Abstract

Objective

While the second wave of COVID-19 has started in Europe, data are still missing on the consequences of the first one for patients with cancer. The aim of our study was to learn more about the experiences of German patients and staff in the oncology services.

Materials and methods

An anonymous online survey was conducted among cancer patients and their therapists (physicians, medical staff, psychologists, spiritual care givers) in Germany between April and May 2020 asking about burden, fears, and perceived changes in German oncology service system. Besides answer frequencies of different stakeholders, uni- and multivariate analyses were performed for selected items to identify areas of high impact.

Results

In total 752 participants were included. All groups have identified high mental burden as central problem. A majority was confused about varying information policies and strategies against the pandemic. Patient reported restricted visits, isolation and delay of treatment as central fears and problems. The majority of fears could be coped by the health care workers. The patients describe processes at the oncology services during the first wave. Personal experiences with COVID-19 have had no influence on the felt burden of the patients. Physicians, medical staff, psychologists and spiritual care givers were extremely stressed but repressed their own burden. They await financial, physical and mental problems for their own future.

Conclusions

The presented personal views and experiences allow focusing the discussions about heath care systems during the on-going pandemic. Support for health care workers, as much routine as possible in oncology services, and transparency in information will be the keys for good management in futural situations of crisis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00432-020-03492-4.

Keywords: Oncology services, COVID-19 pandemic, Mental burden, Patients, Health care workers

Introduction

COVID-19 pandemic has shifted the focus of society and health care system on infection-related problems. The on-going pandemic seems to be unique within the last decades resulting in political decisions to lockdown the whole Western world during the first wave in spring 2020. This lockdown seems to result in a big transformation process of the total society and its long-time consequences are not visible at the moment (Deutscher Ethikrat 2020). This imponderability applies to all fields of social and health care system, in particular also to cancer care. Chronic illnesses don’t make a corona-break. This was the slogan of the official organ of German Medical Council (Korzilius und Osterloh 2020). While the official statistics point to sufficient resources, capacities, and fully running supply for cancer patients at university hospitals during COVID-19, only few real world data exist on cancer care in other settings.

While all professionals in the health care system struggled to not only provide resources for the care of patients infected with COVID-19, they all also did their best to not to reduce care for patients with other acute or chronic diseases. Yet, data already show that there were less patients treated with acute myocardial infarction or stroke, and that those coming to hospitals were in much more advanced states (Korzilius und Osterloh 2020). The discussion is ongoing whether this was due to a fear of getting infected in the hospital or whether other drawbacks—for example the strict prohibition of visits from members of the family was the decisive reason (Hübner 2020).

As pandemics may occur at any time and even the Corona pandemic is still ongoing, we need an analysis and thorough reflections of this event on all meta-levels of social life. To improve patient care in the second wave and to prepare for other outbreaks, we have to assess the individual impressions, experiences, fears and views of participants during the COVID-19-pandemic. Besides numbers and statistics, the personal view of acting people is similar important to evaluate the impact of the pandemic and the lockdown on human relationships and behavior among professionals as well as in relation to the patients who suddenly faced two potentially fatal diseases: cancer and Corona. Accordingly, the perspective of all actors is necessary to complete the picture of experiences/emotions in the pandemic situation.

Only by a thorough analysis, we will be prepared for the next infection wave or other crisis with restricted resources.

This paper is dedicated to this personal view of participants. We summarize the data of four surveys among patients, physicians, spiritual care givers, medical staff and psychologists in Germany during the days of lockdown. Nearly 750 participants have completed our questionnaires and allowed us to get an impression of their thoughts and feelings during this high emotional situation. The surveys were initiated and organized by the Working Group “Prevention and Integrative Oncology” (PRIO) with in the German Cancer Society in April 2020. In May 2020 we were able to report first results of this flash interview project (Büntzel et al. 2020). Now we present the complete data of the PRIO survey program in Germany during the first pandemic wave in spring 2020.

Materials and methods

Between 16–04–2020 and 15–05–2020 we performed three online surveys for cancer patients, physicians, and other care givers to evaluate the situation of oncology services during COVID-19 pandemic. The 4th online survey among psychooncologists and spiritual care givers was started at May 15 and finished after 4 weeks. The online surveys were created and collected via the public system/website of SoSci Survey (https://www.soscisurvey.de/).

Methodological remarks

All used questionnaires were anonymous and followed a similar structure. Personal baseline data were origin, type of tumor, tumor situation, treatment situation for patients. Additionally, we asked health care professionals to give us data about their work. The actual situation was evaluated by 2–3 items—physical and mental health, on-going treatments, burden, infection. Anticipated developments were discussed in detail for physical and mental consequences for oncology services and daily life. Table 1 summarizes the content of items and shows that we so became able to describe and compare answers of different stakeholders on each topic. The questionnaires are available as Supplementary material 1–4.

Table 1.

Structure of the questionnaires

| Topic | Patients | Doctors | Nurses | PSO/SCG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Federal state (home) | X | X | X | X |

| Actual tumor disease | X | |||

| Tumor localization | X | |||

| Professional COVID-19-contact | X | X | X | |

| Patient-related problems | ||||

| Information policy | X | X | X | X |

| Patients need for information | X | X | X | |

| Actual mental burden of patients | X | X | X | X |

| Expected mental and/or physical consequences | X | |||

| Delays in cancer services | X | X | X | X |

| Concerns about cancer therapies | X | X | ||

| Discussions to stop cancer therapy | X | X | ||

| Visit ban | X | X | X | X |

| Professional’s related problems | ||||

| Actual mental burden | X | X | X | |

| Financial fears | X | X | X | |

| Expected mental and/or physical consequences | X | X | X | |

| Fear to become infected by Covid-19 | X | X | X | |

| Own stress coping | X | X | X | |

| Stress coping of the others | X | X | ||

| Specific topics | ||||

| Social distancing | X | |||

Metric data were only assessed concerning Federal State (physician, medical staff, patients, psychologists), cancer entity (patients) and whether physicians/staff/psychologists were (1) mainly involved in care of in- and/or out-patients and (2) in contact with patients suffering from COVID-19. Scale questions were mainly used to assess the impact and consequences of the German measures of COVID-19 management for patients (physicians’, medical staffs’, and patients’ questionnaire). In four cases simple- or multiple-choice questions were used to determine the influence of COVID-19 on the treating physician’s life (physicians’ questionnaire). One question used the allegory of a thermometer to capture the current emotional status of the treating medical staff (both questionnaires, scale question). The online tool http://soscisurvey.de was used to create the complete survey program and distribute the online questionnaire.

Psychologists/spiritual care givers had the possibility to add free answers for selected items.

Invitation to participate were distributed via link among the professional members of the PRIO working group of the German Cancer Society and the members of self-help groups organized within the German self-help association for cancer patients (Haus der Krebsselbsthilfe Bonn e.V.).

The data were downloaded as a MS Excel table from the website of SoSci Survey on May 18. This program was used for further calculations.

Further statistical analysis

We performed three additional analyses to find impact factors how people experience the Covd-19 pandemic in Germany.

Patients with active cancer disease or cancer survivors. We compared both groups to get information of the cancer-disease-burden on the experience of pandemic.

Contact with COVID-19 patients or their relatives. Using the filter function of MS Excel, we performed for selected items a sub-analysis to explore the impact on COVID-19 experience. Our filtering variable was the Federal state where participants live. Region with higher infection rates were compared with regions under the mean infection rate on May 15, 2020 (Robert-Koch-Institut 2020).

To compare the answers of resulting groups in each sub-analysis, we have used Mantel-Haenssel-Shi-square-tests for independent groups. We defined the significant level for differences at p values for p < 0.05.

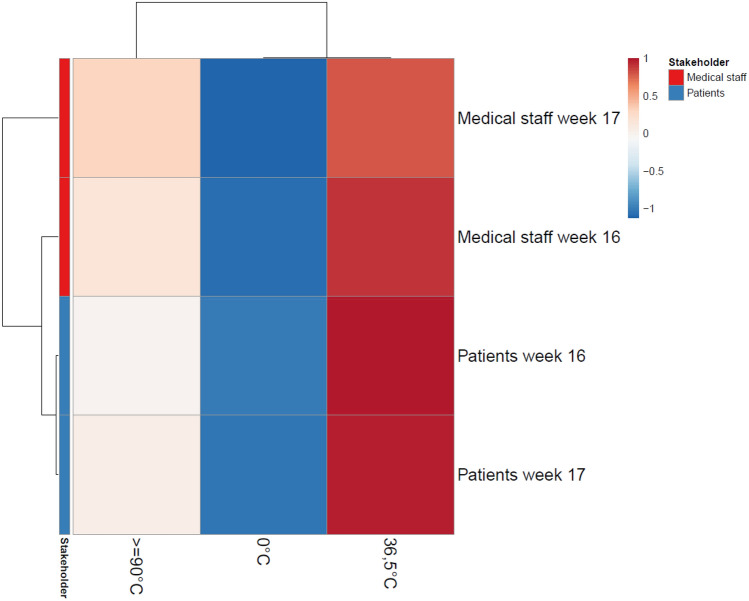

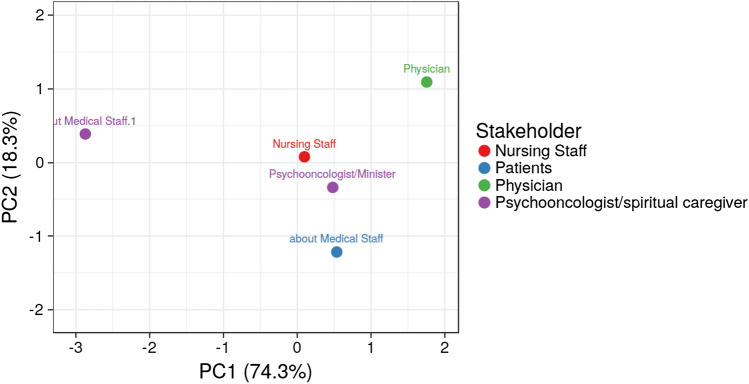

The distress thermometer and the duration of Lockdown. We used the metaphor of a thermometer to visualize distress. Participants had the option to choose 0° (“cool”), 36.5 °C (“normal”), 90 °C (“tense”) or 110° (“burned”). Our third filter is the date of participation. We compare the distress thermometers of all participants at week 16 and at week 17 of the year 2020. Shorter lockdown experience is compared to longer. To get enough data pools, we summarize physicians and other care givers. To visualize the development of distress we performed a principal component analysis (PCA) and calculated a heat map. The used clustering software is ClustVis—a free available tool at https://biit.cs.ut.ee/clustvis/ (Metsalu und Vilo 2015).

For analyzing free text answers of the psycho-oncologists’ and spiritual caregivers’ questionnaire we (1) took the free text answers and put them through a free online word counting program (http://www.pooq.org/wortzahl/index.php). We then (2) manually screened all entries and used the program to exclude not relevant words. The remaining words were (3) clustered according to different topics. Clusters were “talk/communication”, “isolation”, “distance”, “burden”, “facial expressions”, “fears”, “shortage”, “uncertainty”, “resources”, “therapy”, “no visits”. Subsequently, (4) the open access program “wordle” (www.wordle.net) was used for drawing a word cloud.

Ethics vote: The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University Hospital of Jena (No. 2020-1768-Bef).

Results

Patients’ survey

Four hundred thirty-three participants completed the questionnaire. The majority has participated during the first 2 weeks.

The median age of our participants was between 50 and 60 years. Figure 1 summarizes the distribution according the age. 218/433 participant have not given a specific information about the location of their cancer disease. The cancer types most often reported were head and neck cancer (n = 92) and breast cancer (n = 69). One hundred and thirty-eight patients were still under treatment and 227 were survivors. Another 15 patients were in palliative situation. 53 have not reported their actual tumor status. One hundred and twenty-four patients settled in federal states with higher COVID-19 infection rates (Bavaria, Baden Wurttenberg, Hamburg, Saarland). The remaining 309 patients lived in regions with relatively low infection rates (under German average). 121 participated during their stay at an oncology department and 312 participants answered from their home.

Fig. 1.

Participating patients’ age (n = 433, 79 n. a.)

Impact on daily life. During the lockdown 239/355 (67.3%) persons felt strongly or very strongly restricted by the official regulations. 247/357 (69.2%) participants reported to be confused by the public discussion and information about COVID-19.

Mental stress for patients. At the time of participation, already 150/350 (42.9%) patients have felt strong or very strong mental stress with this actual pandemic situation. Further 119 reported about beginning mental stress, only 74 participants have not seen any impact of their mind by the pandemic.

Physical consequences for patients. During the lockdown 127/342 (37.1%) participating patients have already registered minor physical well-being. 153/353 (43.3%) awaited a further negative development. Nevertheless, a big majority (318/357, 89.1%) was satisfied with their own possibilities to stay active during the phase of lockdown.

Anti-cancer therapies. Patients were asked to report about their fears regarding necessary treatments in the future. Only a minority was expecting real difficulties to get their individual therapies itself (132/342, 38.5%), but the majority of participating patients (186/354, 52.5%) has been afraid of prolonged breaks between therapies or waiting times for necessary treatments because of COVID-19 pandemic.

Contact lock at hospital. We asked our participants to comment the common and total restriction of visits in hospitals during the pandemic period. Our hospitalized patients have had additional mental stress because of this decision in 69/121 (57%) cases only. The out-door patients and cancer survivors fear this situation much more. 226/309 (73.1%) would await distress because of isolation.

Stress thermometer. At last we requested the participant to categorize the mental status of the medical staff involved in their therapy. 117/339 (34.5%) had seen concerned physicians and nurses, only a small minority was described as cool (15/339, 4.4%).

Physicians’ survey

The oncologists answered during the first two weeks of the project.

94 physicians haven taken part in our survey. 29 oncologists worked at their own practice, 57 doctors were working at hospitals, 8 participants have not given an information about their working place. 32/94 participants (34%) were living in Federal states with higher COVID-19-infection rates. 18 of participating physicians (19%) were involved in direct care for COVID-19-positive patients.

Impact on daily life. 68 oncologists (79.1%) reported high or very high impact of pandemic on their daily professional work. 18 felt no further influence. 38 physicians (44.2%) were confused about the public information policy and the different discussions among scientists on TV or social media. 55/85 physicians (64.7%) received an increased number of questions from their patients (about COVID-19 and its management).

Mental stress for patients. 70/83 oncologists (84.3%) have seen increased mental stress of their patients. 16/86 answering colleagues (18.6%) have observed fears and resulting self-isolation, 64/86 physicians (74.4%) had reported about their unsettled patients with cancer and related anxieties.

Physical consequences for patients. 46/85 oncologists (54.1%) await long-time physical changes in general appearance of their patients.

Anti-cancer therapies. 37/84 oncologists (44.0%) reported to observe increased fears of patients regarding their therapy. Patients needed more time to talk in 23/84 participants (27.4%) for adjunctive therapies as well as in 22/78 doctors (28.2%) for palliative treatment strategies. 37/75 doctors (49.3%) reported having difficulties to get necessary investigations or beds at hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Contact lock at hospital. 82/84 participating oncologists (97.6%) awaited strong or very strong difficulties for the care-process because of the common total restrictions of visiting patients at hospital.

Self-reflection of physicians. 53 oncologists (56.4%) reported to be stressed by the situation. 19 (20.4%) of them hade fears because of the financial burdens. 46 (48.9%) anticipated negative physical and/or mental sequels for themself after the Covid-19 pandemic. The anxiety to become infected was part of this problem in 35/86 participants (40.7%).

Stress thermometer. At the time of survey 31/85 physicians (36.5%) saw themself as concerned or very stressed/burned. 6/85 (7.1%) described themselves as cool.

Survey among medical staff

We have seen two participation-waves in mid of April (full lockdown) and mid of May (beginning relaxation).

73 care givers have taken part in this survey. We registered 25 nurses (8 specialized for oncology), and 43 specialized therapists (speech and swallowing, nutrition, physiotherapy). 5 participants have not answered at this category. 18 are working at out-door base, 51 are working at hospitals. 5 participants have not given information about their working background. 28/73 participating care workers were living in federal states with higher COVID-19-infection rates. 10 were involved in direct care for COVID-19 positive patients.

Impact on daily life. 59/69 (81.2%) participants reported a strong or very strong impact on their daily work in cancer care. 48/69 (69.6%) were confused by the public discussions about pandemic management and different view points in media and social media. 33/73 (45.2%) participants reported getting more questions and hearing more doubts on treatment from their patients due to COVID-19.

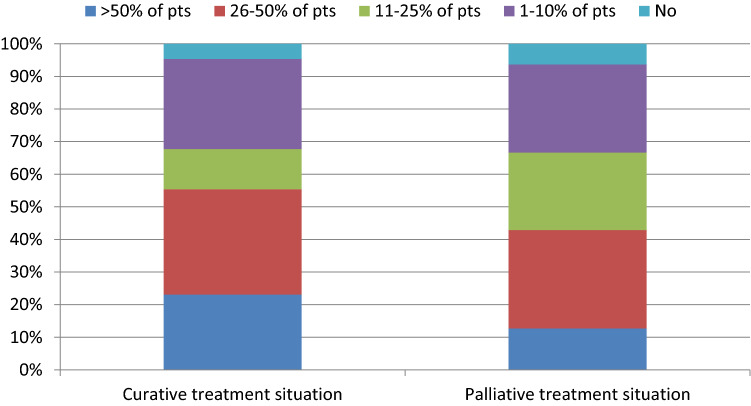

Mental stress of patients. 65/68 (95.6%) nurses or therapists observed an increased level of mental stress of their patients. In curative treatment situations, they registered requests to stop the on-going therapy in > 50% of the patients at 15 practices/clinics, in 26–50% at 21 practices/clinics, in 11–25% at 11 places, and in 1–10% at 18 places. In palliative situation, we registered such requests in > 50% of the patients at 8 places, in 26–50% at 19 places, in 11–25% at 15 places, in 1–10% at 17 places.

Anti-cancer therapy. 32/69 (46.4%) participants reported difficulties to get necessary investigations or dates for hospitalizations or surgeries.

Contact lock at hospital. 64/67 nurses/therapists saw strong or very strong problems/concerns for their patients resulting from the strict contact lock at the hospitals.

Self-reflections of nurses/therapists. 30/69 feared mental and/or physical consequences for themself due to Covid-19 pandemic in the future. In 36/69 cases, the participants reported anxiety to become infected by the virus. Financial fears were reported by 19 participants.

Stress thermometer. 31 participants were concerned/very stressed, 3 were cool at the time of survey.

Survey among psychologists and spiritual care givers

One hundred and fifty-two participants took part in our survey for psychologists/spiritual care givers. The majority worked at hospitals (n = 82) or coaching points for tumor patients (n = 37). Fifty-six (36.8%) were living in areas with higher infection rates. 21 (13.8%) were already involved in the therapy of COVID-19 infected patients.

Impact on daily life. 100 out of 132 answering participants (75.8%) reported to be restricted in the professional work by the regulations of public lockdown. 61/131 (46.6%) said that they were confused about diverging opinions and statements regarding the virus and the pandemic situation. 68/131 (51.9%) registered more and more intensive questions by patients.

Mental stress for patients. Fourty-five (38.1%) participants reported that a quarter or more cancer patients would think about stopping their actual anticancer therapy. High mental burden for cancer patients was seen by 125/130 (96.1%) participants.

Anti-cancer therapy. Difficulties to organize the oncology services were reported by 39 participants 25.7%). Thirteen participants (8.6%) felt that their teams are able to compensate existing problems.

Contact lock at hospital. 123/129 psychologists/spiritual care givers (95.3%) were describing prohibition of visits as one of the main problems for patients during the pandemic.

Self-reflections of psychologists/spiritual care givers. 70/127 participants (55.1%) feared further personal mental or physical consequences due to the actual pandemic. 34/127 (26.8%) were afraid of getting infected with the virus.

Stress-thermometer. 129/152 of the participants have answered this question. 3 participants (2.3%) felt burned, 44 (34.1%) were concerned, the remaining care givers saw themselves as normal or cool.

Psychologists view on other professions. 128/152 reported about their impression of other health care professionals. The emotional situation was described as cool by 2 participants (1.5%), as normal by 34 participants (26.7%), as moved/heated by 87 participants (62.5%) and as burned by 5 participants (3.9%).

Further statistical analysis

Patients with active cancer disease were more often concerned regarding on-going treatments and organization of oncology services (p = 0.002) than survivors. Furthermore, those patients were more confused by diverging information on COVID-19 in press, on TV and in social media (p = 0.02). There also is a trend to more mental stress in this subgroup (p = 0.07).

The federal state of home and in consequence the infection rate had no impact on patients’ answers to any of the questions. The participating number of physicians and other care givers was too small to perform this analysis for the medical professionals.

Analyzing the distress thermometer data, patients showed a stable situation between April and May 2020. In contrast, professionals reported an increasing level of their mental burden (distress) between both points of survey (see Fig. 2). Figure 3 summarizes the differences of external views on emotional burdens (psychologist, patients) and self-reflection (physicians, medical staff, psychologists). An additional principal component analysis (Fig. 4) underlines the eminent need of a professional supervision (see view of psychologists on the others).

Fig. 2.

Heat map showing increasing emotional stress level (self-perception) of medical staff

Fig. 3.

Heat map showing the different perception of emotional stress. Nurses’, physicians’, psychologists’ self reflection compared to the external view of patients and psychologists

Fig. 4.

Principal component analysis demonstrating importance of professional external view on the cancer care system

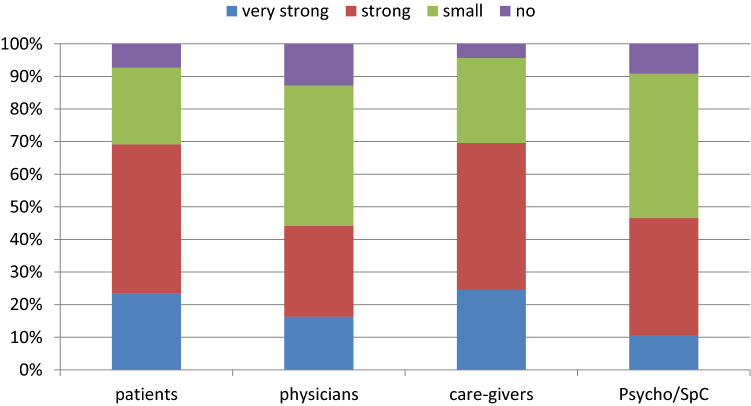

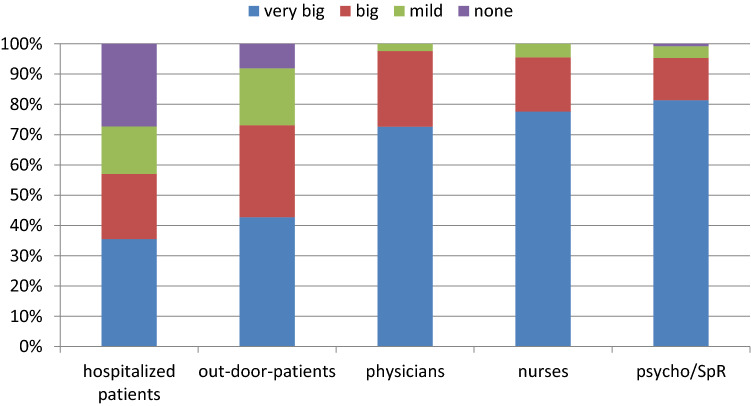

Figures 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 summarizes all patient-related problems from the viewpoint of all stakeholders. Main points are the mental burden and questions/problems of the organization of oncology services during pandemic times.

Fig. 5.

Common restrictions of daily life

Fig. 6.

Confusion about public information policy

Fig. 7.

Increase of mental stress for patients

Fig. 8.

Participants observing patients (pts) initiated discussions about therapy end or treatment breaks

Fig. 9.

Fears and actual thoughts regarding treatment delays

Fig. 10.

Burden as a result of contact lock for hospitalized patients

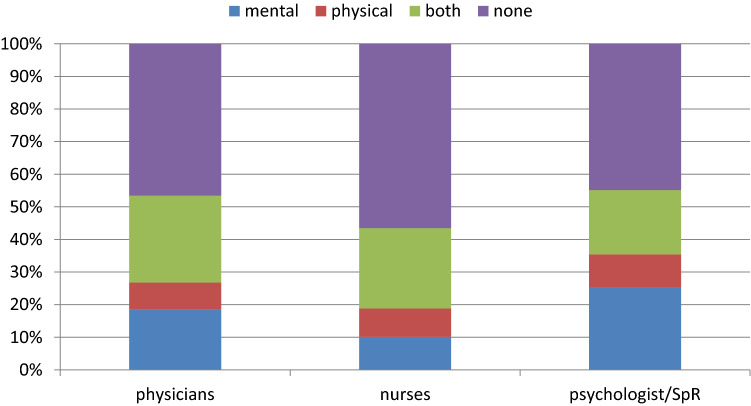

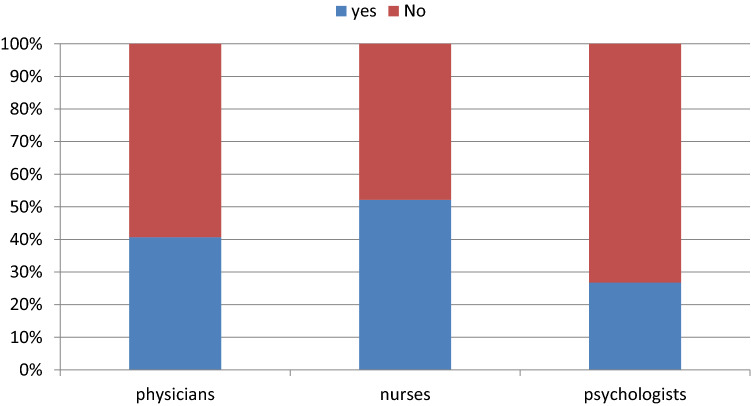

Figures 11, 12, 13 summarizes all professional-related problems from the viewpoint of all stakeholders. These figures focus on the existing fears and awaited problems. The high rate of deep impressed professionals must be discussed in relation to the heat maps as mentioned above.

Fig. 11.

Acute mental stress of professionals

Fig. 12.

Fears of professionals regarding own long-time problems

Fig. 13.

Fears to become infected

Furthermore, free text answers of psychologists/spiritual care givers were clustered and are shown as a word cloud (see Fig. 14). These data are the content for further qualitative and quantitative analyses.

Fig. 14.

Word cloud illustrating therapy-problems of psychologists/ministers during Covid-19 pandemic (first wave). Clusters were “talk/communication”, “isolation”, “distance”, “burden”, “facial expressions”, “fears”, “shortage”, “uncertainty”, “ressources”, “therapy”, “no visits”

Discussion

With more than 750 patients and health care professionals participating in our online survey are, the here presented data set presents—to the best of our knowledge—the largest survey during the first wave of the pandemic in Europe. Despite several drawbacks as the quickly developed and unvalidated instruments, online distribution via different organizations thus mainly recruiting selected and the special motivated participants, this is an authentic and wide-ranging image of the experiences and attitudes of the actors in cancer care, which reflects the impressions of the moment in April/May 2020.

To our opinion, the message from our data is less medical but strongly political and ethical: During the first wave patients have experienced cancer care at high level in Germany. Main problems are seen in strategic and mental topics. But this system has reached its borders and we have to protect the system itself and its professional care givers. Some aspects should discussed in detail.

Focus cancer patients

Confusion seems to be a phenomenon in crisis times. Nicola et al. described problems in communicating about COVID-19 around the world, which are existing independently from country and culture (Nicola et al. 2020).

Uncertainty has a relevant impact on patients. During the first wave patients have developed their own coping strategies. They were searching nature and out-door activities (Büssing et al. 2020). So, they were able to limit the physical consequences of the first lockdown. A more restrictive lock down would break this system and avoid these possibilities of coping.

At the moment, the main burden seems to be a mental one. First studies report about increasing rates of depression among cancer patients (Zheng et al. 2020). Fears and premonitions of patients include delay of diagnosis, isolation from family and friends, other barriers to cancer, supportive or social care. Precipitous decisions, based on these premonitions are reported (no treatment, rejection of adjuvant therapy, therapy discontinuation, therapy breaks). Initiating factor is the impact of social distancing arriving at its maximum during the lock down on private life for many people, for example the ban of visiting hospitalized relatives. Personal contact to COVID-19-patients or own infection are not affecting this answers/impression regarding the pandemic situation at all. Cancer patients have specific concerns about isolation experiences as it was described by Tanya Campell in 1999 (Campbell 1999).

A relevant part of German medical and health care professionals participating in our survey has given the signal of confusion and uncertainty with respect to the public discussion of COVID-pandemic and its management. As informed coaching and transparent information policy are highly important for risk groups like cancer patients. In the light of the presented results, all actors from science and politics should avoid producing fears and panic as instruments of involving behavior or public opinions (Anonymous 2020).

In the health care system, physicians and nurses managed to make German cancer patients feeling safe despite all restrictions. Most patients participating were satisfied with the cancer services during the first wave of pandemic. Public health system supplied continued care for people suffering from life-threating diseases as cancer. From the perspective of most patients, the medical care they experienced was professional and adequate to situation. Yet, we have to realize, that most probably, taking part in an online survey selects participants who feel rather well and are not overwhelmed from fears or have a poor course of their disease.

Focus medical staff

The personal experience of medical staff during the first wave of the pandemic is quite similar to that of patients. The professionals were also describing individual restrictions and the irritations as mentioned above. Analyzing their working situation, they discuss problems of pandemic management or possible negative impact on cancer services. Moreover, they also recognize the strong mental burden on their patients. A uniform warning from all professional groups warns against this mental burden and the resulting danger for ongoing or futural anti-cancer strategies. This is a not openly uttered, yet alarming warning that must be listen by the society and the politicians as a task for all of us.

An important result of our survey is the enormous burden due to COVID-19 pandemic, which is seen in all professional groups. The medical literature has begun discussing this point (El-Hage et al. 2020; Walton et al. 2020). The majority of health care workers is awaiting decreasing income, increasing individual physical or mental problems. This pandemic means high professional burden, private fears and difficulties, and the experience of limited social and personal resources. With a growing number of nurses, physicians and other care givers dropping out of the system due to exhaustion, bodily or mental illness or burn-out, the stress on the remaining will even increase as already can be seen in structurally weaker regions (El-Hage et al. 2020; Petzold et al. 2020). Thus, even the strong German health care system might collapse in a second wave. There is not much time left to develop strategies of support and discharge for all professionals of the health system and to reliably realize this support.

Heat maps are no validated instrument to assess mental stress, yet, like any grading (for example a Liktert scale), they give us an idea about the increasing mental burden of our participating professionals during the lockdown. Repression seems to be a relevant coping strategy for all professions, psychologists included. As we have shown, this coping strategy comes to its borders of decompensation. The external view of psychologists/spiritual care givers on the medical professionals clearly underlines this impending collapse.

One means of support might be supervision during pandemic waves or another crisis. Supervision allows not only to recognize and acknowledge negative developments but also to (re-) create individual coping and ways out of the critical situation. Supervision including self-reflection and external views might be helpful for everybody in cancer care. Yet, strategies to increase voluntary and active participation are not easy to find especially in times when “there is no time” (Petzold et al. 2020).

Focus consequences

Despite or because of the second wave of the pandemic, stabilization and even improving cancer services for actual and future cancer patients is of upmost importance. The German National Academy of Science Leopoldina has published and adapted its recommendations and statements during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic (Leopoldina 2020a, b, c, d). The statements emphasize that information, strategic data collection, and prospective research are necessary. Political and societal decisions should be informed by science. But, as scientific results are growing and knowledge is changing, the difficulty is to preserve trust. Most important to achieve this in a globally threatening situation might be consistency, which is made transparent and understandable to people.

Leopoldina’s fourth statement “focuses on aspects of patient-oriented medical and care services for all patients during an on-going pandemic. This statement also presents measures that lead to a more robust and adaptive healthcare system” (Leopoldina 2020d). In the light of the presented survey, some key points emerge for cancer care in the future:

Well established and stable daily routine work at hospitals and practices is the fundament of the high level of cancer care in Germany and should be respected and supported during the pandemic.

Delays in diagnostics and treatments for cancer patients and cancer survivors must be avoided. Necessary treatments are life-saving in case of cancer and a “must be” during pandemic.

Enough space and time is needed for each individual patient, his/her relatives more so in time of “social” distancing, which must not end in isolation, which already has increased dramatically. The individual conversation gets highly important.

Patients need spiritual and mental support bridging “social” distancing and mouth nose protection. Our aim is the coaching and discussion with our clients at their level of knowledge.

Professionals need adequate working conditions (time, space, manpower) for their daily work. They need organized support and offers.

Protection of the professional caregivers has to become a topic in oncology. Self-protection is necessary for all of us, not only for palliative workers (Liu et al. 2020; Tahan 2020).

As the impact of the regulations due to the pandemic reaches all parts of the health care system as well as all tasks within our society, there is a high need of a broader spectrum of participating professions and disciplines. Diverse expertise must be included as early as possible in consultations processes to anticipate consequences of regulation processes as early as possible. Objective and transparent information policy would be helpful for patients to experience themselves as participants not as victims.

With the second wave starting and stressing that it “is not over now”, we should register and assess middle term and long-time changes and their consequences for the patients in cancer care. Ethical discussions are necessary to reflect the shift of resources in the health care system. Furthermore, we have to talk about the autonomy of older patients, children and ill people, including cancer patients. Besides the direct impact on physical and mental health, the socioeconomic impact on cancer patients and the whole population must be assessed as this might have strong impact on incidence and mortality of chronic diseases.

Last but not least, we should be very cautious not to overlook the disadvantaged and to not only evaluate but to act. As our data show, caregivers and partners are much stronger affected than patients. During the lock down most offers of support were closed, even self-help groups did not meet and digital support is no adequate substitute. There are other disadvantaged, as poor, old and frail patients, patients with lower health literacy, lo knowledge of our language or a background of migration.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Anonymous (2020) Das interne Strategiepapier des Innenministeriums zur Corona-Pandemie/abgeordnetenwatch.de. https://www.abgeordnetenwatch.de/blog/informationsfreiheit/das-interne-strategiepapier-des-innenministeriums-zur-corona-pandemie. Accessed 7 Apr 2020

- Büntzel J, Klein M, Keinki C, Walter S, Büntzel J, Hübner J (2020) Oncology services in corona times: a flash interview among German cancer patients and their physicians. J Cancer Res ClinOncol. 10.1007/s00432-020-03249-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büssing A, Hübner J, Walter S, Gießler W, Büntzel J (2020) Tumor patients’ perceived changes of specific attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors due to the COVID-19 pandemic and its relation to reduced wellbeing. Front Psychiatr. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.574314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell T (1999) Feelings of oncology patients about being nursed in protective isolation as a consequence of cancer chemotherapy treatment. J AdvNurs 30(2):439–447. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01099.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher E (2020) Solidarity and responsibility during the coronavirus crisis. März, pp 1–8.

- El-Hage W, Hingray C, Lemogne C, Yrondi A, Brunault P, Bienvenu T, Etain B (2020) Health professionals facing the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: What are the mental health risks? L’Encephale 46(3S):S73-80. 10.1016/j.encep.2020.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hübner J (2020) Regelversorgung: Angst vor der Isolation 117 (25): A-1266/B-1069.

- Korzilius H, Falk O (2020) Rückkehr zur regelversorgung: Chronische Krankheiten machen keine Coronapause. Nr. 117: A-1037/B-877.

- Leopoldina (2020a) Coronavirus pandemic in Germany: challenges and options for intervention (2020). Nationale Akademie Der Wissenschaften Leopoldina. 21, März 2020. https://www.leopoldina.org/en/publications/detailview/publication/coronavirus-pandemic-in-germany-challenges-and-options-for-intervention-2020/.

- Leopoldina (2020b) Coronavirus pandemic—measures relevant to health (2020). Nationale Akademie Der Wissenschaften Leopoldina. 3, April 2020. https://www.leopoldina.org/en/publications/detailview/publication/coronavirus-pandemic-measures-relevant-to-health-2020/.

- Leopoldina (2020c) Coronavirus pandemic—sustainable ways to overcome the crisis (13 April 2020). Nationale Akademie Der Wissenschaften Leopoldina. 13, April 2020. https://www.leopoldina.org/en/publications/detailview/publication/coronavirus-pandemic-sustainable-ways-to-overcome-the-crisis-13-april-2020/.

- Leopoldina (2020d) Coronavirus pandemic: Medical Care and Patient-Oriented Research in an Adaptive Healthcare System (2020). Nationale Akademie Der Wissenschaften Leopoldina. 27, Mai 2020. https://www.leopoldina.org/en/publications/detailview/publication/coronavirus-pandemic-medical-care-and-patient-oriented-research-in-an-adaptive-healthcare-system-2/.

- Liu Q, Luo D, Haase JE, Guo Q, Wang XQ, Liu S, Xia L, Liu Z, Yang J, Yang BX (2020) The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet Global Health 8(6):e790–e798. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30204-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metsalu T, Vilo J (2015) ClustVis: a web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using principal component analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res 43(W1):W566-570. 10.1093/nar/gkv468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola M, Sohrabi C, Mathew G, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Griffin M, Agha M, Agha R (2020) Health policy and leadership models during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review. Int J Surg 81:122–129. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petzold MB, Plag J, Ströhle A (2020) UmgangmitpsychischerBelastungbeiGesundheitsfachkräftenimRahmen der COVID-19-Pandemie. Der Nervenarzt. 10.1007/s00115-020-00905-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert-Koch-Institut (2020) 15/05/2020—Updated status for Germany, Mai.

- Tahan HM (2020) Essential case management practices amidst the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) crisis: Part 2. Prof Case Manag. 10.1097/NCM.0000000000000455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton M, Esther M, Michael DC (2020) Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. Doi: 10.1177/2048872620922795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zheng X, Gang T, Ping H, Fugen H, Xiying S, Yanjun X, Like Z, Guonong Y (2020) Self-reported depression of cancer patients under 2019 novel coronavirus pandemic. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3555252. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3555252.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.