Platelets are not just the cells that mediate coagulation. Over the last years, there has been increasing and compelling evidence that these cells may act as key regulators in immune responses and participate in the pathogenesis of various immune-mediated diseases.1-3 It has been shown that platelets can function as antigen presenting cells and activate T cells through MHC-I.4 Patients with myocardial infarction (MI) have activated platelets but whether these platelets interact with the immune system is not completely clear. It has been well established that immediate treatment with factors that prevent platelet aggregation is crucial for these patients; the sooner these agents are given, the better the outcome.5 T cells have been implicated in the pathogenesis of MI.6 Autoreactive T cells may have a role in the destabilization of the atherosclerosis plaque and plaque rupture. Regulatory T cells (CD4+CD25+high, Foxp3+; Treg) represent an important subset of T cells essential for immune homeostasis that controls activation of T cells.7 Up to now, data on Treg have shown that these cells have a protective role in atherosclerosis. Treg alterations in patients with MI with ST elevation (STEMI) have not been fully elucidated and8 there are no available data on the possible interaction of activated platelets with the T cells in these patients.9-12

The micro RNAs (miRNAs) represent small non-coding sequences with the ability to suppress different genes. In mice, the deficient expression of the miR155 was associated with enhanced atherosclerosis, decreased plaque stability and decreased Treg.13 However, the role of miR155 has not been established in patients with MI.

We aimed to investigate whether T cells can be activated by the circulating activated platelets from patients with STEMI and explore how the Treg cell population is affected.

After written informed consent had been obtained, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from 33 patients with STEMI (29 men, 4 women, mean age 62.5 years) at the time of hospital admission at diagnosis, before any treatment, as well as 5 days and 30 days later. Ten healthy subjects and five patients with unstable angina served as the control and disease-control group, respectively. We also isolated platelet rich plasma or plasma alone from the patients and healthy subjects and used it in mixed cultures with the isolated PBMC. The membrane expression of CD69 was used as a marker for T-cell activation. Three additional patients who received aspirin or clopidogrel before admission were also analyzed as an internal control group (Online Supplementary Appendix). We analyzed the percentages of CD4+CD25+highFOXP3+ cells representing the regulatory subset (Tregs) at all three time points, as described above (Day 0, day 5, and at one month of follow-up).14 The miR155 levels were evaluated using real-time polymerase chain reaction in samples from patients and healthy individuals. In STEMI patients, the expression of miR155 was evaluated at admission and when the patients were discharged (Day 0 and Day 5, respectively). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Patras University Hospital.

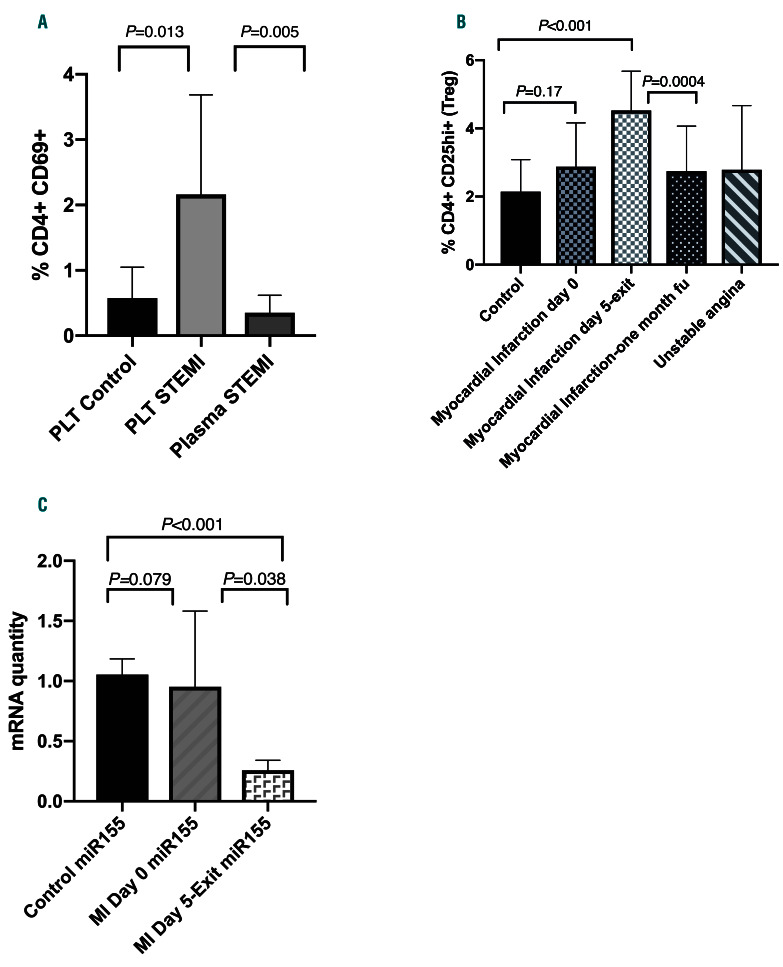

We first examined the activation of T cells in mixed cultures as described above (Online Supplementary Appendix). The expression of CD69 on the surface of T cells was used as a marker for T-cell activation. T cells that were incubated with platelets from patients with STEMI showed a statistically significant increase in CD69 expression (2.163% vs. 0.575%; P=0.013) compared to the T cells that were incubated with platelets from healthy individuals (Figure 1Α). We did not record any activation in T cells that were incubated with plasma alone either from patients with STEMI or from healthy individuals. These results show that the activation of T cells incubated with platelets is specific only for platelets from patients with STEMI. It is also of note that T cells that were incubated with platelets from patients previously treated with aspirin or clopidogrel did not show any activation (data not shown) and the T cell-CD69 surface expression was comparable to that seen in T cells cocultured with platelets obtained from healthy individuals. It has been proposed that platelets may also have a role in the activation of the immune system and may represent key players in the immune homeostasis; our data are in agreement with this.

Tregs can recognize self from non-self antigens and can down-regulate activation of T cells.7 Based on our results that activated platelets can activate T cells, we next examined the percentages of Tregs using flow cytometry to explore whether Tregs are altered in order to control the platelet-initiated activation. Upon presentation, patients with STEMI did not show any statistically significant different numbers in Tregs compared to healthy individuals. However, 5 days later, patients with STEMI displayed a statistically significant increase in Treg numbers compared with the two control groups. One month later, Treg numbers returned to the initial presentation levels (Figure 1B). To our knowledge, this is the first time that Tregs have been studied serially at different time points following a STEMI. Tregs increase during the first days after the STEMI and possibly represent the T-cell subset that is trying to eliminate the activation of the immune system and the inflammatory response.

Recently, it was shown that miR155 is up-regulated in patients with viral myocarditis.15 Also, differential expression of the Tregs was shown to correlate with the expression of miR155.13 To explore the mechanism of Treg upregulation, the levels of miR155 were evaluated. Patients with STEMI displayed comparable levels of miR155 at presentation to healthy individuals. However, five days later, patients with STEMI had a statistically significant decrease in miR155 levels (P<0.001) that was inversely correlated with the increased Treg numbers observed at the same time point (Figure 1C). Alterations in different miRNAs expression have been associated with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis, but also with solid tumors. Results from mouse models implicate deficient expression of the miR155 with decreased plaque stability and decreased Tregs.13 Up to now, the role of miR155 has not been established in patients with MI. Here we show for the first time that patients with STEMI have decreased miR155 levels that inversely correlate with Treg numbers.

Activated T cells may have a dual role in plaque rupture. T cells secrete IFN-γ which inhibits the formation of new collagen, essential for the stability of the plaque in coronary arteries. Additionally, such T cells interact with macrophages leading to increased collagen degradation. Decreased formation combined with increased degradation of collagen contributes to plaque rapture.6 Our study shows that platelets from patients with STEMI can activate T cells ex vivo. This activation of circulating platelets may lead to an increase of the regulatory T-cell subset, possibly via the down-regulated expression of miR155. The increase in Treg observed in parallel with the decreased miR155 expression perhaps represent an effort of the immune system to control those auto-reactive T cells that participate in plaque rapture. From the current study, we cannot confirm whether platelets are only activated by necrosis alone or whether necrosis directly activates the immune response. Our observations are preliminary and further studies are needed to establish a causal link between activated platelets and T cells. Moreover, the precise characterization of the mechanisms implicated in activated platelet:T-cell interaction might help prevent myocardial infarction.

Figure 1.

Platelets from patients with STEMI can activate T cells and increase regulatory T cells. (A) Platelets from patients with STEMI activate T cells ex vivo. T cells incubated with platelets obtained from patients with STEMI displayed a statistically significant increased expression of the surface activation marker CD69 (P=0.013) compared to T cells incubated with platelets from healthy individuals. There was no activation in T cells when incubated with plasma from patients with STEMI. PLT control: activation in T cells when treated with platelets from healthy control subjects; PLT STEMI: activation in T cells when treated with platelets from patients with STEMI; Plasma STEMI: activation of T cells in cultures when treated only with plasma from patients with STEMI. (B) Patients with STEMI display a statistically significant increase in Treg numbers. Patients with STEMI at admission (Day 0) show comparable levels of Tregs with the healthy control group and with patients with unstable angina. Five days after admission, patients with STEMI displayed statistically significant increase in Tregs compared to controls, and one month later, Treg numbers in STEMI patients return to the admission levels. Treg at presentation versus 5 days after admission: 2.875% versus 4.521%; P=0.0002. Treg 5 days after admission versus 1 month follow-up (fu) after admission: 4.521% versus 2.745%; P=0.0004. Control: healthy control subjects; Myocardial infarction day 0: STEMI patients at admission; Myocardial infarction day 5: STEMI patients 5 days after admission; Myocardial infarction one month fu: STEMI patients one month after initial admission at fu; Unstable angina: Control group with unstable angina. (C) Decreased levels of miR155 in patients with STEMI. Patients with STEMI at admission (MI Day 0) show comparable mRNA levels of miR155 with the healthy control group (P=0.79). Five days after admission, patients with STEMI displayed a statistically significant decrease in miR155 mRNA levels compared to controls (P=<0.001) and this decrease was associated with the increase in Tregs observed in the same patients at the same time point. Control miR155: healthy control group; MI Day 0 miR155: patients with STEMI at admission; MI Day 5-Exit miR155: patients with STEMI 5 days after admission.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Davis RP, Miller-Dorey S, Jenne CN. Platelets and coagulation in infection. Clin Transl Immunology. 2016;5(7):e89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Middleton EA, Weyrich AS, Zimmerman GA. Platelets in pulmonary immune responses and inflammatory lung diseases. Physiol Rev. 2016;96(4):1211-1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carestia A, Kaufman T, Schattner M. Platelets: new bricks in the building of neutrophil extracellular traps. Front Immunol. 2016; 7:271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lesley M. Chapman, et al Platelets present antigen in the context of MHC class I. J Immunol. 2012;189(2):916-923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briasoulis A, Telila T, Palla M, Siasos G, Tousoulis D. P2Y12 receptor antagonists: which one to choose? a systematic review and metaanalysis. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(29):4568-4576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Libby P. Mechanisms of acute coronary syndromes and their implications for therapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(21):2004-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in immunological tolerance to self and non-self. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(4):345-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pastrana JL, Sha X, Virtue A, et al. Regulatory T cells and atherosclerosis. J Clin Exp Cardiolog. 2012;2012(Suppl 12):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy AJ, Tall AR. Disordered haematopoiesis and athero-thrombosis. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(14):1113-2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofmann U, Beyersdorf N, Weirather J, et al. Activation of CD4+ T lymphocytes improves wound healing and survival after experimental myocardial infarction in mice. Circulation. 2012; 125(13):1652-1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharir R, Semo J, Shimoni S, et al. Experimental myocardial infarction induces altered regulatory T cell hemostasis, and adoptive transfer attenuates subsequent remodeling. PLoS One. 2014; 9(12):e113653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.del Rosario Espinoza Mora M, Böhm M, Link A. The Th17/Treg imbalance in patients with cardiogenic shock. Clin Res Cardiol. 2014;103(4):301-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donners MM, Wolfs IM, Stöger LJ, et al. Hematopoietic miR155 deficiency enhances atherosclerosis and decreases plaque stability in hyperlipidemic mice. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solomou EE, Rezvani K, Mielke S, et al. Deficient CD4+ CD25+ FOXP3+ T regulatory cells in acquired aplastic anemia. Blood. 2007; 110(5):1603-1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Connell RM, Kahn D, Gibson WS, et al. MicroRNA-155 promotes autoimmune inflammation by enhancing inflammatory T cell development. Immunity. 2010;33(4):607-619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.