Abstract

Background and aim

Over 80% (365/454) of the nation’s centers participated in the Italian Society of Nephrology COVID-19 Survey. Out of 60,441 surveyed patients, 1368 were infected as of April 23rd, 2020. However, center-specific proportions showed substantial heterogeneity. We therefore undertook new analyses to identify explanatory factors, contextual effects, and decision rules for infection containment.

Methods

We investigated fixed factors and contextual effects by multilevel modeling. Classification and Regression Tree (CART) analysis was used to develop decision rules.

Results

Increased positivity among hemodialysis patients was predicted by center location [incidence rate ratio (IRR) 1.34, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.20–1.51], positive healthcare workers (IRR 1.09, 95% CI 1.02–1.17), test-all policy (IRR 5.94, 95% CI 3.36–10.45), and infected proportion in the general population (IRR 1.002, 95% CI 1.001–1.003) (all p < 0.01). Conversely, lockdown duration exerted a protective effect (IRR 0.95, 95% CI 0.94–0.98) (p < 0.01). The province-contextual effects accounted for 10% of the total variability. Predictive factors for peritoneal dialysis and transplant cases were center location and infected proportion in the general population. Using recursive partitioning, we identified decision thresholds at general population incidence ≥ 229 per 100,000 and at ≥ 3 positive healthcare workers.

Conclusions

Beyond fixed risk factors, shared with the general population, the increased and heterogeneous proportion of positive patients is related to the center’s testing policy, the number of positive patients and healthcare workers, and to contextual effects at the province level. Nephrology centers may adopt simple decision rules to strengthen containment measures timely.

Keywords: COVID-19, Renal replacement therapy, Contextual analysis, Classification tree

Introduction

The spread and dynamics of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Italy posed serious threats to the ability and preparedness of nephrology centers to respond to the needs of patients on renal replacement therapy (RRT) during the exponential phase of the pandemic. At that time, sparse and scattered data were available on RRT patients and centers. Among the actions taken to provide clinicians and health authorities with nationwide data, the Italian Society of Nephrology launched a survey to evaluate the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the Nephrology and Dialysis Units [1]. The study aimed to estimate the cumulative incidence of SARS-CoV-2 positive cases among hemodialysis (HD), peritoneal dialysis (PD), and renal transplant (TX) patients. It revealed some intriguing findings: higher rates of positive cases in HD than in PD and TX patients, and heterogeneous spread among Italian regions. The proportion of deceased SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals was shockingly high in HD patients, and such an unfavorable outcome also occurred more frequently in PD and TX patients than in the general population [2, 3].

The pandemic struck RRT centers and patients dramatically, and although specific protocols were soon developed and endorsed [4, 5], the absence of effective and evidence-based treatments left Nephrologists substantially defenseless. Thus, prevention and meticulous infection control remained, and perhaps still remains, the only broadly applicable barrier against SARS-CoV-2 spread and its deadly consequences.

The findings of our first article [1] were descriptive in nature and elicited three further and newer research issues that we address in the present report. First, which are the possible explanatory factors for the heterogeneous proportions of SARS-CoV-2 positivity in Italian nephrology centers? Second, to what extent is the higher frequency of SARS-CoV-2 positivity in HD patients associated with the spread of the virus within the dialysis centers? Third, how can we translate the survey findings into easily and widely applicable clinical decision rules?

To address these specific questions, we designed a “de-novo” analysis cycle based on multilevel modeling and classification trees. We used mixed-effect models to identify the explanatory factors of the heterogeneous infection spread while accounting for the control measures and policies currently being adopted by each center. Using classification and regression trees we sought to develop a simple decision algorithm to stratify the probability of SARS-CoV-2 positivity in each center.

Methods

Study oversight

The Italian Society of Nephrology (SIN) COVID-19 research group designed a nationwide survey to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on nephrology centers and patients. Details of the survey design, instruments, and procedures can be found in Reference 1. Briefly, on average, within 11 days, the vast majority [365/454 (80.4%)] of invited centers completed and returned the survey questionnaire, an instrument designed to obtain 17 key pieces of information about patients, workforce, and facilities during the exponential phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. All returned files were checked for consistency and merged in the survey database.

Statistical analysis

A preliminary exploratory analysis was performed to detect zero inflation in the count of SARS-CoV-2 positive patients and subsequent deaths. These latter outcomes were the model dependent variables, and the center prevalent patients represented the exposed population. We then assessed the multivariable association with the count SARS-CoV-2 positive cases among healthcare workers, and the HD cases admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) as continuous explanatory variables. Center testing policies for patients and staff, telephone triage, in-person triage, and use of personal protective equipment (PPE) entered the models as binary co-variables. Additionally, for each center, we derived the number of days elapsed since the local lockdown date [6], and the cumulative rate of positive cases in the local general population as of April 23rd [7]. Since centers are clustered in provinces and provinces in regions, three multilevel models were considered. Model 1 included provinces as the second level, model 2 included regions as the second level, and model 3 provinces nested into regions. We used both the multilevel Poisson regression and the multilevel negative binomial regression for each model, and we chose the best model using the likelihood-ratio (LR) test, when applicable, and the Akaike’s information criterion (AIC).

For the multilevel model, we estimated the variance partition coefficient (VPC) that is the proportion of variation that is beyond what explained by the fixed predictors and informs on the existence of a contextual effect [8]. Fixed predictor coefficients were exponentiated and reported as cumulative incidence rate ratios (IRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

We used Classification and Regression Tree (CART) analysis [9–11] to develop a simple and interpretable set of rules to support clinical decision making. Tree-based models are a class of nonparametric algorithms that work by partitioning the feature space into a number of non-overlapping regions with similar response values using a set of splitting rules.

The presence or absence of SARS-CoV-2 positivity was the target variable. A tenfold cross-validation method was used to evaluate the model reliability. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 15 (StataCorp LLC, TX, USA), and R Software Ver 4.0.2 (R Core Team, 2020).

Geospatial analysis

Geographical Information System (GIS) technology was used to produce multilevel maps of the model predictions on Italian provinces using the Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT) shapefiles [12]. Geospatial mapping was performed using R Software Ver 4.0.2 (R Core Team, 2020).

Results

The SIN COVID Survey Database [1] included data collected from 365 Italian nephrology centers and involved 30,821 HD, 4139 PD, and 25,481 kidney TX patients, for a total of 60,441 RRT patients.

On April 23rd, 2020, the cumulative incidence of SARS-CoV-2 positive cases was 3.55% (95% CI 3.34–3.76) in HD patients, 1.38% (95% CI 1.04–1.78) in PD patients and 0.86% (95% CI 0.75–0.98) in TX patients [1]. The distribution of SARS-CoV-2 cases among RRT patients was positively skewed (skewness = 5.53), with an average of 3.7 positive patients per center but with a variance of 88.7 (min 0; max 105).

Multilevel modeling of SARS-CoV-2 positive cases

Multilevel negative binomial regression predicted SARS-CoV-2 positivity better than multilevel Poisson and zero-inflated regression (Table 1). The inclusion of random effects at the second level significantly improved the model fit (χ2 = 3.30, p = 0.034). Among candidate second level variables, the model with provinces as cluster-specific random effect had the lowest AIC (Table 1).

Table 1.

Model selection for prediction of SARS-CoV-2 infection among HD patients

| Model | Second level | Third level | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poisson regression | 1540.02 | 1571.16 | ||

| Zero-inflated Poisson regression | 1475.54 | 1510.57 | ||

| Mixed-effects Poisson regression | Province | 1221.71 | 1256.74 | |

| Negative binomial regression | 1108.27 | 1143.29 | ||

| Mixed-effects negative binomial regression | Region | 1104.78 | 1143.70 | |

| Mixed-effects negative binomial regression | Province | Region | 1102.63 | 1145.44 |

| Mixed-effects negative binomial regression | Province | 1100.12 | 1139.03 |

AIC Akaike information criterion, BIC Bayesian information criterion

The independent factors (Table 2) associated with increased rates of SARS-CoV-2 positive HD patients were: the geographical latitude of the center (IRR 1.34, 95% CI 1.20–1.51), the positivity rate in the contextual general population (IRR 1.002; 95% CI 1.001–1.003), the count of SARS-CoV-2 positive healthcare workers (IRR 1.09; 95% CI 1.02–1.17), and the test-all policy for both patients and healthcare workers as an interaction term (IRR 5.94, 95% CI 3.36–10.45). Conversely, the number of days since the lockdown date had a protective effect (IRR 0.95, 95% CI 0.94–0.98). The second level effect was significant, and the contextual effect explained, on average, 10% of the total variability [VPC = 0.10 (range 0.002–0.210)]. The net effect of the province as second level variable, holding fixed the first level factors, is shown in Fig. 1 and mapped in Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Independent factors associated with the rate of SARS-CoV-2 positive cases in hemodialysis patients

| Factors | Units | IRR | Z | p value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographical latitude | 1° | 1.34 | 6.28 | < 0.0001 | 1.20–1.51 |

| Number of positive cases in the dialysis centers’ province | 100 cases | 1.002 | 2,60 | 0.009 | 1.001–1.003 |

| Positive HCWs | 1 case | 1.09 | 3.41 | 0.001 | 1.02–1.17 |

| Testing all HCWs | Yes vs No | 1.37 | 1.30 | 0.194 | 0.85 -2.31 |

| Testing all patients | Yes vs No | 1.67 | 1.04 | 0.297 | 0.64–4.38 |

| Testing all HCWs and patients | Yes vs No | 5.94 | 6.12 | < 0.0001 | 3.36–10.45 |

| Days in lockdown | 1 day | 0.95 | − 5.16 | < 0.0001 | 0.94–0.98 |

| Second level random effect | |||||

| Variance: 0.283 (SE:0.19) | VPC = 0.104 | Range 0.02–0.21 | |||

IRR incidence rate ratio, CI confidence interval, VPC variance partition coefficient, HCWs healthcare workers

Fig. 1.

Predicted post-estimation counts with 95% confidence intervals by province and ranked from the lowest to the highest. Although the variability is high, only three provinces are significantly different from zero

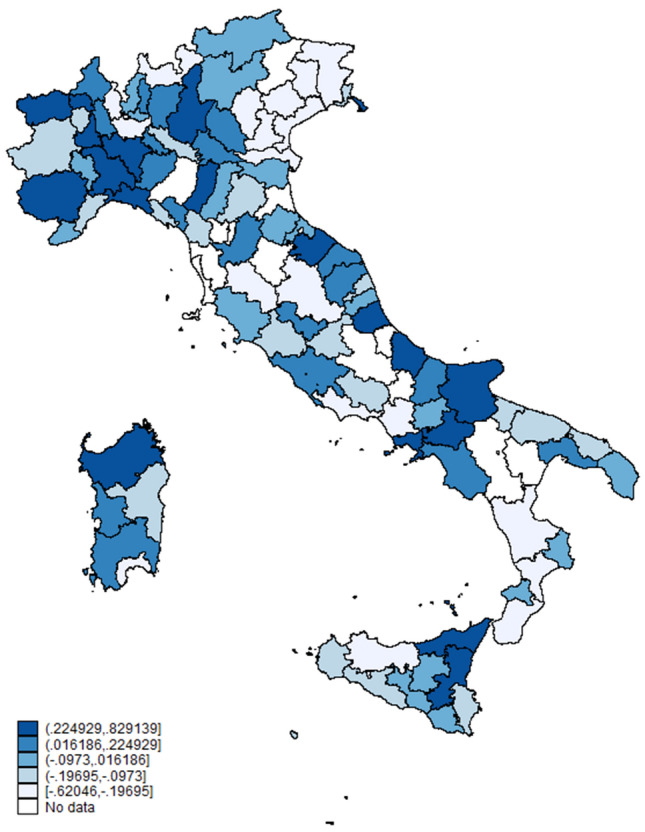

Fig. 2.

Predicted post-estimation count due to the general contextual effect at the province level. A negative value indicates that the contextual effect reduces the expected count, a near null value indicates that the contextual effect is negligible, a positive value suggests an increase in the expected count due to the contextual effect

The SARS-CoV-2 positivity rate in PD patients was associated with the cumulative incidence of positive cases in the province general population (IRR 1.10, 95% CI 1.05–1.20), and with geographical latitude of the centers (IRR 1.42, 95% CI 1.18–1.70) (Table 3). We found no formal evidence for higher-level effects, and the final estimates obtained from a conventional negative binomial model are summarized in Table 2. For TX patients we found the same associations, again with no evidence of a significant contextual effect (Table 4).

Table 3.

Independent factors associated with the rate of SARS-CoV-2 positive cases in peritoneal dialysis patients

| Factors | Units | IRR | Z | p value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of positive cases in the dialysis centers’ province | 100 cases | 1.10 | 3.07 | 0.002 | 1.05–1.20 |

| Geographical latitude | 1° | 1.31 | 3.03 | 0.002 | 1.10–1.56 |

IRR incidence rate ratio, CI confidence interval

Table 4.

Independent factors associated with the rate of SARS-CoV-2 positive cases in transplant patients

| Factors | Units | IRR | Z | p value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of positive cases in the dialysis centers’ province | 100 cases | 1.30 | 8.32 | < 0.001 | 1.20–1.33 |

| Geographical latitude | 1° | 1.42 | 3.72 | < 0.001 | 1.18–1.70 |

IRR incidence rate ratio, CI confidence interval

Classification and regression tree

CART analysis substantially confirmed the predictors identified by the negative binomial model in the following order of importance: geographical latitude of the centers, cumulative incidence of SARS-CoV-2 positive cases in the general population, number of test-positive healthcare workers, and days elapsed since lockdown date. The maximally pruned model generated three rules (Fig. 3):

Fig. 3.

The decision tree shows the rules and split points to estimate the number of SARS-CoV-2 positive patients. The first row in each box shows the estimated number of cases, the second row the number of patients and the number of centers, the third row the percentage of cases covered

There were fewer than 1 SARS-CoV-2 positive HD patients per center when the cumulative incidence of positive cases in the province was below 229 per 100,000,

There were nearly 5 SARS-CoV-2 positive HD patients per center when the province cumulative incidence of positive cases was greater than or equal to 229 per 100,000 and there were fewer than 3 test-positive healthcare workers in the center,

There were nearly 15 SARS-CoV-2 positive HD patients per center when the cumulative incidence of positive cases in the province was greater than or equal to 229 per 100,000 and there were at least 3 test-positive healthcare workers in the center.

Multilevel modelling of case fatality

Admission to ICUs directly influenced the infection fatality proportion in SARS-CoV-2 positive HD patients (IRR 1.04; 95% CI 1.01–1.07), with no evidence of clustering in provinces or regions (χ2 = 0.30, p = 0.58). In PD and TX patients, fatality proportions in SARS-CoV-2 positive cases were associated with the number of positive cases in the province general population (IRR 1.003; 95% CI 1.002–1.004 for both TX and PD), again with no evidence of clustering in provinces or regions (χ2 = 0.02, p = 0.89. and χ2 = 0.04, p = 0.84, respectively).

Discussion

The SIN COVID-19 survey was conducted during the exponential phase of the pandemic in Italy. At that time, there were about 190,000 positive cases in Italy [7], and among them, 1093 were HD patients, 57 PD patients, and 218 kidney transplanted patients. The survey provided three main findings [1]: an almost tenfold higher proportion of SARS-CoV-2 positive subjects among RRT patients than in the general population (2.26 vs 0.3%) with a significant difference between HD, PD and TX patients (3.55%, 1.38% and 0.86%, respectively); a sizable variability among Italian regions with a north to south decreasing gradient; a higher case fatality rate among RRT patients than in the general population. Beyond these descriptive findings, we undertook an extended analysis cycle to identify the independent factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 spread and subsequent death.

We initially classified the factors associated with a higher likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 infection in RRT patients into three groups. First, factors shared with the general population, such as the center location and geographical latitude, the local cumulative incidence, and the length of lockdown period. Second, factors related to the center, such as the number of SARS-CoV-2 positive healthcare workers and the testing policy adopted. Third, neighborhood-level contextual factors, such as the organizational characteristics of the local health authorities.

Main factors and contextual effect

Through April 23rd, 2020, significant spread occurred following a north to south gradient in Italy, which is in keeping with a recent study that included eighty-eight countries reporting a statistically significant correlation between country latitude and number of COVID-19 cases [13]. The behavior of a seasonal respiratory virus, influenced by temperature, relative humidity, sunlight exposure [14], and air pollution [15] that is typical of the industrialized north of Italy [16–18], may in part explain such a pattern. On the other hand, the national lockdown measures effectively reduced infection spread, and resulted in a considerable drop in air pollution levels [19]. Hence, the latitude gradient may actually describe the effects of the lockdown on the dynamics of the virus spread. Indeed, the first cases were observed in the northern regions, where the infection rapidly spread, but the implementation of national lockdown measures directly affected the further southwards diffusion of the virus.

The number of positive cases observed in each center is associated with SARS-CoV-2 spread within the province general population. Such finding was somewhat expected because it reflects the prior probability that RRT patients will be infected before any other specific characteristics or condition is considered [20].

The days in lockdown acted as a protective factor and showed that quarantine measures effectively reduce the number of positive cases and infection spread in vulnerable patients. Interestingly, CART analysis identified a split rule for lockdown duration over 42 days, corresponding to three consecutive 14-day quarantines. This finding is indeed interesting because it suggests that shorter lockdown periods may not yield the expected benefit.

Factors related to the center

The greater the number of positive healthcare workers in a center, the higher the likelihood of there being SARS-CoV-2 positive patients. This does not necessarily mean that healthcare workers directly infect patients, but it is rather a proxy of the virus spread within the center. Notably, through CART analysis we found that a threshold of three infected healthcare workers can distinguish centers at low risk from those at high risk of infection spread when the cumulative incidence in the general population exceeds 230 cases per 100,000 inhabitants.

The test-all policy is associated with increased identification of SARS-CoV-2 positive cases, especially when it is adopted for both healthcare workers and patients. An unrestricted testing policy can effectively identify positive patients and contain the contagion, especially if the population positivity rate is on the rise in the surrounding territory [21] because it allows to identify asymptomatic subjects. It is however worth pointing out that the testing policy was modified in a large number of centers during the course of the epidemic. Initially, it was limited to symptomatic cases in most centers, but in keeping with the evolving literature and recommendations, tests were progressively extended to all patients and healthcare workers [22, 23]. Taken together, our findings strongly support the universal testing policy, advocated by countries that first faced the epidemic [24], which is still the topic of a lively debate in most European countries.

Contextual factors

Besides the independent effect of the fixed component of the model, our analysis provides evidence of a general contextual effect. On average, about 10% of the variation in the number of positive cases among centers is due to contextual differences. Hence, the inherent characteristics of geographical and administrative areas to which the centers belong (the context) explain a sizable part of the variation in positivity rates. The areas administered by Italian Local Health Authorities largely coincide with the province territory. Therefore, center policies and resource allocation within the same province is determined by the same Authority, which may explain the observed discrepancies among strategies and timeliness of interventions adopted throughout the country. For instance, in some provinces, lockdown dates, case isolation and management, and directives for containment measures and testing varied according to locally determined policies. Centralization of HD patients, common in China [25], was generally discouraged in Italy, but in some provinces, it was promoted and thus most likely influenced the center-specific rates.

We did not find evidence for a contextual effect among PD and TX patients and they seem to share the same risk factors of the population in the local area. Therefore, promoting home dialysis and kidney transplantation, when possible, is a valuable and effective containment measure in an epidemic context. In this setting, the contextual effect especially explores the set of the organizational characteristics that act beyond the fixed predictors of the outcome, but it does not identify each specific characteristic. Further analyses should be performed to establish the best organizational set-up.

Differences among RRT modalities

Unlike in-center HD patients, the proportion of SARS-CoV-2-positive PD and TX patients depends solely on the density of cases in the general population and the geographical latitude. It is highly conceivable that patients on home-based therapy, with a reduced schedule of center access and a higher likelihood of adherence to general prevention measures, might be less exposed to infection. In other words, these patients share the same degree of risk as the general population in each local area with no evidence for contextual effects.

Unfortunately, our survey data do not allow to investigate the increased immunosuppression-related vulnerability of TX patients. As stated in the survey questionnaire [1], we collected only information concerning the number of total and positive TX patients at the center level and not their individual data, such as transplant history, blood chemistry and immunosuppressive therapy. Nonetheless, it can be argued that any person, be they immunocompetent or immunosuppressed, who comes into contact with a formerly unknown virus has the same susceptibility to the infection, but the consequences are likely to be more severe in immunosuppressed organ transplant recipients [26]. The preliminary evidence reviewed by Thng [27] supports this hypothesis, although further prospective studies are needed to provide conclusive data.

Although RRT patients share the same risk of infection as the general population, only HD patients show additional risks associated with frequent contact with other possibly infected patients and healthcare workers. Clearly, our findings do not provide direct evidence of SARS-CoV-2 spread within the centers, but they do support this hypothesis. Unfortunately, a direct comparison with other groups of patients, regularly treated in hospital facilities for chronic diseases, is hardly feasible. No other patient population undergoes life-saving treatments delivered in the hospital for at least 12 h a week, in the same room, with the same fellow patients for months or years. Perhaps patients undergoing chemotherapy, radiation or physical therapy may somewhat resemble HD patients, but most of these treatments were either re-scheduled or halted during the critical phase of the pandemic [28, 29], consequently they cannot be considered a concurrent “control” group.

RRT patients and the general population

The higher proportion of SARS-CoV-2 infection in RRT patients as compared to the general population is an arguable issue. It is possible that the cumulative number of positive cases in the general population provided by national official statistics may have underestimated the actual case density at the time of the survey. As a matter of fact, the study by Lavezzo et al. [21] shows that the cumulative incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the population in one of the first villages in which the spread occurred in Italy was 2.6% and the preliminary data of a survey on SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in Italy [30] show that it was 2.5%. These findings seem numerically consistent with the cumulative incidence observed in RRT patients, but they must be interpreted cautiously because biological samples were collected in a small municipality in the north-eastern part of the country [21] and the seroprevalence was estimated to be less than 1% of the Italian population [30].

SARS-CoV-2-positive RRT patients show higher fatality rates than the general population [31], regardless of treatment and latitude. In HD patients, there is a link with the severity of the disease, expressed by number of ICU admissions, while for PD and TX the fatality rate is associated only with the positivity rate in the general population.

Action thresholds

Through CART analysis we identified a simple and interpretable set of rules to support decision making. The decision tree is a well validated supervised machine learning algorithm used for the classification and regression application. The pathway illustrated in the decision tree (Fig. 3) combines the major determinants of the within-center SARS-CoV-2 positivity rate. Namely, the incidence in the general population, the area of residence, and a proxy of virus spread inside the center (i.e. number of infected healthcare workers). Collectively, the decision rules offer a simple data-driven response tool to promptly act when the risk of infection for the patients becomes critical. Furthermore, our results can help policymakers and clinicians’ decisions-making during the current and future pandemics. Decisions are typically made in an evolving scenario and modeling becomes a valuable tool to provide guidance for establishing prevention strategies and infection control.

Strength and limitations

The main strength of the present survey is that it covers the majority of nephrology centers in a nation that was nearly overwhelmed by the COVID-19 pandemic, but it must be evaluated in the context of its limitations. The findings should be interpreted cautiously since the study database was based on aggregate data, thus making predictive inference somewhat imperfect, despite being based on large numbers. Furthermore, we were not able to stratify patients and outcomes by sex, age, and/or comorbidities because such data were not requested in the survey questionnaire.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest nationwide study on COVID-19 in RRT patients carried out to date [1, 22, 23], and the present analysis provides answers to the questions posed in the Introduction. The local number of SARS-CoV-2 positive cases in the general population is likely the most important determinant of the infected proportion among RRT patients, but for HD patients other factors strictly related to in-center models of care contribute to explain the higher frequency of positive cases. Namely, the number of infected healthcare workers, as a proxy of the virus spread within the dialysis center, and the testing policy adopted by the center, especially when it is broadened to include all patients and healthcare workers. These factors explain most of the heterogeneity observed in the descriptive study [1], while about 10% of the remaining variability can be attributed to the contextual organization of local healthcare programs. Finally, our study provides a novel set of decision rules based on thresholds derived from easily accessible and continuously monitored data such as the infected proportions in the local general population and within the dialysis center. If and when action thresholds are crossed, clinicians and policymakers may use them as an indication to quickly adopt more stringent containment measures beyond those suggested by current guidelines [31–33]. Future surveys should use a multi-wave longitudinal design and include more detailed information on both center-level and patient-level variables to explain a greater proportion of the variability.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mrs. Claudia Valletta and Mrs. Raffaella D’Arcangelo for their secretarial assistance and for contributing to the survey data collection. Members of Italian Society of Nephrology COVID-19 Research Group are: Italian Society of Nephrology Board of Directors: Giuliano Brunori, Piergiorgio Messa, Filippo Aucella, Manuela Bosco, Fabio Malberti, Marcora Mandreoli, Sandro Mazzaferro, Ezio Movilli, Giuseppe Quintaliani, Maura Ravera, Mario Salomone, Domenico Santoro. DialMap: Maurizio Postorino, Aurelio Limido. Participating Centers and Investigators by Region: Abruzzo: Chieti (M. Bonomini); Ortona-Guardagriele (A. Stingone); Lanciano Casoli Atessa (M. Maccarone); PO Atri (E. Di Loreto); Giulianova (L. Stacchiotti); Teramo (R. Malandra). Calabria: Area Ionica Soverato-Catanzaro (S. Chiarella); Lamezia Terme (F. D’Agostino); AOU Mater Domini—Catanzaro (G. Fuiano); PO Rossano—Rossano (CS) (L. Nicodemo); Osp. Annunziata Cosenza—Rete emodialitica territorial—Asp di Cosenza—Cosenza (R. Bonofiglio); Crotone (S. Greco); Reggio Calabra (F. Mallamaci); Scilla (E. Barreca); Melito Porto Salvo (C. Caserta); Taurianova (V. Bruzzese); Serra San Bruno-Soriano Calabro (D. Galati); Vibo Valentia (D. Tramontana). Campania: AO Moscati Avellino (M. Viscione); Dyalisis—Capodicasa (L. Chiuchiolo); Solofra (S. Tuccillo); Emodialisi Irpina Grottaminarda (M. Sepe); Osp. Ariano Irpino (F. Vitale); PO Santa Maria della Pietà—Nola (E. Ciriana); Dialisi Alra Irpinia Calitri (D. Santoro); AO G. Rummo—Benevento (V. Martignetti); AORN Caserta—Caserta (D. Caserta); Adem Marcianise—Marcianise (A. Stizzo); Helios Capua (A. Romano); SSD ASL Caserta—San Felice a Cancello (G. Iulianiello); Emodialisi Ludial—Castel Volturno (E. Cascone); Polisan San Nicola La Strada (P. Minicone); Emodialisi Cedial Santa Maria Capua Vetere (D. Chiricone); Emodialisi Luna Teano (G. Delgado); Vairano Patenora Caserta (A. Barbato); DIALCA SRL Caiazzo (S. Celentano); Cedial Sessa Aurunca (I. Molfino); PO Piedimonte Matese (S. Coppola); Iatreion Caserta (I. Raiola); Diam Nefrocenter—Maddaloni (M. Abategiovanni); Centro Atellano—Orta di Atella (CE) (S. Borrelli); Renart—Casagiove (C. Margherita); Nefrodial—Aversa (F. Bruno); Cedial Srl—San Cipriano D'Aversa (M. Ida); Alma Center—Mariglianella (E. Aliperti); CGA—Giugliano in Campania (D. Potito); CMO—Gragnano (G. Cuomo); Ambulatorio Emodialisi—Mugnano di Napoli (M. De Luca); Seironos—Sorrento (M. Merola); DIAL 3—Arzano (NA) (C. Botta); Nephrocare—Napoli (G. Garofalo); AO Cardarelli—Napoli (P. Alinei); Osp. Del Mare—Napoli (C. Paglionico); Dialgest—Casoria (M. Roano); Gruppo Dialisi Campano—Frattamaggiore (S. Vitale); Centro Delta—Boscoreale (R. Ierardi); CNP Frattamaggiore—Frattamaggiore (V. Fimiani); PO Santa Maria degli Incurabili Univ. Vanvitelli—Napoli (G. Conte); Ospedale Pellegrini—Napoli (G. Di Natale); Emodialisi Vesuviana—San Giuseppe Vesuviano (M. Romano); Gestione Servizi Emodialisi—Pozzuoli (V. Di Marino); Dial Cast Srl—Santa Maria La Carità (NA) (A. Scafarto); Villa S. Andrea—Napoli (S. Meccariello); AO Santobono Pausilipon—Napoli (C. Pecoraro); Cendial—Acerra (E. Di Stazio); Ischia (E. Di Meglio); Emodialisi EURODIAL—Napoli (A. Cuomo); Sean Srl—Aversa (B. Maresca); S. Pio X—Afragola (E. Rotaia); Nefrologia e Dialisi Univ. Vanvitelli—Napoli (G. Capasso); San Leonardo ASL NA3 SUD (M. Auricchio); D. Cotugno AORN dei Colli—Napoli (C. Pluvio); Kidney—Casavatore (L. Maddalena); CMM—Cava dei Tirreni (A. De Maio); AO Ruggi Mercato San Severino—Ospedale Ruggi Salerno (G. Palladino); PO Polla (F. Buono); Eboli (G. Gigliotti); Emilia Romagna: Imola (M. Mandreoli); Malpighi e S. Orsola—Bologna (E. Mancini, G. La Manna); Cona-Ferrara (A. Storari); Forlì-Cesena (G. Mosconi); Modena AUSL Carpi (G. Cappelli); Piacenza (R. Scarpioni); Reggio Emilia (M. Gregorini); Rimini (A. Rigotti); Friuli Venezia Giulia: Pordenone (W. Mancini); Trieste (F. Bianco); Santa Maria della Misericordia—Udine (G. Boscutti); San Daniele—Tolmezzo (G. Amici); Palmanova—Latisana—Gorizia—Monfalcone (M. Tosto); Lazio: Frosinone Ospedale—Anagni Osp FR (R Fini); Euronefro Frosinone (G. Pace); Sora Ospedale FR (A. Cioffi); Sant'Elisabetta Fiuggi (E. Boccia); Parodi Delfino Osp Colleferro (L. Di Lullo); NephroCare di Cassino (G. Di Zazzo); Cassino Ospedale (R. Simonelli); Alatri Ospedale (F. Bondatti); Centro dialisi Città di Aprilia (L. Miglio); Osp S Maria Goretti Latina—Cisterna di Latina (N. Rifici); Dono Svizzero Formia (A. Treglia); I.C.O.T.—Giomi (M. Muci); Centro Dialisi Monte San Biagio (G. Baldinelli); Only Dialysis Clinics (E. Rizzi); Centro Dialisi Italian Hospital Group Guidonia (M. Lonzi); Casa di Cura Ars Medica 2 (C. De Cicco); Nuova Clinica Annuziatella (F. Forte); Ospedale San Camillo Forlanini—San Camillo su Spallanzani (P. De Paolis); Policlinico Agostino Gemelli (G. Grandaliano); Casa di cura ARS Medica Dialisi 1 (C. Cuzziol); Centro Dialisi Geramed di Fiano Romano (V.M. Torre); Clinica Madonna delle Grazie Velletri (P. Sfregola); Medica San Carlo Frascati (V. Rossi); Santo Spirito in Sassia (G. Fabio); Ladispoli (A. Flammini); Policlinico Casilino (A. Filippini); Clinica Città di Roma (L. Onorato); Casa di Cura Privata Nostra Signora della Mercede (F. Vendola); Policlinico Tor Vergata (N. Di Daniela); Diagest (C. Alfarone); Casa di cura Nuova Villa Claudia A (L. Scabbia); Ospedale dei Castelli RM6 (M. Ferrazzano); Casa di Cura Villa dei Pini Gruppo ASA (B. Della Grotta); San Giovanni Addolorata (M. Gamberini); Casa di Cura Nuova ITOR A e B (L. Fazzari); Azienda Ospedaliera Sant'Andrea (P. Menè); Villa Nina Marino (A. Morgia); Regina Apostolorum—Albano Laziale (A. Catucci); S. Eugenio CTO S Caterina (R. Palumbo); Osp Palestrina Coniugi Barberini (M. Puliti); Casa di Cura Madonna della Fiducia (R. Marinelli); Osp S Giovanni Evangelista Tivoli/Subiaco (P. Polito); Capena—Bracciano—Civitavecchia San Paolo RM4 (F. Marrocco); AOU Policlinico Umberto I-UOD Dialisi/UOC Nefro (S. Morabito, R. Rocca); MIRA-NEPHRO SRL Ambulatorio di Nefrologia e Dialisi "Città di Ardea" (L. Nazzaro); NeproCare Cer. Lab. (R. Lavini); Villa Tiberia Hospital (V. Iamundo); Fatebenefratelli (M. Chiappini); Casa di cura Nuova Villa Claudia B (M. Casarci); PO asl3 OSTIA (M. Morosetti); Villa Sandra (S. Hassan); Villa Annamaria (C. Alfarone); Anzio-Nettuno (M. Ferrazzano); Clinica Guarnieri (G. Firmi); Ospedale Sandro Pertini/UDD DonBosco (M. Galliani); Ambulatorio Dialisi Nephrocare—Nephronet di Pomezia (M. Serraiocco); VT Osp Belcolle—S Teresa—Tarquinia-Civita Castellana (S. Feriozzi); ASL Rieti (W. Valentini); Liguria: ASL 3 Genova Osp. Villa Scassi e Arenzano (P. Sacco); San Martino—Genova (G. Garibotto); Sestri Levante (V. Cappelli); ASL 1 Imperia Sanremo Ventimiglia (C. Saffioti); ASL2 Savona Albenga Cairo Montenotte (M. Repetto); La Spezia; ASL 5 (D. Rolla); Lombardia: Policlinico San Marco—Zingonia (M. Lorenz); Seriate (L. Pedrini); Esine—Valcamonica (D. Polonioli); ASST Bergamo Ovest—Treviglio (E. Galli); Papa Giovanni XXIII—Bergamo (P. Ruggenenti); ASST Spedali Civili Brescia (F. Scolari—S. Bove); ASST del Garda Manerbio—Desenzano—Gavardo (E. Costantino); ASST Franciacorta (M. Bracchi); ASST Lariana Como—Como (S. Mangano); ASST Crema—Crema (G. Depetri); Cremona (F. Malberti); Lecco (V. La Milia); Lodi (M. Farina); Mantova (S. Zecchini); Garbagnate Milanese (R. Savino); Ospedale San Raffaele—Milano (M. Melandri); ASST Ovest Milanese—Legnano (C. Guastoni); ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo—Milano (M. Paparella); Ospedale Fatebenefratelli—Ospedale Sacco—Milano (M. Gallieni); Niguarda—Milano (E. Minetti); Cernusco sul Naviglio (S. Bisegna); Policlinico Milano (P. Messa); Vimercate (M. Righetti); Humanitas—Rozzano (S. Badalamenti); ASST Ovest Milanese—Magenta (C. Guastoni); ASST Nord Milano Bassini—Milano (E. Alberghini); IRCCS Multimedica—Sesto San Giovanni (S. Bertoli); Ospedale San Gerardo e Desio—Monza (P. Fabbrini); ASST Pavia—Voghera-Stradella-Varzi; (P. Albrizio); San Matteo—Pavia (T. Rampino); Sondrio (C. Colturi); Varese (G. Rombolà); ASST Valle Olona—Busto—Gallarate—Saronno (A. Lucatello); Marche: Fabriano (E. Guerrini); Ancona (A. Ranghino); Ancona INRCA (F. Lenci); Senigallia (E. Fanciulli); Jesi (S. Santarelli); Ascoli Piceno e San Benedetto del T. (C. Damiani); Fermo-Amandola (D. Garofalo); Macerata (F. Sopranzi); Civitanova Marche-Recanati (A. Santoferrara); Pesaro-Fano (M. Di Luca); Urbino (P. Galiotta); Molise: Campobasso (M. Brigante); Piemonte: Alessandria (M. Manganaro); Asti (S. Maffei); Biella (I. Berto); ASL CN1 (L. Besso); Alba (G. Viglino); AO S. Croce e Carle—Cuneo (L. Besso); Borgomanero (S. Cusinato); Novara (D. Chiarinotti); ASL TO3 Rivoli Pinerolo (f. Chiappero); AOU San Luigi—Orbassano (G. Tognarelli); OIRM Dialisi Pediatrica—Torino (B. Gianoglio); ASL TO5—Chieri (M. Salomone); Ospedale Giovanni Bosco—Torino (G. Forneris); AOU Città della Salute e della Scienza—Torino (L. Biancone); ASL TO4 (S. Savoldi); AO Ordine Mauriziano—Torino (C. Vitale); Torino Martini (R. Boero); Vercelli (O. Filiberti); ASL VCO (M. Borzumati); Puglia: Policlinico Bari (L. Gesualdo); Osp. Miulli—Acquaviva (BA) (C. Lomonte); CAD Monopoli—Putignano—Conversano—Gioia del Colle (G. Gernone); Ospedale della Murgia Altamura (G. Pallotta); ASL BT—Bisceglie (S. Di Paolo); ASL Brindisi (L. Vernaglione); Cerignola-Manfredonia-Accadia (A. Specchio); Policlinico Foggia (G. Stallone); San Severo e Sannicandro G.co (R. Dell'Aquila); San Giovanni Rotondo (F. Aucella); Galatina (G. Sandri); Scorrano-Poggiardo (F. Russo); PO V. Fazzi—Lecce (M. Napoli); Martina Franca (A. Marangi); SS Annunziata—Taranto (L. Morrone); Manduria/Grottaglie (C. Di Stratis); Sardegna: Dialisi San Salvatore—Cagliari (A. Fresu); Kinetika—Quartu Sant'Elena (CA) (F. Cicu); ASSL Cagliari (S. Murtas); Casa di cura—Decimomannu (O. Manca); Cagliari Brotzu (A. Pani); Carbonia (M. Pilloni); Carbonia—Iglesias—CAD Buggerru—CAL Carloforte (R. Pistis); ASSL Sanluri—San Gavino (M. Cadoni); Lanusei (B. Contu); Nuoro (F. Logias); PO San Martino—Oristano (R. Ivaldi); Tempio Pausania (S. Fancello); Ospedale ASSL Sassari (M. Cossu); PO Merlo—La Maddalena (G. Lepori); Arzachena—Olbia (G. Lepori); Sicilia: Diaverum Sciacca—Sciacca (S. Vittoria); BIOS-MEDIC—S.M. Belice (E. Battiati); Aurora—Agrigento (M. Arnone); Canicattì—Canicattì (M. Romè); Centro Dialisi—Lampedusa e Linosa (A. Barbera); Ospedale San Giovanni Di Dio—Agrigento (A. Granata); Dialisi Aspert—Bivona (AG) (G. Collura); Centro Emodialisi Ippocrate—Agrigento (C. Lo Dico); AO Giovanni Paolo II—Sciacca (G. Pugliese); CAL Dialisi PO Mussomeli—Caltanissetta (E. Di Natale); Ambulatorio Nisseno di Emodialiei—Caltanissetta (G. Rizzari); Nefrologico Etneo (L. Cottone); CCMC Centro Catanese di Medicina e Chirurgia (N. Longo); Osp. Santa Marta e Santa Venera—Acireale (G. Battaglia); AO San Marco—Catania (C. Marcantoni); Ospedale Gravina Santo Pietro—Caltagirone (G. Giannetto); Ambulatorio Klotho Srl (G. Tumino); Etna Dialisi—Randazzo (CT) (F. Randazzo); CEB SRL—Belpasso (L. Bellissimo); Ambulatorio Azzurra—Catania (F. Lo Faro); Diaverum del Principe—Catania (F. Grippaldi); ARNAS Garibaldi Catania—Catania (S. Urso); Diaverum Paternò—Paternò (CT) (G. Quattrone); Ospedale Chiello—Piazza Armerina (I. Todaro); PO Umberto I Enna—Enna (D. Vincenzo); Diaverum—Nissoria (A. Murgo); Diaverum Barcellona P.G.—Barcellona P.G. (M. Masuzzo); Centro Dialisi Omega—Messina (A. Pisacane); AO Papardo—Messina (P. Monardo); Policlinico Messina (D. Santoro); Lipari—PO Fogliani—Milazzo (M. Pontorierro); Santo Stefano di Camastra (C. Quari); San Filippo Dial Center—Brolo (A. Bauro); Nefrologia Pediatrica Messina (R. R.Chimenz); Emodialisi Sparviero—Taormina (D. Alfio); PO Barone Matteo—Patti (F. Girasole); ADTR Palermo—Palermo (A. Lo Cascio); Centro Siciliano di Nefr. E Dialisi—Cefalù (A. Caviglia); Centro Medico Nefrologico—Termini Imerese (F. Tornese); Petralia Soprana—Petralia Soprana (F. Sirna); DIBA SRL (C. Altieri); ARNAS Civico Palermo—Palermo (R. Cusumano); Cepidial srl (V. Saveriano); M. Malpighi—Partinico (A. La Corte); Centro Emodialitico Meridionale—Palermo (G. Locascio); Nefrologia Pediatrica ARNAS Civico—Palermo (U. Rotolo); Nefrologia e dialisi srl (M. Romè); ASP 7 Ragusa—Ragusa (S. Musso); Dialisi San Luca—Lentini (SR) (L. Risuglia); Diaverum Brucoli—Brucoli (G. Blanco); Nefral—Noto (G. Minardo); Diaverum—Lentini (S.Castellino); Sirnephros—Siracusa (Z.Zappulla); PO Avola (S. Randone); Dialisi Aretusea—Siracusa (M. Di Francesca); Sirnephros—Pachino (C. C. Cassetti); UOSD Emodialisi—Marsala (G. Oddo); PO Castelvetrano—Castelvetrano (G. Buscaino); Emodialisi Mucaria—Alcamo (F. Mucaria); ASP Trapani—Trapani (V. Ignazio Barraco); Emodialisi Mucaria—Alcamo (A. Di Martino); Emodialisi Mucaria—Valderice (F. Mucaria); Diaverum Marsala (D. Rallo); Toscana: Ospedale San Miniato—Empoli (L. Dani); Careggi Firenze (G. Campolo); Firenze Santa Maria Nuova—Firenze (F. Manescalchi); SOC Nefrologia e Dialisi Firenze 2—Firenze (M. Biagini); Lucca-Barga (M. Agate); Versilia (V. Panichi); Ospedale Apuane—Massa Carrara (A. Casani); Massa Marittima (L. Traversari); AOU Senese—Siena (G. Garosi); Trentino Alto Adige: Trento (G. Brunori); Bolzano (M. Tabbì); Umbria: Assisi—Castiglione del Lago (A. Selvi); Orvieto—Amelia (L. Cencioni); AO Terni (R. Fagugli); AO Perugia (F. Timio); Città di Castello (A. Leveque); Valle d’Aosta: Aosta (M. Manes); Veneto: Piove di Sacco (G. Mennella); Padova (L. Calò); Rovigo Adria Trecenta (F. Fiorini); Castelfranco Veneto (C Abaterusso); Conegliano (P. Calzavara); Treviso (M. Nordio); Ospedale dell'Angelo—Mestre—Venezia—Dolo e Mirano (G. Meneghel); AULSS4 Veneto Orientale (C. Bonesso); Borgo Trento e Borgo Roma—Verona (G. Gambaro); San Bonifacio (L. Gammaro); Legnago (C. Rugiu); Bassano del Grappa (R. Dell'Aquila); Santorso-Bassano (R. Dell'Aquila); Ospedale San Bortolo—Vicenza (C. Ronco); Villafranca e Caprino (C. Rugiu).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Statement

All data used in this study were collected anonymously and in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and regional research committees, with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study did not require formal individual consent because it was conducted on aggregate data.

Footnotes

The members of Italian Society of Nephrology COVID-19 Research Group are listed in acknowledgements.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Maurizio Nordio, Gianpaolo Reboldi and Anteo Di Napoli have contributed equally to the work.

Contributor Information

Giuliano Brunori, Email: giuliano.brunori@apss.tn.it.

the Italian Society of Nephrology COVID-19 Research Group:

Giuliano Brunori, Piergiorgio Messa, Filippo Aucella, Manuela Bosco, Fabio Malberti, Marcora Mandreoli, Sandro Mazzaferro, Ezio Movilli, Giuseppe Quintaliani, Maura Ravera, Mario Salomone, Domenico Santoro, Maurizio Aurelio PostorinoLimido, M. Bonomini, A. Stingone, M. Maccarone, E. Di Loreto, L. Stacchiotti, R. Malandra, S. Chiarella, F. D’Agostino, G. Fuiano, L. Nicodemo, R. Bonofiglio, S. Greco, F. Mallamaci, E. Barreca, C. Caserta, V. Bruzzese, D. Galati, D. Tramontana, M. Viscione, L. Chiuchiolo, S. Tuccillo, M. Sepe, F. Vitale, E. Ciriana, D. Santoro, V. Martignetti, D. Caserta, A. Stizzo, A. Romano, G. Iulianiello, E. Cascone, P. Minicone, D. Chiricone, G. Delgado, A. Barbato, S. Celentano, I. Molfino, S. Coppola, I. Raiola, M. Abategiovanni, S. Borrelli, C. Margherita, F. Bruno, M. Ida, E. Aliperti, D. Potito, G. Cuomo, M. De Luca, M. Merola, C. Botta, G. Garofalo, P. Alinei, C. Paglionico, M. Roano, S. Vitale, R. Ierardi, V. Fimiani, G. Conte, G. Di Natale, M. Romano, V. Di Marino, A. Scafarto, S. Meccariello, C. Pecoraro, E. Di Stazio, E. Di Meglio, A. Cuomo, B. Maresca, E. Rotaia, G. Capasso, M. Auricchio, C. Pluvio, L. Maddalena, A. De Maio, G. Palladino, F. Buono, G. Gigliotti, M. Mandreoli, E. Mancini, G. La Manna, A. Storari, G. Mosconi, G. Cappelli, R. Scarpioni, M. Gregorini, A. Rigotti, W. Mancini, F. Bianco, G. Boscutti, G. Amici, M. Tosto, R. Fini, G. Pace, A. Cioffi, E. Boccia, L. Di Lullo, G. Di Zazzo, R. Simonelli, F. Bondatti, L. Miglio, N. Rifici, A. Treglia, M. Muci, G. Baldinelli, E. Rizzi, M. Lonzi, C. De Cicco, F. Forte, P. De Paolis, G. Grandaliano, C. Cuzziol, V. M. Torre, P. Sfregola, V. Rossi, G. Fabio, A. Flammini, A. Filippini, L. Onorato, F. Vendola, N. Di Daniela, C. Alfarone, L. Scabbia, M. Ferrazzano, B. Della Grotta, M. Gamberini, L. Fazzari, P. Menè, A. Morgia, A. Catucci, R. Palumbo, M. Puliti, R. Marinelli, P. Polito, F. Marrocco, S. Morabito, R. Rocca, L. Nazzaro, R. Lavini, V. Iamundo, M. Chiappini, M. Casarci, M. Morosetti, S. Hassan, C. Alfarone, M. Ferrazzano, G. Firmi, M. Galliani, M. Serraiocco, S. Feriozzi, W. Valentini, P. Sacco, G. Garibotto, V. Cappelli, C. Saffioti, M. Repetto, D. Rolla, M. Lorenz, L. Pedrini, D. Polonioli, E. Galli, P. Ruggenenti, F. Scolari, S. Bove, E. Costantino, M. Bracchi, S. Mangano, G. Depetri, F. Malberti, V. La Milia, M. Farina, S. Zecchini, R. Savino, M. Melandri, C. Guastoni, M. Paparella, M. Gallieni, E. Minetti, S. Bisegna, P. Messa, M. Righetti, S. Badalamenti, C. Guastoni, E. Alberghini, S. Bertoli, P. Fabbrini, P. Albrizio, T. Rampino, C. Colturi, G. Rombolà, A. Lucatello, E. Guerrini, A. Ranghino, F. Lenci, E. Fanciulli, S. Santarelli, C. Damiani, D. Garofalo, F. Sopranzi, A. Santoferrara, M. Di Luca, P. Galiotta, M. Brigante, M. Manganaro, S. Maffei, I. Berto, L. Besso, G. Viglino, L. Besso, S. Cusinato, D. F. ChiarinottiChiappero, G. Tognarelli, B. Gianoglio, M. Salomone, G. Forneris, L. Biancone, S. Savoldi, C. Vitale, R. Boero, O. Filiberti, M. Borzumati, L. Gesualdo, C. Lomonte, G. Gernone, G. Pallotta, S. Di Paolo, L. Vernaglione, A. Specchio, G. Stallone, R. Dell’Aquila, F. Aucella, G. Sandri, F. Russo, M. Napoli, A. Marangi, L. Morrone, C. Di Stratis, A. Fresu, F. Cicu, S. Murtas, O. Manca, A. Pani, M. Pilloni, R. Pistis, M. Cadoni, B. Contu, F. Logias, R. Ivaldi, S. Fancello, M. Cossu, G. Lepori, G. Lepori, S. Vittoria, E. Battiati, M. Arnone, M. Romè, A. Barbera, A. Granata, G. Collura, C. Lo Dico, G. Pugliese, E. Di Natale, G. Rizzari, L. Cottone, N. Longo, G. Battaglia, C. Marcantoni, G. Giannetto, G. Tumino, F. Randazzo, L. Bellissimo, F. Lo Faro, F. Grippaldi, S. Urso, G. Quattrone, I. Todaro, D. Vincenzo, A. Murgo, M. Masuzzo, A. Pisacane, P. Monardo, D. Santoro, M. Pontorierro, C. Quari, A. Bauro, R. R. Chimenz, D. Alfio, F. Girasole, A. Lo Cascio, A. Caviglia, F. Tornese, F. Sirna, C. Altieri, R. Cusumano, V. Saveriano, A. La Corte, G. Locascio, U. Rotolo, M. Romè, S. Musso, L. Risuglia, G. Blanco, G. Minardo, S. Castellino, Z. Zappulla, S. Randone, M. Di Francesca, C. C. Cassetti, G. Oddo, G. Buscaino, F. Mucaria, V. Ignazio Barraco, A. Di Martino, F. Mucaria, D. Rallo, L. Dani, G. Campolo, F. Manescalchi, M. Biagini, M. Agate, V. Panichi, A. Casani, L. Traversari, G. Garosi, G. Brunori, M. Tabbì, A. Selvi, L. Cencioni, R. Fagugli, F. Timio, A. Leveque, M. Manes, G. Mennella, L. Calò, F. Fiorini, C. Abaterusso, P. Calzavara, M. Nordio, G. Meneghel, C. Bonesso, G. Gambaro, L. Gammaro, C. Rugiu, R. Dell’Aquila, R. Dell’Aquila, C. Ronco, and C. Rugiu

References

- 1.Quintaliani G, Reboldi GP, Di Napoli A, Nordio M, Limido A, Aucella F, Messa PG, Brunori G, on behalf of the Italian Society of Nephrology COVID-19 Research Group Exposure to novel coronavirus in patients on renal replacement therapy during the exponential phase of COVID-19 pandemic: survey of the Italian Society of Nephrology. J Nephrol. 2020;33:725–736. doi: 10.1007/s40620-020-00794-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang H. Maintenance hemodialysis and COVID-19: saving lives with caution, care, and courage. Kidney Med. 2020;2:365–366. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2020.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naicker S, Yang CW, Hwang SJ, Liu BC, ChenJH JV. The novel coronavirus 2019 epidemic and kidneys. Kidney Int. 2020;97:824–828. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rombolà G, Heidempergher M, Pedrini L, Farina M, Aucella F, Messa P, Brunori G. Practical indications for the preventions and management of SARS-CoV-2 in ambulatory dialysis patients: lessons from the first phase of the epidemics in Lombardy. J Nephrol. 2020;33:193–196. doi: 10.1007/s40620-020-00727-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basile C, Combe C, Pizzarelli F, Covic A, Davenport A, Kanbay M, Kirmizis D, Schneditz D, van der Sande F, Mitra S, on behalf of the EUDIAL Working Group of ERA-EDTA Recommendations for the prevention, mitigation and containment of the emerging SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic in haemodialysis centers. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35:737–741. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decreto del Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri 9 marzo 2020. Ulteriori disposizioni attuative del decreto-legge 23 febbraio 2020, n. 6, recante misure urgenti in materia di contenimento e gestione dell'emergenza epidemiologica da COVID-19, applicabili sull'intero territorio nazionale. (20A01558) (GU Serie Generale n.62 del 09-03-2020)

- 7.Istituto Superiore di Sanità (2020) Epidemia COVID-19, Aggiornamento nazionale: 23 aprile 2020. https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/bollettino/Bollettino-sorveglianza-integrata-COVID-19_28-aprile-2020.pdf. Accessed 20 August 2020

- 8.Austin PC, Stryhn H, Leckie G, Merlo J. Measures of clustering and heterogeneity in multilevel Poisson regression analyses of rates/count data. Stat Med. 2018;37:572–589. doi: 10.1002/sim.7532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Izenman AJ (2013) Recursive Partitioning and Tree-Based Methods. In: Modern Multivariate Statistical Techniques. Springer, New York, NY. 10.1007/978-0-387-78189-1_9

- 10.Therneau TM, Atkinson EJ (2019) An introduction to recursive partitioning using RPART routines. R package. https://CRAN.R-roject.org/package=rpart. Accessed 28 Aug 2020

- 11.Milborrow S (2016) rpart.plot: Plot rpart Models. An enhanced version of plot.rpart. R Package. http://www.milbo.org/rpart-plot/prp.pdf. Accessed 28 Aug 2020

- 12.Istituto Nazionale di Statistica—Istat (2020) Confini delle unità amministrative a fini statistici al 1° gennaio 2020. https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/222527. Accessed 23 Apr 2020

- 13.Whittemore PB. COVID-19 fatalities, latitude, sunlight, and vitamin D. Am J Infect Control. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.06.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sajadi MM, Habibzadeh P, Vintzileos A, Shokouhi S, Miralles-Wilhelm F, Amoroso A. Temperature, humidity, and latitude analysis to estimate potential spread and seasonality of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e2011834. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.11834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bashir MF, Ma BJ, Bilal KB, Bashir MA, Farooq TH, Iqbal N, Bashir M. Correlation between environmental pollution indicators and COVID-19 pandemic: a brief study in Californian context. Environ Res. 2020;187:109652. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fattorini D, Regoli F. Role of the chronic air pollution levels in the Covid-19 outbreak risk in Italy. Environ Pollut. 2020;264:114732. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coker ES, Cavalli L, Fabrizi E, Guastella G, Lippo E, Parisi ML, Pontarollo N, Rizzati M, Varacca A, Vergalli S. The effects of air pollution on COVID-19 related mortality in Northern Italy. Environ Resour Econ (Dordr) 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10640-020-00486-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Filippini T, Rothman KJ, Goffi A, Ferrari F, Maffeis G, Orsini N, Vinceti M. Satellite-detected tropospheric nitrogen dioxide and spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Northern Italy. Sci Total Environ. 2020;739:140278. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140278). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muhammad S, Long X, Salman M. COVID-19 pandemic and environmental pollution: a blessing in disguise? Sci Total Environ. 2020;728:138820. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gatto M, Bertuzzo E, Mari L, Miccoli S, Carraro L, Casagrandi R, Rinaldo A. Spread and dynamics of the COVID-19 epidemic in Italy: effects of emergency containment measures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(19):10484–10491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004978117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavezzo E, Franchin E, Ciavarella C, et al. Suppression of a SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in the Italian municipality of Vo’. Nature. 2020;584:425–429. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2488-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sánchez-Álvareza JE, Fontánb MP, Martínc CJ, Pelícanod MB, Reinae CJC, Prieto AMS, Melilli E, Barriosh MC, Herasi MM, del Pino y Pinoj MD, Status of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients on renal replacement therapy. Report of the COVID-19 Registry of the Spanish Society of Nephrology (SEN) Nefrologia. 2020;40:272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.nefro.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corbett RW, Blakey S, Nitsch D, Loucaidou M, McLean A, Duncan N, Ashby RD, for the West London Renal and Transplant Centre Epidemiology of COVID-19 in an Urban Dialysis Center. JASN. 2020;31:1815–1823. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020040534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beeching NJ, Fletcher TE, Beadsworth MBJ. Covid-19: testing times. BMJ. 2020;369:m1403. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang CJ, Ng CY, Brook RH. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan. Big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing. JAMA. 2020;323:1341–1342. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fung M, Babik JM. COVID-19 in immunocompromised hosts: what we know so far. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thng ZX, De Smet MD, Lee CS, Gupta V, Smith JR, McCluskey PJ, et al. COVID-19 and immunosuppression: a review of current clinical experiences and implications for ophthalmology patients taking immunosuppressive drugs. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-316586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu S, Zheng D, Liu T, et al. Radiation therapy care during a major outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020;5:531–533. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marschner S, Corradini S, Rauch J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 prevalence in an asymptomatic cancer cohort—results consequences for clinical routine. Radiat Oncol. 2020;15:165–174. doi: 10.1186/s13014-020-01609-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Istituto Nazionale di Statistica—ISTAT (2020) Primi risultati dell’indagine di sieroprevalenza sul SARS-CoV-2 https://www.istat.it/it/files/2020/08/ReportPrimiRisultatiIndagineSiero.pdf Accessed 19 Oct 2020

- 31.World Health Organization (2020) Strategic preparedness and response plan for the novel coronavirus. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/strategic-preparedness-and-response-plan-for-the-new-coronavirus. Accessed 20 Aug 2020

- 32.The International Society of Nephrology (2020) COVID-19 Recommendations. https://www.theisn.org/initiatives/covid-19/recommendations/. Accessed 20 Oct 2020

- 33.American Society of Nephrology (2020) COVID-19 Toolkit for Nephrology Clinicians: Preparing for a Surge. https://www.asn-online.org/covid-19/toolkit. Accessed 28 Oct 2020