Abstract

Objective:

Hispanic immigrants exhibit more positive outcomes than US-born Hispanics across educational, psychological, and physical health indices, a phenomenon called the immigrant paradox. We examined the immigrant paradox in relation to alcohol use severity among Hispanic young adults while considering both positive (optimism) and negative (depressive symptoms) processes.

Method:

Among 200 immigrant and US-born Hispanic young adults (Mage=21.30; 49% male) in Arizona and Florida, we tested whether optimism and depressive symptoms statistically mediated the relationship between nativity and alcohol use severity. Specifically, we examined whether Hispanic immigrants reported greater optimism than their US-born counterparts, and whether such optimism was, in turn, associated with less depressive symptoms and thus lower alcohol use severity.

Results:

Indirect effects were significant in hypothesized directions (nativity→optimism→depressive symptoms→alcohol use severity).

Conclusions:

Both positive and negative psychological processes are important to consider when accounting for the immigrant paradox vis-à-vis alcohol use severity among Hispanic young adults.

Keywords: alcohol use severity, immigrant paradox, optimism, depression

Compared to US-born Hispanics, Hispanic immigrants often report more positive outcomes across educational, psychological, behavioral, and physical health indices, a phenomenon known as the immigrant paradox (Alcántara, Estevez, & Alegría, 2017). Studies increasingly indicate that Hispanic immigrants engage in less alcohol use compared to their US-born counterparts (e.g., Greene & Maggs, 2018; Salas-Wright, Vaughn, Goings, Córdova, & Schwartz, 2018). However, the underlying mechanisms that account for the immigrant paradox, especially with respect to alcohol use among Hispanics, are not well understood. We posit that optimism – an individual difference variable that reflects the degree to which people hold generalized positive beliefs about the future – is an important positive psychological variable that, in part, accounts for generational disparities in Hispanic alcohol use severity because it protects against negative processes, such as depressive symptoms, that might lead to severe alcohol use (Carver, Scheier, & Segerstrom, 2010).

In the present study, we examine the immigrant paradox in relation to alcohol use severity among Hispanic young adults while examining optimism and depressive symptoms as potential mediators. Specifically, we argue for a mediational sequence in which immigrants are hypothesized to be more optimistic than US-born Hispanics, and such optimism in turn operates against depressive symptoms to result in less alcohol use severity among immigrants. We first discuss alcohol use and the immigrant paradox among Hispanics in the United States. Next, using social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), we discuss why immigrants might exhibit more optimism than US-born Hispanics. We then draw from empirical work to discuss how optimism may work against depressive symptoms to associate with less alcohol use severity.

Alcohol Use, Hispanics, and the Immigrant Paradox

Alcohol is one of the most misused substances in the United States (US). Alcohol misuse accounts for approximately 88,000 deaths per year, making it the third leading cause of death in the US (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). Moreover, alcohol misuse correlates with several psychosocial issues and health risks including drunk driving, violence, family adversity, work performance, risky sexual behaviors, and depression (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA], 2018). Further, because emerging adulthood (ages 18–25) represents a critical developmental period when risky drinking behaviors and mental health issues peak, such as binge-drinking and depression, risk for alcohol-related issues increases among young adults (Merrill & Carey, 2016). Thus, the public health impact of alcohol misuse among young adults is significant, and studies that shed light on the risk and protective processes associated with alcohol misuse for this population are important.

However, alcohol misuse among Hispanics, especially immigrants, remains understudied compared to non-Hispanic Whites (Chartier & Caetano, 2010; Szaflarski, Cubbins, & Ying, 2011; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). Research on alcohol misuse is greatly needed among Hispanic populations in general because studies suggest that the consequences of alcohol misuse are often more severe for Hispanics compared to non-Hispanic Whites. Specifically, although Hispanics may be less likely to drink than non-Hispanic Whites (Goings et al., 2019; Salas-Wright et al., 2018), Hispanics who choose to drink, especially young Hispanic adults (Cano et al., 2015; Venegas, Cooper, Naylor, Hanson, & Blow, 2012), tend to consume higher volumes of alcohol and experience more alcohol-related problems (e.g., liver disease, legal citations from drunk driving, aggression, loss of employment) than non-Hispanic Whites (Mulia, Greenfield, & Zemore, 2009; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013). Studies also show that Hispanic immigrants report lower rates of alcohol use than their US-born Hispanic counterparts (e.g., Greene & Maggs, 2018; Salas-Wright et al., 2018) – where Hispanics from Puerto Rico and Mexico report the highest levels of alcohol use, and those from Cuba report the lowest (see NIAAA, 2018, for a breakdown by country). These findings support the immigrant paradox with respect to alcohol use severity among Hispanics.

Although the underlying mechanisms that explain the immigrant paradox are not well understood, several hypotheses have been advanced (Salas-Wright & Schwartz, 2019). For example, acculturative stress theorists posit that the adversity that US-born Hispanics face while navigating multiple cultures produces stress that elicits alcohol use as a means of coping with such stress (Meca et al., 2019). Assimilation theorists suggest that Hispanics’ drinking patterns change to mirror the drinking norms of the mainstream culture as they assimilate into the dominant culture (Caetano & Clark, 2003). Sociological perspectives posit that healthier individuals are most likely to successfully migrate and thus appear healthier than their US-born counterparts (Crimmins, Soldo, Kim, & Alley, 2005). Others suggest that protective factors from the heritage country, such as positive parenting practices or family-oriented values, erode across generations and result in more drinking among US-born cohorts (Mogro-Wilson, 2008).

Despite advances in accounting for the immigrant paradox, most research focuses exclusively on stressors as explanations for the paradox. Recent work noted patterns of positive health among immigrants and called for more attention to the positive processes underlying such health (Cobb et al., 2019). Inclusion of both stressful and positive processes is important because these processes often cooccur, and together, provide a more holistic view of psychosocial functioning. We argue that optimism may help to account for the immigrant paradox vis-à-vis alcohol use severity because it operates against depressive symptoms that might lead to severe alcohol use (Carver et al., 2010). Optimism may represent an important resilience factor against depressive symptoms because it entails holding positive expectations about the future through positive thinking, which may serve as a cognitive resource that equips individuals to cope with stressful events (Carver et al., 2010; Scheier & Carver, 1993).

Nativity and Optimism among Hispanics

Why might Hispanic immigrants be more optimistic about the future compared to US-born Hispanics? According to social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), individuals construe well-being and positive beliefs by making favorable social comparison with relevant groups in society. Compared with US-born Hispanics, Hispanic immigrants may hold more positive beliefs about their future in the US because they use their countries of origin, where life circumstances were more adverse, as the standard of comparison. Indeed, most immigrants, especially recent immigrants from disadvantaged countries, perceive the US as a “land of opportunity” and arrive optimistic that they will find a better life for themselves and their families (Schwartz et al., 2014).

However, US-born Hispanics, who have different life histories than their foreign-born counterparts, may hold fewer positive beliefs about their future when faced with denied opportunities and discrimination because their standard of comparison is the advantaged society in which they live. There is empirical support, primarily in educational contexts, that immigrants are more optimistic about the future compared to their US-born counterparts (Fernández-Reino, 2016; Feliciano & Lanuza, 2016). We expect that Hispanic immigrants will report greater optimism regarding the future compared to US-born Hispanics.

Optimism and Depressive Symptoms

Research has also established links between optimism and risk for psychopathology such as depression (Carver et al., 2010). Individual differences in optimism impact the ways that people respond to and cope with stressful life circumstances (Taylor et al., 2012). For example, across contexts, optimism positively correlates with resilience, lower stress, larger social networks, better physical health, perseverance in crises, effective coping strategies, self-efficacy, and psychological adjustment (see Carver et al., 2010; Taylor et al., 2012 for reviews). By definition, optimism also negatively correlates with hopelessness and stress (Carver et al., 2010), both of which are risk factors for the onset and relapse of depression (Alloy, 2006).

Despite a dearth of research on optimism among Hispanic immigrants, González and González (2008) found that optimism negatively correlated with depression and positively correlated with life satisfaction among Mexican immigrant college students. Research also linked optimism with having fewer problems with alcohol misuse (Ohannessian, Hesselbrock, Tennen, & Affleck, 1993; Wray, Dvorak, Hsia, Arens, & Schweinle, 2013). These findings suggest that optimism provides individuals with cognitive and behavioral resources that protect against risk and promote health. We posit that not only will Hispanic immigrants report greater optimism than their US-born counterparts, but that such optimism will in turn negatively associate with depressive symptoms.

Depressive Symptoms and Alcohol Use Severity

Whereas optimism negatively correlates with depressive symptoms, there is considerable evidence that depressive symptoms relate to higher alcohol consumption (e.g., Cano et al., 2017; Gonzalez, Reynolds, & Skewes, 2011; Jetelina et al., 2016) – suggesting that optimism may protect against alcohol use indirectly through preventing or reducing depressive symptoms. Considering that the relationship between alcohol use and depression is likely bi-directional (Boden & Fergusson, 2011), alcohol can be used as a means of coping with the negative thoughts and feelings associated with depressive symptoms. Recent longitudinal research among adolescents and young adults showed that drinking to cope with depression increased the risk of alcohol problems, and that depression severity increased subsequent alcohol use (Collins, Thompson, Sherry, Glowacka, & Stewart, 2018; Schleider et al., 2019). We therefore hypothesize that depressive symptoms will positively associate with alcohol use severity and will mediate the link between optimism and alcohol use.

The Present Study

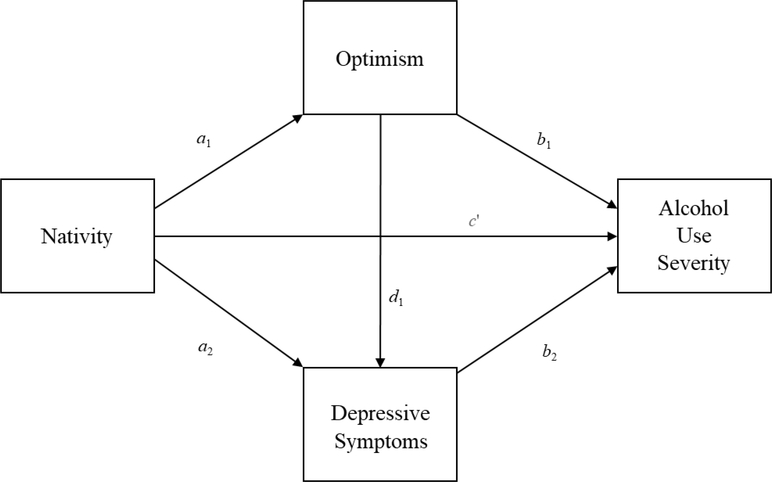

Together, there are consistent links between nativity status, optimism, depressive symptoms, and alcohol use severity among Hispanic immigrants and their US-born counterparts. We hypothesize a serial mediational model that suggests Hispanic immigrants will report more optimism than their US-born counterparts. Hypothesized model pathways are specified in Figure 1. The present study advances the literature by (a) testing a novel psychosocial model using serial mediation analysis that elucidates the underlying mechanisms through which nativity relates to alcohol use severity and (b) examining both negative (depressive symptoms) and positive processes (optimism) that, in part, help to explain the immigrant paradox. First, based on theory and prior research, we hypothesized that nativity status would relate to alcohol use severity indirectly through optimism and depressive symptoms. Specifically, Hispanic immigrants will report greater optimism regarding the future compared to their US-born counterparts; such optimism will in turn relate to fewer depressive symptoms and consequentially lower alcohol use severity. In contrast, US-born Hispanics will report less optimism regarding the future; less optimism will in turn relate to greater depressive symptoms and consequentially higher alcohol use severity.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Serial Mediation Model Pathways

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 200 immigrant and US-born Hispanics residing in Maricopa County, Arizona and Miami-Dade County, Florida. Approximately 49% were men (n=98) and 51% were women (n=102). Regarding site of residence, 49.5% lived in Maricopa County (n=99), and 50.5% lived in Miami-Dade County (n=101). Moreover, 70% of participants were US-born (n=140), whereas 30% were foreign-born immigrants (n=60). Average age of participants was 21.30 (SD=2.09). Approximately 44% of participants reported being of Mexican heritage (n=88) whereas 56% reported being of non-Mexican heritage (n=112; see Table 1 for breakdown by country of origin). Regarding education, 76.5% reported having never received a bachelor’s degree (n=153), and 23.5% reported having a bachelor’s degree (n=47). We used financial strain as a measure of socioeconomic status: 7% reported having more money than they need (n=14), 56% reported having just enough money for their needs (n=112), and 37% reported not having enough money to meet their needs (n=74). Finally, 69.5% reported they were currently a college student (n=139), and 30.5% reported that they were not currently a student (n=61).

Table 1.

Frequency Table for Self-Reported Ethnic Heritage by County (N = 200)

| Miami-Dade County | Maricopa County | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic Heritage | Frequency (n) | Frequency (n) | Total % |

| Argentinian | 4 | 0 | 2% |

| Brazilian | 1 | 0 | .5% |

| Chilean | 1 | 0 | .5% |

| Colombian | 21 | 1 | 11% |

| Costa Rican | 3 | 0 | 1.5% |

| Cuban | 32 | 1 | 16.5% |

| Dominican | 2 | 2 | 2% |

| Guatemalan | 0 | 4 | 2% |

| Honduran | 7 | 0 | 3.5% |

| Mexican | 2 | 86 | 44% |

| Nicaraguan | 6 | 0 | 3% |

| Panamanian | 1 | 0 | .5% |

| Peruvian | 5 | 0 | 2.5% |

| Puerto Rican | 5 | 4 | 4.5% |

| Salvadorian | 1 | 0 | .5% |

| Venezuelan | 10 | 0 | 5% |

| Other | 0 | 1 | .5% |

| Total | 50.5% (101) | 49.5% (99) | 100% (200) |

Procedures

The present study is a secondary analysis that is part of a larger cross-sectional study among Hispanic young adults – Project on Health among Emerging Adult Latinos (Project HEAL). We used quota sampling to recruit participants in Maricopa and Miami-Dade County. Participants were recruited through (a) social media, (b) in-person distribution of flyers, (c) posting of flyers with tear-off tabs, and (d) emailing the study details to organizations and individuals who may have had access to our target sample. Furthermore, most participants who were not current college students were recruited in-person by research personnel who have experience in recruiting Hispanic participants. Interested participants contacted Project HEAL and were screened by the research team to ascertain whether they were eligible for the study. Inclusion criteria included being ages 18–25, self-identifying as Hispanic, currently living in Maricopa or Miami-Dade County, and not currently pregnant and/or breastfeeding. Participants provided informed consent to participate via an electronic informed consent form. All measures were completed in English, and ability to read English was listed as a recruitment requirement for both sites. Data were collected between August 2018 and February 2019 using a confidential online survey utilizing Qualtrics software. The survey took approximately 50 minutes to complete, and participants were compensated with a $30 Amazon gift card. This study was approved by the University Institutional Review Board at the last author’s home university.

Measures

Nativity.

We measured nativity by asking participants to report their immigrant generation status and subsequently dichotomized responses. First-generation, foreign-born immigrants were coded as 0, and all other generations who were born in the US were coded as 1.

Optimism.

Dispositional optimism was measured with the Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R), which includes two factors, one with positive phrasing and one with negative phrasing that is reverse-scored (Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994). Due to time limitations, the present study only used the factor with negatively phrased items because this factor has the highest factor loadings and better internal consistency (Segerstrom, Evans, & Eisenlohr-Moul, 2011; Scheier et al., 1994). Participants rated each item on a 4-point scale ranging from 0=Strongly Disagree to 4=Strongly Agree. A sample item is “I rarely count on good things happening to me.” All responses were reverse scored and higher scores reflect greater levels of optimism. The LOT-R has been found valid and reliable for Hispanic populations (Perczek, Carver, Price, & Pozo-Kaderman, 2000). Reliability analysis in the present study indicated good internal consistency (α=.87).

Depressive symptoms.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to assess depressive symptoms. We used the 10-item revised version (González et al., 2017) taken from the original 20-item version (Radloff, 1977). Participants rate how frequently they experienced a range of thoughts and feelings related to depression on a 4-point scale ranging from 0=Rarely or none of the time to 3=All of the time. Higher scores reflect greater depressive symptoms. A sample item includes “I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me.” The revised measure has been found valid and reliable (Cronbach’s alpha’s = .80–.86; test-retest reliability, r values = .41–.70) for Hispanic populations (González et al., 2017). Reliability analysis in the present sample indicated good internal consistency (α=.84).

Alcohol use severity.

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) was used to index participants’ reports of alcohol use severity over the past year. The AUDIT was initially created by the World Health Organization to identify problem drinkers in primary care settings. The measure consists of 10 items measured on a 4-point scale ranging from 0=Never to 4=four or more times a week. Sample items included “How often do you have a drink containing alcohol?” and “How often do you have six or more drinks on one occasion?” Higher scores reflect greater alcohol use severity. The AUDIT has been found valid and reliable with Hispanic populations (Babor, Biddle-Higgins, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001). Reliability analysis in the present sample indicated excellent internal consistency (α=.90).

Data Analysis

Before performing primary analyses, we examined the data for linearity, nonnormality, outliers, and multicollinearity. Next, we estimated hypothesized associations among primary variables and covariates. To test our serial mediation model, we used ordinary least squares (OLS) nonparametric bootstrapping which provides greater statistical power compared to normal theory approaches and produces better approximations of sampling distributions of indirect effects. Bootstrapping provides a robust method to assess mediated effects and control for Type I errors (Hayes, 2018). Another advantage of bootstrapping to test mediated effects is that it does not require the typical assumption of normality of the sampling distribution (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). We tested mediation in PROCESS (SPSS v.26; IBM, 2018) using bootstrapping with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) corrected for bias with 10,000 bootstrapped resamplings. An indirect effect is significant when the CI does not include a value of 0 (Hayes, 2018).

When testing serial mediation models using two mediators in sequence, because multiple indirect effect pathways are possible, four indirect effects (there are two indirect effects in model 3) must be computed (See Figure 1):

Model 1: nativity → optimism → alcohol use severity

Model 2: nativity → depressive symptoms → alcohol use severity

Model 3: nativity → optimism → depressive symptoms → alcohol use severity

Once the four indirect effects are computed, they are each tested for significance. If more than one indirect effect is significant, linear contrasts are then provided to determine which indirect effect has the strongest influence on the outcome (alcohol use severity) Because age, gender, site of residence, socioeconomic status, and student status correlate with both alcohol use and depression (Cano et al., 2017; Ramisetty-Mikler, Caetano, & Rodriguez, 2010; Schwartz et al., 2014), we included them as covariates if they were related to our mediators and/or outcome.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

Before estimating our proposed model, we assessed data for multivariate outliers, normality, linearity, and multicollinearity. Multivariate outliers and normality were evaluated by computing Mahalanobis Distances and comparing obtained values of main variables to a critical value based on the chi-square distribution. Approximately 12 cases produced observed distances that exceeded the critical value (χ2=7.82). To evaluate whether these 12 cases significantly influenced our model, we computed Cook’s Distances. According to Tabachnick and Fidell (2007), cases that yield a Cook’s Distance larger than 1 pose potential issues for the model. The 12 cases yielded maximum Cook’s Distance values of .06, indicating no significant issues. We therefore retained all cases in the sample. Approximately 2–3% of data were missing, and we used the expectation-maximization algorithm for any cases missing data.

We assessed linearity by producing a scatterplot matrix of primary variables, and no major violations were observed. To investigate potential issues of multicollinearity, we computed the tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) across variables; values less than .10 or greater than 10, respectively, indicate multicollinearity. Tolerance values exceeded .10, and VIF values ranged from 1–2, suggesting no issues with multicollinearity. Further, because student status (student vs. nonstudent), socioeconomic status, age, gender, and context of reception have been linked with the mediators (optimism and depressive symptoms) and/or outcome (alcohol use severity) of our model, we examined the zero-order correlations to determine which variables to include as covariates. Examination of the correlation table indicated that all covariates except for gender were significantly related to one or both mediators and/or to the outcome. Thus, we did not include gender in our model as a covariate. Correlations, means, and standard deviations are presented in Table 2. For categorical variables, the Pearson correlation was not computed; we instead used the chi-square tests of independence to asses associations between categorical variables. Results showed a significant relationship between site of residence and nativity, such that immigrants were more likely to be represented in Miami-Dade County whereas US-born individuals were more likely to be represented in Maricopa County, χ2(1)=23.48, p < .001. Furthermore, results indicated no significant association between student status and nativity χ2(1)=23.48, p=.12, and no association between student status and site of residence, χ2(1)=23.48, p=.81. Finally, gender was not associated with nativity, χ2(1)=4.15, p = .06); site of residence, χ2(1)=.50, p = .49; or student status, χ2(1)=.001, p=.97.

Table 2.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations (N = 200)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Alcohol Use Severity | - | ||||||||

| 2. Depressive Symptoms | .32** | - | |||||||

| 3. Optimism | −.22** | −.58** | - | ||||||

| 4. Nativity | .12 | .25** | −.21** | - | |||||

| 5. Financial Strain | .10 | .19** | −.22** | .02 | - | ||||

| 6. Age | .16* | −.15* | .03 | .08 | −.02 | - | |||

| 7. Site of Residence | .31** | .20** | −.22** | - | .07 | .17* | - | ||

| 8. Student Status | −.03 | −.32** | .16* | - | −.19** | .30** | - | - | |

| 9. Gender | −.05 | .12 | −.05 | - | .09 | −.05 | - | - | - |

| Means | 5.00 | 9.75 | 7.20 | - | 2.30 | 21.30 | |||

| SD | 5.98 | 6.39 | 2.79 | - | .59 | 2.10 |

Note.

p < .05

= p < .001.

Correlations between categorical variables were not computed for Pearson correlations. Also, correlations between categorical and continuous variables reflect point-biserial correlations.

Primary Analyses

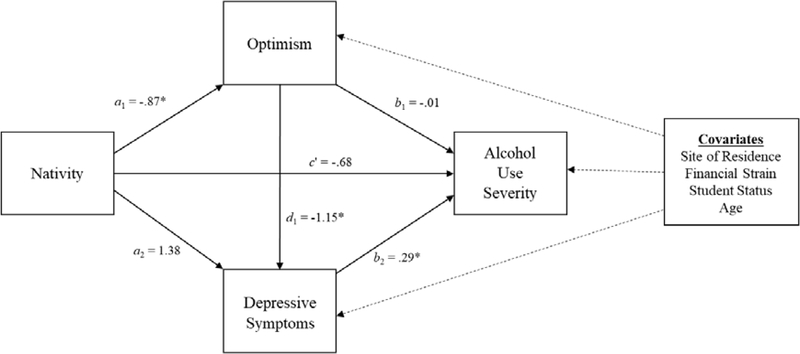

Using a serial mediation analysis conducted using OLS path analysis, based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples, three models of indirect effects were tested with respect to the link between nativity (immigrant vs. nonimmigrant) and alcohol use severity. Figure 2 and Table 3 show pathways and unstandardized coefficients.

Figure 2.

Serial Mediation Model with Unstandardized Coefficients. Covariates are represented by dashed lines and were controlled for in all mediation pathways.

Table 3.

Unstandardized Path Estimates for Serial Mediation Model

| Outcome | Predictor | Estimate | p-value | 95% C.I. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimism | Nativity | −.87 | .04* | −1.74 to −.01 |

| Site of Residence | −.91 | .02* | −1.71 to −.11 | |

| Financial Strain | −.86 | .01* | −.067 to .324 | |

| Student Status | .61 | .17 | −.26 to 1.47 | |

| Age | .05 | .60 | −.14 to .24 | |

| Depressive Symptoms | Nativity | 1.38 | .10 | −.26 to 3.02 |

| Optimism | −1.15 | .001** | −.391 to .146 | |

| Site of Residence | .94 | .22 | −.57 to 2.46 | |

| Financial Strain | .37 | .55 | −.84 to 1.59 | |

| Student Status | −2.77 | .001** | −4.40 to −1.14 | |

| Age | −.29 | .11 | −.64 to .06 | |

| Alcohol Use Severity | Nativity | −68 | .46 | −2.50 to 1.14 |

| Optimism | −.01 | .96 | −.35 to .33 | |

| Depressive Symptoms | .29 | .001** | .14 to .45 | |

| Site of Residence | 2.73 | .001** | 1.06 to 4.41 | |

| Financial Strain | .31 | .65 | −1.03 to 1.65 | |

| Student Status | .31 | .74 | −1.53 to 2.15 | |

| Age | .48 | .02* | .09 to .87 |

Note.

p < .05

p < .001

Model 1:

Results from mediation analysis assessing the indirect effect of optimism in the link between nativity and alcohol use severity (nativity → optimism → alcohol use severity) were nonsignificant after controlling for covariates (a1b1=.01, CI95%=−.30 to .35).

Model 2:

Results of mediation analyses assessing the indirect effect of depressive symptoms in the link between nativity and alcohol use severity (nativity → depressive symptoms → alcohol use severity) were also nonsignificant after controlling for covariates (a2b2=.41, CI95%=−.01 to 1.15).

Model 3:

In contrast to models 1 and 2, results from mediation analysis assessing the indirect effects of both optimism and depressive symptoms in the link between nativity and alcohol use severity (nativity → optimism → depressive symptoms → alcohol use severity) were significant after controlling for covariates (a1d1b2=.30, CI95%=.04 to .83). As can be seen in Figure 2, all pathways were in the hypothesized directions. Specifically, immigrants reported significantly more optimism about the future than did their US-born counterparts (a1=−.87, p=.0001, CI95%=−1.74 to −.01). Optimism was in turn negatively associated with fewer depressive symptoms (d1=−1.15, p = .0001, CI95%=−1.41 to −.88), which was in turn positively associated with alcohol use severity (b2=.29, p=.0003, CI95%=.14 to .45). Thus, our model was supported, such that immigrants were more optimistic than their US-born counterparts, which in turn resulted in less depressive symptoms and thus less alcohol use severity. There was no evidence that nativity influenced alcohol use severity independent of its effects through both optimism and depressive symptoms (c’=−.68, p=.46, CI95%=−2.50 to 1.14). Furthermore, because models 1 and 2 were not significant, it was unnecessary to examine linear contrasts of indirect effects to determine which model produced the strongest indirect effects.

It is also worth noting that some of the covariates indicated interesting and significant patterns. With respect to alcohol use severity, only site of residence and age were significant. Specifically, Hispanics residing in Maricopa County reported higher alcohol use severity compared to Hispanics residing in Miami-Dade County, Florida (b=2.73, p=.002, CI95%=1.06 to 4.41). Age was also positively related to alcohol use severity (b=.48, p=.02, CI95%=.09 to .87). With respect to depressive symptoms, students reported significantly greater depressive symptoms than did their nonstudent counterparts (b=−2.77, p=.0009, CI95%=−4.40 to −1.14). Finally, only site of residence and financial strain were significantly related to optimism about the future; individuals residing in Maricopa County reported less optimism than did individuals who resided in Miami-Dade County (b=−.91, p=.03, CI95%=−1.71 to −.11), and financial strain was negatively associated with optimism (b=−.86, p=.009, CI95%=−1.49 to −.22).

Discussion

The present study was designed to examine the immigrant paradox in relation to alcohol use severity among Hispanic young adults while considering optimism and depressive symptoms as potential mediators. Overall, there was no direct evidence of an immigrant paradox because nativity was not directly associated with alcohol use severity independent of its effects through optimism and depressive symptoms. However, there was evidence of an immigrant paradox and alcohol use severity indirectly through optimism and depressive symptoms. Specifically, Hispanic immigrants reported significantly greater optimism than did their US-born Hispanic counterparts. Such optimism was, in turn, associated with experiencing fewer depressive symptoms, which was associated with lower alcohol use severity. Findings from the present study provide new insights that help to explain the immigrant paradox vis-à-vis alcohol use severity among Hispanic young adults. Findings from the present study may also have implications for clinicians who work with Hispanics such that optimism may represent an important psychological resource from which practitioners can draw to combat alcohol misuse.

First, in support of our hypothesis, the notion that immigrants reported greater optimism than their US-born counterparts, is in line with social-psychological predictions that social comparisons may play a vital role in how individuals appraise their lives and their futures (Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987). It is well-known that most Hispanic immigrants migrate in hope of a better life from countries where national conditions are significantly more unfavorable than the national conditions of the United States. Studies have consistently linked such unfavorable economic conditions (e.g., poverty, unemployment), as well as non-economic conditions (e.g., gender inequality, political corruption, religious freedom) to immigrants’ primary reasons for migrating (e.g., Bartram, 2011; Boski, 2013; Schwartz et al., 2010). Thus, when appraising their lives and futures, Hispanic immigrants may be more optimistic because they compare life in the US with life back in their home countries, resulting in a favorable social comparison. However, US-born Hispanics generally do not share this life history and are thus unable to make the same type of comparison. Instead, they compare their lives and futures to those of the more advantaged, US-society in which they live. Thus, when faced with structural barriers and discrimination associated with being an ethnic minority, US-born Hispanics may hold fewer positive beliefs about their future than Hispanic immigrants.

Second, and line with our hypothesis, optimism was in turn associated with fewer depressive symptoms. This is likely because optimism is, by definition, antithetical to depression. Indeed, optimism is defined by positive beliefs and expectancies regarding the future, whereas a defining characteristic of depression is hopelessness and negative expectancies regarding the future. Optimism tends to be inversely related to stress (Carver et al., 2010), which is a risk factor for the onset and continuation of depression (Alloy, 2006). This finding is consistent with prior research on Mexican immigrant college students, indicating that optimism was negatively associated with depression and positively associated with life satisfaction (González & González, 2008). The protective role of optimism against depressive symptoms and alcohol use severity is not only novel theoretically, but it may also be important to developing interventions that target optimism for Hispanic young adults, especially immigrants.

For example, interventions may help to foster optimism among Hispanics young adults, both immigrant and US-born, by encouraging them to reflect on important life goals and to identify concrete ways of reaching those goals. Such exercises may increase optimism because they provide individuals with more defined pathways to obtaining salient life goals, which may encourage positive thinking about the future. Another possible intervention may target optimism by identifying and capitalizing on the strengths shared by many Hispanics such as familism, community support systems, and social-cognitive coping skills (Cobb et al., 2019). Extensive evidence exists that positive appraisal (in which stressful events are re-construed as benign, valuable, or beneficial), a cognitive skill that can lead to increased optimism, can counter self-attribution in the face of negative life experiences (Antonovsky, 1987). Capitalizing on strengths among Hispanic young adults may encourage optimistic thinking because individuals feel more empowered to cope with stressful events more successfully.

Third, we found support for the hypothesis that depressive symptoms would be positively associated with greater alcohol use severity. Recent studies, including longitudinal research, have consistently documented depressive symptoms as a strong correlate of alcohol misuse (e.g., Collins et al., 2018; Jetelina, Reingle-Gonzalez, Vaeth, Mills, & Caetano, 2016; Schleider et al., 2019), especially among young adults (Cano 2015, 2017; Gonzalez, 2011). Both Hispanic immigrants and US-born Hispanics experience significant cultural stress associated with navigating multicultural streams, discrimination, anti-immigrant policies, and language barriers – and alcohol is often used as a means of coping with the negative thoughts and feelings associated with such cultural stress (Schwartz et al., 2015). Our findings support prior research suggesting significant associations between depressive symptoms and alcohol misuse among Hispanic young adults.

Perhaps the most important finding is the sequence of indirect effects linking nativity to alcohol use severity after controlling for covariates. Indeed, there was no evidence supporting an association between nativity and alcohol use severity independent of its effects through optimism and depressive symptoms. Moreover, when testing the serial mediation model (nativity → optimism → depressive symptoms → alcohol use severity), two additional models, one assessing the indirect effect of optimism in isolation (nativity → optimism → alcohol use severity) and the other assessing the indirect effect of depressive symptoms in isolation (nativity → depressive symptoms → alcohol use severity), were tested and found to be nonsignificant. This is important because such findings rule out alternative pathways and delineate the specific pathway sequence through which nativity might influence alcohol use severity among Hispanic young adults.

Theoretical Implications, Limitations, and Conclusions

Our study possesses several theoretical implications that contribute to the literature. First, we identified and tested a theoretically-novel psychosocial model that, indirectly, accounts for the immigrant paradox regarding alcohol use severity. Moreover, we included a positive psychological process in our model, optimism, that has been neglected in the literature. The vast majority of research on the immigrant paradox tends to focus on stressors and pathology with little to no attention paid to the interplay between positive and negative processes (depressive symptoms) vis-à-vis health-risk behaviors. Finally, we helped to rule out two alternative mediating sequences through which these pathways could occur.

Findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, our data were cross-sectional, and we cannot conclusively establish directionality of effects without longitudinal or experimental data. Further, all surveys were administered and completed in English. Although we explicitly noted English reading proficiency as an inclusion criterion, our sample may not be representative of the larger Hispanic community, especially for those who speak little English. Moreover, we relied on a convenience sample of young adults, which may have resulted in selection effects regarding who participated in the study, as well as a lack of generalizability to other receiving contexts and age groups. Another limitation is that our study sample was recruited from geographical areas with large Hispanic populations. Accordingly, results from the present study may not generalize to regions where fewer Hispanics reside. Further, most participants in the present study come from Mexico and Cuba, while others originate from nations in Central and South America. These cultures are unique in their own right, and constructs such as optimism may be understood differently depending on the specific country of origin. These limitations notwithstanding, our study is the first to test a model that includes both positive and negative processes while attempting to explain, in part, the immigrant paradox and alcohol use severity among Hispanic young adults. In addition, although data were cross-sectional, the present study provides preliminary data that may serve as a model for subsequent research to replicate using other methodologies.

For example, future research may assess our model using longitudinal data. Longitudinal designs not only assist in establishing directionality of pathways, but also provide less biased estimates of model parameters when testing mediation (O’Laughlin, Martin, & Ferrer, 2018). Further, researchers may investigate these pathways among less acculturated immigrants using measures in Spanish. This may be particularly important for those who recently arrived to the US or who have resided in ethnic enclaves for extended periods of time where there is little need to use English. Among our covariates, we found that individuals in Maricopa County were less optimistic and more likely to engage in more severe alcohol use compared to individuals in Miami-Dade County. Future work may compare these differing contexts of receptions and identify context-specific factors that may contribute to health-risk behaviors. We also found that students were more likely than nonstudents to experience depressive symptoms. It may be useful to explore these associations in future work. Further, in contrast to prior research that has found gender differences in drinking behaviors, we found gender to be unrelated to all study variables. Future work may further examine the sociocultural factors that impact gender-related outcomes. Finally, optimism is but one of many positive psychological factors that may contribute to the health of Hispanic populations, and future research may consider other positive constructs that may account for generational disparities among Hispanics.

Taken together, we have outlined a model that includes both positive and negative processes to explain, at least in part, the link between nativity status and alcohol use severity. We hope that future work will build upon this important line of research and recognize the value in understanding the factors, especially positive psychological processes, that protect against alcohol use severity among underserved, such as Hispanics. We also hope that practitioners will consider novel and effective ways to harness optimism as a lever for intervention when working with this vulnerable yet underserved population.

Acknowledgements:

Preparation of this article was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [K01AA025992, K01AA024832, R01AA027767] and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities [U54 MD002266]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author Disclosures: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest and do not have any financial disclosures to report.

References

- Alcántara C, Estevez CD, & Alegría M (2017). Latino and Asian immigrant adult health: Paradoxes and explanations In Schwartz SJ & Unger J, (Eds.), Oxford handbook of acculturation and health, (pp. 197–236). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Whitehouse WG, Hogan ME, Panzarella C, & Rose DT (2006). Prospective incidence of first onsets and recurrences of depression in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115(1), 145–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky A (1987). Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco, CA, US: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, & Monteiro MG (2001). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary health care (2nd ed.). Geneva, CH: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Bacio GA, & Ray LA (2016). Patterns of drinking initiation among Latino youths: cognitive and contextual explanations of the immigrant paradox. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 25, 546–556. [Google Scholar]

- Bartram D (2011). Economic migration and happiness: Comparing immigrants’ and natives’ happiness gains from income. Social Indicators Research, 103, 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Boden JM & Fergusson DM (2011). Alcohol and depression. Addiction, 106, 906–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boski P (2013). A psychology of economic migration. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44, 1067–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Brière FN, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Klein D, & Lewinsohn PM (2014). Comorbidity between major depression and alcohol use disorder from adolescence to adulthood. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55, 526–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham KP, Anderson DR, & Huyvaert KP (2011). AIC model selection and multimodel inference in behavioral ecology: some background, observations, and comparisons. Behavioral Ecology and Aociobiology, 65(1), 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, & Clark CL (2003). Acculturation, alcohol consumption, smoking, and drug use among Hispanics In Chun KM, Balls Organista P, & Marı Gń (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement and applied research (pp. 223–239). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Cano MÁ, de Dios MA, Correa-Fernández V, Childress S, Abrams JL, & Roncancio AM (2017). Depressive symptom domains and alcohol use severity among Hispanic emerging adults: Examining moderating effects of gender. Addictive behaviors, 72, 72–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, Sánchez M, Trepka MJ, Dillon FR, Sheehan DM, Rojas P, … & De La Rosa M. (2017). Immigration stress and alcohol use severity among recently immigrated Hispanic adults: Examining moderating effects of gender, immigration status, and social support. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73, 294–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MÁ, Vaughan EL, De Dios MA, Castro Y, Roncancio AM, & Ojeda L (2015). Alcohol use severity among Hispanic emerging adults in higher education: Understanding the effect of cultural congruity. Substance Use & Misuse, 50, 1412–1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, and Segerstrom SC (2010). Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 879–889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Excessive alcohol use. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/factsheets/alcohol.htm

- Chartier K, & Caetano R (2010). Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Research and Health, 33, 152–160 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb CL, Branscombe NR, Meca A, Schwartz SJ, Xie D, Zea MC, … & Martinez CR Jr. (2019). Toward a Positive Psychology of Immigrants. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14, 619–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JL, Thompson K, Sherry SB, Glowacka M, & Stewart SH (2018). Drinking to cope with depression mediates the relationship between social avoidance and alcohol problems: A 3-wave, 18-month longitudinal study. Addictive Behaviors, 76, 182–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins EM, Soldo BJ, Ki Kim J, & Alley DE (2005). Using anthropometric indicators for Mexicans in the United States and Mexico to understand the selection of migrants and the “Hispanic paradox”. Social Biology, 52, 164–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano C, & Lanuza YR (2016). The immigrant advantage in adolescent educational expectations. International Migration Review, 50, 758–792. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Reino M (2016). Immigrant optimism or anticipated discrimination? Explaining the first educational transition of ethnic minorities in England. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 46, 141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando PJ, Chico E, & Tous JM (2002). Psychometric properties of the Life Orientation Test. Psicothema, 14, 673–680. [Google Scholar]

- Goings TC, Salas-Wright CP, Belgrave FZ, Nelson EJ, Harezlak J, & Vaughn MG (2019). Trends in binge drinking and alcohol abstention among adolescents in the US, 2002–2016. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 200, 115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González P, & González GM (2008). Acculturation, optimism, and relatively fewer depression symptoms among Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans. Psychological Reports, 103, 566–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González P, Nuñez A, Merz E, Brintz C, Weitzman O, Navas EL, … & Perreira K. (2017). Measurement properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (ces-d 10): Findings from Hchs/sol. Psychological Assessment, 29, 372–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez VM, Reynolds B, & Skewes MC (2011). Role of impulsivity in the relationship between depression and alcohol problems among emerging adult college drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 19, 303–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene KM, & Maggs JL (2018). Immigrant paradox? Generational status, alcohol use, and negative consequences across college. Addictive Behaviors, 87, 138–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. Released 2018. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Jetelina KK, Reingle Gonzalez JM, Vaeth PA, Mills BA, & Caetano R (2016). An investigation of the relationship between alcohol use and major depressive disorder across Hispanic national groups. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40, 536–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meca A, Zamboanga BL, Lui PP, Schwartz SJ, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Gonzales-Backen MA, … & Baezconde-Garbanati L. (2019). Alcohol initiation among recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents: Roles of acculturation and sociocultural stress. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 89, 567–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Carey KB (2016). Drinking over the lifespan: focus on college ages. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 38, 103–114 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogro-Wilson C (2008). The influence of parental warmth and control on Latino adolescent alcohol use. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 30, 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, & Zemore SE (2009). Disparities in alcohol-related problems among White, Black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 33, 654–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2018). Alcohol facts and statistics. Retrieved from https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-facts-and-statistics.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2019). Alcohol facts and statistics. Retrieved from https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/sites/default/files/hispanicFact.pdf

- Ohannessian CM, Hesselbrock VM, Tennen H, & Affleck G (1994). Hassles and uplifts and generalized outcome expectancies as moderators on the relation between a family history of alcoholism and drinking behaviors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 55, 754–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan TM, Mills SD, Fox RS, Baik SH, Harry KM, Roesch SC, … & Malcarne VL. (2017). The psychometric properties of English and Spanish versions of the Life Orientation Test-Revised in Hispanic Americans. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 39, 657–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perczek R, Carver CS, Price AA, & Pozo-Kaderman C (2000). Coping, mood, and aspects of personality in Spanish translation and evidence of convergence with English versions. Journal of Personality Assessment, 74(1), 63–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ramisetty-Mikler S, Caetano R, & Rodriguez LA (2010). The Hispanic Americans Baseline Alcohol Survey (HABLAS): alcohol consumption and sociodemographic predictors across Hispanic national groups. Journal of Substance Use, 15, 402–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE (1980). Reliability of the CES-D scale in different ethnic contexts. Psychiatry Research, 2, 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Kagotho N, & Vaughn MG (2014). Mood, anxiety, and personality disorders among first and second-generation immigrants to the United States. Psychiatry Research, 220, 1028–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, & Schwartz SJ (2019). The study and prevention of alcohol and other drug misuse among migrants: toward a transnational theory of cultural stress. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17, 346–369. [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Goings TTC, Córdova D, & Schwartz SJ (2018). Substance use disorders among immigrants in the United States: a research update. Addictive Behaviors, 76, 169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Goings TC, Miller DP, Chang J, & Schwartz SJ (2018). Alcohol-related problem behaviors among Latin American immigrants in the US. Addictive Behaviors, 87, 206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Goings TC, Miller DP, & Schwartz SJ (2018). Immigrants and mental disorders in the united states: New evidence on the healthy migrant hypothesis. Psychiatry Research, 267, 438–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF & Carver CS (1993). On the power of positive thinking: the benefits of being optimistic. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, & Bridges MW (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 1063–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleider JL, Ye F, Wang F, Hipwell AE, Chung T, & Sartor CE (2019). Longitudinal Reciprocal Associations Between Anxiety, Depression, and Alcohol Use in Adolescent Girls. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 43(1), 98–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Zamboanga BL, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Des Rosiers SE, … & Szapocznik J. (2015). Trajectories of cultural stressors and effects on mental health and substance use among Hispanic immigrant adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56, 433–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Des Rosiers SE, Villamar JA, Soto DW, … & Szapocznik J. (2014). Perceived context of reception among recent Hispanic immigrants: Conceptualization, instrument development, and preliminary validation. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(1), 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, & Szapocznik J (2010). Rethinking the concept of acculturation: implications for theory and research. American Psychologist, 65, 237–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC, Evans DR, & Eisenlohr-Moul TA (2011). Optimism and pessimism dimensions in the Life Orientation Test-Revised: Method and meaning. Journal of Research in Personality, 45, 126–129. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2013). Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings (NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13–4795). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresults2012/NSDUHresults2012.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2015). Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Retrieve from www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.pdf

- Sullivan LE, Fiellin DA, & O’Connor PG (2005). The prevalence and impact of alcohol problems in major depression: a systematic review. The American Journal of Medicine, 118, 330–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski M, Cubbins LA, & Ying J (2011). Epidemiology of alcohol abuse among U.S. immigrant populations. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 13, 647–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, & Turner J (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior In Worchel S & Austin W (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor ZE, Widaman KF, Robins RW, Jochem R, Early DR, & Conger RD (2012). Dispositional optimism: a psychological resource for Mexican-origin mothers experiencing economic stress. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(1), 133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC, Hogg M, Oakes P, Reicher S, & Wetherell M (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health. Retrieved from https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/surgeon-generals-report.pdf [PubMed]

- Venegas J, Cooper TV, Naylor N, Hanson BS, & Blow JA (2012). Potential cultural predictors of heavy episodic drinking in Hispanic college students. The American Journal on Addictions, 21, 145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray TB, Dvorak RD, Hsia JF, Arens AM, & Schweinle WE (2013). Optimism and pessimism as predictors of alcohol use trajectories in adolescence. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 22(1), 58–68. [Google Scholar]