.

Conflicts of interest

All authors negate any conflict of interest

Funding

This paper was prepared without any funding.

Ethical approval

This is a case report consented in the hospitals review board. Ethical committee approval was waived because the patient faded away and no details allowing identification are presented.

Consent

The patient is not alive anymore and this case report describes his rapid disease progression. The relatives could not be reached.

Authors’ contributions

SDK: conceived and designed the manuscript, collected data and wrote the paper. MW: interpreted data, reviewed manuscript and performed technical analyses. HM: provided histology figures and descriptions, critically reviewed manuscript, and performed technical analyses. JA: provided histology figures and descriptions, performed technical analysis and drafted the article. VG: Reviewed manuscript, performed literature search and performed technical analysis. SW: performed conception of the paper, wrote and reviewed the manuscript and collected the data, performed technical analyses and prepared final drafting.

Registration of research studies

Not Applicable.

Guarantor

PD Dr. Stefan Welter.

Provenance, availability of data and materials

This report originates from Germany and was written by the treating doctors and not commissioned. All relevant information is published in this Case Report. However, if additional information is required, the corresponding author can be reached via email. This paper was externally peer-reviewed before publication.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- 1.Silverman N.A. Ann. Surg. 1980;191(2) doi: 10.1097/00000658-198002000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaballah A.H., Jensen C.T., Palmquist S., Pickhardt P.J., Duran A., Broering G. Angiosarcoma: clinical and imaging features from head to toe. Br. J. Radiol. 2017;90(1075) doi: 10.1259/bjr.20170039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke A., Tavora F. The 2015 WHO Classification of tumors of the heart and pericardium. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amano J., Nakayama J., Yoshimura Y., Ikeda U. Clinical classification of cardiovascular tumors and tumor-like lesions, and its incidences. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2013;61(8):435–447. doi: 10.1007/s11748-013-0214-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silverman N.A. Primary cardiac tumors. Ann. Surg. 1980 doi: 10.1097/00000658-198002000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffmeier A., Sindermann J.R., Scheld H.H., Martens S. Cardiac tumors--diagnosis and surgical treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int [Internet] 2014;111(March (12)):205–211. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0205. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24717305 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butany J., Nair V., Naseemuddin A., Nair G.M., Catton C., Yau T. Cardiac tumours: diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:219–228. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riles E., Gupta S., Wang D.D., Tobin K. Primary cardiac angiosarcoma: A diagnostic challenge in a young man with recurrent pericardial effusions. Exp. Clin. Cardiol. 2012;17(March (1)):39–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen T.W.W., Loong H.H., Srikanthan A., Zer A., Barua R., Butany J. Primary cardiac sarcomas: a multi-national retrospective review. Cancer Med. 2019 doi: 10.1002/cam4.1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A.J., Orgill D.P. The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linfeng Q., Xingjie X., Henry D., Zhedong W., Hongfei X., Haige Z. Cardiac angiosarcoma. 2019;49(December 2018):10–13. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kupsky D.F., Newman D.B., Kumar G., Maleszewski J.J., Edwards W.D., Klarich K.W. Echocardiographic features of cardiac angiosarcomas: the mayo clinic experience (1976-2013) Echocardiography. 2016;33(February (2)):186–192. doi: 10.1111/echo.13060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel S.D., Peterson A., Bartczak A., Lee S., Chojnowski S., Gajewski P. Primary cardiac angiosarcoma - a review. Med. Sci. Monit. 2014;20:103–109. doi: 10.12659/MSM.889875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ostrowski S., Marcinkiewicz A., Kośmider A., Jaszewski R. Sarcomas of the heart as a difficult interdisciplinary problem. Arch. Med. Sci. 2014;10(February (1)):135–148. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2014.40741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geller R.L., Hookim K., Sullivan H.C., Stuart L.N., Edgar M.A., Reid M.D. Cytologic features of angiosarcoma: a review of 26 cases diagnosed on FNA. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016;124(9):659–668. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basso C., Valente M., Poletti A., Casarotto D., Thiene G. Surgical pathology of primary cardiac and pericardial tumors. Eur J Cardio-thoracic Surg. 1997;12(November (5)):730–738. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(97)00246-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This report originates from Germany and was written by the treating doctors and not commissioned. All relevant information is published in this Case Report. However, if additional information is required, the corresponding author can be reached via email. This paper was externally peer-reviewed before publication.