Significance

The thyA mutants of Escherichia coli cannot synthesize their own thymidine (dT) and rapidly die without dT supplementation. Confusingly, this thymineless death has an integral resistance phase, as if chromosomal damage has to accumulate before eventually becoming irreparable. Here we show that during the resistance phase, the thyA mutants survive by deriving dT from a significant pool of endogenous dTDP-sugar conjugates. Inability to synthesize dTDP-sugars shortens the resistance phase, while inability to recover dTTP from this pool eliminates the resistance phase altogether. Moreover, the resulting dT-hyperstarvation causes catastrophic chromosome loss and cell lysis. We conclude that the resistance phase, rather than being a part of thymineless death, delays acute starvation, while dT-hyperstarvation has the second, cell envelope dimension.

Keywords: enterobacterial common antigen, chromosome fragmentation, chromosome replication, dTDP-glucose, cell lysis

Abstract

Thymineless death in Escherichia coli thyA mutants growing in the absence of thymidine (dT) is preceded by a substantial resistance phase, during which the culture titer remains static, as if the chromosome has to accumulate damage before ultimately failing. Significant chromosomal replication and fragmentation during the resistance phase could provide appropriate sources of this damage. Alternatively, the initial chromosomal replication in thymine (T)-starved cells could reflect a considerable endogenous dT source, making the resistance phase a delay of acute starvation, rather than an integral part of thymineless death. Here we identify such a low-molecular-weight (LMW)-dT source as mostly dTDP-glucose and its derivatives, used to synthesize enterobacterial common antigen (ECA). The thyA mutant, in which dTDP-glucose production is blocked by the rfbA rffH mutations, lacks a LMW-dT pool, the initial DNA synthesis during T-starvation and the resistance phase. Remarkably, the thyA mutant that makes dTDP-glucose and initiates ECA synthesis normally yet cannot complete it due to the rffC defect, maintains a regular LMW-dT pool, but cannot recover dTTP from it, and thus suffers T-hyperstarvation, dying precipitously, completely losing chromosomal DNA and eventually lysing, even without chromosomal replication. At the same time, its ECA+ thyA parent does not lyse during T-starvation, while both the dramatic killing and chromosomal DNA loss in the ECA-deficient thyA mutants precede cell lysis. We conclude that: 1) the significant pool of dTDP-hexoses delays acute T-starvation; 2) T-starvation destabilizes even nonreplicating chromosomes, while T-hyperstarvation destroys them; and 3) beyond the chromosome, T-hyperstarvation also destabilizes the cell envelope.

Acute starvation for thymidine triphosphate (dTTP), one of the four precursors for DNA synthesis, is lethal in both bacterial and eukaryotic cells (1). Following a short resistance phase, the rapid death of thyA auxotrophs in media lacking thymine or thymidine (“T-starvation”) known as thymineless death (TLD) was first described in Escherichia coli (2, 3) and since then was extensively studied to identify the cause of lethality (1, 4, 5). Because the bulk of thymidine (dT) in any cell is used for chromosomal DNA synthesis, lack of dT was always assumed to cause some form of chromosomal damage, and hence the role of DNA repair pathways during T-starvation was the focus of intense investigation (6–9). These studies revealed that certain pathways, like double-strand break repair initiated by the RecBCD helicase/nuclease, Holliday junction resolution by RuvABC, and antirecombination activity of the UvrD helicase, keep cells alive during the resistance phase of T-starvation. Other events, like attempted single-strand gap repair initiated by the RecFOR complex, the function of the RecQ helicase and RecJ exonuclease, and SOS induction of the cell division inhibitor SulA, are detrimental for T-starved E. coli cells (8, 10–12). However, the thyA mutants of E. coli inactivated for all of the latter “toxic DNA repair pathways” still die by two orders of magnitude during T-starvation (8), indicating some other yet-to-be-identified major lethality factors.

Since actively growing cells continuously require a lot of dT to replicate chromosomal DNA, existing replication forks were inferred to be the points of TLD pathology (7, 8, 13–15). Indeed, T-starvation severely inhibits chromosomal DNA replication (15) and is associated with accumulation of single-stranded DNA, suggesting generation of single-strand (ss) gaps by attempted replication in the absence of dT (7, 16). These ss-gaps induce the SOS response (7, 8, 17), which contributes to the pathology of TLD by induction of the SulA cell division inhibitor (8). Also, replication initiation spike in the T-starved cells triggers the destruction of the origin-centered chromosomal subdomain during TLD, suggesting that it is the demise of the nascent replication bubbles, rather than the existing replication forks, that eventually kills the chromosome (15, 17).

Although the thyA mutants cannot synthesize dT, they grow normally if supplemented with exogenous dT/T. Upon removal of dT from the growth medium, the E. coli thyA strain has a two-generation-long resistance phase (also called the lag phase) (1), when the colony-forming unit (CFU) titer of the culture stays constant (Fig. 1 A, Top). This is followed by the rapid exponential death (RED) phase, when the CFU titer falls by approximately three orders of magnitude within several hours (Fig. 1 A, Top).

Fig. 1.

A significant endogenous pool of LMW dT decreases during T-starvation. (A) The phenomenon of TLD in E. coli suggests accumulation of chromosomal damage during the resistance phase (green) that would later kill cells during the RED phase (red). The data are adapted from ref. 16. Henceforth, the data are means (n ≥ 3) ± SEM. Cultures were grown at 37 °C in the presence of dT, which was removed at time = 0, while incubation in the growth medium continued. Top, cell death begins after 1-h-long resistance phase, during which the culture titer is stable. Bottom, during the same first hour without dT, cells manage to synthesize the amount of DNA equal to half of what they already had before dT removal. However, during the RED phase genomic DNA is gradually lost. (B) Scheme of 50% methanol fractionation of the intracellular thymidine into HMW dT (the dT content of the chromosomal DNA) and LMW dT. (C) A 0.7% agarose gel analysis of the HMW and LMW fractions of the 50% methanol-treated cells, as well as pure LB treated the same way, for DNA and RNA content (staining with ethidium bromide). Inverse images of stained gels are shown, in which the indicated samples were either incubated in the buffer or with the indicated enzyme (DNase I for the top gel, RNase A for the bottom gel). (D) The size of the LMW-dT pool, normalized to the HMW-dT content of the chromosome, either during normal growth in dT-supplemented medium or during T-starvation. Thymidine was removed at time = 0. The strain is KKW58.

An obvious explanation for the resistance phase is existence of an intracellular source of dT to support slow replication; however, chromosomal DNA amount was consistently reported to remain flat during TLD (15, 18–20). Besides, the recent systematic test of potential candidates for a source of dT or its analogs supporting the resistance phase returned empty-handed (16). Thus, the mechanisms behind the initial resistance to T-starvation, followed by the sudden shift to the RED phase remain unclear, leading to a reasonable assumption that the resistance phase is an integral part of the TLD phenomenon, during which chromosomal damage accumulates until it becomes irreparable, ushering the RED phase (1, 5). Specific early events during the resistance phase of TLD that would later turn poisonous during the RED phase were proposed to be futile incorporation–excision cycles (1, 21), ss-gap accumulation causing the SOS induction (1, 8, 16), futile fork breakage-repair cycles (16, 22), and overinitiation from the origin (5, 15).

Two recent observations, in combination with an old popular TLD explanation, further support the idea of the resistance phase as the TLD period during which chromosomal damage accumulates without affecting viability for the time being. First, the resistance phase coincides with accumulation of double-strand breaks in the chromosome, which then paradoxically disappear during the RED phase (7, 16). Second (and in contrast to the reports mentioned above of constant chromosomal DNA amount during T-starvation) (15, 18–20), we have found that during the resistance phase the amount of the chromosomal DNA actually increases ∼1.5 times over the prestarvation level, but then the chromosomal DNA is apparently destabilized during the RED phase, since it is slowly reduced to the original level (16) (Fig. 1 A, Bottom). Therefore, both the apparent chromosomal replication and the significant chromosome fragmentation during the resistance phase could lead to accumulation of chromosomal damage (SOS induction is an indicator of this accumulation) (7).

On the other hand, the early DNA synthesis and the resistance phase in T-starved cells could reflect the existence of a source of dT, available early on during T-starvation, that fuels the initial DNA accumulation and delays viability loss until this pool is exhausted. In other words, the resistance phase could simply postpone TLD, rather than being an integral part of it. Previously, we have tested the two obvious high-molecular-weight (HMW) dT sources, namely, the stable RNAs and the chromosomal DNA, but found that incapacitation of neither one reduced the resistance phase or precluded the early DNA synthesis during T-starvation (16). Thus, the question of whether the resistance phase is a part of the TLD phenomenon remains unresolved.

In the current study, we investigated a seemingly remote possibility of a substantial low-molecular-weight (LMW)-dT pool supporting the resistance phase of T-starvation in E. coli. While the bulk of dTTP in E. coli immediately incorporates into the chromosomal DNA, a fraction of dTTP is recruited into the dTDP-hexose pool (23), to participate in the synthesis of the exopolysaccharide (EPS) capsule, made of core lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (24), O-antigen (OA) (25), and enterobacterial common antigen (ECA) in E. coli (26). The first step of this recruitment is to conjugate dTTP with glucose; the hexose moiety of the resulting dTDP-glucose then undergoes several modifications, before eventually incorporating into oligosaccharide precursors of the outer antigens, while the activating dTDP handle is released back into the DNA precursor pools (26). We ignored LMW dT before because, if the total dT content of the chromosomal DNA is taken for 100%, the pool of dTTP constitutes ∼0.7% of it, while dTDP-glucose (unresolved from other dTDP-hexoses?) adds only another 2.4% (27). No more LMW-dT species are known in the cell, so the total expected LMW-dT pool comes to ∼3% of the total dT content of the chromosomal DNA, not nearly enough to support the resistance phase with its ∼50% increase in the chromosomal DNA mass (Fig. 1A).

To investigate the role of the LMW-dT pool in TLD, we started by developing a simple protocol to extract the LMW-dT pool from growing cells and to compare it to the (HMW) chromosomal dT content. Here we show that early on during T-starvation the pool of dTDP-sugars becomes the major source of dTTP for the chromosomal DNA replication. This unexpected rebalancing of the dTTP pool with the help of cell envelope metabolism delays TLD and prevents T-hyperstarvation, a significantly more lethal phenomenon accompanied by complete chromosome destruction and cell lysis.

Results

E. coli Possesses a Substantial LMW-dT Pool.

As explained in the introduction, we expected the overall LMW-dT pools in E. coli to be ∼3% of the total dT content of the chromosomal DNA. To facilitate comparison of the overall LMW-dT pool inside the cells to the chromosomal DNA dT content of the same cells, we utilized the standard “3H-dT incorporation into the chromosomal DNA” technique, but in addition to collecting labeled cells on the filter (HMW dT), we also collected and quantified the released LMW flow-through and then related its 3H label to the 3H-DNA label retained on the filter.

To chronically label thyA mutants with 3H-dT, we grew these cells in lysogeny broth (LB), as LB contains enough dT to support limited growth of thyA mutant, but not enough to prevent 3H-dT labeling (28). The LMW 3H-dT is separated from HMW 3H-dT by permeabilizing cells with cold 50% methanol to facilitate efficient metabolite extraction (a standard metabolome isolation protocol) (29), while trapping HMW species (proteins, nucleic acids) inside the cell envelope (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Upon subsequent filtration, the HMW-dT of the chromosomal DNA is retained on the filter within cells, while the LMW-dT pool is collected as the flow-through (subsequently also dried on the filter, to equalize the counting conditions). Agarose gel electrophoresis and DNase/RNase digestion reveal chromosomal DNA and long (mostly ribosomal) RNA in the HMW (filter) fraction, while revealing no DNA and some short RNA in the LMW (flow-through) fractions, most of this short RNA material coming from the growth medium itself (Fig. 1C).

Taking the chromosomal dT content (HMW dT) for 100%, we found that in the exponentially growing thyA mutant cultures just before T-starvation the size of the LMW-dT pool equals ∼60% of the chromosomal DNA dT content instead of the expected ∼3% (Fig. 1D and SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). The parental ThyA+ strain has the same size of the LMW-dT pool and starts shrinking it as the cultures grow slower at higher densities (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C).

In order to see whether this 20-fold higher-than-expected pool of endogenous LMW dT is accessible to support chromosomal replication during T-starvation, we followed its changes in the T-starved cells. At the end of the resistance phase of T-starvation, the LMW-dT fraction falls to ∼20% of the chromosomal dT content (Fig. 1D), suggesting that at least two-thirds of this LMW dT is presumably utilized for chromosomal replication during this period, which may explain the DNA accumulation and constant viability during the resistance phase of T-starvation (Fig. 1A). This fraction of LMW dT remains at similar levels thereafter (Fig. 1D). In the ThyA+ parent, the LMW 3H-dT is similarly incompletely chased with unlabeled endogenous dT (SI Appendix, Fig. S1D), showing that at least ∼70% (and maybe up to 95%, see below) of dT can be extracted out of the LMW-dT pool in E. coli.

The thyA Mutants Lacking dTDP-Glucose Develop Envelope Stress in the Absence of dT.

Our finding of the considerable LMW-dT pool in E. coli and its two-thirds reduction during the resistance phase of T-starvation raised the question about its nature. It could not be mostly dTTP, as the DNA precursor pools are reported to be around 1% of the nucleotide contents of the chromosomal DNA (27). What remained was the pool of dTDP-hexoses and the unknown pool of derived oligosaccharide precursors of the outer antigens (23).

E. coli uses dTDP-hexoses in the synthesis of OA and ECA—the two constituents of the EPS capsule of gram-negative cells (25, 26). Two supposedly redundant dTDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase enzymes (see for example ref. 30), encoded by paralogous rfbA and rffH genes in E. coli (31), synthesize dTDP-glucose, which is the first intermediate for dTDP-conjugated hexoses to be integrated in both OA and ECA (Fig. 2A) (32, 33). E. coli K12 background that we use lacks OA and synthesizes only ECA (34); after several modifications the hexose part of the conjugate is deposited on the growing ECA-sugar chain in the inner membrane, while dTDP is phosphorylated to dTTP and returns to the DNA precursor pools (Fig. 2A) (35). The EPS-capsule synthesis is a significant endeavor in growing cells (the dry weight of the combined lipopolysaccharide exceeds the one of the chromosome) (36) and apparently demands an adequate pool of dTDP-hexoses, potentially explaining the substantial size of the LMW-dT pool we detect.

Fig. 2.

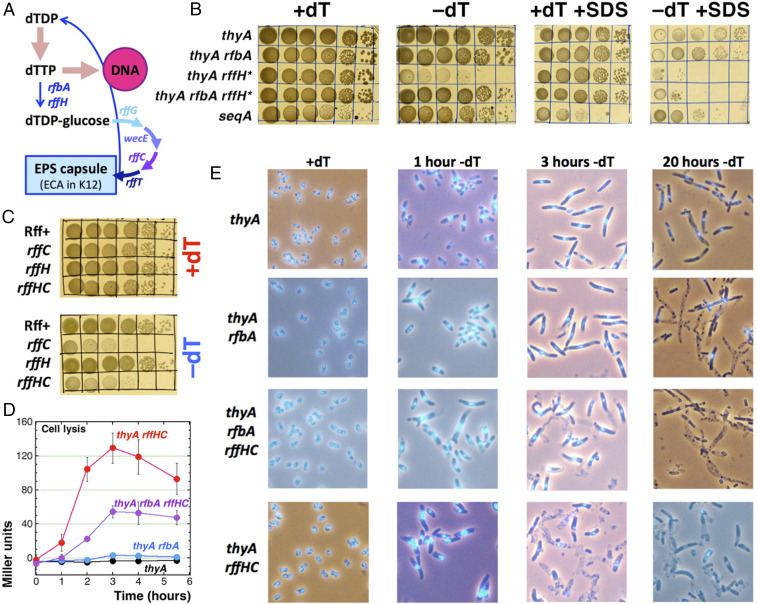

The T-hyperstarvation in the thyA rfbA rffHC and thyA rffHC mutants leads to cell lysis. (A) Scheme of dTTP pool partitioning into the chromosomal DNA (by DNA synthesis) vs. the pool of dTDP-glucose (by RfbA and RffH dTDP-glucose pyrophosphporylases). dTDP-glucose is converted into precursors for the EPS-capsule synthesis, while dTDP is returned to the DNA precursor pool by RffT. The rffG, wecE, rffC, and rffT genes are specific to the ECA-synthesis pathway. (B) Spotting of serial dilutions of thyA (KKW58), thyA rfbA (RA48), thyA rffH* (RA49), and thyA rfbA rffH* (RA51) mutants on LB ± dT ± 1.5% SDS. The seqA mutant (ER15) spotting is shown as a control for SDS sensitivity. (C) The T-starvation hypersensitivity phenotype of the thyA rffHC mutant is due to the rffC defect, rather than rffH defect. The thyA mutant strains are: Rff+, KKW58; rffC, RA57; rffH, RA60; and rffHC, RA50. (D) Cell lysis, measured as leakage of the cytoplasmic enzyme beta-galactosidase out of the cell, in liquid M9CAA cultures in the absence of dT. Thymidine was removed at time = 0. Strains are as in B. (E) DAPI staining of the strains in B undergoing T-starvation for 0, 1, 3, or 20 h.

The rfbA and rffH mutations that we P1-transduced into our thyA mutant were precise deletions from the Keio collection (37). We later discovered that the rffH deletion allele had an inadvertent second mutation; therefore, until its nature is revealed in the next section, we will refer to this allele as rffH*.

The complete defect in dTDP-glucose production should destabilize the EPS capsule, as even (ThyA+) rfbA and rffH single mutants already exhibit sensitivity to surfactants, like sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and bile salts (32, 38). However, on LB +SDS +dT, all four combinations in the ∆thyA background grew almost equally well (Fig. 2B), indicating no obvious envelope problems (while the seqA mutant, our positive control for SDS sensitivity, was characteristically inhibited) (39). In contrast, on LB +SDS −dT, the thyA and especially thyA rfbA mutants were visibly inhibited, as if the limited dT affected their envelope stability, while both thyA rffH* and thyA rfbA rffH* could not form colonies (Fig. 2B), indicating that exogenous dT was critical for their envelope stability. We conclude that, in the absence of dT, all thyA mutants become sensitive to SDS, suggesting cell envelope vulnerability, while the defect in dTDP-glucose pyrophosphorylases further increases this sensitivity.

We want to stress that the thyA rfbA, the thyA rffH*, and the thyA rfbA rffH* mutants all grew without problem and obvious phenotypes on LB +dT (Fig. 2B). Оn LB −dT, thyA and thyA rfbA mutants also grew normally (LB has enough of its own dT), and thyA rfbA rffH* mutant formed smaller colonies, as expected from its supposedly defective envelope. However, the (RfbA+) thyA rffH* mutant surprisingly struggled (Fig. 2B), as if RffH was more than just a redundant paralog of RfbA, or the mutant had an additional defect causing hypersensitivity to T-starvation.

The thyA rffC Mutant Is Hypersensitive to T-Starvation.

The extreme sensitivity of the thyA rffH* and thyA rfbA rffH* mutants to detergents, further confirmed by their poor plating on MacConkey agar ±dT (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) (MacConkey instead of SDS contains bile salts), and the hypersensitivity of the thyA rffH* mutant to T-starvation made us look for possible downstream effects of our precise rffH deletion. It turned out that the downstream rffC gene overlaps the upstream rffH by 22 bp, so a complete rffH deletion also removes the beginning of the rffC gene, making it effectively rffHC two-gene inactivation (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). In fact, deletion of rffC makes the thyA mutant grow poorly on LB −dT, just like the original ∆rffHC (=rffH*) allele does (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B, the “vector” variants). Moreover, complementation of the rffHC and rffC mutants with plasmids carrying either rffH+ or rffC+ genes confirms that it is the rffC+ plasmid, rather than rffH+ plasmid, that complements the T-hyperstarvation of both mutants (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). Finally, in contrast to T-hyperstarvation of the original thyA rffHC or the new thyA rffC mutations, the shorter rffH deletion that does not disrupt the rffC gene (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A) allows the thyA mutant to grow without problem on LB −dT (Fig. 2C), establishing the rffC defect as the one responsible for the hypersensitivity to T-starvation of the rffHC mutants.

The product of the rffC gene is dTDP-fucosamine acetyltransferase that catalyzes the penultimate step in the dTDP-hexose modification (Fig. 2A) before the modified hexose joins the trisaccharide repeats (ECA lipid III), from which ECA itself is assembled, and so the rffC mutant accumulates its precursor, ECA lipid II (35) (see Fig. 5A below). Our further analysis has revealed that the rffH mutation has no T-starvation phenotypes, unless combined with the rfbA defect; for example, the thyA rfbA rffH combination grows slowly on LB −dT and is additionally inhibited by SDS (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). At the same time, the complete inability of the double rfbA rffH mutant to make dTDP-glucose blocks the pathway in which RffC later acts (Fig. 2A), making the double rfbA rffH defect epistatic to (masking) the thyA rffC mutant hypersensitivity to T-starvation (compare Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Since by the time we have established it is the rffC defect that causes hypersensitivity to T-starvation of the original thyA rffH* mutant, the bulk of our data were already collected with the thyA rffHC and thyA rfbA rffHC strains, we continue to present these results, verifying the key findings in the thyA rffC (RffH+) and thyA rfbA rffH (RffC+) mutants. In interpreting these results, it helps to remember that whenever RfbA is functional, the thyA rffHC mutant displays TLD phenotypes of the thyA rffC mutant, whereas whenever RfbA is inactivated, the resulting thyA rfbA rffHC mutant displays TLD phenotypes of the thyA rfbA rffH mutant.

The thyA rffHC and thyA rfbA rffHC Mutants Lyse during T-Starvation.

The thyA mutants undergo one cell division during T-starvation, revealed by direct cell count under a light microscope (16). In contrast, the thyA rfbA, thyA rffHC, and thyA rfbA rffHC mutants failed to divide even once, when incubated in liquid cultures without dT (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Also, we noticed that the thyA rffHC and thyA rfbA rffHC mutant cells appeared “lighter” in phase contrast at later time points, and some of the cells exhibited what looked like segmental cytoplasm voids (see below).

To test for possible cell lysis in T-starved cultures of the four mutants, we measured the extracellular presence of the cytoplasmic enzyme beta-galactosidase (40, 41). We detected no or little cell lysis in the thyA and thyA rfbA mutants (at least during the first 6 h of T-starvation), but a significant cell lysis within 2 h of T-starvation in the thyA rffHC mutant (Fig. 2D) (at the peak amounting to ∼50% of the total cellular beta-galactosidase content, see below). As expected from the pathway configuration (Fig. 2A), this lysis was partially suppressed in the thyA rfbA rffHC mutant (Fig. 2D), the incomplete nature of the suppression reflecting the sensitivity to T-starvation of the double rfbA rffH defect itself (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). As we detected no phage in the supernatants of the T-starved thyA rffHC mutant cultures, this cell lysis was not due to prophage induction. We conclude that the loss of the RffC enzyme makes the thyA mutant cell envelope hypersensitive to T-starvation; in contrast, the loss of both RfbA and RffH enzymes sensitizes cells to T-starvation to a lesser extent, while at the same time suppressing the rffC defect by shutting down the ECA-biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 2A).

DAPI Staining Visualizes the Second Dimension of TLD at Three Severity Levels.

The dramatic cytoplasm and cell envelope instability phenotypes of the thyA rfbA rffHC and thyA rffHC mutants during T-starvation made us wonder whether the thyA single mutant undergoes similar changes, perhaps on a lesser scale. Still, the test for the periplasm instability using alkaline phosphatase (40, 41) showed no periplasm leaking in the T-starved thyA mutants; as a positive control, a massive release of this periplasmic enzyme was evident in the T-starved thyA rffHC mutant cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

Fluorescent microscopy of DAPI-stained cells detects gross cytoplasm, envelope, and chromosome stability issues. When grown in the presence of dT, thyA mutant cells were expectedly small and dividing normally (Fig. 2 E, Top row). After 1 h of T-starvation, the cells became ∼1.5 times wider and 2 to 3 times more elongated, with centrally positioned bright nucleoids. After 3 h of T-starvation, the thyA mutant cells mostly kept their new width, but became 4 to 6 times longer than nonstarved cells, with centrally positioned single nucleoid and somewhat mottled cytoplasm (developing lighter segments), but still no signs of cell lysis (Fig. 2E), similar to the report before (42). Others report that live cell imaging of E. coli strains defective in their envelope maintenance present the retraction of cytoplasm as a highly dynamic event, accompanied by vesicle release (43, 44). Interestingly, after 20 h of T-starvation, the thyA mutant cells developed sickly appearance: they were further elongated, with segmental cytoplasm loss in at least half of the cells, with no DNA in the majority of cells and with little DNA remaining in a few still centrally located surviving nucleoids (Fig. 2 E, Top row). However, T-starved cultures would be long stabilized at that time in the “survival” phase (7, 16), so these dramatic changes were likely reflecting metabolic decomposition of long-dead cells. We conclude that, during the RED phase (2 to 5 h under our conditions), T-starved thyA mutant cells develop some cytoplasm irregularities, but no cell lysis or even periplasm leakage. However, this was not true for the rfbA rffHC and rffHC mutants.

When grown in the presence of dT, cells of all four strains (thyA, thyA rfbA, thyA rffHC, and thyA rfbA rffHC) were similarly small and dividing normally (Fig. 2 E, Leftmost column). The thyA rfbA mutant progressed through T-starvation similar to the thyA single mutant, although cells appeared more mottled at 3 h of T-starvation, and half of the cells turned to “ghosts” completely lacking cytoplasm after 20 h of T-starvation (Fig. 2 E, Second row). As expected, the thyA rfbA rffHC mutant cells were more affected by T-starvation, compared to the thyA rfbA mutant, showing some lysis at 3 h of T-starvation and almost complete cytoplasm loss after 20 h of T-starvation (Fig. 2 E, Third row). Finally, the T-starved thyA rffHC mutant cells, looking somewhat wider even in the presence of dT (in agreement with the reported measurements of ECA lipid II-accumulating mutants) (45), became extra wide after 1 h of T-starvation and developed huge central nucleoids (Fig. 2 E, Bottom row). Corroborating the cell lysis measurements (Fig. 2D), by 3 h of T-starvation most of the thyA rffHC mutant cells lost cytoplasm, and the resulting ghosts had little DNA (Fig. 2 E, Bottom row).

Our investigations in the ECA-defective mutants so far revealed a previously unknown dimension of T-starvation affecting the cytoplasm dynamics and envelope stability within the standard time frame of TLD (the first 6 h of T-starvation). Specifically, the cytoplasm and envelope effects of T-starvation distinguish at least three severity levels of TLD: 1) the mildest one in the thyA and thyA rfbA mutants; 2) the severe T-starvation associated with significant lysis in the thyA rfbA rffHC mutant, likely due to lack of dTDP-glucose synthesis; and 3) the T-hyperstarvation in the thyA rffHC mutant displaying massive lysis, likely due to accumulation of ECA lipid II. Next we compared the size and dynamics of the LMW-dT pools, as well as the TLD parameters in the thyA rfbA rffHC vs. thyA rffHC mutants.

RfbA and RffH Recruit dTTP into the LMW-dT Pool.

Since both RfbA and RffH were supposed to contribute to the dTDP-glucose pool (31–33), we expected the size of the LMW-dT pool to be smaller when both enzymes are inactivated. Indeed, we found that, in contrast to 60% of the chromosomal dT content in the thyA mutant, the LMW-dT pool is less than 1.5% of the chromosomal dT content in the thyA rfbA rffH (RffC+) mutant, increasing slightly during T-starvation (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, we found only slightly higher numbers (∼3%) and similar evolution of the pool in the thyA rfbA mutant (Fig. 3A), suggesting that RfbA is the major contributor to dTDP-glucose synthesis. In contrast, in the thyA rffH mutant the pool was still about half of the one in thyA mutant and it did not go much lower during T-starvation (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the still functional RfbA was actively rebuilding it even without exogenous dT. We conclude that: 1) dTDP-glucose and its derivatives make >95% of the overall LMW-dT pool in the thyA mutant; and 2) this pool is accessible to the cell and is used during T-starvation.

Fig. 3.

RfbA and RffH build the LMW-dT pool that supports DNA synthesis during the resistance phase of TLD. The strains are thyA (KKW58), thyA rfbA (RA48), thyA rffH (RA60), thyA rfbA rffHC (RA51), and thyA rfbA rffH (RA65) mutants. (A) The evolution of LMW-dT pools in the thyA rfbA, thyA rffH, and thyA rfbA rffH mutants during T-starvation. Thymidine was removed at time = 0, after which aliquots were taken for the “0-h” cultures. Values for thyA mutant from Fig. 1D are for comparison. (B) Time course of TLD in the thyA, thyA rfbA, thyA rfbA rffHC, and thyA rfbA rffH (RffC+) mutants. (C) Time course of TLD in the thyA and thyA rffH mutants. (D) Loss of chromosomal DNA in the thyA, thyA rfbA, and thyA rfbA rffHC mutants during T-starvation. (E) Change over time of the absolute amounts of replication origin DNA in the thyA, thyA rfbA, and thyA rfbA rffHC mutants during T-starvation. (F) Same as in D, but for the terminus. (G) The current model of RfbA + RffH vs. ECA-synthesis action in thyA mutants in two growth conditions: with dT supplementation (Top) or during the resistance phase of T-starvation (Bottom).

LMW-dT Pool Supports DNA Synthesis during the Resistance Phase, Delaying and Alleviating TLD.

Not only the LMW-dT pool is all but eliminated in the thyA rfbA and thyA rfbA rffH mutants (Fig. 3A), but the thyA rfbA rffHC and thyA rfbA rffH (RffC+) mutants have shorter resistance phases and die deeper during the RED phase, while the thyA rfbA mutant only has a deeper RED phase (Fig. 3B). At the same time, the thyA rffH mutant is no more sensitive to T-starvation than the thyA mutant (Fig. 3C). In other words, the LMW-dT pool supports at least part of the resistance phase of TLD and prevents an even deeper RED phase.

Confirming the recently published results (16, 22) (Fig. 1A), DNA amount initially increased ∼1.5 times during the resistance phase in the thyA mutant before slowly declining during the RED phase (Fig. 3D). In contrast, both thyA rfbA rffHC and thyA rfbA mutants fail to accumulate chromosomal DNA early on upon T-starvation, even though later their chromosomal DNA disappearance parallels the one in thyA mutant cells (Fig. 3D). Thus, the LMW-dT pool indeed supports the initial chromosomal DNA accumulation in T-starved cells.

By monitoring the copy number of the origin and the terminus of the chromosome, we characterize the dynamics of chromosomal DNA replication and loss during T-starvation (16). Indeed, increase in the amount of origin DNA registers initiations of the chromosomal replication, while increase in the amount of the terminus indicates completion of the chromosomal replication, reflecting the general progress of replication forks. As reported before, the thyA mutants show robust replication initiation during the resistance phase, followed by origin-containing chromosomal domain destruction during the RED phase (Fig. 3E) (8, 15, 17). The initial terminus’ 1.5-times increase in the thyA mutants indicates successful termination of the prestarvation replication forks during the resistance phase, before the RED phase ushers gradual chromosomal DNA loss (Fig. 3F) (15, 16, 22). We found that both the origin and the terminus copy number show only a limited initial increase in the thyA rfbA rffHC and thyA rfbA mutants (Fig. 3 E and F), indicating both decreased initiation from the replication origin and decreased overall progress of replication forks. At this point, we conclude that the two paralogous dTDP-glucose pyrophosphorylases, RfbA with the help of RffH, are responsible for the bulk of the LMW-dT pool in E. coli, which is employed in the EPS synthesis. In the thyA mutants, this LMW-dT pool maintains cell viability through the resistance phase of TLD by supporting the shrinking dTTP pool and, via this, the initial chromosome replication (Fig. 3G), in effect, postponing the onset of acute T-starvation.

RffC Helps to Extract dTTP out of the LMW-dT Pool during T-Starvation.

The severe growth defect of the thyA rffC and thyA rffHC mutants on LB without dT (Fig. 2 B and C) and lysis of the latter during T-starvation (Fig. 2 D and E) suggested that RffC function becomes critical for the dTTP <<—>> dTDP-hexose equilibrium during the resistance phase of TLD. The (partial) suppression of both phenotypes in the thyA rfbA rffHC mutant (Figs. 2 B and D and 3) meant that the rffC mutants are poisoned by functional RfbA and RffH, consistent with RffC action facilitating the release of dTDP from dTDP-hexose conjugates (Fig. 2A).

We found that the LMW-dT pool in the thyA rffHC mutant is similar to the one in the thyA mutant during exponential growth; however, in contrast to it shrinking in thyA, the LMW-dT pool in the thyA rffHC mutant significantly expands during T-starvation (Fig. 4A), perhaps reflecting dT redistribution from the degraded chromosomal DNA? The thyA rffC (RffH+) mutant showed higher initial LMW-dT pools and even more dramatic expansion during T-starvation (SI Appendix, Fig. S8A). Thus, RffC action has no adverse LMW-dT effect during growth in the presence of dT, while during T-starvation it helps extract dTTP from the RfbA+RffH-made LMW-dT pool, returning it back to the DNA precursor pools (Figs. 2A and 3G). However, before securing this conclusion, we had to address an obvious caveat about the rfbA, rffH, and rffC defects.

Fig. 4.

RffC helps to extract dTTP out of the LMW-dT pool during T-starvation. The strains are thyA (KKW58), thyA rfbA (RA48), thyA rffHC (RA49), and thyA rfbA rffHC (RA51). (A) The evolution of LMW-dT pools in the thyA rffHC mutant during T-starvation (the red bars). Thymidine was removed at time = 0, after taking aliquots for the 0-h cultures. Values for thyA mutant (black bars) from Fig. 1D are for comparison. (B) Scheme of separation of the intracellular uridine into HMW rU (the rU content of the cellular RNA, mostly ribosomes) and LMW rU (nucleotides and sugar conjugates). (C) The size of the LMW-rU pool, normalized to the HMW-rU content of the cellular RNA, either during normal growth in dT-supplemented medium or after 3 h of T-starvation. (D) Time course of TLD in the thyA rffHC mutant. In D and E, the thyA rfbA rffHC mutant curve is shown to illustrate partial suppression. (E) Loss of the chromosomal DNA absolute amounts in the thyA rffHC mutants during T-starvation. (F) Loss of the replication origin and terminus DNA in the thyA rffHC mutant during T-starvation. (G) Cell lysis upon T-starvation in the thyA rffHC mutant cultures at various temperatures. In contrast to Fig. 2D, where lysis was expressed in Miller units, here lysis is expressed as percentage of the total cellular content of beta-galactosidase, which undergoes its own peculiar kinetics during T-starvation (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). (H) Time course of TLD in the thyA rffHC mutant cultures at the same temperatures as in G.

Since on the one hand these mutations affect the cell envelope integrity, while on the other hand they also impact the LMW-dT pools, they could potentially do the latter by modifying either the nucleoside transport into the cell, or the release of LMW species from the cell. To detect these possible nonspecific effects of rfbA, rffH, and rffC mutations, we applied our HMW/LMW separation protocol (Fig. 1B) to measure the distribution of 3H-uracil between HMW-rU content (cellular RNA) and LMW-rU pool (made of the RNA precursor UTP and EPS-capsule precursors UDP-sugars) in these mutants (Fig. 4B). We found that all four strains of the set have about the same ratio of LMW rU to the total HMW rU (∼8%), whether exponentially growing or after 3 h of T-starvation (Fig. 4C). In other words, the rfbA and rffHC mutations do not affect the HMW/LMW balance of uracil pools, making it unlikely that the dramatic effects of these mutations on the HMW/LMW balance of dT pools are due to nonspecific changes in permeability of the cell envelope. Thus, our overall conclusion is that, while RfbA and RffH recruit dTTP into the LMW-dT pools, RffC helps “extract” dTTP out of these pools, which becomes critical during T-starvation (Fig. 3G).

Inability to Release dTTP from the LMW-dT Pool Results in T-Hyperstarvation.

If RffC helps extracting dTTP from LMW-dT pools during T-starvation, its inactivation should exacerbate the TLD phenotypes. Indeed, we found that the thyA rffC and thyA rffHC mutants completely lack the resistance phase and develop the dramatically deeper RED phase (Fig. 4D and SI Appendix, Fig. S9) reminiscent of the thyA recBCD mutants (7, 16, and see below). The better survival of the thyA rfbA rffHC mutant compared to the (RfbA+) thyA rffHC mutant (Fig. 4D) confirms RfbA+RffH toxicity in the thyA rffC mutant, likely resulting from the continuous sequestration of dTTP into the LMW-dT pool by dTDP-glucose synthases even during T-starvation (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S8 A and B).

Change in the chromosomal DNA amounts during T-starvation (Fig. 1A) is also dramatically different in the thyA rffHC mutant. In contrast to the significant initial chromosomal DNA replication of the thyA mutant or even the initially flat profile of the thyA rfbA and thyA rfbA rffHC mutants (Fig. 3D), the chromosomal DNA of the thyA rffC and thyA rffHC mutants becomes immediately unstable upon thymidine removal, with more than one-third of it already gone after 1 h of T-starvation and only 10% of the starting amount remaining by 4 h of T-starvation (Fig. 4E and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Moreover, this chromosomal DNA disappearance in the thyA rffHC mutant affects equally and dramatically both the origin and the terminus (Fig. 4F), suggesting catastrophic loss of the entire chromosome. The instability of the chromosomal DNA in the thyA rffHC mutant is again partially suppressed by RfbA inactivation (Fig. 4E).

We conclude that during T-starvation there is a tug-of-war between RfbA+RffH on the one hand and RffC on the other, the former continuously sequestering dTTP into the LMW-dT pool and thus aggravating TLD, while the latter releasing dTTP from this pool, therefore alleviating TLD.

Does Cell Lysis Drive the T-Hyperstarvation Phenomenon?

The lysis of the thyA rffHC mutant cells in response to T-starvation seems like an obvious reason for the catastrophic chromosomal DNA loss and for the absence of the resistance phase in this mutant; yet a closer look shows that these events are separated in time and therefore independent. First, at 1 h of T-starvation, the thyA rffHC cultures suffer little or no lysis (Figs. 2D and 4G and SI Appendix, Fig. S6) and no cytoplasm/envelope irregularities (Fig. 2E), even though only 3% of them remain viable at this point (Fig. 4 D and H), and at the population level they have already lost 36% of their genomic DNA (Fig. 4E) and ∼50% of the replication origin and terminus DNA (Fig. 4F). Second, from quantification of beta-galactosidase release, lysis affects less than half of the T-starved thyA rffHC cells (Fig. 4G), whereas their general survival is below 10e-4 (Fig. 4 D and H). Finally, lysis of the thyA rffHC mutants is strongly suppressed during T-starvation at 28 °C (Fig. 4G), whereas TLD, although also reduced, still reaches 10e-3 at this temperature (Fig. 4H). Thus, lysis of the thyA rffHC mutants without dT, even though significant at 37 °C at 2 h of T-starvation, must be a later event separate from their immediate lethality and chromosomal DNA loss.

T-Hyperstarvation in Other Mutants That Cannot Finish ECA Synthesis.

ECA synthesis up to lipid III is a multistep three-branch process (Fig. 5A). As we have shown, blocking initiation of its dTDP branch with the rfbA rffH double defect exacerbates TLD via reducing the LMW-dT pool (Fig. 3). We have also found that T-hyperstarvation in the thyA mutants, caused by blocking the completion of this branch with the rffC defect that prevents the release of dTDP from the LMW-dT pool, causes hyper-TLD: rapid death due to chromosome destruction and cell lysis (Fig. 4). If the lack of dTDP release from the ECA synthesis pathway was indeed the reason for hyper-TLD of the thyA rffC mutants, then any other mutation in ECA synthesis that blocks dTDP release should also make thyA mutants hypersensitive to T-starvation. Indeed, spotting on an “enhanced” LB reveals that, like the rffC defect, addition of the rfe, rffM, or rffT defects makes the thyA mutants grow poorly without dT, with the thyA rffT mutant essentially copying the behavior of the thyA rffC mutant (Fig. 5B), which makes sense from the ECA biosynthesis scheme (Fig. 5A). In the standard TLD assay, blocking the other branch of ECA synthesis that converges with the dTDP branch with either rfe, rffM, or rffT defects makes the thyA mutants hypersensitive to T-starvation (Fig. 5C). Thus, dTTP release from the LMW-dT pool could be the common denominator of the various degrees of the T-hyperstarvation phenotype of all these mutants that synthesize dTDP-glucose but cannot finish the ECA synthesis.

Fig. 5.

Hyper-TLD is observed in other ECA-defective mutants and is independent of DNA replication. The strains are thyA (KKW58), thyA rffHC (RA49), thyA dnaA46(Ts) (KJK170), thyA dnaA601(Ts) (SRK291), thyA (SOS) (RA66), thyA dnaA46(Ts) (SOS) (RA67), thyA dnaA46(Ts) rffHC (RA53), thyA dnaA601(Ts) rffHC (RA54), thyA rfe (RA61), thyA rffM (RA63), and thyA rffT (RA62). (A) Scheme of ECA biosynthesis up to lipid III. The relevant genes are in color: rfbA and rffH are blue, rffC is red, while rfe, rffM, and rffT are purple. (B) Spotting of serial dilutions of the indicated mutants on LB2xYE ±dT. (C) Time course of TLD in the thyA rfe, thyA rffM, and thyA rffT mutants. Note that the control thyA strain was dying shallower in this set. (D) The standard T-starvation protocol compared to the awakening protocol, used in E–H. (E) Time course of TLD at 42 °C of the thyA and thyA dnaA46(Ts) mutants in the awakening protocol. The same cultures are also diluted into the fresh medium +dT, to show the dnaA(Ts) growth defect. (F) No SOS induction in the thyA dnaA(Ts) (SOS) mutants supplemented with dT at 42 °C. Strains were grown at 28 °C and switched to 42 °C ±dT at time = 0. The thyA (SOS) mutant +dT provides a negative control, while the robust SOS induction in the –dT conditions in the two strains provides a positive control. (G) Time course of TLD at 42 °C in the dnaA46(Ts) and dnaA601(Ts) variants of either the thyA mutant (black lines) or thyA rffHC mutant (red lines). (H) Loss of the chromosomal DNA during T-starvation at 42 °C in the dnaA46(Ts) and dnaA601(Ts) variants of either the thyA mutant (black lines) or thyA rffHC mutant (red lines).

Hyper-TLD of the thyA rffHC Mutant Is Independent of Replication and Endo I.

Finding mutants that cannot finish their ECA synthesis and thus undergo faster death upon T-starvation—while establishing that the resistance phase is not an integral part of TLD—posed the question about the nature of the accompanying catastrophic chromosomal DNA loss, which we observed in the thyA rff(H)C mutants (Fig. 4 E and F and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). TLD was always considered a chromosomal replication-centered phenomenon (1, 5), but we have recently demonstrated a surprising TLD independence of the chromosomal replication (22). For this, we used the “awakening protocol” to eliminate all of the replication activity in the chromosome by bringing dT-supplemented cultures of the thyA dnaA(Ts) mutants to saturation at the permissive temperature and then outgrowing (awakening) them without dT at the nonpermissive temperature of 42 °C (Fig. 5D) (22). Because of the nonpermissive temperature, the thyA dnaA(Ts) mutant cannot initiate replication of its chromosome even in the presence of dT and remains static (Fig. 5E). At the same time, in accord with our previous conclusion about replication independence of TLD, in the absence of dT this thyA dnaA mutant undergoes exactly the same death as its DnaA+ progenitor (Fig. 5E).

Since SOS induction significantly contributes to TLD (8, 9), if the inability to initiate replication from the origin also induces SOS, the observed TLD in the thyA dnaA(Ts) mutant at 42 °C could be due to this SOS induction even in the absence of chromosomal DNA replication. However, we found that the thyA dnaA(Ts) mutants do not induce the SOS response at 42 °C, as long as they are supplemented with dT, while undergoing strong SOS induction in both the standard (SI Appendix, Fig. S11) and the awakening protocols of T-starvation (Fig. 5F). The latter result indicates replication independence of the SOS-inducing chromosomal lesions during T-starvation. We also report that in the same awakening protocol blocking chromosomal replication, the thyA rffHC dnaA(Ts) mutants die with somewhat deeper kinetics compared to the thyA rffHC mutant (Fig. 5G). Thus, the hyper-TLD in the thyA rffHC mutants is also independent of DNA replication.

As already reported (22), in contrast to the standard T-starvation protocol (Fig. 5D), in the awakening protocol at 42 °C the thyA mutant suffers significant chromosomal DNA loss, independently of its dnaA status (compare Fig. 3D vs. Fig. 5H). Although for the thyA rffHC mutant in the awakening protocol at 42 °C the massive chromosomal DNA loss is slightly delayed, its overall kinetics is hardly affected (if a bit accelerated) by the dnaA(Ts) defects (Fig. 5H), indicating that the catastrophic chromosomal DNA loss due to the rffC defect is also completely replication independent.

Following the recent report of Endo I-catalyzed massive chromosomal DNA fragmentation during slow lysis of cells in agarose plugs (46), we tested whether the fast chromosomal DNA disappearance in the thyA rffHC mutants is due to Endo I gaining access to the chromosomal DNA during lysis, but the DNA loss turned out to be Endo-I independent (SI Appendix, Fig. S12A). Also, the endA inactivation failed to affect TLD kinetics of both the thyA and thyA rffHC mutant (SI Appendix, Fig. S12B).

Chromosome Is the Primary Target of TLD in the thyA rffHC Mutant.

The most likely candidate for an enzyme capable of such a rapid chromosomal DNA degradation is the RecBCD helicase/nuclease (47), yet the catastrophic chromosomal DNA loss in the thyA rffHC recBCD mutant is only slightly slower than in its RecBCD+ parent (Fig. 6A), suggesting that only a minor fraction of the chromosomal DNA of the T-starved thyA rffHC mutant is lost to the linear DNA degradation by RecBCD. As already mentioned, the hyper-TLD in the thyA rffHC mutant is reminiscent of the hyper-TLD observed in the thyA recBCD mutant (SI Appendix, Fig. S13), as if RecBCD and RffC work in the same pathway of hyper-TLD prevention. Interestingly, the TLD curve of the combined thyA rffHC recBCD mutant suggests an even deeper defect (SI Appendix, Fig. S13); unfortunately, TLD in the thyA recBCD and thyA rffHC mutants is already too fast in the standard conditions (M9CAA medium) to detect further significant acceleration. To reveal the type of genetic interactions between the two defects, we employed a milder T-starvation in LB, as we did before for the thyA recBCD uvrD combination (7). Under these conditions, the thyA mutant grows ∼10 times before plateauing and then essentially fails to die, the thyA recBCD mutant dies by 2.5 orders of magnitude, while the thyA rffHC mutant dies by 1.5 orders of magnitude (Fig. 6B). Remarkably, the deep TLD of the thyA recBCD rffHC mutant in LB is clearly the product of the individual TLD effects of the recBCD and rffHC mutations (Fig. 6B), indicating independent action of the two strongest TLD-accelerating defects.

Fig. 6.

Chromosome fragmentation in the T-starved thyA rffHC mutant. The strains are thyA (KKW58), thyA rffHC (RA49), thyA recBCD (KJK63), and thyA recBCD rffHC (RA52). (A) Loss of the chromosomal DNA in the thyA recBCD rffHC mutant during T-starvation. (B) Time course of TLD in the thyA, thyA recBCD, thyA rffHC, and thyA recBCD rffHC mutants in LB (compare with SI Appendix, Fig. S13, the same time course, but in the standard conditions). (C) Pulsed-field gel showing kinetics of chromosome fragmentation during T-starvation. A shorter time frame is used because no action happens in thyA and thyA recBCD mutants past 3 h without dT, while the thyA rffHC mutants start lysing after 2 h without dT. CZ, compression zone; LMW, low molecular weight fragments; ∼50 to 200 kbp in size, recB* = recBCD. (D and E) Quantitative kinetics of the chromosomal fragmentation, from several gels as in C. The higher background (time = 0) chromosome fragmentation in the thyA rffHC mutants reflects a peculiar sensitivity of this mutant to centrifugation (used to collect cells before encasing them in agarose plugs). Minimizing the speed of centrifugation minimizes this fragmentation even for thyA rffHC cells still supplemented with dT (as well as for the T-starved cells). (F) Our speculation about the chromosome and cell behavior during T-starvation vs. T-hyperstarvation. The shaded circle represents a cross-section of the cell, in which the chromosomal DNA (blue) is attached to the cell envelope (brown) at certain points (yellow). In the absence of dT, DNA attachment to the envelope is proposed to “freeze.” As a result, during T-starvation, increase in cell volume causes not only envelope thinning, but also chromosomal breakage and limited DNA loss. In contrast, during T-hyperstarvation, a larger increase in cell volume breaks DNA in many places, leading to a complete chromosome loss, while the cell envelope also eventually bursts.

Since the recBCD defect makes cells unable to repair double-strand DNA breaks (reviewed in ref. 48), and assuming that the substrate of the “rffC pathway” is also chromosomal DNA, the independence of the recBCD and rffC pathways (Fig. 6B) predicts a higher chromosomal fragmentation during T-starvation in the thyA rffHC mutants. In the thyA mutants, chromosome fragmentation is induced during the resistance phase of T-starvation but then, counterintuitively, goes away during the RED phase (16) (Fig. 6 C and D). We found that not only thyA rffHC mutants suffer a higher chromosome fragmentation in response to T-starvation, but also this fragmentation stays high (Fig. 6 C and D), even though these cells start lysing around 2 h of T-starvation (Figs. 2D and 4G). In other words, the rffC defect induces more double-strand breaks during T-starvation (it could have also blocked their subsequent repair, but the independence of the rffC and the recBCD mutant effects argues against this formal possibility). Confusingly, when we do block repair of double-strand breaks genetically with the recBCD mutation, chromosomal fragmentation in the thyA recBCD rffHC mutant is suppressed and resembles the smoother fragmentation kinetics of the thyA recBCD mutants (Fig. 6 C and E), as if the RecBCD-promoted linear DNA degradation or repair of double-strand breaks in the thyA rffHC mutant stimulates even more breaks (compare Fig. 6D vs. Fig. 6E).

On the basis of our analysis of T-hyperstarvation phenotypes in the thyA rffHC mutants, we conclude that the resulting hyper-TLD does not require replication forks, but it does massively break chromosomal DNA (independently of Endo I), which explains its synergy with the double-strand DNA break repair defect (recBCD) and is the likely reason for the catastrophic loss of chromosomal DNA.

Discussion

In contrast to typically static responses to amino acid or RNA base starvation in E. coli (2, 49), T-starvation leads to cell death, but not directly. The nature of the two-generations-long resistance phase, followed by the sudden shift to the RED phase (Fig. 1A), has remained a long-standing puzzle of TLD (16). This static period at the beginning of T-starvation, with its significant initiation of DNA replication (15, 16), SOS induction (7, 8, 17), accumulation of ss-gaps, and high levels of chromosomal fragmentation (16), was considered an integral TLD period, when chromosomal damage accumulates to irreparable levels, ushering in the RED phase (1, 5). Here we show that the resistance phase, rather than being a part of TLD, delays acute T-starvation and is supported by dTTP recruitment from the unexpectedly large internal LMW-dT pool. This pool in rapidly growing cells comprises ∼60% of the dT content of the chromosomal DNA; once it is exhausted as a result of T-starvation, the RED phase begins.

While two paralogous thymidine glucose pyrophosphorylases of E. coli, RfbA and RffH, recruit dTTP into the LMW-dT pool, we found that RffC, by facilitating ECA-synthesis completion, releases dTTP from the LMW-dT pool, which becomes critical in the absence of exogenous dT (Fig. 3G). As a result of the reduced LMW-dT pool, the thyA rfbA rffH mutant experiences a shorter resistance phase with no chromosomal DNA accumulation followed by a deeper RED phase. In contrast, TLD in the thyA rffC mutant lacks the resistance phase altogether, leads to a precipitous loss of chromosomal DNA, and ends in massive cell lysis. Moreover, the dramatic phenotypes of the thyA rffC mutant during T-starvation, including cell lysis, were partially suppressed by rfbA+rffH inactivation, confirming that dTDP-glucose synthesis poisons T-starved cells lacking RffC activity, by continuously recruiting the remaining dTTP into the LMW-dT pool.

Hyper-TLD in the thyA rffC mutants is distinct from regular TLD in thyA mutants, or even from hyper-TLD in the thyA recBCD mutants, by causing a complete loss of chromosomal DNA, as well as eventual lysis in half of the cells, suggesting a still unknown role of either LMW dT or the chromosomal DNA in cell envelope maintenance.

The dTDP-Sugar-Utilizing Pathways and the EPS Capsule.

We are not sure how this significant pool of dTDP-sugars avoided detection—maybe because nobody directly compared its size with that of the chromosomal DNA? Its significant size is indirectly confirmed by the similar size of LMW-rU pools (Fig. 4 B and C), which likely are mostly UDP-sugars. Even though LMW-rU pools are only 8% of the total rU content of stable RNA (Fig. 4C), the total mass of cellular RNA is six to seven times larger than that of the chromosomal DNA (27), making the absolute sizes of the two pools similar. Indeed, EPS-capsule synthesis utilizes both dTDP-sugars and UDP-sugars (26). There is still a possibility, though, that the significant LMW-dT pool is K12 specific, because this E. coli background lacks OA (34) and therefore might up-regulate its EPS-capsule production.

Okazaki and Okazaki were the first in the late 1950s to report that the bulk of thymidine internalized by bacteria joins LMW pools as a compound chemically distinct from the DNA precursor dTTP (50), later identified as dTDP-rhamnose (51). By analogy with the already well-known UDP- and GDP-sugar conjugates, Okazaki suggested that dTDP-rhamnose participates in EPS-capsule synthesis (52), but since the dTDP portion of this conjugate was (slowly) chased into DNA (23), he speculated that dTDP-sugars could represent common intermediates for both polysaccharide and DNA synthesis (52).

An enzyme synthesizing dTDP-glucose was soon reported (53), while the pools of dTDP-sugars under various conditions were consistently severalfold higher than the dTTP pool (54–56). Moreover, a faster and deeper TLD was reported in an uncharacterized E. coli mutant deficient in dTDP-glucose synthesis (57). Nevertheless, the original idea of Okazaki and Okazaki about dTDP-sugars as common intermediates for both EPS capsule and DNA replication came full circle only some 60 y later, with this report that the pool of dTDP-sugars becomes the major source of dT for the chromosomal replication during T-starvation.

Is ECA Lipid II Accumulation Poisonous during T-Starvation?

Unexpectedly, the thyA rfbA rffH (RffC+) mutant, which should be deficient for ECA synthesis (essentially leaving our O-minus K12 background (34) without EPS capsule), avoids the most severe TLD. Instead, the thyA rffC mutant develops the worst T-starvation phenotypes. This severity is partially suppressed by the rfbA rffH inactivation, suggesting that it is not the inability to synthesize ECA, which makes the thyA rffC mutant extremely vulnerable to T-starvation.

The loss of wecE, the gene responsible for the step preceding the rffC step in the ECA biosynthesis (Fig. 5A), has been previously shown to lead to the accumulation of ECA lipid II intermediates, which causes membrane instability by diverting the undecaprenol moiety away from use in PG synthesis (45). On the basis of our results, we suspect that the rffC mutants have similar problems. The ECA-synthesis activity that acts after RffC making lipid III and releasing dTDP from dTDP-sugar conjugates is RffT (Fig. 5A), a mutation which also makes the thyA mutant hyper-sensitive to T-starvation (Fig. 5 B and C). The various defects due to inability to finish ECA lipid III synthesis should be suppressed by inactivation of the rfe gene that blocks the accumulation of all ECA lipid intermediates (Fig. 5A); we will be testing this possibility in the future. Remarkably, our findings indicate that accumulation of ECA lipid II becomes toxic only in the absence of dT, suggesting a role for dT in cell envelope maintenance.

The Nature of Chromosomal Damage during T-Starvation.

Since TLD is only observed in growing cultures (22), and since the only critical role of thymidine in the cell was thought to generate the DNA precursor dTTP, faulty chromosomal replication during T-starvation was always considered the primary cause of TLD, the significant effects of recombinational repair defects on TLD kinetics supporting this thinking (6–9). Paradoxically, even though high levels of chromosome fragmentation develop during the resistance phase of TLD, this fragmentation does not directly contribute to lethality in the repair-proficient cells (7, 15, 16). Instead, genetic studies strongly suggested that the main contributor to the chromosome poisoning during T-starvation was the repair of persistent single-strand gaps (6–8, 17), and we have indeed previously reported ss-gap accumulation in the chromosomal DNA during the RED phase (16). Still, the mechanism of T-starvation-induced chromosomal lesions remained unclear.

To explain how thymineless replication translates into irreparable chromosomal lesions, futile cycles of DNA-uracil incorporation/excision were repeatedly proposed to yield irreparable DNA damage during T-starvation (1, 5, 21). However, we found that dUTP concentrations are too low in the Dut+ cells to support futile DNA-uracil incorporation/excision cycles (16). Even preventing DNA-uracil excision after massive uracil incorporation (in the thyA dut ung mutants) only makes the RED phase shallower, but does not eliminate it altogether (16). Yet, the source of irreparable chromosomal lesions during TLD could be futile fork breakage-repair cycles (16).

To address the fork breakage-repair idea, we tested the necessity of chromosomal replication for TLD and were perplexed to find normal TLD in the complete absence of replication (22); here we have confirmed this game-changing observation and extended it to the thyA rffHC mutants. The lack of replication requirement, while eliminating the biggest group of TLD models, further highlights the mystery of the massive chromosomal DNA loss during T-starvation, that becomes catastrophic in the thyA rffC mutants (Fig. 4 E and F) or in the awakening protocol at 42 °C (22) (Fig. 5H). Since testing of the most obvious ideas about this DNA loss failed to produce insights here, we can only speculate on its nature.

One possibility is based on the known association of random pieces of the chromosomal DNA with the cell envelope (58), specifically with the outer membrane (59, 60), reflected in the chromosomal DNA capture by the outer membrane vesicles (61, 62). Though random and transient for any particular DNA segment (with the exception of the hemimethylated oriC) (63), this association may in fact be secure in terms of DNA anchoring to the cell envelope, if mediated by special spool-like proteins. If such spooling is jammed in the absence of dTTP, while the cell circumference significantly expands due to the same T-starvation (Fig. 2E), a DNA segment trapped between adjacent envelope-association points may become overextended and eventually snaps, causing a double-strand break (Fig. 6F). While most of these breaks are repaired, a few of them could be irreparable (for whatever reason), causing the observed chromosomal DNA loss and TLD. The same scenario is magnified and accelerated during T-hyperstarvation (Fig. 6F), leading to a complete loss of DNA and to cell lysis (due to the cell envelope overextension, combined with the defect in the EPS capsule and poisoning by accumulating ECA lipid II). The nature of this chromosomal DNA disappearance, and its relation to T-starvation-triggered chromosome fragmentation, should become one of the main directions of future TLD studies.

Materials and Methods

Details of all experimental procedures, including bacterial strains and plasmids, growth and treatment conditions, genomic DNA isolation and analysis, detection of LMW-dT/U species, beta-galactosidase and alkaline phosphatase assays, measuring the SOS induction, fluorescent microscopy, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis to detect chromosome fragmentation are fully described in SI Appendix, Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sanna Koskiniemi (Uppsala Universitet) for reminding us about dTDP-hexoses and William W. Metcalf (University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign) for challenging us to measure LMW-dT pools and for hospitality in his light microscopy facility. We are grateful to all members of A.K.'s laboratory for constructive criticism and support and, in addition, to Lenna Kouzminova for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by grant GM073115 from the NIH.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2012254117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

All study data are included in the article and supporting information.

References

- 1.Ahmad S. I., Kirk S. H., Eisenstark A., Thymine metabolism and thymineless death in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52, 591–625 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barner H. D., Cohen S. S., The induction of thymine synthesis by T2 infection of a thymine requiring mutant of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 68, 80–88 (1954). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen S. S., Barner H. D., Studies on unbalanced growth in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 40, 885–893 (1954). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen S. S., On the nature of thymineless death. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 186, 292–301 (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khodursky A., Guzmán E. C., Hanawalt P. C., Thymineless death lives on: New insights into a classic phenomenon. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 69, 247–263 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakayama H., Nakayama K., Nakayama R., Nakayama Y., Recombination-deficient mutations and thymineless death in Escherichia coli K12: Reciprocal effects of recBC and recF and indifference of recA mutations. Can. J. Microbiol. 28, 425–430 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuong K. J., Kuzminov A., Stalled replication fork repair and misrepair during thymineless death in Escherichia coli. Genes Cells 15, 619–634 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fonville N. C., Bates D., Hastings P. J., Hanawalt P. C., Rosenberg S. M., Role of RecA and the SOS response in thymineless death in Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet. 6, e1000865 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonville N. C., Vaksman Z., DeNapoli J., Hastings P. J., Rosenberg S. M., Pathways of resistance to thymineless death in Escherichia coli and the function of UvrD. Genetics 189, 23–36 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakayama K., Irino N., Nakayama H., The recQ gene of Escherichia coli K12: Molecular cloning and isolation of insertion mutants. Mol. Gen. Genet. 200, 266–271 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakayama K., Kusano K., Irino N., Nakayama H., Thymine starvation-induced structural changes in Escherichia coli DNA. Detection by pulsed field gel electrophoresis and evidence for involvement of homologous recombination. J. Mol. Biol. 243, 611–620 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakayama K., Shiota S., Nakayama H., Thymineless death in Escherichia coli mutants deficient in the RecF recombination pathway. Can. J. Microbiol. 34, 905–907 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakayama H., Escherichia coli RecQ helicase: A player in thymineless death. Mutat. Res. 577, 228–236 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guarino E., Salguero I., Jiménez-Sánchez A., Guzmán E. C., Double-strand break generation under deoxyribonucleotide starvation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 189, 5782–5786 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuong K. J., Kuzminov A., Disintegration of nascent replication bubbles during thymine starvation triggers RecA- and RecBCD-dependent replication origin destruction. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 23958–23970 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao T. V. P., Kuzminov A., Sources of thymidine and analogs fueling futile damage-repair cycles and ss-gap accumulation during thymine starvation in Escherichia coli. DNA Repair (Amst.) 75, 1–17 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sangurdekar D. P., et al. , Thymineless death is associated with loss of essential genetic information from the replication origin. Mol. Microbiol. 75, 1455–1467 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barner H. D., Cohen S. S., Protein synthesis and RNA turnover in a pyrimidine-deficient bacterium. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 30, 12–20 (1958). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallant J., Suskind S. R., Relationship between thymineless death and ultraviolet inactivation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 82, 187–194 (1961). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breitman T. R., Maury P. B., Toal J. N., Loss of deoxyribonucleic acid-thymine during thymine starvation of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 112, 646–648 (1972). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goulian M., Bleile B., Tseng B. Y., Methotrexate-induced misincorporation of uracil into DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 77, 1956–1960 (1980). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan S. R., Kuzminov A., Thymineless death in Escherichia coli is unaffected by chromosomal replication complexity. J. Bacteriol. 201, e00797-18 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okazaki R., Okazaki T., Kuriki Y., Incorporation of [3H] thymidine in a deoxyriboside-requiring bacterium. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 33, 289–291 (1959). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schnaitman C. A., Klena J. D., Genetics of lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in enteric bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 57, 655–682 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samuel G., Reeves P., Biosynthesis of O-antigens: Genes and pathways involved in nucleotide sugar precursor synthesis and O-antigen assembly. Carbohydr. Res. 338, 2503–2519 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuhn H. M., Meier-Dieter U., Mayer H., ECA, the enterobacterial common antigen. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 4, 195–222 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neuhard J., Nygaard P., “Purines and pyrimidines” in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Cellular and Molecular Biology, Neidhardt F. C., Ed. (American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C., 1987), pp. 445–473. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan S. R., Kuzminov A., Replication forks stalled at ultraviolet lesions are rescued via RecA and RuvABC protein-catalyzed disintegration in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 6250–6265 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maharjan R. P., Ferenci T., Global metabolite analysis: The influence of extraction methodology on metabolome profiles of Escherichia coli. Anal. Biochem. 313, 145–154 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Kazzaz W., Morita T., Tagami H., Inada T., Aiba H., Metabolic block at early stages of the glycolytic pathway activates the Rcs phosphorelay system via increased synthesis of dTDP-glucose in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 51, 1117–1128 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marolda C. L., Valvano M. A., Genetic analysis of the dTDP-rhamnose biosynthesis region of the Escherichia coli VW187 (O7:K1) rfb gene cluster: Identification of functional homologs of rfbB and rfbA in the rff cluster and correct location of the rffE gene. J. Bacteriol. 177, 5539–5546 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rick P. D., Wolski S., Barr K., Ward S., Ramsay-Sharer L., Accumulation of a lipid-linked intermediate involved in enterobacterial common antigen synthesis in Salmonella typhimurium mutants lacking dTDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. J. Bacteriol. 170, 4008–4014 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sivaraman J., Sauvé V., Matte A., Cygler M., Crystal structure of Escherichia coli glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase (RffH) complexed with dTTP and Mg2+. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 44214–44219 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu D., Reeves P. R., Escherichia coli K12 regains its O antigen. Microbiology (Reading) 140, 49–57 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rahman A., Barr K., Rick P. D., Identification of the structural gene for the TDP-Fuc4NAc:lipid II Fuc4NAc transferase involved in synthesis of enterobacterial common antigen in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 183, 6509–6516 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neidhardt F. C., “Chemical composition of Escherichia coli” in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Cellular and Molecular Biology, Neidhardt F. C., Ed. (American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C., 1987), pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baba T., et al. , Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2, 2006.0008 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Danese P. N., et al. , Accumulation of the enterobacterial common antigen lipid II biosynthetic intermediate stimulates degP transcription in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180, 5875–5884 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rotman E., Bratcher P., Kuzminov A., Reduced lipopolysaccharide phosphorylation in Escherichia coli lowers the elevated ori/ter ratio in seqA mutants. Mol. Microbiol. 72, 1273–1292 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Witte A., Lubitz W., Biochemical characterization of phi X174-protein-E-mediated lysis of Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 180, 393–398 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dassa E., Boquet P. L., ExpA: A conditional mutation affecting the expression of a group of exported proteins in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Gen. Genet. 181, 192–200 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zaritsky A., Woldringh C. L., Einav M., Alexeeva S., Use of thymine limitation and thymine starvation to study bacterial physiology and cytology. J. Bacteriol. 188, 1667–1679 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sutterlin H. A., et al. , Disruption of lipid homeostasis in the Gram-negative cell envelope activates a novel cell death pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E1565–E1574 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mychack A., et al. , A synergistic role for two predicted inner membrane proteins of Escherichia coli in cell envelope integrity. Mol. Microbiol. 111, 317–337 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jorgenson M. A., Kannan S., Laubacher M. E., Young K. D., Dead-end intermediates in the enterobacterial common antigen pathway induce morphological defects in Escherichia coli by competing for undecaprenyl phosphate. Mol. Microbiol. 100, 1–14 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khan S. R., Kuzminov A., Degradation of RNA during lysis of Escherichia coli cells in agarose plugs breaks the chromosome. PLoS One 12, e0190177 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dillingham M. S., Kowalczykowski S. C., RecBCD enzyme and the repair of double-stranded DNA breaks. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72, 642–671 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuzminov A., Recombinational repair of DNA damage in Escherichia coli and bacteriophage lambda. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63, 751–813 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Breitman T. R., Finkleman A., Rabinovitz M., Methionineless death in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 108, 1168–1173 (1971). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okazaki R., Okazaki T., Studies of deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis and cell growth in the deoxyriboside-requiring bacteria, Lactobacillus acidophilus. I. Biological and chemical nature of the intra-cellular acid-soluble deoxyribosidic compounds. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 28, 470–482 (1958). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Okazaki R., Isolation of a new deoxyribosidic compound, thymidine diphosphate rhamnose. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1, 34–38 (1959). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Okazaki R., Studies of deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis and cell growth in the deoxyriboside-requiring bacteria, Lactobacillus acidophilus. III. Identification of thymidine diphosphate rhamnose. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 44, 478–490 (1960). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kornfeld S., Glaser L., The enzymic synthesis of thymidine-linked sugars. I. Thymidine diphosphate glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 236, 1791–1794 (1961). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hosono R., Hosono H., Kuno S., Effects of growth conditions on thymidine nucleotide pools in Escherichia coli. J. Biochem. 78, 123–129 (1975). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ohkawa T., Studies of intracellular thymidine nucleotides. Relationship between the synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid and the thymidine triphosphate pool in Escherichia coli K12. Eur. J. Biochem. 61, 81–91 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bochner B. R., Ames B. N., Complete analysis of cellular nucleotides by two-dimensional thin layer chromatography. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 9759–9769 (1982). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ohkawa T., Studies of intracellular thymidine nucleotides. Thymineless death and the recovery after re-addition of thymine in Escherichia coli K 12. Eur. J. Biochem. 60, 57–66 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bayer M. E., “The fusion sites between outer membrane and cytoplasmic membrane of bacteria: Their role in membrane assembly and virus infection” in Bacterial Outer Membranes, Inouye M., Ed. (John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1979), pp. 167–202. [Google Scholar]

- 59.d’Alençon E., Taghbalout A., Kern R., Kohiyama M., Replication cycle dependent association of SeqA to the outer membrane fraction of E. coli. Biochimie 81, 841–846 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nicolaidis A. A., Holland I. B., Evidence for the specific association of the chromosomal origin with outer membrane fractions isolated from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 135, 178–189 (1978). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Toyofuku M., Nomura N., Eberl L., Types and origins of bacterial membrane vesicles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 13–24 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bitto N. J., et al. , Bacterial membrane vesicles transport their DNA cargo into host cells. Sci. Rep. 7, 7072 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ogden G. B., Pratt M. J., Schaechter M., The replicative origin of the E. coli chromosome binds to cell membranes only when hemimethylated. Cell 54, 127–135 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and supporting information.